Smith v GA Brief for the Respondent in Opposition

Public Court Documents

October 8, 1976

30 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v GA Brief for the Respondent in Opposition, 1976. b78833af-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9cdff2b3-f8cc-48b5-aed7-b9e245a0b54c/smith-v-ga-brief-for-the-respondent-in-opposition. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

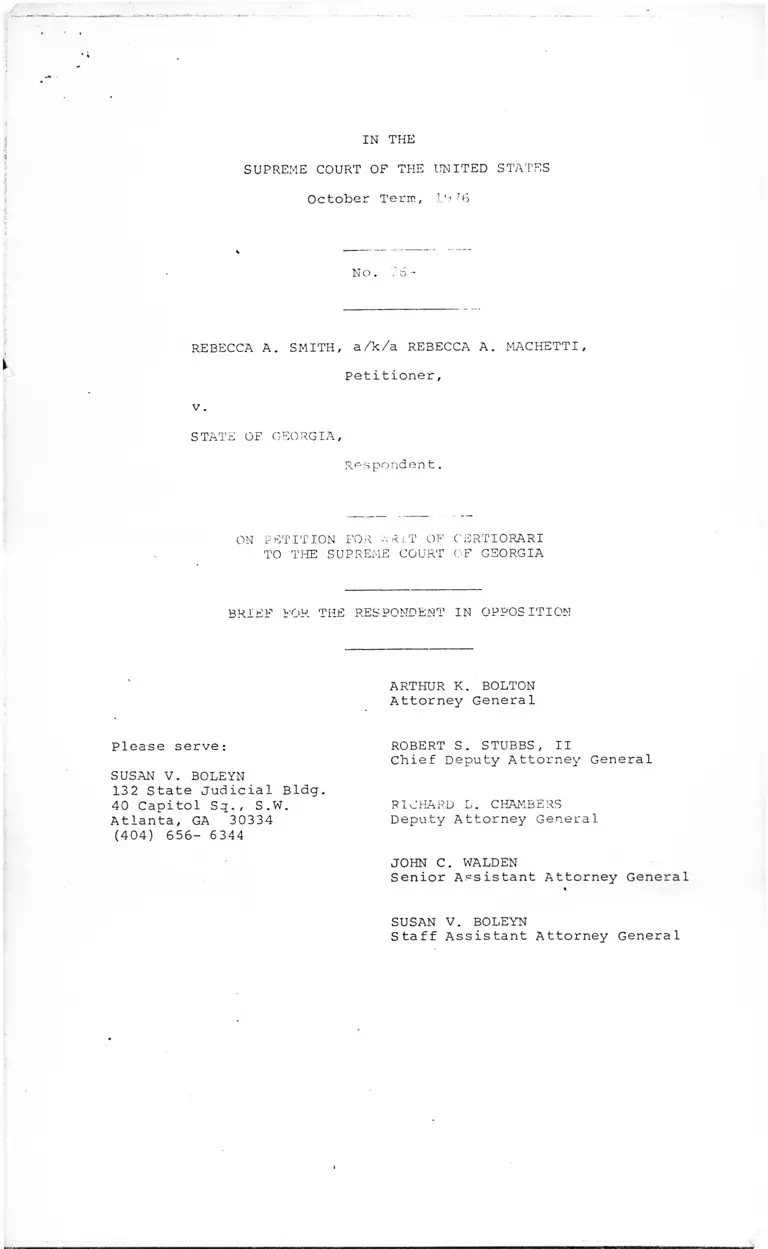

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, !.'.•> 76

No.

REBECCA A. SMITH, a/k/a REBECCA A. MACHETTI,

Petitioner,

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

ON PETITION FOR V.RiT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENT IN OPPOSITION

v.

ARTHUR K. BOLTON Attorney General

Please serve: ROBERT S. STUBBS, IIChief Deputy Attorney General

SUSAN V. BOLEYN 132 State Judicial Bldg.

40 Capitol Sq., S.W.

Atlanta, GA 30334

(404) 656- 6344

RICHARD L. CHAMBERS Deputy Attorney General

JOHN C. WALDENSenior Assistant Attorney General

SUSAN V. BOLEYNStaff Assistant Attorney General

INDEX

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ...................................... 3

REASONS FOR NOT GRANTING THE WRIT

%I.The exclusion for cause of two veniremen

who expressed their opinions that their

general conscientious objection to the im

position of the death penalty would prevent

them from making an impartial decision in the

case, and from considering the evidence produced

in this specific case, were properly excused for

cause, and their exclusion did not violate Peti

tioner's rights under the Sixth or Fourteenth

Amendments................................................. 5

A. The exclusion from the jury of two venire

men with conscientious scruples against the im

position of the death penalty was not violative-

V

of any of Petitioner's rights under either the

due process or equal protection clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment................................... 9

B. The test of exclusion utilized by the trial

court was in accordance with the constitutional

standards as enunciated in Witherspoon v. Illinois,

391 U.S. 510 (1968) .10

C. The exclusion of prospective jurors with

conscientious scruples against capital punish

ment did not deprive Petitioner of her right Io

*

a representative jury. ................................ i2

D. Questioning prospective jurors concerning

their attitudes towards the death penalty

did not violate Petitioner's rights under the

Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution. . .14

II. The imposition of the death penalty under the

Georgia capital punishment statute would not be

violative of Petitioner's rights under the Eight

or Fourteenth Amendments to the United States

Constitution........................................... 15

III. Consolidation of Petitioner's case with that of

v her husband on appeal to the Supreme Court of

Georgia did not violate Petitioner's rights under

the Fifth or Fourteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitution, as these cases were separately

docketed and all enumerations of errors considered.. . .16

IV. The trial court properly admitted the testimony of

police investigators, Wooters and Bieltz, concerning

their interviews with the Petitioner as this was not

violative of Petitioner's Fifth or Sixth Amendment

rights under the Constitution.......................... 18

ii

V. The State's elicitation at trial of the

fact that Petitioner had not disclosed

exculpatory evidence during police inter

views did not violate Petitioner's right %

•to due process, as Petitioner was not "in

custody" at the time of these interviews

and her "silence" was prior to being advised

of her Miranda rights.................................. 22

CONCLUSION ...................................................24

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE.........................................25

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases Cited:

Brov.:iy. Be to, 468 F. 2d 1284, 1286 (5th Ci.r. 1972)

Doyle v. Ohio, U.S. 49 L.Ed.2d 91 (1975)

Duncan v. Louisiana. 391 U.S. 145 (1968)

Gibson v. State. 236 Ga. 874 (1976)

Gregg v. Georgia

Miller v. State.

Miranda v. Ari.zo:

Smi th v. State,

United States v.

United States v.Hft.i ̂e(3—States—v. Mueller, 510 F. 2d 1116 (5th Cir. , April 7, 1975).

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968)

. 20,21

. 22,23

. 12

. 11

. 15,16

. 9

. 18,21,22

. 8,16,20

. 21

, 21

5,8, '0, l

12, 13

iv

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1976

NO. 76-

REBECCA A. SMITH, a/k/a

Rebecca Machetti,

Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENT IN OPPOSITION

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1.

\

Whether questioning prospective jurors on their

attitudes concerning the death penalty, and excluding two

prospective jurors for cause on the basis of an expression

of an "unconditional reservation" against the imposition of

the death penalty violate petitioner's rights under the Sixth

or Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution?

2 .

Whether the Georgia Capital Punishment statute recently

upheld in Gregg v. Georgia, ____ u.S. ____, No. 74-6257, decided

July 2, 1976, violated petitioner's rights under the Eighth or

Fourteenth Amendments?

3.

Whether the consolidation on nppeel to the Supreme Court

*

of Georgia of petitioner's case with that of her husband when

the cases were tried separately, docketed separately in the

Supreme Court, were based on the same underlying facts, and

raising almost identical enumerations of error, was prejudicial

to petitioner's constitutional rights?

4.

Whether the admission into evidence of testimony of law

enforcement officials concerning interviews held with the

petitioner while she was not "in custody" violated her rights

under the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the Constitution?

5.

Whether the State's elicitation at trial of the fact

that petitionee had not disclosed certain exculpatory evidence

during inteiviews with the police violated her Fourteenth

Amendment right to Due Process when this "silence" was not

"in the wake" of being given Miranda warnings as it did not

occur during custodial interrogation?

-2-

PART ONE

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioner, Rebecca Akins Smith, a/k/a Rebecca Akins

Machetti, was indicted by the Ribb County, Georgia grand jury

in its October'Term, 1974, with two counts of murder, and was

subsequently tried and convicted of both offenses on January 30,

1975. (R. 3-5; 30). The jury also found that both of the

murders were committed for the purpose of receiving money or

other things of monetary value, and a sentence of death was

I imposed on both counts. (R. 31-33).

|

|l In the late afternoon of August 31, 1974, Joseph Ronald

Akins and his wife of twenty days, Juanita Knight Akins, were

lured into a secluded area of Bibb County near Macon, and

brutally blasted by a shotgun at close range. (R. 443-50).

Mr. Akins was found in a pool of his own blood at the side of

his car, and Mrs. Akins was left stretched across the front

seat of the automobile, splattered with blood, and surrounded

by fragments of her teeth, hair and body tissue.}i

The conspiracy to kill the Akins was born in Miami,

Florida. Akins' former wife, Rebecca Akins Smith Machetti,

together with a friend, John Maree, plotted the August 31

tragedy with the intent of redeeming the proceeds of Akins'

\ ‘insurance policies, the beneficiaries of which were Mrs.

Machetti and her three daughters by Akins. Presumably, Maree

was to profit one thousand dollars for his participation, and

Machetti wished to enhance his reputation in the underworld

as a "hit man."

-3-

An investigation of the double murder was launched

irrunediately by the Bibb County Sheriff's Department. ■■v.

Akins' supervisor informed the authorities that his former

employee was recently divorced, and that the deceased had

previously been the targets of threats from his ex-wife.

Investigation of this information ultimately led to the

arrest of appellant and her husband, on October 16, 1974.

Additional facts will be developed as necessary for a

more thorough illumination of any issue raised in the petition.

PART TWO

FOR NOT GRAOTINGTHE_WRIT

T..s exclusion for cause of two veniremen

« iEXPRESSED THEIR OPINIONS THAT THEIR

GENERAL CONSCIENTIOUS TO THE IMPOSITION OF

THE DEATH PENALTY WOULD PREVENT THEM FROM

MAKING AN IMPARTIAL DECISION IN THE CASE,

AND FROM CONSIDERING THE EVIDENCE PRODUCED

IN THIS SPECIFIC CASE, WERE PROPERLY EXCUSED

FOR CAUSE, AND THEIR EXCLUSION DID NOT VIOLATE

PETITIONER'S RIGHTS UNDER THE SIXTH OR

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS.

Petitioner contends

from the jury for cause,

tion, was wrongful under

391 U.S. 510 (1968).

"District Attorney:

\

Juror:

District Attorney:

Juror:

District Attorney:

Juror:

District Attorney:

of two veniremen

the following examina-

Witherspoon v. Illinois,

Are you conscientiously

opposed to capital punish

ment?

Yes sir.

Beg your pardon?

Yes

You are opposed to capital

punishment?

Yes, sir.

Ms. Smith, would your

reservations about capital

punishment prevent you from

making an impartial decision

as to the guilt or innocence

of the Defendant?

that the exclusion

on the basis of

the standards of

-5-

i

Juror:Juror:

District Attorney:

Yes, sir.

Have you all ready decided

that if you are chosen as

a juror that you would, if

% you and your €~. 1 low jurors

found the Defendant guilty of

the.capital offense as charged

in this case, the offense of

murder, that you would vote

against a recommendation of

the death penalty, regardless

of the circumstances as they

develop from the witness stand?

Juror: Yes, sir.

District Attorney: You have all ready made that

dec is ion?

Juror: Yes, sir.

District Attorney: So then would it be fair to

say that you are not prepared

to consider fully and completely

the death penalty as one of

the penalties provided by law

in this case, in the event you

and your fellow jurors find

the Defendant guilty of murder?

Juror: Yes, sir.

District Attorney: You have all ready made the

decision that you would not

consider the death penalty?

Your honor I move to excuse

the jurors for cause.

The Court: The juror is disqualified.

Defense Counsel: I concur with the Court."

-6-

The following are the questions asked to the second

venireman' who was disqualified for cause:

"District Attorney: Are you conscientiously

opposed to capital punish

* ment?

Juror: Yes, sir.

District Attorney: You are, sir?

Juror: Yes, sir.

District Attorney: Would your reservation about

capital punishment prevent

you from making an impartial

decision in this case as to

the Defendant's guilt?

Juror: I believe it would.

District Attorney: Have you all ready decided

that if you and your fellow

jurors find the Defendant,

on either or both of the counts,

with which she is charged, that

you would vote against the

recommendation of the death

penalty without regard to the

facts and circumstances which

might emerge during the course

of this trial?

Juror: I would have to beagainst

execut ion.

District Attorney: So you are not then in position

to consider fairly and fully

the death penalty as one of

the penalties?

Juror: No, sir.

i -u i

District Attorney: I move we excuse this

juror for cause.

The Court: The juror is disqualified."

(T. 35-37)

The Georgia Supreme Court, however, determined that these

two jurors were properly excluded for cause and that there was

no violation of the standards set forth in Witherspoon v. Illinois,

supra.

"The standards of jury selections applicable

to death cases as set forth in Witherspoon as

amplified in Boulden v. Holman, 394 U.S. 478

(89SC 1138, 22 L.E.2d 433) and Maxwell v.

Bishop, 398 U.S. 262 (90 S.C. 1578, 26 L.E.2d

221), are that 'a sentence of death cannot be

carried out if the jury that imposed or

recommended it was chosen by excluding veniremen

for cause simply because they voiced general

' objections to the death penalty or expressed

conscientious or religious scruples against

its infliction.’ See also, Miller v. State, 224

Ga . 627(8) (163 S.E.2d 730) (1968); Simmons v.

State, 226 Ga. 110(12) (172 S. E. 2d 680) (1970);

Ross v. State, 233 Ga. 361(3) (211 S.E.2d 356)

(1974) . . . .

The voir dire transcript in the case of

Rebecca Machetti reveals that the jurors who

. indicated an unconditional reservation to the

imposition of the death penalty were excused

■ for cause by the trial court.

This enumeration is without merit. (Smith

v. State, 236 Ga. 12, 21-22, 222 S.E.2d 308,

316 (1976)."

-8-

This basis, on which the Georgia Supreme Court made their,

decision, being a valid one, based on the applicable legal

standards, offers no issue which needs to be decided by this

Court regarding the exclusion of these jurors.

A. THE EXCLUSION FROM THE JURY OF TWO VENIREMEN

WITH CONSCIENTIOUS SCRUPLES AGAINST THE IM

POSITION OF THE DEATH PENALTY WAS NOT

VIOLATIVE OF ANY OF PETITIONER'S RIGHTS

UNDER EITHER THE DUE PROCESS OR EQUAL PRO

TECTION CLAUSES OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT.

Petitioner asserts that Georgia's bifurcated trial statute

which covers capital sentencing does not contain a requirement

or preference that the sentencing jury be the same as the jury

which determines guilt or innocence. Petitioner argues as a

result of this assertion that equal protection and due process

have been violated. However, since the Georgia Supreme Court

in Miller v. State, ____ Ga. ____ (decided September 8, 1976),

held that the Georgia bifurcated trial statute requires the

jury which determines the guilt of a defendant to also determine

his sentence, there is no need for this Court to review

petitioner1s claim of the denial of due process and equal

protection in this regard.

-9-

B. THE TEST OF EXCLUSION UTILIZED BY THE TRIAL

COURT WAS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE CONSTI

TUTIONAL STANDARDS AS ENUNCIATED IN

WITHERSPOON V. ILLINOIS, 391 U.S. 510 (1968).

Petitioner argues that the trial court erred in excluding

two prospective jurors, having expressed conscientious opposition

to capital punishment, from the jury that convicted her and

imposed the death penalty. Two jurors were excused because

of their opposition the death penalty. In response to questions

by the district attorney, each of these prospective jurors

answered that they would vote against the recommendation of

the death penalty without regard to the facts and circumstances

being presented during the trial, in effect stating that uncer

no circumstances could they vote for the imposition of the

death penalty. Having expressed this "unconditional reserva

tion" to the imposition of the death penalty, these two

jurors were excused. (T. 35-37).

Although petitioner contends that the principles of

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968), were not

correctly applied during her trial, as previously stated,

the Georgia Supreme Court in its consideration of this

case on direct appeal, specifically found that the jurors

were properly excluded under the standards as set forth in

Witherspoon, supra. The Court stated that the jurors who

were excluded because of their conscientious scruples against

the death penalty, had not merely voiced "general objections"

to the death penalty, as were found to be insufficient for

the exclusion of a juror under Witherspoon, supra,

-10-

but instead that the voir dire revealed an expression by these

two prospective jurors of "an unconditional reservation to the

imposition of the death penalty." (Emphasis added). Code of

Georgia, § 59-806 (4) (1933) provides that inquiry as to opposi

tion to capital punishment should be propounded on the juror's

voir dire. Thus, jury panels are aware, before they hear any

evidence in any particular capital case, of the magnitude of

punishment that may be suffered by the defendant. "Each of

the prospective jurors excused makes it unmistakably clear

that he would vote against the death penalty regardless of what

transpires at trial." Gibson v. State, 236 Ga. 874, 877-878

(1976).

The trial judge was satisfied that under Witherspoon v.

11 linois, supra, the jury was properly excused for cause. The

Supreme Court of Georgia found that this expression of an

unconditional reservation to the imposition of the death penalty

meets the requirements of Witherspoon that the jurors' scruples

against the death penalty in all circumstances be "unmistakably

clear." Therefore, there is no further need for this Court

to review the questions presented by petitioner. The State

trial court and the State Supreme Court applying appropriate

principles have previously found petitoner's contentions to

be without merit. Under the facts of this case, there is no

basis upon which to question the conclusion reached by the

Supreme Court of Georgia. Thus, there is no need for further

review of a legally sound opinion.

-11-

c. THE EXCLUSION OF PROSPECTIVE JURORS WITH

CONSCIENTIOUS SCRUPLES AGAINST CAPITAL

PUNISHMENT DID NOT DEPRIVE PETITIONER

OF HER RIGHT TO A REPRESENTATIVE JURY.

Relying partially upon Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S.

145 (1968), petitioner argues that the exclusion of prospec

tive jurors expressing unalterable opposition to capital punish

ment deprived her of her Fifth Amendment right to a jury which

is representative of the community. Respondent asserts that

the Sixth Amendment does not mandate the inclusion of those

unalterably opposed to capital punishment on all juries that

may be asked to impose the supreme penalty on a defendant.

As to the issue of punishment, such juror's would necessarily

bring into question the impartiality of the jury panel.

Witherspoon v. Illinois, supra, 391 U.S. at 530 (separate opinion

of Douglas, J.).

Respondent addresses the question as to whether the exclusion

of those unalterably opposed to capital punishment from a jury that

is required to determine guilt, as well as to fix punishment, de

prives a defendant of a "representative11 Fifth Amendment jury.

The record presented by the petitioner reveals no factual information

that could assist the Court in determining whether or not petitioner's

jury was drawn from a "representative'cross-section of the community",

merely stating that "less than half of the people in the United

States believe in the death penalty", is not sufficient to demonstrate

that petitioner's jury was not drawn from a representative cross-

section of the community.

-12-

Even if a defendant was successful in demonstrating that

the jury, arguably neutral with respect to the penalty, was

biased in favor of the prosecution with respect to guilt,

" . . . The question would then arise %

whether the State interest in sub

mitting the penalty issue to a jury

capable of imposing capital punishment

may be vindicated at the expense of

the defendant's interest in a com

pletely fair determination of guilt

or innocence — given the possibility

of accomodating both interests by means

of a bifurcated trial, using one jury

to decide guilt and another to fix

punishment." Witherspoon v. Illinois,

supra, 391 U.S. at 520 (N. 18.).

Petitoner has made no effort to demonstrate that her

jury was guilt-biased. Her effort to set aside her conviction

on the basis of the death qualification of the jury must fail

for the same reason that the court rejected the petitoner's

contentions in Witherspoon. Id. at 516-518.

-13-

D. QUESTIONING PROSPECTIVE JURORS CONCERNING

THEIR ATTITUDES TOWARDS THE DEATH PENALTY

DID NOT VIOLATE PETITIONER'S RIGHTS UNDER

THE'SIXTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS TO

THE CONSTITUTION.

This assertion by the petitoner is an assertion discussed

in the previous section, attempting to show that the jury was

guilt-biased. However, petitioner has not been successful in

presenting to this court any supporting data for the allegation

that her jury was guilt-biased. As previously discussed,

separate juries do not, in fact, adjudicate guilt and fix

punishment. The jury which convicted Ms. Machetti also

recommended the death penalty. Therefore, a failure to question

prospective jurors as to their attitudes towards the death

penalty would violate traditional notions of a "fair trial" ,

which pre-supposes tha.t the jury determining both guilt or

innocence and setting the punishment, will be an impartial one.

Therefore, there is no need for review by this Court of this

question.

-14-

II. the imposition of the death penalty under

THE GEORGIA CAPITAL PUNISHMENT STATUTE

WOULD NOT BE VIOLATIVE OF PETITIONER'S

RIGHTS UNDER THE EIGHTH OR FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENTS TO THE UNITED STATES CONSTI

TUTION.

Petitioner has challenged the validity of her conviction

under the Georgia capital punishment statute and its application.

Although petitioner has made numerous assertions in support of

her contentions, the respondent submits that this Court's

decision in Gregg v. Georgia, No. 74-6257, decided July 2,

19 76 , in v/hich the Georgia capital punishment statute was

upheld by this Court, should be relied upon to prevent further

review of a question recently determined.

■̂n Gregg, supra, this Court received extensively the Georgia

statutory scheme for the imposition of the death penalty. This

Court concluded that, "In sum, we cannot say that the judgment of

the Georgia Legislature that capital punishment may be necessary

in some cases is clearly wrong. . . . We hold that the death

penalty is not a form of punishment that may never be imposed,

regardless of the circumstances of the offense, regardless of

the character of the offender, and regardless of the procedure

followed in reaching the decision to impose it." This Court

especially relied upon the Georgia statute's provisions that

the jury must find at least one statutory aggravating circumstance

before it may impose the death sentence and that such circum

stance must be specified. Further, this Court also emphasized

the expedited direct review by the Supreme Court of Georgia

of the appropriateness of imposing the sentence of death in

-15-

the particular case, and if the Court affirms a death sentence,

it is required to make reference in its decision to similar

cases which have been taken into consideration. The Georgia

Supreme Court affirmed the imposition of the death penalty in

petitioner's case, and specifically referred to similar cases

which had been considered by the Court. Therefore, the proper

statutory procedure was followed in petitoner's case.

As the statutory scheme which was upheld by this Court

in Gregg v. Georgia, supra, was followed in petitioner's case,

there is no necessity for a review of petitoner's case in order

to determine whether or not her constitutional rights have been

violated.

III. CONSOLIDATION OF PETITIONER'S CASE WITH THAT

OF HER HUSBAND ON APPEAL TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF GEORGIA DID NOT VIOLATE PETITIONER'S RIGHTS

UNDER THE FIFTH OR FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS TO

THE U. S. CONSTITUTION, AS THESE CASES WERE

\

SEPARATELY DOCKETED AND ALL ENUMERATIONS OF

ERROR CONSIDERED.

Petitoner, Rebecca Machetti, and her husband, Tony

Machetti, were indicted by the same grand jury, each on two

counts of murder. However, both petitioner and her husband

received individual trials on these charges. The Supreme

Court of Georgia, in its opinion deciding the individual

appeals of petitoner and her husband, merely wrote the opinion

deciding these appeals together. Smith v. State, 236 Ga. 12,

222 S.E.2d 308 (1976). Reference to the Georgia Supreme Court's

opinion shows immediately in the style of the case that the

appeals of petitoner and her husband were separately docketed

and there is even a notation that this is an opinion deciding

"two cases." This was obviously an exercise of judicial economy,

as the same underlying facts were present in both the case of

petitioner and her husband, and they were appealing from con

victions of the same offenses and also identical sentences.

It further appears from the opinion of the Georgia Supreme

Court that although the opinions were combined, the cases

were considered separately. For example, the Court noted

that Enumeration of Error No. 11 was made only by Tony

Machetti. In the portion of the opinion concerning sentence

review, the Court stated what each jury had decided in the

separate trials of petitioner and her husband.

Therefore, it appearing that the cases of petitoner and

her husband being identical as to the underlying facts, and

raising the same issues on appeal to the Georgia Supreme Court,

the rendering of an opinion concerning these two cases, which

were considered separately, was merely an exercise in judicial

efficiency. This claim is not the type which of necessity

should be reviewed by this Court.

-17-

TESTIMONY OF POLICE INVESTIGATORS, WOOTERS

AND •BIELTZ, CONCERNING THEIR INTERVIEWS

WITH THE PETITIONER AS THIS WAS NOT

VIOLATIVE OF PETITONER1S FIFTH OR

SIXTH AMENDMENT RIGHTS UNDER THE

CONSTITUTION.

Petitoner asserts that the trial court erred in admitting

the testimony of A. E. Woofers and Lawrence Bieltz, two

Florida law enforcement officers, concerning their inter

views with petitoner because their conversations with her

were not preceded by advising her of her constitutional

rights. Petitoner acknowledges that she was not "in custody"

of the authorities at the time of her interviews, but argues

that the Bibb County investigation had focused on her, and

thus, without the appropriate warning, her testimony should

have been excluded.

Petitoner raised this objection on direct appeal to the

Georgia Supreme Court. Testimony produced at petitoner's trial

revealed that appellant was interviewed on two occasions by

Florida authorities, and also spoke with Bibb County Deputy

Sheriff Wilkes. On neither occasion was she-advised of

her constitutional rights as described in the decision of Miranda

v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 486 (1966). However, petitioner made no

incriminating statements during these three interviews, merely

relating information to the officers to which she later testi

fied at trial. Initially petitioner telephoned Deputy Wilkes

IV. THE TRIAL COURT PROPERLY ADMITTED THE

-18-

at his reauest. During this conversation, petitioner detailed

her activities for the Labor Day weekend, and related that

Machetti had been on a fishing trip. Petitioner speculated

that her former husband's death was related either to his

traffic in drugs or his homosexual involvement. Appellant

made no mention of John Maree. (T. 600-608) .

Subsequently, Detective Wooters, with the North Miami

Police Department, spoke with petitioner at her home on

September 2, 1974, at the request of Bibb County authorities.

Detective hooters stated that petitioner was interviewed only

for purposes of establishing her address and the whereabouts

of herself and Machetti on the day of the murders. Petitioner

made no incriminating statements to Detective Wooters, she

merely related her activities during the Labor Day weekend,

and that Machetti had been on a fishing trip in Florida on

that weekend.

Petitioner was subsequently interviewed at her home on

September 30, 1974, by the Florida Department of Criminal

Law Enforcement. Officer Bieltz, who conducted this interview,

testified that petitioner was advised of the purpose of the

interview, voluntarily submitted to the questioning, and was

cooperative. Petitioner again gave no incriminating statements

to the authorities and repeated her earlier statements. (T. 394-95.

Arrest warrants were not obtained until October 15, 1974, two

weeks after petiti°ner interview with Bieltz.

-19-

Court found this contention to beThe Georgia Supreme

without merit. The Court found that petitioner "made no

incriminating statements during the three interviews, she

was not in custody, the investigation had not focused on her,

her statements consisted of possible reasons for her ex-husband s

death, and that her husband, appellant Tony Machetti, had been

on a fishing trip on the weekend of the crime." Smith v. State,

236 Ga. 12, 18 (1976). On the basis of this finding, the

Court stated that, "The evidence in connection with the inter

views in this case is outside the parameters of 'custodial

interrogation' delineated by the four criteria spelled out in

Brown v. 3eto, 46S F.2d 1284, 1236 (5th Cj.r. 19/2) , in that

at •* ’ i e time of the interviews: (1) the police.did not have

probable cause to arrest; (2) the subjective intent of police

was to locate possible persons involved; (3) the appellants

did not appear to believe themselves to be in custody and

subjected to interrogation; and (4) the investigation had not

at that time focused on the appellants as someone the State

planned to indict." Smith, supra, at 19.

The general rule in favor of a case-by-case analysis of

the precise contours of "custodial interrogation" is guided by

four criteria propounded by the Fifth Circuit in the case of

Brown v. Beto, 468 F.2d 1284, 1286 (5th Cir. 1972). This case

was the one on which the Georgia Supreme Court relied in its

opinion.

-20-

In Brown, the Court was careful to note that none of the

four factors were alone determinative of the issue of custody.

168 F.2d at 1286. That the focus factor alone is not determina

tive was recently emphasized by the Fifth Circuit. United

States v. Carrollo, 507 F.2d 50, 52 (5th Cir. 1975). When an

individual is at liberty to depart at any time, and to withhold

whatever information he wishes, the Miranda warnings are not

required. United States v. Mueller, 510 F.2d 1116, 1118 (5th

dir., April 7, 1975). Thus, since the time at which it becomes

necessary for the law enforcement officials to advise persons

of their constitutional rights is when they are placed "in

custody", and the petitoner in this case was not in custody

at the time she was interviewed by these law enforcement

officials, there was no need for her to be advised of her

constitutional rrgnts. Therefore, since the Georgia Supreme

Court correctly determined that the testimony by these law

enforcement officials was admissible since petitioner was not

in custody at the time she was interviewed, there is no need

\for further review of this issue by this Court.

✓

-21-

V. THE STATES ELICITATION AT TRIAL OF THE

FACT THAT PETITIONER HAD NOT DISCLOSED

EXCULPATORY EVIDENCE DURING POLICE

INTERVIEWS DID NOT VIOLATE PJ'.TITONER' S *

RIGHT TO DUE PROCESS, AS PETITONER WAS

NOT "IN CUSTODY" AT THE TIME OF THESE

INTERVIEWS AND HER "SILENCE" WAS PRIOR

TO BEING ADVISED OF HER MIRANDA RIGHTS.

Petitioner asserts that it was error for the State to

be allowed to elicit the fact that the petitioner had not

disclosed exculpatory evidence when she was first interrogated

by the police. Essentially, petitioner is contending that her

"silence" during an interview with police officers, was used

against her at trial. The main case which petitcner cites in

support of this contention is Doyle v. Ohio, U. S. ,

49 L.Ed.2d 31 (1976). Petitioner asserts that Doyle v. Ohio,

supzra, stands for the proposition that "Use of the defendant's

post-arrest silence in this manner violates due process",

because petidoner has a constitutional right to remain silent

in the face of police interrogation. However, as discussed con

cerning petitioner's previous contention concerning the ad

missibility of the law enforcement officers' testimony, it was

established that anything which petitioner stated or did not

state during the police interview, was not subject to the

requirement of Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966), or

other cases interpreting Miranda, when there is no "in-custody

interrogation". Again, petitioner was not "in custody" during

the time of the police interviews, and therefore could not

invoke a constitutional right to remain silent in the face

of police interrogation. The statements which petitioner made

on these occasions were made in a voluntary manner on her part.

-22-

Doyle v. Ohio, supra, also dealt with "silence in the

wake" of the Miranda warnings, which was interpreted as the

arrestee's exercise of these Miranda rights. However, the

"silence" of petitioner or her failure to disclose certain

exculpatory evidence during these police interviews, was

not "in the wake" of being advised of her Miranda warnings,

but instead was before these warnings were given. Therefore,

Doyle v. Ohio, supra, is inapplicable to the fact of petitioner's

case.

There being no "in custody" interrogation of petitioner,

and the failure of petitioner to disclose exculpatory evidence

during interviews with the police, being unable to be con

strued as silence in the wake of being advised of her Miranda

warnings, there is no issue presented for review by this Court.

-23-

CONCLUSION

Cased upon the i.oregoing, it is rcpectively submitted

that this petition for a writ of certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

ARTHUR K. BOLTON

Attorney General

ROBERT S. STUBBS, II

Chief Deputy Attorney General

RICHARD

Deputy Attorney General

JOH:S.C. WALDEN " ~

Senior Assistant Attorney General

SUSAN V. BOLEYN 7 /

Please Serve:

SUSAN V. BOLEYN

132 State Judicial Bldg.

40 Capitol Square, S. W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30334 (404) 656-6344

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, JOHN C. WALDEN, Attorney of Record for the Respondent,

and a member of the Bar of the Supreme Court of the United

States, hereby certify that in accordance with the rules of

the Supreme Court of the United States, I have this day served

a true and correct copy of this Brief for Respondent in

Opposition upon the Petitioner's attorney by depositing three

copies of same in the United States mail, with proper address

and adequate postage to:

MARY ANN B. OAKLEY

15 Peachtree Street, N.E. Suite 902

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Th i s of October, 19 7 6 .