White v. Florida Hearing Transcript II

Public Court Documents

September 22, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. White v. Florida Hearing Transcript II, 1969. 433be5fe-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9d0ce72f-9f58-430b-b40b-8f6f4850344a/white-v-florida-hearing-transcript-ii. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

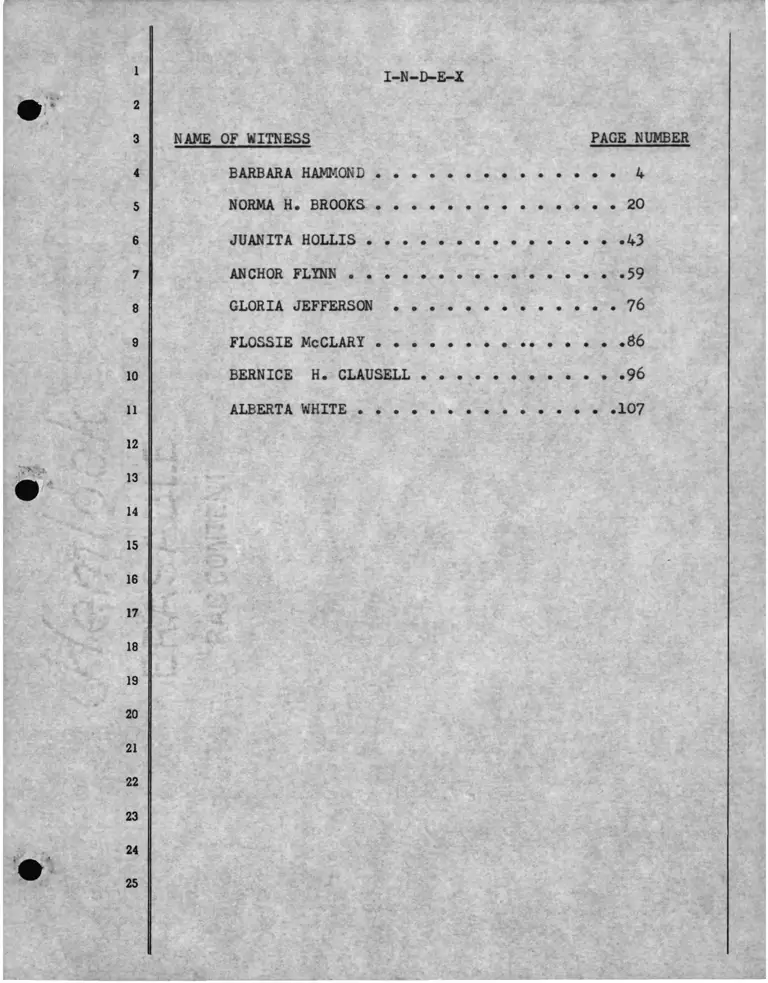

I-N—D-E—X

NAME OF WITNESS PAGE NUMBER

BARBARA HAMMOND .......................... 4

NORMA H. BROOKS........................... 20

JUANITA HOLLIS............................ 43

ANCHOR FLYNN.............................. 59

GLORIA JEFFERSON ........................ 76

FLOSSIE MeCLARY........................... 86

BERNICE H. CLAUSELL ...................... 96

ALBERTA WHITE ............................ 107

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

MR. GUAR I SCO: All right, let’s get the hearing unde::

way. Mr. Marshall, you have some witnesses you wanted to

use but did not have them here the last time. Are they

here today?

MR. MARSHALL: Yes, one is here and one is not. I

want to call Mrs. Flossie McClary.

MR. GUARISCO: All right, she needs to come up here

and be sworn. Mr. McClure, do you have some coming in?

MR. McCLURE: Yes, sir, but they have been sworn.

MR. GUARISCO: They’ve all been sworn, yours have?

MR. McCLURE: Yes, sir.

MR. GUARISCO: And do you have some coming who are

not here now?

MR. MARSHALL: Yes, I do.

MR. GUARISCO: Why don’t we swear in Mrs. White now

at the same time because she was not sworn in the last

time and then when the other witnesses come in we will

take care of them at that time.

MR. McCLURE: Mr. Chairman, I do have one who was

not sworn but she's not here yet but she will be here

shortly.

MR. GUARISCO: Well, when you see one coming in

through the door, let me know. We have the Rule invoked

here. If the Court Reporter will, then, we can swear

these two witnesses in.

(witnesses sworn a n d instructed on the rule by the

REPORTER.)

MR. GUARISCO: Gentlemen, we would like to, and I’m

sure that you do, too, have some decision this morning as

to the testimony being completed. It is my suggestion

that if we do that a waiver of any proposed order being

submitted to us be waived at this time, otherwise we will

have to prolong this thing for days. Are you in agreement

to do that, to waive any proposal that you might submit

for findings?

MR. McCLURE: We have discussed this earlier and

since we do have a Court Reporter I have no objection to

waiving that because we have all the findings here in the

transcript.

MR. GUARISCO; You understand, of course, that you

will be given an opportunity to file any exceptions to

the written findings at a later date, is that agreed?

MR. McCLURE: Yes, sir, fine.

MR. -MARSHALL: Yes.

MR. GUARISCO: Well, let the record show that both

counsel have waived the filing of a proposed finding and

save the right to file exceptions to any findings that

are filed at a later date by the School Board. This will

enable the School Board to render the decision today

after the testimony is taken. The other thing Iwould like

to call to your attention is that since you tried to use

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

your witnesses to the maximum without being repetitious

in order that we may proceed with this thing as rapidly

as possible today and conclude it. The last time we

worked our Court Reporter a little harder than we should

have but we were trying to get out of here, so about an

hour and fifteen minutes from now, we will stop and give

her a break because an arm gets numb after so much writin:

so fast, and so particularly. Is there anything else tha

anybody wants to bring up?

MR. McCLURE: Nothing here.

HR. GUARISCO: All right, Mr. McClure, you still hav

your case to present so you may begin with your witnesses

BARBARA HAMMOND

was called as a witness and having been previously sworn,

was examined and testified as follows:

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. McCLURE:

Q Miss Hammond, I believe that you have previously been swo:

is that correct?

A Yes, I have.

3 Would you state your name and address, please?

A Barbara Hammond, 3199 North Ridge Road.

3 And where do you work?

A. Pineview Elementary.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Pineview Elementary?

A Area.

Q How long have you worked there?

A One year.

Q One year, and what positions have you had or what jobs

have you had during the time you have been at Pineview?

A I started working as an aide, a teacher's aide.

Q Teacher's aide?

A Yes, and then I moved up to library aide.

Q What is your present position now?

A Now, I am working as a clerk-typist in the library in the

office.

Q You work in Mr. Tooks' office?

A Yes.

Q All right, in your job as secretary - - of course, let's

take your job as aide. What classrooms were you a teache

aide in?

A I was a teacher's aide in the classes of kindergarten,

first, second and third grades.

Q Have you ever been a teacher's aide in firs. White’s room?

A No.

Q What occasion, if any, have you ever had to be present in

Mrs. White's room?

A Well, there were occasions where I had to go in and I

would carry memorandums around. As an aide, in my job I

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

did different duties. If they were short and they needed

someone to carry a memorandum around, I would carry the

memorandum around and I had several occasions to go into

her classroom to take a memorandum.

Q Now, what occasion did you have to be in her room as a

teacher's aide.

A None, really.

Q None?

A No.

Q Now, when did you start as a secretary there in the schoo

A That was March.

Q March?

A In March.

Q And you stated that you had occasions to carry memorandum;

in that job as secretary?

A Yes.

Q Were you ever called on to deliver memorandums or message ;

to Mrs. White?

A I was called on to deliver them. I carried them to all

the teachers and Mrs. White was one of the teachers.

Q Do you recall when this was, during what time that you mav

have delivered any messages or memorandums to Mrs. White?

A It was several occasions.

Q Several occasions?

A Uh-huh.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q Would you explain to the Board exactly what your duties

were in delivering these messages or memoranda to Mrs. Whi

and what reaction she may have had to these memoranda?

A Well, there was several occasions that I remember that I

carried in memorandums and I would give them to her and

she would read them and she would just mumble something.

There was one occasion on one morning when there was a

meeting being held and I was told to tell the teachers

when they came in that the meeting was in the library

and I specifically told Mrs. White that they were having

a meeting in the library and she said to me, "Well, I'm

not a teacher, anyhow," and kept, you know - - usually,

when I would carry memorandums she would read them and

mumble something, you know, and I would just keep on goinc

Q All right, what were your instructions and who were the

memorandums from?

A The memorandums were from the office, to take them to

each teacher and have them sign it.

Q You say they were from the office, who in the office?

A Mr. Tooks.

Q Were there ever occasions where Mrs. White did not read

the memorandums?

A There were several occasions that I remember that I carric

them in and she just signed her name.

Q All right, would you explain approximately when this may

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

have happened and how many times it happened?

A Well, it would be sort of hard to say but this I remember

was specifically in April that I was taking it around

but I can’t remember just what it was about.

Q April of what year?

A This past year.

Q 1969?

A Yes, 1969, and I carried it in and she just mumbled some

thing and signed her name.

Q Did she read the message?

A I don't know, I couldn't say that she read it.

Q All right, would you describe to the Board how you de

livered the memorandum and what Mrs. White's reaction was

of what she did when she signed it?

A Well, on one of the occasions when I went in she was

nodding and I just said, "Mrs. White," and she woke up

and, you know, I put it in front of her on her desk.

Q She was nodding?

A Yes.

Q Was this during any lunch break or was it during the class

A Well, the children were all in the classroom and I'm

quite sure the children had already had their lunch.

Q All right, how cculd you tell that Mrs. White was nodding|?

A Well, she had her head down and her eyes were closed.

Q Did she bring her head up when you came into the room?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

No, it was after I had gotten over to her desk and spoken

to her.

} Would you tell in your own words from the time you enterec

the room until the time you get to Mrs. White’s desk and

she lifted her head?

\ Well, her room - - in her room her desk is in a corner

kinda like this by a window so you have to walk a distance

before you get to her desk. When I walked in the children

were in there and they were talking and running around

the room and I walked over to the desk and her head was

down on the desk like that. If someone walked in a class

room, to me you should be able to see them, you know,if

your eyes are open.

Q All right, we have a diagram of the classroom over here

on the board and I would like for you to point out to the

Board where the door to Mrs. White's classroom was and the

position of her desk and the route that you took to get

to her desk. Would you come over here, please?

A (Witness went to blackboard.)

Q All right, would you tell where the office was and where

you came from when you went to her desk?

A Yes, this is the office right here. I came from here anc

I went up the hallway and into Mrs. Hollis' room and

across to Mrs. White's room. Her desk is here and I

walked straight across the room and over to her desk.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Now, which way were the students faced at this time? Wou

you mark where Mrs. White’s desk was in her room, just a

little black box or something there?

The children were facing toward the blackboard here. Thi

is the blackboard and the children were facing toward the

blackboard and also their desks were.

Q You walked all the way across the room?

A Yes, sir.

Q When did you first notice that Mrs. White was nodding?

A When I first entered the room.

Q All right, and her desk was where?

A Here, (indicating.)

Q Did you call to her at any time?

A I didn't call to her but I just walked over to her and

called, "Mrs. White".

Q All right, you may have a seat. (Witness seated.) During

these trips into the classroom did you observe the conducfl

of the children in the classroom?

A Yes.

Q Would you explain in detail exactly what you saw the

children were doing?

A There were occasions when I would enter the room that thek

would be running all over the room and throwing paper and

just, you know, unruly in general.

Q Was Mrs. White present during this time?

11

1 A

Q

A

Q

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14 A

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Yes.

On how many occasions did you see this happening?

Oh, boy, I can’t nention how many times I actually saw this

Well, could you give us an average? Would this be the

beginning of the ’68-'69 school term or when you were

there as an aide?

There were several occasions when I would go in to the

hallway there, because I had to go to Mrs. Williams’ room

and her classroom is on that hallway, and I would go by

there and I would see the children being unruly on number

of occasions.

On how many occasions did you deliver messages to Airs.

White, say on a weekly basis, how many times a week?

Well, this varied and I couldn't actually say how many

times in one week because some weeks I wouldn't have to

take any around and then at least two or three times a

month, I could say that I did that, I believe.

Okay, can you tell the Board if you observed any work of

the children on the blackboards in Mrs. White’s room?

ArtR. MARSHALL: Air. Chairman, I would like to object

to any leading questions. "Did you observe any children*

work", and all the witness has to do is answer yes or no

and certainly this is a leading question on the part of

Air. McClure.

AdR. GUARISCO: I will sustain that. Air. McClure,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

please phrase your questions so that you can avoid suggest

ing answers and leading the witness.

MR. McCLURE: I sure will.

Q What, if anything did you observe on the blackboard in

Mrs. White’s room?

A Well, there were the alphabets.

Q And what else?

A That's about all and during Christmas she had some

Christmas decorations that had been, you know, purchased,

the cardboard type decorations and such.

Q Any other decorations up there during the Christmas seasor

other than the ones she purchased?

A I didn't see any.

Q At your other visits to the classroom, did you visit there

on other occasions during a holiday season?

A No.

Q When you delivered messages in there, what did you observe

up on the blackboards?

A Nothing, really.

MR. McCLURE: I have no further questions.

CROSS EXAMINATION

BY MR. MARSHALL:

Q Mrs. Hammond, what areas are you certified to teach in,

please?

A None.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A I went to elementary and high school in St. Augustine and

I attended Florida A&M a year.

Q When were you hired as a teachei's aide at Pineview?

A August of 1968, the school term ,68-,69.

Q What year did you attend Florida A&M?

A 1950.

Q 1950?

Yes.

Q What positions have you held since 1950?

A I have none. My husband has been in the service and I

have been travelling with him.

Q Have you held any other teaching positions?

A No, I have worked in the Red Cross and I have worked in

the schools as a Red Cross volunteer nurse’s aide.

Q Are you from Tallahassee, were you born in Tallahassee?

A No, I'm not.

Q When did you get to Tallahassee, 1950?

A I came in September of 1950 and I stayed on until June of

1951.

Q And when did you return?^-

A I have been back several times, but to live - -

MR. McCLURE: I would like to object because I think

it is immaterial when she first came to Tallahassee.

q Where did you go to school?

MR. GUARISCO: I will sustain the objection because

we are going far afield. There was nothing in direct

brought out in these matters and the individual’s person4l

background has no bearing on this.

Mrs. Hammond, have you had any special training in Library

Science or any special training at all in Library Science ?

No.

I believe you testified that you became secretary to/ *

Mr. Tooks in March of 1969, is that correct?

Yes.

And I believe you also testified that you had no occasior

to visit the room of Mrs. White prior to that time, is

that right?

No, I didn't say that.

But you never visited her class as a teacher’s aide, is

that right?

When I carried memorandums I was a teacher's aide.

You mean in March of '69?

Yes, the first part of March.

Now, when did you begin to deliver these memorandums, in

March of '69?

I delivered memorandums from the very beginning of the

school term.

August of *68?

No, not August but in September when the teachers came

back and I was called on to deliver them at certain times.

Do you know the schedule of the students who were in

Mrs. White's classroom, did you know their schedule?

No, not the entire schedule. I knew what time they were

supposed to have lunch.

How did you know that?

Because my lunch hour was during that time and sometime I

would assist with the counting of the lunches out. You

know, we have a list and we check the list off as the

children would deliver the lunches.

What would you do when you delivered these messages, what

would you do after you handed the message to Mrs. White,

the memorandum?

After I gave it to her and she signed it then I would

leave the classroom and go on and deliver it to the other

teachers.

Did you have more than one, did each teacher have a memo-

dum?

No, there was one memorandum for all the teachers and

they had to initial it.

Did you stand there while the memorandum was being read,

is that right?

Yes.

And you say on each occasion Mrs. White would read the

message, however, the memorandum that you delivered?

No, I didn't say that.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A I said she did not read them.

Q I’m sorry?

A I said she did not.

Q She did not?

A That’s right.

Q Didn't you say that she would read the memorandum and

then she would mumble something?

A I said that she would glance at them and mumble something.

Q She would glance at them?

A That's right.

Q You mean she never read a memorandum?

A I can’t say that she never read a memorandum.

Q How many times would you say that she did not read the

memorandum?

A I said that in April I remembered specifically the inci

dent that when I carried the memorandum in and she

mumbled that she wasn't a teacher.

Q And that's only one occasion, is that right?

A That's the only occasion that I can remember specifically

where she really did not read it and I can say that she

did not read it.

Q And you are currently at Pineview, are you not?

A Yes.

Q How well do you know Mr. Tooks, are you related to him?

Q Well, what did you say?

17

1 1A No, I'm not.

Q Are you related by marriage?

A By marriage.

Q Are you Mr. looks' sister-in-law?

A Yes.

MR. MARSHALL: I have no further questions.

REDIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. McCLURE:

Q Mrs. Hammond, the fact that you might be Mr. Tooks' sister-

in-law by marriage, do you feel that you can still tell

what you saw and tell it like it was?

A Yes, sure.

Q Would this relationship make you say that you saw Mrs.

White sleeping when she wasn't sleeping?

A No, it would not.

Q Would it in any way affect the testimony that you have

given here today?

A No, it would not. May I say something?

Q I think probably not.

MR. GUARISCO: If counsel will ask you a question

you can respond; otherwise, we will wait until one of the

asks you a question.

MR. McCLURE: I have no further questions.

MR. MARSHALL: I have just one question or so.

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

m

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

BY MR. MARSHALL:

Q Isn't it true, Mrs. Hammond, that you told Mrs. White

later that you never saw her sleeping or nodding in class

A No, I never said that to Mrs. White.

Q You never said that to her?

A No, I did not.

Q Was this only on one occasion that you - -

MR. GUARISCO: Mr. Marshall, I believe one of your

witnesses just came in, so let's get them sworn in and

put under the Rule.

(WITNESSES CAME FORWARD, WERE SWORN AMD PLACED UNDER

THE RULE BY REPORTER.)

BY MR. MARSHALL:

Q Mrs. Hammond, was this just one occasion that you enterec

Mrs. White's room and you saw her nodding?

A I entered Mrs. White's room so many times during the yeai

carrying memorandums and several times, more than once,

did I see her nodding. As a matter of fact, I have

passed her classroom and seen her nodding while I was go

ing down the hall.

Q You have?

A Yes, you know, when your head bobs, you are asleep, usual,

Q You could not tell, though, could you? You say you think

A Well, when you walk in a classroom and you cross the room

to me, in all the other classrooms that I went in, the

RECROSS EXAMINATION

I

teacher immediately noticed me and spoke to me when I

walked in. Her eyes would be closed and I would walk right

up to her desk before she would say anything.

But the occasions when you passed the hall, you could see

her clearly?

No, I could not say absolutely about that.

Now, you say that the children were unruly. Were they

really any more unruly than any normal elementary class?

For a teacher to be in the classroom, I would say so.

But these are elementary children and they are very young.

Weren*t the other classrooms in about the same - -

No, I can't say that.

This was only in Mrs. White's class?

No, there were different classes but not all at the same

time.

So this was not confined, then, to Mrs. White, is that

right?

That's right but the majority of it was in that hallway

over there. There's two, four, six, twelve classrooms in

that hall and when I would go down there - - I can't say

just exactly what time, but there were several times when

I did go by and I felt that the children were quite unrul'r

and they were very loud and they were throwing paper and

she was sitting there in the room.

MR. MARSHALL: No further questions.

19

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

MR. McCLURE: No further questions.

MR. GUARISCO: Do you need the witness or can we

dismiss her?

MR. MARSHALL: We can dismiss her as far as I'm

concerned.

MR. McCLURE: She can be dismissed.

MR. GUARISCO: All right, you may be excused.

(WITNESS EXCUSED.)

NORMA H. BROOKS

was called as a witness and having been previously sworn,

was examined and testified as follows:

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY .MR. McCLURE:

Q Would you state your name and address, please?

A Norma H. Brooks, 1621 Hernando Drive, Tallahassee.

Q And where are you employed?

A Pineview Elementary School.

Q How long have you been there?

A Two years.

Q What type work do you do at Pineview?

A Fifth grade teacher.

Q Fifth grade teacher, and you have been teaching there foi

two years, is that right?

A Yes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q How long have you been in the teaching profession?

A Fifteen years.

Q And where have you taught before you came to Pineview?

A At Barrow Hill Elementary School.

Q You will have to speak up, now, so everyone can hear you.

A All right, that was Barrow Hill Elementary School.

Q Do you know Mrs. Alberta White?

A Yes, sir, I do.

Q How long have you known her?

A Well, I really don’t know how long I have known her but

I worked with her for two years.

Q You have worked with her for two years at Pineview?

A Yes, this was at Pineview.

Q All right, I would like to direct your attention to the

beginning of the *67-'68 school term, not this past one

but the term before. On what occasion, if any, have you

had to work with Mrs. White?

A I was grade level chairman of the fifth grade in *67-'68

and she was working on the fifth grade level.

Q Could you tell the Board about what relationship you had

with Mrs. White in this type work?

A Well, in the beginning of the school year I think we had

one misunderstanding at the very beginning of the school

year when it was time to give the reading inventory test

and she wasn’t agreeable and didn’t think that it was

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

necessary to give it because she thought that it was a

waste of time.

Q Was this a standard thing required of all teachers to do?

A Yes, we were giving the inventory tests to find out the

reading levels of the children.

Q All right, and where did those instructions come from to

find out the reading levels?

A I think from the curriculum coordinator.

Q Did Mr. Tooks confirm that particular idea?

A Well, I'm sure he did.

Q And what did Mrs. White say about it?

A Well, she said she thought that it was waste of time to

give them.

MR. MARSHALL: Mr. Chairman, I don't believe the

witness is being responsive. The question was asked what

did she say and the witness answered as to what Mrs. Whit|e

thought.

MR. GUARISCO: All right, and I will ask you to talk

a little louder, too, so that we can hear. Some of these

answers we are barely able to hear. Ask the question aga

Mr. McClure, if you will, and we will pick it up from ther

MR. McCLURE: I would like to have the Court Reporter

read it back, if she would.

(LAST QUESTION AND ANSWER READ BY THE REPORTER.)

Q She said what, then?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

it because it wouldn’t help the children.

Q On what occasions have you had to go into Mrs. White'3

room?

a Well, I have been in Mrs. White’s room several times. I

do remember one time in particular when I went in there

and she was sitting to the desk with her had down and - -

Q Would you describe to the Board what you mean by having

her head down?

A Well, down in this manner (demonstrating) and I walked up

to her desk and she didn’t move and I called her and she,

you know, responded but at first her head was down like

this and I walked all the way over to her and I touched

her and called to her.

Q How many times did you call to her?

A Possibly twice.

Q Would you come over here and demonstrate where Mrs. White

room was? This is a diagram of the school and this is

the diagram of the classroom assignment in the '68-'69

year so she might have been in a different room then.

A It’s right here, I believe.

Q All right, would you tell the Board which direction you

came from?

A This is my room over here and I came across the hall.

Q All right, and would you mark an "X" where Mrs. White's

A She said that she thought it was a waste of time to give

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

desk was at that time?

A It was sitting about here (indicating.)*

Q And you proceeded from the door and would you again tell

how you approached Mrs. White?

A I came in the door here and walked across to Mrs. White

and, of course, she did not move at the time that I came

in and then I called her name and then I touched her and

after I had touched her she responded.

Q Did she respond when you touched her?

A Yes.

Q All right, you may be seated, (witness seated.) Can you

recall any other instances where you observed her with he

head down?

A Those are the only two times that I remember in ’67-*68.

Q Were the children in the room during this time, in the

classroom?

A Yes, they were.

Q Could you tell the Board what the children were doing

during this time when you walked into the classroom?

A Well, there were a few that seemed to be getting some

lessons and over half of them were just talking.

Q Then over half of them weren't getting their lessons?

A Weren’t getting their lessons, that’s right.

Q What instructions did the faculty have, if any, in the

’67-'68 school term about displaying children’s work?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

IS

20

21

22

23

24

25

\

A Well, we were supposed to display as much of the children

work as possible.

Q And where did those instructions come from?

A They came from the curriculum coordinator and also the

principal, too.

Q Why is it important to display children’s work?

A Well, I feel it's important because it makes the child -

to a certain degree he might feel that he was having a

little competition when he sees the work up and sees how

others do it and there is an incentive there to him to

see his work up.

Q When is this work particularly stressed?

A When - - well, during the whole school year, really.

Q Are there specific occasions around holiday seasons that

teachers normally put children's work up?

A Well, maybe during holidays but usually the whole year

around, really.

Q Did you observe or have occasion to go into i'Ars. White's

room during any of the holiday seasons?

A Well, I imagine I have been in there during the holiday

seasons. I did observe that she had a lot of commercial

type materials up.

Q When was this?

A Almost during any holiday.

Q What do you mean when you say she had a lot of commercial

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

stuff up there?

A Well, the type material that you buy in the store and not

the type that children would make.

Q On how many holidays did you go into her room?

A Oh, I imagine whenever there was an occasion. I just

wouldn't go in there.

Q What school term was this during?

A The 1967-'68.

Q Did you have any occasion to go and observe this past

school term?

A I probably didn't pay any attention this past school year

Q What is your professional opinion of the effect of using

commercial decorations rather than the children's works;

what effect, in your professional opinion as a teacher,

would this have on the children?

MR. MARSHALL: Mr. Chairman, I object to that becaus

there has been no proper foundation. We are going into a

psychological area and I don't know whether the witness

is qualified.

MR. McCLURE: Mr. Chairman, I think she testified

that she has been in the teaching profession for fifteen

years and I believe that would qualify her as an expert

witness.

MR. GUARISCO: I'll overrule the objection, go aheac

MR. McCLURE: Would you read the question, please?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

(QUESTION READ BY REPORTER.)

A Well, personally I don't know if it would have ary effect

on the child other than children just like to do art work

and this type of thing and they like to sse their work up.

Q But you also testified that it puts competition in the

children's attitude?

A Yes, to a certain degree.

Q Is this a healthy attitude?

A Well, as far as art and if the person can draw, I see

nothing wrong with it.

Q Now, did your room move during the '68-’69 school year?

A It was in the same place.

Q It was in the same place, and Mrs. White's room was then

moved before this past year? This is a diagram of the

school here.

A That's right.

Q Now, did you go by her room to and from your room?

A Whenever I would go to the lounge or the principal's

office I would have to pass in that direction,

Q All right, and would this be on a daily basis?

A Constantly, because the restrooms and the library and

the principal's office and everything is on that other

end.

Q And how often would you see Mrs. White during a school

day?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A Well, quite often. I really wouldn't know just how often

Q But you did see her on a daily basis?

A Surely.

Q Did you have occasion to observe Mrs. White's personal

clothes at the school?

A Yes, sir, I did.

Q Would you describe in detail the type of clothing that

she wore and her appearance in general?

A Well, some days she wasn't as tidy as others and some

days her clothes seemed to be a little soiled.

Q All right, and which would you say would be the most

frequent?

A Well, untidy, I guess, more so than soiled.

Q Untidy?

A Yes, more so than soiled.

Q In your professional opinion as a teacher, what effect

does an untidy appearance have on the children?

A I think children like to see teachers tidy and clean.

Q In your professional opinion as a teacher, why should a

teacher appear tidy and clean?

A Well, you are trying to stimulate and teach the child to

be tidy and clean so I feel that you need to exemplify

those qualities yourself.

Q And what effect does a personal appearance have on the

teacher% effectiveness to teach and to command respect

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

and discipline?

MR. MARSHALL: Mr. Chairman, I will again object to

that because this seems to be going beyond the profession

qualifications of this witness.

MR. McCLURE: Again, Mr. Chairman, I think that as a

teacher of fifteen years she can^form a professional opin

as to what effect the appearance of the teacher has on

her ability to convey the education she is supposed to

give the students.

MR. GUARISCO: I am going to overrule this on the

basis, Mr. Marshall, that we really don't have a jury

here and we just have a panel of officials who are trying

to evaluate and be fair on both sides. I think that the

question was all right to bring this out but, at the

same time, let's stay with materiality and hold the

questions down to where you can make a point in the

material that you are trying to prove.

MR. McCLURE: All right, sir, I sincerely believe

that the appearance and the effectiveness of a teacher

would be material.

MR. GUARISCO: I think you've got a point there that

needs to be brought out and the panel can evaluate it.

MR. McCLURE: All right, would you repeat the questi<

please?

(QUESTION READ BY REPORTER.)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A I think that if the teacher is tidy and clean, then the

children will more or less emulate and, of course, they

will follow some of the same things that they see their

teacher is doing.

q What is your professional opinion on a teacher maintaining

a clean classroom? What effect does this have on the

children?

A Well, I think when the children have been motivated and

interested in the classroom that they will try to keep th<

classroom as clean as possible, but I think the teacher

needs to stress this point.

Q What effect would a dirty or a littered classroom have,

in your professional opinion, on the students themselves?

A Well, it might take away some of the learning habits of

the children.

Q Then, it would be a distraction, is that what you’re sayi:

A Yes.

MR. McCLURE: No further questions.

CROSS EXAMINATION

BY MR. MARSHALL:

Q Mrs. Brooks, were you at Barrow Hill at the same time

Mr. Tooks was there?

A Yes, sir, I was.

MR. GUARISCO: Would you speak up a little, please?

Q And then how long were you there with Mr. Tooks?

A

Q

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11 «Q

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

A

Q

A

Q

A

About six years.

And you transferred to Pineview at the same time, or

about the same time that .Mr. Tooks transferred, is that

right?

I did.":. ...

Let me clarify once again about the inventory test. You

testified that was to test the reading capacity of the

children, is that right?

Yes, trying to place the children together according to

their needs and skills that they needed in reading.

Does that test, then, determine the interest level of the

student or the reading level of the student?

Well, it tests the reading level and, of course, this is

where we will place them according to the skills that they

need.

Now, was that test administered, this test that you're

talking about?

Yes, it was administered.

So what you were saying was just an opinion given by

Mrs. White, you didn't mean to say that she refused to

give the test, did she?

At first, she was reluctant but if I recall correctly

I think she did administer it.

She did, because the children were placed, so she did

25 give the test?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A That's right.

Q And I suppose you have many opinions, just like the ones

you expressed today?

so

A Well, I had the right to do/on that one because of what

she said.

Q I mean, but you have your own personal opinions about

things?

A You mean about anything?

Q That's right.

A Surely.

Q Just like Mrs. White had a personal opinion then, that

had nothing to do with running the school or giving of

the tests because one was given?

A Well, it had something to do with the test because she

made the statement.

Q But on the administrative level this had nothing to do

with it because the test was given?

A Well, the possibility that it was delayed and was not

given at the time designated.

Q Was it delayed?

A Offhand, I really can't remember.

Q Tell me what time are teachers normally - - what time do

teachers arrive at Pineview Elementary School in the

mornings, can you tell us that?

A Eight o'clock.

Is that the time you arrive?

Eight or a little before.

Is there any requirement that you be there before eight

o'clock?

MR. McCLURE: Your Honor, Mr. Chairman, I would like

to object to that line of questioning. I don't believe

I brought anything out in direct about the time.

MR. GUARISCO: No, there was not. I don't recall

anything being brought out about the time of arrival. I

think this was Mr. Tooks a couple of days ago that testi

fied on this.

MR. MARSHALL: Respectfully, Mr. Chairman, nothing

was brought out about the condition of Mrs. White's room

but the question was asked, what, in your opinion,would

the appearance of the room have on children and I think

that I can relate it to other testimony.

MR. GUARISCO: All right, I will allow you to ask

the question but hold the questions to what is really

pertinent to direct examination.

/ MR. MARSHALL: Well, I withdraw the question.

Mrs. Brooks, the commercial arts that's on the bulletin

board during the school year, where does that come from?

You purchase It.

Does the school purchase that?

No, individuals purchase that type material.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

8

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q And do you also purchase that type of material?

A No.

Q You do not?

A No.

Q How about other teachers, have you observed any other

commercial material by other teachers?

A I imagine some of the other teachers do purchase it.

Q You have seen it in the school, is that right?

A I don't remember seeing it.

Q You don't remember seeing it?

A Offhand, I don't remember seeing it.

Q But you do remember seeing it in Mrs. White's room?

A Yes. Now, when I say I don't remember seeing it, I don'1

remember seeing it there at Pineview but I do remember

some years ago we used to purchase it but I do not re

member seeing any there. I don’t remember offhand seeinc

any.

Q So you didn't see any in Mrs. White's room?

A Well, I said that I saw some in hers, because I had a

reason to go in there.

Q Did you also go in all the other rooms, other than

Mrs. White's and your own?

A Yes, occasionally.

Q Do you observe these other rooms when you go in them?

A Naturally, when you go in a room you observe them.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q And you can’t recall seeing any of that commercial art ir

other rooms other than Mrs. White’s?

A Offhand, right now, I can’t.

Q Is there any particular reason why you remember Mrs. Whi1

room?

A Well, as being grade level chairman, you are naturally

going into the room constantly and when you go into a

room you certainly would observe it, yes.

Q Did you go into other rooms constantly?

A No, I would have no reason to.

Q Now, would there be any work at all by the students on

the bulletin board?

A I remember on one or two occasions I did see a few pieces

of art work demonstrated.

Q Now, tell us what you mean. You say that you had occasior

to place on the bulletin board - - you said you had in

structions to place on the board as much work of the

students as possible, is that what you said?

A That’s right.

Q And in certain instances it was varied, I suppose, as to

the amount of work that could be placed on the bulletin

board, is that right?

A That’s right.

Q Now, you talked about the dress of Mrs. White and said

that it was untidy on occasions. Was the occasions more

untidy rather than tidy?

Well, I mean to me.

To you?

Yes. S ;

So that that's just your personal opinion, is that it?

Yes.

Would you say that she is untidy today?

No, she doesn’t seem to be untidy today.

Did you report these occasions when you would notice the

dress of Mrs. White, as well as her conduct in the class

room, would you report this to the principal, Mr. Tooks?

Definitely no.

You would not?

I would not.

Why wouldn’t you?

I wouldn't have any reason to.

Certainly other teachers also on some days would be a bit

untidy at Pineview, would they not?

I imagine there are occasions when all of us might be.

That's right, so how about the time you testified you

noticed Mrs. White? Did you say that she was asleep

when you came into the room?

She seemed to be asleep to me because anytime you walk

into a room and walk all the way across the room to a

person and call to them, call their name, and they don't

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

- - answer, to me they would be asleep.

Q When was this, if you can recall?

A This was in the year '67-’68.

Q Did you report that?

A I would not have any reason to report anything like that.

Q Did you on any other occasions see this except this once?

A I saw it twice.

Q Twice?

A That's right.

Q And when was the next time?

A This was during '67-*68.

Q Both was during the '67-'68 year?

A Yes.

Q Did you report either of these two instances to - -

A I had no reason to report this.

Q And you know that she did teach there last year, is that

right?

A That's right.

MR. MARSHALL: I have no further questions.

REDIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. McCLURE:

Q Mrs. Brooks, on Mrs. White's untidiness, did you observe

or would you say that you observed her untidiness on

isolated instances or was it a common occurrence?

A To me it was a common occurrence, not just certain instar

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

IS

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q Would this be a common occurrence in the '67-'68 school

term?

A That's right.

Q And did this practice continue in the '68-'69 term?

A Well, several of the times that X saw her.

Q Which term was this in?

A '68-'69.

Q So then you observed her untidy appearance over a two-yea

period?

A That's right.

MR. McCLURE: Mr. Chairman, Mr. Marshall has stated

that we did not bring out any testimony as to the appear

ance of Mrs. White's classroom through the testimony of

Mrs. Brooks here but, if I recall correctly, I think we

did ask her that.

MR. GUARISCO: I think you did too, but that, of

course, will be evidenced in the record to be reviewed

later.

MR. McCLURE: Well, I wanted to ask her several

questions on redirect and I would like a ruling from the

Chair.

MR. GUARISCO: No, I didn't say you hadn't done it.

I distinctly remember you asking about the tidiness of

the room and so forth. If you have some questions you

want to ask in that direction, you may proceed.

39

MR. McCLURE: All right, thank you.

MR. MARSHALL: Mr. Chairman, may I just have a con

tinuing objection to any quetioning now about the appearahce

or the cleanliness or tidiness of the room. This certain|L

has not been gone into on cross.

MR. McCLURE: I think on redirect that I’m allowed

to ask some more questions on this.

MR. GUARISCO: I am going to allow you to ask the

questions. If it only goes to exploring both sides of

this and allowing all the record to be complete for us to

really arrive at a conclusion.

BY MR. McCLURE:

Q Could you tell the Board what you observed and the appear

ance of Mrs. White's classroom on the times that you have

been in there?

A Well, I remember one time, you know, there was just a lot

of paper and children all over the floor and things like

that on several occasions.

Q And did you observe anything else in the classroom so far

as untidiness or uncleanliness?

A Well, she did have some curtains with a lot of boxes and

stuff back of them and the curtains were just thrown up

at that time and the boxes were showing.

Q What was under the curtains?

A Boxes and things like that.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q What kind of boxes are you talking about?

A Well, the only thing I remember are corrugated boxes but

I don't know or did not observe what was in them.

Q What about during the '68-'69 school term, what did you

observe insofar as the appearance was concerned?

A Well, only by passing the door. I didn't have much

occasion to go in her classroom during the '68-'69 schoo .

year.

Q But you say that you did pass the door?

A I did pass the door.

Q What did you observe when you passed the door?

A Well, I observed the children playing and several times

she would be sitting up with her head in her hand like

that.

MR. McCLURE: No further questions.

RECROSS EXAMINATION

BY MR. MARSHALL:

Q You now talk about curtains being hung. Are there close|t

in these rooms?

A Yes, sir, there are.

Q Is there one in Mrs. White's room?

A That's right.

Q Mrs. Brooks, isn't it true that the conduct that you hav|e

described, like the kids talking, this is a normal oc

currence at Pineview, isn't that right, the kids talking';

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A Well, they talk at all schools to a certain degree.

Q In addition, if a person’s head is in his hand, as her

head was in her hand, there’s nothing wrong with that, is

there? I'm sure that your head has been in your hand on

occasion while you have been a teacher at Pineview, is

that right?

A I don't recall.

Q You don't recall, and do I understand you correctly to sa

that you did not visit Mrs. White’s classroom as often

in '68-'69, in that school year?

A That’s right, because we were working on different grades

Q And even paper being on the floor, I'm sure there’s papei

on the floor in your classroom sometimes, isn't that righ

A Yes, but I’ll say that it was a large quantity of paper

on the floor in her room.

Q Did you ask Mrs. White why there was a large quantity of

paper there?

A No, I did not.

Q So you don't know why or how it got there?

A I surely did not.

Q And this was on one occasion?

A That’s right.

Q In ’68-'69 or ’67-'68?

A This was one occasion when I just passed the door in

'68-’69.

42

MR. MARSHALL: No further questions.

REDIRECT EXAMINATION

BY

Q

Q

A

MR. McCLURE:

Mr. Marshall has asked you about kids normally talking.

What degree of noise does the normal talking of children

in the class compare with the degree of noise you heard

in Mrs. White's class?

Well, there was a great degree of noise during that time.

We minimize the talking as much as possible because we

feel that we can do a better job of teaching when we have

less noise.

Is there any doubt in your mind that Mrs. White was

asleep at those times that you observed her?

I would say that she was asleep.

MR. McCLURE: No further questions.

MR. GUARISCO: All right, are there any questions

of the Board? I believe then that we can, without objec

tion, dismiss this witness. You, Mrs. Brooks, may leave

for the day and go about your business. Let's take a

break but before we do, gentlemen, let me say that we

have only had two witnesses in an hour. At the rate we

are going we will be here all night, so let’s see if we

can speed this up and get the pertinent material in the

record but, at the same time, speed it up somewhat. Let'

take about a five or ten minute break.

s

43

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

(BRIEF RECESS WAS TAKEN.)

JUANITA HOLLIS

appeared as a witness and having been previously sworn,

was examined and testified as follows:

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. McCLURE:

Q Would you state your name and address, please?

A Juanita Hollis, 3114 Glenwood Drive.

Q Now, if you would just, in answer to ray questions, take

your time and talk up where everybody can hear you and

talk clear because the air conditioner is going and it is

hard to hear. Where do you woik, Mrs. Hollis?

A Where do I work now?

Q Yes.

A Hartsfield Elementary School.

Q Where did you work prior to that time?

A You mean all the years or just the year prior to this?

Q Just start at the year back of that.

A Pineview.

Q How long did you work at Pineview?

A Two years.

Q What was your job at Pineview?

A Fourth grade teacher.

Q And how long have you been a teacher, Mrs. Hollis?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A About eleven or twelve years.

Q Where did you teach prior to coming to Pineview?

A Bond Elementary School.

Q And prior to that, or was that the beginning of your

teaching career?

A I worked in Georgia, Cairo, Georgia.

Q And how long did you teach school at Pineview?

A Two years.

Q What years was that?

A It was '67-'68 and '68-'69.

Q Do you know Alberta White?

A Yes, I do.

Q And where was your room in relation to Mrs. White’s room?

A For the past year it was right across the hall.

Q What about the year before?

A She was down the hall from me. I don't know just how

many rooms down now.

Q All right, this is a diagram of the school last year.

Would you come to the board and show the Board where youx

room is?

A (Witness to blackboard.) It was right here - - you mean

last year?

Q Yes, here's the office and here's the cafeteria and here

are the restrooms and this is Mrs. White's room. Where

was yours?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

IS

20

21

22

23

24

25

A Right there.

Q Almost directly across the hall?

A Yes, sir.

Q All right, you may be seated. (witness seated.) I would

like to direct your attention to May and June of 1969,

this past school year. During May and June, did you have

occasion to pass by or observe Mrs. White's room?

A Not to observe her room but, you know, just pass by it

and notice it.

Q Did you notice her room from your classroom? Could you

see her room from your classroom?

A If I were directly in front of the room.

Q Did you notice or did you see anything unusual during

May and June of the children or anything like that?

A Not necessarily, no.

Q What, if anything, did you observe of the children cominc

in and out of the classroom or Mrs. White's room?

A I would say for you to be a little more specific about

what you are referring to.

Q Did you have occasion to see the children coming in and

out of Mrs. White's classroom during the school day?

A You mean when they would come in and out from PE or from

music or something of that nature?

Q Then and at any other time while the classes were in

session.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A Not necessarily observe but you could see from time to

time that they would walk in and out of the room.

Q Did you see any of the children coming in and out of the

room while the class was in session?

A Yes, you would see them.

Q Did you ever have any occasion to send Mrs. White’s

children back to her classroom?

A Not necessarily send them back.

Q All right, what occasion did you have to talk with her

children out in the hall, if any?

A Well, once I asked a couple of the children if they knew

where they were supposed to be.

Q Would you explain that to the Board? That’s the point

I’m getting at.

A Well, once or twice I happened to notice the children in

the hall and I happened to know that they were Mrs. White

children, so I just asked them, because I just noticed

them in the hall and I didn’t know why they were there,

I would ask them where they were supposed to be and they

would say - - well, they never would answer me about

where they were supposed to be and I would say, "Well, do

you know where you are supposed to be," and they would

say yes and that was all. I didn’t go directly behind

them to see if they were going where they were supposed

to be or not, but I did mention to them, "Did you know

47

Q

A

Q

A

Q

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9 || A

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

<‘d

Q

where you were supposed to be" and they would say yes.

What did you do when you found out where they were suppos

to be?

I never found out where they were supposed to be.

Did you send them back to Mrs. White’s classroom?

No, I didn’t necessarily send them back.

In your professional opinion is it normal to have children

coming in and out of the classroom a 11 during the day?

That all depends on the purpose for them going in and out

of the room.

MR. MARSHALL: Mr. Chairman, once again there has

been no testimony about children coming in and out of

anybody’s classroom.

MR. McCLURE: Mr. Chairman, I believe she testified

that she did see some out in the hallway and she talked

to them.

MR. GUARISCO: Mr. Marshall, if you have reference

to other witnesses that, of course, has no bearing on

what the other witnesses have said. He asked the questic

earlier and she replied that there were some students ou .

in the hall, that she did see students out of the class

room while classes were in session and I think he -an

pursue and develop that further so I am going to overrule

the objection. Go ahead, Mr. McClure.

In your professional opinion, is it a normal practice fo.

n

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

a teacher to have three or four of her children out all

the time in the halls outside the classroom?

A Well, the way you say it, "all the time" - -

Q Well, during the classroom day.

A As I said earlier, it all depends on why they are out and

I don’t know whether it would be normal or not, but the

way you asked me that question, I'm not sure.

Q Did you see any children out of Mrs. White’s classroom

and in the hall that woJd be in an abnormal situation?

A I really had no way of knowing whether this was abnormal.

Q All right, we won’t pursue that any further. Now, I wouls

like to direct your attention to the spring of 1969, also.

Were you present at a meeting in Mr. Tooks’ office when

Mrs. White was also present?

A Yes.

Q Would you tell or describe to the Board what you heard

the purpose of the meeting to be and the reaction of any

people that were there?

A Well, I can state this briefly but, you know, I can't

give you exactly every detail.

MR. GUARIXO: Let me say this, Mr. McClure, and to

the witness. We would like to get everything we can on

this matter. A woman's job depends on it but, at the sane

time, the reputation for the school system and what is

beneficial for the students is involved. If you have the

49

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

1 answer to these questions don't hedge, give him the answer,

and if you don't have the answer, just tell him you don't

have it, but let’s get the answers out where the record

can show it and we can evaluate it.

Would you testify as to what took place in the room, please.

I was called to the office and when the meeting started,

it was early in the morning sometime but I don't remember

the exact time. To me it appeared that Mr. Tooks wanted

to talk to Mrs. White to tell her some of the things that

he was expecting and that he was displeased with and I

was just sitting there to listen.

Why had you been called into that meeting?

Why had I been called into the meeting?

Yes, uh-huh, were you a grade level chairman or something

like that?

Yes.

Please tell the Board, if you will, what took place and

what you observed.

Well, the best I can remember of what took place is that

when we were called in and Mr. Tooks explained the purpose

of why we were there and the main thing was to tell Mrs.

White of some of the things she was not doing that he

felt she should be doing and, to be specific, I can't

name too many things. I remember one thing that he men

tioned was about the bulletin board and said that she was

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

not working up to what expected of her. In essence, that

what he was talking about and there were several things

said but for me to tell you word for word what was said

I can't do it.

Q Well, all right, just to the best of your recollection.

What was Mrs. White's reaction to this conference with

Mr. Tooks?

A Well, she sat there and she listened for awhile and when

she had an opportunity to defend herself, she did.

Q Would you describe - - did she start crying or anything

like that?

A Well, to me she didn't start crying in there. Of course,

I did see a tear roll down her face.

Q Would you continue, then, and tell us what you saw or wha

you saw or observed until she left the office and then

after that?

A Would you state that again, please?

Q Would you tell the Board what you observed when she

started to respond to to. Tooks, to Mr. Tooks' questions,

and the conversation from the time she started to responc

and when she left the room?

A You mean to be specific about what she said?

Q I don't mean specific, but generally. How did she act

from that time until right after she left the room?

A Well, this was a question that was asked and she was

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

IS

18

17

18

IS

20

21

22

23

24

25

attempting to answer. He would say certain things and

she was trying to answer and give her reasons why she was

doing certain things. She would do this at that particul.

time.

Q Did she become emotional?

A Well, it didn’t appear that she was too emotional in the

office, not to me.

Q All right, what about outside the office?

A Once she left out of the office, she started back to the

classroom and at this time she had tears coming down her

face. I said to her, I said, "Mrs. White, I think it wou

be best for you to go down to the lounge and get yourself

together before you go back to the classroom." She said

that she didn’t want to go to the lounge and she would

prefer going home, or something of that nature that she

said and she stepped in the hall and I still tried to

persuade her to go to the lounge and she wouldn’t do it.

I did not feel that she should let the children see her

crying.

Q Why did you feel like the children ought not to see her

crying?

A I just didn’t feel she should let them see her cry.

Q Was she crying at this point?

A Well, not in an outburst of a cry but the tears were run

ning down her face and, to me, you shouldn’t ever let the

52

3

4

5

6

7

8

9 ! A

10

2

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22 | BY

23

24

25

Q

A

Q

A

Q

A

Q

A

Q

children see you upset in that nature.

What, in your professional opinion, would this have as to

the effect on the children, to see the teacher in this

state?

Well, I don’t know, but I just don't feel you should let

the children know that something was wrong and you certainly

could not be yourself in the classroom.

Did Mrs. White return to her classroom?

Not at this particular time. She did turn and some other

teachers came up and she turned and went to the lounge.

Then where did you go after that?

I went on to my room.

Were any of Mrs. White's students out in the hall or any

thing like that at that time?

Yes, some of her children were there.

Did you see Mrs. White return to the classroom?

Later on I did.

You say later on, was this after she had gone to the lounge?

Yes.

MR. McCLUREs No further quistions.

CROSS EXAMINATION

MR. MARSHALL:

Mrs.Hollis, your room was almost across the hall from

Mrs. White's room during the 1968-'69 school year?

Yes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q Did you have occasion to observe Mrs. White's room and

the general condition of her room from time to time durin<

that school year?

A Not necesarily observe her classroom. If you are saying

had I been in there, yes.

Q You had been in there?

A Yes.

Q On these occasions when you went in was the room untidy

or how would you describe it? What did you see when you

went in there?

A Well, I didn't go in the classroom to see the room but

just walking in I didn't see that it was untidy.

Q How many times would you say that you have gone in the

room during the '68-'69 school year?

A It would be hard for me to answer that specifically.

Q Would it be more than once?

A Yes.

Q More than twice?

A Yes.

Q More than five times?

A I don't know about that but probably so.

Q Now, Mr. McClure asked you about children in the hall anc

you said once that you asked some students to return baci

to Mrs. White's classroom.

A Not necessarily to return but I asked them, you know, wh<

54

were they doing in the hall and did they know where they

were supposed to be.

And did they just leave or did you tell them to go some

place?

No, I didn't tell them to go any place. They just told

me yes, that they knew where they were supposed to go.

But you didn't know why those students were in the hall,

did you?

No.

Now, Mr. McClure said or asked you was it unusual or ab

normal for children to be always in the halls. Did you

see children always in the hall in front of Mrs. White’s

door or near Mrs. White's room?

No.

How many times would you say you saw children near her

room in the hall?

To answer the question, there might have been some childrjen

from other classrooms that would be walking down the hall

as well so it would be hard for me to say how many times

I saw children in the hall by her room.

So there would be children from other classrooms walking

up and down the hall from time to time as a common oc

currence?

Yes.

Now, did you ever, on the times that you were in Mrs. White's

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A

Q

A

Q

A

Q

A

Q

A

Q

A

Q

A

Q

A

classroom, did you ever see her asleep or appear to be

asleep to you?

No.

When you were in the classroom, tell me, is it a common

practice in the Pineview Elementary School to have comme

cial art displayed on the bulletin boards, is that common

Ask that question again.

Is it a common practice for commercial art to be displaye

on bulletin boards at the Pineview Elementary School?

Not necessarily a common practice but you would see some

You would see some?

Yes.

Did you have some in your room?

Yes, some.

And did you see some in any of the other teachers' rooms

that you would go into from time to time?

You would see some.

Now, the times that you went into Mrs. White's room, did

you see any work by the children on the bulletin boards?

Yes, I've seen some children's work.

Now, let me direct your attention to the spring of 1969,

that meeting. Was that the spring of '69 or was that

November of '68 that you are talking about?

Well, to be exact, I wasn't sure what time of the year ii

was but I was told that it was in November. I just know

that it happened during the school term.

Now, let's go back to that meeting. Was there anything

said by Mr. Tooks that would upset Mrs. White or make hei

become emotional?

Well, I couldn't be specific and state anything definite

that was said but, to me, maybe if it was myself and the

person was talking to me that it probably would have ups^t

me some.

It would te/e upset you some?

Yes.

Can you recall specifically what was said or what, in

general, was said to make you upset?

No, I can't think of anything specific.

But you can recall that it probably would have made you

upset had you been the person to whom this was directed t|o?

Yes.

Now, during the '67-'68 and the '68-'69 school years, die

you also see - - you would see Mrs. White, naturally, frem

time to time?

Yes.

Can you recall anything out of the ordinary about her

appearance on these times when you saw her?

MR. McCLUREs Mr. Chairman, I would like to object

56

to that because I don't believe I brought anything out b>

this witness as to her appearance.

MR. GUARISCO: I will sustain that. There was nothirg

on direct in that respect.

MR. MARSHALL: Respectfully, Mr. Chairman, he did go

into occasions when Mrs. Hollis did see students and he

did ask her whether she would come into the room so, ap

parently she did go into the room and apparently she did

because she was the teacher and she would have to see

Mrs. White. That was brought out on direct and the fact

that she was a teacher there for two years and was right

across the hall.

MR. GUARISCO: That’s true, but nothing specific was

in the - -

Could we have that question read back again?

(QUESTION READ BY REPORTER.)

MR. GUARISCO: You are talking about personal appeal-

ance, now?

MR. MARSHALL: Personal appearance, yes.

MR. GUARISCO: Nothing was brought out in that

respect with regard to this witness on direct examination

so I will overrule that. I sustain Mr. McClure but his

request is overruled.

Mrs. Hollis, I believe there were some questions as to

being based on your professional opinion as a teacher -

MR. MARSHALL: I will withdraw that, no further

questions.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21