Williams v. Housing Authority of the City of Atlanta, Georgia Brief in Support of Motions for Permanent Injunction and Summary

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Williams v. Housing Authority of the City of Atlanta, Georgia Brief in Support of Motions for Permanent Injunction and Summary, 1967. 89243f3c-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9d0fb37e-df82-4ed9-9a64-8fd091a10b6a/williams-v-housing-authority-of-the-city-of-atlanta-georgia-brief-in-support-of-motions-for-permanent-injunction-and-summary. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

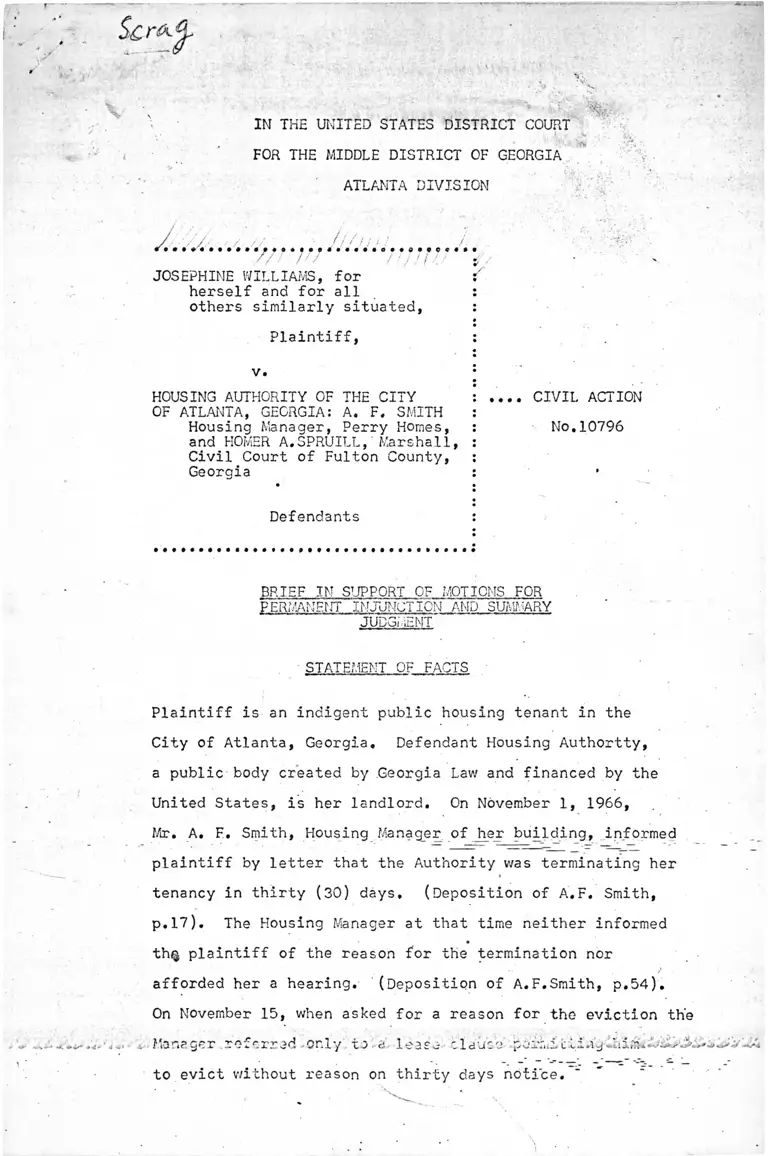

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

A j i , '

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

ATLANTA DIVISION

/ / / // f i > f J 1 :

/// /••/ / •. //

JOSEPHINE WILLIAMS, for

herself and for all

others similarly situated,

Plaintiff,

v.

HOUSING AUTHORITY OF THE CITY

OF ATLANTA, GEORGIA: A. F. SMITH

Housing Manager, Perry Homes,

and HOMER A.SPRUILL, ‘ Marshall,

Civil Court of Fulton County,

Georgia

.... CIVIL ACTION

No.10796

Defendants

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF MOTIONS FOR

P ERMANF.NT INJUNCT ION AND SUMMARY

JUDGMENT

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Plaintiff is an indigent public housing tenant in the

City of Atlanta, Georgia. Defendant Housing Authortty,

a public body created by Georgia Law and financed by the

United States, is her landlord. On November 1, 1966,

Mr. A. F. Smith, Housing Manager of Jeer building, informed

plaintiff by letter that the Authority was terminating her

tenancy in thirty (30) days, (Deposition of A.F. Smith,

p.17). The Housing Manager at that time neither informed

th<$ plaintiff of the reason for the termination nor

afforded her a hearing. (Deposition of A.F.Smith, p.54).

On November 15, when asked for a reason for the eviction the

Manager referred -only to a lease clause perMieLing.ItimLA-AvC^'

to evict v/ithout reason on thirty days notice.

On December 1,1966, plaintiff tendered her rent to the

Housing Authority which returned it with a renewed demand

that she vacate the premises. On December 6, 1966, the

Housing Authority commenced summary eviction proceedings in

the Civil Court of Fulton County pursuant to Georgia Code

Ann. §61-301, et. seqc

"On December S, 1966, her attorney requested by telephone

and telegram a hearing and specification of the grounds

for the notice to vacate and the eviction proceedings.

(Deposition of A. F. Smith, p.53). Defendant Smith did not

reply. Plaintiff tendered to the trial court an affidavit

alleging that her term had not expired and filed a motion

for leave to proceed in forma pauoeris on the ground that

her indigency prevented the filing of the bond with the

security required by Georgia Code §61-303.

The Georgia summary eviction statute, Ga. Code Ann.,

§§301-305, provides that the landlord can obtain an

eviction by filing an affidavit with a judge of the Superior

Court or Justice of the Peace that the tenant has held

over or has failed to pay rent; the judge may then issue a

dispossessory warrant ordering the Sheriff to dispossess the

tenant and his possessions, Ga. Code Ann., §61-302 (1966).

The tenant may arrest the proceedings and prevent his

eviction by filing a courter-affidavit raising a meritorious

defense and tendering a bond with good security payable

to the landlord, for the payment of such sum, with costs,

as may be recovered against him or. the trial of the case.

Ga. Code Ann., §§61-303, 305, 306 (1966). If the tenant

is not able to furnish the security bond, he will be

1/

summarily evicted . •

J 7 Section 303, Title 61, Ga. Code Ann., sets out the

provisions under which the dispossessory warrant

proceedings may be arrested: . ,

"61-303 (5387) Arrest of proceedings-; b y - - t e n a n t - v _

counter-affidavit and bond - the tenant may^arrest

the proceeding and prevent the removal of himself

■ and his goods from the land by declaring on oath

that his lease or rent has .been expired, and that

3

Plaintiff’s motion for leave to proceed without

tendering bond was denied by the Civil Court on February

28, 1967, which simultaneously granted, v/ithout opinion,

the Housing Authority’s motion for summary judgment on the

/

eviction. After the Supreme Court of Georgia and justices

of the United States Supreme Court refused to stay the

eviction, this suit was begun and this court stayed the

eviction to prevent the case from becoming moot pending

a resolution of the issues. During the time this Court’s

temporary injunction has been in effect, plaintiff has paid

rents into the registry of this Court as they have become

due. On April 17, 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court decided

the case of Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham, On

June 9, the Georgia Supreme Court affirmed the decision of

the Civil Court. By this Court’s order of July 28, 1967, th

case has been held in abeyance pending motion by any

party to place it on a calendar.

ARGUMENT

Two distinct issues are raised in this case: (l) the

right of plaintiff, and the class of indigent tenants she

represents, to proceed in forma pauperis, without provision

of bond, in defending against eviction proceedings; and

(2) the right of plaintiff to be given reasons why she

is being evicted from public housing and the manner in

2/

which reasons must be given.

l/continued -

he is not holding possession of' the premises over

% and beyond his term, or that the rent claimed is not

due, or that he does not hold the premises, either

by lease, or rent or at will, or by sufferance, or

otherwise, from the person who made the affidavit on

which the warrant issued, or from anyone under whom

he claims the premises, or from anyone claiming the

premises under him; provided -ucn toianc ehc.il u the

same time tender a bond with good security,- payable to _

the landlord, for the payment of such sum, with costs,

as may be recovered against him on the trial of the

case. (Act 1827, Coff, 902 Acts 1866, p.25)."

Had plaintiff-been allowed to defend her eviction in state

court without payment of the bond, the state court would

have had to rule on her defenses and would therefore have

decided the issues relating to notice and the grounds for

eviction. Plaintiff is in this court because the bond

statute unconstitutionally denies her the right to make

her defenses in state court. As this Court said in its

opinion of March 27, 1967, "The foregoing absence of legal

redress in the state court requires this Court in many

cases, despite its reluctance to do so, to entertain

questions which should more properly be decided by the

Georgia appellate courts."

Unfortunately, despite the stay issued by this court

pending appeal to the Georgia Supreme Court of the under

lying issues and the decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham, nothing has been

resolved. The Georgia Supreme Court refused to rule on

the constitutionality of the bond statute, erroneously

holding that the tenant had been given an opportunity below

to present all of her defenses despite §61-303.

l / continued -

The security referred to above is substantial. Ga.

Code Ann., §61-305 (1966) provides:

"If the issue specified in [§61-304] shall be determined

against the tenant, judgment shall go against him for

double the rent reserved or stipulated to be paid ....

and such judgment in any case shall also provide for

the payment of future double rent until the tenant

surrenders possession of the lands or tenements to the

landlord after an appeal or otherwise..... "

Insurance companies in Georgia have advised that it is

necessary for a tenant to put uo a cash collateral for

double the rent for- about six (6V months,, as well as pay

an unrecoverable bond premium. Williams v. Schaffer,

385 U.S. 1037 at 1038 (Douglas, J., dissenting from

% denial of Writ of Certiorari).

2/ A third issue - the right .of plaintiff not to be

evicted because she has had illegitimate children - is

presented by the record but clearly need not be reached

by this Court.

It then affirmed the Civil Court's order of summary

judgment in favor of the Housing Authority, despite the

fact that together with its ruling on the merits in favor of

the Housing Authority, the Civil Court had denied the

tenant permission to defend the suit. The Georgia Supreme

Court justified the Civil Court’s order of summary judgment

by the assertion that Miss Williams had not fully denied

all of the allegations of the Housing Authority. She did

not do so because the Georgia statute prohibits her from

making her. defenses without posting bond, and the Civil

Court had not (and has not) grafted onto the statute a gloss

permitting indigents to proceed without bond. Plaintiff

did take a deposition which may have been considered by the

trial court, but never fully presented her case because she

never had a right to do so. In fact, it is not even clear

that the Civil Court considered any part of her case. The

Civil Court’s order recited that it was issued "after

hearing argument and considering the pleadings and the

affidavits filed on behalf of both plaintiff and defendant",

but since no opinion was delivered or written it is

impossible to construe this language. It is possible that

plaintiff’s pleadings were "considered" only insofar as the

law (§61-303) permits them to be considered: as one of the

two requisite steps for defending an eviction proceeding,.

the other one being the posting of bond. The denial of

plaintiff’s motion to proceed without bond legally excluded

all of her evidence, preventing the Georgia trial and * .

appellate courts from considering it as part of the record.

Summary judgment for the Housing Authority may have been

granted on the basis of Miss Williams' failure to post bend.

This interpretation cf what, has happened to plaintiff is

supported by the fact that, th^ Civil Court denied, father

than declaring moot, Mass-Williams-’ motion for leave”

proceed without tendering bond.

6 -

At best, plaintiff has had but half a day in court. At

worst, she has been denied altogether the right to defend

her eviction.

The United State Supreme Court's ruling in Thorpe v.

Housing Authority of Durham. 386 U.S. 670 (1967) also

does not resolve any issue in this case. The Court did not

rule on the legality of evicting a tenant from public

housing without assigning any reasons or affording a

hearing. It remanded the case to the courts of North

Carolina for their consideration of the effect of the

federal Department of Housing and Urban Development

circular recommending that tenants be given reasons for

3/

eviction and an opportunity to reply. But plaintiff is not

asking that her eviction be tried on the merits in this

federal court. This Court need not decide whether the

tenant breached her lease or a valid regulation of the

Housing Authority. Plaintiff does pray, however, that this

Court require that the State of Georgia grant her due

process of lav/ before evicting her, and that the defendant

Housing Authority and the defendant Marshall of the Civil

Court be enjoined from evicting her pursuant to any

proceedings undertaken to date.

THE GEORGIA BOND STATUTE VIOLATES THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTITUTION

OF THE UNITED STATES, ON ITS FACE AND AS

APPLIED TO INDIGENT TENANTS.

The requirement of a money bond as a precondition of

defending a lawsuit is a violation of due process of law.

The leading case in Hovev v. Elliot. 167 :U.S.~:409 (1897).

The Supreme Court of the District of Columbia had ordered

defendants to pay into the registry of the court a sum of

money which was at issue in the litigation. The purpose' of

the court's action was to protect the plaintiffs against

dissipation of the funds during the litigation, since

.defendants had already converted the bonds originally at

issue into cash. ..... :.. 7__

27“ See next page

When the defendants refused to pay over the money to the

court, their answer was striken, and a default judgment

entered against them. The United States Supreme Court held

that this action violated due process, for it is in the

fundamental nature of a court that those brought before it

to answer charges be given an opportunity to be heard.

The court quoted from its opinion in Windsor v„ McVeigh.

93 U.S. 274 (1876), that an opportunity to be heard in

court when attacked in court is an essential and inalienable

right:

"Wherever one is assailed in his person or his

property,^there he may defend, for the liability

and the right are inseparable. This is a

principle of natural justice, recognized as such

by the common intelligence and conscience of all

nations. A sentence of a court pronounced against

a party without hearing him, or giving him an

opportunity to be heard, is not a judicial determi

nation of his rights, and is not entitled to respect

in any other tribunal.

That there must be notice to a party of some

kind, actual or constructive, to a valid judgment

affecting his rights, is admitted. Until notice

is given, the court has no jurisdiction in any

case to proceed to judgment, whatever its authority

may be, by the law of its organization, over the

subject matter. But notice is only for the purpose

of affording the party an opportunity of being

heard upon the claim of the charges made; it is

a summons to him to appear and speak, if he has

anything to say why the judgment sought should

not be rendered. A denial to a party, of the

benefit of a notice would be in effect to deny

that he is entitled to notice at all, and the sham

and deceptive proceeding had better be omitted

altogether. It would be like saying to a party:

appear, and you shall be heard; and, when he has

appeared, saying: your appearance shall not be

recognized, and you shall not be heard. 93 U.S.

at 277, 278."

■ The language in both Hovey and 'Windsor may not

cover every case, for there are some occasions when courts

may strike a defendant’s answer. The most common instance

is the ordinary default judgment. Another example is the

power of a federal district court to strike a pleading when

a p’lrty has disobeyed a discovery order. Fed. R.Civ.P.37

(b).(iii). But these are instances'in which defendants who

fail to meet the condition prescribed thereby obstruct the

Circular of February 7, 1967. On remand, the North

Carolina Supreme Court held that the circular had no

retroactive force. Housing Authority of Durham v._

Thorpe, -110.765 (Sept. 25, 1967).

workings of justice,~and'prevent the court from determining

the truth. The present case is much more like Hovey;

itself; the purpose of requiring bond is to guarantee

plaintiffs that they will collect a judgment, if successful.

The purpose of the statute may not be absurd* but the

state’s interest in protecting plaintiffs must be balanced

against, the harm to defendants in tying up their assets

during litigation, before any determination has been made

that they probably will be liable,and without any evidence,

or even any allegation, that if they are not made to pay

the bond, they will flee the jurisdiction or otherwise

divest themselves of money to pay any judgment. The balance

has already been struck by the Supreme Court, when it held

in Hovev that the requirement imposed by the court denied

due process.

Plaintiff recognizes that the Court in Natio.nal Union

of Marine Cooks v. Arnold. 348 U.S. 37 (1954), upheld as

constitutional a defendants’ bond pending appeal. But the

Court did not overrule Hovev. and with good reason. After

a defendant has lost a suit, there is much better reason

to protect a plaintiff. The trial decision suggests at

least that the plaintiff’s case is not frivolous, and it is

more-likely after a trial judgment in his favor than beiore

trial that a plaintiff will ultimately prevail, since at

least some elements which made up the trial judgment

(such as demeanor evidence) are unreviewable. Further,

after judgment against him at trial, a defendant may have

less incentive not to dissipate his assets'. The dissent

id Arnold would have extended Hovev to the appeal process,

but the majority opinion in no way cuts-' back Hoysy.’s.

application, and Hovev squarely governs the present case.

The force of Hovev ~ forbidcing a practice of

depositing money with the court as a prerequisite to

defending a suit - i? no+ diminished bv the fact that states

■ "may require bonds of litigants in some - instaTYSfisy T̂Ke;.-

circumstances in which this is constitutionally permissible

are all distinguishable from those present here.

For example, courts may require a bond of a plaintiff when

there is a particular danger of oppression to the defendant

should he ultimately prevail. A bond may be required of a

stockholder suing derivatively, since there has been a long

history of unfounded ’strike’ suits brought for their

settlement value. See Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial Loan

Coro,. 337 U.S. 541 (1949). And a plaintiff seeking an

interlocutory injunction may be required to post security.

Ga. Code Ann. §81A-165 (a). 3ut these are instances in

which plaintiff’s invocation of the legal process may cause

unwarranted harm to a defendant, whereas in the present

case, the bond is required of a defendant who is involunt

arily brought before the court. Similarly, a plaintiff

seeking garnishment must post bond, Ga. Code Ann. §§8-112,

46-102, but the purpose of such bond is also to safeguard

the unwilling garnishee.

Defendants, too, may be required to post some bonds,

but the situations in which such bonds may be required are

strictly limited. Bail bonds may be required of criminal

defendants, but their purpose is simply to assure the

defendant’s presence at trial; unlike the bond required by

§61-303, failure to post bond does not preclude the

defendant from making his arguments. And the bond required

of a defendant wishing to leave to state despite a writ of

ne exeat, see Ga. Code Ann. §37-1403, pertains only to

def endants who are about to remove their -persons,- or—property. -

from Georgia; in the case of tenants willing to pay rent

into court during the course of eviction proceedings, no

comparable injury to plaintiffs is conceivable. Unlike other

bor̂ l situations, the present case is on all fours with

Hovey: a requirement that a defendant pay a sum into court

for the protection of the plaintiff, before being heard

at all, with no showing that the plaintiff is especially

threatened by defendant's proceeding without bond.

The Georgia requirement, in fact, is if anything far

more obnoxious than the bond disapproved in Hovey, for

Georgia’s is a penalty bond, which requires the posting of

double rent, far more than is necessary to protect a

landlord from anything. Though a state design to protect

prevailing landlords might reasonably be weighed against

the rights of tenants, a policy of punishing persons for

defending a lawsuit, regardless of their good faith in

doing so, deserves, we submit, no weight at all.

Even if there are some circumstances in which courts

can require some defendants to post a bond before being

allowed to make a defense, a money bond cannot be demanded

of an indigent. A requirement such as Georgia’s permits

wealthy persons to stay in rental housing and defend eviction

proceedings, while denying impoverished persons any

opportunity to present to a court even the most airtight

defense.

It is no answer to say that no significant damage

is done. Subsequent suits for wrongful eviction are of

little value to the poor, who are shunted around from

inadequate dwelling to another at the mercy of landlords.

"The poor are relegated to ghettos and are beset by sub

standard housing at exorbitant rents. Because of their

lack of bargaining power, the poor are made to accept

onerous lease terms. Summary eviction proceedings are

the order of the day. Default judgments in eviction

proceedings are obtained in machinegun rapidity, since the

indigent cannot afford counsel to defend. Housing laws

often have a built-in bias against the poor. Slumlords

h^ve a tight hold on the Nation, "Douglas, J., in Wi ll_iams

v. Schaffer. 385 U.S. 1037 (1967) (dissenting from denial

of writ of certiorari in a previous case challenging this

• which was held moot by the Georgia Supreme Court

because the tenant had already been evicted):^ ^ -.7-

11 -

It may be that states can constitutionally enact

some legislation which creates a greater burden for the

poor than for the rich. Arguably, it is not impermissible

for the states to charge fees for licenses of various sorts,

or to require tuition of students at state university.

But Griffin v, Illinois. 351 U.S. 17 (1956)make it clear that

justice may not be sold.

Surely no one would contend that either a State

or the Federal Government could constitutionally

provide that defendants unable to pay court costs

in advance should be denied the right to plead

not guilty or to defend themselves in court. Such

a law would make the constitutional promise of a

fair trial a worthless thing, Notice, the right

to be heard, and the right to counsel would under

such circumstances be meaningless promises to the

poor ......There is no meaningful distinction

between a rule which would deny the poor the right

to defend themselves in a trial court and one which

effectively denies the poor an adequate appellate

review accorded to all who have money enough to

pay- the costs in advance..There can be no

equal justice where the kind of trial a man gets

depends on the amount of money he has. 351 U.S. at

17-19.

It is true that Griffin:s prohibition on economic

discrimination by the state has been applied up to now

chiefly to the criminal process. See Burns v. Ohio. 360

U.S. 252 (1959). Smith v. Bennett. 365 U.S. 708 (1961).

But the equal protection clause, upon which Griffin was

based, applies as well to matters denominated "civil",

and Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections. 383 U.S.

663 (1966), invalidating the application .of a poll tax to

indigents, demonstrates that the exercise of important

rrights other than ones relating to the .criminal.process_ .

may not constitutionally be conditioned on ability to pay.

In fact, the Supreme Court very recently reaffirmed

the principle of non-discrimination against the poor in the

le^hl process, in language which apparently applies to any

civil proceeding: "Our decisions for more than a decade

now have made clear that differences in access to the

instruments needed to vindicate legal rignts, wnen cased

on the financial situation of the defendant, are repugnant

to the Constitution". . ...

12 -

Roberts v. Lavallee, 36 L.W. 3171, 3172 (October 23, 1967).

See also Williams v. Schaffer. 385 U.S. 1037, 1039 (1967)

(dissent from denial of writ of certiorari). This is

perfectly sensible, since the ability to pay bears no more

rational relation to whether one has a bona fide defense

to an eviction proceeding than it does to whether he has a

bona fide ground for the appeal of a criminal conviction.

And it is no exaggeration to say that given the type of

housing available to the poor, the consequences of eviction

to an indigent family may be as serious as the consequences

of a criminal conviction. Under the equal protection clause

the relevant constitutional consideration is whether the

bond requirement bears a sufficiently reasonable relation

to a valid legislative purpose. As a means of discriminating

between valid and frivolous defenses,the requirement cannot

stand; poor persons are barred from defending no matter

how valid their defense, and wealthy persons with frivolous

defenses are already subject to the requirement that they

make their defense by affidavit. Ga. Code j61-303; the

making of a false affidavit pursuant to this requirement

constitutes criminal perjury. See Sistrunk v. State of

Georgia. 18 Ga. App. 42, 88 S.E. 796 (1916). Somewhat more

reasonable is the relationship between a bond requirement

and the protection of prevailing landlords from loss of rent

during protracted litigation. But if that is the purpose

of the law, the means Georgia has adopted sweep too broadly

and-stifle the right to defend a lawsuit^-"Thei_breadth of

legislative abridgement must be viewed in the light of less

drastic means for achieving the same basic purpose"#

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (i960). See also NAACP v.

Alabama, 377 U.S. 288 (1964); Bates v. City of Little Rock.

361 U.S. 516 (1960); McLaughlin v. Florida. 379 U.S. 184

(1964). Many simple devices exist by which the state could

safeguard both' the-landlord-s rent during a.̂ suit and-Jtha^.^.

tenant’s right to challenge the eviction.

For example, the state could simply retain the "summary"

nature of summary process, by giving eviction suits

priority on the dockets of its courts and affording land

lords the right to have their suits heard within a week of

service of a notice of eviction. Or Georgia could permit

tenants to pay landlords their rent during the pendency of

the proceedings, and condition the making of a defense on

the continued payment of rent, rather than on the posting

of a large bond which indigents cannot raise. In cases of

dispute over whether or not rent has been paid, tenants

might be reluctant to continue to pay rent to the landlord

until the issue was resolved, but the court with jurisdiction

over the eviction suit could collect the rents for the

landlord or certify payments, Given these and other

alternatives, Georgia's present method of protecting land-

/

lords' rents interferes too severelywith the rights of

4/

indigent tenants to obtain elemental justice .

BECAUSE OF THE BOND STATUTE, THIS

PLAINTIFF HAS NEVER HAD AN OPPORTUNITY

TO DEFEND HER EVICTION IN STATE COURT.

The Georgia Supreme Court refused to rule on the

constitutionality of the bond statute "since the [plaintiff]

has been given an opportunity to present all the defense

which she could have presented if she had filed the bond

required by Code §61-303." The court’s analysis of the

facts was erroneous. As noted above, there was never

a time during which plaintiff was affordecT”alright To-defend

the eviction. The statute denied her such a right, and

the civil court judge confirmed the denial by his order

denying her leave to proceed in forma pauperis. Such

evidence as she proferred constituted an attempt to show,

before being cut off by invocation o-f the bond statute,

that her constitutional argument, was not frivolous? it was

not a full argument. . V - < i = ~

4/ See next page

Equally important, perhaps, in demonstrating that plaintiff

has not had a day in court, is the fact that she was put in

the position of having to defend an eviction proceeding

without being told the reasons for the eviction. On

July 27, 1966, four months before eviction proceedings were

begun, defendant Smith discussed with plaintiff the alleged

unsuitability of her moral behavior and told her that "while

she may be living an exemplary life, I had no way of.knowing".

(Deposition of A.F. Smith, p.37). The conversation at this

time was vague and not related to legal proceedings. A

second meeting between plaintiff and defendant Smith took

place on November i5, 1966, after the notice to vacate had

been given, but on this occasion Mr. Smith refused to give

plaintiff any reason for her eviction, except to say that

she was being evicted under Section 9(A) of her lease, which

gives the Housing Authority power to evict tenants without

5/

cause on thirty days’ notice ^Deposition of A.F.Smith,

pp.47-49). As Judge Tuttle pointed out during the hearing

in this case on March 17, 1967, defendants have conceded

that the Housing Managers may waive the various grounds for

eviction based on misbehavior (Transcript, p.79). Discussions

between the Housing Manager and the tenant, four months

prior to the notice of termination, cannot be relied on by

the Housing Authority as a substitute for a clear statement

or reason at the time the Housing Authority acted to terminate

the lease.

Georgia recognizes the unfairness of requiring indigent

litigants to post bond in order to make their-argument;

indigents may apply for certiorari in forma pauperis under

Ga. Code Ann. §19-203. But Georgia has not seen fit to make

this principle meaningful to indigent tenants - they may

appeal without bond by certiorari but may not defend the

eviction at the trial level.

5/ ^ "Judge Tuttle:.... Mr. Satterfield, do you mean to

say that without any instructions or limitations from your

office or from any national headquarters, you give to the

Managers of these different projects an absolute, unfettered

discretion to elect to exercise the thirty days notice and

eliminate a tenant if he thinks according to his judgment

and discretion that tho hehrn+ oMchh t- be a7 t

The Witness: X wouldn’t put it in;.justrthose_worHsv>f-:

but I think that's probably true. We have confidence that

our Manager is going to use good judgment."

(Transcript of hearing, p. 42)

15 -

Plaintiff was-not told which of the reasons that had been

given to her informally were being relied upon, and which

of them waived.

Plaintiff's memorandum of lav/ in the civil court

attempted to cover briefly each of the possible grounds for

r

eviction. Plaintiff expected that at the trial, at the

latest, she would be informed of the grounds relied upon,

so that she could present an exhaustive defense directed

at the relevant issues. As a result of the bond requirement,

however, plaintiff has still not been afforded an opportunity

to respond to her landlord's case. Trial in open court has

never been held because the civil court granted the

landlord's motion for summary judgment; that motion was

granted on the basis of argument which was incomplete

because the bond requirement prevented the tenant, both

legally and practically, from making all of her defense.

Plaintiff still has good cause to complain of Georgia

Code §61-303, and is still entitled to a full adjudicative

hearing before being put out of her apartment.

Furthermore, this suit is a class action on behalf

of tenants who are too poor to put up the bond required

by Ga. Code §61-303, and the other members of the class that

the named plaintiff represents are seriously aggrieved by

the statute of which she complains. The Georgia Supreme

Court contended that the named plaintiff was able to make

a defense despite the bond statute; that she in effect

successfully and lawfully evaded the -statute.-~If she_--di-d

so (and, as noted above, it appears that she did not), it

v/as only by a combination of good fortune and the grace of

the Civil Court of Fulton County. This particular named

plaintiff, unlike most indigent tenants in Atlanta, v/as

fortunate enough to have the assistance of volunteer

counsel; her lawyer, although faced with the statute which

-seemed to deny him all right to defend the -suit ̂ unless.-hi- -

client posted bond, asked permission of the court to be

- 16 -

allowed minimum discovery to prevent surprise at a trial

at which he expected to be able to attack the bond statute

itself, among other things; the court, perhaps because this

was a novel case raising constitutional issues, granted a

discovery order; and the Civil Court stayed the eviction

until a deposition could be taken and the case arguedo But

the ordinary member of the class that plaintiff represents

is not so fortunate, and is simply evicted when no bond

is posted. Plaintiff did not manage to "evade" the bond

requirement, but even if she did, the member of her class

have neither the opportunity nor the right to do so.

THE NAMED PLAINTIFF SHOULD BE PROTECTED

BY AN ORDER RESTRAINING HER EVICTION

UNTIL IT SHALL HAVE BEEN DETERMINED,

PURSUANT TO DUE PROCESS OF LAW, THAT

SHE IS NOT ENTITLED TO OCCUPY THE PREMISES

An order restraining further enforcement of Ga. Code

§61-303 will protect the named plaintiff as well as members

of her class from future eviction proceedings in violation

of due process and equal protection, but it will pot suffice

to prevent injustice to Miss Williams. A notice to

vacate was served upon her last December, and the state

has afforded her, in form though not in substance, a

judicial determination of her claims. She may be evicted

as soon as the temporary restraining order now in effect

is dissolved. Minimal protection for her right to a full

and fair proceeding necessitates that this court restrain

defendant Housing Authority from evicting_her_until she is_

given a determination of her claims in a manner comporting

with the requirements of due process. This court need not

require Georgia to adopt any particular form of process, so

lor̂ g as constitutional requirements are met. Since the

determination of whether or not plaintiff may be evicted

involves the adjudicative process, plaintiff is entitled to

•

"an opportunity to know the_ claims ot tne opposing party, .«

to present evidence to support [her] contentions .... and

Seeto cross^e.xamine witnesses __for the other side".

Hornsby v. Allen. 326 F. 2d 605, 608 (5th Cir. 1964). "The

deciding authority may not base its decision on evidence

which has not been specifically brought before it.... ;

the findings must conform to the evidence adduced at the

hearing, [and the adjudicative decision] cannot be upheld

merely because findings might have been made and considera

tions disclosed which would justify its order". Ibid.

Thus, Georgia may not wish to grant plaintiff a full

trial in gpurt. Since plaintiff’s landlord is a public

body, Georgia may satisfy the requisites of due process by

affording her an administrative hearing conducted by a

neutral officer of the Housing Authority, but such a hearing

must contain the elements enumerated above, and the state

must provide some judicial review of alleged errors of law

committed by the administrative tribunal. On the other

hand, if the state wishes to provide a judicial forum for all

tenants, in public and private housing, who wish to contest

evictions, it is submitted that the constitutional standards

imposed on the judicial adjudication are no less strict

than those which Hornsby imposes upon administrative bodies.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, plaintiff and the members

of the class she represents should be granted the relief

requested in their motion for permanent injunction.

- - Respectfu11 v^submltled, - —_U-

HCWARD MOORE," JR. .

859k> Hunter Street

Atlanta, Ge’orgia 30314

JACK GREENBERG ' •

CHARLES H.'JONES, JR.

CHARLES S. RALSTON

MICHAEL DAVIDSON

• 10 Columbus Circle

New .York, New York 10019 _ . __

Attorneys for Plaintiff