Order Granting Request for Judicial Notice

Public Court Documents

July 2, 1986

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Order Granting Request for Judicial Notice, 1986. d0362e3b-bad8-ef11-a730-7c1e5218a39c. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9d1a2f06-abce-4cd4-a31b-f7fc30033ba5/order-granting-request-for-judicial-notice. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

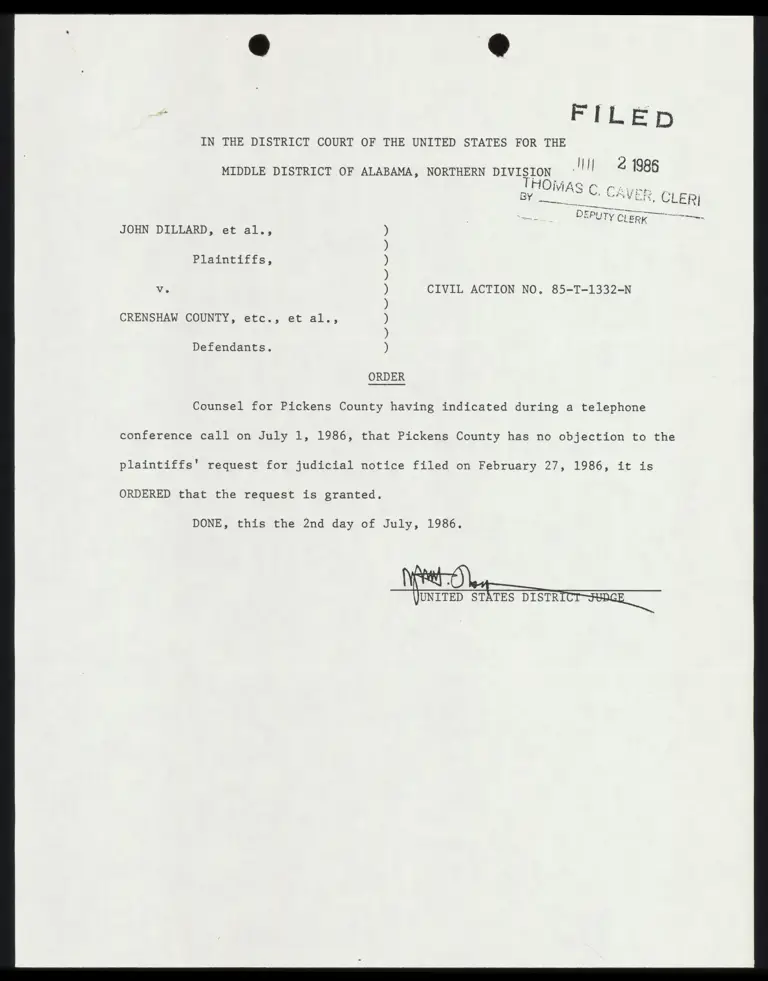

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE

| [4

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, NORTHERN DIVISION 2 1986

THOiAS Cro tives,

BY rr LL LIER

Tes £2 PUTY Clerk ssi ————

JOHN DILLARD, et al., )

)

Plaintiffs, )

)

v. ) CIVIL ACTION NO. 85-T-1332-N

)

CRENSHAW COUNTY, etc., et al., )

)

Defendants. )

ORDER

Counsel for Pickens County having indicated during a telephone

conference call on July 1, 1986, that Pickens County has no objection to the

plaintiffs' request for judicial notice filed on February 27, 1986, it is

ORDERED that the request is granted.

DONE, this the 2nd day of July, 1986.

\JUNITED STATES DD

OFFICE OF THE CLERK fo <\ | | ne

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT { wh 3. gil

P.O. BOX 711 t= if

MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 36101

OFFICIAL BUSINESS

PENALTY FOR PRIVATE USE $300

x ~ / rt . i om oy

kg

POSTAGE AND FEES PAID

UNITED STATES COURTS

usc 426

Hon. Deborah Fins

Hon. Julius Chambers

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

99 Hudson Street

l6th Floor

New York, NY 10013