Curry v. Dallas NAACP Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

May 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Curry v. Dallas NAACP Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae, 1979. b559bcc7-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9d9a02fe-5fcc-4ce7-a0a3-e8db45614fba/curry-v-dallas-naacp-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

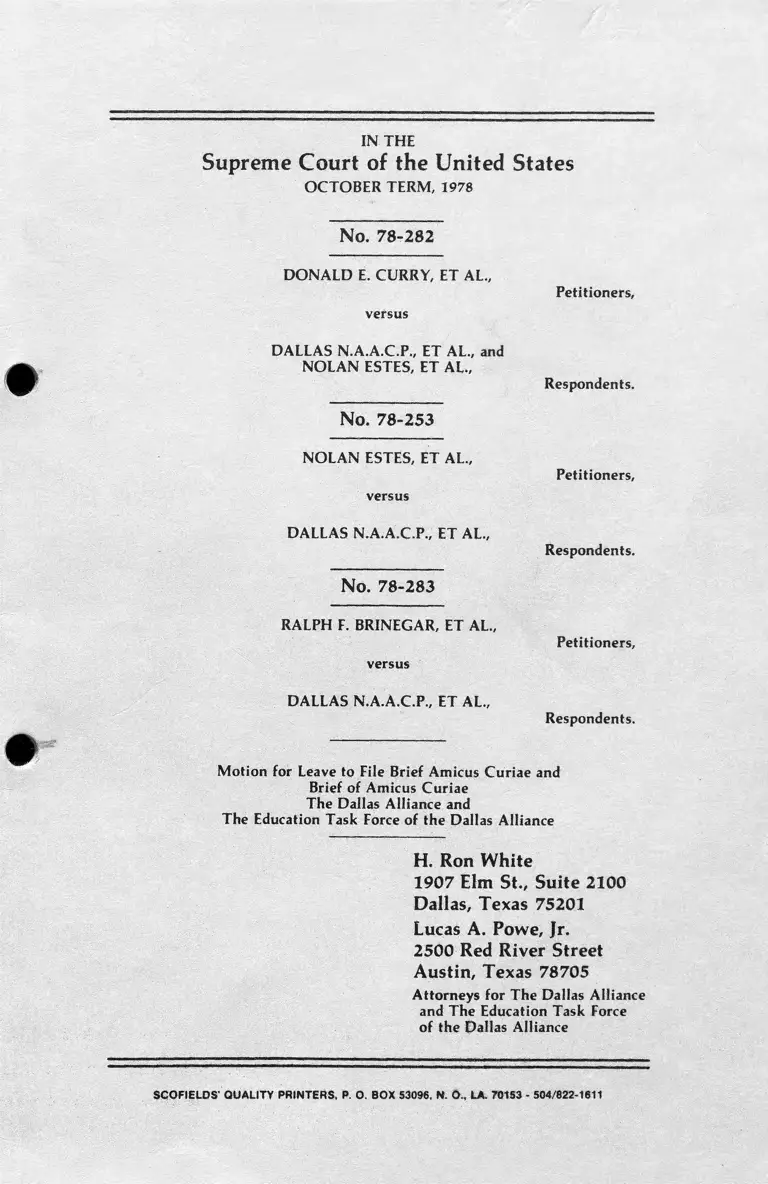

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 78-282

DONALD E. CURRY, ET AL.,

versus

Petitioners,

DALLAS N.A.A.C.P., ET AL., and

NOLAN ESTES, ET AL.,

No. 78-253

Respondents.

NOLAN ESTES, ET AL.,

versus

Petitioners,

DALLAS N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.,

No. 78-283

RALPH F. BRINEGAR, ET AL.,

versus

DALLAS N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.,

Respondents.

Petitioners,

Respondents.

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae and

Brief of Amicus Curiae

The Dallas Alliance and

The Education Task Force of the Dallas Alliance

H. Ron White

1907 Elm St., Suite 2100

Dallas, Texas 75201

Lucas A. Powe, Jr.

2500 Red River Street

Austin, Texas 78705

Attorneys for The Dallas Alliance

and The Education Task Force

of the Dallas Alliance

SCOFIELDS' QUALITY PRINTERS, P. O. BOX 53096, N. O., LA. 70153 - 504/822-1611

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 78-282

DONALD E. CURRY, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

versus

DALLAS N.A.A.C.P., ET AL., and

NOLAN ESTES, ET AL.,

Respondents.

No. 78-253

NOLAN ESTES, ET AL.,

versus

Petitioners,

DALLAS N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.,

Respondents.

No. 78-283

RALPH F. BRINEGAR, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

versus

DALLAS N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.,

Respondents.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE FOR

THE DALLAS ALLIANCE AND THE

EDUCATION TASK FORCE OF THE DALLAS ALLIANCE

M OTION FOR LEAVE

TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

The Dallas Alliance and the Education Task Force of

the Dallas Alliance hereby respectfully move for leave

to file the attached Brief Amicus Curiae in this case

pursuant to Rule 42 of this Court. The consent of at

torneys for the petitioners and for the respondents,

Tasby, et al, has been obtained and the letters have

been deposited with the Clerk. The consent of the at

torney for the respondent NAACP was requested but

refused.

The Dallas Alliance is a service organization de

signed to encourage cooperation and combined effort

of community groups in seeking resolution of urban

problems affecting the Dallas community. The Alliance

is comprised of a 40-member Board of Trustees drawn

from local government, the business sector, and the

community at large. The Board's racial composition

reflects the ethnic makeup of the city's population. In

addition, approximately 90 community organizations

are affiliated with the Alliance, designated as com

munity correspondent organizations.

The Education Task Force of the Dallas Alliance was

formed in October, 1975. Consisting of seven Anglos,

seven Mexican-Americans, six Blacks and one

American Indian, the group's mission was the creation

of a consensus school desegregation plan which would

be constitutionally acceptable. The Task Force im

mediately commenced an energetic and exhaustive in

volvement in the drafting process. After more than

four months and 1500 work hours, including

num erous conferences with leading educators

throughout the Nation, the Task Force was able to

agree on a consensus plan. This plan was then sub

mitted to the district court in the middle of the month

of remedy hearings. The district judge subsequently

adopted the plan of the Task Force (with modifications)

as his final order in the case.

In both the district court and the Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit the Task Force has participated as

Amicus Curiae in support of the consensus plan. The

Task Force's familiarity with this case, with DISD, and

with the concepts the district judge ordered place it in a

unique position to be of assistance in fleshing out the

issues involved in this complex urban desegregation

suit. Furthermore, the Task Force believes it likely that

the other briefs may argue this case on grounds

broader than necessary for an appropriate resolution of

the controversy.

Therefore, The Dallas Alliance and the Education

Task Force of the Dallas Alliance respectfully move for

leave to file the attached Brief Amicus Curiae.

Respectfully submitted,

H. Ron White

1907 Elm St., Suite 2100

Dallas, Texas 75201

Lucas A. Powe, Jr.

2500 Red River Street

Austin, Texas 78705

Attorneys for the Dallas

Alliance and the

Education Task Force

of the Dallas Alliance

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae

in Behalf of The Dallas Alliance and the

Education Task Force of the Dallas Alliance ----- i

Table of Authorities ...................................... vi

Interest of Amicus C u r ia e ................................................ 2

Introduction and Statement of the C a s e .....................2

A. The Narrow Issue ............................................. 2

B. Demographic History of Dallas ........... .. 4

1. Black Movement 1940-70 .........................5

2. Anglo Movement 1940-70 . . . . . . . . . . . 7

3. Mexican American Movement

1940-70 ........................................................ 8

4. The P re se n t.................................................. 8

C. The District Court's O r d e r ........................ 9

Summary of Argument ............................... 14

Argument ................................................ 15

I. The District Judge Appropriately

Exercised the Broad Discretion

Necessary to Implement a Desegrega

tion P la n .............................................................. 15

II. Washington v. Davis and Its Progeny

Have No Place in a Southern School

Desegregation C a s e ............................................26

C onclusion........................................................................... 28

Proof of Service ....................... 29

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued)

Page

Appendix A: Plate Maps Showing Racial

Composition of Dallas, 1940-70 ............................ la

Appendix B: Dallas Census Tract Statistics

by Race, 1940-70 ........................................................ 6a

Appendix C: Community Organizations Af

filiated with The Dallas Alliance ........................ 16a

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

CASES

Ashbacker Radio Co. v. F.C.C., 326 U.S. 327

(1945) .................................................... 20

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 494

(1954) ............................................................................. 16

Brown v. Board of Education II, 349 U.S. 294

(1955) .............. 3,16,20,27,28

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of

Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33 (1971) ........................ 22

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 433

U.S. 406 (1977) ........................................................ 15

Green v. New Kent County School Board, 391

U.S. 430 (1 9 6 8 ) ..............................3,4,16,25,27

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) . 16

Milliken v. Bradley II, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) . . . 14,16,

22,23,24

Morgan v. Hennigan, 379 F. Supp. 410 (D.

Mass. 1974) 14

Morgan v. Kerrigan, 509 F. 2d 580 (CA 1

1974) ................................................................... 14

Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler,

427 U.S. 424 (1 9 7 6 ) .................................................... 18

Singleton v. jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 419 F.2d 1211 (CA 5 1970). .12-13

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ..................4,13,16,17,

19,27,28

Tasby v. Estes, 412 F. Supp. 1192 (N.D. Tex.

1976) .............................................................. 10,11,13,22

Tasby v. Estes, 572 F. 2d 1010 (CA 5 1 9 7 8 ) ...........15

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) . . 2,26,27

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Bell, Serving Two Masters: Integration Ideals and

Client Interests in School Desegregation Litigation,

85 Yale L.J. 470 (1976) ......................... 16

Bickel, Education in a Democracy: The Legal and Prac

tical Problems of School Busing, 3 Human Rights

53 (1973) ....................................................................... 18

K. Clark, A Possible Reality: A Design for the Attain

ment of High Academic Achievement for Inner City

Students (1972) ........................................................ 19-20

Hain, Sealing off the City: School Desegregation in

Detroit, in H. Kalodner & j. Fishman eds.,

The Limits of Justice 233 (1978)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED (Continued)

Page

. . 21

Mays, Comment: Atlanta — Living with Brown

Twenty Years Later, 3 Black L.J. 184 (1974)- . . . . . 23

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Fulfilling the

Letter and Spirit of the Law (1976) ...................... 16,25

Willie, The Sociology of Urban Education, 59-76,

Lexington Books of D.C., Heath Company

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED (Continued)

Page

(1978) ............................................................................. 11

Willie, Racial Balance or Quality Education?, 84

School Rev. 313 (1976) .............................. .. . 14,16,22

Yudof, School Desegregation: Legal Realism, Reasoned

Elaboration, and Social Science Research in the

Supreme Court, 42 Law and Contemp. Probs.

(Spring 1978) (forthcoming) ....................... .. 20

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 78-282

DONALD E. CURRY, ET AL„

Petitioners,

versus

DALLAS N.A.A.C.P., ET AL„ and

NOLAN ESTES, ET AL.,

Respondents.

No. 78-253

NOLAN ESTES, ET AL„

versus

Petitioners,

DALLAS N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.,

Respondents.

No. 78-283

RALPH F. BRINEGAR, ET AL.,

versus

Petitioners,

DALLAS N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.,

Respondents.

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

THE DALLAS ALLIANCE AND THE

EDUCATION TASK FORCE OF THE DALLAS ALLIANCE

2

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Dallas Alliance is a service organization designed

to encourage cooperation and combined effort of com

munity groups in seeking resolution of urban problems

affecting the Dallas community. The Alliance is com

prised of a 40-member Board of Trustees drawn from

local government, the business sector, and the com

munity at large. The Board's racial composition reflects

the ethnic makeup of the city's population. In addition,

numerous community organizations are affiliated with

the Alliance, designated as community correspondent

organizations. (A list appears in Appendix C).

As stated in greater detail in the Motion for Leave to

File Brief Amicus Curiae, the Education Task Force of the

Dallas Alliance is a tri-ethnic group that labored for

1500 hours in developing the consensus plan that was

subsequently adopted by the district court in its final

order.

IN TRODUCTION AND

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. The Narrow Issue

The most far-reaching issue presented in this litiga

tion and briefed to the Court is an issue which neither

the district court nor the Court of Appeals decided:

whether the principles of Washington v, Davis, 426 U.S.

229 (1976) should be interjected into school desegrega

tion litigation in the urban South. Not only was this

issue not faced below, it need not be faced here. Instead

this case may be decided on the very traditional

grounds of the discretion of a district judge. To say that

the issue is traditional, however, is hardly to trivialize

it. The vast urban setting of the eighth largest school

system in the United States heightens its importance

and provides a unique focus for exploring the

parameters of informed discretion.

Brown v. Board of Education II, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) placed

a special burden on district judges. Not only were they

to be in the vanguard of Southern desegregation, but in

so doing they were to demonstrate "a practical flexibili

ty in shaping remedies and. . . a facility for adjusting

and reconciling public and private needs." Id. at 300.

The duty to reconcile has lost none of its importance

over time even though the context for the application

of the duty has changed markedly. Thus, thanks to

Green v. New Kent County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968)

and its immediate progeny, by 1970 rural desegrega

tion was complete. But the harder task, that of

desegregating the urban systems was barely begin

ning. The cries of nullification and interposition from

Louisiana and Virginia had been stilled only to be

replaced by the shouts from Boston and Louisville. The

quaint names of the rural South vanished, to be replac

ed by the more familiar nomenclature of urban

A m erica: C h arlo tte , Mobile, Denver, Detroit,

Pasadena, Dayton. But still, throughout all the

changes, it remains the federal district judges who bear

the primary burden of implementing the appropriate

constitutional principles. To them falls the often

thankless work; to “grapple with the flinty, intractable

realities of day-to-day implementation" of school

desegregation. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1, 6 (1971).

A district judge, however, must do more than grap

ple. He must decide. And in so doing he must imple

ment a desegregation plan that "promises realistically

to work." Green, 391 U.S. at 439. In a large, urban, tri

ethnic community such as Dallas, where thousands of

citizens are relocating their homes annually, the ap

propriate choices are hardly self-evident. Yet they

must be made.

The starting point for any desegregation plan is

determining where the children live. This litigation has

been protracted and each time the case has come before

the district court substantial demographic changes

have occurred. If nothing else, Dallas has been an ur

ban boom town. A brief look at its demographic history

is essential for understanding the setting.

B. Demographic History of Dallas

In the thirty year period (1940-1970) Dallas changed

radically. There were population changes in size, loca

tion, economic characteristics, composition by race and

eth n icity , as well as school age population

characteristics. To a large extent Dallas is a new city,

suburban in its development pattern with single,

detached dwelling units being the dominant form of

5

housing until very recently. Population densities by

tract are low in comparison with northeastern and

even other southern cities.

Since 1940 the physical size of the city and DISD

have both quadrupled to well over 350 square miles of

territory. The growth came largely in two major

spurts, one in the early 1950's and the other in the early

1960's.

To understand this growth in physical size and pop

ulation some understanding of the physical and social

geography is necessary. The core of the city is along the

Trinity River. On the north side of the river the land is

flat and in 1940 most (75%) of this area was planted in

cotton in farm plats of approximately 80 to 100 acres.

To the south is the Oak Cliff area which has rocky soil

and a hilly type of terrain not suitable for industry or

agriculture.

1. Black Movement— 1940-70

In 1940 75% of the small Black population lived in

two areas of the city: immediately to the north of the

Central Business District and to the far southeast of

the Central Business District.1 Both of these areas are

now completely surrounded by new areas. The re

maining 25% of the Black population was more dispers

ed and only 10 of the 58 tracts in the city at that time

had fewer than 1% Black population.2

1 Plates of Dallas in 1940, 1950, 1960, and 1970 showing racial

percentages are in Appendix A.

2 Census tract statistics are in Appendix B.

6

The pattern of racial location in 1950 remained es

sentially the same with the exception of major

territorial annexation to the north and south with

many more Anglo tracts.

In 1957 a major annexation of a West Dallas district

occurred. This area had two barrio areas, few Anglos

and substantial Blacks. At the time of annexation

this area, located in the west between Oak Cliff and

North Dallas, had less than 11% of the housing above

code, only 2 miles of paved streets, one 60 year-old

school building, no parks, no sewers, no storm drains.

During the huge growth of the 1950's the city's pop

ulation and territory more than doubled. Black location

concentration moved into the area identified as South

Dallas (just north of the Trinity River). This was an

older area being abandoned by Anglos moving to the

far north of Dallas. A concentrated group of census

tracts changed during the 1950's from Anglo to Black.3

While Black population was doubling, the rapidly ex

panding Anglo population resulted in the DISD being

15-20% Black.

The area known as East Oak Cliff had 65% of its pre

sent housing built during this period. It was in 1960 a

series of suburban type development subdivisions.

Black residents were in two zones of this area of the

city — in the older housing in far northeast Oak Cliff

directly across the Trinity River from South Dallas on

the only bridge and to the far south where Bishop

College was placed after moving from Marshall, Texas.

3 Tracts 28, 29, 33, 34, 36, 38, 39.02, 40 and 41.

7

Within a three year period of the 1960's a tremen

dous change, one with no Northern or Eastern city

comparisons, took place in the recently developed sub

divisions of East Oak Cliff — the area south of the river

and east of Interstate 35E. While originally built for and

marketed to Anglos, the average Anglo occupancy was

but 2.3 years. Almost two dozen census tracts in the

area shift from 90% Anglo to 90% Black.* Six of these

tracts did not exist in 1940; four did not exist until

1970. In effect a new area of the city, with new schools,

new streets, new shopping centers (the first two major

centers in Dallas were built in this area) went from

Anglo to Black overnight.

2. Anglo Movement— 1940-70

Anglo movements in this 30 year period show a

different pattern to the fringes of the city — far

northwest, northeast, east (Pleasant Grove) and far

southwest. The growth was phenomenal and demon

strates the recency and amount of post-war affluence

in Dallas. While Blacks were coming from Louisiana

and East Texas rural areas, for working class oppor

tunities, Anglo Dallas in its affluence was coming from

the upper midwest for corporate and financial oppor

tunities. This wealth concentrated in the far north area

and is, again, in housing not even there in 1950.

F u r t h e r , t r e m e n d o u s suburban expansion,

predominantly Anglo, took place around the city. 4

4 Tracts 49, 54, 55, 56, 57, 59.01, 59.02, 71.02, 86, 87.01, 87.02,

88, 89, 103, 104, 112, 113, 114.01, 114.02, 167.01, 169.01.

8

3. Mexican American Movement — 1940-70

While there is no census data on Mexican American

location, an area north of the Central Business District

by 1940 was called "Little Mexico" and the few Mexican

Americans in Dallas were concentrated there. Most of

the Mexican American population has come to Dallas

during the current decade and is concentrated in an arc

from West Dallas to East Dallas directly north of the

Central Business District.

4. The Present

In the period 1970-1975 racial data from the census

are not available. Public school data, the Department of

Urban Planning, and Real Estate Board reports do

provide some insights. First, the city's and DISD's ex

pansion in territory and overall population is com

pleted. The suburban ring exists. Second, population

densities have been increasing with many huge apart

ment complexes. Over 50% of all housing starts during

this period were multi-party structures. This propor

tion is much higher today. Third, and most importantly,

the Anglo school: district population in the past decade

has shifted from 63% to approximately 35%. In elemen

tary ages it is even lower. At first blush it is difficult to

comprehend how the city's population remains majori

ty Anglo while the Anglo percentage in DISD keeps

dropping. The reason is the cost of housing in the

Anglo areas of far North Dallas. In Northwest Dallas

housing built from 1957-1961 sold originally for $28 to

$31,000. The average age of the head of the household

was 31 with 3 children, elementary age. Today these

9

same homes sell for $70 to $180,000 with average age

of the head of the household being 52, 3 children, 1 high

school age, and the other 2 already gone.

The demographic picture of Dallas makes clear the

enormity of the task facing a district judge. Unlike

many cities where whites ring a black core and pie

shaped wedges will accomplish considerable racial mix

ing,5 Dallas has great physical separation of Blacks

from most Anglos by, first, the Trinity River, second,

the Central Business District, and finally by a Mexican

American arc. From far South Dallas (e.g., South Oak

Cliff or Zumwalt schools) to far North Dallas (W. T.

White or Dealey schools) is approximately a 50 minute

drive by car on Sunday. Yet the Black population is

largely in South Dallas and the Anglos are in the far

north.6 The problem is exacerbated by the low densi

ties of Anglo children (except for the naturally

integrated Pleasant Grove) and the band of Mexican

American settlements between the Anglos and the

Blacks.

C. The District Court's Plan

How, then, to desegregate? Between plaintiffs,

defendants, interveners, amicus, and even students

there were numerous theories and several carefully

prepared plans. When the month of hearings ended in

March 1976, judge Taylor had before him six major

5 E.g., Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

6 Housing costs, occupational demands, and convenience make

it clear Anglos will continue to occupy the far north of the city. It is

less clear how long they will remain in the southwest and

southeast.

10

plans for achieving a unitary school system. As would

be expected deep divisions existed among them on the

amount of busing to be ordered.7 Beyond that,

however, there were a surprising number of common

points in most of the plans: The huge district should be

divided into more manageable subdistricts,8 each of

which should reflect the ethnic mix of the district as a

whole; naturally integrated areas (not more than 75%

Anglo or 75% Black and Mexican American combined)

should be preserved;9 magnet schools, such as the

nationally renowned Skyline in Pleasant Grove, should

be created to accomplish desegregation in the high

school grades;10 East Oak Cliff, because of geography

and the location of naturally integrated areas, might re

main unchanged.11 Additionally, there were middle

points about which some of the parties appeared to care

more than others. These included accountability

mechanisms and the use of desegregation tools beyond

transportation.

7 The highest was Plaintiffs' Plan A at 69,000; the lowest was

D1SD at 14,000.

8 On this point there was less agreemen t since the polarity of the

NAACP and DISD Plans led each to reject subdividing. Subdivid

ing was present and heavily stressed in both plans of Plaintiffs and

the Dallas Alliance Plan.

9 Judge Taylor noted “as all parties recognized, there would be

no benefit educational or otherwise in disturbing this trend

toward residential integration." 412 F. Supp. 1192, 1206.

10 Everyone supported the magnet concept.

11 Only the NAACP and Plaintiffs' Plan A disagreed.

11

The district court, in fashioning an order, incor

porated not only the common desegregation tools that

were tendered in each of the plans but adopted some

new and innovative tools that appear necessary for an

urban school district plan that is majority minority.

The district court's final order of April 7 ,1976, divid

ed the school district into six subdistricts. This con

figuration was to preserve the naturally integrated

areas; heighten parental involvement; achieve max

imum desegregation within each subdistrict; facilitate

administration and student assignment.

As a means of facilitating student assignment for

desegregation purposes as well as to insure maximum

utilization of existing facilities, the judge standardized

the grades throughout the district.12 This standardi

zation provided for the establishment of K-3 Early

Childhood Education Centers that were required to

use the Diagnostic Prescriptive concept that had

proven successful in California with respect to parental

involvement.13 Special programming was included in

the 4-6 Vanguard schools and the 7-8 Academies. The

magnet concept was employed at the 9-12 high school

level.

12 "In a good school desegregation plan: [there is] . . . (d) a uni

form grade structure [that] facilitates interchange between and

easy access to all units or schools within the system." Willie, The

Sociology of Urban Education, 60, Lexington Books of D.C., Heath

Company (1978). Contrast the proposals of Plaintiffs' Plan A and

B which respectively have 14 and 9 different grade structures for

elementary schools.

13 Thus, the order looked to using parents in the requirement to

move as rapidly as possible to a 1-10 adult-student ratio in the Ear

ly Childhood Education Centers. 412 F. Supp. at 1214.

12

The court recognized its charge as being one of pro

viding an equal educational opportunity to all students

within the district by desegregating the district to the

maximum extent practicable. One of the desegregation

tools employed was student assignment. Once the

judge had carved out the naturally integrated areas and

divided the district into subdistricts that reflected the

approximate racial ratio of the entire school district, ex

cept for East Oak Cliff and Seagoville,14 there were few

options remaining. To facilitate the necessary parental

involvement, students that were in the K-3 grades

were assigned to schools within two miles of their

home if possible. Students in grades 4-8 were assigned

to centers in areas of centrality within their subdistrict

which generally reflected an ethnic balance (except for

East Oak Cliff). To provide maximum desegregation in

all new special programs such as the 4-6 Vanguard, the

7-8 Academies and the 9-12 magnets, the court re

quired that the enrollment in each of these special

schools reflect the racial makeup of the grade level.

The judge in this case, recognizing the instability and

ineffectiveness of the sole employment of a student

assignment tool, elected to go further in his remedial

order. He adopted a variety of desegregation techni

ques. Some, of course, are reasonably familiar. E.g.,

The Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

14 Seagoville, an area of blue collar Anglos, was made a separate

subdistrict because of its geographical isolation from the rest of

DISD. It lies in the far southeast, and although Seagoville is 81.5%

Anglo, it contains less than 2% of DISD's student population. The

nearest pocket of Blacks is 15 miles distant.

419 F, 2d 1211 (CA 5 1970) order on personnel.15

Others, however, have not heretofore been estab

lished as universal remedies. It was here, drawing on

the compromise efforts of the Education Task Force of

the Dallas Alliance, that the plan best reflected the

nature of the community. Because of the Mexican

American children, bilingual and multi-cultural educa

tion were needed as well as minority to majority trans

fers for Mexican Americans.16 Special programs for all,

including career education, curriculum transfers for

the physically handicapped, mentally retarded and

highly gifted were included. To ensure an ethnic mix at

the very top of the system a recruiting and employment

requirement to employ Blacks and Mexican Americans

in administrative posts according to their percent of the

population was ordered. In addition both an internal

and external accountability systems were ordered.

15 The other familiar techniques included: majority to minority

transfer; authorization to the district to modify attendance zones

to further promote desegregation; establishment of new facilities

in areas that will promote and enhance desegregation; the es

tablishment of a tri-ethnic committee to report to the court on a

continual basis; a discipline and due process policy; and retention

of jurisdiction.

The Fifth Circuit held that Judge Taylor erred in failing to re

quire D1SD to assume the burden of providing transportation to

those students electing to choose majority to minority transfer.

The inclusion of such a provision in an order is not a matter of dis

cretion, Swann v. Charlolte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1,

26-27 (1971), and the Fifth Circuit was hyper-technical in its read

ing of Part X of the order. The Dallas Alliance's Plan intended D1SD

to assume the burden; part X (3) of the order requires D1SD to

assume the burden; and in fact DISD is assuming the burden and

has done so from the time of the order.

16 "Mexican Americans who comprise less than five percent

of the school to which they are originally assigned, may transfer to

a school that offers the Bilingual Education Program." 412 F.

Supp. at 1218.

13

14

The totality of the tools selected anticipated Milliken

v. Bradley 11, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) and evidenced the far

sighted approach taken by the district court. Further

more, they suggest that it is questionable as to whether

any tri-ethnic school district can fully realize its

desegregative goal by student assignment alone.

Creativity is a necessary aspect.17

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. What occurred in the district court is precisely

what ought to occur. A district judge appraised himself

of all the available facts, considered and combined the

options, recognized the necessity of some compromise

among positions, selected the options best suited to

providing an equal and quality desegregated

educational opportunity to each child in the system,

and adopted a plan that promises to work both im

mediately and in the future. The promise of success is a

17 A very similar conclusion was reached by Plaintiffs' expert

witness, Dr. Charles V. Willie of Harvard. Dr. Willie was one of

the masters appointed by Judge Garrity in Morgan v. Hennigan, 379

F. Supp. 410 (D. Mass. 1974), aff'd sub nom. Morgan v. Kerrigan, 509

F. 2d 580 (CA 1 1974) cert, denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975), the Boston

case. He concludes an article about the largely rejected plan he

drafted by noting that it proposed "a new approach to school de

segregation which attempted to unite method and purpose. Some

of our proposals were rejected in favor of advancing racial quotas,

method without its purposes. . . How to prevent separation of

method from purpose in education is a problem in need of serious

study. An editorial in the New York Times summed up the issue

quite nicely: Integration must be made synonymous with better

education (May 20, 1975). Willie, Racial Balance or Quality Education?

84 School Rev. 313, 325 (1976).

15

key component. Success comes from quality and is

sustained by support. Judge Taylor knew of Boston and

Louisville. He knew that a court order without support

in the community is an exercise of will, not of dis

cretion. He charged the community to come forward

and make the plan work. The community responded ac

cordingly. To hold, as the Court of Appeals did, that

more had to be done, crossed the limits of appellate

review of district court discretion.18 Dayton Board of

Education v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406, 409 (1977).

2. Since this can and should be decided on the

narrow issue of the informed discretion of the district

judge, no other issues need be reached. But should the

issue tendered by the Curry Intervenors be faced, their

position should be rejected. Transmuting school suits

into battles that tax social science methodologies

beyond their limits holds promise for neither schools

nor courts — nor this Nation.

% ARGUMENT

I. The District Judge Appropriately Exer

cised The Broad Discretion Necessary To Im

plement A Successful Desegregation Plan.

18 In spite of Fifth Circuit's ruling, it acknowledged the com

prehensive approach by the district judge: "After developing a

voluminous record and holding hearings for over a month on the

feasibility and effectiveness of these proposals, the district judge

drew a comprehensive plan dealing, inter alia, with special

programs, transportation, discipline, facilities, personnel, and an

accountability system, as well as student assignments." 572 F, 2d

1010, 1013 (CA 5 1978).

The Civil Rights Commission in its 1976 report Ful

filling the Letter and Spirit of the Law spent considerable

detail to remind us of the received knowledge after two

decades of school desegregation: successful desegrega

tion happens not by chance but through planning and

total community commitment. Id. at 168-201. "Only in

learning together as equals, sharing knowledge and ex

periences, can children hope to develop the cultural

values which will prepare them to be fully contributing

members of society." Id. at 206. The report reflects well

the breadth of school desegregation in attempting to

provide the promise of Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 494 (1954): equal educational opportunities for

all.19

The path to the promise is not perfectly marked and

cryptic statements in Brown II, Swann and Green tell the

19 We do not read Brown 1 as purely a race case. First, it is not so

written; indeed it is written as an education case. Second, if it were

solely a race case, the remedy would have been significantly easier

to achieve and none of the language of Brown 11 and Swann would

have been necessary. Third, as a race case it places incredible

strains on credulity to assume that Southern schools, but for

segregation would have been integrated, while the Northern

schools would not. Milliken v. Bradley 1, 418 U.S. 717(1974). Finally,

while treating Brown as a race case has the advantage of simplicity

of remedy — bus to balance — it carries the corresponding difficul

ty of ignoring the mission of any school system: to provide a quali

ty education to each child. If the mission is recognized, the

availability of a richness of remedial actions in a school desegrega

tion context becomes apparent. Milliken v. Bradley 11, 433 U.S. 267

(1977). See generally, Bell, Serving Two Masters: Integration Ideals and

Client Interests in School Desegregation Litigation, 85 Yale L.J. 470 (1976).

See also Willie, Racial Balance or Quality Education?, 84 School Rev. 313

(1976): "The fact that this desegregation decision was intended to

foster education seems to have been forgotten."

17

district judge upon default by a school board a broad

discretion is his. To exercise his discretion he must first

learn, then act, and finally evaluate (somewhat later)

the success of his product. Few other discretionary

decisions probe so deeply into the resources of a judge

or approach even a fraction of the difficulty. And, as we

have noted, the geography and population shifts in

Dallas made Judge Taylor's job unenviable in its com

plexity.

Although a native Dallasite, the judge had to study

the district to learn, inter alia, where the people lived,

where they would live in five years, what the ages of

their children were, where the schools were located, as

well as the conditions, complections and capacities of

the schools. Then a solid month of trial provided Judge

Taylor with a wealth of plans and information.

Naturally, none of the plans submitted was perfect. But

some were remarkably better than others. The judge

had already recognized, as he had stated in court, that

the DISD plan was "patently unconstitutional." The

responsibility for securing a constitutionally acceptable

plan was now squarely his. When school authorities

default "a district court has broad power to fashion a

remedy that will assure a unitary school system."

Swann, 402 U.S. at 16.

Of the remaining plans, one other was especially

troublesome. The quota-like approach of the NAACP

with its demand to change student assignments as

neighborhoods change not only ran against Swann's

18

presaging of the holding in Pasadena City Board of Education

v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424 (1976), but the NAACP in its

commitment to provide a racially balanced system for

Blacks was willing to leave the Mexican American

children in a secondary position (at least temporarily).20

Such a conclusion is also ''patently unconstitutional"

and it is unthinkable that a district judge would accept

it. Of necessity the focus on the plan to be ordered

narrowed to those plans which were constitutional and

which promised to work. The plan finally implemented

reflected the predominant thinking of the parties to the

litigation. Where commonalities of approach were pre

sent, they were implemented.21 The process was the

essence of informed discretion: the application of

reasoned judgment to the facts at hand.

It is true that the plan selected, essentially the plan

drafted and submitted by the Education Task Force of

the Dallas Alliance, is a compromise. It is easy to deride

compromise. Furthermore, sloganeering that con

stitutional rights cannot be compromised is as

irresistable as it is irrefutable. Unfortunately, it begs

the real question. The answer, of course, is that each

20 "The first magnitude of desegregation and the attaining of an

Unitary School System should be to achieve a racial balance of

black and white students in each school and then follow through

with the integration of other minorities into the system."

(Emphasis added).

21 The commonalities available demonstrate a substantial im

provement over the situation at the beginning of this decade

where the lack of alternatives from either counsel for the plain

tiffs and the school boards virtually mandated racial balance

remedies "because there is not much else that a court can do that

will have an impact." Bickel, Education in a Democracy: The Legal and

Practical Problems of School Busing, 3 Human Rights 53, 59-60 (1973).

19

child must be granted equal educational opportunities

and there is a duty on the school board (or, that failing,

the district judge) to establish a unitary school system.

But these in turn are only starting points. Despite a

decade of urban litigation involving cities as diverse as

Charlotte, Mobile, Denver, Detroit, Pasadena, and

Dayton, major questions — questions that no district

judge can avoid — are unanswered (and sometimes un

asked). Swann assumed that some one-race schools

were allowable. But how many? For what size school

district? What parameters ought a judge employ in

evaluating the one-race school question in a majority

minority district? Is there a maximum beyond which a

district may not go regardless of the strength of the

proffered justification? If neighborhood schools are

acceptable for the very young, what grades are encom

passed? At what point does the amount of time a stu

dent spends on a bus each day become unreasonable?

As a district judge fashions his remedy to include not

only student assignments, but also quality educational

programs and faculty hiring policies that assist

desegregation, what are the priorities among them?22

Is there any room for community involvement beyond

that which the adverse parties bring to the litigation?

22 Consider Dr. Kenneth Clark's analysis:

Given the fact that public schools, so far, reflect the racial

populations of the cities, the goal of attaining high quality

education through the democratic process of realistic and

administratively feasible forms of desegregation appears

to be, at least temporarily, abandoned and is being re

placed by the need to concentrate on raising the quality of

education without regard to the present racial composi

tion of a city's public schools. This educational imperative must

be met, for the present generation of students in the public

20

Parties, obviously, have pat answers to these and

other questions. That is the nature of litigation. For

judges, however, the best that is possible is an educated

guess as to what the ultimate answers to these

questions will be, assuming that in fact answers will be

forthcoming. What a district judge faces, then, is an ex

plicit directive — establish a unitary school system —

large parameters of which are vague.23 It is hardly sur

prising that the lack of explicit rules, the vagueness of

doctrine despite numerous decisions involving urban

systems, becomes translated into the terminology of

informed discretion. For the district judge that delicate

balance of private and public needs pin-pointed by

Brown 11 must mean compromise. Not compromise in a

pejorative sense, but compromise in its best sense. For

compromise fits well with no theories and often defies

logic; its sole virtue is that in the real world it works.24

schools of our cities is not expendable. If we continue to

frustrate these students educationally, they will be, in

fact, the ingredients of the “social dynamite" which

threatens the stability of our cities, our economy, and the

democratic form of government. It is conceivable, also,

that a present emphasis on raising the quality of educa

tion for these children will eventually facilitate rather

than block the continued struggle for a non-racial

organization of the public schools in the United States.

K. Clark, A Possible Reality: A Design for the Attainment of High Academic

Achievement for Inner City Students 51 (1972) (Emphasis added).

23 See generally, Yudof, School Desegregation: Legal Realism, Reasoned

Elaboration, and Social Science Research in the Supreme Court, 42 Law and

Contemp. Probs.______(Spring 1978) (forthcoming).

24 “Legal theory is one thing. But the practicalities are

different." Ashbacker Radio Co. v. F.C.C., 326 U.S. 327, 332(1945).

21

While the plan adopted is largely the consensus plan

of the Dallas Alliance and thus to that extent reflects

compromise among private citizens, Amicus believes

that it is unreasonable to expect district judges to be

limited to the entire plan of one of the participants.25 A

judge must pick and choose among features of the

various plans before the court, trying to get the best

mix of concepts and programs. It is his duty — not that

of any of the parties (except the school board) — to

fashion a plan that promises to work. In the exercise of

this duty a district judge will encourage, as he will in all

litigation, compromises among the parties. Indeed the

very vagueness of the law and flux of urban America

invite compromise. It is not a dirty word; it is a legal and

practical necessity. And it is what judge Taylor did. He

took common parts from all of the plans. He reached

for consensus. He gave more to one side in some places,

less in others. Desegregation plans are not made in

heaven. They are drafted by individuals with sharply

competing (and sometimes divided) interests. Putting

together a compromise whole is not an abuse of discre

tion.

Choosing the amount of busing to achieve a

desegregated system has always been the most difficult

task for the lower courts. Their familiarities with the

25 See also, Main, Sealing off the City: School Desegregation in Detroit, in

H. Kalodner & J. Fishman eds., The Limits of Justice 223, 274

(1978): "The NAACP and the board of education submitted dras

tically different plans. Both parties seemed to take extreme posi

tions on the assumption the court would strike a compromise

between them."

"practicalities of the situation," Davis v. Board of School

Commissioners of Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33, 37 (1971),

whether it be knowledge of traffic patterns, natural

boundaries, or the demographics of the district, place

them in the best position to exercise informed choice. It

probably would not have been an abuse of discretion to

have ordered the busing necessary to implement Plain

tiffs' Plan A, but the concept of discretion mandates the

choice not to adopt it also.26 It is true that there were no

extensive time-distance studies entered into the record

— and those offered were conducted on Sundays. But

any knowledge of Dallas leads one quickly to the

realization that once the naturally integrated areas

were preserved there would indeed be lengthy bus

rides necessary to eliminate many of the one-race

schools, judge Taylor chose not to do this. The goal of

desegregation is not merely to rearrange the student

assignments in a system.27 It is rather to adopt a plan

that will realistically overcome the effects of past dis

crimination. It is to integrate minds as well as build

ings. Thus Judge Taylor wisely anticipated Milliken v.

26 Plaintiffs' Plan A would have transported 69,000 students

and its projected cost of implementation was $22,000,000. 412 F.

Supp. at 1200.

27 Although many people believe to the contrary. E.g., the letter

from John W. Roberts of the Massachusetts Civil Liberties Union

stating Judge Garrity's task is “to evaluate plans as they are placed

before him not on the basis of the educational quality of the plan,

but rather on the basis of whether or not they meet the standards

for school desegregation developed by the Federal Courts."

Quoted in Willie, Racial Balance or Quality Education?, 84 School Rev,

313 (1976).

23

Bradley II, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) and opted to enrich the

educational experiences of the students in a desegrega

tion context.28 This was not only present in the Early

Childhood Education concept adopted for K-3 and the

magnet approach to grades 9-12,29 but beyond this the

district judge crafted an order looking to the other

facets necessary to make a desegregation plan work.

DISD was placed under an obligation to recruit

quickly additional Black and Mexican American

teachers, principals, and other certificated personnel.

Yet simply having teachers, principals and ad

ministrators ready to occupy buildings is not enough.

Clearly the district judge recognized the disparate im-

28 Each of the Black members of the Education Task Force of the

Dallas Alliance agrees with the statement of Dr. Benjamin Mays:

"Black people must not resign themselves to the pessimistic view

that a non-integrated school cannot provide Black children with

an excellent educational setting. Instead, Black people, while

working to implement Brown, should recognize that integration

alone does not provide a quality education and that much of the

substance of quality education can be provided to Black children in

the interim." Mays, Comment: Atlanta—Living with Brown Twenty Years

Later, 3 Black L.J. 184, 191-92 (1974).

29 We admit magnet schools have not always worked —

although with an example like Skyline it is hardly surprising the

participants at the district court thought magnets an attractive

idea. The use of magnets is not simply freedom of choice by

another name. While it is true a student must choose to attend a

magnet, that choice may — and should — be heavily influenced by

the school districts. Magnet schools, after all, are intended to be

significantly superior to other high schools and this can be assist

ed by a district's phasing out competing courses at non-magnet

schools. Should the magnet concept be found ineffective the

retention of jurisdiction by the district judge allows for correction.

E.g., high school attendance zones might be modified to achieve

additional racial mixing.

plications of exposing innocent minority children to

possible instructional and administrative biases that

sometime fail to vanish in spite of a court order. For the

experience to be effective, they must understand and

be capable of functioning in their multi-cultural set

ting. Thus the district judge required in-depth training

of these personnel to implement the plan and improve

attitudes and awareness to facilitate the effectiveness

of the personnel in a desegregated setting.

Finally, the judge sought methodologies of account

ability. He accomplished this in two separate fashions.

First, the very top administrators in the system were to

reflect the racial composition of the city. This would

mandate increased hiring of Blacks and Mexican

Americans in the hopes that the commitment at the top

to make desegregation work now would be reflected in

commitment below. Second, the order provides not

only for an internal audit by DISD to be filed with the

Court, but, more significantly, an external audit of the

progress the system is making in adopting the plan of

the district court.

If there were nothing more than the district judge's

understanding of the district and his reasoned actions

in light of the available options and his anticipation of

the authority Milliken II would give, the plan adopted

could be sustained as an appropriate exercise of dis

cretion so long as it held the promise to work. But a

realization of what it means to adopt a desegregation

plan for a complex urban community places an even

heavier than normal burden on a district judge to assess

25

workability not only now, as Green demands, but five

years or more from now. It is inconceivable that urban

systems could be put through all the effort of creating

desegregation plans satisfactory to a federal judiciary

only to learn that if all the schools go one-race shortly

thereafter from extraneous causes, or from the very

existence of the plan that promises to work only now,

there is no further Fourteenth Amendment obligation.

No plan has value that cannot continue to work. And

for a plan to continue to work there must be communi

ty support as the Civil Rights Commission has

recognized. Fulfilling the Letter and Spirit of the Law (1976).

Judge Taylor knew this and he achieved that support.

One can search for various measures of the strength of

community support but the passage by the voters of

the $80,000,000 bond issue to assist implementation of

the court order is strong evidence that Judge Taylor's

prescient charge to the community to come forward

and be involved worked — and promises to continue to

work. The Dallas community, business, church, civic

organizations, as well as private citizens, has demon

strated support for the plan by providing resources a

court is unable to order. Within six months of the court

order 144 schools had been adopted by either business

or civic organizations as focal points for the community

effort in channeling volunteers, equipment, private

monies to the schools, as well as providing part-time

and full-time job opportunities for students.

The successful efforts to include the community and

gain a broad base of support for the plan at present and

maintain it in the future say much for the district judge.

He did not, unfortunately satisfy everyone. Maybe

such a goal is impossible. Legal responsibilities cannot,

of course, be shifted, The responsibility for a unitary

school system rests with appropriate elected officials

and, in default of their duties, with a federal judge. But

the judge cannot blind himself to what all others can

see and no one argues that school desegregation cases

where the community is in an uproar are a model for

either the political or judicial process. Schools must be

integrated. Minds must be reached. Quality and caring

must be assured. It must not only begin, it must also

continue. Maybe better plans could have been devised

but the plan adopted by Judge Taylor carried the

promise to work.30 The informed discretion of the dis

trict judge can require no more.

II. Washington V. Davis And Its Progeny

Have No Place In Southern School

Desegregation Cases.

Not only is the Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229

(1976) issue not necessary to a decision by this Court

(and not considered by the Court below), such a

holding is not in the best interests of Dallas or the Unit

ed States. School suits should not extend for the rest

of this century whether the goal is to integrate or to

avoid integration. Decisional principles should en-

30 Naturally the district judge retained jurisdiction over the

DISD litigation. Should the plans and concepts he approved be

shown not to work in practice, he is free to modify or abandon

them as experiences dictate.

27

courage reasonable compromise, not further litigation.

This applies to whether one-race schools cause

challenges as to the existence of a unitary system or are

justified as the normal outcome of urban housing

patterns having nothing at all to do with actions of

school boards.

Suddenly to reverse school desegregation cases into

endless — and fruitless — squabbling over whether

school segregation caused housing segregation or vice

versa does more than tax the limits of judicial com

petence and social science methodologies. Fundamen

tally, it encourages the false hope that school systems

may be released from the obligations to eradicate past

dejure segregation. The fruits of a quarter-century of

footdragging by school districts ought not be a return

to separate and unequal. Yet the Washington v. Davis

rationale promises little else. That is why it has been so

enthusiastically embraced by those who resisted Brown

IIr Green, and Swann. Providing for equal and quality

educational opportunities for each child in a school dis

trict — the goal of the Dallas Alliance Plan — can be

made vastly more difficult when judicial as well as

political pressures offer the hope that compromise is

unnecessary — that the future belongs to those who

questioned Brown.

The South has made great progress in the last 15

years. Indeed today Boston is clearly a Northern

phenomena, one that unfortunately may plague this

great Nation for years. The North perceives no

obligations in this area and the North resists. District

28

courts daily remind the South of its obligations. The

spur has worked to set Southern school cases against a

backdrop of high commitment to educational quality

even during a period of fiscal retrenchment elsewhere.

This is hardly a position mandating a call, no matter

how uncertain, for retreat. Leaving these cases in the

community, in the school boards, in the local district

courts, where a judge may be guided by the equitable

principles of Brown II and Swann and the desire to bring

to each child the promise of the best education, is the

appropriate solution.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above the Court should

reverse the judgment of the Court of Appeals remand

ing this case to the district court for continued imple

mentation of the ordered plan.

DATED M a y ____ , 1979.

Respectfully submitted,

H. RON WHITE

1907 Elm Street, Suite 2100

Dallas, Texas 75201

LUCAS A. POWE, JR.

2500 Red River Street

Austin, Texas 78705

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

29

PROOF OF SERVICE

I, H. Ron White, an attorney for the Amicus Curiae

herein, hereby certify that on the ------ day of May,

1 9 7 9 ,1 served three copies of the foregoing Motion for

Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae and Brief of Amicus

Curiae to the Supreme Court upon the following

Counsel for the Petitioners, Counsel for the

Respondents and the Respondent Pro Se:

Mr. Edward B. Cioutman, III

8204 Elmbrook Drive, Suite 200

P. O. Box 47972

Dallas, Texas 75247

Ms. Vilma S. Martinez

Mexican-American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

28 Geary Street

San Francisco, California 94108

Mr. Nathaniel R. Jones

1790 Broadway, 10th Floor

New York, New York 10019

Mr. Lee Holt, City Attorney

New City Hall

Dallas, Texas 75201

Mr. John Bryant

8035 East R. L. Thornton

Dallas, Texas 75228

Mr. James G. Vetter, Jr.

555 Griffin Square Building

Suite 920

Dallas, Texas 75202

Mr. James T. Maxwell (pro se)

4440 Sigma Road, Suite 112

Dallas, Texas 75240

Mr. Thomas E. Ashton, III

Dallas Legal Services

Foundation, Inc.

912 Commerce Street, Room 202

Dallas, Texas 75202

Mr. E. Brice Cunningham

2606 Forest Avenue, Suite 202

Dallas, Texas 75215

Mr. James A. Donohoe

1700 Republic National Bank

Building

Dallas, Texas 75201

Mr. Martin Frost

777 South R. L. Thornton

Freeway, Suite 120

Dallas, Texas 75203

Mr. Warren Whitham

210 Adolphus Tower

Dallas, Texas 75202

Mr. Mark Martin

1200 One Main Place

Dallas, Texas 75250

Mr. Robert H. Mow, Jr.

Mr. Robert L. Blumenthal

3000 One Main Place

Dallas, Texas 75250

30

by mailing same to such Counsel and Respondent pro

se at their respective addresses and depositing the same

in a United States mail box in an envelope properly ad

dressed to such addresses with first class postage

prepaid.

I further certify that all parties required to be served

have been served.

H. RON WHITE

Attorney for Amicus Curiae

Dallas Alliance and

Education Task Force of

Dallas Alliance

#

l a

1940 .

0 srAftf«a»*«* Of « .* « « « * * »

AMIS ya®AW SflWllOfBIM!

PUB. NO.T4SK

PLATE B- l

COMMUNITY ANALYSIS PROGRAM - CITY OF DALLAS

BLACK POPULATION BY CENSUS TRACT

2a

1-M

»•«*

80-74.®

f,m. MHUPlATS B-2

a»9««« *®®a»s*» • «i»» ®» vm im

BLACK POPULATION BY CENSUS TRACT - 1950

3a

" w w r H A C K P O P U i A T I O N

%

V v % | 2 5 - 4 9 . 9

J " * - 9 9 5 0 - 7 4 . 9

£ ^ | | g ^ Q - - . 2 4 . 9 8 0 2 » ♦

C O M M U N I T Y ANA17SIS f C O C B A M - C I T Y O f DALLAS

pLACK POPULATION BY CENSUS TRACT - 1960

7 U i . N O . T A 3 X

P L A T E B- 3

U G SW ©

Pf SCI M l B IA C « P Q S U U 7 > 0 «

a . o -

1 - 9.9

1 1 0 - 24 9

v X v 2 5 -4 9 .9

S0' 74 9

- C O M M U N IT Y A N A L Y S IS I S O C S A M * C IT Y O f D A L L A S

LACK POPULATION BY CENSUS TRACT * 1970

PUS'. N O .T 4 S X

P L A T E B -4

5a

CENSUS TRACTS IN THE DALLAS, TEX. SMSA

IN S E T A - DALLAS AND VICIN ITY

OKM

DAUAt TtK

n tvta&XD Mf r»a»ocn»i

to r 3

APPENDIX B

P O P U L A T IO N B Y RA CE B Y C E N S U S T R A C T : 1940, 1950, 196 0 A N D 1970

C E N SU S 19 4 0 1950 1960 1970

T R A C T W H ITE B LA C K W H ITE B LA C K W H ITE BLA CK W H ITE BLA CK

001 2,587 296 4 ,445 153 3 ,549 43 3 ,772 8

002.01 3,685 60 7,093 57 3 ,462 3 3 ,120 0

002 .02 4,271 12 3 ,877 0

003 3,758 60 4 ,327 14 3 ,935 7 3,566 12

004.01 8 ,198 22 7 ,495 77 2 ,789 2 2 ,8 1 7 0

004 .02 9 ,695 35 4 ,2 4 9 6 5 ,469 121

004 .03 7,342 760 6 ,192 129

005 4 ,255 83 3 ,831 27 3,315 53 4 ,497 58

006.01 9,089 535 3,382 3 4 ,674 7 5 ,653 11

006 .02 8,344 205 7,201 124 7 ,790 49

007.01 5 ,716 694 4,911 1,363 3 ,704 5 3 ,2 9 7 8

007 .02 2 ,142 422 2 ,586 96

008 3,847 89 4,772 69 4 ,605 6 4 ,634 19

009 3,329 87 3 ,275 42 2 ,833 12 3 ,074 4

010 5,785 99 5 ,284 44 4 ,479 19 4,681 14

011.01 7,955 173 8 ,166 77 4,234 21 4 ,050 5

0 11 .02 2 ,488 12 2 ,388 1

012 5,875 118 5 ,6 6 7 59 5,126 3 4 ,6 9 7 10

013.01 7,645 383 8,515 214 3 ,423 11 1,881 1

013 .02 4 ,6 8 7 47 4 ,928 19

014 2 ,259 385 2 ,357 264 3 ,1 7 7 83 3 ,716 26

015.01 11 ,104 596 11 ,164 356 6 ,323 62 6 ,4 0 7 5

015 .02 4 ,665 78 3 ,702 42

CENSUS

TRACT WHITE

016 2 ,774

017 .01 2,281

017 .02

018 3 ,859

019 5 ,377

020 5,145

021 2 ,727

022 .01 6 ,200

022 .02

023 3 ,727

024 4 ,239

025 2,045

026 2,595

027.01 4 ,419

027 .02

028 4,701

029 2,154

030 4 ,095

031.01 2 ,106

031.02

032.01 3 ,626

032 .02

1950

W H ITE B L A C K

2,0 7 0 7,352

1,171 7,802

3,933 50

4 ,3 9 7 73

5 ,335 175

1,235 86

6 ,195 1,648

3 ,364 1,168

3 ,774 96

2 ,159 2 ,714

2 ,929 2

4 ,6 4 7 4 ,7 7 0

4 ,2 4 9 112

1,793 167

3 ,264 2 ,602

2,011 357

2 ,868 391

#

1940

BLACK

6 ,0 3 9

9 ,741

166

206

228

187

2 ,098

1,319

87

2,501

2

2 ,925

147

266

3 ,6 5 5

410

395

1960 1970

W H ITE B LA C K W H ITE B LA CK

1,114 7 ,086 425 5 ,559

548 5 ,8 2 3 42 269

322 2 ,758

2 ,720 10 2 ,578 17

2 ,305 21 1 ,390 28

5 ,0 9 3 84 6 ,0 0 5 44

545 37 153 29

1,702 620 1 ,233 418

2 ,415 340 1,856 342

2 ,106 1,373 591 1 ,939

2 ,722 86 2 ,0 6 9 341

1,790 3 ,688 460 4 ,2 4 9

2 ,156 1 1 ,665 119

32 7,245 13 7,247

105 4 ,869 23 4 ,890

965 2 ,928 75 2,445

214 1,685 89 3 ,6 8 7

1 ,688 1,185 468 151

979 411 1 ,4 5 7 981

56 40 53 1

1,269 192 342 15

133 73

1940 1950CENSUS

TRACT WHITE

033 4 ,963

034 5,151

035 2,404

036 3 ,262

037 2,121

038 3,912

039.01

0 39 .02 2 ,933

040 4 ,137

041 2 ,043

042 4,354

043 1,268

044 4,856

045 2 ,950

046 2,868

047 4 ,670

048 4 ,779

049 3 ,330

050 5 ,258

051 4 ,066

052 5 ,2 6 0

053 5 ,446

054 5 ,1 2 0

WHITE BLACK

4 ,585 451

5 ,183 442

2 ,397 186

2 ,722 286

648 6 ,8 4 0

3,734 695

2,091 5 ,553

4 ,142 68

1,861 3 ,078

5 ,3 7 7 133

1,575 40

5 ,639 87

7 ,676 12

2 ,835 36

4 ,1 9 7 41

4 ,3 3 6 36

4,311 922

4 ,834 85

4 ,515 8

4,981 22

6 ,701 3

6 ,3 6 9 1

BLACK

680

656

227

111

5,321

73

3 ,668

67

3 ,302

122

45

115

13

67

84

79

37

100

18

44

2

24

1960 1970

W H ITE B LA CK W H ITE BLA CK

2,768 519 821 977

543 5 ,559 81 6 ,852

150 2 ,372 31 3,234

73 3 ,041 8 1,825

62 6 ,8 8 0 31 5 ,8 1 7

49 5 ,559 11 4 ,8 5 8

121 4 ,548 49 4 ,525

10 4 ,642 5 3 ,742

205 4 ,418 122 3 ,662

418 4,265 135 3 ,438

4 ,8 1 7 24 4 ,4 8 9 22

2,962 1 ,877 2 ,4 3 7 1 ,280

5 ,6 9 0 25 6 ,3 8 6 9

6 ,719 5 7 ,172 3

2 ,654 14 2 ,7 5 3 10

3 ,074 8 2 ,973 4

3 ,369 196 3 ,4 3 3 193

4 ,640 1 ,500 5 1 8 7 ,006

3 ,984 52 2 ,871 56

4 ,025 4 3 ,584 0

4 ,293 10 3 ,771 2

5 ,946 0 5 ,344 1

5 ,9 6 2 5 4 ,2 8 7 2 ,620

#

C E N SU S 194 0 1950

T R A C T W H ITE B L A C K W H ITE

055 3 ,070 3 4 ,070

056 4,586 2 5 ,580

057 4 ,306 1 6 ,101

058 6 1 ,495 57

059.01 4 ,3 0 0

0 59 .02

060.01 1 ,396

060 .02

061 149

062 2 ,5 6 7

063.01 4 ,628

063 .02

064 4 ,3 9 8

065 4 ,519

066 89

067 2 ,651

068 3,582

069 5 ,817

070 2 ,738

071 .01 7 ,285

071 .02

072 3 ,649

073.01 6 ,755

1960 1970

WHITE B LA C K WHITE B LA C K

4,284 34 562 3 ,443

4 ,970 1 3 ,497 1 ,539

6 ,3 6 6 0 1 ,813 5 ,524

7 ,008 1 930 7,304

3 ,3 7 8 3 601 3 ,717

4 ,643 0 3 ,925 648

2 ,506 0

1,185 0 4 ,751 7

4 ,298 4 4 ,532 25

5 ,2 1 0 0 4 ,5 2 7 0

2 ,463 1 2,211 1

5 ,762 0 5 ,892 2

6 ,253 0 6 ,2 5 7 0

2 ,509 0 3 ,123 3

2 ,343 1 4 ,384 59

590 2 1,913 4

2,613 29 2 ,1 7 8 138

4 ,432 2,371 1 ,763 5,861

3,703 3 4 ,635 6

2 ,859 16 2 ,452 2

BLACK

0

0

3

3 ,539

1

1

0

1

1

7

0

0

4

0

4

0

60

13

110

CENSUS 1940 1950

T R A C T

073 .02

W H ITE B LA C K W H ITE B LA C K

074 716 56

075.01

075 .02

990 132

076.01

076 .02

076 .03

076 .04

2,534 72

077 2 ,679 60

078.01

078 .02

078 .03

1 ,518 23

079.01

079 .02

1 ,738 6

080 2 ,940 69

081 4 ,298 23

082 2 ,270 8

083 1 ,286 2

084 6,241 0

085 2,541 1

086 2 ,3 1 8 3

087.01

087 .02

5 ,9 7 9 18

1960 1970

W H ITE B LA C K W H ITE BLA CK

4,001 46 4 ,0 0 9 18

1,660 49 1,676 12

1,224 89 720 14

461 6

1 ,728 20 2,285 3

1 ,286 45 803 9

4 ,084 13 838 3

3 ,670 4

5 ,743 39 5 ,733 33

4 ,2 3 0 3 ,019 893 1

3 ,448 3,171

6 ,970 81

2 ,1 8 9 3 7,712 16

5 ,629 1 5,851 5

5 ,456 23 5 ,885 5

5 ,9 2 6 18 6 ,9 1 7 8

3 ,3 4 3 1 5 ,0 2 9 0

2 ,037 6 1 ,623 2

6 ,8 6 3 6 6 ,2 2 5 4

3 ,5 3 8 1 3 ,274 0

4 ,318 3 925 3 ,155

1,916 5 362 4 ,606

9,491 1 1 ,099 12,334

10a

C E N SU S 1940 1950 1960 1970

T R A C T W H ITE B LA C K W H ITE B L A C K W H ITE B L A C K W H ITE B LA C K

088 4,691 1 9 ,138 15 407 11 ,829

089 2 ,7 6 9 1,004 1,590 18 676 7,272

090.01 2 ,2 4 8 36 999 1 1 ,177 7

090 .02 2 ,540 0 4,221 1

091 .01 4 4 7 34 6 ,322 0 5 ,378 0

091 .02 8 ,274 0 8 ,782 1

092 .01 4 ,172 12 4,601 1 5 ,4 0 6 2

092 .02 4 ,535 0 4 ,7 1 0 0

093.01 5 ,112 33 3,891 2 3 ,648 2

093 .02 4 ,2 4 7 0 7 ,310 57

094 525 2 7 ,966 2 6 ,969 6

095 2 ,412 9 2 ,485 0

096.01 6 ,954 64 12 ,011 90

096 .02 8 ,6 5 7 3

096 .03 4 ,7 4 6 0

096 .04 2 ,059 137

097 5 ,766 2 8 ,6 6 9 7

098 4 ,7 8 8 3 9 ,1 5 7 8

099 4 ,621 0 3 ,185 2

100 1 ,170 3 ,289 861 2 ,764

101 4 ,200 7,702 3 ,5 6 7 7 ,569

102 315 7 ,417 329 6,171

103 5,062 2 299 4 ,448

11a

C E N SU S 194 0

T R A C T W H ITE B LA C K

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111.01

111.02

112

113

114.01

114.02

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122.01

122 .02

123

1950

W H ITE B L A C K

196 0 1970

W H ITE

UU

B LA C K W H ITE B LA CK

2,1 6 7 351 902 1,568

1 ,527 3 ,329 1,119 2 ,720

5 ,695 172 5 ,4 9 7 282

3,664 0 6 ,3 9 0 24

4 ,8 9 2 1 14,901 12

386 8 1 ,312 6

3 ,907 0 10 ,138 1

7 ,047 13 1,914 7

11 ,584 19

2 ,688 2 846 2 ,696

1,376 1 174 4 ,643

402 0 133 4 ,369

134 1,605

168 6 ,3 0 2 42 6 ,7 2 9

5 ,113 0 7 ,484 19

4 ,192 3 5 ,841 4

2 ,174 0 2 ,686 0

1 ,110 0 2,454 0

1 ,281 0 2 ,526 0

275 0 2 2 7 15

3 ,490 4 12 ,168 2

4 ,066 175

4 ,916 2 6 ,9 9 4 9

12a

C E N SU S 194 0 19 5 0

T R A C T W H ITE B L A C K W H ITE B L A C K

124

125

126

127

128

129

130.01

130.02

131

132

133

134.01

134 .02

135

136.01

136 .02

136 .03

137 .03

138.01

140.01

140.02

141.0 I

141.02

1960 1970

W H ITE B LA CK W H ITE B LA CK

6,381 11 6 ,820 4

9,515 1 8 ,8 3 0 0

2 ,228 0 4 ,0 1 0 0

8,811 0 8 ,325 2

6 ,534 3 9 ,183 7

5,371 1 5 ,293 0

7 ,657 100 13 ,746 70

9 ,6 8 0 15

2 ,646 6 7,725 9

1,614 255 2 ,1 2 8 80

2,341 9 2 ,049 2

1 ,767 5 1,146 8

1,504 0

967 8 2 ,885 8

1 ,770 312 1,112 247

7 ,600 2

11 ,191 20

0 0

0 0

66 0 0 0

47 0

0 0

37 0

13a

1950C E N S U S 1940

TRACT WHITE BLACK WHITE

148

158

159

163

164

165.01

165 .02

165.03

165.04

166.01

167.01

167.02

169.01

169 .02

171

176.01

178.01

178.02

179

180

181.03

184

BLACK

1960 1970

WHITE BLACK WHITE B LA CK

0 0

0 0 0 0

37 0 42 0

0 0 23 0

0 0 0 0

562 0 1 ,627 21

0 0

86 1

0 0

1 ,477 10 1 ,638 0

2 ,068 24 146 3 ,085

341 395

547 90 155 2,851

113 6

164 0

135 0 156 0

0 0

0 0

209 0 205 0

166 0 101 0

0 0

0 0 0 0

14a

CENSUS

T R A C T

185.01

185 .02

190.01

190 .02

190 .03

192.01

194 0 1950 1960 1970

W H ITE B L A C K W H ITE B L A C K W H ITE B L A C K W H ITE B LA C K

68 48 19 0

66 2

112 14 0 8

0 0

453 2

169 0 4 ,6 9 7 5

Source: 1940, 195 0, 1960and 1970 Census o f Population, U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census.

15a

APPENDIX C

THE DALLAS ALLIANCE

CORRESPONDENT ORGANIZATIONS

American G.I. Forum

American Indian Center of Dallas, Inc,

American Institute of Architects, Dallas Chapter

American Jewish Committee, Dallas Chapter

Amigos

Bishop College

BTJai B'Rith Womens' Council

Boy's Club of Dallas, Inc.

Brown Berets

Camp Fire Council of Metropolitan Dallas

Catholic Charities

Catholic Diocese of Dallas

Church Women United

Community Council of Greater Dallas

Community Relations Council, Jewish Federation of

Greater Dallas

Council of Catholic Women, Dallas Deanery

Cumberland Presbyterian Church

Dallas Alumnae Chapter, Delta Sigma Theta

Dallas Association for Retarded Citizens

Dallas Association of Young Lawyers

Dallas Bar Association

Dallas Black Chamber of Commerce

Dallas Chamber of Commerce

Dallas Citizens Council

Dallas City Council of PTAs

17a

Dallas Civic Ballet

Dallas Council on Alcoholism

Dallas County Adult Probation Department

Dallas County AFL-CIO

Dallas County Community Action Committee

Dallas County Mental Health & Mental Retardation

Center

Dallas County Nutrition Program

Dallas Federation of Women's Clubs

Dallas Homeowners League

Dallas Housing Authority

Dallas Housing Forum

Dallas Inter-Tribal Center

Dallas Junior Chamber of Commerce

Dallas Mexican Chamber of Commerce

Dallas Opportunities Industrialization Center

Dallas Police Department

Dallas Minority Business Center

Dallas Public Library

Dallas Symphony Association, Inc.

Dallas Urban League

East Dallas Community Design Center

Family Guidance Center

Goals for Dallas

Goodwill Industries of Dallas, Inc.

Greater Dallas Community of Churches

Greater Dallas Community Relations Commission

Greater Dallas Crime Commission

Greater Dallas Housing Opportunity Center, Inc.

Greater Dallas Planning Council

Historic Preservation League of Dallas, Inc.

Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance

Jobs for Progress, Inc, (Operation SER)

Junior League of Dallas, Inc.

League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC)

League of Women Voters of Dallas

Links, Inc., of Dallas

Los Barrios Unidas Clinic

Mental Health Association of Dallas County

Mount Olive Volunteer Effort (MOVE)

National Alliance of Businessmen

National Association of Social Workers, Inc.

National Conference of Christians & Jews

National Council of Jewish Women, Greater Dallas

Section

National Organization for Women (NOW)

NAACP — John F. Kennedy Branch

NAACP — Oak Cliff/Cedar Crest Branch

NAACP — South Dallas Branch

Neighborhood Conservation Alliance

Neighborhood Housing Services of Dallas, Inc.

North Park/Love Field Civic League

Rabbinical Association of Dallas

Salesmanship Club of Dallas

Salvation Army

Senior Citizens of Greater Dallas, Inc.

Southern Methodist University

Tejas Girl Scout Council, Inc.

Theater Three

United Methodist Church, Office of the Bishop

18a

19a

Urban Studies Program, SMU

Venture Advisors, Inc.

Visiting Nurses Association

Voluntary Action Center of Dallas County

Wesley Rankin Community Center

Womens' Council of Dallas County, Inc.

Women for Change Center

YMCA of Dallas Metropolitan Area

YWCA of Metropolitan Dallas