Regan v. Wright Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

November 30, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Regan v. Wright Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1981. 6a13efe8-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9da59869-29c1-4367-92d5-d66b6dad1488/regan-v-wright-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

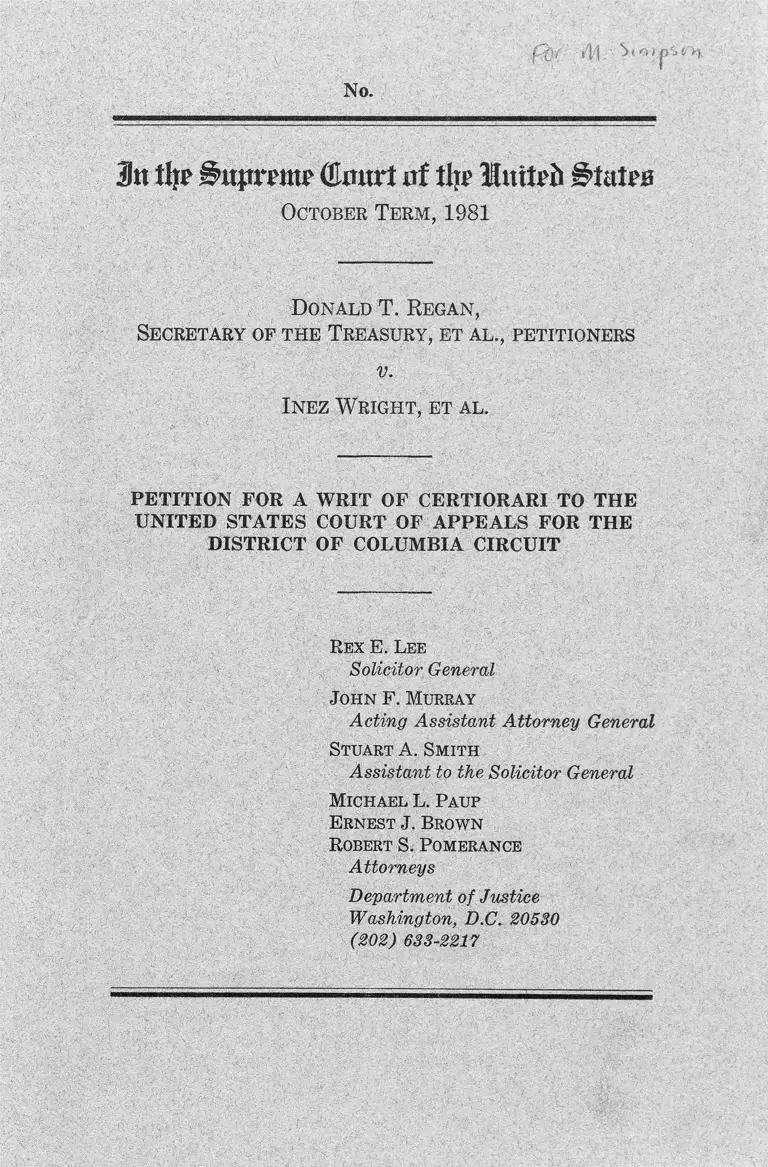

No.

In % (tart of tlyp Huttrfc States

O ctober T e r m , 1981

D o n a ld T . R e g a n ,

Se c r e ta r y of t h e T r e a su r y , e t a l ., p e t it io n e r s

v.

I n e z W r ig h t , e t a l .

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

Rex E. Lee

Solicitor General

John F. Murray

Acting Assistant Attorney General

Stuart A. Smith

Assistant to the Solicitor General

Michael L. Paup

Ernest J. Brown

Robert S. Pomerance

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 633-2217

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether federal courts may entertain equity suits

against the Secretary of the Treasury brought by

persons seeking to have the Treasury revise the

rules under which it determines the eligibility of

private schools for tax-exempt status, and to deny or

revoke tax-exempt status of private schools claimed

to have insufficient minority enrollment, where the

plaintiffs allege no actual injury to themselves either

by any private school or by the Treasury.

(i)

( i l

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Opinions be low ...................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction.... ................. -......-..................................... ........ 2

Constitutional provisions, statutes and regulations

involved - ..... .................. - ......... -......-................................ 2

Statement:

A. Background ........—......-......-.........-.......................... 2

B. The proceedings in this case-------------------- ------ 5

Reasons for granting the petition.---------------—............... H

Conclusion ---------------------- ------ -......................................... 24

Appendix..... -.....-..................... —................... -.............. -...... ^a

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

American Jewish Congress V. Vance, 575 F.2d 939- 10

American Society of Travel Agents V. Blumenthal,

566 F.2d 145, cert, denied, 435 U.S. 947 .... . 10

Angelus Milling Co. V. Commissioner, 325 U.S, 293.. 20

Baker V. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 -------------------------------- 16

Boh Jones University V. Simon, 416 U.S. 725------ 17, 20

Bob Jones University V. United States, 639 F.2d

147, cert, granted, No. 81-3 (Oct. 13, 1981)------ 4, 23

Coit V. Green, 404 U.S. 997, aff’g Green V. Con

nolly, 330 F. Supp. 1150......................--------------- 10

Enochs V. Williams Packing Co., 370 U.S. 1 --------- 20

Flast V. Cohen, 392 U.S. 8 3 ...... ................. ................ 16

Flora V. United States, 362 U.S. 145 -------------------- 20

Gilmore V. City of Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556---- 10,17,18

Goldsboro Christian Schools, Inc. V. United States,

cert, granted, No. 81-1 (Oct. 13, 1981) ------------- 4

Green v. Kennedy, 309 F. Supp. 1127, continued,

330 F. Supp. 1150, aff’d, 404 U.S, 997 ...... ........— 16

Laird V. Tatum, 408 U.S. 1 --------- ------- ------- -------- 19

Louisiana V. McAdoo, 234 U.S. 627 --------------------- 20

(HI)

Cases— Continued

IV

Page

Moose Lodge No. 107 V. Irvis, 407 U.S. 163---------- 15

Norwood V. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 .........— ......... - 10,17

O’Shea V. Littleton, 414 U.S. 488 ------------------- ---- 15

Prince Edward School Foundation V. Commis

sioner, 478 F. Supp. 107, aff’d by unpublished

order, No. 79-1622 (D.C. Cir. June 30, 1980),

cert, denied, No. 80-484 (Feb. 23, 1981) --------- 4

Schlesinger V. Reservists to Stop the War, 418 U.S.

208 .................................................... -........- .......... - 16,19

Sierra Club V. Morton, 405 U.S. 727 -------------------- 15

Simon V. Eastern Ky. Welfare Rights Organiza

tion, 426 U.S. 26 ............ ........... -8, 9,11,12,13, 14,16, 20

Tax Analysts & Advocates V. Blumenthal, 566 F.2d

130, cert, denied, 434 U.S, 1086 —........ - ......-....... 10

United States V. Felt & Tarrant Co., 283 U.S.

269 ................................................................-............. 20

United States V. Richardson, 418 U.S. 166---- 15,19, 21, 23

Warth V. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490 _____________ 13,15,16,18

Constitution and statutes:

United States Constitution:

Article II, Section 3 ------------------------------------- 19

Article III ------------ ----------------- -------------2,11,15, la

Fifth Amendment____ ____ —------------------------ 2

Fourteenth Amendment ------- -------------- ----- 2

Anti-Injunction Act, 26 U.S.C. 7421(a) ........ — 20

H.R. J. Res. 644, of Dec. 16, 1980, Pub. L. No. 96-

536, 94 Stat. 3166, Section 101(a) (1) and (4 ),

as amended by Supplemental Appropriations and

Rescission Act, 1981, Pub. L. No. 97-12, Section

401, 95 Stat. 95 - ----- ------------ -------------------------- 22

H.R. J. Res, 325, Pub. L. No. 97-51, 95 Stat. 958.... 23

Internal Revenue Code o f 1954 (26 U .S.C.):

Section 170(a)

Section 170 (c)(2 )

Section 501(a) ....

Section 501(c) (3)

Section 6212 ------

Section 6213 ------

Section 6532 .........

............... . 2, la

_______ 2, 3,12, 2a

.................. 2

2, 3, 4, 9,12,17,19

__________ 20

__________ 20

..................... 19

V

Constitution and statutes— Continued Page

Section 7422 ...... 19

Section 7801 (a) ________________ ___________ 19

Section 7805(a) .............................. ......... ........ . 19

Sections 8021-8023 ______________________ 19

28 U.S.C. 1346 ________________ ____ ________ _ 19

28 U.S.C. 1491...................... 19

28 U.S.C. 2201 _________________________ 20

Treasury, Postal Service, and General Government

Appropriations Act of 1980, Pub. L. No. 96-

74, 93 Stat. 559 ........................................... .............. 5

Section 103, 93 Stat. 562 _______________ 2 ,5 ,9 ,22

Section 615, 93 Stat. 577 _______ ___ ___ 2, 5, 9, 22

Rev. Stat. 1977 (1878 ed.) (42 U.S.C. 1981) _____ 2

Miscellaneous:

4 Administration, Internal Revenue Manual

(CCH ), im 341.11-341.13 ______ ___ ________ ____ _ 3

127 Cong. Rec. H5392 (daily ed. July 30, 1981).... 22-23

127 Cong. Rec. H6698-H6699, H6702 (daily ed.

Sept. 30, 1981) _______ _______ _____________ _ 23

H.R. 4121, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. § 616 (1981) ____ 22

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1656, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1976) ........................ ............ ............. ..................... 20

H.R. Rep. No. 96-248, 9th Cong., 1st Sess. (1979).. 22

Rev. Proc. 75-50, 1975-2 Cum. Bull. 587 __________2, 3, 23

§2.02 ............................................................. ........ 3

Rev. Rul. 71-447, 1971-2 Cum. Bull. 230 __________ 4

Rev. Rul. 75-231, 1975-1 Cum. Bull. 158 ________ 4

S. Rep. No. 94-996, 94th Cong., 2d Sess, (1976)___ 20

Tax-Exempt Status of Private Schools: Hearings

Before the Subcomm. on Oversight of the House

Comm, on Ways and Means, 96th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1979) 21

3n % ̂ KpYmv (Emtrt 0! th? Imteft 01at̂

October T e r m , 1981

No.

D o n a ld T . R e g a n ,

Se c r e ta r y of t h e T r e a su r y , et a l ., pe t it io n e r s

v.

I n e z W r ig h t , e t a l .

PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

The Solicitor General, on behalf of the Secretary

of the Treasury, and the Commissioner of Internal

Revenue, petitions for a writ of certiorari to re

view the judgment of the United States Court of

Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in this

case.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the district court (Interv. Pet. App.

A la -lS a )1 is reported at 480 F. Supp. 790. The

opinion of the court of appeals (Interv. Pet. App.

B lb-58b) is reported at 656 F.2d 820.

1 “ Interv. Pet” refers to the petition for a writ of certiorari

(No. 81-757) filed by the intervener W. Wayne Allen, Chair

man of the Board of Trustees of the Briarcrest School Sys

tem in Memphis, Tennessee.

(1)

2

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals was entered

on June 18, 1981. The orders of the court of ap

peals denying the petition for rehearing (Interv.

Pet. App. C) with suggestion for rehearing en

banc (Interv. Pet. App. D) were entered on Au

gust 26, 1981. A petition for a writ of certiorari

(No. 81-757) was filed on behalf of the intervenor

W. Wayne Allen on October 20, 1981. The jurisdic

tion of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS, STATUTES

AND REGULATIONS INVOLVED

The Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the

United States Constitution, Section 501(a) and

(c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1954 (26

U.S.C.), Rev. Stat. 1977 (1878 ed.) (42 U.S.C.

1981), and Sections 103 and 615 of the Treasury,

Postal Service, and General Government Appropria

tions Act of 1980, Pub. L. No. 96-74, 93 Stat. 562,

577, are set forth at Interv. Pet. 2-4. The relevant

provisions of Article III of the Constitution and Sec

tion 170(a) and (c ) (2 ) of the Internal Revenue

Code of 1954 (26 U.S.C.) are set forth in Appendix

A , infra.

Revenue Procedure 75-50, 1975-2 Cum. Bull. 587,

the Proposed Revenue Procedure, and the Modified

Proposed Revenue Procedure are set forth respec

tively at Interv. Pet. App. E le-12e, F lf-13f, and

G lg-14g.

STATEMENT

A. Background

Since 1970, the Internal Revenue Service has uni

formly taken the position that a private school will

3

Hot qualify as a tax-exempt organization under Sec

tion 5 0 1 (c )(3 ) of the Internal Revenue Code of

1954, or as an eligible donee of charitable contri

butions deductible under Section 170(c) (2) of the

Code, unless it establishes that its admissions and

educational policies are operated on a racially

non-discriminatory basis. Rev. Proc. 75-50, 1975-2

Cum. Bull. 587 (Interv. Pet. App. E le-12e)

sets forth the currently effective guidelines by which

the Internal Revenue Service determines whether

private schools seeking to acquire or maintain tax-

exempt status have racially nondiscriminatory poli

cies as to students.2 The Revenue Procedure accord

ingly provides (§2 .02) that “ [a] school must show

affirmatively both that it has adopted a racially non

discriminatory policy as to students that is made

known to the general public and that since the adop

tion of that policy it has operated in a bona fide

manner in accordance therewith.” The Revenue Pro

cedure thereafter enumerates requirements that

must be met by each school seeking to establish that

it has adopted and is operating in accordance with

a nondiscriminatory policy. Under the Revenue Pro

cedure, a school seeking to acquire or retain tax-

exempt status and eligibility for tax-deductible con

tributions must state in its charter documents, and

catalogues that it has adopted a non-discriminatory

policy; publicize that policy at least once annually so

as to bring it effectively to the attention of all racial

segments of the community; and maintain records

documenting, inter alia, the racial composition of its

2 In 1976 and 1977, the Internal Revenue Service also issued

more detailed guidelines for the use of revenue agents per

forming field audits o f private schools. See 4 Administration,

Internal Revenue Manual (C'CH) HU 341.11-341.13, at 22,457-9

— 22,460.

students, faculty, and administrative staff. Officials

of a school claiming the benefits of tax exemption are

required to certify to the Internal Revenue Service

each year, under penalties of perjury, that the school

has complied with the guidelines (Interv. Pet. App.

E 7e-8e).3

On August 22, 1978, the Internal Revenue Serv

ice published a proposed revenue procedure (see

Interv. Pet. App. F lf-13 f) seeking to amplify its

policy with respect to schools that had been held by a

court or agency to be racially discriminatory, and

schools that had an insignificant number of minority

students and were formed or substantially expanded

at or about the time of desegregation of the public

schools in the community After lengthy administra

tive hearings and the receipt of a substantial num

ber of adverse written comments, the Internal Rev

3 See Rev. Rul. 71-447, 1971-2 Cum. Bull. 230; Rev. Rul.

75-231, 1975-1 Cum. Bull. 158. See also Prince Edward School

Foundation V. Commissioner, 478 F. Supp. 107 (D.D.C. 1979),

aff’d by unpublished order, No. 79-1622 (D.C. Cir. June 30,

1980), cert, denied, No. 80-484 (Feb. 23, 1981) (non-religious

private school denied tax-exempt status for failure to

make requisite showing that it maintained a racially non-

discriminatory admissions policy where no black child had

been admitted for a period of almost 20 years; directors’

belief in the value of segregated education does not excuse

failure to make requisite showing of nondiscriminatory

policy).

The Internal Revenue Service’s position is before the Court

in two cases presenting the question whether nonprofit cor

porations operating private schools that, on the basis of reli

gious doctrine, maintain racially discriminatory admissions

policies and other racially discriminatory practices qualify as

tax-exempt organizations under Section 5 01 (c )(3 ) of the

Code. See Goldsboro Christian Schools, Inc. V. United States,

No. 81-1, and Bob Jones University V. United States, cert,

granted, No. 81-3 (Oct. 13,1981).

4

5

enue Service issued a revised proposal on February 9,

1979 (Interv. Pet. App. G lg-14g).

The Internal Revenue Service’s proposals led to

the enactment of two related provisions that Con

gress included in the Treasury, Postal Service, and

General Government Appropriations Act of 1980,

Pub. L. No. 96-74, 93 Stat. 559. In Section 615 (93

Stat. 577), known as the Dornan Amendment, Con

gress stipulated that none of the funds made avail

able by the Act be used to carry out the proposed

revenue procedures of 1978 and 1979. In Section 103

(93 Stat. 562), of the same Act, known as the

Ashbrook Amendment, Congress provided that none

of the funds made available by the Act be used

“ to formulate or carry out any rule, policy, proce

dure, guideline, regulation, standard, or measure

which would cause the loss of tax-exempt status to

private, religious or church-operated schools under

Section 5 0 1 (c )(3 ) of the Internal Revenue Code of

1954 unless in effect prior to August 22, 1978.” The

district court observed that “ [t]he effect of [this

congressional] action is to retain in effect, at least

until September, 1980, the presently effective Rev.

Proc. 75-50 * * *” (Interv. Pet. App. A 14a).

B. The Proceedings in this Case

1. Respondents are the parents of 25 black school

children who attend public school in seven states, and

claim to represent a nationwide class of “ several mil

lion individuals” (Interv. Pet. App. A la ) . They

brought this action in the United States District

Court for the District of Columbia against the Sec

retary of the Treasury and the Commissioner of In

ternal Revenue, alleging that these federal officials

“have fostered and encouraged the development, oper

6

ation and expansion of * * * racially segregated pri

vate schools by granting them, or the organizations

that operate them, exemptions from federal taxation

* * 20) 4

Respondents alleged that the actions of the federal

officials injured them and their class, and claimed

injury in the following two respects, “ First, the

exemptions constitute tangible financial aid and other

assistance to racially segregated education. Second,

the exemptions foster and encourage the development

of institutions offering racially segregated educa

tional opportunities for white children avoiding at

tendance in desegregating public school districts, and

thereby also interfere with the efforts of federal

courts, HEW and local school authorities to desegre

gate racially dual school systems” (A. 11).

Although their complaint asserted that “ thousands

of newly created and many existing private schools

have provided racially segregated alternative educa

tional opportunities for white children avoiding at

tendance in desegregating school systems” (A. 9), it

identified only 19 private schools that respondents

claim to be “ racially segregated.” 4 5 Respondents

4 “A .” refers to the appendix filed in the court of appeals.

5 Respondents apparently use the term “ racially segre

gated” to signify only that there are few or no black students

in attendance at a particular school, and not to signify that

the absence of blacks is attributable to racial exclusion prac

tices. At a hearing in the district court, counsel for respond

ents conceded that he did not know whether any of the black

children who are parties to this action would be denied ad

mission by any private school on the basis of race (Tr. of

Motion of Defendants to Dismiss, Nov. 20, 1979, at 66-67).

The complaint identifies a number of private schools that

respondents alleged to fit this description: Harding Academy,

Briarcrest Baptist School System and the Southern Baptist

7

sought declaratory and injunctive relief requiring the

federal officials to deny all applications for tax-

exempt status for, and to revoke tax exemptions held

by all private schools “which have insubstantial or

nonexistent minority enrollments, which are located

in or serve desegregating public school districts”

(A. 11) and which either (A. 37) —

(1) were established or expanded at or about the

time the public school districts in which they

are located or which they serve were desegre

gating;

(2) have been determined in adversary judicial or

administrative proceedings to be racially seg

regated ; or

(3) cannot demonstrate that they do not provide

racially segregated educational opportunities

for white children avoiding attendance in de

segregating public school systems.

Respondents further requested the court to grant

injunctive relief in the nature of mandamus requir

ing the federal officials to revise Rev. Proc. 75-50 and

to substitute the criteria that they urge as the gov

erning standard for granting tax exempt status to

private schools (A. 37).

Schools of Whitehaven, Inc., Memphis, Tennessee; Natchi

toches Academy, Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana; Delta

Christian Academy and Tallulah Academy, Madison Parish,

Louisiana; River Oaks School, Monroe, Louisiana; Holly Hill

Academy and Bowman Academy, Orangeburg, South Caro

lina; Sea Pines Academy, Beaufort County, South Carolina;

Prince Edward Academy, Prince Edward County, Virginia;

Montgomery Academy and St. James Parish School, Mont

gomery, Alabama; Camelot Parochial School, Cairo, Illinois;

Hyde Park Academy, South Boston Heights Academy and

Parkway Academy, Boston, Massachusetts. These schools

are said to serve the desegregating public school districts

where the minor respondents attend school (A. 20-34).

8

2. The district court dismissed respondents’ suit

on three separate grounds. First, it concluded that

respondents had no standing to bring the action be

cause: (a) they had not asserted a distinct, palpable,

and concrete injury; (b) they had not shown that

their alleged injury was attributable to the federal

officials’ actions; (c) there was no certainty that

the relief requested would remove the injury; and

(d) there was not a sufficient degree of concrete ad

verseness between respondents and the federal offi

cials (Interv. Pet. App. A 4a -lla ).

In so ruling, the court relied principally on this

Court’s decision in Simon v. Eastern Ky. Welfare

Rights Organization, 426 U.S. 26 (1976). The court

noted that respondents had not alleged that any of

the private schools cited in the complaint was actually

discriminating in violation of the Constitution or of

federal law, or that any of them or their children had

suffered any discriminatory action or exclusion. It

questioned whether enforcement of respondents’ pro

posed guidelines would ultimately cause any of these

schools to lose tax-exempt status that it would have

otherwise retained. Furthermore, even though the

implementation of respondents’ guidelines might ulti

mately serve to deprive some schools of their exempt

status, the court found that respondents had not

shown that the loss of exemptions would produce a

net change in the desegregation of any particular

school district. The court accordingly concluded that

respondents had failed to show any nexus between

the Internal Revenue Service’s position and the in

jury allegedly suffered. Rather, the court observed

that it appeared probable that any schools forced to

choose would elect to forgo their exempt status rather

than terminate any discriminatory practices (Interv.

Pet. App. A 9a-10a).

9

Second, the district court ruled that responent’s

action was “barred by the doctrine of nonreviewabil

ity” because it “would require this Court to under

take detailed or continuing review of a generalized

IRS enforcement program, or to review complex

issues of tax enforcement policy and of agency re

source allocation” (Interv. Pet. App. A 11a). As

the district court saw the matter, “ Such action would

be tantamount to this Court becoming a ‘shadow

Commissioner of Internal Revenue’ to run the ad

ministration of tax assessments to private schools

in the United States” (id. at 12a).

Finally, the district court concluded that the enact

ment in 1979 of the Ashbrook and Dornan Amend

ments to the General Appropriations Act “ are the

strongest possible expressions of the Congressional

intent that Section 5 0 1 (c )(3 ) of the Internal Rev

enue Code is not susceptible of the construction which

[respondents] would place upon it in this case” (id.

at 14a-15a). While the court acknowledged that the

Ashbrook and Dornan Amendments apparently allow

a federal court to fashion a remedy in this area, it

concluded that it was “ not the business of a federal

court to explicitly thwart the will of Congress or to

otherwise fail to carry it out” (id. at 15a).

3. A divided panel of the court of appeals re

versed (Interv. Pet. App. B lb-58b). It held that re

spondents had standing to sue and remanded the

case for further proceedings. In so ruling, the court

acknowledged that this Court’s decision in Simon v.

Eastern Ky. Welfare Rights Organization, supra,

26, leaves “ the door barely ajar for third party chal

lenges” (Interv. Pet. App. B 16b) of the tax treat

ment of others. It also recognized that its own previ

ous decisions had dismissed for lack of standing suits

brought by persons who sought to litigate the tax

status of other parties.®

But the court concluded that other precedent of

this Court points in the opposite direction and indi

cates “ that black citizens have standing to complain

against government action alleged to give aid or com

fort to private schools practicing race discrimination

in their communities” (Interv. Pet. App. B 15b-16b).

See Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997, aff’g Green v. Con

nolly, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. (1 9 7 1 )); Norwood

v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973); Gilmore v. City of

Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556 (1974). In the court’s

view, those cases “ recognized the right of black citi

zens to insist that their government ‘steer clear’ of

aiding schools in their communities that practice race

discrimination” (Interv. Pet. App. B 24b-25b). The

court therefore ruled that because of “ the centrality

of that right in our contemporary (post-Civil W ar)

constitutional order, [it was] unable to conclude that

Eastern Kentucky speaks to the issue before us”

(ibid.).

In addition, the court found no impediment to the

action in the other grounds of the district court’s

decision dismissing the suit. It concluded that the

doctrine of nonreviewability did not preclude ad

judication of respondents’ claims because they de

rived ultimately from constitutional concerns that

courts, as opposed to administrators, were better

equipped to address (Interv. Pet. App. 32b-35b). Nor

did it view the Ashbrook and Dornan amendments as

prohibitions upon fashioning a remedy. The amend

ments, as it construed them, were merely interim 6

6 See American Society of Travel Agents V. Blumenthal,

566 F.2d 145 (D.C. Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 435 U.S. 947

(1978) ; Tax Analysts & Advocates V. Blumenthal, 566 F.2d

130 (D.C. Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1086 (1978). ,

See also American Jewish Congress V. Vance, 575 F.2d 939

(D.C. Cir. 1978).

10

11

stop orders on agency initiatives and did not purport

to control judicial dispositions (id. at B 25b-30b).

In dissent, Judge Tamm deemed Eastern Ken

tucky controlling. Finding that respondents had

failed to allege a distinct and palpable injury to them

selves, or a sufficient nexus between the Internal

Revenue Service’s actions and whatever injury they

claimed to have suffered, Judge Tamm would have

denied them standing to maintain their suit. In his

view, the majority’s opinion reflected an impermissi

ble shift in focus from the right of respondents to

make their claims to the rights they wished to assert.

The majority, he concluded, had not only expanded

significantly the law of standing, but had also over

stepped the constitutional limits of its jurispruden

tial power (Interv. Pet. App. B 38b-58b).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION

In holding that respondents had standing to bring

this suit in which they seek to compel the Depart

ment of the Treasury to revise its rules governing

the eligibility of private schools for tax-exempt status

and to deny such status to schools having what they

deem to be insufficient minority enrollment, the deci

sion below refused to follow the squarely applicable

precedent of Simon v. Eastern Ky. Welfare Rights

Organization, 426 U.S. 26 (1976), in which this

Court unanimously reversed the same court of ap

peals that decided the instant case. The expansive

view of standing adopted by the court of appeals seri

ously erodes the previously settled “ case or contro

versy” limitation of the Article III jurisdiction of the

federal courts, and once again threatens the orderly

administration of the revenue laws and the system

12

established by Congress for the adjudication of tax

disputes. This Court should grant certiorari to dispel

the uncertainty in the law of standing created by the

decision below.

1. a. In Eastern Kentucky, as here, the plaintiffs

sued to contest the Treasury’s administration of Sec

tions 501(c) (3) and 170(c) (2) of the Internal Reve

nue Code of 1954, not as it affected their own taxes

but as it affected the tax treatment of private insti

tutions not before the court, viz., hospitals that al

legedly had denied free medical care to the indigent

plaintiffs. The plaintiffs in that case likewise alleged

that the Secretary of the Treasury and the Commis

sioner of Internal Revenue had improperly conferred

tax-exempt status to institutions that were not en

titled to them under the Constitution and the tax

laws, and thereby “ encouraged” hospitals to deny

services to indigents.

This Court held that the plaintiffs in that vir

tually identical posture lacked standing to have their

claims adjudicated in a federal court. As the Court

reaffirmed, “ the ‘case or controversy’ limitation of

Art. I ll still requires that a federal court act only

to redress injury that fairly can be traced to the

challenged action of the defendant, and not injury

that results from the independent action of some

third party not before the court” (426 U.S. at 41-

42). There, it was “purely speculative whether the

denials of service specified in the complaint fairly

can be traced to [the Treasury’s] ‘encouragement’ or

instead result from the decisions made by the hos

pitals without regard to the tax implications” (id.

at 42-43.) Moreover, “ [i]t i[was] equally speculative

whether the desired exercise of the court’s remedial

powers in [that] suit would result in the availabil

13

ity to [the plaintiffs] of such services” (ibid.). In

these circumstances, the Court held that the plain

tiffs lacked standing because they had not shown that

“ the asserted injury was the consequence of the de

fendants’ actions; or that prospective relief will re

move the harm.” Worth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490,

505 (1975).

Eastern Kentucky governs this case. Indeed, un

like the plaintiffs in Eastern Kentucky who alleged

that they were denied medical treatment by par

ticular hospitals, respondents’ generalized and at

tenuated allegations concerning the practices of un

identified private schools do not even demonstrate

injury in fact. As the district court pointed out,

“ there is no allegation in the record before the Court

that the ‘target schools’ are actually discriminating

in violation of the Constitution or federal law”

(Interv. Pet. App. A 5a-6a). Nor do respondents

allege that a judgment in their favor would redress

any injury that fairly can be attributed to the chal

lenged action of the Treasury defendants. In this

respect, the court of appeals acknowledged that “ [re

spondents] do not dispute that it is ‘speculative,’

within the Eastern Kentucky frame, whether any

private school would welcome blacks in order to

retain tax exemption or would relinquish exemption

to retain current practices. They claim indifference

as to the course private schools would take” (Interv.

Pet. App. B 18b). While respondents are free to

profess indifference to the response of the private

schools whose policies they decry, “ [a] federal court,

properly cognizant of the Art. I ll limitation upon its

jurisdiction, must require more than respondents have

shown before proceeding to the merits.” Simon v.

Eastern Ky. Welfare Rights Organization, swpra, 426

U.S. at 46.

14

b. Although the court of appeals acknowledged

that Eastern Kentucky “ suggests that litigation con

cerning tax liability is a matter between taxpayer

and IRS, with the door barely ajar for third party

challenges” (Interv. Pet. App. B 16b), it concluded

“ that Eastern Kentucky is not the line appropriately

followed in the matter before us” {id. at 18b). In

the court’s view, Eastern Kentucky was distinguish

able because respondents do not assert “ a claim for

relief against private actors” {ibid.) but rather

against the government.

But the plaintiffs in Eastern Kentuclcy did not

assert a claim against the private hospitals. Like

respondents, they sued the Secretary of the Treasury

to compel a change in the rules governing the tax

exemption accorded to private hospitals that were

claimed to have injured the plaintiffs. Thus, Eastern

Kentucky is squarely in point because both suits

sought a change in governmental conduct. If there is

any difference between the two cases, it is, as we have

pointed out {supra, pages 6, 8, 13), that respondents

have not even asserted any injury at the hands of

the Treasury or any private school— a fact that the

court of appeals conceded in stating that respond

ents “ do not allege that any particular school turns

away students on the basis of race” (Interv. Pet.

App. B 22b n.27). Thus, respondents’ suit is even

further removed from meeting the prerequisites of

standing than the plaintiffs’ claim dismissed by this

Court in Eastern Kentucky.

There is, moreover, no basis for the court of

appeals’ conclusion that “ the standing analysis

should remain unaffected so long as plaintiffs have

a right to demand that their government ‘steer clear’

of aiding discrimination in local educational facilities

and contend, as plaintiffs do here, that current gov-

15

eminent (IRS) practice does not meet the “ steer

clear’ standard” (Interv. Pet. App. B 22b n.27).

Respondents’ asserted right to be free of government

aid to racial discrimination is an undifferentiated

right common to all members of the public that will

not support standing to sue Treasury officials in an

Article III court. See United States v. Richardson,

418 U.S. 166, 176-180 (1974). The fact that re

spondents may have an interest in a matter that they

have sought to identify as a public issue, and that

they may share certain attributes common to per

sons who may have suffered discrimination at the

hands of private schools, is an insufficient ground

upon which to conclude that they have been injured

in fact by such discrimination or that the Secre

tary’s allegedly illegal conduct has actually caused

such discrimination. Wafth v. Seldin, supra, 422

U.S. at 502. In short, respondents are “ individuals

who seek to do no more than vindicate their own

value preference through the judicial process.”

Sierra Club v. Morton, 405 U.S. 727, 740 (1972).

See also O'Shea v. Littleton, 414 U.S. 488, 493-496

(1974); Moose Lodge No. 107 v. Irvis, 407 U.S. 163,

166-168, 171, 178 (i972).

c. In refusing to follow Eastern Kentucky, the

court of appeals declined to “ search for a grand

solution that will unclutter this area of the law and

lead to secure, evenhanded adjudication” (Interv. Pet.

App. B 16b). Rather, it “ select[ed] from two diver

gent lines of Supreme Court decision [s] the one [it]

believe[dj best fit[] the case before [ it ]” and con

cluded that there was precedent to support the prop

osition that “black citizens have standing to com

plain against government action alleged to give aid

or comfort to private schools practicing race dserim-

ination in their communities” (ibid.).

16

But the iaw of standing does not turn upon the

racial characteristics of the plaintiff or the substan

tive issues raised by the complaint. “ Unlike other

associated doctrines, for example, that which re

strains federal courts from deciding political ques

tions, standing ‘focuses on the party seeking to get

his complaint before a federal court and not on the

issues he wishes to have adjudicated.’ ” Simon v.

Eastern Ky. Welfare Rights Organization, supra, 426

U.S, at 37-38, quoting from Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S.

83, 99 (1968). See also Wairth v. Seldin, supra, 422

U.S. at 517-518; Schlesinger v. Reservists to Stop the

War, 418 U.S. 208, 225-227 (1974). Hence, re

spondents are subject to precisely the same require

ment as any other plaintiff and therefore must allege

“ ‘such a personal stake in the outcome of the contro

versy as to warrant [their] invocation of federal-

court jurisdiction and to justify exercise of the

court’s remedial powers on [their] behalf’ ” . Worth

v. Seldin, supra, 422 U.S. at 498-499, quoting from

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 204 (1962).

There are, moreover, no “ divergent lines of Su

preme Court decision” (Interv. Pet. App. B 16b), as

the court of appeals mistakenly believed, that

“ point] ] in opposite directions” {id. at 15b-16b),

or that cast doubt upon the standing analysis of

Eastern Kentucky. In proposing its novel hypothesis

that black citizens can more easily invoke federal-

court jurisdiction to remedy alleged governmental

aid to private discrimination without demonstrating

injury and a nexus between injury and the defend

ant’s conduct, the decision below relied on Green v.

Kennedy, 309 F. Supp. 1127 (1970), continued, 330

F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C.), aff’d, 404 U.S. 997 (1971);

17

Norwood v. Harrison, 418 U.S. 455 (1973); and

Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556 (1974).

But none of those cases warrant, much less dictate,

the conclusion that respondents have standing to

bring this suit. Neither the Court’s summary affirm

ance in Green nor its opinion in Norwood v. Har

rison addressed the standing of the plaintiffs in those

cases. Indeed, unlike this case where the respond

ents’ quarrel with the Internal Revenue Service is

over the effectiveness of its enforcement proceedures

rather than its substantive position,7 the Green litiga

tion was initiated to obtain a ruling that racially

discriminatory schools were not entitled to tax

exemption under Section 5 0 1 (c )(3 ). There, the

plaintiffs identified in their complaint specific private

schools in their communities “ from which Negro stu

dents [were] excluded on the basis of color” (Interv.

Pet. App. B 4b). Moreover, because the Service

adopted the complainants’ position in the midst of the

litigation, “ the Court’s affirmance in Green lacks the

precedential weight of a case involving a truly ad

versary controversy.” Bob Jones University v. Simon,

416 U.S. 725, 740 m il (1974).8

Norwood v. Harrison, supra, is similarly inap

posite on the question of standing. There, the Court

7 We are advised that the Internal Revenue Service has

revoked the tax exemption of more than 100 private schools

that have failed to adopt and publicize racially nondiscrimina-

tory policies.

8 The appeal in Green was taken by intervenors appealing

from an order denying their motion to set aside the district

court’s previous order. The intervenors sought to vindicate

their asserted right to freedom of association. See Motion

to Dismiss or Affirm, Coit V. Green (No. 820, 1970 Term).

18

struck down, a state program under which students

borrowed textbooks without regard to- whether the

students attended private schools with racially dis

criminatory policies. As the Court subsequently ex

plained in Gilmore v. City o f Montgomery, 417 U.S.

556, 570-571 n.10 (1974), “ [t]he plaintiffs in Nor

wood were parties to a school desegregation order and

the relief they sought was directly related to the con

crete injury they suffered.”

The same observation is equally applicable to Gil

more, which was related to a prior class action to

desegregate public parks and recreational facilities.

Indeed, contrary to the decision below, the Court’s

discussion of standing in Gilmore fully supports our

submission that all plaintiffs must meet the tradi

tional requisites of standing to invoke _ federal-court

jurisdiction. As the Court stated, “ [w] itliout a prop

erly developed record, it is not clear that every non

exclusive use of city facilities by school groups, un

like their exclusive use, would result in cognizable

injury to these plaintiffs. The District Court does not

have carte blanche authority to administer city facili

ties simply because there is past or present discrim

ination. The usual prudential tenets limiting the

exercise of judicial power must be observed in this

case as in any other (ibid.).” See also Warth v. Sel-

din, supra.

2. a. The broad authority that Congress has given

the Secretary of the Treasury and the Commissioner

of Internal Revenue over the administration of the

tax laws shows that it did not intend the courts to

entertain suits of this kind. To adjudicate respond

ents’ generalized claims, a broad-scale inquiry into

the enforcement practices of the Internal Revenue

Service, as well as into the racial policies of an in

definite number of private schools, would be re

19

quired.” The role respondents would assume and

have the court assume, “ as virtually continuing moni

tors of the wisdom and soundness of Executive ac

tion,” Laird v. Tatum, 408 U.S. 1, 15 (1972), be

longs to Congress in the exercise of its oversight

function over the operation, administration, and

effects of the internal revenue system (see Sections

8021 through 8023 of the Internal Revenue Code of

1954) and to the President, who, along with the

Treasury officials, is required to “ take Care that the

Laws be faithfully executed.” United States Consti

tution, Article II, Section 3; 26 U.S.C. 7801(a),

7805(a). Absent an assertion of concrete and reme

diable injury directly attributable to unlawful gov

ernment action, the judiciary should not assume the

“ amorphous [task of] general supervision of the

operations of government * * United States v.

Richardson, supra,, 418 U.S. at 192 (Powell, J., con

curring) ; Schlesinger v. Reservists to Stop the War,

418 U.S. 208, 217-223 (1974).

Indeed, the structure for the adjudication of tax

disputes shows that Congress established precisely

defined channels for the conduct of the litigation that

do not permit third parties such as respondents to

challenge the tax treatment of others. The federal

district courts and the Court of Claims have jurisdic

tion over actions by the affected taxpayer for re

funds of taxes paid. 26 U.S.C. 6532, 7422; 28 U.S.C.

1346, 1491. And the Tax Court has been granted

jurisdiction to review deficiency determinations with

respect to income, estate, or gift tax, at the behest 9

9 We are advised by the Internal Revenue Service that there

are approximately 20,000 private schools in the United States

currently recognized as, or claiming to be, tax-exempt under

Section 501(c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code.

20

of the affected taxpayer. 26 U.S.C. 6212, 6213. In

order to confine tax litigation to these prescribed

avenues of review, Congress has generally prohibited

“ any person, whether or not such person is the person

against whom such tax was assessed,” from main

taining a “ suit for the purpose of restraining the

assessment or collection of any tax” (26 U.S.C 7421

(a ), the Anti-Injunction Act) and has prohibited

declaratory relief in all actions “with respect to

Federal taxes” (28 U.S.C. 2201). This Court has

repeatedly required that those and other limitations

on the channels of tax litigation be strictly enforced

so as to accomplish their intended purpose. Louisi

ana v. McAdoo, 234 U.S. 627 (1914); Bob Jones

University v. Simon, 416 U.S. 725 (1974); Enochs

v. Williams Packing Co., 370 U.S. 1 (1962); Flora

v. United States, 362 U.S. 145 (1960); Angelus

Milling Co. v. Commissioner, 325 U.S. 293 (1945);

United States v. Felt & Tarrant Co., 283 U.S. 269

(1931). Moreover, Congress has recently confirmed

that the prohibitions against equity suits against the

Treasury in tax matters remain fully operative in

suits for review7 of agency action. S. Rep. No. 94-

996, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976); H.R. Rep. No. 94-

1656, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 12-13 (1976). In sum, the

structure of our tax system confirms the correctness

of Justice Stewart’s observation that he “cannot now

imagine a case, at least outside the First Amendment

area, where a person whose own tax liability was

not affected ever could have standing to litigate the

tax liability of someone else.” Simon v. Eastern Ky.

Welfare Rights Organization, supra, 426 U.S. at 46

(Stewart, J., concurring).

b. Of course, we do not suggest that policies of

the Internal Revenue Service should be immune from

public inquiry and examination. The broad tax

21

policy questions raised by respondents’ suit are prop

erly a matter for public debate. However, the ap

propriate forum for such a debate concerning the

correctness of Treasury policy is in the Congress

pursuant to the exercise of its oversight of the De

partment of the Treasury and not in the courts,

“Any other conclusion would mean that the Found

ing Fathers intended to set up something in the na

ture of an Athenian democracy or a New' England

town meeting to oversee the conduct of the National

Government by means of lawsuits in federal courts,”

United States v. Richardson, supra, 418 U.S, at 179.

Indeed, public debate has recently been taking

place in Congress over the Treasury’s enforcement

policies in the area o f tax exemptions of private

schools, thereby confirming our submission that re

spondents’ suit is not appropriate for judicial resolu

tion. The Internal Revenue Service has already

sought to supplement its existing procedures for

testing the bona fides of the racial policies of private

schools by proposing to treat as prima facie discrim

inatory schools formed in the wake of desegregation

decrees or adjudicated in the past to be discrimina

tory (Interv. Pet. App. F lf-13 f; Pet App. G Ig-

14g). Had they been adopted, those proposals appar

ently would have gone far toward meeting respond

ents’ objections to the current procedures. They pro

voked, however, a large volume of adverse testimony

before the Internal Revenue Service and Congress,

See Tax Exempt Status of Private Schools: Hear

ings Before the Subcomm. on Oversight of the House

Comm, on Ways and Means, 96th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1979). In the wake of the hearings, the House

Committee on Appropriations recommended that

adoption of the Internal Revenue Service’s proposals

be deferred until after the regular taxwriting com

22

mittees of Congress had determined that they rep

resented a proper interpretation of the tax laws.

H.R. Rep. No. 96-248, 96th Cong., 1st Sess. 14-15

(1979). By means of the so-called Ashbrook and

Doman Amendments to the 1980 Treasury Appro

priations Act, Congress prohibited the Treasury, for

fiscal year 1980, from expending funds to carry out

any private school procedure, standard, or guide

lines more preclusive than those in effect before

August 22, 1978, the date of issuance of the first of

the proposed procedures. Sections 103 and 615,

Treasury, Postal Service, and General Government

Appropriations Act, 1980, Pub. L. No. 96-74, 93

Stat. 562, 576.10

Congress has continued to exercise its oversight

authority in this area. After the court of appeals

rendered its opinion in this case, in which it observed

that the Ashbrook-Doman restrictions then in effect

did not purport to control court orders (Interv. Pet.

App. B 30b), the House of Representatives added to

the 1982 Treasury Appropriations bill a spending

restriction that would specifically encompass court

orders entered after August 22, 1978.11 See 127

10 The Ashbrook-Dornan Amendment expired on October 1,

1980, the end of the 1980 fiscal year, but was reinstated for

the period December 16, 1980, through the close of the 1981

fiscal year, by Sections 101(a )(1 ) and 1 01 (a )(4 ), H.R. J.

Res., 644 of Dec. 16, 1980, Pub. L. No. 96-536, 94 Stat. 3166,

as amended by Section 401, Supplemental Appropriations and

Rescission Act, 1981, Pub. L. No. 97-12, 95 Stat. 95.

11 The House voted to modify the 1980 Ashbrook amend

ment by inserting the phrase “court order” to an amendment

to the Treasury, Postal Service, and General Government Ap

propriations Bill, 1982 (H.R. 4121, 97th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1981)). The bill, which has yet to pass both Houses, thus

provides in Section 616:

None of the funds made available pursuant to the provi

sions of this Act shall be used to formulate or carry out

23

Cong. Rec. H5392-H5398 (daily ed. July 30, 1981).

The Senate Committee on Appropriations subse

quently reported out a spending restriction in iden

tical form. Under a joint resolution making continu

ing appropriations for the current fiscal year, this

provision became effective as of October 1, 1981, at

least through November 20, 1981. Section 101(a)

(3), H.R. J. Res. 325, Pub. L. No. 97-51, 95 Stat. 958,

signed Oct. 1, 1981; see 127 Cong. Rec. H6698-

H6699, H6702 (daily ed. Sept. 30, 1981).12 These

actions by Congress suggest that it is the ap

propriate forum for the resolution of respondents’

quarrel with the Treasury and reinforce the wisdom

of “ the basic principle that to invoke judicial power

the claimant must have ‘a personal stake in the out

come,’ * * *, or a ‘particular, concrete injury’ or

‘a direct injury,’ * * * in short, something more than

‘generalized grievances’ * * *” (citations omitted)

United States v. Richardson, supra, 418 U.S. at 179-

180.

any rule, policy, procedure, guideline, regulation, stand

ard, court order, or measure which would cause the loss

of tax-exempt status to private, religious, or church-

operated schools under Section 501 (c) (3) of the Internal

Revenue Code of 1954 unless in effect prior to August 22,

1978.

12 Those congressional restrictions are prospective in opera

tion and therefore do not impair the Commissioner’s right to

use his existing guidelines and procedures established prior

to August 22, 1978 ( e . g Rev. Proc. 75-50, 1975-2 Cum. Bull.

587), to deny tax benefits to schools not operating under a

bona fide nondiscriminatory policy. See Bob Jones University

v. United States, 639 F.2d 147, 150, n.3 (4th Cir. 1981), cert,

granted, No. 81-3 (Oct. 13, 1981). See also Interv. Pet. App.

B 26b & n.35, 27b-28b, n.40).

24

CONCLUSION

The petition for a writ of certiorari should be

granted.

Respectfully submitted.

November 1981

Rex E. Lee

Solicitor General

John F. Murray

Acting Assistant Attorney General

Stuart A. Smith

Assistant to the Solicitor General

Michael L. Paup

Ernest J. Brown

Robert S. Pomerance

Attorneys

la

APPENDIX

Constitution of the United States of America

Article III.

* * * *

Section 2. The judicial Power shall extend to all

Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Con

stitution, the Laws of the United States, and

Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their

Authority;— to all Cases affecting Ambassadors,

other public Ministers and Consuls ;— to all Cases of

admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction;— to Contro

versies to which the United States shall be a Party;—

to Controversies between two or more States;— be

tween a State and Citizens of another State;— be

tween Citizens of different States,— between Citizens

of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of

different States, and between a State, or the Citizens

thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

* * * * *

Internal Revenue Code of 1954 (26 U .S .C .):

Section 170 C h a r it a b l e , e t c ., Co n tr ib u tio n s

a n d G if t s .

(a) Allowance of Deduction.—

(1) General rule.— There shall be al

lowed as a deduction any charitable con

tribution (as defined in subsection ( c ) ) pay

ment of which is made within the taxable

year. A charitable contribution shall be al

lowable as a deduction only if verified under

regulations prescribed by the Secretary or

his delegate.

* * * * *

2a

(c) [as amended by Section 201, Tax Re

form Act of 1969, Pub. L. No. 91-172, 83 Stat.

487] Charitable Contribution Defined,— For pur

poses of this section, the term “ charitable con

tribution” means a contribution or gift to or for

the use of—

(2) A corporation, trust, or commu

nity chest, fund, or foundation—

(A ) created or organized in the

United States or in any possession

thereof, or under the law of the United

States, any State, the District of Co

lumbia, or any possession of the United

States;

(B ) organized and operated ex

clusively for religious, charitable, sci

entific, literary, or educational pur

poses, or to foster national or interna

tional amateur sports competition (but

only if no part of its activities involve

the provision of athletic facilities or

equipment) or for the prevention of

cruelty to children or animals;

(C) no part of the net earnings of

which inures to the benefit of any pri

vate shareholder or individual; and

(D ) which is not disqualified for

tax exemption under section 501(c) (3)

by reason of attempting to influence

legislation, and which does not parti

cipate in, or intervene in (including

the publishing or distributing of state

ments), any political campaign on be

half of any candidate for public office.

3a

A contribution or gift by a corporation to

a trust, chest, fund, or foundation shall be

deductible by reason of this paragraph only

if it is to be used within the United States

or any of its possessions exclusively for

purposes specified in subparagraph (B) .

^ a(i

☆ GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE; 1 9 8 1 3 5 8 3 0 6 6 9 6