Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corporation Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corporation Brief for Appellant, 1968. 9dc0dd42-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9db39dc1-dd33-4f3d-8951-528969656d20/lee-v-southern-home-sites-corporation-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

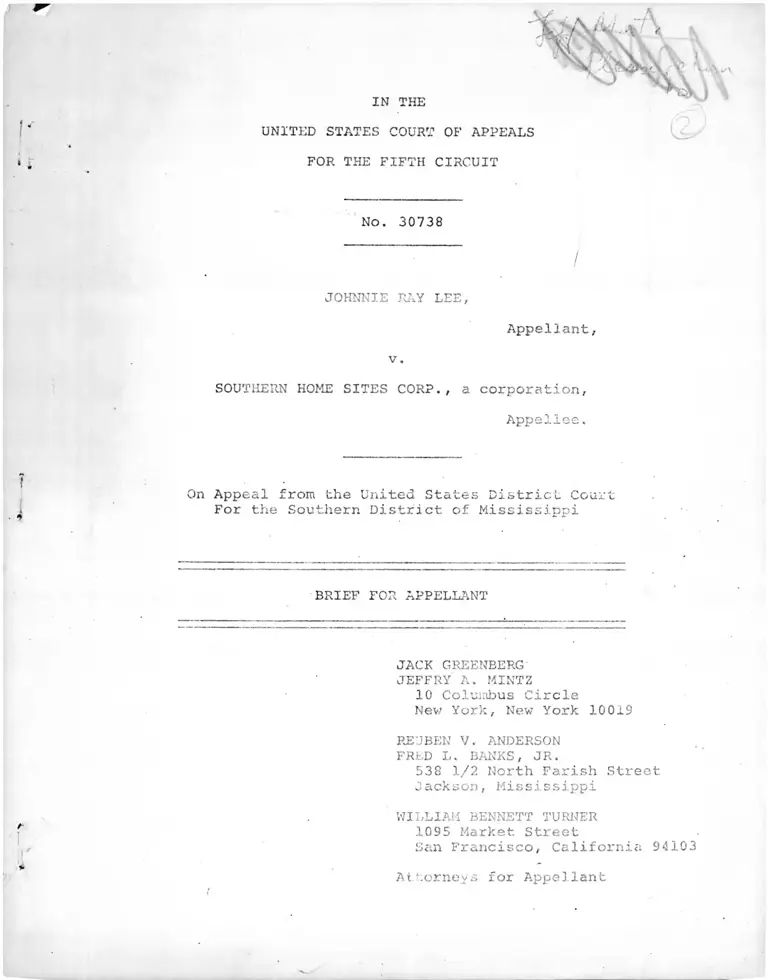

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 30738

I

JOHNNIE RAY LEE,

Appellant,

v.

SOUTHERN HOME SITES CORP., a corporation,

Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Southern District of Mississippi

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT * 10

JACK GREENBERG

JEFFRY A. MINTZ

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

REUBEN V. ANDERSON

FRED L. BANKS, JR.

538 1/2 North Parish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

1095 Market Street

San Francisco, California 94103

Attorneys for Appellant

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES iii

ISSUE PRESENTED 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 2

STATEMENT OF FACTS 5

ARGUMENT

I. The History and the Purpose of Section

1982 Demonstrate that Attorneys' Fees

Should Be Awarded to Plaintiffs Who

Successfully Invoke Its Provisions. 8

II. The Explicit Provision for Attorneys'

Fees in the 1968 Fair Housing Act, A

Procedural Aspect of the Statute,

Should Be Applied to This Case. 22.

CONCLUSIONS 28

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES ?-a9e

Bradley v. School Board of the City of

Richmond, 345 F.2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965) 17

Dolgow v. Anderson, 43 F.R.D. 472,

(E.D. N.Y. 1968) 22

Eisen v. Carlisle S Jacquelin, 391 F.2d

555 (2d Cir. 1968) 22

Gilbert v. Hoisting & Portable Engineers,

237 Or. 139, 390 P.2d 320 (1964) 21

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill,

379 U.S. 306 (1964) 25

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) 26

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp.,

400 F.2d 28 (5th; Cir. 1968) • 16

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.,

392 U.S. 409 (1968) 4,7,8,9,10,11,

12,13,17,18,23

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14

(8th Cir. 1965) 17

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., •

429 F.2d 290 (5th Cir. 1970) 2,4,11

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc.

426 F .2d 534 (5th Cir. 1970) 14,15,22,26

Mills v. Electric Autolite Co.,

396 U.S. 375 (1970) 20,22

Newbern v. Lake Lorelei, Inc., 308 F .Supp.

407; 1 Race Rel. L. Survey 185

(S.D. Ohio, 1968, 1969) 19

n r

Page

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc.,

390 U.S. 400 (1968) 11,15,16,18,

20,24,25

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp.,

398 F .2d 496 (5th Cir. 1968) 16

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.,

411 F .2d 998 (5th Cir. 1969) 16

Pina v. Homsi, 1 Race Rel. L. Survey 18

(D. Mass. July 10, 1969) 19

Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line-R.R.,

186 F.2d 473 (4th Cir. 1951) 21

Sanders v. Russell, 5th Cir. 1968,

401 F .2d 241 11

Smoot v. Fox, 353 F.2d 830

(6th Cir. 1965) 17

Sprague v. Ticonic National Bank,

307 U.S. 161 (1939) 20

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc.,

396 U.S. 229, 239 (1969) 20,27

Terry v. Elmwood Cemetery,

307 F.Supp. 369 (1969) 18,19

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the

City of Durham, 393 U.S. 268 (1969) 26

United States v. Price,

383 U.S. 787 (1966) 11

United States v. Schooner Peggy,

1 Cranch 103 (1801) 26

Vandenbark v. Owens Illinois Co.,

311 U.S. 538 (1941) • 26

i . v

Page

Vaughn v. Atkinson, 369 U.S. 567 (1962) 20

Williams v. Kimbrough, 295 F.Supp. 578,

aff'd, 415 F.2d 875 (5th Cir. 1969),

cert, denied, 396 U.S. 1061 (1970) 17

Ziffrin, Inc. v. United States,

318 U.S. 73 (1943) 26

Brown v. City of Meridian, 356 F.2d 602

(5th Cir. 1966) 27

STATUTES, RULES AND REGULATIONS

Civil Right_s Act of 1866 , Act of

April 7, 1866, c. 31, Section 1,

14 Stat. 27, re-enacted by

Section 18 of the Enforcement Act

of 1870, Act of May 31, 1870, c. 114,

Section 18, 16 Stat. 140, 144

codified in Sections 1977 and 1978

of the Revised Statutes of 1874. 9,10,11

18 U . S . c. Section 241 11

18 U.S.C. Section 242 11

42 u. s. c. Section 1981 2

42 u.s,c. Section 1982 1,2,7,8,9,11,

' 12,15,16,20,21,23

42 U.S.C. Section 1988 27

42 U.S.C. Section 2000a-2 25

42 U.S.C. Section 2 0 0 0 a - 3 (b) 8,14,25

42 U.S.C. Section 2000a.-5 (a) 15

42 U.S.C. Section 2000b et seq. 18

I v

~~~ Page

42 U.S.C. Section 2000c et seq. 18

42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-5(k) 8,25

42 U.S.C. Sections 3601 et seq. 26

4 2 U.S.-C. Section 3603 23

42 .U.S.C. Section 3604 (a) , (b) , (c) & (d) 22

42 U.S.C. Section 3612(b) 8

42 U.S.C. Section 3612 (c) 18,24,25

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 (b) (2) 2

Fed. R. Civ r Pi" 30(g), 37(a),

37(c) , 54 (d) and 56 (g) 25

Fair Housing Act of 1968

Pub. L. 90-284; 82 Stat. 82 18, 23,24

OTHER•AUTHORITIES

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 474 10

114 Cong. Rec. S2308 ' 24

Davidson & Turner, Fair Housing and

Federal Law, 1 ABA Human Rights 36

(1970) ’ 15,23

Gulfport-Biloxi Daily Herald,

June 18, 1968, p. 1 12

Jackson Clarion-Ledger,

June 18, 1968, p. 1 12

Mobile Press, June 18, 1968, p. 3 12

Mobile Press Register,

June 23, 1958, p. 1 12

vi

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

__________________________ V.

NO. 30738

JOHNNIE RAY LEE,

Appellant,

v.

SOUTHERN HOME STTESCORP., a corporation,

Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

For the .'Southern District of Mississippi

___ -BRIEF F.OR APPELLANT

ISSUE PRESENTED

Whether, in a class action under 42 U.S.C. Section

1982 brought by an individual acting as a "private attorney

general" to eliminate systematic racial discrimination

practiced by a real estate developer, the court should award

reasonable attorneys’ fees to the prevailing plaintiff.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is the second appeal to this Court in the

instant case. On the prior appeal (No. 28167), this Court

remanded for findings of fact to justify the District Court's

denial of attorneys' fees. Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp.,

429 F .2d 290 (5th Cir. 1970).

This case was brought pursuant to 42 U.S.C. Sections

1981 and 1982 and the Thirteenth Amendment to challenge

systematic racial discrimination practiced by appellee Southern

Home Sites Corp., a real estate developer. The action was

brought by appellant Johnnie Ray Lee on his own behalf and,

pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b) (2), as a class action on

behalf of similarly situated black citizens who were

discriminated against by Southern Home Sites. The complaint

1/(1.4-9) alleged that appellant had been excluded from buying

a lot in the Southern Home Sites resort development because

of his race, and that appellee's refusal to deal with appellant

was pursuant to a widespread policy and practice of

discrimination against black citizens. Plaintiff-appellant

1/ Nuiribered references preceded by "I" are to pages of the

printed Appendix on the prior appeal, No. 28,167.

References preceded by "II" are to pages of the printed

Appendix on the present appeal, No. 30,738. On Nov. 4,

1970 , this Court granted appellant's motion to limit the

reproduction of the record on this appeal to documents

filed since the printing of the Appendix on the prior

appeal. Additional copies of the prior Appendix have

been filed with the Court together with copies of the

preseiiL Appendix.

-2-

sought injunctive relief, a declaratory judgment, compensatory

and punitive damages and counsel fees.■

The case was tried without a jury on March 18, 1969.

On April 7, 1969, the court below (Nixon, J.) rendered an

opinion (1.42-45) finding that Southern Home Sites had engaged

in racially discriminatory conduct in violation of 42 U.S.C.

Section 1982. On May 14, 1969, the District Court entered

judgment (1.54-56) generally enjoining appellee from

discriminating against black people seeking to purchase lots

in appellee's development, directing Southern Home Sites to

offer appellant Lee a lot and defining the class on whose

behalf the action was maintained. The judgment denied

appellant's claims for money damages and counsel fees. The

court below retained jurisdiction until the judgment would

be fully complied with.

Appellant then sought an order requiring Southern

Home Sites to notify members of the class of their rights

under the court's judgment and to offer lots to members of

the class on the same terms as lots were to be offered to

appellant and as lots had been conveyed to white persons

(1.60-64). On Augusu 6, 1969, the court below denied this

relief. Appellant then appealed to this Court from the

judgment of May 14, 1969, and the order of August 6, 1969.

/

-3-

T'

On July 13, 1970, this Court (Coleman, Goldberg

and Morgan, JJ.) upheld the District Court's denial of money

damages but remanded with instructions to require Southern

Home Sites to notify class members of their rights under the

judgment, including their right to purchase lots on the same

terms as appellant. This Court also directed the District

Court to make findings of fact "sufficient to enable this

court to review the denial of attorneys' fees." Lee v.

Southern Home Sites Corp.., 4 29- F. 2d 296 (5th Cir. 19 70).

On July 20, 1970, the court below ordered the clerk

of the court to publish notices in two Mississippi newspapers

informing class members of their rights under the judgment

(11.5-6). On August 11, 1970, the court below made findings

of fact regarding its denial of attorneys' fees (II.6-9).

The court found that appellant had failed to prove that

Southern Home Sites had knowledge or notice of the Supreme

Court's decision in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

409 (1968) and that, therefore, appellee's discriminatory

conduct was not "malicious, oppressive or so 'unreasonable

and obdurately obstinate' as to warrant an award for attorneys'

fees" (11.8). The District Court thereupon entered a

supplemental decree (August 13, 1970) denying an award of

attorneys' fees (II.9). This appeal followed.

-4-

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Appellant Johnnie Ray Lee is a black citizen who

resides in Columbia, Mississippi. Appellee Southern Home

/

Sites Corp. is a Mississippi corporation which is in the

business of developing resort areas and selling lots or

interests in real estate (1.6,17). It owns and operates a

development called Ocean Beach Estates, located near Ocean

Springs and Pascagoula, Mississippi (Id.).

The development at Ocean Beach Estates contains a

total of 1,653 lots (1.27,33,43). As of the time of trial,

1,206 of the lots had been sold (Id.). Thus, more than 400

lots remained available (1.96-97). At that time, appellee

was holding Jots off- the market, because developments on

adjacent property were causing Southern Home Sites lots to

increase in value (1.114,43).

On July 30, 1968, appellee sent a form letter to

appellant offering him a lot stated to be worth $600 for

$49.50 in cash (1.6,17,42). In 1968 alone, Southern Home -

Sites sent probably more than a thousand such letters to

persons throughout the State of Mississippi and outside

Mississippi (1.86-8.7). The letters were sent as a promotional

venture, with the idea that persons sold lots at bargain

prices would tell their friends and thus increase appellee's

l

-5-

sales (1.113,43). At the time of trial, Southern Home Sites

had conveyed 119 lots on the $49.50 terms set forth in the

letter to appellant (1.93,25,31-32,27,33).

Appellee's agents collected names for the promotional

mailing list at boat shows, county fairs, etc. (1.87,32). In

mailing the letters containing the promotional offers, appellee

made no effort whatever to ascertain the race of persons to

whom the letters were sent (1.26,32). Thus, thousands of

letters were sent, indiscriminately to both black and white

persons.

The letters sent to citizens throughout the area

stated baldly that in order for the recipient to take advantage

of the offer, "you must be a member of the white race" (1.42,

6,17). Although Southern Home Site's pretended to justify this

condition on the ground that "only the white race" would help

appellee advertise its development (1.32), white purchasers

of lots pursuant to the promotional scheme were never asked

to advertise and no such condition was ever demanded by

Southern Home Sites (1.104-105,108).

Shortly after receiving his letter from appellee,

Johnnie Ray Lee traveled to appellee's office at Ocean Springs

(1.42-43,6-7,12,13-14,18). He took with him the letter and

$50 in cash and was ready, willing and able to purchase a lot

/ ’

-6-

on the terras set forth in the letter, except for the racial

limitation (1.43,74,76). However, at the Southern Home Sites

office he was bluntly told by appellee's agent that the

development "wasn't for Negroes," and the agent refused to

do business with him (1.75,82/43). At Ocean Beach Estates,

black people were not permitted to buy lots (1.26,33). Not

only was Ocean Beach Estates maintained as a lily-white

preserve, but appellee planned a separate, all-black

development., and^kept a waiting list of black applicants for

that development (1.75,76,82; Plaintiff's Exhs. 2 and 3).

On October 15, 1968, appellant Lee brought this

class action in the court below. He obtained a broad

injunction prohibiting Southern Home Sites from discriminating

against black citizens on the ground of race. The action was

based primarily on 42 U.S.C. Section 1982, which was interpreted

by the Supreme-Court to bar all racial discrimination in the

sale of real estate. Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

4.09 (1968). The letter to appellant Lee was sent by Southern

Home Sites about six weeks after the Jones decision, and

appellant was excluded from the resort development about two

months after the decision. At trial, appellant made no attempt

to show that Southern Home Sites had actual knowledge of the

Jones decision at the time of its discriminatory conduct; nor

did the developer seek to show its ignorance of the decision.

-7-

On August 11, 1.970, the District Court found as a fact that

because of appellant's failure to prove appellee's knowledge

or notice of Jones, appellee's conduct was not "malicious,

oppressive or so 'unreasonable and obdurately obstinate' as

to warrant an award for attorneys' fees" (II.8). Appellant

here maintains that the denial of attorneys' fees was

erroneous as a matter of law.

ARGUMENT

I. The History and the Purpose of Section 1982 Demonstrate

That Attorneys' Fees Should Be Awarded to Plaintiffs

Who Successfully Invoke Its Provisions.

Unlike many of the recent statutes authorizing

2/

private suits to vindicate denials of equal rights, 42 U.S.C.

Section 1982 does not expressly authorize the granting of

attorneys' fees to successful plaintiffs. An analysis of the

history and purpose of Section 1982 readily demonstrates,

however, that the allowance of attorneys' fees to successful

plaintiffs invoking its provisions is a proper means of

3/

"fashioning an effective equitable remedy" for its enforcement

2/ See 42 U.S.C. Section 2000a-3(b) (public accommodations);

42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-5(k) (equal employment); 42 U.S.C.

Section 3612(b) (fair housing).

3/ Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 414, n.13 (1968)

/ -8-

Section 1982 is derived from Section 1 of the Civil

4/Rights Act of 1866. The history and meaning of the statute

are discussed at length in the opinion of the Supreme Court

in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 420-444 (1968).

There, the Court held that (1) the statute was intended to bar

all racial discrimination, private as well as public, in the

sale or rental of property, and (2) as thus construed, it was

a valid exercise of the power of Congress to enforce the

5/

Thirteenth Amendment.

6/

As originally enacted, the Civil Rights Act of 1866

was to be enforced primarily through criminal prosecutions

brought by federal district attorneys against persons who

violated its provisions. The sponsors of the bill feared that

permitting only a private right of action would be insufficient

to eradicate either the racial wrongs being perpetrated or the

4/ Act of April 7 , 1866 , c. .31, Section 1, 14 Stat. 27,

re-enacted by Section 18 of the Enforcement Act of 1870,

Act of May 31, 1870, c. 114, Section 18, 16 Stat. 140, 144,

codified in Sections 1977 and 1978 of the Revised Statutes

of 1874.

5/ It was the Jones decision which led the District Court to

hold on the merits that Southern Home Sites' discrimination

violated Section 1982 and to issue the injunction barring

future discrimination and ordering the sale of a lot to

Lee (1.44) .

6/ See n.4, supra.

- 9

temper which gave rise to and sustained them. They expressed

Partj-cu-J-ar concern about the likelihood that those persons

whom the Act sought to protect could not bear the expense of

enforcing their rights if they were not assisted by the

8/

federal attorneys.

In the intervening reenactments of the Act of 1866,

tne penal provisions which originally accompanied it have been

7/

8/

Introducing the bill on January 5, 1866, Senator Trumbull

stated its objective was to give effect to the declaration

contained in the Thirteenth Amendment and to secure to all

persons within the United States practical freedom. "There

is very little importance in the general declaration of

abstract truths and principles unless they can be carried

into effect, unless the persons who are to be affected by

them have some means of availing themselves of their

benefits." Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 474, quoted

m Jones v. Alfred H, Mayer Co., supra, at 431-32.

James Wilson, who introduced the bill into the House,

expressed in greater detail the legislative intention as

he responded to Ohio Congressman Bingham's motion to

recommit and to "strike out all parts of the bill which

are penal and authorize criminal proceedings and in lieu

thereof to give injured citizens a civil action in the

United States Courts..." Id. at 1293. Between the two,

Mr. Wilson said, There is no difference in the principle

involved... There__is__a difference in regard to the expense

of protection. There is also a difference~as~to'"the

effectiveness of the two modes...This bill proposes that

the humblest citizen shaIJL̂ have fu 11 and ample protection

a ~̂ the cost of the Government, whose duty it is to protect

him. The Amendment of the gentleman recognizes the principl

involved, but it says that the, citizen despoiled of his

rights...must press his own way through the courts and pay

the .costs attendant thereon. This may do foFthe rich, but

to the poor, who need protection, it is mockery .T. " Id. at""

1295 (emphasis added). ~ —

-10-

'

separated or eliminated, so that today Section 1982 is

"enforceable only by private parties acting on their own

initiative." Jones v. Alfred PI. Mayer Co., supra, at 417.

However, as the Court noted in Jones, "The fact that 42 U.S.C.

Section 1982 is couched in declaratory terms and provides no

explicit method of enforcement does not, of course, prevent

a federal court from fashioning an effective equitable remedy."

Id. at 414, n .13. And as this Court stated in its previous

opinion in the instant case:

"In the area of civil rights, many cases have

either allowed or implicitly recognized the

discretionary power of a district judge to

award attorneys' fees in a proper case in

the absence of express statutory provision

Icitations omitted] and especially so when

one considers that much of the elimination

of unlawful racial discrimination necessarily

devolves upon private litigants and their

attorneys, cf. Newman v. Piggie Park-

Enterprises ,_Inc. , 39 0 U.S; 400, 402 (1968),

and the general problems of representation in

civil rights cases. See Sanders v. Russell, .

5th Cir. 1968, 401 F.2d 241." Lee v. Southern

Home Sites Corp., 429 F.2d 290, 295 (5th Cir.

I970T.

9/

9/ The only remaining criminal statute derived from the Act

is 18 U.S.C. Section 242. See United States v. Price,

383 U.S. 787, 801-02 (1966). While Section 242 is limited

to actions taken "under color of law," it may well be that

18 U.S.C. Section 241, derived from the Enforcement Act of

1870 (the reenactment of Section 1982, see n.4, supra)

would permit criminal prosecutions against persons who

conspire to interfere with the rights guaranteed by

Section 1982.

11

In Jones, the Supreme Court resurrected Section 1982

and held that it operated as a fair housing statute to outlaw

10/

all racial discrimination in the sale of real property.

We subrr.it that the effectiveness of Section 1982 as a guarantee

of equal housing opportunity would be vastly diminished by

limiting the availability -of attorneys' fees under the standard

followed by the court below. The District Court here denied

fees on the around that appellant failed to prove that Southern

Home Sites had actual knowledge or notice of the Supreme

Court's decision in Jones and that, accordingly, appellee's

discriminatory conduct was not "malicious, oppressive or so

'unreasonable and obdurately obstinate' as to warrant an award

11/for attorneys' fees" (1.8) . The District Court did not

10/ The Court noted and agreed with the statement of the

Attorney General at oral argument: "The fact that the

statute lay partially dormant for many years 'cannot be

held to diminish its force today." 392 U.S. at 437.

11/ The court went further to find that in the absence of

such proof, Southern Home Sites did not in fact have

notice of the Jones decision (II.7). This inference is

without any evidentiary support whatever and is clearly

erroneous. It might be noted that the Jones decision

made headlines in every newspaper in the South. See,

e.g., the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, June 18, 1968, p. 1;

the Gulfport--Biloxi Daily Herald, June 18, 1968, p. 1;

the Mobile Press, June 18, 1968, p. 3; the Mobile Press

Register, June 23, 1968, p. 1. It seems exceedingly

unlikely that a large real estate developer like Southern

Home Sites would remain wholly ignorant of a landmark

decision directly affecting its business; In any event,

as will be demonstrated below, an award-of attorneys' fees

cannot be conditioned on proof that the defendant actually

knew the law condemning its racially discriminatory practices.

-12-

mention the facts that (1) six weeks after the Jones decision,

Southern Home Sites distributed thousands of racially insulting

letters, with no attempt whatever to determine the race of

addressees and thus with callous disregard for the feelings

of black recipients; (2) appellee's policy was not only to

keep Ocean Beach Estates a lily-white preserve, but it planned

a wholly segregated all-black development; and (3) appellee's

defense in the trial court was frivolous— appellee contended

that the promotional offers were for a "gift" and that under

Mississippi law the donor had complete discretion to select

his donees (1.32-34,37; defendant's response to motion for

12/

summary judgment).

The reason, for the District Court's denial of

counsel fees — that appellee did not "know" of the Jones

decision--might be appropriate if the question were whether

to impose punitive damages and if some showing of willful or

malicious conduct were required. But here we are dealing with

whether counsel fees may be awarded, and the District Court s

approach seems wholly inappropriate. Indeed, the approach of

12/ Appellant proved at trial that the transactions could in

no way be considered "gifts." Recipients of promotional

offers were required to pay $49.50 in cash to o.otain a

lot (I..93,25,31-32,27,33) . All 119 of these transactions

were accounted for on Southern Home Sites' books in

exactly the same manner as all cash purchases of lots

(1.94-95,118). Appellee introduced no evidence of

donative intent.

-13-

ths court below has already been rejected by this Court in

the analogous case of Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc.,

426 F .2d 534 (5th Cir. 1970). In Miller, the district court

had denied attorneys' fees to a successful plaintiff in a suit

challenging racial discrimination under Title II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964. The-reason for the denial was that at

the time of the discriminatory act (and, indeed, even up to

and after the decision of a panel of this Court), the defendant

company was not deemed in violation of the law; not until the

en banc decision of this Court was the defendant held to be

covered by Title II. This Court reversed the denial of fees,

stating that the defendant

". . .became subject to the prescribed

judicial relief not because the Court said

so, but rather because the Court said— even

perhaps for the very first time--that the

Congress said so." 426 F .2d at 536.

The Court also ruled that the defendant's subjective "good

faith" was not to be considered as a justification for denying

counsel fees. Even though the defendant in Miller, unlike

appellee here, advanced no frivolous defenses, and even'though

several judges agreed with its position, this Court directed

an award of attorneys' fees.

To be sure, Miller involved a statute containing an

express provision for attorneys' fees. See '42 U.S.C. Section

2000a-3 (b) (fees may be granted in the "discretion" of the

court). But this Court's reasoning applies equally to

Section 1982:

"Congress did not intend that vindication of

statutorily guaranteed rights would depend

on the rare likelihood of economic resources

in the private party (or class members) or

the availability of legal assistance from

charity--individual, collective or organized.

An enactment aimed at legislatively.enhancing

human rights and the dignity of man through

equality of treatment would hardly be served

by compelling victims to seek out charitable

help." 426 F.2d at 539.

Miller relied on the Supreme.Court1s decision in Newman v.

Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968). In

Piggie Park, the Court noted that since the statute, like

Section 1982, provides no administrative agency or criminal

prosecutions to enforce its mandate, its effectiveness depends

13/

on the ability of private litigants to maintain civil suits.

Said the Court:

"If [the plaintiff]’ obtains an injunction,

he does so not fox' himself alone but also

as a "private attorney general," vindicating

a policy that Congress considered of the

highest priority. If successful plaintiffs

were l'outinely 'forced to bear their own

attorneys' fees, few aggrieved parties would

be in a position to advance the public

interest by invoking the injunctive powers

of the federal courts." 390 U.S. at 402

(footnote omitted).

13/ The Attorney' General of the Uniued States is empowered to

bring suit to enforce Title II. See 42 U.S.C. Section

2000a-5 (a) . But Section 1982 has no such provision and

its enforcement depends wholly on private civil actions.

See generally, on the need for counsel fee awards to

enforce fair housing statutes, Davidson and Turner, Fair

Ho.usincf and Fedeiol Law, 1 ABA Human Rights 36 , 49-50 (1970) .

-15-

This Court has subsequently applied the "private attorney

general" doctrine not only in Miller but also in cases arising

under the fair employment provisions of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964. See Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 411

F .2d 998, 1005 (5th Cir. 1969); Jenkins v. United Gas Corp.,

400 F .2d 28, 32-33 (5th Cir. 1968); Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach

Corp., 398 F .2d 496, 499 (5th Cir. 1968).

The teaching of Piggie Park and its progeny is that

counsel fees should be awarded to the successful plaintiff

unless "special circumstances render such an award unjust."

390 U.S. at 402. It is irrelevant whether the defenses

advanced by the discriminating party were frivolous or

plausible. And it is perfectly clear under Miller that the

test cannot be whether the defendant had actual knowledge of

the law.

The fact that Section 1982, unlike more recently

14/

enacted civil rights statutes, does not explicitly provide

for attorneys' fees should not justify deviation from the

Piggie Park standard. First, as demonstrated above, Congress

originally provided that the enforcement of the rights

guaranteed by Section 1982 should be undertaken by government

attorneys for the very reason that the persons aggrieved could

14/ See n.2, supra.

not bear the cost of litigation. Nothing in the subsequent

revisions which have made those rights "enforceable only by

16/

private parties acting on their own initiative" indicates

that Congress intended to limit their availability to those

few who could bear the cost of litigation. The allowance of

attorneys' fees under the Piggie Park standard clearly would

serve to fulfill the legislative intent and to effectuate

the Congressional policy expressed in Section 1982.

Second, the cases relied on by the District Court

to support its standard of requiring "unreasonable, obdurate

17/

obstinacy" by a defendant before attorneys’ fees can be

allowed were all in the context of school desegregation suits,

where the plaintiffs sought to enforce rights which were

judicially declared and which were not an explicit .statutory

15/

15/ See nn. 6 and 7 and accompanying text, supra.

16/ Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., supra, at 417.

17/ Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 345 F .2d

310, 321 (4th Cir. 1965); cf. Id. at 324-5 (Sobeloff and

Bell, JJ. dissenting); Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F .2d 14 (8th

Cir. 1965); Williams v. Kimbrough, 295 F.Supp. 578, 587,

aff'd, 415 F.2d 875 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 396

U~S. 106) (1970). Smoot v. Fox, 353 F .2d 830 J6th Cir.

1965), also cited by the District Court, was a common

law libel, ciction and is in no way relevant to this case.

-17-

»

i

"policy that Congress considered of the highest priority."

Moreover, the defendant here is a profit-making corporation

engaged in racial discrimination as part of its business, not

a school board composed of unpaid public servants. Whatever

may be the policy for denying counsel fees in school cases,

the policy does not apply here. Indeed, the explicit

I V

provision for counsel fees in the Fair Housing Act of 1968

establishes a Congressional policy strongly favoring counsel

fee awards in housing discrimination cases.

Other district courts granting injunctive relief

in suits under Section 1982 have awarded attorneys' fees. In

Terry v. Elmwood Cemetery, 307 F.Supp. 369 (1969), suit was

brought to compel the defendant cemetery to sell a burial plot

to a black mother for the grave of her son, who was killed in

action in Viet Nam. The cemetery refused to sell the plot

18/ Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, supra, at 402. See

Cong/ Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 474, quoted in Jones

v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., supra, at 431-32. Also, Congress

has now authorized the Attorney General to file suits on

behalf of the United States to desegregate schools. See

Title IV of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

Section 2000c et seq. See also Title III, 42 U.S.C.

Section 2000b et seq., authorizing the Attorney General

to sue to challenge discriminatory practices in state

owned or operated facilities. Much of the cost of

litigation to desegregate schools is thus borne by the

federal government.

19/ 42 U.S.C. Section 3612(c).

I

-18-

solely because of the race of the deceased. Chief Judge Lynne

carefully analyzed the Jones decision and the lower court

cases which followed it and held that the refusal to sell the

burial plot was a violation of Section 1982. In the final

iudqnient (which followed the reported opinion) , attorneys

20/

fees in the amount of $2500 were awarded.

Newbern v. Lake Lorelei, Inc., 308 F .Supp. 407;

1 Race Rel. L. Survey 185'Ts ."d . Ohio, 1968 , 1969), which was

relied upon in Terry, is very similar to the instant case in

that it involved a large real estate development from which

blacks were excluded. The case was brought as a class action

by an individual who had been refused a lot in the development.

The court defined the class as "members of the Negro race" who

had been similarly excluded, Id. at 417, the same delimitation

of the class made by the lower court in this case (1.49) . By

a supplemental order, the court in Newbern awarded attorneys

21/

fees in the amount of $1000. Also, in Pina v. Homsi, 1 Race

Rel. L. Survey 18 (D. Mass. July 10, 1969), the plaintiffs were

20/ Terry v. Elmwood Cemetery, N.D. Ala. Civ. No. 69-493,

order of January 29, 1970. Terry is a particularly

significant case in this regard as the property there

involved is not covered by the provisions of the 1968

Fair Housing Act and suit, even today, could be

maintained only under the provisions of Section 1982.

21/ Newbern v. Lake Lorelei, Inc., 1-Race Rel. L. Survey 185

(S.D. Ohio, March 12, 1969).

-19-

refused an apartment because the husband was black. Under

Section 1982, the court awarded compensatory damages and

attorneys' fees.

These cases under Section 1982 follow the well

established principle that federal courts have equitable power

to award counsel fees in appropriate cases even in the absence

of statutory authorization. See Mills v. Electric Autolite Co.,

396 U.S. 375 (1970); Vaughn v. Atkinson, 369 U.S. 567 (1962);

Sprague v. Ticonic Nationa.l-.Bank, 307 U.S. 161 (1939); Newman

v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., supra, 390 U.S. at 402, n.4.

The instant case presents special reasons supporting an award

of counsel fees:

(1) Section 1982 expresses a national policy of

the highest priority — the eradication of racial discrimination

in housing. Therefore, appellant acts here as a "private

attorney general" in vindicating the statutory right to equal

housing opportunity. Cf. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,

Inc., supra, 390 U.S. ah’ 402. And as the Supreme Court said

of Section 1982, ".The existence of a statutory right implies

the existence of all necessary and appropriate remedies."

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229, 239 (1969).

(2) The discrimination involved here was systematic

and deliberate; it was not isolated or accidental. Appellant

Lee challenged not only the refusal to sell him a lot but also

-20-

the policy of (a) distributing offers addressed to the general

public but acceptable only by "a member of the white race,"

and (b) creating a wholly segregated all-black development.

This kind of action ought to be encouraged by an award of

counsel fees under Section 1982, so that neither aggrieved

parties nor their attorneys need subsidize from their own

•

pockets the essentially public activity of correcting

22/

systematic racial discrimination.

(3) This is a class action on behalf of all blacks

discriminated against by Southern Home Sites. If the action

had not been brought, the rights of class members would never

.

have been vindicated, because their claims are too small to

■

22/ Awarding counsel fees to encourage "public" litigation

by private parties is an accepted device. For example,

in Oregon, union members who succeed in suing union

officers guilty of wrongdoing are entitled to counsel

fees both at the trial level and on appeal, because they

are protecting an interest of the general public:

If those who wish to preserve the internal

democracy of the union are required to pay

out of their own pockets the cost of employing

counsel, they are not apt to take legal action

to correct the abuse. . . . The allowance of

attorneys1 fees both in the trial court and

on appeal will tend to encourage union members

to bring into court their complaints of union

mis-management and thus the public interest as

well as the interest of the union will be

served.

Gilbert v. Hoisting & Portable Engineers, 237 Or. 139,

390 P.2d 320 (1964). See also Rolax v. Atlantic Coast

Line R.R., 186 F .2d 473 (4th Cir. 1951).

21-

the policy of (a) distributing offers addressed to the general

public but acceptable only by "a member of the white race,"

and (b) creating a wholly segregated all-black development.

This kind of action ought to be encouraged by an award of

counsel fees under Section 1982, so that neither aggrieved

parties nor their attorneys need subsidize from their own

pockets the essentially public activity of correcting

22/

systematic racial discrimination.

(3) This is a class action on behalf of all blacks

discriminated against by Southern Home Sites. If the action

had not been brought, the rights of class members would never

have been vindicated, because their claims are too small to

"22/ Awarding counsel fees to encourage "public" litigation

by private parties is.an accepted device. For example,

in Oregon, union members who succeed in suing union

officers guilty of wrongdoing are entitled to counsel

fees both at the trial level and on appeal, because they

are protecting an interest of the general public:

If those who wish to preserve the internal

democracy of the union are required to pay

out of their own pockets the cost of employing

counsel, they are not apt to take legal action

to correct the abuse. . . . The allowance of

attorneys' fees both in the trial court and

on appeal will tend to encourage union members

to bring into court their complaints of union

mis-management and thus the public interest as

well as the interest of the union will be

served.

Gilbert v. Hoisting & Portable Engineers, 237 Or. 139,

390 P.2d 320 (1964). See’also Rolax v. Atlantic Coast

Line P.R., 186 F.2d 473 (4th Cir. 1951) .

-21-

justify individual litigation. Cf. Eisen v. Carlisle &

Jacquelin, 391 F.2d 555, 560 (2d Cir. 1968); Dolgow v.

Anderson, 43 F.R.D. 472, 484-87 (E.D. N.Y. 1968). And since

individual suits would not have been brought, the statute

outlawing appellee's conduct would have gone unenforced. As

the Supreme Court said in granting fees in Mills v. Electric

Autolite Co., supra, "private. . .actions of this sort. . .

furnish a benefit to all. . .by providing an important means

of enforcement of the. . .statute." 396 U.S. at 396.

Therefore, it was error for the court below to

withhold counsel fees on the ground that appellee was not

on notice of the Jones decision and did not act maliciously

or obstinately. The case should be remanded with instructions

to award reasonable attorneys' fees covering all proceedings

in the District Court and on both appeals. See Miller v.

Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d 534, 539 (5th Cir. 1970).

11. The Explicit Provision For Attorneys' Fees In- The 1968

Fair housing Act, A Procedural Aspect of the Statute,

Should Be Applied to This Case.

The discriminatory acts of Southern Home Sites

would clearly have been covered by specific provisions of the

Fair Housing Act of 1968 had they taken place after

December 31 , 1968 . See 42 U.S.'C. Section 3604 (a) , (b) , (c) and

(d). Because they occurred during 1968 and related to housing

-22-

substantive prohibitions of the Act did not cover them.

Appellant Lee was thus compelled, in this action filed

October 15, 1968, to base his substantive claim that the acts

were illegal on Section 1982. But invoking the procedural

and remedial provisions of the 1968 Act would not run counter

to Congressional intention. Indeed, the legislative history

of the Act indicates that Congress had in mind as one of its

purposes the effectuation of Section 1982:

[T]he Senate Subcommittee on Housing and

Urban Affairs was informed in hearings held

after the Court of Appeals had rendered its

decision in the case that Section 1982 might

well be "a presently valid federal statutory

ban against discrimination by private persons

in the sale or lease of real property." The

Subcommittee was told, however, that even if

this Court should so construe Section 1982,

the existence of that statute would not

"eliminate the need for congressional action"

to spell out "responsibility on the part of

the federal government to enforce the rights

it protects." The point was made that, in

light of the many diff:icuIties confronted by

private litigants seeking to. enforce such

rights on~their own, "legislation is needed

to establish federal machinery for enforcement

of the rights guaranteed under- Section 1982...."

quoted in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

at 415-16 (emphasis'added; footnotes omitted).

not owned or financed by the federal government, the

23/

23/ 42 U.S.C. Section 3603. The substantive prohibitions

covered only housing owned or financed by the federal

government during 1968. Id_. It might be noted that the

1968 Act even now covers only "dwellings" and does not cover

personal, commercial, or industrial property. Of course,

Section 1982 covers all property. Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer

Co., 392 U.S. 409, 413 (1968); see generally, on the coverage

of the respective statutes,. Davidson find Turner, Fair Housing

and'Federal Law, 1 ABA Human Rights 36 (1970).

Thus, it seems entirely appropriate to apply the "machinery"

of the Fair Housing Act--in this context, its provision for

attorneys' fees--to assist in the enforcement of the Section

1982 rights which were violated here.

/

The 1968 Fair Housing Act explicitly provides for

the allowance of "reasonable attorney fees in the case of a

prevailing plaintiff" suing under its provisions. 42 U.S.C.

24/Section 3612(c). Since attorneys' fees are universally

24/ The provision is phrased in stronger language than the

analogous provision in Title II of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, which authorizes attorneys' fees in the

"discretion" of the court. The Title II provision has

been interpreted to mean that fees must be awarded in

virtually every successful case. Newman v. Piggie Park

Hnterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968). Thus the Fair

Housing Act should be interpreted to confer a right to

recover fees, except where the plaintiff is wealthy

enough to afford easily the expense of litigation.

Also, the legislative history indicates that successful

plaintiffs who are not even obligated to pay their

. lawyers--for example, persons represented by legal

services offices or private legal associ ati.ons--are

entitled to recover fees, on the Piggie Park theory that

"private attorneys general" play an important role in

vindicating constitutional rights. See remarks of

Senator Hart (floor manager of the bill), 114 Cong. Rec.

S2308 (daily ed. March 6, 1968).

-24-

we submit that this

'---- 25/

considered a procedural matter,

provision of the Act should be applied to the instant case.

This type of application of new Congressional policy

to prior conduct in the civil rights field was seen in Hamm v.

City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 (1964), where the Court held

26/

that the statutory prohibition of interference with equal

access to public accommodations abated all pending criminal

prosecutions of persons who had sought such access prior to

the passage of the Act. Here, an appreciably less significant

retrospective application is sought, since the Fair Housing

25/ Rules governing the retrospective application of the

substantive portions of a statute need not be discussed

here. Provisions for attorneys' fees are without a doubt

procedural. In the cases and statutes pertinent hereto,

counsel fees are awarded as part of the costs. Provisions

which govern the^r allowance are found in the procedural

sections of the Fair Housing and other Civil Rights Acts.

42 U.S.C. Section 3612(c); 42 U.S.C. Section 2000a-3(b);

42 U.S.C Section 2000e-5 (k) .

In Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400,

403~(1968), the Supreme Court ordered the district court

on remand to "include reasonable counsel fees as part of

the costs to be assessed against the respondents." This

Court in Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d

534, 539 (5th Cir. 1970), recognized that "The Newman

rule. . .calls for the allowance of attorney fees as part

of the costs." (emphasis added)

See also Rules 30(g), 37(a), 37(c), 54(d) and 56(g) of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. All refer to attorneys'

fees as an element of costs or expenses.

26/ Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,_42 U.S.C.

Section 2000a-2.

-25-

Act was enacted well before Southern Home Sites engaged in

27/

its discriminatory conduct and the conduct was in any event

illegal under Section 1982.

Also relevant is the principle of Thorpe v. Housing

Authority of the City of Durham, 393 U.S. 268 (1969), that

when there is a change in the law while a case is pending in

the courts, the court should generally apply the law in effect

28/

at the time of its decision. Here, the 1968 law was fully

applicable prior to the first judicial opinion in this case

(the District Court's opinion of April 7, 1969), and it

seems quite proper to apply its procedural devices here.

Finally, the Supreme Court has recently said of

Section 1982 and the Fair Housing Act that "the 1866 Civil

Rights Act considered in Jones should be read together with

the later statute on the same subject. . . . " Hunter v.

29/

Erickson, 393 U.S. 385, 388 (1969). Moreover, there is

27/ The law was enacted on April 11, 1968, Pub. L. 90-284;

82 Stat. 82; 42 U.S.C. Sections 3601 et seq.

28/ See also, United States v. Schooner Peggy, 1 Cranch 103,

110 (1801); Vandenbark v. Owens Illinois Co., 311 U.S.

538 (1941); zTffrln, Inc. v. United States, 318 U.S. 73

(1943).

29/ The Court was there discussing whether the earlier law

should be read so as to incorporate the provision of the

1968 statute preserving local fair housing laws, and held

that it should.

/ -26-

the mandate of 42 U.S.C. Section 1988, requiring that the

federal courts, in proceedings to protect and enforce civil

rights, be guided not only by the particular statute in

question; the courts are directed also to draw from other laws

to assure effective remedies for the wrongs involved. The

Supreme Court has invoked this provision specifically to

supply appropriate remedies under Section 1982. See Sullivan

v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229, 239 (1969). And

this Court has said of Section 1988 that "In civil rights

cases, federal courts should use that combination of federal

law, common law and state law as will be best adapted to the

object of the civil rights laws. . ." Brown v. City of

Meridian, 356 F.2d 602, 605 (5th Cir. 1966). Therefore, the

1968 Fair Housing Act should be read harmoniously with Section

1982 to provide a single set of effective remedies under these

statutes, and the attorneys' fees provision of the 1968 Act

should be applied in this case.

/

-27-

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, the case should be remanded

to the District Court with instructions to award reasonable

attorneys' fees covering all proceedings in that court and

on both appeals of this case.

Respectfully submitted,

— <_Jj2c___i gtn-Z, ___

JACK GREENBERG

JEFFRY A. MINTZ

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

REUBEN V. ANDERSON

FRED L. BANKS, JR.

538 1/2 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

1095 Market Street

__San Francisco, California 94103

Attorneys for Appellant

-28-

Ihtpremp (Exmrt of tty luiteft BUUb

October T erm , 1985

L ibrary op Congress, el ni..

Petitioners,

v.

T o m m y S h a w .

OH WRIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OE

APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

J u liu s L eV ohhe Cham bers

Charles S teph en R alston

(Counsel of Record)

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Respondent

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. whether pre-judgment adjustments

to compensate for delay in payment may be

part of the calculation of a reasonable

attorney’s fee and other relief in a

Title VII case brought against the

federal Government under 42

U.S.C. §§ 2000e-16(c) and (d).

2. Whether 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16

constitutes a complete abrogation of

sovereign immunity so that the same full

relief available in a Title VII action

against private and state and local

government employers is also available

against federal government agencies.

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Questions Presented ................ i

Table of Authorities.............. iv

STATUTES INVOLVED .................. 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.............. 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT................ 10

ARGUMENT

I. THERE IS NO BAR TO A DELAY

IN PAYMENT ADJUSTMENT TO AN

ATTORNEYS' FEE AWARD

AGAINST THE UNITED STATES . 12

A ._______ Ad j ustments___ for

Pre-Judgment Delays In

Payment May Be Included In

Awards Pi: Equitable Relief

Against The 'Federal

Government In The Absence

Of Specific Statutory

Authorization.. . . . . . 14

B ._____ The Inclusion of A

Factor To Compensate For

Pre-judgment Delays In

Payment Is A Necessary

Component In "Calculating A

Reasonable Attorney's Fee. . 24

II. SECTION 717 OF THE EQUAL EMPLOY

MENT OPPORTUNITY ACT OF 1972 IS A

COMPLETE ABROGATION OF SOVEREIGN

IMMUNITY IN EMPLOYMENT DISCRIMI

NATION CASES................. 39

A, Congressional Intent Is

Determinative~~0f The Extent

SovereTgn .TmmunTty'.. " ~Is

Waived By A Particular

Statutory Scheme. . . . . . 39

B. Congress Intended To

Waive All Sovereign

limn unity Bars ~To~ The Award

of Complete ReTTef in TitTe

VII Cases............. . 43

Conclusion .................. .. 61

APPENDICES

I. Statutes Involved

II. Calculation of Loss of

Value Through Inflation

III. Memorandum of Attorney

General Griffin B. Bell for

United States Attorneys and

Agency General Counsel

(Aug. 31, 1977)

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases:

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422

U.S. 405 (1975)........ 37

Albrecht v. United States, 329 U.S.

599 (1947)............... 17

Alyeska Pipeline Service v.

Wilderness Soc., 421 U.S.

240 ( 1975)............. 36

Blake v. Califano, 626 F.2d 891

(D.C. Cir. 1980)....... 8

Blum v. Stenson, ___ U.S. ___, 79

L.Ed.2d 891 (1984) . . . . 25, 32

Boston Sand Co. v. United States,

278 U.S. 41 (1928) . . . . . 40

Brooks-Scanlon Corp. v. United

States, 265 U.S. 106 (1924) . 17

Brown v. General Services

Administration, 425 U.S. 820

( 1976).............. 46, 50, 51

Chambers v. United States, 451

F.2d 1045 (Ct. Cl. 1971) . . 49

Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S.

840 ( 1976).............. 44, 46

Chisholm v. United States Postal

Service, 665 F.2d 482

(4th Cir. 1981 ) ....... 33

iv

Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d

880 (1980) . . . . . . 3,4,6,7,24

Franchise Tax Board of California

v. United States Postal

Service, U.S. , 81 L.Ed.

2d 446 ( 1984).......... . 39

Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Company, 424 U.S. 747

(1976) . . . . . . .......... 54

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing

Authority, 690 F.2d 601 •

(7th Cir. 1982)......... 24

General Motors Corp. v. Devex

Corp., 461 U.S. 648

(1983). 15, 16, 17, 34, 35, 36, 37

Gnotta v. United States, 415

F. 2d 1271 (8th Cir. 1969) 50

Graves v. Barnes, 700 F.2d 220

(5th Cir. 1983)......... 24

Griffin v. Carlin, 755 F.2d 1516

(11th Cir. 1985)....... 33

Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S.

424 ( 1983)............ 25

Holly v. Chasen, 639 F.2d 795

(D.C. Cir. 1981), cert.

denied, 454 U.S. 822

(1981) ........ . . . . . 8

Institutionalized Juveniles v.

Secretary of Public Welfare,

758 F.2d 897 (3rd Cir.

1985).................. 24

v

34

James v. Stockham Valves &

Fitting Co., 559 F.2d 310

(5th Cir. 1977) . . . . .

Johnson v. University College of

the University of Alabama,

706 F.2d 1205 (11th Cir.

1983)....................6,

Jorstad v. IDS Realty Trust, 643

F.2d 1305 (8th Cir. 1981) .

Laycock v. Parker, 103 Wis. 161,

79 N.W. 327 (1899) . . . . .

Liggett & M. Tobacco v. United

States, 274 U.S. 215 (1927)

Nagy v. United States Postal

Service, 773 F.2d 1190 (11th

Cir. 1985) ................

Nedd v. United Mine Workers of

America, 488 F. Supp. 1208

(M.D. Pa. 1980)........ 19,

Newman v. Pigoie Park Enterprises,

390 U.S. 490 (1968) . . . . 26,

Parker v. Califano, 561 F.2d 320

(D.C. Cir. 1977) . . . . . .

Parker v. Lewis, 670 F.2d 249

(D.C. Cir. 1982) . . . . . .

Phelps v. United States, 274 U.S.

341 (1927) ................

Ramos v. Lamm, 713 F.2d 546 (10th

Cir. 1983) . . . . . • • • •

24

24

20

1 7

40

20

38

26

5

17

24

vi

Saunders v. Claytor, 629 F.2d 596

(9th Cir. 1980), cert, denied,

450 U.S. 980 (1981) . . . . 9, 33

Seabord Air Line R. Co. v.

United States, 261 U.S. 299

(1923) . . . . . . . . . . 17, 18

Shultz v. Palmer, (No. 85-50) 33

Smith v. Califano, 446 F. Supp.

530 (D.D.C. 1978) . . . . . 53

Smith v. Phillips, 455 U.S. 209

( 1982)........... 10

Standard Oil Co. v. United States,

267 U.S. 76 (1925) . . . . . 41

Teamsters v. United States, 431

U.S. 324 ( 1977).......... 36

United States v. New York Tele

phone Co., 434 U.S. 159 (1977) 10

United States v. North American

Transportation and Trading Co.,

253 U.S. 330 (1920) 18

United States v. Sherman , 98 U.S.

565 (1878) • • 21, 22

United States v. Testan, 424 U.S.

392 (1976) 49

Waite v. United States, 282 U.S.

508 (1931 ) 16, 17, 36

vi i

Statutes, orders, and regulations:

Equal Access to Justice Act . . . . 56

5 U.S.C. § 5596(b)............ 49

5 U.S.C. 7701 ( g ) ( 2 ) . . . . . 53

28 U.S.C. § 2516 . . . . 1, 10, 14, 23

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(q) . . . . . 54, 55

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (k) ..... 44, 57

42 U.S.C. § 200Oe-1 6 .. passim

P.L. 88-352, § 701(b) . . . . . . 48

P.L. 96-481 , § 206 ............ 56

42 Stat. 1590, ch. 192 (5-15-22) . 40

Executive Order 11246 . ........ 48

Executive Order 11478 .......... 48

President's Reorganization Plan

No. 1 of 1978, 43 F.R. 28 71

( 1978).................... 52

5 C.F.R. Part 713 ( 1967)........ 48

5 C.F.R. S 1201.37 .............. 53

29 C.F.R. Part 1613............ 48

29 C.F.R. § 1613.271(c) . . . . . 53

viii

Other Authorities:

"Counsel Fees in Public Interest

Litigation", Report By the

Committee on Legal Assistance,

39 The Record of the Associa

tion of the Bar of the City of

New York 300 (1984) . . . . 25, 29

The Effect of Legal Fees on the

Adeouacv of Representation,

Hearings Before the Sub

committee on Representation

of Citizen Interests of the

Committee on the Judiciary,

United States Senate, 93rd

Cong., 1st Sess. (1973) . . 27

Hearings Before the General

Subcommittee on Labor of

the House Committee on

Education And Labor on

H.R. 1746, March 3, 4, and

18, 1971 . . . . . . . . . 48, 51

Hearings Before the Subcommittee

on Labor of the Senate

Committee on Labor and Public

Welfare, on S. 2515, S.2617,

and H.R. 1746, Oct. 4, 6,

and 7, 1971 .............. 50, 51

Hohenstein, "Subtract Inflation

from Your Income, Prices and

Profits," Legal Economics 35

(ABA Section on Economics of

Law Practice, Summer 1978) 1b

H. Rep. No. 92-238 (92d Cong. 1st

Sess., 1971) .............. 43

ix

Letter from Irving Jaffe, Acting

Assistant Attorney General, to

Senator John V. Tunney, May 6,

1975, 2 CCH Employment Practices

Guide 5327 ( 1976) . . . . . 57

Memorandum of Attorney General

Griffin B. Bell for United

States Attorneys and Agency

General Counsel (Auq. 31,

1977), 2 CCH Employment

Practices Guide 1f 5046

( 1977) .................... 59, 60

Note, "Interest in Judgments

Against the Federal Government:

The Need for Full Compensation,"

91 Yale L.J. 297 (1981) . . . . 20

1 Op. Atty. Gen. 268 (1819) . . . . 21

2 Op. Atty. Gen. 390 (1830) . . . . 22

5 Op. Atty. Gen. 138 (1849) . . . . 22

5 Op. Atty. Gen. 227 (1850) . . . . 22

Ralston, "The Federal Government

as Employer: Problems and

Issues in Enforcing the Anti-

Discrimination Laws," 10 Ga. L.

Rev. 717 ( 1976)............ 57

S. Rep. No. 92-415 (92d Conq. 1st

Sess., 1971)........ 34, 43, 45

H. Rep. No. 94-1558 (94th Conq.

2d Sess. 1976) . . . . 27, 28, 34

x

S. Rep. No. 94-1011 (94th Cong. 2d

Sess. 1976) . . . . . . . . . 27

Schlei & Grossman* Employment

Discrimination Law, (2d Ed.

1983)................... 36, 47

Subcommittee on Labor, Senate

Committee on Labor and Public

Welfare, "Legislative History

of the Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Act

of 1972" . . . 45, 51, 52, 53, 55

United States Dept, of Labor, Bureau

of Labor Statistics, Monthly

Labor Review, May, 1985 . . . 2b

xi

No. 85-54

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1985

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, et aI.,

Petitioners

v.

TOMMY SHAW

On Writ of Certiorari to The

United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

STATUTES INVOLVED

In addition to those in petitioners'

brief, this case involves the following

statutes, the text of which are set out in

the appendix to this Brief:

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(a)-(c)

28 U.S.C. § 2516(a).

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

In general, petitioners' description

of the proceedings below is accurate.

Respondent does wish to emphasize a number

of points regarding the context in which

issue now before the Court arose.

This action began with the filing of

an administrative complaint charging

discrimination in employment against

respondent Tommy Shaw, an employee of the

Library of Congress. After respondent

retained counsel, a settlement of his

claim was negotiated. However, the

agency, on advice from the Comptroller

General, took the position that it could

not agree to an award of back pay. This

ruling, which the district court noted was

caused by the Library's failure to make it

clear that the claim arose under Title

VII, necessitated the filing of the

3

present action. Order and Judgment of the

District Court, Sept. 14, 1979; Pet. App.

p. 59a-60a. The government continued to

argue that an award of back pay was not

possible when a federal employee's claim

of discrimination was settled administra

tively, but the district court ruled for

the respondent and against the governmentl.......

on cross-motions for summary judgment. As

a result of these proceedings, respondent

received a promotion and an appropriate

amount of back pay.

As petitioners note, at issue in this

case now are the fees remaining to be paid

to one of the respondent's attorneys for

work done as far back as 1978. The fee

award was not made by the district court

until 1980 since it decided to await the

en banc decision of the Court of Appeals

of the District of Columbia in Copeland v.

Marshall 9 641 F.2d 880 (1980), which

4

established definitive standards for

awards of fees in Title VII cases in the

District, particularly in cases involving

the federal government. The government

made no objection to delaying the fee

1

disposition until Copeland was announced.

As the district court noted when it

made its award, the government neither

disputed respondent's entitlement to fees

2nor much of the amount to be awarded. * 2

The district court entered its judgment on

the merits on September 14, 1979. In that

order it announced its intention to await

the e_n banc decision in Copeland. See,

Order and Judgment of the District Court,

filed September 14, 1979. Copeland was

announced in September, 1980.

2 The government argued that a proper hourly

rate would be $60. It was not precise,

however, with regard to the number of

hours for which fees should be awarded,

but only suggested that the 103.75 hours

claimed should be reduced "significantly. "

See, Defendant's Memorandum of Points and

Authorities In Opposition to Shalon

Ralph's Motion for Attorney's Fees, pp.

3-5; 7-8. The district court subtracted

only 4.75 hours, for time spent on an

issue on which respondent did not prevail,

and awarded fees for a total of 99 hours.

Pet. App. pp. 63a-64a. The government did

not dispute this result on appeal.

5

Nevertheless, in keeping with its long

standing practice, the government did not

offer to pay that part of the fee that was

undisputed. (Pet. App. p. 68a.) Indeed,

payment of the undisputed amount was not

made until the present appeal was pending

and, then, it was a consequence of a

decision of the court of appeals in

another case, Parker v. Lewis, 670 F.2d

249 (D.C. Cir. 1982), requiring payment of

the undisputed portions of a fee award

pending appeal.3 The Parker rule was

premised on the need to avoid delays in

payroent and conseguent hardships to Title

VII plaintiffs and their attorneys.

The court of appeals did, as recited in

its opinion (Pet. App. p. 6a, n. 24),

order payment of $6,779.50, the undisputed

amount. However, the parties had pre

viously entered into a stipulation for

such payment in the district court based

on Parker v. Lewis, supra. See, Stipula

tion to The Entry of An Order to Enforce

In Part the Judgment Awarding Counsel Fees

and Costs.

6

Copeland squarely held that in

actions against the federal government

delay in payment must he factored in when

calculating a reasonable fee. 641 F.2d at

893. Thus, the district court followed

Copeland and used one of the methods set

out in that decision to arrive at an

appropriate amount for the delay.4 As

petitioners note in their brief, the

correctness of the district court's

calculation is still in dispute, since the

court of appeals remanded for clarifi

cation whether the hourly rate awarded

already included compensation for delay.

Three methods to compensate for delay are:

(1) the use of hourly rates current at the

time the award is made; (2) adjusting the

rates by year by an appropriate amount so

as to adjust for inflation; (3) adjusting

the lodestar amount by an appropriate

factor. See Johnson v. University College

of the University of Alabama, 706 F.2d

1205, 1210-1 1 (1 1th CTT. T983). The

district court used the third method.

7

In addition to the en banc decision in

Copeland, panels of the court of appeals

had held that fees in Title VII actions

against federal agencies fees should be

adjusted for delay in payment. Thus, when

the present case arrived in the court of

appeals, there was already an e_n banc

decision and at least three panel deci

sions of that court that squarely held

that the district court was correct in

including a delay factor. Counsel for

respondent in the court of appeals (who

are also counsel here) not surprisingly

relied on the clear law of the circuit to

support the judgment of the district

court. ̂ Since there was no need to go

beyond the settled law of the circuit,

they did not argue at length the issues of

The court below noted "the seemingly clear

applicability of these precedents" but

decided not to rest "on stare decisis

alone." Pet. App. p. 9a.

5

8

waiver of sovereign immunity and other

matters presented now. Thus, the argument

made was essentially that the calculation

of a reasonable attorney's fee necessarily

included compensation for delay in

payment, an argument accepted even by the

dissenting judge below.

Moreover, panel decisions of the court

of appeals had also held that cost of

living adjustments were not available on

6backpay awards against the government

and that interest qua interest could not

7be assessed on a fee award. Again, since

the state of the law in the circuit

established the correctness of the

district court's decision, counsel for

Blake v. Califano, 626 F.2d 891 (D.C. Cir.

1980) .

Holly v. Chasen, 639 F.2d 795 (D.C. Cir.

1981) , cert, denied, 454 U.S. 822 (1981).

7

9

respondent (appellee there) did not feel

it either necessary or desirable to raise

8these other issues.

If the government's suggestion to the

court of appeals for rehearing en banc in

the present case had been granted,

respondent would, of course, have raised

and relied upon all of the arguments made

herein to support the judgment of the

district court. Thus, the government's

attempt (Pet. Brief, p. 18) to make some

thing out of counsel's decision not to

raise these questions before a panel of

the court below when such issues were

decided by its earlier decisions is

As we have already noted in our Brief in

Opposition to the Petition for Writ of

Certiorari, we believe that the decisions

of lower courts holding that back pay

awards cannot be adjusted for inflation in

cases against the federal government are

incorrect. See infra at pp.3 5^3 8 . Indeed,

that precise issue was presented to this

Court in Saunders v. Claytor, 629 F.2d 596

(9th Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 450 U.S.

980 ( 1981), but this Court has not

resolved the issue to date.

10

without substance. Of course, respondent

may rely here on any ground in support of

the judgment below. United States v. New

York Telephone Co., 434 U.S. 159, 166, n.

8 (1977); Smith v. Phillips, 455 U.S. 209,

215, n. 6 (1982).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

A. There is no sovereign immunity or

statutory bar to awards of pre-judgment

interest, or its equivalent, against the

United States where it is necessary to

provide complete equitable relief. The

cases the government relies on, as well as

28 U.S.C, § 2516, involve post-j udgment

interest, the purpose of which is entirely

different. Decisions of this Court make

the distinction clear and hold that

pre-judgment interest may be made in the

absence of specific statutory authority.

B. In calculating a reasonable

attorneys' fee, factoring in amounts to

compensate for delays in payment is

essential. Without such an adjustment, a

prevailing plaintiff's attorney will in

fact be awarded less than a market rate.

The result will be that attorneys will be

discouraged from representing federal

employees who have Title VII claims.

Therefore, pre-judgment interest or its

equivalent is appropriate in awards of

fees against the United States.

II.

A. The extent of a waiver of sov

ereign immunity is a matter of Congres

sional intent. Whether interest on awards

against the government is permissible must

be determined from the purpose of the

particular statutory scheme.

- 11 -

12

B. Both the language of 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-16 and its legislative history

make it clear that Congress intended to

remove all sovereign immunity bars to the

granting of full relief to federal

employees who have equal employment

claims. The statute itself explicitly

provides that attorneys' fees are to be

awarded on the same basis as against "a

private person."

ARGUMENT

I.

THERE IS NO BAR TO A DELAY IN PAYMENT

ADJUSTMENT TO AN ATTORNEYS' FEE AWARD

AGAINST THE UNITED STATES

This case, in the government's view,

involves no more than whether the word

"interest" can be found somewhere in the

provisions of Title VII that apply to the

United States. We will demonstrate that:

13

1 . A long line of decisions of this

Court establishes that, even in the

absence of specific statutory authoriza

tion, pre-j udgment adjustments that

compensate for delay in payment and/or

deprivation of the use of funds — whether

denominated "pre-j udgment interest" or

otherwise -- are available against the

government to provide full compensation as

part of equitable relief.

2. The inclusion of a delay in

payment factor, as in this case, is a

necessary component of a reasonable

attorney's fee. Since the adjustment is

necessary to provide full compensation, it

is available here as a matter of leg is-

lative intent, consistent with the Court' s

precedents.

3. Alternatively, there is no

sovereign immunity bar to an award of

interest against the government in a Title

14

VII action because 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 is

a complete abrogation of sovereign

immunity. Congress' clear intent was to

ensure that employees of the United States

will enjoy the same scope of protection

from employment discrimination as do all

other employees. Therefore, Title VII jjs

a statute that authorizes interest as part

of complete relief.

A. Adjustments For Pre-judgment Delays

In_____Payment May Be Included In

Awards Of Equitable Relief Against

The Federal Government In The Absence

of Specific Statutory Authority.

The petitioners argue that decisions

of this Court, as codified in 28 U.S.C.

§ 2516, stand as an absolute bar to any

inclusion of a delay in payment factor in

calculating the value of a fee award

because the word "interest" does not

appear in Title VII. However, a close

examination of the cases cited by the

15

government demonstrates that they do not

support this proposition. Rather,

precisely the opposite is true? the

government has been led into a fatal error

by its failure to distinguish between the

nature and purpose of pre-judgment

interest, which is involved here, and

post-judgment interest, which is not.

In General Motors Corp. v. Devex

Corp. , 461 U.S. 648 (1983), the Court

explained that, in a patent infringement

case, an award of prejudgment interest

from the time that the royalty payments

would have been received to the time of

the judgment, "merely serves to make the

patent owner whole, since his damages

consist not only of the value of the

royalty payments but also of the forgone

use of the money between the time of

infringement and the date of the judg —

16

ment." Therefore, prejudgment interest

should ordinarily be awarded. 461 U.S. at

655-56.

The Court went on:

This very principle was the

basis of the decision in Waite

v. United States, 282 U.S. 508

(1931), which involved a patent

infringement suit against the

United States. The patent owner

had been awarded unliquidated

damages in the form of lost

profits, but had been denied an

award of prejudgment interest.

This Court held that an award of

prejudgment interest to the

patent owner was necessary to

ensure "complete justice as

between the plaintiff and the

United States," id., at 509,

even though the statute govern

ing such suits did not expressly

provide for interest.

461 U.S. at 656 (emphasis added). In

Waite .itself, Justice Holmes noted that

the statute at issue granted "'recovery of

[the plaintiff's] reasonable and entire

compensation for such use.' We are of

17

opinion that interest should be allowed in

order to make the compensation 'entire'".

282 U.S. at 509.9

Waite cites and relies upon a series

of decisions in eminent domain actions

holding that the Fifth Amendment's "just

compensation" clause includes compensation

for delay between the time of the determi

nation of market value of the property and

when the award is made. Seaboard Air Line

R. Co. v. United States, 261 U.S. 299

(1923); Brooks-Scanlon Corp. v. United

States, 265 U.S. 106, 126 (1924); Liggett

& M. Tobacco Co. v. United States, 274

U.S. 215 (1927); Phelps v. United States,

274 U.S. 341 (1927). See also Albrecht v.

United States, 329 U.S. 599 (1947), and