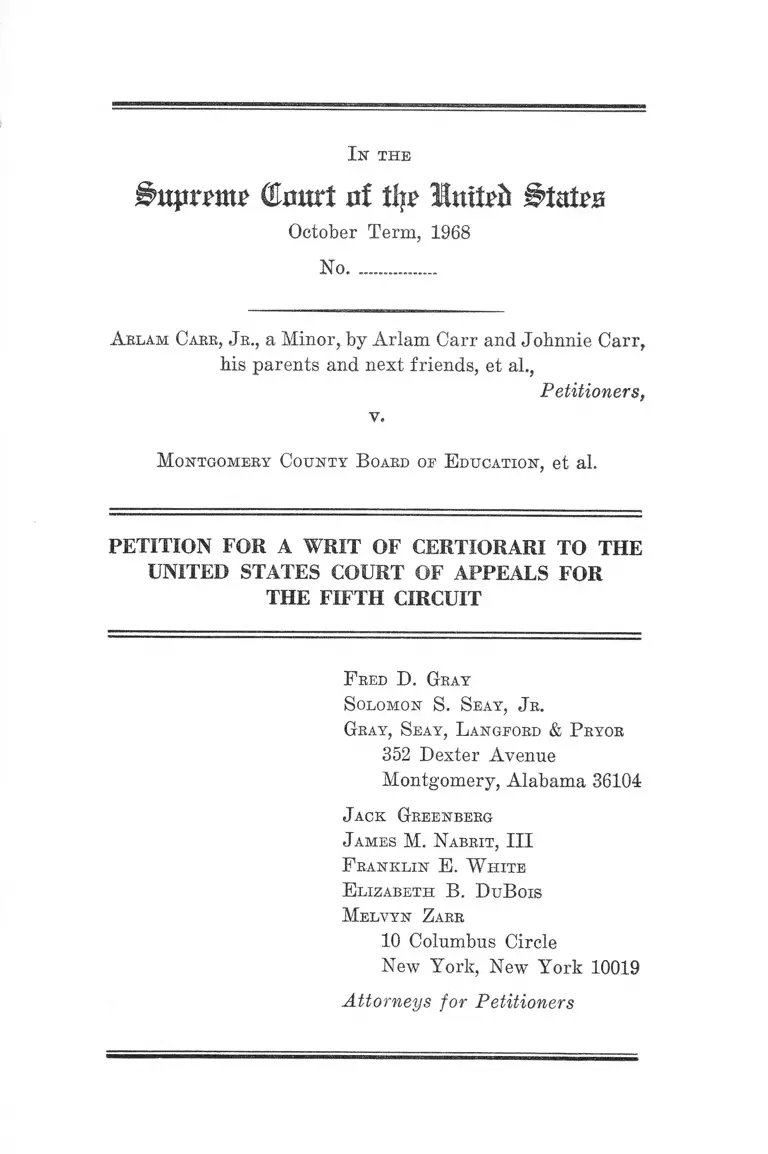

Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education Petition fro a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education Petition fro a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1968. 20b2b1e8-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9db3bcbb-04f6-4a67-a135-030aff74467a/carr-v-montgomery-county-board-of-education-petition-fro-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Bnpveme (Hemet in the Imfrfc States

October Term, 1968

No......... .......

A beam Cabb, Jr., a Minor,, by Arlam Carr and Johnnie Carr,

Ms parents and nest friends, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

M ontgomery County B oard on E ducation, et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

F red D. Gray

Solomon S. Seay, J r.

Gray, Seay, L angford & P ryor

352 Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

F ranklin E. W hite

E lizabeth B. D uB ois

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below .................................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ............ 2

Question Presented............................ 3

Constitutional Provisions Involved................................. 3

Statement .................................. -....................................... 4

1. Introduction .......................................................... 4

2. Proceedings during 1964 ............... 4

3. Proceedings during 1965 ..................................... 5

4. Proceedings during 1966 ..................................... 6

5. Proceedings during 1967 ..................................... 7

6. Proceedings during 1968 ..................................... 11

a. In the District Court..................................... 11

b. Action of the Court of Appeals .................. 15

Reasons for Granting the Writ ..................................... 16

Conclusion................................................................................. 25

T able op Cases

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103 ......................6,18

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 ..........5,16,17

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 ............... 16

Coppedge v. Franklin County Board of Education,

273 F. Supp. 289 (E.D. N.C. 1967), aff’d 294 F.2d

410 (4th Cir. 1968) ............ 23

IX

PAGE

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 364 F.2d 896 (5th Cir. 1966) ...................... 7

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 244 F. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965), ail’d

375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 387

U.S. 931 ....................................................................... 23,24

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 ............................................................16,17, 22

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218............................. 18

Kelley v. Altheimer School District, 378 F.2d 483

(8th Cir. 1967) .............................................................. 23

Kier v. County School Board of Augusta County,

249 F. Supp. 239 (W.D. Ya. 1966) .......................... 23

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 267 F.

Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala. 1967), aff’d sub nom. Wallace

v. United States, 389 U.S. 215 (1967) .............. 7, 8,19, 21

Raney v. Board of Education of the Gould School

District, 391 U.S. 443 ................................................ 24

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 .........................................6,18

United States v. Board of Education of City of Bes

semer, 396 F.2d 44 (5th Cir. 1968) ........................ 17

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion, 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), aff’d en banc, 380'

F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 389 U.S.

840 ...............................................................................7,8,24

United States v. School District 151 of Cook County,

Illinois, 286 F. Supp. 786 (N.D. 111. 1968), aff’d,

------- F.2d ------ (7th Cir., Dec. 17, 1968), 37 U.S.L.

Week 2371 ............. 23

Wallace v. United States, 389 U.S. 215 .............. 8,16,19, 22

Wanner v. County School Board of Arlington County,

Va., 357 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1966) .......................... . 24

Yarbrough v. Hulbert-West Memphis School District,

380 F.2d 962 (8th Cir. 1967) ..................................... 23

In the

Bnpvm? (U m iri n f % I m t e f c S t a t e s

October Term, 1968

No.................

A blam Caeb, Jr., a Minor, by Arlam Carr and Johnnie Carr,

his parents and nest friends, et ah,

Petitioners,

v.

M ontgomery County B oard of E ducation, et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit, entered in the above-entitled case on

August 1, 1968, and rehearing denied on November 1, 1968.1

Opinions Below

The opinion and order of the district court of February

24,1968 (R. 404), is reported at 289 F. Supp. 647 (Appendix

A )2 and the supplemental order entered March 2, 1968

(R. 430), is at 289 F. Supp. 657 (Appendix B). Another

1 A petition for certiorari to review the same judgment has been

filed by the United States in this Court with the record herein sub

nom. United States v. Montgomery County Board of Education,

No. 798, Oct. Term, 1968.

2 Citations to the Appendix refer to the Appendices to the Peti

tion filed in this Court by the United States in No. 798, Oct. Term,

1968.

2

supplemental order of March 2,1968 (R. 428), is unreported

(Appendix C). The majority opinion of August 1, 1968,

by the panel of the Court of Appeals (by Circuit Judge

Gewin, with District Judge Elliott concurring) is reported

at 400 F.2d 1 (Appendix D). The dissenting opinion of

October 21, 1968, by Judge Thornberry is reported at 402

F.2d 782 (Appendix E). The order of the Court of Appeals

of November 1, 1968, denying rehearing and rehearing

en banc by an equally divided court, is at 402 F.2d 784

(Appendix F). The opinion dissenting from the denial of

rehearing en banc (by Chief Judge Brown, with the con

currence of Judges Wisdom, Thornberry, Goldberg and

Simpson) is at 402 F.2d 784 (Appendix F). Judge Dyer

also dissented from the denial of rehearing en banc without

opinion at 402 F.2d 787.

Prior reported opinions and orders of the district court

at earlier stages of the case are reported as follows: (a)

July 31, 1964, 232 F. Supp. 705, R. 98; (b) May 18, 1965, 10

Race Rel. L. Rep. 582, R. 191; (c) March 22, 1966, 253 F.

Supp. 306, R. 274; (d) August 18, 1966,11 Race Rel. L. Rep.

1716, R. 285; (e) June 1, 1967, 12 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1200,

R. 364.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

August 1, 1968 (Appendix D ) ; rehearing was denied

November 1, 1968 (Appendix F). The jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. Section 1254(1).

3

Question Presented

Whether in a school district segregated by law into a

dual system of separate white and Negro schools, where

only slight desegregation has been achieved despite litiga

tion begun in 1964, and a trial court determined that to

“pass tokenism” the faculty desegregation goal should be

to distribute teachers so that all schools will have about the

same proportion of white and Negro teachers, it was error

for the Court of Appeals to :

(a) strike down the trial court’s numerical ratios as

the proper long-term faculty integration objective and leave

the goal undefined;

(b) refuse to set a target date or timetable for full fac

ulty desegregation;

(c) dilute the trial judge’s interim minimum goals by

adding qualifying phrases which enable the school board

to excuse noncompliance;

(d) reject the petitioners’ request that all faculties in

new schools be fully desegregated when they are opened.

Constitutional Provisions Involved

This case involves the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

4

Statement

1. Introduction.

This is a public school desegregation suit presenting is

sues relating to the obligation of the Montgomery County,

Alabama, public school system to desegregate school facul

ties. The school board appealed seeking reversal of a

desegregation order entered February 24, 1968, and

amended March 2, 1968, by District Judge Frank M. John

son, Jr. By a vote of 2-1, a panel of the Court of Appeals

(Circuit Judge Gewin and District Judge Elliott) modified

the order and eliminated certain provisions relating to

faculty desegregation. Circuit Judge Thornberry dissented

from the modifications of the faculty integration order. A

petition for rehearing en banc was denied by an equally

divided vote of 6-6, with one Judge not participating due to

illness.

In this petition, the Negro pupils and parents wdio com

menced the litigation in 1964 seek to reinstate the district

court order on the faculty question. Another petition for

certiorari seeking that same relief has been filed by the

United States which has participated in the case throughout

by order of the District Court. See United States v. Mont

gomery County Board of Education, docketed December 4,

1968, as No. 798, October Term, 1968.

2. Proceedings During 1964.

The complaint (R. 1-8), filed by a group of Negro pupils

and parents May 11, 1964, alleged that the Montgomery

County, Alabama school system was operated on a racially

segregated basis. It was alleged that Negro students were

assigned to schools with only Negro students and faculties

(R. 4). The relief sought included an injunction against

segregated faculty assignments (R. 7).

5

Ail opinion by the district court July 31, 1964, noted that

the system, which embraces the City of Montgomery and

surrounding rural areas, served about 25,000 white children

and 15,000 Negro children (E. 100). The judge found there

was “ a dual school system based upon race and color” and

that defendants “ operate one set of schools to be attended

exclusively by Negro students and one set of schools to be

attended exclusively by white students” (R. 100). The judge

wrote that: “ The evidence further reflects that the teachers

are assigned according to race; Negro teachers are assigned

only to schools attended by Negro students and white

teachers are assigned only to schools attended by white

students” (E. 100). The court observed: “Even the sub

stitute teachers’ list and attendance records reflect these

distinctions based upon race” (R. 101). Finding that ten

years had elapsed since Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483, without any action to desegregate the schools, the

court ordered that desegregation begin in September 1964

in grades 1,10,11 and 12. But, the court made no order with

respect to faculty integration. Thereafter, 29 Negro pupils

sought transfers to white schools in September 1964. The

school board, using the Alabama School Placement Law,

denied the requests of 21 and admitted the remaining 8

Negroes to white schools (R. 112). The court refused to

order the admission of the rejected Negro transfer appli

cants (R. 148).

3. Proceedings During 1965.

On January 15, 1965, the school board filed a proposed

desegregation plan as required by the judge (R. 155). The

proposed plan made no mention of faculty desegregation

and plaintiffs objected on that ground among others

(R. 169). On May 18, 1965, the trial judge approved the

proposed plan with amendments to require desegregation

6

in grades 1, 2, 9, 10, 11 and 12 in September 1965 (R. 191).

Again the court entered no order with respect to faculty

desegregation, but did order that a plan for “complete elimi

nation of the biracial school system within a reasonable

time” be filed in January 1966.3

In August 1965 the school board reported that it had ac

cepted 18 of 49 Negro applicants to white schools (R. 195).

The plaintiffs again objected to the denial of transfer re

quests, but the court upheld the board’s denials of all ex

cept 6 applicants who were ordered admitted (R. 232-234).

4. Proceedings During 1966.

On January 14, 1966, the board filed another desegrega

tion plan making no mention of faculty desegregation

(R. 250). Again plaintiffs objected to the lack of faculty

desegregation (R. 265) and this time the United States

made a similar objection (R. 261). Plaintiffs specifically

relied on this Court’s faculty desegregation decisions in

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103 (Nov. 1965) and

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (Dec. 1965).

On March 22, 1966, the court entered another desegrega

tion order (R. 274), this time requiring a “ freedom of

choice” plan generally following guidelines of the Depart

ment of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) (R. 270).

This order required desegregation of all grades except 5

3 In announcing his ruling from the Bench, May 5, 1965, Judge

Johnson said: “ The defendants should be ordered to file their plan

for completion of the desegregated system, including abolition of

the dual school or biracial school system, which of course still exists.

I am not naive enough to believe that desegregation of certain

grades by transfer, such as we are doing here, is full compliance

with what the law eventually envisions and requires, but I recog

nize that it is a transition period, and I think that this is reasonable

for the facts in this case and the circumstances existing in this

particular school district at this time” (R. 444).

7

and 6 in September 1966, and for those grades to be de

segregated in September 1967. It directed the closing of

several small, inadequate all-Negro schools.

For the first time, the March 22,1966, order also required

faculty desegregation. It ruled that race and color was not

to be a factor in faculty assignments except to eliminate

the effects of past discrimination. It ordered that assign

ments be made so that each school’s “faculty . . . is not com

posed of members of one race.” Job applicants were or

dered to be informed of the new policy, and the administra

tion was ordered to encourage staff transfers to promote

integration. The school administration, in response, made

tentative arrangements to place 4 white teachers in black

schools and 4 black teachers in white schools (R. 455). How

ever, after these plans were made, the trial judge, on his

own motion on August 18, 1966, rescinded the requirement

and postponed faculty integration another year (R. 285).

The judge relied on a Fifth Circuit opinion which ordered

faculty integration for Mobile, Alabama to begin in 1967.4

5. Proceedings During 1967.

On April 11,1967, plaintiffs moved for modification of the

desegregation plan to conform to the circuit-wide require

ments of United States v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion, 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), aff’d en banc, 380 F.2d

385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 840 (1967). Judge

Johnson ordered the board to show cause why it should not

adopt a plan to conform to Jefferson, supra, and to the plan

ordered by a three-judge court for 99 Alabama counties in

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 267 F. Supp, 458

4 Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile, 364 F.2d

896 (5th Cir., 1966).

8

(M.D. Ala. 1967), aff’d sub nom. Wallace v. United States,

389 U.S. 215 (1967).5

On June 1, 1967, the court entered an order conformable

to Jefferson, supra, and Lee, supra (R. 364). The provision

for faculty desegregation, which is quoted in full in the

footnote below,6 adopted the objective that “the pattern of

5 The Lee opinion recites in detail the background of official

resistance by the Governor of Alabama and state education officials

to prevent public school desegregation in the State. The three-judge

court found that the desegregation efforts of Negroes in Alabama

“have met the relentless opposition of these defendant state officials”

(267 F. Supp. at 465; R. 318), The opinion recites in detail one

series of episodes in August 1966 when the State Superintendent

of Education and Governor George C. Wallace worked to prevent

faculty desegregation in Tuscaloosa County (267 F. Supp. at 469).

The court found that these “state officials also made it clear that

similar measures would be taken in other communities if Negro

teachers were assigned to teach white students” (id.).

6 “VI

“ F a c u l t y a n d S t a f f

“A. Faculty Employment and Assignment. Race or color

will not be a factor in the hiring, assignment, reassignment,

promotion, demotion or dismissal of teachers and other pro

fessional staff members, including student teachers, except that

race will be taken into account for the purpose of counteracting

or correcting the effect of the past segregated assignment of

teachers in the dual system. Teachers, principals, and staff

members will be assigned to schools so that the faculty and

staff is not composed exclusively of members of one race.

Wherever possible, teachers will be assigned so that more than

one teacher of the minority race (white or Negro) will be on

a desegregated faculty. The school board will take positive and

affirmative steps to accomplish the desegregation of its school

faculties, including substantial desegregation of faculties in

as many of the schools as possible for the 1967-68 school year,

notwithstanding that teacher contracts for the 1967-68 or

1968-69 school year have already been signed and approved.

The objective of the school system is that the pattern of teacher

assignment to any particular school shall not be identifiable

as tailored for a heavy concentration of either Negro or white

pupils in the school. The school system will accomplish faculty

desegregation in a manner whereby the abilities, experience,

specialties, and other qualifications of both white and Negro

teachers in the system will be, insofar as administratively

9

teacher assignment to any particular school shall not he

identifiable as tailored for a heavy concentration of either

Negro or white pupils in the school” (E. 370).

On August 17, 1967, the United States filed a motion to

require further faculty desegregation in view of the fact

that the school board planned to assign only 5 white teach

ers of 804 to two Negro high schools and 5 Negro teachers

out of 554 to two predominantly white high schools (E. 376).

The plaintiffs joined in the motion (E. 379), and the court

held an evidentiary hearing September 5, 1967.

feasible, distributed evenly among the various schools of the

system.

“B. Dismissals. Teachers and other professional staff mem

bers will not be discriminatorily assigned, dismissed, demoted,

or passed over for retention, promotion, or rehiring on the

ground of race or color. In any instance where one or more

teachers or other professional staff members are to be displaced

as a result of desegregation, no staff vacancy in the school

system will be filled through recruitment from outside the

system unless no such displaced staff member is qualified to

fill the vacancy. If, as a result of desegregation, there is to

be a reduction in the total professional staff of the school sys

tem, the qualifications of all staff members in the system will

be evaluated in selecting the staff member to be released with

out consideration of race or color. A report containing any

such proposed dismissals, and the reasons therefor, shall be

filed with the Court, and copies served upon opposing counsel

within five (5) days after such dismissal, demotion, etc., is

proposed.

“ C. Notice to New Staff Members. In the recruitment and

employment of teachers and other professional personnel, all

applicants or other prospective employees will be informed that

Montgomery County operates a racially desegregated school

system and that members of its staff are subject to assignment

in the best interest of the system and without regard to the

race or color of the particular employee.

“D. Encouragement of Voluntary Faculty Tranfers. The

Superintendent of Schools and his staff wall take affirmative

steps to solicit and encourage teachers presently employed to

accept transfers to schools in which the majority of the faculty

members are of a race different from that of the teacher to be

transferred.”

10

School Superintendent McKee testified that it was de

cided to limit faculty desegregation at the beginning to

high schools because he anticipated less objection since one

teacher would not have the pupils for as much of the day in

high school classes (R. 459-460). He also decided to inte

grate faculties only in schools within the city limits because

of the need for close supervision and special protection

which was more difficult in sparsely settled areas of the

county (R. 461). The superintendent said he was having

some difficulty finding white teachers who would agree to

assignments in Negro schools, although there was no dif

ficulty finding Negroes willing to teach in white schools

(R. 466, 469, 470). The superintendent had engaged 12 or

13 white teachers for Negro schools, but only 5 of them actu

ally finally accepted the assignment (R. 468). All 5 Negroes

initially picked for white schools actually undertook such

assignments (R. 468-469). Mr. McKee indicated that he

had not assigned more Negro teachers, even though they

were available, because he had not been able to get more

whites to volunteer for assignments to Negro schools

(R. 469), and he wanted to keep the number of Negroes

and whites in balance (R. 481). The annual faculty turn

over or replacement rate in Montgomery is about 10% of

the total staff (R. 478).

At the end of the hearing the court heard arguments, but

took no action to make a ruling to affect the 1967-68 school

year. The matter was kept under advisement without ac

tion by the court. During argument the judge made it

plain that he had little “ sympathy” with the request for

relief at that time (R. 484).

11

6. Proceedings During 1968.

a. In the District Court. On February 1, 1968, the board

filed a further pleading asserting it had 32 faculty em

ployees teaching in schools predominantly of the other race,

and that it planned further efforts for the coming year.

The United States filed a motion (E. 389), joined by the

private plaintiffs (R. 394), seeking further relief on the

faculty question as well as relief on several other issues

affecting desegregation. The court heard evidence Febru

ary 9, 1968 (E. 495-694).

Superintendent McKee and Associate Superintendent

Garrett testified that they had decided that in September

1968 they would assign Negro teachers to all of the white

schools at once in “ one fell swoop” (R. 556, 579). Mr. Gar

rett described the plans for faculty desegregation in the

following testimony:

Q. How many teachers do you estimate you will have

in minority situations this coming year? A. Well, we

have about thirty-five now. We are going to attempt—

our plan is to try to get at least one into every junior

high and every elementary, and then start—once we

accomplish that, start around with the second one and

the third one and so on, rather than to have three in

one school and none in another.

Q. Well based on your— A. Roughly speaking, a

minimum or—with thirty-five already there, we have

fifty schools or thereabouts; I would say about a hun

dred or better.

Q. Based on your— A. I think that is practical; I

believe we can accomplish that (R. 584).

# * *

The Court: My understanding, now, you are going

to have this next year teachers of the minority race in

every school in your system?

12

Witness: As far as humanly possible.

The Court: And how many do you expect to have in

your—in your elementary schools, a minimum per

school?

Witness: Two, at least.

The Court: And how many in your junior high, your

minimum!

Witness: Two; maybe more.

The Court: All right.

Witness: Depending on what we come—

The Court: Now, let’s go to percentages; what per

centage do you expect to have in your high schools ?

Witness: I just don’t know. We haven’t actually dis

cussed that up to this point. I—I couldn’t say.

The Court: Well, your race—your student popula

tion is sixty-forty!

Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: Ultimately, that will be your optimum

if you are going to eliminate the racial characteristics

of your school through faculty—

Witness: (Nodded to indicate affirmative reply.)

The Court: —wouldn’t it? It would have to be.

(R. 598-599.)

# # #

Q. Mr. Garrett, I believe you testified when I was

examining you that you were going to have at least—

at least one in each school, or am I wrong on that?

A. I said we would try to start with one in every ele

mentary school and then come back around with two,

and if we were successful, maybe three; I don’t have

any preconceived notion about maximums, but I would

rather have these distributed rather than to have three,

say, in one school and none in another (R. 600).

13

In a memorandum opinion filed February 24, 1968, the

court made findings that there were still about 15,000 Negro

children and 25,000 white children in the system; that only

550 Negro children were attending traditionally white

schools and no whites were in the Negro schools under the

freedom of choice plan; that 32 classroom teachers were

teaching pupils in schools predominantly of the opposite

race; that the system employed about 550 Negro teachers

and 815 white teachers; that most faculty desegregation

was in the high schools and there was little, if any, faculty

desegregation in the county’s rural schools (R. 406). The

court also noted that the vast majority of teachers newly

hired after the June 1, 1967, faculty desegregation order,

were still assigned to schools where their race was in the

majority; that no Negro has yet been a sustitute in a white

school; that during a semester where white substitute

teachers were employed 2,000 times, only 33 white sub

stitutes were employed in Negro schools; that there was

“no adequate program for the assignment of student

teachers on a desegregated basis” ; and that there was no

faculty desegregation in night schools (R. 406-407). The

court concluded: “The evidence does not reflect any real

administrative problems involved in immediately desegre

gating the substitute teachers, the student teachers, the

night school faculties, and in the evolvement of a really

legally adequate program for the substantial desegregation

of the faculties of all schools in the system commencing with

the school year 1968-69” (R. 407).

Judge Johnson, during the hearing, in a colloquy with

Superintendent McKee, expressed the position, “I have gone

along with this transition business for a good long while,

but we have passed the transition period” (R. 544). Finding

that the board had “ failed to discharge the affirmative duty

. . . to eliminate the . . . dual school system,” the court held

14

it was “necessary and entirely appropriate to establish now

more specific requirements governing minimum amounts

of progress in the future . . . ” (R. 409).

The order of February 24, 1968 (R. 413-414), as amended

(R. 429), supplemented the desegregation plan approved

June 1, 1967. The order, which is quoted below,7 defined the

objective of eliminating the racial identifiability of school

faculties as requiring the assignment of faculty such that

the ratio of Negro to white faculty members in each

school would be substantially the same throughout the

“ F a c u l t y a n d S t a f f

“ A. Statement of Objective. In achieving the objective of

the school system, that the pattern of teacher assignments to

any particular school shall not be identifiable as tailored for

a heavy concentration of either Negro or white pupils in the

school, the school board will be guided by the ratio of Negro

to white faculty members in the school system as a whole.

“ The school board will accomplish faculty desegregation by

hiring and assigning faculty members so that in each school

the ratio of white to Negro faculty members is substantially

the same as it is throughout the system. At present, the ratio

is approximately 3 to 2. This will be accomplished in accord

ance with the schedule set out below.

“B. Schedule for Faculty Desegregation. 1. 1968-69. At

every school with fewer than 12 teachers, the board will have

at least one full-time teacher whose race is different from the

race of the majority of the faculty and staff members at the

school.

“At every school with 12 or more teachers, the race of at

least one of every six faculty and staff members will be dif

ferent from the race of the majority of the faculty and staff

members at the school. This Court will reserve, for the time

being, other specific faculty and staff desegregation require

ments for future years.

“ C. Means of Accomplishment. I f the school board is un

able to achieve faculty desegregation by inducing voluntary

transfers or by filing vacancies, then it will do so by the as

signment and transfer of teachers from one school to another.

“D. Substitute Teachers. Commencing in September, 1968,

with the 1968-69 school year, the ratio of the number of days

taught by white substitute teachers to the number of days

15

system. For the year 1968-69 the court ordered at least

one minority race (white or black) teacher in each school

with less than 12 teachers, and in larger schools at least

one minority race teacher of every six teachers. The

court reserved judgment on detailed requirements for fu

ture years. The court also ordered that substitute teachers,

student teachers, and night school teachers should be as

signed so that there was substantially the same racial ratio

in each school.

On the school board’s application for a stay pending ap

peal, a part of the faculty desegregation order was stayed

by Judge Johnson.

b. Action of the Court of Appeals. On August 1, 1968,

the Court of Appeals, by a divided vote, modified the faculty

desegregation order.8 The court struck from the decree all

numerical ratios except the interim 1968-69 goal—a five-to-

one ratio in large schools and a more liberal ratio in

smaller schools—which was modified to read “substantially

or approximately five to one” (emphasis added). The court

taught by Negro substitute teachers at each school during each

semester will be substantially the same as the ratio of white

substitute teachers to Negro substitute teachers on the list of

substitute teachers at the beginning of the semester.

“ Commencing with the 1968-69 school year, the board will

not use an individual as a substitute teacher in the Mont

gomery Public Schools if he will consent to substitute only at

predominantly white schools or only at predominantly Negro

schools.

“ E. Student Teachers. Commencing in September, 1968,

with the 1968-69 school year, the ratio of white to Negro

student teachers each semester in each school that uses student

teachers will be substantially the same as the ratio of white

and Negro student teachers throughout the system.

“F. Night Schools. Commencing June 1, 1968, the ratio of

white to Negro faculty members at each night school will be

substantially the same as the ratio of white to Negro faculty

members throughout the night-school program.”

8 Trial court rulings pertaining to special efforts to desegregate

a new high school were affirmed on appeal.

16

also rejected the plaintiffs’ argument that the trial court

should have set a target date for full integration and should

have required immediate total desegregation of faculties

in several new schools to be opened in 1968.

Judge Thornberry dissented,, finding no basis in the

record or the prior decisions for modifying the trial judge’s

experiment in establishing numerical ratios for faculty de

segregation. Chief Judge Brown’s dissent from the denial

of rehearing en banc (joined in by Judges Wisdom, Thorn-

berry, Goldberg and Simpson) argued that there was a

need for specfic numerical targets for faculty desegre

gation plans to define the goal of schools unidentifiable

as to race, as well as a need for specific target dates

for compliance.

Reasons For Granting the Writ

This case merits plenary review on certiorari because it

involves issues of considerable practical importance to the

future of school desegregation, about which there is both a

conflict among the circuits and an equal division among

twelve active judges of the Fifth Circuit, The ruling be

low also conflicts with this Court’s decisions in Wallace v.

United States, 389 U.S. 215, and Green v. County School

Board, 391 U.S. 430.

The case involves the powers of a district court in super

vising the transition of a dual, segregated school system

into a racially non-discriminatory system as required by

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (Brown I) ■

349 U.S. 294 (Brown II). The court below set aside an

order of the trial court which defines the long range goal

for faculty desegregation to be to seek, over an indetermi

nate period of time, approximately the same proportion of

Negro and white teachers in all schools of the system. By

17

striking the “numerical ratios” from the trial court’s order,

the panel majority below rejected this goal and left the

faculty desegregation objective so vaguely defined as to

impair the ability of district courts to assure substantial

progress.

In addition to altering the long-term goal, the court below

made three subsidiary rulings to which petitioners also

object. One was the failure to set any target date or time

table for full faculty desegregation in Montgomery. An

other panel of the Fifth Circuit had set a so-called “ C”

(for “ compliance” ) day for full faculty desegregation by

September 1970. United States v. Board of Education of

the City of Bessemer, Alabama, 396 F.2d 44, 52 (5th Cir.

1968). Also the court diluted the trial judge’s specific mini

mum goals for 1968 by adding the qualifying phrases “ap

proximately” and “ substantially.” Finally, the court below

refused the petitioners’ request that the trial court be di

rected to require full faculty desegregation immediately in

all newly established schools at the time faculties are first

hired and assigned.

The issues should be viewed in the practical context of

Montgomery County, Alabama. When this law suit was

filed in May 1964, ten years after Brown I, the public schools

were still totally segregated. No progress had been made

voluntarily. In Montgomery, as was true in a Virginia

county brought before this Court last term: “Racial identi

fication of the system’s schools was complete, extending not

just to the composition of student bodies . . . but to every

facet of school operations—faculty, staff, transportation,

extracurricular activities and facilities.” Green v. County

School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 435. As stated in Green, supra,

at 436, “ [t]he transition to a unitary, nonraeial system of

public education was and is the ultimate end to be brought

about . . . .” In Montgomery County, Alabama it became the

18

task of District Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr. to supervise

that transition.

The very same month this case was filed, this Court de

clared in Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218, 234, that

“the time for mere ‘deliberate speed’ has run out . . . .”

Yet, for four more years the District Judge patiently per

mitted the respondent school board to delay desegregation

with a variety of transitional devices until he finally decided

“We have reached the point where we must pass ‘token

ism.’ ” (R. 431). The beginning of faculty desegregation

had been repeatedly postponed until September 1967, al

though petitioners sought such relief from the outset of the

case. Even after this Court ruled in late 1965 that faculty

segregation must be considered in connection with school

desegregation plans, in Bradley v. School Board, 382 TJ.S.

103, and Rogers v. Paul, 382 TJ.S. 198, Judge Johnson felt

constrained by a ruling of the Fifth Circuit involving

Mobile, Alabama, to delay faculty integration in Montgom

ery County until 1967 (R. 285). Finally, after four years

of litigation, at a 1968 hearing, Judge Johnson warned the

school officials that: “ I have gone along with this transition

business for a good long while, but we have passed the

transition period” (R. 544). Judge Johnson entered a

faculty desegregation order which demanded specific results

in 1968 and clarified the ultimate goal to be pursued by the

hoard. The order was justified by (a) a finding that only

slight progress had been made theretofore and the board

had not carried out its affirmative obligations under the

Constitution,9 (b) the similarity of the court-imposed re

quirements to the school authorities’ own estimates as to

how much faculty integration they could accomplish in

9 See opinion of the district court at 289 F. Supp. 647, 649-652.

19

1968,10 and (c) the school authorities’ own expressions of

uncertainty about the ultimate goal to be pursued in de

segregating faculties.11

At an earlier stage (in the June 1, 1967 order) Judge

Johnson had defined the goal generally (R. 370):

The objective of the school system is that the pattern

of teacher assignment to any particular school shall

not be identifiable as tailored for a heavy concentration

of either Negro or white pupils in the school. The

school system will accomplish faculty desegregation in

a manner whereby the abilities, experience, specialties,

and other qualifications of both white and Negro teach

ers in the system will be, insofar as administratively

feasible, distributed evenly among the various schools

of the system.

This identical language was approved by this Court when

it affirmed a decree in Wallace v. United States, 389 U.S.

215, affirming Lee v. Macon County Board of Education,

10 See the testimony of Associate Superintendent Garrett, in the

Statement, supra at pp. 11-12. Judge Johnson noted his reliance on

the board’s planning: “What is actually required in the area of fac

ulty desegregation in the high schools for the 1968-69 school year is

very little—if any—more than the testimony reflects the school

board planned without an additional court order. . . . This also

applies to that part of the Court order as now amended requiring

faculty desegregation for the other schools in the system. Thus,

in the area of faculty desegregation, nothing more is required of

the Montgomery County School Board by the order of February 24,

1968, than the law requires as a minimum at this stage of the

desegregation process and very little, if any, is required more than

the school board, by its testimony, advised this Court it was going

to do anyway.” (289 F. Supp. at 658.)

11 Associate Superintendent’s Garrett’s testimony that he did not

know the objectives of the earlier court order beyond a general

understanding that “ reasonable desegregation of faculty” was re

quired, is quoted extensively in the opinion below. 400 F.2d 1,

at 6, note 5.

20

267 F. Supp. 458, 489 (M.D. Ala. 1967). After this Court’s

action in Wallace, supra, on December 4, 1967, affirmed the

objective that faculty assignments not be so arranged as to

identify schools as tailored for one race and that teachers

be distributed evenly among the various schools, Judge

Johnson then entered the more specific order to assure

specific results in Montgomery County. The order, which

has largely been set aside by the judgment below, further

elaborated the theme sounded in the earlier order and in

Wallace, supra, by stating:

A. Statement of Objective.

In achieving the objective of the school system, that

the pattern of teacher assignments to any particular

school shall not be identifiable as tailored for a heavy

concentration of either Negro or white pupils in the

school, the school board will be guided by the ratio of

Negro to white faculty members in the school system

as a whole.

The school board will accomplish faculty desegrega

tion by hiring and assigning faculty members so that

in each school the ratio of white to Negro faculty mem

bers is substantially the same as it is throughout the

system. At present, the ratio is approximately 3 to 2.

This will be accomplished in accordance with the

schedule set out below. (R. 413)

The majority of the panel below eliminated the ratios

from the decree, saying that compliance should not be de

cided solely by reference to the ratios, and that the faculty

in a particular school need not mirror the racial composi

tion of the total faculty of the system. In place of the trial

judge’s relatively precise goals the panel majority substi

tuted only vague generalities about an “ideal racial bal

ance” :

21

There must be a good faith and effective beginning

and a good faith and effective effort to achieve faculty

and staff desegregation for the entire system. Al

though a ratio of substantially or approximately five

to one is a good beginning, we cannot say that a ratio

of substantially three to two, simply because it mirrors

the racial balance of the entire faculty must be

achieved as a final objective. (400 F.2d at 8.)

# # #

It is hoped and believed that experience will teach

effective ways and means of achieving an ideal racial

balance. . . . They [school boards] have the responsi

bility and should exercise the ingenuity to achieve a

proper racial balance. (400 F.2d at 9.)

The vagueness of the majority’s generalities about “ideal”

and “ proper” racial balances inevitably will leave school

boards and trial judges in the circuit confused about the

ultimate goal. Invariably those officials who resist the

progress of desegregation will construe the ruling to justify

tokenism which merely alters the all-white or all-black

character of a faculty by adding one or two teachers of the

other race. The confusion is compounded by the fact that

the Fifth Circuit is equally divided, thus leaving the out

come of particular future cases to await the accident of

the composition of future panels. We think the point made

by Judge Brown’s dissent below, about the need for specifics

in faculty decrees is irrefutable as a general matter. But

the need is even more imperative in Alabama, with its his

tory of official resistance to desegregation, including the

attempted intimidation of local school boards by the

Governor and State Superintendent of Education to pre

vent faculty integration. See Lee v. Macon County Board

of Education, 267 F. Supp. 458, 465-470 (M.D. Ala, 1967),

aff’d sub nom. Wallace v. United States, 389 U.S. 215.

22

Another practical impact of the judgment below is that it

signals a cautious, go-slow attitude on faculty integration

for trial judges in the circuit, since one of the first district

judges in the area to attempt to push a board beyond mere

tokenism in faculty integration has been reversed. This

plainly will discourage other judges from attempting to

formulate detailed goals for school boards to assure faculty

integration progress.

Both in its vagueness and in its tendency to delay de

segregation, the action below conflicts with this Court’s

decision in Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430.

Green emphasized the needs for action now and for a prag

matic appraisal of desegregation progress. Green’s require

ment is for “a plan that promises realistically to work, and

promises to work now” (391 U.S. at 439). Both goals are

thwarted by the panel’s action here. Neither the Montgom

ery County board, nor the court below, has defined any as

certainable goal toward which progress can be measured

now or later.

The decision also conflicts with Wallace v. United States,

389 U.S. 215, where the per curiam order summarily af

firmed a decree resting on the same essential idea as the

order which has now been set aside. As we read it, the order

in Wallace (quoted supra at 19), covering 99 Alabama

counties, calls for a faculty desegregation plan where

teachers of differing races and qualifications are “ evenly

distributed” among the various schools of a system. The

order involved here merely defines that objective more pre

cisely.

Judge Johnson’s order followed the precedents in other

courts, and the action of the Fifth Circuit conflicts with

decisions in four other circuits approving faculty desegre

23

gation orders requiring that teachers of both races be dis

tributed approximately evenly throughout the systems.

See Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971, 978 (W.D. Okla. 1965), aff’d 375 F.2d 158, 164, 167

(10th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 387 U.S. 931; Coppedge v.

Franklin County Board of Education, 273 F. Supp. 289,

300 (E.D. N.C. 1967), aff’d 394 F.2d 410 (4th Cir. 1968);

United States v. School District 151 of Cook County, Illi

nois, 286 F. Supp. 786, 798, 800 (N.D, 111. 1968), aff’d,

— F.2d ------ (7th Cir., Dec. 17, 1968), 37 U.S.L. Week

2371. The Eighth Circuit has said that the use of such a

formula “comports with Brown” in Kelley v. Altheimer

School District, 378 F.2d 483, 498, n. 24 (8th Cir. 1967);

cf. Yarbrough v. Hulbert-West Memphis School District,

380 F.2d 962, 968-969 (8th Cir. 1967).

The Dowell case was the first reported case in which a

district court required that the percentage of Negro teach

ers in each school should approximate their percentage in

the entire system. It is notable that the percentage formula

was first proposed by an expert panel of educators and not

by lawyers. The court in Dowell made its ruling for the

Oklahoma City system on the recommendations of a dis

tinguished panel of educational administrators who devised

the integration plan for that city at the court’s invitation.

The same formula was adopted by Judge Michie in the

Western District of Virginia in Kier v. County School

Board, 249 F. Supp. 239, 248 (W.D. Va. 1966), where the

court said:

. . . [t]he order of the court to be entered here envi

sions no .. . permanent race consciousness. It is merely

intended to give redress for former faculty segregation

on the premise that, had there been no discrimination

to begin with, the Negro teachers employed by the

county would have been as evenly distributed through

24

out the various schools in the system as, for want of a

better analogy, those teachers with blue eyes or cleft

chins.

In conclusion, it ought to be emphasized that the per

centage goals adopted by the district court were sufficiently

flexible to accommodate administrative difficulties. The

goal was not an exact percentage but “ substantially the

same” ratio. But, if necessary, it would have been unobjec

tionable to define an area of leeway, as for example was

done in Dowell, supra, where the court allowed a ten per

cent margin for individual school variations. Dowell,,

supra, 375 F.2d at 164 Nor did the order import any per

manent notion of racial quotas into the school system. Nor

did the order mandate that teachers be hired or fired on

the basis of race. It merely required that within the con

text of a system formerly segregated by law where existing

employees were about 60% white and 40% black, they be

reorganized into a racially integrated pattern among the

approximately 50 schools of the system. The mathematical

ratios adopted by the court were justifiable as a necessary

remedial measure to assure the “disestablishment of state-

established segregated school systems,” Raney v. Board of

Education, 391 U.S. 443, 449. Approval of the use of such

percentages as remedial measures offends no constitutional

rule against consideration of racial factors. United States

v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F.2cl 836, 876

(5th Cir. 1966), adopted en banc, 380 F.2d 385, cert, denied,

389 U.S. 840 (1967); Wanner v. County School Board of

Arlington County, 357 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1966).

25

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, petitioners respectfully submit that the peti

tion for certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

F eed D. Gray

Solomon S. Seay, Jr.

Gray, Seay, L angford & P ryor

352 Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

F ranklin E. W hite

E lizabeth B. D uB ois

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioners

MEIIEN PRESS INC. — N, Y C. <^§^>219