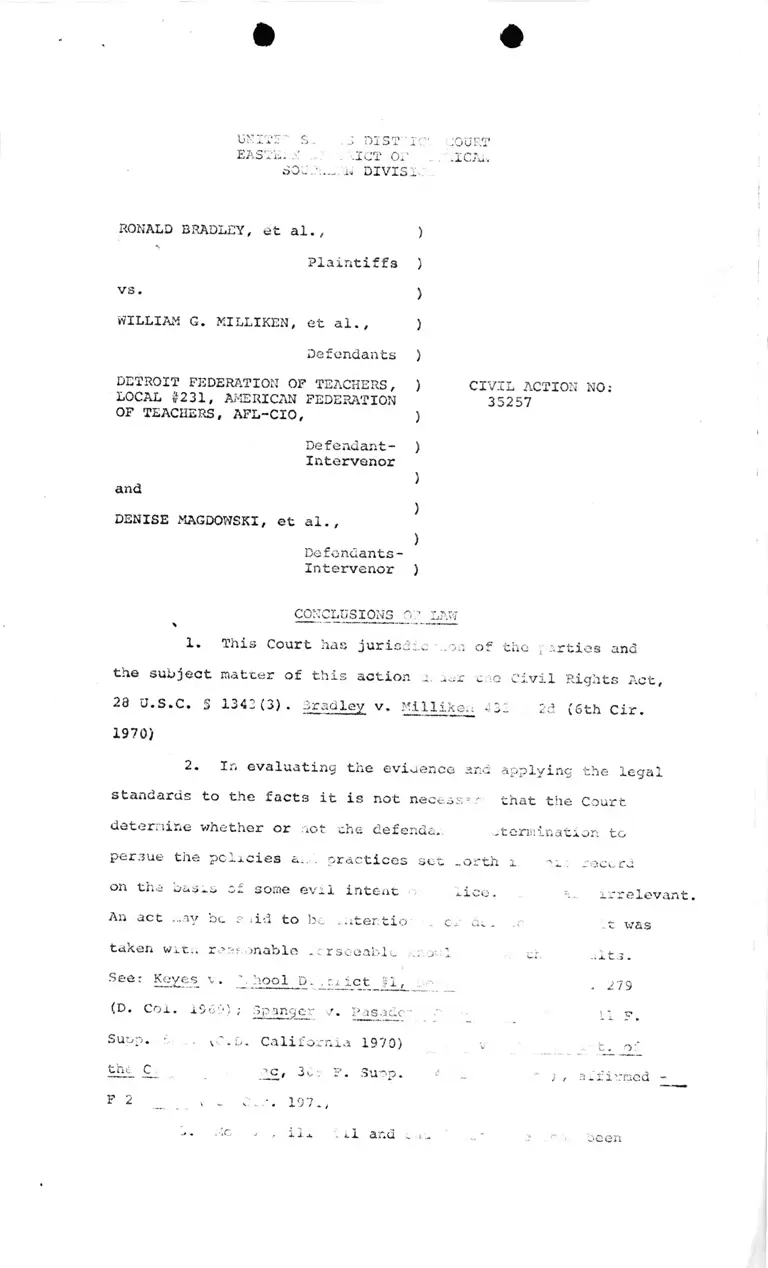

Draft Conclusion of Law 1

Working File

January 1, 1971

17 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Draft Conclusion of Law 1, 1971. 73319fa4-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9dbdcd19-fd9b-449b-a2ab-cc36af098867/draft-conclusion-of-law-1. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

UNITE'" s..

EASTiL M .,

SOU.?

•0 DIST'IC? COURT

-Ict or . . achi,

. L DIVISIU .

RONALD BRADLEY, et al., )

Plaintiffs )

vs. )

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al., )

Defendants )

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, )

LOCAL #231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO, }

Defendant- )

Intervenor

and *

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

)

Defendants-

Intervenor }

CIVIL ACTION NO;

35257

CONCLUSIONS 0? LAW

1. This Court has juriedic .-..on

the subject matter of this action a.

28 U.S.C. S 1343(3). Or ad ley v. Mi 11 ike.

of the parties and

one Civil Rights Act

433 2d (6th Cir.

t

1970)

2. In evaluating the evidence and applying the legal

standards to the facts it is not necesssr- that the Court

determine whether or not the defer.de.. .termination to

per hue the policies a,,, practices set -orth i. nr,: reecr.

on the oasis of some evil intent

An act cay be ? »id to be ,ntentio'

irrelevant,

-t was

taken witn res • >nab 1 & . c rseeable .r.o*. 1 tr. aits.

See; Keyes v. —— -- '• hool D . ,t.x ict §1, .. . 27S

(D. Coi. 1969) ; Sponger v. pasadcr- ! 1 V

Supp. vC•L. California 1970) v 1 ■ t. O •'

the. C f 3 h- 1 ?* * 311 "Op * $ \r ; , a.firmed

F 2 ___ v . C.r. 197.,

.c x i. i 1 and ocen

372 F.2d 836, af£\i eg, tec, 333 F.2d 333 (5th Cir. 1967),

cert, denied, non. <^dao.Ptelch School 3o,rd v. ^ ito6

— — ' 333 U-S- 340 , t o , . Macon County ~f

^lH££tion, 267 F.Supp. 453 (<vr n »7l -.D. >.la.) , afx. d suo norn. Wallace

v* States, 339 U.S. 215 (1967).

7 . School districts era accountable tor the natural '

end probable consequences of their pupil and teacher assign

ment policies, and where racially identifiable schools are

the effect of such policies the school authorities bear the

burden of showing that such policies are based upon educational-

y co.„,.ellea, non-racial considerations. Keyes v. School

Siatrict^o.^. 303 P. Su p p. at 292-293; oTyie v. s^ ~

SiStrict_of the Citv of---------- ----- i £ ™ C ' -- - F* 2 d ____(Sth Cir. 1971).

a. In Brown v. Boa^d^^ducation, 347 U.S. <83, 74 3 Ct

8 8 6. 90 L.Ed. 703 (1954,, the Supreme Court was dealing, simply,

wrth racial segregation. The Court made no distinction as to

Rortnerrt segregation or Southern segregation. The supreme

Court held, Simply, that segregated education is inherently

unequal that it deprived Negro children of the educational

opportunity to fulfill all their dreams in this country. It

further held that all children are deprived, in a constitution

al sense, by segregation. Soangler v. Pasadena citv „«

Vacation, 311 F.Supp. 501 (1970).

9. A violation of the Fourteenth h-.endrer.t has occurred

when public school officials haw aio nCiVe i:nade a -or.os of educational

policy decisions which ware based wholly or ir. pari on con

siderations of the race of students or teachers and which have

contributed to increasing racial segregation in the public

school system. Davis v. ^ g ^ D i s t rict of she ctevon

-------- ’•“ — <6th C i c - 1 3 7 1 > ' P o ijS E lE S r v . L o u i s i a n a

£iS2SStol Assistance 275 F.Supp 833, 837 (S.D.LA

1987), affirmed, 389 U.S. 571, 33 s.ct. C93, 19 L.Ed.2d 730 "

(19G8;; tall v. St. Helena Parish School Board. 1 9 7 ?.supp.

-3-

rejected as a requirement to invoke protection of the 14th

Amendment against alleged racial discrimination. U.S., ex

v* 304 F 2d 53, G5 (5th Cir. 1962). Pro

testations of gopd faith and lack of intention to discriminate

are insufficient to justify racially discriminatory results.

Sims v. Ga. 3S9 U.S. 404 , 407-403 (1967). In Morris v. Alabama

294 U.S. 587, 598 (1935) the Court said If . . . the mere

general assertions by officials of their performance of duty were

to oe accepted as an adequate justification . . . the constitution

al provision - adopted with special reference to (black citizens’]

protection would be but a vain and illusory requirement."

4. When the power to act is available, failure to

take the necessary steos so as to negate or alleviate a

situation which is harmful is as wrong as is the taking of

afiirrnativa steps to advance the situation. Sins of omission

can be as serious as sins of commission. Davis v. School District

Sl.Pp.n&fig* ^c., 309 F. Supp. 734, 741-742, affirmed____F 2d

____ (6th Cir. 1971).

5. In cases where racial discrimination is an issue,

“statistics often tell much, and Courts listen." Alabama v.

States, 304 F. 2d 533, 586 (5th Cir.), affirmed, 371

U.S. 37 (1962). Accord, Turner v. Pouche„ 396 U.S. 346, 369

(1970); Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, No. 29013 (5th Cir. Jan. 2C,

1971) (rehearing on banc pending) ? Griggs v. Duke Power,

U.S.L.W. 4317 ( March 3, 1971).

6. This Court has jurisdiction to hear and to decide

all issues, concerning alleged discrimination in the schools

of the District, including policies involving the assignment

of students, the allocation and hiring of faculty and admini

strators, and the location and construction of schools. Swan:

v* g^£lottG-MecklenbercT Board of Education. 39 U.S.L.W. 4 4 37

(U.S. April 20, 1971); United States v. School District 151,

286 F,Supp. 786 (N.D. 111.), aff'd, 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir.

196o); United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

649, 652 (E.D. La., 1961), affirmed, 363 U.S. 515, 32 S.Ct.

529, 7 L.Ed.2d 521 (1962); United States v. School District

LSI, 404 F .2d at 1134; Taylor v. Board of Education, 191 F.

Supp. 1S1 (S.D.NhY., 1961), affirmed 294 F.2d 36 (2nd Cir.•>

1961), cert, denied, 363 U.S. 940, 32 S.Ct. 3S2, & L.Ed.2d

339 (1961); Griffin v. County School Board, 377 U.S. 213, 231,

84 S.Ct. 1226, 12 L.Ed.2d 256 (1364)* Spangler v. Pasadena

City Board of Education, 311 F.Supp. 501 (1970).

10. The defendants, their predecessors and successors

in office are responsible for the actions and chargeable with

the knowledge of their agents and employees. Regardless of

the policies adopted by any Board or Superintendent, the test

is as a matter of law, what v/as actually dono or failed to be

done in the operation of the public schools. Similarly the

test is the "effect'1 of policies, practices, customs and usages.

[Tr. p. 49-50, 68 (Stephens)] See generally, M. Law & Practice,

Vol. 1'Agency § 1 and 111; MLP Vol. 10 s 131; Compare;

Poindexter v. La. Financial Assistance Comm., 236 F.Supp. 6S6

E.D. La. aff*d per curiam sub non, La. Ed. Commission for Needy

v. Poindexter, 393 U.S. 17 (1968); same, 275 F.Supp.

833 (E.D.La., 1967), 389 U.S. 571 (1963).

11. The equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment forbids States from drawing distinctions on account of

race. Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954); Watson v.

373 U.S. 526 (1963). The Constitution forbids

indirect, as well as direct, discrimination on a racial basis,

v* i±£2R' Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 123, (1940)). The

Constitution equally "nullifies sophisticated as well as simple

minded modes of discrimination." Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 263, 275;

Sraith v. Texas, supra, at 132 (1940).

12. In determining whether a constitutional violation

-4-

has occurred, proof that a patcrn of racially segregated

schools has existed for a considerable period of tine amounts

to a showing of racial classification by the State and its

agencies, local school authorities, which must be justified

by clear and convincing evidence. Alabama v. United States,

304 F.2d 533, 586 (5th Cir.)„ aff'd 371 U.S. 37 (1302); United

States v. Board of Educ. of Bessemer, 390 F.2d 44, 46 (5th Cir.

1968); Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Dd., 417 F.2d SOI, 309

(■juh Cir.) , cert. denied, 396 U.S. 304 (1969); Turner v. Fouche,

396 U.S. 346, 360 (1370); Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, F.2d

____ (5th Cir. 1970); Kennedy Park Homes, Inc, v. Town of

•Lackawanna, __ F.2d___(2nd Cir.), Cert. Denied, u.S.

___ (1971); Chambers v. Hendersonville City Bd. of Educ., 374

F.2d 183, 192 (4th Cir. 1966); P.olfe v. County Bd. of Educ. of

Ml?cpln County, 391 F.2d 77, SO (<7th Cir. 1968); United States

v * School District 151, 301 F.Supp. 201.

' 12. The Board's practice, which transcended individual

instances, of shaping school attendance zones on a north-south

rather than east-vest orientation, with the result that zone

boundaries conformed to racial residential dividing lines and

segregation was entrenched, violating the Fourteenth Amendment.

ggP-Vgr v. School Dd. of Norfolk, ___ F.2d___(4th Cir. I960) ;

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Pint.. 409 F.2d

682 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, ___U.S. ___ (1969); Northcross

v- g°nrd of Educ. of Memphis, 333 F.2d 661, 663-64 (6th Cir.

1964); Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little ftnek, 426 F.2d

(3th Cir. 1970).

13. Pupil racial segregation in the Detroit public

school 3ydten and residential racial segregation resulting

primarily from public and private racial discrimination are

interdependent phenomena. The affirmative obligation of the

defendant Detroit Board has boon and i3 to adopt and implement

• •

pupil assignment policies and practices that, to the maximum

extent possible, compensate for and avoid incorporating into

the school system the effects of residential racial discrimination.

The Board's purposeful and deliberate building upon housing

segregation violates the Fourteenth Amendment. See Davis v.

School District of the City of Pontiac, supra; Drover v. Norfolk

School Board, 397 F.2d 37, 41 (4th Cir. 1968); Henry V. Clarksdale

Municipal Separate School District, 409 F. 2d 682, 687, 6 89 (5th

Cir. 1969); Spangler and United States v . Pasadena City Board

of Education, above, 311 F.Supp. at 512; Sloan v. Tenth School Dist.

of Wilson County, 433 F.2d 587 (6th Cir. 1970).

14. The defendant Detroit Board's policy of selective

optional attendance zones, to the extent that it facilitated the

separation of pupils on the basis of race, was without educational

justification and in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Hobson v. Hanson, 269 F.Supp. 401, 499-501 (D.D.C., 1967),

affirmed, Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d 175 (D.C. Cir. 1969); Taylor

v. New Rochelle Board of■Education, 234 F.2d 36, 38 (2d Cir. 1961),

cert. denied, 368 U.S. 940 (1961); Spangler and United States

v. Pasadena City Board of Education, 311 F.Supp. at 507-508,

512; Kelley v. Altheimer, Arkansas Public School District No.

22, 297 F.Supp. 753, 758 (E.D.Ark., 1969); Montgomery v.

Oakley Training School, 426 F.2d 269, 271 (5th Cir. 1970).

15. By requiring that students from majority black

residential areas be transported to majority white schools to

relieve overcrowding, while not transporting children from

majority white residential areas to majority black schools

(which have space available) to relieve overcrowding, defendants

have placed an unfair burden and stigma on black children and,

thus, have violated the Fourteenth Amendment. See; Brice v.

Landis, 314 F.Supp. 974 (N.D. Calif. 1969); Lee v. Macon County

C-

Board of Educ., No. 30154 (5th Cir. June 29, 1971); Cordon v.

Jefferson Davis Parish School Board, No. 30075 (5th Cir. June

20, 1971); Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Educ., 311 F.Supp.

501, 524 (C.D. Calif. 1970).>

, 16. The Detroit Board's manipulation and gerrymandering

of attendance tone boundary lines to foster segregation by

expanding the zones of identifiably black schools to contain

increasing black populations or by removing areas of one racial

composition from a zone for a school identifiable- as serving

students of a different race. Taylor v. Board of Educ. of New

Rochelle, 294 F.2d 36 (2d Cir.), Cert, denied, 368 U.S. 940 (1961);

United States v. School Dist. 151, 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968);

Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., 311 F.Supp. 501, 507-10,

522 (C.D. Calif. 1970); Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, 309

F.Supp. 734, 744 (E.D. Mich. 1970); aff'd ____F.2d ___ (6th

Cir. 1970); Northcroos V . Board of Ed. of the City of Memphis,

333 F .'2d 661, 663-664 (6th Cir. 1964).

17. The practice of the Board, contrary to its avowed

policy, of transporting black students from overcrowded black

scnools to other identifiably black schools while passing closer

identifiably white schools which could have accepted these

children and thus achieved greater desegregation-has been held

to be deliberate segregation by school authorities. Spangler

v * Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., 311 F.Supp. 501, 507-03, 512

(C.D. Calif. 1970); Kelley v. Alfcheimer, 297 F.Supp. 753, 758

(E.D. Ark. 1969); Montgomery v. Oakley Training School, 426

F.2d 269, 671 (5th Cir. 1970). The assignment of black students

who were bussed into white schools as an intact group to classes

rather than mixing them with the other members of the student

body has been held unconstitutional as early as HcLaurin v.

Oklahoma Bd. of Regents, ___ U.S. ___ (1950); cf. McNeoso v.

Board of Educ., __F.Supp __ (N.D. 111.____), aff’d F.2d

(7th Cir. ___), rcv'd ___ U.S.__ (1963). In-school

segregation is equally violative of constitutional rights as

segregation by school building. Johnson v. Jackson Parish

School Bd., __ F.2d __ (5th Cir. 1970); Jackson v. Marvell

School Pint. Ho. 22, __F.2d __ (8th Cir. 1970).

18. The manner in which the District formulated and

modified attendance zones for elementary schools had the natural

inevitable and predictable effect of perpetuating and exacerbating

existing racial segregation of students. Such conduct con

stitutes de jure discrimination in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment. United States v. School District 151, 285 F.Supp. 786,

795-736, 798 (N.D. 111.), a f f d , 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968);

Brewer v. City of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37, 40-42 (4th Cir. 1963);

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 831

367-863 (5th Cir. 1965), affd en banc, 330 F.2d 375 (1966),

cert, denied, 389 U.S. 840 (1967); Taylor v. Board of Education,

294 F.2d 36 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 368 U.S. 940 (1961); Spangler

v. Pasadena City Board of Education, 311 F.Supp. 501, 522 (C.D.

Cal. 1970); Davis v. School District, 309 F.Supp. 734, 744 (E.D.

Mich. 1970), a f f d ___F.2d____(6th Cir. 1371).

19. A school board may not, consistently with the

Fourteenth Amendment, maintain segregated elementary schools

or permit educational choices to be influenced by a policy of

racial segregation in order to accomodate community sentiment

or the wishes of a majority of voters. Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U.S. 1, 12-13, 15-16 (1958); Lucas v. Forty-Fourth General

Assembly, 377 U.S. 713, 736-737 (1964); Hall v. St. Helena

Parish School Board, 197 F.Supp. 649 , 659 (E.D. La.), affd

368 U.S. 515 (1961); Roltnan v. Mulkev, 307 U.S. 369 (1967);

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 331 U.S. 450 (1958); United

States v. School District 151, 285 F.Supp. 786, 798 (11.B. 111.)

affd, 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1963); Spangler v. Pasadena City

Board of Education, 311 F. Supp. 501, 523 (C.D. Cal. 1970).

-8-

20. Assignment of teachers on a racial basis so that

teachers are assigned to schools attended bv children of their

race tends to establish racially identifiable schools. Such

assignment deprives students of their right to be free of racial

discrimination in the operation of public elementary schools

and is de jure segregation in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment- Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. IDS (1965); Bradley v. School

Board, 382 U.S. 103 (1965); Green v. County School Board, 391

U.S. 430 (1968); United States v. School District 151, 286 F.

Supp. 786, 797 (N.D. 111.), aff'd, 404 F.2d 1123 (7th Cir.

1968), Cert, denied, 39 U.S.L.W. 3486 (1971); Spangler v.

City Board of Education, 311 F.Supp. 501, 523 (C.D.

Cal. 1970); Davis v. School Pistrlct, 309 F.Supp. 401, 501-503

(D. D.C. 1967), appeal dismissed, 393 U.S. 801 (1968).

21. lhe defendant Detroit Board*s racially discriminatory

P^^etices with respect to the assignment of faculty and staff

personnel, an aspect of school administration over which the

defendants have direct and continuing control, creates an

inference, which the defendants must dispel by credible evidence,

that other school board policies and practices which resulted in

the racial separation of pupils were racially discriminatory.

United States v. School District 151, 301 F.Supp. 201, 223-230

(N.D. Hi. 1969), affirmed as modified, 432 F.2d 1147, 1151

(7th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, ___U.S. _____, 39 L.W. 3486 (1971);

Turner v. Fouche, 336 U.S. 346, 360 (1970).

22. The responsibility for faculty and administration

desegregation is defendants', not the teachers and administra

tors . The constitutional prohibition against segregation in

public schools may not be made contingent upon the preferences

of teachers or the administrative staff. If necessary to further

desegregation, faculty and administrators must be assigned

-9-

United States vinvoluntarily to S C h O O l s . School District 151,

28C F.Supp. 736 (N.D. 111.), aff»d, 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir.

1963); United States v. Board of Education, 396 F.2d 44 (5th

Cir. 1968); David v. Board of School Commissioners, 393 F.2d 690

"V * » r » . I -- „ ini

(5th Cir. 1968); Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Education,

311 F.Supp. 501, 523 (C.D. Cal. 1970).

23. Defendants are under a constitutional obligation

to take affirmative remedial action to desegregate the faculties

and administrativo staffs of the public elementary schools forth

with. United States v. Montgomery Board of Education, 395 U.S.

225 (1969); United States v. School District 151, 286 F .Supp.

786, 797 (N.D. 111.), a f f d , 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968);

Clark v. Board of Education, 369 F.2d 661, 66S (8th Cir. 1966)?

States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F.2d

836, 893, affd en banc, 330 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert.

denied, sub non. Caddo Parish School Board v. United States,

389 U.'S. 840 (1967); Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Educa-

tion, 311 F.Supp. 501, 523 (C.D. Cal. 1970); Davis v. -School

District, 309 F.Supp. 734, 744 (E.D. Mich. 1970).

24. When an unconstitutional pattern of teacher

assignment has been found the standard for relief is assign

ment of staff "so that the ratio of Negro to white teachers in

each school, and the ratio of other staff in each, are sub

stantially the same as each such ratio is to the teachers and

otnt.r staff respectively, in tne entire school system. Swann,

supra.; Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist.,

419 F.2d 1211 (1970).

25. The location of schools "influences the pattern

of residential development of the city and metropolitan area

and have important impact on composition of inner city neighbor

hood. 11 The classic pattern is often the building of schools

specifically intended for Negro or white students. The building

of new schools in areas of white suburban expansion farthest from

-10-

Negro population centers, in areas of Negro containment, in order

to maintain the separation of the races with a minimum departure

from the formal principles of “neighborhood zoning" promotes

segregated residential patterns which, when combined with

”neighborhood zoning", further lock the school system into the

mold of separation of the races. Swann v. Charlotto-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 39 U.S.L.W. 4437, 4444, cited in Davis v.

School District of the City of Pontiac, Inc., #20477 ___ F.2d

____ Slip op. p.10 (concurring opinion of Judge Cecil) (6th

Cir. 1971); Accord, Kelly v. Metropolitan Co-gnty Board of

Nashville, Tenn., 436 F.2d 856, (6th Cir. 1970); Brewer v.

School Board of City of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37, 42 (4th Cir. 1968);

Sloan v. Tenth School District of Wilson County, 433 F.2d 587,

589 (6th Cir. 1970); Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Educ.,

311 F. Supp. 501,522 (M.D. Calif. 1370).

26. By building new elementary schools and additions

to old schools in a manner that creates maintained and exacerbated

existing segregation of elementary school pupils, the District

caused do jure segregation in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg, 39 U.S.L.W. 4437,

4443 (U.S. April 30, 1971); United States v . Montgomery County

Board of Education, 395 U.S. 225, 231 (1369); Lee v. Macon

County Board of Education, 267 F.Supp 458, 472, 4S0 (M.D. Ala.),

affect, 309 U.S. 215 (1967); United States v. Board of Public

Instruction, 395 F.2d 56, 69 (5th Cir. 1968); United States v.

School District 151, 276 F.Supp. 786, 800 (M.D. 111.), aff'd,

404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968); Brewer v. City of Norfolk,

397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968); Spangler v. Pasadena City Board

of Education, 311 F.Supp. 501, 517-519 (C.D. Cal. 1970); Davis

v. School District, 309 F.Supp. 734, 741 (E.D. Mich. 1970);

aff’d, _ F.2d ___ (6th Cir. 1971).

27. The Board' 3 school construction policies and

practices have added to and reinforced the pattern of segregation re

ferred to. Although there were vacant seats throughout the city

-11-

to which students could have been assigned at lesser cost

and with the achievement of integration, the Board continued

to expend substantial sums for construction of new schools

designed to service particular areas of racial concentration,

and "such schools opened as and have continued to bo racially

identifiable in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 91 S. Ct. 1284, __(1971);

United States v. School Dist. 151, 404 F.2d 1125, 1132-33 (7th

Cir. 1968); Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, 309 F. Supp.

734, 741-42 (E.D. Mich. 1970), aff»d____F.2d.___ (6th Cir.

1971); Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., 311 F.Supp. 501,

517-13 (C.D. Cal. 1970); Johnson v. San Francisco Unified

School Dist., Civ. Ho. C-70-1331 (N.D. Cal., April 28, 1371);

cf. Sloan v. Tenth School Dist. of Wilson County, ___F2d.___,

(6th Cir. 1970); United States v. Board of Educ. of Polk Countv,

.. — - — --------------------- —---------------------- -— . ..... . . r

___F.2d___ (5th Cir. 1968); Kelley v. Aitheim.er, __ F.2a__

(8th Cir. 1967); Bradley v. School Bd., __ F.Supp ___ (E.D.

Va. 1971); Clark v. Board of Educ. off Little Rock, 401 U.S. 971

(1971).

28. The legal effects of racially discriminatory con

finement to a school district are not different from the effects

of such containment within a district. Lee v. Macon County

Board of Education, ____F.2d____ (5th Cir. Ho. 30, 154, decided

June 29, 1971.

29. The obligation of school districts found to be

illegally segregated on the basis of race is to prepare, adopt,

and implement such plans — giving affirmative consideration to

racial factors — as will eradicate the effects of prior dis

crimination and "achieve the greatest possible degree of actual

desegregation". Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of

Education, above, 91 S.Ct. at 1281; McDaniel v. Barresi,

U.S. ____, 91 S. Ct. 12S7, 1289 (1971).

30. The related doctrines that race and Socio-Economic

-12-

Status correlate highly and that better quality education is

more readily provided in schools attended predominatly by

higher SES pupils may be educationally supportable, but they

may not be employed as a limitation upon a school district's

obligation to eliminate — by pupil desegregation — the effects

of its prior discriminatory practices, particularly where the

Grfect of such a limitation would be to “protect" ciuality

education at the schools attended predominantly by white students

while denying the equal protection of the laws by perpetuating

lesser education at scnools attended predominantly by black,

lower SES children. Swarm v. Charlotte-Hocklenhera Beard of

Education, 91 S.Ct. at 1200, note 8; Brunson v. Board of Trustees

•i*2v F.2d 020, 324 et. seq. (4th Cir. 1970); brewer v. School

Board of City of Norfolk, __ F.2d ___ (4th Cir. 1970).

31. The public and private racially discriminatory

policies that have effected the extreme containment of black

families within the Detroit school district deny equal education—

al opportunity to the children of such families, and the State,

which is empowered to alter school district lines, is obligated

to do so absent a showing of a compelling non-racial, educational

justification for maintaining such lines. Brown v. Board of

Education, 349 U.S. 294, 300-301 (1955).

32. The Court concludes that Sec. 2a of Act 48 and

the action of the Governor's Commission pursuant to that Act in

establishing the present regions, has the effect of making de

segregation more difficult; and to the extent that any of its

provisions make any plan of desegregation more difficult it may

not as a matter of law be considered. Bradley v. Milliken,

433 F .2d 397, (6th Cir. 1970),

33. Under the Constitution of the United States and

the Constitution and the laws of Michigan, the responsibility

for providing public educational opportunity to all children

on constitutional terms is ultimately that of the State. Turner

v * Warren County Board of Education, 313 F.Supp. 330 (E.D.N.C.,

1970); Godwin v. Johnston County Board of Education/ 301 F.Supp.

1339 (E.D.N.C. 1969); United States v. Texas Education Agency,

431 OF.2d 1313 (5th Cir. 1S70); Article 8, 55 1 and 2, Michigan

Constitution; Dasaiewicz v. Board of Education of City of

Detroit,. 3 N.W* 2d 71 (Mich. 1942); Jones v. Grand Ledge Public

Schools, 84 N.W. 2d 327 (Mich. 1957); M a y 'Arp, Primary School

District v. State Board of Education, 102 N.W. 2d 720 (Mich. 1960)

34. The Michigan Constitution of 1963 gives the State

broad authority and responsibility for public education. It

provides; "The legislature shall maintain and support a system

of free public elementary and secondary schools as defined by

law." Art. VIII, Sec. 2 School districts "are agencies of the

State, deriving their powers from the State, not independent

entities with inherent rights, privileges or immunities." School

Diet. Mo. 7, et. al. v. The Board of Education of the IntermediateS **■’ ' " “ ----- " ' 1 ....... —1..."

School District of the County of Kent et. al., No. 4585 (Kent

eir. et., Oct. 16, 1967) (slip op. at 4-S); Attorney General

ex rel Kies v. hawrey, 131 Mich. 639; School District of the

City of Lansing v. State Board of Education, 367 Mich. 591;

Xmlay Township Primary School District No. J v. Board of Education,

359 Mich. 478; Jones v. Grand Ledge Schools, 349 Mich. 1.

35. "That a state's form of government may delegate the

power of daily administration over public schools to officials

w±th less than state-wide jurisdiction does not dispel the

obligacxon of those who have broader control to use the authority

they have consistently with the Constitution . . . In such

instances the constitutional obligation toward the individual

school children is a shared one.” Bradley v. School Board

9l ..the City of Richmond, Virginia, 51 F.R.D. 139, 143 (1970).

C6. In addition to the State Board and State Super

intendent the next level of public education is the Intermediate

school district. They are in most instances contiguous with

-14-

county boundaries but in other instances they extend beyond

those political boundaries. {19 Tr. 2045 Porter] M.S.A. 15.3291

ct. soq. Tho superintendent and board in all respects are the

legal successors to the powers, duties and responsibilities of

the county superintendent and county board of education. Tho

first duty of the superintendent is to "TPJut' into practice

educational policies of the state and of the board, . . .

Pc_j.oi.il such duties as the superintendent of public instruction

or the board prescribes . . .,** and generally supervise

distribution and accounting of state aid to local districts.

M *S*A * IS.3301(1). The Intermediate board provides for certain

types of education on a county wide or multi-district basis.

(±9 Tr. p. 2044). They also supervise, recommend and approve

consolidations and annexations of local districts. (Vol. p. )

P.a . lolA. State law provides for combinations and annexations

of those Intermediate districts subject to the approval of the

State Board of Education. M.S.A. 15.3302(1); 15.3303(1).

r/. Leadership and general supervision over all public

education is vested in the State Board of Education. Art. VIII Sec

3, Mich. Constitution 1363. The duties of the State Board and

Superintendent include but arc not limited to, specifying the

number of hours necessary to constitute a school day; approval

until 1962 of school sites; approval of school construction

plans (P.Exs. 10 & 174,); accreditation of schools, approval of

IocUjs based on State aid funds; review of suspensions and

explusions of individual students for misconduct [Op. Attv.

Gen. July 7, 1970, Mo. 4705}; authority over transportation

routes and disbursement of transportation funds, teacher

certification and the like 15:1023 (10) (Porter, Tr. Vol 19

p. 2057-03). State law provides review procedures from actions

o± local-or intermediate districts (See M.S.A. 15.3442), with

authority in the State Board to ratify, reject, amend or modify

hue actions of-these inferior state agencies. See M.S.A.

15.3467; 15.1919 (91); 15.1313 (62b)j 15.2299 (1); 15.1961?

15.3402; Bridgohamoton School District No. 2 Fractional of

Caraonville Mich. v. Supt. of Public Instruction, 323 Mich. 615.

In general, the state superintendent ic given the duty "To do

all'things necessary to promote the welfare of the public schools

and public educational instructions and provide proper

educational facilities for the youth of the state." M.S.A.

lo.3252. See also 15.2299 (57), providing in certain instances

for reorganisation of school districts.

Jo. State officials including all of the defendants, are

charged under the Michigan constitution with the duty of providing

pupils an education without discrimination with respect to race.

Art. VIII Sec. 2 Mich. Const. 1963. Article I Sec. 2 of the

constitution provides:

No person shall be denied the equal pro

tection of the laws; nor shall any person

be denied the enjoyment of his civil or

political rights or be discriminated against

in the exercise thereof because of religion,

race, color or national origin. The legis

lature shall implement this section by

appropriate legislation. Compare: Jenkins

v. Morristion School District, #A-117~ C j 7

Supreme Court July 25, 0 7 1 “Tslip o p . p .

12, 14 and 16)

3S. The State Department of Education has recently

established an Equal Educational Opportunities section having

responsibility to identify racially imbalanced school districts

and develop desegregation plans. [19 Tr. p, 2045 (Porter)]

Section 15.3355 provides that no school or department shall be

kept for any person or persons on account of race or color.

40. The state further provides special funds to local

oldtracts ior compensatory education which are administered on

a per senool oasis under direct 'review of the state board. All

otner state.aid is subject to fiscal reyeiw and accounting by

the state. M.S.A. 15.1919 (53), (61), (62), (64a). See also

l-> .1919 (68b) providing for special supplements to merged

districts "for tho purpose of bringing about uniformity of

educational opportunity for all pupils of the district." The

general consolidation law M.S.A. 1J:3401 authorises annexation

for even noncontiguous school districts upon approval of the

superintendent of public instruction and electors, as provided

by law. Op. Atty. Gen., Feb. 5, 1964, No. 4193. Consolidation

with respect to so called "first class" districts, i.e. Detroit,

is generally treated as an annexation with the first class

district being the surviving entity. The law provides procedures

covering all necessary considerations. M.S.A. 15.3184, 15.3186.

41. The pattern of actions and ommission on the part

of noth State and District defendants constitute collectively

a pattern of conauct vroiative of the 14th Amendment. "Tho

fact that such came slowly and surreptitiously rather than by

legislative pronouncement makes the situation no less evil."

i i