Plaintiffs’ Pre-Trial Brief with Letter to Judge Pittman RE: Washington v. Davis

Public Court Documents

July 9, 1976

18 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Plaintiffs’ Pre-Trial Brief with Letter to Judge Pittman RE: Washington v. Davis, 1976. 1cf9b782-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9ddfd028-e341-4dcc-a0e8-9b6cf6808bbf/plaintiffs-pre-trial-brief-with-letter-to-judge-pittman-re-washington-v-davis. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

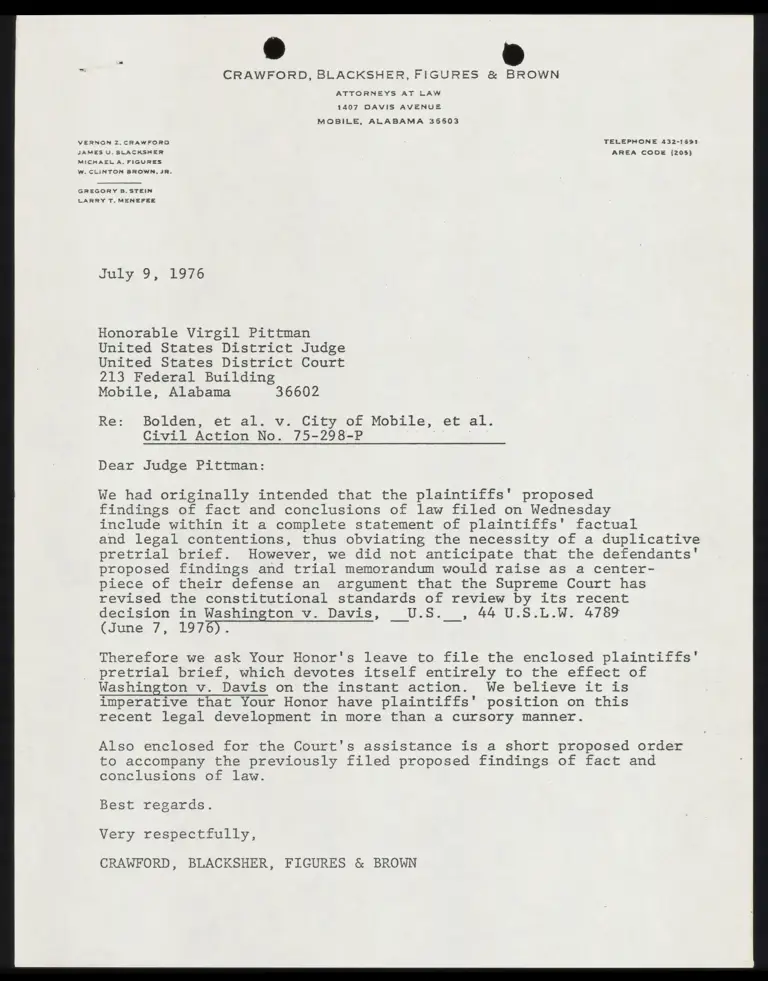

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIGURES & BROWN

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

1407 DAVIS AVENUE

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36503

VERNON Z. CRAWFORD TELEPHONE 432-15%%

JAMES U. BLACKSHER AREA CODE (205)

MICHAEL A. FIGURES

W. CLINTON BROWN, JR.

GREGORY B. STEIN

LARRY T. MENEFEE

July 9, 1975

Honorable Virgil Pittman

United States District Judge

United States District Court

213 Federal Building

Mobile, Alabama 36602

Re: Bolden, et al. v. City of Mobile, et al.

Civil Action No. 75-298-P hes

Dear Judge Pittman:

We had originally intended that the plaintiffs' proposed

findings of fact and conclusions of law filed on Wednesday

include within it a complete statement of plaintiffs' factual

and legal contentions, thus obviating the necessity of a duplicative

pretrial brief. However, we did not anticipate that the defendants’

proposed findings and trial memorandum would raise as a center-

piece of their defense an argument that the Supreme Court has

revised the constitutional standards of review by its recent

decision in Washington v. Davis, U.S. , 44 U.S.L.W. 4789

(June 7, 1976).

Therefore we ask Your Honor's leave to file the enclosed plaintiffs’

pretrial brief, which devotes itself entirely to the effect of

Washington v. Davis on the instant action. We believe it is

imperative that Your Honor have plaintiffs' position on this

recent legal development in more than a cursory manner.

Also enclosed for the Court's assistance is a short proposed order

to accompany the previously filed proposed findings of fact and

conclusions of law.

Best regards.

Very respectfully,

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIGURES & BROWN

July ©, 1975

Honorable Virgil Pittman

Page 2.

A

U. Blacksher

JUB:bm

Enclosures

cc: Charles A. Arendall, Esquire

S. R. Sheppard, Esquire

Edward Still, Esquire

Charles Williams, III., Esquire

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

CIVIL ACTION

VS.

NO. 75-298-P_

CITY OF MOBILE, et al.,

Defendants.

PLAINTIFFS' PRETRIAL BRIEF

Plaintiffs submit this pretrial brief solely for the

purpose of responding to the argument made in defendants’

trial memorandum, filed on or about July 7, 1976, that

Washington v. Davis, U.S. , 44 U.S.L.W. 4789 (June 7,

1976), establishes a ''mew Supreme Court 'purpose' test."

D.Br.at 9. Defendants even suggest that the Davis decision

either supersedes ormakes unnecessary consideration of the

"primary" and "enhancing' factors in Zimmer v. McKeithen,

485 F.28 1297 (5th Cir. 1973)(en banc), aff'd, sub nom, East

Carroll Parish School Bd. v. Marshall, U.S. , 44 U.S.L.W.

3

J

4320 (March 8, 1976) (per curiam). The indicia of unconstitutional

black vote dilution formulated in" Zimmer, say the defendants,

- ho ae. en indie ie 5 ’

"do not Include intent." D:Br. at 16, Plaintiffs submit this

simply is not so. As this brief will show,” Washington: v,

———

Davis, supra, merely reemphasizes the requisite concepts of

intent referred to in many previous Supreme Court decisions.

Zimmer includes these well-established principles of intent

in its indicia of unconstitutional dilution.

Plaintiffs, of course, agree that they must prove

purposeful or intentional dilution of black citizens' voting

strength by the present election system in order to pravatl.

We are fully prepared to do so. The evidence will show that

the State of Alabama, through its legislators and officers,

has used the at-large system for electing Mobile City

Commissioners (1) with an actual motive or purpose to dis-

criminate against the black citizens of Mobile and, in any

case, (2) with the intent to discriminate that must be presumed

of those who should foresee the natural consequences of

their actions.

i

“Washington v. Davis Establishes No New

Constitutional Principles isi

One should begin consideration of Washington y. Davis,

supra, with the note of caution sounded in the concurring

opinion of Justice Stevens:

[T]he extent to which one characterizes

the intent issue as a question of fact or

a question of law ... will vary in different

contexts.

My point in making this observation is to

suggest that the line between discriminatory

purpose and discriminatory impact is not nearly

as bright, and perhaps not quite as critical,

as the reader of the Court's opinion might

assume.

44 U.S.L.W. at 4800. Justice Stevens' comments comport with

the similar warning contained in Justice White's majority

opinion:

Necessarily, an invidious discriminatory

purpose may often be inferred from the totality

of the relevant facts including the fact, if

it is true, that the law bears more heavily on

one race than another.

44 U.S.L.W. at 4792 (emphasis added). Thus, the requirement

of a discriminatory purpose is nothing new to constitutional

law, and the Supreme Court is only reminding us of that in

Davis. It neither suggested nor inferred that it was

announcing new standards for determining when such discriminatory

purpose existed in particular cases.

Indeed, Washington v. Davis must be read in the context

of the extreme stance taken by the plaintiffs-respondents in

that action. Justice White's opinion tells us that the

plaintiffs made no claim in the district court of "an intentional

discrimination or purposeful discriminatory actions." 44 U.S.

3

L.W. at 4790. When the Court of Appeals for the District

of Columbia reversed the district court, it "went on to

declare that lack of discriminatory intent in designing and

administering Test 21 was irrelevant...." 44 B.S.L.Y. at

4791. With the issues presented in this extreme posture,

it could almost be said that plaintiffs and the Court of Appeals

were daring the Supreme Court to rule against them.

Clearly the Court was up to the task, and it simply refused

to affirm a decision predicated on constitutional grounds

that made no attempt to demonstrate discriminatory intent and

even insisted that no such showing was necessary.

The central purpose of the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment is the prevention of official

conduct discriminating on the basis of

race. ... But our cases have not embraced

the proposition that a law or other official

act, without regard to whether it reflects

a racially discriminatory purpose, is

unconstitutional solely because it has a

racially disproportionate impact.

44 U.S.L.W. at 4792. The opinion then refers to a number of

earlier Supreme Court decisions that discuss the necessity

of demonstrating discriminatory intent in the constitutional

context, including Wright wv. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52 (1964) ,

and Keyes v. School District No.l, 413 U.S. 189 (1973).

Although Davis expresses some disapproval of a long list of

federal court decisions that might be interpreted in conflict

with it, it neither overruled nor expressed its disapproval of

liu

any Supreme Court or appellate court voting rights decisions,

particularly not the seminal cases of White v. Regester,

412 U.S. 755 (1973),and Zimmer v. McKeithen, supra, which the

Court had reviewed only three months earlier.

Therefore, while Washington v. Davis, supra, very clearly

requires this Court to find discriminatory intent as one of

the elements of any successful Fourteenth or Fifteenth

Amendment claims, it in no way disturbs the principles already

established by the Supreme Court, the Fifth Circuit and other

federal courts concerning the proper legal standards to be

applied to determine whether such intent in fact exists.

1

" Mobile's At-Large Election System

Was Designed And Is Utilized With

The Motive Or Purpose of Diluting

The Black Vote

The City argues that this Court should find that Act

281, Ala.Acts (1911), "was enacted for a non-discriminatory

purpose and, under Washington v. Davis, that finding should end

the inquiry, with Yudemint for defendants being mandated."

D.Br. at 20. Further, according to the defendants, such a

finding of non-discriminatory purpose should be predicated

entirely on the assumption that, because black Mobilians

had already been totally disenfranchised by the Alabama

Constitution of 1901, racial discrimination could not have

been one of the motives behind Act 281 in 1911. D.Br. at 19.

But the defendants have miscast the issue. The question

is not just whether the Legislators who voted for Act 281

were racially motivated, but whether the whole electoral

system, including the intentional discrimination that both

ante-dated and post-dated Act 28l's passage, is the product of

a past racially discriminatory purpose, the effects of which

are still felt today, and/or a present intention to dis-

eriminate by the State of Alabama. For example, in Wright

v. Rockefeller, supra,cited in Washington v. Davis, 44 U.S.

L.W. at 4792, the Supreme Court upheld a district court's

finding of fact that certain congressional boundaries in

New York had not been racially gerrymandered. The inquiry

addressed only the motives of the New York State Legislators who

had just drawn the lines. The Court carefully distinguished

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954), and Norris v. Alabama,

294 U.S. 587 (19 ), where in the context of jury dis-

crimination it had previously laid down the rule that a prima

facie case of unconstitutionality could be made out by proof

of a long-continued state practice of discriminating against

blacks. The fact that no such long-standing history of racial

discrimination by the State of New York was either alleged

or proved in Wright meant that the constitutional inquiry

could focus solely on the motives of the Legislators then

convened. As Mr. Justice Black, writing for the Court in

hye

Wright, carefully explained, ''state contrivance to segregate

on the basis of race ... was crucial to appellants' case as

they presented it, and for that reason their challenge cannot

be sustained.” 376 U.S. at 58.

By contrast, the entire history of official racial

discrimination in the State of Alabama is very much a part

of plaintiffs’ prima facie case herein. Plaintiffs will show

(primarily through the testimony of an expert historian) that

black people in Mobile and in Alabama generally were very

active in the political process from the Reconstruction

period until the Constitution of 1901 disenfranchised them.

It is absolutely clear that the delegates to the 1901 Alabama

Constitutional Convention were motivated by an openly

expressed desire to take the vote away from black citizens,

who resisted unsuccessfully. Thereafter, it could accurately

be said that through white primaries, interpretation tests,

poll taxes and other devices

from the Constitutional Convention of 1901

to the present, the State of Alabama has

consistently devoted its official resources

to maintaining white supremacy and a segregated

society.

United States v. Alabama, 252 F.Supp. 95, 101 (M.D. Ala. 1945).

The black citizens of Mobile were no better off than blacks

elsewhere in Alabama in terms of the barriers thrown up in

the way of their right to register and vote. Some of the

plaintiffs in this action will give personal testimony to

these facts.

It is true that there was little outward evidence of

a racial motivation in the passage of Act 281 or in the 1911

referendum that changed Mobile's city government to an at-

large commission. However, the Court should note with interest

that two of Mobile's most active leaders in favor of the

1911 city government change, Pat Lyons and Harry Pillans,

were also leading forces in the work of black disenfranchisement

at the 1901 Constitutional Convention. There is then some

evidence connecting Act 281 with the contemporary movement

to discriminate against black voters. In any event, as a

matter of law the State's actions in 1911 cannot be entirely

divorced from its overt discriminatory intentions in 1901.

On this point, we have the authority of Keyes v. School District

No. 1, supra, cited by the Supreme Court in Davis for the

instruction it gives on the meaning of purpose or intent to

discriminate. 44 U.S.L.W. at 4792. In the context of school

desegregation, Keyes holds:

a finding of intentional segregation ... in

one portion of a school system is highly

relevant to the issue of the board's intent

with respect to the other segregated schools

in the system. This is merely an application

of the well-settled evidentiary principle that

"the prior doing of other similar acts, whether

clearly a part of a scheme or not, is useful as

reducing the possibility that the act in question

was done with innocent intent." 2 J. Wigmore,

Evidence 200 (34 Ed. 1940). ... Similarly, a

finding of illicit intent as to a meaningful

portion of the item under consideration has

substantial probative value on the question of

illicit intent as to the remainder.

»

413 U.S. at 207-08. The analogy to the instant case is clear.

The admitted discriminatory state intent connected with the

1901 constitution, which established a part of the system

for electing Mobile City officers, "creates a presumption”

that the 1911 Act, which further diluted black voting strength

in the same election system, was ''mot adventitious." Keyes

v. School District No. 1, supra, 413 U.S. at 208." At the

very least, these historical circumstances shift the burden

of proof to the defendants to prove conclusively that racial

intent had no part in Mobile's adoption of the at-large election

system.

This burden-shifting principle is not new

or novel. There are no hard-and-fast standards

governing the allocation of the burden of proof

in every situation. The issue, rather, "is

merely a question of policy and fairness based

on the experience in the different situations."

9 J. Wigmore, Evidence §2486, at 275 (3d Ed.

1940).

Keves, supra, 413 U.8. at 209,

Neither can the defendants successfully contend that,

although the at-large system was devised during a time when

black citizens were being intentionally disenfranchised, the

system is being used today for completely non-racial reasons.

In the first place, the evidence shows that the white-dominated

legislature of Alabama and the white officers of the City of

Mobile are entirely aware of the diluting effect the present

system has on the voting strength of black Mobilians. The

continuing use of racist campaign literature in light of

racially polarized voting patterns cannot be ignored by this

Court. And in the second place, Keyes teaches, again in the

-0~

—

context of school desegregation:

If the actions of school authorities were

to any degree motivated by segregative intent

and the segregation resulting from those actions

continues to exist, the fact of remoteness in

time certainly does not make those actions any

less "intentional."

«+ +» . [Alt some point in time the relation-

ship between past segregative acts and present

segregation may become so attenuated as to be

incapable of supporting a finding of de jure

segregation warranting judicial intervention.

- + « We made it clear, however, that a

connection between past segregative acts and

present segregation may be present even when -

not apparent and that close examination is

required before concluding that the connection

does not exist. Intentional school desegregation

in the past may have been a factor in creating

a natural environment for the growth of further

segregation. Thus, if respondent School Board

cannot disprove segregative intent, it can

rebut the prima facie case only by showing that

its past segregative acts did not create or

contribute to the current segregated condition

of the Core City Schools.

413 U.S. at 210-11. Again, the same analysis applied in the

context of Mobile's voter discrimination is precisely that

made by plaintiffs in this action. Our case is based on a

showing that past official disenfranchisement has created

"a natural environment for the growth of further [dis-

crimination]" in that the at-large election system instituted

in the past contributes to current black vote dilution.

The defendants cite Wallace v. House, Supra, 515 F:Z24 at

633, as Fifth Circuit judidical recognition that, with respect

to a statute similar to Act 281, "there could have been no

thought that the device was racially discriminatory, because

10

$

»

few blacks were allowed to vote in Louisiana during

that period.” However, defendants failed to complete the

context in which the Fifth Circuit is quoted:

We would be callous indeed to tell

plaintiffs that seventy years of illegality

somehow legitimizes continued dilution of

black voting rights, but that is not the

thrust of our discussion. In order for there

to be substantial -- an thus illegal --

impairment of minority voting rights, there

must be some fundamental unfairness in the

electoral system, some denial of fair

representation to a particular class.

515 F.2d at 619. Wallace goes on to hold that a reapportion-

ment plan that preserves just one at-large position is not

"fundamentally unfair" in light of the absence of racial

motivation in Louisiana's at-large municipal election system.

Of course, even this one at-large position has been questioned

by the Supreme Court, who vacated Wallace v. House, supra,

44 U.8.1.W. 3607 (26 April 1976), for reconsideration in light

of the single-member district preference expressed in Connor v.

Johnson, 402 U.S. 690,692 (1971), and East Carroll Parish

School Board v. Marshall, b.8. ,"96 8.Ct. 1083 (1976).

iY.

Discriminatory Intent Is Shown Under

The Traditional Tort Standard

Washington v. Davis, supra, also makes clear that a

Watergate-like "smoking gun" need not now be produced to show

discriminatory intent any more so than in the past. Justice

White's majority opinion includes the following priviso:

Il

|

#

This is not to say that the necessary

discriminatory racial purpose must be

expressed or appear on the face of the statute,

or that a law's disproportionate impact is

irrelevant in cases involving Constitution-

based claims of racial discrimination. A

statute, otherwise neutral on its face, must

not be applied so as invidiously to dis-

criminate on the basis of race. Yick Wo v.

Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886).

44 U.S.L.W. at 4792. In his concurring opinion, Justice

Stevens gave his version of this point:

Frequently the most probative evidence of

intent will be objective evidence of what

actually happened rather than evidence

describing the subjective state of mind of

the actor. For normally the actor is presumed

to have intended the natural consequences of

his deeds. This is particularly true in the

case of governmental action which is frequently

the product of compromise, of collective decision-

making, and of mixed motivation.

44 U.S.L.W. at 4800 (emphasis added).

The law in this Circuit squarely adopts the aforesaid

"tort" standard of proving intent. Keyes v. School District

No. 1, supra, relied on so heavily in Washington v. Davis,

supra, has already been interpreted at length by the Fifth

Circuit with respect to the meaning of requisite discriminatory

intent in constitutional cases. As a result of Keyes, the

Fifth Circuit has for several years been requiring "proof of

segregatory intent as a part of state action" in school

desegregation findings. Morales v. Shannon, 516 F.2d 411, 412-

13 (5th Cir.), cexrr.denied, 96 8.Cc. 566 (1975). Most recently,

citing Morales, supra; Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent

School District, 467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972) (en banc), cert.

denied, 413 U.S. 920 (1973); and United States v. Texas

Education Agency, 467 F.2d 848 (5th Cir. 1972) (en banc), the

Fifth Circuit squarely addressed the meaning of discriminatory

intent:

Whatever may have been the originally

intended meaning of the tests we applied

in Cisneros and Austin I [United States

v. Texas Education Agency, supra], we agree

with the intervenors that, after Keyes, our

two opinions must be viewed as incorporating

in school segregation law the ordinary rule of

tort law that a person intends the natural *

and foreseeable consequences of his actions. .

Apart from the need to conform Cisneros

and Austin I to the supervening Keyes case,

there are other reasons for attributing

responsibility to a state official who should

reasonably foresee the segregative effects of

his actions. First, it is difficult -- and

often futile -- to obtain direct evidence of

the official's intentions. ... Hence, courts

usually rely on circumstantial evidence to

ascertain the decision makers' motivations.

United States v. Texas Education Agency (Austin Independent

School District), 532 F.2d 380, 388 (5th Cir. 1976) (Austin

II) (footnotes omitted). There is no reason to distinguish

a school desegregation case from a voter discrimination case

in the context of Washington v. Davis' underlying inquiry into

discriminatory intent.

There can be no serious question by anyone that the evidence

in this case will demonstrate defendants’ discriminatory

intent to discriminate against Mobile's black voters according

to the tort standard. The statistical analyses of racial

vote polarization, documentary evidence of racial appeals:

to the electorate and the abundant testimony of Mobile's

politicans conceding the inability of black candidates to

win in at-lavge elections in Mobile are matters of which the

defendants have long been fully aware. This Court should

hold that defendants have intended the natural and foreseeable

consequences of this racially discriminatory election system.

Conclusion

When Act 281 was passed in 1911, it became part of an

overall electoral scheme in Alabama that was unquestionably

designed and had the effect of disenfranchising black citizens.

There is even some evidence that the legislators and political

leaders of Mobile were consciously aware of the dilution factor

the at-large system would add to the overall scheme. In any

event, as a matter of law, the discriminatory intent of 1901

is presumed to attach to the state's action in 1911 when it

enacted Act No. 281. The defendants must show by conclusive

proof that there was no racially discriminatory motive behind

Act 281.

Furthermore, the evidence in this case will show that

the state plainly intended to dilute the voting strength of

black Mobilians as a natural and foreseeable consequence of

imposing an at-large election system, a consequence that has

frequently and dramatically demonstrated over the past

fifteen years.

Read in light of the Supreme Court and Fifth Circuit

authorities cited in this brief, it can be seen that the

dilution factors set out in Zimmer wv. McKeithen, supra, are

actually indicia of both discriminatory effect and dis-

criminatory intent, actual and constructive.

Respectfully submitted this 9th day of July, 1976,

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIGURES & BROWN

1407 DAVIS AVENUE

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36603

wr lg fol foflnr

./ U.” BLACKSHER

RRY MENEFEE

EDWARD STILL, ESQUIRE

SUITE 601 - TITLE BUILDING

2030 THIRD AVENUE, NORTH

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA 35203

JACK GREENBERG, ESQUIRE

CHARLES WILLIAMS, III., ESQUIRE

SUITE 2030

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE

NEW YORK, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that on this the 9th day of July,

I served a copy of the foregoing PLAINTIFFS’ PRETRIAL

I upon counsel of record, Charles A. Arendall, Esquire,

agwell, Esquire, Post Office Box 123, Mobile,AL and

S. R. Shes ¢, Esquire, City of Mobile, Legal Department,

Post Office Box 1827, Mobile, AL 36601, by depositing same

in United States Mail, postage prepaid or by HAND DELIVERY.

dt 2. Lede:

Ofney for Plaintiffs