Goosby v. Hempstead, New York Town Board Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 26, 1998

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goosby v. Hempstead, New York Town Board Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Appellees, 1998. b8a077d8-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9dff6695-93de-44ca-8d5d-09af43ec2e20/goosby-v-hempstead-new-york-town-board-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

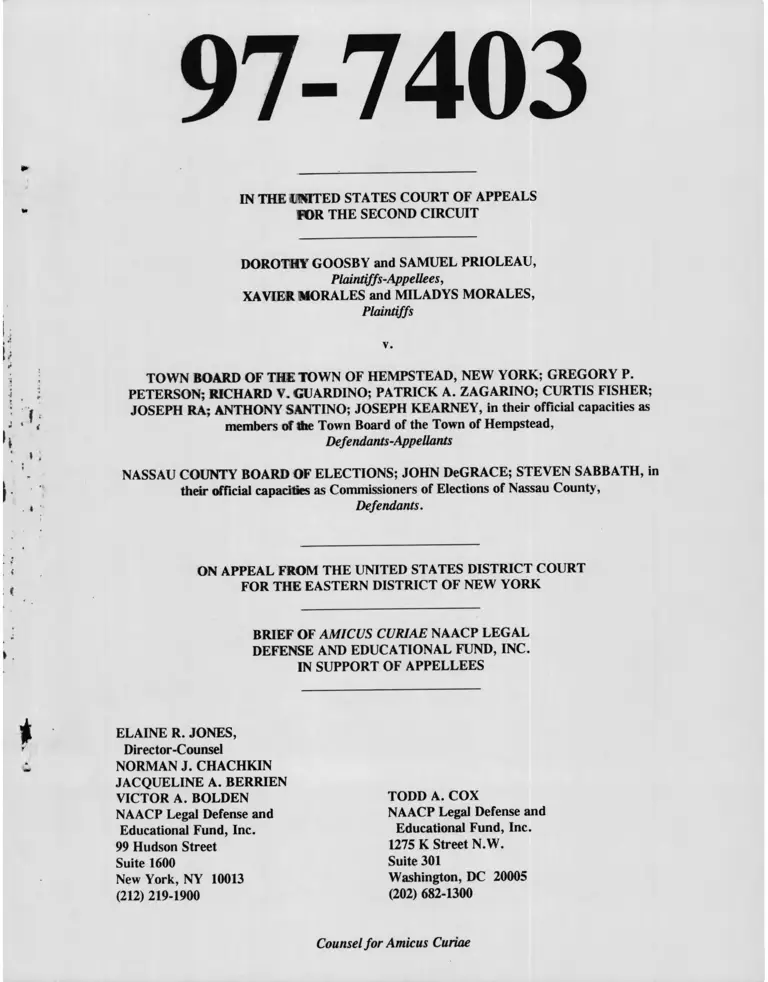

97-7403

IN THE tfWTED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

DOROTHY GOOSBY and SAMUEL PRIOLEAU,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

XAVIER MORALES and MILADYS MORALES,

Plaintiffs

v.

T O W N BOARD OF THE T O W N OF HEMPSTEAD, N E W YORK; GREGORY P.

PETERSON; RICHARD V. GUARDINO; PATRICK A. ZAGARINO; CURTIS FISHER;

JOSEPH RA; ANTHONY SANTINO; JOSEPH KEARNEY, in their official capacities as

members of the Town Board of the Town of Hempstead,

Defendants-Appellants

NASSAU COUNTY BOARD OF ELECTIONS; JOHN DeGRACE; STEVEN SABBATH, in

their official capacities as Commissioners of Elections of Nassau County,

Defendants.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF N E W YORK

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES

ELAINE R. JONES,

Director-Counsel

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

JACQUELINE A. BERRIEN

VICTOR A. BOLDEN

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

TODD A. COX

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................................

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ...................................

ARGUMENT ..............................................

I . The Language of Section 2 and the Decisions of the United

States Supreme Court and This Court Foreclose Defendants-

Appellants' Contention That Because Most Black Hempstead

Voters Are Democrats and A Majority of White Hempstead

Voters Are Republicans, A Violation Of Section 2 Cannot

Be Established......................................

II. Even If Partisan Political Behavior Is Relevant To The

Section 2 Inquiry, The Court Below Correctly Concluded

That Evidence Concerning Partisan Voting Patterns In

Hempstead Was Insufficient To Counteract The Extensive

Evidence Of Electoral Discrimination Which Plaintiffs

Presented..........................

CONCLUSION ...........

jL

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Baird v. Consolidated City of Indianapolis,

976 F.2d 357 (7th Cir. 1 9 9 2 ) ................... 20, 21, 22

Bridgeport Coalition v. City of Bridgeport,

26 F.3d 271 (2nd Cir. 1994) ....................n f 14; 15

Bush v. Vera,

116 S. Ct. 1941 (1996)................................... !

Butts v. City of New York,

779 F . 2d 141 (2nd Cir. 1 9 8 5 ) ............................ 24

Chisom v. Roemer,

501 U.S. 380 (1991) ..................................... 5

City of Mobile v. Bolden,

446 U.S. 55 (1982)..................................... 2, 4

Clark v. Calhoun County,

21 F . 3d 92 (5th Cir. 1 9 9 4 ) .............................. 7

Goosby v. Town Bd. of the Town of Hempstead,

956 F. Supp. 326 (E.D.N.Y. 1 9 9 7 ) ....................passim

Houston Lawyers' Association v. Attorney General of Texas,

501 U.S. 419 (1991) .............................. 1, 8, 12

Jenkins v. Red Clay Consol. Sch. Dist. Bd. of Ed.,

4 F .3d 1103 (3rd Cir. 1993), cert, denied, 114 S.

Ct. 2779 (1994) ..................................... 7, 28

Johnson v. DeGrandy,

512 U.S. 997 (1994) .................................passim

League of United Latin American Citizens, Council No.

4434 v. Clements,

999 F.2d 831 (5th Cir. 1993), cert, denied,

510 U.S. 1071 (1994) .............................. passim

Lewis v. Alamance County,

99 F . 3d at 6 1 5 ...............................................

Milwaukee Branch N.A.A.C.P. v. Thompson,

116 F . 3d 1194 (7th Cir. 1997) .......................... 12

NAACP v. Button,

371 U.S. 415 (1963) ..................................... 1

i

N.A.A.C.P. v. City of Niagara Falls,

65 F.3d 1002 (2nd Cir. 1 9 9 6 ) ........................ passim

Rangel v. Morales,

8 F . 3d 242 (5th Cir. 1 9 9 3 ) .............................. 26

Sanchez v. Colorado,

97 F . 3d 1303 (10th Cir. 1996) ......................passim

Shaw v. Hunt,

116 S. Ct. 1894 (1996)................................... 1

Solomon v. Liberty County,

957 F. Supp. 1522 (N.D. Fla. 1 9 9 7 ) ...................... 6

Southern Christian Leadership Conference v. Sessions,

56 F .3d 1281 (11th Cir. 1995), cert, denied, 116 S.

Ct. 704 (1996)............................................ 20

Thornburg v. Gingles,

478 U.S. 30 (1986)..................................... passim

United States v. Hays, 515,

515 U.S. 737 (1995) 1

United States v. Marengo County Comm'n,

731 F .2d 1546 (11th Cir.), cert, denied, 469 U.S.

976 (1984)................................................ 19

Vecinos de Barrio Uno v. City of Holyoke,

72 F . 3d 973 (1st Cir. 1995) ........................ 10, 17

Voinovich v. Quilter,

507 U.S. 146 (1993) 5

Westwego Citizens for Better Government v. City of Westwego,

946 F . 2d 1109 (5th Cir. 1991) .......................... 28

Whitcomb v. Chavis,

403 U.S. 124 (1971) ................................. 6, 20

Zimmer v. McKeithen,

485 F . 2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) .......................... 8

ii

STATUTES

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,

42 U.S.C. § 1973 ..................................... passim

Senate Report No. 97-417, 97th Cong., 2d

Sess., reprinted in 1982 U.S.C.C.A.N. 177 ........... 4, 8

Voting Rights Act: Hearings on S . 53, S. 1761, S. 1975,

S. 1992, and H.R. 3112 Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution of the Senate Comm, on the Judiciary,

97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982) ............................ 2

Voting Rights Act: Hearings on S . 53, S. 1761, S. 1975,

S. 1992, and H.R. 3112 ................................. 2

iii

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. ("LDF") is

a nonprofit corporation chartered by the Appellate Division of the

New York Supreme Court as a legal aid society. The Legal Defense

Fund's first Director-Counsel was Thurgood Marshall. Since its

inception in 1939, LDF has been committed to enforcing legal

protections against racial discrimination and securing the

constitutional and civil rights of African-Americans. See NAACP v.

Button, 371 U.S. 415, 422 (1963) (describing Legal Defense Fund as

a "'firm' . . . which has a corporate reputation for expertness in

presenting and arguing the difficult questions of law that

frequently arise in civil rights litigation").

LDF has an extensive history of participation in efforts to

eradicate barriers to the full political participation of African-

Americans and to eliminate racial discrimination in the political

process. LDF has represented parties or participated as amicus

curiae in numerous voting rights cases before the United States

Supreme Court and the United States Courts of Appeals. See, e.g.,

Bush v. Vera, 116 S. Ct. 1941 (1996); Shaw v. Hunt, 116 S. Ct. 1894

(1996); United States v. Hays, 515 U.S. 737 (1995); League of

United Latin American Citizens, Council No. 4434 v. Clements, 999

F.2d 831 (5th Cir. 1993) (en banc), cert, denied 510 U.S. 1071

(1994); Chisom v. Roemer, 501 U.S. 380 (1991); Houston Lawyers'

Association v. Attorney General of Texas, 501 U.S. 419 (1991); and

1

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986). In addition, LDF

advocated for the legislative reversal of the decision in Mobile v.

Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980), which was achieved through the 1982

amendments to Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. See

Voting Rights Act: Hearings on S. 53, S. 1761, S. 1975, S. 1992,

and H.R. 3112 Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the Senate

Comm, on the Judiciary, 97th Cong. 1251-68 (1982) (statement of

Julius L. Chambers, President of the NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.)

Because of its longstanding commitment to the elimination of

racial discrimination in the political process and the protection

of the voting rights of African Americans, LDF has an interest in

this appeal, which presents important issues concerning the

interpretation and application of Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973.

STANDARD OF REVIEW

The district court's ultimate finding of vote dilution, and

its resolution of all subsidiary factual issues should be affirmed

unless they are "clearly erroneous. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S.

30, 78-79 (1986); accord N.A.A.C.P. v. City of Niagara Falls, 65

F • 3d 1002, 1008. The district court's "application of legal

standards in reaching its finding is subject to de novo review."

N.A.A.C.P. v. City of Niagara Falls, id.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Amicus adopts the Plaintiffs-Appellees' Counterstatement of

Facts.

2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Dorothy Goosby and Samuel Prioleau, African-American citizens

and registered voters of the town of Hempstead, New York,

successfully challenged the at-large system used to elect the

members of the Town Board of Hempstead on the ground that it

diluted minority voting strength in violation of Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973. See generally Goosby

v. Town of Hempstead, 956 F. Supp. 326 (E.D.N.Y. 1997). The Town

Board of Hempstead and its individual members acting in their

official capacities urge this Court to reverse the decision of the

district court.

The Defendants-Appellants do not dispute the district court's

findings that voting in the Town of Hempstead is racially

polarized; however, Defendants-Appellants assert that this

racially polarized voting is the product of partisan politics, and

is thus exempt from challenge under Section 2. See generally Brief

of— Def endants - Appellant s at 13-45.1 There is no support in the

language of Section 2, its legislative history, or the judicial

decisions interpreting the statute, for the Defendants-Appellants'

position, however.

Confronted with a clear statistical showing of persistent

racially polarized voting, the district court correctly found that

legally significant white bloc voting exists in Hempstead. In the

face of undisputed evidence concerning racial differences in

lpor ease of reference, this argument will sometimes be

referred to as the "partisanship defense."

3

candidate choices in Hempstead elections, the Defendants-Appellants

could not eliminate racial considerations as an explanation for

racially divergent voting patterns. The Defendants-Appellants

offered no objectively verifiable analysis to support their

contention that partisan politics were responsible for the proven

racially polarized voting in Hempstead, nor did they rebut the

compelling evidence of racial discrimination in the political

process which the Plaintiffs-Appellees presented below.

The district court engaged in the "searching evaluation" of

the evidence that is required in a Section 2 case,2 and it

thoroughly considered the partisanship defense presented by the

Town of Hempstead. However, the Court ultimately concluded --as

it was compelled to do on the basis of the record before it -- that

plaintiffs had shown, under the totality of circumstances present

in the Town of Hempstead, that African-American voters have less

opportunity to participate in the political process and elect their

preferred candidates to the Town Board than white voters enjoy

under the at-large election system.

ARGT7MKNT

I. The Language of Section 2 and the Decisions of the United

States Supreme Court and This Court Foreclose Defendants-

Appellants' Contention That Because Most Black Hempstead

Voters Are Democrats and A Majority of White Hempstead Voters

Are Republicans, A Violation Of Section 2 Cannot Be

Established.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973,

was enacted "to help effectuate the Fifteenth Amendment's guarantee

2S. Rep. No. 97-417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 30 (1982) (citation

and internal quotation omitted).

4

that no citizen's right to vote shall 'be denied or abridged

on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,'"

Voinovich v. Quilter, 507 U.S. 146, 152 (1993) (quoting U.S.

Const., 15th Amendment). Section 2 was amended by Congress in 1982

to expressly prohibit electoral practices and procedures with

racially discriminatory results. Amended Section 2 "prohibits any

practice or procedure that, 'interact[ing] with social and

historical conditions,' impairs the ability of a protected class to

elect its candidate of choice on an equal basis with other voters."

Voinovich at 153, quoting Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 47

(1986) . Since the Voting Rights Act was enacted "for the broad

remedial purpose of 'rid(ding] the country of racial discrimination

in voting' . . . [it] . . . should be interpreted in a manner that

provides "the broadest possible scope' in combatting racial

discrimination." Chisom v. Roemer, 501 U.S 380, 403 (1991) (quoting

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 315 (1966)); Allen v.

State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 567 (1969).

As amended, Section 2(b) of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973(b) authorizes a court to provide relief when, "based on the

totality of the circumstances, it is shown that . . . members of a

class of citizens protected by subsection (a) have less

opportunity than other members of the electorate . . . to elect

representatives of their choice." The Act provides no exception

from its reach in circumstances where minority and non-minority

5

voters have different partisan political preferences.3 Nor does

the legislative history support such an assertion. See Solomon v.

Liberty County, 957 F. Supp. 1522, 1544-45 (N.D. Fla. 1997)

("although the Senate Report makes repeated references to Whitcomb

[v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971)] and White [v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755 (1973)], nowhere does it state that a section 2 plaintiff must

demonstrate intentional discrimination," a factor not contained

within the Act, but arguably required by Whitcomb) .

Section 2, as amended, was first construed by the United

States Supreme Court in Thornburg v. Gingles, a lawsuit which

challenged multimember legislative election districts in North

Carolina on the ground that they diluted the voting strength of the

state's African-American citizens. In Gingles, the Supreme Court

held that Section 2 plaintiffs must prove (1) that the minority

group "is sufficiently large and geographically compact to

defendants-Appellants argue that because Congress' broad goal

in modifying the Act in 1982 was to restore the law as it existed

prior to City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1982), amended

Section 2 must be read to implement their reading of the Supreme

Court's holding in Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971). That

case, they assert, rules out a finding of violation if African-

American and white voters are adherents of different political

parties. See, e.g., Defendants-Appellants' Brief at 21-23, 33-34

71-74.

Even assuming arguendo that this interpretation of Whitcomb is

correct, but see Solomon v. Liberty County, 957 F. Supp. 1522, 1544

n. 39 (N.D. Fla. 1997) quoting League of United Latin American

Citizens ̂ ["LULAC"] v. Clements, 999 F.2d 831, 900, 907 (5th Cir.

1993) (King, J., dissenting), cert, denied, 510 U.S. 1071, 114 S.

Ct. 878 (1994), the means chosen by Congress to achieve its goal

are encompassed within the language of the Act, which nowhere

incorporates Whitcomb. Moreover, as we demonstrate infra, the

interpretation of Whitcomb promoted by the defendants-appellants is

inconsistent with the Supreme Court's construction of amended

Section 2 in Gingles and subsequent decisions.

6

constitute a majority in a single member district"; (2) that the

minority group is "politically cohesive"; and (3) that the white

majority "votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it -- in the

absence of special circumstances . . . usually to defeat the

minority's preferred candidate." Gingles, 478 U.S. at 50-51. More

recently, in Johnson v. DeGrandy, 512 U.S. 997, 1010-11 (1994), the

Supreme Court observed that:

Gingles provided some structure to the

statute's 'totality of circumstances' test . .

[T] he three now-familiar Gingles factors

(compactness/numerousness, minority cohesion

or bloc voting, and majority bloc voting) . .

[were identified] as 'necessary

preconditions' . . . for establishing vote

dilution by use of a multimember district.

But if Gingles so clearly identified the

three [factors] as generally necessary to

prove a § 2 claim, it just as clearly declined

to hold them sufficient in combination, either

in the sense that a court's examination of

relevant circumstances was complete once the

three factors were found to exist, or in the

sense that the three in combination

necessarily and in all circumstances

demonstrated dilution.

See also N.A.A.C.P. v. City of Niagara Falls, 65 F.3d 1002, 1008

(2nd Cir. 1995) (proof of the Gingles factors is "'generally

necessary' to prove a § 2 violation . . . [but it is] not

sufficient" to prove a violation) (citation omitted),4 Thus,

4But see N.A.A.C.P. v. City of Niagara Falls, 65 F.3d 1002,

1019-20 n . 21 ("We agree . . . that 'it will be only the very

unusual case in which the plaintiffs can establish the existence of

the three Gingles factors but still have failed to establish a

violation of § 2 under the totality of circumstances'") (quoting

Jenkins v. Red Clay Consol. Sch. Dist. Bd. of Educ., 4 F.3d 1103,

1135 (3d Cir. 1993), cert, denied U.S. , 114 S. Ct. 2779

(1994); accord Clark v. Calhoun County, 21 F. 3d 92, 97 (5th Cir

1994) .

7

Section 2 plaintiffs must show that under the "totality of the

circumstances"5 present in the jurisdiction, they have less

opportunity to participate in the political process and elect their

preferred candidates than white voters enjoy.

The "authoritative source" for interpreting amended Section 2

is Senate Report No. 97-417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted in

1982 U.S.C.C.A.N. 177. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 43 n.7 (1986). The

Senate Report discusses the types of evidence which Congress

considered to be relevant to the ultimate determination of a

Section 2 violation, and which are considered by courts as part of

their evaluation of the totality of the circumstances. These

factors, also known as the "Senate Report factors,"6 are:

1. the extent of any history of official

discrimination in the state or political

subdivision that touched the right of the

members of the minority group to register, to

vote, or otherwise to participate in the

democratic process;

2• the extent to which voting in the

elections of the state or political

subdivision is racially polarized;

3. the extent to which the state or political

subdivision has used unusually large election

districts, majority vote requirements, anti

single shot provisions,- or other voting

practices or procedures that may enhance the

opportunity for discrimination against the

minority group,-

4. if there is a candidate slating process,

whether the members of the minority group have

been denied access to that process,-

5. the extent to which members of the

542 U.S.C. § 1973(b).

6The Senate Report factors were derived from the factors

identified as relevant to a vote dilution claim in the opinion of

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in Zimmer

v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297, 1305 (5th Cir. 1973).

8

minority group in the state or political

subdivision bear the effects of discrimination

in such areas as education, employment and

health, which hinder their ability to

participate effectively in the political

process;

6. whether political campaigns have been

characterized by overt or subtle racial

appeals;

7. the extent to which members of the

minority group have been elected to public

office in the jurisdiction.

Additional factors that in some cases have had

probative value as part of plaintiff's

evidence to establish a violation are: whether

there is a significant lack of responsiveness

on the part of elected officials to the

particularized needs of members of the

minority group. . . . [and] whether the policy

underlying the state or political

subdivision's use of such voting

qualification, prerequisite to voting, or

standard, practice or procedure is tenuous.

S. Rep. No. 97-417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. at 28-29 (1982).

When the United States Supreme Court initially construed the

1982 amendment in Gingles, it excluded from the analysis relevant

to the third prerequisite (white bloc voting) any causal inquiry

relating to voting patterns. See Solomon, 957 F. Supp. at 1545-46

(Gingles Court's acceptance of bivariate ecological regression and

extreme case analysis as sufficient to demonstrate white bloc

voting negates causal inquiry) ,7 Nevertheless, Defendants-

Appellants contend that Plaintiffs-Appellees should have been

"require[d] to tie the defeat of black-supported Democrats to

race<" Defendants-Appellants' Brief at 18. The Defendants-

7See also S. Rep. No. 97-417 at 36 (noting Congress' desire to

eliminate requirement of proof of discriminatory intent in

challenges filed under amended Section 2 on the ground that intent

evidence is "unnecessarily divisive because it involves charges of

racism on the part of individual[s or] . . . communities")

9

Appellants also contend that a "political explanation for why

candidates supported by a majority of blacks lose . . . must be

given dispositive weight when deciding whether blacks have less

political opportunity than others 'on account of race.'" Id. at 72

(quoting Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 153 (1971).

The appellate courts that have addressed this issue have

rejected the position urged by Defendants-Appellants here, and for

good r e a s o n -- it is wholly inconsistent with the language of

Section 2, the legislative history, and the decisions of the

Supreme Court. The en banc opinion of the Fifth Circuit in LULAC

v. Clements, which defendants-appellants cite repeatedly in support

of their argument, in fact offers no support for their extreme

position. In LULAC, the en banc Fifth Circuit Court held that

minority voters' overwhelming affiliation with the Democratic party

was the best explanation for the defeat of minority-preferred

judicial candidates in the Texas judicial elections at issue.

However, contrary to the position advanced by Defendants-Appellants

here, the LULAC Court did not adopt a blanket rule that a

"partisanship" defense precludes plaintiffs from proving the third

G'ingles precondition or necessarily rebuts all other evidence which

demonstrates that under the totality of circumstances, minority

voters have less opportunity to participate in the political

process and to elect their preferred candidates than white voters.

See also Uno v. City of Holyoke, 72 F.3d 973, 983 (1st Cir. 1995)

(evidence that racially polarized voting "can most logically be

explained by factors unconnected to the intersection of race with

10

the electoral system . . . does not automatically [result in a

victory for the defendants]. Instead, the Court must determine

whether, based on the totality of circumstances, the plaintiffs

have proven that the minority group was denied meaningful access to

the political system on account of race").

As discussed more fully infra in Part II, the factual

circumstances relating to partisan affiliation and identification

in Texas, which the Court addressed in LULAC, are significantly

different from the situation in the Town of Hempstead; a mechanical

application of the LULAC holding to the Hempstead facts would

violate the requirement that judicial analysis of Section 2

evidence must encompass an "intensely local appraisal" of the

political life of the defendant jurisdiction. Gingles, 478 U.S. at

78; Bridgeport Coalition v. City of Bridgeport, 26 F.3d 271, 275

(2nd Cir. 1994). Moreover, the LULAC Court explicitly held that

a correlation between the partisan affiliation and race of voters

in a jurisdiction neither automatically precludes a finding of

legally significant racially polarized voting nor necessarily

negates an ultimate finding of vote dilution:

[W] e recognize that . . . partisan affiliation

may serve as a proxy for illegitimate racial

considerations. . . . Plaintiffs are . . .

entirely correct in maintaining that courts

should not summarily dismiss vote dilution

claims in cases where racially divergent

voting patterns correspond with partisan

affiliation as "political defeats" not

cognizable under § 2.

LULAC, 999 F.2d at 860-61.

Other federal appellate courts have similarly rejected the

11

position urged by the Defendants-Appellants here. For example, in

Lewis v. Alamance County, the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit rejected this argument, holding that the issue

of causation of racially polarized voting is "irrelevant in the

inquiry into the three Gingles preconditions," 99 F.3d 600, 615

n . 12 (4th Cir. 1996), cert, denied 65 U.S.L.W. 3766 (1997). See

also Sanchez v. Colorado, 97 F.3d 1303, 1313 "(10th Cir. 1996) ("at

the threshold, we are simply looking for proof of the correlation

between the race of the voter and the defeat of the minority's

preferred candidate"); id., at 1315-16 (examination of "'the

reasons for, or causes of, voting behavior' . . . . [is] not

relevant" at the threshold stage of the § 2 inquiry) ; cf. Milwaukee

Branch N.A.A.C.P. v. Thompson, 116 F.3d 1194, 1199 (7th Cir. 1997)

("A district judge should not assign to plaintiffs the burden of

showing why the candidates preferred by black voters lost; it is

enough to show that they lost, if white voters disapproved these

candidates en masse") (emphasis in original). The court below thus

properly refused to consider information concerning the

relationship between the race and partisan affiliation of

Hempstead's voters as part of its analysis of the third Gingles

factor.

However, the district court considered this information as

part of its evaluation of the "totality of circumstances." Cf.

Lewis v. Alamance County, 99 F.3d at 615 n.12 (causation evidence

is "relevant in the totality of the circumstances inquiry");

Sanchez v. Colorado, 97 F.3d at 1313 ("[T]he searching evaluation

12

done in the totality of circumstances perhaps reveals" voters'

motivations for their decisions at the polls) . As part of its

consideration of the "totality of the circumstances" in this case,

the district court thoroughly considered the partisanship defense

presented by the Town of Hempstead, but it ultimately concluded --

as it was compelled to do on the basis of the record before it --

that plaintiffs had shown, under the totality of circumstances

present in the Town of Hempstead, that African-American voters have

less opportunity to participate in the political process and elect

their preferred candidates to the Town Board than white voters

enjoy under the challenged election system.

Comprehensive examination of the facts is precisely what the

"totality of circumstances" requirement of Section 2 demands;

nevertheless Defendants-Appellants have invited this Court to

ignore the full array of evidence presented here by arguing that

the existence of partisan differences between the majority of black

voters and the majority of white voters trumps all other evidence

in the "totality of circumstances" calculus. Again, this approach

is plainly wrong under governing authority.

The Supreme Court has consistently held that plaintiffs are

not required to prove any particular Senate Report factor or

combination of factors in order to prevail in a Section 2 case.8

Conversely, no single factor is to be accorded decisive weight in

the Section 2 calculus. See, e.g., Houston Lawyers Association,

Moreover, as the Supreme Court noted in Gingles, "the list of

[Senate Report] factors 'is neither comprehensive nor exclusive

478 U.S. at 45 .

13

501 U.S. at 426 (noting that state's interest in maintaining at-

large system for the election of trial judges "is merely one factor

to be considered in evaluating the 'totality of circumstances'";

cf. Johnson v. DeGrandy, 512 U.S. at 1026 (O'Connor, J.,

concurring) ("[C]ourts must always carefully and searchingly review

the totality of the circumstances, including the extent to which

minority groups have access to the political process"). See also

Sanchez v. Colorado, 97 F.3d at 1324 ("Each facet [of evidence]

must be considered under the totality, and the absence of one

factor doesn't necessarily cancel out the presence of another").

The district court correctly held that

neither the existence (or non-existence) of

racial bias in the community nor the strength

of the correlation between partisan politics

and divergent voting patterns can be

dispositive in a Section 2 case. Rather, they

are simply among the many factors to be

considered in determining whether, under the

totality of the circumstances, an at-large

scheme has impaired the ability of black

voters in the Town to participate equally in

Town Board elections.

956 F. Supp. 326, 352-53 (citations omitted). Despite the clear

admonition of the Supreme Court that the Section 2 inquiry should

never be limited to a single factor, Defendants-Appellants have

urged this Court to adopt precisely such an approach. See, e.g.,

Defendants-Appellants' Brief at 36 ("[A]n inquiry through the

totality of the circumstances for the reasons for white voter

rejection of minority-preferred candidates is unnecessary where the

pattern of the vote is partisan. . . . The undisputed evidence

regarding the partisan pattern of the vote here is dispositive of

14

plaintiffs' vote dilution claim.") (emphasis supplied); id., at 70

("Even assuming that the District Court's conclusions were correct

on the existence of racial appeals, the exclusion of blacks from

the Republican Party slating process, and insensitivity of the Town

officials to black concerns, these factors neither singularly nor

in combination establish that racial concerns, rather than partisan

ones, have led to the defeat of candidates supported by the black

electorate or have led to any inability of blacks to participate

equally in the political process").

The district court did not disregard Defendants-Appellants'

argument that partisan affiliation, rather than race, accounts for

the consistent defeat of African-American candidates in the Town of

Hempstead. Rather, the court considered this information in

precisely the manner that it was required to under Gingles,

DeGrandy, and other binding precedents: as one -- but only one --

factor in the assessment of the totality of circumstances present

in Hempstead's political sphere. The district court did not treat

Appellant's argument as the trump to all other proof presented by

the plaintiffs, and it correctly recognized that elevating the

partisanship explanation to the level of importance urged by the

Appellants would vitiate and undermine the results standard set

forth in amended Section 2. Its decision should be affirmed.

Defendants-Appellants' attempt to elevate the partisanship issue

above every other single or combined element of the totality of

circumstances analysis is clearly prohibited by Gingles and

DeGrandy.

15

Not only is the approach promoted by the Defendants-Appellants

in conflict with Supreme Court precedent, it is also at odds with

the decisions of this Court. In N.A.A.C.P. v. City of Niagara

Falls, this Court, citing Gingles and DeGrandy, reaffirmed the

importance and necessity of a comprehensive judicial inquiry in

Section 2 cases:

[I]n deciding whether § 2 has been violated,

courts are to engage in a "searching and

practical evaluation of the 'past and present

reality'." . . . The Supreme Court recently

emphasized that . . . [c]ourts are required to

look explicitly at the totality of the

circumstances, because "ultimate conclusions

about equality or inequality of opportunity

were intended by Congress to be judgments

resting in comprehensive, not limited,

canvassing of relevant facts."

65 F.3d at 1008 (citations omitted). The district court here

engaged in precisely the "searching and practical evaluation" which

this Court and the Supreme Court demand in a Section 2 case. Its

ultimate finding that the Town of Hempstead's at-large election

system denies the Town's African-American voters an equal

opportunity to participate in the political process and elect their

preferred candidates to the Town Council is well supported by the

record, and should be affirmed.

In Bridgeport Coalition v. City of Bridgeport, 26 F.3d 271 (2d

Cir. 1994), a Section 2 challenge to the reapportionment of the

Bridgeport City Council filed by African-American and Hispanic

registered voters and residents of Bridgeport, Connecticut, this

Court concluded that the "evidence relating to the three .

Gingles factors weighs substantially in favor of the finding of

16

vote dilution." 26 F.3d at 277. This Court also affirmed the

trial court's "findings relating to the history of race relations

in Bridgeport and to the other factors which may be considered as

part of the 'totality of the circumstances' enmeshed with the

voters' rights issues in the City." Id. The evidence presented by

the Plaintiffs-Appellants here was similarly compelling, and the

district court's findings of racially polarized voting are

similarly supported by the record. The factual findings of the

district court were not erroneous and its decision, like the trial

court's decision in the Bridgeport case, should be affirmed by this

Court.

Finally, a decision from the United States Court of Appeals

for the Tenth Circuit is especially instructive concerning the

proper resolution of the issues raised by the Defendants-

Appellants. The Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals confronted -- and

rejected -- the same argument advanced by Defendants-Appellants

here:

Dr. Zax [the defendants' expert witness]

concluded [that] Hispanics vote for Democrats

and Democrats don't beat Republicans in HD 69

Dr. Zax concluded, "political

affiliation is the single most important

factor that distinguishes between the vote

outcomes in precincts that are heavily

Hispanics [sic] and heavily Anglo in House

District 60." . . . [This] inquiry sidesteps

Gingles' primary analytic focus under § 2 . .

[and] in this case, the theory does not

appear to be supported by present or

historical fact.

17

Sanchez v. Colorado, 97 F.3d at 1318.9 Similarly, in this case,

neither "present or historical fact[s]" support the conclusion that

Hempstead's African-American citizens enjoy the same opportunity as

whites to participate in the political process and elect their

preferred candidates to the Town Board. The district court's

finding that Hempstead's at-large election system violates Section

2 of the Voting Rights Act should be affirmed.

II. Even If Partisan Political Behavior Is Relevant To The Section

2 Inquiry, The Court Below Correctly Concluded That Evidence

Concerning Partisan Voting Patterns In Hempstead Was

Insufficient To Counteract The Extensive Evidence Of Electoral

Discrimination Which Plaintiffs Presented.

Appellants in any event failed to show below that the

motivation behind the consistent support that Hempstead's white

electorate has given white-preferred candidates over black-

preferred candidates is attributable to partisan politics. The

district court found:

[T]here is no dispute that every minority-

preferred candidate for Town Council-member

lost to the majority-preferred candidate as a

result of white voters voting for candidates

the black voters did not support.

Accordingly, there is a persistent pattern of

racially polarized voting in Town Board

elections that consistently has resulted (and

will result in the future) in the defeat of

the minority-preferred candidate.

Goosby v. Town Bd. of the Town of Hempstead, 956 F. Supp. 326, 351

(E.D.N.Y. 1997) . Confronted with a clear statistical showing of

persistent racially polarized voting, the district court correctly

9Sanchez was a lawsuit brought by Hispanic plaintiffs which

alleged that the post-1990 Census redistricting of Colorado State

House District 60 diluted Hispanic voting strength, in violation of

Section 2.

18

held that legally significant white bloc voting (the third Gingles

prerequisite) exists in Town Board elections.

Such a statistical showing of racially polarized voting is not

easily overcome when the totality of the circumstances is examined:

[T]his framework imposes a high hurdle for

those who seek to defend the existing system

despite meaningful statistical evidence that

suggests bloc voting along racial lines. See

Jenkins, 4 F.3d at 1135. We predict that

cases will be rare in which plaintiffs

establish the Gingles preconditions yet fail

on a section 2 claim because other facts

undermine the original inference. In this

regard, we emphasize that establishing vote

dilution does not require the plaintiffs

affirmatively to disprove every other possible

explanation for racially polarized voting.

Uno v. City of Holyoke, 12 F.3d 973, 983 (1st Cir. 1995) (footnote

omitted) . Thus, even if it were valid to inquire into the

motivation underlying the voting behavior of Hempstead's

electorate, "[t]he surest indication of race-conscious politics is

a pattern of racially polarized voting." United States v. Marengo

County Comm'n, 731 F.2d 1546, 1567 (llth Cir.), cert, denied, 469

U.S. 976 (1984). In this case, defendants-appellants were unable

to offer any objectively verifiable analysis demonstrating that

partisan affiliation could account entirely for these racially

divergent election results. In fact, courts have accepted

Partisanship as a defense and upheld a challenged plan against a

Section 2 claim only in cases in which partisan preferences could

be identified, through objective, quantifiable proof, as a

consistent factor dominating minority and white voting patterns

over a series of elections.

19

Thus, the Fifth Circuit's decision in LULAC v. Clements, on

which defendants rely, expressly limited attempts to explain away

losses by minority-preferred candidates based on partisanship to

statistically proven straight-ticket partisan voting. in that

case, statistical proof demonstrated that Hispanic voters preferred

Anglo Democrats to Hispanic Republicans, 999 F.2d at 877-878, that

black voters were more likely to support white Democrats than black

Republicans, and that black Republicans were being elected just as

frequently as white Republicans. 999 F.2d at 877-78. In addition,

unlike in the present case, the Court noted the Texas Republican

party's history of recruiting minorities, as well as white,

judicial candidates. Id. at 861.

Similarly, in Baird v. Consolidated City of Indianapolis, 976

F.2d 357 (7th Cir. 1992), the Seventh Circuit recognized that black

voters' preference for white Democrats over black Republicans, and

white voters' preference for black Republicans over white

Democrats, did not alone establish a Section 2 violation, where

black candidates had been able to win seats on the governing body

in proportion to their numbers in the population. Cf. Whitcomb,

403 U.S. at 379, 380 n.29 (noting past electoral success of black

candidates in Marion County, Indiana). In Baird, the court also

found that black voters did not cohesively support black candidates

if they were Republican, and white voters only rejected black

candidates who were Democrats. Id at 361. The Seventh Circuit

held that because the Republican Party dominated council elections

in Indianapolis, and black Republican candidates of that party

20

could win as readily as white Republican candidates, the results

did not necessarily demonstrate racially polarized voting, even if

black voters did not support the successful black Republican

candidates. Id. See also Southern Christian Leadership Conference

v. Sessions, 56 F.3d 1281, 1287-88 (11th Cir. 1995) (en banc),

cert, denied, 116 S. Ct. 704 (1996) (fact that white voters gave

more support to black Democratic candidates than white Democratic

candidates weakened claim of racially polarized voting)

Finally, the court in Baird held that black voters could not

prove vote dilution because the 29-member City-County Council

already included a proportional number of majority-black single

member districts, and black Republicans also had proportional

success in winning even the four at-large council seats that were

the subject of the Section 2 challenge. 976 F. 2d at 360. See

also De Grandy, 512 U.S. at 1012 n.10 (noting that blacks in

Indianapolis enjoyed slightly greater-than-proportional

representation under the plan challenged in Baird) .

There is no similar proof in this case. Unlike LULAC, no

statistical evidence indicated that black voters would prefer white

Democrats to black Republicans in the probative Town Board

elections. There is also no evidence that, before the commencement

of the voting rights lawsuit, the Republican Party actively

recruited minority candidates. Cf. LULAC at 861 (noting Republican

recruitment of minority judicial candidate). To the contrary, the

Republican Party nominated its first black Town Board candidate

only after this lawsuit was filed.

21

Moreover, unlike Baird, blacks do not enjoy a share of the

seats on the town board in proportion to their population in the

town and there is no evidence that black Republicans have been

elected to the Republican-dominated town board as readily as white

Republicans. Indeed, for 86 years, from 1907 until 1993, no black

person had ever been elected to serve on the Town Board. There was

only one election in which a black candidate was preferred by a

bare majority of white voters, and that was an election which the

district court properly discounted due to the special circumstances

surrounding it.10

Defendants-Appellants' statistical evidence regarding racially

polarized voting here actually confirmed the racial disparities in

elections that Plaintiffs-Appellees' expert found. Goosby, 956 F.

Supp. at 337 and 348. Thus, it is undisputed that African-American

and white voters in Hempstead have preferred different candidates

in Town Board elections, and that voting has been racially

polarized.

10The black candidate who won this election was initially

appointed to the position in 1993 and ran for re-election as an

incumbent. Incumbency has been recognized as a special

circumstance. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 57. In addition, this

appointment and subsequent election are suspect, as they occurred

after the lawsuit challenging the at-large system commenced.

Congress recognized that jurisdictions might seek to escape the

strictures of Section 2 by just such a manipulation of the

political process: " [T]he majority citizens might evade the

section e.g., by manipulating the election of a 'safe' minority

candidate." Senate Report at 29, n. 115, 1982 U.S.C.C.A.N. at 207.

Cf. N.A.A.C.P. v. City of Niagara Falls, 65 F. 3d 1002, 1005, 1018

n.18 (although first black council member was not elected until

after the lawsuit was filed, "[tjhere was no dispute that [he was

the] black voters' candidates of choice."). Gingles, 478 U.S. at

22

Under these circumstances, it is simply unrealistic to argue

that the consistent, deep disparities between black and white

voters in the support they give to black candidates -- disparities

that have persisted over time -- could somehow be unconnected to

race. In fact, the district court made numerous findings

concerning the impact of race upon political life in the Town of

Hempstead. For example, the Court found that Hempstead is

extremely segregated, and its black population is isolated. See id.

at 334 and 357. The tension from this racial separation has been

amplified over the past fifteen years by an influx of black

citizens from the Borough of Queens, which partially borders

Hempstead. The district court found that the in-migration of

black citizens from Queens has "result[ed] in some troubling

appeals to racism in campaign materials." Id. at 342. In

addition, evidence presented at trial showed that the Town Board

has not been responsive, and at times, has been blatantly

insensitive to the unique needs of the black community by, inter

alia, refusing to adopt an affirmative action policy, not

responding to charges of racial discrimination in Town hiring, and

failing to take action when it learned that a trophy bearing the

symbol of the Ku Klux Klan was on display in the fire department.

Id. at 344-345. These findings led the district court properly to

conclude that the use of the at-large election system actually

fostered, if not directly caused, this lack of responsiveness:

"At-large elections mean that no Town Council member is accountable

for neglecting the needs of their communities. No one has the

23

political incentive to breach the 'oneness' of the current Town

government." Id. at 352.11 Indeed, the district court found that

the facts suggested that "the black communities, on balance, have

been to a significant extent neglected by the Town government, and

the political processes by which that might be corrected are not

equally open to the participation of blacks in the Town -- even

black Republicans." Id. 352, 353.

In addition, the district court held that

[u]nder the functional view of the political

process mandated by Section 2, [one of] the

most important factors bearing on a [Section

2] challenge to a multimember system [is] the

extent to which minority group members have

been elected to public office in the

jurisdiction. . . . [T]he most critical fact

in this regard is that until the election of

Curtis Fisher in 1993, no African-American was

ever elected to the legislative body at issue

in this case.

Id. at 342-43. Thus, this case certainly does not present a

situation where the "persistent proportional representation" of the

plaintiffs' group defeats a finding of legally significant white

bloc voting under Gingles. 478 U.S. at 77.12 The lack of

proportionality is always relevant to the Section 2 inquiry: "[I]n

evaluating the Gingles preconditions and the totality of the

“ See also Butts v. City of New York, 779 F.2d 141, 148 (2nd

Cir. 1985) (recognizing that "the use of at-large elections instead

of single-member districts . . . may have the effect of denying

areas with large concentrations of minority voters the opportunity

to pool their strength and elect members of their class from such

areas").

“ Indeed, in Gingles, black candidates previously had been

elected to office in all of the legislative districts where a

Section 2 violation was found. 478 U.S. at 74 & nn. 35 & 36.

24

circumstances a court must always consider the relationship between

the number of majority-minority voting districts and the minority

group's share of the population." Johnson v. De Grandy, 512 U.S.

997, 1025 (1994) (O'Connor, J., concurring in the judgment)

(citation omitted). While not alone dispositive, a "[l]ack of

proportionality is probative evidence of vote dilution." Id. See

also, Gingles, 478 U.S. at 99 (O'Connor, J., concurring in the

judgment) ("the relative lack of minority electoral success under

a challenged plan, when compared with the success that would be

predicted under the measure of undiluted minority voting strength

the court is employing, can constitute powerful evidence of vote

dilution"). The district court's ultimate finding of vote dilution

is further supported by the evidence presented concerning the

success of minority candidates in the Town of Hempstead, and it

should be affirmed.

Defendants-appellants attempt to dismiss all of this proof by

assigning partisan labels to the disparate white and black voting

blocs in the Town of Hempstead, and completely attributing patterns

of legally significant racially polarized voting to "non-racialM

partisan politics. As their evidence that partisanship rather than

race accounts for the persistent defeat of black preferred

candidates, appellants only offer a basic racial breakdown of the

two predominant political parties. Reciting the percentages of the

white and black electorate which are Democrats and Republicans,

they simply note that the majority of whites are Republicans and

the majority of blacks are Democrats, and conclude that blacks lose

25

because they occupy a small percentage of an already politically

small, predominantly white Democratic voting bloc.13 However,

Defendants-Appellants' contention that the black voters are unable

to effectively express their political preference because they are

a smaller portion of a weak political party is unavailing.

Defendants-Appellants' expert conceded that "there was a pattern of

racial polarization," but he also contended that "there was a

stronger pattern of political partisanship, which had the secondary

effect of racial polarization, because blacks preferred Democratic

candidates and whites preferred Republican candidates." Id.

This conclusion, rather than disproving the existence of

racially polarized voting, simply begs the question. There is no

dispute here concerning the racial differences in candidate choices

in Hempstead elections: experts for both sides agree that black

and white voters in Hempstead prefer different candidates. In

election after election, black and white voters have supported

different candidates, and under the challenged at-large scheme, the

candidates preferred by Hempstead's African-American voters have

“Actually, rather than undercutting appellees' case, the small

number of registered black voters may assist in establishing the

degree of vote dilution in this case. As Gingles recognizes, the

level of white bloc voting necessary to defeat minority-preferred

candidates will 'vary from district to district according to a

number of factors,' including the percentage of minority registered

voters. 478 U.S. at 55-57. In this case, because there are so few

registered black Democratic voters, there are fewer black voters in

Hempstead to offset the impact of the white bloc vote, thus,

amplifying the dilutive effect of the white bloc voting. See

Rangel v. Morales, 8 F.3d 242, 245 (5th Cir. 1993) ("if the

minority group constitutes only a small fraction of the total

number of registered voters, it may be, relatively speaking, easier

for the members of that group to establish their effective

submergence in a white majority.").

26

been consistently defeated. As discussed above, it is irrelevant

to the analysis of the third Gingles factor, to explain why an

otherwise cohesive black electorate votes for particular candidates

and why a white electorate votes as a bloc against the black

preferred candidate. In any event, the Defendants-Appellants'

labored discussion presents no objectively verifiable support for

their theory that partisan affiliations are wholly responsible for

election outcomes in Hempstead, nor have Defendants-Appellants

persuasively eliminated racial considerations as an explanation for

the proven racially polarized voting in Hempstead. The district

court's finding of legally significant racially polarized voting

(i.e., that Hempstead's white electorate votes consistently as a

bloc to defeat the candidates of choice of a politically cohesive

black electorate) should therefore be affirmed.

Despite the strength of the Section 2 case presented by the

Plaintiffs-Appellees below, Defendants-Appellants contend that

"[t]he failure of minority-preferred candidates in the Town has

nothing to do with race and everything to do with the small

percentage of the population that is black and blacks' alignment

with the unsuccessful political party." Defendants-Appellants'

Brief at 43-44. Following this logic, the clear inability of

Hempstead's black voters to elect candidates of choice in contested

elections under the at-large system -- a phenomenon which

Defendants-Appellants concede is present in Hempstead -- can never

be remedied, or alternatively, could only be ameliorated if black

voters would ignore their true preferences and cast their ballots

27

for the white Republican candidates who regularly prevail under

this at-large system.

However, as numerous Courts have held, the requirements of the

Voting Rights Act are not met if "'[c]andidates favored by blacks

can win, but only if the candidates are white.'" Jenkins v. Red

Clay Consol. Sch. Dist. Bd. of Ed., 4 F.3d 1103, 1128 n. 22 (3rd

Cir. 1993), cert, denied, 114 S. Ct. 2779 (1994), quoting Smith v.

Clinton, 687 F. Supp. 1310, 1318 (E.D. Ark.) (three-judge court),

aff d mem., 488 U.S. 988 (1988). See also Westwego Citizens for

Better Government v. City of Westwego, 946 F. 2d 1109, 1119 n.15

(5th Cir. 1991); cf. City of Niagara Falls, 65 F.3d at 1015-1016

(acknowledging that minority-preferred candidates often will be

members of the minority group, but declining to ignore elections in

which no black candidates ran, and concluding that white candidates

are sometimes the choice of minority voters). By amending Section

2 for the specific purpose of addressing minority vote dilution,

Congress deliberately expanded the relevant political universe by

treating as legitimate and worthy of equal recognition the

political choices of black voters. See S. Rep. No. 97-417 at 28-29

(recognizing that "members of the minority group" may have

"particularized needs" which could be neglected by officials who

are elected exclusively or overwhelmingly by members of the

majority group); cf. Goosby, 956 F. Supp. at 344-45 (finding that

Plaintiffs-Appellees "established a significant lack of

responsiveness to the particularized needs of blacks in the Town

[of Hempstead]"). These principles are not nullified simply because

28

African-American and white voters in Hempstead are largely

adherents of different political parties.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth herein, the NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc., respectfully prays that this Court will

affirm the decision of the district court.

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE R. JONES

Director-Counsel

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

JACQUELINE A. BERRIEN

VICTOR A. BOLDEN

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

TODD A . COX

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

29

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the foregoing Brief of Amicus

Curiae in support of Plaintiffs-Appellees have been served by first

class United States mail, postage paid, addressed to the following:

Evan H. Kriniek., Esq. Katharine I. Butler, Esq.

Rivkin, Radler & Kremer University of South

EAB Plaza Carolina Law School

Uniondale, NY 11556-0111 Columbia, SC 29208

This 26th day of January, 1998.