Missouri v. Jenkins Brief of Respondents Kalima Jenkins in Opposition to the Petition

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Missouri v. Jenkins Brief of Respondents Kalima Jenkins in Opposition to the Petition, 1988. 77ffddf3-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9e037016-c0b3-4acf-ab2c-5f404882f189/missouri-v-jenkins-brief-of-respondents-kalima-jenkins-in-opposition-to-the-petition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

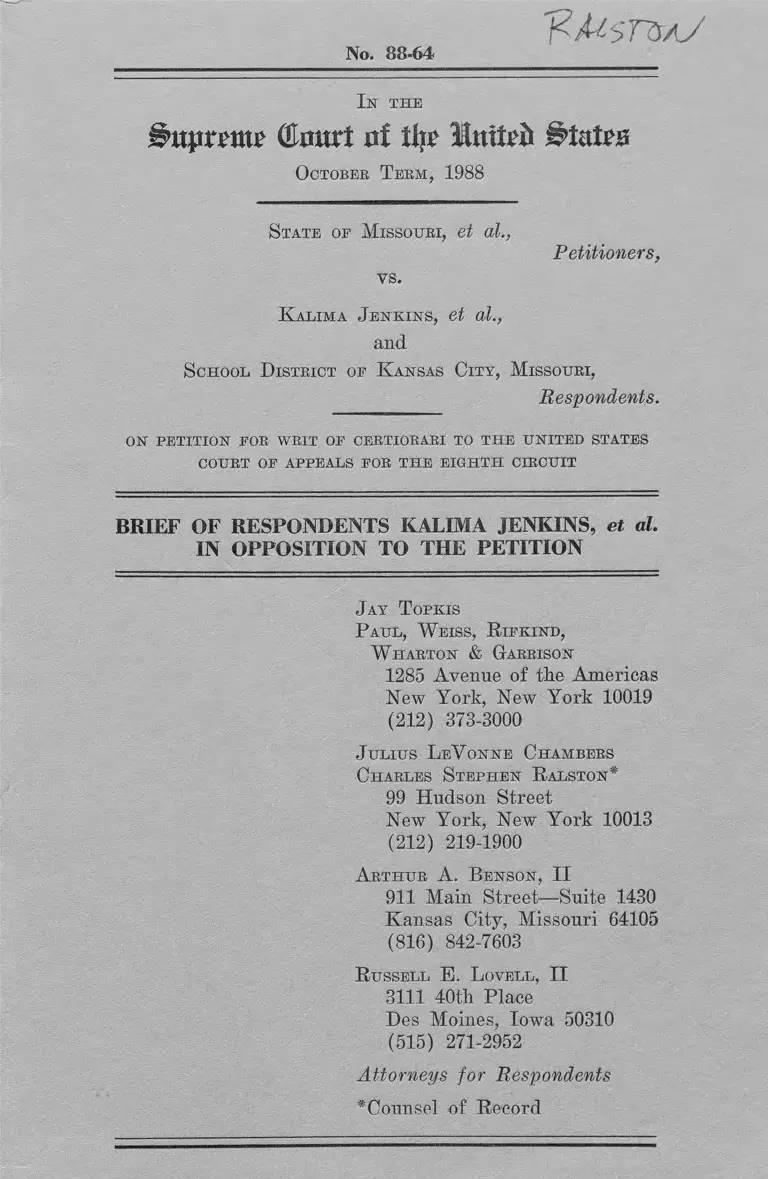

No. 88-64

I n th e

&Kpvm? ©mart of % Initpft £>tate

October T erm, 1988

State of Missouri, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

K alima J enkins, et al.,

and

School, D istrict of K ansas City, Missouri,

Respondents.

on petition for w rit of certiorari to t h e u n ited states

court of appeals for t h e eig h th circuit

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS KALIMA JENKINS, et al.

IN OPPOSITION TO THE PETITION

Jay T opkis

P aul, W eiss, R ifkind,

W harton & Garrison

1285 Avenue o f the Americas

New York, New York 10019

(212) 373-3000

J ulius L eV onne Chambers

Charles Stephen R alston*

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

A rthur A. Benson, II

911 Main Street— Suite 1430

Kansas City, Missouri 64105

(816) 842-7603

R ussell E. L ovell, II

3111 40th Place

Des Moines, Iowa 50310

(515) 271-2952

Attorneys for Respondents

^Counsel o f Record

i

QUESTION PRESENTED

Does the Eleventh Amendment bar the

adjustment of an award of attorneys' fees

against a state under 42 U.S.C. § 1988 to

compensate for delay in payment, when it

is reversible error under state law for a

trial court not to include an award of

prejudgment interest against state

agencies when fees are awarded?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

11

Page

Question Presented ................ i

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.............. 3

1. Litigation on the Merits. . 3

2. The Fee Applications. . . . 6

3. The District Court'sDecision. ................ 9

4. The Decision of the

Court of Appeals....... 10

ARGUMENT

I. NO ELEVENTH AMENDMENT

ISSUE IS RAISED SINCE

MISSOURI LAW MANDATES

THE AWARD OF PREJUDGMENT

INTEREST AGAINST A STATE AGENCY..................11

II. THE DECISION BELOW IS

CLEARLY CORRECT ......... 17

III. THE AMOUNT OF FEESAPPROPRIATE IN THIS CASE WAS A MATTER WITHIN THE SOUND DISCRETION OF THE

DISTRICT COURT . . . . 23

CONCLUSION 29

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases:

Bernard McMenamy Contractors, Inc.

v. Missouri State Highway

Commission, 582 S.W.2d 305

(Mo. App. 1979) . 15

Blanchard v. Bergeron, 831 F.2d 563(5th Cir. 1987).............. 28

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.483 (1954).................. 3

Cranford Co. v. City of New York,38 F.2d 52 (2d Cir. 1930) . . . 12

Denton Construction Co. v. Missouri

State Highway Commission, 454

S.W.2d 44, 60 (Mo. 1970) 13, 15, 16

Garrett v. Citizens Saving Ass'n,

636 S.W. 2d 104 (Mo. App.

1982)..................... 13, 14

Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde Air Products Co., 336 U.S. 271

(1949)....................... 26

Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424(1983) 7, 9, 10, 20, 23, 24, 26, 27

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678 (1978) 20

Jenkins v. Missouri, 807 F.2d 657 (8th

Cir. 1986)fen banc), cert, denied.484 U.S. __ , 98 L.Ed.2d

34 (1987) 6,11

iv

Jenkins v. Missouri, ___ F.2d ____(8th Cir. Nos. 86-1934; 86-2537 87-1749; 87-2299; 87-2300; 87

August 19, 1988) ............

Knight v. DeMarea, 670 S.W.2d 59

(Mo. App. 1984) ..............

Laughlin v. Boatmen's National

Bank of St. Louis, 189 S.W.2d 974 (Mo. 1945) ...............

Library of Congress v. Shaw, 478 U.S

310 (1986) ..................

Loeffler v. Frank, 486 U.S.__,

100 L.Ed.2d 549 (1988) . . . .

Moore v. City of Des Moines, 766

F.2d 343 (8th Cir. 1985), cert, denied. 474 U.S.

1060 (1986) ..................

Pennsylvania v. Delaware Valley

Citizens Council, 483 U.S. ___,

97 L.Ed.2d 585 (1987) . . . 14

Rogers v. Okin, 821 F.2d 22 (1stCir. 1987) ..................

St. Joseph Light & Power Co. v.

Zurich Ins. Co., 698 F.2d 1351 (8th Cir. 1983) .............

Slay Warehouse Co., Inc. v. Re:

Insurance Co., 480 F.2d 214 (8th Cir. 1974) ..............

Steppelman v. State Highway Comm Missouri, 650 S.W.2d 343 (Mo. App. 1983) .............

2588 ,

6

15

14

18

28

20

17

13

iance

13

n of

16

V

United States v. Johnson, 268 U.S.

220 (1925)................... 26

United States v. North Carolina,

136 U.S. 211 (1890).......... 12

Vaughns v. Board of Education ofPrince Georges County, 598 F.

Supp. 1262 (D. Md. 1984), aff'd. 770 F.2d 1244 (4th

Cir. 1985).................. 25

Virginia v. West Virginia, 238 U.S.

202 (1915) 12

Whalen, Murphy, Reid v. Estate of Roberts, 711 S.W.2d 587

(Mo. App. 1983).............. 14

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 2516..................19

42 U.S.C. § 1988 .......... 14, 17, 20

Missouri Statutes: § 408.020.................. 12, 14, 15, 16

Missouri Statutes: § 408.040 . . . 16

Other Authorities:

Stern, Gressman & Shapiro, Supreme Court Practice, 198 (6th Ed.) . . . . 22

No. 88-64

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1988

STATE OF MISSOURI, et al.,

Petitioners.

vs.

KALIMA JENKINS, et al.,

and

SCHOOL DISTRICT OF KANSAS CITY,

MISSOURI,

Respondents.

On Petition For Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals

For The Eighth Circuit

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS KALIMA JENKINS, ET AL.

IN OPPOSITION TO THE PETITION

Respondents Kalima Jenkins, et al.,

urge that the petition for a writ of

certiorari be denied on a number of

grounds: (1) the issue of whether the

Eleventh Amendment bars compensation for

2

delay in payment in calculating an

attorneys' fee against a state is not

raised by the present case since Missouri,

by statute, mandates the award of

prejudgment interest on attorneys' fees

awards against state governmental

agencies; (2) the issue is not an

important one, since it is clear that

there is no bar under the Eleventh

Amendment to the award of fully

compensatory attorneys' fees by a federal

court against a state agency; (3) the

other issues relating to the amount of

fees awarded by the district court and

upheld by the court of appeals are not of

importance, involve findings of fact that

are not clearly erroneous but are fully

supported by the record, and involve the

application of established law to matters

within the sound discretion of the

district court.

3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The statement of the case in the

petition does not adequately describe the

outcome of the litigation on the merits

nor the lengthy and thorough litigation of

the fees application in the district

court.

ii__The Litigation on the Merits.

This case began as a challenge by the

Kansas City, Missouri School District

(KCMSD) against the State of Missouri for

the defendant's failure to correct the

severe problems of segregation and racial

discrimination that had their origins in

the statewide de jure school segregation

that existed prior to this Court's

decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

347 U.S. 483 (1954). Through a succession

of orders of the district court,

plaintiffs representing black school

4

children in the KCMSD were intervened, the

KCMSD was realigned as a party defendant,

and a series of suburban school districts

were joined as parties defendant since the

relief sought included, inter alia,

interdistrict integration of school

facilities.

Throughout the course of the

litigation, the KCMSD admitted its

historic responsibility for some of the

remaining segregation in the system and,

while nominally a defendant, in fact

supported the plaintiffs during the

litigation. The state, on the other hand,

battled to the bitter end against any

finding of liability and responsibility

for providing any relief. After a lengthy

trial of plaintiffs' case, the district

court first found in favor of the suburban

schoo l districts as to their

responsibility for the segregation of

5

KCMSD and therefore dismissed them from

the case. The state persisted in its

defense necessitating further proceedings

on the merits as well as on relief.

Subsequently, the district court

issued its decision holding the state

liable for creating and maintaining,

through its failure to carry out its duty

to disestablish, the segregation and

racial isolation of the KCMSD. The court

found that state policies with regard to

segregated schools within districts, the

exclusion of black schools from suburban

districts and their isolation in Kansas

City, underfunding of black schools,

discrimination in housing, and other

matters, all were directly responsible for

the creation of KCMSD as a black school

district. It ordered further proceedings

to determine appropriate relief and

subsequently entered a series of remedial

6

orders that require the state and the

KCMSD to spend a total to date of more

than $400,000,000 in capital improvements,

remedial programs, magnet schools, etc.^

2. The Fee Applications.

Following the decision finding

liability on the part of the state,

plaintiffs filed lengthy fee applications

on behalf of private local counsel, Arthur

Benson, as well as counsel provided by the

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. The applications meticulously

detailed all of the time spent by

attorneys, paralegals, and law clerks, as

well as all expenditures. The

applications then excluded time that was

allocable to the claims relating to the

-̂The Eight Circuit has affirmed the

district court's remedial orders in nearly

all respects. Jenkins v. Missouri, ___F.2d ___ (8th Cir. Nos. 86-1934; 86-2537;

87-1749; 87-2299; 87-2300; 87-2588, August

19, 1988).

7

issues and defendants concerning which

plaintiffs had not prevailed, pursuant to

this Court's decision in Hensley v.

Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 (1983).2 All

other time, it was urged, was either

clearly allocable to claims upon which

plaintiffs had prevailed or was spent on

tasks regarding which prevailing and non

prevailing claims were interwoven and

interrelated. The state filed lengthy

objections and took the position that not

only should clearly allocable time be

excluded, but that then an arbitrary fifty

percent of all remaining time be excluded

on the assumption that that amount of time

was probably spent on non-prevailing

2Benson cut 2017 attorney hours and 2521 paralegal hours from his claim. The

total Benson reduction was approximately 21% of Benson's requested lodestar. The

LDF attorneys eliminated 1611 attorney

hours, 319 recent law graduate hours, 920

paralegal hours, and 3286 law clerk hours.

The total LDF reduction was approximately 16% of LDF's lodestar request.

8

issues. Although the state made some

generalized objections to specific entries

and to the requested hourly rates, it

conducted no discovery.

The district court held a one-day

hearing on the fee applications. At the

hearing, the plaintiffs put on two expert

witnesses, William Taylor, Esq., an

expert in the area of school

desegregation litigation, and Mr. Robert

Weil, an expert in the area of the

economics of legal practice. Mr. Taylor

testified concerning the interrelatedness

of the issues litigated in the case and

the excellent results obtained. Mr. Weil

testified concerning appropriate hourly

rates for the lawyers, paralegals, and law

clerks, and concerning the absolute

necessity for compensating for delay in

payment in order to be able to attract

attorneys to take on this type of case.

9

Further testimony was given by a

prominent local Kansas City attorney

concerning hourly rates and the

undesirability of a civil rights case of

the magnitude of the present one.

The state put on no testimony of its

own, except to call Mr. Arthur Benson,

plaintiffs' local counsel, to the stand to

ask a few questions about his application.

3. The District Court's Decision.

Following the hearing, both sides

submitted proposed findings of fact and

were give an opportunity to supplement the

record. The district court entered its

order accompanied with detailed findings

of fact regarding the reasonableness of

the hours requested and the hourly rates.

With regard to Hensley reductions, the

court found that the specific allocations

made by plaintiffs were accurate and the

other work was so interrelated between

10

further reductions were not appropriate.

The court made similar findings with

regard to expenses as well as specific

findings regarding hourly rates of

attorneys, paralegals, and law clerks.

4. The Decision of the Court of Appeals.

On appeal, the state pursued its

various arguments relating to proper

Hensley reductions in view of the

decisions of the district court and the

court of appeals on the merits of the

case. The court of appeals upheld the

district court in all respects, holding

that its findings were fully supported by

the record. The full court declined to

hear the case en banc, thereby implicitly

rejecting the state's argument that the

panel decision on attorneys' fees was in

any way inconsistent with the en banc

decision on the merits rendered just one

year before. Jenkins v. Missouri. 807

11

year before. Jenkins v. Missouri. 807

F.2d 657 (8th Cir. 1986) fen banc) . cert.

denied. 484 U.S. ____ , 98 L.Ed.2d 34

(1987), Appendix, p. A50. Judge John

Gibson, the author of the en banc decision

on the merits was also the author of the

panel decision on attorneys' fees.

ARGUMENT

I.

NO ELEVENTH AMENDMENT ISSUE IS RAISED

SINCE MISSOURI LAW MANDATES THE AWARD OF

PREJUDGMENT INTEREST AGAINST A STATE AGENCY

As we demonstrate in Part II, infra,

the Eleventh Amendment does not bar a

f e d e r a l court from including

compensation for delay in payment when it

awards attorneys' fees against a state.

However, this issue would never be reached

in this case because of the well

established rule that even in

circumstances where there is a general

12

prohibition against the award of interest

against a state, that prohibition

disappears if state law itself permits

such an award. See United States v.

North Carolina, 136 U.S. 211 (1890);

Virginia v. West Virginia. 238 U.S. 202

(1915) ; Cranford Co. v. City of New York.

38 F.2d 52 (2d Cir. 1930). Since Missouri

law not only allows but mandates awards of

interest against state governmental

agencies, including prejudgment interest

on fees claims, the inclusion of interest

in the fees awarded by the federal court

was consistent with Missouri law; as a

result, the Eleventh Amendment issue

sought to be presented here simply does

not arise.

Section 408.020 of the Missouri

Statutes3 has been construed by the

3Section 408.020 provides:Creditors shall be allowed to receive interest at the rate of nine

13

Missouri Supreme Court to require trial

courts to award prejudgment interest

whenever the amount due is liquidated, or,

although not strictly liquidated, is

readily ascertainable by reference to

recognized standards. Denton Construction

Co. v. Missouri State Highway Commission.

454 S. W. 2d 44, 60 (Mo. 1970); St. Joseph

Light & Power Co. v. Zurich Ins. Co.. 698

F.2d 1351, 1355 (8th Cir. 1983); see

also, Slay Warehouse Co., Inc, v. Reliance

Insurance Co.. 480 F.2d 214, 215 (8th Cir.

1974)("[T]he award of prejudgment interest

in a case in which Section 408.020 is

percent per annum, when no other rate is

agreed upon, for all moneys after they

become due and payable, on written contracts, and on accounts after they become due and demand of payment is made;

for money recovered for the use of another, and retained without the owner's knowledge of the receipt, and for all other money due or to become due for the

forbearance of payment whereof an express

promise to pay interest has been made.

14

applicable is not a matter of court

discretion; it is compelled.") It is

readily evident from a substantial body of

Missouri case law that attorneys' fees

awards pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1988, based

as they are on the lodestar method of

calculation, are readily ascertainable

within the meaning of § 408.020 and

therefore must include an award of

prejudgment interest.

Prejudgment interest under § 408.020

has been awarded in quantum meruit actions

on unliquidated claims for legal services

that were measured and determined by the

standard of reasonable value of services

rendered. Laughlin v. Boatmen's National

Bank of St. Louis. 189 S.W.2d 974 (Mo.

1945) ; Garrett v. Citizens Saving Ass'n.

636 S.W. 2d 104, 112 (Mo. App. 1982).

See also, Whalen. Murphy, Reid v. Estate

of Roberts. 711 S.W.2d 587, 590 (Mo. App.

15

1983), holding that the trial court erred

in not awarding prejudgment interest on an

attorney's fees claim and that plaintiff's

failure to "receive an award for the full

amount of the claim does not bar the right

to receive pre-judgment interest on the

amount the trial court actually awarded."

Thus, the fact that the defendant denies

liability or challenges the amount claimed

will not relieve the defendant of his duty

to pay the pre judgment interest of the

award found to be due. Knight v. DeMarea.

670 S.W.2d 59 (Mo. App. 1984); St. Joseph

Light & Power Co. v. Zurich Ins. Co. .

supra.

Finally, the Missouri courts have

also made clear that § 408.020 is fully

applicable in litigation involving the

State of Missouri as a defendant. Denton

Construction, supra. Bernard McMenamy

Contractors, Inc., v. Missouri State

16

Highway Commission, 582 S.W.2d 305 (Mo.

App. 1979). Indeed, the state defendants'

argument that the prejudgment interest

provision of § 408.020 did not authorize

awards against the state was expressly-

rejected in Steppelman v. State Highway

Comm'n of Missouri. 650 S.W.2d 343, 345

(Mo. App. 1983), citing Denton

Construction and McMenamv Contractors.4

Since under Missouri law the award of

prejudgment interest is permissible

against the state or one of its agencies,

and would be mandated by Missouri Statute

§ 408.020 with regard to plaintiffs'

attorneys' fees claim in the instant case,

there can be no bar under the Eleventh

Amendment or otherwise to such an award by

4Section 408.040 of the Missouri Statutes, which provides for interest on judgments or orders of any Court, has also

been interpreted to permit the award of

post-judgment interest against the state

of Missouri. Steppelman. supra at 345.

17

a federal court. Thus, whatever may be

the resolution of the issue posed by

Rogers v. Okin. 821 F.2d 22 (1st Cir.

1987) , it simply does not arise in the

present case and should not be addressed

herein by the Court.

II.

THE DECISION BELOW IS CLEARLY CORRECT

The Eighth Circuit correctly rejected

the view of the First Circuit in Rogers v.

Okin, supra, that this Court's decision in

Library of Congress v. Shaw. 478 U.S. 310

(1986) somehow barred the use of current

rates to compensate attorneys under 42

U.S.C. § 1988 when fees are awarded

against a state agency. As we will

explain below, the First Circuit's

decision is based on a fundamental

misreading of Shaw and the Eleventh

Amendment and is not likely to be

followed by any other court. Moreover,

18

the limited nature of the Shaw rule, as

explicated by this Court in the recent

decision of Loeffler v. Frank, 486 U.S.

100 L.Ed.2d 549 ( 1988 ) , and the

unlikelihood that the issue will arise in

other cases, make the issue presented

unimportant. Respondents therefore urge

that the Court should deny certiorari and

decline to review the issue unless and

until a widespread conflict among the

courts of appeals becomes evident.

As explained in Lpeffler, the Shaw

rule derives from an ancient doctrine

applicable only to federal agencies; that

is, the federal government's sovereign

immunity prohibits an award of interest

against it unless Congress so provides

either by a specific statute dealing with

interest or by a general waiver of

sovereign immunity with regard to a

particular agency of the government. This

19

doctrine has been codified in 28 U.S.C. §

2516 and, therefore, is binding on the

courts.

The Eleventh Amendment, the basis of

the First Circuit's decision in Rogers. on

the other hand, is not a general statement

of sovereign immunity. Rather, as the

Eighth Circuit correctly held in the

present case, it is a limitation on the

power of the federal courts to hear

certain types of actions against states

unless Congress provides otherwise or the

state itself acquiesces in the

jurisdiction of the federal courts

expressly or by implication. Once,

however, relief is properly awardable

against a state, there are no general

limitations on such relief that stem from

any residual sovereign immunity that the

state may claim.

Thus, as again the Eighth Circuit

20

properly held, the governing decision here

is Hutto v. Finnev. 437 U.S. 678 (1978),

which held that fees could be awarded

against a state pursuant to § 1988 despite

the Eleventh Amendment. Hutto held that

§ 1988 was enacted pursuant to Congress'

power to enact legislation to enforce the

Fourteenth Amendment; therefore, that

power overrode the Eleventh Amendment's

limitation on the power of the federal

courts.

Hutto held, in the alternative, that

a reasonable attorney's fee in a suit

against the state for prospective relief

was itself prospective relief not barred

by the Eleventh Amendment. Id. at 695.

This latter ground was completely

overlooked by the First Circuit in Rogers.

Once the court below had the power to

assess fees against the defendant state at

all, it had power to assess a fee that was

21

fully compensatory. As Loeffler makes

clear,5 an adjustment for delay in payment

is part of a fully compensatory fee, but

was not awardable against a federal

government agency solely because of the

sovereign immunity of the federal

government itself.

Reading Rogers one is left with the

firm impression that the parties viewed

the Eleventh Amendment issue as an

afterthought in an appellate battle that

concentrated on issues raised by Henslev

v. Eckerhart. 461 U.S. 424 (1983).

Respondents submit there is reason to

doubt whether the First Circuit's

consideration of the Eleventh Amendment

issue in Rogers was guided by the

thorough briefing warranted by its

5See 100 L.Ed. 2d at 558, n. 5. See

also, Pennsylvania v. Delaware Valley Citizens Council. 483 U.S. , 97 l .Ed 2d 585, 592, 604-05 (1987).

22

complexity. First, the issue was neither

raised in nor considered by the district

court, since this Court's decision in Shaw

was issued after the district court's fee

award. 821 F.2d at 28. Second, the First

Circuit itself expressly noted that the

Eleventh Amendment issue "was allowed only

five pages in [the Commonwealth's] 98-page

main brief." 821 F.2d at 28. Respondents

submit that the issue raised by

petitioners was correctly resolved by the

Eighth Circuit in the instant case by

routine application of Eleventh Amendment

case law, and that therefore certiorari

should be denied until more than two

courts of appeal have considered the

guestion, since it is likely the seeming

conflict may be resolved as a result of

future cases in the courts of appeals.

See Stern, Gressman & Shapiro, Supreme

Court Practice 198, 200 (6th Ed.).

23

THE AMOUNT OF FEES APPROPRIATE IN THIS CASE

WAS A MATTER WITHIN THE SOUND DISCRETION

OF THE DISTRICT COURT.

Despite the efforts of the

petitioners, the remaining issues

presented by the petition for a writ of

certiorari are simply not appropriate for

review by this Court. As demonstrated by

the decisions below and by the Statement

of the Case above, there were no novel

issues of law presented by the fee

applications here. The problem faced by

the district court was the correct

application of the law as established by

this Court in Hensley v. Eckerhart. 461

U.S. 424 (1983) to a particular set of

facts unique to this case. Indeed, the

fees hearing was postponed until the

Eighth Circuit's en banc decision on the

merits had been reached, in order that the

district court's Hensley determinations

would be guided by the appeals court's

24

would be guided by the appeals court's

decision. The parties^ere able to make

as complete a factual record as they

desired, argued their positions as to the

proper application of Hensley. were

provided a hearing by the district court,

and submitted detailed proposed findings.

The district court, after these exhaustive

submissions, reviewed the record and made

its findings of fact based not only on the

fee applications and the evidence adduced

in relation thereto, but on its own

intimate knowledge of the litigation as a

whole. Its resolutions of the myriad

factual questions thus presented, which

were upheld in their entirety by the court

of appeals, simply do not merit the

exercise of this Court's discretionary

review.

In affirming the district court's

application of Hensley, a resolution that

25

adopted the 15 to 20 percent lodestar

reduction proposed by plaintiffs, the

Eighth Circuit was cognizant that it was

this same district court that had ruled

against plaintiffs on their inter-district

claims against the suburban districts and

the federal defendants and thereby

necessitated the application of Hensley in

the first place. Without question, the

district court had intimate familiarity

with the plaintiffs' successful and

unsuccessful claims, the interrelatedness

of the claims, and the results obtained.6

Petitioners also cite Vaughns v.

Board of Education of Prince Georges

County. 598 F.Supp. 1262 (D. Md. 1984),

aff'd. 770 F.2d 1244 (4th Cir. 1985), for

the proposition that expenses incurred on

unsuccessful claims must be excluded per

Hensley. Petitioners, however, do not

claim that Vaughns represents a conflict among the circuits, as they indeed cannot,

for the question of a percentage reduction of plaintiffs' expenses based on Hensley was not appealed to the Fourth Circuit.

Furthermore, although the district court in Vaughns did apply the percentage

reduction used on the fees claim to

26

Of course, this Court does not grant

certiorari to review evidence and discuss

specific facts. United States v. Johnson,

268 U.S. 220, 227 (1925). Although, as

petitioner notes, the Eighth Circuit did

comment that it "might not have arrived at

the same result as the district court" had

it fixed the initial percentage reduction,

838 F.2d at 264, it concluded the district

court's Hensley findings were not clearly

erroneous. Findings of fact made by the

district court and concurred in by the

court of appeals are subject to the "two

court" rule, Graver Tank & Mfcr. Co. v.

Linde Air Products Co.. 336 U.S. 271, 275

(1949),* 7 the application of which is made

plaintiffs' expenses claim, the district

court implied it retained discretion to

conclude otherwise, stating only that "on

a rough justice basis" the same percentage "is appropriate." Id. at 1290.

7"A court of law, such as this Court

is, rather than a court for correction of errors in fact finding, cannot undertake

27

all the more compelling in the instant

case because each, of ^he judges on the

panel that decided the fees appeal

participated in the en banc decision on

the merits and, most importantly, the

judge who wrote the en banc decision also

wrote the panel decision on fees.

In Hensley this Court expressed the

strong view that fee applications should

not give rise to extended independent

litigation (461 U.S. at 437); a number of

courts of appeals, including the Eighth

Circuit, have repeatedly admonished that

parties should not routinely seek review

of the manner in which a district court

has exercised its sound discretion in

awarding fees, in the absence of

compelling indications that that

to review concurrent findings of fact by two courts below in the absence of a very

obvious and exceptional showing of error." 336 U.S. at 275.

28

discretion has been abused. E.g.. Moore

v. City of Des Moines. #766 F.2d 343, 345-

46 (8th Cir. 1985), cert, denied. 474 U.S.

1060 (1986). Nevertheless, petitioner has

continued to pursue just such an appeal;

to grant certiorari on the issues thus

presented, would encourage other

litigants, plaintiffs and defendants

alike, to appeal fee decisions they are

dissatisfied with and discourage the

prompt compromise and reasonable

resolution of fee claims.8

Petitioners noted that this Court has granted review in Blanchard v. Bergeron. 831 F.2d 563 (5th Cir. 1987),

review granted, No. 87-1485, 56 U.S.L.W.

3873 (June 28, 1988), . and assert that

Blanchard raises a "similar issue" to

petitioners' contention that § 1988 does

not permit the award of fees for

paralegals and law clerks at market rates.

Respondents would observe that the

question of paralegal hourly rates,

although raised, was not addressed by the

Fifth Circuit in Blanchard. That court

only held that a contingency fee agreement

between plaintiff and his counsel would

operate as a cap on the fee which could be

recovered from the defendant. Because the

29

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the

petition for a writ of certiorari should

be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

JAY TOPKIS

PAUL, WEISS, RIFKIND, WHARTON & GARRISON

1285 Ave. of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10019 (212) 373-3000

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON* 99 Hudson Street

New York, N.Y. 10013 (212) 219-1900

fee cap imposed by the contingency

agreement was apparently substantially below the lodestar, the Fifth Circuit

declined any discussion of paralegal and law clerk hourly rates, stating only that

such hours "would also naturally be included within the contingency fee." id.

at 564. Even if this Court reverses the

Fifth Circuit's holding on the fee cap issue, it would seem unlikely that it

would decide the paralegal rates issue.

30

ARTHUR A. BENSON, II

911 Main Street

Suite 1430

Kansas City, Mo. 64105 (816) 842-7603

RUSSELL E. LOVELL, II

3111 40th Place Des Moines, Iowa 50310

(515) 271-2952

Attorneys for Respondents

*Counsel of Record

Hamilton Graphics, Inc.— 200 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y.— (212) 966-4177