Saunders v Claytor Brief for the Appellee

Public Court Documents

October 17, 1979

26 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Saunders v Claytor Brief for the Appellee, 1979. 28cb71b0-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9e105ab2-7405-4291-b444-66e366e277ef/saunders-v-claytor-brief-for-the-appellee. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

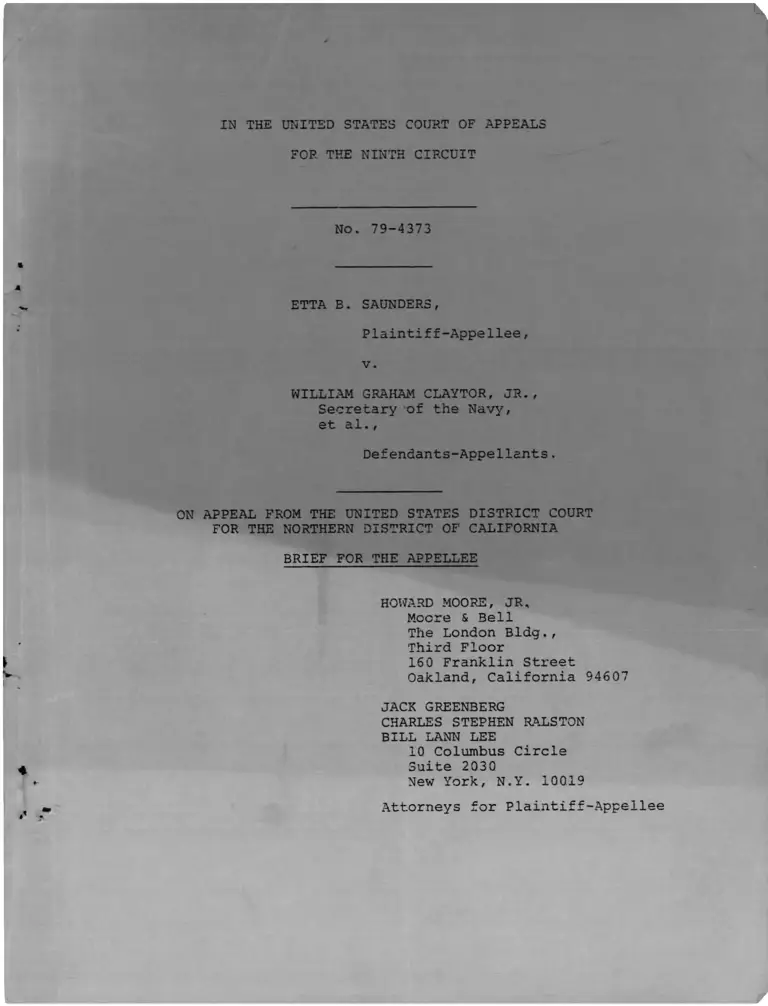

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

No. 79-4373

ETTA B. SAUNDERS,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

WILLIAM GRAHAM CLAYTOR, JR.,

Secretary of the Navy,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF FOR THE APPELLEE

HOWARD MOORE, JR,

Moore & Bell

The London Bldg.,

Third Floor

160 Franklin Street

Oakland, California 94607

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

BILL LANN LEE

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, N.Y. 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellee

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

No. 79-4373

ETTA B. SAUNDERS,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

WILLIAM GRAHAM CLAYTOR, JR.,

Secretary -of the Navy,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF FOR THE APPELLEE

HOWARD MOORE, JR,

Moore & Bell

The London Bldg.,

Third Floor

160 Franklin Street

Oakland, California 94607

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

BILL LANN LEE

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, N.Y. 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellee

I N D E X

Questions Presented .................................... 1

Statement of The Case ............... 2

Summary of A r g u m e n t ................... 4

Argument

I. The Inclusion of A Cost of Living Factor

in Calculating Back Pay Is A Necessary

Part of Fashioning Relief That Will Make

A Victim of Discrimination Whole .......... 4a

II. As The Prevailing Party, Plaintiff Was

Entitled to An Award of Counsel Fees for

All Work Reasonably Done in The

Litigation of The C a s e ........................11

Conclusion........................... 17

Certificate of Service ................................ 17

Appendix................................................. la

Page

TABLE OF CASES

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) . . . . 4,5

Brown v. Bathke, 588 F.2d 634 (8th Cir. 1978)........... 16

Brown v. General Services Administration, 425 U.S. 820

(1976)................................................... 10

Cannon v. University of Chicago, U.S. , 60 L.Ed.

2d 560 (1979).......................................... 13

Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840 (1976)............... 6,10

Cooper v. Curtis, 16 EPD 1(8099 (D.D.C. 1978). . . . . . . 16

Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 8 E.P.D. 1(9444

(D.C. Calif. 1974) 13,14,15

Day v. Mathews, 530 F.2d 1083 (D.C. Cir. 1976)............ 6,7

Dawson v. Pastrick, F.2d , 19 E.P.D. 1(9270

(7th Cir. 1979)........................................ 16

Donaldson v. O'Connor, 454 F. Supp. 311 (N.D. Fla. 1978). 16

Eastland v. T.V.A., 553 F.2d 364 (5th Cir. 1977) . . . . 6

Foster v. Boorstin, 561 F.2d 340 (D.C. Cir. 1977) . . . . 6

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976). 5

Grubbs v. Butz, 514 F.2d 1323 (D.C. Cir. 1975)...... 7

Howard v. Phelps, 443 F. Supp. 374 (E.D. La. 1978) . . . 16

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d 714 (5th

Cir. 1974)............................................. 13

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974)........... 6,10

Palmer v. Rogers, 10 EPD 1(10,499 (D.D.C. 1 9 7 5 ).... 16

Parker v. Califano, 561 F.2d 320 (D.C. Cir. 1977) . . . . 13

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co,, 494 F.2d 211

(5th Cir. 1 9 7 4 )...................................... 5

Saunders v. NARF, C.A. No. C-74-0520 WHO N.D. Calif. . . 4

Seals v. Quarterly County Court, 562 F.2d 390 (6th Cir.

1977) ................................................... 16

Page

l

Smith v. Fletcher, 559 F.2d 1014 (5th Cir. 1977) . . . . 16

Southeast Legal Defense Group v. Adams, 436 F. Supp.

891 (D. Ore. 1 9 7 7 ) .................................. 16

Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. Cal.

1974), aff»d, 550 F.2d 464 (9th Cir. 1977), rev'd on

other grounds, 436 U.S. 547 (1978).......... 13, 14, 15

Williams v. T.V.A., 552 F.2d 691 (6th Cir. 1977) . . . . 6

Other Authorities:

42 U.S.C. § 1988 ................... ..................... 13

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5.................................. 6, 10

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 ( g ) ........................... 5, 6, 10

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(b) 9

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(c) 3

H. Rep. No. 94-1558 (94th Cong., 2d Sess.)................15

122 Cong. Rec. S. 16251 (daily ed., Sept. 21, 1976) . . 15

122 Cong. Rec. H. 12155 (daily ed., Oct. 1, 1976) . . . 15

S. Rep. No. 94-1011 (94th Cong. 2d Sess.).......... 14, 15

Sub Committee on Labor of the Senate Comm. Labor and

Public Welfare, Legislative History of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 (Comm.

Print 1 9 7 2 ).......... ......................... 8, 9

TABLE OF CASES

Page

ii

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

No. 79-4373

ETTA B. SAUNDERS,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

WILLIAM GRAHAM CLAYTOR, JR.,

Secretary of the Navy, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF FOR THE APPELLEE

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether a court is obligated to include a

"cost of living inflation factor" in calculating back pay in

order to make a plaintiff whole for injury suffered by dis

crimination that violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act?

2. Whether a district court may grant attorneys'

fees for all work reasonably done by counsel for a plaintiff

who prevails in the central issue raised in a Title VII action?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Although, the statement of the case by the appellants

is generally complete, appellee wishes to emphasize a number

of points.

FIRST, with regard to the cost of living escalator

used by the district court to adjust the back pay award, the

defendants-appellants do not dispute its accuracy. Thus, they

do not question the fact that because of rampant inflation

since 1973, an adjustment must be made so that 1979 dollars

will have a value equivalent to 1973-78 dollars,

SECOND, with regard to counsel fees, an examination of

the proceedings below demonstrates the interrelationship of the

two issues that were litigated.

1. On February 14, 1972, the Navy found

that plaintiff had been discriminated against with

regard to a promotion. (Excerpts of Record, p. 13)..

2. During the period 1968 to 1973 plaintiff

was a "highly visible and active symbol of equal

opportunity" at the NARF facility (Id., pp, 18-19).

3. On March 19, 1973, plaintiff applied for

the position of Equal Employment Opportunity Specialist,

(Id. at 13) .

4. On April 2, 1973, plaintiff was notified

that her employment in her current job at NARF would be

terminated effective June 1, 1973, as a result of a

reduction in force (RIF). (Id. at 20).

5. On April 9, 1973, she was notified that she

2

would not be considered for the EEO specialist

position. If she had received that job, she would

have remained at NARF despite the RIF. (Id. at 15).

6. The real reason for declaring plain

tiff ineligible for the EEO specialist job was "to

prevent plaintiff from getting the position, and

thereby to force her to leave the Base," and this

action was "the result of discriminatory and/or re

taliatory animus." (Id. at 19).

7. On May 23, 1973, an appeal from the

RIF was filed. (Id. at 21).

8. On July 16, 1973, a discrimination

complaint from the denial of the EEO specialist job

was filed. (Id. at 15).

9. The RIF appeal and the discrimination

complaint processing ended at different times, the

former on November 16, 1973, and the latter on May

23, 1974. (Id. at 21 and 15). Under 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-16 (c) and Civil Service Commission regulations

plaintiff had to file a civil action within 30 days

of each final administrative decision. Thus, she

could not wait until the discrimination complaint was

decided and still file an action based on the RIF

appeal. For this reason, she was forced to file two

separate lawsuits, one on December 14, 1973 (Civil

Action No. C-73-2241 WHO) and one on June 18, 1974

(Civil Action No. C-74-1286 WHO).

3

10. Subsequently, the two cases were assigned to

one judge as being related under the rules of the district

court, and they were consolidated for discovery and trial.

1/

(Id., pp. 41, 47) .

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

A cost of living adjustment to a back pay award

is appropriate and necessary in order to make whole a victim

of discrimination for the injury caused by discrimination.

In Title VII actions a federal government employee is entitled

to the same relief as is a private employee and therefore there

is no bar to such an award against the government.

II.

Plaintiff was the prevailing party with regard to

her central claim. Therefore, there is no basis for appor

tioning the counsel fee awards on the basis of her failure to

prevail on all issues.

1/ These cases were originally consolidated with a number of

other actions involving NARF, including a class action brought

on behalf of all Black, Hispanic, and Filipino employees

(Saunders v. NARF C.A. No. C-74-0520 WHO N.D. Calif,) Subsequent

ly, the class action was settled and these two actions were

severed from the other cases and set for trial. CFxcerpts of

Record, pp. 41, 48).

4

ARGUMENT

r.

The Inclusion of A Cost of Living Factor in

Calculating Back Pay Is A Necessary Part of

Fashioning Relief That Will Make A Victim

of Discrimination Whole,

The government's argument in this case fails

completely either to understand or to address the purpose of

a back pay award in a Title VII case. The Supreme Court in

Albemarle Paper Co, v.. Moody, 422 U,S, 4G5 C1975) explains

that:

It is also the purpose of Title VII

to make persons whole for injuries

suffered on account of unlawful un

employment discrimination , , , ,

Where racial discrimination is con

cerned, "the [district] court has

not merely the power but the duty

to render a decree which will so far

as possible eliminate the dis

criminatory effects of the past , ,

422 U.S. at 418. Specifically, where the injury is of an economic

4a

character, the Court held that -

. . . "The injured party is to be placed,

as near as may be, in the situation he

would have occupied if the wrong had not

been committed." Wicker v. Hoppoch, 6

Wall 94, 99 (1867) .

422 U.S. at 418-19. See also, Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Co. , 424 U.S. 747 (1976), holding that a grant of retro

active seniority needed to make discriminatees whole was per

missible even though such relief was not specifically authorized

by § 2000e-5(g).

In the case of plaintiff appellant, she was dis-

criminatorily denied a position in 1973 that would have prevented

her termination from the federal service. As a result, she re

ceived no salary in the years 1973 until 1979. If she had not

been terminated, that is, if the "wrong had not been committed,"

she would have received, for example, her salary in 1973 in 1973

dollars. As held in Albemarle, the district court was required

to place the plaintiff "in the situation [she] would have

occupied" if she had in fact received her salary in 1973. This

could only be done by factoring in an amount that would make up

for the decrease in the value of money between 1973 and 1979,

when the award was made.

Such a result is fully consistent with many Title VII

decisions in which such items as vacation and sick pay and

adjustments to pension rights are granted. See, e.g ., Pettway

v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211, 263 (5th Cir. 1974),

and cases cited there at notes 155 and 156. Only by providing

5

such relief in addition to straight back pay can a victim of

discrimination be made whole as the Act requires.

The government, however, urges that it is entitled

to special treatment; that its employees may not receive the

full relief to which all other employees who have suffered

from racial discrimination are clearly entitled. However, it

is clear that the government is subject to the same law under

Title VII— whether it relate to procedural, substantive, or

remedial matters— as are all other employers. Thus, in Morton

v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535, 547 (1974), the Supreme Court held

that the 1972 amendments to Title VII resulted in the "substan

tive anti-discrimination law embraced in Title VII" being

applied to the Federal government. Chandler v. Roudebush,425

U.S. 840 (1976),similarly held that the procedures that governed

private Title VII actions applied fully to Federal government

cases by virtue of 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(d), which provides that

the provisions of § 2000e-5(f)-(k) of the statute govern in

such cases. The statutory provision for back pay, § 2000e-5(g),

is, of course, included as one of the governing provisions.

The lower courts have consistently held that the same

law applies to the Federal government as to all other employers

with regard to the maintainability of class actions (Eastland

v. T.V.A., 553 F .2d 364 (5th Cir. 1977); Williams v. T.V.A., 552

F .2d 691 (6th Cir. 1977), when the remedy of back pay should be

awarded (Day v. Mathews, 530 F.2d 1083 (D.C. Cir. 1976), the

determination of the "prevailing party" for the award of counsel

fees (Foster v. Boorstin, 561 F .2d 340 (D.C. Cir. 1977), and other

6

issues (e .g., Grubbs v. Butz, 514 F.2d 1323 (D.C. Cir. 1975)).

Moreover, the Attorney General has acquiesced in the

principal that the same law applies to the government as to

other employers. Indeed, in a policy statement addressed to

all United States Attorneys and agency general counsels on

August 31, 1977, the Attorney General announced:

In a similar vein, the Department

will not urge arguments that rely upon

the unique role of the Federal Govern

ment. For example, the Department

recognizes that the same kinds of relief

should be available against the Federal

Government as courts have found appropri

ate in private sector cases, including

imposition of affirmative action plans,

back pay and attorney's fees. See Copeland_

v. Usery, 13 EPD 1(11,434 (D.D.C. 1976); Day

v. Mathews, 530 F.2d 1083 (D.C. Cir. 1976);

Sperling v. United States, 515 F.2d 465 (3d

Cir. 1975). Thus, while the Department

might oppose particular remedies in a given

case, it will not urge that different

standards be applied in cases against the

Federal Government than are applied in other

cases. (Emphasis supplied.)

(The full statement is appended to appellee's brief at pp, la-3a).

It should be noted that the government does not question

in any way the accuracy of the calculation of the amount necessary

to compensate for inflation. Therefore, it is not disputed that

the amount awarded by the district court does in fact make plain

tiff whole for the financial loss she suffered becaused of dis

crimination. We must turn, then, to the reasons urged by the

government as to why the district court was without the power to

grant the full relief mandated by the statute by making a cost of

7

living adjustment to the back pay award. The central problem

with the government's position is its confusion between what

may or may not be permissible under the Back Pay Act, and what

is required, or at least authorized, under Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act.

A main concern of Congress in 1972 was whether relief

such as back pay could be provided by the Civil Service

Commission in discrimination cases because of the limitations of

the Back Pay Act. This concern was extended to the availability

to federal employees of court review and the same full judicial

relief that private employees enjoyed. Thus, the House Report

v

on the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 notes that:

Despite the series of executive and ad

ministrative directives on equal employment

2/

2/ To a large degree the government's position depends on there

being no difference between interest and a cost of living adjust

ment. The government overlooks the fact that although an award of

interest may be in part to compensate for inflation, that is not

its sole purpose. Interest is basically a fee for the use of

money, and is charged whether or not there happens to be inflation

at any particular time. Congress' decision not to require the

government to pay such a fee does not necessarily evidence an

intent to bar adjustments whose sole purpose is to compensate for

inflation. Thus, assuming for the sake of argument that interest

may not be awarded against the government even in a Title VII

action, it does not follow that other kinds of adjustments are

improper.

3/ The legislative history of the 1972 amendments to Title VII

has been compiled in Sub Comm, on Labor of the Senate Comm, on

Labor and Public Welfare, Legislative History of the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Act of 1972 ( C o m m . Print 1972) (hereinafter

"Legislative History”).

8

opportunity, Federal employees, unlike those

in the private sector to whom Title VII is

applicable, face legal obstacles in obtaining

meaningful remedies. There is serious doubt

that court review is available to the

aggrieved Federal employee. Monetary restitu

tion or back pay is not attainable........

Under the proposed law, court review, back pay,

promotions, reinstatement, and appropriate

affirmative relief is available to employees

in the private sector........

Legislative History at 85. Therefore, federal employees were not

only given the right to go into court and seek the same relief

available to private employees, but the Civil Service Commission

itself was given broad new powers in Section 717(b)(42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-16(b)).

The Senate Committee report described the provision in

terms that leave little doubt as to its plenary nature:

[T]he provision in section 717(b) for

applying "appropriate remedies" is intended

to strengthen the enforcement powers of the

Civil Service Commission by providing

statutory authority and support for ordering

whatever remedies or actions by Federal

agencies are needed to ensure equal employ

ment opportunity in Federal employment. . .

. The Commission is to provide Federal

agencies with necessary guidance and authori

ty to effectuate necessary remedies in

individual cases, including the award of back

pay, reinstatement or hiring, and immediate

promotion where appropriate.

Legislative History at 424. The Conference Committee's section-

by-section analysis of the Act makes it clear that its remedial

provisions are to be read broadly and were not intended to be

limited to those specifically enumerated:

The Civil Service Commission would be authorized

to grant appropriate remedies which may include,

9

but are not limited to, back pay for

aggrieved applicants or employees. Any

remedy needed to fully recompense the

employee for his loss, both financial

and professional, is considered appro

priate under this subsection.

(emphasis added).

Legislative History at 1851. Obviously, the inclusion of a cost

of living inflation factor is a remedy needed to recompense

fully the employee for the financial loss suffered as a result

of discrimination. Just as obviously, it is inconceivable that

Congress intended to grant such broad relief powers to the

Commission and deny them to the courts when one of its main

concerns in giving the right to go to court was the past failure

of the Commission adequately to enforce EEO rights. To the con

trary, the Senate Report states that, "aggrieved employees or

applicants will also have the full rights available in the courts

as are granted to individuals in the private sector under Title

VII." Legislative History at 425.

To summarize, in 1972 Congress did not pass an amend

ment to the Back Pay Act. Rather, it amended Title VII to pro

vide federal employees with a "careful blend of administrative

1/and judicial enforcement powers" intended "to accord federal

V

employees the same right[s]" enjoyed by other employees. This

was accomplished by providing that 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (g) , inter

alia, governs the provision of relief. In Brown v. General

Services Administration, 425 U.S. 820, 832 (1977), the Supreme

Court held that Title VII is the exclusive remedy for federal

employment discrimination and that:

Sections 706(f) through (k), 42 U.S.C,

§§ 2000e-5(f) through 2000e-5(kl . , . ,

which are incorporated "as applicable"

by § 717(d), govern such issues as

47 Brown v. General Services Administration, 425 U.S. 820, 833

(1977) .

5/ Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840, 848 (1976).

10

venue, the appointment of attorneys,

attorneys' fees, and the scope of

relief.

Therefore, the body of law developed in private Title VII cases

governs this case and the district court was fully justified in

relying on it to fashion appropriate relief.

II.

As The Prevailing Party, Plaintiff Was Entitled

to An Award of Counsel Fees for All Work

Reasonably Done in The Litigation of The Case.

In civil rights litigation, and particularly in employ

ment discrimination cases, issues are overlapping and intertwined.

In order to represent a client adequately an attorney must explore

fully every aspect of a case, develop all evidence and present it

to the court. In many cases the plaintiff will not be successful

with regard to every contention. It would be virtually impossible

for the court to arrive at any accurate assessment of the time

spent on each issue and apportion fairly the amount of counsel

fees to be recovered.

The present case is a particularly good example of such

situation. There was in fact one central issue in the case, viz.,

plaintiff had lost her employment at the Naval Air Rework Facility

This came about because of the conjunction of two events that

occurred within a week of each other. Ms, Saunders was informed

on April 2, 1973, that she would be terminated because of a RIF,

and on April 9, 1973, she was notified that she would not be con

sidered for another position that would have allowed her to remain

Naturally, she suspected some connection between the two events,

11

particularly in light of her prior EEO activities..

In April, 1973, of course, plaintiff had no way of

knowing whether the denial of the promotion, the RIF, or

both, had discriminatory motives. Therefore, she had no

choice but to challenge both actions. Because of the struc

ture of the Civil Service Commission regulatory scheme, there

were two separate administrative proceedings that ended at

different times. Thus, instead of there being one lawsuit

filed, plaintiff had to file two at different times. Since

the two actions involved the same issue— the termination of her

employment— they were consolidated and tried as if they were

one action. The interrelationship of the RIF and the promotion

denial meant that counsel worked on them at the same time.

Plaintiff's suspicions that there was a relationship

between the RIF and the promotion denial proved correct. The

district court held that the refusal to consider her for the

promotion that would have allowed her to stay was to prevent

her from getting the job and thereby to force her to leave the

Base as a result of the RIF, The motives behind the action

were both to discriminate against her and to commit reprisal

against her because of her EEO activities. Although the RIF

£/

itself was not the result of discrimination, it was seized upon

6/ The district court did hold, however, that placement of

other employees in derogation of plaintiff's rights resulted,

in part, from defendants' administrative inefficiency although

discrimination or retaliation was not involved. Excerpts of

Record, p. 22.

12

by the discriminating officials as the way to get rid of the

plaintiff when they denied her the promotion. Thus, in every

sense of the word, plaintiff prevailed on the central claim

in the case— that she was forced to leave the base because of

"discriminatory and/or retaliatory animus,"

The interrelationship of issues in civil rights

cases was recognized by Congress when it passed the Civil

Rights Attorneys' Fee Act of 1976 C42 U.S.C, § 19881, Thus,

the legislative history of that statute makes it clear that

counsel fee awards should not be based on the proportion of

7/

the case that has been won. The Senate Report on the Act

discusses the standards which should be used in determining

counsel fee amounts and states:

The appropriate standards, see Johnson

v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F,2d

714 (5th Cir. 1974), are correctly

applied in such cases as Stanford Daily

v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. Cal,

1974); Davis v. County of Los Angeles,

8 E.P.D. 1(9444 (D.C. Calif, 1974); and

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 66 F.R.D. 483 (W'.D.N.C. 1975)

7/ The Supreme Court has relied on the legislative history of

the 1976 Act in interpreting Title IX of the Education Amendments

of 1972, as well as Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, In

Cannon v. University of Chicago, U.S. , 60 L ,Ed, 2d 56Q,

569 n. 7 (1979), it was noted that:

Although we cannot accord these remarks the weight

of contemporary legislative history, we would be

remiss if we ignored these authoritative expressions

concerning the scope and purpose of Title IX and its

place within "the civil rights enforcement scheme"

that successive Congresses have created over the past

110 years.

Similarly, the court in Parker v. Califano, 561 F.2d 320, 339

(D.C. Cir. 1977), looked to the legislative history of the 1972

Act "'as a secondarily authoritative expression of expert opinion.'"

13

. . . . In computing the fee, counsel

for prevailing parties should be paid,

as is traditional with attorneys com

pensated by a fee-paying client, "for

all time reasonably expended on a

matter," Davis, supra, Stanford Daily,

supra, at 684.

S. Rep. No. 94-1011 (94th Cong. 2d Sess.), p. 6.

The quoted language from Davis relates directly to

the question of proportionate fees. The full quote is:

It also is not legally relevant that

plaintiffs' counsel expended a certain

limited amount of time pursuing certain

issues of fact and law that ultimately

did not become litigated issues in the

case or upon which plaintiffs ultimately

did not prevail. Since plaintiffs pre

vailed on the merits and achieved ex

cellent results for the represented class,

plaintiffs' counsel are entitled to an

award of fees for all time reasonably ex

pended in pursuit of the ultimate result

achieved in the same manner that an

attorney traditionally is compensated by

a fee-paying client for all time reasonably

expended on a matter.

8/

8 EPD 119445, p. 5049. Similarly, in Stanford Daily, at the page

cited in the legislative history, the district court rejected

the position taken by some federal courts, "that hours spent on

the litigation of unsuccessful claims should be deducted from

the number of hours upon which an attorneys' fee award is

computed." The Court held:

However, several recent decisions, adopting

a different tack, deny fees for clearly

meritless claims but grant fees for legal

work reasonably calculated to advance their

clients' interests. These decisions

acknowledge that courts should not require

attorneys (often working in new or changing

areas of the law) to divine the exact para-

8/ Stanford Daily v. Zurcher's holding on counsel fees was

summarily affirmed by this Court. 550 F.2d 464 (9th cir. 1977),

rev'd on other grounds, 436 U.S. 547 (1978).

- 14 -

meters of the courts' willingness to

grant relief.- See, e .g., Trans World

Airlines v, Hughes, 312 F. Supp. 478

(S.D.N.Y. 1970), aff'd with respect

to fee award, 449 F.2d 51 (2nd Cir.

1971), rev'd on other grounds, 409 U.S.

363, 93 S.Ct. 648, 34 L.Ed.2d 577

(1973). One Seventh Circuit panel,

for example, allowed attorneys' fees

for legal services which appeared un

necessary in hindsight but clearly

were not "manufactured." Locklin v.

Day-Glo Color Corporation, 429 F.2d

873, 879 (7th Cir. 1970) (concerning

fees for antitrust counterclaims).

64 F.R.D. at 684.

When one considers the overall intent of Congress in

passing the various counsel fee provisions it must be concluded

that the allocation of counsel fees on the basis of the percent

of the case won would contravene that intent because it would

have a discouraging affect on the willingness of attorneys to

become involved in civil rights litigation. The legislative

history of § 1988 is replete with references to the difficulty

in maintaining civil rights cases because of their costs, and

the necessity for plaintiffs being able to retain attorneys

with the assurance that they will be paid on the same basis as

they would in comparable civil litigation. See, e .g ., S. Rep.

No. 94-1011 (94th Cong., 2d Sess.) pp, 2, 6; H. Rep. No. 94-1558

(94th Cong., 2d Sess.) pp. 2-3; 122 Cong. Rec. S» 16251 (daily

ed., Sept. 21, 1976) (remarks of Sea. Scott); Id., at 16252

(remarks of Sen. Kennedy); 122 Cong. Rec. H. 12155 (daily ed.,

Oct. 1, 1976)(remarks of Rep. Seiberling).

Other courts have, following the above considerations,

interpreted various civil rights attorneys' fee provisions in

15

the same way. See, e .g., Donaldson v. O'Connor, 454 F. Supp.

311, 316 (N.D. Fla. 1978), in which the court discussed the

above legislative history and concluded, ". , . Congress

clearly could not have contemplated that an award of attorney's

fees should depend upon the extent to which a plaintiff pre

vails in gaining all the relief requested . . .", citing Seals

v. Quarterly County Court, 562 F.2d 390 (6th Cir. 1977); Howard

v. Phelps, 443 F. Supp. 374 (E.D. La. 1978); and Southeast Legal

Defense Group v. Adams, 436 F. Supp. 891 (D. Ore. 1977); See

also, Brown v. Bathke, 588 F.2d 634 (8th Cir. 1978); Smith v.

Fletcher, 559 F.2d 1014 (5th Cir. 1977); Dawson v. Pastrick,

____F.2d ___, 19 E.P.D. 119270 C7th Cir. 1979); Cooper v. Curtis,

16 EPD 118099 (D.D.C. 1978); Palmer v. Rogers, 10 EPD 1[10,499

(D.D.C. 1975).

In sum, plaintiff first urges that she prevailed

completely on the central issue in this litigation, her claim

that she was discriminated against when her employment with the

Department of the Navy was ended. Second, even if it were

decided that she did not prevail on all issues, she still is

entitled to recover a full award of fees in light of

Congressional intent and the purpose of the counsel fee statute,

16

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision of the

district court should be affirmed.

HOWARD MOORE, JR.

Moore & Bell

The London Bldg., Third Floor

160 Franklin Street

Oakland, California 94607

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

BILL LANN LEE

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, N.Y. 10019

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 17th day of October,

1979, I served the foregoing Brief for the Appellee by causing

copies to be mailed to:

Alice Daniel, Acting Assistant Attorney

General

Robert E. Kopp

Michael Jay Singer

Civil Division, Appellate Staff

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

G. William Hunter, United States Attorney

450 Golden Gate Avenue

San Francisco, California 94102

IHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellee

17

*

MEMORANDUM FOR UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS

'AND AGENCY GENERAL COUNSELS

i Title VII Litigation

In 1972, as additional evidence of our Nation's derar

“ ■nation to guarantee equal rights to all citizens Confess

amended Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to p ^ i d '

Federal empioyees and applicants for Federal employment with

of Justice eof°rCeable uqUSl emP1 * *°yniGnt rights . ? The^Department £ Justice, or course, has an important role in the aff'irman'vp

P5blicesIctors ^ !CC'Kin b°t;' the PrlvatJ and

we must ensure'that ■

representational functions as defense attorneys for aL^oies

m suits utter the Act in a way that will be‘supporti!e nf U d

consistent with the Department's broader obligations to

as plrt ofUwha?Pw?htU^ lt7 l2WS: This ">™orar,dum is issued

?o this end 3 conclnulnS by the Department

s j^ -^ J S S W £ ,'% .S ig«5 S ffygy*

enforcement as it has conferred upon employees and I k

in private industry and in state and local government

I4 " A UHS ' 535 (1974)' Cha"dW r v. Roudebush.rt o40 (19/6) . And, as a matter o F ^ I I ^ r ~the~Federa1

Government should be willing to assume for its L I f n

than6those 1frt:i0n̂ Wlth. resPect to equal employment opportunities

government employers lmP°Se UP°n Private and sta« “ d Weal

of this

the policy, the Department, wneneverIn furtherance

ctle same position in interpreting Title VII

in defense of Federal employee oases as it has taken and will take m private or state and local---- — . UL bLaie and local government enmlovpp

For example, where Federal employee! and appli!a£« M e t

A

)!

&

- 2 -

crxte;ria of Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

they are also entitled to the same class rights as are

private sector employees. Albemarle PaDer Co. v. Moody

422 U.S. 405, 414 (1975) . Further, the*Denartment of

Justice has_acquiesced in the recent rulings of the •

fifth and Sixth Circuit Courts of Appeals that it is'

unnecessary for unnamed class members to exhaust their

administrative remedies as a prerequisite to class

membership. Eastland v. TVA 553 F.2d 364 (5th Cir. 1977) -

Williams v̂ _ TVA, ___F.2d___ (6th Cir. 1977). Consequently,

we wall no longer maintain that each class member in a

Title VII suit must have exhausted his or her administrative remedy.

In a similar vein, the Department

arguments that rely upon the unique ro

Government. For example, the Departme

the same kinds of relief should be ava

Federal Government as courts have foun

private sector cases, including imposi

action plans, back pay and attorney's

X- Userv , 13 EPD Ull,434 (D.D.C. 1976)530 F-2d 1083 (DC> cir_ ig76). Snerli

515 F.2d 465 (3d Cir. 1975). Thus, wn

might oppose particular remedies in a

not urge that different standards be a

the Federal Government than are applie

will not urge

le of the Federal

nt recogni7.es that

ilable against the

d appropriate in

tion of affirmative

fees. See Copeland

; Day v. Hat fie vs ,

ng Dnited States,

ile tiie Department

given case, it will

pplied in cases against

d in other cases.

The Department, in other respects, will also attempt

the- underlying purpose of Title VII. For example

the 1972 amendments to Title VII do not give the Government

a to file a civil action challenging an agency finding

° discrimination. Accordingly, to avoid any appearance on

the Government's part of unfairly hindering Title VII law

suits, the Government will not attempt to contest a final

agency or Civil Service Commission finding of discrimination

by seeking a trial de novo in those cases where an employee

who has been successful in proving his or her claim before

either the agency or the Commission files a civil action

seeking only to expand upon the remedy proposed by such final decision.

3

The policy set forth above does not reflect, and should

not be interpreted as reflecting, any unwillingness on the

part of the Department to vigorously defend, on the merits

claims of discrimination against Federal agencies where

appropriate. It reflects only a concern that enforcement of

the equal opportunity laws as to all employees be uriform ' and consistent.

In addition to tne areas discussed above, the Department

of Justice is now undertaking a review of the consistency of

other I m p o s i t i o n s advanced by the Civil Division in

efendmg Title VII cases with those advocated by the Civil

Rights Division in prosecuting Title VII cases. The objective

this review is to ensure that, insofar as possible, they will

e consistent, irrespective of the Department’s role as either

plaintiff or defendant under Title VII. As a part of this

review, the Equal Employment Opportunity Cases" section of

the Civil Division Practice Manual (§3-37), which contains

tne Department s position on the defense of Title VII actions

brought against the Federal Government, is being revised.

•nen this revision is completed, the new section of the Civil

Division Practice Manual will be distributed to all

United States Attorneys’ Offices and will replace the present

section. Eacn office should rely on the revised section of

the Manual for guidance on legal arguments to be made in Title

u h ^ l h n l' In order to ensure consistency, any legal arguments which are not treated in the Manual should be referred to the

Civi^ Division for review prior to their being advocated to the court.

01

v :

This policy statement has been achieved through the

cooperation of Assistant Attorney General Barbara Babcock

°Z the Civil Division who is responsible for the defense of

these Federal employee cases, and Assistant Attomev General

Drew Days of the Civil Rights Division who is my principal

adviser on civil rights matters. They and their Divisions

will continue to work closely together to assure that this

policy is effectively implemented.

GRIFFIN B. BELL

August 31, 1977

D O J -1 977-09