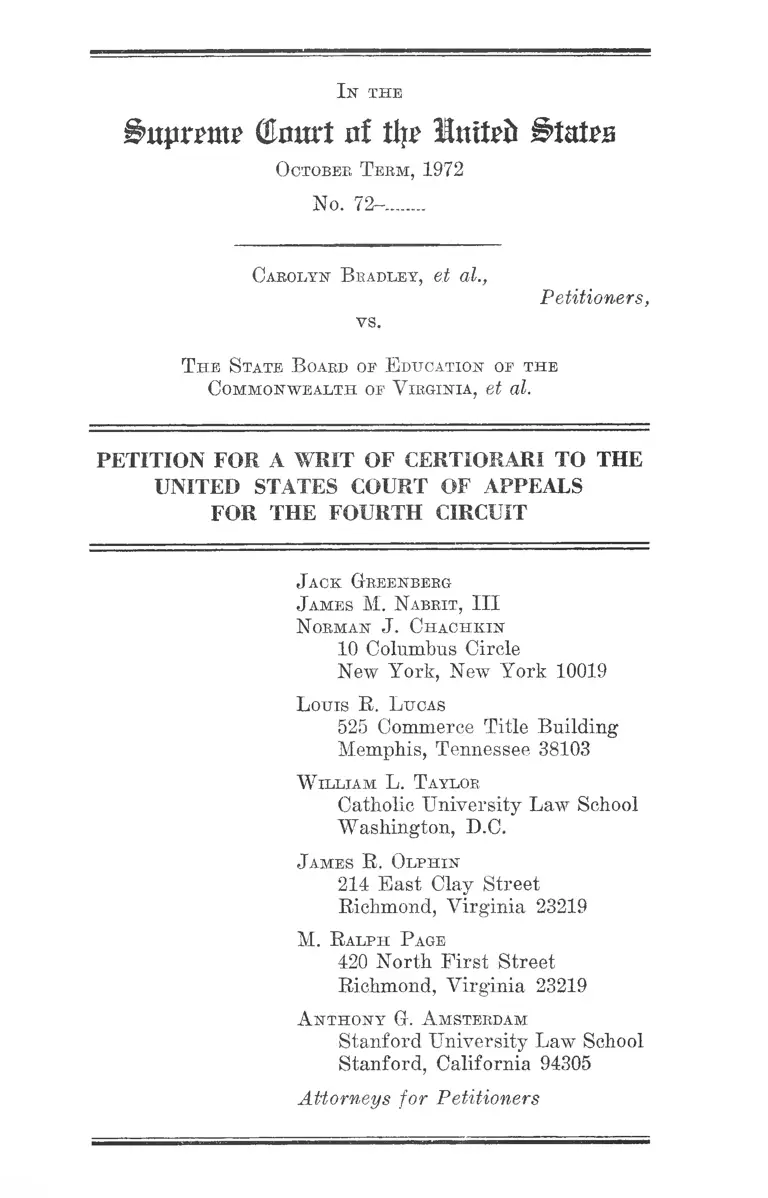

Bradley v. State Board of Education of Virginia Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bradley v. State Board of Education of Virginia Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1972. bd0c9fa8-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9e37f6c9-58b8-4dc2-9ce2-473ffede6aa0/bradley-v-state-board-of-education-of-virginia-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

1st t h e

g>tfpr£nt£ (Emtri nf % Inttefc States

O ctober T e r m , 1972

No. 72-.......

Carolyn B radley , et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

T h e S tate B oard of E ducation of t h e

C o m m o n w e a l t h of V ir g in ia , et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

J a ck G r een berg

J a m es M. N a brit , III

N orm an J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Louis R. L ucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

W il l ia m L. T aylor

Catholic University Law School

Washington, D.C.

J a m es R. Ol p h in

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

M. R a l p h P age

420 North First Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

A n t h o n y G. A m sterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below...................... -....................................... 1

Jurisdiction ....................................................-............... 3

Question Presented........................................... -........... - 4

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 4

Statement ..........—.............................................-............ 5

A. Background of the Litigation: School Segre

gation and Desegregation in Virginia .............. 5

B. The Greater Richmond Community................. 15

1. Schools in the Community .......................... 18

2. Changing Internal Demography................. 21

C. The Litigation Below ............................................. 26

1. Prior Proceedings ..................... -................. 26

2. Proceedings on the 1170 Motions for Fur

ther Relief .................................................... 27

3. Conditions at the Time the District Court

Rendered Its Judgment................................ 34

4. The District Court’s Ruling.................... —- 36

Reasons for Granting the Writ ........................ —........ 40

I. The Fourth Circuit’s Decision Balkanizing

Brown v. Board of Education Is of Grave and

Widespread Importance Because It Broadly

Denies the Promise of Brown to the Children

of the Metropolitan Ghetto ................................ 46

11

PAGE

A. The Fourth Circuit Essentially Confines Fed

eral Court Eemedies for Unconstitutional

School Segregation Within the Limits of In

dividual School District Boundary Lines..... 46

B. The Decision Critically Impairs the Powers

of the Federal Courts to Do the Vital and

Difficult Job of Desegregating the Schools of

the Nation’s Metropolitan Ghettos ................ 54

II. Questions Raised by the Fourth Circuit’s Deci

sion Require Authoritative Resolution by This

Court, for the Guidance of the Lower Courts in

Numerous Cases ................. 64

A. The Decision Conflicts With Decisions in

Other Circuits ................................................ 64

B. The Decision Has Immediate Implications for

the Efficient Conduct of Litigation Pending

in Seven Circuits.......................... 65

III. This Case Presents an Excellent Opportunity

for the Court to Consider, and to Guide the

Lower Courts in Consideration of, the Question

of Multi-District Desegregation Decrees in the

Metropolitan Context....... ....................... 67

IV. The Fourth Circuit’s Decision Departs From

Settled Principles and Calls Into Question Doc

trines That Are Indispensable Safeguards of

the Right of Racial Equality ............ ................ 74

Ill

PAGE

A. The Decision, Focusing Only Upon Individual

School Districts, Ignores the Affirmative Ob

ligation of the State to Comply With the

Commands of the Fourteenth Amendment

and of Brown v. Board of Education ........ . 74

B. The Court’s Extension of the Tenth Amend

ment Into Conflict With the Fourteenth Dis

turbs Established Law .............................. . 77

C. The Court Reintroduces Into the Law of the

Fourteenth Amendment a Test of Invidious

“Motivation” or “Purpose,” Which This

Court and the Lower Courts Have Rejected

in Related Contexts as Inadequate to Protect

the Right of Equality ................................... 80

D. The Decision Unduly Curbs the Vital Power

of the Federal Courts to Remedy Unconstitu

tional School Segregation, and Trammels the

Traditional Flexibility of Equitable Relief

That Was Reconfirmed in School Cases by

Swann .................................. .......................... 83

C o n c lu sio n ........................................................................................... 88

T able op A u t h o r it ie s

Cases:

Adkins v. School Bd. of Newport News, 148 F. Supp.

430 (E.D. Va.), affd 246 F.2d 325 (4th Cir.) cert.

denied, 355 U.S. 855 (1957) ................ ................... 10,12n

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19

(1969) ............................................................ 28n, 42n, 53n

Allen v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward County,

207 F. Supp. 349 (E.D. Va. 1962) ............................ 6n

IV

PAGE

Arthur v. Nyquist, Civ. No. 1972-325 (W.D. N.Y.) .... 66n

Atkin v. Kansas, 191 U.S. 207 (1903) ........................ 79n

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) ...... ..................... 78n

Board of Supervisors v. County School Bel., 182 Ya.

266, 28 S.E.2d 698 (1944) ......... ................ ............. 6

Bradley v. Milliken, C.A. No. 35257 (U.S.D.C., E.D.

Mich.), on appeal, No. 72-8002 (6th Cir.) ........... ...... 64n

Bradley v. Milliken, 338 F. Supp. 582 (E.D. Mich.

4971) .... -........- ------------ —-...... - - -------- 61n, 64n

Bradley v. School Bd. of Bichmond, 382 U.S. 103

(1965) ........ ....................... ......... .... .........................5n, 26

Bradley v. School Bd. of Bichmond, 462 F.2d 1058 (4th

Cir. 1972) ______ _____________ ___ _____ _ 3

Bradley v. School Bd. of Bichmond, 456 F.2d 6 (1972) 3

Bradley v. School Bd. of Bichmond, 345 F.2d 310 (4th

Cir. 1965), rev’d 382 U.S. 103 (1965) ...............3,12n, 26

Bradley v. School Bd. of Bichmond, 317 F.2d 429 (4th

Cir- 1963) ..--- -------------------------- -------- ------- ----3, 26

Bradley v. School Bd. of Bichmond, 338 F. Supp. 67

(E.D. Va. 1972) ----- ------ ----- ---- ------ --- ----- -passim

Bradley v. School Bd. of Bichmond, 325 F. Supp. 828

(E.D. Va. 1971) ............................. .......... .....3 , 29n, 34

Bradley v. School Bd. of Bichmond, 324 F. Supp. 456

(E.D. Ya. 1971) ...... ............. .............. ..... ......... ....... 3

Bradley v. School Board of Bichmond, 324 F Supp

439 (1971) - .......................-......-....-...... .......... .........2, 32n

Bradley v. School Board of Bichmond, 324 F Supp

401 (1971) .................. .......-.... -............................ —2, 32n

Bradley v. School Board of Bichmond, 324 F Supp

396 (1971) ........................ .................... ............. .... _.2,32n

Bradley v. School Bd. of Bichmond, 51 F.B.D. 139

(E.D. Ya. 1970) ......... ........................................ 2,30,31

V

PAGE

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 317 F. Supp. 555

(E.D. Va. 1970) ......................................................... 2

Brinkman v. Gilligan, Civ. No. 72-137 (S.D. Ohio) ..... 66n

Broughton v. Pensacola, 93 U.S. 266 (1876) .............. 79n

Brown v. Bd. of Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955) ..............passim

Brown v. Bd. of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ..........passim

Brown v. Swann, 35 U.S. (10 Pet.) 497 (1836) .......... 84n

Calhoun v. Cook, 451 F.2d 583 (5th Cir. 1971) „..61n, 64n

Calhoun v. Cook, 430 F.2d 1174 (5th Cir. 1970) .......... 28n

Calhoun v. Cook, Civ. No. 6298 (N.D. Ga.) ............... . 66n

Calhoun v. Cook, 332 F. Supp. 804 (N.D. Ga. 1971) .... 64n

Camp v. Boyd, 229 U.S. 530 (1913) ............................ 84n

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396 U.S.

290 (1970) ____ _____ ______ _____ _____ _____ 28n

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F.2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956), cert.

denied 353 U.S. 910 (1957) ...... ............... ................. 12n

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 (1950) _________ __ 81

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167 (2d Cir.

1972) __ ___ _____ ____ _________ ____ _______ 81

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School Dish,

No. 71-2397 (5th Cir., Aug. 2, 1972) ........ .............. . 81n

City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U.S. 704 (1930) 24n

Comanche County v. Lewis, 133 U.S. 198 (1890) ...... 79

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ......................... . 75

County School Bd. of Prince Edward County v. Griffin,

204 Va. 650, 133 S.E,2d 565 (1963) ................... .....9n, 11

Crawford v. Board of Educ. of Los Angeles, No. 822-

854 (Super. Ct. Cal., Jan. 11,1970) ..... ........ ............ . 61n

Davis v. Board of School Commr’s, 402 U.S. 33 (1971)

37n, 40n, 51n, 54n,

62n, 83n, 85n, 86n

V I

PAGE

Direction der Disconto-Gesellschaft v. United States

Steel Corp., 267 U.S. 22 (1925) ................................ 41n

Evans v. Buchanan, Civ, No. 1816 (D. Del.) ................. 66n

Ford Motor Co. v. United States, 405 U.S. 562 (1972) 84n

Franklin v. Quitman County Bd. of Educ., 288 F. Supp.

509 (N.D. Miss. 1968) .................................................. 76n

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969) .. 25n

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ...... 79n, 80, 81

Graham v. Folsom, 300 U.S. 248 (1906) ..................... 78n

Green v. County School .Bd., Va., 391 U.S. 430 (1968)

5n, 14, 27, 40n, 53n, 54n,

62n, 82n, 85n

Green v. School Bd. of Roanoke 304 F.2d 118 (4th Cir.

19(32) ........................................................................... 12n

Griffin v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward County,

377 U.S. 218 (1964) ............................ 5n, 6n, 11, 75n, 76n

Griffin v. State Bd. of Educ., 296 F. Supp. 1178 (E.D.

Va. 1969) ............... l ln

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ...... 25n, 81

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 197 F. Supp. 649

(E.D. La. 1961) (three-judge court), aff’d 368 U.S.

515 (1962) ..... 76n

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ., 429 F.2d 364 (8th Cir.

1970) _....65n, 68n

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ., 410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir.

1969) 65n,68n,79n

Harrison v. Day, 200 Va. 439, 106 S.E.2d 636 (1959) .. 9n

Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, 461 F.2d 1171 (5th Cir.

1972) ........................................................................... 81

Haycraft v. Board of Educ., Civ. No. 7291-G (W.D.

Ky-) ...................................................................... 66n

Vll

PAGE

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321 (1944) ............ ....... 84n

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist.,

433 F.2d 387 (5th Cir. 1970) ........... ............... ............ 69n

Higgins v. Grand Rapids Bd. of Edue., Civ. No. 6389

(W.l). Mich.) ....... ................................................... . 66n

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401 (D.D.C. 1967)

afPd sub nom. Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F,2d 175 (D.C.

Cir. 1969) ........................................ -..............-..... . 81

Hunter v. Pittsburgh, 207 U.S. 161 (1907) ...... .......78, 79

James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (E.D. Ya.) appeal

dismissed, 359 U.S. 1006 (1959) ........ .............. ......... 9n

Jones v. School Bd. of Alexandria, 278 F.2d 72 (4th

Cir. 1960) ............ .......... ..... ........................... ........... 12n

Kennedy Park Homes Assn., Inc. v. City of Lacka

wanna, 436 F.2d 108 (2d Cir. 1970) ........... ............. 81

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 448 F.2d 746 (5th

Cir. 1971), 455 F.2d 978 (5th Cir. 1972) ................. 65n

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 267 F. Supp. 458,

aff’d sub nom. Wallace v. United States, 389 U.S.

215 (1967) ....... ................ .................. -.......... 13n, 76n

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ........ 86

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) — ................... 87n

Lumpkin v. Dempsey, Civ. No. 13,716 (D. Conn., Jan.

22, 1971) ........ ........................-.................... ............. 66n

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) .............. 87n

McLeod v. County School Bd. of Chesterfield County,

Civ. No. 3431 (E.D. Va.) ............................. .......- .... 19n

McNeese v. Board of Educ., 373 U.S. 668 (1963) ...... 12n

Mobile v. Watson, 116 U.S. 289 (1886) ....... ................. 79n

Morgan v. Hennigan, Civ. No. 72-911-G (D. Mass.) .... 66n

Mount Pleasant v. Beckwith, 100 U.S. 514 (1879) ...... 79n

V l l l

PAGE

N.A.A.C.P. v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 (E.D. Ya. 1968),

rev’d on other grounds sub nom. Harrison v.

N.A.A.C.P., 360 U.S. 167 (1959) .......................... .....23n

North Carolina State Board of Educ. v. Swann, 402

U.S. 43 (1971) .................................... ..........54n, 62n, 68n

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, Civ. No.

3931 (W.D. Tenn., Dec. 10, 1971), afPd No. 72-1630

(6th Cir., Aug*. 29, 1972) ................. ......................... 26n

Palmer v. Thompson, 403 U.S. 217 (1971) ..................... 81

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) .................. ...... 79n

Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., 330 F. Supp.

837 (W.D. Tenn. 1971), order aff’d 6th Cir., No.

71-1966 (Sept. 21, 1972) ................. ......................... 65n

Shapleigh v. San Angelo, 167 U.S. 646 (1897) .............. 79

Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., 311 F. Supp.

501 (C.D. Cal. 1970), order denying intervention of

additional parties aff’d, 427 F.2d 1352 (9th Cir.

1970) .................................. ................ ...................... 61 n

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971) ........................................................passim

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 431

F.2d 138 (4th Cir. 1970), rev’d 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ....... 28

Taylor v. Coahoma County School Dist., 330 F. Supp.

174 (N.D. Miss.), aff’d 444 F.2d 221 (5th Cir 1971) .. 65n

Thompson v. County School Bd. of Hanover County,

252 F. Supp. 546 (E.D. Va. 1966) ............................. 22n

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970) ......................... 81

United States v. Armour & Co., 402 U.S. 673 (1971) .... 85n

United States v. Board of Educ. of Baldwin County,

423 F.2d 1013 (5th Cir. 1970) ................................... 38n

IX

PAGE

United States v. Board of School Comm’rs, 332 F.

Supp. 655 (S.D. Ind. 1971), mandamus denied, No.

72-1063 (7th Cir., Feb. 2, 1972), cert, denied, 32 L.ed.

2d 805 (1972) ................................................ .......62n,66n

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U.S. 173

(1944) .......................................................................... 85n

United States v. Georgia, Civ. No. 12972 (N.D. Ga.,

Dec. 17, 1969), rev’d on other grounds, 428 F.2d 377

(5th Cir. 1970) __________ _______ __________ _ 13n

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372

F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966); on rehearing' en banc, 380

F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967) .......... ................................ 75

United States v. Loew’s, Inc., 371 U.S. 38 (1962) ___ 85n

United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., 334 U.S. 131

(1948) .................................... ..................-________ 85n

United States v. School Dist. No. 151, 286 F. Supp.

786 (N.D. 111. 1967), aff’d 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir.

1968), on remand, 301 F. Supp. 201 (N.D. 111. 1969) ..61n

United States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. of Educ., 33

L.ed.2d 75 (1972) .................................................. 79n, 83

United States v. Texas, 321 F. Supp. 1043 (E.D. Tex.

1970), 330 F. Supp. 235 (E.D. Tex.), supplemental

order of April 19, 1971 (unreported), modified and

aff’d 447 F.2d 441 (5th Cir.), stay denied, 404 U.S.

1206 (1971) (Mr. Justice Black, Circuit Justice),

cert, denied, 404 U.S. 1016 (1972) ...... .......13n, 65n, 76n

United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp., 391

U.S. 244 (1968) ......... ................................ .............. 85n

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 340 U.S.

76 (1950) .............- .................................................... 85n

Wheeler v. Durham City Bd. of Educ., Civ. No. C-54-

D-60 (M.D. N.C.) ........ ..................... .................. .... 66n

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, 33 L.ed.2d

51 (1972) ................... ................... 5n, 7n, 67, 76n, 79n, 83

X

Statutes .* PAGE

28 U.S.C. § 2281 ..... . 32n

Rule 19, F.R.C.P. ....... ..................... ................................... 29

Virginia Constitution of 1971, Art. V III, §§ 1 -7 ........... 4

Virginia Constitution of 1902, §§ 129, 130, 132, 133 .... 4

Va. Code Anno. §§ 22-1, -2, -7, -30, -34, -100.1 through

-100.12 (Repl. 1969) ....................................................... 4

Va. Code Anno. §§ 22-1.1, -2, -7, -21.2, -30, -32, -100.1,

-100.3 through -100.11, -126.1, -127 (Supp. 1972) ..4, 39, 67n

Va. Code Anno. §22-188.51 (Repl. 1969) ....................... 9n

Va, Acts 1956, Ex. Sess., ch. 68, p. 69, 1 Race Rel. L.

Rep. 1103 .................................................................. 9

Va, Acts 1956, S.J.R. 3, p. 1213, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep.

445 ..................... 9

Other Authorities:

[1972] Ayer Directory of P ublications ....................... 73n

117 Cong. Rec. S17516-S17518 (daily ed., Nov. 3, 1971) 60n

Hearings Before the Senate Select Committee on Equal

Educational Opportunity, 92d Cong., 1st Sess., on

Equal Educational Opportunity, Part 21, Metropoli

tan Aspects of Educational Inequality (Nov. 22, 23,

30, 1971), 10913 ................................... ....... .......... ....... 58n

National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders,

Report (G.P.O. 1968 0-291-729) (1968) .......55n, 56n, 59n,

60n,63n

Note, Merging Urban and Suburban School School

Systems, 60 Geo L. J. 1279 (1972) ............................... 66n

Riven & Cloward, Regulating the P oor (1971) ........... 56n

Rand, McNally & Co., [1972] Commercial Atlas &

Marketing Guide ................................................. 72n

SI

PAGE

K. Taeuber and A. Taeuber, N egroes in C it ie s (1965)- 25n

United States Bureau of the Budget, Office of Statis

tical Standards, S tandard M etro po lita n S tatistical

A reas (1967) ..................................................-.........— 55n

United States Comm’n on Civil Rights, 1 R e p o r t :

R acial I solation in t h e P u b lic S chools (G.P.O.

1967 0-243-637) (1967) ........................... ......57n, 62n, 63n

U .S . C om m ’n o n Civil Rights, S urvey o f S chool De

segregation in t h e S o u t h e r n and B order S tates

1965-1966 (1966) ..................................................... 12n

U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, C iv il R ig h t s , U.S.A.

— P u b lic S chools, S o u t h e r n S tates (1962) .......... 12n

United States Dep’t of Commerce, Bureau of the Cen

sus, Ce n s u s T racts, C e n s u s of P o pu la tio n and

H o u sin g , Richmond, Va. SMSA (PHC(1)-173)

(1972) ......................................................................... 72n

United States Dep’t of Commerce, Bureau of the Cen

sus, Ce n s u s of P o p u l a t io n : 1970 (G.P.O. PCH(2)-48

1971) .................................................................. -........ 21n

United States Dep’t of Commerce, Bureau of the Cen

sus, C e n s u s of P o pu la tio n : 1970 (G.P.O. PC(1)-B48,

October 1971) ............................................ .............. - 58n

United States Dep’t of Commerce, Bureau of the Cen

sus, 5 Ce n s u s of G o v e r n m e n t s : 1967 (1968) ---- --- 61n

United States Dep’t of Commerce, Bureau of the Cen

sus, I Ce n s u s of P o p u l a t io n : 1960 (G.P.O. 1961) .... 58n

United States Dep’t of Commerce, Bureau of the Cen

sus, II C e n su s of P o p u l a t io n : 1950 (G.P.O. 1952) .... 58n

I n t h e

Olourt xti lUmttb States

O ctober T e r m , 1972

No. 72-......

Carolyn B radley , et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

T h e S tate B oard of E ducation of t h e

C o m m o n w ea lth of V ir g in ia , et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment and decision of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, entered in the above-

captioned matter on June 5, 1972.

Opinions Below

The opinions of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Cir

cuit are reported at 462 F.2d 1058* and are reprinted at pp.

557-602 of the Appendix to the Petition for Writ of Cer

tiorari seeking review of this judgment filed in this Court by

the School Board of the City of Richmond, Virginia, et al.,

as petitioners.1 The opinion of the United States District

* Parallel citations are given within this Petition only for the

district court opinion, however, since the advance sheet containing

the Court of Appeals’ opinion was received on the day of printing.

1 Citations throughout this Petition in the form “A.—” refer to

the separate appendix of opinions below and relevant state statutes

filed by the Richmond School Board in connection with its petition.

The transcript of the August-September, 1971 hearings on the

2

Court for the Eastern District of Virginia of January 5,

1972, and its implementing order of January 10,1972, which

was reversed by the Court of Appeals, are reported at

338 F. Supp. 67 and are reprinted in the same Appendix

at pp. 164-545.

Other opinions and orders of the Courts below related to

this litigation are reported or reprinted as follows:

1. District court opinion and order entered August 17,

1970, approving interim plan of desegregation for Rich

mond, reported at 317 F. Supp. 555 and reprinted at A. 1-47.

2. District court opinion and order entered December 5,

1970, granting motion for joinder of additional parties de

fendant and directing the filing of an amended complaint,

reported at 51 F.R.D. 139 and reprinted at A. 48-57.

3. District court opinion of January 8, 1971 denying mo

tion to recuse, reported at 324 F. Supp. 439 and reprinted

at A. 58-90.

4. Unreported district court order of January 8, 1971,

as entered nunc pro tunc January 13, 1971, on pre-trial

motions, reprinted at A. 91-93.

5. Unreported district court order of January 13, 1971

on additional pre-trial motions, reprinted at A. 94-97.

6. District court opinion and order entered February

10, 1971, declining to convene three-judge court, reported

at 324 F. Supp. 396 and reprinted at A. 98-106.

7. District court opinion and order entered February 10,

1971 denying motion to dismiss as to certain defendants in

issues raised by joinder of the state and county defendants will be

cited by individual volume letter designation, e.g., “Tr. A-10.”

Transcripts of earlier hearings are consecutively paginated and

will be cited by date, e.g., “Tr. 8/8/70 102.” Exhibit references are

to the August-September, 1971 hearings only.

3

their individual capacities, reported at 324 F. Supp. 401

and reprinted at A. 107-09.

8. District court opinion and order entered April 5,

1971 approving further desegregation plan for Richmond

schools, reported at 325 F. Supp. 828 and reprinted at

A. 110-55.

9. Unreported district court opinion and order entered

July 20, 1971 denying renewed motion to convene three-

judge court, reprinted at A. 156-62.

10. Unreported district court order entered September

15, 1971 denying evidentiary motion, reprinted at A. 163.

11. Unreported district court opinion and order issued

January 19, 1972 denying stay of January 10 order, re

printed at A. 546-52.

12. Court of Appeals order granting partial stay of dis

trict court decree, entered February 8, 1972, reported at

456 F.2d 6 and reprinted at A. 553-56.

13. Amended judgment of the Court of Appeals, en

tered August 14, 1972, reprinted at A. 603.

Other reported opinions in this case are as follows: 317

F.2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963); 345 F.2d 310 (4th Cir.), rev’d

382 U.S. 103 (1965); 324 F. Supp. 456 (E.D. Va. 1971).

Jurisdiction

The opinion of the Court of Appeals was entered June

5, 1972 and its amended judgment filed August 14, 1972.

On August 29, 1972, Mr. Justice Marshall extended the time

within which this Petition might be filed to and including

October 5, 1972. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

4

Question Presented

Is the constitutional power of a federal court to remedy

racial discrimination in the public schools confined within

the geographic boundary lines of a single State-created

school district in the absence of a showing of racial motiva

tion in the drawing of the district lines!

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

The case involves the Tenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States, which reads as follows:

The powers not delegated to the United States by the

Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are

reserved to the States respectively or to the people.

This matter also involves the application of the Equal Pro

tection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States, which provides as follows:

. . . nor shall any State . . . deny to any person within

its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Various provision of Virginia’s 1902 and 1971 Constitu

tions and statutes relating to education which are also rele

vant to this matter are set out in the separate Appendix

filed by the School Board of the City of Richmond (see n. 1

supra and accompanying text) at A. 604-23: Constitution of

1902, §§ 129, 130, 132, 133; Constitution of 1971, Art. VIII,

§§ 1-7; Va. Code Anno. §§ 22-1, -2, -7, -30, -34, -100.1 through

-100.12 (Repl. 1969); Va. Code Anno. §§ 22-1.1, -2, -7, -21.2,

-30, -32, -100.1, -100.3 through -100.11, -126.1, -127 (Supp.

1972).

5

Statement

A. B ackgrou n d o f the L itiga tion: School Segregation

and D esegregation in V irgin ia.

In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S.

1, 5-6 (1971), describing the cases before it from North

Carolina, Georgia and Alabama, Mr. Chief Justice Burger

wrote for the Court that “ [t]his case and those argued with

it arose in states having a long history of maintaining two

sets of schools in a single system deliberately operated to

carry out a governmental policy to separate pupils in schools

solely on the basis of race . . . ” This matter, too, arises

in a State which has, historically and continuously, spared

no resource and left unexplored no ingenious device in its

effort to maintain segregation in education.2 This history

is important not only because, as in Swann, it points to the

continuity of judicial effort since Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) to devise and implement adequate

remedial steps to redress the unconstitutional state policy,

but also because the Court below—under the rubric of the

Tenth Amendment—attributed to the Commonwealth of

Virginia a policy of individual school district sanctity (to

which the Court of Appeals said the federal remedial power

must defer) that examination of this history makes appar

ent does not exist and never has existed.

Virginia’s public schools were, at the outset, entirely

local in character and operation. The earliest education

statute of the Commonwealth (1797) merely authorized

county officials to construct and operate schools with reven-

2 This Court has decided as many cases involving public school

desegregation arising in Virginia as in any other state. A Virginia

case was one of those decided with Brown; and see Griffin v. County

School Bd., 377 U.S. 218 (1964) ; Bradley v. School Bd., 382 U.S.

103 (1965); Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968);

W right v. Council of the City of Emporia, 33 L.ed.2d 51 (1972).

6

ues from comity taxes. Not until 1869 did the Virginia Con

stitution and laws create “school districts” and require the

establishment of a State-wide public school system. See

Board of Supervisors v. County School Bd., 182 Va. 266,

268-69, 275, 28 S.E.2d 698, 699, 702 (1944). At the same

time, however, a policy of segregation in the public schools

was adopted and enforced on a State-wide basis.3 The ac

tions of Virginia officials, including state educational au

thorities, make manifest the hierarchy of values when the

two policies—localism and segregation—were in conflict.

For example, the State Board of Education4 did not avail

itself of its authority to consolidate6 separate school dis-

3 In 1954, the Virginia Attorney General told this Court that:

In general, education in Virginia has operated in the past pur

suant to a single plan centrally controlled with regard to the

segregation of the races. (Brief for Appellees in No. 3, Davis

v. County School Bd., O.T. 1954, at p. 15.)

4 The State Board of Education has the responsibility for the

general supervision of education throughout the Commonwealth.

Among its specific powers, it prescribes the qualifications for divi

sion superintendents, who are to be appointed by the local school

boards from a list of eligible persons certified by the State Board,

and who receive a salary not less than a minimum established by

State law and toward which the State contributes a fixed propor

tion. If a local board fails to appoint its Superintendent within a

specified time after a vacancy occurs, the State Board designates

that officer; the current Chesterfield Superintendent was so ap

pointed by State authorities. The State Board also prescribes rules

and regulations governing the operation of high schools, examines

and certifies teachers and selects textbooks. The ultimate central

authority for public education in Virginia has received judicial

recognition; in 1962 a federal district court held the public schools

within Prince Edward County were “primarily administered on a

statewide basis. A large percentage of the school operating funds

is received from the state. The curriculums, school textbooks, mini

mum teachers salaries, and many other school procedures are gov

erned by state law . . . . ” Allen v. County School Bd., 207 F.

Supp. 349, 354 (E.D. Va. 1962). See also, Griffin v. County School

Bd., supra.

6 This power was removed from the State Board of Education by

the 1971 General Assembly of Virginia, in the course of this law

suit. See pp. 32-33 infra, text at note 53.

7

tricts into single school divisions (which would at least

share the same Superintendent and might then merge their

operations6 under a single school board) despite avowed

State policy favoring consolidation;7 almost without excep

tion, the State Board joined only consenting districts at

their request. On the other hand, state authorities actively

endorsed and facilitated the establishment and operation of

joint schools for blacks which drew their students from

within several separate school districts and over distances

which sometimes required the black children to board at

the school during the week.8 With the express sanction of

6 The expectation of joint operation which flowed from being

named a single school division is well illustrated by the history of

W right v. Council of the City of Emporia, 33 L.ed.2d 51, 57, 59

(1972). There, after Emporia became a second-class city, politically

independent of Greensville County, the city and county w7ere desig

nated a single school division by the State Board of Education and

continued to operate their schools together until after entry of an

effective desegregation order. In 1969, when the city attempted to

operate its own school system, it also sought separate school division

status from the State Board even though this was not required

under State law.

7 In 1922 the General Assembly abolished the prior system of

separate school districts congruent with magisterial (county sub

unit) districts following the recommendation of the State Superin

tendent of Public Instruction that this be done in order to eliminate

“ [pjurely artificial differences” among the various districts. A n

nual Report of the State Superintendent, 1917-18, p. 14. (PX 124)

The State Board of Education has consistently supported consoli

dation into larger operating units. In 1969, the Board said:

The State Board, therefore, has favored in principle the con

solidation of school divisions with the view to creating admin

istrative units appropriate to modern educational needs. The

Board regrets the trend to the contrary, pursuant to which

some counties and newly formed cities have sought separate

divisional status based on political boundary lines which do

not necessarily conform to educational needs. (RSBX 82)

8 For example, $75,000 in state vocational funds was allocated to

assist in the establishment of the Carver High School for black stu

dents from Culpeper, Madison, Orange, Green and Rappahannock

Counties—a multi-county “school district” of over 1338 square

8

state authorities, county school systems before and after

Brown sent their black resident pupils to other school dis-

districts (including one in West Virginia) and paid tuition

for them.9 Indeed, the State Superintendent of Public In

struction advised local districts ten days after the Brown

decision to continue their existing method of operation in

each locality, apparently without regard to the decisions.

Immediately after the decision in Brown v. Board of

Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955), the General Assembly of Vir

ginia restructured control of education in the Common

wealth, subjecting all phases of school operation to central

ized control and direction in an effort to maintain pupil

miles. Detailed regulations for the operation of such facilities were

adopted by the State Board of Education in 1946. The State De

partment of Education assisted in developing transportation sys

tems for these schools and otherwise facilitated their segregated

functioning. In the district court’s detailed findings of fact (A°352-

56; 338 F. Supp., at 155-57), evidence concerning half a dozen

such “joint schools” is summarized: Pulaski-Radford-Montgomery,

Christiansburg Institute, Manassas (Prince William, Fairfax, Fau

quier),^ Charlottesville-Albemarle, Lancaster-Northumberland, and

Rockbridge-Lexington. Some of these schools did not close as seg

regated institutions until 1966, 1967 and 1968, respectively.

9 Voluminous data concerning the shuffling of black students from

one school system to another is summarized in the district court’s

detailed findings of fact (at A. 360-64; 338 F. Supp., at 159-61).

Some examples follow:

Federick County black students attended high school in the

separate Winchester city system.

Until 1964-65, black Dixon County students attended high

school in Russell County.

From 1955 until 1965 black pupils of Bland County were edu

cated in Tazewell County schools.

From 1945 to 1965 Bath County blacks attended Alleghany

County schools.

Between 1941 and 1971, Chesterfield County sent 6,806 pupils to

Richmond or Petersburg schools, in addition to any transfers under

the tuition grant programs; between 1960 and 1971, a total of 14,522

Richmond students similarly attended other public systems (mostly

as a result of annexations).

9

segregation. (See Virginia’s interposition resolution, Va.

Acts 1956, S.J.R. 3, p. 1213, 1 Race Eel. L. Rep. 445). In

1956 the Governor was authorized to close any school which

was integrated, Va. Acts 1956, Ex. Sess., ch. 68, p. 69, 1

Race Rel. L. Rep. 1103.10 At the same time, the State Pupil

Placement Board was established as an independent state

body with plenary power over the assignment of all school-

children in the Commonwealth ;n it continued in existence

until 1968.12 The State Department of Education dissemi

nated information concerning Pupil Placement Board pro

cedures to local school officials, and its employees also

served the Board. These and other devices effectively pre

vented any local school districts from voluntarily under

taking desegregation in accordance with Brown, and re

stricted the elimination of segregation to those school dis

tricts involved in federal court litigation where compliance

10 In 1958 the Governor ordered the State Police to close six

schools in Norfolk to prevent the admission of 17 black students.

The statutes were declared to be in conflict with the Virginia Con

stitution in Harrison v. Day, 200 Va. 439, 106 S.E.2d 636 (1959).

(Thereupon, local boards were authorized to close schools to which

any federal or state troops, military or civil, were sent. Va. Code

Ann. §22-188.51 (Repl. 1969)). A reading of Harrison v. Day

together with School Bd. of Prince Edward County v. Griffin, 204

Va. 650, 133 S.E.2d 565 (1963) makes clear that the defect under

the state constitution was not the exercise of State power to keep

local schools segregated, but only the State’s assumption of an ulti

mate power to discontinue local schooling entirely. Compare James

v. Almond, 170 P. Supp. 331 (E.D. Va.), appeal dismissed, 359 U.S.

1006 (1959).

11 A December 29, 1956 telegram from the Pupil Placement Board

to then Chesterfield County Superintendent of Schools Fred D.

Thompson began: “Under the provisions of Chapter 70, Acts of

Assembly, extra session of 1956, effective December 29, 1956, the

power of enrollment or placement of pupils in all public schools of

Virginia is vested in the Pupil Placement Board. The local school

hoard, Division Superintendents, are divested of all such powers”

(emphasis supplied) (Tr. F-105-06; PX 122).

12 Evidence introduced at the trial of this case indicated the

recognition of State authorities that the Pupil Placement Board

was merely a device to prevent school integration (PX 144-F).

10

with state procedures had been enjoined or declared un

constitutional. See, G.g., Adkins v. School Bd. of Newport

News, 148 F. Supp. 430 (E.D. Va.), aff’d 246 F.2d 325 (4th

Cir.), cert, denied, 355 U.S. 855 (1957).

When the devices of extreme centralization represented

by the school closing and pupil assignment laws failed to

prevent desegregation, Virginia accepted the inevitability

of some integrated education but did all within its means

to minimize the amount. A combination of centralist and

localist policies was designed, fluctuating from time to time

in whatever manner seemed to promise the most successful

avoidance of Brown. Thus, althoug'h pupil assignment

powers were returned in 1961 to local boards, criteria es

sentially identical to those of the Pupil Placement Board

(which dealt explicitly with race) were promulgated by the

State Board of Education. At the same time, the resources

of the State were made available to school districts for the

purpose of perpetuating segregation: they received assis

tance in designing transportation systems to serve segre

gated schools,13 legal aid in resisting desegregation litiga

tion, and loans and grants of State funds to construct and

operate additional segregated schools either within existing

districts or as joint facilities for black students in several

districts. State officials continued to urge defiance of this

Court’s mandates and set the pattern by their own activ

ities, as when the Department of Education continued segre

gated meetings of state-wide educational personnel until

1965.14

At the local level, the new tolerance allowed local school

boards—coming only two years after the State had closed

13 In 1963, the State Department of Education drew segregated

bus routes—some as long as 20 miles each way—at the request of

Henrico officials.

14 A. 265; 338 F. Supp. at 116; PX 122; RSBX 83.

11

tlie schools rather than allow them to open on an inte

grated basis—was demonstrated in Prince Edward County.

When Prince Edward elected to end its public school

system rather than desegregate, Virginia’s constitution

was interpreted by the State courts to allow such closure

notwithstanding a constitutional provision requiring the

establishment of a system of free public schools. See

County School Bd. v. Griffin, supra; Griffin v. County

School Bd., supra.

State authorities continued to function in support of

segregation, however. In Prince Edward, they softened

the blow by distributing tuition grants, at least to white

students, thereby enabling pupils to attend either private

schools or public schools in other divisions untainted by

desegregation. The tuition grant lawT that made this pos

sible was originally adopted by the 1956 legislature which

passed the school closing laws; in 1958 the State Board

of Education issued regulations to implement the statute

which provided reimbursement for tuition paid in order

to attend another school division if the pupil were as

signed to an integrated school or one which had been

closed by order of the Governor. The State Department

of Education reimbursed localities for the State’s share of

the grant.16 The program was expanded in 1960 (when

the statute was amended) to include payments to private

schools.

The tuition grant system represents an admixture of

central state support and decentralized decision-making

16 Until its termination in 1970, see Griffin v. State Bd. of Educ.,

296 F. Supp. 1178 (B.D. Va. 1969) (three-judge court), state and

local agencies expended almost $25 million under the program, in

cluding retroactive grants to Prince Edward County parents. Be

tween 1954 and 1971, $1,697,329.46 in State and local monies were

expended in tuition grants for pupils of the greater Richmond

area. Of this amount, $894,734.70 was spent between 1965 and 1971

alone.

12

calculated to preserve segregation. It superseded “lo

calism” pro tanto, for the law effectively made it im

possible for a given locality to refuse to participate in

the program. In the event of non-cooperation by the local

authorities, grants would be made directly to parents;

and the State withheld an equivalent local share of the

State aid funds.16 Now individual parents were given

ultimate control over pupil assignments through the tui

tion grants.

This massive and continuing exertion of state powers

to preserve segregation meant that the only way in which

desegregation could be made effective was by judicial de

cree. The difficulty of bringing individual lawsuits against

every school system, and the currency, prior to 1963, of

judicial doctrine17 that impeded enforcement of Brown,

both substantively and procedurally, resulted in turn in

little progress through the courts. Throughout Virginia,

compliance with Brown remained token or worse.18 This

16_ Evidence demonstrating the extensive state-wide use of the

tuition grant programs to perpetuate segregation is summarized in

the district court’s detailed findings of fact. A. 320-31- 338 F

Supp., at 141-46.

. Exhaustion of administrative remedies unless unquestionably

futile was required, e.g., Carson v. Warlick, 238 F.2d 724 (4th Cir

1956), cert, denied, 353 U.S. 910 (1957); Adkins v. School Bd. of

Newport News{ supra; Jones v. School Bd. of Alexandria, 278 F.2d

72 (1960), until this Court’s decision in McNeese v. Board of Educ.,

373 U.S. 668 (1963). Similarly, class actions were not permitted

until after Green v. School Bd. of Roanoke, 304 F.2d 118 (4th Cir.

1962). Desegregation was still not widespread after elimination of

these problems, however, because ineffective pupil transfer and free

choice pkns received general approval. E.g., Bradley v. School Bd.

®45 F.2d 310 (4th Cir.), rev’d on other grounds. 382

U.S. 103 (1965).

18 See, e.g., U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, Civil R ights, U S A -

P ublic Schools, Southern States (1962); U.S. Comm’n on Civil

Rights, Survey of School Desegregation in the Southern and

B order States 1965-1966 (1966).

13

was clearly true of the Richmond area schools in the city

and Chesterfield and Henrico Counties.

Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

the Virginia State Department of Education signed a

compliance agreement with HEW in order to remain elig

ible for federal education funds. Again there was a shift

in Virginia’s view of the appropriate respective role of

state and local authorities: the State Department of Ed

ucation now claimed to be without power to police the

compliance of local districts with federal law regarding

student and faculty assignments. This new-found lack of

power did not prevent the Department from encouraging

resistance by local districts to HEW efforts, however.19

Despite the State’s role as a major source of funds for

public education, the Department considered neither the

Fourteenth Amendment nor its own compliance agreement

as requiring it to withhold state funds or take any other

steps against districts operating in violation of the Con

stitution.20 As the district court has aptly described it:

In the years since [Brown], the powers of the State

Board of Education and the State Superintendent of

19 Although special counsel advised the State Department of Edu

cation as early as November, 1965 that free choice plans were prob

ably never going to work satisfactorily and would likely be rejected

by HEW and the courts in the near future, the State continued to

assist in the defense of free choice and provided no leadership to

local school systems faced with the task of desegregating.

20 Gf. Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 267 F. Supp. 458, aff’d

sub nom. Wallace v. United States, 389 U.S. 215 (1967); United

States v. Georgia, Civ. No. 12972 (N.D. Ga., Dee. 17, 1969), rev’d

on other grounds, 428 F.2d 377 (5th Cir. 1970) ; United States v.

Texas, 321 F. Supp. 1043 (E.D. Tex. 1970), supplemental order

of April 19, 1971 (unreported), modified and aff’d 447 F.2d 441

(5th Cir.), stay denied, 404 U.S. 1206 (1971) (Mr. Justice Black,

Circuit Justice), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 1016 (1972).

14

Public Instruction have varied but slightly; what

changes in law have been made have principally been

to expand its powers. Other State educational agencies

have come into existence and disappeared in interven

ing years as well. For the major part of this seven

teen year period the State’s primary and subordinate

agencies with authority over educational matters have

devoted themselves to the perpetuation of the policy

of racial separation. They have been assisted in this

effort by new legislation creating such programs as

the tuition grant and pupil scholarship systems, the

pupil placement procedures, and, by enactment passed

while this case was pending, placing new limitations

on the power of the State Board to modify school

division boundaries. They have employed established

techniques and powers as well to perpetuate segrega

tion.

Only very tardily and under the threat of financial

coercion has the State Board of Education implicated

itself in any respect in the desegregation process. In

so doing it has conceived of its affirmative duty very

narrowly, confining its efforts to those required by its

compliance agreement with the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare, and on occasion not even ad

hering to that.

A. 215; 338 F. Supp., at 93. The desegregation of Vir

ginia public schools thus has rested upon the individual

efforts of private litigants and the federal compliance

effort unassisted by State cooperation. As a result, there

was virtually no real desegregation in the State prior to

Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968). Most

desegregation started no earlier than the 1969-70 or 1970-71

school years; the Motion for Further Relief which ulti-

15

mately led to the order here involved was filed March 10,

1970.

B. The Greater Richm ond Community.

The order of the district court, reversed by the judg

ment of which review is soug-ht, was intended to effectuate

the desegregation of the public schools in the Richmond,

Virginia area—and encompassing that city as well as the

counties of Henrico and Chesterfield.21 Richmond, ap

proximately sixty-three square miles in area, lies nearly

at the geographical center of the region and occupies an

area both north and south of the James River. Henrico

County (244 square miles) entirely surrounds the city

at all points north of the James, and Chesterfield County

(445 square miles) is likewise completely contiguous with

and envelops Richmond south of the James. Other counties

to the north and south of Henrico and Chesterfield, re

spectively, are separated from this Richmond metropolitan

area in whole or in part by the Appomattox and Chick-

ahominy Rivers. Virtually all of Henrico and most of

Chesterfield County22 lie within thirty minutes’ travel of

Capitol Square in Richmond, using regular streets and

averaging twenty to forty miles per hour.

The two counties and Richmond are highly interrelated

and mutually dependent upon one another. Typical of

most urban areas, the central core city has ceased to reg

ister increases in population in the decennial censuses;

21 The entire area was a part of Henrico County originally;

Richmond and Chesterfield County, among other political entities,

were created from it. Subsequently the city annexed various por

tions of each county from time to time. The last such annexation,

from Chesterfield County, occurred in 1970.

22 This includes all of the areas which, under the plan approved

by the district court, would send students at any grade level to a

school or schools presently located within the city boundaries.

16

the additional population growth from 1950 to 1960 oc

curred in Henrico and in 1960 to 1970 in Chesterfield

County; the most densely populated areas of each county

are contiguous to Richmond. The 1970 Census reveals

a total population of 480,840 in the area: 249,430 in Rich

mond, 154,364 in Henrico County and 77,046 in Chester

field County.23

A variety of historical, economic and social indicators

demonstrate the close functional unity of the area despite

its superstructure of three independent political subdi

visions. For example, evidence introduced at the trial

indicated that prior to the 1970 annexation, over three-

quarters of the jobs in the region (78% of those covered

by Virginia’s unemployment compensation program) were

in Richmond, and analyses performed for the Richmond

Regional Transportation study projected that the city

would retain a similar proportion of metropolitan employ

ment in the future (Tr. A-38, 43; R8BX 54, 55).24 Sim

ilarly, pre-annexation Richmond accounted for 62% of

the region’s retail sales and 76% of the value added by

manufacturing (Tr. A-42, 43).25 The daily newspapers of

general circulation throughout the area26 are in Richmond,

as are most local television and radio stations and a

disproportionate number of public and private educational

23 See table at p. 58 infra.

24 The 1970 Census data which has become available since the

trial bears out the projections. See pp. 71-74 infra. Evidence

introduced at the trial showed that 42% of the attorneys who prac

ticed in Richmond lived in the counties (51.4% reside in the city

and 6.6% elsewhere), while approximately one-third of the State

Education Department employees live in each of the three juris

dictions.

2B Figures presently available show an increase in such indices.

See text at note 139 infra.

26 Tr. K-85; cf. note 45 infra.

17

and cultural facilities; for example, six of seven insti

tutions of higher learning, including a medical college

(Tr. A-45, M-12) and the major libraries and museums

in the area (Tr. A-46; RSBX 59). Health services for the

entire area are concentrated in Richmond (which includes

within its boundaries 17 of the community’s 18 hospitals),

and most residents of the region are born in and die

within Richmond.27 Such public transportation as is avail

able in each of the counties is almost exclusively directed

toward travel between suburb and city rather than within

each county.28

Although the region is divided among three political

jurisdictions, among which there is a quite natural com

petitive spirit in various affairs, there have been numerous

common actions for mutual benefit. Henrico County relies

upon the fire and police services of Richmond at its county

offices, which are located within the city; other parts of

the county have in the past received fire protection from

Richmond pursuant to agreement. There is presently a

reciprocal fire assistance pact between Richmond and

Chesterfield County (Tr. L-227). Pursuant to statute, the

city and counties share concurrent regulatory jurisdiction

over subdivision development in an area five miles around

Richmond. The city has entered into 20-year sewage treat

ment and water supply contracts with Henrico County,

which receives 90% of its water from Richmond (Tr. A-117,

120), as well as reciprocal supply agreements for these

utilities with Chesterfield County (Tr. A-122-23).

27 Data compiled by the Richmond Planning Department from

Bureau of Vital Statistics records showed that 70% of resident

Chesterfield mothers, 79% of Henrico mothers and 94% of Rich

mond mothers gave birth within the city, while 49% of Chesterfield

residents, 55% of Henrico inhabitants and 85% of all Richmonders

died in the city (Tr. A-46; RSBX 61).

28 For example, the only public transportation in Chesterfield

County is two bus routes from Richmond (Tr. M-16,17) (c/. PX 1).

18

Reports of the regional planning commission as well

as those of independent consultants (some commissioned

by county officials) have all noted the marked interdepen

dence of the city and counties. The district court reviews

those and much of the evidence introduced at the trial in

its detailed findings (A. 401-16; 338 F. Supp., at 178-84) ;29

an appropriate summation is the following comment of

the Henrico County Circuit Court in a 1964 Richmond

annexation suit:30

Although community of interests is not necessarily

as vital a consideration as other factors to be con

sidered . . . this Court nevertheless feels that this

factor should be given consideration. . . . Dependence

of the central city of Richmond and the immediately

surrounding county is mutual, [record citations omit

ted] The evidence shows that the commercial and civic

interests of the city and county are largely identical.

!• Schools in the Community.

Each of the three school systems in the Richmond area

was strictly segregated at the time of the Broivn decision,

in accordance with Virginia law, and remained so under

29 We add, among the other factors which we do not detail for

the sake of brevity, that Richmond and the two counties form a

single Congressional district and that they, along with Hanover

County (added by the Census Bureau in 1963 but with somewhat

more diffused indices of interrelationship), make up the Richmond

Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area. See note 92 infra, and

accompanying text.

30 Under Virginia law, cities commence annexation proceedings

by passage of an ordinance and filing of suit to annex a specified

amount of contiguous territory. A special court is designated

which, after hearing, determines whether the prerequisites for an

nexation are met and then fixes a compensation award. The city

may then accept or reject the terms. In 1964, Richmond declined

to accept the terms fixed by the Court in its annexation suit against

Henrico County and no territory was gained.

19

the Pupil Placement Board regime.31 In 1961, this suit

was commenced against the original defendants (the School

Board of the City of Richmond and the state Pupil Place

ment Board) and the district court issued a decree di

recting the board and the Pupil Placement authorities to

admit the individual named pupil plaintiffs to the formerly

white schools they wished to attend.32 Similar relief was

obtained in Chesterfield County after suit was filed in

1962,33 but until 1965 there was little more than token

desegregation in any of the schools of the region. About

that year, freedom of choice plans were adopted in each

system—as the result of further judicial proceedings in

the Richmond litigation, and following HEW compliance

efforts in the two counties.34 Again, the free choice plans

produced little more than token integration (See Appen

dices to the district court’s opinion, A. 524-32; 338 P.

Supp., at 234-42.) In 1968-69 all of the traditionally black

schools in the three jurisdictions remained all black.

Following threatened termination of federal financial

assistance, Chesterfield County closed all formerly black

facilities by the 1970-71 school year (its black student

population was then less than 10%, down from 20% in

31 While the tuition grant and pupil scholarship programs ex

isted, they were utilized by students in the Richmond area to avoid

integration. From 1965 to 1971 alone, grants totalled $462,000 in

Chesterfield, $286,000 in Henrico, and $97,000 in Richmond. The

three divisions have expended nearly $1.7 million for tuition grants

since Brown. See n. 15 supra.

32 rpjjg p our.̂ }j Circuit reversed and directed the entry of a decree

on behalf of the class of plaintiffs. 317 F.2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963).

33 McLeod v. County School Bd. of Chesterfield County, Civ. No.

3431 (E.D. Va.).

34 The McLeod case lay dormant from 1962 to 1971 and the De

partment of HEW undertook Title VI enforcement. A motion to

consolidate this case with McLeod at the beginning of the trial was

denied as untimely by the district court.

20

1954) except for the Matoaca Laboratory school, although

significant faculty segregation remained. Similarly, in the

1969-70 school year, and under HEW pressure, Henrico

County closed its formerly black facilities (although many

were subsequently reopened as “annexes” to formerly white

schools); however, zone line alterations resulted in one

elementary school becoming over 90% black, and enrolling

40% of the county’s black elementary students. It was

also during the 1969-70 school year that the Motion for

Further Relief was filed in the Richmond case, leading to

the elimination of the free choice plan in the city.

Like the political bodies, Richmond’s school authorities

have worked together to meet the educational needs of the

region. A modern vocational-technical training facility

is operated by the Richmond system, enrolling a propor

tionate number of students from the three subdivisions.

Together, several specialized joint schools are operated:

two centers for mentally retarded children (one located

in Henrico and another in that area of Chesterfield County

annexed to Richmond in 1970), and a mathematics-science

center in Henrico.36 When annexations have resulted in

capacity problems for one of the school districts, students

have been educated in one of the other systems by con

tractual agreement until permanent facilities could be con

structed (as was the case after 1970, when 3387 Richmond

students continued to attend Chesterfield County schools).

One Richmond high school is entirely within Henrico

County, and one Richmond elementary school partly in

the same county.

. 35 Classes at the center are integrated and approximate the re

gion’s overall student population ratio.

21

2. Changing Internal D em ography.

The Greater Richmond community experienced its most

sustained and substantial growth in the period from just

before Brown y. Board of Educ., supra, to the present. Al

though prior to 1940, most of the population growth with

in the region was in the City of Richmond, over 90% of

the increase in population since that year has occurred

in Henrico and Chesterfield counties. Henrico made its

major gains from 1950 to 1960, and Chesterfied in the 1960-

70 decade.

The population changes are, of course, reflected in the

changing enrollments of the region’s schools. Enrollment

in the Richmond system grew from 35,857 in 1954-55 to

47,604 in 1970-71 (including the pupils gained by the 1970

annexation from Chesterfield County), while Henrico gained

21,328 during the period for a 1970-71 total enrollment

of 34,470 and Chesterfield added 14,931 pupils for a 1970-

71 enrollment of 24,063 (reflecting also the pupils lost by

the 1970 annexation).

The increasing suburbanization during the period is

demonstrated by annexation of portions of Henrico and

Chesterfield Counties in 1942 (and an attempted Henrico

annexation in 1963) as well as the 1970 Chesterfield annexa

tion. Furthermore, most of the population change in the

metropolitan region is accounted for by newcomers rather

than natural increase. During the 1950-1960 decade, for

example, one-half of Chesterfield’s, and three-quarters of

Henrico’s population growth resulted from in-migration.

From 1960-70 over half of Henrico’s increase resulted

from in-migration.36 In the same period, Richmond lost

some 33,000 residents.

36 Similar information for Chesterfield County is unavailable

since census figures are not separately set out for the area of the

county annexed to Richmond in 1970. See United States Dep’t of

22

The outstanding characteristic of this population change,

however, has been its racially differential impact. Al

though the overall composition of the region has re

mained remarkably stable throughout its recent develop

ment (in 1940 the black population was 28%; in 1970 it

was 26%), the distribution of whites and blacks through

out the area has not. The Richmond suburbs have been

virtually restricted to whites. Even with the annexation

of a predominantly white portion of Chesterfield County

in 1970,37 in that year the proportion of blacks to total

Richmond population was slightly higher, at 42.3%, than

it had been in 1960; Chesterfield and Henrico were 11.5%

and 6.8% black, respectively.38 Richmond accounted for

only 25% of the white population gain in the SMSA39

during the preceding decade, while Henrico and Chester

field Counties received 60%40 of that increase. On the

Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Census of P opulation : 1970

(G.P.O. PCH(2)-48, 1971). The preliminary, unedited version of

this document (the final figures were not available at the time of

trial) was introduced at the trial by Chesterfield County.

37 The annexation added some 47,000 residents to the city; with

out it, instead of gaining nearly 30,000 people from 1960 to 1970,

Richmond would have lost over 17,000. See id. at p. 5.

38 In the preceding decade, Richmond lost total population but

changed from 32% black to 42% black. Henrico more than doubled

in size but dropped from 10% to 5% black, and Chesterfield grew

by 75% but dropped from 21% black to 13% black. See table at p.

58 infra.

■j9 In 1963 the Bureau of the Census added Hanover County to

its definition of the Richmond Standard Metropolitan Statistical

Area, which already had included Chesterfield, Henrico and Rich

mond. Hanover, which contains 7% of the SMSA population, ac

counted for 15% of its white population growth from 1960-1970

Its school system, 24% black in 1970, was the subject of separate

litigation, see Thompson v. County School JBd. of Hanover County

252 P. Supp. 546 (E.D. Va. 1966), and pursuant to an order

entered by the same district judge who presided below, its schools

were fully desegregated effective September, 1969.

40 Richmond contains 48% of the total population in the SMSA.

23

other hand, Richmond received 75% of the SMS A increase

in black population during the decade.

Although at the time of Brown, Richmond’s student

population was 43.5% black and the counties’ 20.4% and

10.4% black, respectively, by 1971-72 each county enrolled

less than 10% black students while the Richmond system

was over 70% black.41

The effect of these rapid changes, coming at a time when

State and local authorities were steadfastly avoiding their

legal obligation to eliminate dual systems of racially identi

fiable schools, was very significant. Particularly against

the background of Virginia history,42 any marked contrast

between the racial composition of schools among the sep

arate divisions made the elimination of racially identifiable

schools more difficult due to the ingrained Virginia practice

of making racial differentiations. Indeed, both Richmond

educators and those from without the Commonwealth testi

fied at the trial that the Richmond school system itself had

become identifiable by race so that, realistically, identifiable

41 This distribution differs markedly from that in the counties

surrounding. At the southern extremity of Chesterfield are three

small “independent” city school systems—Petersburg, Colonial

Heights and Hopewell, which are 67%, 0% and 18% black, respec

tively. The school systems of the counties surrounding the region

enroll the following proportions of black students:

Hanover ..... 24%

Charles City ............................... 84%

New K en t............................ 56%

Prince George ............................ 26%

Dinwiddie...................... 52%

Amelia ........................... 64%

Powhatan ..................................... 40%

Goochland..................................... 57%

Bach of these counties is far more sparsely settled than Henrico

or Chesterfield.

42 A. 187, 189; 338 F. Supp., at 80, 81. Cf. N.A.A.C.P. v. Patty,

159 F. Supp. 503 (E.D. Va. 1958), rev’d on other grounds sub nom.

Harrison v. N.A.A.C.P., 360 U.S. 167 (1959).

24

schools would remain even were Richmond schools racially

balanced, and the district court so found. (A. 201; 338 F.

Supp., at 87; see also A. 186, 197, 445; 338 F. Supp., at 80,

85, 197.)43 The Henrico County Superintendent of Schools

testified that when Central Cardens Elementary School was

finally desegregated in 1971-72, it was clustered with several

other schools rather than being simply paired with the near

est predominantly white school, because in the latter in

stance, its racial composition (62% black) in the context

of the county’s overall ratio (8%) would leave it racially

identifiable. (A. 395-96; 338 F. Supp., at 175.)

These perceptions of racial identifiability are substan

tially reinforced44 by virtue of the contribution made by

discriminatory governmental policies46 toward the sort of

48 Other witnesses offered conflicting opinions; the detailed find

ings of the district court thoroughly discuss the expert testimony

and contain the rationale for the court’s resolution of the testi

monial conflicts (A. 446-78; 338 F. Supp., at 198-212; see also A.

263; 338 F. Supp, at 115-16).

44 A. 189-90; 338 F. Supp, at 81. Cf. Brown v. Board of Educ.,

347 U .S, at 494:

Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has

a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is

greater when it has the sanction of the law ; . . . .

46 Virginia’s policy of segregation has run the gamut from ex

plicit ordinances, City of Richmond v. Beans, 281 U.S. 704 (1930),

through enforceable racially restrictive covenants (which were ex

tensively used in the Richmond area and which were not removed

from title insurance policies until 1969 (A. 515; 338 F. Supp at

228; Tr. E - l l; Tr. R-143-44; 6/22/70 Tr. 828-40; PX 90) to dis

criminatory location of public housing projects (A. 494-97; 338 F.

Supp, at 219-20). Likewise, the record reveals considerable private

discrimination, doubtless encouraged by the State’s official sanc

tion : for example, the Richmond daily newspapers serving the area

continued racially separate real estate listings until 1971, when the

practice was discontinued in response to threatened litigation by

the United States Department of Justice (A. 514-15; 338 F. Supp,

at 228; PX 42A-42C). The record also traces in some detail the

continuing effects, which have been noted by the President of

the United States (A. 516; 338 F. Supp, at 229; PX 126) of the

25

racial isolation which has occurred in Richmond.46 Of sig

nificance especially is the effect of the massive post-Brown

programs to construct segregated schools in the metropoli

tan area:

People gravitate toward school facilities, just as schools

are located in response to the needs of people.

Swann, 402 U.S., at 20.47

pervasive discriminatory practices of federal agencies such as FHA,

which have by their financing activities greatly facilitated the

process of metropolitan development. The district court further

found that to the extent that housing patterns are viewed as the

result of economic differentials, see note 46 infra, the differences

between whites and blacks were attributable in part to the inferior

segregated education offered by the Commonwealth of Virginia to

those blacks who are now renting or purchasing homes and raising

families. Cf. Griggs v. Duke Power Go., 401 U.S. 424, 430 (1971);

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969). The historic

inequality of black schools in Virginia—lower teacher salaries,

smaller instructional expenditures, higher pupil-teacher ratios, in

ferior supplemental services (including libraries), and fewer ac

credited schools—was fully documented before the district court as

confirmed by the Annual Reports of the Virginia Superintendent

of Public Instruction.

46 There was agreement among the expert witnesses that the racial

demography of the Richmond metropolitan area was not unlike that

found in other metropolitan centers across the nation. Dr. Karl

Taeuber testified, based upon his own exhaustive researches on the

subject, see K. Taeuber and A. Taeuber, Negroes in Cities (1965),

as well as his examination of the available data for Richmond and

the two counties, that the disparate racial pattern of residence could

not be attributed to either economic influences or the exercise of

preference alone, but that the effects of racial discrimination were

a major determinant.

47 School construction throughout the region played a material

part in residential development in at least three ways. First, in

Richmond, as established black neighborhoods expanded and ap

proached white schools (prior to the start of desegregation), the

school authorities redesignated these schools for black pupils, with

the result of solidifying the concentration of blacks and limiting

their residential movement to areas peripheral to established black

neighborhoods. Second, the counties’ practice of building only

26

C. The L itiga tion B elow .

1. P rior Proceedings.

This class action to desegregate the public schools of

Eichmond, Virginia was commenced in 1961 with the filing

of a complaint charging officials of the Commonwealth of

Virginia (the Eichmond School Board and the Pupil Place

ment Board of the Commonwealth) with racial discrimina

tion against black children. The initial district court order

directed that the individual named plaintiffs be admitted

to the white schools to which they desired to transfer but

denied an injunction in favor of the class. The Court of

Appeals reversed in part, directing limited class relief.

317 F.2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963). After further proceedings in

the district court, the Court of Appeals rejected plaintiffs’

challenge to free transfer desegregation plans and held also

that faculty desegregation would not be required. 345 F.2d

310 (4th Cir. 1965). This Court granted certiorari on the

issue of faculty desegregation, reversed, and directed that

the process of faculty desegregation be commenced. 382

TJ.S. 103 (1965).

IJpon remand from this Court, a consent decree was

entered which embodied a freedom-of-choice plan, provided

for faculty desegregation, and obligated school authorities

to replace free choice if it failed to produce results. How

ever, despite continuation of the patterns of segregation,

white schools (during the same period) in their most urbanized

areas contiguous to Richmond established a disincentive for blacks

to relocate in the suburbs: black children were transported, for

example, to Virginia Randolph High School in the northern part