St. Helena Parish School Board v Hall Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1961

80 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. St. Helena Parish School Board v Hall Jurisdictional Statement, 1961. 4e0e8473-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9e564dd1-9c1d-4993-8950-8f22f3c2533a/st-helena-parish-school-board-v-hall-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

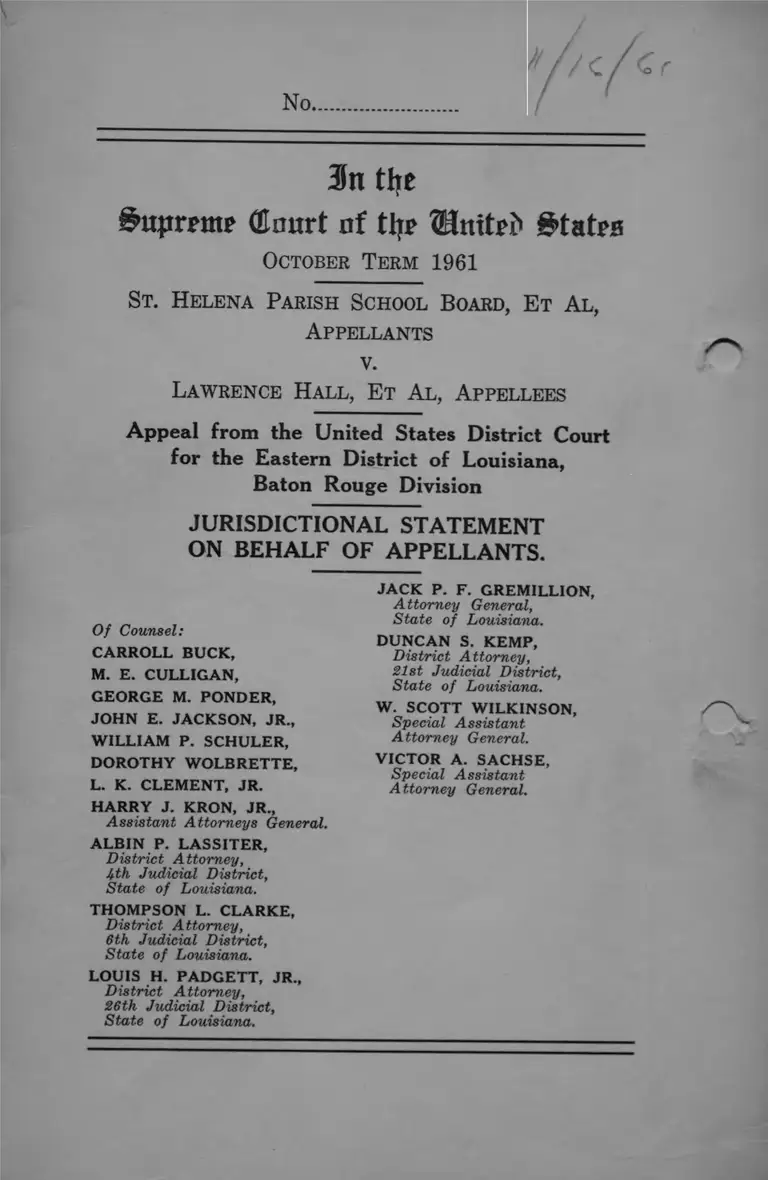

No.

3n tlje

(Emtrt of tljp UniteD §tatpH

October Term 1961

St. Helena Parish School Board, Et Al,

A ppellants

v.

Lawrence Hall, Et Al, A ppellees

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana,

Baton Rouge Division

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

ON BEHALF OF APPELLANTS.

Of Counsel:

CARRO LL BUCK,

M. E. CULLIGAN,

GEORGE M. PONDER,

JOHN E. JACKSON, JR.,

W ILLIA M P. SCHULER,

DOROTH Y W O LBRETTE,

L. K. CLEM ENT, JR.

H A R R Y J. KRON, JR.,

Assistant Attorneys General.

ALB IN P. LASSITER,

District Attorney,

Uth Judicial District,

State of Louisiana.

THOM PSON L. CLARKE,

District Attorney,

6th Judicial District,

State of Louisiana.

LOUIS H. PAD G ETT, JR.,

District Attorney,

26th Judicial District,

State of Louisiana.

JACK P. F. GREM ILLION,

Attorney General,

State of Louisiana.

DUNCAN S. KEMP,

District Attorney,

21st Judicial District,

State of Louisiana.

W . SCOTT W ILKINSON,

Special Assistant

Attorney General.

VICTOR A . SACHSE,

Special Assistant

Attorney General.

1

SUBJECT INDEX

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION................ 1

OPINION BELOW ................................................... 2

JURISDICTION ......................................................... 2

STATUTES INVOLVED ......................................... 2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ............... 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .............................. 4

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED ARE

SUBSTANTIAL ................................................. 9

CONCLUSION ............................................................ 29

PROOF OF SERVICE ............................................. 30

APPENDIX “ A ” ............................. 31

APPENDIX “ B” .......................................................... 61

APPENDIX “ C” ......................................................... 70

Authorities Cited:

A

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F. 2d 97................................... 12

Aerated Products Co. of Philadelphia, Pa. v. Dept,

of Health of New Jersey, et al, 159 Fed. 2d

851 ......................................................................... 10

Ash wander v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 297

U.S. 288, (concurring opinion)...................... 27

Avery v. Wichita Falls Independent School Dis

trict, 241 Fed. 2d 230, cert, denied, 353 U.S.

938 ......................................................................... 22

Page

IV

Plughes v. Caddo Parish School Bd., et al, 57 F.

Page

Supp. 508, affirmed 323 U.S., 685................ 17

I

In re School Code of 1919, 7 Boyce 406, 108 Atl.

39 ............................................................................ 20

J

James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331............13 & 17

James v. Duckworth, 170 F. Supp. 342.................. 17

Jeffrey Mfg. Co. v. Blagg, 235 U.S. 571.............. 27

K

Kee v. Parks, 153 Tenn. 306, 283 S.W. 751............ 20

Kelley v. Bd. of Ed. of Nashville, 270 F. 2d 209

(C.A. 6th, 1959) cert, denied, 361 U.S. 924.. 22

L

Larson v. Domestic & Foreign Corp., 337 U.S.

682 ......................................................................... 10

Liverpool, N. Y. & Phila. S.S. Co. v. Comm, of Im

migration, 113 U.S. 33................................ ...... 26

Lloyd v. Dollison, 194 U.S. 445.............................. 19

M

Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137, 2 L. Ed. 60.. 25

Montgomery v. Gilmore, 277 Fed. 2d 364 (C.A.

5th 1960) ................................................... 17 & 23

N

New Haven Public Schools v. General Services Ad

ministration, 214 Fed. 2d 592........................ 11

V

Page

Noah, et al, v. Bd. of Ed., District of Columbia,

106 F. Supp. 988................ ............................... . 10

North Dakota-Montana Wheat Growers’ Associ

ation v. U.S., 66 Fed. 2d 573, cert, denied,

291 U.S. 672................................................... . l i

O

Ohio v. Dollison, 194 U.S. 445................................... 21

P

Parker v. Bd. of Ed. of Sumter County, 70 S.E.

2d 369 (Ga.) ......................................... ............ 10

People v. Cowen, 283 111. 308, 119 N.E. 335,

(1918) .............................. 20

People of State of New York, ex rel Hatch v.

Reardon 204 U.S. 152...... 26

Phelps v. Bd. of Ed., 300 U.S. 319.......................... 9

R

Rippey v. State of Texas, 193 U.S. 504......... ........ 19

Roberts & Schaefer Co. v. Emmerson, 271 U.S. 50 26

S

Salzburg v. State of Maryland, 346 U.S. 545......... 15

School Board of Charlottesville v. Allen, 240 F. 2d

59 (C.A. 4th, 1956) Cert, denied, 77 S. Ct.

667 .......................................................... 22

Smith v. Hefner, 68 S.E. 2d 783 (N.C.) .............. . 10

Snowden v. Hughes, 321 U.S. 1................................ 9

VI

State v. Baxter, 195 Wis. 437, 219 N.W. 858..... 21

State v. Briggs, 46 Utah 288, 146 Pac. 261..... ---- 21

State v. Lamont, 105 Kan. 134, 181 Pac. 617-------- 20

Stephan v. Louisiana Board of Education, 78 So.

2d 18 ..................................................................... 10

T

Thomason v. Works Progress Administration, 138

F. 2d 342 .................................... ................. 11

Thompson v. School Board of Arlington, 144 F.

Supp. 239 (D.C. Va. 1956)................-........ - 22

Tyler v. Judges of Court of Registration, 179 U.S.

405 ......................................................................... 27

U

United States v. Raines, 362 U.S. 17...................... 27

United States Department of Agriculture, et al,

v. Hunter, et al, 171 Fed. 2d 793..... ........— 10

United States Department of Agriculture v. Re-

mund, 330 U.S. 539..-....................................---- H

United States v. Wurzbach, 280 U.S. 396............. 26

V

Virginian Railway Co. v. System Fed., 300 U.S.

515 ...................................................................... 26

Voeller v. Neilston Wholesale Co., 311 U.S. 531. 26

Page

Y

Yazoo & Mississippi Valley Railway Co. v. Jack-

son Vinegar Co., 226 U.S. 217..... .................. 26

Constitutional Provisions

La. Const, of 1921, Art. 19, Sec. 26, Amend. 11,

U.S. Const............................................................... 10

La. Const, of 1921, Art. 12, Sec. 1................... 10

11th Amend., United States Constitution........ 10

14th Amend., United States Constitution............. 18

Statutes

28 USC 501............................................................. io

28 USC 507................................................................... 10

Bill H.R. 6128, 85th Congress (original), Pages

9 and 10.................................................................. 10

N.C. Private Laws, 1923, Ch. 37, Sec. 79........... 16

N.C. Sess. Laws, 1957, Ch. 960, Sec. 4................ 16

28 USC 1331.................................................................. 2

28 USC 1343.................................................................. 2

28 USC 2281.......................................................... 2 & 5

28 USC 2284.......................................................... 2 & 5

28 USC 2201................................................................. 2

28 USC 2202................................................................. 2

28 USC 1253................................................................. 2

Act 2, Second Extraordinary Session of the Loui

siana Legislature of 1961...... .....4 & 5 & 7 & 8

Act 258 of 1958............................................................ 6

Vll

Page

vm

Page

Miscellaneous

16 C.J.S. Const. Law, Sec. 142, Page 683.............. 20

16A C.J.S. Sec. 505, Page 314................ ................ 13

16A C.J.S., Sec. 6, 512, Page 358.................. .......... 19

Congressional Record of 1957, Pages 11377 and

11378 ................................................... ........... ...... 10

Harvard Law Review, Vol. 72, Page 1567.............. 16

Index, Digest of State Constitutions, Page 390..... 19

School Code of 1919, 7 Boyce 406, 108 Atl. 39..... 20

No.

Jtt tljr

(Enurt of ttje {Hmtrfo States

October Term 1961

St. Helena Parish School Board, Et A l,

A ppellants

v.

Lawrence Hall, Et A l, Appellees

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana,

Baton Rouge Division

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

ON BEHALF OF APPELLANTS.

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellants, St. Helena Parish School Board,

J. L. Meadows, Superintendent of the St. Helena

Parish School Board, State of Louisiana, Jack P. F.

Gremillion, Attorney General of Louisiana, Murphy

J. Roden, Director of Public Safety of Louisiana,

Duncan S. Kemp, District Attorney of St. Helena

Parish, Louisiana, and R. D. Bridges, Sheriff of

St. Helena Parish, State of Louisiana, appeal from the

judgment of the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Louisiana, Baton Rouge Divi

sion, sitting as a three-judge Court, entered on the

30th day of August, 1961, declaring unconstitutional

Act 2 of the Second Extraordinary Session of the Lou

2

isiana Legislature for 1961, and further enjoining

appellants, and their successors, agents, representa

tives, attorneys, and all other persons who are acting

or may act in concert with them, from enforcing or

seeking to enforce by any means, the provisions of

said statute. Appellants submit this statement to

show that the Supreme Court of the United States

has jurisdiction of the appeal and that substantial

questions are presented.

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana, Baton Rouge

Division, is not yet reported, however the judgment

of the Court and reasons therefor are attached hereto

as Appendix “A ” .

JURISDICTION

This proceeding was brought under:

28 USC 1331, 28 USC 1343, 28 USC 2281, 28

USC 2284, 28 USC 2201 and 28 USC 2202.

The judgment and reasons therefor were entered

on August 30, 1961, and Notice of Appeal was filed

on September 11, 1961.

The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court to review

this decision by direct appeal is conferred by 28 USC

1253.

STATUTES INVOLVED

The statute involved is Act 2 of the Second Ex

traordinary Session of the Louisiana Legislature of

3

1961. The aforesaid Act is set forth in full in Appen

dix “ B” hereof.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I.

Does the Court have jurisdiction over the subject

matter?

II.

Is this a suit against the State and thus one pro

hibited by the Eleventh Amendment of the United

States Constitution?

III.

Is not the United States participating herein

without authority in law and equity?

IV.

Is not Act 2 of the Second Extraordinary Session

of the Louisiana Legislature for 1961 constitutional

and valid?

V.

Has not the United States failed to state a claim

upon which relief can be granted?

VI.

Have the complainants herein not failed to join

indispensable parties?

VII.

Is not the relief sought by the complainants

herein premature?

4

Does not Act 2 of the Second Extraordinary Ses

sion of the Louisiana Legislature for 1961 meet all of

the requirements of the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Lawrence Hall and numerous other complainants

filed a complaint on September 4, 1952 against the St.

Helena Parish School Board and J. L. Meadows,

Superintendent of the St. Helena Parish School Board.

The cause originally instituted has been litigated

before the United States District Court for the East

ern District of Louisiana, the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and writs were refused

by this Court on October 9, 1961.

On March 17, 1961 the State of Louisiana was

made a defendant. See Appendix C.

A supplemental complaint under the same num

ber, title and style was filed by original plaintiffs on

March 30, 1961, which supplemental complaint

attacked the constitutionality of Act 2 of the Second

Extraordinary Session of the Louisiana Legislature

for 1961, and a three-judge Court was convened, pur

suant to the United States Code to adjudge the valid

ity of the said statute and entertain Motion for Pre

liminary Injunction enjoining appellants from im

plementing or giving any effect to the provisions of

the said Act.

VIII.

5

All appellants, with the exception of the St.

Helena Parish School Board and J. L. Meadows,

Superintendent of the St. Helena Parish School Board,

State of Louisiana, who were original defendants,

were joined as parties defendant by ex parte order of

Court.

Jurisdiction of the supplemental complaint was

invoked pursuant to 28 USC 2281 and 2284.

Hearing was held on the application for tempo

rary injunction on April 14, 1961, after which the

Court rendered the following per curiam:

“ The motions are overruled, in part because coun

sel for the plaintiffs has made it clear that the

plaintiffs do not seek to enjoin the holding of

the election fixed for April 22,1961, in the Parish

of St. Helena. The election has bearing in this

case only as the initial step, under Act No. 2 of

the Second Extraordinary Session of 1961, lead

ing to the closing of public schools in St. Helena.

If Act 2 is unconstitutional, the defendants prop

erly before the Court may be enjoined from

carrying out the provisions of the law.

We have an open mind on the constitutionality

of the statute. We point out, however, that na

tional policy and state policy require us to scruti

nize carefully any statute leading to the closing

of public schools. When there is now such a mani

fest correlation between education and national

survival, it is a sad and ill-timed hour to shut

the doors to public schools. And, now, when one

of the principal functions of the state is to main-

6

tain an educational system, it seems strange in

deed and anti-civilized to shift the major financial

burden to private persons, many of whom cannot

afford or can ill-afford to pay for private school

ing even with the benefit of a grant-in-aid. We

think that this case raises due process questions

that have not been briefed.

Does Act 2 violate the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment by depriving children of

the opportunity to obtain a public school educa

tion? We divide this question into two sub-ques

tions. (1) Is it implicit in today’s concept of due

process that a child has a right to a public school

education, even though there is no provision in the

state constitution requiring the state to maintain

a public school system? (2) In the fact situation

this case presents, considering especially that the

state now maintains and has for many years

maintained a public school system, does Act 2

violate due process if its effect is to deprive the

children in St. Helena of a public school educa

tion?

We raise a futher question. Is a statute constitu

tional that, in effect, offers children (1) educa

tion on an unconstitutional condition, that is,

attendance at a segregated school, or (2) no educa

tion at all?

The Court is cognizant of Act 258 of 1958 which

provides for a grant-in-aid program. But is grant-

in-aid an adequate constitutional substitute for

public school education, particularly where such

grant-in-aid will, in all probability, result in seg

regated private schools? The Court suggests that

7

consideration be given to this question in the

briefs to be filed.

The Court invites counsel for all parties to file

briefs by Friday, May 5, 1961. The Court also

invites the United States to file a brief as amicus

curiae presenting the views of the United States.

Because of the time required for the filing of the

briefs and the determination of the case, it is

suggested that, irrespective of the result of the

election, the Board agree not to proceed under

Act 2 pending our decision in this case.”

On April 24, 1961, the Court issued the following

orders:

“ This case came on for hearing on plaintiffs’

motion for temporary injunction restraining en

forcement of Act 2 of the Second Extraordinary

Session of 1961 of the Louisiana Legislature.

The Court, finding that the motion raises serious

constitutional questions, invited counsel for all

parties to brief the questions presented. The

United States was also invited to file a brief

amicus. It appearing that questions presented by

the motion may be of serious concern to the States

of the United States;

IT IS ORDERED that the Attorneys General of

the several states of the United States be, and

they are hereby, invited by the court to file an

amicus brief herein by June 5, 1961, covering

the following questions:

1. Would the abandonment by a state of its public

school system deprive children of rights guaran

teed by the Due Process or Equal Protection

Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment?

8

2. Would the answer be the same if the abandon

ment were on a local option basis after a vote

of the electorate authorizing county school au

thorities to close the public schools?

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the Clerk of

this Court mail certified copies of this order to

the Attorney General of each State of the Union.”

On May 1,1961, the Court again issued orders, as

follows:

“ This cause came on for hearing on plaintiffs’

motion for temporary injunction restraining en

forcement of Act 2 of the Second Extraordinary

Session of 1961 of the Louisiana Legislature.

It appearing that additional evidence may be

required for adequate consideration of the serious

constitutional questions presented by the motion,

IT IS ORDERED that the parties to this action

and the United States supplement the record with

additional documentary evidence, including affi

davits and newspapers, covering the following

subjects:

1. The legislative history of Act. 2.

2. The existing private school facilities in St.

Helena Parish for white as well as Negro pupils.

3. The amount expended for public school facili

ties in St. Helena Parish, the source of these funds,

the bonded indebtedness of the St. Helena Parish

School Board for school facilities, and the security

for that indebtedness.

4. Any pertinent facts bearing on the constitu

tional questions raised by the court.

9

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that this additional

evidence be filed in the record not later than

May 22,1961.”

Pursuant to the orders of the Court numerous

briefs amicus curiae were filed, as well as briefs on

behalf of the parties litigant and on August 4, 1961,

oral arguments were presented to the Court and there

after, on August 30, 1961, the Court issued its deci

sion holding Act 2 of the Second Extraordinary

Session of the Louisiana Legislature for 1961 un

constitutional and issued a preliminary injunction

prohibiting appellants herein from enforcing or seeking

to enforce by any means the provisions of the said

statute.

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED

ARE SUBSTANTIAL

On March 17, 1961, the Court by ex parte order

on motion of the United States, under the guise of

“ amicus curiae” ordered the State of Louisiana added

as a party defendant herein. Copy of this order ap

pears as Appendix C hereto. The United States is

without any authority whatsoever in law or equity

to participate piecemeal or otherwise in this litiga

tion as a party litigant.

Higginbotham v. City of Baton Rouge 306 U.S

535;

Butler v. Commonwealth of Pa. 10 How. 402;

Crenshaw v. United States 134 U.S. 99;

Phelps v. Board of Education 300 U.S. 319;

Dodge v. Board of Education 302 U.S. 74;

Snowden v. Hughes 321 U.S. 1;

10

Congressional Record of 1957 Pages 11377 and

11378;

Bill H.R. 6128, 85th Congress (original) Pages

9 and 10;

28 U.S.C. 501;

28 U.S.C. 507;

La. Const, of 1921, Article 12, Section 1; Amend

ment 11, United States Constitution;

Hans v. State of La. 134 U.S. 1;

Larson v. Domestic and Foreign Corp. 337 U.S.

682;

Further, as the State of Louisiana was made

a party defendant in this suit which from its com

mencement was one prosecuted by citizens of one of

the United States, jurisdiction failed. See: Louisiana

Constitution of 1921, Article 19, Section 26, and the

Eleventh Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

Noah et al v. Board of Education, District of

Columbia 106 Fed. Supp. 988;

Parker v. Board of Education of Sumter County

70 S.E. 2d 369 (G a .);

Smith v. Hefner 68 S.E. 2d 783 (N. C .) ;

Stephan v. La. Board of Education 78 So. 2d 18;

Charlottesville v. Allen 240 Fed. 2d 59;

Aerated Products Co. of Philadelphia, Pa. v. De

partment of Health of N. J. et al, 159 Fed.

2d 851;

Ford Company v. Department of Treasury 323

U .S .459;

Baldwin v. G.A.F. Seelig 294 U.S. 511;

U.S. Department of Agriculture, et al, v. Hunter,

et al, 171 Fed. 2d 793;

11

U.S. Department of Agriculture v. Remund 330

U.S. 539;

New Haven Public Schools v. General Service Ad

ministration 214 Fed. 2d 592;

Herrin v. Farm Security Administration 153 Fed.

2d 76;

Thomason v. Works Progress Administration 138

Fed. 2d 342;

N. Dakota-Montana Wheat Growers’ Assn. v. U.S.

66 Fed. 2d 573; certiorari denied; 291 U.S. 672;

Blackmar v. Guerre 342 U.S. 512;

Georgia Railroad and Banking Company v. Red-

wine 342 U.S. 299.

Perusal of the Court’s temporary injunction (Ap

pendix A ) readily reflects that the individual members

of defendant board were cast in equity and the record

shows that the individual members of the board were

not made parties defendant hereto although they were

found to be indispensable parties by judgment of the

Court.

The Court below erred in deciding the constitu

tional issues on facts not germane to the issues, as well

as by misapplication of legal principles.

In its decision below the Court found that Act 2

violated the equal protection clause of the United

States Constitution in two respects; improper classi

fication and illegal evasion.

Before proceeding to discuss these issues, it is

necessary to eliminate one trend of thought which

pervades the lower Court’s opinion. Throughout the

12

opinion the Court takes great pains to point out to

what extent, private schools, if organized, would con

stitute state action.

“ This analysis of Act 2 and related legisla

tion makes it clear that when the Legislature

integrated Act 2 with its companion measures,

especially the “ private” school acts, as part of a

single carefully constructed design, constitution

ally the design was self-defeating. Of necessity,

the scheme requires such extensive state control,

financial aid, and active participation that in

operating the program the state would still be pro

viding public education. The state might not be

doing business at the old stand; but the state

would be participating as the senior, and not

silent, partner in the same sort of business. The

continuance of segregation at the state’s public-

private schools, therefore, is a violation of the

equal protection clause.” (Court’s opinion, page

42).

“ This scheme of the Louisiana Legislature

to deny school children constitutional rights is

not new. It has been tried before, with similar

results. In declaring such a scheme unconstitu

tional, the Eighth Circuit, in Aaron v. Cooper,

261 F. 2d 97, 106-107, relied heavily on this pro

nouncement by the Supreme Court: ‘State sup

port of segregated schools, through any arrange

ment, management, funds, or property cannot be

squared with the Fourteenth Amendment’s com

mand that no State shall deny to any person with

in its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.’

Aaron v. Cooper, supra, 19. The ruling here must

be the same.” (Court’s opinion, page 43).

13

This would merit serious consideration if the

question before the Court were, are those schools

discriminating in admitting students because of race,

color or creed, but absent that question the Court’s

discussion is rankest dicta and serves only to confuse

the real constitutional issue which must be decided.

'May a Parish constitutionally abandon a public school

system?

Let us first consider whether Act 2 affects the

Parish of St. Helena and its residents in such a

manner as to constitute an illegal or unconstitutional

classification, or, for that matter, any type of clas

sification whatsoever.

As a general proposition the laws enacted by a

State Legislature must apply equally to all persons

within the confines of the State. There are, however,

two methods by which the laws enacted by the State

Legislature may vary within the State. First, the

Legislature may enact laws applicable to a certain

class or classes within its boundaries. Legislative

classification if not palpably arbitrary and if it may

reasonably be conceived to rest on some real and

substantial difference or distinction bearing a just

and fair relation to the Legislation is no denial of

equal protection of the laws. 16A C.J.S. Section 505

Page 314. This is the type of Legislation passed on

by the Court in the case of James v. Almond, 170

Fed. Supp. 331.

In that case the Legislature of the State of Vir

ginia had passed an act permitting the Governor of

14

the State of Virginia to assume control of schools

under certain conditions. Pursuant to that statute,

the Governor by executive order seized control of

certain schools integrated by the City of Norfolk. He

then proceeded to order the desegregated schools not to

open even though other schools in the city and state

were open. The Court stated:

“ Tested by these principles we arrive at the in

escapable conclusion that the Commonwealth of

Virginia, having accepted and assumed the re

sponsibility of maintaining and operating public

schools, cannot act through one of its officers to

close one or more public schools in a state solely

by reason of the assignment to, or enrollment or

presence in, the public school of children of dif

ferent races or colors, and at the same time, keep

other public schools throughout the state open on

a segregated basis.”

According to the Court’s opinion, the Virginia

Legislation would result in some of the children in

the state attending public schools while the other

children in the state would not be afforded the same

privilege, thus not affording equal treatment within

the political unit establishing the policy. Since there

was no reasonable basis for the different treatment

it was an illegal classification which denied to certain

citizens of the State the equal protection of the laws

guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The second method by which different laws and

different rules may prevail in various localities of the

State is the “ home rule” or “ local option” statutes.

15

This type of Legislation is a permissive grant by the

State to its political subdivisions to establish rules

and/or regulations under which they choose to operate.

“ Home rule” permits localities, political subdivisions,

etc., to adopt certain laws and rules by which it

chooses to be governed. When the right of local option

is exercised by a political subdivision of the State,

there is no necessity of applying the rule of legislative

classification since the rule, law or regulation will

apply equally to all persons within the geographical

or political unit, and consequently cannot result in

denial of equal protection. The validity of the so-called

“ home rule” or “ local option” adoption of different

rules within a political or geographical area was ap

proved by the Supreme Court in the case of Salzburg

v. State of Maryland, 346 U.S. 545, wherein the Court

said:

“ There seems to be no doubt that Maryland could

validly grant home rule to each of its 21 counties

and to the City of Baltimore to determine this

rule of evidence by local option.”

Again in the case of Greensboro v. Tonkins, 276

Fed. 2d 890, the Court was faced with a problem

where a municipality was going to cease to offer a

certain service even though the same service was

offered to their local citizens by other communities

throughout the State. The Court held that the city

could validly sell its swimming pool and cease opera

tion thereof even though the sale was made pursuant

to and authorized by a statute of the State of North

Carolina.

16

“ North Carolina private laws 1923 Ch. 37, Sec

tion 79 has amended N. C. Sess. Laws 1957 Ch.

960, Section 4.”

In effect, the Court permitted the City of Greensboro

to withdraw a service offered to the citizens of the

City of Greensboro pursuant to a State statute, pro

vided that it affected all citizens of that City the

same, without regard as to how it affected the rest

of the citizens of the State.

In discussing and commenting upon this decision,

a commentator of the Harvard Law Review, Volume

72, Page 1567, stated as follows:

“ It could be argued that since the municipality is

merely a creation of the state, and since its power

to sell is authorized by State statute, its action in

closing the pool should be attributed to the state,

thus presenting a situation similar to that of the

James case, assuming that other municipal swim

ming pools in the state remained open. Neverthe

less, it appears that a municipality should be re

quired to act only in relation to persons within

its jurisdiction, and that it fulfills its constitu

tional obligations when it treats all such persons

equally. To require more would place a virtually

impossible burden upon municipalities, and would

tend to defeat the diversity which is one of the

aims of local government. Thus, although discrimi

nation by a municipality among its residents in

the operation of recreational facilities is properly

attributed to the state, it does not seem desirable

to extend the ‘state action’ concept so as to trans

form a nondiscriminatory municipal act into state

discrimination under the fourteenth amendment.”

17

This distinction was again recognized by the Fifth

Circuit Court of Appeal in the case of Montgomery v.

Gilmore, 277 Fed. 2d 364. Here the Court again noted

the difference and distinction between the application

of a rule passed by a political subdivision to the persons

located within that subdivision, and a general classi

fication statute by the State affecting different classes

in different ways. In footnote 4 of the case, the Court

stated as follows:

“ In our opinion, the closing of all the public parks

of the City does not violate the equal protection

of the laws of the citizens of Montgomery, under

the doctrines of James v. Almond, D.C.E.D. Va.

1959 170 Fed. Supp. 331; James v. Duckworth,

D.C.E.D. Va. 1959, 170 Fed. Supp. 342, and

Harrison v. Day, 1959, 200 Va. 439, 106 S.E. 2d

636.”

The Federal Courts in this State have acknowl

edged and the United States Supreme Court has af

firmed the proposition that the various school boards

within the State of Louisiana may, subject to a permis

sive statute of the Legislature, adopt rules which

would not be uniform throughout the State, but which

would be completely uniform and equally administered

within the unit of the parish itself.

Hughes v. Caddo Parish School Board, et al, 57

F. Supp. 508, affirmed 323 U.S. 685.

In that case, the Legislature gave to each parish

school board in the State the power to abolish high

school fraternities and sororities and further to dis

18

cipline any student who remained a member thereof.

This statute was attacked on many grounds, one of

which was that it was a violation of the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment clause

of the United States Constitution. The Court in com

menting on the claim of denial of equal protection

stated, on page 512:

“ In the instant case the student is a member of

the fraternity chapter in Byrd High School where

entrance and enrollment are sought. Because of

the disciplinary measures which the State Legis

lature and the Caddo Parish School Board are

seeking to establish in the schools under their

respective police authority, this student may be

legally compelled to comply with these measures.”

“ The manner of application of the law becomes

adsolutely uniform— there is not even the sem

blance of any discrimination as was alleged to

exist in the Waugh case, and which was pressed

before and considered by the Supreme Court of

the United States.”

The statute involved in that case is quite similar

to the one herein, in that the Legislature gave the per

missive right to the various local school boards to

adopt a certain set of rules and procedures. It was

conceded in the case that the school boards throughout

the State might not adopt the same practice, however

if they did though, it would apply to all students

within that political unit. That case and the one at bar

cannot be distinguished with regard to the application

of the equal protection clause.

19

The Court in the decision below attempts to dis

tinguish the principles set forth in the local option

liquor law cases. Rippey v. State of Texas 193 U.S.

504 and Lloyd v. Dollison 194 U.S. 445.

The Court reasoned that the local option statutes

were good in those matters only because the State had

complete and absolute control over the distribution

and sale of liquor. The converse is true. 16-A C.J.S.

Constitutional Law, Section 6, 512 at page 358:

“ The constitutional guaranty of the equal pro

tection of the laws is applicable to regulations

with respect to intoxicating liquors and the sale

thereof. However, the control of the sale, use,

transportation, and consumption of intoxicating

liquor, being peculiarly within the province of

legislative powers, the regulation, or even the pro

hibition thereof, does not necessarily deny anyone

equal protection of the laws.”

The only difference between education and liquor

trade, insofar as State control is concerned, is one of

degree. The State may prohibit the sale or manufac

ture of liquor, while it may not prohibit education,

but this does not in the least prohibit it from delegating

to localities the power which it does retain.

The final determination of educational policies in

governmental units or subdivisions of the State is not

foreign to Louisiana or to other states in the union.

This may be done on a county basis, or as in many

states by school districts. Index Digest of State Con

stitutions, p. 390. It is generally recognized that a

20

state legislature may authorize residents of local school

districts to vote upon bonding, finances and other

matters of government connected with the operation

of local schools. Kee v. Parks, 153 Tenn. 306, 283 S.W.

751; In Re School Code of 1919, 7 Boyce 406, 108 Atl.

39; State v. Lamont, 105 Kan. 134, 181 Pac. 617. A

clear statement of the generally recognized rule as re

gards local operation of schools is found in 16 C.J.S.,

Constitutional Law, Sec. 142, at page 683, where it is

said:

“ The legislature may provide laws as to the es

tablishment, division, alteration, enlargement, or

abolition of schools and school districts, and the

control of schools to take effect when adopted by

a vote of the people of the district.”

In People v. Cowen, 283 111. 308, 119 N.E. 335

(1918) the Illinois Supreme Court stated with refer

ence to the legislative power to delegate to a local body

the power to abolish a high school:

“ The legislature has supreme power over public

corporations, and may divide, alter, enlarge, or

abolish them as in the legislative judgment the

public welfare may require. This power may be

exercised by the Legislature itself by direct legis

lation, or it may delegate the power to certain

officers, courts, or the electors of a municipal-

The court concluded that the electors of a school

district could properly vote to abolish a school.

The principle of local option is too well established

to charge it with being contrary to the Federal Con

21

stitution as such. Downs v. Boonton, 99 N.J. Law 40,

122 A. 721; State v. Baxter, 195 Wis. 437, 219 N.W.

858; State v. Briggs, 46 Utah 288, 146 Pac. 261; Ohio

v. Dollison 194 U.S. 445.

It must be concluded that no constitutional objec

tion can be raised to the closing of schools on a local

option basis.

The other basis upon which the Court found Act

2 unconstitutional is :

“ Most immediately, it is a transparent artifice

designed to deny the plaintiffs their declared

constitutional right to attend de-segregated

schools.”

I f this is the doctrine of the United States Dis

trict Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, it

is without a doubt novel, startling and entirely un

founded in law. The Court in its holding here makes

it mandatory that the parish furnish to the plaintiffs

a public school and further that said public school

must be desegregated. The basis for such a judicial

pronouncement can be found neither in the law nor

jurisprudence.

The Court herein apparently misconstrued the

doctrine of the Brown case. The same was analyzed

and its doctrine clearly set forth in the case of Briggs

v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776, 777, wherein the Court

said :

“ . . . It is important that we point out exactly

what the Supreme Court has decided and what

22

it has not decided in this case. It has not decided

that the federal courts are to take over or reg

ulate the public schools of the states. It has not

decided that the states must mix persons of dif

ferent races in the schools or must require them

to attend schools or must deprive them of the

right of choosing the schools they attend. What

it has decided, and all that it has decided, is

that a state may not deny to any person on ac

count of race the right to attend any schools that

it maintains. . . Nothing in the Constitution or

in the decision of the Supreme Court takes away

from the people freedom to choose the schools

they attend. The Constitution, in other words,

does not require integration. It merely forbids

discrimination. . . .”

This interpretation of the Brown case has been

adopted by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in

Avery v. Wichita Falls Independent School District

241 Fed. 2d 330, certiorari denied 353 U.S. 938, as

well as by other Federal Courts. Thompson v. School

Board of Arlington, 144 F. Supp. 239 (D.C. Va. 1956),

a ff ’d sub nom. School Board of Charlottesville v. Allen,

240 F 2d 59 (C.A. 4th 1956), cert. den. 77 S. Ct, 667;

Borders v. Rippey, 247 F2d 268 (C.A. 5th 1960); Cal

houn v. Board of Education of Atlanta, 188 F. Supp.

401 (D.C. Ga. 1959); Henry v. Godsell et al., 165 F.

Supp. 87 (D.C. Mich. 1958); Kelley v. Board of Ed

ucation of Nashville, 270 F. 2d 209 (C.A. 6th 1959),

cert. den. 361 U.S. 924; Dove v. Parham, 181 F. Supp.

504 (D.C. Ark. 1960); Holland v. Board of Public

Instruction, 258 F2d 730 (C.A. 5th 1958); Montgom-

23

enj v. Gilmore, 277 F2d 364 (C.A. 5th 1960).

Additionally, the Court below has in effect pro

claimed that the plaintiffs have an absolute, uncon

ditional, constitutional right to attend a de-segregated

school. This premise, that the plaintiffs have a right

to attend a school at all, is again without support in

law.

Appellants do not doubt that if public education

were offered to some students in an area, it would

have to be granted to all students on an equal basis,

however the requisite of equality of a service fur

nished does not obligate the state to furnish the service.

In the case of Everson v. Board of Education,

330 U.S. 1, 21, the late Justice Jackson, stated:

“ The Constitution says nothing of education. It

lays no obligation on the states to provide schools

and does not undertake to regulate state systems

of education if they see fit to maintain them.”

In addition to extending the doctrine of the

Brown case, as stated above, the Court below in its

opinion developed three new axioms which can be

used for constitutional interpretation. They are uh-

constitutionality by association, conjecture and priv

ilege.

This Court for the past several years has on many

occasions been confronted with the question of the

validity of “ guilt by association” . The Court’s opinion

below has developed a companion doctrine which

might well be labeled “unconstitutionality by associa

tion” . The Court in its opinion found that other acts

24

declared unconstitutional must necessarily pass their

unconstitutionality on to Act 2.

“ The Louisiana Legislature has confected

one ‘evasive scheme’ after another in an effort to

achieve this end. This Court has held these un

constitutional in one decision after another, af

firmed by the Supreme Court. Yet they continued

to be enacted into law. . .”

“ On its face, this section appears inoffensive.

It is only after an analysis of the school closing

measure, other sections of the act and related

legislation that the purpose, mechanics, in effect

of the clan emerged.”

The Court furnishes absolutely no authority for

the proposition that it possesses the power to invali

date acts of the sovereign state solely on the finding

that those acts are part of a pattern or plan. No cri

terion of standards were eluded to which might

define this new principle. Presumably, the Court be

lieves that because Louisiana has sinned constitu

tionally before, every other act which its legislature

subsequently enacts is likewise invested with the same

infirmity to such an extent as to dispense with the

necessity of individual adjudication. Negro plaintiffs

have merely to shout the magic word “ pattern” , and

invalidation follows as a matter of course.

We think the true rule is stated in Dove v. Par

ham, 176 F. Supp. 242 reversed in part in other

grounds, 271 Fed. 2d 132:

“ Implicit the rules applied in those cases and

controlling in the Arkansas pupil placement law

25

being within constitutional boundaries is the

principle, that a state plan for resistance to racial

integration in its public schools, is without sig

nificance as to the constitutionality of such laws

if legitimate and constitutional means are used

in the operation of the plan and the attainment

of its objective.”

Throughout its opinion the Court pre-assumes to

determine how Act 2 and other Acts of the State of

Louisiana are to be inter-related, how they will be ap

plied, how they will effect the petitioners as well as

others in the parish, and their eventual effect upon

the individual community and state. Conjecture,

suspicion and clairvoyance are indeed strange ave

nues by which to arrive at the constitutional deter

mination of the validity of a sovereign state stat

ute. This Court, in a recent case, frowned upon such

methods of arriving at a determination of the consti

tutionality of a statute when it said:

“ The very foundation of the power of the federal

courts to declare Acts of Congress unconstitu

tional lies in the power and duty of those courts

to decide cases and controversies properly before

them. This was made patent in the first case here

exercising that power— ‘the gravest and most

delicate duty that this Court is called on to per

form’. Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137, 177—

180, 2 L. Ed. 60. This Court, as is the case with

all federal courts, “ has no jurisdiction to pro

nounce any statute, either of a state or of the

United States, void, because irreconcilable with

the constitution, except as it is called upon to ad-

26

judge the legal rights of litigants in actual con

troversies. In the exercise of that jurisdiction, it

is bound by two rules, to which it has rigidly ad

hered : one, never to anticipate a question of con

stitutional law in advance of the necessity of de

ciding it; the other, never to formulate a rule of

constitutional law broader than is required by the

precise facts to which it is to be applied. Liver

pool, New York & Philadelphia S.S. Co. v. Com

missioners of Immigration, 113 U.S. 33, 39, 5

S. Ct. 352, 355, 27 L. Ed. 899. Kindred to these

rules is the rule that one to whom application of a

statute is constitutional will not be heard to attack

the statute on the ground that impliedly it might

also be taken as applying to other persons or

other situations in which its application might

be unconstitutional. United States v. Wurzbach,

280 U.S. 396, 50 S. Ct. 167, 74 L. Ed. 58; Heald

v. District of Columbia, 259 U.S. 114, 123, 42

S. Ct. 434, 435, 66 L. Ed. 852; Yazoo & Mississippi

Valley R. Co. v. Jackson Vinegar Co., 226 U.S.

217, 33 S. Ct. 40, 57 L. Ed 193; Collins v. State

of Texas, 223 U.S. 288, 295— 296, 32 S. Ct. 286,

288, 56 L. Ed. 439; People v. State of New York

ex rel. Hatch v. Reardon, 204 U.S. 152, 160-161,

27 S. Ct. 188, 190-191, 51 L. Ed. 415. Cf. Voeller

v. Neilston Wholesale Co., 311 U.S. 531, 537, 61

S. Ct. 376, 379, 85 L. Ed. 322; Carmichael v.

Southern Coal & Coke Co., 301 U.S. 495, 513, 57

S. Ct. 868, 874, 81 L. Ed. 1245; Virginian R. Co.

v. System Federation, 300 U.S. 515, 558, 57 S. Ct.

592, 605, 81 L. Ed. 789; Blackmer v. United

States, 284 U.S. 421, 442, 52 S. Ct. 252, 257, 76

L. Ed. 375; Roberts & Schaefer Co. v. Emmerson,

271 U.S. 50, 54-55, 46 S. Ct. 375, 376-377, 70 L.

27

Ed. 827; Jeffrey Mfg. Co. v. Blagg, 235 U.S. 571,

576, 35 S. Ct. 167, 169, 59 L. Ed. 364; Tyler v.

Judges of the Court of Registration, 179 U.S.

405, 21 S. Ct. 206, 45 L. Ed. 252; Ashwander v.

Tennessee Valley Authority 297 U.S. 288, 347-

348, 56 S. Ct. 466, 483-484, 80 L. Ed. 688 (con

curring opinion). In Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S.

249, 73 S. Ct. 1031, 97 L. Ed. 1586, this Court

developed various reasons for this rule. Very

significant is the incontrovertible proposition

that it ‘would indeed be undesirable for this

Court to consider every conceivable situation

which might possibly arise in the application of

complex and comprehensive legislation.’ Id., 346

U.S. at page 256, 73 S. Ct. at page 1035. The

delicate power of pronouncing an Act of Congress

unconstitutional is not to be exercised with refer

ence to hypothetical cases thus imagined. The

Court further pointed to the fact that a limiting

construction could be given to the statute by the

court responsible for its construction if an appli

cation of doubtful constitutionality were in fact

concretely presented. We might add that applica

tion of this rule frees the Court not only from

unnecessary pronouncement on constitutional is

sues, but also from premature interpretations of

statutes in areas where their constitutional ap

plication might be cloudy.” U.S. v. Raines 362

U.S. 17

Appellants, until the decision of the Court below,

were of the opinion that all parts of the Constitution

were of equal importance and that all privileges, rights

and immunities granted to the citizens of the United

States were equally protected. It was with conster

28

nation we discovered the contrary, in the decision of

the Court below:

“ Irrespective of the express terms of a statute,

particularly in the area of racial discrimination,

Courts must determine its purposes as well as its

substance and effect.” (emphasis supplied)

Absent the feeling of the Court, as expressed

above, appellants feel that many of the questions

raised and decided in this case would have never re

ceived serious consideration, had they arisen in dif

ferent context. The fact that the United States Gov

ernment was the paladin of the plaintiffs or that

the states involved had expressed disagreement of

the Supreme Court decisions of late, or that the

principles are here challenged by those who currently

are special favorite of the laws, does not change the

law. As appropriately stated by Mr. Justice Bradley,

almost eighty years ago in the Civil Rights cases 109

U.S.3:

“ When a man has emerged from slavery, and by

the aid of the beneficient legislation has shaken

o ff the inseparable concommitants of that state,

there must be some stage in the progress of his

elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen,

and ceases to be a special favorite of the laws,

and when his rights as a citizen, or a man, must

be protected in the ordinary modes by which

other men’s rights are protected.” (emphasis add

ed)

29

CONCLUSION

WHEREFORE it is respectfully submitted that

this Court has jurisdiction of this Appeal and it is

respectfully suggested this Court find this case an

appropriate one for reversal and dismissal of the com

plaint, dissolving and recalling the temporary injunc

tion.

Of Counsel:

CARRO LL BUCK,

M. E. CULLIGAN,

GEORGE M. PONDER,

JOHN E. JACKSON, JR.,

W IL LIA M P. SCHULER,

DOROTH Y W O LBRETTE,

L. K . CLEM ENT, JR.

H A R R Y J. KRON, JR.,

Assistant Attorneys General.

ALB IN P. LASSITER,

District Attorney,

i-th Judicial District,

State of Louisiana.

THOM PSON L. CLARKE,

District Attorney,

6th Judicial District,

State of Louisiana.

LOUIS H. PAD G ETT, JR.,

District Attorney,

26th Judicial District,

State of Louisiana.

R esp ectfu lly subm itted,

JACK P. F. GREM ILLION,

Attorney General,

State of Louisiana.

DUNCAN S. KEMP,

District Attorney,

21st Judicial District,

State of Louisiana.

W. SCOTT W ILKINSON,

Special Assistant

Attorney General.

V IC TO R A . SACHSE,

Special Assistant

Attorney General.

30

PROOF OF SERVICE

I, JACK P. F. GREMILLION, Attorney General

for the State of Louisiana, and attorneys for appellants

herein and a Member of the Bar of the Supreme

Court of the United States, do hereby certify that

copies of the foregoing Jurisdictional Statement for

appellants were served upon the appellees through

their counsel of record, herein below named, by

placing the same in the United States mail, addressed

to them at their offices with sufficient postage there

to annexed:

Mr. A. P. Tureaud, 1821 Orleans Avenue, New

Orleans, Louisiana, Mr. Robert L. Carter, 20 West

40th Street, New York 18, New York, via air mail,

and Mr. Jack Greenberg and Mr. Thurgood Marshall,

10 Columbus Circle, New York, New York, via air

mail.

JACK P. F. GREMILLION,

Attorney General,

State of Louisiana.

31

APPENDIX “A ”

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BATON ROUGE DIVISION

No. 1068 CIVIL ACTION

Lawrence Hall, Et A l, Plaintiffs

v.

St. Helena Parish School Board, Et A l,

Defendants

Thurgood Marshall

A. P. Tureaud

A. M. Trudeau, Jr.

Jack Greenberg

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Jack P. F. Gremillion, Attorney General of Lou

isiana

L. K. Clement, Jr., Assistant Attorney General

Weldon Cousins, Assistant Attorney General

Michael E. Culligan, Assistant Attorney General

John M. Currier, Assistant Attorney General

John E. Jackson, Jr., Assistant Attorney General

George Ponder, Assistant Attorney General

William P. Schuler, Assistant Attorney General

W. Scott Wilkinson, Special Assistant Attorney

General

Duncan Kemp, District Attorney for St. Helena

Parish

E. Freeman Leverett, Deputy Attorney General

of Georgia

Gordon Madison, Deputy Attorney General of

Alabama

Leslie Hall, Deputy Attorney General of Alabama

32

Attorneys for Defendants

M. Hepburn Many, United States Attorney

Harold H. Greene, United States Department of

Justice

Attorneys for United States of America,

Amicus Curiae

WISDOM, Circuit Judge, and CHRISTEN-

BERRY and WRIGHT, District Judges:

Undeterred by the failure of its prior efforts, the

Louisiana Legislature continues to press its fight for

racial segregation in the public schools of the state.

Today we consider its current segregation legislation,

the keystone of which, the local option law, is under

attack in these proceedings.

On May 25, 1960, this court entered its order

herein restraining and enjoining the St. Helena Parish

School Board and its superintendent from continuing

the practice of racial segregation in the public schools

under their supervision “ after such time as may be

necessary to make arrangements for admission of

children to such schools on a racially non-discrimina-

tory basis with all deliberate speed.” The Court of

Appeals affirmed this judgment on Fedruary 9, 1961.1

On February 9, 1961, the very day of the af

firmance of the order of this court,2 the Governor

of the State called the Second Extraordinary Session

1St. Helena Parish School Board v. Hall, 5 C ir., 287 F . 2d 376.

“O rder o f th is cou rt req u ir in g desegregation o f the B aton R ou ge

p u blic schools and f iv e state trad e schools w ere a lso a ff irm e d on Feb.

9, 1961. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board v. Davis, 5 C ir., 287

F . 2d 380 ; Louisiana State Board of Education v. Allen, 5 C ir., 287

F . 2d 3 2 ; Louisiana State Board of Education v. Angel, 5 C ir., 287 F .

2d 33.

33

of the Louisiana Legislature for 1961 into session

to act “ relative to the education of the school children

of the State * * * for the preservation and protec

tion” of state sovereignty. Within a few days of the

call, he certified as emergency legislation what be

came Act 2“ of that session, the local option law in

suit, as well as related legislation designed to continue

racial segregation in the public schools, in spite of the

desegregation order of this court in this case in partic

ular and desegregation orders in general. As is mani

fest from the legislative history of the statute and

an analysis of its provisions as these are related to

cognate legislation, the sub-surface purpose of Act 2

is to provide a means by which public schools under

desegregation orders may be changed to “ private”

schools operated in the same way, in the same build

ings, with the same furnishings, with the same money,

and under the same supervision as the public schools.

In addition, as part of the plan, the school board of

the parish where the public schools have been “ closed”

is charged with responsibility for furnishing free

lunches, transportation, and grants-in-aid to the

children attending the “ private” schools.

The statute in suit violates the equal protection

clause on two counts. Most immediately, it is a trans

parent artifice designed to deny the plaintiffs their

declared constitutional right to attend desegregated

public schools. More generally, the Act is assailable

because its application in one parish, while the state 3

3La. R .S . 17 :350.

34

provides public schools elsewhere, would unfairly dis

criminate against the residents of that parish, irre

spective of race.

The language of the Supreme Court in Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 17, cannot be disregarded: “ The

constitutional rights of children not to be discrimi

nated against in school admission on grounds of race

or color declared by this Court in the Brown case

can neither be nullified openly and directly by state

legislators or state executive or judicial officers, nor

nullified indirectly by them through evasive schemes

for segregation whether attempted ‘ingeniously or in

genuously.’ Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128, 132.”

These words tell the Louisiana Legislature, as clearly

as language can, that school children may not be

denied equal protection of the laws, may not be dis

criminated against in school admissions, on grounds

of race or color. The Louisiana Legislature has con

fected one “ evasive scheme” after another in an effort

to achieve this end. This court has held these un

constitutional in one decision after another affirmed

by the Supreme Court.4 Yet they continue to be enacted

into law.

As with the other segregation statutes, in

drafting Act 2 the Legislature was at pains to use

language disguising its real purpose. All reference to

4See Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, E .D . L a ., 138 F . Supp.

337, a ffirm e d , 242 F . 2d 156 ; id., 163 F . Supp. 701, a ffirm e d , 268 F .

2d 7 8 ; id ., 187 F . Supp. 42, a ffirm e d , 365 U .S . 569 ; id ., 188 F . Supp.

916, a ff irm e d , 365 U .S . 569 ; id ., 190 F . Supp. 861, a ffirm e d , 366 U .S .

2 1 2 ; id ., 191 F . Supp. 871, a ffirm e d , 366 U .S . 212 ; id ., 191 F . Supp.

871, a ff irm e d , ------ U .S ............ (6 -1 9 -6 1 ) ; id., 194 F . Supp. 182.

35

race is eliminated, so that, to the uninitiated, the

statute appears completely innocuous. For example,

the first section of Act 2 reads:

“ In each parish of the state, and in each munici

pality having a municipally operated school sys

tem, the school board shall have authority to

suspend or close, by proper resolution, the opera

tion of the public school system in the elemen

tary and secondary grades in said parish or

municipality, but no such resolution shall be

adopted by any such board until the question

of suspending or closing the operation of such

public school system in such grades shall have

been submitted to the qualified electors of the

parish or municipality, as the case may be, at

an election conducted in accordance with the

general election laws of the state, and the majority

of those voting in said election shall have voted

in favor of suspending or closing the operation

of such public school system.”

On its face, this section appears inoffensive. It is only

after an analysis of this school closing measure with

other sections of the Act and related legislation that

the purpose, mechanics, and effect of the plan emerge.5 6

(Irrespective of the express terms of a statute,

particularly in the area of racial discrimination, courts

must determine its purpose as well as its substance

and effect.) “ A result intelligently foreseen and offer

ing the most obvious motive for an act that will

bring it about, fairly may be taken to have been a

5 A c t 2, o f cou rse , m u st be read w ith oth er leg is la tion in p a ri

m ateria . See 2 Sutherland , S ta tu tory C on stru ction (3 rd E d. 1 9 4 3 ),

§§5201-5202, pp . 529-539. See a lso cases cited in N ote 4.

36

purpose of the act.” Miller v. Milwaukee, 272 U.S.

713, 715. Moreover, “ acts generally lawful may be

come unlawful when done to accomplish an unlawful

end.” Western Union Tel. Co. v. Foster, 247, U.S.

105, 114.” The defendants argue that we should not

probe for the purpose of this legislation, that we

should ignore the events which led up to and accom

panied its passage, and determine its validity based

on its language. But “ * * * we cannot shut our eyes

to matters of public notoriety and general cognizance.

When we take our seats on the bench we are not

struck with blindness, and forbidden to know as judges

what we see as men.” 7

The sponsors of this legislation, in their public

statements, if not in the Act itself, have spelled out

its real purpose.8 Administration leaders repeatedly

said that the local option bill should not be con

strued as indicating the state would tolerate even

token integration. The law would be used in parishes

either having or threatened with desegregation: Or

leans, East Baton Rouge and St. Helena. Times-

Picayune, February 20, 1961. The program for the

“See a lso Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U .S . 23 3 ; Go-

million v. Lightfoot, 364 U .S . 339, 347-348; Rice v. Elmore, 4 C ir.,

165 F . 2d 387, 391; Baskin v. Brown, 4 C ir., 174 F . 2d 391, 393.

'M r . J u stice F ie ld , s itt in g as C ircu it Ju d ge , in Ho Ah Kow v.

Nunan, 9 C ir., 5 S aw yer 552, 560.

“In L ou isian a , as m ost states, the leg is la tiv e debates, com m ittee

proceed in gs, and com m ittee rep orts are n ot record ed o ffic ia l ly . G oin g

to the n ext best record s , n ew sp ap ers, w e fin d in th e re co rd o f th is

case a m ass o f con tem p ora ry n ew sp ap er articles , f ile d b y the p la in

t i f f s and b y am icus cu riae , b ea rin g on the leg is la tive h isto ry o f A c t

2 and its re la ted m easures. A ff id a v its fr o m the au th ors o f the articles

a ttest th e ir a ccu ra cy . In all in stances th ey a re p a r t o f th e o f f ic ia l

record s. T h e ir re lia b ility is evidenced b y th e ir substan tia l agreem ent.

37

legislative session which adopted Act 2 was worked

out by the so called “ Liaison Committee,” a committee

charged with co-ordinating the administration’s seg

regation strategy. Times-Picayune, February 11,1961.

Representative Risley Triche, administration floor

leader and sponsor of Act 2, told the House of Rep

resentatives, “ The bill does not authorize any school

system to operate integrated schools. We haven’t

changed our position one iota. This bill allows the

voters to change to a private segregated school sys

tem. That’s all that it’s intended to do. I don’t think

we want to fall into the trap of authorizing

integrated schools by the votes of the people.

This bill doesn’t allow that and we’re not falling

into that trap.” Times-Picayune, February 18, 1961.

The president pro tern of the Senate explained

the bill as follows: “ As I see it, Louisiana is entering

into a new phase in its battle to maintain its segre

gated school system. The keystone to this new phase

is the local option plan we have under considera

tion.” 9 Times-Picayune, February 20, 1961. And

"R epresentative S a lvad or A n zelm o, one o f the tw o leg is la tors to

v o te a ga in st A c t 2 declared th a t in a ctu a lity the lo ca l op tion w a s a

m isn om er; it did n ot g iv e the peop le an option because i f th ey voted

to keep the schools open , th ose schools w hich a re in tegrated w ould be

fo r ce d to close because state fu n d s w ou ld be cu t o f f . R epresen tative

A n zelm o sa id : “ T h ey are n o t g o in g to g e t an y m on ey i f th ey keep

the schools open. W e g iv e them n o choice. I sa y th is is a had b ill

because th e in tent is to p os itive ly k ill p u b lic education in L ouisiana.

W e w ill k ill the you th o f L ou isiana, w e k ill the asp ira tion s and hopes

o f L ou isiana.

Y o u ’ll be haunted b y th a t vote th e rest o f y ou r life , because th .>

p oor peop le o f th is state w ill n o t be able to g e t an education . In

e f fe c t , w e are g iv in g the peop le n o option w hatever. T h e on ly th in g

w e a re d o in g is p rov id in g the a pp aratu s to close th e schools o f th is

state .” Shreveport Times, F eb . 18, 1961.

38

segregation leader Representative Wellborn Jack was

even more explicit: “ It gives the people an oppor

tunity to help fight to keep the schools segregated. We

are the ones who have been speaking for segregation.

This is going to give the people in all 64 parishes the

right to speak by going to the polls. This is just to

recruit more people to keep our schools segregated,

and we’re going to do it in spite of the federal govern

ment, the brainwashers and the Communists.”

Shreveport Times, February 18, 1961. In short, the

legislative leaders announced without equivocation

that the purpose of the packaged plan was to keep the

state in the business of providing public education on

a segregated basis.

The legislative scheme here, once revealed, is

disarmingly simple. Section l 10 of Act 2 provides a

means for “ closing” the public schools in a parish.

Section 1311 of the Act provides that the school board

may then “ lease, sell, or otherwise dispose of, for cash

or on terms of credit, any school site, building or

facility not used or needed in the operation of any

schools within its jurisdiction, on such terms and con

ditions and for such consideration as the school board

shall prescribe.” Of course, to the extent that such

conveyances, denominated “ sales,” are for less than

the fair value of the property, they are gifts constitut

ing continuing state aid to “private” schools. Presum

ably, this sale would be made to educational coopera

10La. R .S . 17 :350.1 .

” La. R .S . 17:350.13 .

39

tives, created pursuant to Act 257 of 1958,12 which

would operate the “ private” schools with state money

furnished by the grant-in-aid program provided for in

Act 313 of the Second Extraordinary Session of

I960.14

“ Under Act 3 of the Second Extraordinary Ses

sion of 1960, the parish school boards would continue

to supervise the “ private” schools, under the State

Board of Education, by administering the grant-in-

aid program of tuition grants payable from state and

local funds. This act is identical with Act 258 of 1958,

which was repealed, except that it omits the earlier

explanation that tuition grants are available “where

no racially separated public school is provided” and it

deletes all other references showing its sub-surface

purpose. Financial aid is direct from state to school:

tuition checks are to be made out by the state jointly

to the parent and the school.13 Under Section 121” of

12La. R .S . 17 :2801.

13La. R .S . 17 :2901.

“ A c t 9 o f the Second E x tra ord in a ry Session o f 1961 tran sfers

$2,500,000 fr o m the P u blic W e lfa re F u nd to the E du cation E xpense

G ra n t F u n d fo r g ra n t-in -a id use, and A c t 10 o f the sam e session

(L a . R .S . 4 7 :3 1 8 ) tra n s fe rs $200,000 m on th ly fr o m the sales ta x co l

lection s to the sam e fu n d fo r the sam e purpose.

“ T he la rg e n um ber o f C ath olic schools in L ou isian a presented

the leg is la tu re w ith an insoluble problem . I f th e tu ition g ra n ts are

“ b en e fits to the ch ild ” , and n ot state su p p ort o f th e schools, the

leg is la tion is d iscr im in a tory on its fa c e in exclu d in g ch ildren atten d in g

ch u rch schools. I f the g ra n ts am ount to state su p p ort o f schools,

su p p ort o f re lig iou s in stitu tions is proh ib ited b y the F ir s t A m en d

m ent— n ot to speak o f the fe d e ra l con stitu tiona l proh ib ition aga in st

state action in su p p ortin g segregated schools o r the state proh ib ition

a ga in st spen din g pu blic fu n d s f o r p r iva te purposes.

The am ount o f each g ra n t m a y equal th e p er-d ay , per-stu den t

am ount o f state and loca l m on ey expended on pu b lic schools d u rin g

the prev iou s year. I t is determ ined b y the g ov ern in g au th ority o f the

40

Act 2 in suit, the state would also have the responsibil

ity of furnishing such “ private” school children with

school lunches and transportation, the cost of which

would be borne by the state. The program is to be

administered by the State Board of Education, with

the assistance of each local board. In addition, in

order to insure tenure for the teachers in the “pri

vate” schools, Section 1 of Act 4” of the Second Ex

traordinary Session of 1961 empowers the educational

cooperatives to enter into contracts of employment

with teachers for “ terms of at least five years, but

not more than ten years.” And to protect the salaries

of the teachers, school bus drivers, school lunch

workers, janitors and other school personnel of the

“ private” schools, Section 2 of the same Act18 provides

that such salaries shall not be “ less than or in excess

of any minimum salary schedule or law heretofore

loca l school system . T h e g ra n t ap p lica tion is m ade to such a u th or ity

on a fo r m p rescr ibed b y the S tate B oa rd o f E du cation . T h e g ra n t

m u st he ap p roved b y the lo ca l a u th ority , b u t d isa p p rova l m a y be

appea led th rou gh the L ou isian a cou rts . P aym ents are to be m ade

jo in t ly to paren ts and schools, in a ccord a n ce w ith regu la tion s prescr ibed

b y the State B oard o f E du cation . T h e State B oard o f E d u cation has

gen era l m an agem en t o f the g ra n t fun ds.

T h e h eavy subsidy p r iv a te schools w ou ld rece iv e su g gests the

re levan ce o f Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library of Baltimore City,

4 C ir., 149 F . 2d 212, cert, denied, 326 U .S . 721. In th a t case the

C ou rt held th a t a lib ra ry school, o r ig in a lly p r iv a te , w a s con verted

in to a p u blic in stru m en ta lity u pon rece iv in g a subsidy am ou nting to

90 percen t o f its costs. A lth ou g h oth er fa c to r s w ere in volved , the

C ou rt said th a t since the state h ad sup p lied th e m eans o f econ om ic

ex istence it had supplied th e m eans b y w hich th e school w a s able

to d iscrim in ate . F r in g e b en e fits such as f r e e lu nch es a re n o t analogous

to tu ition gran ts .

'•La. R .S . 17:350.12 .

17La. R .S . 17 :2830 .

18L a . R .S . 17 :2831 .

41

adopted by the legislature to govern the salaries or

wages of any school teachers, school bus drivers,

school lunch workers, janitors or any other school

personnel.” Acts 9 and 10 were enacted as emergency

legislation on the same day Act 2 became law. Act

9 provides for transfer of funds from the Public

Welfare Fund to the Education Expense Grant Fund.

Act 10 provides for allocation of sales tax revenues

to the Education Fund.

Moreover, to make certain that the “ private”

schools are not interfered with by persons who would

accept desegregated education the Legislature

adopted Act 31B and 5* 20 of the Second Extraordinary

Session of 1961. Act 3 provides mandatory jail sen

tences and fines for anyone “ bribing” parents to send

their children to desegregated schools. It rewards in

formers who report such action with the money col

lected in fines. Act 5 provides mandatory jail sen

tences for anyone inducing parents or school employees

to violate state law, that is, by “ attending a school in

violation of any law of this state.” This Act also re

wards the informers. The Legislature at the same

special session, apparently feeling that the St. Helena

Parish School Board as constituted could be trusted

to supervise the “ private” school program but doubt

ful about the East Baton Rouge Parish School Board,

subject to the same desegregation order as St. Helena,

passed Act T1 providing for the packing of the East

1,La. R .S . 14:119.1.

20L a . R .S . 17 :122.1 .

!1La. R .S . 17 :58 .

42

Baton Rouge Parish School Board with appointees of

the Governor.

This analysis of Act 2 and related legislation

makes it clear that when the Legislature integrated

Act 2 with its companion measures, expecially the

“ private” school acts, as part of a single carefully

constructed design, constitutionally the design was

self-defeating. Of necessity, the scheme requires such

extensive state control, financial aid, and active partic

ipation that in operating the program the state

would still be providing public education. The state

might not be doing business at the old stand; but the

state would be participating as the senior, and not

silent, partner in the same sort of business. The con

tinuance of segregation at the state’s 'public-private

schools, therefore, is a violation of the equal protec

tion clause. This would be the case in any parish,

should the schools be closed under Act 2. At St.

Helena the discrimination would be immediate,

obvious, and irreparable. See Appendix A. St. Helena

is a poor parish. Its schools receive 97.1 per cent of

their operating revenues from the state. We draw a

fair inference from the record and facts, of which

we may take judicial notice, that it would take ex

traordinary effort for any accreditable private school