Velde v. National Black Police Association, Inc. Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

April 6, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Velde v. National Black Police Association, Inc. Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1984. 44404604-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9e8a83d9-8a8f-46f0-a401-4d680d84e9f0/velde-v-national-black-police-association-inc-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

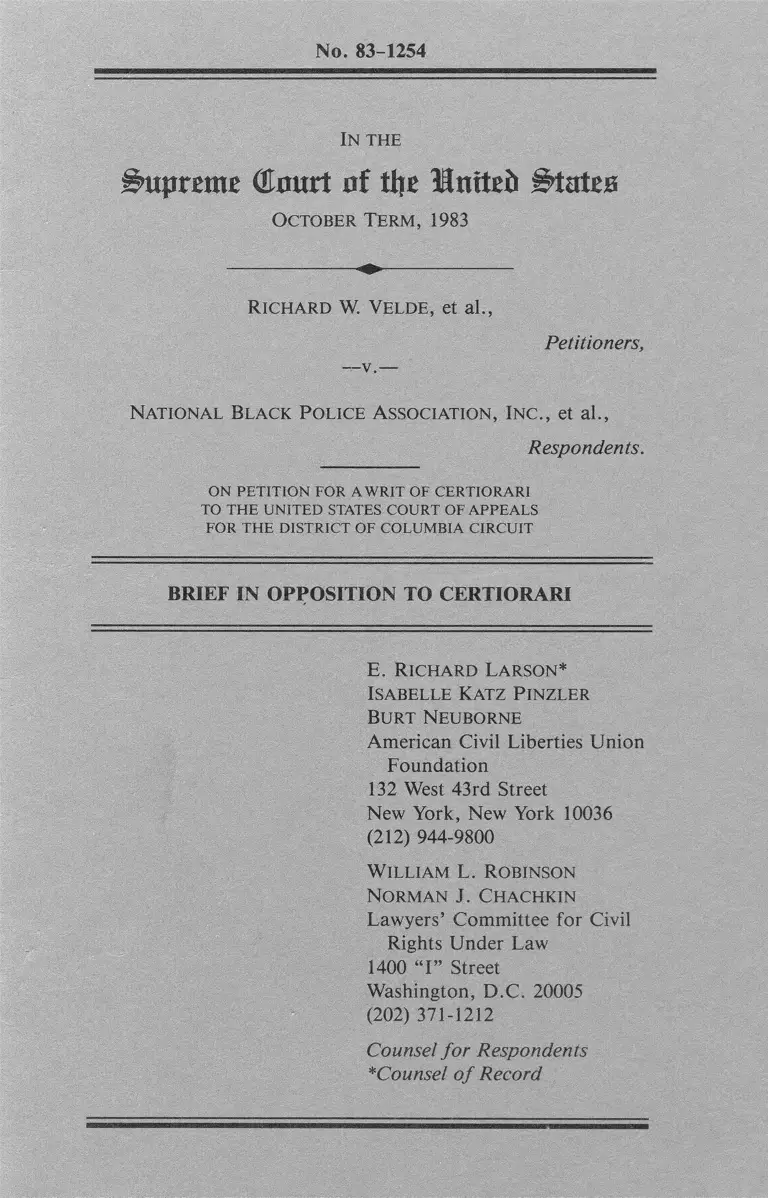

No. 83-1254

In the

Bnpvzmz Court of tljr Mnxtzb ^tatro

October Term , 1983

Richard W. Velde, et aL,

Petitioners,

National Black Police Association, Inc ., et al.,

Respondents.

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

E. Richard Larson*

Isabelle Katz P inzler

Burt Neuborne

American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

(212) 944-9800

William L. Robinson

Norman J. Chachkin

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

1400 “I” Street

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Counsel fo r Respondents

*Counsel o f Record

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

Respondents — the National Black Police

Association and twelve discriminated-against

individuals — alleged in their complaint

that petitioners willfully and maliciously

refused to enforce any of their constitu

tional and statutory civil rights enforcement

obligations, including petitioners' constitu

tional and statutory obligation to terminate

federal grants to state and local police

departments which petitioners knew were

practicing discrimination. The questions

sought to be presented to this Court are:

1. Did respondents state a claim for

relief under the Fifth Amendment by alleging

that petitioners "willingfully and malicious

ly" provided funding to grantees known to be

discriminatory?

2. Are petitioners, who are alleged to

have "willfully and maliciously" provided

funding to grantees known to be dis

1

criminatory, entitled to qualified immunity

from any liability for damages on the ground

that their alleged conduct did not violate

any clearly established constitutional

rights?

3. Are petitioners, who adopted and

followed a policy of never terminating fund

ing to grantees known to be discriminatory,

entitled to absolute immunity on the ground

that they performed discretionary functions

analogous to those of a prosecutor?

4. May respondents seek damages for

petitioners' across-the-board refusal to

carry out their mandatory enforcement

obligations under § 518(c)(2) of the Crime

Control Act, as amended in 1973?

5. Do respondents, who alleged injury

and causation/redressability, have Art. Ill

standing to mantain this lawsuit?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED...... ................. i

STATEMENT. .............. .1

REASONS WHY THE WRIT SHOULD BE DENIED.....3

CONCLUSION........................... 22

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Butz v. Economou, 437 U.S. 478

(1978).................................. ..

Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997

(19 71) , sum_. af f 1 g sub nom

Green v." ConnalTy, '330 "F.

Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. 1971)................ 9

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1

(1958) ............ 8

Duke Power Co. v. Carolina

Environmental Study Group,

438 U.S . 59 (1978)...................... 18

Escambia County v. McMillan,

No. 82-1295 (U.S. March 27,

1984) ..................................... .

Gilmore v. Montgomery, 417

U.S. 5 56 ( 1974 )........

- i i i -

9, 18

Page :

Gomez v, Toledo, 446 U.S.

635 (1980).............................

Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 457

U.S . 800 (1982)... ........ . . .4 , 7 , 8 ,

Norwood v. Harrison, 413

U.S . 455 ( 1973) ........... ......... « *

Velde v. National Black

Police Association, 458

U.S. 591 (1982) ..... ....If 2, 4, 12,

Watt v. Energy Action Edu

cational Foundation, 454

U.S. 151 (1981)........................

. .6

10

18

20

.21

IV

STATEMENT

Most of petitioners' mischaracteriza-

tions of respondents' claims, and of the

prior proceedings in this case, were

addressed when this case was previously

before the Court. See Br. for Resps. at 1-

10 r Velde v. National Black Police Associa

tion, 458 U.S. 591 (1982) (No. 80-1074). A

few additional comments nonetheless are in

order here.

First, respondents nowhere alleged in

their complaint "that petitioners took many

steps to enforce [petitioners'] civil rights

obligations." Cert. Pet. at 7. To the

contrary, respondents repeatedly alleged in

their complaint that petitioners willfully

and maliciously refused to enforce any of

their constitutional and statutory civil

rights enforcement obligations including

their constitutional and statutory obligation

to terminate federal grants to state and

1

local police departments which petitioners

knew were practicing discrimination. J.A.

11-4 5

Second,

duplicated by

investigations

Branch and by

trial court's

discovery in

respondents'

respondents' allegations were

the findings of subsequent

conducted by the Executive

Congress JL/ And, despite the

denial to respondents of all

this case, J.A. 1-3 , 341-45 ,

allegations nevertheless were

1 "J.A." refers to the Joint Appendix filed when

this case was previously before this Court, see Velde

v. National Black Police Ass'n, 458 U.S. 591 (1982)

(No. 80-1074).

2. The congressional findings documenting peti

tioners' blatant disregard of their civil rights

enforcement obligations are summarized in the Br. for

Resps. at 1-10, la-24a, Velde v. National Black Police

Ass’n, 458 U.S. 591 (1982) (No. 80-1074).

Findings issued by the Civil Rights Commission

two months after this lawsuit was filed also closely

paralleled the allegations of the complaint. U. S.

Comm'n on Civil Rights, THE FEDERAL CIVIL RIGHTS

ENFORCEMENT EFFORT — 1974 (Vol. VI, To Extend Federal

Financial Assistance) 271-393, 773-77 (1975). The

Commission's report was filed with the district court

as an exhibit to respondents' motion for preliminary

injunction, and relevant portions of the report were

reprinted in the Appendix filed in the court of

appeals, C.A. App. 481-623.

2

well supported by documents in the record

which had been obtained from petitioners

under the Freedom of Information Act prior to

the filing of .this lawsuit.-^

Finally, although the proceedings in

this case admittedly have been lengthy, the

delay has harmed not petitioners but respon

dents . Moreover, respondents submit that

protraction has been caused by petitioners'

repeated raising of new and alternative,

insubstantial arguments which never were

ruled on by the trial court.

REASONS WHY THE WRIT SHOULD BE DENIED

Several of the questions presented by

petitioners here were presented to this Court

two Terms ago in this case, Velde v. National

3. Many of these FOIA documents were filed by res

pondents in in support of their motion for a preli

minary injunction and writ of mandamus, J.A. 46-233,

and in support of respondents' opposition to peti

tioners' motion to dismiss or for summary judgment,

J.A. 340-494.

- 3 -

Black Police Association, 458 U.S. 591 (1982)

(No. 80-1074) (Powell and Stevens, JJ., not

participating), see Cert. Pet. App. 34a. The

questions did not warrant rulings from this

Court, and the case instead was remanded on

the issue of qualified immunity "for further

consideration in light of Harlow v. Fitzge

rald, 457 U.S. 800 (1982)." Id.

Several of the other questions presented

by petitioners, now as before, were never

ruled on by the trial court and were not

decided by the court of appeals in either its

initial decision or in its remand decision.

Especially in light of this procedural

posture, there are no substantial questions

which merit plenary review.

1. Petitioners seek review of a ques-

tion never addressed by any of the lower

courts in this case: whether the comp 1 a i n t

states a claim under the Fifth Amendment.

- 4

Petitioners argue that respondents never

alleged "that petitioners acted with discri

minatory intent" and that the complaint

accordingly "does not state a claim under the

Constitution." Cert. Pet. at 12.

a. This question was never ad-

dressed by the trial court in this case, nor

was it add ressed by the court of appeals in

either of its two decisions below,. As sum-

marized by the court of appeals in its remand

decision:

The district court has not yet

[respondents'] corn-ruled whether

plaint states a claim upon which

relief can be granted. We did not

address this issue in our first

opinion, and the issue has not been

briefed for us. We therefore do

not view the issue as properly pre

sented for our decision in the

present posture of this case.

Cert. Pet. App. 7a note 27. For the same

reasons, the issue is not now properly pre

sented to this Court.-!/

4. Petitioners' insistence upon seeking review of a

question never decided below belies their purported

[cont'd. on next pg]

5

b. The question also is improper

ly presented as it is premised upon peti

tioners' extensive mischaracterization of the

explicit language of the complaint, which

alleges that petitioners' unconstitutional

actions were "willful and malicious." J.A.

44. The complaint not only contains an

explicit elaboration of the manner in which

petitioners were alleged to have been "acting

unconstitutionally and in excess of their

authority," see J.A. 41-43, but also includes

repeated references to petitioners' knowing

refusals to alter their discriminatory

policies and practices, see, e .g. , J.A. 21-

41. Respondents, through their unavailing

contacts with petitioners, had every reason

to believe that petitioners' unconstitutional

concern about the length of the proceedings in this

case, in which petitioners have succeeded in blocking

all proceedings in the trial court for more than eight

years. "[I]n any event, [the] question [now raised]

should be decided in the first instance by the" courts

below. Escambia County v. McMillian, No. 82-1295,

slip op. at 4 (U.S. March 27, 1984) (per curiam).

- 6

conduct was "willful and malicious, and so

they alleged. J.A. 44. No greater

specificity in pleading is required. Cf ♦

Gomez v. Toledo, 446 U.S. 635 (1980).

2 . Petitioners ask this Court to

review the question which the court of

appeals decided on remand in light of Harlow

v. Fitzgerald, 457 U.S . 800 (1982) : whether

petitioners had "'clearly established' . . .

constitutional duties to terminate federal

funds to local law enforcement agencies

allegedly known to be discriminating unlaw

fully on the basis of race and sex." Cert.

Pet. App. 2a. Based upon a long line of this

Court's decisions dating from 1958, the court

of appeals recognized that "it is a clearly

established principle of constitutional law

that the federal government may not fund

local agencies known to be unconstitutionally

discriminating," Cert. Pet. App. 20a, and

7

held that petitioners accordingly were not

entitled to qualified immunity on summary

judgment under Harlow. Petitioners, who do

not directly dispute that the governing con

stitutional principles had been clearly

established, have presented no substantial

issue here .

a. In Harlow, this Court held

that "government officials performing discre

tionary functions" are not entitled to quali

fied immunity where they are alleged to

violate "clearly established statutory or

constitutional rights of which a reasonable

person would have known." 457 U.S. at 818.

There can be no question here that clearly

established constitutional principles bar

government officials not only from engaging

in direct discrimination but also from

providing government "support" to discrimina-

t ion "through any arrangement, management,

funds or property." Cooper v. Aaron, 358

8

U.S. 1, 19 (1958). As Chief Justice Burger

unequivocally reiterated for the unanimous

Court in Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 ,

467 (1973), a government agency's "constitu

tional obligation requires it to steer clear

. . . of giving significant aid to institu

tions that practice racial or other invidious

discrimination." See also Gilmore v. Mont

gomery , 417 U.S. 556 (1974); Coit v . Green,

404 U.S. 997 (1971), sum, aff'g sub nom Green

v. Connally, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. 1971).

Petitioners, who not only served as law en

forcement officials but also were lawyers, do

not seriously dispute that the foregoing

decisions clearly established petitioners'

constitutional obiigat ions. Cert. Pet. at

17-19. The court of appeals' proper

application of these decisions through the

objective test in Harlow is unassailable /

5. Although petitioners complain that the court of

appeals' decision does not provide adequate guidance

to federal officials who seek to avoid liability,

[cont'd. on next pg]

9

b Qualified immunity is also

unavailable to petitioners as they did not

and cannot meet the threshold Harlow

requirement of exercising "discretionary

functions." 457 U.S. at 818. As the court

of appeals recognized in its first decision

below, in view of petitioners' mandatory

statutory duties under § 518(c)(2) of the

Crime Control Act, 42 U.S.C. § 3766(c)(2)

(Supp. V 1974), see infra at 11-13, peti

tioners had "virtually no discretion under

the relevant statute in deciding whether to

terminate LEAA funding to discriminatory

recipients." Cert. Pet. App. 39a. In fact,

the "mandatory language" of the statute, when

Cert. Pet. at 17-19, we fail to understand how federal

enforcement officials can mistake the meaning of the

court of appeals' decision or of the decisions of this

Court in the context of this case. Petitioners, after

all, were alleged to have willfully and maliciously

provided funding to known discriminators, and peti

tioners' own discriminatory actions were well docu

mented by findings made by Congress and by the U.S.

Commission on Civil Rights, see supra at 2 note 2, as

well as through FOIA materials in the record of this

case, see supra at 3 note 3.

10

read in conjunction with petitioners' "con

stitutional . . . duty not to allow federal

funds to be used in a discriminatory manner

by recipients, takes [petitioners'] civil

rights enforcement duties outside the realm

of discretion." Id. at 40a note 15; see also

id. at 13a-20a. This lack of discretion also

takes petitioners outside of the realm of

qualified immunity under Harlow.

3. Ignoring their nondiscretionary

statutory mandate, petitioners urge this

Court to review yet again whether all of the

petitioners should have been accorded abso

lute immunity based on this Court's allowance

of prosecutorial immunity in Butz v.

Economou, 4 38 U.S. 478, 515 (1978), to those

specific agency officials who enjoy "broad

discretion in deciding whether a [civil

penalty] proceeding should be brought and

what sanctions should be sought." Two Terms

ago in this case, this Court declined to

11

adopt petitioners' identical argument and

thereby declined to disturb the court of

appeals' rejection of that argument. Cert.

Pet. App. 34a. No substantial question is

presented here.

a. The nondiscretionary enforce

ment obligations imposed upon petitioners by

their governing statute, § 518(c)(2) of the

Crime Control Act, precluded petitioners from

claiming prosecutorial immunity. in enacting

§ 518(c)(2), Congress used language quite

different from that in other statutes such as

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and

instead mandated the use of fund termination

proceedings against grantees not in compli

ance with the statute's nondiscrimination

requirements _§/ By specifying that such pro-

6. As the court of appeals explained: "The broad

discretion over enforcement methods provided by Title

VI is in sharp contrast to the mandatory language of

the Crime Control Act." Cert. Pet. App. 13a.

The mandatory language of the Crime Control Act

and the circumstances which compelled Congress to

impose this uniquely stringent mandate are set forth

at considerable length in the court of appeals1 remand

[cont'd. on next pg]

12

ceedings must be brought against grantees

found to be discriminatory, Congress express

ly denied petitioners any "broad discretion

in deciding whether a proceeding should be

brought." 438 U.S. at 515. Petitioners

similarly had no discretion to decide "what

[civil penalty] sanctions should be sought,"

id ., since § 509 of their statute provided

only for the termination of the "federal

payments" which the noncomplying grantees

were not eligible for in the first place. As

the court of appeals succinctly concluded in

direct response to petitioners' argument:

"The purpose of shielding discretionary

prosecutorial decisions from fears of civil

liability has no place where, as here, agency

officials lack discretion." Cert. Pet. App.

39a; see also id. at 13a-20a.

decision, Cert. Pet. App. 13a-20a, and in its initial

decision, id. at 38a-40a. See also Br. for Resps. at

1-10, 16-29, la-24a, Velde v. National Black Police

Ass1n, 458 U.S. 591 (1982) (No. 80-1074).

13

b. The record here also bars

petitioners' claim of prosecutorial immunity

since the record establishes both that peti

tioners denied themselves all discretion and

that they in fact never exercised any prose

cutorial functions. First, and directly

contrary to their statutory mandate requiring

administrative action prior to pursuit of

judicial relief, petitioners strictly adhered

to an administrative regulation interpreted

by petitioner Richard Velde to "require LEAA

to pursue court action and not administrative

action to resolve matters of employment dis

crimination." J . A . 90. Second, in their

pre-Butz affidavits filed in the trial court,

none of the petitioners anywhere claimed to

have any prosecutorial functions much less

either the authority or the responsibility

for refusing to initiate administrative fund

termintion proceedings. J.A. 236-64.

Instead, petitioners uniformly described

themselves only as administrators. Id.

14

Under But 2 they accordingly are entitled to

no more than qualified immunity.

4. Petitioners next ask this Court to

review another question now raised for the

first time in this litigation: "whether

respondents may pursue a personal damages

remedy against petitioners on the basis of

the Crime Control Act alone." Cert. Pet. at

22-23 .

a. Since petitioners never moved

to dismiss respondents' complaint on this

ground, J.A. 234-35, and since this question

accordingly was never addressed by the trial

court or by the court of appeals in either of

its decisions, petitioners in effect seek an

advisory opinion from this Court on a matter

which has never been properly placed in

issue. If petitioners truly desire a ruling

on respondents' statutory cause of action,

petitioners on remand may file an appropriate

motion to dismiss with the trial court. The

15

issue simply is not properly presented here

in the posture of this case. See supra at 5-

6 & note 4.

b. Apart from their request for

review of a question never before raised in

this case, petitioners provide no legal sup

port for their view that respondents lack a

cause of action under the Crime Control

Act. To the contrary, respondents fully

satisfy each of the four criteria in Cort v.

Ash, 422 U.S. 66, 78 ( 1975). Additionally,

since Congress subsequently recognized the

pendency of this lawsuit, approved of such

actions, and preserved the implied right of

7 /action— when it amended § 518(c) of the

Crime Control Act in 1976, respondents' cause

of action is confirmed by the "contemporary

legal context" in which Congress

legislated. Cannon v. University of Chicago,

7. See H.R. Rep. No. 155, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 11,

27 (1976); see also LEAA Hearings Before the Subcomm.

on Crime of the House Comm, on the Judiciary, 94 th

Cong., 2d Sess. 491-516 (1976).

16

441 U.S. 677 , 698-99 (1979) ; see generally

Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith v.

Curran, 456 U.S. 353, 374-88 (1982).

5. Petitioners lastly seek review of

the holding below that respondents have Art.

Ill standing to maintain this action. Con

trary to petitioners' assertion, Cert. Pet.

at 9 note 8, there was no disagrement among

the appellate judges below that the allega

tions in the complaint were sufficient to

establish respondents' standing, Cert. Pet.

App. 2a note 3, 40a note 16, 42a-48a. Addi

tionally, although respondents' standing was

previously at issue before this Court — and

comprised the bulk of oral argument!/ — the

court of appeals' initial decision upholding

respondents' standing was not disturbed by

this Court. Cert. Pet. App. 34a. Peti-

8* See Oral Arg. Trans. 4-8, 18, 26-30, 34-35, 37,

41, 43-44.

17

t ioners advance no persuasive just if ications

for revisiting the question now,

a. As consistently alleged in

this case, respondents were injured by peti

tioners' refusals to carry out their consti

tutional and statutory civil rights obliga

tions and by petitioners' consequent funding

of grantees which were also discriminating

against respondents. See J.A. 18-41. As in

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973), the

alleged violations by petitioners caused the

injuries which respondents assert; and,

similarly, the relief sought by respondents

(injunctive relief and damages) would remedy

and compensate for the injuries caused by

petitioners' transgressions. Respondents

here — in a position no different from that

of the plaintiffs in Norwood and in Gilmore

v. Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556 (1974) — more

than adequately alleged the injury and causa-

tion/redressability necessary to establish

18

their standing. Duke Power Co. v. Carolina

Environmental Study Group, 438 U.S. 59, 72

( 1978) .

b. Even under petitioners' mis

taken view of this case (as one in which

respondents' only injury was caused not by

petitioners' own Norwood violations but

instead solely by the discrimination prac

ticed by petitioners' grantees, Cert. Pet. at

23-25) , respondents have also met the injury

and causation/redressability requirements of

Art. III. As Judge Tamm stated in his

separate opinion when the court of appeals

first considered this case, Cert. Pet. App.

42a-48a, respondents' complaint was adequate

to survive petitioners' motion to dismiss

since respondents had to be allowed discovery

to show that the actual or even threatened

termination of funding to petitioners' dis

criminatory grantees would effect nondis-

criminatory behavior by the grantees.

19

Even

without discovery in this case, not only is

the power of fund termination well docu

mented, see Br. for Resps. at 40-42, Velde v.

National Black Police Association, 458 U.S.

591 (1982) (No. 80-1074), but the actual

existence here of injury and causation/re-

dressabil ity is in fact established in the

record in this case with regard to petitioner

Joel Michelle Schumacher ,-2/ The standing of

9. Respondent Schumacher, who had been denied

employment by the New Orleans Police Department

because she was a female, alleged in the complaint

that she had "been discriminated against by the

[petitioners] through their provision of and refusal

to terminate their LEAA funding to the New Orleans

Police Department, despite the [petitioners'] know

ledge that the Department has discriminatorily denied

employment to [respondent] Schumacher." J.A. 34.

At the time the complaint was filed — in Septem

ber, 1975 — petitioners had never invoked or even

threatened to invoke the mandatory fund termination

proceedings against discriminatory grantees. J.A.

21. Subsequent to the filing of this lawsuit, how

ever , petitioners began to change their posture of

nonenforcement. One such instance, revealed in the

record in this case, establishes respondent Schu

macher's standing under petitioners' own narrow

theory.

Subsequent to the filing of this lawsuit, and

substantially after petitioners had found the New

Orleans Police Department to be illegally engaged in

sex discrimination, petitioner Herbert Rice advised

[cont'd. on next pg]

20

one respondent thus having been affirmatively

established beyond peradventure, respondents'

complaint may not now be dismissed. Watt v.

Energy Action Educational Foundation, 454

U.S. 151, 160 (1981 ) .

the Superintendent of Police that without the imme

diate elimination of the discrimination petitioners

"will be forced to initiate administrative proceedings

to terminate funding to your Department." Within

weeks, the Superintendent of Police responded to

petitioner Rice that the discrimination was being

eliminated solely because of the proposed "cancella

tion of all LEAA fundings to this Department," and in

fact "under duress, namely, the threatened cancella

tion of LEAA fundings to this Department." See

Attachments N.O.-9 and N.O.-IO appended to the State

ment of Reasons and Appendix filed in the district

court in support of Defendants' Motion to Dismiss or

for Summary Judgment.

21

CONCLUSION

No substantial issues warranting further

briefing or oral argument have been raised by-

petitioners. The writ of certiorari should

be denied.

Dated: April 6, 1984

Respectfully submitted,

E. RICHARD LARSON*

ISABELLE KATZ PINZLER

BURT NEUBORNE

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

212/944-9800

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

Lawyers' Committee for Civil

Rights Under Lav/

1400 "I" Street

Washington, D.C. 20005

202/371-1212

Counsel for Respondents

*Counsel of Record

22

RECORD PRESS, INC., 157 Chambers St., N.Y. 10007 (212) 243-5775