Order Approving Amended Desegregation Plan for Neshoba County School District

Public Court Documents

November 24, 1969

15 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Order Approving Amended Desegregation Plan for Neshoba County School District, 1969. ebfc6174-cf67-f011-bec2-6045bdd81421. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9e8caeef-a0d4-4033-a9c6-9806bac8331e/order-approving-amended-desegregation-plan-for-neshoba-county-school-district. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

| | U. S. COURT OF APPEALS

FILED

NOV 2 6 1369

EDWARD W, WADSWORTH

CLERIR

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPZALS FOR THE FI

ONIT3D STATES OF NIERICA, PLAINTIFFS % APPELLANTS

VS Civil Acti or

SL "1396!

NESHOPA COUNTY SCHCCL DISTRICT ET AL APPELLEE

Fifth Circui

Court No.

28030 et al

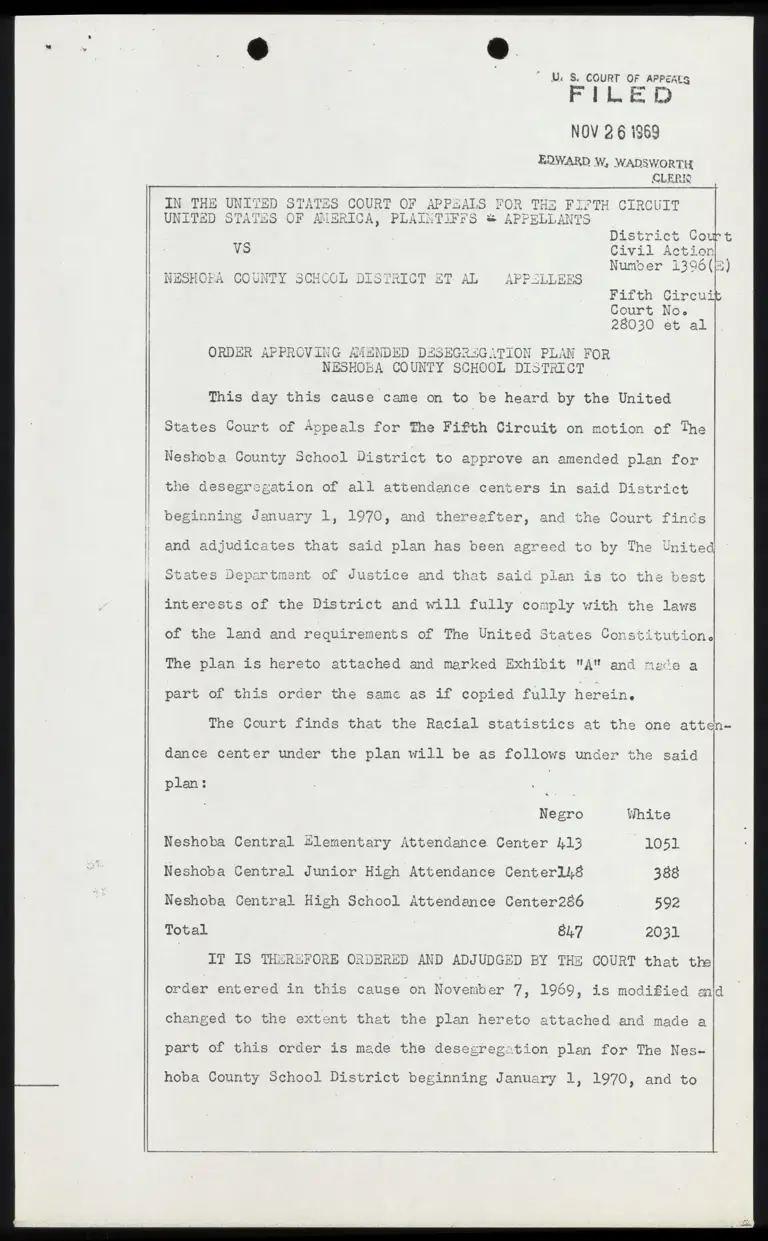

ORDER APPROVING AMZNDED DESEGRAGATION PLAN FOR

VESHOBA COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT

This day this cause came on to be heard by the United

States Court of Appeals for The Fifth Circuit on motion of The

Neshoba County School District to approve an amended plan for

the desegregation of all attendance centers in said District

beginning January 1, 1970, and thereafter, and the Court finds

and adjudicates that said plan has been agreed to by The United

>

States Department of Justice and that said plan is to th

interests of the District and will fully comply with the laws

of the land and requirements of The United States Constitution.

The plan is hereto attached and marked Exhibit "A" and nede a

part of this order the samc as if copied fully herein,

The Court finds that the Racial statistics at the one atter

dance center under the plan will be as follows under the said

plan: : i]

Negro White

Neshoba Central Zlementary Attendance Center A413 1051

Neshoba Central Junior High Attendance Centerlh8 388

Neshoba Central High School Attendance Center286 592

Total 8L7 2031

IT IS THEREFORE ORDERED AND ADJUDGED BY THE COURT that the

order entered in this cause on Novenb er 7, 1969, is modified m

changed to the extent that the plan hereto attached and made a

part of this order is made the desegregation plan for The Nes

hoba County School District beginning January 1, 1970, and to

1d

3

or Gas ’ Pa

remain in force thereafter unless modified or changed by further

order of this Court.

er

«7

ORDERED AND ADJUDGED BY THE COURT on November , 1969.

Judge U. 5. Court]

Moma | pfu

Judge U. =. Yourt of Lily Tor 5th Circuit

Re)

Cg”

on, i SL pe

Uourt of Appeals for 5th Circuit

Ea aaumad

Judge 0. =.

Approved as to form:

Nesh ota County School District

ai fr : ; 7 4 / ZL < / } { ’

B y . : 5 Ar { Vd or A 1 i { p 7 { 7 Na 7

// “Their Attorney

+ JS

3 Q 4 my or i ~ +r A ££ oe

United States Department of. Justice

# / \ ”

/ Vi ral f/f Ne Zz,

} 2 SA ol / / /

By: DLN PL AA 8A ad

py IE

LA CA ‘fC Caf beg

DIY FY TG py

| SPE LO IR)!

ncn 1 ow, ey, AP

— TS IIA oF nl vonad

My Poco nan M 3 p—

Na od a trian fe 2S LON

f1m

PRE |

? on = oy on he loshoba Councy &

hereby subnits an ony my ny

| SESH

ie chain Loa ow ¥ 4

Godt Bu sh va ia Ns? 8h ag Of Truontcos ro te

&o Tn

wad Fl £h & ao

vidos for comple or wns

NE mend mals a

El abd [SAEAPLAL SP PIE 8

n Cale

| FER

9 ON

ase’ [3 Wo

oh

a n

on, 3 vy Pa Fat | &a oT

OZ Sn wd Coit ad Lo bring Noh 4 |

$ ont » ot Ea ap pay

aro not

» &hno

vd noone 9d

- ve Sr ld de Se ww

L]

- 2.2

$74

0 rn on

[Ve TNE SE

acltion

Bai? Ged SRR BE 21 ¢opa

adv Papen TY men fy mT Clengm

olB8I hed Wrisilred bs C30 ad hin

CN 073 phere, (my my

os Cor Wr svsins Sib Vio d thats

1, E

* ay gy Tom mn Ty Cor Segui

ashoba £19) hh

omen ey

Er Covi in g: 51e«06at

iz

os) pn,

21550 Contkor

yoy nde

Cod 5 tashoba Cos

grades 7 « 8 4

Orytenry 1

Rd SAR sx

7, nM

£7 oy

gd wb

Ye)

i ge €

oo > het 2 ETE

Ed ei8inblo by

| PSEA

and enxo

SHAS No Sos tan

pon d mem Sam

100ha County ©

LT a Sone Sapir § 4 CILIA

AJL to WLW) SL 50% Di

a a | < arery ¥

oo St 8 } ir ad wd in

1970, 2nd

pe. 2

ol Diotr

» ~~

artmont ox

y 4 ~™ fl 38 Lad

PAPAS B6 PARSER pe RT

3] On a Ly OW op

J -a

Ey EP 8 yoy

os Nr Conia batina

Ls 3 §

be Ro oe O UALeAry i

oy

uw a a at

®

Co 5 ¢h

ey

wl dak gel

hy Ym pe many

} i Cd oO

I Lelary te

= CG Eid iis rt ob ob

. wma £7 DA AT TN ON ¢

[4 SUL RUE A

Lory &

1

anhst *

LEE

Bs don

Lode Fob | 3s!

Ld ¥ ww -

Rta an

rds 0

ry,

us”

omy Ten ay

asada

follow]

eo fs men

he es 23 | Ry

- 78 £8 a roy

danlsy) waive Wwe

ba Cond

= CAI EE

hd OB haus wie

i Ta hom i A SF. oy Arms TO

pe $id nd ad wa Tire ah i ot ly Sed aE

§F on omy oy Se

HS (NCERR S|

Board of Lrusteos

vod and the Boazd

=

Ed] Io Education ond

Sald plon pres

Pa Ye Ta i | OYOUCT

od wl So ws Ra

Er Aen my gin Rs rm

fs twist bod Wt on of tho

spoon ow oy Oy om

Gd brie oa hed rar on nd

mm?

03 Cc Ca moe

Realms

de 4

“sd pod % 140 80

1 LN 2 ee a Ta ate om

lO at wd wai randatic dad

eet ~

I 1969=70 od

to bk Janay ogi

8 azo oupplicd by tho

Fa es Ve + [PEI EVEN

rds i tH ew ol AC € on: Pa 00

Cow 5b wi Wres da 4d

chi Lal

™a pr lnend gm As

J hn oteic

rod ¢h Tome rere Det " oo IN Din mrad ma, Comm

17% Tra

Ey Gud ud LR RY Re wud p ’ on ” r= »irmn ta ee TC oo! Ea Ye bate tn Le TE a : ; railde dial X nhia P-L L Top 2) on TRIE BRR LE | 3o2 vad Nimes Nak LEP SL Than y F a Tames 8 mM T om bt 7 my omy wy wy oy Pn EY | ™49 frond mts fy fk Pb katate td | = oy Jorn den? +3 7 <2 hn ase we er wan Toad Sw * Qu ios Ra td Bod it Ss einer cu wld dont ik od Diam Gor St ad med ed 0 Kl ss Bar Wl 2 La § Saf Rd an yw wrt 52 rd ite pyle fn os pT ME mdiesd ~ sda ye 1 $5 rem IY Ten gone a Pate Te Cc: on he oA yey dn Swat b ob er ln -a PREgA Slvand Vise La Cvva wd Vt wtas wd Ridntd Ero wa Wr uaiin iud i ra oj SR EY » a ®. Ad A - 3 ay ~~, Pe Ph Je ST 4 5 ry pa ee Li

@ ow rr Py yey on om amy a i 1%, 3 erm ~ Lal Ba Tate Ts © r ated 3 Te foe ey 1m 9

LT TAR CTR | Woalale B11 Lord al BRAN | LER % or! oe a Rr ar do in Cowt gl We eh 5D awn Biot We ca ar ed [+] - » Wer nn oy 2 on 3 - Th TARE ® 9 5. Om 3

oy Any FOL TS gry rs ? go wv CAN py “amg al % gin rea 5 ov wn EVER - ry ™ Lol. al Ah Pal RE VLR ER ort A | od wae Ni hsd br wawd | RD RADI § br 5 Calle

as nicipal Sopazata Sracia ~9 Lohoni Di er Tareas apd - Sev No [oF deni LS RC) A 3 datas wid bd BP Sis win wg

Thora azo caly tuo attondonca contors in Tho Noshoba County

pla)

kK | #5 Ke ~~ *y oa 4 3% o 2 mm HY MES Mn 1 17 ea? FR ASHEN a jn Corvor Dotan Mme

School od Wr ley vse? 82 on 2 TIO “wo ie Felndidebiet] b wal EON ar 28 ns doen 08 gl Pt LT br 22% Ft h my = | SN ME Nhe Cn 4 ren] Ly Vom pope PI LL Ta Leryn 8 a] 1 oy hn a hi Tan lt * Mens)

Sar we § o-oo, «rm wd a rg Vim i Pen oanney EE TERE a $7 BLIGE 19 3 -h LR wo oF dt Qudone £727 Fay ny Tym Ny £72 m2 es ~ 3 PERRY aa te WE Tl La Td ae Ta y Cr a wy <7 7 5 oe Le Fon 3 5 1 Lh > ny oy ¢ 1 1 <3

“RP Bt led Sd wr et en ES PIN + SE 4 LE TURRCBSLD RP SE 0) EAE WAL I basblia S312 Fob wm Segui on FT TEL NED IN, FEEL RAN » wy i) x * - 9 ~

ho te BA neg op Froaan,; (en 3 rg 4 oe HT ~ be a Was EO mie ~ AYALY = & F dan ne sn mm » CR opp

Ia SZ 7 In / iy A & 4 LR FL NEAT WR | or br | Sh 1S [Fein LE RJ 0 Uo Or at mp ot a (4 QL J Jv J) NOR 37

-

bad 1 18 rien yo. a! nds Ty er ms -~ ov 21d 9 i Js IP PEN ic wang on Ey | on ErTn om oon | ru oom oF ervey als

LL PROPRIA aid RATE 1 St A 1 JS RERISR EA PN DN 0 A, RA PRA of ad ee Re an “LI CEA SEEN do reso law wer nad Gd Wp 0a alt ny 3 ry 2 [mn rer} I Bu pmo 7 vm a ny on RT hr wii aop wud | WLSREE LURE. LE SL DENIER UE A A “rb ve

£5 * ey Puen” oy Fa PEP remy pes May ~~ am 7} re oe} Fa La EF ON aie on a om, o n 1 AN an ~ p= | o- Whvad ust decd ee wd Ri er awd ha Br ro a ae Rind % hd PROS J Nobo § Se asp od Wo 2d NF J Cr’ Ts 20d nd Ls we

4

ner & | = en - . ’ " = a on Ly wm ™ O 3 aera Fe a il a War on Yor oy ™

on Cait oe lgh Sd ner wed wd § Ir. i

. 7 \ 3 ta am

» LE Na WER. 3 Sota i [a Es at Wt

~ -

” preg. 8 Eaten PI EE, mm Nm ry FIN ayy Ceo Wo Nana — Baa Lh <n -» " J

Eiomem por pm Cama Las ) ~ 7 a Pate men aT a ye 3 Crlnemea Ba. Shri ria wred Ed hewd wD PPLE a “ry Laka ono BREYER bows Swiawd 833 do Bey PPro pamend, mon gn . a - = 2s 273 2 q

} XH eo ea Sy 5 Ta «= mayo] ™ “ey £3€e F1THTEYM™ eA I £7

tho | IE oF Sal Weld et BE | oe Renan gator Sdeainyg ed No Ca ws ar ib ed £400, oo 0 Coo: A cal on ~ $a P ney I'S) Aq laren] } ££ ded a a LE 21 Wg i

- 3 ~y TM my en Ss PEGI oy : Pat Q Ean) és EEN 2m Qo oop 2 Pa may 4) omy mm en

: Oo le iD g PE Vi | i €or Ey ah 18d: 1? ~~ AEN CO on ul

wal =>Q accguate faglddddios at oghsh a Cont=al A Condon:

£3

nen Pe mem FACT ~ EE —— + J Let WE & ne FRA my re Py oP are Fo Pate £7 Ny on Rye] wm +¢ 0 ry

Cesar Gwe Cn 22.0 ho ne er A = . ul Hie on wii 2 CONG “ad besald atico G oli i ey 1 0 Pe ond € 5 my pana hy IP. wn Se cooz Ed Gin fi 11 ey rade om Fon map ny gy a Da gyn omy 6] ry oan amy Comins Lo Wl » i

Soda ddan dd wo vi ov “yd ie ELE Bi tom] wre Croton Vado &ikakn SEGRE URES Soi 8 ar at ue en: tho orn Cen To 2 en Tey mm No By 2g rE Li la nha ene fT] oy em yy Contam & anid a Lia Te "1

Norn fa, or Wo pr nnn ne Ck PRE LS LEW SR RET 4 | RCE I RAE LR LL DE EA SE Sree Loud EE LE «vd wa Ar a. — 2 A ~~ a » .

a Lana Bf Kitty LIT [al abated or 1 €) 4 La torAn 4 » FW 3 SOD am, my, gy oo 2 » ot am LY om (By ory pp i Vat Late Xo 4 oe

focally 7e — iar LS PERRIER I AA | or ta Sid Cr a pg Ma vO el mM 8d Kalidasa hoi JQ [SUR REN oud yoeneom 1 my on ro on om any aa PE Co: m3 TINE An mr Senta han Co: ferry A Qader YT oy en my ey cont et

a Sa Coan | SE. Heald Pe ad, Wether id Rd 4a FERR LAL To) EEL 2 fi hi 3 LER CREWE II SE TOE i. i Qa a , Y. ¥ es > nig ar eo, »

Bn ie Wa Rat STN, PON ny 1 \ ~) pe » a% PEE Wak PNP if C ony on i) 6 Li ol r-~ a oo Coe Lt A Mr, » poy

ve de FRR 5 ian Tot G2 Be Si er L Ph £5 ML Fn a «JLT 3 Fao VV wv lo ENO wa ny Pp. oy Ta em D None wg om Fy ean fa + {men CYT Ty Tn a ny & © Ym Ty aT “3 | Contra

i bake nee Contos rt wi | AST es Don enrol HQLOCOLGONOD fwcid Ca "at aE Dn oneral F pra p. - —_— s prep

& & . d Fi 4

bil teadanco Conor ond it vould La Lo tho boot intoroots C2 all o2 - 4 Tr ®e mo] men 3 bs | 247 v 2, Vd r sna Br 3 2

the cléicens and strona and sal? that 0ld of ¢ho oohenls Bo em=hina WE BG ws SAE A Wo seed Wd St

»

-~

-

~~ ~ oe Sy py 9 PACE Powe oT an on re, oom yen Tats ar J ham "Taye BP i RIL hd oo a Su LE Ee Loe Ve

ac Ionneisn BLE Wi KN Automdinmmm ad Gea or Page 84 nn it ete) | 2] WI WASRIGE Ei a a

»

- EL]

rove men 2:) q = S39 oy gy mo fH ~~ ety Cones 14 vid gn oom am ee By ala late 2 ETA 28 pvSann Tat

Contos 53 i “ld Ch Corin ® WP rk] ws a PIER <3 La ke ER {os féoront ping ah be, ) a0 Wail) Lr wir vd Kris ia ius $a E+] [30] 3 ea rey C pi ale lal rate i a Es a) niger By Irma Coon Da pm abla $ REN Pav on qoncy ~ 7 JO nm

wad sds it Gs tnd 20d Cp Bi? Sw werd 10 V od wid Nr Fol ag Sag wh No? rl ns ted oi ob br Lp Siri oi SOO & -

a a

o>

Ld

44 yp oy £7 Bara bg Taide Yn 5 AMT FAAS a en 2a nh my en en fy oF £on~ bons 2. Ta NERS remy 9

EO: dd Sd ND Bd Saws ana CHEN | 30 Hele fool ® Ge | Op am RIK i | 4X ning HF iraa Areas “ 9 [9 eae Ty © Pla lr ro. PN Pe ’ — P,

~~ F.2 a

1970. %ho pix Clozorcons Sunt Crroioted and vhi oh havo not boon

-

8. an Be a em Sy IY om CECT Jo PNP Sp em ene Ty os fy one Co Es onan

PUT 22¢C0 use exe at lecheba Contrzal Atgendonco 2ntor.

it would be much less cupsnoive to move tho cyulrnent Seon Ccorge Foo mh Sad a ib Vashing a x bony Carvoar DCalr men. Tey on gv ey Cont rye hon thn gu Ams rom ITnnh (28

Eda Wo i 0 0 Gs Seren AO

Wane reveiw We Tre Ss Cod © wn ag

mx en £3 0 my ne » yom oy 7 oe a Ro gi ENS Erna NS - h hy : 3 Pr won a K | on

Central hicendanca 2RCCTe AiLD, high cohoo! caulpnont 8 oro - ” & o . 1

Gd » A pp 3 TI ad 9? 1 | oh amon any Y ©, £07 ty F 4% 9 prey da dd oe gro pm enim tt

difficult ¢o ovo, Thoro will Bo rood loos complication ia moving the od

= - »

52 8 ea amy £0 OEeThou gy ", 4 On ey Die 30. Va om ¢ - a Ps £28 ~yinay a mary chy 1 aa

1 ¥ 4 ~~ " TH V £ £ #2 $ a

Lip neairo —— Vaews S300 FARE. LL -cntoz H4 wd en nae Fe acnl Ce SL i Lovaas ne, ong £ br vo na Conten 9 ne] dg: A | Sp Pr : wh | Fol my rey ov ity ¢ * ENED By hy

20D antral on Sg lonon ating 8 goo cduoation pPoCgrem TY = ro oon 73 Tray Catnen 4 - E « Tener &a dl WY; 6 Us | 2 hecie 3. ot Eo BR a Wa hid

Lien Sd fu ndedwnld IY Rodd nad ihe] — wil EVA 000) 0 BA EN QO L103 SPIN 4

by

Ly ¢hao

»

gre Lm on fe

ts 0 Chnnd

£9 00 1

tos ain

Tri

should 05 roatgicd, changed, ons Si en

OnLy cne sehoeol in the lioshoba Count oy

Ino: tv £2 i nda Aad

a

o™ # on, F . rae Balu Echeol Dlstzlct, ong lu

re - : : -

Chic vill bo in otic

5

J oie ., a. ..1

&

a i

7 OZ

on, om, fy bia | Def, S~ Tal

be +b ort ae

~~ bs

Ox

5 ny

oy

ade To Lf 4 © oy

Co tw i pr i Ti

tho al

A Gr we oe i

9 fn

nr Com

7

12,0 oy 8 £73

a on ~~ dom] C7 No on yom 2 00 rie, rg rm ny ; \ 3 { Toman of fy Cony *u £3 Pe sn

Nal on db BE a vse s Su. vive Si is “y bards bd Glia eui ots a Sot ara Co Lp ra dg re

asl MT en 2 om mm oy ea Lanes nem £0 nen men fl 3 fe tT Pe Ta Pa et fry Clo myn meen pity (Ya oncom evs my pry

Les ow J ENE EE BTL WLU {3 JL NCL RAS DRA TE Sa A Fr | LSS a Le Se ot rr 0 a ve

oo or a ~~ 9 ey - - a tra so El ~.. ern rm, Py - oy » ey eT et} €or my QT aa tia Pot TS ? rn Ay a LY Wa tf ££ ~

or Vo we nu ae 4 ru al ator wild i rt Sai? it Wl Gent Tas ue iB “ws Ns ie L SREY Rn lh ab ab Sam fla [I he aed bud er rd IN , %94Y

« . & pe EES 2 ¥

~~ LE Ad Sr an aa ated ob Bae a Bs Te St 0% 4 93 &57 Go, po, La Bot | 5 pI -~ NO oy A ben EDTRNE(T] TY

tic 2 pik ON fononoTs J en Lil ar Vind Ca A wp eatin ah Ss danas? Srv bp Candia Aid Danis

o « PS ty oy b> SEN fi] a ( ors oy Ca tha cdl £0 a, tomy will bo available at loss cost to the citizons,

-

Es £7 omy om

8 ise ur

#1

ad Wma

- A Tag loohodh ey

Eman oe tented {} ey: | a 2 3 S91] rom already octated thalz poo

be Bone LIE J 22 —— am} Tomy <o 2 a Fi 1 a

hat a Wis @ er en iind | Co nd Tw? [Se >

01 Dist

cn to thn C

ig raed pate sTaem dd oe Sronanreds gum

wid Ga Se? ub Choir Sone Lidad Co'aw ww

thoy éo no

to chongo

nd a hovo

Lad 4

i gy

Wl

Aa Tat »

3 4

Se

wt Cee

4 La Dk Fe Tt] my pon (Fe

Go Kt erm rt er Bed as wd

£5 Ja

» EE wy a A an,

{War wens wt

-

a? pe

-

, PO.

a i

~~

we de wr ws O

”\

AL

20,

me

ht rs gl wor

©>% fill

id Go hit WF

Ol ag

Nair ww

oN

Bo) Gib vd

d ba

- =m Tom gy

| Se a

»

3

Cy OF

: » Ta 2 hn

” Lal oo Rony et Ta Ta Tl mo £7 mbm Sy em ny Pa em i pee FEIT A | 1 | Pg | “191 OQ Oo aS Shan

fw Ge Cd a lar wr ia i wo Rl re Soe smi Su? x - this TRIS, Wend Wd le oe 5:3 Calor Spt Gand oad ch

oy pre PoTym®s Ty Germ Pe ET L ~~ of #1 ny a pomyniy am ox on, "oY Pen | roll 1:9 er Ta rnen®)

wr nid ue Cio os oid WB | SEA PARR LITRE TLR WLAN Liana £0 of sp of em od wd rip a a & S—_— Bed 2 wef Span

9 Nees Pt ty ano sy Taenrinlenm FiPymbs Salvo ? pres gna floenmmd] Sumy 2a - Count: my

es XE ef No “sD ek TLS LN 44 & nu RY REP 3 Bt be tw Sl 4 i 0 BX ET A ER. [ FHA Ri os? iain ih Cs [our as

» wy i at] - # © MAT ed A a) EE BL a NN men LE rae Lt A q I I La Te Tae Toa Bi Pr

foi hr es wud Wr OD iJli.d Shas elrtst 3 BRCRY PS. wi aA «> 5 207 Oy wd UF. Gail a ei Pad i Ney LS

eu "a Fas ons) 8 Tn ay Ps Sa T= 3 2 3 PNT A ¢ Pa Pe By fn ~~ & Fs a a Pu mite Capa $a oy omy 3 & Py om £7 my ey

Sot Kd Star ed LW ee W | ERP 9 Kn yah wid Sch dein | wit bod mB en ih on | SUS pp | Ear uh Nd Ni kt us Sis wes Nr wed Burin us ~

Toma £430 my fPanene ny ey ~ Ca aa “3 Town Mais mong pm om oreo ~ ~~9% & Tm rd Cad enon AY

yr | SP LT Mh 3 5 4 ¥ a Cor obs NY eh € Ded | Se Sv oa Sain Fad Sort cand wb Vv

un Sas men “em oy on ~ ee] gym 9 Wer em pri

som Yt wet TF WL RL or” oa ds th Cn Sr = ed Na oD Sone Coe v

Pa y Ear b+ i Fo — "Yon, Peay omy o 3 Fa > ££ on

“bo ad Se TE EE Ri” ft Nov was was bad | IY Citterio

on — - oon SPR SE g ~ 2 Pe . y =n} wd Tk TE RA a TI a be TE |

Ciews ” wt or wd erred WG Gn | PEEPLCIR LSI. Nae Cb Nd as LAA SPL 2 Nd vt vd min ud we

&& em rT" ‘a } @ TiN fhe ET en ememan ty nT 10) yf Oy oY CIs 173 of » Puy my H ry Pare »4] Pte | - re ary

des Vad bidder CLI vad ut Baa Nr Fd er ch Mra d macd died But ad nd Nad pet Ss ead ad ans bd run PA

meen on orn By Bn A a Cagmsns om wy oy Pag A nem G3 oh ve Sy 3 ons i O yey ete nn] Cla mey pliiand CP nd Ue Tt Ne? i [" | RE Ca wd St vt wp BALE 4 2 | oa igi: dnd Nd a? vd No LD | SEOTAN PLY TE Se CN > -

ate ik Suites PERS | ond | N £20 5 r 2) “1 ~ em In ny A Ay TR £7 my Erman po ta oy omy FANG a Pare tra

LO a EN hint ab nas REE IE wwe Vn AQ eid Beis bad err od Bes ws ower nu Brn

2334 ee = 9 & sre ) 3 WYO a £0 rr mm pam poy pm 2 & “) wo wm Tk Tate 73 ST De La Toy yoy ~ A mend <a ola Tt Sar? ag ud nh a oa cic ad Se Sa nt Nr Ch Scand Lo tas fad Roe Rie oi? unt Nl Laon a Bunn oJ aad

E tho Cid ermn 4 ¢" 13 3 ead bed | LW biti Cdn oa onde majonily

Neat Sod pd Gand Namo oh D5 LEMPIRA ona ~ / IPA mas bd a Row ges ti §2

Da 1 4 > 7 1 5 ~ ih mats » oa k] Ciidnonn mn Fale] \ D or Se Xs os C ~ 1Etea od ErTy my f tin t $! ™ 403

i NPs 1d rin or i Sn Yr Wt p+ iad a Pid ad 7 a i ot ser lh nd LW BRERTE. Pic FY SRC Ke it “Lo g | SRSPVERRR VF) En wdbd Taam Sn “a

omen f Shit a Te LT tn aT ~~ om, on gran Tm ny ys ye “a on 7 Tame «> ry g : 2 SURG 1) » ~~ 1 £70 ET my

a id bo esa ~ | EAR | WEPOPETE SEE WW DISORINEY Fy WR TPL | LS { Fm ie grit 2p D WEEN STR TO § TPR G # Nf hd Gnd Teed ei

-y = - a oy E

SL ae TI FE & Phy Srrmem Doom mam Ay ee, Tas ail. 1 EINane

F od

| ERI PERL SE pe D SERV SE Daria’ or 7 thiu Cid Cts EP

.

3,

PRESENT

CCMPOSITE BUILDING INF

TEL LES ol oa

bed U'lie UH

FrONCTTY

PS omen fom tym

Powis

] ) Dn ai fF lad a Tait)

LRA EE EE a

a

Pleo Ly o

oad be Wd Ga

Cooreco tien tn?

baanibs © Lad borree ad J bo od

ToT, TUTAL

ORATION FC

hESuioa co C1i00L DISTRICT

f

a

d

a

E

T

—

er

gy

51

Sy a Ba dali say nT 8» stm tad dB tond fools prem ny

sy § : 3 }

SS ITO WEE A 39 Vealwaiid bid Nos wad raed Seanad

EIT A ren gh iin Ef #0 ty 4% ainda a PRR Ore? dh fat alle debe ——— anliadte Bade b A Lhe. Sk. § Lifahabsd 3 hati Fh

h eo “0 2 « ri)

+4 Viciciss B&W Giada v bokod” CF th i Pet Lodald te vivid Sane w bars ah sr surat Los walef tind ° 155 PJ

2 Rah og woe @ on nom Tan S.A get ay sy Mo an poy Qprn Tom ‘ EP ON “ County ¢ ££ nonnd P* eo Poan® mh

Libolae 8 07, ew had BN lit mhrmtinand Gael Batti d PENS i “o ts iv 4 iii Br Hrd Ble

1]

3

ok

{

-

;

‘

"e y a w

8

! - , fromm em mT ty H i

4 bi Flaw oF Cntr? . IP omen 23m 00 bt rosbout en b

i - TN ret tr ¢ Gvassasin ¥ ed Gatesie TN my meen, . Jo { te Ld seer 7 ton Bs em

| Fu eis? Lie CV “Gl dé 0 Wd i ¥ Loh sinismns Good

|

=

" > ®

Fi f 2 |

{

FH]

S41 ¢

EF] : -y » 3 © Ne 4 oh Sem g.. e Eabet. ~ sa § ~, Me §

L [TRY SN AN Contral EY oq sn, 2 Ra my wo 2.5 ry j 1870 Lenk " § van 3 CO

b BV wd be end 2d Lo Ub hreaaes bd oben iY Pat ot ul i [ FRIORA eo heen § ad $

: ¢ ¥ ¥ v

y i § i

=n f= po i J td - f me

PS RO rs T=} Th J OP RA 4 yd ren i Wg LF SR 5 i 17

il bev wismwin Gaius Lie ksuwes 1 ¢ Fd ald “wt wha} i WP

£1 ‘ 3 { Sy 5 I § EK ial ili H

L 4 ; 1 =~ . } CMA Be) 3 3

tata Prmband Hat Cohont a.32. } onl en | eppelacsi rosiens 725 |

Piswdidvi/ud Wwodwi le Bev ed sendin bt oh 3 8 i of id H wu § Wa om } Ca 4% ho & LI $f i Pi J i

¥ ¥ {

: : / X —C——— “vr as 3

i ! } ) { |

tn { onan | amma lonog Frngd enon i 37 ig

i Pi iad | JE YRS FRY ew FOGeL: Ged 1 end { “3d Ate

i 4 § } i ¢ 3

i

¢

;

Te om on Lom on apts bi AP -

% ! 3 :

wed B Nid Wao © hain deni ¥ livid

C

E

R

T

.

P

R

S

i i

i

TE Ay AS em FTES AY gh pic EO ene HOS my ™ rs ne haa my Cased. ba i

Bi mt ad 58 i gn at at ba wake dO

. & Foe ut Ny Vol wr Beka dd We wey a

on wv oat, my Ba yo, =e}

Fh $7 Cm on my rm ty

€: Trey # 1 APN yon 0) a li Fae oe " { J!

- band Badu “3 BF oi Ra ok mem sv? fa ie peg Wie a lpf am Td ah foe ad Lg He x | | ? 20 Guns Yat? Kis Sue 5p

h | yy Noma on A oo Pas .. Mh Tr Sy Bn, a di on BR asm Ese wan i™ ¢ 3 rm ey

©5 RS i OA ver as od 0 CE FTP 1 Sd os | Ere nnd Yn

re) - ~

DE em > yey Se 3 ai Py ge oy rn arid EE JH CRN g SF net aT ALT I Sa- 3 S J La . - oF Kd wo oe Pp Mit Sl LE ) .

- . “ " .

HO en avin, JY gs ein, 5h wip Dy ge oe i wy sof oy rsamannn By gy dng Wh ar Cty aed et Sugar arth Can nd Na a sup Yd Fh mdaa

ey a "aed

T - » We bed ~~ ».

3 a no 3 ori Pa vem} ~ 9 rm Arey oy oy 4) 1 = Pay pM 1 2 we 3 rnd apn Ca¥ el By oy a h WORTH: Be No Gt we at 2 mm Ee plea wens Sa Rd Sn ah ERE PRR EAR Crm 05 0 Rew

y ETL IN | & a [0p MT TE at rh ra a a I a J [99 RN fy wy Pen Taso EL ee °° an nig ral rl Ge af Be ! ; ir ed eg slate wiorsd tend Bras Sota? Gad Ted Bi rt wen il x Ns oh

"

£73, wy 1 sani, oy On Fo ren, ny, hb gies Va OF ees? . A =~ F a Re bo £51 {is & +a te 1H a Me on, 4

Wow Sr aod wpe Bod prin sit ol Sd wg 58 fo 2 PES ad Bad eed a? lke ag awa Lov 3 wm 3 nt Sone bBo Bod cod pF gp ENT Ta, . ty ok 2 he ke Dey an Ay pi Fry a 1 cs NY Bh, py BD ox wy a wy | A 3 3 a No omy Sam om go, Teg — a 4 Cid Mad en Rn wp Sr Bd ds Bodine we * PORE SE FE pores J wl BH ny J ee a Qe ¥ wr od Sp nP | a Lore at Re it Noa PA £425 £5 fri pre 8 re 0 eat - i a Cer facts per ab So Sl 8 Kom ot yun 7 - ve 2s Ww 3 Bp v tad i? a

-

‘ r. " “nN

a aii hd

RR IG GOO preety reed oe vom, dn Svan Fy gutter Rnsdavgd Hg mss aed Sones i i ws db Rd anes Bn Sod gi ya ws Nortouus nd ER Pe - - ~ rem ne my om Py J pny Yo Se RE Le TE an TLS Bape Ng ~~ Cr ear dT dW Set eR Bom pet . At ne a uh Sed Mw wp Li pe Be ve Behe gad 3 - Pe

- - - ' Zn £57 ~ “A. Sy mmr) pny et ges Be ig = Ny a Toe remy & 5 0 A ac 4 of on

RRL RW RR N.Y EER RRA Aas. | EPS Sa le AR EL EE So £2 wd buf «ow wad Te ir es yo Prt IlE mer py prim ETE | wt rt

PE Rwy whe We? £3 HE a wad Bop aa A

oF

5.3 Po . - . pom oy me, -— \ pov gy ren ray germ gm em eyo ta , 0 Rt i Nat ni + SS ® . ¢ (8 oe an ° wd

oy

P= J Fi A erm CE Cay ” 3 FON 1 gow, Tan ry sis -

=

%., ne’ Tvs ot Nak LRT H - 5 8 IR i TR ad rend Tol

. i

“ \ ; . oy n Woy : p + 4 '

reap Yn : Lo Ww oy ¥ WEE Tu =A ¢ # TS Rt tos FA nga. — a FE ber ON a iS - wd igi . . - 3 « 3 a

r . -

? v ~ yw fre - ¥ L]

or TW J Ry, SE # in YF BE ” wed femeaed SA Hd NF vk gut id Voto on 0 se it SB v

TE 3 i - a

aT Y Be -~ vem pney Pa 0 ale > ery ey ones] anid ony oo ip ay my Pa or ~ i ors, inn Sg my ayn, % " or Toe i wn Soros Soe Bip at ut” o LS EE al TEE Bor we wash @ SE ES < ~ : TET 9 » FIN amy £1 fy wy wy £romy \ Prey gg ey Ty FE) arene gr “2% gon, em Mg JY sey 9 haan cl I | aS aro » Suet GE An Cra ted GF

»

: =

) CRT BP mp - Bry Dap Foon py ET gy fey on sone Bo wh mn o 3 “QD LE Cs Be a oh Gd wd Gs fr £3 Fr eo Rus aad a | SOR USP - n TaN Tat Te Le 0 po ori pom ERE 3 Tn JP Sp 115, FW LP “tng - mesg mod 29 5 MEA o dei ; rs ow rd wa 5 Ud Sr uit BM 20 CaN ai Retire 4 * ” ~ - » x Pp 2 pom ang ©) PEE Fides Wa -, Ws PSN eo 1 } bi | pn aT TE I dry £9 Ll Bia Li. pdf Und Woe Yor KW Ni dee cs tg § SF LT Edd {3 WMC Revs BP Fein 5 -

o£ J . A

Se a RY Foe pm rr} eo on mn Dy YP

a ot om Nn, porn omy ry Trey A Fe LT Cr wr dred BI Wh pion Re Wad A PIPL Cr wd 2p Rus view at FE So fe {: TAVISINEE SWE SET TI | 5 PEN Rd Jey DR. on FL sy ue | PE 3 FA On Sem I, ey ay ave bien a NB py “on weg fY oy pe &

Ue hr Vrrravwadhovend Sued Cael v aed £0 APY SE (SRV SE ND SP CH 5 OD IRR SUN Sati hi Botmey, ap am™ pa

Pa Si J Fo io TE Lire Toit 3 Te LE ETE Ue Se

Gt Rr gud bu 2 A ne iia wd RV OF EE IY 2 Voi wir Sow 5d

RE 3

oa SN : avy wg

Te - Dr LN SE - - a 4 wr rely C3 pny A poy won oy RO Po

5 Se ah AE wad re ai ot Sod tnemran sd

Eo ES

Boos ad - 5 mg u Ra Tr TE a Ta 23 1 Ren} 2aerine mama > Frm nn ae epee 5 em ny om Py son, £72 [A TE Gian an Tae #% EY my ee

ovr Bud wetitie wed bent Ne Ws narod Girt Wien eid $2 Crag B2 DEERE SA, Co EW ho rad pd

a v pr eo Ta Een, on Th Tum am may Ta a ears Tn an By 2 & Bote Dorn wa} 4 em Bd Ya Set op ad Cv or RR Nd ed 3 LR iA bd Coron G3 ai AF tot in ns

~ ~

-

a a Tae na go nny £5 pom cy Pa By on 1 [ed nny co, ~p PL To 2] 3 be, vig A el £ EL ta Sad o We Wd Yak GD Nr il Tend Ne 4 Bet tp ta To Bn deri Ng a SOR TENS Soar ep isk Sil a SR a ¢ EE ET a - nay From won ne Pen a, Fs BF HA F pd 1 - 1 FS ” i Tae Lat pr ng ey 3 Ta bt a ££ on it hi] pro | Or ™ HA Sow pon iy pe Mg Par

Cord oo rasan Soe van w Grima ed Hod LA SLSR PRE ST J Hi $s) Kida Rl Sore eee 7 Lad Fd o

pi

nsf Pray frog PA Sado

" Vs fr iba “wad fd br ¥

?

Tren ® —~ LA | Pram ony ~ 0 wg pm Fy a PR \ Vr |

A

Te

® teria Chsnwed C3 atime ar han, wad Gedo

+

Fr Comm wm

hin RR NR Ta fans uw dnb - us? wn

oe

-~n a ave enn am, ny By FN EA IG ey ty pen om i ev cc? pe Ny 6] ronan “emp FT SA &s E Per Y.v Rn et Nat lv Se [8 wo vat ad 3 Ror bed it Rp aha 0d = eee A ET VL NE | wl wi | ESET ~ . h =

ry ly -

a

2 oe ®g Yarn uy Pam E-Bay) prem rT oth | a8 3 3 Tomy 13 poem d FN em wy Pi Y sms co Fy om, whi Rd] Wand BIC Bla od Reni way ap Ses Pg in Wd CEA RS = 3 is A ar BB Hh fabio 5 ® 2 a v 2 30 ay "2 Phy pm 3 = Sam TT $e Tim g) a3 €7 awn nm at, 4% bs ) ad ro rn, am oa Ay ot Er Pe Tt ad Gd Yd Si hia a i Ci Vr rk Bl os SH rd io wf wi bad Saad LET Cll arr Fd odd Cy 7 hse wn Bad 0 me ick a - 's od .

| rath DJ | 7 il 373 Ti PO | 3 pete Romy t my 202d MY mn Tea fT aes ¥y PILL I Cr oo Nab en 0 nd wa deb Bu a Bw Ss © ae” Ne wed AML angi lore IY BES Ci i ERR, ETLAT RT RE I TR LW,

- . even rman} nan En ye yao amen gy Ti gem hoy X om in Bn hon Of oh ge 3o0nn on, ova rv Sy wor om mn BT Br Cor Lr ie Te Gs FRET EE ORE FLW SE OR. L SLT IR RRA RAS. = F Wind ir ie Pot a at fh edd un pe tn ed |] ”- Coe RTs Lf FN rem oy pr apa | ve 3 2 TN hs TNPONGE. J oe a 4 n Hac Se np. |

i my ; & Te y 3 Fe : rs | © 3 2 oN oy [3 's

Mor i ia Sk i mat As ind Oo Cla WE Nu Ty Gd a Sr ud ®t 2d i Eis oh SH b3 Sk Hrd Cave, ahiatls Fal ga Wi iw £5 Wve em x nd §

-

eh Ty 14 porn) on fm pn “3 Pedy TN ma a 3 Cc “5 wn A a 3 : £ ld Bo dire i Sa? Boh vi iD (OWE SR LN 2A A tO ds”

Erm ner 12499 Onn ay Oy ess

< Tan

Rn od

on

Rp

et yb Neg

roy

hed’ |

7

Cebus

Da Te JL

3 oo UPR WY SI ny 4 ) Frey ene om

" . wis 2; a a 9 ¢ omen SN emay en a ol 3 | SHOR | SE

! i 9 J % -

PI EE PR JE LT REE ta dala - hm (18m) pein wae pty siren mom A ING GA Ping £0m ng Wier Bd Seud dl EE TSR TP LN I A Ss

oh id Ft gh td 38 Sed anid Suh 2 Saf id eh uth Pa » ET om alla Xa ee Ta -

e~ oe ~ ay of pe roy ”

Ys | SOUP TE RAS ER ; & nine 5

| ¥ or I hdnr pw end Lo

-

2 SE 5 on ery lk po inie n, ~~ y . 4 FT -~ orn . os, Ny I Tan q 2 a ra Bt i SP “tN oy

Bn Tow at? if cs on wr Sonal Lia dw a h TN % - WES pa 20 ALE RIE fo 0 wr wt § 7d Cnt VY pt ud 4 hd 2

J

,.

ae

c - ~ »~ » » # ) . a »

men £0) | Sa Pl te TI EAE: PP Y The € gv EEE Tul TRE SN Np 3 a grrom Ton eR oy a By

| EN LR Reet 4 - |S TREN ae i Rt 4 J

suid Qa vaiasvd hod Cott far LA > wr ut UP

elm i - -~ > - . a id RP 3 on ¥ 2) a -

OZ Grndas olhon A 22 WALCh Bo Eo ontllled on Coz hich h

-l oP ee wa wg a [PE Bw a a ds ws Ea wt ont Veil dvd | 0 MY [RN # he da ar LER

pe

"aw

~ hr rent my gy > mom 8 A - 3 "a Sacha: 2 § yoga] om ~~ T.Ti LY £] = STD I, 0) SW a ny eo Te crorront * ace Soe | A ene

3 ba bat SAP FES Seats wauin ne = et op dm Na we Wail Th ee Gad aed Ys XX 7 ah od Wr i BR 5 WELK A Ie [: } 2 ~ »_® ’ a Tae ter Fa} fo ea pg om Pi — no » ON 4 In goRnSIa } ond Qonondll J TZ2A vRg

A L ei i wd i a -

ry rv men 4 ry a : men £3 fic:

ss $0 Nov as 2p wat ic wr & ih ws <

© Saha

~~ Lo < » 2b omy ™ ™ Aen Ha Lan FoR WN oA ”~ ay Fa Fol ¥e «a 23 © land 1 | SI ACHR VRS EE ES RAL pre iid p

nl ss cpg,

, - : . - PR | ’ 3» } re Pat: he Ney 5 » ;

3 3 ast Lo LOT SEE A ®

i on rt Bw on lI i 4

hon on guy ve Foy ®

it

«a

8d

“a Wiser a we

0%

am Eu

3 wl

hd

SNe £5

Of bd vr

fa ~y a of »

cose ada! JounE F 20

*

SPN

ma ta

» 7

GPE Sep inal pan : RTI,

J LF JP SR } wd LE, Civ Cri and Hoa snd Nr fF

gm SPT on ios

A Ld od rade -n oy

£. ee 2 YR 5 aw

Fa EW

a JE = Se

3 > 4

ok 4 oie fur fd Fh) LEIS,

o

ener

WEES 5)

dh et

connali

ww MEPL gu

3 TINY

Wi dot ak wv Se few Lf

- a.

Nn : » ya wn Tals

eta Ra 5 $i rend Nad

Faint i Fe PH

Yn of dra NP

FS ERT at ha The

G

»

) 1%; y -Ouvvy §

A ad RF Wg Rusu? hire Bd WEE wr oF

od 2% poi ss Tate)

= g. A

Pa a Ba Te hia ah Tk J a ah

Vit wr rd ad WS /

ay

© 4 od

* LL

2 8 Eres

St

» 0] 3 Cro ey ey Aw 4 3 ey 2.8

OF Rs Vds sate ©

my ry , oy

Ld #

2

€

Lo

win pa

’

hb

rh

om

0

Er

¥

*y Vato lis bila:

0 Cl

Pa as | v ak

ER 14 3

LLCO)

LR * RINE:

ig in

<r I

Fn my

. A

3 rl a os SN [7 ERE SN

" ad

|

2 + wh a

-

. <3 3

#4

3d

* 4

tad to

TT ~°

“nd aye %, bi £ 4

© ed

18ND

Le ad O

€

PS ave Pe

- - Yr

mo HSCS AYRE EE EIR

N < poy Bo am

tt Ws

Pes Bah |

3% c2 hg! at wo §

Ye Pata hat

rk Sel Yd wid Wf A

3 4d H & - Loo ny »

3 #1 ih Balai Bis Li 3 A

«A= D 5 ied

AAS Gi NA Gd de nO es 4

" Ls >

vi - oo . - POE LET 4 Yd ar Ws

4 J ; : » SP at, wm

saad ¥ ha ~ = - Lad >

" Yous

£2

EAR GEARY]

Pa oy 1 on

hw

NY SR

Be I 8

y Bd

a ns

LS } 9

pre ng om, ¥

Vand

3 % 13 y 5 die

=u wd v2icte

wing rn

L ] oo boi

ey

sed sion & ate ui

Wed <3 GH a a

alelaxsiele

and Td Sard ih

x way £300) AY

EA SR

Pa Tata sou of} oy

WE LS EP

ee Pe 3 3

Bo’ pe a alt 5H

*

Coed

. 2% py yy

a

baie. BV p: - -~

204 1

Hora

Wd Ad bes wf

an py 297

Sih WP a Vo Le]

GIA

sont LO

vr id

CLI ? wd

-

2 no ET pe wey . - ¥. . Cs 2 - ir . 2 ay do wing iy nog 2 PN WRT | X ! L® LPR DE 1 Lr 4 } 3 1 ; . 1 | is [ {imm 3 ay mop ow Aa of £77 A Bo ; ’ 2a L & wl . LY SL 4 y oo 3 wt a » wd Stel LL

ot wt

Gu 1 & a, | 7 ” a J F " jt y pr Lion By deoogrogavion plons lorgoly Acnonde Ln

h 4

Lod ; oF 4 1 cx cad £0 4d i oivh 4 on Cor wif i yon vi dal .l Pon Imag 3 1505

: Crh la uf “ran y w 3 FRR LEW roy no py Sm oon . | smear er 1nd min She » avy 2x rn £3 Nd on Rad Si oF 3 snihlias WALES Vous vil C0 Veo PNR |

3 13s id Fo J INAS Tv ey i . ~ Nd ~ +3 harry oe 2 2" 1 oF a £9 3 3 £olloul et BLO 1H: 0208 $d i local © 10in 3 LH fu Ea LOG or SN i of Cd walle dln Se sas fod a 4

~ oy cts Fm, wan on,

£1 SAH Ra |

£2 oy tren mun A sh

L 30 8 1.1, 45

CBD ic arimibeitinsiod res S2

3

Lod

> Sn

£7 mn smmnde % y vm Rr

3 ld an WP PENIS SEE I WEN Ve

~ fy I TY ey 3 ba) ¥ a

fori Doae € an 8 i ws Sia a ute

§

. EY \ ~ gama vat [atin Vol | RATE “ £T £712 50 fry dey pes ATL in Ee sida oP River wich 123.3 C23 la ma wo WP on

2d lal)

:

-. wt

LN

&

HR of ho pross ond rT A rath bE nl pr GA moe a a AE) hE a RAW, YS | FLARE ON FW J Wa neds ig Walia

i LT Sag | 4G oN

Nv wd Gr al POLIS

Soyo Ted on eo

L ER ~ ros ind LW RO

wt a ne s Arey gr ory de va " a op

ATTA wy ey 2 | A 3 y ; : X 2 H 190) : £3) 4 LR i WW Ne Moan wt ed WEE try v rs 2d 5a L RP el 3 - WPAN we TE wd

£m EE CT oy eo et rad oy 3 pe 3 \ + TY yao oy Bed J my p> & NCP TIE I A " : x Foi 3 yd oar . ant od Wd ir» Ft aT sak ul Tm y : , 33 on im am, mg die or a Ba men oO ti y Vid de ob J oh Nh eb 43 4 CERIN J RELL I COSINE LV fir ut oe

- — Sige mt £3 pin mene die Jy eg ETRE 1 34 £ Prag — £73 = pen Ni \ » iY ; LH ered D binawen tao ts 0 Lr WIE REALL RR AKS . RIP SR 3 - : , . AIM LT moon 2 ES omen Fd sey a pra PY AN TET ne by) gy omy oie ee puny

wit Gy ad Mois cep LY Qo 0 4 92 SE Nico wi

& amy Be rn my ee ay 4 IE ST. | emo Para Th Pe il aT EL re Tl EE

arty

£ aR yh Pun on

vor bol Wain 3 tl ldo Qieniid Sid mse ka pari Rr 8 ULI Nis ed WF RD wt Rd

we

ew d wud sum A een dv gb SA AC ives lg | srmesle sews de aes Fin edd CRN - " ak CaP Lx WX 3 p tcl 'S A wd WES a ‘ : Ra ra or Ye I. Pat Tl a Be : Ean a la Te te Eat a aa Te LT Pa be oy 3 Eid VAP W iw od Nd LTR I | a brad \ Jud anciiin Nl Nr onal a fd

II TL SR, . Sp ¢ 3 ” 2% gy Ae . Ary. Pwd eye ~~ 3 Rico vr 308 WI i”, dink re bo 53 0d AF WA 0d 4 cd wh Wan Vk REEL 1 a TL Tsu obo No 4)

el AY Fr a yey ty Al Noy ED } ' 34 1 of, Feu rieg pale Ihemn 3 FR po Wada, wd & 3 L¥ hs yp a or Yori Lh PER Me ite Yo ney > - Fd = =n . nd yh Be py vam gm oan Ey Bn om ey oy mete wry oo 3

wl 2d adn WF 2 Pv 3 yd 2 oF Tar bd [ESAS PETE |

»y :

3 ; lala rt ENA a tS Ras EAs

Gs Wan Br nf wedded Ar Ye ERD ad er i

st Id 2 md LO > Ln oy ERT t i Gove wig = aya Pk 0 Lad 4 x mmlociaey > 3 nS tho

uo Mir ms

A oF We » Wo wa Live i emit Seda hee i ta ir RP Be

TE Bh rel 27 ers an Da of #

GO i ! y 14 1

: to on bt id

vy Rp —

ia Nd ir Be NF peo

+

ot WF wp WG lad

. -

; a “ | 4 -m»

LW - vive wl Nl Xam Pr ¢ Sw

id El rn an =a am and py £m ory on vy od .

a .% SEPM iF

BF wf at ad wes J we Ws

ws

“ 5 ’ “ | py fe ym 3 Pee ye on urd a 8, TY vy At

& arn wd Sv we Ls wr | JRE

FIRE WP FERS a NF Gr wa yy wo “a Se

» re . G3 poy oo I ominmm Rrra Rata bite N PR FR wi Wy Lod $d Berl hebd Wl aa Dd Adina Wa WT Wn lL

7% dy rm om 4 T BF oom arg om x Rn hes TT Pala Ba Feb h >) = end Eat de | gata pron $d nd iid GF fon LEP J WEE NF Ess ud Rd Nf dos hg £3 of :

rl

rvs WW ND

RTRES BE HE SAS TERRA

Pisin raed i 2

PARNER WR 3

-

y wom &

Sd wf

>

Yo

&

yy

ten wing (D

4 py ramen

LN a Lo

nA

_ au IY

We be Naw

>

FIN TR pay ary

LI

ali!

> 4 PL eR SET LW 3

A ea

- .

% ;y rene

: <

h! p 2Y

3 ® f &.

3

4 . '

ji #3

-

INE BP TEN

WN e's A

“

i fd

Nr pe

y ala

ade FT ald

LPL RVR SR