Court Aids Retarded Youth Interrogated by GA Police

Press Release

November 18, 1967

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 5. Court Aids Retarded Youth Interrogated by GA Police, 1967. 8bd3d13f-b892-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9ed19392-bb8e-4ba3-bf23-4784a96335c4/court-aids-retarded-youth-interrogated-by-ga-police. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

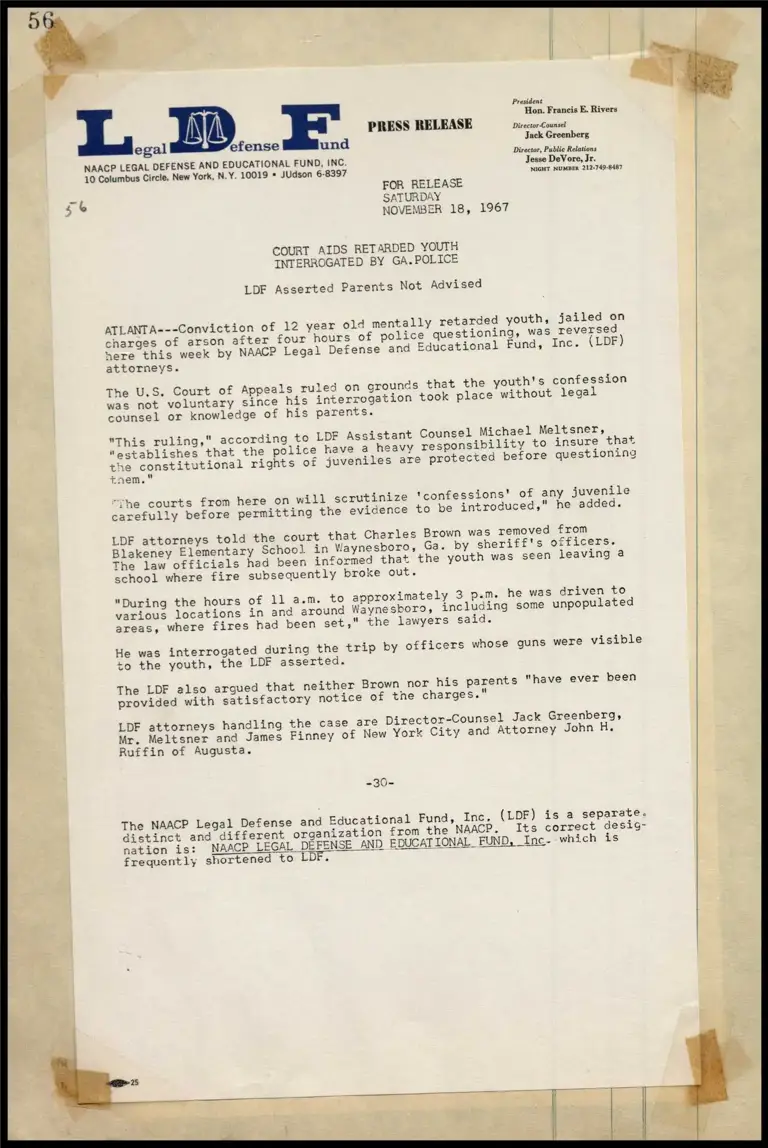

PRESS RELEASE

egal efense und

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

10 Columbus Circle, New York, N.Y. 10019 » JUdson 6-8397

FOR RELEASE

SATURDAY

NOVEMBER 18, 1967 =6

COURT AIDS RETARDED YOUTH

INTERROGATED BY GA.POLICE

LDF Asserted Parents Not Advised

President

Hon. Francis E. Rivers

Director- Counsel

Jack Greenberg

Director, Public Relations

Jesse DeVore, Jr.

NIGHT NUMBER 212-749-8487

ATLANTA---Conviction of 12 year old mentally retarded youth, jailed on

charges of arson after four hours

attorneys.

The U.S. Court of Appeals ruled on grounds

was not voluntary since his interrogation

counsel or knowledge of his parents.

"This ruling," according to LDF

"astablishes that the police have a

of police questioning,

here this week by NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

was reversed

Inc. (LDF)

that the youth's confession

took place without legal

Assistant Counsel Michael Meltsner,

heavy responsibility to insure that

the constitutional rights of juveniles are protected before questioning

Ee

“The courts from here on will scrutinize ‘confessions

carefully before permitting

of any juvenile

the evidence to be introduced," he added.

LDF attorneys told the court that Charles Brown was removed from

Blakeney Elementary School

The law officials had been informed that the youth was

school where fire subsequently broke out.

"During the hours of 1l a.m. to approximately 3 p.m.

various locations in and around Waynesboro, including some

areas, where fires had been set," the lawyers said.

in Waynesboro, Ga. by sheriff's officers.

seen leaving a

he was driven to

unpopulated

He was interrogated during the trip by officers whose guns were visible

to the youth, the LDF asserted.

The LDF also argued that neither Brown nor his parents

provided with satisfactory notice of the charges."

LDF attorneys handling

Mr. Meltsner and James

Ruffin of Augusta.

-30-

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

distinct and different organization from the NAACP.

nation is:

frequently shortened to LDF.

"have ever been

the case are Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg,

Finney of New York City and Attorney John H.

Inc. (LDF) is a separate.

Its correct desig-

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, Inc- which is