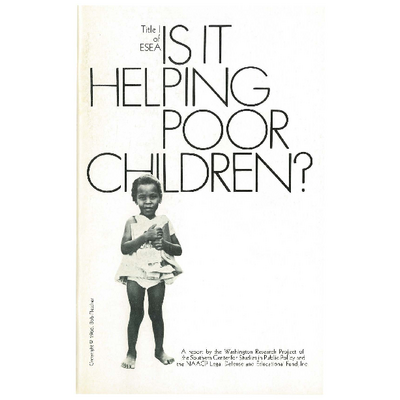

Is It Helping Poor Children?

Reports

December 1, 1969

87 pages

Cite this item

-

Division of Legal Information and Community Service, DLICS Reports. Is It Helping Poor Children?, 1969. 9ab82912-799b-ef11-8a69-6045bdfe0091. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9ee931f7-a808-4ebb-a46f-c49bbd56e006/is-it-helping-poor-children. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

@

1:

.~

~

0

u

A report by the Washington Research Pro/'ect of

the Southern Center for Studies in Public Po icy and

the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

Title I

of

ESEA

Washington Research Project

1823 Jefferson Place, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

10 Columbus Circle

N.Y. , N.Y. 10019

~\G

Revised second edition

Copyright © December, 1969. Washington Research Project and

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION . .

Why This Review of Title I .

How This Review Was Conducted

What This Report Covers . .

CHAPTER I: HOW TITLE I WORKS

v

vii

vii

The Formula . . 2

The Participants . 2

Level of Funding 3

How the Money is Spent 3

CHAPTER II: TITLE I AS GENERAL AID 4

Aid To All Schools . 5

Aid To Non-Target Schools 9

Failure To Concentrate Funds 9

Misuses of Concentration . 12

State Agencies' Use of Title I

as General Aid 12

CHAPTER III: TITLE I IN PLACE OF STATE

AND LOCAL MONEY . 15

Equalizing Poor Schools With Other Schools . 16

Assuming the Funding of Programs Previously

Supported by State and Local Funds . 19

Title I and Other Federal Programs . 21

CHAPTER IV: CONSTRUCTION AND EQUIPMENT. 23

Construction . 24

Equipment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

CHAPTER V: FAILURE TO MEET THE NEEDS OF

EDUCATIONALLY DEPRIVED CHILDREN 29

CHAPTER VI: LACK OF COMMUNITY INVOLVE-

MENT AND DENIAL OF INFORMATION . 36

CHAPTER VII: FEDERAL AND STATE

ADMINISTRATION OF TITLE I 43

Division of Responsibility 43

State Management . 47

Approval of Projects 49

Audit of Projects . . 49

Federal Administration 52

The Office of Education

and Mississippi 53

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 57

FOOTNOTES 59

APPENDIX A 66

APPENDIX B 72

APPENDIX C 73

INTRODUCTION

In 1965 Congress passed the Elementary and Secondary Educa

tion Act (ESEA), the most far-reaching and significant education

legislation in the history of this country. For the first time, the

national government recognized the necessity of providing Federal

aid to elementary and secondary schools. For the first time, the

special needs of poor children were recognized and effective ame

liorative action promised through special assistance to school

systems with high concentrations of low-income children.1

Our hopes that the Nation would finally begin to rectify the in

justices and inequities which poor children suffer from being de

prived of an equal educational opportunity have been sorely dis

appointed. Millions of dollars appropriated by the Congress to help

educationally deprived children have been wasted, diverted or

otherwise misused by State and local school authorities. The kinds

of programs carried out with Federal funds appropriated to raise

the educational levels of these children are such that many parents

of poor children feel that Title I is only another promise unful

filled, another law which is being violated daily in the most flagrant

manner without fear of reprisal.

We have found that in school systems across the country Title I

• has not reached eligible children in many instances;

• has not been concentrated on those most in need so that there

is reasonable promise of success;

• has purchased hardware at the exp.ense of instructional

programs;

• has not been used to meet the most serious educational

needs of school children; and

• bas not been used in a manner that involves parents and

communities in carrying out Title I projects.

This study examines what has happened to Title I in the four

school years since ESEA was passed. This is not an evaluation of

compensatory programs, but a report on how Title I money has

been spent and bow Title I bas been administered at the local,

State, and Federal levels.

Since passage of ESEA, Congress has appropriated $4.3 billion

for the benefit of educationally deprived poor children-black,

brown, white, and Indian children. Because most of these children

attend inadequately financed and staffed schools, the windfall of

Federal appropriations no doubt brings many improvements to

these schools that these children never had. To hear the educa

tional profession and school administrators talk (or write), Title I

is the best thing that ever happened to American school systems.

Educational opportunities, services, and facilities for poor children

are provided. Some poor children are now well fed and taught by

more teachers in new buildings with all the latest equipment,

materials, and supplies. Early evaluations of academic gain have

not been so optimistic. Some school systems report that despite

the massive infusion of Federal dollars, poor children are not

making academic gains beyond what is normally expected. Some

report moderate academic gain in programs, and some report real

academic improvement.

Despite these reports, the almost universal assumption about

Title I is that it is providing great benefits to educationally disad

vantaged children from low-income families.

We find this optimistic assumption largely unwarranted. Instead

we find that:

1. The intended beneficiaries of Title I-poor children-are

being denied the benefits of the Act because of improper and

illegal use of Title I funds.

2. Many Title I programs are poorly planned and executed so

that the needs of educationally deprived children are not met.

In some instances there are no Title I programs to meet the

needs of these children.

II

3. State departments of education, which have major responsi

bility for operating the program and approving Title I project

applications, have not lived up to their legal responsibility

to administer the program in conformity with the law and

the intent of Congress.

4. The United States Office of Education, which has overall

responsibility for administering the Act, is reluctant and

timid in its administration of Title I and abdicates to the

States its responsibility for enforcing the law.

5. Poor people and representatives of community organizations

are excluded from the planning and design of Title I pro

grams . In many poor communities, the parents of Title !

eligible children know nothing about Title I. In some com

munities, school officials refuse to provide information about

the Title I program to local residents.

These practices should be corrected immediately. We recom

mend that:

1. The Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW)

and the Department of Justice take immediate action against school

systems where HEW audits have identified illegal uses of Title I

funds and, where indicated, restitution of misused funds demanded.

2. HEW enforce the requirement for equalization of State and

local resources between Title I and non-Title I in schools in dis

tricts throughout the country; in Mississippi such equalization be

required by the 1970-71 school year as recommended by the Com

missioner.

3. HEW immediately institute an effective monitoring and

evaluation system to insure proper use of Title I funds; the Title I

office be given additional staff and status within the Office of Edu

cation; and a capable director be appointed forthwith and made

directly responsible to the Commissioner of Education.

4. An appropriate Committee of Congress immediately con

duct an oversight hearing and examine on a systematic basis the

manner in which Federal, State and local school officials are using

Title I funds.

5. The provision requiring community participation under

Title I be maintained and strengthened.

iii

6. Alternative vehicles for operation of Title I programs be

provided where State and local officials are unable or unwilling to

operate effective Title I programs. For example, private non-profit

organizations are permitted to operate Title I programs for migrant

children.

7. HEW enforce the law; States be required to approve only

those projects which conform with the Title I Regulations and the

Program Criteria.

8. Congress provide full funding under the Act in order to

ensure sufficient resources to help poor children.

9. All efforts to make Title I a "bloc grant" be rejected.

10. Further study be undertaken on issues raised in this report

including:

a. use of Title I to supplant other Federal funds;

b. equitable distribution of funds to predominantly Mexican

American districts;

c. Title I programs for migratory and Indian children; and

d. relation between Title I and all other food assistance

programs.

11. Local school systems make greater effort to involve the

community, including disclosure of information regarding Title I

programs and expenditures.

12. Private citizens demand information and greater community

participation on local advisory committees; denial of information

and illegal use of funds be challenged by community groups and,

where appropriate, complaints made to local, State and Federal

officials; lawsuits be filed and other appropriate community action

be undertaken to ensure compliance with the law.

13. States assure that Title I programs actually meet the educa

tional needs of all poor children and recognize the cultural heritage

of racial and ethnic groups.

The goal of Title I is simple. It is to help children of poor fam

ilies get a better education. Accomplishing that goal, however, is

not simple. Existing educational structures at the State and local

levels are the institutions responsible for the administration of

Title I, but often they are the institutions least able to respond to

IV

a new challenge or to respond to the needs of poor minorities. In

order to accomplish the goal of Title I, many changes will be

needed. But before we can understand the nature of the changes,

we need to understand what the law provides and how in fact it is

operating in school districts across the country. That is the sub

stance of this report.

Why This R eview of Title I

Reviews and evaluations of Federal grant-in-aid programs are

usually made by "experts." This review was not prepared by edu

cational "experts," but by organizations interested in the rights of

the poor. We make this review because we feel that the accepted

experts have fai led to inform the public honestly about the faulty,

and sometimes fraudulent, way in which Title I of the Elementary

and Secondary Education Act of 1965 is operating in many sections

of the country.

In December 1968, Federal education funds were terminated in

Coahoma County, Mississippi because of the school board's refusal

to submit an acceptable desegregation plan under Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964. As a consequence of the termination of

Federal funds , teachers, teacher-aides and janitors, all black, were

fired. Their salaries had been paid by Title I , and their employment

in the black schools was terminated along with the Title I funds.

A group of parents and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund, Inc. brought suit against the Coahoma County School

Board charging illegal use of Title T funds as well as the unconsti

tutional operation of a racially dual school system. The lawsuit

represented the first, and, thus far, the only serious challenge to the

manner in which a school system utilizes its Title I funds.2

In the spring of 1969, a small group of private organizations

involved in the struggle for equal educational opportunities for

poor and minority children agreed that they needed to pool their

resources to examine how Title I funds were being used, and to

what extent the educational needs of these children were being met

as Congress intended. We knew that the situation in Coahoma

County was not an isolated situation. Our decision to look at Title I

was based not only on the incident in Coahoma County, but also

on a number of complaints from individuals and organizations

across the country about the operation of Title I in local districts.

v

We had three basic concerns about Title I. First, poor people

knew little or nothing about the provisions of the law. They had

even less to say about how these Federal funds were being used in

their school districts despite the fact that the Title I Regulations

require that they be involved in the planning and execution of

Title I programs. Second, we suspected that much of the Title I

investment was not being spent in accordance with the law and

Regulations, and that much of the money was being used as general

aid and in place of State and local education revenues. Third, we

felt that an independent review was needed to determine whether

the money was really being spent for the educational needs of edu

cationally deprived children.

Some may think that by inquiring into Title I we risk renewing

old battles over Federal aid to education. Some may think that

criticism of how Title I money is spent or the program adminis

tered could jeopardize the entire legislation. Some may take the

position that it is better to have Title I funds, even though they may

not always be used exactly as Congress intended, than not have

them at all. Still others may feel that any use of these funds helps

in the process of educating children, even if the expenditures are

in violation of the law.

We disagree. We believe that poor and minority children should,

indeed must, have the rights and benefits accorded them by law.

We have decided to pursue our efforts because ultimately it is

educationally deprived children who will be held accountable for

the Federal investment. All the tests and evaluations to determine

the effectiveness of Title I will be administered to poor children,

not to school administrators or to State and Federal officials. Thus

it seemed only right that poor people themselves, and private or

ganizations working on their behalf, should make an attempt to

find out what is happening to poor children as a result of the

expenditure of billions of dollars.

This report is intended as a defense of Title I. Our criticisms

are offered in order to make its operation more effective and to

ensure that the Congressional intent is implemented. We believe

that Federal aid to education is now firmly embedded in our system

and should be encouraged, not weakened. However, we feel obliged

to report to poor people, to minority people, to the President, to

Congress and to the Nation what we have learned about Title I of

vi

the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965. We hope

by bringing to light some of the more flagrant misuses of Title I

funds that a concerted and continuing effort will ensue to help poor

children get what the Nation promised them when the Act was

passed.

How This Review Was Conducted

We collected information and interviewed officials at all levels

of Title I's operation. As we wanted to know what the Federal

government already knew about Title I's operation, we began there.

We interviewed Federal officials and examined records and files at

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare. This report

relies heavily on information taken from government documents,

especially the audits of Title I performed by the HEW Audit

Agency.

In addition to reviewing the program at the Federal level, we

gathered information about Title I in selected local school systems

and State departments of education to find out what programs were

operating and what the attitude of school officials was toward Title I

and toward poor children. We also interviewed parents in order to

determine how much they knew about Title I and how they had

been involved in Title I programs in local school districts. These

interviews were conducted by staff members of private organiza

tions and, in many cases, by local residents, members of poor com

munities. Together we interviewed Title I officials in nine States, 28

Title I coordinators of local districts, 39 principals or teachers in

Title I schools and 191 parents.

The State and local systems from which we gathered information

were chosen on the basis of several criteria. An attempt was made

to get a rough cross-section of State and local systems which would

represent different regions, various sizes of enrollment and mixtures

of racial and ethnic groups. We gathered information from rural

school districts, from small and medium-sized urban systems, and

from large metropolitan systems.

What This Report Covers

This report deals with the major part of the Title I legislation

aid to local school systems with high concentrations of children

vii

from low-income families. In fiscal year 1969, $1.02 billion went

to these school districts out of a total Title I Congressional appro

priation of $1.1 billion. This report does not treat two other cate

gories of financial assistance under Title I, aid to children of migra

tory farm workers and Indian children attending schools operated

by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.3 Nor does this report cover poor

children in institutions for the neglected and delinquent, although

they are all identified in the Act as beneficiaries of Title I. This

does not mean that we feel that there are no problems connected

with their operation. On the contrary, we know that there are

problems and hope that these programs will receive early attention.

Only because of their low dollar value and because of our limited

resources are they excluded here.

This report focuses on how Title I money is spent, how Title I

is administered and some of the consequences for poor children

resulting therefrom. It does not attempt to evaluate the educational

value of specific Title I programs nor the impact of various kinds

of compensatory education programs, although when we have dis

covered Title I sponsored programs which we feel have no educa

tional purpose at all , we say so.

Chapter I explains briefly how Title I works, and specific refer

ences to the Title I Regulations, the law, and the Program Criteria

will be found in Appendix A. Chapter II deals with the use of

Title I as general aid in many school systems. Chapter III examines

the illegal use of Title I in the North and South to supplant State

and local expenditures and the relation between Title I and other

Federal programs. The purchase of massive amounts of equipment

and the excessive construction of facilities is the subject of Chapter

IV. Chapter V deals with the failure of some Title I-funded projects

to meet the educational needs of poor children. Chapter VI deals

with the exclusion of the poor community from decisions about use

of Title I and the refusal of State and local school officials to pro

vide information about Title I. Chapter VII examines how Title I is

administered at the State and Federal levels.

Many organizations and individuals have contributed to this

report. Although the Washington Research Project and the NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. assumed major respon

sibility for this report, other organizations contributing to the effort

included the American Friends Service Committee, The Urban

viii

Coalition, the South Carolina Council on Human Relations, the

Illinois Commission on Human Relations, the Delta Ministry of the

National Council of Churches and the North Mississippi Rural

Legal Services. We appreciate the help we received from the Office

of Education and HEW Audit Agency staff. We are especially

grateful for the financial support for this report from the Aaron E.

Norman Foundation and the Southern Education Foundation.

Numerous individuals in communities across the country gave their

assistance. Chief among these individuals are the following: Wini

fred Green, Roger Mills, Michael Trister, Beatrice Young and

Electra Price. Ruby Martin of the Washington Research Project

and Phyllis McClure of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund, Inc. had the responsibility for the final preparation of

this report.

ix

I

I

HOW TITLE I WORKS

Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965

provides financial assistance to school systems which have high

concentrations of low income children residing within the districts.

This Act is entirely Federally financed and requires no matching

grant. Approximately 16,000 out of a total of 26,983 school

districts in the Nation receive T itle I money. An estimated nine

million children participated in some way in a Title I-funded

project in the 1968-69 school year. 1

Payments under Title I go to State departments of education,

which in turn make payments to local school districts. Local dis

tricts are eligible under the law to receive a certain amount estab

lished by formula upon submitting a project application. Local

school officials may use the money for a broad range of projects,

but the expenditures must be in conformity with the law, the Regu

lations, and certain Program Criteria established by the U.S. Com

missioner of Education. The project application of a local school

system must set forth (1) the program or programs to be supported,

(2) a budget, (3) the number of eligible children, (4) designated

target areas, (5) an identification of the needs of eligible children,

and (6) provisions for evaluating the programs or projects . The

State department of education is responsible for approving, reject

ing, or renegotiating the project applications from local districts.

These project applications do not go to Washington. The State is

entirely responsible for paying funds, approving project applica

tions, monitoring, audit ing, and evaluating the effectiveness of

projects.

In effect, Title I operates as a "bloc grant" since the money may

be used in any manner the State approves as long as it is spent on

disadvantaged children. Although the States determine how Title I

money will be spent, each State must provide assurance to the

Office of Education that it will approve projects that meet the re

quirements of the law. For example, States may not permit Title I

to be used as general aid to a school district or in place of State

or local funds. The purpose of Title I is to provide special educa

tional programs for educationally deprived children most in need

of assistance, and according to the Federal Regulations, the pro

gram must be of such size and scope as to have reasonable promise

of success. Each local district must determine the needs of the

eligible children in its schools and what programs it will operate to

meet those needs. The Regulations and Program Criteria governing

Title I are numerous and complex, but their purpose is to set

standards for the wisest use of the money. Excerpts from the Fed

eral Program Criteria are cited in Appendix A.

The Formula

The amount of money which a local district receives is based on

a formula which is determined in the following manner: The num

ber of children in the district from families with annual incomes of

$2,000 or less (determined by the 1960 Census) is added to the

number of children from families receiving AFDC (welfare money),

plus the number of children in institutions for the neglected and

delinquent. This total number of children is then multiplied by half

the State per-pupil expenditure or by half the national per-pupil

expenditure, whichever is greater.

The Participants

Although an estimated nine million children participated in some

way in a Title I-sponsored project during the 1968-69 school year,

it is important to understand that Title I does not reach all poor

children who are educationally disadvantaged. The Office of Edu

cation estimates that about 18 percent of the students in Title I

participating schools are severely educationally disadvantaged, and

that only slightly more than 50 percent of those pupils are partici

pating in Title I compensatory programs (reading, arithmetic, and

language).2

2

Level of Funding

There has always been a wide gap between the amount author

ized by Congress ($2.7 billion), and the amount actually appro

priated for Title I. In fiscal year 1969 Congress appropriated

$1.123 billion, only 41 percent of the amount authorized. The

$1.123 billion represented a cutback of $68 million from the pre

vious year. ESEA is before the Congress this year for an extension

of the legislation and appropriation of funds for the 1969-70 school

term. The present Administration has asked Congress to appropriate

$1.216 billion for Title I.

How the Money is Spent

There is cause for alarm when Congress does not appropriate

sufficient funds to meet its own professed commitment to serve the

educational needs of children from America's low-income families.

These children will never get a chance unless there are significant

Federal resources behind the Congressional rhetoric. The declining

appropriations and the rising cost of education mean fewer oppor

tunities for poor children who suffer educational handicaps. While

we are concerned about this weakening Federal support, and urge

full funding under the Act, we are dismayed about the failure of

many local school officials to use the available money in the best

interests of poor children. We note with interest what the National

Advisory Committee on the Education of Disadvantaged Children

has said:

"Some [projects] are imaginative, well thought-out, and demon

strably successful; other projects exemplify a tendency simply

to do more of the same, to enlarge equipment inventories or

reduce class size by insignificant numbers." 3

3

II

TITLE I AS GENERAL AID

Title I money is not to be used as general aid. To do so dilutes

services to poor children and denies them crucial benefits under

the Act. When Congress enacted ESEA, it intended that Title I

would enable local school districts to provide services and programs

which they were unable to provide to meet the special educational

needs of educationally disadvantaged children. However, many

school districts see this massive infusion of Federal funds as an

opportunity to improve their schools generally, to buy large amounts

of equipment and supplies, and to construct buildings and additions

to schools. No doubt much of the money spent in this way has

provided needed resources to the total educational program. No

doubt many poor children benefit from having services, facilities

and teachers that they may never have had before. Despite this,

they are still being cheated because they are not receiving the full

impact of the legislation.

The determinations as to which children should receive Title I

assistance are clearly spelled out in the legislation passed by Con

gress, in the Federal Regulations, and in a number of Program

Criteria. 1 The law specifies that Title I assistance should go to:

• Individual children, not entire school populations;

• Children who have one or more educational handicaps and

who come from low-income families, not all children in all

poverty-area schools;

• Programs that seek primarily to raise the educational attain

ment or skills of children, not exclusively to projects or

4

services dealing with health, welfare, or recreational needs

of poor children.

Our review of HEW audits and our interviews reveal that re

quirements for identifying the educational needs of children and

for concentrating funds have been frequently ignored. Instead of

focusing Title I resources on the educational problems of those

poor children most in need, Title I is frequently used as general

aid. The use of Title I as general aid typically falls into four cate

gories:

1. Title I funds purchase services, equipment, and supplies that

are made available to all schools in a district or all children

in a school even though many children reached are ineligible

for assistance.

2. Title I funds are spread around throughout all poverty-area

schools instead of focusing on those target areas with high

concentrations of low-income families.

3. Title I funds are not going to eligible children at all.

4. Title I State administration funds support non-Title I opera

tions of State departments of education.

Aid To All Schools

• Curriculum and materials centers, language and science labora

tories are common uses of Title I funds as general aid. These cen

ters usually contain books, supplies, visual aids, equipment, and

other learning "hardware" that can be checked out by any teacher

in the school system. These centers are frequently located in the

school system's central office, in a Title I purchased mobile unit,

or at a non-Title I school rather than at a "target" school. While

Title I children may receive some benefits from these centers, so

do all children whose teachers avail themselves of the materials.

SOUTH CAROLINA boasts of 23 such centers. Eight out of 18

MISSISSIPPI districts surveyed by Office of Education staff had

instructional materials centers. 2

• HEW auditors found that three GEORGIA school districts

were making Title I projects available to all schools in the system.

GWINNETT COUNTY had a mobile curriculum center, costing

5

$70,646, serving all schools. A $340,763 reading clinic served all

schools in MUSCOGEE COUNTY. In BIBB COUNTY a $459,068

curriculum materials center served all schools.3 Our interviewers in

Bibb County reported that consultants and educational television

funded by Title I are also available to all teachers and all children

in the system.4

• In OXFORD, MISSISSIPPI, a curriculum and materials cen

ter is located at a non-Title I school, near a police station, report

edly for fear of burglary. Furthermore, the Title I coordinator in

Oxford is principal of a non-Title I, white school.5

• In GREENE COUNTY and SUMTER COUNTY, ALA·

BAMA, and in NEW ALBANY, QUITMAN COUNTY, and

PONTOTOC COUNTY, MISSISSIPPI, Title I coordinators told

our interviewers that Title I material and equipment are available

to the entire district. 6

• An HEW audit of MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN disclosed that

in fiscal year 1967, $21 ,605 was spent on salaries for school per

sonnel not involved in Title I projects, such as the swimming coach

and teachers assigned to general teaching duties. 7

• ATTALA COUNTY, MISSISSIPPI constructed two lagoons

for sewage disposal, costing $16,000, with Title I money and in

stalled an intercom system costing $1,750.8

• In CAIRO, ILLINOIS, Title I money was used to support

general overhead costs. Title I paid for half the rent of a building

which housed the administrative offices of the school district.

Title I offices were located on the second floor of the building.9

• The 1967-68 Title I Project Application of WAUKEGAN

(District 61), ILLINOIS revealed that Title I paid the full-time

salary of an assistant principal who performed general adminis

trative duties at his school. Nineteen percent of the school's enroll

ment was eligible for Title I benefits.10

• The DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA school system charged the

Title I budget during fiscal 1966 through 1968 for salaries of per

sons who were not performing duties connected with the program.

The school system apparently selected each year a certain number

of employees to be paid out of the Title I budget. For 1968 they

selected 10 and the auditors found that only one of the 10 was

working primarily on Title I activities. "The remaining nine em

ployees were devoting only a negligible amount of time to Title I

6

activities or dividing their time between Title I projects and other

general school activities." 11

• In BENTON COUNTY, MISSISSIPPI, interviews with the

superintendent, Title I coordinator, and a teacher revealed that

Title I is being used to benefit children in the system whether or

not they have been identified as educationally disadvantaged. The

district has 2,020 students and all children in the district's three

schools participate despite the fact that the Title I coordinator said

Title I eligibility was determined by income, size of family, and

whether or not the child lived on a farm. Seventy-one percent of

the county was said to have an income below $3,000 per year. In

the 1968-69 school year, Title I funded an Instructional Resources

Center, a heating system for one school, and a summer curriculum

study for nine teachers and nine college student assistants. In addi

tion, a summer school was funded by Title I at two of the three

schools (one all-white school and one predominantly white). The

Title I summer school was open to "all students who need a credit

to meet minimum requirements for graduation or who want an

extra math subject credit." A principal told our interviewer that

five regular classroom teachers were hired with Title I money. In

the summer of 1968, Title I paid for an arts and crafts program in

which any child who was interested could participate. 12

• A review of OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA's $2.75 million

Title I program by the State's Office of Compensatory Education

disclosed a number of problems. It found that health and psycho

logical services, and guidance and counseling services, were reach

ing more children than the determined number of participants, thus

diluting services to participants. Other parts of the Title I program

were not reaching all participants. For example, a reading program

designed for 8,000 elementary pupils reached only 4,851 pupils.

As a result, the State report found that the Title I program "tended

to become . .. one of general aid to the local schools" rather than

"a comprehensive compensatory education program for individual

children." 13

Oakland's Title I program rotated Title I participants in and out

of Title I activities on a " turnstile basis" so that there were no

planned comprehensive services for individual children. In addition,

the State found that approximately 28 percent of the total profes

sional staff worked in or out of the central office. A small number

7

of these staff persons provided direct services to identified par

ticipants.14

• The INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA public schools purchased

five school buses with Title I money, but HEW auditors found

that only 25 percent of the time the buses were operating were for

Title I field trips. During the remainder of the time, the buses were

on regular daily school runs. The HEW audit of Indianapolis also

revealed that Title I paid social workers and counselors who were

assigned to Title I schools but there was no documentation that they

actually worked at those schools.15

The installation of educational television and data processing

equipment in the central office of local school systems, which serve

all schools and all children in the system, is another way in which

Title I is used as general aid.

• The MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE school system received approval

from the State Department of Education for a project to improve

pupils' reading ability. The project called for hiring additional staff.

At the end of the 1965-66 school year the Memphis superin

tendent advised the State "that a total of $197,525 of project funds

were unexpended because the school system was unable to fully

staff the project." He requested and received approval to use the

unused funds for an IBM computer-based system for accumulating

and reporting development on each pupil within the Title I area.16

The HEW Audit Agency asserted that the State should not have

approved the project:

"School officials told us that their data processing center oper

ated as a service agency to all departments of the Memphis

Board of Education. Thus we believe that since the IBM equip

ment purchased under the project became an integral part of the

existing data processing center and since the center serves all

departments within the school system, the project equipment was

purchased primarily to improve general school programs rather

than specifically for ESEA Title I purposes. Local school offi

cials confirmed our conclusion. They told us that eventually the

equipment would serve all schools in the system." 17

• In FRESNO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA, during fiscal years

1966, 1967 and 1968, several school districts transferred approxi

mately $930,000 to the county superintendent to construct, equip

and operate a county-wide instructional television system which

8

benefited not just educationally deprived children but all children

in the county. Part of this money was used to remodel a county

owned building for a television studio, to purchase and install

equipment and to operate the system.18

Aid to Non-Target Schools

In some cases, Title I does not even reach educationally deprived

children.

• An HEW audit of LOUISIANA school districts covering Title

I expenditures in fiscal year 1966, the first year of the program,

found that 23 parishes (counties) "loaned" equipment costing

$645,624 to schools that were ineligible to participate in Title I

programs. The auditors noted that much of the "loaned" equipment

was "set in concrete or fastened to the plumbing." Much of the

equipment had been at ineligible schools since its acquisition.19

• In the DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, $264,714 was spent at

45 schools that had not been designated as target schools. And

$224,733 of the $264,714 was spent at 25 elementary schools

which had less than the average incidence of eligible children.20

• An HEW audit of selected CALIFORNIA school systems

covering September 1965 through August 1968, found that the

SHASTA UNION HIGH SCHOOL DISTRICT had spent Title I

money in fiscal years 1966 and 1967 in three high schools when

only one of these high schools was eligible. "The inclusion of the

two ineligible schools in the project," the audit report noted, "re

sulted in a substantial reduction of available funds for the school

th~t was eligible . . . " 21 The two ineligible schools were subse

quently dropped from the project under orders from the State's

Office of Compensatory Education.

• The CALIFORNIA audit showed that the SANGER UNIFIED

SCHOOL DISTRICT had spent $14,496 of Title I funds to pro

vide a portable classroom located at an ineligible school.22

Failure to Concentrate Funds

Federal law and Program Criteria require that Title I funds be

concentrated on a limited number of children most in need of

assistance, in a limited number of eligible attendance areas, and

9

that the Title I program be of sufficient size, scope, and quality to

provide reasonable promise of substantial progress. Concentration

of funds also means that a child must receive a variety of services.

If some children get only eyeglasses, some only dental care, some

only remedial reading, some only tutoring and some only field trips,

then services are not being concentrated.

Title I Regulations specify that aid must go to those areas of a

school district with a high concentration of low-income families and

educational deprivation. School officials determine these areas by

establishing the average percentage of low-income families in the

whole district and then concentrating funds in those areas that are

above the district-wide average. 23

Despite these Federal requirements, many school districts tend

to use Title I resources to reach as many children as possible, with

out regard to concentrating services on those most in need. The

consequence is to dilute services to children who qualify as Title I

beneficiaries. The use of Title I funds in this way in many districts

has simply failed to achieve the purposes of the legislation.

• In CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, the school board purchased approx

imately $3.8 million in audio-visual films and equipment for distri

bution to every school in the poverty area, rather than to only those

schools having a high concentration of children from low-income

families. 24

• An HEW audit of PENNSYLVANIA covering fiscal year 1967

disclosed that, in approximately 130 local school districts (out of

486 in the State), the Title I project application included schools

that did not appear to be eligible because they did not have the

required concentrations of children from low-income families.25

• A principal in OXFORD, MISSISSIPPI, told our interviewer

that all children in his school receive benefits from Title I even

though not all are eligible.26

The rationale for requiring concentration of funds is clear. The

larger the investment per child, the greater the likelihood that there

will be a significant impact on the educationally disadvantaged

child. The greatest testimonial to the lack of concentration and the

dilution of Title I resources is that i.n the 1967-68 school year the

average Title I expenditure per child was $108. In 1966-67 the

average expenditure per child was $99, and in 1965-66 it was $96.

10

The Title I National Advisory Council calls these expenditure levels

"hardly enough to make a difference." 27

An analysis of Title I programs in five school districts, done by

General Electric Company (TEMPO) under contract to the Office

of Education, reported:

"There is a general tendency to allocate . .. 20 percent of Title I

funds to a very small number of pupils and to allocate the other

80% over such a large number of pupils that in most cases the

funds amount to less than $5 per pupil." 28

Although per-pupil expenditure levels will vary from project to

project, the evidence shows that most of the Title I annual invest

ment is spread so thinly to so many children that there is little

reason to expect any substantial gain in academic achievement

from Title I participants.

The dilution of Title I money exists despite the Office of Educa

tion's requirement that the annual expenditure per child for Title I

compensatory services "should be expected to equal about one-half

the expenditure per child from State and local funds for the . . .

regular school program." 29 The Office of Education does not en

force this requirement and most States ignore it. While Title I

officials in a few States say that State policy is to encourage con

centration, only one State-CALIFORNIA-makes concentration

of Title I services mandatory. This year the California State Board

of Education announced that its supplemental policies for Title I

require that at least $300 per child be spent, over and above the

regular State and local expenditures, and that priority in designating

target schools should be given to elementary schools.30

In his testimony before the House Committee on Education and

Labor, Dr. Wilson Riles, Director of Compensatory Education in

the California State Department of Education, explained that this

State policy was adopted because:

"Our research and evaluation have shown that . . . piecemeal

projects which have attempted through a single-shot activity to

overcome learning handicaps caused by poverty [have] usually

fail[ed] to result in demonstrable achievement gains ... We have

found that projects which concentrate at least $300 per child

over and above the regular school program were the most suc

cessful." 31

11

Misuses of Concentration

The requirement to concentrate services in target schools in a

limited number of attendance areas has been misused in some

school districts to frustrate school desegregation plans. The use of

Title I to upgrade black schools has served to discourage and in

timidate black students from transferring to white schools for fear

of relinquishing Title I benefits. This misuse of Title I funds was

pointed out over two years ago in a report by the U.S. Commission

on Civil Rights which stated that:

"Under free choice . . . improvement of substandard Negro

schools itself inhibits desegregation. As a result, the objectives

of improving the quality of education and achieving desegrega

tion conflict with instead of complementing, each other." 32

Despite this warning by a Federal fact-finding agency, the Office

of Education continued to allow Southern school boards to use

Title I funds to maintain the dual school system.

Federal Criteria provide that Title I services "follow the child"

and that they be offered at locatioqs which do not prolong the

child's racial, social, or linguistic isolation. These Criteria are largely

ignored. Most Title I projects are conducted in isolated settings,

and in many districts Title I services do not follow a child to a

school outside the target area. Interviewers in BIBB, TELFAIR

and WORm COUNTIES, GEORGIA and GREENE COUNTY,

ALABAMA reported that Title I services did not "follow the

child." 33 A State review of OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA's Title I

program revealed that 215 Title I eligible children did not get in

tensive academic help that was supposed to follow them.34

A few school systems which are totally or partially desegregated

have complied with the Criteria in their Title I projects and have

concentrated services on eligible children no matter where they

attend school, but most have not.

State Agencies' Use of Title I as General Aid

State departments of education bear the main responsibility for

the proper administration of Title I, but they are frequently not in

a position to act against local school systems for using Title I as

general aid as they are themselves guilty of using Title I for general

12

administrative aid. They invariably report that shortage of admin

istrative funds prevents them from hiring sufficient staff to carry

out their responsibilities adequately. While this is undoubtedly

true, some State agencies have used Title I funds to enhance the

State department of education and their general operations rather

than to administer Title I.

• INDIANA-"The State claimed administrative expenses total

ing $45 ,823 for fiscal years 1966 and 1967, which were not proper

charges to ESEA, Title I. In addition, the State Agency has con

tinued to improperly charge the ESEA, Title I, program for ad

ministrative expenses during fiscal year 1968 . . . Salaries and

related retirement costs, totalling $40,244 (included in the $45,823),

have been questioned for those personnel who, by the nature of

their positions, could not have expended 100 percent of their efforts

for the benefit of ESEA, Title I program." 35

• SOUTH CAROLINA-Salary increases for State personnel

were charged even th<;>Ugh the personnel did not work full-time on

Title I. "Effective January 1, 1966, the State Department of Edu

cation granted salary increases of varying amounts to ... 69 per

sons who were at that time full-time employees of the State agency.

In his letter requesting State Budget and Control Board approval

of the increases, the State superintendent of education stated,

'Several of the people are working on the Federal projects now and

have been for quite some time.' The salary increases [for all 69

persons] were approved and the entire amount of the increases was

charged to Title I funds ... Title I funds [were] used to pay sal

aries of full-time State agency personnel donating less than full-time

to the program totaled approximately $31,900 for fiscal year 1966

and $54,300 for fiscal 1967.'' 36

• LOUISIANA-An HEW audit report, dated October 27, 1967,

states that the Louisiana State Department of Education used

Title I administrative funds to pay for costs "not directly related to

the program, obligation of services to be rendered after the end of

the project, a duplicate payment and various other unallowable

costs. The total costs questioned [by the HEW Audit Agency] for

State Administration amounted to $68,296 or 43% of total the

costs claimed by the State. . . . " 37

• NEW JERSEY-Salary payments in the amount of $44,114

were charged to Title I funds for employees donating less than

13

full-time to Title I activities. The State department claimed that

the charges were reasonable because other employees of the de

partment donated time to Title I activities and none of their salaries

were charged to Title I. The HEW auditors found no records to

support this proration of salaries." 38

• CALIFORNIA-Even in California, the HEW auditors re

ported: "For 1968, the State Department of Education ... drew

$81,856 for Title I funds in excess of recorded expenditures. In

addition, for 1966, 1967 and 1968 the [State] improperly claimed

Title I funds for the prorated cost of the Executive Section alld

claimed rental costs in excess of the amount properly allowable to

Title I." 39

• ILLINOIS-An HEW audit report issued June, 1969 states:

"Administrative expenses of $183,304 claimed by the State agency

for the three-year period ended June 30, 1968, were not directly

related to administration of the ESEA, Title I program and, there

fore, are not reimbursable with Title I funds." The questioned costs

consisted of acquiring and operating four mobile guidance vans for

another Federally financed program; salaries and related retirement

benefits for an assistant superintendent and divisional directors

whose positions would have been filled regardless of the Title I

program; and office equipment purchased with Title I funds but

used in other functional departments of the State agency.40

• ALABAMA-HEW auditors found that $130,939 in Title I

funds were spent in Alabama in fiscal year 1968 to supplement

salaries and travel of school superintendents and principals al

though they were not free to accept employment on Title I

projects.41

As these examples document, Title I is used as general aid to

entire school systems. It is not concentrated on those children most

in need. Some State agencies use Title I administrative funds for

general salary increases and other forms of general support for

State operations. Under these circumstances, it is impossible to

hold poor children responsible for dilution of resources intended

to benefit them.

14

III

TITLE I IN PLACE OF

STATE AND LOCAL MONEY

When Congress enacted ESEA, it intended that Title I funds

would supplement State and local education funds, not replace

them. Title I Regulations and Program Criteria are clear in this

regard. When school districts do not use Title I money in addition

to local and State funds, they are said to be supplanting local and

State money.1

This means that school districts must not decrease the amount

of money they are spending, or would have spent, in Title I eligible

schools just because they are receiving Federal money for students

in those schools. Title I is not to be used to equalize expenditures

in poverty-area schools with other schools in the district.

Congress could hardly sanction the practice of a school district

decreasing the amount of money going to a school simply because

that school was receiving Federal funds. In order for Title I to have

sufficient impact on the educational problems of low-income chil

dren, Federal expenditures must be over and above existing

expenditures.

In many ways this requirement is wishful thinking. Widespread

patterns of unequal expenditure between schools within the same

district existed prior to the inception of Title I North and South.

Schools enrolling large numbers of poor and non-white children

invariably receive less· State and local funds and less of the educa

tional resources invested in the education of children from middle

and upper-income homes. Title I funds are thus spent for pro-

15

grams in schools attended largely by children from low-income

families and are almost inevitably used to bring these schools up

to the level of other schools.

While the Office of Education requires that local school systems

show on the Title I applications that they are maintaining the same

per-pupil effort district-wide, it does not require comparative ex

penditure figures for all schools. Per-pupil expenditure may in

crease or remain the same on a district-wide average but it may

vary widely between schools within the district. Although compli

ance with the requirement for not supplanting State and local funds

is vitally important to a successful program, the local school dis

trict need only sign an assurance that it will comply. In fact, the

Title I application filled out by the local district does not even

require information necessary to determine whether funds will be

supplementary to local expenditures. There is apparently no effort

made at the State level to check whether a district is providing

equal programs and expenditures in Title I and non-Title I schools.

There are three basic kinds of supplanting:

1. Equalizing poor schools with other schools in the system.

2. Assuming funding of programs previously supported by

State or local funds.

3. Replacing other Federal money.

Equalizing Poor Schools with Other Schools

Southern States have traditionally operated unequal and dis

criminatory schools for blacks and whites.

In a recent report on how SOUTH CAROLINA used Title I

funds, the State Department of Education reported that approxi

mately 74 percent of all Title I recipients during the 1966-67

school year were black and that the same was true for the 1967-68

and 1968-69 school years. The South Carolina Director of ESEA

candidly admitted to our interviewer that much of the Title I

money was spent in black and poor schools to make them com

parable to white schools. This assertion is demonstrated by the

huge investment, amounting to $2-3 million annually, that the

State has made in black schools providing classrooms, libraries,

and other physical facilities.2

• During the 1968-69 school year, SUMTER COUNTY #2,

16

SOUTH CAROLINA operated a total of 13 schools, seven black

and five predominantly white. All five of the predominantly white

schools had libraries which were constructed with State and local

funds that were well stocked with books. At least six of the seven

all-black schools now have libraries also well stocked with books.

However, all six of these libraries were built and stocked since

1965 and with Title I funds. Apparently, the library books at the

white schools were paid for out of State and local money or per

haps Title II ESEA. 3

• Another school system, HAMPTON COUNTY, SOUTH

CAROLINA, in 1954 constructed with State and local funds, two

elementary schools, the Fennell Elementary for black and Hamp

ton Elementary for white students; one of the original features of

the Hampton School was a library. Using fiscal 1967 Title I money,

the school system purchased a mobile library and library books for

the Fennell School. Hampton County also built a new school for

black students in 1966 with State and local funds, complete with

library. However, furniture and books for the library were paid

for with Title I funds. 4

• Under a project entitled "Improvement of Curriculum and

Physical Needs of Students," BAMBURG COUNTY, SOUTH

CAROLINA received State approval to use Title I funds for the

construction of six new classrooms as permanent additions to

all-black Voorhees Elementary School. School officials stated in

justification that, "these classes are needed in order that the

teacher load may be decreased." Yet during the 1968-69 school

year, Voorhees Elementary School continued to have the highest

teacher-pupil ratio (1 -30) of any school in the system.5

The South Carolina ESEA Director commented that "Congress

assumed that there would be an effort to equalize expenditures

across schools. That assumption was wrong." He added that the

whole matter of supplanting was very unclear. His interpretation

was that "If in the past you did not spend State and local money

in a certain school for a certain purpose, how can you call it

supplanting if you now spend Federal Title I money in that school

for that purpose. You cannot supplant what you have not spent." 6

Nevertheless, South Carolina is using Title I money illegally to

compensate for years of neglect of black schools. These expendi

tures probably improve the schools attended by poor black chil-

17

dren, but if State and local funds had been used, Title I money

could have been directed to the educational handicaps they suffer.

School statistics from the State of MISSISSIPPI also illustrate

supplanting of State and local funds. The per-pupil expenditure

from State and local sources is greater in non-Title I schools than

it is in Title I schools virtually everywhere in the State. Non-Title

I schools (usually white) have more teachers per student than

Title I schools (usually black). In COAHOMA <::OUNTY, for

example, in the 1967-68 school year, non-Title I schools received

$324.71 from State and local funds and Title I schools received

only $175.00.7 The QUITMAN COUNTY, MISSISSIPPI Superin

tendent testified in Federal Court that the highest per-pupil ex

penditure for black schools in his district was about half that of

the lowest per-pupil expenditure in white schools and that Title I

was going into black schools in an effort to equalize expenditures.8

Mississippi's Title I allotment is going almost exclusively to black

schools and is being used to build and equip cafeterias and libraries,

to hire teachers, and to provide instructional materials and books

long available to white students.

However, the use of Title I funds to supplant State and local

funds is not just a Southern practice. Many Northern school dis

tricts also have disparate per-pupil expenditure between schools

and use Title I funds in poverty-area schools to provide programs

and services already provided in schools in more affluent areas.

The MICHIGAN State Department of Education published a

school finance study in 1968 which showed that the level of ex

penditures in a school was related to the socioeconomic level of the

students who attended the school, as measured by the major occu

pation of the father, the family income, and the type of housing.

The more poor children in a school, the less was spent on that

school. The study found that the level of expenditures in a school

was related not only to the provision of special classes for aca

demically advanced children, but also to the provision of remedial

services for children who could not benefit from the regular school

program. Michigan schools with higher per-pupil expenditures em

ployed more remedial reading teachers, librarians, and art teachers,

and utilized more innovative education methods than schools with

a lower per-pupil expenditure.9 It is for these same kinds of

remedial services and extra personnel that Title I funds are so

18

often used. While we do not know precisely how much Title I

money supported reading programs and supportive personnel in

Michigan, such expenditures usually constitute a major proportion

of Title I programs. In four out of five of the local district projects

in Michigan which we examined, a major feature of the Title I

program was reading and language arts. Reading teachers, reading

specialists, and reading materials were funded in the schools en

rolling the largest number of children from low-income families in

each district.

Assuming the Funding of Programs

Previously Supported by State and Local Funds

Another kind of supplanting of State and local funds occurs

when local school systems use Title I money to support programs

and services which were paid for by local funds before Federal

money became available, or to provide identical services to all

schools but charge Title I for these services in target schools. HEW

auditors have uncovered numerous examples of such illegal use of

Title I.

• The ALTOONA AREA SCHOOL SYSTEM in PENNSYL

VANIA used $66,9 15 of Title I funds to help expand and extend

an existing district-wide audio-visual system. The cost of the project

in target schools was charged to Title I. The HEW audit report

noted, "[W]hen an expenditure is made to serve general educa

tional purposes for all children and at the same time to serve ...

educationally deprived children, then charging Title I with that

part of the cost of the program that is applied to low-income chil

dren [penalizes those children] with respect to the amount of State

and local funds used for them which is contrary to the provisions

of the Act." 10

• In CHICAGO, the Board of Education budget provided for

the acquisition of mobile classrooms to be financed with the

proceeds from the sale of a city-owned college. However, the

$1,151,315 cost of the mobile classrooms was charged to Title I

instead. In the 1966-67 school year, the Chicago Board of Edu

cation charged $56,138 in teachers' salaries to the After-School

Program, a Title I project. For the same period, HEW auditors

found a decrease in Chicago's own budget for the program of

$56,138. Moreover, some teachers assigned to the Teaching Eng-

19

lish as a Second Language Program in District 26 in Chicago were

being used as substi tute tea_chers.11

• In MILWAUKEE, HEW auditors found that 1966 Title I ex

penditures, totalling $43,653, included charges for teachers salaries

and related fringe benefits previously borne by the school district.12

• The DETROIT Board of Education was enrolled in a program

with the Midwest Program on Airborne Television Instruction for

several years prior to Title I and had extended its membership

through fiscal year 1967. Even though the television commitment

was made before Title I began, the Board charged $266,649 of

the television costs to Title I for fiscal years 1966 and 1967.13

• The COLUMBUS, OIDO school system spent $195,551 of

Title I funds to construct additional classrooms at six schools. The

school board had previously committed local funds for the con

struction, but on "May 3, 1966, the Board cancelled encumbrances

of bond funds . . . and authorized, instead, the encumbrance of

ESEA Title I funds." Contracts for construction of four of the six

schools were awarded prior to the date that the State approved the

project.14

• CINCINNATI, OHIO utilized $44,335 of Title I funds to

supplant State and local funds. Bids for the construction of portable

classrooms at eight schools were let between March 30 and April 1,

1966. No Title I project for construction was presented to the State

prior to the opening of bids. Then on May 9, the School Board

passed a resolution to finance construction at two schools with

Title I money.15

• In ROCKFORD, ILLINOIS and in MARSHALL COMMU

NITY UNIT SCHOOL DISTRICT in ILLINOIS, Federal audi

tors found that certain salaries of district personnel had been

charged to the Title I program even though these positions had

been in existence prior to Title I.16

• In FRESNO, CALIFORNIA, HEW auditors disclosed that the

school district spent "$24,640 of fiscal year 1967 funds to pur

chase and install television antenna systems in nine target area

schools and the . . . administration building while at the same

time used local funds to provide the same systems in fifteen non

target area schools." 17

• HEW auditors discovered that the DETROIT CITY SCHOOLS

charged to Title I a percentage of the overhead costs of the school

20

system which would have been incurred even if the district had not

participated in Title I. The audit report concluded that Detroit

overcharged Title I to the extent of $1.3 million in fiscal year 1966

and that similar overhead costs of $2 million were charged to Title

I in fiscal year 1967 .1s

Title I and Other Federal Programs

Title I is frequently used to provide food services to hungry

children. In fiscal year 1968, $32 million (or 2.9 percent of total

Title I expenditures) was spent on food services, $25 million of it

in the 17 Southern and Border States.

The poor coordination of Federal programs at all levels of gov

ernment and lack of imagination, particularly in State educational

agencies, have resulted in approval of Title I money for projects

which could have been funded from other underspent budgets.

One deplorable example is the inadequate coordination of Title

I with the Nationa1 School Lunch Program administered by the

Department of Agriculture (USDA) through State educational

agencies. Using Title I funds to provide breakfasts, lunches or

snacks for hungry children is entirely within the intent of the law

and may help improve their academic performance. Until the

National School Lunch Program more effectively reaches all needy

pupils, school districts are justified in including food service in

their Title I projects. However, States must be challenged if they

use Title I funds for food service when other money is available.

A special Congressional appropriation, commonly referred to as

"Perkins Money," 19 was allocated in fiscal 1969 to the States for

expansion of school breakfast and lunch programs for needy chil

dren, and for purchase of equipment in schools without facilities for

food service. In the absence of specific guidelines from USDA con

cerning how the $43 million Perkins funds should be used, State

educational agencies exercised broad discretion in disbursing the

funds among school districts. Strikingly, some States returned sub

stantial percentages of their Perkins allocation while using Title I

funds for food service. For example, Arkansas spent $2,488,915 of

Title I funds in fiscal year 1968 for food services and returned

$443,515 (or 43 percent) of its Perkins money.

States with large numbers of needy children should have ex

hausted all available funds to expand feeding programs. When

21

unable to do so quickly enough, Perkins money should have been

used first because it was available only for food service. Yet some

States returned Perkins money and used Title I money for food

services. The table below compares the amount of Perkins money

returned with the amount of Title I money expended for food

services. Although the years are not comparable, we have no reason

not to believe that States were spending comparable amounts of

Title I funds on food in fiscal year 1969 as they were in fiscal year

1968.20

Amt. Title I

Amt. Perkins % Perkins Money Spent On

Money Returned Money Returned Food Service

State FY 69 FY 69 FY 68

Arkansas $443,515 43% $2,512,818

Delaware 51,361 80 % 127,301

Louisiana 336,828 25 % 198,203

Missouri 285,670 28 % 408,235

Montana 30,051 25 % 64,003

New York 350,900 18 % 854,542

Nevada 14,748 50% 21,192

Pennsylvania 578,971 37% 663,085

Virginia 159,478 9% 1,471 ,544

We recognize the difficulty of using Federal funds efficiently

when they become available after the school year begins, and when

they come to a State agency through different programs. However,

much improvement is possible, and a greater burden rests on the

States to create the machinery necessary for planning, coordination

and technical assistance to school districts. Effective machinery to

do this job is sadly lacking in many States.

Title I money also lacks coordination with Title II ESEA which

provides funds for school library resources, textbooks, and other

instructional materials. Fifty mill!on dollars was allotted to school

districts in fiscal 1969 under this legislation. We have indications

that Title II money may be used in some school districts exclu

sively in non-Title I schools while Title I is spent in target schools

for identical items.

When community groups complain that they cannot determine

where the Title I money is going in their school system, it is often

because so much of the money is used as general aid and in place

of other funds.

22

IV

CONSTRUCTION AND EQUIPMENT

While Title I Regulations do not prohibit the use of money for

construction purposes or for the purchase of equipment, construc

tion (or the rental of space or purchase of mobiles) and the pur

chase of equipment must be clearly related to a specific Title I

project and essential to its successful implementation. The con

struction of permanent facilities is considered the responsibility of

local districts and is permissible only in cases of extreme hardship.

The purchase of equipment is permissible only if the local district

does not already have similar equipment in its own inventory.1

The Office of Education has said that no more than 10 percent

of a State's expenditures should be approved for construction

projects. Its attempt to set a limit of 6.393 percent on the purchase

of equipment was removed by Congressional action. 2 Such restric

tions on the use of Title I are necessary to ensure that school sys

tems do not spend money on hardware to the detriment of instruc

tional programs. The Title I National Advisory Council found in

its evaluation of several compensatory programs that large amounts

of equipment were not a necessary ingredient of a successful pro

gram.3

Despite these provisions, many districts spend Title I money on

the construction of regular school facilities and purchase excessive

amounts of equipment, and State approval of these projects violates

the Regulations and Program Criteria. The largest expenditures for

equipment and construction came in the first year of Title I when

almost one-third ($305 million) of the entire nation-wide expendi

ture was for equipment and construction. There are several reasons

23

to account for this. In the first place, Congress did not appropriate

money until after the school year had begun. It was then late to

spend much of the money, to hire personnel or to put together a

program. Many districts therefore simply spent their allocation on

buildings and huge inventories of equipment. It is also likely that

initially local and State school officials may not have understood

clearly what constituted allowable expenditures under the new Act.

No doubt many financially hard-pressed districts saw an opportu

nity to make much-needed purchases. And in the South , some

school systems, facing possible cut-off of funds because of their

unwillingness to submit an acceptable desegregation plan, pur

chased large amounts of hardware that would remain in the district

after funds were terminated.

The amount of money spent on construction and equipment has

declined sharply since the first year. Nationwide Title I expendi

tures in these categories accounted for only 9.8 percent in 1968.4

Some States have reported a drop in the amount spent and indi

cated that they were rarely approving projects for large expendi

tures on equipment or the construction of facilities. The decline in

such expenditures is probably explained by the comment of one

State official that the local districts had purchased all the equipment

they would need for years to come. But many_ States have not de

creased the amount of Title I funds spent for construction and

equipment. For fiscal year 1968, MISSISSIPPI spent 30 percent

of its Title I allocation for these two items.5

While levels of expenditures in each State may now be within

acceptable limits, local districts have continued to spend Title I

money to construct regular school facilities, and to purchase exces

sive amounts of equipment in violation of Federal Regulations and

Program Criteria. Some of these projects may well have benefited

children from low-income families, but many of these expenditures

probably deprived these same children of much-needed instruc

tional programs and additional personnel.

Construction

• The DETROIT, MICHIGAN Board of Education purchased

the Temple Baptist Church, with $1.4 million of Title I funds, to

house Title I administrative offices and activities. HEW auditors

found, however, that "only a small portion" of the space was

24

actually utilized for Title I projects and that "The greatest bene

factor to date appears to have been the Temple Baptist Church

Congregation" which continued to use the building in the evenings

and on the weekend. The church space was "substantially in excess

of that needed to accomplish the objectives of Title I. ... " 6

Title I funds have been used to strengthen the dual school system

despite Federal requ irements that projects should be conducted in

ways which eliminate racial, social, or linguistic isolation of chil

dren. In 1967, the Commission on Civil Rights pointed out that

Title I money was being used to perpetuate racial segregation.7

But the Commissioner of Education has never expressly forbidden

the use of Title [ funds for the construction of racially separate

facilities.

• In YAZOO COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, MISSISSIPPI,

HEW investigators found that Title I money was used to perpetuate

segregation. Funds were used to renovate completely a dilapidated

three-room black school located in a cotton field. Six portable units,

including a lunchroom purchased with Title I funds , were added to

the school, and covered walkways were built to connect the many

portables. The result was a trailer school. At a second black school,

Title I built a new library and new classrooms, and portables, con