DeFunis v. Odegaard Brief Amicus Curiae of the National Conference of Black Lawyers

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. DeFunis v. Odegaard Brief Amicus Curiae of the National Conference of Black Lawyers, 1973. 6af26089-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9f1cbefe-9929-4d7b-b11a-85f3064ccffa/defunis-v-odegaard-brief-amicus-curiae-of-the-national-conference-of-black-lawyers. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

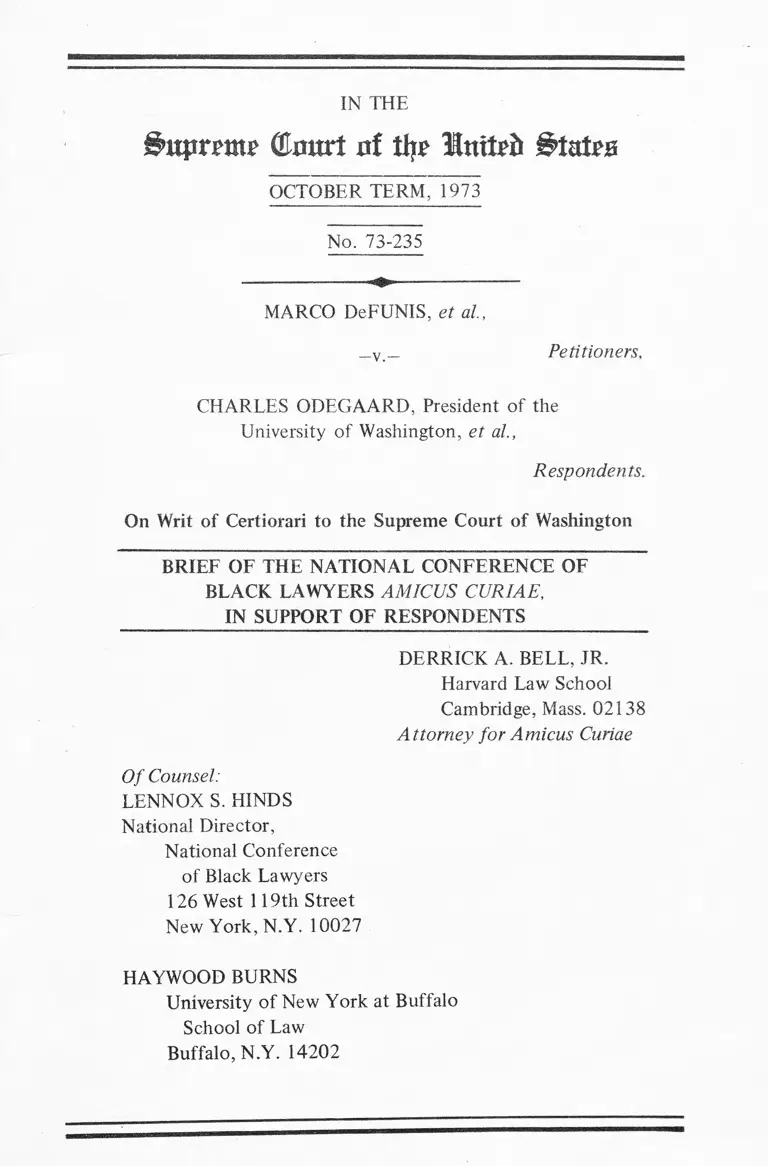

IN THE

£>uprm? (Hmtrt nf % Initeii States

OCTOBER TERM, 1973

No. 73-235

MARCO DeFUNIS, et al.,

_ v._ Petitioners.

CHARLES ODEGAARD, President of the

University of Washington, et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Washington

BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF

BLACK LAWYERS AMICUS CURIAE,

__________IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS____________

DERRICK A. BELL, JR.

Harvard Law School

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

Attorney for Amicus Curiae

Of Counsel:

LENNOX S. HINDS

National Director,

National Conference

of Black Lawyers

126 West 119th Street

New York, N.Y. 10027

HAYWOOD BURNS

University of New York at Buffalo

School of Law

Buffalo, N.Y. 14202

INDEX

PAGE

Interest of the Amicus

Consent to Filing 2

Opinions Below .

Question Presented

3

3

Statement of the Case 3

Summary of Argument ......................... ... 6

Argument ........................................................................... 7

The respondent law school’s minority-admis

sions policy is a constitutionally appropriate

effort to remedy the effects of long-standing

racial discrimination in the legal profession.

I. Some consideration of race is necessary to

remedy disadvantages imposed because of race • 8

II. A judicial finding of racial discrimination is not

a condition precedent to adoption of a valid

minority admissions program .................................... 10

III. Respondents’ minority admissions plan is not

rendered invalid because it alters expectations

rooted in societal patterns that perpetuate racial

inequality ............................................................. 11

IV. The historic exclusion of racial minorities from

the legal profession justified respondents’ af

firmative efforts to attract qualified minority

applicants.................................................................... 17

Table of Authorities

Alabamav. United States, 371 U.S. 37 ( 1 9 6 2 ) .................. 15

Allen v. Asheville City Board o f Education,

434 F.2d 902 (4th Cir. 1970) ........................................ 13

Anderson v. San Francisco Unified School District,

357 F. Supp. 248 (N.D. Cal. 1 9 7 2 ) ................................ 13

Associated General Contractors o f Massachusetts,

Inc. v. Altshuler,_F.2d__, 42 U.S.L.W. 2320

(Dec. 25, 1 9 7 3 ) ................................................................. 17

Baker v. Columbus Municipal Separate School District,

462 F. 2d 1112 (5th Cir. 1972) .................................... 15

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776

(E.D. S.C. 1955) 8

Brown v. Board o f Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954) 3,8,17,18

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971) . . . . 9

Chance v. Board o f Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167

(2d Cir. 1972) 15

Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe,

401 U.S. 402 (1971) 16

Contractors Association o f Eastern Pennsylvania v.

Secretary o f Labor, 442 F.2d 159

(3d Cir. 1971) ............................................................. • 9

Dandridge v. Williams, 397 U.S. 471 ( 1 9 7 0 ) ...................... 16

Deal v. Cincinnati Board o f Education,

369 F.2d 55, 61 (6th Cir. 1966) .................................... 10

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 82 Wn. 2d 11, 32-33, 507 P.2d

1169, 1182 (1973) 20,23

Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 Flow.)

393 ( 1 8 5 7 ) ........................................................................ 18

Cases: PAGE

Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board o f Control,

350 U.S. 413 (1956) ...................................................... 21

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969) . 9,15

Green v. County School Board o f New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) ...................................................... 8

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) . . . . 9,15

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915) .................. 15

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401,

476-88 (D. D.C. 1 9 6 7 ) ...................................................... 15

Hunt v. Arnold, 172 F. Supp. 847 (N.D. Ga. 1959) . . . . 15

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colo.,

413 U.S. 189,217 (1973) ...............................................12

Lee v. Nyquist, 318 F. Supp. 710 (W.D. N.Y. 1970),

a ff’d, 402 U.S. 935 (1 9 7 1 ) ............................................... 10

Local 53, Intern. Assoc, o f Heat and Frost Insulators

and Asbestos Workers v. Vogler,

407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969) .................................... 16

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers,

AFL-CIO v. United States, 416 F.2d 980

(5th Cir. 1969) ................................................................. 12

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 ( 1 9 6 5 ) .............. 15

Mancari v. Morton, 359 F. Supp. 585 (D. N.Mex. 1973) . 11

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184, 192 (1964) . . . . 7

Meredith v. Fair. 305 F.2d 343, 351-354 (5th Cir. 1962) . 15

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U.S. 337 (1938) ...................................................... 21

North Carolina State Board o f Education v. Swann,

402 U.S. 43 (1971) ......................................................... 10

Northcross v. Board o f Education o f Memphis,

466 F.2d 890, 898 (6th Cir. 1972).................................... 12

ii

PAGE

PAGE

Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Board o f Education,

423 F.2d 121 (2d Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ........................................... 13

Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency,

395 F.2d 920, 931-32 (2d Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) ............................. 9

Offerman v. Nitkowski, 378 F.2d 22 (2d. Cir. 1967) . . . 10

Otero v. New York City Housing Authority,

__F .2d _ ,42 U.S.L.W. 2185 (Oct. 9, 1 9 7 3 ) .................. 14

Porcelli v. Titus, 431 F.2d 1254 (3d Cir. 1970) ...............10

San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez,

93 S. Ct. 1278, 1301-02 (1973) .................................... 16

Schnell v. Davis, 336 U.S. 933 ( 1 9 4 9 ) ................................ 15

Simmons v. Eagle Seelatsee,

244 F. Supp. 808 (E.D. Wash. 1965),

a ff’d per curiam, 384 U.S. 209 (1966).............................10

Sipeul v. Bd. o f Regents o f Univ. o f Oklahoma,

332 U.S. 631 (1948) . . . . . .................................... 21

Springfield School Comm. v. Barksdale,

348 F.2d 261,266 (1st Cir. 1965) ................................ 10

State ex rel. Citizens Against Mandatory Bussing

v. Brooks, 80 Wash. 2d 121,492 P.2d 536 (1972) . . . 13

Swann v. Chariotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1 9 7 1 ) ......................................................... 8,10

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) ............................. 21

Tometz v. Board o f Education, Waukegan City,

39 111. 2d 593, 237 N.E.2d 498 (1968) ......................... 10

T. V. 9, Inc. v. F.C.C.,

_ F .2 d _ , 42U.S.F.W. 2245 (Nov. 13, 1 9 7 3 ) .............. 11

United States v. Jefferson County Board o f

Education, 372 F.2d 836, 876-77 (5th Cir. 1966) . . . 9

United States v. Montgomery County Board o f Education,

395 U.S. 225 (1969) ...................................................... 8

iii

IV

University o f Maryland v. Murray, 169 Md. 478,

182 A. 590 (1936) 21

Other Authorities:

Anderson, The Admissions Process in Litigation,

15 Ariz. L. Rev. 81 (1 9 7 3 ) ............................................... 16

Association of American Law Schools, 1973 Survey o f

Minority Group Students in Legal Education

(Dec. 1 9 7 3 ) ......................................................... 21

Bell, Black Students in White Law Schools: The Ordeal

and the Opportunity, 1970 Toledo L. Rev. 539 . . . 17,21

P. Bergman, The Chronological History of the Negro in

America, 221 (1969) . .......................................................18

B. Bittker, The Case for Black Reparations 120 (1973) . . 8

Brown, The Genesis o f the Negro Lawyer in New England,

22 The Negro Hist. Bull. 147, 148 ( 1 9 5 8 ) ..................... 18

Carl and Callahan, Negroes and the Law,

17 J. Legal Ed. 250 (1 9 6 5 ) ............................................... 21

M. Davie, Negroes in American Society 115-16 (1949) . 19,20

Edwards, The New Role for the Black Law Graduate: A

Reality or an Illusion? 69 Mich. L. Rev. 1407,

1432 (1971) 22

Gellhorn, The Law Schools and the Negro,

1968 Duke L.J. 1070. n. 1 3 .................................................. 20

J. Greenberg, Race Relations and American Law

260-69 (1959) 21

W. Grier and P. Cobbs, Black Rage ( 1 9 6 8 ) ......................... 17

A. Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X,

36-37 ( 1 9 6 4 ) .................................................................... 20

Hughes, Reparations for Blacks? 43 N.Y.L.J.

1063,1072(1968) 12

Kagan, The IQ Puzzle: What Are We Measuring? No. 14

Inequality in Education, 5 (Jul. 1973) 15

PAGE

V

A. Kardiner and L. Ovesey, The Mark of Oppression (1962) 16

J. Kovel, White Racism: A Psychohistory (1 9 7 0 ) .............. 16

Leonard, The Development o f the Black Bar,

407 The Annals 134, 136 (May, 1973) ..................18,19

McGee, Black Lawyers and the Struggle for Racial

Justice in the American Social Order,

20 Buffalo L. Rev. 423 (1971)........................................... 20

Morris, Equal Protection, Affirmative Action and

Racial Preferences in Law Admissions: DeFunis v.

Odegaard, 49 Wash. L. Rev. 1,4-5,

notes 1 4 -1 5 ......................................................................22,23

Note, Negro Members o f the Alabama Bar,

21 Ala. L. Rev. 309 (1969) ........................................... 21

Note, Race Quotas, 8 Harv. Civ. Rights-Civ. Lib.

L. Rev. 128 (1973) 9

Parker and Stebman, Legal Education for Blacks,

407 The Annals 144 (May 1 9 7 3 ) .................................... 22

Ramsey, Law School Admissions: Science, Art or Hunch?

12 J. Legal Ed. 503, 517 (1960) .................................... 15

R. Rosenthal, L. Jacobson, Pygmalion in the

Classroom ( 1 9 6 8 ) ............................................................. 15

Schrader, Pitcher, Predicting Law School Grades for

Black American Law Students, Law School Admission

Council (Mar. 1 9 7 3 ) ......................................................... 15

Shuman, A Black Lawyer Study, 16 Howard

L.J. 3 0 4 (1 9 7 1 ) ................................................................. 20

Stevens, Two Cheers for 1870: The American Law School

in Law in American History, 405, 428, n. 16

(D. Fleming and B. Bailyn eds. 1 9 7 1 ) .................................19

United States v. Georgia, No. 30, 388 (5th Cir. 1971),

Amicus Curiae brief for the National Educational

Association at 920-21 14

Wechsler, Toward Neutral Principles o f Law,

73 Harv. L. Rev. 1, 15, 3 1 -3 4 (1 9 5 9 ) ............................. 12

PAGE

IN THE

^hiuthu' tourt nf % lltttteii States

OCTOBER TERM, 1973

No. 73-235

MARCO DeFUNIS, et al.,

Petitioners,

— v . ~

CHARLES ODEGAARD, President of the

University of Washington, et al,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Washington

BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF

BLACK LAWYERS AMICUS CURIAE,

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

Interest of the Amicus

The National Conference of Black Lawyers (NCBL) is an

incorporated association of approximately 500 black lawyers

in the United States and Canada, and 2,500 law students

affiliated with NCBL through their membership in the Black

American Law Student Association (BALSA).

Since its inception in December of 1968, NCBL, through

its national office, local chapters, co-operating attorneys and

the BALSA organization, has (1) carried on a program of

litigation, including defense of the politically unpopular and

affirmative suits on community issues; (2) monitored govern

mental activity that affects the black community, including

2

judicial appointments, and the work of the legislative, execu

tive, judicial and administrative branches of government; and

(3) served the black bar through lawyer referral, job place

ment, continuing legal education programs, defense of advo

cates facing judicial and bar sanctions, and watchdog activity

on law school admissions and curriculum.

The latter activity is of crucial importance. Despite the

progress made as a result of law school programs such as that

under attack here, the number of black and other minority-

group lawyers remains seriously short of the need. The legal

representation available to most black people remains either

non-existent or inadequate.

For example, NCBL attorneys have been involved in the

cases of black activist individuals and groups who, despite

their racially-connected difficulties, were deemed ineligible for

legal assistance by the nationally-recognized civil rights organi

zations. Offering them an alternative to “radical” lawyers,

NCBL has provided technically sound, sympathetic repre

sentation to, inter alia, Angela Davis, Martin Sostre, H. Rap

Brown, the Cornell Students, the Republic of New Africa,

and the Attica Inmates.

Minority-group lawyers have a unique role to play not

merely in representing activists, but in implementing the civil

rights statutes and decisions gained during the past genera

tion. The nation’s law schools, after much thought and

experimentation, have evolved sound programs designed to

identify and train minority lawyers qualified to perform these

tasks. NCBL joins the many groups who urge this Court that

these programs are vitally necessary, educationally appro

priate, and constitutionally sound.

Consent to Filing

This Amicus Curiae brief is filed with the written consent

of counsel for the parties in this proceeding.

3

Opinions Below

The opinion of the trial court, Superior Court of the State

of Washington, County of King, is not reported. The opinion

of the Supreme Court of Washington is reported in 82 Wn.

2d 11, 507 P. 2d 1169.

Question Presented

Whether a state law school’s admissions policy that takes

cognizance of race to insure fair consideration of minority

group applicants and remedy their past exclusion from the

legal profession violates the Constitution where such policy is

voluntarily adopted rather than judicially ordered to correct

proven discriminatory practices.

Statement of the Case

Petitioner DeFunis is white. He sought and failed to gain

admission to the respondent law school in both 1970 and

1971 (St. 13, 22). In the wake of his second rejection, he

filed suit in state court alleging that the school’s admissions

policies discriminated against him by granting admission to

veterans, nonresidents and members of disadvantaged minor

ity groups, many of whom he alleged presented credentials

and qualifications inferior to his own (App. 12-15).

The trial court, despite voluminous and uncontroverted

testimony that the admissions procedure utilized by the

respondent law school contained both quantifiable and non-

quantifiable factors, concluded that entitlement to admission

was equatable with mechanical credentials, i.e. , a numerical

predictor of first-year performance obtained by a formula

utilizing a portion of an applicant’s undergraduate grades and

the score obtained on a nationally-standardized Law School

Admissions Test (LSAT). Interpreting Brown v. Board o f

Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), as a bar to any considera

tion of race, the lower court held that the admission of

4

minority students with lower prediction averages violated

petitioner DeFunis’s rights under the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment. The admission of veterans

and non-residents, most of whom were white, and many of

whom held prediction averages lower than petitioner’s was,

the lower court found, not based on race, and thus was

“quite proper” (App. 57).

The respondent law school selected its 1971 first-year class,

limited to 150 students, from a record-high total of 1,601

applicants (St. 334-35), at least half of whom could probably

do “good work at the University of Washington.” (St. 155).

Balancing grades and test scores with evidence of “ability to

make significant contributions to law school classes and to

the community at large” (Ex. 45), the Admissions Committee

sought to select a diverse range of talented male and female

students from a variety of geographical, academic, social-class

and racial backgrounds (St. 31, 218, 360-61).

The committee admitted most (St. 340) but not all

applicants with a combined LSAT and grade-point prediction

average above 77 (St. 343, 406), and rejected most but not

all applicants with scores below 74.5 (St. 341-42). Applicants

with averages between these two figures, including petitioner,

were assumed capable of performing law school work, and

were classified according to an evaluation of their transcripts

and a review of non-numerical evidence of potential in letters

of recommendation, the applicant’s statement and record of

achievement (St. 338-39). All minority applicants were simi

larly reviewed (St. 341-42, 399). Forty-four minority appli

cants were admitted, 18 of whom subsequently enrolled

(App. 50). Six of those admitted had higher prediction

averages than DeFunis (App. 52). Thirty-six had lower

averages than did petitioner (App. 50), but so did 38 white

admittees, including 22 returning from the military, and 16

5

deemed worthy of invitations based on other information in

their files (Ex. 44). Of the 311 students admitted, 224 had

higher prediction averages than petitioner (St. 366-67).

University of Washington President Odegaard testified that

the special attention given minority-group applicants by the

Admissions Committee accorded with a University-wide

policy (St. 108-09, 416) adopted in 1963 when school

officials realized that an “open door” at the point of entry to

the University was not enough, in view of the cultural

conditions and the separation of minority students from

conventional backgrounds, to alter the virtually all-white

composition of the University’s student body (Tr. 223-24).

The President (St. 241-43), as well as law school officials

(St. 163-64), consistently denied that giving increased weight

to evidence obtained from the background of minority appli

cants with lower grade and test score credentials to ascertain

motivation and the capacity to overcome previous dis

advantages (St. 242) constituted a lowering of standards or

qualifications. They pointed out that greater reliance could be

placed on other criteria in evaluating minority applicants. For

example, successful completion of the pre-law program spon

sored by the Council on Legal Education Opportunity

(CLEO) serves as a reliable predictor of law school perfor

mance (St. 90, 121-25).

University of Texas Law School Professor Millard Ruud, a

consultant on legal education to the American Bar Associa

tion (St. 119-20), explained that the LSAT was “exceedingly

important” as a predictor of law school performance, but he

warned that it is not a “precise measure” like “an apothecary

scale,” and “no substitute for human judgment and evalua

tion.” (St. 128). With minority students, he testified “that

there is a greater need for exercise of judgment of looking at,

6

examining the transcript, examining all other data . . . (St.

129). An LSAT official supported Professor Ruud’s state

ments, characterizing tire LSAT as an interpretive rather than

a precise predictive tool (St. 184), that alone will not provide

an accurate indication of law school potential (St. 197-98).

Respondents uniformly maintained that they sought, not a

racial quota (St. 353, 420), but a “reasonable representation”

of minority-group students in the 1971 class (St. 416,

426-27). They asserted their aim was not to discriminate

against petitioner DeFunis, but to further the University’s

goal of assisting historically suppressed and excluded minor

ities into the mainstream of society (St. 416), and improve

the educational environment of the law school (St. 418). The

special procedures given minority applications, adopted after

the University’s “open door” policy failed to produce results,

were justified by President Odegaard because color-blind

admissions function “to deprive segments of American society

from opportunities that other segments of society have and

that something more than a sanitized mechanical system is

required to solve this problem in finding the true potential of

individuals.” (St. 243).

A majority of the Supreme Court of Washington concluded

that the respondents’ consideration of race in admitting

students was necessary to the accomplishment of a compel

ling state interest.

Summary of Argument

Legislative and judicial declarations of racial equality do

not automatically eradicate conditions and remedy depriva

tions that led to their promulgation. Meaningful implementa

tion requires adoption, usually under a specific legal mandate,

of color-conscious corrective policies designed to provide

those excluded by race with the opportunity to compete on

an equal basis for the places from which they were excluded.

7

But a state law school, cognizant of the historic exclusion

of minority groups from he legal profession, may voluntarily

adopt a modest affirmative action admissions program rea

sonably intended to ameliorate past exclusionary patterns

without violating the rights of non-minority applicants whose

chances for admission may be lessened by such programs.

ARGUMENT

The respondent law school’s minority-admissions policy is a

constitutionally appropriate effort to remedy the effects of

long-standing racial discrimination in the legal profession.

The National Conference of Black Lawyers, along with

black people generally, fervently hope that a time will come

when all affirmative action admissions policies can, by the

application of equal protection standards carefully developed

by this Court, be held unconstitutional.

The central purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was to

eliminate official racial discrimination, and to realize that

purpose, this Court has scrutinized with great care state-

imposed racial classifications, deeming them “constitutionally

suspect,” . . . and subject to the “most rigid scrutiny” . . .

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184, 192 (1964). it is not

clear that the Court intended to apply this standard to efforts

clearly intended to redress racially discriminatory conditions

as well as to those laws that subordinated blacks and other

minorities on the basis of race. In any event, amicus curiae

hope a time will come when black law school applicants will

not have experienced racial discrimination in the form of,

inter alia, inferior public schools and racially limited employ

ment and housing opportunities. They will have overcome

societal handicaps sufficiently to present grades and test

scores in ranges indistinguishable from those offered by

whites. The percentage of black law students in the schools

and lawyers in the profession will then approximate the

percentage of their white counterparts. At that time, blacks

will no longer need an affirmative action program, and its

adoption by a law school might well be found unconstitu

tional.

Unfortunately, the minority applicants who applied for

admission to respondents’ law school in 1971 were not born

in a racism-free society. A century after enactment of the

Fourteenth Amendment, and a generation after Brown v.

Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), the transition

from the status of slaves to the equality of opportunity

enjoyed by white citizens is still underway. To assume, as the

trial court did, that this Court’s decisions enunciating the

rights of blacks to racial equality requires no compensatory

remediaton confuses signposts to a goal with the goal itself.

I. Some consideration of race is necessary to remedy disad

vantages imposed because of race.

Resistance to desegregation plans, including charges that

such plans discriminate against whites, have marked virtually

every step taken to secure equality of opportunity to racial

minorities. Courts have heard and generally rejected such

charges, recognizing with one legal scholar “that we can have

a color-blind society in the long run only if we refuse to be

color-blind in the short run.” B. BITTKER, THE CASE FOR

BLACK REPARATIONS 120 (1973).

The facile doctrine that “The Constitution . . . does not

require integration. It merely forbids discrimination.” Briggs

v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E.D.S.C. 1955), has been

rejected in school desegregation cases. Green v. County

School Board o f New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968);

United States v. Montgomery County Board o f Education,

395 U.S. 225 (1969); Swann v. Chariotte-Mecklenburg Board

o f Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971). The use of culturally biased

standardized tests and unvalidated employment qualifications,

9

despite their superficial appearance of fairness, have been

characterized as “built-in headwinds” for minority groups in

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971). Voting

requirements have been struck down when their effect was to

burden minorities handicapped by the effects of prior state-

supported discrimination. Gaston County v. United States,

395 U.S. 285 (1969).

In each of these major decisions, the standard of effecting

remedy is keyed to recognition of race, and lower courts,

relying on these standards, have approved or ordered racial

classifications to avoid or eliminate racial inequality. “Where

it is drawn for the purpose of achieving equality it will be

allowed, and to the extent it is necessary to avoid unequal

treatment by race, it will be required.” Norwalk CORE v.

Norwalk Redevelopment Agency, 395 F. 2d 920, 931-32 (2d

Cir. 1968). See also, United States v. Jefferson County Board

o f Education, 372 F. 2d 836, 876-77 (5th Cir. 1966). Racial

classifications, including racial percentages and quotas have

been approved to correct racial discrimination in literally

hundreds of civil rights cases. Note, Race Quotas, 8 HARV.

CIV. RIGHTS-CIV. LIB. L. REV. 128 (1973).

In the area of employment discrimination, Carter v. Gal

lagher, 452 F. 2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971), is one of a series of

cases requiring police and fire departments to hire one

qualified minority person for every three whites until a

certain percentage of minority persons has been hired, even if

more qualified non-minority candidates must be bypassed.

And in the “hometown plan” cases, Contractors Association

o f Eastern Pennsyvlania v. Secretary o f Labor, 442 F. 2d 159

(3d Cir. 1971), courts have required builders and construction

unions to meet pre-set levels on minority hiring and training.

10

In school desegregation cases courts have followed the

directions in Swann, supra, regarding racial percentages as

tools to facilitate elimination of prior policies that discrim

inated on the basis of race. Indeed, state statutes attempting

to bar assignment of students on a racial basis have been

declared unconstitutional. North Carolina State Board o f

Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971); Zee v. Nyquist, 318

F. Supp. 710 (W.D. N.Y. 1970), a ff’d, 402 U.S. 935 (1971).

II. A judicial finding of racial discrimination is not a condi

tion precedent to adoption of a valid minority admissions

program.

In most school cases, proof that discrimination has occur

red iis presented, but the authority to order affirmative relief

is not conditioned on judicial findings of responsibility for

the racial deprivation, but on the presence of the deprivation

itself. It is on this basis that courts have upheld voluntary

actions by school boards intended to correct racial imbalance

against challenges by white parents and teachers. Offermann

v. Nitkowski, 378 F. 2d 22 (2d Cir. 1967); Porcelli v. Titus,

431 F. 2d 1254 (3d Cir. 1970), and see several additional

cases discussed in Tometz v. Board o f Education, Waukegan

City, 39 111. 2d 593, 237 N.E. 2d 498 (1968). Even courts

that refused to order school desegregation without proof that

the school board was responsible for the racially-isolated

schools, suggested that the Constitution permitted voluntary

desegregation plans. Deal v. Cincinnati Board o f Education,

369 F. 2d 55, 61 (6th Cir. 1966); Springfield School Comm,

v. Barksdale, 348 F. 2d 261, 266 (1st Cir. 1965).

Often, the deprivation intended to be eased by a racial

classification is societal in scope, not specific or attributable

to a single law or policy. The several laws and decisions

concerning American Indians are an example. See e.g., Sim-

11

mom v. Eagle Seelatsee, 244 F. Supp. 808 (E.D. Wash.

1965), a ff’d per curiam, 384 U.S. 209 (1966), upholding a

federal statute’s racial classification which limited the rights

of inheritance to the Yakima Indian allotments to descen-

dents of “one-fourth or more blood” of the Yakima tribe. Cf.

Mancari v. Morton, 359 F. Supp. 585 (D. N.Mex. 1973),

where the court rules that a federal employment statute

granting a perference to Indians must give way to the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, on a record reflecting

the adverse effect on non-Indians, and no evidence to show

any national-public purpose to be served by the preference

statute.

Consider also TV. 9, Inc. v. F.C.C., _ F. 2d __, 42

U.S.L.W. 2245 (Nov. 13, 1973), in which the Ninth Circuit

held that

“Color blindness in the protection of the rights of

individuals under the laws does not foreclose considera

tion of stock ownership by members of a black minority

where the commission is comparing the qualification of

applicants for broadcasting rights . . . . Inconsistency with

the Constitution is not to be found in a view of our

developing national life which accords merit to black

participation among principals of applicants for tele

vision rights. However elusive the public interest may be

it has reality. 42 U.S.L.W. at 2246.

III. Respondents’ minority admissions plan is not rendered

invalid because it alters expectations rooted in societal pat

terns that perpetuate racial inequality.

In addition to urging the Court not to approve affirmative

action plans unless they remedy past, specific racially dis

criminatory actions, amici briefs supporting petitioner

12

DeFunis argue that such plans may impose no new depriva

tion on other innocent parties such as petitioner. The posi

tion seeks to resurrect the proposition that it should be

possible to remedy racial injustices against blacks without

diluting the privileges and expectations which whites had

hitherto enjoyed. Wechsler, Toward Neutral Principles o f

Law, 73 HARV. L. REV. 1, 15, 31-34 (1959). But whether

intended or not, others did benefit from policies that ex

cluded minorities. Thus, when corrective action is taken, the

impact will be felt by those who enjoyed — however inno

cently — privileges and expectations which belonged to others.

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers, AFL-CIO

v. United States, 416 F. 2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969); Hughes,

Reparations for Blacks? 43 N.Y.L.J. 1063, 1072 (1968).

To suggest as does petitioner that public school desegrega

tion plans are distinguishable because, unlike the case at bar,

no white student is actually excluded from school, demeans

the sincere, if misguided, concern that motivates white

parents to oppose these plans in court, and ignores the

serious consideration courts have given to the resolution of

the competing interests posed by such litigation. There is

sacrifice involved in these cases as even the most committed

integrationist must concede after studying Mr. Justice

Powell’s concurring and dissenting opinion in Keyes v. School

District No. 1, Denver, Colo., 413 U.S. 189, 217 (1973). Or

read Judge Weick’s strong dissent against the busing plan

approved in Northcross v. Board o f Education o f Memphis,

466 F. 2d 890, 898 (6th Cir. 1972).

It is not claimed that these unfortunate children, who

are the victims of induced busing, have committed any

offense. And we are living in a free society in which one

of the privileges is the right of association.

13

The average American couple who are raising their

children, scrape and save money to buy a home in a nice

residential neighborhood, near a public school. One can

imagine their frustration when they find their plans have

been destroyed by the judgment of a federal court.

The elimination of neighborhood schools necessarily

interferes with the interest in and participation by

parents in the operation of the schools through parent-

teachers’ associations, interferes with activities of chil

dren out of school, and interferes with their privilege of

association, and it deprives them of walk in schools. It

can even lower the quality of education. 466 F. 2d at

898. See also, Anderson v. San Francisco Unified School

District, 357 F. Supp. 248 (N.D. Cal. 1972).

The Washington Supreme Court is not unaware of the

dislocations desegregation may cause. In approving a Seattle

voluntary school desegregation plan, the court found the

board could use race as a criterion whether the nature of the

segregation was de jure or de facto, and that busing was

within the authority of school officials despite awkwardness,

inconvenience and other burdens. State ex rel. Citizens

Against Mandatory Bussing v. Brooks, 80 Wash. 2d 121, 492

P. 2d 536 (1972).

Sacrifice incurred during the process of remedying racist

conditions is not limited to whites. The loss suffered by black

children during the long years required to give real meaning

to Brown I, under the “all deliberate speed” standard of

Brown II, is incalculable. Nor have the burdens of implemen

tation been uniracial. Black students have lost community

schools, Allen v. Asheville City Board o f Education, 434 F.

2d 902 (4th Cir. 1970)■, Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Board o f

Education, 423 F. 2d 121 (2d Cir. 1970), and black teachers

14

have lost their jobs, see amicus curiae brief for the National

Educational Association, United States v. Georgia, No. 30,

388 (5th Cir. 1971) at 920-21. Some courts have gone to

shocking lengths to further integration even at the expense of

prior commitments to minority groups. Thus, in Otero v.

New York City Housing Authority, __ F. 2d __ , 42

U.S.L.W. 2185 (Oct. 9, 1973), the Second Circuit held that

the Authority could refuse to rent new housing to displaced

minority-group residents where such rentals would create a

“pocket ghetto” and violate its affirmative duty to integrate

public housing.

The dislocations of desegregation programs suffered by

blacks and whites are an unfortunate concommittant of social

change. They are not equatable with nor do they herald a

return to the restrictive quotas imposed on Jewish students

by some colleges 50 years ago. Contrary arguments in the

amicus brief supporting petitioner’s Jurisdictional Statement

Filed by the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith at 24,

reflect far less faith in this society’s ability to equitably solve

its racial problems than has been exhibited by those blacks

and other minorities who, despite all, are still seeking oppor

tunities for success and achievement now enjoyed by previ

ously victimized religious and ethnic groups in this country.

The fears that moderate plans of racial remediation will

somehow escalate to levels that threaten legitimate interests

because they expressly use race and not some disingenuous

synonym like “cultural disadvantage,” are unwarranted, given

the moderate character of respondents’ plan, which at 1971

enrollment levels will require many decades before the dis

parities in the number of minority lawyers in Washington

state are substantially reduced.

Moreover, the voluntarily-adopted policy of respondents

under review here is no less reasonable, appropriate and

immune to charges of “reverse discrimination” or “racial

15

quota” than were the school plans set forth above. Despite

the efforts by petitioner’s counsel at trial, the Record shows

that law school personnel followed the dictates of their

experience and the instructions from LSAT officials, and

considered the mechanical credentials, grades and LSAT

scores, as important measures in determining qualifications,

and not as the sole criteria for selection.1 There were simply

1 A law school would be, at least, remiss were it to rely heavily on

standardized tests in gauging minority applicants’ qualifications in view

of the past use of tests in civil rights cases. Guinn v. United States, 238

U.S. 347 (1915); Schnell v. Davis, 336 U.S. 933 (1949); Alabama v.

United States, 371 U.S. 37 (1962); Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S.

145 (1965); Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969);

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971); Baker v. Columbus

Municipal Separate School District, 462 F. 2d 1112 (5th Cir. 1972);

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F. 2d 1167 (2d Cir. 1972).

Validation studies thus far undertaken to measure the accuracy of

the LSAT for minority students indicate that it has value as a predictor,

Schrader, Pitcher, Predicting Law School Grades for Black American

Law Students, Law School Admission Council (Mar. 1973), but critics

point out that such tests cannot measure attitude, motivation, ability to

empathize, and other qualities needed in practice. Ramsey, Law School

Admissions: Science, Art or Hunch? 12 J. LEGAL ED. 503, 517

(1960).

At best, they predict first year grades, not law school performance

or professional competence. There is even basis to fear that the

accuracy of first year predictions may be attributable in part to a

self-fulfilling prophecy effect on the student and his teachers. R.

ROSENTHAL, L. JACOBSON, PYGMALION IN THE CLASSROOM

(1968); Kagan, The IQ Puzzle: What Are We Measuring? No. 14

INEQUALITY IN EDUCATION, 5 (Jul. 1973).

To the extent that standardized test scores are “culturally biased” in

favor of white, middle class examinees, Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp.

401, 476-88 (D. D.C. 1967), over-reliance on LSAT scores would

present barriers to minority applicants quite similar to the “alumni

character recommendations” struck down in the college desegregation

cases. Meredith v. Fair, 305 F. 2d 343, 351-354 (5th Cir. 1962); Hunt

16

too many white applicants admitted with lower mechanical

scores than petitioner and too many whites who were denied

despite higher scores to support his position that his rights

were violated because of the admission of minority students

with “lower qualifications.”

The selection process is not a scientifically precise one,

relying of necessity in some degree on intuition rather than

engineering, but it is sufficiently within the standards for

administrative agency action set in cases like Citizens to

Presence Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402 (1971), to earn

judicial respect for its judgment and the reasonableness of its

action, especially in an educational policy question. San

Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriquez, 93 S. Ct.

1278, 1301-02 (1973); Dandridge r. Williams, 397 U.S. 471

(1970). See, Anderson, The Admissions Process in Litigation,

15 ARIZ. L. REV. 81 (1973).

Here, the respondents’ affirmative action policy is correct

as well as reasonable. While several of the minority applicants

presented comparatively low mechanical credentials, they had

completed the CLEO program or had other experiences or

characteristics justifying a decision that they could perform

law school work and contribute to their classes while in

school, and to their communities after graduation. In mea

suring professional school potential of minority applicants, it

is most appropriate to consider the disadvantages and handi

caps that in varying degrees each of them, regardless of their

socio-economic status, has had to overcome. These societal

obstacles have been identified by social scientists, see, e.g. J.

KOVEL, WHITE RACISM: A PSYCHOHISTORY (1970); A.

KARDINER AND L. OVESEY, THE MARK OF OPPRES-

v. Arnold, 172 F. Supp. 847 (N.D. Ga. 1959). Cf. Local 53, Intern.

Assoc, of Heat and Frost Insulators, and Asbestos Workers v. Vogler,

407 F. 2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969).

17

SION (1962); W. GRIER AND P. COBBS, BLACK RAGE

(1968), and recognized by this Court. Brown v. Board o f

Education, supra.

The reasonableness of respondents’ minority admissions

program is not weakened by suggestions that it is patronizing

to minorities. Indeed, such a characterization might more

readily fit the respondents’ refusal to adopt such a program

since such refusal would imply that the absence of minority

law students was due to shortcomings generic to the group

rather than the deprivations of opportunity unfairly placed

on them by society.

Minority students are not stigmatized by respondents’

admission policies, although the adjustment difficulties may

exceed those of their white classmates. Bell, Black Students

in White Law Schools: The Ordeal and the Opportunity,

1970 TOLEDO L. REV. 539. But the Constitution does not

guarantee, nor do minority students seek, a “free ride”

through law school. An opportunity for admission based on a

fair range of prediction criteria is all they seek, and con

sidering their past exclusion from the legal profession, the

respondents’ moderate program is, at least, constitutionally

appropriate.

The Washington Supreme Court found the factors justi

fying respondents’ minority admissions program constituted a

compelling state interest. This characterization should not be

disturbed even if the Court finds that the program is not

required by federal law. Associated General Contractors o f

Massachusetts, Inc. v. Altshuler, __ F. 2d __ ,4 2 U.S.L.W.

2320 (Dec. 25, 1973).

IV. The historic exclusion of racial minorities from the legal

profession justified respondents’ affirmative efforts to attract

qualified minority applicants.

18

The Constitutional appropriateness of the respondent law

school’s minority admission policies need not be assumed.

The dearth of black lawyers which respondent officials hope

their admissions policies will help to alleviate, did not occur

by chance. It is directly related to a pattern of systematic

exclusion of blacks from the legal profession that dates back

to Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857).

The finding in that decision that no blacks were citizens,

whether slave or not, served as a barrier to blacks being

admitted to practice, since virtually all the states required

citizenship as a qualifying condition for admission to their

bars.2 By the Civil War in 1860, there were 4,441,830 blacks

in the country, only 488,070 (11 percent) of whom were

free,3 but probably no more than eight black lawyers.4

The end of the Reconstruction period also marked the

decline of the few black lawyers who had made some

2 Brown, The Genesis o f the Negro Lawyer in New England, 22 THE

NEGRO HIST. BULL. 147, 148 (1958). Brown advises that Macon B.

Allen, the nation’s first black attorney, was denied admission on motion

under Maine law which rendered any citizen eligible for admission who

produced a certificate of good moral character. Allen was rejected on

the ground that he was not a citizen. He was subsequently admitted in

1844 after satisfactory examination by a committee of the Bar.

3 P. BERGMAN, THE CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY OF THE

NEGRO IN AMERICA, 221 (1969).

4 See Leonard, The Development o f the Black Bar, 407 THE

ANNALS, .134, 136 (May, 1973), and Brown, supra, note 2, Part I,

147-51, and Part II, at 171-77. Five black lawyers, Macon Allen, Robert

Morris, Aaron Bradley, Edwin Walker, and John S. Rock, practiced in

Massachusetts before the Civil War. John Mercer Langston became a

member of the Ohio Bar in the 1850s, Garrison Draper joined the

Maryland Bar in 1857, and Jonathan J. Wright was admitted to the

Pennsylvania bar about this time.

19

advances in practice and politics.5 As late as 1940, when the

black population had grown to 12,866,000,6 there were only

about 1,063 black judges and lawyers, one professional for

every 12,103 blacks.7 Those blacks admitted to practice were

excluded from the American Bar Association until 1943,

when Judge James S. Watson of New York was elected.8

Racial prejudice, combined with a continuing lack of educa

tional and economic resources, served to curtail seriously the

number of blacks who aspired to join the legal profession and

limited the range of success and accomplishment for those

5 See Leonard, supra, note 4, at 137.

6 BERGMAN, supra, note 3, at 486.

7 M. DAVIE, NEGROES IN AMERICAN SOCIETY, 116 (1949).

The great majority of these lawyers were trained in black law schools.

Howard University opened a law department in 1868. Eleven additional

schools began in the decades that followed, but only one survived until

1921. Stevens, Two Cheers For 1870: The American Law School, in

LAW IN AMERICAN HISTORY, 405, 428, n. 16 (D. Fleming and B.

Bailyn eds. 1971).

Following this Court’s decisions requiring desegregation of state law

schools, infra, note 11, several black law schools were initiated. Today,

in addition to Howard, the predominantly black schools are North

Carolina Central Law School, in Durham, North Carolina, Southern

Unviersity Law School in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Texas Southern

University Law School in Houston, Texas.

8 DAVIE, supra, at 118. Three blacks, whose racial identity was not

known, were admitted into the ABA in 1912. The long exclusion of

blacks by the ABA led black lawyers to form the National Bar

Association in 1925. See also, Leonard, supra, note at 140-43.

20

who somehow overcame these multiple handicaps to law

practice.9

Until recently, white law firms, government, business as

well as bar associations were closed to black lawyers who,

with some notable exceptions, operated on the fringe of the

profession.10 Except for the few predominantly black

9 The court below cited a representative collection of published data

and studies as evidence of the barriers facing blacks who aspired to a

legal career. 507 P. 2d at 1182, n. 12. But it is simply not possible to

gauge how many black youth have been exposed to experiences similar

to the conversation with his high school teacher reported by Malcolm

X. It was in the early 1940s in East Lansing, Michigan, and his English

teacher, Mr. Ostrowski, who had given him good grades and taken an

interest in him, asked him whether he was thinking about a career.

Malcolm replied:

‘Well, yes sir, I’ve been thinking I’d like to be a lawyer.’

Lansing certainly had no Negro lawyers — or doctors either — in

those days, to hold up an image I might have aspired to. All I

really knew for certain was that a lawyer didn’t wash dishes, as I

was doing.

Mr. Ostrowski looked surprised, I remember, he leaned back in

his chair and clasped his hands behind his head. He kind of

half-smiled and said, ‘Malcolm, one of life’s first needs is for you

to be realistic. Don’t misunderstand me, now. We all here like

you, you know that. But you’ve got to be realistic about being a

nigger. A lawyer — that’s no realistic goal for a nigger. You need

to think about something you can be. You’re good with your

hands - making things. Everybody admires your carpentry shop

work. Why don’t you plan on carpentry? People like you as a

person — you’d get all kinds of work.’ A. HALEY, THE AUTO

BIOGRAPHY OF MALCOLM X, 36-37 (1964).

10 Gellhorn, The Law Schools and the Negro, 1968 DUKE L. J.

1070, n. 13. See also, M. DAVIE, NEGROES IN AMERICAN

SOCIETY, 115-116 (1949); Shuman, A Black Lawyer’s Study, 16

HOWARD L. J. 304 (1971); McGee, Black Lawyers and the Struggle

for Racial Justice in the American Social Order, 20 BUFFALO L. REV.

21

schools, Southern law schools were completely closed to

blacks until required to admit them by a series of court

orders handed down over a 20-year period from the 1930s

through the 1950s.11 But even after the 1954 school desegre

gation decision, many Southern schools continued to refuse

black applicants until the late 1960s.12

In the North, law schools were not formally closed to

blacks, but few were admitted until the initiation of minority

recruitment and admissions programs in the late 1960s. Due

m part to these programs, there were 7,601 minority students

in ABA approved law schools during the 1973-74 school

year.13 The 4,817 black students exceeds the estimated

423 (1971); Note, Negro Members o f the Alabama Bar, 21 ALA. L.

REV. 309 (1969); Carl and Callahan, Negroes and the Law, 17 J.

LEGAL ED., 250 (1965).

The difficulties black lawyers have faced are pointed up by the

observation of Judge Robert L. Carter, formerly NAACP General

Counsel, who observed that the notable civil rights achievements of

Charles Houston, Thurgood Marshall, William Hastie, Spottswood Rob

inson and Constance Baker Motley, and other black lawyers tends to

obscure the fact that few blacks have enjoyed noteworthy success in

any field of law, including that of civil rights. Bell, Black Students in

White Law Schools: The Ordeal and the Opportunity, 1970 TOLEDO

L. REV. 539, 541.

11 Compare the evasive tactics employed in University of Maryland

v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 590 (1936), with those used 20 years

later in Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control, 350 U.S. 413

(1956). In the interval, this Court had spoken clearly on the subject of

segregated law schools in Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950), Sipeul

v. Bd. of Regents of Univ. of Oklahoma, 332 U.S. 631 (1948), and

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938). The higher

education litigation is discussed generally in J. GREENBERG, RACE

RELATIONS AND AMERICAN LAW, 260-69 (1959).

12 Gellhorn, supra, note 9, at 1070.

13 1973 Survey of Minority Group Students in Legal Education,

Association of American Law Schools (Dec. 1973).

22

4.000 black practitioners by a sizeable number,14 and

probably the 2,784 other minority students far exceeds the

number of lawyers who belong to these groups.15

But expressions of satisfaction over this undoubted prog

ress are muted by a review of comparable white statistics.

The 7,601 minority-group students represent only seven per

cent of the 106,102 students in law schools during the

1973-74 school year. The estimated 4,000 black lawyers

represent little more than one percent of the nation’s

300.000 lawyers.

There is a white attorney for every 631 whites in the

country. While according to the U.S. Census, there were more

than 22 million blacks in 1970, this averages out to only one

black attorney for every 5,500 blacks. The figure would

probably be far worse if other minorities were considered,

and if the number of minority law graduates not working in

law-related jobs were excluded.

Available data on minority attorneys in the State of

Washington reflect the national pattern. In 1970, there were

4,550 active lawyers in the State. There was a white lawyer

for every 720 whites in the State, but only 20 black lawyers

14 See Edwards, The New Role for the Black Law Graduate: A

Reality or an Illusion? 69 MICH. L. REV. 1407, 1432 (1971). Professor

Edwards’ study of hiring patterns in large mid-western law firms

revealed that racial restrictions remain quite visible.

Employment concerns are not the only special problems confronting

minority students. See, Parker and Stebman, Legal Education for

Blacks, 407 THE ANNALS, 144 (May 1973).

15 Morris, Equal Protection, Affirmative Action and Racial

Preferences in Law Admissions: DeFunis v. Odegaard, 49 WASH. L,

REV. 1, 4-5, notes 14-15 (1973).

23

in all (three of these were judges), five Indian lawyers, and

not one Mexican-American lawyer, despite the 70,734 Mexi

can-Americans in Washington.16

The minority groups considered in the respondent law

school’s minority admissions program (blacks, Indians, Mexi-

can-Americans, and Filipinos) total about 186,890 or 6.2

percent of the population. Excluding the black judges, there

are only 22 minority lawyers in the State, or one minority

lawyer for every 8,495 minority persons.

The use of statistical disparities to illustrate the exclusion

of minorities from the legal profession is not intended to

suggest that all minority people want or should be required

to use lawyers of their particular group. They certainly

should not be interpreted to diminish the valuable service

rendered to the cause of racial equality by white attorneys.

What black people are entitled to in selecting lawyers is a

choice not arbitrarily limited because of state-sanctioned

racial exclusion.

The Washington Supreme Court concluded from the avail

able data that minorities are “grossly underrepresented in the

law schools - and consequently in the legal profession - of

this state and this nation.” DeFunis v. Odegaard, 82 Wn. 2d

11, 32-33, 507 P. 2d 1169, 1182 (1973).

Based on the disparities reflected in these statistics, one

commentator has gone further, suggesting that “While the

state voluntarily undertook to provide a corrective program

of law school admission it may actually have been under a

constitutional duty to have done so.” 17 Certainly a state law

16 Id. at 37-38.

1 7 Id. at 39.

24

school, faced with the significance of statistics such as those

in this case, is not bound to wait for a court to mandate

action based on the Constitution before adopting policies that

will both comply with its words and honor its spirit.

Indeed, it is the adoption of precisely such policies that

keeps alive the dream that this society may someday outgrow

the need to protect its minority members against discrimina

tion based on race, color, or creed.

For all the foregoing reasons, amicus curiae urge this Court

to affirm the judgment of the Supreme Court of Washington.

Respectfully submitted,

DERRICK A. BELL, JR.

Harvard Law School

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

Attorney for Amicus Curiae

Of Counsel:

LENNOX S. HINDS

National Director,

National Conference

of Black Lawyers

126 West 119th Street

New York, N.Y. 10027

HAYWOOD BURNS

University of New York at Buffalo

School of Law

Buffalo, N.Y. 14202