Absentee Voting Problems and Proposals; Correspondence from Hermann to Baggett; Correspondence from Kennedy to Turner

Correspondence

January 17, 1977

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Absentee Voting Problems and Proposals; Correspondence from Hermann to Baggett; Correspondence from Kennedy to Turner, 1977. 8cad12c2-ed92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9f6d2164-6151-4c82-8bc3-8a5f8d8debf6/absentee-voting-problems-and-proposals-correspondence-from-hermann-to-baggett-correspondence-from-kennedy-to-turner. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

ABSENTEE VOTING PROBLEMS ANffi

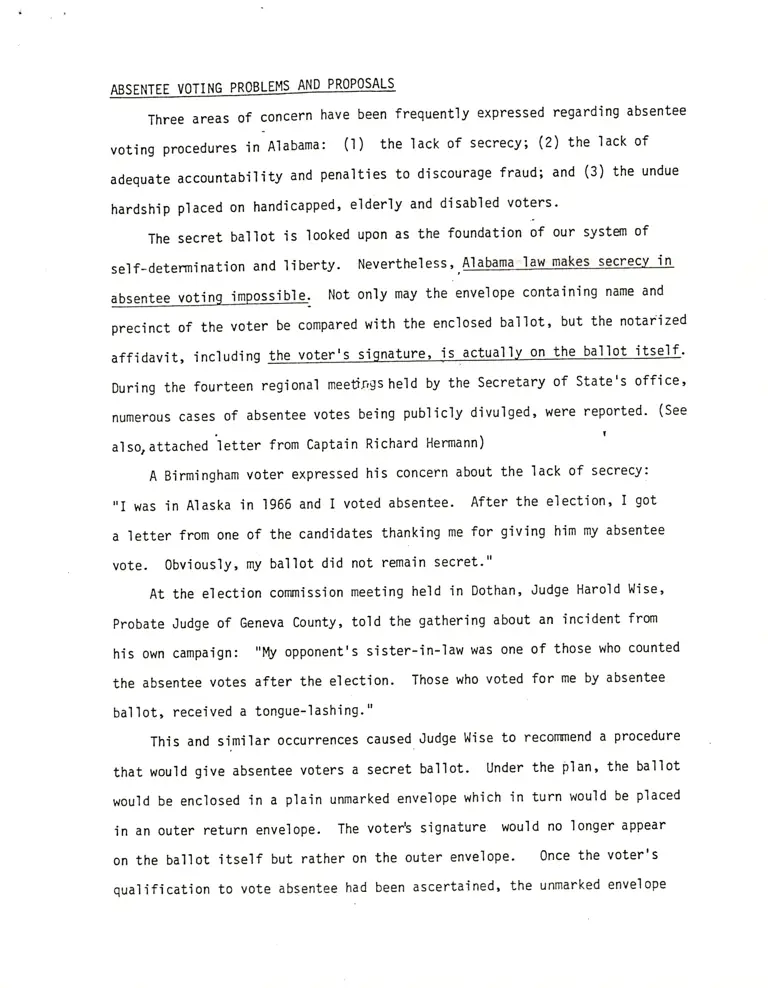

Three areas of concern have been frequent'ly expressed regarding absentee

voting procedures in A'labama: (l) tfre Iack of secrecy; (2) the lack of

adequate accountability and penalties to discourage fraud; and (3) tne undue

hardship placed on handicapped, elderly and disabled voters'

The secret ballot is looked upon as the foundation of or. system of

se'lf-determination and liberty. Nevertheless,,Alabama law makes secrecy in

absentee voting impossible, Not only may the enveiope containing name and

During the fourteen regional meeoS,gsheld by the Secretary of State's office'

numerous cases of absentee votes being publicly divulged' were reported. (See

alsorattached letter from Captain Richard Hermann) t

A Birmingham voter expressed his concern about the lack of secrecy:

,,I was in Alaska in 1966 and I voted absentee. After the e'lection, I got

a 'letter from one of the candidates thanking me for giving him my absentee

vote. 0bvious'ly, my bal lot did not remain secret' "

At the election commission meeting held in Dothan, Judge Haro'ld Wise,

Probate Judge of Geneva county, told the gathering about an incident from

his own campaign: "My opponent's sister-in-law was one of those who counted

the absentee votes after the election. Those who voted for me by absentee

ballot, received a tongue-1ashing. "

This and si.milar occurrences caused.Judge l.Iise to reconcnend a procedure

that would give absentee voters a secret bal'lot. Under the plan, the ballot

wou'ld be enclosed in a plain unmarked envelope which in turn would be placed

in an outer return envelope. The voter's signature would no 'longer appear

on the bal'lot itself but rather on the outer envelope. 0nce the voter's

quaiification to vote absentee had been ascertained, the unmarked enveiope

precinct of the voter be compared with the enc'losed ballot, but the notarized

affidavit, including the voter's siqnature, !s actually on the ballot itself.

-?-

wourd be removed and praced in a bailrot.box arong with the other absentee votes'

Thus,itwouldbeimpossibletoidentifyaspecificvoterwithaparticularballot'

A survey of absentee voting laws in other states found none' except A'labama'

that requires the voter,s signature on the bailot itserf. The system which

Judge l.lise reconmends, on the other hand, is similar to procedures already in

useinArkansas,Georgia,Florida'Kentucy'Louisiana'Texas'andllestVirg'in'ia'

Another absentee ba1 1ot'ing problem which concerned participants at the

regional meetings was the lack of accountabi'litv ana tne potentia

and fraud. It was Pointed out

enough to be determi ned bY the

the absentee sYstem is crucial

that the results of many elections are close

absentee box; consequent'ly, the security of

to maintaining the integrity of the entire

elections Process. r

EarlPhillipsstatedhisbeliefthatabsenteeba]lotinghadbeenabused:

,,In Lowndes and }Iilcox counties, there were more absentee voters than in

Jefferson County. Something is wrong." R' P' Thompson concurred: "For our

voting popu'lat'ion in Wilcox County, 1700 absentee baltots is too many"'

Accord'ing to a Dothan participant, "candidates go out to rest homes

and 'vote' many of those people because they just don't know what's going

on around them." Dot Carmichael of Tuscumbia agreed: "During the last

election I took absentee ballots to the nursing hom' If it's not handled

in the right way, nBny of these people could easily be inf]uenced.l'

These, and many other reports of dead people "voting" and inactive

voters being lvbted", emphasize the need for better contro'l and accountability

in absentee voting.

Legislation establishing an accountability system has been drafted'

and increased penalties for fraud have been proposed, with such penalties

tobeprintedontheabsenteeballot,apPlicationandoath.

-3-

A third area of concern regarding absentee voting is the requirement of

a doctor,s certificate for iilr or disab'red voters who wish to vote absentee.

,,Sick people and those in rest homes have to go to more trouble than we'll

people," commented Bill Moody at the Montgomery meeting' lrl' A' Kynard'

Dallas County Circuit Court Clerk' had this to say about the doctor's

certi ficate requirement:

This does not make sense if that person 'is confined- how

will iie-get-the application to a doctbr? You are talking.

iUort i irip for ib*.on. to the Absentee Election Manager's

oiiii. to picf up-ine ippiication, a trip to the Doctor's

office for hit tigniir.E'(*[iin ii sometimes hard'to get) and

;il; trlp back Io tt. Absentee E'lection Manager's office

,ltii if,. aip'lication in order to get a ballot. After the

uiiioi ir bbfir...a'to'tne-ionfin6d pers.on, a notarv public

his to be there to notarize the confined peron': tignature on

ff. uirrot. auiie iimpiv, it is much mgre coqpl iqal,ed-fgr

iomeone to vo

sical conditiion e than s for someo1e

u appen to be oq! town on election

. Mr. Aaron Kennedy of cOker, Alabama, experienced the frustration caused

by our cumbersome absentee process. His account is out'lined in a letter written

to Tuscaloosa Circuit Clerk, Doris Turner' (See letter attached)'

The consensus of those who attended the regional meetihgs was that we

should end this double standard which requires substantially more effort from

the ill and disabled than a healthy businessman, student' or other person who

happens t0 be out of their county on election day'

The proposed legislation removes this extra burden and permits disabled

voters to sign an affidavit stating their inability to go to the polling place'

This requirement is analagous to the oath taken by a1l other absentee voters

affirming their'absence from the county 'on e'lection day'

Although the three absentee voting prob'lems discussed above received the

most frequent mention at the e'lection law conrnission regional meetings' many

other questions were raised and suggestions were offered.

-4-

Three of these conments are listed below followed by a sunmary of relevant

absentee procedures in other states.

1. "Why don't we let al'l elderly people vote absentee?"

Our research indicates that five stated have special absentee provisions

for the elderl.v. Michigan allows those 62 years of age or older to vote

absentee whi'le Tennessee and Arizona set 65 as the age of eligibility.

Absentee bal'lots may be cast by those "who are suffering from old age" in the

state of Rhode.Island, and by those "disabled by old age" who live in Kentucky.

?. Why'can't people who live or work several miles from their polling place

vote absentee?"

Six states make absentee voting availaL]e to those who do not

a polling place. Colorado and California allow those who live l0 miles or more

from their polTing p'lace to vote absentee. Arizona and Oregon seL the distance

at 15 miles. The Maine election code allows absentee voting by those who live

an "unreasonable" distance from the pol'ls, and in Alaska those who live in

"remote and inaccessib'le areas" may cast an abSentee ballOt.

E'leven states permit absentee votinq bv workers and other P€rsons who are

absent from their precinct or votinq district on election dav. By way of

contrast, Alabama requires absence from the county; In Arizona' California'

Georgia, Iowa, Hawaii, Nevada.and South Dakota, those who "expect" to be absent

from their precinct may apply for an absentee ballot. Arkansas and A'laska allow

absentee voting by persons "Unavoidably" absent from their precinct, whi'le in

Colorado one's absence from the precinct must be "due to emploirment-" The

Minnesota code i's the least restrictive ind simp'ly provides that "any person

entitled to vote who is absent from his precinct....is eligible to vote by

absentee ba] I ot. "

3. ,'Any person who is leaving town on short notice iust before an election

should be able to vote an absentee ballot-"

-5-

Cur.ent A]abama law requires that requests for absentee bal'lots must be

made at least five da.vs before an election. t,Jhile this may be an administrative

convenience, it fails to recognize that last minute emergencies, such as accidents'

giving birth, business demands, etc., occui^ with considerable frequency. Our

review of state election codes found'17 states that provide for last-minute

emergency absentee bal'lot requests. Texas, Kansas, Iowa, Nebraska, Idaho'

Minnesota, 6regon, Nevada, l''laryland, Michigan, California and Alaska wi'l'l accept

last-minute absentee app'lications, even on election day, in certain circumstances.

In addition, the following'16 states accept app'lications for absentee ballots on

the day before the election: Georgia, Fiorida, Arkansas, North Caro'lina,

Colorado, Arizona, Utah, Washington, Wyoming, [.Iisconsin, Missouri, Montana'

North Dakota, New Jersey, Massachusetts and Vermont.

The most pressing absentee ballot issues are addressed by thg ProPosed

'legislation; but here are other problems, less immediate but stil'l important,

that need attention in the near future. Our restrictive ru]es regarding the

absentee voting process have evolved in an attempt to guard against fradulent

activity. The resu'tt has been to place undue hardship on wouid-be absentee

voters, y€t the possibi'lity of election fraud still remains. 0nce the new

measures for control and accountability in the absentee process are implemented,

a careful examination of the restrictive and disenfranchising provisions of our

elections code would certainly be in order.

OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE

WASHTNGTON, D. C. 20301

Honorable Agnes Baggett

Secretary of State of Alabama

Capitol Building, Roon 105

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

Dear Madam Secretary:

our office received a call last week frou Ist Lt. B. Alan Zj-egfer,

usAtr, who votes by absentee ballot in Talladega county. Lt. ZlegLet

expressed great "trr".rt about the secrecy of his ballot. IIis'

concern was Prrovoked by the requireloent of Title 17, Code of

Alabama, that'absentee voters sign an affidavit prlnted on the

ballot. Lt. Ziegler al-so informed us that his Parents, who voted

absentee in tgoveib er, L976, erere infomed for whom they voted by

other Talladegans. r

I have disiussed this matter with l"ls. Edna Brooks of your office'

Ms. Brooks was Dost gracious and heJ-pful' Please convey tuy

appreciation of thaE to her. We are' as you know, always

avail-able to assi3t your office and the Alabana Legislature

to resolve this Problem.

Ms. Brooks also info:med me that the Legislature is conteuplating

the establishoent of an electoral ssrrmissien. If thls should

come to pass, the Federal voting Assistance Division would be

very willing to work with and advise the s6mm'i55lsn'

I would appreciate being kept informed of developoents wich

respect tt-lt. ZLegLerts concerfl for the secret ballot.

Best wishes for the new Year.

1 7 JAN 877

REC ETyEDJ

JAN 23 lgi?

IS.ECfiETARY ON

\ssAq_-./ i

Sincerely,

<J&

RTCIIARD L. HERMANN

caprain, usA, JAGC

Legal Advlsor, Federal

Voting Assistance Dlvision

{ tii lFr,xl;7

it Ke{? frr3{+i)-

'1r, 33q- e i i I