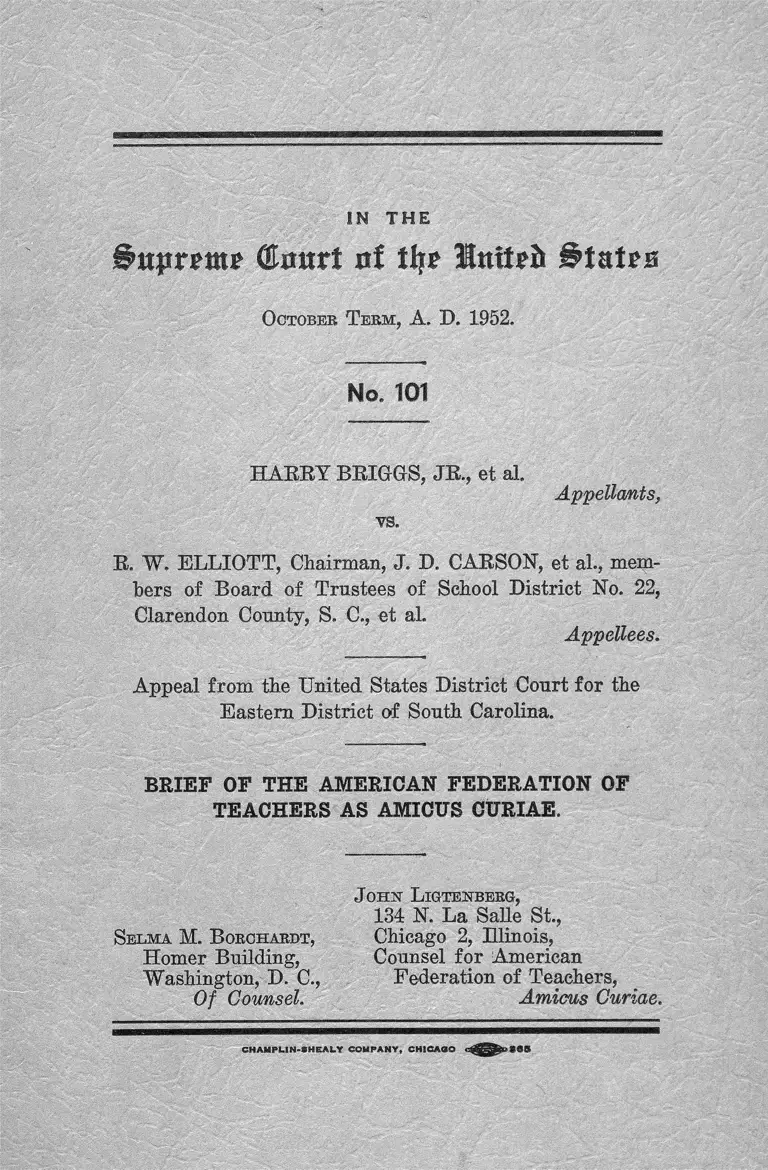

Briggs v. Elliot Brief of the American Federation of Teachers as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Briggs v. Elliot Brief of the American Federation of Teachers as Amicus Curiae, 1952. 20585387-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9fb5bc7f-cb20-4a87-8895-5f5f4f1798c0/briggs-v-elliot-brief-of-the-american-federation-of-teachers-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

JN T H E

(& x m x t n i X\\t States

O ctober, T e r m , A. D. 1952.

No. 101

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., et al.

vs.

Appellants,

R. W. ELLIOTT, Chairman, J. D. CARSON, et al., mem

bers of Board of Trustees of School District No. 22,

Clarendon County, S. C., et al.

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of South Carolina.

BRIEF OF THE AM ERICAN FEDERATION OF

TEACHERS A S AM ICUS CURIAE.

J o h n L igtenberg ,

134 N. La Salle St.,

S e lm a M. B orchardt, Chicago 2, Illinois,

Homer Building, Counsel for American

Washington, D. C., Federation of Teachers,

Of Counsel. Amicus Curiae,

CHAM PL.IN-SHEALY COM PANY, CHICAGO •SOB

I N D E X .

PAGE

Brief of the American Federation of Teachers as

amicus curiae............................ 1

Question Presented ....... 2

Opinions B elow .................................... 2

Statutes and Constitution Involved........................ 2

Statement ........... .............................................................. 2

Summary of Argument............... .......... ............... . . . . 3

Argument:

I. The equalization of the segregated school sys

tems of the nation is impractical. Since it

cannot be done effectively, equal protection

can be achieved only by abolishing segregation 4

II. The Constitution and Statutes of South Caro

lina providing for segregation of students in

the public schools, violate the requirements of

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The doctrine of “ separate but

equal” facilities is falacious ........................... 6

III. Segregation in public schools inevitably re

sults in inferior educational opportunities for

N egroes............................... ............................. 9

IY. Segregation in public schools deprives the

Negro student of an important element of the

education process and he is thereby denied the

equal educational opportunities mandated by

the Fourteenth Amendment ............................. 11

T able op Cases.

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, registrar, 305 U. S.

337 ................. 7

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637... 8,9

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633 .......................... 7

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 .................. 7

11

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1 .................................... 7

Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa, 332 U. S. 631....................................................... 7

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ............................ ; . . . 8

Takahashi v. Fish & Game Commission, 332 U. S. 410.. 7

C o n stitu tio n and S tatu tes .

See Appellants’ Briefs.

M iscellan eou s .

Forty Eight School Systems, 1949, Council of State

Governments, Francis S. Chase and Edgar L.

Morphet, pp. 192,194 .................................................. 5

Hamilton & Mort, The Law and Public Education,

Ch, 1 , .............................................................................. 4

Inventory of Public School Expenditures, John K.

Norton and Eugene S. Lawler, 1944 Yol. 2, p. 293 ft.. 5

Lewin, Kurt, “ Resolving Social Conflicts,” pp. 174 and

214, Harper & Bros., 1948 ............................................ 12

National Survey of the Higher Education of Negroes,

Vol. 1 .............................................................................. 10

Negro Year Book, Tuskegee Institute, 1947. “ The

Negro and Education,” p. 56. W. Harden Hughes.. 9

Public School Expenditures, Dr. John Norton and Dr.

Eugene S. Lawler, American Council on Education,

1944 ................................................................................ 10

Socio-Economic Approach to Educational Problems,

Misc. No. 6, Vol. 1, p. 1, Federal Security Agency,

U. S. Office of Education, Wash., 1942 .................... 10

Statistics of State School Systems, 1947-1948, Federal

Security Agency, Gov’t, Printing Office....................... 5

The Black & White of Rejections for Military Service,

American Teachers Assn. Studies, ATA Mont

gomery, Ala., 1944 ................. 10

The Legal Status of the Negro (p. 134), Charles S.

Mangum, Jr., Chapel Hill University of N. C. Press,

IN THE

Bnpvvnw Glmirt ni \\\z BtnU&

October T erm , A. D. 1952.

No. 101

HAERY BRIGGS, JR., et al.

vs.

Appellants,

R. W. ELLIOTT, Chairman, J. D. CARSON, et al., mem

bers of Board of Trustees of School District No. 22,

Clarendon County, S. C., et al.

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of South Carolina.

BRIEF OF THE AM ERICAN FEDERATION OF

TEACHERS AS AMICUS CURIAE.

The American Federation of Teachers submits this brief

as amicus curiae in view of the great importance to de

mocracy and the cause of education of the constitutional

issue involved in this case.

2

Opinions Below,

Constitution and Statute Involved,

The opinions below and the constitution and statute in

volved are set out in the brief of the appellants.

Question Presented.

I .

Whether the legally enforced racial segregation in the

public schools of South Carolina denies the Negro children

of the state the equality of educational opportunity re

quired under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

I I .

Whether the “ separate but equal” schools decreed by

the District Court can be enforced in a segregated society.

Statement.

In appellants brief, pp. 2-9, is a full statement of the

case.

The constitution and statutes of South Carolina require

the segregation of the races in the public schools. These

legal requirements are enforced in the defendant school

district by maintaining separate schools for white children

and colored children. The Appellees defend these sep

arate schools as a valid exercise o f the state’s legislative

power.

3

The statutory three judge court held, with one judge

dissenting, that neither the constitutional nor statutory

provisions requiring segregation in the public schools

were in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. The

court also found that the educational facilities offered ap

pellants were not equal to those offered white children, and

ordered that equalization of educational opportunity be

put into effect.

It appears that South Carolina is 'taking steps to equalize

educational opportunities for Negro children. At a sec

ond hearing the court found “ equalization” had not been

achieved, but still refused to enjoin the practice of segre

gated schools.

Hence, the issue remains, whether equalization is per se

a denial of equal protection of the laws.

Summary of Argument.

In this brief amicus curiae the American Federation of

Teachers will argue that in a segregated school system,

equality of educational opportunity is impossible of

achievement; - that the attempt to enforce a system of

“ separate but equal” facilities would meet with endless

difficulties and would defeat its own ends; that in any

event segregation in the schools violates basic educational

principles; and that Negroes forced by state law to attend

segregated schools are denied the equal protection of the

laws.

4

A R G U M E N T .

I .

The equalization of the segregated school systems of the

nation is impractical. Since it cannot be done effectively,

equal protection can be achieved only by abolishing seg

regation.

In the United States, education is usually conceived as a

state function, and as such the concern of all the people.

In all the states there is a measure of central control and

the states carry out some of the operations of broad scope

such as institutions of higher learning and teacher train

ing. Aside from such specific functions, usually a wide

range of responsibility is assigned to local agencies.1

In practice the local educational program is carried out

through school districts, generally having a small terri

torial extent, but with wide discretionary powers.

With regard to territorial extent, the typical school dis

trict covers a city and sometimes some adjacent territory.

In rural areas, the usual school district covers a congres

sional township or a comparable area. In a few states,

districts are county wide. As a result there are hundreds

and even thousands of districts in each state.

This describes the national scene and conditions in the

seventeen states having laws requiring segregated schools.

The pattern holds good for South Carolina. In 1947-48

there were 3399 elementary schools and 486 high schools.

1 Hamilton and Mart, The Law and Public Education, 1941, Ch. 1.

5

These 3885 schools were operated by 1680 separate schoul

districts.2

In proportion to population and geographic size the same

holds true for the seventeen states which maintain sepa

rate schools. The same authorities give the number of

school districts in 1947-1948 in these states as follows:

Alabama ....................

N um ber of School D istricts

........................... 108

Arkansas ............... .......................... 1589

Delaware . . . . . . . . . ........................... 126

Florida ................... ........................... 67

G eorgia................... .......................... 189

Kentucky ............... .......................... 246

Louisiana ............... ............. ............. 67

Maryland ................ ........................... 24

Mississippi............... ........... ...............4211

Missouri .................... .......................... 8422

Oklahoma . . ............. .......................... 2669

North Carolina . . . . .......................... 172

South Carolina . . . . . .................... .. .1680

Tennessee . . . . . . . . . .......................... 150

Texas .......................... .......................... 4832

Virginia .................... .......................... 125

West V irgin ia ......... .......................... 55

The total school population of these states is approxi

mately 30% of the nation’s total.3

There are many variable and imponderable factors that

go into the evaluation of a school system. Comparisons

inevitably lead to contrasts. Every school district pre

sumably has the best schools it can afford. In a segre

gated system the dominant group naturally does not slight

2 Forty Eight School Systems, 1949 Council of State Governments,

Francis S. Chase and Edgar L. Morphet, pp. 192, 194. See also Statis

tics of State School Systems, 1947-1948, Federal Security Agency; Govt.

Printing Office.

3 Inventory of Public School Expenditures in the U. S. John K.

Norton and Eugene S. Lawler, 1944, Vol. 2, p. 293 ff.

6

its own children, particularly when funds are not avail

able to provide the best for all.

In resolving the Constitutional issue of segregated

schools the court must take into account not only the case

before it but the wider impact of its decision.

For example it might be possible for the Court to en

force equality in District No. 22, Clarendon County, S. C.

But when this policing is multiplied by the 1680 districts

in the state, and multiplied again by the districts in the

sixteen other states the task appears monumental and in

deed impossible. Only by striking down the system of

segregation itself can equality be achieved and discrimi

nation swept away.

The court has said that the rights guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment are “ personal and present” . The

children of the present will have but little personal satis

faction in awaiting the results of equalization litigation

in the thousands of school districts involved. Fortunately

the remedy, though painful to some, is simple.

I I .

The Constitution and Statute of South Carolina providing

for segregation of students in the public schools, violate

the requirements of the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. The doctrine of “ separate but

equal” facilities is fallacious.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, in

Section 1, provides:

“ All persons born or naturalized in the United

States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are

citizens of the United States and of the State wherein

they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law

7

which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of

citizens of the United States; nor shall any State.de

prive any person of life, liberty, or property, without

due process of law; nor deny to any person within its

jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The Fourteenth Amendment made Negroes citizens of

the United States and was intended further to protect

them fully in the exercise of their rights and privileges. To

make sure that this intent wTas fully known, Congress re

fused to readmit Southern States or seat their represen

tatives until the states accepted the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

Its adoption, however, did not stop the practice of segre

gation in the Southern States and the idea of separate but

equal facilities came into being.

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, 550, (1896)

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, registrar, 305

U. S. 337, 349.

Recent decisions of this Court enunciate principles in

conflict with the rationale of the Plessy and Gaines cases.

These include: Takahashi v. Fish & Game Commission,

332 U. S. 410; Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633, 640, 646

(1948); Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of

Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631 (1948); Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U. S. 1 (1948).

In the Shelley case, this court, in considering private

agreements to exclude persons of designated race or color

from the use or occupancy of real estate for residential

purposes and holding that it was violative of the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment for state

courts to enforce them said (at p. 23):

“ The historical context in which the Fourteenth

Amendment became a part of the Constitution should

8

not be forgotten. Whatever else the framers sought to

achieve, it is clear that the matter of primary concern

was the establishment of equality in the enjoyment of

basic civil and political rights and the preservation

of those rights from discriminatory action on the part

of the States based on considerations of race or color. ’ ’

These principles cast doubt on the soundness of the rule

laid down in the Plessy and Gaines cases. We submit that

it should no longer be followed.

Nowhere has the fallacy of the doctrine of “ separate

but equal” facilities been more apparent than in the grade

and high schools of the country. Elsewhere, in this brief

we shall point out the sociological effects of this practice.

In SweaM v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, 70 S. Ct. Rep. 848 the

court held that a separate law school established by Texas

for Negro students could not be the equal of the Univer

sity of Texas Law School.

In McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637,

70 S. Ct. Rep. 851 the court held that the requirements of

state law that the instruction of a Negro graduate student

in the University of Oklahoma “ upon a segregated basis”

deprived the appellant in that case of his personal and

present right to the equal protection of the laws.

There is no reason in experience for applying a different

logic to children in grade and high schools. As the court

there said, Our society grows increasingly complex and

our need for trained leaders increases correspondingly.

We cannot give separate training to two segments of

society and then expect that some magic will merge the in

dividual from these segments into equal citizens having

equal opportunities.

It is a mockery to say that those who aspire to teach and

lead must have equal opportunity regardless of race, and

still condemn those they are to teach and lead to inequality.

9

Ninety years of segregated schools demand the historical

judgment that separate facilities are inevitably unequal

and are not the way to equal opportunity.

In the segregated school system the growing citizen

never has the chance to show his equal ability; he never

has the

“ opportunity to secure acceptance by his fellow stu

dents on his own merits.” McLaurin v. Oklahoma State

Regents, 339 U. S. 637, 641.

He must wait until he has finished what schooling he gets

before he enters the competition. For him “ the personal

and present right to the equal protection of the laws” is

of as great practical importance as for the graduate stu

dent.

The Fourteenth Amendment is not for law students and

post-graduates alone. It is meaningless if it does not ap

ply to all.

I I I .

Segregation in public schools inevitably results in inferior

educational opportunities for the Negro.

Commenting on the study of Dr. John Norton and Dr.

Eugene Lawler—Public School Expenditures (1944) W.

Harden Hughes states:

The contrasts in support of white and Negro schools

are appalling . . . the median expenditure per standard

classroom unit in schools for white children is $1,160

as compared with $476 for Negro children. Only

2.56% of class rooms in the white schools fall below

the $500 cost level while 52.59% of the class rooms

for Negro children are below this level.” 1

1 Negro Year Book, Tuskegee Institute 1947. "The Negro and Educa

tion.” W. Harden Hughes, p. 56.

“ The state supported institutions of higher learning

for Negroes are far inferior” states Charles S. Man-

gum, Jr., “ to their sister institutions for whites. Most

of the inequalities which have been noted herein with

respect to the public schools for whites and Negroes

are also present in the Negro normal and technical

schools. . . . There is hardly one among them that

could compare with any good white college in the same

area.” 2

Several recent studies,3 4 as well as many previous

ones, all indicate the great disparity between the educa

tional opportunities afforded white youth and those of

fered to the Negro youth in the states where a segregated

and discriminatory system of education prevails.

So obvious are the inequalities that in Vol. 1 of the Na

tional Survey of the Higher Education of Negroes we find

this statement: “ No one with a knowledge of the facts

believes that Negroes enjoy all the privileges which Ameri

can democracy expressly provides for the citizens of the

U. S. and even for those aliens of the white race who reside

among us. The question goes much deeper than the Negro

citizens’ legal right to equal educational opportunity. The

question is whether American democracy and what we like

to call the American way of life, can stand the strain of

perpetuating an undemocratic situation; and whether the

nation can bear the social cost of utilizing only a fraction

of the potential contribution of so large a portion of the

American population.*

2 The Legal Status of the Negro (p. 134), Charles S. Mangum, Jr.,

Chapel Hill University of N, C. Press, 1940.

See Public School Expenditures, Dr. John Norton and Dr. Eugene S.

Lawler, American Council on Education, 1944.

3 The Black & White of Rejections for Military Service, American

Teachers Assn., Studies, ATA Montgomery, Ala., 1944; Public School

Expenditures in the U. S., Dr. John K. Norton and Dr. Eugene S.

Lawler; American Council on Education, Wash., D. C., 1944; Journal of

Negro Education, Summer 1947.

4 Socio-Economic Approach to Educational Problems, Misc. No. 6,

Vol. 1, p. 1, Federal Security Agency, U. S. Office of Education, Wash.,

1942.

The Constitution is a living instrument, and a “ separate

but equal” doctrine based upon antiquated considerations,

should not, at this time, and in this advanced era, he per

mitted to perpetuate a situation which denies full equality

to Negroes in the pursuit of education.

I V .

Segregation in public schools deprives the Negro student

of an important element of the education process and he

is thereby denied the equal educational opportunities

mandated by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The practice of segregation in the field of education is

a denial of education itself. Education means more than

the physical school room and the books it contains, and the

teacher who instructs. It includes the learning that comes

from free and full association with other students in the

school. To restrict that association is to deny full and

equal opportunities in the learning process. To restrict

that association is to deny the constitutional guarantee.

Psychologists show us that learning is an emotional as

well as an intellectual process: that it is social as well as

individual, and is best secured in an environment which

encourages and stimulates the best effort of the individual

and holds out the hope that this best effort will be accepted

and used by society.

This point is argued at length in appellants ’ brief. There

fore, we do no more than summarize the opinions of edu

cators here.

In every situation there is the inter-relation of the indi

vidual to his group—which is one that increases with his

maturity. First it is the family, then the local community,

12

then the state, the nation, and finally the entire world. At

no stage of development should any barriers be erected to

prevent the individual from moving from a narrower group

to a larger one, particularly barriers on race. As Lewin

states:

“ The group to which an individual belongs is the

ground on which he stands, which gives or denies him

social status, gives or denies him security and help.

The firmness or weakness of this ground might not be

consciously perceived, just as the firmness of the physi

cal ground on which we tread is not always thought

of. Dynamically, however, the firmness and clearness

of this ground determine what the individual wishes

to do, what he can do, and how he will do it. This is

equally true of the social ground as of the physical.” 5

If education can be made available to all so that each may

develop to the fullest and give his contribution to society,

we will find a peaceful way—rather than one of human de

struction and tragedy—to bring freedom and justice to

peoples.

The American Federation of Teachers believes that seg

regated and discriminatory education is undemocratic and

contrary both to sound educational development as well as

to the basic law of the land—the United States Constitu

tion. We subscribe to the principle that democratic educa

tion provides a total environment which will enable the in

dividual to develop to his capacity, physically, emotionally,

intellectually and spiritually.

For such training to be fully effective, it is essential that

each individual participate, without barriers of race, creed,

or national origin, as a full fledged member in the home,

the community, the state and the nation.

' Kurt Lewin, “Resolving Social Conflict,” p. 174, Harper & Bros.,

13

Accordingly, any restriction, particularly in the form of

segregated and discriminatory schooling, which prevents

the interplay of ideas, personalities, information and atti

tudes, impedes a democratic education and ultimately pre

vents a working democracy.

Conclusion.

Segregation of Negroes in public schools in any of our

States inevitably results in depriving Negroes of educa

tional opportunities provided by those States for white

citizens. Negroes in such States are thereby denied the

equal protection of the laws mandated by the Fourteenth

Amendment. This Court should end these violations of

the constitutional mandate by reversing the judgment in

this case and granting the appellants the relief they pray

for.

Respectfully submitted,

J o h n L igtenberg ,

134 N. La Salle Street,

Chicago 2, Illinois,

Counsel for American Federation

of Teachers, Amicus Curiae.

S elm a M. B orchardt,

Of Counsel.