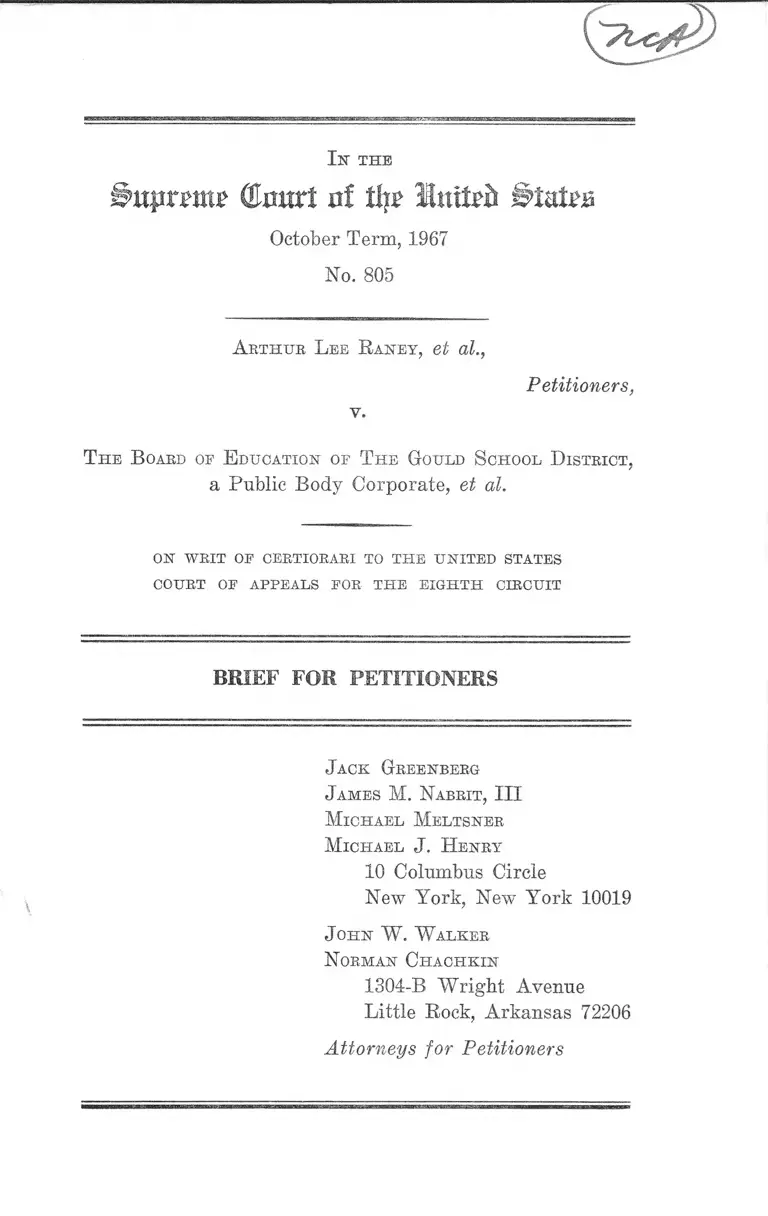

Raney v. Board of Education of The Gould School District Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Raney v. Board of Education of The Gould School District Brief for Petitioners, 1967. 73b074d6-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9ff596e0-d500-4911-aeed-dec1d8f1ee44/raney-v-board-of-education-of-the-gould-school-district-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

§itprari£ (Emirt uf tty Uniteb

October Term, 1967

No. 805

A rthur L ee R aney, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

T he B oard of E ducation of T he Gould School D istrict,

a Public Body Corporate, et al.

on writ of certiorari to the united states

court of appeals for the eighth circuit

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

M ichael J. Henry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J ohn W . W alker

Norman Chacpikin

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little B.ock, Arkansas 72206

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Citations to Opinions Below ......... 1

Jurisdiction......................................................................... 1

Questions Presented.................................................. 2

Constitutional Provision Involved ................................. 2

Statement .................................................. 2

New Construction to Perpetuate Segregation .... 4

Unequal Facilities and Programs ......................... 6

Teacher Segregation ...................................... 8

Intimidation.............................................................. - 9

Denial of Belief by the Courts Below .............-.... 10

Summary of Argument ......-.........................................- 12

A rgument

The Court Below Erred in Dismissing the Com

plaint Without Further Inquiry Into the Feasi

bility of Grade Consolidation or Other Belief

Which Would Disestablish Segregation ............. . 13

A. By Dismissing the Complaint, the Courts Be

low Abdicated Their Besponsibility Under

Brown v. Board of Education to Supervise

Disestablishment of the Segregated System .... 13

B. Use of One School for Elementary Grades

and the Other for Secondary Grades Is a

Seasonable Alternative to a “ Choice” Plan

Which Will Disestablish the Dual System .... 23

PAGE

11

C. Freedom of Choice Is Incapable of Disestab

lishing Segregation in the Gould School Dis

PAGE

trict ....................................................................... 27

Conclusion ........................................................................-...... 38

T able op Cases

Board of Public Instruction of Duval Co., Fla. v.

Braxton, 326 F.2d 616 (5th Cir., 1964) ............ ......... 16n

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

382 U.S. 103 (1965) ............................................ 17, 30n, 35

Brooks v. School Board of Arlington County, 324 F.2d

305 (4th Cir., 1963) ........................... .................. ....... 14

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954);

349 U.S. 294 (1955) ........................... -........2, 3,13,14,15,

20, 22, 28, 30

Buckner v. Board of Education, 332 F.2d 452 (4th

Cir., 1964) ........................................... -..............-......... 15

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U.S. 263 (1964) ........ 14,17n, 31n

Carr v. Montgomery County (Ala.) Board of Educa

tion, 253 F. Supp. 306 (M.D. Ala. 1966) .................- 16n

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ............................ . 31

Cypress v. Non-Sectarian Hospital Assn., 375 F.2d

648 (4th Cir., 1967) ..................-...... ......................... . 19

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W.D. Okla., 1965), aff’d 375 F.2d 158 (10th

Cir., 1967) cert. den. 387 U.S. 931 (1967) ............ 16n, 24

Freeman v. Gould Special School District (No. 19,016

8th Cir.) 4n

PAGE

iii

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1963) ....... 31n

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, Va.,

377 U.S. 218 (1964) ................ .................. ..... 16n, 18, 31n

Kelley v. Altheimer, 378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir., 1967) ....11,12n,

26, 34

Kier v. County School Board of Augusta Co., Va., 249

F. Supp. 239 (W.D. Va., 1966) ................. .. .............- 35

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ....... 16n

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637

(1950) ..................... 34

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) 34

Moses v. Washington Parish School Board, ------ F.

Supp.------ (E.D. La., Oct. 19, 1967) .......................... 27

N.L.R.B. v. Newport News Shipbuilding & Drydock

Co, 308 U.S. 241 (1939) ....................... ....................... 16n

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) .............................. 31n

Schine Chain Theatres v. United States, 334 U.S. 110

(1948) ............... 16n

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir., 1.966) .......... ................. 29n

Smith v. Hampton Training School, 360 F.2d 577 (4th

Cir., 1966) ........................ 15

Smith v. Morrilton, 365 F.2d 770 (8th Cir., 1,966) ....14,17n

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) ..................... 34

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion, 372 F.2d 847, affirmed en bane, 380 F.2d 385

(5th Cir., 1967) cert, denied sub nom. Caddo Parish

School Board v. United States, ------ U.S. ------ , 19

L.ed 2d 103 (1967) ................................_15n, 22, 29n, 30n,

33, 36n

IV

PAGE

United States v. National Lead Co., 332 U.S. 319

(1947) ................................................................ -........... 16n

United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221 U.S. 1 (1910).... 16n

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 346 F.2d

768 (4th Cir., 1965) ...................................................... 16n

Yarbrough v. Hulbert-West Memphis, 380 F.2d 962

(8th Cir., 1967) ............................................................. 15

T able op Statutes and R egulations

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) .......................................................... 1

45 C.F.R. §80.4(c) (1) (1967) .......... 21

45 C.F.R. §181.11 (1967) ................................................. 24

45 C.F.R. §181.54 (1967) ................................................. 32n

Other A uthorities

Conant, The American High School Today (1959) ..... 26

Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, A report of the

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1967 ................ 19, 28n

Southern School Desegregation, 1966-67, a Report of

the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, July 1967 ....19, 28n,

30n, 36n,37n

Survey of School Desegregation in the Southern and

Border States, 1965-1966 ............................................ 30n

The Courts, H.E.W., and Southern School Desegre

gation, 77 Yale L.J. 329 (1967) ..........................19, 20, 21

Title VI, The Guidelines and School Desegregation

in the South, 53 Va. L. Rev. 42 (1967) .......... 3, 21n, 32n

I n the

(Emxrt nf % States

October Term, 1967

No. 805

A rthur L ee R aney, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

T he B oard of E ducation of T he Gould School D istrict,

a Public Body Corporate, et al.

ON writ of certiorari to the united states

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Citations to Opinions Below

The unreported April 26, 1966 opinion of the district

court is reprinted in the appendix, at pp. 12-24. The August

9, 1967 opinion of the court of appeals is reported at 381

F.2d 252 and is reprinted in the appendix at pp. 143-52.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the court of appeals was entered August

9, 1967 and petition for rehearing was denied September

18, 1967, appendix, pp. 153, 154. The petition for writ of

certiorari was filed November 9, 1967 and the writ was

granted January 15, 1968. The jurisdiction of this Court

is invoked under 28 U.S.C. Section 1254(1).

2

Questions Presented

1. Whether the court of appeals erred in denying all re

lief, dismissing the complaint, and declining to order the

district court to supervise the desegregation process on the

ground that the school board was acting in good faith and

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare had ini

tially. approved the board’s plan as facially sufficient to

comply with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

2. Whether—-13 years after Brown v. Board of Educa-

tion,•—a “choice” plan which maintains an all-Negro school

is constitutional in a system with only two nearby school

plants, one traditionally Negro and the other traditionally

white, although assigning elementary grades to one school

and secondary grades to the other is a feasible alternative

assignment method which would immediately desegregate

the system.

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves Section I of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

Statement

Fifteen Negro students and their parents filed a class

action September 7, 1965, to enjoin the Gould School Board

from (1) requiring them and all others similarly situated

“to attend the all-Negro Field School” (2) “providing pub

lic school facilities for Negro pupils . . . inferior to those

provided for whites” (3) “expending any funds for . . .

white Gould Public Schools until and unless the Field

School is made substantially equal” and (4) “otherwise

3

operating a racially segregated system” (A. 3-8). During

trial, November 24, 1965, plaintiffs first learned of a pro

posed school construction program and, with leave of court,

amended the complaint to pray that replacement high school

classrooms he constructed on the premises of the white

Gould High School, rather than at the Negro Field School

(A. 12, 19, 138).

Gould is a small district of about 3,000 population, and

total school enrollment of 879 in the 1965-66 school year

(A. 79-80). Until the 1965-66 school year the district had

not taken any steps to comply with Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, and operated completely separate schools for Negro

and for white pupils with racially separate facilities (A. 31).

All Negro students were instructed in a complex of build

ings known as the Field Schools and all white students were

taught in a complex of buildings known as the Gould

Schools (A. 31). The two complexes are located about 10

blocks from each other; each contains an elementary school

and a secondary school (A. 31, 73).

The school district did not consider undertaking any de

segregation program until the United States Department

of Health, Education, and Welfare issued Guidelines imple

menting Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (A. 121-23).

The district adopted a “ freedom of choice” plan of desegre

gation for all 12 grades, but later obtained approval from

H.E.W. to withdraw three grades from the plan’s operation

for 1965-66 because of “ overcrowding” in those grades

caused by Negro requests to go to the white school. There

were no white requests to go to the Negro school. As a re

sult some 28 Negro pupils, in the 5th, 10th and 11th grades

were turned away from the white school (A. 14, 53-60, 62-

63). During the 1965-66 school year, the enrollment figures

for the school district were as follows (A. 79-80):

4

Grades Negro White

Field Complex 1-12 477 0

Gould Complex 1-12 70 299

During the 1966-67 school year, the second year of “freedom

of choice” , the enrollment figures were as follows .1

Grades Negro White

Field Complex 1-12 477 0

Gould Complex 1-12 71 304

New Construction to Perpetuate Segregation

At the time this action was filed the white Gould High

School, constructed in 1964, was the most modern facility

in the district (A. 89). Adjacent white Gould Elementary

School was constructed in 1947, originally as a high school,

and was subsequently converted to an elementary school

(A. 81-82). The Negro Field Elementary School is also

modern, constructed in 1954; gymnasium and auditorium

were added in 1960 (A. 89-91). Negro high school class

rooms, however, were located until the 1967-68 school year 1

1 The record in this case, like the records in all school desegregation

cases, is necessarily incomplete by the time it reaches this Court. In this

case the 1965-66 school year was the last year for which the record sup

plies desegregation statistics. Information regarding student and faculty

desegregation during the 1966-67 and 1967-68 school years was obtained

from official documents, available for public inspection, maintained by the

United States Department o f Health, Education and Welfare. This in

formation is based upon data supplied to the United States by respondent

school district. Certified copies of these documents and an accompanying

affidavit were deposited with this Court, and served upon opposing counsel

with the petition for writ o f certiorari.

The school board has also been sued by 6 Negro teachers claiming dis

criminatory termination of employment. The record in that case, Freeman

v. Gould Special School District, No. 19,016, 8th Cir. (R. 165-67) shows

that for the school year 1967-68 approximately 80 to 85 Negroes attend

the Gould complex and no whites attend the Field complex.

5

in a building, constructed in 1924, eoncededly obsolete and

in every respect inferior to the white high school (A. 10,16,

130). Promises by the Board to improve the Negro high

school date back to 1954, a decade before any consideration

was given to desegregation, and apparently resulted from

a suit to require equal facilities for Negroes (A. 131-132,

129). Actual construction of a new high school building on

the site of the Field School, however, did not begin until

January, 1967. The new building opened in Fall, 1967, sub

sequent to the decision of the court of appeals (A. 65, 66).

Plaintiffs sought to shift the construction site of the new

high school to the site of the white school by a timely

amendment during a November 24, 1965 hearing, immedi

ately after learning of the proposed construction (A. 137-

138). The district court allowed the amendment (A. 12, 19)

but refused to grant relief in an opinion in April 26, 1966.

Because of illness the court reporter did not complete the

transcript until one year later—April 1, 1967—-thereby de

laying determination of the appeal (A. 140, 152). Because

the construction of the replacement facility at the Negro

school had progressed by the time briefs were filed in the

court of appeals, petitioners asked that court to require a

utilization of the Gould School site as the single secondary

school, and the Field School site as the single elementary

school for the district (A. 144).2 It was urged that such a

utilization was practical, economical, educationally superior

and would disestablish segregation; on the other hand to

permit the racial construction to stand unmodified would

make disestablishment by “choice” plan impossible.

2 Petitioners presented to the court of appeals an affidavit o f their

attorney stating that as o f April, 1967 the outer shell of the new building

was completed but that a number of walls, plumbing facilities and fixtures

and interior walls, the roof and flooring had not been completed (A. 141,

145).

6

At trial, the superintendent admitted that the old Field

High School was clearly a “Negro” school, and probably

would continue to he an all-Negro school if replaced with

a new facility at the Field site (A. 67). He also conceded

that it was inefficient for a small school district to construct

a new secondary school when it already had one. There

would be duplication of libraries, auditoriums, agriculture

buildings, science laboratories, cafeterias, and other facil

ities (A. 74-76). He was asked (A. 76):

Q. “This means that you have to spend a lot more

money for equipment and for materials for the Negro

school in order to just have an equal department with

the white school!”

He answered:

“ I suppose so. It would take more money to build

a new building and equip it.”

Unequal Facilities and Programs

The record shows that for many years prior to con

structing the new Negro high school in 1967 the board

tolerated substantial inequalities between the segregated

schools. The old all-Negro high school, a wooden frame

structure, was admitted by the president of the board to

have been “grossly inferior” to the white high school (A.

10, 16, 130). He said that the reason no money was spent

on the building was that every dollar available had been

exhausted on other uses (A. 130). Nevertheless, a new all-

white high school was constructed at the Gould site (rather

than at the Negro Field site) in 1964 following a tire which

destroyed the old high school building there (A. 83).

7

The Negro Field High School is completely unaccredited;

the Arkansas State Department of Education rates the

Field Elementary School class “ C” (A, 31) and the white

Gould Schools “A ” (A. 10). The Negro school bathrooms

were in a building separated by a walk exposed to weather

(A. 51-52); the white schools had rest rooms in each build

ing (A. 50, 52). There is an agriculture building at the

predominantly white high school, and a hot lunch program

for elementary and secondary students but none at the

Negro site (A. 40-41). The library at the white high school

contains approximately 1,000 books, and a librarian (A. 42-

43). The Negro school has only three sets of encyclopedias,

one purchased a month before the hearing in this case (A.

113-114). These books were kept in the principal’s office,

rather than in a separate library, and the principal, in

effect, functions as librarian, to the extent that such function

is required (A. 114). The superintendent had a complete

lack of knowledge of the extent of library facilities at the

Negro school (A. 42).

The science facilities at the Negro high school were

inferior to those of the predominantly white high school,

even though the former was larger (A. 43-44). Pupils who

attend Gould generally have an individual desk and chair;

the standard pattern at the old Negro school was a folding

table with folding chairs and three students on each side,

sitting at the table (A. 47-48).

The “per pupil” expenditure is less at Field School than

for the formerly all-white, now predominantly white, Gould

School (A. 44). The system has charged “enrollment fees”

to pupils at Field, but not at Gould (A. 44-45). It was

also the practice to require Negro students to pick cotton

in the fields during class time to earn money for school

fund raising projects, and to pay “ enrollment fees” (A.

44-46).

8

Unequal per pupil expenditures are also reflected in

higher student-teacher ratio at the Negro school i.e., the

average class size is larger (A. 59-62). There are 14 teach

ers at Gould, but only 16 teachers at Field although it has

about 130 more students (A. 60-61). The range of Negro

teacher salaries is from $3,870 to $4,500; for white teachers,

the range is from $4,050 to $5,580 (A. 33-39).

There are also disparities in course offerings. Neither

vocational agriculture nor journalism, offered at Gould, are

offered at Field (A. 52-53). There is a similar disparity in

extracurricular activities. The larger Negro school, for

example, has no football program but there is a football

team at the white school (A. 106-107). There is a Future

Farmers of America vocational club at the white school,

but none at the Negro school “because they do not have an

agricultural department” (A. 106).

Teacher Segregation

The school system has no “definite plans for faculty

desegregation” (A. 67, 68). In 1965, the board “did not

have any plans to reassign anybody” (A. 69). By the 1966-

67 school year, the only faculty desegregation which had

taken place was assignment of one part time white “super

visor” to the Negro school3 and for the 1967-68 school year

the only anticipated change was addition of a part time

white teacher at the Negro school. Faculty meetings had

not been integrated (A. 68). At trial, the superintendent

stated that “ . . . we have kept that in the background, Ave

want to get the pupil integration question settled and run

3 See Note 1, supra.

9

ning as smoothly as possible before we go into something

else” (A. 68). When asked whether re-assignments of

faculty members were eventually contemplated, the super

intendent stated that the school system “will attempt to

employ Negro teachers in a predominantly white school on

a limited basis, and particularly in positions that do not

involve direct instructions to pupils” (A. 69). The superin

tendent described the Negro teachers’ academic qualifica

tions as superior to the white teachers. Every Negro

teacher had a bachelor’s degree and two had master’s

degrees. Only one white teacher had a master’s degree;

two have no degree (A. 33, 94-95).

Intimidation

When the PTA at the Negro school began to protest to

the superintendent and the board the deplorable condi

tions at the old Negro high school, the superintendent re

sponded by issuing an order which forbade the Negro PTA

from meeting in the Negro high school (A. 63-64). He

stated:

“ The reason for that is, as I understood, the PTA

had evolved into largely a protest group against the

school board and the policies of the Board. The mem

bers of that organization were the same who planned

to demonstrate against the Gould high school and

had sent chartered bus loads of people to Little Rock

to demonstrate around the Federal Building, who were

getting a chartered bus of sympathizers to come to this

hearing today and it does not seem right to us to

furnish a meeting place for a group of people that is

fighting everything we are trying to do for them”

(A. 64).

10

When questioned whether this meant the Negro high school

parents eonld not have a PTA, the superintendent re

sponded: “ They can have a PTA but they can meet some

where else” (A. 64). He later admitted that he had no

knowledge that any plans for marches or demonstrations

had been made at a PTA meeting, and that all that he

heard to this effect was hearsay (A. 108-109). The super

intendent and some members of the board obtained an in

junction against several civil rights groups, enjoining them

from protesting conditions in the system (A. 63).

Denial of Relief by the Courts Below

The district court denied all relief and dismissed the

complaint on April 26, 1966 (A. 12-25). In its opinion, the

court relied on the fact that the school district had adopted

a plan without court order, that the plan was approved by

the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, and

that some Negro students were attending the “white”

school. With respect to the board’s plan to construct new

high school replacement facilities on the site of the Negro

school, rather than enlarging the previously all-white

school, the court decided that the replacement plan at the

Negro school site was not “ solely motivated by a desire to

perpetuate or maintain or support segregation in the school

system” (A. 24-25).

The court of appeals found that the board was operating

under a “choice” plan which on its face met standards

approved by the circuit and H.E.W.; that there was “no

substantial evidence to support a finding that the board

was not proceeding to carry out the plan in good faith” ;

that progress was being made in equalizing teachers’ sala

ries; and that relief requiring that the replacement con

struction be undertaken at the Gould site could not be

1 1

effective because by the time the appeal was considered

considerable progress had been made in constructing the

building on the Field site,4

Although the court found that “there is no showing

that the new construction added could not be converted at

a reasonable cost into a completely integrated grade school

or into a completely integrated high school when the ap

propriate time for such course arrives” (emphasis sup

plied), it declined to order conversion of one school plant

to use as an elementary school and the other as a secondary

school, on the ground that such relief had not been con

sidered by the trial court. Rather than remanding the

case to the district court for consideration of such relief,

the court affirmed dismissal of the complaint. In addition,

the court took the position that petitioners were not en

titled to a comprehensive judicial decree governing the

operation of the “choice” plan, as ordered by a different

panel of the court in Kelley v. Altheimer, 378 F.2d 483

(8th Cir. 1967):

IJnlike the Altheimer situation, no attack has been

made in the pleadings on the desegregation plan

adopted by the Board. Additionally, we find no sub

stantial evidence to support a finding that the Board

was not proceeding to carry out the plan in good

faith. (A. 151)

A petition for rehearing en banc or by the panel, advert

ing to a conflict between the decision of the panel and the

decision in Kelley v. Altheimer, supra, with respect to

4 Plaintiffs filed notice o f appeal and oral argument was originally

scheduled at the same time as a case involving similar issues, Kelley v.

Altheimer, 378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967). However, the court reporter was

ill for an extended period of time, and was unable to complete the tran

script until April 1st, 1967 (A. 140, 152).

12

standards for approval of desegregation plans, was denied

by the panel September 18, 1967.5

Summary of Argument

By dismissing the complaint, the courts below totally re

fused to supervise the desegregation process in this district

and remitted Negro school children to an inadequate remedy

under Title VI of the Civil Bights Act of 1964. Such a dis

position is unprecedented. It is particularly difficult to com

prehend here because the segregated system has not been

disestablished and because, in formulating desegregation

standards, the Department of Health, Education, and Wel

fare is guided by legal principles emanating from the courts.

There is a clear-cut choice in this district between a sys

tem composed of a reasonably-sized, integrated, elementary

school and similar secondary school, or a system composed

of two inefficiently-small, segregated, combination ele

mentary and secondary schools. Under a “ choice” plan the

Negro school will continue to be all-Negro. On the other

hand, a grade consolidation plan, utilizing one site as an

elementary school and the other site as a secondary school,

will immediately desegregate the system. The “choice” plan

presently in operation is incapable of disestablishing seg

regation, but grade consolidation is sufficiently workable

and attractive a method of administering the system for the

lower courts to be required to consider it on the merits and

order such relief, if not impractical.

6 The panel had attempted to distinguish Kelley stating that the “sup

porting facts in Altheimer are far stronger than those in our present case”

(A. 145). The petition for rehearing en banc or by the panel, which

strenuously objected to this characterization of the cases, is part of the

record in this ease but has not been printed. Petitioners have been in

formed by the office of the clerk of the court of appeals that this petition,

pursuant to the Eighth Circuit practice, was denied by the panel which

heard the Gould appeal and not by the court as a whole.

13

Brown v. Board of Education not only condemns compul

sory racial assignments of public school children, but re

quires “a transition to racially non-discriminatory system.”

That goal is not achieved if schools are still maintained or

identifiable as being for Negroes or for whites. It cannot

be achieved until the racial identification of schools, con

sciously imposed by the state during the era of enforced

segregation, has been erased. The specific direction in

Brown II and general equitable principles require that

school districts, formerly segregated by law, employ affirma

tive action to achieve this end. The courts below should

fashion relief which, while consistent with educational and

equitable principles, employs the speediest means available

to disestablish the dual system and its vestiges, thereby

achieving the unitary nonracial system mandated by the

Constitution.

ARGUMENT

The Court Below Erred in Dismissing the Complaint

Without Further Inquiry Into the Feasibility of Grade

Consolidation or Other Relief Which Would Disestab

lish Segregation.

A. By Dismissing the Complaint, the Courts Below Abdicated

Their Responsibility Under Brown v. Board of Education

to Supervise Disestablishment of the Segregated System.

Petitioners made a timely challenge to construction of

new secondary school classrooms at a Negro school site,

inferior facilities offered Negro students, and continued

operation of a segregated school system in Gould, Arkan

sas. They did not challenge the replacement of a dilapidated

Negro school generally, but sought to require that the con

struction, not scheduled to begin for over a year, take place

on the white school site. To do otherwise would result in

14

perpetuating an unmistakably identifiable Negro school in

a system with only two school plants which had chosen to

adopt a “choice” desegregation plan. The district court

failed to enjoin construction at the Negro site, or to grant

other relief, and dismissed the action. After a court re

porter’s illness delayed consideration of the appeal, the

outer shell of the new classrooms was completed. In the

court of appeals, petitioners sought utilization of the dual

plants as constructed in a manner which would disestablish

the segregated system or, alternatively, entry of a decree

governing disestablishment of the dual system. The court

ruled that it would not consider utilization of one plant for

elementary students, and the other for secondary students,

or entry of a decree governing the desegregation process

because such relief was not sought in the trial court, and

because there was “no substantial evidence to support a

finding that the Board was not proceeding to carry out the

[choice] plan in good faith” (A. 151). It affirmed dismissal

of the complaint.

We submit this result demonstrates a misconception by

the court of its equitable power and responsibility in a

school desegregation case and an erroneous construction of

what took place in the district court. Desegregation is by

its nature a continuous process which requires continuing

supervision by lower courts. Records on appeal are always

somewhat out of date and relief to be effective must be

fashioned with flexibility. In this case where completion of

the construction merely altered the appropriate form of re

lief and where the desegregation of the district was at issue,

dismissal of the complaint was improper abdication of any

jurisdiction over the desegregation process. See Brown v.

Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 301 (1955); Calhoun v.

Latimer, 377 U.S. 263 (1964); Brooks v. School Board of

Arlington County, 324 F.2d 305 (4th Cir., 1963); Smith v.

15

Morrilton, 365 F.2d 770, 783 (8th Cir. 1966); Yarbrough v.

Hulbert-West Memphis, 380 F.2d 962 (8th Cir. 1967); cf.

Smith v. Hampton Training School, 360 F.2d 577, 581 (4th

Cir. 1966); Buchner v. Board of Education, 332 F.2d 452

(4th Cir. 1964) and eases cited. “School desegregation cases

involve more than a dispute between certain Negro children

and certain schools. If Negroes are ever to enter the main

stream of American life as school children they must have

equal educational opportunities with white children.” 6

The fact that petitioners’ request for consideration of a

grade consolidation plan had not been sought in the trial

court does not justify dismissal of this case. The construc

tion to which the consolidation related and the failure of the

board to disestablish segregation, were the subject of timely

attack in the district court. It was not feasible to raise the

issue of consolidation because at the time the trial was held

(November, 1965) the new construction wTas not scheduled

to begin for over a year (January, 1967). At the very least,

the court of appeals was obligated to remand to the district

court to supervise disestablishment of segregation and for a

hearing, with instructions to order grade consolidation if

appropriate. It is submitted that by dismissal of the com

plaint, at a time when segregation is entrenched, the panel

failed to adhere to the rule of Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U.S. 294, 301 (1955) and numerous decisions of lower

courts which hold that district courts must retain jurisdic

tion until a racially nondiscriminatory school system is a

reality. Secondly, by refusing to be influenced by develop

ments subsequent to trial, even though their genesis, the

construction program, was subject to timely attack, the

court took a too narrow view of the power and duty of a

6 United States V. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 847,

affirmed en banc, 380 F.2d 385, 389 (5th Cir. 1967) cert, denied sub nom.

Caddo Parish School Board v. United States, ------ U.S. —, 19 L.ed 2d

103 (1967).

16

federal court of equity in supervising desegregation and

granting relief required by the Constitution.7

7 In the second Brown decision this Court directed that “ in fashioning

and effectuating the decrees, the courts will be guided by equitable prin

ciples.” (349 U.S. at 300). Equity courts have broad power to mold their

remedies and adapt relief to the circumstances and needs of particular

cases as graphically demonstrated by the construction given to 15 U.S.C.

§4 in restraining violations of the Sherman Antitrust Act. The test of

the propriety of such measures is whether remedial action reasonably

tends to dissipate the effects of the condemned actions and to prevent

their continuance, United States V. National Lead Go., 332 U.S. 319 (1947).

Where a corporation has acquired unlawful monopoly power which would

continue to operate as long as the corporation retained its present form,

effectuation of the Act has been held even to require the complete dis

solution of the corporation. United States v. Standard Oil Go., 221 U.S.

1 (1910); Schine Chain Theatres v. United States, 334 U.S. 110 (1948).

Compare N.L.R.B. v. Newport News Shipbuilding & Drydock Co., 308

U.S. 241, 250 (1939); Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, 154

(1965).

Numerous decisions establish that the federal courts construe their

power and duties in the supervision of the disestablishment of state im

posed segregation to require as effective relief as in the antitrust area.

So in Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, Va., 377 U.S. 218

(1964) this Court ordered a public school system which had been closed

to avoid desegregation to be reopened. Carr v. Montgomery County (Ala.)

Board of Education, 253 E. Supp. 306 (M.D. Ala. 1966), ordered twenty-

one (21) small inadequate segregated schools to be closed over a two year

period and the students reassigned to larger integrated schools. Dowell

v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla., 1965),

aff’d 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir., 1967), cert. den. 387 U.S. 931 (1967),

ordered the relief sought here—attendance areas o f schools con

solidated, with one school in each pair to become the junior high school

and the other to become the senior high school for the whole consolidated

area. The Fifth Circuit has held that a district court has power to enjoin

“ approving budgets, making funds available, approving employment con

tracts and construction programs . . . designed to perpetuate, maintain

or support a school system operated on a racially segregated basis.”

Board of Public Instruction of Duval Co., Fla. v. Braxton, 326 F.2d 616,

620 (5th Cir., 1964). The Fourth Circuit and a panel of the Eighth

Circuit have held that a school construction program is an appropriate

matter for court consideration. Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Educa

tion, 346 F.2d 768 (4th Cir., 1965); Kelley v. Altheimer, 378 F.2d 483

(8th Cir., 1967).

The continuous nature o f the desegregation process has consistently

obligated appellate courts to fashion relief despite the occurrence of

events subsequent to judgment in the district court. Such has been the

17

At one point in its opinion the court of appeals states

that the parties had no opportunity to offer evidence on the

feasibility of consolidation and the trial court had.no op

portunity to pass on the issue. If the defect was solely one

of evidence, however, the proper remedy was remand for

further proceedings, not dismissal. Other portions of the

panel’s opinion suggest, however, that it affirmed dismissal

of the complaint for quite different, although also erroneous,

reasons:

Moreover, there is no showing that the Field facilities

with the new construction added could not be converted

at a reasonable cost into a completely integrated grade

school or into a completely integrated high school when

the appropriate time for such course arrives (A. 147).

Utilization of one school as elementary and one as second

ary school is thus acceptable to the court of appeals but

only “when the appropriate time for such course arrives.”

Such language and other portions of the opinions of the

courts below strongly imply that a notion of deliberate

speed—effectuated by a “choice” plan—led to rejection

grade consolidation and not solely that petitioners did not

seek in the trial court altered utilization of classrooms

which were over a year away from construction at the time

of trial. But the time for deliberate speed is over. Over

two years ago this Court stated, “more than a decade has

passed since we directed desegregation of public school

facilities with all deliberate speed. . . . Delays in desegre

gating school systems are no longer tolerable.” Bradley v.

School Board of the City of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103, 105

(1965). In 1964, the Court said: “There has been entirely

common practice of the courts applying Brown, and indeed it had been

the practice of the Eighth Circuit, until this case. Calhoun v. Latimer,

377 U.S. 263 (1964); Smith v. Morrilton, 365 E.2d 770 (8th Cir., 1966).

18

too much deliberation and not enough speed. . . Griffin v.

County School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S.

218, 229.

If the failure of the court of appeals to remand for con

sideration of grade consolidation, or to subject the board

to a comprehensive judicial decree, rather than dismissing

the complaint, rests on a finding by the court that no attack

had been made on the desegregation plan in the trial court,

it rests on a finding which is clearly erroneous. As the

district court said: “ One of plaintiff’s contentions is that

the Court should enjoin the defendant school board from

maintaining a racially segregated system. But the testi

mony discloses that the school board is no longer maintain

ing such a system” (A. 14). The complaint sought to enjoin

the board from compelling any Negroes to attend the all-

Negro school (relief fundamentally inconsistent with a

“choice” plan) and also sought to enjoin the “ operating of

a segregated school system” (A. 8). The trial is replete

with testimony concerning the actual and expected opera

tion of the plan (A. 53-63, 67-71, 75, 95, 96, 101, 102, 109,

117-18, 121-23). Indeed, the district court refused to enjoin

the board from maintaining a segregated system and dis

missed the complaint only because he found the H.E.W.

plan sufficient compliance with the Constitution (A. 14, 24).

Another reason given by the court for dismissal—that

the board was proceeding to carry out the plan in good

faith—reflects a misconception of the role of lower courts

in supervising the desegregation process, see supra, pp.

14-16. The record describes the administration of the Gould

system in detail sufficient to show that whether the board

is acting in good faith or not, its performance is not such

as to permit the lower courts to avoid supervision of the

desegregation process.

19

By their opinions and dispositions the courts below also

indicated that dismissal was strongly influenced by the fact

that the United States Department of Health, Education,

and Welfare had, in their view, controlling responsibility

for supervising school desegregation in Gould because the

district had adopted a plan to conform with Title VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964. To be sure, H.E.W. Guide

lines deserve weight as general propositions of school de

segregation law, and as minimum standards for court-

ordered desegregation plans. The same cannot be said for

H.E.W. administrative approval of a particular school dis

trict’s actual compliance wflth constitutional standards.

With its limited personnel and funds, the Department is

simply unable to ascertain all of the relevant facts about

the performance of an individual school district in the way

that a court hearing can do (especially where II.EW.

Guidelines do not even purport to regulate an issue in the

case—-the effect of construction policy on desegregation).

Because of a shortage of resources, H.E.W.’s “compliance

reviews and enforcement proceedings” are “not planned in

a rational and consistent manner” ; the Department’s ap

praisal of desegregation is often “faulty and inefficient.”

“Manpower limitations” force the Department to fail to

proceed against many districts which are not in compliance.

See Southern School Desegregation, 1966-67, A Report of

the U. S. Civil Rights Commission, July, 1967, pp. 58, 59;

Note, The Courts, H.E.W. and Southern School Desegrega

tion, 77 Yale L.J. 329, 347 (1967). Compare Cypress v.

Non-sectarian Hospital Association, 375 F.2d 648, 658 659

(4th Cir. 1967) where a hospital defended a desegregation

suit on grounds of H.EW. approval, but the court, sitting

en banc, ruled that H.E.W.’s compliance mechanism was

so inefficient that it was not an equitable defense to a suit

based on deprivation of constitutional rights. H.E.W.

“necessarily concerns itself with every school district in

20

the country” so that to hold that “H.E.W. has preempted

jurisdiction would relegate the courts to the purely appel

late role of reviewing the particular treatment afforded a

school district by the government.” Note, 77 Yale L. J.

321, 323 (1967j. The practical effect of such rule would be

to reduce the rate of desegregation for H.E.W.’s enforce

ment difficulties are enormous. Unfortunately, the sorry

statistics of southern school desegregation, see infra p. 36,

reflect the inability of the Department to police, effectively,

compliance with the Guidelines.

Dismissal of school desegregation cases on the ground

that school boards are subject to H.E.W. jurisdiction is a

step which would thwart efforts to secure compliance with

Brown v. Board of Education for still another reason.

H.E.W. depends on the courts to enunciate the substantive

standards on which its Guidelines, and their enforcement,

are based, “to chart the outer limits of Title VI and to

enforce nondiscrimination in those areas Title VI is not

broad enough to cover.” 8 A recent study of judicial and

administrative efforts to achieve desegregation put the

matter clearly:

“At least under present HEW policy, the Office of Edu

cation’s ability to attack discrimination will only grow

and evolve as the constitutional requirements them

selves do, for the government is only attempting to

impose the same conditions required by the Fourteenth

Amendment. The result, of course, is that future

changes in HEW standards to permit attacks on the

worst examples of racial imbalance or the elimination

of freedom of choice as a legitimate desegregation plan

will only occur if courts hold such phenomena and

practices unconstitutional. Until the courts strike down

s Note, 77 Yale L.J. 321, 329 (1967).

21

the free choice plan, the Office of Education will not

move, and once the court so holds, the Office of Educa

tion has no choice but to act accordingly.” 9

The facts of this case are an excellent illustration of the

Department’s need to rely on judicially determined stan

dards. While the Guidelines recognize that it is the re

sponsibility of a school system to adopt and implement a

desegregation plan which will eliminate the dual school

system, and all other forms of discrimination, as expedi

tiously as possible, they nowhere direct themselves to the

effect of school construction policies on the achievement

of this goal and do not supply standards against which

such policies may be measured. Thus, the dismissal of the

complaint in this case remitted Negro children and their

parents to regulations which do not contain standards

directed to an injury they claim and are unlikely to do so

until such standards are judicially recognized.

Additional factors make compelling the conclusion that

a district court may not refuse to supervise the desegrega

tion process for this reason. The regulations drafted by

H.E.W. pursuant to Title VI make compliance satisfactory

if a school system is subject to a final order of a court of

the United States, 45 C.F.R. §80.4(c)(1)(1967). This is

clear recognition that the Department will not insist on

standards different from those adopted by the courts.10

9 Ibid.

10 That H.E.W. accepts free choice plans as establishing the eligibility

of a district for federal aid does not of course mean that such plans are

constitutional. For the available evidence indicates that H.E.W. has

approved such plans, despite the massive evidence o f their inability to

disestablish the dual system, only because they have received approval in

the courts, and it is felt inappropriate to enforce requirements more

stringent than those imposed by the Fourteenth Amendment. See the

materials collected in Dunn, Title VI, The Guidelines and School Desegre

gation in the South, 53 Ya. L. Rev. 42 (1967); Note, 77 Yale L.J. 321

(1967).

22

Indeed it has been universally recognized that the Guide

lines were drafted in light of prevailing judicial standards,

e.g. United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

supra, 372 F.2d 847, 851. In such circumstances, dismissal

in deference to H.E.W. would be to inhibit the growth of

departmental standards. The courts would defer to H.E.W.

and H.E.W. would defer to the courts. A dangerous circular

pattern of negative, rather than positive, enforcement

would be created.

Petitioners complained, moreover, of a violation of their

constitutional rights; not statutory rights which they may

have under Title VI of the Civil Eights Act which regulates

the relationship between the federal government and its

grantees. The courts may not abdicate their responsibility

to confront the performance of school boards in terms of

the constitutional standards of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Petitioners have been unable to locate any decision which

holds to the contrary. In this regard, the courts below

fundamentally misconstrued the rule of burden of proof

in school desegregation cases. The burden of proof is not

on Negro students to demonstrate that a school system

which undisputedly has been segregated for generations

(and which still maintains one of its two school plants as

all-Negro) is still segregated, but on the school board to

demonstrate that its desegregation plan desegregates the

system, Brown v. Board of Education, supra. That burden

is not carried solely by adoption of a “choice” plan when

another plan which apparently is reasonable and practical

will immediately desegregate the system.

23

B. Use of One School for Elementary Grades and the Other

for Secondary Grades Is a Reasonable Alternative to a

“ Choice” Plan Which Will Disestablish the Dual System.

Petitioners do not ask this Court to order grade consoli

dation in this district but to consider the standard under

which such an order by the district court would he appro

priate. We believe that the proper course for this Court

to follow is to vacate the judgment in order that the feasibil

ity of consolidation may be determined in the courts below,

with instructions to order such relief, if not impractical,

because it will more speedily disestablish the dual system.

We restrict ourselves, therefore, to a showing that (1) such,

utilization is shown by this record to be a sufficiently

workable and attractive method of administering the sys

tem for the lower courts to be required to consider it on

the merits, infra pp. 23-27, and (2) that the “freedom of

choice” plan presently in operation is incapable of dis

establishing segregation, infra pp. 27-38.

Because there are only two nearby schools in this small

district, there is a clear choice between a system composed

of reasonably-sized, integrated, elementary and secondary

schools, or a system composed of two inefficiently-small,

combination elementary and secondary schools. The super

intendent’s concession that under the “choice” plan the

replaced Negro school would probably continue to be all-

Negro, actual experience under the plan, as well as the

obvious educational inefficiency and undesirability of the

dual schools constitute a reasonable basis for providing

that one site shall be used for an elementary school and

the other site for a secondary school. (The dual school

system might also be completely eliminated with a mini

mum of administrative difficulty in this district, where

both races reside throughout, by a geographic assignment

24

plan, but such a plan would not end the manifest inefficiency

of operating two small schools serving grades 1-12.) The

system’s school buildings as constructed are adaptable to

changed usages and whatever additional cost might be in

volved in alteration, as the court of appeals recognized,

is reasonably balanced against the continued extra operat

ing cost of the inefficient dual system (A. 147).

The school facilities of the district ideally lend themselves

to a plan of consolidation, which is, as recongized by the

H.E.W. Guidelines and court decisions, an appropriate

method of disestablishment:

In some cases, the most expeditious means of deseg

regation is to close the schools originally established

for students of one race, particularly where they are

small and inadequate, and to assign all the students

and teachers to desegregated schools. Another appro

priate method is to reorganize the grade structure of

schools originally established for students of different

races so that these schools are fully utilized, on a de

segregated basis, although each school contains fewer

grades. (45 CFR §181.11)

See Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, supra. Until

1967, the traditionally white Gould High School was the

most modern facility in the district, having been completed

in 1964 (A. 89). The immediately adjacent Gould Elemen

tary School was originally constructed for use as a high

school, and was subsequently converted to an elementary

school (A. 81-82). If the Gould Elementary School were

converted back to use as a secondary school, the Gould site

would be clearly suitable for all the secondary students

in the district (A. 145). The 1966-67 secondary enrollment

25

of the district was 360 for grades 8-12, while the total

enrollment at the Gould School was 375 (grades 1-12).11

The all-Negro Field Elementary School is also a modern

facility, constructed in 1954 with subsequent additions (A.

89-91). The gymnasium is adequate for both the present

number of Negro elementary and Negro high school stu

dents, so that it would also be suitable for use by all of

the elementary students in the system. The new building

constructed by the system for use as the Negro high school

is adjacent to the Field Elementary School, and can easily

be furnished as an addition to the elementary school—

which would make the combined Field School adequate for

all of the elementary students in the district. The enroll

ment for the district in 1966-67 was 492 for grades 1-7,

while the total enrollment at the Field School was 477

(grades 1-12).12

If there is some impediment to consolidation which the

record does not reveal, the board should have the oppor

tunity, on remand, to prove it, but absent some serious

educational or practical deficiency in such a course, the

board should not be permitted to reject it in favor of an

assignment system which does not disestablish the dual

system. For unless the board is required to cease main

taining dual facilities, a predominantly segregated school

system will be fastened upon the community for at least an

other generation, and all students—Negro and white—will

continue to pay the price of the inefficiency caused by oper

ating a dual system in such a small district. This is graphi

cally illustrated by the disparity in course offerings at

the two high schools. If all students were attending the

same high school, everyone would have the opportunity

11 See footnote 1, supra.

12 Ibid.

26

to take courses such as journalism or agriculture, as well

as other courses which would he available because a higher

total of students would elect them. Negroes who have no

football or track programs would be able to participate in

those sports. The basic sciences, chemistry and biology,

are offered only in alternate years at Gould while they are

offered every year at Field. There is no Future Farmers

of America Program at Field only because no agriculture

course is offered. In a consolidated system, all students

would have the opportunity to take each of these courses

every year.

The sad fact is that the board’s failure to consolidate

grades not only perpetuates segregation but deprives both

Negroes and whites of significant educational opportunities.

To be sure, the Fourteenth Amendment may not require

that school administrators operate their system in the

most efficient manner, but their failure to do so, with

out explanation, demonstrates the racial purpose of the

“choice” assignment plan, infra, pp. 27-38.13 It is no accident

that the board ignores the recommendations of the most

important study of secondary education that has been made

in this country, James Bryant Conant’s, The American

High School Today (1959) which gives highest priority

in educational planning to the elimination of small high

schools with graduating classes of less than one hundred.14

13 A similar inference was made in Kelley v. Altheimer, 378 F .2d 468

(8th Cir. 1967). There the school board added additional classrooms at

each o f two complexes, one traditionally maintained for Negroes the other

for whites:

We conclude that the construction of the new classroom buildings

had the effect of helping to perpetuate a segregated school system

and should not have been permitted by the lower court.

14 “ The enrollment of many American public high schools is too small

to allow a diversified curriculum except at exorbitant expense . . . ‘The

prevalence of such high schools— those with graduating classes of less

than one hundred students— constitutes one of the serious obstacles to

27

See Moses v. Washington Parish School Board, — F. Supp.

— (E.D. La., Oct. 19, 1967) (“Free choice” plan “wasteful

in every respect” ; geographic zones ordered).

The court of appeals recognized that there is substantial

evidence that consolidation is a feasible alternative to “ free

dom of choice” when it found that “there is no showing that

the Field facilities with the new construction added could

not be converted at a reasonable cost into a completely

integrated grade school or into a completely integrated

high school when the appropriate time for such a course

arrives. We note that the building now occupied by the

predominantly white grade school had originally been

built to house the Gould High School” (emphasis supplied)

(A. 145). Given the apparent feasibility of grade consoli

dation and the deficiencies of a “choice” plan in this district,

see infra pp. 33-35, the court of appeals had an obligation

to fashion a remedy equal to the task of disestablishing

the dual structure. Instead, it erroneously affirmed dis

missal of the complaint.

C. Freedom of Choice Is Incapable of Disestablishing Segrega

tion in the Gould School District.

The duty of the school board was to convert the dual

school system it had created into a unitary non-raeial

system. Although it had an alternative which would have

disestablished the dual system immediately, and with less

educational inefficiency, the board adopted a method whose

good secondary education throughout most of the United States. I believe

such schools are not in a position to provide a satisfactory education for

any group of their students—the academically talented, the vocationally

oriented, or the slow reader. The instructional program is neither suffi

ciently broad nor sufficiently challenging. A small high school cannot by

its very nature offer a comprehensive curriculum. Furthermore, such a

school uses uneconomieally the time and efforts of administrators, teachers,

and specialists, the shortage of whom is a serious national problem”

(p. 76).

28

success depended on the ability of Negroes to unshackle

themselves from the psychological effects of the dual system

of the past, and to withstand the fear and intimidation of

the present and future. Only the “ choice” plan selected by

the board subjects Negroes to the possibility of intimida

tion or gives undue weight to the very psychological effects

of the dual system that this Court found unconstitutional

in Brown v. Board of Education. Nor did the board intro

duce evidence to justify adoption of a method, 11 years

after Brown, which if it could disestablish the dual system

at all, would require a much longer period of time than

available alternatives. The failure of the board to show

the existence of any administrative reasons, such as this

Court contemplated in Brown II might justify delay, made

it error for the courts below to abdicate to an adminis

tratively supervised “choice” plan.

After Brown, southern school boards were faced with the

problem of “effectuating a transition to a racially non-

discriminatory system” (Brown II at 301). The easiest

method, administratively, was to convert the dual attend

ance zones into single attendance zones, without regard to

race, so that assignment of all students would depend only

on proximity and convenience.* 16 With rare exception, how

ever, southern school boards, when finally forced to begin

desegregation, rejected this relatively simple method in

favor of the complex and discriminatory procedures of

pupil placement laws and, when those were invalidated,

switched to what has in practice worked the same way—

the so-called free choice.16

16 Indeed, it was to this method that this Court alluded in Brown II

when it stated “ [t]o that end, the courts may consider problems related

to administration arising from revision of school districts and attendance

areas into compact units to achieve a system of determining admission to

the public schools on a non-racial basis” (349 U.S. at 300-301).

16 According to the Civil Rights Commission, the vast majority of school

districts in the south use freedom of choice plans. See Southern School

29

Under so-called free choice students are allowed to attend

the school of their choice. Most often they are permitted to

choose any school in the system. In some areas, they are

permitted to choose only either the previously all-Negro

or previously all-white school in a limited geographic area.

Not only are such plans more difficult to administer (choice

forms have to be processed and standards developed for

passing on them, with provision for notice of the right

to choose and for dealing with students who fail to exer

cise a choice),17 they are, in addition,—as experience dem

Desegregation, 1966-67, A Report of the U. S. Commission on Civil

Rights, July, 1967. The report states, at pp. 45-46:

Free choice plans are favored overwhelmingly by the 1787 school

districts desegregating under voluntary plans. All such districts . . .

in Alabama, Mississippi, and South Carolina, without exception, and

83% of such districts in Georgia have adopted free choice plans. . . .

17 Section II of the decree appended by the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, to its recent decision in United States v.

Jefferson County Board of Education, supra, shows the complexity of

such plans. That court had previously described such plans as a

“haphazard basis” for the administration of schools. Singleton v. Jackson

Municipal Separate School District, 355 F.2d 865, 871 (5th Cir. 1966).

Under such plans school officials are required to mail (or deliver by way

of the students) letters to the parents informing them of their rights to

choose within a designated period, compile and analyze the forms re

turned, grant and deny choices, notify students of the action taken and

assign students failing to choose to the schools nearest their homes. Vir

tually each step of the procedure, from the initial letter to the assignment

o f students failing to choose, provides an opportunity for individuals

hostile to desegregation to forestall its progress, either by deliberate mis-

performanee or non-performance. The Civil Rights Commission has re

ported on non-complainee by school authorities with their desegregation

plans:

In Webster County, Mississippi, school officials assigned on a racial

basis about 200 white and Negro students whose freedom of choice

forms had not been returned to the school office, even though the

desegregation plan stated that it was mandatory for parents to exer

cise a choice and that assignments would be based on that choice

[footnote omitted]. In McCarty, Missouri after the school board had

30

onstrates (infra pp. 33, 36)—far less likely to disestablish

the dual system.

Under “choice” plans, the extent of actual desegregation

varies directly with the number of students seeking, and

actually being permitted, to transfer to schools previously

maintained for the other race. It should have been obvious,

however, that white students—in view of general notions

of Negro inferiority and the hard fact that far too often

Negro schools are vastly inferior to those furnished whites

see supra pp. 6-8—would not transfer to formerly Negro

schools; and, indeed, very few have.18 From the beginning

the burden of disestablishing the dual system under free

choice was thrust upon Negro children and their par

ents, despite this Court’s admonition in Brown II (349 U.S.

294, 299) that “ school authorities had the primary responsi

bility.”

The notion that the making available of an unrestricted

choice satisfies the Constitution, quite apart from whether

significant numbers of white students choose Negro schools

or Negro students white schools, is, we submit, funda

distributed freedom o f choice forms and students had filled out and

returned the forms, the board ignored them.

Survey of School Desegregation in the Southern and Border States,

1965- 1966, at p. 47. Given the other shortcomings of free choice plans,

there is serious doubt whether the constitutional duty to effect a non-

raeial system is satisfied by the promulgation of rules so susceptible of

manipulation by hostile school officials. As Judge Sobeloff has observed:

A procedure which might well succeed under sympathetic administra

tion could prove woefully inadequate in an antagonistic environment.

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 345 F.2d 310 (4th

Cir, 1965) (concurring in part and dissenting in part).

18 “During the past school year, as in previous years, white students

rarely chose to attend Negro schools.” Southern School Desegregation,

1966- 67 at p. 142; United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

supra, 372 F.2d at 889.

31

mentally inconsistent with the decisions of this Court in

Brown I and II ; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958); Brad

ley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, supra, and the

entire series of cases it has decided.19 Brown contemplates

complete reorganization. It condemns not only compulsory

racial assignments of public school students, but also the

maintenance of a dual public school system based on race—

where some schools are maintained or identifiable as being

for Negroes or others for whites. It presupposed a major

reorganization of the educational systems of the affected

states, the extent of which is suggested by the fact that the

court took an additional year to consider the problem of

relief. The direction in Brown II, to the district courts that

they might consider

problems related to administration, arising from the

physical condition of the school plant, the school trans

portation system, personnel, revision of school districts

and attendance areas into compact units to achieve a

system of determining admission to the public schools

on a non-racial basis, and revision of local laws and

regulations which may be necessary in solving the fore

going problems (349 U.S. at 300-301)

amply demonstrates the magnitude and thoroughness of the

reorganization envisaged.

If this Court in Brown I and II had thought that a “ra

cially non-discriminatory system” would be achieved al

though Negro and white students would continue as before

to attend schools designated for their race, none of the

quoted language was necessary. It would have been suffi

19 See Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ; Calhoun v. Latimer, 377

U.S. 263 (1964) ; Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964); Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683

(1963).

32

cient merely to say “compulsory racial assignment shall

cease.” But the Court did not stop there. Bather it ordered

a pervasive reorganization so that the system would be

transformed into one that was “unitary and nonracial,” one

in which schools would no longer be identifiable as being

for Negroes or whites. That students have been permitted

to choose a school does not destroy the racial identification

of that school if it continues to serve students of one race,

is staffed solely by teachers of that race, or is treated as a

Negro or white school by school officials. The only way

racial identifications—consciously imposed by the state dur

ing the era of enforced segregation—can be erased is by

having schools serve students of both races, through

teachers of both races. This is what we think disestablish

ment of the dual system means and this is what we submit

the Brown decisions require.

Given the premise of Brown v. Board of Education—that

segregation in public education had very deep and long

term effects upon Negroes—it is not surprising that indi

viduals, reared in that system and schooled in the ways of

subservience (by segregation in schools and every other

conceivable aspect of existence) who are given the oppor

tunity to “make a choice,” chose, by inaction, that their

children remain in Negro schools.20 By making the Negro’s

exercise of choice the critical factor, school authorities have

20 In its Revised Statement of Policies for School Desegregation Plans

Under Title VI o f the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (referred to as the Guide

lines), the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare states (45 CER

§181.54) :

A. free choice plan tends to place the burden of desegregation on

Negro or other minority group students and their parents. Even when

school authorities undertake good faith efforts to assure its fair

operation, the very nature of a free choice plan and the effect of

longstanding community attitudes often tend to preclude or inhibit

the exercise of a truly free choice by or for minority group students.

(Emphasis added.)

33

insured desegregation’s failure. Moreover, intimidation, a

weapon well-known throughout the south, has been em

ployed to deter transfers. Every community pressure mili

tates against the affirmative choice of white schools by Ne

gro parents. Here the heavy hand of segregation did its

work in overt fashion.

First, “ the only school desegregation plan that meets

constitutional standards is one that works” (United States

v. Jefferson County Board of Education, supra, 372 F.2d at

p. 847 (emphasis in original)) and the Gould plan has not

worked. In both first and second year of its operation only

about 70 Negro pupils attended the white school and no

whites “chose” to attend the Negro school. The number

seems to have climbed only slightly in the 1967-68 school

year.21 In the first year of the plan several Negroes “chose”

the white school but were refused admission due to over

crowding, an overcrowding caused in part by the fact that

no whites “chose” to attend the Negro school. Only one

teacher has been assigned to a desegregated faculty, and

that teacher on a part time basis. No Negro teacher has

been assigned to teach at the white school. In short, four

teen years after Brown, “ freedom of choice” has not and

does not appear capable of disestablishing segregation.

Second, the record shows active intimidation of the Negro

community. The PTA of the Negro school was prohibited

by the superintendent from meeting at the school once it

began to protest conditions there, and an injunction was

obtained by the board of education against public protests

concerning school conditions (A. 63-64).

21 In June, 1967, the superintendent informed the Department of

Health, Education and Welfare that he anticipated an increase of only

14 Negro students in the white school for the 1967-68 school year, the

third year o f desegregation and that again no whites would attend the

Negro school, see note 1, supra.

34

Third, the degree of inequality between the Negro and

white high schools which has been maintained for so long

has inevitably communicated to the Negro community that

the board could not be trusted to administer a “ freedom

of choice” plan fairly, and that the choice offered was

not really free. Until 1965, the Negro high school had

such a poor physical plant and program that it was com

pletely unaccredited by the State of Arkansas, while the

white high school had an “A ” rating (A. 10, 16, 31, 83, 130).

Long promised reconstruction took place only after adop

tion of a desegregation plan (itself required to obtain fed

eral funds) when a new school would have the possible

effect of limiting the number of Negro transferees under

the choice plan. Not only has the practice of segregation

followed by this district been unconstitutional since 1954,

but the “gross inferiority” of the separate public school

facilities provided for Negro students has been unconsti

tutional at least since 1938, Missouri ex rel. Gaines v.

Canada, 305 U.S. 337; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629

(1950); McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637

(1950). The court of appeals erred, fundamentally, in ig

noring the relevance of these historic inequalities to the

validity of the choice plan and the need to explore alter

nate methods of disestablishment.

Fourth, the character of the new replacement construc

tion on the traditional segregated site (and that no ra

tional educational purpose is apparent behind such dual

construction) is not susceptible to any other interpretation

by the community, Negro and white, than that the board

wishes to maintain a segregated system, with one school

intended for whites and the other intended for Negroes,

cf. Kelley v. Altheimer, 378 F.2d 483, 490, 496 (8th Cir.

1967). This was just as unambiguous an act as re-writing

the word “white” over the door of the Gould School and

the word “Negro” over the door of the Field School—and

35

is just as coercive to Negroes who have traditionally

been informed by the segregated system that they were

not wanted in “white” institutions, and to whites who have

been informed that it was not proper for them to be in

“Negro” institutions. The replacement construction here

has precisely the same effect on the “freedom” in a “free

dom of choice” plan as does the maintenance of all-white

and all-Negro faculties at various schools in a system. Cf.

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 382 U.S.

103 (1965); Kier v. County School Board of Augusta Co.,

Va., 249 F. Supp. 239, 246 (W. D. Va., 1966).

Fifth, the integration of faculty is a factor absolutely

fundamental to the success of a desegregation plan, for

a school with a Negro or white faculty will always be a