Defendant's Correction to Page 35 of Brief (Detroit Board of Education v. Bradley)

Public Court Documents

August 12, 1972

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Defendant's Correction to Page 35 of Brief (Detroit Board of Education v. Bradley), 1972. 6915ce68-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a0167ab0-3e1c-47fd-94d2-2c1138d9efe5/defendants-correction-to-page-35-of-brief-detroit-board-of-education-v-bradley. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

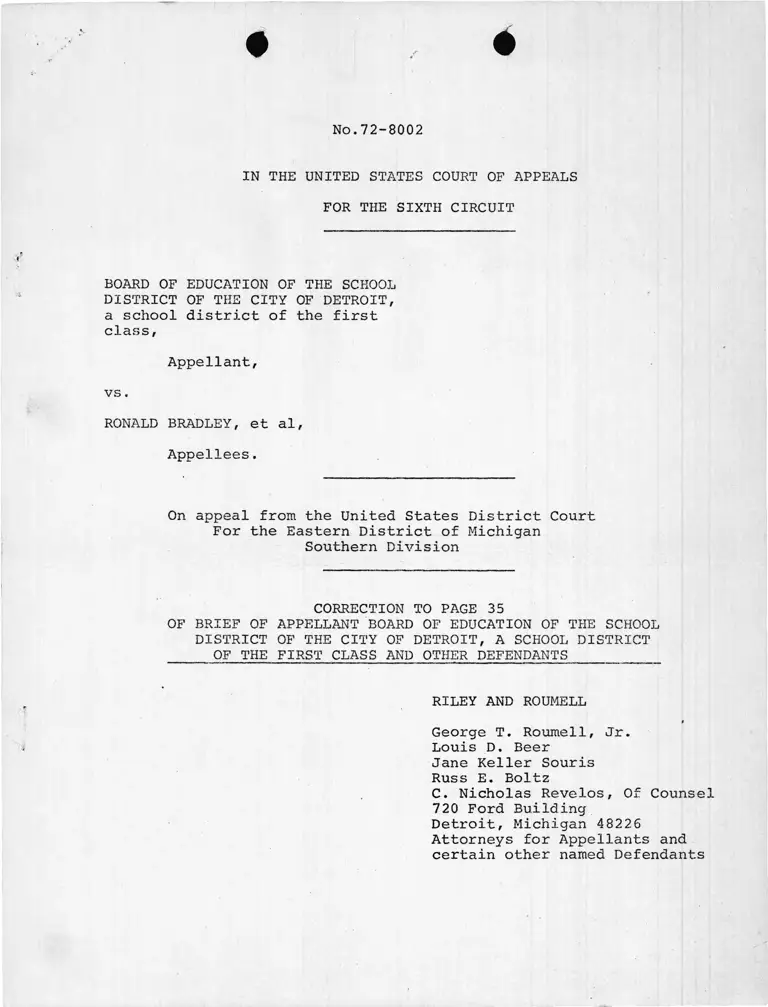

No.72-8002

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE SCHOOL

DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF DETROIT,

a school district of the first

class,

Appellant,

v s .

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

Appellees.

On appeal from the United States District Court

For the Eastern District of Michigan

Southern Division

CORRECTION TO PAGE 35

OF BRIEF OF APPELLANT BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE SCHOOL

DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF DETROIT, A SCHOOL DISTRICT

OF THE FIRST CLASS AND OTHER DEFENDANTS * *

RILEY AND ROUMELL

*

George T. Roumell, Jr.

Louis D. Beer

Jane Keller Souris

Russ E. Boltz

C. Nicholas Revelos, Of Counsel

720 Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Attorneys for Appellants and

certain other named Defendants

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 72-8002

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE SCHOOL

DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF DETROIT,

a school district of the first

class,

Appellant,

vs.

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

Appellees.

___________________________________________ /

CORRECTION TO PAGE 35

OF BRIEF OF APPELLANT BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE SCHOOL

DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF DETROIT, A SCHOOL DISTRICT

OF THE FIRST CLASS AND OTHER DEFENDANTS

In doing a brief under the time constraints, there are

bound to be some typographical errors. In our original Brief,

there is one page in which the word,"contacts" was typed

"contracts", which changes completely the meaning of the

sentence. Therefore, we have included herein a new Page 35

with the new corrected sentence which has been underlined. In

other words, in the fifth line from the top of the page, the

word "contacts" is now correctly typed.

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Attorneys for Appellants and

certain other named Defendants

ILEY AND ROUMELL

I!George Tl Roumell ,* th

720 Ford Building

August 21, 1972.

#

In determining what part of the "substantial" but not

principal role the Detroit Board played in causing the current

condition or what link it had to other units of government, the

only recourse is to the record. That record reveals rather

limited contacts between the Board and the City Planning Commis

sion, various model neighborhood agencies, the Urban Renewal

Division and Department of Parks and Recreation of the City of

Detroit, none of which involved the slightest segregatory purpose

or effect. (Henrickson, de jure,Tr.3515-18) (App.IVa 113-116).

As to the role of the acts of the Detroit Board found to

be v/rongful in causing the current condition of segregation

Plaintiffs proferred to the Court their finding of fact which

contained only the opinion testimony of several experts to the

effect tnat all—Black and all—White schools tended to reinforce

a feeling of separateness on the part of both races, which, in

turn, manifested itself to some undefinable degree in the choice

of residence in uniracial neighborhoods on the part of both races.

The mind boggles at the meaning of this assumed, unmeasured

phenomenon against the standard of proximate cause. First, the

findings of the District Court as to specific acts of discrimina

tion relate to a relatively small proportion of the total school

district: the construction of one specified elementary school, out

of a total school construction program involving a multitude of schools

several instances of Black-to-Black busing; and the maintenance of six

-35-