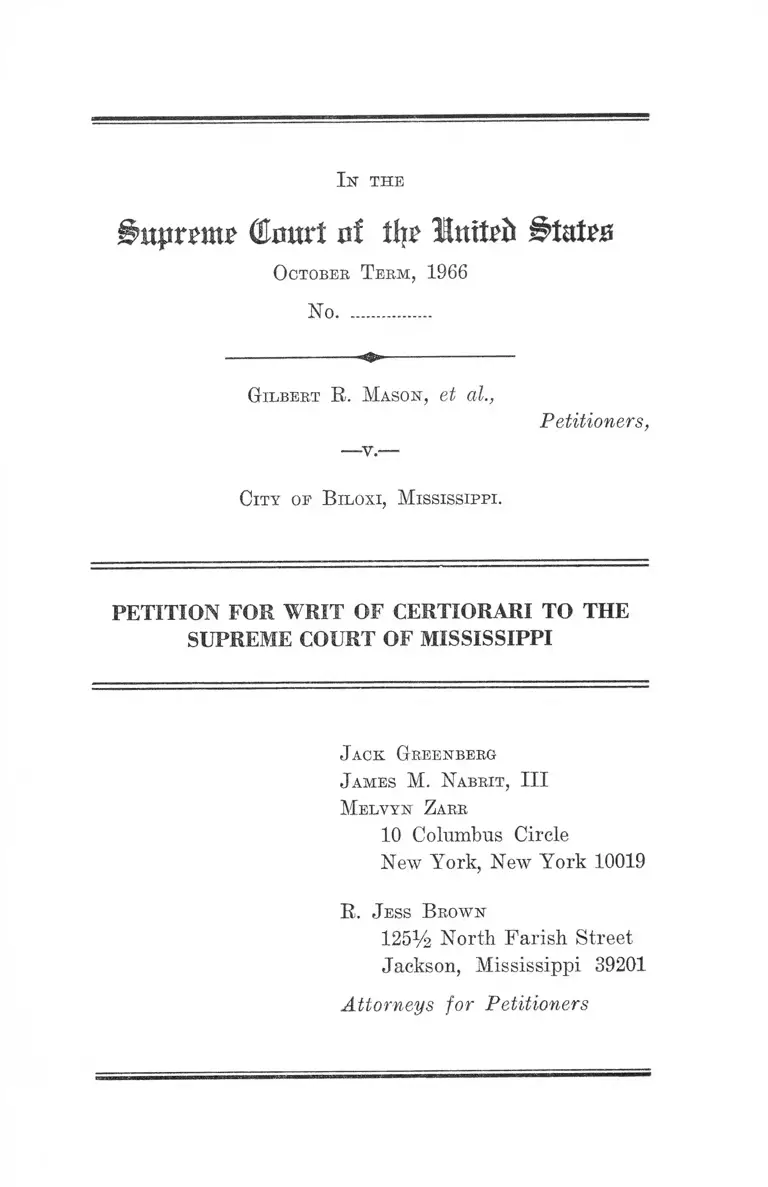

Mason v. City of Biloxi, MS Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Mississpi

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mason v. City of Biloxi, MS Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Mississpi, 1966. b5839d26-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a068a44f-a4d2-4917-8c57-1efb23640ed8/mason-v-city-of-biloxi-ms-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-mississpi. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

(Emtrt of % Inttefc

October Teem, 1966

No..................

In the

Gilbert R. Mason, et al.,

— y .—

Petitioners,

City oe B iloxi, Mississippi.

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF MISSISSIPPI

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

R. Jess B rown

125% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion B elow ...................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 2

Question Presented ............................................................ 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 3

Statement ............................................................................. 10

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

B elow ................................................................................. 14

Reason for Granting the Writ ...................................... 15

The Decision Below Approves Enforcement of a

State-Supported Policy of Racial Discrimination

in Facilities Which Are Significantly Impressed

With Federal, State and Local Financial Contribu

tions, Programs and Policies and Conflicts With

Decisions of This Court .......................................... 15

Conclusion- ........................................................................... 22

A ppendix

Judgment of Supreme Court of Mississippi ....... la

House Document No. 682, 80th Cong., 2nd Sess..... 2a

11

T able oe Cases:

PAGE

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 IT. S. 249 (1953) ....................... 19

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 (1961) ....................................................................... 16

Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442 (1900) .......................... 21

City of New Orleans v. Barthe, 376 IT. S. 189 (1964) .. 19

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U. S. 129 (1964) ..................... 21

Eaton v. Grubbs, 329 F. 2d 710 (4th Cir. 1964) ........... 16

Evans v. Newton, 382 U. S. 296 (1966) ...............16,19, 20

Griffin v. Maryland, 378 IT. S. 130 (1964) ................... 19

Harrison County v. Guice, 244 Miss. 95, 140 So. 2d 838

(1962) .............................. 11,13

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 IT. S. 879 (1955) ....... 19

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 (1946) ....................... 16

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350

IT. S. 877 (1955) .............................................................. 19

New Orleans Park Association v. Detiege, 358 IT. S.

54 (1958) ........................ 19

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1 (1948) .......................... 19

Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323 F.

2d 959 (4th Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 376 IT. S. 938

(1964) ............................................ 15,16

Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, Inc., 336 F. 2d

630 (6th Cir. 1964) ..................... 16

United States v. Harrison County, S. D. Miss. No. 2262 11

Ill

PAGE

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U. 8. 526 (1963) ....................... 19

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963) ................. 19

S t a t u t e s :

28 TJ. S. C. §1257(3) .......... ............................................. 2

Act of August 13, 1946, Public Law 727, 79th Cong.,

2nd Sess., 60 Stat. 1056 ..............................................3,16

Act of June 30, 1948, Public Law 858, 80th Cong., 2nd

Sess., 62 Stat. 1172 ........................................................4,17

Miss. Code Ann., 1942, Rec., §2409.7 (1964 Supp.) .....6,13

Miss. Code Ann., 1942, Rec., §4065.3 ................................ 7, 20

Miss. Code Ann., 1942, Rec., §8516.3.................................. 4,18

Miss. Code Ann., 1942, Rec., §8516.4.............................. 18

Isr the

(Enurt xrf tlu InitTft States

October Term, 1966

No..................

Gilbert R. Mason, et al.,

—v.-

Petitioners,

City of B iloxi, Mississippi.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF MISSISSIPPI

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Mississippi entered

in the above-entitled case on March 21, 1966. Rehearing

was denied on April 11, 1966.

Opinion Below

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Mississippi is

reported at 184 So. 2d 113 and is set forth in the Appendix,

infra, p. la. No opinion accompanied that judgment or the

denial of rehearing.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Mississippi was

entered on March 21, 1966 (E. 734); rehearing was denied

April 11, 1966 (E. 735).

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U. S. C. §1257(3), petitioners having asserted below and

asserting here deprivation of rights, privileges and im

munities secured by the Constitution of the United States.

Question Presented

A beach 24 miles in length has been constructed along the

coast of the State of Mississippi with federal, state and

local funds, pursuant to governmental programs and poli

cies designed to promote the health and recreation of all

citizens; the Supreme Court of Mississippi has declared

title to the pumped-up land in the abutting private land-

owners ; the white public is invited to and freely does use

the beach, while Negroes are excluded therefrom; this

racially exclusionary policy is encouraged, supported and

enforced by state and local governments, notwithstanding

their contractual obligation to the United States to assure

nondiscriminatory public use of the beach; for attempting

to enjoy the beach equally with whites, petitioners, Negroes

and white civil rights workers, were convicted of trespass.

Under these circumstances, do petitioners’ convictions of

fend the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States?

3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

This case also involves the following two statutes of the

United States:

1) Act of August 13, 1946, Public Law 727, 79th Cong.,

2nd Sess., 60 Stat. 1056, Section I, codified with amend

ments as 33 U. S. C. A. §426e (1965 Supp.):

That with the purpose of preventing damage to public

property and promoting and encouraging the healthful

recreation of the people, it is hereby declared to be

the policy of the United States to assist in the construc

tion, but not the maintenance, of works for the im

provement and protection against erosion by waves

and currents of the shores of the United States that

are owned by States, municipalities, or other political

subdivisions: Provided, That the Federal contribution

toward the construction of protective works shall not

in any ease exceed one-third of the total cost: Pro

vided further, That where a political subdivision has

heretofore erected a seawall to prevent erosion, by

waves and currents, to a public highway considered by

the Chief of Engineers sufficiently important to justify

protection, Federal contribution toward the repairs of

such wall and the protection thereof by the building

of an artificial beach is authorized at not to exceed

one-third of the original cost of such wall, and that

investigations and studies hereinafter provided for are

hereby authorized for such localities: Provided fur

ther, That the plan of protection shall have been spe-

4

eifically adopted and authorized by Congress after

investigation and study by the Beach Erosion Board

under the provisions of section 2 of the River and

Harbor Act approved July 3, 1930, as amended and

supplemented.

2) Act of June 30, 1948, Public Law 858, 80th Cong., 2nd

Sess., 62 Stat. 1172, Section 101:

Sec. 101. The following works of improvement of

rivers and harbors and other waterways for naviga

tion, flood control, and other purposes are hereby

adopted and authorized to be prosecuted under the

direction of the Secretary of the Army and supervision

of the Chief of Engineers, in accordance with the plans

and subject to the conditions recommended by the Chief

of Engineers in the respective reports hereinafter

designated:

Harrison County, Mississippi; Shore Protection;

House Document Numbered 682, Eightieth Con

gress; . . .

This case also involves the following three statutes of the

State of Mississippi:

1) Miss. Code Ann., 1942, Rec., §8516.3, Section 2:

2. The board of supervisors be and the same is hereby

given full power and authority to meet and do and

grant any request of the United States Beach Erosion

Board of the United States Army Engineers by and

under public law 727, 79th congress, chapter 960, 2nd

session, and to assure either or both the following:

(a) Assure maintenance of the sea wall and drainage

facilities, and of the beach by artificial replenishment,

5

during the useful life of these works, as may be re

quired to serve their intended purpose ;

(b) Provide, at the county’s own expense, all neces

sary land, easements and rights-of-way;

(c) To hold and save the United States free from all

claims for damages that may arise either before, dur

ing or after prosecution of the work;

(d) To prevent, by ordinance, any water pollution

that would endanger the health of the bathers;

(e) To assume perpetual ownership of any beach

construction and its administration for public use only,

and that the board of supervisors is given full power

and authority to do any and all things necessary in and

about the repair and reconstruction, or construction or

maintenance of the sea wall and sloping beach adjacent

thereto, and they are given such power to cooperate

with the requirements of the United States govern

ment to receive any grant or grants of money from

congress or to contribute any grant or grants to the

United States Army Engineers in and about this con

struction and maintenance, and they are further given

full power and authority to employ engineers, lawyers,

or any other professional or technical help in and about

the completion of this project. In the event the county

engineer is selected to do any or all of said work, the

board of supervisors is hereby authorized to pay and

allow him such reasonable fees or salary which, in their

opinion, is necessary, just and commensurate to the

work done by him.

They are further given full power and authority to

let, by competitive bids, any contract for the repair

6

of said wall, or for the installation and drainage, and

for the construction of any additional section of wall,

together with any artificial beach adjacent to said

wall, or they may, in their discretion, negotiate a con

tract for any and all construction or any part thereof

for the construction, repair, reconstruction or addi

tions thereto, or they may do any or all of said work

under the direction of the county engineer or engineers

employed by them and for which purpose they may

employ all necessary labor, equipment and purchase

necessary materials.

The intent and purpose of this act is to give unto

the respective boards of supervisors the full power

and authority to carry out all the provisions herein,

and to act independently, jointly or severally with the

United States government by and under public law

727, 79th congress (Laws, 1948, ch. 334, §2).

2) Miss. Code Ann., 1942, Rec., §2409.7 (1964 Supp.):

§2409.7. Trespass—going into or upon, or remaining

in or upon, buildings, premises or lands of

another after being forbidden to do so.

1. If any person or persons shall without authority

of law go into or upon or remain in or upon any

building, premises or land of another, whether an

individual, a corporation, partnership, or association,

or any part, portion or area thereof, after having

been forbidden to do so, either orally or in writing

including any sign hereinafter mentioned, by any

owner, or lessee, or custodian, or other authorized

person, or after having been forbidden to do so by such

sign or signs posted on, or in such building, premises or

7

land, or part, or portion, or area thereof, at a place

or places where such sign or signs may be reasonably

seen, such person or persons shall be guilty of a mis

demeanor, and upon conviction thereof shall be pun

ished by a fine of not more than five hundred dollars

($500.00) or by confinement in the county jail not

exceeding six (6) months, or by both such fine and

imprisonment.

2. The provisions of this act are supplementary to

the provisions of any other statute of this state.

3. If any paragraph, sentence or clause of this act

shall be held to be unconstitutional or invalid, the same

shall not affect any other part, portion or provision

of this act, but such other part shall remain in full

force and effect (Laws, 1960, ch. 246, §§1-3).

3) Miss. Code Ann., 1942, Rec., §4065.3:

§4065.3. Compliance with the principles of segrega

tion of the races.

1. That the entire executive branch of the govern

ment of the State of Mississippi, and of its subdivi

sions, and all persons responsible thereto, including

the governor, the lieutenant governor, the heads of

state departments, sheriffs, boards of supervisors,

constables, mayors, boards of aldermen and other gov

erning officials of municipalities by whatever name

known, chiefs of police, policemen, highway patrol

men, all boards of county superintendents of educa

tion, and all other persons falling within the executive

branch of said state and local government in the State

of Mississippi, whether specifically named herein or

8

not, as opposed and distinguished from members of

the legislature and judicial branches of the government

of said state, be and they and each of them, in their

official capacity are hereby required, and they and each

of them shall give full force and effect in the per

formance of their official and political duties, to the

Resolution of Interposition, Senate Concurrent Reso

lution No. 125, adopted by the Legislature of the State

of Mississippi on the 29th day of February, 1956,

which Resolution of Interposition was adopted by

virtue of and under authority of the reserved rights

of the State of Mississippi, as guaranteed by the Tenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States;

and all of said members of the executive branch be and

they are hereby directed to comply fully with the Con

stitution of the State of Mississippi, the Statutes of

the State of Mississippi, and said Resolution of Inter

position, and are further directed and required to pro

hibit, by any lawful, peaceful and constitutional means,

the implementation of or the compliance with the In

tegration Decisions of the United States Supreme

Court of May 17, 1954 (347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98

L. ed. 873) and of May 31, 1955 (349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct.

753, 99 L. ed. 1083), and to prohibit by any lawful,

peaceful, and constitutional means, the causing of a

mixing or integration of the white and Negro races

in public schools, public parks, public waiting rooms,

public places of amusement, recreation or assembly

in this state, by any branch of the federal govern

ment, any person employed by the federal government,

any commission, board or agency of the federal gov

ernment, or any subdivision of the federal government,

and to prohibit, by any lawful, peaceful and constitu

9

tional means, the implementation of any orders, rules

or regulations of any board, commission or agency of

the federal government, based on the supposed au

thority of said Integration Decisions, to cause a mix

ing or integration of the white and Negro races in

public schools, public parks, public waiting rooms,

public places of amusement, recreation or assembly

in this state.

2. The prohibitions and mandates of this act are

directed to the aforesaid executive branch of the gov

ernment of the State of Mississippi, all aforesaid sub

divisions, boards, and all individuals thereof in their

official capacity only. Compliance with said prohibi

tions and mandates of this act by all of aforesaid

executive officials shall be and is a full and complete

defense to any suit whatsoever in law or equity, or

of a civil or criminal nature which may hereafter be

brought against the aforesaid executive officers, offi

cials, agents or employees of the executive branch of

State Government of Mississippi by any person, real

or corporate, the State of Mississippi or any other

state or by the federal government of the United

States, any commission, agency, subdivision or em

ployee thereof (Laws, 1956, ch. 254, 2).

10

Statement

This case presents the issue whether Negroes may be

punished by the State of Mississippi for attempting to

enjoy equally with whites one of the largest man-made

beaches in the world, a gleaming strip of sand, 24 miles

in length, along the coast of the State of Mississippi—con

structed and maintained with federal, state and local funds,

pursuant to federal, state and local programs and policies.1

The state and local governments derive substantial bene

fits from the beach, for it serves as a nation-wide attraction

for numerous tourists arriving on the major interstate

highway which runs parallel to it and separates it from the

homes of the residents.2

1 The evidence of governmental involvement in the beach was

not before the jury that convicted petitioners of trespass, because

the trial judge excluded it (R. 586, 593). The proffered evidence

included a resolution by the Board of Supervisors of Harrison

County declaring its intention to borrow one million five hundred

thousand dollars for the construction of the beach (Exhibit 1, R.

585-91) and the contract between the United States and the Board

of Supervisors of Harrison County, pursuant to which the federal

government donated $1,133,000 (R, 595) for construction of the

beach and Harrison County pledged to “ fajssure perpetual public

use of the beach and its administration for public use only” (E. 608)

(Exhibit 2, R. 594-611).

The extent of governmental involvement in the beach is discussed

in detail under “Reason for Granting the Writ.”

2 The report of the Chief of Engineers to the Department of the

Army, set forth in the Appendix, pp. 2a-4a, infra, pursuant to which

the federal money was allocated, stated (3a-4a) :

As indicated, the project would protect U. S. Highway 90, a

major public thoroughfare, and the 24 mile beach, generally

300 feet wide above mean sea level, and would afford a large-

scale facility for the healthful recreation of the public at large.

In my opinion, the direct and indirect benefits justify the

indicated Federal contribution (House Document 682, 80th

Cong. 2nd Sess., p. 4).

11

As a tourist attraction, the beach has always been rou

tinely used by the white public (R. 336-37, 387-88, 480-81,

518-19, 537, 702); Negroes have traditionally been rigor

ously excluded (R. 285-86, 398).3

The State of Mississippi has maintained, and continues

to maintain, that Negroes may be excluded from the

beach—notwithstanding massive governmental involve

ment in the beach through monies, programs and policies,

and notwithstanding the fact that there would be no beach

absent this involvement—because the State has never con

demned the land and the Supreme Court of Mississippi has

declared title to the beach in fee simple in the abutting

private landowners. Harrison County v. Guice, 244 Miss.

95, 140 So. 2d 838 (1962).

The United States has brought suit in the United States

District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi,

seeking to enforce the obligation assumed by Harrison

County (see note 1, supra) to take title to the beach and to

“ [ajssure perpetual public use of the beach and its ad

ministration for public use only” (R. 608) (contract be

tween the United States and Harrison County, entered into

January 23, 1951, Exhibit 2, R. 594-611). United States v.

Harrison County, S. D. Miss., No. 2262. Although the case,

filed in I960,4 has been fully tried, it has not yet been

decided by the District Court.

3 The trial judge attempted to prevent counsel for appellants

from proving that petitioners’ arrests were racially motivated (“ The

integration issue is not involved in this lawsuit,” R. 418-20, 516-17).

Nonetheless, the record as a whole leaves no room for doubt, see

citations in text, passim.

4 Suit was filed following an earlier incident involving expulsion

of Negroes from the beach.

12

Prior to June, 1963, when this ease arose, Negroes un

successfully5 tried to use the beach, and in June, 1963, after

3 years of fruitless litigation, they tried again (R. 336, 386,

408, 623-24). For several weeks, officials of the City of

Biloxi and Harrison County attempted to dissuade them.

Meetings were held between these officials and the leader

of the protesters, petitioner Mason; local newspapers and

radio kept whites informed about the “ invasion” ; and

police were placed on the alert (R. 297, 302, 305-08, 379-86,

389-92, 414-17, 473, 485-87, 624-31, 704A).

Finally, on Sunday, June 23, 1963, in the early after

noon, the 29 petitioners herein,6 three of whom are white

(R. 515), set foot upon a portion of West Beach in Biloxi

(R. 506-07).

An angry crowd of approximately 2,000 whites gathered

along the highway (R. 464, 574, 618); approximately 50

police officers arrived on the scene (R. 614) ;7 an agent of

the putative titleholder of the beach property appeared

5 Some Negroes were arrested and others were beaten by whites

(R. 704B).

6 The petitioners are: Gilbert R. Mason, William Adams, Jr.,

John M. Aregood, Charley Avery, Margaret Beines, James L. Black,

Harold Boglin, Myrtle Bridges, Eugene Cannon, Harry E. Cannon,

Mattie Cannon, Charles Carvell, Charles R. Davis, Samuel Ed

wards, Rehofus Esters, Roger Gene Gallagher, Ernest A. Jackson,

E. E. Jackson, Cornelius D. Kemp, Robert C. Louis, Phyllis M.

Love, Frances A. Magee, Arlena Massey, Barbara Mosley, Gloria

S. Powell, Alvin Sehneckenberg, George Watters, Marshall White,

Estes Woulard.

7 Eight agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation were pres

ent (R. 498-99). The large contingent of law enforcement officers

was, however, unable to prevent petitioners’ cars from being burned

or overturned (R. 615-17) or to prevent the police van in which

petitioners were driven to jail from being tilted by the mob, caus

ing minor injuries to some of the petitioners (R. 633-34, 652). No

arrests were made (R. 610-11).

13

(R. 447)8 and ordered petitioners to vacate the property

(R. 448, 468),9 which they failed to do (R. 449); the

agent executed a charging affidavit (R. 450); and the police

arrested petitioners (R. 450). None of the white members

of the public enjoying the beach were arrested (R. 480,

524-26).

Petitioners were charged with trespass in violation of

Miss. Code Ann., 1942, Rec. §2409.7, set forth, pp. 6-7,

supra. The criminal affidavits, as amended, charged that

petitioners “ did wilfully and unlawfully, without authority

of law, remain upon land of another, to wit, Mrs. James

M. Parker, on West Beach in Biloxi, Mississippi, after

having been forbidden orally to do so by the duly author

ized agent of said property owner authorized to control

said property, in violation of Section 2409.7 of the Missis

sippi Code of 1942, annotated, made an ordinance of the

City of Biloxi and in violation of Ordinance 12-24, Code of

Ordinances of the City of Biloxi” (R. 2-146).

June 28, 1963, petitioners were tried in the Police Justice

Court in the City of Biloxi, found guilty and sentenced to

30 days imprisonment and $100.00 fine (R. 6-146).10

8 The City proved private title to the beach property entered

upon by petitioners, conformably to Harrison County v. Guice,

supra (R. 426E-426H, 452).

9 Petitioner Gallagher testified he did not hear this warning

above the din of the hostile crowd (R. 510-14, 517, 577). Petitioner

Mason testified that he heard the warning but was given insufficient

time to leave the beach (R. 619, 621-22, 697-99). These petitioners

further testified that they did not intend to remain on premises

which they were ordered to vacate (R. 521, 680) and that they had

in fact left another part of the beach earlier that day when ordered

to do so (R. 527, 613).

10 Some of the sentences of imprisonment were suspended and

some of the fines were suspended as to $50.00 thereof.

The cases of an approximately equal number of juveniles who

accompanied the adult petitioners were disposed of in juvenile

court proceedings.

14

On November 20-22, 1963, petitioners were tried de novo

in the County Court of Harrison County, again convicted

and sentenced to 30 days imprisonment (suspended upon

good behavior) and $100.00 fine (R. 187-190).

Petitioners appealed to the Circuit Court of Harrison

County which, on February 22, 1965, affirmed their convic

tions and upheld their fines, but set aside their sentences

of imprisonment (R. 718).

Petitioners thereupon appealed to the Supreme Court of

Mississippi, which on March 21, 1966, affirmed without

opinion (184 So. 2d 113) (R. 734). A suggestion of error

was timely filed and overruled by the Court on April 11,

1966 (R. 735).

How the Federal Questions Were

Raised and Decided Below

In the County Court of Harrison County, petitioners

moved for a directed verdict on the grounds that their

convictions would deprive them of rights under the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States and

would, in particular, deprive them “ of the use of the public

beaches of the City of Biloxi, supported by public funds

of the City of Biloxi and by federal grant, all in violation

of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment . . . ” (R. 163). Petitioners’ motion was overruled by

the trial judge (R. 504).

Petitioners’ attempt to raise the issue of the public

nature of the beach was frustrated by the trial judge’s ex

clusion of evidence showing massive governmental involve

ment in the beach (see note 1, supra) and by the trial

15

judge’s refusal to give petitioners’ proposed instructions

to the jury concerning this governmental involvement

(R. 180-185).

After trial, petitioners filed a motion for a new trial, as

signing roughly the same grounds as in the motion for a

directed verdict (R. 191-92). This motion was also over

ruled by the trial judge (R. 193).

In the Circuit Court of Harrison County and again in

the Supreme Court of Mississippi petitioners preserved

their claims under the Fourteenth Amendment (R. 728-32).

Reason for Granting the Writ

The Decision Below Approves Enforcement of a State-

Supported Policy of Racial Discrimination in Facilities

Which Are Significantly Impressed With Federal, State

and Local Financial Contributions, Programs and Poli

cies and Conflicts With Decisions of This Court.

Petitioners’ convictions for trespassing upon a portion

of West Beach in Biloxi offend the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment because the beach is sig

nificantly involved with the federal11 and state governments

and the racially exclusionary policy enforced thereon is

significantly tied to the State of Mississippi.

It is no answer to say that private choice is involved in

the racially exclusionary policy and that title to the prop

11 As a technical matter, the Due Process Clause of the Fifth

Amendment has also been violated, since petitioners’ right to equal

enjoyment of facilities in which the federal government is sig

nificantly involved has been abridged. See, e.g., Simkins v. Moses

H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323 F. 2d 959 (4th Cir. 1963), cert,

denied, 376 U. S. 938 (1964).

16

erty apparently resides in private hands. Private conduct

abridging individual rights may offend the Equal Protec

tion Clause if “ to some significant extent the State in any

of its manifestations has been found to have become in

volved in it” (Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority,

365 U. S. 715, 722 (1961) ).

Numerous decisions have recognized that a privately-

owned facility may be public for purposes of the Four

teenth Amendment. Marsh v. Alabama, 326 II. S. 501

(1946); Simkins v. Moses 11. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323

F. 2d 929 (4th Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 376 U. S. 938 (1964);

Eaton v. Grubbs, 329 F. 2d 710 (4th Cir. 1964); Smith v.

Holiday Inns of America, Inc., 336 F. 2d 630 (6tli Cir.

1964). “ [B ]y sifting facts and weighing circumstances” ,

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. at 722,

it may be concluded “ that the public character of [a] park

requires that it be treated as a public institution subject

to the command of the Fourteenth Amendment, regardless

of who . . . has title under state law” (Evans v. Newton,

382 U. S. 296, 302 (1966)).

The beach involved in this case has become so entwined

with governmental programs and policies and taken on

such a governmental character as to preclude basing

criminal convictions on failure to obey purely racial limita

tions on its use.

Federal involvement in the beach has been sustained and

massive. Public Law 727, set forth, supra, pp. 3-4, enacted

by Congress in 1946, set forth the basic federal interest in

beach construction and restoration as that of “ preventing

damage to public property and promoting and encouraging

the healthful recreation of the people.” Pursuant to Public

Law 727, studies of various beaches were made by the

17

Beach. Erosion Board and, pursuant to these studies, Con

gress, on June 30, 1948, enacted Public Law 858, set forth,

supra, p. 4, authorizing the construction of the Harri

son County Beach involved in this case. This legislation

expressly incorporated by reference the report of the Chief

of Engineers, United States Army, in House Document

No. 682, 80th Cong., 2nd Sess., set forth, Appendix, pp. 2a-

4a, infra, prescribing the conditions under which the beach

work was to be prosecuted. The two conditions of critical

importance here were that “ the State of Mississippi or

local governmental agency . . . provide all necessary lands,

easements, and rights-of-way for accomplishment of the

work . . . and . . . give satisfactory assurances that they

will . . . [a]ssure perpetual public ownership of the beach

and its administration for public use only” (House Docu

ment No. 682, p. 4) (4a).

Pursuant to this legislation, on January 23, 1951, the

United States and Harrison County entered into an agree

ment for the prosecution of the shore protection work.

Conformably to the conditions in the enabling legislation,

Harrison County pledged to “ [p]rovi.de at its own expense

all necessary lands, easements and rights-of-way” (R. 597)

and to “ [a]ssure perpetual public use of the beach and its

administration for public use only” (R. 608).12

The federal government paid $1,133,000 for the repair

of the seawall and the construction of the Harrison County

Beach.13

12 Six years ago suit was brought by the United States to specifi

cally enforce these provisions. See text at note 4, supra.

The contract regulated in detail the prosecution of the work, in

cluding, e.g., insurance (R. 598), inspection (R. 598), labor (R.

601) and materials (R. 607).

13 This evidence of federal participation was not before the jury

which convicted petitioners, because the trial judge excluded all

attempts to show the public nature of the beach (R. 586, 593).

18

State and local governments have also been deeply in

volved in the beach. On March 31, 1948, the Mississippi

Legislature enacted Chapter 334, now codified as Miss.

Code Ann., 1942, Ree. §8516.3, §2 of which is set forth,

supra, pp. 4-6, enabling the Board of Supervisors of

Harrison County to meet the federal conditions, i.e., to

“ [p]rovide, at the county’s own expense, all necessary land,

easements and rights-of-way” and “ [t]o assume perpetual

ownership of any beach construction and its administration

for public use only.” In §1 of Chapter 334, the Mississippi

Legislature authorized Harrison County to borrow funds

for the beach work in an amount up to $1,500,000. Pur

suant to this enabling legislation, in October, 1948, the

Board of Supervisors of Harrison County declared its in

tention to issue bonds in the amount of $1,500,000 (R. 587-

91). Subsequently this money was raised and the work

prosecuted to completion.14

Today, conformably to its contractual obligation with

the federal government (R, 609), Harrison County main

tains the beach in a condition worthy of a national tourist

attraction (R. 623).

14 As with the evidence of federal involvement, this evidence of

state involvement was not before the jury which convicted peti

tioners (R. 586). However, the fact that this work was in fact

completed is documented in the preamble to Chapter 214 of Missis

sippi Laws 1952, codified as Miss. Code Ann., 1942, Rec. §8516.4,

authorizing Harrison County to raise additional funds “ to finish

the improvements and work regarding seawall, hydraulic fill, drain

age and road beds over the entire length of the county,” and recit

ing that Harrison County had completed “extensive repair to its

seawall and extensive work in extending and installing an adequate

drainage system behind said seawall, and extensive dredging and

placing hydraulic fill in front of said seawall in order that same

might be adequately protected.”

19

In addition to receiving public subvention, the beach

also serves a public function. Equally applicable to it is

the conclusion reached by this Court as to the park in

Evans v. Newton, 382 U. S. at 301: “ The service rendered

. . . is municipal in nature. It is open to every white per

son, there being no selective element other than race.”

Numerous decisions of this Court have recognized that

“ [m]ass recreation through the use of parks is plainly in

the public domain” (Evans v. Newton, 382 U. S. at 302).

City of New Orleans v. Barthe, 376 U. S. 189 (1964);

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 (1963); Wright v.

Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963); New Orleans Park Asso

ciation v. Detiege, 358 U. S. 54 (1958); Mayor and City

Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 877 (1955);

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 (1955).

Furthermore, consistent with Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U. S. 1 (1948); and Barrows v. Jackson, 346 TI. S. 249

(1953), “ state courts that aid private parties to perform

[a] public function on a segregated basis implicate the

State in conduct proscribed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment” (Evans v. Newton, 382 U. S. at 302). “ [T ]o the

extent that the State undertakes an obligation to enforce

a private policy of racial segregation, the State is charged

with racial discrimination and violates the Fourteenth

Amendment” (Griffin v. Maryland, 378 U. S. 130, 136

(1964)).

But the elements of state action in this case do not stop

here. The state and local governments are involved in

protecting the beach from Negroes as well as in protecting

it from tides and litter. Although it is a matter of national

notice that the State of Mississippi and Harrison County

entice a brisk tourist traffic to the beach, it is also a mat

20

ter of public record that they consider the beach off-limits

to Negroes and discourage as emphatically as they know

how its use by Negroes. This policy of the State of Mis

sissippi is reflected in Miss. Code Ann., Ree. 1942, §4065.3,

set forth, supra, pp. 7-9, which requires county and city

officials “ to prohibit by any lawful, peaceful and constitu

tional means, the causing of a mixing or integration of

the white and Negro races in . . . public places of amuse

ment, recreation or assembly in this state.” This legisla

tive exhortation has been well heeded by local officials,

including the Mayor, District Attorney and Chief of Police,

who have used all the powers of persuasion at their com

mand (R. 641-42, 644-47, 656-59, 692-93) and, when persua

sion failed, the arrest and prosecution of petitioners, to

discourage Negroes from using the beach. Their purpose

in this matter has been largely accomplished, for the

arrests and prosecutions of petitioners have largely served

to deter further attempts in the past three years to chal

lenge the racially exclusionary policy.

Thus, §4065.3 “ depart[s] from a policy of strict neu

trality in matters of private discrimination by enlisting

the State’s assistance only in aid of racial discrimination

and . . . involve [s] the State in the private choice as to

convert the infected private discrimination into state ac

tion, subject to the Fourteenth Amendment. Cf. Robinson

v. Florida, 378 U. S. 153; Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S.

267; Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244” (Evans

v. Newton, 382 U. S. 296, 306 (1966) (White, J. concur

ring)).

Harrison County and the City of Biloxi may hardly main

tain that they have acted in a neutral fashion in enforcing

the exclusion of Negroes from the beach. Obligated by

21

contract with the United States to assure nondiscrimina-

tory public use of the beach and commanded by the State

of Mississippi to enforce racial discrimination wherever

possible, they have - disregarded the paramount federal

obligation and heeded instead the state legislative com

mand. By subordinating the national interest in nondis

crimination to the state interest in discrimination, they

have struck a balance inconsistent with the Constitution

of the United States.

A final word should be said about the record made below.

Because the trial judge excluded much evidence tending

to show the public nature of the beach (see notes 12 and

13, supra), reversal for a new trial would plainly be re

quired under Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442, 448-49 (1900);

and Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U. S. 129 (1964) if the

record of governmental involvement were thought to be in

sufficient.15 However, because the refused exhibits are be

fore the Court and because much of the federal and state

involvement is a matter of public record, petitioners sub

mit that outright reversal is warranted.

15 The trial judge also prevented counsel for petitioners from

making certain offers of proof (R. 535-36 ; 637-38).

22

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the petition for writ of

certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

R. Jess B rown

125% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

Attorneys for Petitioners

A P P E N D I X

la

Judgment o f Supreme Court of Mississippi

Monday, March 21, 1966, Court Sitting

No. 43,705

Gilbert Mason, et al.

vs.

City of B iloxi.

This cause having been submitted at a former day of

this Term on the Record herein from the Circuit Court

Harrison County and this Court having sufficiently ex

amined and considered the same and being of the opinion

that there is no error therein doth order and adjudge that

the judgment of said Circuit Court rendered in this cause

on the 22nd day of February 1965 be and the same is

hereby affirmed. It is further ordered and adjudged that

the City of Biloxi do have and recover of and from the

appellants and Rev. Robert Nance and J. 0. Tate D.D.S.,

sureties on the appeal bond herein, all of the costs of this

appeal to be taxed, for which let proper process issue.

Minute Book “BN” Page 528

2a

REPORT OF THE CHIEF OF ENGINEERS,

UNITED STATES ARMY

Department op the A rmy,

Ofpice op the Chief of E ngineers,

Washington, March 8, 1948.

Subject: Beach erosion control study of Harrison County,

Miss.

To: The Secretary of the Army.

1. I submit for transmission to Congress a report with

accompanying papers on a beach erosion control study of

Harrison County, Miss., made by the Corps of Engineers

in cooperation with the Board of Supervisors of Harrison

County under the provisions of Section 2 of the River and

Harbor Act approved July 3, 1930, as amended and sup

plemented.

2. After full consideration of the reports secured from

the district and division engineers, the Beach Erosion

Board recommends that a project be adopted by the United

States authorizing Federal participation in the amount of

$1,133,000 toward the repair of the Harrison County sea

wall and its protection by the construction of a beach from

Biloxi Lighthouse to Henderson Point near Pass Christian,

Miss., with attendant drainage facilities, subject to certain

conditions.

3. The proposed 24-mile beach between Biloxi and Pass

Christian (Henderson Point) would protect the existing

sea wall built at a reported first cost of $3,400,000 during

House Document No. 682 , 80th Cong., 2nd Sess.

3a

1925-28 by Harrison County. After the wall was con

structed natural forces including hurricanes eroded the

original protective beach and severely damaged the struc

ture which is now subject to direct wave action including

undermining at normal stages of tide. The wall, extending

essentially throughout this 24-mile section, and the fore

shore are publicly owned. That wall protects IT. S. High

way 90, located generally about 100 feet landward of the

wall. This road is the principal highway along the Gulf

coast between Florida and Louisiana and the most heavily

traveled road in Mississippi. In view thereof it is my

opinion that the importance of this highway warrants ap

plication of Federal aid pursuant to the policy enunciated

in Public Law 727, Seventy-ninth Congress, approved Au

gust 13,1946, section I of which provides:

# # * # *

4. Under the Federal-aid project proposed by the Beach

Erosion Board the United States would finance the pro

posed beach improvement at an estimated cost of $856,000

and participate in the financing of needed repairs to the

sea wall at an estimated cost of $277,000, a limiting total

of $1,133,000 which is one-third of the original construc

tion cost of the sea wall. Local interests would, among

other things, effect remaining necessary sea-wall repairs,

alter the drainage system, maintain the new beach and

attendant facilities, remedy water pollution that would

endanger the public health, and administer the beach for

public use only. The cost to local interests includes an

estimated $1,182,000 for drainage system alterations and

an undetermined amount for sea-wall repairs. As indi

cated, the project would protect U. S. Highway 90, a major

public thoroughfare, and the 24-mile beach, generally 300

feet wide above mean sea level, and would afford a large-

House Document No. 682, 80th Cong., 2nd Sess.

4a

scale facility for the healthful recreation of the public at

large. In my opinion the direct and indirect benefits jus

tify the indicated Federal contribution.

5. Accordingly, after due consideration of these re

ports, I concur generally in the views and recommenda

tions of the Board. I recommend adoption of a project

by the United States authorizing Federal participation of

$1,133,000 toward the repair of the Harrison County sea

wall and its protection by the construction of a beach from

Biloxi Lighthouse to Henderson Point near Pass Christian,

Miss., in substantial accordance with the plans outlined

by the Beach Erosion Board, provided the State of Mis

sissippi or local governmental agency: (1) adopt the afore

mentioned plan of improvement including repairs and

alterations; (2) submit for approval by the Chief of Engi

neers detailed plans and specifications and arrangements

for prosecuting the entire improvement prior to the com

mencement of such work; (3) provide all necessary lands,

easements, and rights-of-way for accomplishment of the

work; and provided further that responsible State or

local interests give satisfactory assurances that they will:

(a) maintain the sea wall and drainage facilities, and the

beach by artificial replenishment, during the useful life

of these works as may be required to serve their intended

purpose; (b) hold and save the United States free from

all claims for damages that may arise either before, dur

ing, or after prosecution of work; (e) remedy water pollu

tion that would endanger public health; and (d) assure

perpetual public ownership of the beach and its adminis

tration for public use only.

R. A. W heeler,

Lieutenant General,

Chief of Engineers.

House Document No. 682, 80th Cong., 2nd Sess.

38