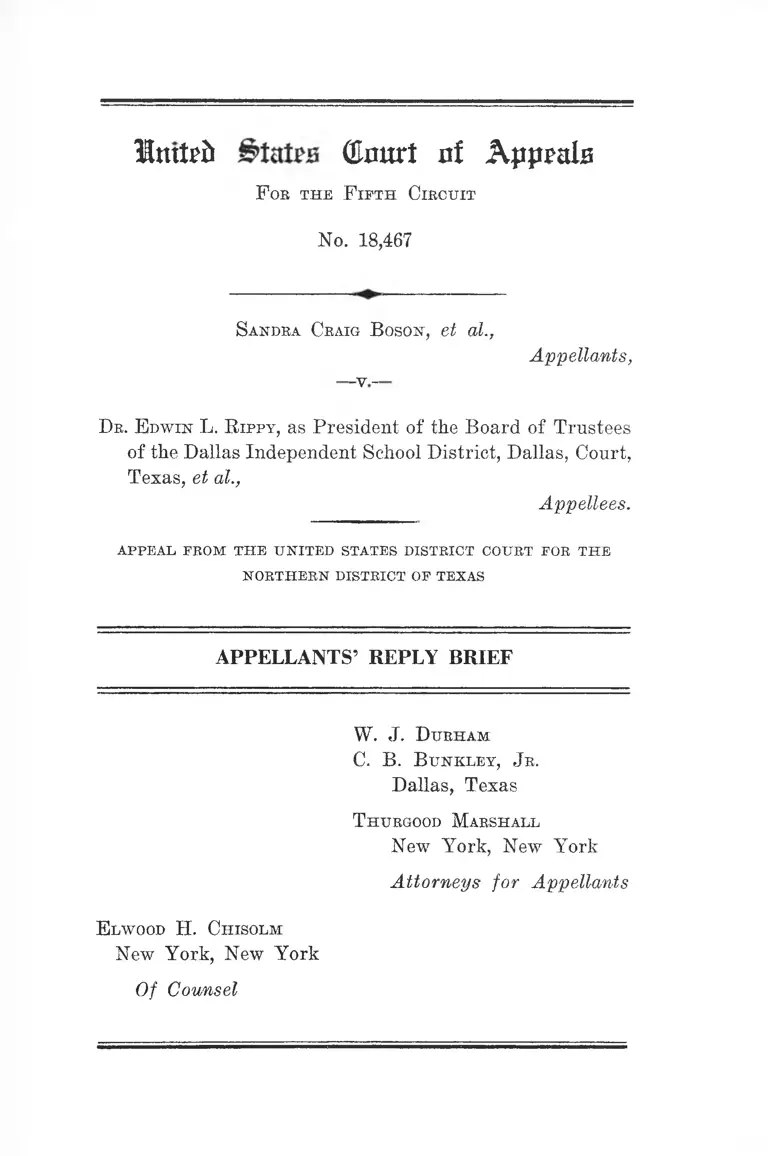

Boson v. Rippy Appellants' Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Boson v. Rippy Appellants' Reply Brief, 1961. 514cc928-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a0954781-bf40-4555-89df-85a8dc91da3f/boson-v-rippy-appellants-reply-brief. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Ittttefc tourt of &ppmla

F ob the F ifth Circuit

No. 18,467

Sandra Ceaig B oson, et al.,

-v-

Appellants,

Dr. E dwin L. R ippy, as President of the Board of Trustees

of the Dallas Independent School District, Dallas, Court,

Texas, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

NORTHERN DISTRICT OP TEXAS

APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF

W. J. Durham

C. B. B unkley, J r.

Dallas, Texas

T hurgood Marshall

New York, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

E lwood H. Chisolm

New York, New York

Of Counsel

MnxUb (Sflurt of Appeals

F oe the F ifth Circuit

No. 18,467

Sandra Craig Boson, et al.,

Appellants,

Dr. E dwin L. R ippy, as President of the Board of Trustees

of the Dallas Independent School District, Dallas, Court,

Texas, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF

The brief of the Board of Trustees of the Dallas Inde

pendent School District urges on the one hand that the

District Court did not err in ordering desegregation to

proceed under the so-called salt-and-pepper plan and on the

other hand that it erred in disapproving their twelve year

stair-step desegregation plan. In this brief, they also argue

that both plans fully comply with the constitutional re

quirements laid down in the School Segregation Cases—

although the stair-step plan is best under the circum

stances existing here—yet neither plan comports with state

law inasmuch as the District Court erroneously struck

from both a provision conditioning implementation upon

compliance with Article 2900a of the Texas Statutes. These

contentions, plaintiffs submit, are logically unsound and

legally wrong.

2

I.

True, in Broivn v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, at

300, the Supreme Court contemplated that “the personal

interest of the plaintiffs in admission to public schools as

soon as possible on a nondiscriminatory basis” might be

postponed “to take into account the public interest in the

elimination of [certain administrative] obstacles in an ef

fective and systematic manner.” Likewise, in Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, at 7, the Court conceded that “a Dis

trict Court, after analysis of the relevant factors (which,

of course, excludes hostility to racial discrimination), might

conclude that justification existed for not requiring the

present nonsegregated admission of all qualified Negro

children.” However, in view of the intent and substance

of the Court’s first Brown decision, 347 U.S. 483, allowance

of such latitude in fashioning desegregation decrees cer

tainly does not sanction a system of racially separate

schools in accordance with the District Court’s salt-and-

pepper plan (see Appellants’ Brief, pp. 7-10). Nor does

it authorize approval of a stair-step plan which would

wholly and irremediably deprive plaintiffs and many other

Negro children of an education in nonsegregated schools.

By its very nature, the twelve year stair-step plan pro

posed by defendants and disapproved by the District Court

would do just that. None of the plaintiffs, all of whom were

attending public schools when this suit was initiated in 1955

—and, indeed, no other Negro children who entered public

school prior to the commencement of such a plan and there

after made normal progress from grade to grade—could

ever enjoy a day of desegregated schooling in Dallas. For

these children plaintiffs in particular, the only “relief” pos

sible under such a plan is the vicarious satisfaction which

may be gained from having been directly or indirectly in-

3

volved in litigation which produced a small step toward

full compliance with the constitutional mandate. This is

no legal substitute for judicial protection of their “per

sonal and present” constitutional rights. This, plaintiffs

submit, makes a mockery of equal justice under the law.

Defendants point to, and plaintiffs are aware of, Kelley

v. Board of Education, 270 F.2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959), cert,

denied 361 U.S. 924, which upheld a somewhat similar stair

step plan as being a permissible implementation of the

constitutional principles proclaimed in School Segregation

Cases. But other federal courts recently have taken a longer

look at the twelve year stair-step plan and they reached a

contrary conclusion. See Evans v. Ennis, 281 F.2d 385 (3rd

Cir. 1960); Blackwell v. Fairfax County School Board,

Civ. No. 1967, E.D. Va., September 22, 1960 (plan rejected).

Cf. Maxwell v. County Board of Education of Davidson

County, Civ. No. 2956, M.D. Tenn., October 27, 1960 (plan

modified to require desegregation of first four grades in

January 1961 and one grade a year thereafter).

In Evans v. Ennis, which disapproved a state-wade twelve

year stair-step plan “insofar as it postpones full intega-

tion” and ordered defendants to integrate the individual

infant plaintiffs commencing with the Fall Term 1960, to

submit a plan providing for the integration of all Negro

children who seek it in the school years followdng 1961, and

to continue during the interim the grade-by-grade integra

tion presently in effect, this plan was found legally imper

missible because “it will completely deprive the infant plain

tiffs, and all those in like position, of any chance whatever

of integrated education, their constitutional right.” 281

F.2d at 389, 390, 393.

Defendants also point to this Court’s comment on “good

faith” in Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F.2d

156, at 166, to the effect that this factor might warrant ap-

4

proval of “such reasonable steps in a process of desegrega

tion as appear helpful in avoiding unseemly confusion and

turmoil.” And they assert that the stair-step plan disap

proved by the District Court was arrived at “in all good

faith as the best process to follow in avoiding confusion,

turmoil and violence in reaching the target of complete

integration.” Plaintiffs respectfully submit that neither

good faith per se nor the possible effect ascribed to it in

Bush can be determinative of the validity of the plan.

First, the Supreme Court some two years after Bush

specifically enjoined any consideration of unseemly tur

moil, confusion and violence in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1.

Secondly, “good faith alone cannot solve their problem or

[y]our own. True the defendants must act in good faith to

comply with the mandate of the Supreme Court, but they

must do more than this. They must proceed to integration

with all deliberate speed. Certainly in the plan [of grade-

by-grade integration of the kind arrived at by defendants]

the accent is on deliberation rather than speed. The defen

dants must also make a reasonable start toward full com

pliance. In the cases at bar the step toward compliance

about to be compelled is but a small one. It follows that the

plan [dis] approved by the court below is not in accord with

the legal principles enunciated by the Supreme Court.”

Evans v. Ennis, supra, 281 F.2d at 394.

II.

Defendants elsewhere in their brief equate the present

admission of the infant plaintiffs, and others in like posi

tion, during the next or ensuing school term with “en masse

integration” and claim that this “is not in accord with the

spirit or intent of either the Supreme Court or the pre

vious opinions of this Court” (pp. 10, 11). Plaintiffs sub-

5

mit that even if this is tantamount to en masse integration,

but cf. “A Statistical Summary, State-by-State, of Segre

gation-Desegregation Activity Affecting Southern Schools

from 1954 to Present,” Southern Educational Reporting

Service (7th Printing: January 15, 1960); Evans v. Ennis,

supra, 281 F.2d 385, it is certainly in accord with the letter

and spirit of the holding in Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483. See Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S.

294, 298; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 5. See also Orleans

Parish v. Bush, supra, 242 F.2d at 164, fn. 7.

Of course, as plaintiffs have set out above, the Supreme

Court first in the second Brown decision and again in

Cooper v. Aaron recognized that in certain circumstances

the present admission of infant plaintiffs and others sim

ilarly situated might be deferred. But these opinions do

not establish the Court’s unqualified approval of any prin

ciple of gradual desegregation. Neither do they stand for

the proposition that gradual desegregation by some psy

chologically tempting plan rather than the admission of

infant plaintiffs and others at the nest school term is the

best or more desirable means of bringing about the end of

racial segregation in public schools. What they do say,

in sum, is that school authorities, who make a prompt and

reasonable start toward full compliance, may be allowed

additional time to effectuate full compliance if they carry

the burden of showing the existence of certain specifically

enumerated circumstances which necessarily militate

against the present nonsegregated admission of all quali

fied children and that such time is consistent with good faith

compliance at the earliest practicable date. Brown v. Board

of Education, supra, 349 U.S. at 300; Cooper v. Aaron,

supra, 358 U.S. at 7.

Plaintiffs submit that defendants have not carried the

burden. Indeed, the record brought up on this and prior

6

proceedings is barren of any legally cognizable grounds

for delaying the constitutional rights of infant plaintiffs

and others similarly situated beyond the five years this case

has been in litigation.

There is undeniably evidence which reveals the size of

the plant, staff, budget and pupil population as well as the

rate of growth of the Dallas school system (E. 2, 102-103,

107; see 247 F.2d 268, 271). But these factors, although

illuminating and probably pertinent, are nevertheless not

among those which the Supreme Court said courts could

predicate a conclusion that justification exists for not re

quiring the present non-segregated admission of infant

plaintiffs and all others in like position. See Brown v.

Board of Education, supra, 349 U.S. at 300; Cooper v.

Aaron, supra, 358 U.S. at 7.

There is also some evidence of overcrowded classrooms

and a difference in the scholastic aptitudes of white and

Negro children, as well as the effect of these conditions

upon teaching and teachers (see 247 F.2d 268, 271). How

ever, these facts are not only outside of those enumerated

in the Brown and Cooper decisions but this Court has re

jected their relevancy in this case. 247 F.2d 268, 271.

Finally, spread throughout the opinions of the District

Court and defendants’ brief as well as the record, itself,

is the factor of hostility toward desegregation—i.e., an

ticipated fears, apprehensions and emotional reactions of

parents, pupils and teachers to any plan of compliance more

expeditious than the two that are before this Court. Aside

from the fact that the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board

of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 300, made it plain that the con

stitutional rights of infant plaintiffs and others similarly

situated cannot be denied because of this, plaintiffs submit

that a paraphrase of the reasoning in Evans v. Ennis, 281

F.2d at 389, is apposite here:

7

“As we have indicated one of the main thrusts of

the opinion of the court below is that the emotional

impact of desegregation on a faster basis than that

ordered would prove disruptive not only to the D [alias]

School System but also to law and order in some of the

localities which would be affected by integregation. We

point out, however, that approximately 6 years have

passed since the first decision of the Supreme Court in

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, supra, and

that the American people and, we believe, the citizens

of D[alias], have become more accustomed to the con

cept of desegregated schools and to an integrated op

eration of their School System.* Concededly there is

still some way to go to complete an unqualified accept

ance but we cannot conclude that the citizens of

D[alias] will create incidents of the sort which oc

curred in the M[ansfield] area some five years ago.

We believe that the people of D [alias] will perform

the duties imposed on them by their own laws and their

own courts and will not prove fickle to our democratic

way of life and to our republican form of government.

In any event the Supreme Court has made it plain in

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 16 (1958), the so-called

‘Little Rock case’, that opposition is not a supportable

ground for delaying a plan of integration of a public

school system. In this ruling the Supreme Court has

acted unanimously and with great emphasis stating

tha t: ‘The constitutional rights of respondents [Negro

school children of Arkansas seeking integration] are

not to be sacrificed or yielded to . . . violence and dis

order . . . ’ . We are bound by that decision.”

* Indeed, evidence has been introduced by defendants to the effect that

a considerable number of white people would like to go to integrated schools

(E. 101).

8

III.

The closing contention made in defendants’ brief is that

the District Court erred in ordering the elimination of the

provision in both plans which conditioned implementation

upon the successful outcome of a referendum conducted in

conformity with Article 2900a of the Texas Statutes. Plain

tiffs answer that this simply is not so.

As has been pointed out on a prior appeal in this case,

“That Act, of course, cannot operate to relieve the members

of this Court of their sworn duty to support the Constitu

tion of the United States, the same duty which rests upon

the members of the several state legislatures and all execu

tive and judicial officers of the several states. We cannot

assume that that solemn duty will be breached by any of

ficer, state or federal.” 247 F.2d 268, 272. Clearly, the

order of the District Court conforms with this. So, too,

does the opinion of the Attorney General of Texas to the

effect that the Act is not applicable to integration ordered

by a federal court.

Defendants say, and plaintiffs do not deny, that an opin

ion of the State Attorney General lacks the binding effect

of a judicial determination. Nevertheless, it is usually fol

lowed in actual practice—as is the case in Houston with

regard to Article 2900a—and, where a question of law is

before the courts, an opinion of the highest non-judicial

officer of the State is entitled to careful consideration and

quite generally is regarded as highly persuasive. See, e.g.,

Jones v. Williams, 121 Tex. 94, 45 S.W. 2d 130 (1931);

Kerby v. Collin County, 212 S.W.2d 494 (Tex. Civ. App.

1948). Moreover, in federal courts, the construction placed

on a state statute in a written opinion of an attorney gen

eral is given great respect and should not be disregarded

9

in the absence of controlling judicial decisions. Union In

surance Co. v. Hodge, 21 How. (U.S.) 35, 66; Badger v.

Hoidale, 88 F.2d 208, 211 (8th Cir. 1937). Cf. Phyle v.

Duffy, 334 U.S. 431, 441,

Be this as it may, plaintiffs also submit that a referendum

by citizens in one community cannot supersede the mandate

of the Constitution of the United States. The Fourteenth

Amendment was adopted to shield the individual from ar

bitrary action by a state, and where such arbitrary action

occurs it cannot be sanctioned and rendered beyond the

reach of the Amendment by majority vote. As the Supreme

Court of Colorado stated in holding unconstitutional a pro

vision that its decisions could be reviewed by referendum,

People v. Western Union Telegraph Co., 70 Colo. 90, 97-99,

198 Pac. 146,149:

“If the people of the state be empowered, by the mere

re-enactment of a statute which violates the federal

Constitution, to give full force and effect to such un

constitutional legislation, then that portion of the state

Constitution which vests in them such power is itself

prohibited by the terms of the federal compact, and is

null and void and of no force or effect whatsoever.

“When a federal constitutional question is raised in

any of the trial courts of Colorado . . . it cannot be

reviewed by popular vote of the citizens of Colorado.”

Or, as was held in connection with a school desegregation

controversy in Kelly v. Board of Education of the City of

Nashville, 159 F. Supp. 272, 278 (M.D. Tenn. 1958), aff’d,

270 F.2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959), cert, denied 361 U.S. 924:

“To hold out to [the Negro children] the right to

attend schools with members of the white race if the

members of that race consent is plainly such a dilution

of the right itself as to rob it of meaning or substance.

10

The right of Negroes to attend the public schools with

out discrimination upon the ground of race cannot be

made to depend upon the consent of the members of the

majority race.”

CONCLUSION

W herefore, appellants pray that the judgment be re

versed and that the Court here render the judgment which

justice requires for infant plaintiffs, and others in like

position, without remaining for further trial in the court

below. '

Respectfully submitted,

W. J. Durham

C. B. Bunkley, J r.

Dallas, Texas

T hurgood Marshall

New York, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

E lwood H. Chisolm

New York, New York

Of Counsel

i