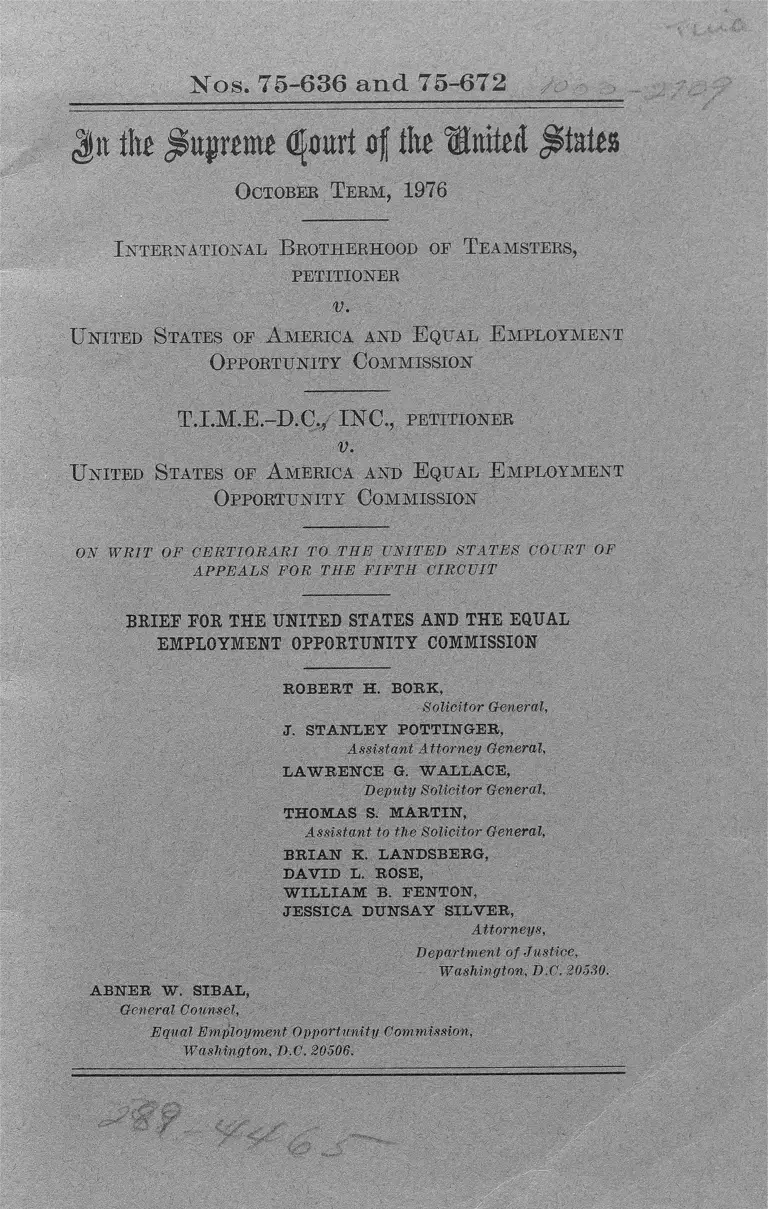

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States Brief for the United States and the EEOC

Public Court Documents

December 1, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States Brief for the United States and the EEOC, 1976. cbb400ce-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a09f4c3f-0dc5-4eb2-969b-538989c20b97/international-brotherhood-of-teamsters-v-united-states-brief-for-the-united-states-and-the-eeoc. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

N o s . 7 5 -6 3 6 a n d 7 5 -6 7 2

Jit tfe jSujnm* § m t af t h HttM $ M t z

O ctober T e r m , 1976

I n t e r n a t io n a l B roth erh oo d of T ea m ster s ,

pe t it io n e r

V .

U n it ed S tates of A m er ic a and E q ual E m pl o y m e n t

O p po r t u n it y C o m m issio n

T.I.M.E.-D.C., INC., p e t it io n e r

■v.

U n it e d S tates of A m er ic a and E q ua l E m pl o y m e n t

O ppo r t u n it y C o m m issio n

ON W R IT OF C E R T IO R A R I TO TH E U NITED S T A T E S COURT OF

A P P E A L S FOR TH E F IF T H C IR C U IT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AND THE EQUAL

EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION

R O B ERT H . BORK,

Solicitor General,

J . STA N LEY PO TT IN G E R ,

A ssistan t A ttorney General,

L A W R E N C E G. W A LLA CE,

D eputy Solicitor General,

THOM AS S. M A R T IN ,

A ssistan t to the Solicitor General,

B R IA N K. LANDSBERG,

D A V ID L, ROSE,

W IL L IA M B. EENTON,

JE SSIC A DTJNSAY SIL V ER ,

Attorneys,

D epartm ent of Justice,

W ashington, D.C. 20530.

A B N E R W . SIB A L,

General Counsel, .

E qual Em ploym ent O pportunity Commission,

W ashington, D.C. 20506.

3: m

I N D E X

Opinions below--------------------------------------------------------

Jurisdiction-----------------------------------------------------------

Questions presented-------------------------------------------------

Statutory provisions involved------------------------------------

Statement:

Proceedings below----------------------------------------------

A. Proceedings in the district court-------------------------

1. Evidence-------------------------------------------

2. Decision of the district court------------------

B. The decision of the court of appeals-------------------

Summary of argument----------------------------- ----------------

Argument------------------- ------------------------------------------

I. The district court and the court of appeals cor

rectly found, on the basis of statistical evidence

and extensive pre-trial and trial testimony con

cerning individual acts of discrimination, that

T.I.M.E.-D.C. had engaged in a pattern of dis

criminatory employment practices against blacks

and Spanish-surnamed Americans in violation

of Title Y II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964-----

II. A seniority system that penalizes incumbent em

ployees who transfer to higher paying, more

attractive, traditionally white job classifications

from which they previously were excluded,

perpetuates the effects of a pattern and practice

of racial discrimination and violates Title V II—

A. A seniority system which requires vic

tims of racial discrimination to forfeit

their accrued competitive status senior

ity in order to transfer to a job previ-

viously segregated on the basis of race,

perpetuates the effects of prior dis

crimination —

Page

1

2

2

3

4

6

6

13

17

20

25

25

40

40

(!'

II

Argument—Continued

II. A seniority system, etc.'—Continued

B. Section 703 (h) does not safeguard appli

cations of a seniority system which dis

criminate between incumbent workers

on the basis of prior discriminatory Page

job category assignments___________ 44

III. The court of appeals correctly ruled that in a case

where a pattern and practice of discrimination

has been proved an incumbent minority em

ployee seeking rightful place seniority relief

who is a member of the affected class (1) is en

titled to a rebuttable presumption that he was a

victim of discrimination, and (2) need not neces

sarily have unsuccessfully applied for a vacant,

rightful place job to be entitled to relief_______ 52

IV. The court of appeals correctly held that the rights

of members of the affected class to compete for

future vacancies at their home terminals or else

where should not be subordinate either to the

rights of employees transferring from other ter

minals, or to the rights of employees with less

seniority who are on layoff_________________ 64

Conclusion________________________________________ 69

CITATIONS

Cases:

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405---------- 23,53

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36----------- 44,45

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559___________________ 28

Bing v. Roadway Express, Inc., 485 F. 2d 441----------- 58

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F. 2d 711--------42, 50

Cathey v. Johnson Motor Lines, Inc., 398 F. Supp.

1107_______________________________ _________ 44, 68

Comstock v. Group of Institutional Investors, 335

U.S. 211____________________________________ 25

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. De

troit Edison Co., 515 F. 2d 301, petitions for certio

rari pending, Nos. 75-220, 75-221, 75-239, 75-393___ 58

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747_ Passim,

Freeman v. Motor Convoy, Inc., 409 F. Supp. 1100------ 67, 68

HI

Cases—Continued Pa®e

Griggs v. Duke Pouter Go., 401 U.S. 424----- 22,29,43,44, 51

Hairston v. McLean Trucking Co., 520 F. 2d 226— 43, 58, 60

Head v. Timken Boiler Bearing Co., 486 F. 2d 870----- 42

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475-------------------------- 29,30

Johnson v. Ryder Truck Lines, Inc., 10 EPD f 10, 535,

p. 6240, 12 F E P Cases 903-------------------------------- 68

Jones v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 431 F. 2d 245,

certiorari denied, 401 U.S. 954---------------------------- 25, 58

Local 189, United Payer-makers v. United States, 416

F. 2d 980, certiorari denied, 397 U.S. 919--------------- 42,

44,47,48,49, 50

Love v. Pullman, 11 EPD 10, 858, p. 7617, 12 FE P

Cases 339------------------------------------------------------- 58

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co., No.

75-260, decided June 25,1976--------------------------- 57

McDonnell Douglas Corporation v. Green, 411 U.S.

792 __________________________________ — - 37,56,57

Navajo Freight Lines, Inc., 525 F. 2d 1318--------------- 42

National Labor Relations Board v. Bell Aerospace Co.,

416 U.S. 267_________________________________ 51

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587----------------------- 25, 29,30

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505— 47,49, 50

Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. Federal Communica

tions Commission, 395 U.S. 367--------------------------- 51

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F. 2d 791, certiorari

dismissed, 404 U.S. 1006-----------------------------------42,44

Rodriguez v. East Texas Motor Freight, 505 F . 2d 40,

certiorari granted, May 24,1976, Nos. 75-651,75-715,

75-718______________________________________ 18> 58

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F. 2d 348------------ 29, 67

Sabala v. Western Gillette, I-nc., 516 F. 2d 1251, peti

tions for certiorari pending, Nos. 75-781, 75-788----- 43, 60

Sagers v. Yellow Freight System, Inc., 529 F. 2d 721— 18,

58, 68

Senter v. General Motors Corp., 532 F. 2d 511----------- 25

Thornton v. East Texas Motor Freight, 497 F.2d 416— 43

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346------------------- -------- 30

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d

661_________________________________ — - 47, 54, 62

United States v. Central Motor Lines, Inc., 338

F. Supp. 532________________________________ 44, 54

IV

Cases—Continued

United States v. Cheapeake and Ohio Ry. Go., 471 page

F.2d 112_________________________________ 28,67

United States v. East Texas Motor Freight System ,

Inc., 10 EPD 1jl0, 345, p. 5416, 10 F E P Cases 973,

appeal pending, No. 75-3332___________________ 68

United States v. Florida East Coast Railway Co.,

7 EPD |9218, p. 7067, F E P Cases 540___________ 67

United States v. Hayes International Corp., 456

F.2d 112_________________________________ 28,67

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443 F.2d 544_ 33

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d

661, certiorari denied, 406 U.S. 906___________ 47, 54, 67

United States v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 7 EPD

|9066, 6497, 7 F E P Cases 710_____________ 68

United States v. N. L. Industries, Inc., 479 F. 2d

354 ______________________________________ 42,58, 60

United States v. Navajo Freight Lines, Inc., 525 F. 2d

1318_____ 42,43,68

United States v. Pilot Freight Carriers, Inc., 6 EPD

If 8766, p. 5344,6 F E P Case 280______________ 58

United States v. Pilot Freiqht Carriers, Inc., 54 F.E.D.

519_____________________________________ 68

United States v. Roadway Express, Inc., 457 F. 2d

854 _________________________________________ 68

United States v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., 464

F. 2d 301, certiorari denied, 409 U.S. 1116_________ 54

United States v. Terminal Transport Co., 11 EPD

If 10,704, p. 6936______________________________ 68

Washington v. Davis, No. 74-1492, decided June 7,

1976 ________________________ 26

Williamson v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 468 F. 2d 1201,

certiorari denied, 411 U.S. 931__________________ 67

Statutes:

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII, 78 Stat. 253, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. 2000e et seq.

Section 703, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2________________ 42

Section 703 (a ) (1), 42 U.S.C. 2000-2 (a )(1 )_____ 42

Section 703(a)(2), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(a) (2)___ 28

Section 703(h), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(h)_________ 21,

22, 44,45,46,47, 49, 50, 51

Section 703 (j ), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2 (j ) __________ 32, 33

V

Statutes—Continued

Civil Eights Act of 1964—Continued

Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 2000e- page

5(g) ----------------------------------------------- ^

Section 707, 42 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 2000e-6-------- 4,26

Section 707(c), 42 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 2000e-6(c)— 4

Section 707(d), 42 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 2000e-

6(d) ----------------------------------------------- 4

Miscellaneous:

110 Cong. Eec. (1964) :

P.b. 486-488____

P. 1518_________

P. 7213_________

P. 12723________

P. 14270________

46

33

46,50

33

26

118 Cong. Eec. (1972) :

P. 1665 ----------------------------------------------------- 6t

Pp. 1671-1675 ---------------------------------------------

P. 1673 -----------------------------------------------------

P. 1675 -----------------------------------------------------

P. 1676 __________________________________ _

Cooper and Sobol, Seniority And Testing Under Fair

Employment Laws: A General Approach lo Objec

tive Criteria Of Hiring A rnd Promotion, 82 Harv. L.

Eev. 1598 (1969)--------------------------------------------- 49

Note, Civil Rights—Racially Discriminatory Employ

ment Practices Under Title V I I , 46 N.C. L. Eev. 891

(1968)________________________________ - - - - - 48

Note Gould, Seniority and the Black Worker: Reflec

tions on Quarles and Its Implications, 4 ( Tex. L. Eev.

1039 (1969) -------------------------------------------------- 48

Note, Title VII, Seniority Discrimination, and the In

cumbent Negro, 80 Harv. L. Eev. 1260 (1967)----- 47,48, 50

S. Eep. No. 92-415, 92d Cong., 1st. Sess. (1971)-------- 50-51

U.S. Bureau of Census, Census of Population, 1970,

Characteristics of Population, Vol. I, Part 1, p. 1-

392, Table 91: “Occupation of Employed Persons By

Eace, For Urban and Eural Eesidence”--------------- 28

| n the Supreme of the United s ta te s

O ctober T e r m , 1976

No. 75-636

I n te r n a t io n a l B rotherhood of T ea m ster s ,

PETITIONER

V.

U n it ed S tates of A m er ic a and E qual E m pl o y m e n t

O ppo r t u n it y C o m m issio n

No. 75-672

T.I.M.E.-D.C., INC., PETITIONER

V.

U n it ed S tates of A m er ic a and E q ual E m pl o y m e n t

O p po r t u n it y C o m m issio n

ON W R IT OF C E R T IO R A R I TO TH E U NITED S T A T E S COURT OF

A P P E A L S FOR TH E F IF T H CIRCU IT

b r ie f fo r t h e u n it e d st a t e s a n d t h e e q u a l

EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION

O PIN IO N S BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals (A.P. 1-44)*

is reported at 517 E.2d 299. The final order of the

district court entered on March 2, 1973 (A.P. 94-

116), and the order amending the final order entered

on March 19, 1973 (A.P. 117-118), are not officially

reported. An order entered by the district court on

December 13, 1971 (A.P. 45-49) is reported at 335 P.

*“A.P.” refers to the Appendix to Petition for Certiorari

filed by the International Brotherhood of Teamsters in No.

75-636.

(i)

2

Supp. 246. Other orders and opinions of the district

court are not officially reported but are unofficially

reported as follows:

Order entered on January 20, 1972 (A.P. 50-

55) 4 FEP Cases 875; 4 EPD f7881.

Decree in Partial Resolution of Suit (con

sented to by the United States and T.I.M.E.-

D.C.) entered on May 12, 1972 (A.P. 85-93), 4

EPD f7831.

Memorandum Opinion entered on October 19,

1972 (A.P. 56-78), 6 FEP Cases 690; 6 EPD

H8979.

Supplemental Opinion entered on Decem

ber 6, 1972 (A.P. 79-84), 6 FEP Cases 690,

703; 6 EPD 1f8979, p. 6161.

JU R ISD IC T IO N

The judgment of the court of appeals was entered

on August 8, 1975. The petitions for a writ of

certiorari were filed on October 29, 1975, and Novem

ber 6, 1975, respectively, and were granted on May 24,

1976. The jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28 U.S.C.

1254(1).

QUESTIONS PR E SE N T E D

1. Whether the district court and the court of ap

peals correctly found, on the basis of statistical evi

dence and extensive pretrial and trial testimony con

cerning individual acts of discrimination, that

T.I.M.E.-D.C. had engaged in a pattern of discrimi

natory employment practices against blacks and

Spanish-surnamed persons in violation of Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

2. Whether applications of a seniority system that

penalize incumbent employees who transfer to job

3

classifications from which they previously were dis-

criminatorily excluded and perpetuate the effects of

a pattern of exclusion of blacks and Spanish-sur-

named employees from higher paying, more attractive,

traditionally white jobs, violate Title VII.

3. Whether, in a case where a pattern and practice

of employment discrimination had been demonstrated,

an incumbent minority employee seeking rightful place

seniority relief who is a member of the affected class

(1) is entitled to a rebuttable presumption that he was

a victim of discrimination, and (2) need not neces

sarily have applied for a vacant rightful place job to

be entitled to relief.

4. Whether the court of appeals correctly held that,

in the circumstances of this case, the rights of mem

bers of the affected class to compete for future vacan

cies at their home terminals or elsewhere should not

be subordinated either to the rights of employees

transferring from other terminals or to the rights of

employees with less seniority who are on layoff.

STATU TO RY PRO V ISIO N S IN VO LVED

Several pertinent provisions of Title V II of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 are set forth in the Appen

dix to Petition for Certiorari in No. 75-636 (A.P.

119-124).

In addition, Section 706(g) of Title VII, 78 Stat.

261, as amended, 42 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 2000e-5(g),

provides in pertinent part:

If the court finds that the respondent has

intentionally engaged in or is intentionally en

gaging in an unlawful employment practice

charged in the complaint, the court may enjoin

the respondent from engaging in such unlawful

4

employment practice, and order such affirma

tive action as may be appropriate, which may

include, but is not limited to, reinstatement or

hiring of employees, with or without back

pay * * * or any other equitable relief as the

court deems appropriate.

STA TEM EN T

These petitions arise from two Title Y II cases

brought by the United States pursuant to Section 707

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat, 261-262, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 2000e-6 (A.P. 122) 1

alleging a pattern of employment practices that dis

criminate against blacks and Spanish-surnamed

Americans on the grounds of race and national origin.

The first suit, filed on May 15, 1968, in the United

States District Court for the Middle District of

Tennessee, Nashville Division (A. 2),2 alleged discrim

inatory hiring, assignment, and promotion practices

against blacks at the Nashville terminal of T.I.M.E.

Freight, Inc., a common carrier by motor freight

(A.P. 3).

The second suit was brought on January 14, 1971,

against T.I.M.E.-D.C., Inc. (“T.I.M.E.-D.C.” or “ the

Company”) and the International Brotherhood of

Teamsters (“ Teamsters”) in the United States Dis

1 On May 24, 1974, the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit entered an order substituting the Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Commission for the United States as

plaintiff (see 42 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 2000e-6 (c) and (d), A.P. 123-

124) but retaining the United States as a party for purposes of

jurisdiction, appealability, and related matters.

2 “A.” refers to the Appendix filed jointly in Nos. 75-636 and

75-672.

5

trict Court for the Northern District of Texas, Lub

bock Division (A. 2, 4-8). T.I.M.E.-D.C., a successor

of T.I.M.E. Freight, Inc., is an interstate motor car

rier of general commodities and is the product of ten

mergers over a 17-year period (A.P. 5). T.I.M.E.-D.C.

currently has 51 terminals and operates in 26 states

and three Canadian provinces (A. 43). The Teamsters

is an unincorporated labor organization, and certain

locals chartered by it are parties to collective bargain

ing agreements with T.I.M.E.-D.C. (A. 42). All of

T.I.M.E.-D.C.’s line drivers and the vast majority of

its city employees and servicemen work under collec

tive bargaining agreements negotiated for them by

various committees of the Teamsters (A.P. 6, 17).'

The complaint against T.I.M.E.-D.C. and the Team

sters alleged a pattern and practice of hiring, assign

ment, and promotion discrimination against blacks

and Spanish-surnamed Americans throughout the

T.I.M.E.-D.C. system; it specifically alleged that the

seniority system to which the defendants are parties

violates Title V II by perpetuating the effects of past

discrimination (A. 6).

The two suits were consolidated in the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Texas, 3

3 The National Master Freight Agreement is reproduced m

full in P i’s Ex. 203(a) (A. 284), which is entitled “National

Master Freight Agreement and Southern Conference Area

Over-the-Road Supplemental Agreement.” Other area supple

mental agreements in P i’s Exs. 203(a), 203(b), 203(c) and 203

(d) are also part of the same National Master Freight Agree

ment. The National Master Freight Agreement and Southern

Conference Area Over-the-Road Supplemental Agreement is

also contained in P i’s Ex. 202, portions of which are printed

in the joint appendix (A. 795-840).

6

Lubbock Division (A. 3), and a trial was held in May

1972. On May 12, 1972, the district court entered a de

cree consented to by the United States and T.I.M.E.-

D.C. (“Decree in Partial Resolution of Suit”) that

resolved a number of issues relating to T.I.M.E.-D.C.’s

affirmative obligation to recruit and hire qualified

blacks and Spanish-surnamed Americans, and

monetary compensation for those blacks and Spanish-

surnamed Americans alleged to be individual and class

victims of discrimination (A.P. 85-93). Left unre

solved were whether the defendants were in viola

tion of Title VII, the lawfulness of certain aspects of

the seniority system, and the appropriate non-mone-

tary relief.

A. PROCEEDINGS IX THE DISTRICT COURT

In a memorandum opinion dated October 19, 1972,

and a supplemental opinion of December 6, 1972 (A.P.

56-84), the district court issued its findings and con

clusions based on the trial of the remaining issues. It

held that T.I.M.E.-D.C. had engaged in a pattern and

practice of discrimination in violation of Title V II

and that the defendant unions had also violated the

Act by giving force and effect to a seniority system

which perpetuated the effects of employment discrim

ination.

1. Evidence

The district court based its conclusions on a combi

nation of statistical evidence and pretrial and trial testi

mony, the core of which can be briefly summarized as

follows:

The relevant non-managerial employees at T.I.M.E.-

D.C. are divided into three basic job classifications: (a)

7

line driver; (b) city driver, dockman and hostler

(known as “ city operation” jobs); and (c) service

man (which includes tireman) (A.P. 5-6).4 Line

drivers (also known as road drivers) transport

freight in tractor-trailer units over-the-road between

Company terminals. City drivers pick up and deliver

freight within a specified radius of a terminal. Dock-

men (also known as checkers) load, unload and check

freight at the terminal’s dock. Hostlers drive tractor-

trailers around the terminal yard and move trailers

in and out of the dock.5 Servicemen fuel, wash, and

grease trucks and change tires. They also hook and

unhook road and city tractors and trailers and drive

them into and out of the shop.6 7

Generally, T.I.M.E.-D.C. and its predecessors had

no minimum educational requirements for line driver,

city driver, hostler, dockman or serviceman. The

4 The employees in these classifications are, with few excep

tions, covered by separate collective bargaining agreements, or

separate supplemental agreements to the National Master

Freight Agreement. See Pre-Trial Order Appendix B (A. 132-

171), They accumulate seniority on separate seniority rosters.

(A.P. 6). ,

5 Dep. of Kenneth N. Gibbs, Jr., Terminal Manager (Nash

ville), pp. 28-29. The depositions and summaries of depositions

were admitted in evidence as exhibits and were not formally

retranscribed as part of the trial transcript (A. 387-390, 277-

278).

6 Dep. of Dallas R. Anderson, Regional Maintenance Manager

(Nashville), pp. 117-118, 136.

7 Summary of dep. of James W. Frazier, Terminal Manager

(Hayward)', p. 13; summary of dep. of Tobey Beck, Ass’t.

Terminal Manager (Los Angeles), p. 9; summary of dep. ot

Jackson B. Stroud, Operations Manager (Atlanta), pp. 2, 4

(all in P i’s Ex. 240 (A. 277-278D ; dep. of Homer W. Bums,

former Shop Superintendent (Nashville), p. 345.

8

experience requirement generally for line driver

was experience driving tractor-trailer units and, for

city driver, experience driving the type of unit (trac

tor-trailer or straight truck) to be operated on the

job.8

City operation jobs normally pay more than the

job of serviceman;9 however, both job categories usu

ally pay less than the job of line driver. In 1969, line

drivers averaged from $1,300 to $5,500 more per year

than city drivers (A. 898). As the district court found

(A.P. 59), line driver jobs are considered more desir

able than city driver jobs because the line drivers gen

erally receive higher pay and are not required to en

gage in the physically demanding tasks of loading and

unloading the trucks (see A. 339-340).

As of March 31, 1971, T.I.M.E.-D.C. had 6,472 em

ployees, of whom 314 (5%) were black and 257 (4%)

were Spanish-surnamed Americans (A. 43). A large

majority of the black (83%) and Spanish-surnamed

American (78%) employees were assigned to city

operation (city driver, dockman, hostler) or service

man (including tireman) jobs (A. 43-48). By con

trast, less than 39 percent of the 5,901 employees who

8 Dep. of Kenneth N. Gibbs, Terminal Manager (Nashville),

pp. 27-28; dep. of William E. Franzen, Highway Operations

Manager (Denver), pp. 3-4, 10-11; dep. of Anthony W. Lilly-

white, Driver Supervisor (Los Angeles) [5-18-71], pp. 6-12;

summary of dep. of Jackson B. Stroud, Operations Manager

(Atlanta), pp. 2-4 (in P i’s Ex. 240 (A. 277-278)).

9 See P i’s Ex. 230 (Los Angeles, Nashville, Oklahoma City and

San Francisco terminals). At the Denver terminal, servicemen

receive a higher rate of pay than city operation employees. P i’s

Ex. 230, Tab D.

9

were other than black or Spanish-surnamed were as

signed to such positions. The great majority of non

minority employees held line driver, office and super

visory, and mechanic jobs (A. 43—48). Of the 2,545

persons employed as city drivers, dockmen, and hos

tlers, 195 (or 7.7%) were black, and 178 (or 7.0%)

were Spanish-surnamed (A. 43-44, #14).

Although T.I.M.E.-D.C.’s major terminals employ

ing line drivers are located in metropolitan areas hav

ing substantial minority population (A.P. 18-19, 68-

72), of the 1,828 line drivers at the Company as of

March 31, 1971, only 8 (or 0.4%) were black and only

5 (or 0.3%) were Spanish-surnamed American. None

of the eight blacks was employed as a line driver

until 1969, although the government’s Title V II suit

with respect to the Nashville terminal had been filed

on May 15, 1968 (A. 43-44 #14)!° With one exception,

no black was ever employed on a regular basis as a

line driver by T.I.M.E.—D.C. or any of its predecessor

companies prior to 1969 (A.P. 20-21).

The testimonial evidence showed that the statistics

indicating disparate employment opportunities for

blacks and Spanish-surnamed individuals did in fact

reflect discriminatory hiring practices. The testimony

showed that numerous qualified black and Spanish-

surnamed persons who sought initial assignment or

transfer to line driving positions at various terminals

of the Company were denied such jobs after being 10

10 A.P. 19; P i’s Ex. 204. Ex. 204 is a printout showing all of

T.I.M.E.-D.C.’s employees as of March 31, 1971, and it indi

cates, by terminal, each employee's name, job employed date

and ethnic code (A. 279-280). The ethnic codes appear on the

front sheet of the exhibit.

10

given false and misleading information about require

ments, opportunities, and application procedures

(A.P. 60-61, 24).

The evidence concerning the Nashville and Memphis

terminals illustrates the manner in which statistics and

testimonial evidence combined to reveal a pattern and

practice of discrimination. For example, as of March

31, 1971, the statistics on employee complement by job

category at the Nashville terminal revealed that blacks

had not obtained any of the 181 line driver and city

operator jobs.11 12 The Terminal Manager stated in 1966

that blacks had never been considered for any job ex

cept serviceman at the terminal (A. 374-376, 379).18

The district court also found (A.P. 61) that the Com

pany has trained whites, but not blacks, to be me

chanics, partsmen and shop supervisors at the Nash

ville terminal.13 The same statistical pattern of exclu

sion of blacks from line driving jobs was evident at

the Memphis terminal, where no line driver jobs went

to blacks prior to 1969 and only 3 of 104 such jobs

were held by blacks thereafter.14 Yet, from about 1956

until sometime in 1958, the Company permitted white

employees from the city operation (and at least one

11 P i’s Ex. 204, pp. 83-94.

12 The job of serviceman (including fireman) at the Nashville

terminal pays less than the jobs of dockman, hostler, city driver,

partsman, mechanic and line driver. P i’s Exs. 230 (Nashville);

231 (A. 898).

13 Dep. of James E. Mince (Nashville), pp. 182-189; P i’s Ex.

206; P i’s Ex. 89 (to Nashville deps.).

14 P i’s Ex. 204, pp. 57-68.

11

serviceman) to drive extra trips on the line,15 and a

number of these white employees later became regular

line drivers.16 Several black city drivers at the termi

nal requested that they also be permitted to drive on

the line during the period 1956-1958; however, they

were not allowed to do so.17 Testimony indicated that

the Memphis terminal manager eventually stopped the

practice because black city drivers were asking to

drive such trips and he would never permit blacks to

drive on the road.18

The district court found that the seniority system

resulting from the collective bargaining agreements

acted to perpetuate T.I.M.E.-D.C.’s discriminatory

employment pattern (A.P. 61). Under that system, an

employee who moves from a job covered by one collec

tive bargaining agreement to a job covered by another

collective bargaining agreement at any of the Com

pany’s terminals must give up his seniority for all

15 Dep. of W. G. Gately, p. 5; dep. of Arthur L. Thornton,

p. 6; dep. of Fontaine E. Yount, Jr., p. 20 (all taken at

Memphis).

16 The record shows that the following whites transferred

from city operation or serviceman Jobs to line driver at the

terminal during the period 1956-1958: John P. Poston, Jessie L.

Robertson, Jack P. Jones, Ruby Arnold, J. W. Stanford, Max

Seeley. Sources: Summary of dep. of Barton O'Brien, Terminal

Manager (Memphis), pp. 10-12. in evidence as part of P is Ex.

240 (A. 277-278); P i’s Exs. 177, 178, 179, 182, 180 (to Mem

phis deps.) ; dep. of Fontaine E. Yount, Jr., pp. 18-19; dep. of

W. G. Gately, pp. 21-22 (all taken at Memphis).

17 Dep. of Arthur L. Thornton, pp. 5^8; dep. of James II.

Walker, pp. 6, 9; dep. of James L. McNeal, pp. 5-6; summary

of deps, of Charles D. Glover, pp. 1-2, and R. D. Parker, p.

2, in P i’s Ex. 240 (A. 277-278) (all taken at Memphis).

18 Dep. of Fontaine E. Yount, Jr., pp. 2T-25; dep. of W. G.

Gately, pp. 16, 19-20 (taken at Memphis).

225-829 0 - 7 6 - 2

12

purposes except fringe benefits (A. 48). City opera

tion and serviceman jobs are covered by collective

bargaining agreements (or area supplemental agree

ments to the National Master Freight Agreement)

different from those covering line driver jobs (A. 42,

132-171). Consequently, if qualified black or Spanish-

surnamed American employees desire to move to va

cancies in the job of line driver, they are required to

relinquish all of their accumulated seniority for pur

poses of job bidding and protection against layoff

(A.P. 7).19

These seniority provisions are embodied in a Na

tional Master Freight Agreement and area supple

ments, negotiated every three years by the National

Over-the-Road and City Cartage Policy and Negotiat

ing Committee of the Teamsters, and in various area

supplements to that national agreement negotiated by

the National Committee and various area committees

19 The seniority rules have implications for job transfer be

tween geographic locations as well as between job categories.

Employees of T.I.M.E.-D.C. can normally exercise their senior

ity only at the terminal where they are originally hired. How

ever, line drivers domiciled at those terminals of the Company

covered by the Southern Conference Area Over-the-Road Sup

plemental Agreement work under “modified system seniority”.

Under that system, if a line driver is laid off, he can exercise his

seniority to take a line driver job at any other terminal covered

by the agreement, if there is either a vacancy or a line driver

junior to him at the other terminal. I f there is no vacancy, but

only a junior line driver at the other terminal, the transferring

line driver can “bump” that junior line driver out of his job (A.

49). Modified system seniority also requires that, when a terminal

has an opening in a line driver job, it must first offer the job to

laid off line drivers at all other terminals covered by the Southern

Conference Supplemental Agreement before filling the opening

with any other person (A. 49-50).

13

of the Teamsters. The Negotiating Committee repre

sents locals of the Teamsters, including those with

which T.I.M.E.-D.C. has agreements, for purposes of

collective bargaining with the motor carriers. The

Committee is a party to both the National Master

Freight Agreement and its area supplemental agree

ments (A. 797). Each local union gives the Committee

a power of attorney to negotiate on its behalf (A.P.

17). Since the Teamsters is a highly centralized inter

national union (A.P. 17), most of the Negotiating

Committee’s members are either officers or employees

of the International, including its chairman, Frank E.

Fitzsimmons, who is the General President of the

International (A. 649-651). The Area Conferences of

the Teamsters are “ subject to the unqualified super

vision, direction and control of the General Presi

dent” and they must function under the rules pre

scribed in bylaws approved by the General President

(A. 787). Each local union must affiliate with the Area

Conference having jurisdiction over it (A. 788). The

bylaws of each local union are. also subject to the ap

proval of the General President; and if a majority

of local unions vote to hold area, national or industry

wide negotiations, all involved local unions “ must

participate” and “ shall be bound” by the contract if

approved by the majority of the votes cast by the

membership covered by the contract proposal (A. 751,

789).

2. Decision of the District Court

The district court’s memorandum opinion of Octo

ber 19, 1972, found “[a]U of the evidence * * *

ample to show by a preponderance of the evidence”

14

that T.I.M.E.-D.C. was engaged in a pattern and

practice of discrimination in violation of Title Y II

(A.P. 61-62).20 I t also found that the union defend

ants were in violation of Title V II for their part in

negotiating contracts with the Company, which “while

being neutral on their face, do, however, operate to

impede the free transfer of minority groups into and

within the company” (A.P. 61-62).

The government had submitted a list of incumbent

employees as of March 31, 1971, for whom it sought

transfer and seniority relief, basically composed of

blacks and Spanish-surnamed Americans assigned to

city operation and serviceman jobs at those company

terminals which had a line driver operation.21 The dis

trict court found that all of the 358 incumbent black

and Spanish-surnamed American employees of the

Company for whom the government sought relief were

members of an affected class of discriminatees and it

ruled that all of these individuals were entitled to

transfer, if qualified, to future vacancies in jobs from

which they had been excluded as a class (A.P. 62-

20 The relief ordered by the district court in its opinions of

October 19 and December 6, 1972, was embodied in a final order

which it entered on March 2, 1973, and later amended in part

on March 19, 1973 (A.P. 94-118).

21 The list included minority employees hired at terminals

that had a line driver operation during the period in which

T.I.M.E.-D.C. was practicing a plan and pattern of discrimina

tion. Relief was not sought for blacks and Spanish-surnamed

Americans hired at a particular terminal after the date on

which the terminal had employed a minority group member in a

line driver position. Nor was relief sought for minority em

ployees hired during the period after the last white was hired

as a line driver at that particular terminal.

15

65) .22 The district court ordered that all discrimina-

tees who transfer would retain their company

seniority for fringe and retirement benefits (A.P.

66) .23

However, the district court qualified the class relief

in several respects. First, it ruled that a job opening

would not be treated as a vacancy for transfer relief

purposes where it can be filled by a person on the

seniority roster where the job occurs who has been on

layoff for not longer than three years (A.P. 81, para.

IV).24 Second, based upon the evidence submitted by

22 The district court denied relief to three blacks and one

Spanish-surnamed American (see Appendix D of memorandum

opinion, A.P. 78). However, these four persons were appli

cants for jobs at the Company and not incumbents. In a sup

plemental opinion of December 6, 1972 (A.P. 80), the district

court granted relief to these four persons, as well as to three

whites originally denied relief in Appendix D of its memoran

dum opinion.

23 The district court had previously ruled that the Teamsters

International was a proper party to represent and defend the

seniority status of its members and that the Teamsters’ locals

which represented T.I.M.E.-D.C. employees were not indis

pensable parties (A.P. 50-55). The court of appeals subse

quently affirmed those rulings (A.P. 16-18).

24 This ruling, however, simply incorporated the existing pol

icy under the collective bargaining agreements in effect at the

Company which cover employees in jobs represented by the

Teamsters or its affiliated locals. These agreements provide that

individuals on layoff for up to three years have a prior right

to be recalled when openings again occur in those jobs. See,

e.g., National Master Freight Agreement, Art. 5, Sec. 1 (A.

804); Southern Conference Area Over-the-Road Supplemen

tal Agreement, Art. 42, Sec. 1 (A. 823); P i’s Ex. 203(b),

Western States Area Over-the-Road Supplemental Agreement,

Art. 43, Sec. 1(a), (d), pp. 11, 12; P i’s Ex. 203(c), Central

States Area Over-the-Road Supplemental Agreement, Art. 43,

Sec. 1, p. 94.

16

the government in proving the pattern and practice

of discrimination, the court divided the minority in

cumbents into three subgroups reflecting their individ

ual “degree of injury” (A.P. 62-64). Only with

respect to 29 minority employees, whose testimony was

actually placed into evidence, did the court find that

“clear and convincing” proof of discrimination which,

in its view, alone merited a carryover of seniority for

purposes of bidding for jobs and protection against

layoffs (A.P. 64) ,25 Even for these individuals, se

niority carryover was limited to July 2, 1965, the effec

tive date of Title VII, because the effect on innocent

non-minority employees of full seniority carryover

outweighed “the advantage of restoring, as nearly as

possible, an individual to the position that he would

have enjoyed had there never been discrimination”

(A.P. 63).26

The court established a second subgroup made up of

individuals who “were likely harmed” (A.P. 64), but

as to whom the evidence which the government had

presented was “not sufficient to show clear and con-

25 The names of these 29 minority employees and the relief

given them are set forth in Appendices B and C to the mem

orandum opinion (A.P. 73-77). A total of 34 minority em

ployees were granted relief in Appendices B and C ; how

ever, 4 of these (Vestal, Stinson, IJix and Barnes) were appli

cants for jobs at the Company rather than incumbents and a

fifth (Zeno) was given relief only with respect to the equip

ment assigned him.

26 In its memorandum opinion, the district court established

July 2, 1964, as the earliest date for seniority carryover pur

poses (A.P. 64). I t subsequently changed this date to July 2,

1965, in its supplemental opinion of December 6, 1972 (A.P.

82).

17

yincing specific instances of discrimination or liarm

resulting therefrom” (A.P. 64). Their seniority carry

over was limited to January 14, 1971, the filing date

of the Texas suit. As to the third subgroup, the court

was unable to determine whether “ these individuals

were either harmed or not harmed individually” (A.P.

65). I t limited their relief to priority in filling vacan

cies, refusing to award retroactive seniority {ibid.).

B. THE DECISION OF THE COURT OF APPEALS

On appeal, the court of appeals affirmed the district

court’s finding that both T.I.M.E.-D.C. and the Team

sters had engaged in a pattern of employment prac

tices violative of Title VII. The court stated: “[o]ur

careful consideration of the record has convinced us

that * * * the District Court was entitled to conclude

that the defendants have failed to rebut the plaintiffs’

prim a facie case of employment discrimination * * *

that the defendants have engaged in an extensive pat

tern of employment practices unlawful under Title

V II and that strong remedial action is warranted”

(A.P. 29).

However, the court of appeals held that the district

court had erred in using testimony that the govern

ment had introduced in establishing the pattern of

discrimination to delimit the remedies available to in

dividual members of the affected class. Instead, the

court of appeals ruled, the structure of a pattern and

practice suit precludes any requirement for “ individ

ualized proof for every member of a class here num

bering 400 but frequently involving thousands” (A.P.

18

34) ,27 Consequently, the appellate court reversed the

district court’s gradations of the affected class into

subgroups of differing transfer and seniority rights

(A.P. 34). “ [F]or all members of the class there

should be full company employment seniority carry

over for bidding and layoff purposes * * *” (A.P.

38).

The court of appeals also rejected the July 2, 1965

limitation on seniority carryover. Instead, it made all

relief subject to the “ qualification date principle”

(A.P. 38), whereby the seniority carryover date for

bidding and layoff purposes is determined by (1) the

date the incumbent minority employee possessed the

experience necessary to qualify for that job, and (2)

the date thereafter when a vacancy existed (A.P. 32,

38).28 The court of appeals did not specifically discuss

27 As the court of appeals noted (A.P. 29-31, n. 33), the

appeal pertained to the rights of incumbent employees who were

members of the affected class rather than the rights of rejected

applicants for new hire. (The district court had given relief

to some individuals in the latter category, and not to others.)

The court of appeals did direct, however, that the district court

have great flexibility on remand to consider former applicants

who never became incumbents, particularly in light of the fact

that this Court had granted certiorari in Franks v. Boioman

Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (decided subsequent to the

court of appeals’ decision here).

28 See, A.P. 32, n. 35 which in turn refers to Rodriguez v.

East Texas Motor Freight, 505 F. 2d 40, 63 n. 29 (C.A. 5).

The F ifth Circuit has further clarified its position in Sagers

v. Yellow Freight System , Inc., 529 F. 2d 721, 732.

The court of appeals further recognized that if an affected

class member had been denied the opportunity to take tests or

otherwise obtain the requisite experience for a job in the past,

his qualification date for purposes of determining seniority

carryover should normally be fixed as of the date in the past

19

petitioners’ opportunity to prove that some individ

uals were not in fact victims of previous discrimina

tion (cf. Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424

U.S. 747, 772), but merely held that showings of

individual injury were not required for every mem

ber of the affected class in the liability stage and that

“ [wjhatever evidentiary hearings are required for in

dividuals can be postponed to the remedy” (A.P. 34).

Finally, the court of appeals temporarily modified

the seniority agreements in two respects. The court

ruled that to allow laid off line drivers a three-year

priority on filling future openings in line driver jobs

over the bidding rights of more senior members of the

affected class would unduly impede the eradication of

past discrimination. Hence, it directed that when a

vacancy which is not purely temporary arises in a line

driver job, a member of the affected class may com

pete against any line driver on layoff for that vacancy

on the basis of his carryover seniority date, with the

opening to go to the competing individual with the

greatest seniority (A.P. 41). The court of appeals also

held that all members of the affected class are to have

preference in filling future vacancies in line driver

jobs at their home terminals ahead of laid-off line

drivers transferring in from other terminals (A.P 42).

on which he could have qualified for the job had he been given

the opportunity to establish his qualifications (A.P. 32, n. 34).

This refinement of the “qualification date principle” is neces

sary to cover situations such as existed at the Nashville ter

minal, where the district court found that the Company had

provided training to whites, but not blacks, to enable them to

become mechanics, partsmen and shop supervisors (A.P. 61).

20

SU M M A RY OP A RG U M EN T

A. Petitioner T.I.M.E.-D.C. challenges the concur

rent factual determinations, reached by the court of

appeals and the district court, that T.I.M.E.-D.C.

engaged in a pattern and practice of discrimination

in the hiring and transfer of its employees. However,

the undisputed evidence indicates enormous statistical

disparities, in the higher paying and more desirable

line driver positions, between the employment of blacks

and Spanish-surnamed persons, on the one hand, and

non-minority individuals, on the other. For example,

only one percent of the approximately 1,800 line

driver jobs were held by these minority individuals in

1971, even though many of the company’s terminals

are located in areas with large minority populations.

At the same time, large numbers of apparently quali

fied blacks and Spanish-surnamed persons were rele

gated to less desirable city operation and servicemen

jobs. In the absence of any persuasive explanation for

these flagrant statistical disparities, the courts below

were entitled to draw an inference of discrimination,

and shift to the defendant the burden of showing

that a pattern and practice of discrimination had not

occurred.

However, neither court below based its conclusion

that a pattern and practice of discrimination existed

on statistical evidence alone. The record was replete

with testimonial evidence that qualified minority ap

plicants who sought line driver jobs had their requests

ignored, were given false and misleading information,

or were not considered on the same basis as whites.

21

Petitioner T.I.M.E.-D.C. has failed to make the ex

ceptional showing of error that alone would justify

this Court’s review of these findings based upon the

entire record and unanimously concurred in by both

courts below.

B. Both courts also correctly concluded that the

pattern of racially segregated departments which was

established by T.I.M.E.-D.C. is perpetuated by a de

partmental seniority system embodied in collective

bargaining agreements negotiated by the Interna

tional Brotherhood of Teamsters. Under this system

a victim of discrimination who wishes to transfer to

a line driver job must forfeit the seniority which he

has accrued through service in the only company

job that he was permitted to obtain. Because this

loss of bidding rights and protection against layoff

would threaten a transferring employee’s economic

survival, the seniority system acts as a substantial

impediment to transfer. Even if he transfers, the mi

nority individual is placed forever behind his white

contemporaries with respect to the terms and condi

tions of his employment and the allocation of scarce

employment benefits. Petitioner International Broth

erhood of Teamsters nevertheless claims that because

the seniority system was itself negotiated in good

faith without racial intent and is a bona fide seniority

system within the meaning of Section 703(h) of Title

V II there is no violation of Title VII.

Title V II is directed at the consequences of employ

ment procedures, and practices “ neutral on their face,

and even neutral in terms of intent, cannot be main

tained if they operate to "freeze’ the status quo of

22

prior discriminatory employment practices.” Griggs

v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 430. Section 703(h)

of Title VII, 78 Stat. 257, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(h),

was intended to protect the seniority system as a

governing principle in labor management relations.

Neither its terms nor its legislative history re

quire its application to claims of incumbent mi

nority employees who are locked into less desirable

jobs by departmental seniority systems which per

petuate the effects of an original discriminatory as

signment. Application to these individuals of earned

company seniority in a rightful place job fits them

properly into, rather than abrogates, the existing

seniority system, and can hardly be said to threaten

the vitality of seniority systems generally. Congress

has endorsed the prevailing interpretation of the

courts of appeals that Section 703(h) does not in

sulate applications of a seniority system which prevent

victims of discrimination from using their earned

company seniority when they transfer to their right

ful place position.

C. Adequate relief for victims of racial discrimi

nation in employment may require a remedy slotting

the victims into the seniority positions that would have

been theirs absent discrimination. Franks v. Bowman

Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 776-777. Identify

ing the individual victims of discrimination entitled

to claim this seniority relief presents a difficult prac

tical problem, the answer to which will turn on

whether the claim and findings involve individual or

class discrimination, the reasonable inferences that

can be drawn from the factual record, and the nature

of the unlawful practices followed by defendants.

23

In a case where a pattern and practice of discrimi

nation has been demonstrated, this Court has already

held that the burden shifts to the defendants to

prove that members of the injured class were not

victims. Franks, supra, 424 U.S. at 772. By contrast,

the district court below placed the burden of proving

that members of the class were victims on the mem

bers of the class themselves (or, here, the government

suing on their behalf) and based the allocation of

remedies on the strength of the efforts made on behalf

of each of them. The court of appeals properly re

versed, and reset the order and allocation of proof in

a manner which anticipated Franks. Petitioners’ argu

ment that district court discretion should be sustained

in the face of a failure to apply the proper legal

principles regarding the allocation of the burden of

proof is wrong under both Franks and Albemarle

Paper Co. v. Moocly, 422 U.S. 405, 416.

D. The court of appeals also correctly held that, in

the particular factual circumstances of this case, indi

viduals seeking relief as victims of discrimination need

not show that they had unsuccessfully applied for a

vacant line driver position. The repetitious and contin

uing quality of a pattern and practice of discrimina

tion has the practical effect of discouraging both ini

tial and follow-up applications. Here the class of af

fected individuals are incumbents, and it is especially

likely that they both knew of, and responded to, the

pattern of segregated jobs; indeed there is evidence in

the record here to that effect. To require minority em

ployees to have applied for transfer to a segregated

job in order to qualify for relief penalizes them for

failing to perform what they knew to be a vain and

24

useless act. Moreover, the presence in this case of a

seniority system with transfer penalties acted as an

added deterrent to any application.

The court of appeals’ remedy does not constitute a

preference for all minority employees. The only mem

bers of the class entitled to seniority relief are those

incumbent minority employees who were qualified

when discrimination occurred and when vacancies

were available, and whose present desire to transfer

suggests that a similar opportunity to transfer in the

past would have been accepted.

E. The court of appeals correctly held that the

rights of members of the affected class to compete for

future vacancies at their home terminals or elsewhere

should not be subordinated to the rights of employees

transferring from other terminals or to the rights of

employees with less seniority who are on layoff. This

temporary modification of applicable seniority rules

with respect to victims of discrimination who opt to

accept the class relief constitutes a limited and prac

tical device to provide a reasonable expectation of ob

taining a rightful place vacancy without undue delay.

The court of appeals drew upon its frequent experi

ence with discrimination remedies in the context of

the trucking industry and correctly concluded that

this temporary modification of seniority rules would,

with fairness, increase the possibility that the effective

relief which Title V II mandates would be achieved.

Petitioners charge that non-minority employees may

be adversely affected, but the impact is not severe and

represents a reasonable application of the principle

that “a sharing of the burden of the past discrimina

6

25

tion is presumptively necessary.” Franks v. Boivman

Transportation Co., supra, 424 U.S. at 777.

A RG UM EN T

I

THE DISTRICT COURT AND THE COURT OF APPEALS COR

RECTLY FOUND, ON THE BASIS OF STATISTICAL EVIDENCE

AND EXTENSIVE PRE-TRIAL AND TRIAL TESTIMONY CON

CERNING INDIVIDUAL ACTS OF DISCRIMINATION, THAT

T.I.M.E.—D.C. HAD ENGAGED IN A PATTERN OF DISCRIMI

NATORY EMPLOYMENT PRACTICES AGAINST BLACKS AND

SPANISH-SURNAMED AMERICANS IN VIOLATION OF TITLE

VII OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 19 64

A “ seasoned and wise” rule of this Court is that, in

the absence of an “exceptional showing of error,” the

concurrent factual findings of two lower courts will be

considered final. Comstock v. Group of Institutional

Investors, 335 U.S. 211, 214. The presence of statis

tical as well as testimonial evidence in the decision

making record hardly provides a reason to diverge

from that prudential rule. The use of statistics in

proving racial discrimination is long established in

this Court (Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587), and

frequent usage in the court of appeals 29 has demon

39 Jones v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 431 F.2d 245 (C.A.

10), certiorari denied, 401 U.S. 954. See cases cited at A.P. 23,

n. 27. The Company suggests that the Sixth Circuit has taken a

different view of statistical evidence in Senter v. General Motors

G o r y 532 F.2d 511, 527 (Br., p. 14, n. 28). While the 8 enter

court did state that the statistics there were “not conclusive,”

it also pointed out that the Sixth Circuit “generally acknowl

edge [s] the value of statistical evidence in establishing a prima

facie case of discrimination under Title V II.” 532 F.2d at 527.

26

strated their utility in Title V II litigation. Statistical

evidence, indicative of a recurring quality in the acts

charged, is especially pertinent in a pattern and

practice suit in which the court must determine

whether a company has regularly engaged in dis

criminatory acts.30 By challenging the significance of

statistical comparisons and the adequacy of the data

base, in light of the alleged implications of various

disqualifying factors (T.I.M.E.-D.C. Br., p. 14-25),

T.I.M.E.-D.C.31 seeks to involve this Court in the fact

finders’ function of evaluating the adequacy of evi

dence and drawing appropriate and reasonable

inferences. Moreover, the testimonial and statistical

evidence here was tellingly probative, and indeed com

pelled the finding of a Title V II violation. These

essentially factual conclusions unanimously reached

by the judges below should not be disturbed.

The courts below correctly held that the largely un

disputed statistical and anecdotal evidence established

a prima facie case of discrimination. With one excep

tion, no black was ever employed on a regular basis

as a line driver by T.I.M.E.-D.C. or any of its prede

cessors until 1969.32 As late as March 1971, almost

30 The legislative history of Section 707 indicates that a “pat~

tem or practice” suit is appropriate when a company has regu

larly engaged in prohibited acts. See, e.g., 110 Cong. Rec. 14270

(1964) (remarks of Senator Humphrey). In 'Washington v.

Davis, No. 74-1492, decided June 7, 1976, this Court described

the rigorous standard of review that follows from an appro

priate statistical showing in a Title V II case.

31 Notably only petitioner T.I.M.E.-D.C. questions the suffi

ciency of the eyidence.

32 One black ^employed as a line driver at the Chicago termi

nal from 1950 to 1959 (A.P. 20).

27

three years after the original Nashville suit had been

initiated, and five years after the effective date of

Title VII, there were only 8 (0.4%) blacks and 5

(0.3%) Spanish-surnamed Americans working in the

pool of 1,828 line drivers employed by T.I.M.E.-D.C.

At the same time, the great majority of black (83%)

and Spanish-surnamed American (78%) employees

were assigned to city operation and serviceman jobs,

while only 39 percent of other employees held jobs in

those categories.33 Indeed, in 1971, when less than one

percent of the line driver jobs wTere filled by blacks

and Spanish-surnamed Americans,34 several terminals

33 See pp. 8-9, supra. While the most pervasive discrimination

found was in keeping blacks and Spanish-surnamed Americans

out of line driver jobs, at some terminals they have also been

excluded from less desirable jobs. The district court found, for

example, that black employees at the Nashville terminal were

denied training to become mechanics, partsmen, or shop super

visors (A.P. 61). See also p. 10, supra.

34 T.I.M.E.-D.C. appears to attack the district court’s finding

(A.P. 59), affirmed by the court of appeals, that line driver,

which pays as much as $1,300 to $5,500 more per year than city

driver and does not involve loading and unloading trucks, is a

more desirable job than city driver (T.I.M.E.-D.C. Br., p. 19).

The record amply supports the court’s finding (see A. 898,

339-340). While the Company introduced exhibits indicating

that, in 1971, city drivers at two terminals averaged more pay

than line drivers (Defs’ Exs. MMM, PPP, A. 986, 987, 635-

636), there is no such evidence respecting any other terminals.

Moreover, the Company’s exhibits also show that systemwide,

in 1971, line drivers earned more than city drivers (line one

of Defs’ Exs. MMM, PPP, A. 986, 987). Further, Charles

F. Hutchinson, T.I.M.E.-D.C.’s Personnel Manager, testified

that studies done by the Company which compared the earnings

of line drivers and city drivers for the years 1969 and 1970, in

which the earnings of those drivers making less than $3,000

were excluded, disclosed no instances where line drivers earned

less than city drivers (A. 626). In any event, the discrimi

225-829 0 - 76 - 3

28

located in areas with a large percentage of blacks in

the population still had no black line drivers.35 I t is

clear that blacks and Spanish-surnamed Americans

were available, because they were employed by the

company in less desirable jobs, including city driver

jobs requiring qualifications similar to those of line

drivers. In 1971, blacks and Spanish-surnamed Amer

icans constituted 15% of the employees in city opera

tion jobs for T.I.M.E.-D.C.36 In these circumstances,

the prima facie inference that the exclusion of quali

fied blacks and Spanish-surnamed Americans from

more desirable jobs was a result of invidious dis

crimination is compelling. As Mr. Justice Frankfurter

observed more than twenty years ago: “The mind of

justice, not merely its eyes, would have to be blind to

attribute such an occurrence to mere fortuity.” Avery

v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559, 564 (concurring opinion).

Petitioner offered no explanation for the great sta

tistical disparity in the employment of black and

Spanish-surnamed Americans in line driver jobs and

their employment in city driver and less desirable

natory exclusion of a protected class from any job category

would violate Section 703(a)(2). See, e.g., United States v.

Hayes International Corp., 456 F.2d 112, 118 (C.A. 5).

35 Compare line driver statistics for Atlanta, Dallas, Los

Angeles, and Memphis terminals (A.P. 70-72) with popu

lation statistics for those areas (A.P. 68-69); see also A.P. 25,

n. 29. According to 1970 Census data, blacks comprise 13.4%

of all “truck drivers.” U.S. Bureau of Census, Census of Popu

lation, 1970. Characteristics of Population, Yol. I, Part 1, P.

1-392, Table 91: “Occupation of Employed Persons by Race, for

Urban and Rural Residence.”

36 See p. 9, supra.

29

jobs, other than the general statement that it hired the

best qualified applicants (T.I.M.E.-D.C. Br., p, 21).

Cf. Norris v. Alabama, supra, 294 U.S. at 598; Her

nandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475, 480-481. There was no

evidence that the exclusion of minority employees

from line driver jobs was due to any valid job require

ment ; 37 the only significant requirement for a line

driver position was experience driving tractor-trailer

equipment,38 39 experience which many of the city drivers

either had when they applied for a job at T.I.M.E.-

D.C. (A. 325-327, 370), or acquired as a result of city

driving.30 Even where it was asserted that there was a

minimum driving requirement, that requirement was

not applied uniformly, and there is evidence that it

was waived for white applicants.40 Both courts below

suggested that unexplained statistical disparities of

the magnitude present in this case (A.P. 18-22) can

shift the burden of proof. On this point, the court of

appeals specifically referred to its prior ruling in

Rowe v. General Motors Gorp., 457 P. 2d 348, 358

(C.A. 5), that “figures of this kind while not neces

sarily satisfying the whole case, have critical, if not

decisive, significance—certainly, at least in putting on

37 Had such a requirement been asserted as the reason for dis

parate job assignment statistics, petitioner T.I.M.E.-D.C. would

have been required, to show that the requirement was supported

by business necessity. Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424,

432. No such evidence was adduced.

38 See, e.g., deps. of Ned M. Rockwell, May 17, 1971, at 7-8,

Kenneth N. Gibbs, Jr., pp. 27, 70-72; D. N. Champlin, pp. 15, 18,

64; Robert C. Cathey, pp. 22-23; and p. 8, supra.

39 A .'325-327, 370-71.

40 See, e.g., deps. of Kenneth N. Gibbs, Jr., pp. 27, 70-72; Don

Capshaw, pp. 294-295.

30

the employer the operational burden of demonstrating

why, on acceptable reasons, the apparent disparity is

not the real one” (A.P. 23). That statement is correct.

While the use of statistics to shift the evidentiary

burden is most familiar to this Court in jury selection

cases (see, e.g., Norris v. Alabama, supra; Hernandez

v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475; Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S.

346),41 the burden-shifting inference is equally appro

priate in a Title V II pattern of discrimination suit

which similarly requires more than isolated rejections

of qualified individuals. As in a jury selection case,

statistical disparities of sufficient magnitude may show

that a pattern exists and, in the absence of satisfactory

explanation, compel the common sense conclusion that

the disparities are not fortuitous.

The intensity of the statistical showing here vitiates

petitioner’s quibbles with the precision of the govern

ment’s statistics. In the face of a showing that less

than one percent of petitioner’s 1,800 line driver posi

tions were filled by minority employees, the courts be

low were entitled to reject the attempts of petitioner’s

witnesses to undermine the impact of the statistics. As

the court of appeals stated, “the inability to rebut

came not from lack of an informed standard. Rather,

in most instances for LDs [line driver], the inability

came from the inexorable zero” (A.P. 25).

Indeed, most of petitioner’s statistical points are

deficient on their face. For example, petitioner chal

lenges the use of the S.M.S.A. as a basis of compari

41 The disproportions in the present case greatly exceed that

found in Turner, su/pra, 396 U.S. at 359 (37% blacks on a grand

jury as compared to 60% of the total population) to warrant

corrective action by the courts.

31

son of minorities employed to minorities available in

the community (T.I.M.E.-D.C. Br., p. 18) ; however,

the order under review here provided class relief only

for incumbent employees and relied principally on the

statistical disparity between employment of incum

bent whites and employment of incumbent blacks and

Spanish-sumamed Americans in more desirable jobs

(A.P. 18-22). Petitioner does not even address the

evidence of statistical disparity in the concentration

of these minority employees in the less desirable jobs.

Similarly, petitioner 'cites statistics indicating hiring

practice improvements in 1971 (T.I.M.E.-D.C. Br., p.

18), but the violations found occurred prior to 1971

and the relief afforded was limited to the pre-1971

period (A.P. 12, 29-30, n. 33). Moreover, petitioner’s

overall work force statistics do not indicate the jobs to

which minority employees were assigned, a pivotal

point in this litigation.

Thus, this is not a case where “ fine tuning” of

statistics to reflect those portions of the minority com

munity suited by age and health to a job (T.I.M.E.-

D.C. Br., pp. 19-20) would have any effect on the out

come. Where, as here, the job requirements were rela

tively minimal, the incumbent statistics egregious, and

the testimonial evidence compelling, no useful purpose

would be served by a requirement (involving substan

tial costs) to develop more precisely the statistics

comparing minority hiring to minority availability in

the area.42 To prohibit the use, for prima facie pur

42 Petitioner attacks the use of Standard Metropolitan Statis

tical Area and Urban Place statistics (Br., p. 18 and n. 39). City

statistics were also introduced (see A.P. 68-69). I f the avail

32

poses, of obviously helpful and reliable, available

statistics because more sophisticated statistics could

be created would be counterproductive to Title V II

goals, without advancing the cause of judicious resolu

tion of Title V II disputes.

The use of statistics by the courts below to draw

simple, prima facie evidentiary inferences is not, as

petitioner argues, an attempt to impose a racial bal

ance standard for violations of Title V II ; nor is it an

attempt to force “ preferential treatment” of minori

ties as a requirement of law in derogation of Section

703(j) (T.I.M.E.-D.C. Br., pp. 14-16). The eviden

tiary inferences that arise from the statistics are based,

not upon failure to achieve racial balance, but rather

upon “ flagrant statistical deviations” (A.P. 23) from

employment patterns which presumably would reflect

an unbiased hiring process. Such evidentiary show

ings are clearly, within the contemplation of the

statute. Here, where the employer charged with dis

crimination has more than 6,000 employees located at

51 terminals in 26 states, and the class of alleged dis

ability of prospective minority employees is to be determined

by any other geographical standard, petitioner has not indi

cated what it might be.

Citing the testimony of one of its trial witnesses, a professor

of psychology, T.I.M.E.-D.C. asserts that he demonstrated re

spondent’s statistics to be unreliable to predict the availability

of blacks and Spanish-surnamed Americans to join the work

force at the respective terminals (Br., pp. 19-20). Neither of

the courts below found this witness’s testimony adequate to

undermine respondent’s proof. Moreover, the witness acknowl

edged that the only information available respecting black and.

Spanish-surnamed American population was that utilized by

the government (A. 564).

33

criminatees numbers more than 300, the use of statis

tics is essential in establishing a pattern and practice

of discrimination. Far from reflecting a standard of

racial preference which Section 703 (j) prohibits, the

use of these statistics is in an effort to determine

whether the employer utilized legitimate and objective

considerations in hiring in accordance with the Title

Y II standard.43 That Section 703(j) is not intended to

preclude such evidentiary showings is made clear in

the legislative history of the 1972 Amendments to the

Act, which indicates that Congress both knew and ap

proved of court reliance on statistical evidence to

draw inferences and, in appropriate cases, to shift the

burden of proof.44 *

While the statistical evidence of gross disparities

in the allocation of line driver jobs to minority and

non-minority employees could alone have supported a

43 See remarks of Senator Humphrey, 110 Cong. Rec. 12723

(1964) (A. 190); remarks of Congressman Celler, 110 Cong. Rec.

1518 (1964) (A. 189).

44 Congress, in passing the 1972 Amendments to Title YII,

was fully aware that the appellate courts were using severe

statistical disparities as a basis for shifting the burden of proof.

An amendment was introduced by Senator Ervin wdiich would

have amended Section 703(j) to bar use by any federal agency

or federal court of quotas, goals or other numerical ratios. Sen

ator Ervin argued that Section 703(j) was being misconstrued

to permit use of numerical ratios. The floor managers of the

bill, Senators Williams and Javits, cited and relied inter alia

upon United States v. Ironworkers Local 86,443 F.2d 544 (C.A. 9),

and reprinted that opinion in full in the Congressional Record,

118 Cong. Rec. 1665, 1671-1675 (1972). That opinion contains

a classic statement of the courts’ reliance on statistical evidence

to draw inferences and to shift the burden of proof, 443 F.2d at

551; 118 Cong. Rec. 1673, 1675 (1972). The Senate accepted the

Williams/Javits position and voted to reject Senator Ervin’s

amendment by a vote of 22-44 (118 Cong. Rec. 1676 (1972).

34

prima facie case, the statistical showing was also

matched by compelling testimonial evidence.45 Numer

ous experienced and qualified black and Spanish-

sumamed drivers who applied for line driver posi

tions, or who asked to transfer to such positions, had

their requests ignored, or otherwise were denied the

opportunity, after being given false information.46

Moreover, there was substantial evidence that the

practice of denying those minorities such positions

was motivated by considerations of race and national

origin.47

While both courts below noted that statistics may

establish a prima facie case, both went on to consider

the testimonial evidence and neither based its conclu

46 Petitioner T.I.M.E.-D.C. also attacks the testimonial evi

dence as involving incidents “too isolated in number and in time

to serve as a basis for a finding of a systemwide pattern or

practice of discrimination” (Br., p. 20). Testimony was taken

from approximately ten percent of the members of the class

for whom relief was sought. As the court of appeals noted:

“The [ten] terminals at which the Government took depositions

are spread throughout the entire T.I.M.E.-D.C. system”, and con

tain seven of the ten largest line driver operations, domiciling

1,171 line drivers (A.P. 26 and n. 30).

Petitioner’s reference to the period of time over which the

incidents occurred appears to be intended as an attack upon

the relevance of discriminatory acts occurring prior to the effec

tive date of Title VII. Evidence of such pre-Act discrimination

is relevant in two ways. First, it is evidence that there was a

long-standing practice which may have continued past the Act’s

effective date. Second, since part of respondent’s case charges

that the seniority system perpetuates the effects of past discrim

ination, evidence of pre-Act discrimination lays part of the

ground work for that claim.

46 See pp. 9-10, supra.

47 See pp. 9-11, supra.

35

sion that a pattern of discrimination had been estab

lished on the statistics alone (A.P. 60-61, 23-24;

compare T.I.M.E.-D.C. Br., pp. 14-25). Thus, the

court of appeals observed (A.P. 26) that there was

evidence of more than 40 specific instances of discrim

ination throughout the system of T.I.M.E.-D.C.—in

stances often egregious and viewed as a whole quite

definitely supporting the finding that a pattern and

practice of discrimination occurred.