Notice of Service of Defendants' Response to the Plaintiffs' Sixth Request for Production of Documents with Certification

Public Court Documents

October 26, 1992

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Notice of Service of Defendants' Response to the Plaintiffs' Sixth Request for Production of Documents with Certification, 1992. b1093d8e-a546-f011-8779-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a0e7dd2e-e8ae-4c27-8bdb-d1fb090ca1f4/notice-of-service-of-defendants-response-to-the-plaintiffs-sixth-request-for-production-of-documents-with-certification. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

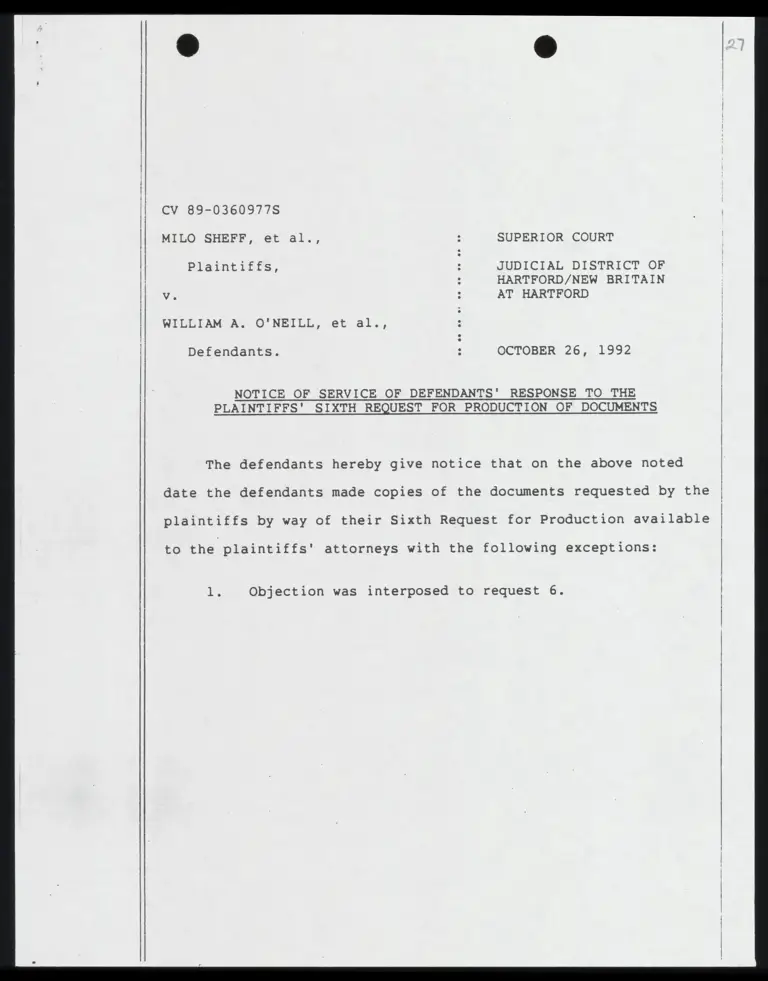

CV 89-0360977S

MILO SHEFF, et al., : SUPERIOR COURT

Plaintiffs, : JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF

: HARTFORD/NEW BRITAIN

Vv. : AT HARTFORD

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, et al.,

Defendants. 3 OCTOBER 26, 1992

NOTICE OF SERVICE OF DEFENDANTS' RESPONSE TO THE

PLAINTIFFS' SIXTH REQUEST FOR PRODUCTION OF DOCUMENTS

The defendants hereby give notice that on the above noted

date the defendants made copies of the documents requested by the

plaintiffs by way of their Sixth Request for Production available

to the plaintiffs' attorneys with the following exceptions:

1. Objection was interposed to request 6.

FOR THE DEFENDANTS

RICHARD BLUMENTHAL

ATTORNEY GENERAL

7

/

/

BYt An Ll lr pan

“John R. Whelan

Assistant Attorney General

110 Sherman Street

Hartford, CT 06105

ermal 366 7173

Mr As 2H

ton watts ¢

Assistant Attorney General

110 Sherman Street

/ Hartford, CT 06105

Telephone: 566-7173

CERTIFICATION

This is to certify that a copy of the foregoing was mailed,

postage prepaid on October 26,

record:

John Brittain, Esq.

University of Connecticut

School of Law

65 Elizabeth Street

Hartford, CT 06105

Philip Tegeler,

Martha Stone,

Esq LJ

Esq.

Connecticut Civil Liberties Union

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CT 06106

Ruben Franco, Esq.

Jenny Rivera, Esq.

Puerto Rican Legal Defense Fund

and Education Fund

14th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

John A. Powell, Esq.

Helen Hershkoff, Esq.

Adam S. Cohen, Esq.

American Civil Liberties Union

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

MMWO0203AC

1992 to the following counsel of

Wilfred Rodriguez, Esq.

Hispanic Advocacy Project

Neignborhood Legal Services

1229 Albany Avenue

Hartford, CT 06112

Wesley W. Horton, Esq.

Moller, Horton & Fineberg P.C.

90 Gillett Street

Hartford, CT 06106

Julius L. Chamberes, Esq.

Marianne Lado, Esq.

Ronald Ellis, Esq.

NAACP Legal Defense Fund and

Educational Fund

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

Ll gL

tha MY watts/ a

ei Attorney General.