Freeman v. Motor Convoy, Inc. Brief for the Union Defendants-Appellants

Public Court Documents

May 17, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Freeman v. Motor Convoy, Inc. Brief for the Union Defendants-Appellants, 1977. 856bad84-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a1177612-762f-46de-afa4-c7ec67f7aaf5/freeman-v-motor-convoy-inc-brief-for-the-union-defendants-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

<

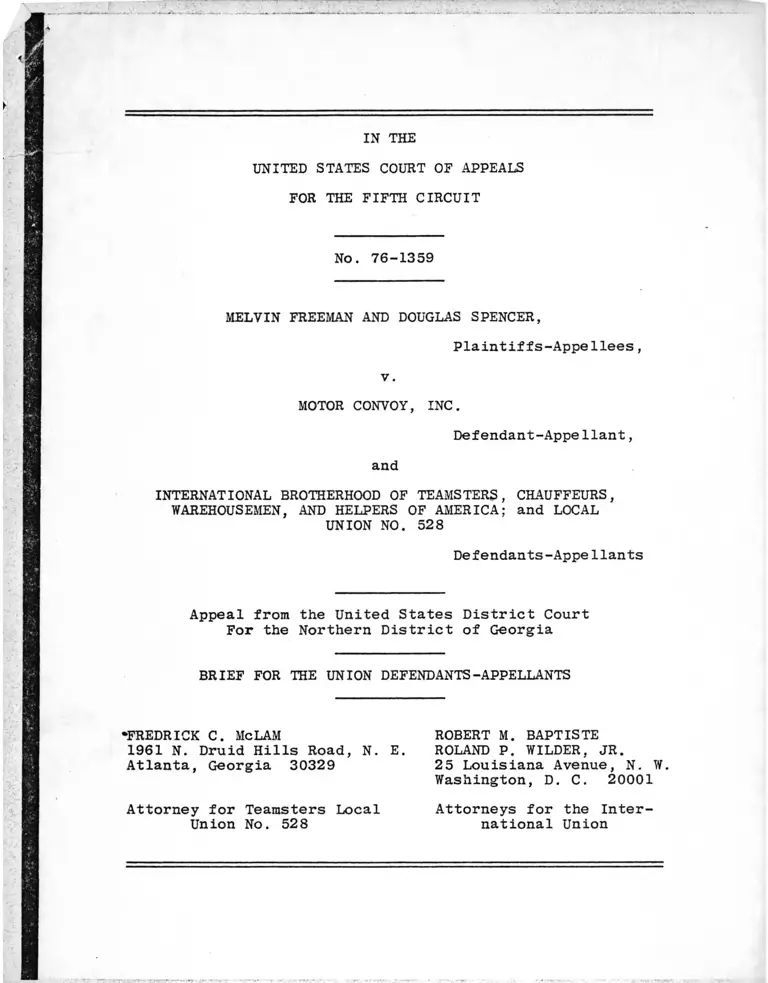

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OE APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 76-1359

MELVIN FREEMAN AND DOUGLAS SPENCER,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

MOTOR CONVOY, INC.

Defendant-Appellant,

and

INTERNATIONAL BROTHERHOOD OF TEAMSTERS, CHAUFFEURS,

WAREHOUSEMEN, AND HELPERS OF AMERICA; and LOCAL

UNION NO. 528

Defendants-Appe Hants

Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Georgia

BRIEF FOR THE UNION DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS

•FREDRICK C. Me LAM

1961 N. Druid Hills Road, N. E.

Atlanta, Georgia 30329

ROBERT M. BAPTISTE

ROLAND P. WILDER, JR.

25 Louisiana Avenue, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20001

Attorney for Teamsters Local

Union No. 528

Attorneys for the Inter

national Union

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 76-1359

MELVIN FREEMAN AND DOUGLAS SPENCER,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

MOTOR CONVOY, INC.,

and

Defendant-Appellant,

INTERNATIONAL BROTHERHOOD OF TEAMSTERS,

CHAUFFEURS, WAREHOUSEMEN AND

HELPERS OF AMERICA,

and TEAMSTERS LOCAL UNION NO. 528,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Georgia

CERTIFICATE OF COUNSEL

The undersigned, counsel of record for International

Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers of

America, Defendant-Appellant, certifes that the following listed

parties have an interest in the outcome of this case. These

representations are made in order that Judges of this Court may

evaluate possible disqualification or recusal pursuant to Local

Rule 13(a) .

, ,11

Melvin Freeman,

Douglas Spencer,

Zonnie Jones,

L. Higgins,

H. Brooks,

W. Allen,

J . D. Glass,

S . Freeman,

K. Norwood,

E . Brooks,

G. Brooks, MacArthur Foy, and

W. Samuels,

Plaintiffs-Appellees.

Motor Convoy, Inc.,

Defendant-Appellant.

Teamsters Local Union No. 528,

Teamsters Local Union No. 612,

Southern Conference of Teamsters, and

International Brotherhood of Teamsters,

Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers

of America,

Defendants-Appellants.

ROLAND P. WILDER, JR.

Attorney of Record for International

Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs,

Warehousemen and Helpers of America

NECESSITY FOR ORAL ARGUMENT

There is a superficial resemblance between this case and

the freight industry cases under Title VII. As a result, the Panel

is likely to have questions to ask counsel. In addition, this is

the first discrimination case to arise in the car-haul industry

and is of vital importance. The issues deserve full exploration,

including oral argument.

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

CASES:

Aeronautical Indus. Dist. Lodge 727 v.

Campbell, 337 U.S. 521 (1949) 40

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) 51, 52

Barefoot v. International Brotherhood of

Teamsters, 424 F.2d 1001 (C.A. 10), cert.

denied, 400 U.S. 950 (1970) 58

Benjamin v. Western Boat Building Corp.

472 F.2d 723 (C.A. 5, 1973) 54

Carey v. Greyhound Bus Co., 500 F.2d 1372 (C.A.

5, 1974) 51

Coronado Coal Co. v. UMW, 268 U.S. 295 (1925) ,59

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d

398, (C.A. 5, 1974), rev'd on other grounds,

423 U.S. 814 (1976) 34, 40

Gamble v. Birmingham Southern R.R., 514 F.2d

678 (C.A. 5, 1975) 49

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) 39

Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Corp., 498 F.2d

641 (C.A. 5, 1974) 49

Herrera v. Yellow Freight System, Inc., 505 F.2d

66 (C.A. 5, 1974) 59

IBEW (Franklin Elec. Constr. Corp.), 121 N.L.R.B.

143 (1958) 59

International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S.

310 (1945) 54

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d

1364 (C.A. 5, 1974) 34, 51

Johnson v. Ryder Truck Lines, Inc., 10 EPD

11 10,535 (1975), judgment issued, 11 EPD

11 10,692 (W.D. N.C. 1976), aff'd, 13 EPD

11 11,607 (C.A. 4, 1977) 49

LeBeau v. Libby-Owens-Ford Co., 484 F.2d 798(C.A. 7, 1973) 57

IV

Page

Macklin v. Spector Freight System, Inc., 478 F.2d

979 (C.A . D.C. 1973), complaint dismissed on

remand, 9 EPD 11 10,154 (D. D.C. 1975), aff'd,

13 EPD 1[ 11,418 (C. A . D.C. 1977) 51

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.3. 792

(1973) 36

Murray v. OCAW Local 8-472, 88 L.R.R.M. 2119

(D. Conn. 1974) 40

Myers v. Gilman Paper Co., 544 F.2d 837 (C.A. 5,

1977) 45, 49, 57, 58

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 535 F.2d 257

(C.A. 4, 1976) 57

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d

211 (C.A. 5, 1974) 34

Quarles v. Phillip Morris, 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D.

Va. 1968) 34

Resendis v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 505 F .2d

69 (C.A. 5, 1974) * 59

Rodriguez v. East Texas Motor Freight System, Inc.,

505 F.2d 40 (C.A. 5, 1974), cert, granted,

44 U.S.L.W. 3670 (U.S., May 25, 1976), Nos.

75-651, 75-715, 75-718) 4, 33, 37, 42, 43

Roman v. ESB, 13 EPD 1[ 11,285 (C.A. 4, 1977) 33, 35

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348

(C.A. 5, 1972) 33, 46, 47

Sabala v. Western Gillette, Inc., 516 F.2d 1251

(C.A. 5, 1975) 42, 54

Sagers v. Yellow Freight System, Inc., 529 F

721 (C.A. 5, 1976)

.2d

54, 58 r 59

Stevenson v. International Paper Co., 516 F.

103 (C.A. 5, 1975)

2d

45

Thornton v. East Texas Motor Freight, Inc.,

497 F.2d 416 (C.A. 6, 1974) 43, 44

United Constr. Workers v. Haislip Baking Co.,

223 F.2d 872 (C.A. 4), cert, denied, 350

U.S. 847 (1955) 59

UMW v. Coronado Coal Co • / 259 U.S. 344 (1922)

U.P.P. Local 189 v. United States, 416 F.2d

980 (C.A. 5, 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S.

919 (1970)

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 3 [CCH]

EPD 1! 8318 (N.D. Ga. 1971) , aff'd in part,

vacated for consideration of other issues

and remanded, 474 F.2d 906 (C.A. 5, 1973)

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co.,

451 F.2d 418 (C.A. 5, 1971), cert, denied,

406 U.S. 906 (1972)

United States v. T .I.M.E.-D.C., Inc., 517 F.

299 (C.A. 5, 1975), cert, granted, 44 U.S.

3699 (U.S., May 24, 1976) (Nos. 75-636, 75 672)

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159 (C

'5,' 1976)--------- -----

Wright v. Rockefeller, 372 U.S. 52 (1963)

STATUTES:

Judicial Code:

28 U.S.C. §§ 1291, 1292(a)

Civil Rights Act of 1964

Georgia Code Ann. § 3-119

2d

L.W.

.A.

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 76-1359

MELVIN FREEMAN AND DOUGLAS SPENCER,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

MOTOR CONVOY, INC.,

Defendant-Appellant,

and

INTERNATIONAL BROTHERHOOD OF TEAMSTERS,

CHAUFFEURS, WAREHOUSEMEN AND

HELPERS OF AMERICA,

and TEAMSTERS LOCAL UNION NO. 528,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Georgia

BRIEF FOR THE UNION DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1. Did the lower Court err in concluding that

-2-

the Plaintiffs-Appellees and members of the class they

purported to represent were discriminatorily assigned

on the basis of race to garage jobs, where such conclu

sion was based solely on evidence of statistical im

balance in the Defendant-Appellant Employer's road de

partment?

2. Does a union violate Title VII by negotia

ting and maintaining a classification seniority system,

where:

a. Prior to October, 1969, unor

ganized employees without seniority

rights commenced their seniority upon

transfer to bargaining unit jobs in

the Road department; and

b. Upon organization in October,

1969, such employees voted against

carryover seniority between the Garage

and Road departments and in favor of

classification seniority?

3. Does a union discriminatorily "lock" black

employees hired without mechanical skills into inferior

jobs by negotiating and maintaining contractual provisions,

entailing training and layoff protection, which provide for

automatic advancement to the best jobs available at the

Employer's facility, whether or not vacancies are avail

able, in the absence of evidence that such employees were

-3-

denied access to the advancement procedure and the Union

knew of such denial?

4. Did the lower Court err in finding the De-

fendants-Appellants Unions jointly liable with the Em

ployer for monetary awards to Plaintiffs-Appellees and

members of the class they purported to represent, based

solely on the Local Union's action in negotiating senior

ity provisions selected by the class members themselves?

5. Was the International Union properly found

responsible for "discriminatory" seniority provisions ne

gotiated by committees composed of Local Union officials,

acting for and on behalf of Local Unions holding exclusive

representational rights for the employees involved, where:

a. The International Union holds

no representational rights for involved

employees and is not signatory to the

collective bargaining agreement;

b. The seniority provisions in

issue were neogtiated historically by

Local Union officials; and

c. Seniority is considered a mat

ter of local concern, and seniority sys

tems may be tailored to the needs and

desires of employees at individual term

inals by Local Unions?

-4-

6. Does a union violate Title VII by continu

ation of a "color-blind" seniority system, lawful on its

face, simply because it provides for accrual of competi

tive seniority in separate departments, where:

a. The seniority system was not

a product of an intent to discriminate;

and

b. There is no evidence that the

Union participated in alleged hiring

and assignment discrimination by the

Employer?

7. Is a seniority system providing for ac

crual by all employees of seniority from the date of en

try into a department "bona fide" within the meaning of

Section 703(h)?

8. May fictional seniority credits be awarded

to all minority employees, solely on the basis of their

race, without regard to whether they were individually

affected by the alleged pattern or practice of discrimina-

*/tion?—

Issues 6, 7 and 8 are currently before the Supreme

Court in United States v. T.I.M.E.-D.C., Inc., 517 F.2d

299 (C.A. 5, 1975), cert, granted, 44 U.S.L.W. 3669 (U.S., May 24, 1976) (Nos. 75-636, 75-672) and Rodriguez

v. East Texas Motor Freight System, Inc., 505 F.2d 40

(C.A. 5, 1974), cert, granted, 44 U.S.L.W. 3670 (U.S.,

May 25, 1976) (Nos. 75-651, 75-715, 75-718). They are

presented in this appeal solely to preserve them pending

the Supreme Court's final action. Thus issues 6, 7 and 8 will not be actually argued here.

-5-

forum?

9. Was the International amenable to suit in the

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The United States District Court for the Northern

District of Georgia handed down its judgment and order, with

an accompanying opinion, on December 11, 1975; it is reported

at 409 F. Supp. LlilO and is reprinted in the Joint Appendix,

at . On February 11, 1976, the District Court supple

mented its judgment and order pursuant to a motion for recon

sideration made by Plaintiffs-Appellees. The District Court's

Order on Reconsideration is informally reported at 13 EPD

1(11,518; it is reprinted in the Joint Appendix, at

The Union Defendants-Appellants filed a timely notice of ap

peal from the District Court's Order of December 11, 1975, and

further filed a timely supplementary notice of appeal from the

District Court's Order on Reconsideration. The notice and sup

plementary notice are reprinted in the Joint Appendix, at

This Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §§ 1291,

1292 (a).

A. Statement of Facts

1. Nature of the Employer's Operation and Hourly

Rated Jobs. Defendant-Appellant Motor Convoy, Inc. (herein

after the "Employer") is an interstate carrier of motor vehi

cles; it was incorporated under Georgia law in 1934, and main

tains its principal office in Atlanta, Georgia. (Tr. I, 13)

In addition, the Employer maintains facilities located in the

-6-

following cities: Jacksonville, Miami and Tampa, Florida; Bir

mingham, Alabama; Baton Rouge, Louisiana; and Nashville, Tennes

see. (P. Exh. 18)— ̂ Within the Southern Conference of Team

sters, as of March 10, 1975, the Employer employed 204 road dri

vers, of whom 5 were black (2 at Atlanta and 3 at Birmingham);

24 yard employees, of whom 2 were black (1 at Atlanta and 1 at

Birmingham); and 40 shop employees, of whom 10 were black and

located at the Atlanta facility. (P. Exh. 18)

The Employer's business consists entirely of trans

porting new vehicles from the manufacturer or importer to dis

tribution points, where they are marketed to the public. Ap

proximately 75 percent of its business is derived from the Ford

Motor Co. (Tr. Ill, 81, 83); it fluctuates in the same manner

as does the auto manufacturer's business. Automobiles and other

new vehicles (units) may be picked up directly at the manufac

turer's plant, or at railheads if they are shipped by rail, and

then delivered to dealers. (Tr. Ill, 80) The basic equipment

utilized by the Employer is an auto rack, holding six to eight

new vehicles, which is hauled by a diesel-powered tractor.

(Tr. Ill, 84) Due to the cyclical nature of the Employer's

business, its need for drivers varies considerably during the

model year. (Tr. Ill, 82-83)

1/ The Employer also maintains additional facilities in North

and South Carolina within the Eastern Conference of Teamsters.

These facilities are not affected by this action because the

scope of the class was restricted to the Southern Conference of Teamsters. (JA ) .

The hourly rated jobs at the Employer's terminal fa

cilities fall generally into three categories: road drivers,

yard employees and shop or garage employees. Road drivers are

responsible for operating equipment and loading units; checking

and noting damages; keeping daily logs and-expense records; and

following Government regulations as well as procedures estab

lished by the Ford Motor Co. (Tr. Ill, 84-88; P. Exh. 21, 1[ 3B)

Experience is preferred but is not an absolute prerequisite for

being employed as a road driver. The formal requirements for

the job are that the applicant be: (a) twenty-one years of age;

(b) pass the ICC physical examination; (c) pass a road driving

test and an open-book test on applicable Government regulations;

(d) possess a valid driving license; and (e) have a good driving

record. (Tr. I, 16-17) All drivers are on a single seniority

list for each terminal; there are no separate "city" and "road"

classifications. (P. Exh. 14) The Employer's Atlanta drivers

have been represented since the early 1950's (Tr. I, 13-14),

first by Teamsters Local 728, and by Teamsters Local 528 after

1965. (Tr. Ill, 14, 19)

The duties of employees in the Yard Department in

cluded the checking and signing for new units from Ford Motor

Co., driving the units from Ford to the Employer's facility,

moving the units to bay areas from which drivers pick them up

for loading, and assisting drivers in checking and inspecting

units received by truck or railroad. (Tr. Ill, 88-89; P. Exh.

21, K 3A) Qualification criteria for yardmen include the abil

ity to read and write, the requirements of good eyesight and

-8-

normal physical condition, and the possession of a valid driving

license.

Shop employees work in the garage servicing tractors

and auto racks. Their duties include welding, mechanical work

on engines (both gasoline and diesel), greasing vehicles, chang

ing tires, steam cleaning and general clean-up work. Signifi

cant job skills are required in order to be a welder or mechanic.

All of the Employer's welders and mechanics, other than Plaintiff

Freeman, had prior experience and were fully qualified at hire.

(Tr. Ill, 92, 103) Other jobs in the garage require less skill.

Thus cleaning duties are performed by porters, while tire chang-

ing, greasing and gassing of equipment are performed by helpers

or apprentice mechanics, as they are now classified.

2. Recruitment and Hiring. Recruitment and hiring

for all positions, including road jobs, are accomplished by De

fendant Motor Convoy primarily through word-of-referrals and

wal^-i-ns>" (Stip., 11 11.) Local Union No. 528 plays no role

whatever in the recruitment or hiring process. (Tr. II, 134)

Motor Convoy employed its first black driver at Atlanta on May

28, 1971. Thereafter, eight additional black drivers were

either hired or offered jobs at Atlanta, of whom tyo remain in

the~ernpXoyme1it~TeTatXonThdp^ (Tr. I, 16-17) Three other black

drivers were employed at Defendant Company's Birmingham Termi

nal on February 1, 1973. (P. Exh. 14, at 65) No road jobs

were available at the Atlanta terminal in 1969 or 1970. (P.

Exh. 23, 115)

-9-

Defendant Motor Convoy never maintained a policy of

excluding blacks from its road department before or after enact

ment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. (Tr. Ill, 136, 170) At

least since the late 1960's, the Employer has been engaged in

actively recruiting black drivers (Tr. Ill, 133-135, 157-159,

179-182, 185, 203) and its hiring personnel have long been in

structed to hire blacks for road jobs whenever minimum quali

fication standards were met. (Tr. Ill, 179-182, 185, 203)

These efforts were initiated because few black drivers had ap

proached the company seeking employment. CTr. m , 133-35, 157)

In recent years since 1965, opportunities for road jobs have

declined, as evidenced by the fact that the road board at At

lanta now carries only 140 drivers, including those on layoff,

down from approximately 214 drivers in 1965. (Tr. I, 16; II,

81)

Seven yardmen are employed at Defendant Motor Convoy's

Atlanta facility, of whom one is black. (Tr. I, 16) The last

yardman employed at Atlanta was hired in 1969. Employment op

portunities in the shop also have declined because Motor Convov

has been replacing its gasoline powered equipment with diesels

needing less maintenance. Accordingly, only five employees

have been hired in the shop since 1965 and only one was hired

after 1968.

3. Assignment of Hirees to Jobs and Departments.

Black employees currently on the Atlanta shop seniority roster

were assigned to shop jobs at hire by the Employer's officials.

-10-

Only two— J. D. Glass and Grover Brooks— claimed prior driving

experience. The remaining employees in the alleged class had

no particular qualifications for road jobs, if any, that were

available at the time they were hired.- These employees ac

quired whatever driving ability they now claim while in Motor

Convoy's employ. (U. Exh. 17, at 10; Tr. I, 104; Tr. II, 151)

Brooks' truck driving experience occurred in the Army; it

was limited to driving a truck to the mess hall. (Tr. II, 15)

J. D. Glass tractor-trailer experience in the Army was limited

to twenty-five miles per day in Korea. He also testified to

driving a small truck for the Hapeville Lumber Co. (Tr. I,

135-136)

Consistent with its preference for experienced dri

vers (Tr. I, 16) Defendant Motor Convoy has hired and assigned

to its road department sixteen whites and two blacks not having

actual road experience before coming to work. (P. Exh. 12; D.

Exh. 1) Six inexperienced whites were employed and assigned as dri

vers in 1953; three were employed in 1954, 1955 and 1957, respec

tively; two others were employed in 1958; the next two were hired in

1959 and 1963, respectively; two more were hired in 1968; and the

last white driver without road experience was hired in 1971. (P. Exh.

14, at 52) No black shop employee was hired during the years 1953,

2/. MacArthur Foy, a black driver domiciled at the Employer's Birmingham facility, had prior trucking experience with furni

ture companies and hauling slag. (Tr. II, 157) He was hired

as a yardman on September 7, 1971. (Tr. II, 152) He trans

ferred to the road on February 1, 1973, as soon as he bid.

Only two vacancies arose— on June 29, 1972 and January 8, 1973— between his hire and transfer. (P. Exh. 14, at 65)

-11-

1958, 1959, 1968 or 1971. (P. Exh. 14, at 40) There is no in

dication that any black shop employee made application for a

driving job, or expressed any interest in driving at hire.

A comparison of the hire dates of black shop employees

employed in 1954, 1955 and 1957 with those of white drivers with

out experience employed during those years discloses the follow

ing :

Black Shop Employees White Drivers

Name Hire Date Name Hire Date

L. Higgins 6/4/54 J. A. Carter 12/17/54H. Brooks 2/17/55 H. D. Hicks 6/9/55W. Allen 3/9/55J. D. Glass 6/3/57 W. C. Bates 8/26/57

Between the dates Higgins and Carter were hired in June and De

cember, 1954, Defendant Motor Convoy employed four experienced

road drivers. Similarly seven drivers with experience were

hired between February and June, 1955, when Brooks and Hicks

were employed, respectively, four of whom were hired after

Allen but before Hicks. (P. Exh. 14, at 52-53)

4. Collective Bargaining Negotiations in the Car-Haul

Industry. Car-Haul bargaining on a multi-employer, multi-union

basis began in 1948, when Local Unions in the Southern and Cen

tral Conferences negotiated an agreement with their Employer

counterparts. This agreement was designated a "National Agree

ment, " even though it did not purport to cover Local Unions and

Employers located in other sections of the United States. (Tr.

Ill, 44—45) Sectional bargaining in the industry continued ex

clusively until 1967, when the first National Master Automobile

-12-

Transporters Agreement was concluded. The National Agreement

provided uniformity with regard to certain conditions of em

ployment, but left to sectional bargaining all terms and con

ditions of employment as to which uniformity was considered

unnecessary or infeasible. (Tr. Ill, 45-46) From 1958, it

has been recognized that uniform seniority arrangements in

the Car-Haul industry were not feasible. (Tr. Ill, 64-65)

The Employer and Teamsters Local 528 are parties to

the National Master Automobile Transporters Agreement and the

Central and Southern Conference Areas Supplemental Agreements.

(Tr. I, 13) Local 528, as the successor to Teamsters Local

728, has been the exclusive bargaining representative for the

Employer's drivers since December, 1965, and for its shop and

yard employees in Atlanta since late 1969. (Tr. Ill, 174-175)

The Employer's Birmingham employees are represented by Team

sters Local 612. The International Union holds no representa

tional rights among the Employer's employees. (Tr. Ill, 58-59)

The National Master Agreement was negotiated for Locals 528 and

612 in both 1970 and 1973 by the National Automobile Transpor

ters Union Committee. (P. Exhs. 19, at 59; 37, at 49) The

Conference Area Supplemental Agreements were negotiated in 1970

and 1973 by the Central and Southern Conference Supplemental

Agreement, Truckaway Negotiating, Local Negotiating and Garage

Negotiating Committees. (P. Exhs. 19, at 100, 135, 157 & 168;

37, at 85, 122, 144 & 156) The Committees obtain their ne

gotiating authority under powers of attorney by which Local

-13-

Unions, the exclusive bargaining agents of employees, authorize

the Committees to act on their behalf. (Tr. Ill, 59-60)

In both 1970 and 1973, the National Negotiating Com

mittee was composed of Local Union officials selected by dele

gates from all Local Unions having members working in the Car-

Haul industry. (Tr. Ill, 41-44) Walter J. Shea, a salaried

employee of the International Union, also served on the Na

tional Committee. (Tr. Ill, 43) The Central and Southern

Conference Negotiating Committee in 1970 and 1973 was composed

exclusively of Local Union officials selected by delegates from

Local Unions representing car haulers within the Conference

Areas. (Tr. Ill, 65-66) The International Union's General

President, F. E. Fitzsimmons, was listed as the titular chair

man of both the National and Conference Negotiating Committees.

His role was restricted to attendance at the first meeting of

Local Unions in 1970 prior to commencement of negotiations. He

attended no meetings in 1973, and had no part in the negotia

tions for either the 1970 or 1973 contract. (Tr. Ill, 56)

Nor did Mr. Fitzsimmons appoint the members of various commit

tees established by the contract. (Tr. Ill, 49)

The manner in which proposals were developed and ne

gotiations were undertaken on the Union side were the same in

1970 and 1973. The Union proposals for the National Master

and Supplemental Agreements were formulated by the National

and Supplemental Union Negotiating Committees, respectively.

(Tr. Ill, 57) In drafting such proposals, the Committee

-14-

members reviewed suggested contract changes submitted by each

Local Union having members working in the Car-Haul industry.

(Tr. Ill, 57, 74) After the initial proposals for the Master

and Supplemental Agreements were drafted, they were reviewed

by delegates from each Local Union and approved for presen

tation to the Employers. (Tr. Ill, 57) Bargaining then com

menced with an exchange of initial proposals. Negotiations

for the National Master and Supplemental Agreements in both

1970 and 1973 were conducted separately.

Upon reaching tentative agreement with the Employers

on the National and all Supplemental Agreements, the proposed

agreements are submitted to a ratification vote by the member

ship working in the Car-Haul industry for approval or disap

proval. (Tr. Ill, 58, 61-62) In both 1970 and 1973, the Na

tional and all Supplemental Agreements were ratified by the

membership. Under the International Constitution, "if a ma

jority of the votes cast by Local Union members voting approve

such contract, it shall become binding and effective upon all

Local Unions involved and their members." (P. Exh. 32, Art.

XVI, § 4(a))

5. Seniority Practices Under the Agreements and

Local Riders. Seniority is dealt with substantively in the

National Master Automobile Transporters Agreement only in

regard to the merger, acquisition or purchase of carriers

(P. Exhs. 19 & 37, Art. 5, § 1(1)), the opening or closing

of branches, terminals, divisions or operations (id., § 2),

-15-

and the means by which employees laid off at one terminal can

obtain work at another terminal where additional help is needed

(id*/ § 3). Otherwise the National Master Agreement deals with

seniority in general terms:

Terminal seniority shall prevail to the

extent to which it is set forth in writing

in this Agreement and in each of the Sup

plemental Agreements hereto, including Local Riders . . . . [Id., §1.]

The extent to which seniority is applied and accrued,

as well as the methods of such application, at covered

terminals is set forth in the Central and Southern Conference

Areas Supplemental Agreements covering Truckaway Local and Ga

rage operations. (P. Exhs. 19 & 37) Seniority provisions

covering Garage employees are set forth in Part V of the Sup

plemental Agreement. Article 81, § 1 of the 1973-76 Agreement

(P. Exh. 19) and Article 77, § 1 of the 1970-73 Agreement (P.

Exh. 37) provide as follows:

(a) Company garage seniority shall

be determined by the time and date each

employee's payroll earnings begin, as of' his last hire-in date.

(b) Garage employees shall not bump into any other division nor shall any em

ployee from another division exercise sen- ority in the garage.

(c) Classification seniority shall

commence at the time and date each employee's

payroll earnings begin in such classification

Separate seniority lists are also maintained in the

Yard and Road divisions.

-16-

Transfer between divisions at Motor Convoy's Atlanta

terminal with carryover competitive seniority is not permitted,

and no employee has ever transferred while retaining his ac

crued company seniority, except for fringe benefits and vaca

tions.—^ (Tr. I, 14-15, 17) Employees on layoff, however, are

permitted to return to work in a division other than the one

from which they were laid-off, while retaining their seniority

standing and recall rights to their former jobs. Upon being

recalled, however, the employee must decide whether to return

to his former job, or remain in his new department. If he

elects to remain in his new department, his seniority dates

from the time he began therein and he forfeits all rights in

his old department. (Tr. I, 14-15) Intervenor Spencer moved

to a road job with Local 528's assistance under this procedure.

(Tr. I, 99-100; II, 197-99) Likewise, employees W. Samuels

and M. A. Foy obtained road jobs at Birmingham in this fashion,

although Mr. Samuels was not on layoff at the time. (Tr. Ill,

108)

Both the National Master and the Central and Southern

Conference Areas Supplemental Agreements authorize Local Unions

to negotiate local riders with individual employers "governing

any phase of employment they mutually deem necessary . . . ."

(P. Exh. 19, Art. 2, § 6; P. Exh. 37, Art. 2, § 2.) "[T]he

— _ At Motor Convoy's Birmingham terminal, however, a local

rider permits yard employees to exercise their seniority in the office and clerical department. (Tr. Ill, 188)

-17-

Local Union and the Employer must make a concerted effort to

mutually agree on Local Riders." (Id., § 7) Seniority is

specifically designated as a suitable subject for local rider

treatment. (P. Exh. 19, Art. 5, §§ 1 & 4, Art. 37, §§ 1 & 6;

P. Exh. 37, Art. 5, §§ 1 & 4, Art. 33, §§ 1 & 6) Although

Local Unions and employers are empowered to execute local

riders changing the provisions of the supplemental agreements,

these riders must be approved by the Central-Southern Confer

ence Joint Arbitration Committee, a body composed of equal

numbers of employer and local union officials involved in the

auto transportation industry within the Central and Southern

Conference Areas. (P. Exh. 19, Art. 2, § 6; P. Exh. 37, Art.

2, § .6; Tr. Ill, 46-52)

In order to process and approve local riders, the

Joint Conference Committee for the Central and Southern Con

ferences formed a subcommittee called the "Rider Committee."

The function of this subcommittee was to review the numerous

riders negotiated by Local Unions and employers shortly after

the National Master Agreement, together with its Supplemental

Agreements, was executed to insure that such riders do not

undercut the wage and fringe standards established by the Sup

plemental Agreements. International officials do not serve on

the Joint Grievance Committee or its Rider subcommittee. The

decision of the Grievance Committee approving a rider is final

and not subject to further review. (Tr. Ill, 46, 52)

Local riders establishing seniority rules different

than those set forth in the Supplemental Agreements are used

-18-

extensively in the auto transportation industry. As a result,

seniority systems (considered to be a matter of local concern)

differ substantially from employer to employer and even from

terminal to terminal. (Tr. Ill, 64) Defendant Local 528 has

negotiated local riders with Complete Auto Transit, one of the

Employer's competitors, that provide for carryover seniority

between the Yard and Road divisions at Atlanta (U. Exh. 14),i/

and carryover seniority between the Garage and Road divisions

at Doraville, Georgia. (Tr. II, 212-14; Tr. Ill, 63-64) Other

instances of local rider departure from the Supplemental Agree

ments were also noted on the record. (Tr. II, 180-181, 214;

Tr. Ill, 188)

6. Defendant's Shop and Yard Before Their Unioniza

tion in 1969. Before 1969, none of the shop employees was clas

sified, although the terms "mechanic" and "helper" have since

been used to describe their job functions. (Tr. Ill, 90) Only

trained mechanics and welders performed skilled work on engines

and auto racks; however, these employees also were called upon

to perform less skilled and even unskilled tasks. (Tr. I, 84-

85) Less skilled employees did a variety of jobs in the shop

and the yard consistent with their ability as assigned by super

visory personnel. (Tr. Ill, 90-91) Such jobs would include the

greasing, gassing and cleaning of equipment, as well as changing

or repairing tires and general clean-up work.

1/ Complete's Atlanta shop employees voted to rescind the carry

over seniority provisions of their local rider in the early 1960's. (Tr. IV, 25)

-19-

Plaintiff Freeman, sometimes assisted by J. D. Glass,

frequently worked at changing engines. This involved unbolting

the engine, removing some equipment that could interfere with

the change or be damaged by it, lifting the engine with a

hoist, and replacing the engine with another by reversing

the process. (Tr. I, 146-47, 149) No actual mechanical

work on the engine was performed during the change. (Tr. Ill,

92) Neither Freeman nor Glass performed line mechanical work

prior to 1969. (Tr. I, 88, 147) Freeman was paid 15jzf to 20jzf

per hour less than the skilled mechanics. (Tr. Ill, 90) He

was compensated at a higher rate than was J. D. Glass. (Tr.

I, 140)

Defendant Motor Convoy did not maintain any rule for-

shop employees from transferring to the Road department

before or after 1965. (Tr. Ill, 133, 136) It was well under

stood, however, that since the shop was unorganized and thus

its employees were not in the bargaining unit represented by

the union, that such transferees would have to start in the

Road department at the bottom of the seniority list. As a

practical matter, this involved no hardship for transferees

from the shop or yard because such employees had no seniority

to lose. (Tr. Ill, 150) While there is a dispute whether

Plaintiff Freeman requested a transfer to a road job (Tr. Ill,

160), he testified that he was told that he would have to re

sign and begin as a new employee for competitive purposes.

(Tr. I, 36)

-20-

V

£

In 1965, pursuant to direction of its Board of Di

rectors, the Employer offered its black yard and shop employ

ees the opportunity to transfer to road jobs as vacancies arose.

(Tr. Ill, 132) It was understood that these unorganized employ

ees, without seniority rights, would have begun their seniority

for competitive purposes upon entry into the bargaining unit.

(Tr. Ill, 109, 132) There was no response to this offer, ap

parently because the shop employees preferred the stability of

their jobs to the fluctuations in road work. (Tr. Ill, 133)

The transferring employee would have been required to terminate

his employment in the non-union department after qualifying for

a bargaining unit job. (Tr. Ill, 109, 117)

7. Organization of the Shop and Yard By Local 528.

Teamsters Local 528 is an autonomous labor organization, af

filiated with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. It

elects its own officers free from International supervision

or control. The Local Union maintains its own bank accounts and

other property; the International Union has no right to, or con

trol over, such properties. Other than receiving a monthly per

capita tax, the International plays no role in Local 528's fi

nancial affairs. (Tr. Ill, 20-22) The Local Union decides what

units to organize, and carries on its own organizational activ

ities. No International officials, employees or agents assisted

Local 528 in organizing employees, negotiating contracts or

processing grievances from its inception in 1965. (Tr. Ill,

66-67)

-21-

Local 528 succeeded in obtaining recognition for the

shop employees upon a showing of a majority of authorization

cards in October, 1969. (Tr. I, 14; II, 175) Several weeks

later, Defendant Motor Convoy extended recognition to Local

Union No. 528 for the Yard upon a majority showing among yard

employees. (Tr. IV, 10) Sometime after October 13, 1969, but

before organization of the Yard (Tr. IV, 11, 26), a meeting of

shop employees was held for the purpose of voting whether to

apply the classification seniority provisions of the Central

and Southern Supplemental Agreements, or to negotiate a rider

with Motor Convoy providing for a form of seniority carryover

between the Garage and Road divisions, similar to that negoti

ated by Local 528 with Motor Convoy's closest competitor, Com

plete Auto Transit. Shop employees were notified of this meet

ing by a notice posted on a bulletin board at the shop. Ap

proximately fifteen or sixteen employees, only three of whom

were white, attended this meeting. (Tr. II, 179)

Employees attending this meeting voted against allow

ing shop employees to exercise seniority in the Road division

and permitting drivers to exercise seniority in the shop. (Tr.

II> 179-180) This proposal, which was enthusiastically sup

ported by the drivers who were subject to frequent layoffs due

to the seasonal nature of Motor Convoy's business (Tr. IV, 5-

"7, 15-17) , was rejected by shop employees because they were

concerned about the possibility of being bumped by road dri

vers. (Tr. IV, 24-25) This result was similar to the decision

-22-

of shop employees at Complete Auto Transit's Atlanta facility

where, in 1961, they voted to rescind a seniority carryover

system between road and shop departments that had been in ef

fect for many years. (Tr. IV, 14, 25) Accordingly, the Em

ployer and Local Union entered into a rider agreement for the

period October 13, 1969 through May 31, 1970, which, inter

alia, applied the seniority provisions of the Supplemental

Agreements to the shop. (P. Exh. 7)

The procedure followed in this matter was consistent

with Local Union No. 528's practice of first ascertaining the

wishes of the smaller department in the matter of seniority

rights, instead of submitting the matter directly to a vote

of all affected employees, where the smaller group would be

dominated by the larger. (Tr. IV, 22-23) This was particu

larly important at Motor Convoy's Atlanta facility because the

road drivers had long been on record as favoring carryover

seniority between the Road, Yard and Shop divisions. (Tr.

IV, 23-25) Consistent with the above-described practice, yard

employees subsequently decided against affording carryover sen

iority between the Road and Yard divisions, opting instead for

the seniority provisions of the Central and Southern Conference

Areas Supplemental Agreements. (Tr. IV, 13-14)

8. Advancement and Transfer After Unionization of

of the Shop and Yard Employees. Under the provisions of the

Central and Southern Garage Supplement (P. Exh. 19, Art. 81,

§ 1; P. Exh. 37, Art. 77, § 1), an employee's company garage

-23-

seniority shall be determined by the time and date his payroll

earnings begin; he "shall not bump into any other division nor

shall any employee from another division exercise seniority in

the garage;" and his "classification seniority shall commence

at the time and date [his] . . . payroll earnings begin in

such classification . . . The shop employees were classi

fied according to their skills and job functions: Welder-

Mechanics (5), Mechanics (16), Helpers (9) and Porters (3).

On October 31, 1969, Defendant Motor Convoy posted a seniority

list which erroneously set forth the classification seniority

dates of nearly all shop employees as of October 13, 1969.

(P. Exh. 14, at 32) This list was protested by employees;

it was some six months before Local 528's business represent

ative, C. P. Cook, managed to get the various seniority list

ing problems worked out to everyone's satisfaction. (Tr. II,

197) Thereafter, all shop employees were credited with their

proper classification seniority (i.e., the date each employee

began work in his classification). (Tr. II, 196)

Plaintiff Melvin Freeman was originally classified

as a helper. Claiming he should have been classified as a

mechanic, he complained to Local 528 which obtained his re

classification as a mechanic at the lower steps of the griev

ance procedure. (Tr. I, 54; II, 193-195) Freeman was unhappy

at being assigned a classification seniority date of January

3, 1970, and he filed a grievance protesting such date. (U.

Exh. 6) This grievance was processed to a Joint Committee

-24-

hearing, with the result that Freeman was awarded a seniority

date of October 13, 1967. (U. Exh. 7) Additional grievances

dealing with a back pay claim (unsuccessful) and a human

rights claim (successful) were processed by Local 528 on

Freeman's behalf. (U. Exhs. 8, 9, 10 & 11) Local 528 also

counseled Freeman after he admitted an inability to perform

line mechanical duties and asked to be returned to the task

of changing engines and obtained his reinstatement as a line

mechanic through conferences with the Employer. Similarly

Local 528 was successful in obtaining an earlier classifica

tion seniority date for Intervenor Spencer. (Tr. I, 111-112;

U. Exh. 12)

In June, 1970, the Garage Supplement of the Central

and Southern Conference Area Agreement was significantly a-

mended to eliminate the helper classification and reclassify

all former helpers as apprentices. (P. Exh. 37, Art. 79, §

4(e), at 153) This change resulted in the following shop em

ployment profile as of March, 1975:

Classification Black White Total

Welder-Mechanic 0 4 4Mechanic 1 12 13Advanced Apprentice Mechanic 0 0 0Apprentice Mechanic 7 3 10Porter 2 0 210 19 29

The importance of the 1970 amendments is that seven

-25-

black and three white employees immediately became eligible to

advance to the mechanic's classification through the so-called

"Advanced Apprentice Mechanic" route. Under Article 79, § 1,

nn. 2 & 3 of the Agreement, any individual who has actually

worked in the apprentice classification for two years (all

black employees except Freeman and the two porters)—' were

entitled to request in writing promotion to advanced appren

tice status paying 2Ojzf per hour less than mechanics. The sole

requirement is that they be minimally qualified for the job; an

opening or vacancy is not required. (Tr. II, 70-72; III, 98-

102) The qualification determination, if adverse to the appren

tice, can be processed through the grievance procedure to arbi

tration. (Tr. Ill, 149)

Thereafter, advanced apprentices advance at the rate

of five cents per hour each six months until the classification

and rate of journeyman mechanic is reached. This is an automa

tic procedure in which an employee's mechanical ability is not

again questioned after he becomes an advanced apprentice mechan

ic. (Tr. Ill, 98-102) A mechanically qualified employee, whe

ther an apprentice or a porter, may also use his company garage

seniority to bid directly into an opening in the mechanic's

— The 2 porters were Hugh Brooks and Sam Freeman; Brooks never

attempted to obtain promotion to an apprentice mechanic job,

while Freeman was given a trial period on the duties of that

classification, and stated that he could not perform them. (Tr. Ill, 102-103)

-26-

classification. (Tr. Ill, 152) The mechanic and welder-

mechanic classifications are considered highly skilled jobs

carrying a current pay rate of $6.60 and $6.70 per hour

straight time. (P. Exh. 19, Art. 83, § 1) In comparing the

skilled mechanic's job with the semi-skilled drivers' job,

it was estimated that a driver would have to work sixty to

seventy hours each week in order to earn what a mechanic is

paid for a forty hour week. (Tr. Ill, 147-148)

No black or white apprentice has ever requested

promotion to advanced status. (Tr. Ill, 99, 164) Nor did

any apprentice or porter bid on the single mechanic's vacan

cy that arose in November, 1970. To perform as an advanced

apprentice, an employee would have to acquire his own hand

tools. (Tr. I, 148) In .the event of layoff from the jour

neyman mechanic classification, a former apprentice would be

entitled to use his garage seniority to bump into the ap

prentice classification. (P. Exhs. 19, Art. 81, § 2(a); 37,

Art. 77, § 2(a).) Thus apprentices may utilize this proce

dure to advance to the mechanic classification without fear

of sacrificing their accrued seniority.

%

B. The Decision Below

The District Court held that the Plaintiff's sta

tistical evidence established "a prima facie case of past

discrimination in hiring and job assignment" with respect to

the class as a whole. This showing, the Court said, had not

-27-

been rebutted by Defendants. In particular, the Court con

cluded :

Defendants have discriminated against

black applicants for employment on ac

count of their race and defendants have

also discriminated against black em

ployees by assigning them to lower pay

ing, less desirable jobs, and by refusing

to recognize their equal right to pro

motional opportunities and on-the-job

training. [JA ]

Based on this conclusion, the Court held that the classifica

tion seniority provisions of the collective bargaining agree

ment locked black employees into inferior jobs, and thus per

petuated initial hiring and assignment discrimination. The

Unions and the Employer were held jointly and severally liable

for the continuing discriminatory effects of the seniority

system.

The lower Court held that the International Union

had been properly served under Ga. Code Ann. § 3-119, in that

service had been perfected by serving an official of Local

528. Since the Court concluded that the Plaintiffs had shown

a substantial connection between the International and the

seniority provisions in issue, it stated that maintenance of

the suit did "not offend 'traditional notions of fair play

and substantial justice.’" The basis on which the Interna

tional was found responsible for the alleged discriminatory

seniority provisions turned on its status rather than its

conduct:

This is a system wide case, governed by

system wide policies of discrimination.

-28-

But for the existence of the International

Union, these policies could not be effec

tively perpetuated by the existence of the

system wide seniority system. As a result,

this Court has concluded that the Interna

tional Union must be held liable for the

discriminatory effects of this seniority

system. [JA ]

The District Court made no finding of International involve

ment in negotiations of the Supplemental Agreement containing

the disputed seniority system; nor did it find that the Inter

national had approved such agreement. No findings of actual

International control over the negotiations were made. The

Court acknowledged the Local Union's effective control over

seniority arrangements but found this fact immaterial.

The Court defined the class to include all black em

ployees in the Southern Conference,—^ other than office or

supervisory personnel, and established the back pay recovery

period as commencing on February 12, 1968. It held, however,

that black applicants could not be represented by Plaintiffs.

Thereupon the Court entered an extensive injunction, providing

for, inter alia, transfer with seniority carryover between the

Garage, Shop and Yard divisions at the Employer's Atlanta ter

minal; transfer with seniority carry over to the Road division

at other Southern Conference terminals; promotion between clas

sifications within divisions with carryover seniority; and

training, recruitment, hiring and reporting provisions. The

6/ Former black employees who were terminated after August 16

1969, were also included in the class.

-29-

transfer rights of the injunction were conditioned upon the

existence of a "vacancy" which the Court redefined on Febru

ary 11, 1976, to include positions subject to the recall rights

of employees. (JA )

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. The plaintiffs and class members were not as

signed to shop jobs on the basis of race; they were assigned

at hire based on their qualifications and the availability of

vacancies. Evidence of statistical imbalance in the Employer's

Road department, attributable to the paucity of minority ap

plicants and circumscribed recruitment, is not probative of

the separate issue of assignment discrimination.

2. The class was not "locked into" shop jobs after

hire. Their was no evidence, other than perhaps statistical,

of pre-act transfer discrimination. In 1965, the Employer

expressly offered class members the opportunity to transfer

to the Road department; as unorganized employees without sen

ility rights, they would begin to accrue seniority for the

first time upon their entry into the bargaining unit. After

their organization in 1969, the class members rejected a local

rider seniority adjustment that would have permitted them to

exercise their new-found hire date seniority in the Road de

partment. Moreover, the Supplemental Agreement contained a

promotion procedure which, if utilized by the class members

would have led to their promotion to the lucrative mechanic

-30-

classification, the most prestigious hourly job available at

the Employer's facility.

3. On this record, the Union defendants should not

have been held jointly and severally liable for back pay, costs

and attorneys fees. So far as the District Court concluded

that the Unions, along with the Employer, discriminated in

hiring, job assignment, promotion and work training opportu

nities, its findings or conclusions were clearly erroneous.

The record is clear that the Union had no role whatever in

such personnel actions, except insofar as it remedied Em

ployer conduct adverse to Plaintiffs and class members through

the grievance procedure. Local 528 offered to obtain senior

ity adjustments to enable black employees to exercise their

full seniority on the road. It obtained and implemented an

automatic procedure for promotion to mechanic. If these ef

forts were frustrated by the class or the Employer, it is im

proper to hold the Union responsible therefor.

4. Plaintiffs' proof failed to show a substantial

connection between the International Union and the seniority

provisions at issue. The International neither negotiated nor

approved these provisions. Seniority is totally under the

control of Local Unions. The lower Court's finding that, but

for the International Union, there would be no Conference wide

agreement with discriminatory provisions is clearly erroneous.

Conference wide agreements had existed for twenty years before

the National Master Automobile Transporters Agreement came into

\

-31-

existence. Thus the lower Court erred in finding the Interna

tional responsible for the conduct of Local 528, an autonomous

labor organization, and in holding the International amenable

to suit in the forum State.

ARGUMENT

I. BLACK EMPLOYEES WERE NOT

ASSIGNED TO SHOP JOBS ON

THE BASIS OF THEIR RACE AND COLOR

This case does not arise in the freight industry and

does not involve the National Master Freight Agreement. It

presents issues arising out of different facts than the freight

, cases with which this Court is familiar. Motor convoy employs

no city drivers; all driving personnel are carried on a single

terminal seniority list. The employees in the alleged class

are shop personnel who were not hired to drive; who expressed

no interest in driving at hire; and who possessed no particular

qualifications at hire to suit them for employment as drivers.

Unlike the freight industry cases, the alleged class here is

not composed of black city drivers who wanted to drive and

exhibited sufficient ability at hire to cause the employer to

put them behind the wheel of a tractor-trailer. The importance

of this fact is that it bears on the weight to be accorded

Plaintiffs' statistical evidence in the ultimate determination

of whether minority employees were placed in particular jobs

because of their race.

-32-

j

]

,1

* -j■;

,i

i

1

■ ■'•■■A

■■ ;-:;i

i

■ ' . v " ^

■ ■ :-%i]

$

This Court has held that statistical evidence show

ing a significant disparity in the racial composition of city

and road units establishes a prima facie case of discrimina

tion. Rodriguez v. East Texas Motor Freight, 505 F.2d 40

(C.A. 5, 1974). In United States v. T.I.M.E.-D.C., 517 F.2d

299 (C.A. 5, 1975), this Court referred to "the decisive sig

nificance of flagrant statistical deviations" in the freight

industry. It is not our purpose or burden to challenge these

holdings here. For, on this record, we shoulder the burden

of going forward to demonstrate why "the apparent disparity

is not the real one," Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d

348, 358 (C.A. 5, 1972), at least in regard to the asserted

racially motivated job assignments in issue.

In this respect, it is worthy to note

that the establishment of a prima facie

case does not require a finding in favor

of the party establishing it; but only per

mits that finding. Wright v. Rockefeller,

372 U.S. 52, 57 (.1963). A risk on non

persuasion is yet on the plaintiff . . .

just as is a risk of non-persuasion on the

defendant if he does not rebut the prima

facie case . . . . So the court, in de-

termining whether a party has successfully

overcome the risk of non-persuasion, should

consider all of the statistical information

before it, as well as all the other evidence

bearing on the presence or absence of dis

crimination in employment. [Roman v. ESB,13 EPD 1[ 11,285 (C.A. 4, 1977) . ]

In this case, the racial imbalance in the Road depart

ment shown by Plaintiffs' statistics was attributable to a pau

city of minority applicants and overly restrictive recruitment

-33-

practices, such as reliance on "walk-ins" and "word of mouth"

advertising. (Tr. I, 17) Unlike the freight industry

cases, where minority drivers applied and were assigned to

°ity instead of road jobs, the racial imbalance in Motor Con

voy's Road department was attributable to the small number of

minority applicants for driver positions.-/ Thus Plaintiffs'

statistical evidence creates a much weaker inference of as

signment discrimination— the ultimate fact to be proved-/

than has been true in other cases before this Court. It fol

lows that Plaintiffs' risk of nonpersuasion is commensurately

greater.

In determining whether black employees were discrim-

inatorily assigned to shop jobs, it is obviously relevant whether

y Unlike Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 495 F.2d 398 (C.A. 5,

1974), rev'd on other grounds, 423 U.S. 814 (1976), the Plain-

here did not show that any individual black applicant for

a driving job was denied employment because of his race. (Tr II, 49-54; 54-60; III, 184-214)

8 /— _ The theory upon which restrictive seniority systems are

said to perpetuate the effects of past discrimination, first developed in Quarles v. Phillip Morris, 279 F. Supp. 505

iE:?*-Ya* 1968) and U.P.P. Local 189 v. United States, 416 F.2d 980 (C.A. 5, 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970),

requires a showing that minority employees were assigned or

placed in^inferior jobs and departments. See Pettway v.

American Cast Iron Pipe Co.. 494 F.2d 211, 218 (C.A. 5, 1974)

( until 1961 the Company formally maintained exclusively black

jobs and exclusively white jobs."); Johnson v. Goodyear Tire &

Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364, 1373 (C.A. 5, 1974) “ ("Once it has

been determined that blacks have been discriminatorily assigned

to a particular department within a plant, departmental sen

iority cannot be utilized to freeze those black employees into a discriminatory caste.")

-34-

the Employer acted on the basis of job-related attributes, or

whether race is the only identifiable factor explaining what

ever statistical disparities may exist. Roman v. ESB, supra,

13 EPD 1| 11,285, at 5934. Thus in United States v. Jackson

ville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418 (C.A. 5, 1971), cert, denied,

406 U.S. 906 (1972), this Court held, inter alia, that the

Government had failed to sustain its burden of proving that

Defendant Terminal had engaged in racially discriminatory job

assignments after July 2, 1965. Terminal officials testified

that they applied a "best qualified" standard exclusively;

they recounted how they were able to place experienced persons,

or those who had attained a certain educational level in par

ticular jobs, and generally the testimony revealed "that super

visory personnel believed they were assessing applicants' qual

ifications in terms of job-related attributes, not race, after

the Act's effective date." Id., at 445. Instead of attempting

to contradict this testimony, "the Government chose to stand on

statistics elucidating post-Act employment disparities." This

was not enough:

Once Terminal officials proffered jus

tifying explanations for their actions, the

Government should have shown that stated

policies and assignment realities did not

coincide after July 2, 1965. [Id., at 446.]

This aspect of Jacksonville Terminal throws into sharp

perspective the central issue in this case, that is, whether the

assignment of black applicants for employment to shop instead of

road jobs in the years prior to Title VII's effective date was

>t a.-.v jv - . . i.u 3 ■>- — u

-35-

discriminatory where such employees had no driving experience

or other qualifications suiting them for road employment. At

the trial, Company officials testified to their efforts to ob

tain the best qualified drivers (e.g., Tr. Ill, 185), and that

Motor Convoy never had a policy of barring blacks from road

jobs. (Tr. Ill, 136) It was stipulated that the Company pre

fers road drivers with prior driving experience (Tr. I, 16);

and exhibits introduced by the parties show only sixteen white

nd two black drivers without actual driving experience were

hired. (P. Exhs. 11 & 12) And of those sixteen white drivers,

many had some related experience with motor vehicles and con

struction equipment (e.g., P. Exh. 11), or in Raymond Hill's

case, with securing heavy equipment by means of chains and

other restraints (Tr. II, 96-97), suggestive of job-related

attributes.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals has stressed that

Plaintiffs in Title VII cases need not demonstrate that indi

vidual members of a certified class meet the criteria set forth

by the Supreme Court in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411

^ l 9/U.S. 792 (1973),- as part of their case-in-chief in order to

_/ '"phe complainant in a Title VII trial must carry the initial

burden under the statute of establishing a prima facie case of

racial discrimination. This may be done by showing (i) that he belongs to a racial minority; (ii) that he applied and was qual

ified for a job for which the employer was seeking applicants;(iii) that, despite his qualifications, he was rejected; and

(iv) that, after his rejection, the position remained open and

the employer continued to seek applicants from persons of com

plainant's qualifications." 411 U.S. at 802.

establish a prima facie case which must be met or explained

by defendants. Rodriguez v. East Texas Motor Freight, supra,

505 F.2d at 55. This holding does not mean, however, that

record evidence demonstrating that new employees were assigned

to jobs and departments consistent with the availability of

vacancies and their abilities can be disregarded. For it would

be anomalous to conclude that an employer has pursued a pattern

or practice of assignment discrimination against a class on a

record indicating, as here, that individuals within the class

were not discriminatorily assigned on the basis of race.

Thus in the instant case, it is clear that all but

four of the black shop employees in the alleged class were as

signed to the shop instead of the road department because Motor

Convoy was able to obtain experienced drivers for its road va

cancies during the years such shop employees were hired. Four

black shop employees were hired and assigned in 1954, 1955 and

1957, years in which three white drivers (J.A. Carter, H. D.

Hicks and W. C. Bates), without prior road experience were

hired. Carter and Bates acquired their familiarity with vehi

cles and motors by driving on a farm and working as a mechanic,

respectively. (C. Exhs. 15g & 15i)

More important, it does not appear that these three

. whites were hired and assigned to road vacancies that were

available at the times black employees Higgins, Brooks, Allen

and Glass were hired and assigned to the shop. Thus in the

intervening six months between the dates Higgins and Carter

-37-

were employed, Motor Convoy hired four experienced road drivers.

Similarly seven drivers with experience were employed, respec

tively, four of whom were hired after Allen but before Hicks.

Supra at pp. 10-11. Consequently it affirmatively appears that

Carter and Hicks were not hired for road vacancies for which

the employer was seeking applicants at the times Higgins, Brooks

and Allen were hired and assigned to shop jobs.— ^ The unavail-

ability of vacancies is fatal to an allegation of discrimination

in assignment in class actions, as well as in individual dis

crimination cases. See United States v. Georgia Power Co., 3

[CCH] EPD 1[ 8318, at 7089 (N.D. Ga. 1971) , aff'd in part, va

cated for consideration of other issues and remanded, 474 F.2d

906 (C.A. 5, 1973).

Defendant Unions submit that the foregoing evidence

constitutes a sufficient explanation of why black employees

were assigned to shop instead of road jobs at hire, and rebuts

any inference of assignment discrimination arising from Plain

tiffs' statistical evidence. This result is particularly ap

propriate here because, as distinguished from the freight in

dustry cases, the statistical profile of Motor Convoy's road

department furnishes an unreliable indicator of why alleged

class employees were assigned to shop jobs, and thus the Court

10/ T — In regard to J, D. Glass, it likewise appears that there

were no road vacancies available at the time he was hired on

v June 3, 1957. The next road vacancies were filled in late

August 1957, when 5 road drivers were hired, including W. C.

Bates.^ (P. Exh. 14, at 51-53) This fact, together with Glass'

^.mechanical training, suggests that his assignment to a shop job

assisting Plaintiff Freeman was a rational, "nondiscriminatory jpb action. \ J'V. TV\

A

-38-

should view such statistics with some skepticism. Instead of

resting on their statistics, therefore, Plaintiff and Inter-

venor were required to come forward with evidence that Motor

Convoy had driving vacancies at the time they were hired, or

at least within the period between the time they first sought

employment with the employer and their hire dates, and they

were equally or better qualified than the white drivers who

filled these vacancies. The failure of Plaintiff and Inter-

venor to carry their ultimate burden of proof requires a find

ing that members of the alleged class were not discriminatorily

assigned to shop jobs on the basis of their race or color.

II. BLACK SHOP EMPLOYEES WERE

NOT "LOCKED INTO" THE JOBS TO

WHICH THEY WERE ORIGINALLY

ASSIGNED PRIOR TO THE EFFECTIVE

DATE OF TITLE VII OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS

ACT OF 1964

It is well established that Title VII is not to be ap

plied retrospectively, and in order to establish a post-Act vio

lation, it must be shown that minority employees were "locked in

to" inferior jobs and departments after July 2, 1965, by overtly

discriminatory employment practices, or by practices, neutral on

their face, having the effect of unlawful discrimination. Griggs

v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971); U.P.P. Local 189 v. Uni

ted States, supra, 416 F.2d at 987. There was considerable tes

timony to the effect that black shop employees were entitled to

transfer to the Road department long before Local 528 became

their representative. In 1965, pursuant to direction by Motor

Convoy’s Board of Directors, company officials offered black

-39-

shop employees the opportunity to transfer to road jobs. (Tr.

Ill, 132) Those who transferred would begin to accumulate

competitive status seniority on the date they began as road

drivers.

This evidence refutes any allegation that Defendant

Motor Convoy maintained or applied a no-transfer policy after

July 2, 1965, the effective date of Title VII.— ^ The fact

that transferees would have started at the bottom of the road

seniority list cannot be considered an inhibition against trans

fer within the meaning of Title VII. Unorganized and other non

unit personnel, upon transfer to a bargaining unit job, always

begin to accrue seniority as of their date of transfer. There'

is nothing discriminatory or unlawful about this universal pro

cedure. See, e.g., Murray v. OCAW Local 8-472, 88 L.R.R.M. 2119

(D. Conn., 1974). Furthermore, seniority is solely a creature of

contract. Aeronautical Indus. Dist. Lodge 727 v. Campbell, 337

U.S. 521, 526 (1949). As unorganized employees not covered by

a contract, black garagemen had no seniority to lose by trans

ferring to road jobs. Indeed, they would gain legally cogniz

able seniority rights by such transfer.

In late 1969, as a result of designating Local 528

as their exclusive representative and the subsequent execution

of the Central and Southern Garage Supplement, shop employees

acquired seniority rights. The nature of these rights, however,

Compare Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra, 495 F.2d

at 411, where minority employees were told they could not transfer at all.

was not dictated in national or regional bargaining. Nor were

the seniority rights obtained for shop employees determined by

the majority choice of a predominately white group. It was

shown at trial that Local 528 held a meeting of shop employees,

properly advertised in advance, at which they voted on the

question whether to apply the classification seniority provi

sions of the Garage Supplement, or to negotiate a rider agree

ment with Motor Convoy providing for seniority carryover be

tween the Shop and Road departments. This meeting, attended

by twelve black and three white employees, resulted in a vote

in favor of adopting the Garage Supplement. Supra at pp. 21-

22 .

The testimony regarding this vote was in conflict.

Plaintiffs' witnesses stated that the only vote they recalled

dealt with seniority carryover between the Yard and Shop de

partments, a proposal defeated by the Yard employees, and that

they remembered no vote concerning a seniority merger with the

Road department. (Tr. IV, 29-53) The District Court thought

it unnecessary to resolve the conflict in testimony, incor

rectly viewing the evidence as being addressed to the Interna

tional Union responsibility issue. (JA )— / This was *

error. The evidence was highly material to the questions of

— ^ As noted in Part IV below, it is the exclusive authority

of Local Unions over seniority arrangements at individual terminals, not whether a particular vote was taken, that is im

portant in regard to International responsibility.

-41-

whether class employees were "locked into" shop jobs by the

Union, and whether the Union intentionally engaged in an un

lawful employment practice. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g).

The District Court relied on Rodriguez v. East Texas

Motor Freight, Inc., 505 F.2d at 51 and Sabala v. Western Gil

lette, Inc., 516 F.2d 1251 (C.A. 5, 1975), in concluding that

the vote of the shop employees constituted no defense for the

Union. In Rodriguez, this Court rejected a business necessity

defense based on a vote of Defendant Local 657's city drivers,

the majority of whom were minority persons, against a merger of

city and road seniority lists. This vote was taken two weeks

after the close of the trial, and the record did not disclose

"what assumptions were made implicit." Moreover, "the extent

to which the vote represent[ed] the actual preference of the

class . . . [was] unclear," 505 F.2d at 51, because Local 657's

membership was not "congruent" with the class alleged in the

Complaint. The Court also noted that seniority carryover from

the city to the road, without reciprocal rights for road dri-

13/vers, could have been allowed.—

Rodriguez presented a much different situation than

the instant case. Here virtually every member of the class

13/— The Sabala case provides no guidance in the instant case

whatever. There the defendant Local Union petitioned the Na

tional Freight Industry Negotiating Committee to merge the road and city seniority systems. On this ground, and because it did

not initiate or negotiate the contracts, the Local Union argued that it had not violated Title VII. This Court stated, "Given

the Local's informed decision to participate in the national bar

gaining negotiations despite discrimination, because of the tangi

ble economic benefits a national contract promised to its members

we find that argument unpersuasive." 516 F.2d at 1263.

-42-

voted. The vote itself was taken immediately upon organiza

tion of the Shop. It was neither superimposed upon years of

bargaining history nor taken in response to litigation. And

its assumptions, based on Local 528's carryover seniority ar

rangements with Complete Auto Transit, were explicit. Further

the shop employees involved were newly organized. They had no

established seniority rights to be protected by the preferen

tial transfer treatment suggested by this Court in Rodriguez.

Nor, in view of the inherent instability of road employment,

is it clear that shop employees would have been benefited by

a one-time transfer to the road, which would have precluded

their return to the shop. Finally the issue here is not whether

the vote precluded a remedy for past discrimination perpetuated

on business necessity grounds. For it is clear that, had carry

over seniority been authorized by the class in 1969, there would

be no alleged discriminatory seniority provisions to perpetuate

the challenged assignment discrimination found by the Court be

low. Thus the vote in this case relates to liability and not

to remedy. Rodriguez is not controlling.

We submit that Local 528 was entitled to rely on the

above-described vote of black shop employees in favor of divi

sional and classification seniority, and that it cannot be

found in violation of Title VII for implementing the wishes

of its black members.— ^ Cf. Thornton v. East Texas Motor

14/ ~Local 528 is quite conscious of the wishes of its black

members in that they comprise 40% of its total membership.(Tr. Ill, 9)

-43-

Freight Inc., 497 F.2d 416, 426 (C.A. 6, 1974). This choice

by a majority of black employees refutes the notion that they

were locked into shop jobs by action of their bargaining a-

gent.

Nor was road employment the only route to high-pay

ing, prestigious work at the Employer's facilities. The Cen

tral and Southern Garage Supplement covering, among others,

the Employer's Birmingham and Atlanta terminals contains an

automatic upgrading procedure whereby employees working at ap

prentice work for at least two years eventually become mechan

ics by requesting promotion to the advanced apprentice classi

fication in writing, and displaying their ability to perform

advanced apprentice work. Thereafter, their pay is increased

at six-month intervals until, two years after they became ad

vanced apprentices, they reach the pay rate and classification

of mechanic. No vacancy is required to advance under this

system, and an advanced apprentice's ability to perform as a

mechanic is not again questioned after his entry into the pro

gram. (P. Exhs. 19, Art. 83, § 1; 37, Art. 79, § 1) An em

ployee becoming a mechanic in this fashion is given seniority

credit in the mechanic classification for time spent as an

advanced apprentice. (Id., Art. 81, § 3(c))

No member of the alleged class sought advanced ap

prentice standing. (Tr. Ill, 99, 164) At trial, the Plain

tiffs urged that this advancement procedure was discriminatory

for two reasons: First, since advanced apprentices may not

-44-

work while mechanics are laid off under the contract (Art. 8,

§ 2(a)), Plaintiffs contended that white employees could bump

black employees with greater terminal seniority. Second,

Plaintiffs argued that promotion to advanced apprentice status

was in the sole discretion of white supervisory personnel, a

discretion not limited by objective qualification criteria.

The lower Court made no specific findings regarding the ad

vancement procedure. It did say in general terms that Defend