Federal Judge Warns Tennessee School Boards on Desegregation Stalling Tactics

Press Release

September 10, 1959

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Federal Judge Warns Tennessee School Boards on Desegregation Stalling Tactics, 1959. 246e3c81-bc92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a1bd0311-b5df-4c84-a45c-4ca73cf1f1ab/federal-judge-warns-tennessee-school-boards-on-desegregation-stalling-tactics. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

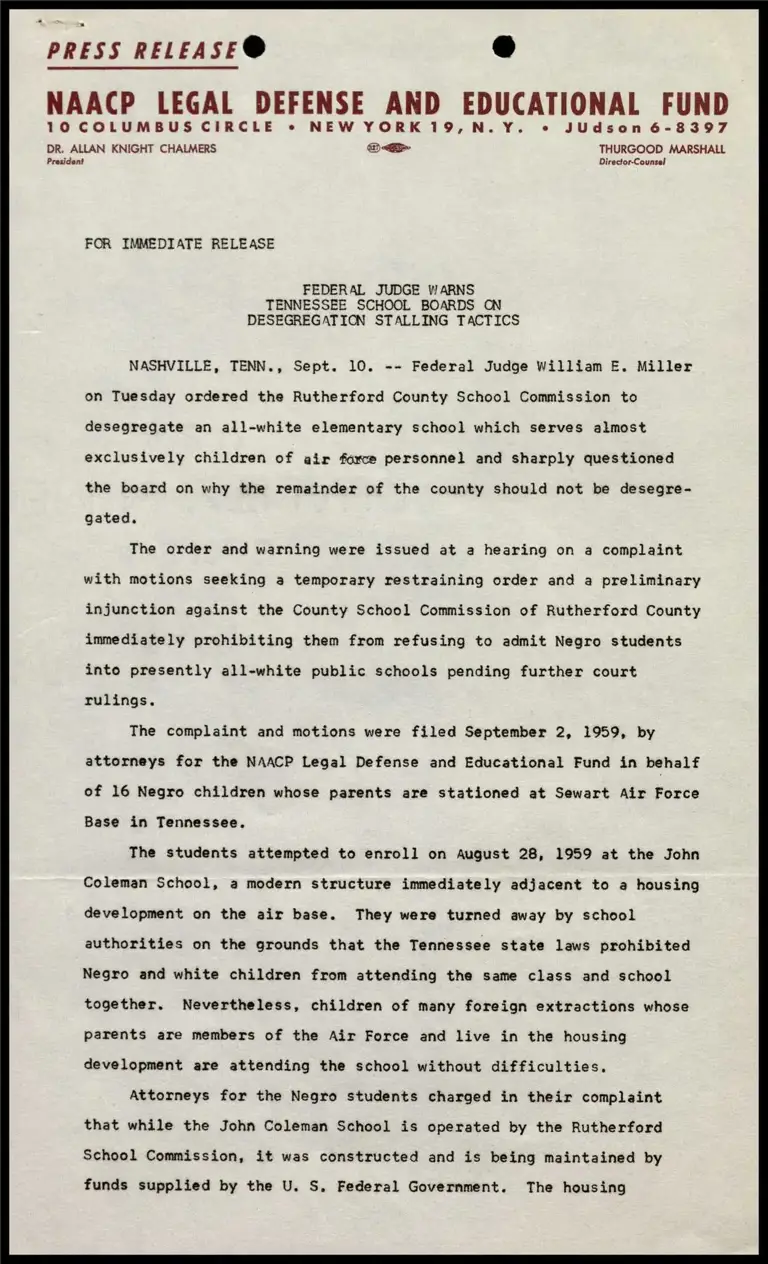

PRESS RELEASE® ®

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE + NEW YORK 19,N.Y. © JUdson 6-8397

DR. ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS QS THURGOOD MARSHALL

President Director-Counsel

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

FEDERAL JUDGE WARNS

TENNESSEE SCHOOL BOARDS ON

DESEGREGATION STALLING TACTICS

NASHVILLE, TENN., Sept. 10. -- Federal Judge William E. Miller

on Tuesday ordered the Rutherford County School Commission to

desegregate an all-white elementary school which serves almost

exclusively children of air force personnel and sharply questioned

the board on why the remainder of the county should not be desegre-

gated.

The order and warning were issued at a hearing on a complaint

with motions seeking a temporary restraining order and a preliminary

injunction against the County School Commission of Rutherford County

immediately prohibiting them from refusing to admit Negro students

into presently all-white public schools pending further court

rulings.

The complaint and motions were filed September 2, 1959, by

attorneys for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund in behalf

of 16 Negro children whose parents are stationed at Sewart Air Force

Base in Tennessee.

The students attempted to enroll on August 28, 1959 at the John

Coleman School, a modern structure immediately adjacent to a housing

development on the air base. They were turned away by school

authorities on the grounds that the Tennessee state laws prohibited

Negro and white children from attending the same class and school

together. Nevertheless, children of many foreign extractions whose

parents are members of the Air Force and live in the housing

development are attending the school without difficulties.

Attorneys for the Negro students charged in their complaint

that while the John Coleman School is operated by the Rutherford

School Commission, it was constructed and is being maintained by

funds supplied by the U. S, Federal Government. The housing

26

development, known as the Wherry Housing Development, is

located on government property and built with federal aid.

The attorneys also charged that the school was built and

designed primarily, if not exclusively, to provide an adequate ele-

mentary school education for children in the housing development,

However, Negro children who live in the development, as well as

those residing in the surrounding areas, are herded into crowded

buses and forced to travel 14 to 16 miles daily to attend an all-

Negro school in Murfreeboro,

The attorneys termed this segregated arrangement an “unneces-

sary burden imposed upon their parents solely because of their race

and color." It subjects the children to "unwarranted physical and

health hazards", deprives them of "opportunities for atheletic and

cultural development", and reduces their "opportunities for educa-

tional instructions and study", the attorneys claimed.

NAACP Legal Defense attorneys for the Negro children are

Z. Alexander Looby and Avon M, Williams, Jr. of Nashville, Thurgood

Marshall and Jack Greenberg of New York.

=90S<