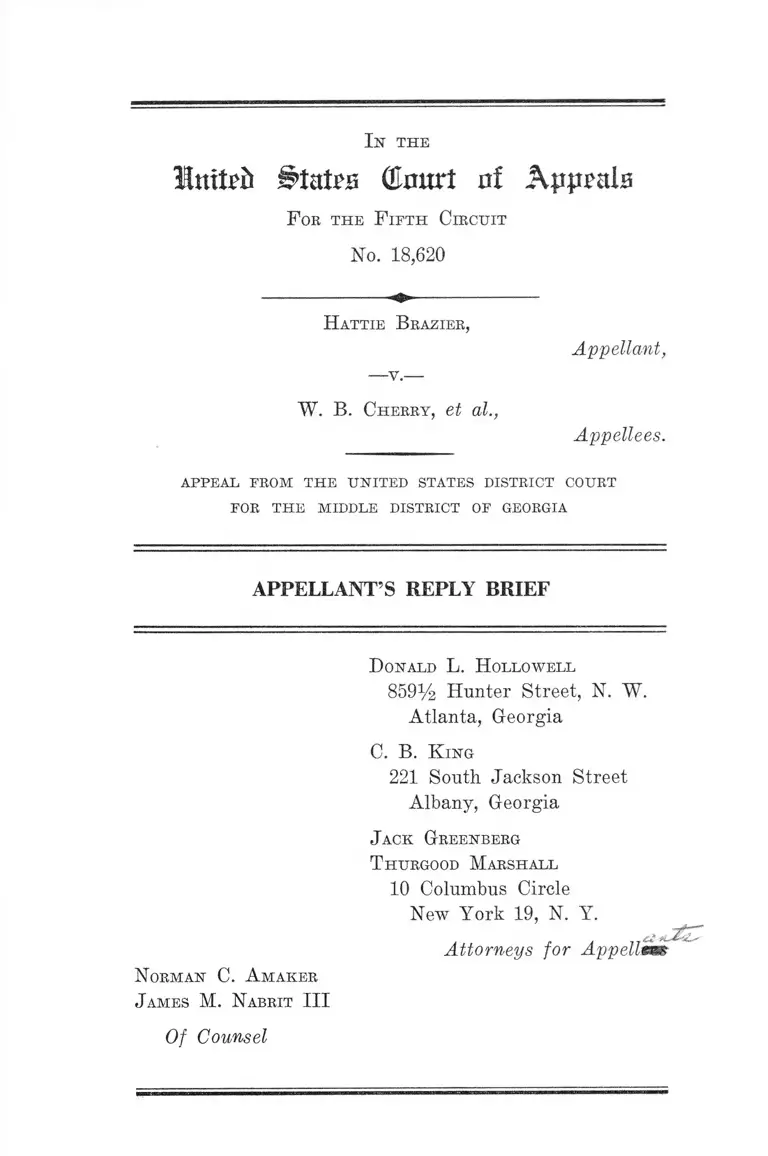

Brazier v. Cherry Appellant's Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

May 19, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brazier v. Cherry Appellant's Reply Brief, 1961. b7121a51-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a1f40035-2e52-4aa7-aa50-f62289b1ce2c/brazier-v-cherry-appellants-reply-brief. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

In t h e

Intteft i ’tatHi tourt irl Apprals

F ob t h e F i f t h C ir c u it

No. 18,620

H a t t ie B r a z ie r ,

Appellant,

W . B . C h e r r y , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

APPELLANT’S REPLY BRIEF

N o r m a n C . A m a k e r

J a m e s M . N a b r it III

D o n a l d L. I I o l l o w e l l

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

C . B . K in g

221 South Jackson Street

Albany, Georgia

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

T h u r g o o d M a r s h a l l

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellees

Of Counsel

I N D E X

A r g u m e n t

I—Lately Decided Cases.............................................. 1

II—“ There Is No Federal General Common Law” 5

III— Legislative History ............................................. 8

IV— Relief Against the Bonding Company........... 15

Conclusion........................................................................... 17

Table of Cases

Avelone v. St. John’s Hospital, 165 Ohio State 467, 135

N. E. 2d 410 (1956) ...................................................... 8

Bing v. Thunig, 2 N. Y. 2d 656,143 N. E. 2d 3 (1957) .... 8

Citizens Bank of Colquitt v. American Surety Company

of New York, 174 Ga. 852 ........................... ............ . 16

Clearfield Trust Co. v. United States, 318 U. S. 363 ....... 6

Collins v. Hardyman, 341 U. S. 651.................................. 8

Cox v. Roth, 348 U. S. 207 .................................................. 7

D’Oench Duhme & Co. v. Federal Deposit Ins. Corp.,

315 U. S. 447....... ...................... ....................................... 6

Dyer v. Kazuliesa Abe, D. C. Hawaii, 138 F. Supp. 220 3

Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U. S. 6 4 ...............3, 5, 7

Francis v. Crafts, 203 F. 2d 809 ................................ ..... 9

Francis v. Lyman, 108 F. Supp. 884 ........ ...................... 8

Francis v. Southern Pacific Co., 333 U. S. 445 (1948) .... 6

PAGE

11

Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496 ...................................... 8

Hargrove v. Town of Cocoa Beach, 96 So. 2d 130 (Fla.

1957) .... ......... ........ ....... .......... ................................. ..... 8

The Harrisburg v. Rickards, 119 H. S. 199, 30 L. Ed.

358 (1886) ................................................................. ....... 5

Jackson County v. United States, 308 U. S. 343 .......... . 6

Jefferson v. Hartley, 81 Ga. 716...................................... 16

Just v. Chambers, 312 U. S. 383 ...................................... 4

McPherson v. Buick Motor Co., 217 N. Y. 382, 111 N. E.

1050 (1916) ................ ............. ...................................... 8

Molitor v. Kan eland Community Unit District No. 302,

18 111. 2d 11, 163 N. E. 2d 89 (1959) .......................... 8

Monroe v. Pape,------ U. S .------- , 5 L. Ed. 2d 492 ........... 1, 9

Panama R. Co. v. Rock, 266 U. S. 209, 69 L. Ed. 250

(1924) ...... ........... ............................................................. 5

Powell v. Fidelity and Deposit Company of Maryland,

45 Ga. App. 8 8 ....................... ......................................... 16

Pritchard v. Smith, 29 U. S. L. Week 2534 (8th Cir.,

May 16, 1961) ............ ..................................................... 2,7

Smith v. Glen Falls Indemnity Co., 71 Ga. App. 697 .... 16

Van Beeck v. Sabine Towing Co., 300 U. S. 342 ........... 4

Walker v. Whittle, 83 Ga. App. 445..... ............................. 16

S t a t u t e s

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 25, §a (l) ......... . 4

42 U. S. C. §1981...................................................... . 13

42 U. S. C. §1983 ......................................................... 2, 3

PAGE

Ill

42 U. S. C. §1985(3) ......................... ........................ 9

42 U. S. C. §1986 .......................................................... 9

42 U. S. C. §1988 .................................. 3, 6,13,14,15,16

Cong. Globe, 39tli Congress, 1st Session, App. pp.

315-16................................ ...................... ................ . 12

Cong. Globe, 39th Congress, 1st Session, p. 474 ....14,15

Cong. Globe, 41st Congress, Session II, App. p. 662 13

Cong. Globe, 42nd Congress, 1st Session ............... 8

Act of April 9, 1866 ..................................................12,14

Act of May 31, 1870, §16..... .................................... 13,14

Georgia Code Ann., §89-418...................................... 15

O t h e b A u t h o b it y

PAGE

13 NACCA L. J. 188,189 7

In t h e

luitrfc Butts (Eimrt nf Appeals

F ob t h e F i f t h C ir c u it

No. 18,620

H a t t ie B r a z ie r ,

-v.—

Appellant,

W. B. C h e r r y , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

APPELLANT’S REPLY BRIEF

I

Lately Decided Cases

At the outset appellant respectfully calls the Court’s at

tention to two lately decided cases, so recent that they

could not be incorporated in appellant’s brief:

1. Monroe v. Pape, ------ U. S. ------ , 5 L. ed. 2d 492.

Monroe v. Pape confirms appellant’s assertion in the prin

cipal brief that if decedent had merely been beaten and

not killed there would have been a cause of action in the

federal courts. (Brief, pp. 5-6). The complaint there al

leged that police officers broke into petitioners’ home,

abused them, destroyed property, took one of the peti

tioners to the police station where he was detained on

open charges for ten hours, failed to take him before a

magistrate and finally released him, all without a search

2

or arrest warrant. Respondents had acted under color of

the statutes, ordinances, regulations, customs and usages

of the State of Illinois, City of Chicago. The Supreme

Court had before it the question of whether petitioner

stated a cause of action under 42 U. S. C., Section 1983

5 L. ed. 2d at 495, note 2. The Court held that a cause of

action was stated. The opinion contains a lengthy canvass

of the legislative history. Among the conclusions which

the Court drew from this history were:

“ The debates are long and extensive. It is abun

dantly clear that one reason the legislation was passed

was to afford a federal right in federal courts because

by reason of prejudice, passion, neglect, intolerance

or otherwise, state laws might not be enforced and

the claim of citizens to the enjoyment of rights,

privileges, and immunity guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment might be denied by the state

agencies.” 5 L. ed. 2d at 501.

# # #

“ Although the legislation was enacted because of

the conditions that existed in the South at that time,

it is cast in general language and is as applicable to

Illinois as is it to the States whose names were men

tioned over and again in the debates. It is no answer

that the State has a law which if enforced would give

relief. The federal remedy is supplementary to the

State and the state remedy need not be first sought

and refused before the federal one is invoked. Hence

the fact that Illinois by its constitution and laws out

laws searches and seizures is no barrier to the present

suit in the federal court.” 5 L. ed. 2d at 502-503.

2. The other case is Pritchard v. Smith, 29 U. S. L. Week

2534, May 16, 1961, decided by the Court of Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit, April 26, 1961. That case involved

3

precisely the question at issue here: Does a cause of

action under the Civil Rights Act survive? The Court of

Appeals for the Eighth Circuit held that it does, relying

chiefly upon 42 IT. S. C. §1988. The excerpts contained

in U. S. Law Week appropriately may be quoted in full:

“ This action is brought under R. S. 1979, 42 U. S. C.

1983.

[Text] “ ‘We fully agree with the trial court’s con

clusion that this is an action arising under federal

statute and that consequently federal law governs.

In such a situation, the rule of Erie v. Tompkins,

304 U. S. 64, does not apply.’ ”

“ In cases arising under federal law, federal courts

have in some instances determined the rights of the

parties upon the basis of state law.

“ Under the provisions of R. S. 722, 42 U. S. C. 1988,

“ ‘The jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters con

ferred on the district courts by the provisions of this

chapter * * * for the protection of all persons in the

United States in their civil rights, and for their vin

dication, shall be exercised and enforced in conformity

with the laws of the United States, so far as such

laws are suitable to carry the same into effect; but

in all cases where they are not adapted to the object,

or are deficient in the provisions necessary to furnish

suitable remedies,’ ” the law of the state wherein the

court having jurisdiction of such civil or criminal

case is held shall govern.

“ This statute, so far as it pertains to civil actions,

has had little judicial attention. Dyer v. Kazuhesa

Abe, D. C. Hawaii, 138 F. Supp. 220, reversed on

other grounds, 256 F. 2d 728, states summarily with

out explanation that the statute relates to procedure,

not jurisdiction.

4

“ ‘We cannot accept the view that Section 1988 is

procedural only. The substitution procedure is spe

cifically prescribed in FRCP 25. Section a (l) thereof

makes the substitution procedure available only in

situations where the cause of action is not extinguished

by death.

“ It appears that Congress by its language in Section

1988 intended to enlarge the civil right remedy where

the state law is not inconsistent with the laws of the

United States.

“ Since no federal statute specifically deals with the

substantive issue of survival, in the situation here

presented no inconsistency results from the applica

tion of Arkansas’ survival law, which permits survival

of tort suits except libel and slander. It is readily

apparent from Just v. Chambers, 312 U. S. 383; Van

Beeck v. Sabine Towing Co., 300 U. S. 342; and Cox

v. Roth, 348 U. S. 207, that the Supreme Court did

not consider the granting of the right of survival as

being inconsistent with any federal law or policy.

Each of said cases shows a strong trend to construe

statutes liberally to allow the survival of tort actions.

[Text] “ ‘Moreover, if we have given Section 1988

a broader interpretation than it is entitled to, wre be

lieve that the cases heretofore cited would justify

the conclusion that this is the type of a situation

where a court would be entitled to look to state law

to determine the survival issue. There appears to be

no well defined or established federal common law as

to the survival of tort actions for the vindication of

personal rights.’ ”—Van Oosterhout, J.1

1 The District Court opinion apparently is unreported. Appellant is in

formed, however, that Lauderdale v. Smith, 186 i\ Supp. 958 (E. D. Ark.

1960) is a companion case.

5

“There Is No Federal General Common Law”

Appellees’ brief and the decision of the Court below rest

entirely on the proposition that under the common law no

cause of action arises for the death of a human being:

“ It is settled that at common law no private cause of

action arises from the death of a human being . . . The

right of action, both in this country and in England,

depends wholly upon statutory authority.” Panama

B. Co. v. Rock, 266 U. S. 209, 69 L. Ed. 250 (1924).

“ ‘It is a singular fact that by the common law the

greatest injury which one man can inflict on another,

the taking of his life, is without a private remedy.’ ”

The Harrisburg v. Rickards, 119 U. S. 199, 30 L. Ed.

358 (1886) (E. p. 29).

Or, as the argument in appellees’ brief asserts:

“ It is a general rule of the common law that no action

will lie to recover damages for the death of a human

being occasioned by the negligent, or other wrongful,

act of another, however close may be the relation be

tween the deceased and the plaintiff and however

clearly the death may involve pecuniary loss to a plain

tiff.” (Brief of Appellees, p. 7.)

The underlying fallacy of this position with respect to a

cause of action asserted under a federal statute in the

federal courts is that, to quote Mr. Justice Brandeis in

Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U. S. 64, 78 (1938)

“There is no federal general common law.” (Emphasis

supplied.)

With respect to causes of action arising under federal

statutes the federal courts regularly must declare federal

II

6

judge made rules appropriate to the problems with which

they are concerned in the manner in which courts, from time

immemorial, have ascertained and pronounced law. See,

e.g., Clearfield Trust Co. v. United States, 318 TJ. S. 363

(1943); Francis v. Southern Pacific Co., 333 U. S. 445

(1948). This is not a federal general common law, but a

body of federal law appropriate to particular problems and

areas of jurisprudence. “ The concrete problem is to deter

mine materials out of which the judicial rule . . . should

be formulated.” Jackson County v. United States, 308 U. S.

343, 350. These materials, as Mr. Justice Jackson wrote in

D’Oench Duhme & Co. v. Federal Deposit Ins. Corp., 315

U. S. 447, 465, 470, are “ found in the Federal Constitution,

statutes, or common law. Federal common law implements

the Federal Constitution and statutes, and is conditioned

by them. Within these limits, Federal courts are free to

apply the traditional common-law technique of decision and

to draw upon all the sources of the common law in cases

such as the present.”

This is a far cry from embracing an ancient English rule

and being bound by it inexorably.

What are the “materials out of which the judicial rule”

in this case may be fashioned!

1. The civil rights statutes and the policy they seek to

effect.

2. Indications in Federal law of sources to which Con

gress and the courts desire reference to be made.

a. Foremost among these is 42 U. S. C. A. §1988,2 which,

as our principal brief indicates, has been developed specifi

2 Appellee’s brief suggests that 42 U. S. C. {1988 was not specifically

enumerated in the complaint and therefore, apparently, is not before the

Court (Br. pp. 5-6). But Rule 8, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure states

that “ a pleading . . . shall contain (1) a short and plain statement of the

7

cally for a situation such as that now at bar. It instructs

the courts that where federal law leaves a verbal hiatus in

the Civil Eights Acts, state law should bridge the gap.

“ [I]n all cases where they [the Civil Eights Acts] are not

adapted to the object, or are deficient in the provision neces

sary to furnish suitable remedies and punish offenses

against law, the common law as modified and changed by

the Constitution and statutes of the State wherein the

court having jurisdiction . . . shall be extended to and

govern... .” See Pritchard v. Smith, supra.

State law, as indicated in our principal brief, recognizes

survival and wrongful death as “ suitable remedies” in a

case such as this.

b. Erie R.R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U. S. 64. Although the

instant suit is a non-diversity case and the Erie rule cer

tainly has no independent force here, where state law is

corroborative of federal policy an additional reason surely

exists for following federal policy.

3. The general common law. This, appellees assert,

militates against finding that a cause of action has been

stated. But the common law policy which appellees proffer

to this Court has been repudiated by every common law

jurisdiction. While it may have been the common law

centuries ago, appellants respectfully submit, along with

Dean Eoscoe Pound, see 13 NACCA L. J. 188, 189, and

Cox v. Roth, 348 U. S. 207, 210, that it no longer may be

viewed as the common law. It is not unusual for the courts

grounds upon which the court’s jurisdiction depends . . . ” As Patten v.

Dennis, 134 F. 2d 137, 138 (9th Cir. 1943) held:

“ The requirements of a complaint may be stated, in different words,

as being a statement of facts showing (1) the jurisdiction o f the

court . . . ”

See also Bitchie v. Atlantic Defining Co., 7 F. B. D. 671 (D. N. J. 1947).

The instant complaint obviously asserts such facts.

8

which, after all, created common law rules, to change them

when they are demonstrably inappropriate to changed con

ditions, social and moral views. Thus, has the law of negli

gence in the absence of privity, been changed by the courts.

E.g., McPherson v. Buick Motor Co., 217 N. Y. 382, 111 N. E.

1050 (1916). Likewise has the rule of sovereign immunity

been overturned. Molitor v. Kaneland Community Unit

District, No. 302, 18 111. 2d 11, 163 N. E. 2d 89 (1959);

Hargrove v. Town of Cocoa Beach, 96 So. 2d 130 (Fla.

1957). Similarly has the rule of charitable immunity been

altered. Bing v. Thunig, 2 N. Y. 2d 656, 143 N. E. 2d 3

(1957); Avelone v. St. John’s Hospital, 165 Ohio St. 467, 135

N. E. 2d 410 (1956).

These examples could be multiplied. But even if the

repudiated rule which holds that there is no cause of action

for death were to be recognized as still viable, it is not at

all binding upon this Court, but merely one of several from

which it may choose. Under the circumstances of this case,

with federal law pointing in exactly the opposite direction,

such a choice would be singularly inappropriate.

Ill

Legislative History

Moreover, the legislative history clearly demonstrates

that there is a federal cause of action for the taking of this

life.

The Act of April 20, 1871 had a single unswerving pur

pose: to provide a remedy under Federal law for all per

sons deprived of the protections due to them as citizens

of the United States by virtue of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. See Congressional Globe, 42 Cong., 1st Session

passim. Hague v. C. I. O., 307 U. S. 496, 509-510. Collins

v. Hardyman, 341 U. S. 651, 661, Francis v. Lyman, 108

9

F. Supp. 884, aff’d sub nom. Francis v. Crafts, 203 F. 2d

809; cert. den. 346 U. S. 835. And see particularly Monroe

v. Pape, supra. The sections of the Act were designed to

operate as an integrated plan for the protection of all

such persons. Particularly §§6 (42 U. S. C. 1986) and 2

(42 TJ. S. C. 1985) (3), must be read in pari materia. Sec

tion 6 refers to acts proscribed in §23 in such a way as to

dispel any doubt that the remedy granted was not intended

to dissolve with death. The sections deal with two separate

wrongs: the wrong of action amounting to conspiracy (§2)

and of inaction, or neglect or refusal to act (§6).

Representative Poland, a member of the second Joint

House Senate Conference Committee which proposed the

substitute for the Sherman Amendment which subsequently

became Section 6 of the Act, in reporting the consensus

of the Conference Committee, said that the House had

decided that Congress had no Constitutional power to im

pose any obligations upon county and town organizations

as would have been done if the Sherman Amendment had

been enacted into law. He then continued

3 “ See. 6. That any person or persons, having knowledge that any of

the wrongs conspired to he done and mentioned in the second section of

this act are about to be committed, and having power to prevent or aid in

preventing the ' same, shall neglect or refuse so to do, and such wrongful

act shall be committed, such person or persons shall be liable to the person

injured, or his legal representatives, for all damages caused by any such

wrongful act which such first-named person or persons by reasonable diligence

could have prevented; and such damages may be recovered in an action on

the case in the proper circuit court of the United States, and any number

of persons guilty of such wrongful neglect or refusal may be joined as

defendants in such action: Provided, That such action shall be commenced

within one year after such cause of action shall have accrued; and if the

death of any person shall be caused by any such wrongful act and neglect,

the legal representatives of such deceased person shall have such action

therefor, and may recover not exceeding five thousand dollars damages therein,

for the benefit of the widow of such deceased person, if any there be, or if

there be no widow, for the benefit of the next of kin of such deceased person.”

(Emphasis added.)

1 0

At the same time . . . there was a disposition on the

part of the House, in onr judgment, to reach every

body who was connected either directly or indirectly,

positively or negatively, with the commission of any

of these offenses and wrongs, and we would go as far

as they chose to go in punishment or imposing any

liability upon any man who shall fail to do his duty

in relation to the suppression of those wrongs. The

result was this Section which we have reported in

lieu of the Sherman Amendment.

(Congressional Globe, Ibid., pg. 804) (emphasis sup

plied).

Representative Shellabarger, who managed the bill in

the House of Representatives also indicated the reach of

§6 when he said on the floor of the House,

Now note, the Sherman proposition does not go to

any other wrong than those of riots. This [referring

to Section 6] reaches every class of wrongs and is

much broader in its reach. (Id.)

The remarks of Senator Edmunds who sponsored the

legislation in the Senate are also indicative of the intend

ment of this Section:

Every citizen in the vicinity where any such out

rages as are mentioned in the Second Section of this

bill, which I need not now describe, are likely to be

perpetrated, he having knowledge of any such inten

tion or organization, is made a peace officer, and it is

made his bounden duty as a citizen of the United

States to render positive and affirmative assistance in

protecting the life and property of his fellow citizens

in that neigborhood against unlawful aggression; and

if, having this knowledge and having power to assist

by any reasonable means in preventing it or putting

11

it down or resisting it, he fails to do so he makes

himself an accessory or rather a principal in the out

rage itself . . .”

(Cong. Globe, Ibid., p. 820.)

Thus the purpose of §6 was to bring within the scope

of the remedy provided under the Act every class of

wrongdoer responsible in any way for the commission of

the wrongful acts proscribed in §2. However, respecting

those persons injured by the wrongful acts detailed in §2,

just one remedy was provided. And that remedy was given

in express terms to the legal representative for the benefit

of the widow4 in the event of the death of the injured

party, leaving no doubt that the language of §6 in Mr.

Shellabarger’s terms was intended to “ operate back” upon

§ 2.

The first appearance of the idea of allowing a cause of

action to survive the death of the injured party occurred

in the amendment offered by Senator Sherman of Ohio.

The substitute for the Sherman Amendment, eventually

agreed to by both houses, carried over the idea of sur

vival. Whatever the reason, it is clear that Congress did

intend to change the common law rule and was fully aware

that it was doing so. It did not include the language of

survival in §2 because, apparently, it felt that there could

be no doubt that its remedy of §6 was identical to the

remedy specified in §2.

4 Mr. Butler: “Let us see what remedy you give in a ease like that of

Dickinson, who was shot in Georgia.”

A Member: “ No, in Florida.”

Mr. Butler: “ Yes, in Florida, not in Georgia. I beg Georgia’s pardon.

What is the remedy in that case? His wife is to go down there and sue.

Whom is she to sue? She is to find out first who did the deed; then who

knew it was to be done and did not tell o f or aid in preventing it.”

(Remarks of Senator Butler of Massachusetts. Cong. Globe, Ibid., p. 807)

12

The language of Representative Shellabarger quoted at

page 7-8 of appellant’s original brief is unquestionably

the clearest statement of congressional intent respecting

the scope of the remedy created by §6: “ I think this

Amendment will give a right of recovery in all cases,

either under the Second Section or under this Section

where death ensues.”

Appellees argue that Mr. Shellabarger was uncertain

as to whether his interpretation of the Amendment, which

is now codified as 42 U. S. C., 1986, would be sustained by

the courts rather than by the legislature. Mr. Shellabarger

was speaking as a legislator to his “ fellow members” in

the Congress; he was urging the adoption of legislation.

His views were indeed supported by the acceptance of the

Second Conference Committee report. He was in fact

“ sustained” by his “ fellow members” in the Congress.

The legislative history of §1988 demonstrates its role in

a coordinated legislative scheme which points to recovery

in this suit. §1988 was originally enacted as a means of

enforcing substantive rights created concurrently as part

of a single legislative scheme designed “ to protect all

persons in the United States in their Civil Rights and

furnish the means of their vindication.” (Act of April 9,

1866. Congressional Globe, 39th Congress, 1st Session,

Appendix, p. 315.) The purpose of this statute—a purpose

shared by all of the so-called Civil Rights Acts—was to

declare the rights of Negroes and to furnish “ suitable

remedies” for their protection. The declaration or “ crea

tion” of substantive rights was contained in Section 1 of

the Act of 18665 * which in conjunction with Section 16 of

5 Chap. X X X I.—An Act to protect all persons in the United States in

their civil rights, and furnish the means of their vindication.

“ Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the

United States of America in Congress assembled, That all persons born

in the United States and not subject to any foreign power, excluding

Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States;

and such citizens, of every race and color, without regard to any previous

13

the Act of May 31, 18706 (an act which re-enacted in §18

thereof the Act of 1866) is the present 42 U. S. C. §1981.

§1988 of the Code was originally §3 of the Act of 18667 and

condition of slavery or involuntary servitude, except as a punishment

for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall have

the same right, in every state and territory in the United States, to make

and enforce contracts, to sue, he parties, and give evidence, to inherit,

purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and

to full and equal benefit o f all laws and proceedings for the security of

person and property, as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject

to like punishment, pains, and penalties, and to none other, any law,

statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, to the contrary notwithstanding.”

(Congressional Globe, 39th Congress, Session I, App. pp. 315-16. Em

phasis supplied.)

6 “ Sec. 16. And be it further enacted, that all persons within the juris

diction of the United States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory in the United States to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and pro

ceedings for the security of person and property as is enjoyed by white

citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes,

licenses and exactions of every kind, and none other, any law, statute, ordi

nance, regulation, or custom to the contrary notwithstanding. No tax or

charge shall be imposed or enforced by any State upon any person im

migrating thereto from a foreign country which is not equally imposed and

enforced upon every person immigrating to such State from any other

foreign country; and any law of any State in conflict with this provision

is hereby declared null and void.”

(Congressional Globe, 41st Congress, Session II, App. p. 662. Emphasis

supplied.) A comparison of the italicized language of this Section with the

italicized language of See. 1 of the Act of 1866, Note 3, supra, reveals their

close identity.

7 “ See. 3. And be it further enacted, That the district courts of the

United States, within their respective districts, shall have, exclusively of

the courts of the several States, cognizance of all crimes and offenses com

mitted against the provisions of this act, and also, concurrently with the

circuit courts of the United States, of all causes, civil and criminal, affecting

persons who are denied or cannot enforce in the courts or judicial tribunals

of the State or locality where they may be any of the rights secured to

them by the first section of this act; and if any suit or prosecution, civil or

criminal, has been or shall be commenced in any State court, against any

such person, for any cause whatsoever, or against any officer, civil or military,

or other person, for any arrest or imprisonment, trespasses, or wrongs done

or committed by virtue or under color o f authority derived from this act

or the act establishing a Bureau for the Belief of Freedmen and Befugees,

and all acts amendatory thereof, or for refusing to do any act upon the

14

was enacted to provide “ the necessary machinery to give

effect to what are declared to be the rights of all persons

in the first section” (Sen. Trumbull, Chairman of the Senate

Comm, on the Judiciary in his introduction of the bill on

the Senate floor. Cong. Globe, 39th Congress, 1st Sess.,

p. 474). Among the rights so declared in Section 1 of the

Act (and again in §16 of the Act of May 31, 1870 which

provided for the enforcement of Section 16 according to

the provisions of the Act of April 9, 1866) was the right

“ to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings

for the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by

white citizens . . . ”

Because of the essential nexus between these two Civil

Bights Acts, §1988 of 42 U. S. C. is a provision designed

to enforce the equal rights under law secured by 1981 and

as such, its enforcement provisions, which lodge jurisdic

tion with the federal courts and which provide for reference

to state laws as a means of exercising that jurisdiction

whenever federal law is “not adapted to the object” or is

“ deficient” are provisions which do in fact relate to sub

stantive federal rights created by Congress. Congress in

ground that it would be inconsistent with this act, such defendant shall

have the right to remove such cause for trial to the proper district or circuit

court in the manner prescribed by the ‘act relating to habeas corpus and

regulating judicial proceedings in certain eases,’ approved March three,

eighteen hundred and sixty-three, and all acts amendatory thereof. The

jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters hereby conferred on the district

and circuit courts of the United States shall be exercised and enforced in

conformity with the laws of the United States, so far as such laws are

suitable to carry the same into effect; but in all cases where such laws are

not adapted to the object, or are deficient in the provisions necessary to fur

nish suitable remedies and punish offenses against law, the common law, as

modified and changed by the constitution and statutes of the State wherein

the court having jurisdiction of the cause, civil or criminal, is held, so far

as the same is not inconsistent with the Constitution and laws of the United

States, shall be extended to and govern said courts in the trial and disposi

tion of such cause, and, if of a criminal nature, in the infliction of punish

ment on the party found guilty.”

15

tended the federal courts in every instance in which it

purported to exercise the jurisdiction conferred by §3 of

the Act of 1866 (§1988) to first look to federal law to see

if the case is provided for therein, to see if that law grants

a remedy; if not, then resort to the applicable state law

must be made.

“ There is very little importance in the general declaration

of abstract truths and principles unless they can be carried

into effect, unless the persons who are to be affected by

them have some means of availing themselves of their

benefits.” (Sen. Trumbull, Cong. Globe, 39th Congress,

1st Session, p. 474.)

IV

Relief Against the Bonding Company

Appellant has a remedy against the bonding company

for the wrongful acts of the Sheriff under Georgia law by

virtue of the provisions of 42 U. S. C. §1988. The court be

low dismissed appellant’s complaint against the defendant

bonding company holding that diversity jurisdiction was

lacking and that even if there were complete diversity as

between appellant and appellees, the jurisdictional amount

requirement in diversity actions was not met.

However, as demonstrated above, pursuant to 42 U. S. C.

§1988, appellant has a remedy under “ the common law, as

modified and changed by the Constitution and Statutes”

of Georgia for the violation of federally protected rights.

Consequently, the court below had civil rights jurisdiction

over the claim against the bonding company without refer

ence to the amount of the surety’s liability on the bond.

Under Georgia law, there is no question of the surety’s

liability for the wrongful acts of the Sheriff. Georgia Code

Ann. §89-418 provides as follows:

16

Conditions of liability—Every official bond executed

under this Code is obligatory on the principal and

sureties thereon—

* * # # #

4. For the use and benefit of every person who is

injured, either by any wrongful act committed under

color of his office or by his failure to perform, or by

the improper or neglectful performance of those duties

imposed by law.

That section of the Georgia Code has been construed by

the highest court of the State to fix liability upon a surety

upon a sheriff’s official bond for damages resulting from an

illegal homicide by the sheriff committed while acting under

color of office. Smith v. Glen Falls Indemnity Co., 71 Ga.

App. 697. To the same effect is Powell v. Fidelity and De

posit Company of Maryland, 45 Ga. App. 88. The Supreme

Court of Georgia has held that preliminary recovery against

the sheriff for his wrongful acts is not a prerequisite to suit

against the surety on the bond, Jefferson v. Hartley, 81 Ga.

716, and the surety may be sued jointly with the wrongdoer.

Walker v. Whittle, 83 Ga. App. 445. The surety is charge

able with knowledge of the law and is held to have executed

official bonds with reference thereto. Citizens Bank of Col

quitt v. American Surety Company of New York, 174 Ga.

852.

Clearly then, appellant here has a remedy under the

laws of Georgia against the defendant bonding company

and under 42 U. S. C. §1988, these laws “ shall be extended

to and govern the [federal] courts in the trial and dis

position of the cause” at bar.

17

CONCLUSION

W h e r e f o r e , for the reasons given above, appellant

respectfully prays that the judgment of the Court below

be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

D o n a l d L. H o l l o w e l l

8591/2 Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

C. B. K in g

221 South Jackson Street

Albany, Georgia

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

T htjrgood M a r s h a l l

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellees

N o r m a n C. A m a k e r

J a m e s M. N a b r it III

Of Counsel

18

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that on the 19th day of May, 1961, I

served copies of this brief on Charles J. Bloch, Esq. and

Ellsworth Hall, Jr., Esq. by mailing same to them by air

mail prepaid addressed to their offices at 520 First Na

tional Bank Building, Macon, Georgia.

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

38