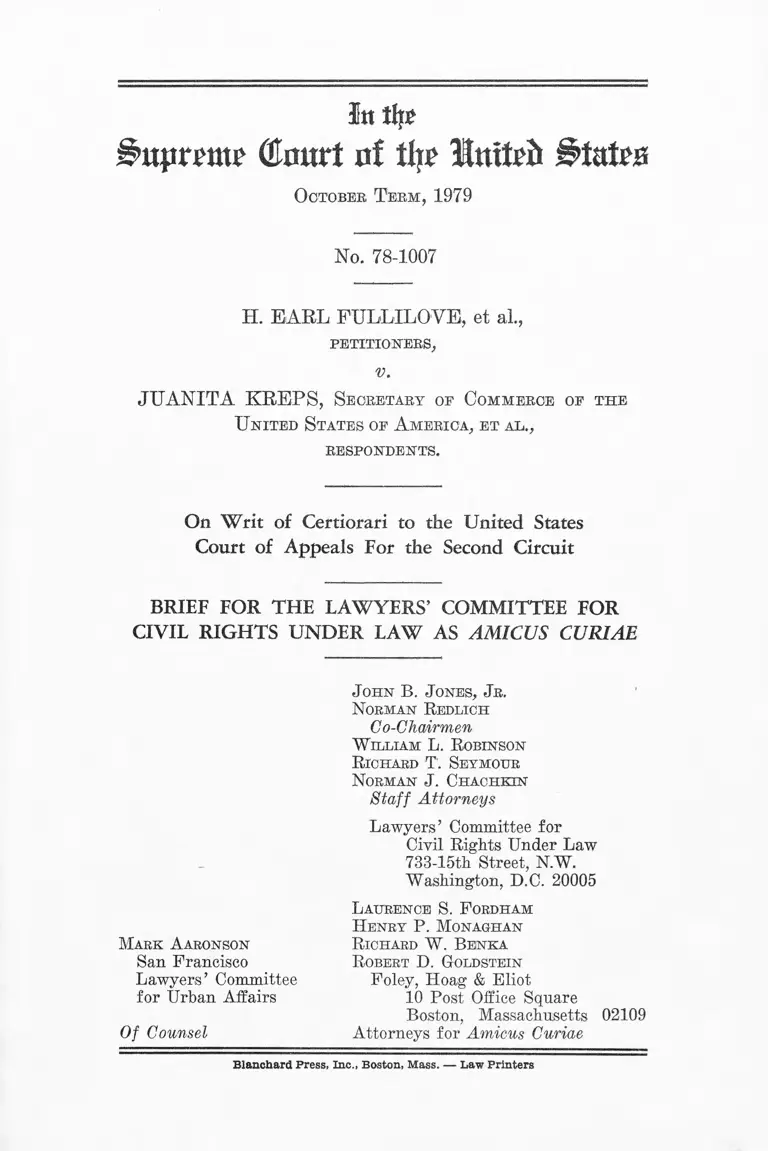

Fullilove v. Kreps Brief for the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Fullilove v. Kreps Brief for the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law as Amicus Curiae, 1979. 69be6b78-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a1fe5e12-110a-4d8e-8034-3d5ed143e8ee/fullilove-v-kreps-brief-for-the-lawyers-committee-for-civil-rights-under-law-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme (Emtrt nf tlje llwteit States

October T eem , 1979

No. 78-1007

H. EARL FULLILOVE, et al.,

PE T ITIO N ER S,

V.

JUANITA KREPS, S ecretary of Commerce of the

U nited S tates of A merica, et al.,

R ESPONDENTS.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals For the Second Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

Mark Aaeonson

San Francisco

Lawyers’ Committee

for Urban Affairs

Of Counsel

J ohn B. J ones, J r.

Norman Redlich

Co-Chairmen

W illiam L. Robinson

Richard T. Seymour

Norman J . Chachkin

Staff Attorneys

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

733-15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Laurence S. F ordham

H enry P. Monaghan

R ichard W. Benka

Robert D. Goldstein

Foley, Hoag & Eliot

10 Post Office Square

Boston, Massachusetts 02109

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

Blanchard Press, Inc., Boston, Mass. — Law Printers

INDEX

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.................. V

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE............. 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE................. 4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT................... 8

ARGUMENT............................. 10

I. ONLY THE POWER OF CONGRESS TO

REMEDY PAST AND PRESENT DISCRIM

INATION BY MEANS OF A CIRCUM

SCRIBED MINORITY SET-ASIDE

PROVISION IS AT ISSUE...........10

II. CONGRESS EXERCISED ITS POWER

ONLY AFTER LONG AND DETAILED

INVESTIGATION, DEBATE AND

REMEDIAL EXPERIMENTATION,

DURING WHICH IT HAD FOUND

THAT WIDESPREAD DISCRIMINA

TION AGAINST MINORITIES

EXISTED IN THE CONSTRUCTION

INDUSTRY AND IN THE LETTING

OF GOVERNMENT CONTRACTS, AND

THAT THE SET-ASIDE PROVISION

WOULD ENHANCE THE WELL-BEING

OF THE ECONOMY..................12

A. The Floor Debates On The

1977 MBE Provision Cap-

sulized The Facts Which

Justified Its Passage......12

I

B. It Is Appropriate To Look

To Prior Legislative In

quiries And Acts Of

Congress, And To Consider

All The Evidence Available

To Congress, In Reviewing

The 1977 MBE Provision.....19

1. In amending and

enforcing the Small

Business Act, Congress

and the Executive

have made studies of

minority businesses,

the discrimination

they have suffered,

and the effectiveness

of various remedial

strategies............27

2. In enforcing fifth

and fourteenth amend

ment prohibitions,

Congress has found

widespread discrimina

tion in the distribu

tion of federal funds

by state and local

governments and wide

spread discrimina

tion by construction

industry recipients

of federal funds,

and it has reviewed

and accepted the use

of race-sensitive

goals as a remedy for

that discrimination....56

II

(a) Discrimination

in state and

local use of

federal revenue

sharing funds....56

(b) Discrimination

in the con

struction in

dustry...........61

(c) Discrimination

in letting rail

road construc

tion contracts....65

C. Congress Recognized That,

Because Of Racial Discrim

ination In The Construc

tion Industry, The 1977

MBE Provision Significantly

Advanced The Racially

Neutral Anti-recessionary

Purposes Of The Public

Works Employment Acts Of

1976 and 1977..............69

III. ACTING ON THE BASIS OF THIS

HISTORY, CONGRESS WAS CLOTHED

WITH ABUNDANT CONSTITUTIONAL

AUTHORITY, UNDER ITS SPENDING

POWER, UNDER ITS THIRTEENTH

AMENDMENT §2 POWER, AND UNDER

ITS FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT §5

POWER, TO ENACT THE 1977 MBE

PROVISION.......................76

III

IV. THE 1977 MBE PROVISION DOES

NOT VIOLATE THE DUE PROCESS

CLAUSE OF THE FIFTH AMENDMENT___85

CONCLUSION...........................99

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Araya v. McLelland, 525 F.2d 1194

(5th Cir. 1976)..................... 85n.

Bulova Watch Co. v. United States,

365 U.S. 753 (1961)................. 85n.

Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 U.S. 715 (1961)........ 81

Califano v. Webster, 430 U.S. 313

(1977)............................... 78

Charles C. Steward Machine Co. v.

Davis, 301 U.S. 548 (1937)........77,78

Contractors Association of Eastern

Pa. v. Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d

159 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S.

854 (1971)........................... 62

First National Bank of Boston v.

Bellotti, 435 U.S. 765 (1978).......lln.

Fullilove v. Kreps, 47 U.S.L.W. 3760

(May 21, 1979)........................ 7

Fullilove v. Kreps, 584 F.2d 600

(2d. Cir. 1978).................... 7,92

Fullilove v. Kreps, 443 F. Supp 253

(S.D.N.Y. 1977)...................7,63n.

Geduldig v. Aiello, 417 U.S. 484

(1974)......................... 93

General Electric Co. v. Gilbert,

429 U.S. 125 (1976)..... 93

Gilmore v. City of Montgomery,

417 U.S. 556 (1974)...................81

Helvering v. Davis, 301 U.S. 619

(1937)............................ 77,78

International Union of Electrical,

Radio and Machine Workers v.

N.L.R.B., 289 F.2d 757 (D.C.Cir.

I960)...............................85n.

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392

U.S. 409 (1969)............... .82,83,84

Katzenbach v. McLung, 379 U.S. 294

(1964)......................... . .23,87n.

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641

(1966)....................2In. ,24,79,80

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413

U.S. 189 (1973).....................58n.

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974)...79

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535

(1974).........................84n. ,85n.

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112

(1970)............21n. ,23,79,80,87n. ,91

VI

Perkins v. Lukens Steel Co., 310 U.S.

113 (1940)..........................77n.

Posadas v. National City Bank,

296 U.S. 497 (1936).................85n.

Rhode Island Chapter, Associated

General Contractors v. Kreps,

450 F. Supp. 338 (D.R.I.

1978)........................64n. ,81,82

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160

(1976)............................... 83

Securities and Exchange Comm'n

v. Chenery Corp., 318 U.S. 80

(1943)............................... 23

South Carolina v. Katzenbach,

383 U.S. 301 (1966).........20,21n.,87n.

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey,

430 U.S. 144 (1977)..................87n.

United States v. Georgia Power Co.,

474 F .2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973)..........89n.

United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745

(1966)............................... 81

United States v. Price, 383 U.S.787

(1966)............................... 81

United Steelworkers v. Weber, 99

S.Ct. 2721 (1979).........63n. ,88,91,92

VII

Universal Interpretative Shuttle

Corp. v. Washington Metropolitan

Area Transit Commission, 393 U.S.

186 (1968)......................... 85n.

University of California

Regents v. Bakke, 438 U.S.

265 (1978)...11,57,63n.,86,90n.,92,98n.

Wood v. United States, 41 U.S.(16 Pet.)

342 (1842)......................... 85n.

Constitution and Statutes

U.S. Constitution

article I, §8, cl.l............ 77

article I, §8, cl.3............84n.

thirteenth amendment §2....78,80,82,

83,86n.,94n.

fourteenth amendment §5....78,79,80,

81,86n.,94n.

5 U.S.C. §§553(c), 557(c)(3)(A).....23n.

Small Business Act, and amendments,

15 U.S.C. §§631 et seq...26,28,29-31,37n.,

49-56 and passim

Act of October 27, 1972, Pub. L.

No. 92-595, 86 Stat. 1314 (codified

at 15 U.S.C. §681(d)), and amend

ment................................37n.

5731 U.S.C. §1221 et seq

31 U.S.C. §1242......

VIII

58

42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1982...............83

Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000d

et seq........................ 7,57,85n.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000e et se^....62

Economic Opportunity Amendments of

1967, Pub. L. No. 90-222, title II,

81 Stat. 710 (codified at 42 U.S.C.

§§2901 et seq.)...................31-32

Public Works Employment Act

of 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-369,

title I, July 22, 1976, 90 Stat.

999 (codified at 42 U.S.C.

§§6701 et seq.)............4 and passim

Public Works Employment Act of

1977, Pub. L. No. 95-28, title

I, May 13, 1977, 91 Stat.

116........................4 and passim

Railroad Revitalization and

Regulatory Reform Act of 1976,

45 U.S.C. §803, 49 U.S.C. §1657a.....66

Executive Orders and Regulations

Executive Order 11246, 3CFR,

1964-1965 Comp. p. 339...............62

Executive Order 11458, 3 CFR,

1966-1970 Comp., p. 779 (March

1969)...............................33n.

IX

Executive Order 11518, 3 CFR, 1966-

1970 Comp., p. 907 (March 1970)..34n.,35

Executive Order 11625, 3 CFR, 1971-

1975 Comp., p. 616 (Oct. 1971)......34n

35 Fed. Reg. 17833 (Nov. 20, 1970)

(codified at 13 CFR §124.8-1)........36

36 Fed. Reg. 17509 (Sept. 1, 1971)

(codified at 41 CFR §§1-1.1303,

1.1310)..............................36

42 Fed. Reg. 4286 (Jan. 24, 1977)

(codified at 49 CFR Part 265)........66

44 Fed. Reg. 30673 (May 29, 1979)....95n

49 CFR §265.13(c)(3) (vi).............66

49 CFR §265.19(a) (2).................67

Legislative Materials

H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, 92d Cong.,

1st Sess., reprinted in 2 Subcomm.

on Labor of Senate Comm, on Labor

and Public Welfare, 92d Cong., 2d

Sess., Legislative History of the

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972 at 77 (Comm. Print 1972).......58n

Minority Enterprise and Allied

Problems of Small Business,

H.R. Rep. No. 94-468, 94th

Cong., 1st Sess. (Sept.

1975)............34n. ,38,39,40,41,43,44

X

Effects of New York City's Fiscal

Crisis on Small Business, H.R. Rep.

No. 94-659, 94th Cong., 1st Sess.

(Nov. 1975).............. . . .44n. ,75,87n.

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1077, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1976), reprinted in

[1976] U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

1746............................5,69,70

Summary of Activities, A Report by

the House Committee on Small

Business, H.R. Rep. No. 94-1791,

94th Cong., 2d Sess. (Jan. 3,

1977)..........................44n. ,45n.

H.R. Rep. No. 95-20, 95th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1977), reprinted in

[1977] U.S. Code Cong. & Ad'. News

150.................................70n.

H.R. Rep. No. 95-230, 95th Cong.,

1st Sess., reprinted in [1977]

U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 168........7

H. Conf. Rep. No. 95-1714, 95th

Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted in

[1978] U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

3879...........................52n. ,53n.

Hearings on Civil Rights Aspects

of General Revenue Sharing Before

the Subcomm. on Civil and Consti

tutional Rights of the House Comm,

on the Judiciary, 94th Cong., 1st

Sess., ser. 21 (1975)..........58,59,60

XI

Subcomm, on Civil and Constitutional

Rights of the House Comm, on the

Judiciary, 94th Cong., 1st Sess.

(Comm. Print Nov. 1975)........61n. ,87n

Summary of Activities of the

Comm, on Small Business, House

of Representatives, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. (Comm. Print Nov. 1976)....46

S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92d Cong., 1st

Sess. (1971), reprinted in 2 Subcomm.

on Labor of Senate Comm, on Labor

and Public Welfare, 92d Cong., 2d

Sess., Legislative History of the

Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972 at 418 (Comm. Print 1972)....58n

S. Rep. No. 94-499, 94th Cong., 2d

Sess., reprinted in [1976] U.S.

Code Cong. & Ad. News 14.............66

S. Rep. No. 95-1070, 95th Cong.,

2d Sess., reprinted in [1978]

U.S.Code Cong. & Ad. News

3835...............35n. ,37n. ,50,53n. ,54

Hearings on the Philadelphia Plan

and S931 Before the Subcomm. on

Separation of Powers of the Senate

Judiciary Comm., 91st Cong., 1st

Sess. (1969)........................63n

Hearings on Small Business Adminis

tration 8(a) Contract Procurement

Program Before the Senate Select

Comm, on Small Business, 94th

Cong., 2d Sess. (Jan. 21,

1976)..................... 47,48,75,87n.

XII

Special Joint Session Hearings

on Purchase and Revitalization

of Northeast Corridor Properties

(Amtrak), Before the Senate Corrans.

on Appropriations, Budget and

Commerce, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1976)............................67,68

Hearings on H.R. 7557, Department

of Transportation and Related

Agencies Appropriations for Fiscal

Year 1978, Part IV, Before the

Subcomm, of the Senate Comm, on

Appropriations, 95th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1977)........................ 68n.

Senate Select Comm, on Small

Business, 95th Cong., 1st Sess.,

Report on Small Business Adminis

tration 8(a) Contract Procurement

Program (Comm. Print Feb. 16,

1977)......................... 48,49,87n.

7C /V

123 Cong. Rec. H1436-40 (daily ed.

Feb. 24, 1977)....6,13,14,15,16,20n.,74,

97 and passim

123 Cong. Rec. S3909-10 (daily ed.

March 10, 1977)...6,18,19,20n.,72,74,75

and passim

Executive Branch Publications

U.S. Bureau of Census, Special

Report, Minority-Owned Businesses,

1972 Survey of Minority-Owned

Business Enterprises, MB72-4,

(May 1975)......................28n. ,73

XIII

U.S. Bureau of Census, Statis

tical Abstract of the United

States: 1978........................ 74

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights,

Report, The Federal Civil Rights

Enforcement Effort - 1974, Vol. IV,

To Provide Fiscal Assistance (Feb.

1975).............................59,60

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights,

Report, Minorities and Women as

Government Contractors (May

1975)...........20n. ,28n. ,41n. ,42n. ,43n.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights,

The Federal Civil Rights Enforce

ment Effort - 1974, Vol. VI, To

Extend Federal Financial Assis

tance (Nov. 1975)...................60n.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, The

Unfinished Business, Twenty Years

Later...A report submitted to the

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights by

its Fifty-one State Advisory

Committees (Sept. 1977).............87n.

Comptroller General of the U.S.,

Questionable Effectiveness of

the 8(a) Procurement Program,

GGD-75-57 (April 1975)..............41n.

Comptroller General of the U.S.,

Report, Department of Defense

Program To Help Minority-run

Businesses Get Subcontracts Not

Working Well (Feb. 28, 1977)........45n.

XIV

Department of Housing and Urban

Development, A Survey of Minority

Construction Contractors............64n

Department of Labor, Bureau of

Labor Statistics, Consumer

Expenditure Survey Series, Report

455-4, Consumer Expenditure Survey

Series, Interview Survey (1977).....71n

Executive Office of the President

and Office of Management and

Budget, Interagency Report on

the Federal Minority Business

Development Programs (March

1976)...........................65n. ,73

Report of the National Advisory

Commission on Civil Disorders

(March 1, 1968)...................32,33

Office of Minority Business

Enterprise, Minority Business

Opportunity Committee Handbook

(Aug. 1976)...................64n.,65n.

Books and Articles

A. Andreasen, Inner City Business:

A Case Study of Buffalo, New York

(1971).............................. 73n

C. Black, Structure and Relationship

in Constitutional Law (1969)......... 23

J. Chamberlain, Legislative Processes,

National and State (1936)............ 25

XV

Cox, The Supreme Court, 1965 Term--

Foreward: Constitutional Adjudica

tion and the Promotion of Human

Rights, 80 Harv. L. Rev. 91

(1966).... 21,24

Cox, The Role of Congress in Con

stitutional Determinations, 40

U. Cin. L. Rev. 199 (1971)............ 24

K. Davis, Administrative Law Treatise

(1958; 1970 Supp .).................. 23n

The Federalist Nos. 52, 57............26

R. Glover, Minority Enterprise in

Construction (1977)................. 73n

B. Gross, The Legislative Struggle

(1953)............................... 24

Linde, Book Review, 66 Yale L. J.

973 (1957)........................ 24,25

H. Linde & G. Bunn, Legislative and

Administrative Processes (1976)........26

Sandalow, Racial Preferences in

Higher Education: Political

Responsibility and the Judicial

Role, 42 U. Chi. L. Rev. 653

(1975)............................... 26

Comment, The Philadelphia Plan: A

Study in the Dynamics of Executive

Power, 39 U. Chi. L. Rev. 723

(1972).............................. 63n

XVI

Miscellaneous

Brief for the American Civil Liber

ties Union and the Society of

American Law Teachers Board of

Governors, Amici Curiae, United

Steelworkers v. Weber............... 63n

Brief for the Lawyers' Committee

for Civil Rights Under Law as

Amicus Curiae, United Steelworkers

v. Weber............................ 63n

Brief of the NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc., as

Amicus Curiae, University of

California Regents v. Bakke.......... 84

Supplemental Brief for the United

States as Amicus Curiae, University

of California Regents v. Bakke.......63n

XVII

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers' Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law was organized in 1963

at the request of President John F.

Kennedy to involve private attorneys

throughout the country in the national

effort to assure civil rights to all

Americans. The Committee's membership

today includes former Attorneys General,

past Presidents of the American Bar

Association, a number of law school

deans, and many of the nation's leading

lawyers. Through its national office in

Washington, D.C., and its offices in

Jackson, Mississippi, and eight other

cities, the Lawyers' Committee over the

past sixteen years has enlisted the

services of over a thousand members of

the private bar in addressing the legal

problems of minorities and the poor in

education, employment, voting, housing,

municipal services, access to government

services, the administration of justice,

and law enforcement.

* The parties' letters of consent to the

filing of this brief are being filed with the

clerk pursuant to Sup. Ct. Rule 42(2).

The Lawyers' Committee and its

local committees, affiliates, including

the San Francisco Lawyers' Committee for

Urban Affairs, and volunteer lawyers

have been actively engaged in providing

legal representation to those seeking

relief from private and public discri

mination. In this case, Congress itself

has come to grips with the effects of

such discrimination, manifested by

insignificant minority business enterprise

(hereinafter at times "MBE") participa

tion in federally funded construction

work, by setting aside for MBE's ten

percent of the funds allocated to one

short-term federal program. The Lawyers'

Committee, over the years, has strongly

endorsed vigorous action by the executive

and legislative branches to remedy

discrimination and its effects. We

believe that the MBE set-aside at issue

in this case was a reasonable congres

sional response to the historic exclusion

of MBE's from federally funded construction

contracts, and we believe it important

for this Court to affirm the power of

Congress to respond as it did to this

discrimination.

-2-

The Lawyers' Committee has previously

addressed the issue of race-conscious

affirmative action programs in its

amicus briefs in Defunis v. Odegaard,

416 U.S. 312 (1974), University of

California Regents v. Bakke, 438 U.S.

265 (1978), and United Steelworkers v.

Weber, 99 S.Ct. 2721 (1979). Because

the issues presented by this case are

vitally important to the realization of

the goal of equal opportunity for minori

ties, and to the power of Congress to

deal with discrimination against minorities,

the Committee files this brief amicus

curiae for the assistance of the Court.

-3-

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Section 42 U.S.C. §6705(f)(2)-/

established a 10 percent set-aside for

minority businesses in funds allocated

pursuant to the Public Works Employment

Act of 1977, Pub. L. No. 95-28, title I,

May 13, 1977, 91 Stat. 116 (hereinafter

"1977 PWEA"), amending Public Works

Employment Act of 1976, Pub. L. No.

94-369, title I, July 22, 1976, 90 Stat.

999 (hereinafter "1976 PWEA"). These

anti-recessionary Acts funded the con

struction of public buildings and other

1/ The 1977 MBE provision reads:

Except to the extent that the Secretary

determines otherwise, no grant shall be

made under this chapter for any local

public works project unless the applicant

gives satisfactory assurance to the Secre

tary that at least 10 per centum of the

amount of each grant shall be expended for

minority business enterprises. For pur

poses of this paragraph, the term "minority

business enterprise" means a business at

least 50 per centum of which is owned by

minority group members or, in case of a

publicly owned business, at least 51 per

centum of the stock of which is owned by

minority group members. For the purposes of

the preceding sentence, minority group

members are citizens of the United States

who are Negroes, Spanish-speaking, Orientals,

Indians, Eskimos, and Aleuts. 42 U.S.C.

§6705(f)(2) (1976 & Supp. I 1977).

-4-

public works on the basis of grant

applications submitted by state and

local governments, in order to stimulate

the economy through public spending and

alleviate unemployment, particularly in

the hard-pressed construction industry,

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1077, 94th Cong., 2d

Sess. 1-2 (1976), reprinted in [1976]

U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 1746, 1746-47.

The challenged provision (hereinafter

at times "1977 MBE provision") mandated

the Secretary of Commerce, unless she

determined otherwise, to require from

government recipients of these funds

satisfactory assurance that 10 percent

of each public works grant would be

spent for minority business enterprises.

MBE1s were defined as businesses at

least 50 percent of which were owned (or

publicly owned businesses the stock of

which was at least 51 percent owned) by

United States citizens who were Negroes,

Spanish-speaking, Orientals, Indians,

Eskimos or Aleuts.

This provision was one of several

refinements in the funding requirements

-5-

which Congress made when, in the 1977

PWEA, it extended the 1976 PWEA public

works program for another year and added

an additional 4 billion dollars in

program funding to the 2 billion dollars

originally authorized.

Versions of the 1977 MBE provision

were introduced as floor amendments to

the 1977 PWEA by Congressman Parren

Mitchell of Maryland in the House of

Representatives, 123 Cong. Rec. H1436

(daily ed. Feb. 24, 1977), and by Senator

Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, and

others, in the Senate, 123 Cong. Rec.

S3909-10 (daily ed. March 10, 1977).

After debate, versions of the MBE provi

sion were accepted by both Houses.

The House version included a clari

fying amendment offered by Representative

Roe, 123 Cong. Rec. H1438 (daily ed.

Feb. 24, 1977), which established that

the 10 percent requirement was to be

waived where the unavailability of MBE's

made the 10 percent requirement infeasible.

The Conference Report adopted the House

version, emphasizing that "[t]his provision

shall be dependent on the availability

of minority business enterprises located

-6-

in the project area." H.R. Rep. No.

95-230, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. 11,

reprinted in [1977] U.S. Code Cong. &

Ad. News 168, 170. The 1977 PWEA, as

amended, was enacted into law on May 13,

1977.

Petitioners brought suit for declara

tory and injunctive relief in the United

States District Court for the Southern

District of New York on November 30,

1977, on the grounds that the 1977 MBE

provision employed a racial classification

in violation of the fifth and fourteenth

amendments of the United States Constitution

and of various statutes, including Title

VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. §§2000d et se^. (1976). The

district court consolidated for hearing

petitioners' motion for a preliminary

injunction and the trial on the merits,

and held that hearing on December 2,

1977. The court found the 1977 MBE

provision constitutional and therefore

dismissed the complaint. 443 F. Supp.

253 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 19, 1977). The court

of appeals affirmed on the merits. 584

F.2d 600 (2d Cir. 1978). This Court

granted certiorari on May 21, 1979. 47

U.S.L.W. 3760.

-7-

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

In enacting the 1977 MBE provision,

Congress built on foundations it had laid

over a period of decades, and the provision

cannot be fairly considered in isolation

from those foundations. In the course of

its oversight of various government pro

grams, including the Small Business Act,

federal revenue-sharing, federal assistance

to construction projects, and the Railroad

Revitalization and Regulatory Reform

Act, Congress had been fully informed of

conditions which justified the 1977 MBE

provision. For Congress had learned of

the existence of discrimination against

minorities in the construction industry

and in state and local government procure

ment programs. It had learned that

minority businesses had, as a result,

been excluded in dramatic fashion from

participation in government contracts.

Congress was, furthermore, aware of the

particularly severe effects of the

recession in 1977 on minority individuals

and minority businesses, and was aware

that these problems had to be addressed

quickly and decisively.

Congress' accumulated experience

with the problems of minority businesses

-8-

also made it aware that methods other

than a minority set-aside would be

ineffective in responding to this historic

discrimination and to the plight of

minorities during the 1977 recessionary

period.

Because the 1977 MBE provision was

limited to federally assisted state and

local construction projects, it would be

disingenuous to argue that the reasons

for the provision are obscure. The

historic discrimination against minorities

in the construction industry, which is

so notorious that it is an appropriate

subject for judicial notice, and the

exclusion of minorities from government

contract work provide a substantial founda

tion for the provision. Congress has

broad constitutional authority to respond

to such conditions in the exercise of

its spending power, and by virtue of the

enforcement clauses of the thirteenth

and fourteenth amendments. Congress'

response was temperate and rational:

the 1977 MBE provision was limited to a

small portion of government contract

work, could be waived where infeasible,

and lasted for only a limited period of

time. Congress did not abuse its authority.

-9-

ARGUMENT

I. ONLY THE POWER OF CONGRESS TO

REMEDY PAST AND PRESENT DISCRIMINA

TION BY MEANS OF A CIRCUMSCRIBED

MINORITY SET-ASIDE PROVISION IS AT

ISSUE.

It is essential to state clearly

what this case involves. It does not

involve the authority of a federal or

state administrative agency, or of a

state legislative body, to promulgate a

minority set-aside provision. It calls

into question only the authority of

Congress, the body explicitly charged

with enforcement of the thirteenth and

fourteenth amendments. This case also

does not involve a set-aside provision

relating to an area of economic activity

as to which evidence of discrimination

and exclusion of minorities was lacking.

To the contrary, Congress was fully

informed of the specific problems addressed

by the 1977 MBE provision. This case

also does not involve a federal program

depriving white contractors of existing

federal benefits. Although some public

works funds were set aside for MBE1s, as

part and parcel of the same program, 3.6

billion additional dollars were made

-10-

fully available to all contractors.

Finally, this case does not involve a

permanent minority set-aside, or even

one which would continue in the absence

of further congressional action. This

particular set aside was limited to the

term of the 1977 PWEA.—^

Since racial classifications pre

ferring minorities are not per se uncon

stitutional, University of California

Regents v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 272, 320

(1978) (Powell, J.); id. at 324-25

(Brennan, J.), the question posed by

this case is narrower and significantly

less difficult than any questions future

cases may pose.

2/ Because the 1977 MBE provision was

limited in this fashion, because petitioners

chose not to seek damages, and because Congress

in 1978 enacted a different set-aside provision,

see pp. 49 to 56 infra, so that there is no

"reasonable expectation" to believe that peti

tioners will again be subject to terms like

those contained in the 1977 MBE provision, cf.

First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, 435

U.S. 765, 774-75 (1978), there is a substantial

question of mootness. This brief does not

address that issue, which we believe will be

discussed at length in Respondent Secretary

of Commerce's brief.

-11-

II. CONGRESS EXERCISED ITS POWER ONLY

AFTER LONG AND DETAILED INVESTIGATION,

DEBATE AND REMEDIAL EXPERIMENTATION,

DURING WHICH IT HAD FOUND THAT

WIDESPREAD DISCRIMINATION AGAINST

MINORITIES EXISTED IN THE CONSTRUCTION

INDUSTRY AND IN THE LETTING OF

GOVERNMENT CONTRACTS, AND THAT THE

SET-ASIDE PROVISION WOULD ENHANCE

THE WELL-BEING OF THE ECONOMY.

A. The Floor Debates On The 1977

MBE Provision Capsulized The

Facts Which Justified Its Passage.

Petitioners' description of the

1977 MBE provision ignores many of the

statements made in the congressional

debate on the provision, as well as

other very substantial evidence supporting

the need for such a provision. Petitioners

argue that the "legislative history of

the PWEA is completely devoid of any

legislative findings or any other material

sufficient" to sustain the MBE provision.

They characterize the MBE provision as

nothing more than an unreasoned "after

thought" to give MBE's a "'share of the

action'" without justification. Brief

for Petitioners at 15; see Brief for

Petitioner, General Building Contractors

of New York State, Inc., The New York

State Building Chapter, Associated

-12-

General Contractors of America, Inc.

("Building Contractors' Brief") at 13.

Representative Mitchell in fact

directed Congress' attention to the

dismal history of federal programs

designed to create and support minority

businesses, and to the historical denial

of government contracts to minority

businesses. He did not, as petitioners

suggest, blatantly urge without justifi

cation that minority businesses should

receive a "share of the action". Mitchell

argued that the woeful record of all of

these existing federal programs, of

which Congress was well aware, see pp.

27 to 56 infra, would continue unless

Congress mandated the disbursement of

federal monies to minority enterprises.

Unless that were done, MBE's would be

unable to enter the economic mainstream,

and "support survival" programs would

continue to be a way of life for many

segments of our economy:

Let me tell the Members how

ridiculous it is not to target for

minority enterprises. We spend a

great deal of Federal money under

the SBA program creating, strengthen

ing and supporting minority businesses

and yet when it comes down to

giving those minority businesses a

-13-

piece of the action, the Federal

Government is absolutely remiss.

All it does is say that, "We will

create you on the one hand and, on

the other hand, we will deny you."

That denial is made absolutely

clear when one looks at the amount

of contracts let in any given

fiscal year and then one looks at

the percentage of minority contracts.

The average percentage of minority

contracts, of all Government

contracts, in any given fiscal

year, is 1 percent--l percent.

That is all we give them. On the

other hand we approve a budget for

OMBE, we approve a budget for the

SBA and we approve other budgets,

to run those minority enterprises,

to make them become viable entities

in our system but then on the other

hand we say no, they are cut off

from contracts.

In the present legislation

before us it seems to me that we

have an excellent opportunity to

begin to remedy this situation.

...[Sjetting aside contracts

for minorities... is the only way

we are going to get the minority

enterprises into our system.

...This is the only sensible

way for us to begin to develop a

viable economic system for minorities

in this country, with the ultimate

result being that we are going to

eventually be able to pull down

deficits in spending; we are going

to be able to end certain programs

which are merely support survival

programs for people which do not

-14-

contribute to the economy. I

support those programs because at

present we have nothing else to

offer. 123 Cong. Rec. H1436-37

(daily ed. Feb. 24, 1977).

Representative Mitchell ascribed the

problems of minority businesses not only

to their relative newness and small

size, attributable to prior discrimina

tion, see, e.g., pp. 32 to 64 infra, but

also to the resistance of government

contracting agencies which made it

necessary to mandate a minority enterprise

set-aside:

[MBE's] are so new on the

scene, we are so relatively small

that every time we go out for a

competitive bid, the larger, older,

more established companies are

always going to be successful in

underbidding us. Id. at H1437.

...[E]very agency of the

Government has tried to figure out

a way to avoid doing this very

thing [of letting contracts to

MBE's]. Believe me, these bureau

cracies can come up with 10,000

ways to avoid doing it. That is

why I am insisting it be mandated.

Id. at H1438.

...1 think we must look at

other States and cities around this

country that have not really addressed

the problem at all and do not have

any lever on which to hang an

operation designed to begin to

redress this grievance [of not

-15-

letting contracts to MBE's] that

has been extant for so long.

...By setting the tone at the

Federal level,...what we do in

terms of these local political

subdivisions is to give them the

added impetus to do those things

which are right and fair. Id. at

H1440.

Other congressmen recognized the

fundamental fairness of the amendment,

stating that it would mitigate the

latent inequities of the 1977 PWEA for

minority businesses and workers. Minori

ties had suffered disproportionately

in the recessionary period which continued

into 1977. They had gotten "the 'works'

almost every time" by being denied

participation in public works projects.

One reason was the governmental bidding

process, which was structured in a

manner effectively excluding minorities.

This was true in the experience of two

congressmen:

This Nation's record with

respect to providing opportunities

for minority businesses is a sorry

one. Unemployment among minority

groups is running as high as 35

percent. Approximately 20 percent

of minority businesses have been

dissolved in a period of economic

recession. The consequences have

been felt in millions of minority

homes across the Nation.

-16-

...Yet without adoption of

this amendment, this legislation

may be potentially inequitable to

minority businesses and workers.

It is time that the thousands of

minority businessmen enjoyed a

sense of economic parity. Id.

(remarks of Rep. Biaggi).

...[M]inority contractors and

businessmen who are trying to enter

in on the bidding process... get the

"works" almost every time. The

bidding process is one whose intri

cacies defy the imaginations of

most of us here. The sad fact of

the matter is that minority enter

prises usually lose out... Id.

(remarks of Rep. Conyers).

In the end, the House, by passing the

MBE amendment, attempted to change this

past history of minority exclusion from

public works contracts, by assuring

nothing more than an "equitable relation

ship for minority contractors and suppliers

to be able to participate, which...is

right and is proper." Id. at H1437

(remarks of Rep. Roe).

Like the House debate, the Senate

debate stressed the historical fact that

other federal efforts had failed to

overcome gross inequalities in the

letting of government contracts. In

-17-

debate, Senator Brooke also emphasized

the special anti-recessionary impact of

the MBE provision in reducing chronic

minority unemployment:

[I]t is important that we

focus on the unemployment experiences

of different ethnic and racial

groups in designing a sensitive and

responsive jobs program. For

example, among minority citizens,

the average rate of unemployment

runs double that among white citizens.

Our most recent experience

with...[administering the 1976 PWEA]

was marred by projects which were

inappropriate in light of the

strong congressional intent that

the public works funds be spent

where they are most needed.

...It is necessary because

minority businesses have received

only 1 percent of the Federal

contract dollar, despite repeated

legislation, Executive orders and

regulations mandating affirmative

efforts to include minority contrac

tors ....

...[T]he Federal Government,

for the last 10 years in programs

like SBA's 8(a) set-asides, and the

Railroad Revitalization Act's

minority resources centers, to name

a few, has accepted the set-aside

concept as a legitimate tool to

insure participation by hitherto

excluded or unrepresented groups.

It is an appropriate concept,

because minority businesses' work

forces are principally drawn from

-18-

residents of communities with

severe and chronic unemployment.

With more business, these firms can

hire even more minority citizens.

...This amendment provides a

rule-of-thumb which requires much

more than the vague "good-faith

efforts" language which currently

hampers our efforts to insure

minority participation. Id. at

S3910. ~

Thus, contrary to petitioners'

suggestion that the 1977 MBE provision

was an unreasoned effort to spread the

"action" of federal contracts, the

congressmen who spoke in favor of the

provision articulated the historical

exclusion of minorities from government

contract work, and the inadequacy of

alternative efforts to establish minority

businesses as viable participants in the

governmental contract process.

B. It Is Appropriate To Look To

Prior Legislative Inquiries

And Acts Of Congress, And To

Consider All The Evidence

Available To Congress, In

Reviewing The 1977 MBE Provision.

Although petitioners attempt to

narrow this Court's attention to the

specific floor debates on the 1977 MBE

provision, these debates need not and

-19-

should not be the limit of inquiry, for

the "constitutional propriety...[of a

statute] must be judged with reference

to the historical experience which it

reflects." South Carolina v. Katzenbach,

383 U.S. 301, 308 (1966). The ready

acceptance of the MBE provision by both

3 /houses of Congress— demonstrates that

Representative Mitchell's proposal did

not arise in a factual vacuum; it was,

in fact, considered "right and proper"

in view of two decades of legislative

and executive experience which had

preceeded it.—^ Congress need not

3/ Debate focused almost exclusively on

the feasibility of the ten percent figure in

areas with few minority individuals, with most

legislators otherwise accepting the appropriate

ness and fairness of the 1977 MBE provision. See

123 Cong. Rec. H1436-40 (daily ed. Feb. 24, 1977);

123 Cong. Rec. S3910 (daily ed. March 10, 1977).

4/ Petitioners, for example, claim that

Representative Mitchell's remarks "concerning

the rate of underutilization of MBE's were

merely naked assertions on his part." Brief for

Petitioners at 16. Mitchell stated that minorities

received one percent of government contracts in

an average fiscal year. 123 Cong. Rec. H1436-37

(daily ed. Feb. 24, 1977). Petitioners ignore

the fact that the Subcommittee on SBA Oversight

and Minority Enterprise of the House Committee

on Small Business had before it in 1975 a report

of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Minorities

and Woman as Government Contractors (May 1975),

which found that in 1972 minorities and women

received less than one percent of federal contracts.

See p. 41 n.14 infra.

- 2 0 -

re-invent the wheel by restating evidence

on the record whenever it passes yet

another bill in an evolutionary legis

lative program.-^ Indeed, the

fundamental basis for legislative

action is the knowledge, experience,

and judgment of the people’s rep

resentatives only a small part, or

even none, of which may come from

the hearings and reports of commit

tees or debates upon the floor.

Cox, The Supreme Court, 1965 Term --

Foreword: Constitutional Adjudica

tion and the Promotion of Human

Rights, 80 Harv. L. Rev. 91, 105

(1966) (footnote omitted).

Congress, in short, must be able to rely

on its accumulated knowledge and experience.

In addition to looking myopically

only at the debates immediately preceding

enactment of the 1977 MBE provision, and

thereby conveniently avoiding the eviden

tiary weight of years of congressional

5/ See, e.g., Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384

U.S. 641, 654 & n.14, 646 n.5 (1966) (relying on

hearings before prior Congress and on "understand

ing of the cultural milieu" existing in past);

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 330

(1966) ("In identifying past evils, Congress

obviously may avail itself of information from

any probative source."); Oregon v. Mitchell, 400

U.S. 112, 235 & n.10 (1970) (Brennan, J.) (reliance

on census data).

- 2 1 -

experience, see pp. 27 to 75 infra,

petitioners assert that Congress did not

make adequate formal "findings" of

discrimination in the construction

industry. Building Contractors' Brief

at 11-15; Brief for Petitioners at

14-17. Petitioners make much of the

fact that the MBE provision arose as a

floor amendment, and appear to suggest

that legislative action such as the MBE

provision should be found defective

unless it is supported by an independent

congressional "study", perhaps in the

form of committee consideration, and

unless it is specifically addressed by

"findings" in House and Senate reports

generated at the time of legislative

action. See Brief for Petitioners at 16

n.7; Building Contractors' Brief at

1 1 - 1 2 .

Of course, congressional committees

had previously made findings relevant to

the 1977 MBE provision. See, e.g., pp.

37 to 69 infra. Moreover, it is unsound

to demand that Congress proceed in so

formalized a fashion. Petitioners'

argument fails to recognize the signi-

- 2 2 -

ficance of the fact that this case

involves action by Congress, and there

fore fails to consider any distinction

between Congress and other bodies with

respect to the need for formal "findings"

as a prerequisite to decision-making.

See C. Black, Structure and Relationship

in Constitutional Law 67-98 (1969).

This Court has explicitly stated

that Congress is not required to make

formal "findings" in order to justify

the constitutionality of legislation.

Katzenbach v. MeLung, 379 U.S. 294, 299

(1964). See also Oregon v. Mitchell,

400 U.S. 112, 147 (1970) (Douglas, J.).

In conformity with the presumption of

constitutionality given Congress' actions,

this Court has recognized that legislation

should be found constitutional if there

is a basis on which Congress could

6/ Congress, of course, is not required

by custom, statute or rule to make findings

before it can act, unlike administrative agencies.

See 5 U.S.C. §§ 553(c); 557(c)(3)(A) (1976);

Securities and Exchange Comm1n v. Chenery Corp.,

318 U.S. 80, 94 (1943). See generally K. Davis,

Administrative Law Treatise, §§16.01 et seq.

(1958 and 1970 Supp.)

23-

rationally have acted. See Cox, supra,

80 Harv. L. Rev. at 104-05 & cases cited

in nn. 82-83.

Petitioners' argument could have

disastrous practical ramifications for

Congress. Legislation is frequently

accomplished through floor amendments,

see B. Gross, The Legislative Struggle

218 (1953), where "findings" are not and

need not be made. See Katzenbach v.

Morgan, 384 U.S. 641, 653, 654 (1966)

(reviewing amendment introduced on floor

of Congress without committee hearings

or reports); Cox, The Role of Congress

in Constitutional Determinations, 40 U.

Cin. L. Rev. 199 (1971). To impose the

formal requirement that "findings" be

made by the Congress would be unreasonable

...[D]ifferences from accus

tomed legal patterns merely reflect

faithfully the different logic and

discipline of the legislative

process, within which the legisla

tive counselor or representative

must work.

...[T]he business of a legis

lator is not to adjudicate, but to

legislate___ [H]is policy choices,

whether statesmanlike or deplorable,

are not limited to any pleadings or

points raised in argument. If it

-24-

were otherwise, the legislative

process in our particular form of

representative government would

choke in a hopeless tangle of

formal procedures within a few

weeks. During the Eighty-fourth

Congress 19,039 bills and resolu

tions were introduced in the two

houses, 5,753 were reported out by

the committees, and 1,028 public

bills were enacted into law.

Linde, Book Review, 66 Yale L.J. 973,

975 (1957) (footnote omitted).

See also J. Chamberlain, Legislative

Processes, National and State 7 (1936).

In addition to these practical

considerations, "findings" are not the

source of Congress' legitimacy. Unlike

a university faculty, or the commis

sioners of an administrative agency, the

members of Congress are directly answer-

able to their constituents, a majority

of whom are white, when they establish a

remedial program such as the 1977 MBE

provision. The political accountability

inherent in our representative form of

government, and not formalized procedures

and fact-finding, is the mainspring of

Congress' legitimacy and an effective

check on its authority in a case where

-25-

racial minorities are favored. Cf. The

Federalist Nos. 52, 57; H. Linde &

G. Bunn, Legislative and Administrative

Processes 736 (1976). This political

accountability also permits greater

judicial deference to Congress. "[A]s

the most broadly representative, poli

tically responsible institution of

government," Congress is most likely to

reach "a focused judgment about the

appropriate balance to be struck between

competing values." Sandalow, Racial

Preferences in Higher Education: Political

Responsibility and the Judicial Role, 42

U. Chi. L. Rev. 653, 701 (1975) (footnote

omitted).

Knowing that Congress does not act

in isolation from its past experience,

the congressional proponents of the 1977

MBE provision explicitly recognized its

relationship to several ongoing federal

legislative programs with which Congress

was familiar, and against which the

provision must be judged. These include:

(1) The Small Business Act, adopted in

1953 and repeatedly amended, in response

to additional evidence, with increasing

-26-

focus on minority business enterprises;

(2) legislation designed to use the

federal government's spending power to

remedy discrimination and to prevent the

federal government from being implicated

in discrimination practiced by recipients

of federal aid; and (3) the anti-reces

sionary Public Works Employment Act of

1976, and its 1977 amendments, which

required the swift spreading of money

throughout the country to those most

likely to spend, so as to maximize the

anti-recessionary effect of each federal

dollar. It is to these legislative

programs that analysis of the 1977 MBE

provision must turn.

1. In amending and enforcing the

Small Business Act, Congress

and the Executive have made

studies of minority businesses,

the discrimination they have

suffered, and the effectiveness

of various remedial strategies.

Both Congressman Mitchell and

Senator Brooke recognized that the 1977

MBE provision at issue in this case was

the next step in an evolving series of

Small Business Administration (hereinafter

"SBA") programs designed to aid minority

*

-27-

businesses. This recognition reflects

the fact that Congress had focused on the

problems of minority business enterprises

on numerous occasions during its oversight

of the Small Business Act.—^ Congress'

overall knowledge of, and concern with,

the problems of minority-owned businesses

is fully understood best by reference to

that Act.

Congress and the Executive have

repeatedly found a history of discrimination

against minorities which has resulted in

their exclusion from the mainstream of

the American economy and, in particular,

from government contracts, which represent

a sizeable amount of contracting dollars.

This exclusion has been found to result

not only from the debilitating effects

of discrimination which impair the

inherent ability of MBE's to compete

7/ Minority persons own few businesses,

and the businesses they own are small. See,

e-g., U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Report,

Minorities and Women as Government Contractors

11 (May 1975) (Respondent Kreps' Ex. No. 1, App.

124a); Bureau of Census, Special Report, Minority-

Owned Businesses, 1972 Survey of Minority-Owned

Business Enterprises, MB72-4, Table 1 at 16 (May

1975).

-28-

successfully, but also from the attitudes

of government procurement officers who

have resisted giving contracts to minority

enterprises. In response to this dis

crimination, a variety of remedial

programs have been tried, including

contract set-aside provisions. The MBE

provision involved in this case is an

evolutionary step, necessitated in

Congress' judgment by the failure of

existing programs.

For at least 26 years Congress has

sought to foster small businesses and

assure them their fair share of government

contracts, and specifically subcontracts

for construction. In the Small Business

Act of 1953, Pub. L. No. 163, title II,

67 Stat. 232, amended by Act of July 18,

1958, Pub. L. No. 85-536, 72 Stat. 384

(codified at 15 U.S.C. §§631 et seq.),

Congress declared that the entry of

individuals and small business enterprises

into the market and the fair distri

bution of government contracts to them

was essential to a strong economy, an

efficient government procurement program,

and fairness to the individual small

-29-

business person. Id. §2(a) (codified at

15 U.S.C. §631(a)).

In addition to providing for direct

loans and technical advice, the Small

Business Act from the beginning created

a government contract set-aside program

for small businesses. Id. §8(a) (codi

fied at 15 U.S.C. §637(a)). This program,

known as "the 8(a) program", was discussed

by Senator Brooke during debate on the

1977 MBE provision. It originally

authorized the SBA to enter into contracts

with federal procurement officers for

the acquisition of government supplies

and equipment, and to subcontract, in

turn, to small businesses for the per

formance of such contracts. From the

start, also, the SBA was expressly

charged with taking government-wide

"action to encourage the letting of

subcontracts by [private] prime contractors

[on federal projects] to small-business

concerns," not on strictly competitive

8 /terms,—7 but "at prices and on conditions

8/ The Small Business Act, as amended,

provides for a variety of non-racial special

preferences to small businesses, and thus deviates

repeatedly from the principle of strict market

competition. See, e.g., 15 U.S.C.A. §§636(b),

(i), (j) (3) (1979).

-30-

and terms which are fair and equitable."

Id. §8(b)(5) (codified at 15 U.S.C.

§637(b)(5)).-7

By 1967, Congress perceived the

need to go one step further and to

emphasize the needs of a specific portion

of small businesses; it required the SBA

to assure that federal funds would

benefit low-income persons and the areas

in which they lived. The Economic

Opportunity Amendments of 1967, Pub. L.

No. 90-222, title II, 81 Stat. 710

(codified at 42 U.S.C. §§2901 et seq.),

provided that the SBA should give "special

attention to small business concerns

(1) located in...areas with high propor

tions of unemployed or low-income indivi

duals, or (2) owned by low-income indivi

duals." Id. §406(a). It authorized the

9/ In 1961, another small business subcon

tracting program was added to the SBA to further

assure that small businesses would be "considered

fairly as subcontractors" for government contracts.

Small Business Act Amendments of 1961, Pub.

L. No. 87-305, §7, 75 Stat. 667 (codified at 15

U.S.C. §637(d)). This amendment provided that

"the extensive use of subcontractors by a proposed

contractor" would be a "favorable factor" in

"evaluating bids or selecting contractors for

negotiated contracts...."

-31-

SBA to assure "that contracts, [and]

subcontracts ...[made] in connection with

programs aided with Federal funds are

placed in such a way as to further the

purposes of this title." Id. §407(a).

Following widespread urban unrest

in 1967, President Johnson appointed the

National Advisory Commission on Civil

Disorders (the Kerner Commission) to

investigate the civil disorders in black

ghettos throughout the nation. Its

report found discrimination rampant in

American life. One of its "Recommenda

tions for National Action" was "[e]n-

couraging business ownership in the

ghetto" by minority individuals. Report

of The National Advisory Commission on

Civil Disorders 236 (March 1, 1968).

Despite the decade-old mandate of the

SBA to encourage small business, the

Commission found that the benefits of

SBA programs had not adequately reached

minority enterprises:

We believe it is important to

give special encouragement to Negro

ownership of business in ghetto

areas. The disadvantaged need help

in obtaining managerial experience

and in creating for themselves a

-32-

stake in the economic community.

The advantages of Negro entrepre

neurship also include self-employment

and jobs for others.

Existing Small Business Adminis

tration equity and operating loan

programs, under which almost 3,500

loans were made during fiscal year

1967, should be substantially

expanded in amount, extended to

higher risk ventures, and promoted

widely through offices in the

ghetto. Loans under Small Business

Administration guarantees, which

are now authorized, should be

actively encouraged among local

lending institutions. Id.

A response to the Kerner Commission's

recommendation (and the discrimination

which it described) required focusing

long-standing SBA programs still more

narrowly on minority business enter

prises, the segment of small business

most beset with difficulties.

Three presidential orders— ^ followed

in the ensuing three years, premised on

10/ Executive Order 11458, Prescribing

Arrangements for Developing and Coordinating a

National Program for Minority Business Enterprise,

3 CFR, 1966-1970 Comp., p. 779 (March 1969)

(ordering Secretary of Commerce to develop

"comprehensive plans of Federal action" to

promote the "growth of minority1 business enter

prises"); Executive Order 11518, Providing for

(footnote continued)

-33-

the Increased Representation of the Interests of

Small Business Concerns Before Departments and

Agencies of the United States Government, 3 CFR,

1966-1970 Comp., p. 907 (March 1970) (ordering

that the SBA "shall particularly consider the

needs and interests of minority-owned small

business concerns and of members of minority

groups seeking entry into the business community");

Executive Order 11625, Prescribing Additional

Arrangements for Developing and Coordinating a

National Program for Minority Business Enterprise,

3 CFR, 1971-1975 Comp., p. 616 (October 1971)

(noting that "social and economic justice"

required the "opportunity for full participation

in our free enterprise system by socially and

economically disadvantaged persons," who include

without limitation "Negroes, Puerto Ricans,

Spanish-speaking Americans, American Indians,

Eskimos, and Aleuts"; and requiring the Secretary

of Commerce to coordinate "an increased minority

enterprise effort," to develop "specific program

goals for the minority enterprise program...[and]

establish regular performance monitoring and

reporting systems to assure that goals are being

achieved.").

In response to the first Order, the Office

of Minority Business Enterprise ("OMBE"), mentioned

by Representative Mitchell during debate on the

1977 MBE provision, was established at the

Department of Commerce. It funds organizations

to "provide assistance to minority firms in

obtaining procurements from...State and local

governments, and the Federal Government.... A

construction firm for example may be assisted in

bidding and securing bonding for public or

private sector contracts...." Minority Enterprise

and Allied Problems of Small Business, H.R. Rep.

No. 94-468, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. 8 (Sept.

1975).

(footnote continued)

-34-

the finding that "members of certain

minority groups through no fault of

their own have been denied the full

opportunity" to "own their own busi

nesses and thereby to participate in our

free enterprise system". Executive

Order 11518, 3 CFR, 1966-1970 Comp., p.

907. The Secretary of Commerce was

required to establish a coordinated

federal program with specific goals and

monitoring systems and to encourage

state, local and private programs to

strengthen minority business enterprises.

As a result of the Kerner Commission

Report and the three Executive Orders,— ^

a regulation was promulgated further

narrowing the 8(a) program by specifically

limiting eligibility for that program to

11/ See S. Rep. No. 95-1070, 95th Cong., 2d

Sess. 14, reprinted in [1978] U.S. Code Cong. &

Ad. News 3835, 3849 ("The 8(a) program simply

evolved as a result of Executive orders issued

by Presidents Johnson and Nixon in response to

the 1967 Report of the Commission on Civil

Disorders ...[based on its] finding that... disad

vantaged individuals did not play an integral

role in America's free enterprise system, in

that they enjoyed no appreciable ownership of

small businesses....").

-35-

"disadvantaged persons. This category

often includes, but is not restricted

to, Black Americans, American Indians,

Spanish Americans, Oriental Americans,

Eskimos and Aleuts." 35 Fed. Reg. 17833

(Nov. 20, 1970) (codified at 13 CFR

§124.8-1). General government procurement

regulations were also promulgated,

requiring that "the maximum practicable

opportunity to participate in the perfor

mance of government contracts be provided

to minority business enterprises as

subcontractors." 36 Fed. Reg. 17509

(Sept. 1, 1971) (codified at 41 CFR

§1-1.1310-1) .— ^ They required clauses in

government procurement contracts com

mitting private contractors to use their

"best efforts" to maximize the partici-

12/ "For the purposes of this definition,

minority group members are Negroes, Spanish

speaking American persons, American-Orientals,

American-Indians, American-Eskimos, and American-

Aleuts." 36 Fed. Reg. 17509 (Sept. 1, 1971)

(codified at 41 CFR §§1-1.1303, 1-1.1310-2).

-36-

pation of minority businesses as subcon

tractors . — ^

Examination of MBE's by Congress

and administrative agencies became

exhaustive in 1975, only two years

before the passage of the MBE provision

13/ In addition to these Executive actions,

the Ninety-second Congress authorized the SBA to

create minority enterprise small business invest

ment companies (MESBIC's). Act of October 27,

1972, Pub. L. No. 92-595, §2(b), 86 Stat. 1314

(codified at 15 U.S.C. §681(d)). Their task was

to contribute to a "well-balanced national

economy by facilitating ownership in such concerns

by persons whose participation in the free

enterprise system is hampered because of social

or economic disadvantages...." Id. An amendment,

Act of October 24, 1978, Pub. L. No. 95-507,

title I, §104, 92 Stat. 1758, increased the

level of funding in order to reinvigorate these

MESBIC's, so as to compensate for the "[hjistori-

cally... acute shortage of equity capital and

long-term debt" for small concerns owned and

operated by socially and economically disadvantaged

individuals. S. Rep. No. 95-1070, 95th Cong.,

2d Sess. 3, reprinted in [1978] U.S. Code Cong.

& Ad. News 3835, 3838.

The Ninety-third Congress recognized and

confirmed the new emphasis in SBA policy by

creating the position of Associate Administrator

for Minority Small Business. Small Business

Amendments of 1974, Pub. L. No. 93-386, §6, 88

Stat. 748 (codified at 15 U.S.C. §633).

-37-

at issue in this case. In that year,

the Subcommittee on SBA Oversight and

Minority Enterprise of the House Committee

on Small Business held hearings to

review the foregoing existing "efforts

designed to assist the development of

minority business." Minority Enterprise

and Allied Problems of Small Business,

H.R. Rep. No. 94-468, 94th Cong., 1st

Sess. 1 (Sept. 1975) (summarized in

Summary of Activities of the Committee

on Small Business, H.R. Rep. No. 94-1791,

94th Cong., 2d Sess. 183 (Nov. 1976)

(Respondent Kreps1 Ex. No. 4, App.

123a)). Subcommittee Chairman Addabbo

noted the need for

effective remedial action...to

guarantee opportunities for full

economic participation to those

members of our society who have

traditionally encountered impediments

or obstacles to entering the mainstream

of business resulting from discrimina

tion or similar circumstances. Id.

^emphasis supplied).

In its report, the Subcommittee

found that the dearth of minority-owned

businesses was the result of racial

discrimination and that the Government1s

-38-

MBE programs had not cured the effects

of such discrimination. It stated:

The subcommittee is acutely

aware that the economic policies of

this Nation must function within

and be guided by our constitutional

system which guarantees "equal

protection of the laws." The

effects of past inequities stemming

from racial prejudice have not

remained in the past. The Congress

has recognized the reality that

past discriminatory practices have,

to some degree, adversely affected

our present economic system.

While minority persons comprise

about 16 percent of the Nation’s

population, of the 13 million

businesses in the United States,

only 382,000, or approximately 3.0

percent, are owned by minority

individuals. The most recent data

from the Department of Commerce

also indicates that the gross

receipts of all businesses in this

country totals about $2,540.8

billion, and of this amount only

$16.6 billion, or about 0.65 percent

was realized by minority business

concerns.

These statistics are not the

result of random chance. The presumption

must be made that past discriminatory

systems have resulted in present

economic inequities.... Id! at 1-2

(emphasis supplied).

The report reaffirmed the need for

remedial programs to assure equal oppor-

-39-

tunity, and concluded that they would be

proper if tempered by an equitable

balance between those minorities injured

by discrimination and those white persons

innocent of discriminatory acts:

In order to right this situation,

the Congress has formulated certain

remedial programs designed to

uplift those socially or economic

ally disadvantaged persons to a

level where they may effectively

participate in the business main

stream of our economy.

It is, of course, hoped that

some day remedial programs will be

unnecessary and that all people

will have the same economic oppor

tunities. However, until that time

remedial action must be considered

as a necessary and proper accom

modation for our Nation's socially

or economically disadvantaged

person....

The subcommittee is mindful

that remedial programs should not

be used in such manner as to unjustly

sacrifice the rights and privileges

of the majority.... A balance must

be struck and equity must be the

keynote. Id.

In its report, the Subcommittee

also related testimony about the inade

quacy of the 8(a) program from various

persons, including Representative Mitchell.

-40-

This testimony identified existing1 4 /

14/ The Subcommittee also had as evidence,

Minority Enterprise and Allied Problems of Small

Business, H.R. Rep. No. 94-468, 94th Cong., 1st

Sess. 11 (Sept. 1975), two government reports: a

GAO report, Questionable Effectiveness of the

8(a) Procurement Program, GGD-75-57 (April

1975), and a U.S. Commission on Civil Rights

Report, Minorities and Women as Government

Contractors (May 1975). It was found that

minority businesses are beset with, among other

handicaps, unwarranted resistance from government

contracting officers and that existing federal

programs are failures; both of these considera

tions were expressed in the floor debate in

support of the 1977 MBE provision.

On the basis of a wide-ranging survey of

federal, state and local agencies and procure

ment officers and of minority business persons,

id. at 142-175, the U.S. Commission on Civil

Rights Report concluded that minority firms

encounter "staggering" problems in bidding, in

obtaining capital and in obtaining contracting

information, id. at i. Moreover they are sub

jected to a great deal of unwarranted "skepticism"

about their competency by government contracting

officers. Id. Federal MBE programs have achieved

only "limited success", and there is only "limited"

compliance by state and local governments with

federal efforts to increase minority subcontracting.

Id. at ii. As a result, in 1972 minorities and

women received only 0.7 percent of federal

contracts, despite the fact that they represented

4 percent of all American business. Id. at 6, 111.

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights also

found that the MBE 8(a) program represents only

0.25 percent of all federal procurement spending,

and that the program is only a limited success.

(footnote continued)

-41-

Id. at 41-42. In particular, the Report noted

its slowness and lack of staff. Id. at 37-40,

46-47, 114. Finally, it found that the program

suffers from the unsupported belief of some

federal contracting officials, mostly white

males, that MBE firms are less competent than

others. Id. at 48-49, 112.

The Report found that the government-wide

minority subcontracting program has had little

impact; that federal contracting officers seldom

monitor or enforce subcontracting requirements,

id. at 78, 81-82, 84, 120-121; and that "from

all indications,...[the subcontracting program]

has failed to substantially increase either the

number or dollar amounts of subcontracts...,"

id. at 79.

The Report made similar findings with

respect to local and state government contracting

programs. Because state and local governments

spend more money on goods and services than the

federal government, and spend more on smaller

contracts for which small businesses are especially

suitable, and spend significantly more of their

dollars on construction contracts than the

federal government, the Report found that "the

volume and nature of State and local contracting

is sufficent to provide extensive contracting

opportunities to" minority and female firms.

Id. at 87. Nonetheless in the Commission's

survey, minority and female firms also were

found to receive only 0.7 percent of state and

local contracting dollars. Id. at 86, 122.

Federal regulatory efforts dcTnot appear to have

resulted in a significant increase in local and

state MBE programs. Id. at 89-93. The Commis

sion's survey data reported only ten jurisdictions,

of which New York was not one, which had estab

lished compliance programs under these regulations.

Id. at 87. Federal and state enforcement or

(footnote continued)

(footnote continued)

-42-

resistance of public and private parties

to minority contractors:

[T]here is a great deal of resistance,

particularly by the middle management

level of Federal procuring agencies,

to implement this [8(a)] program.

Private industry is likewise hesitant

to accept minority concerns... because

of an established mode of business

which has traditionally excluded

minority-owned businesses. This is

one reason...for the apparent

inability of 8(a) firms to secure

more commercial contracts. Id. at

1 1 .

As a result of its study, the Subcommittee

recommended an increase in the number of

8(a) contracts and the adoption of

specific criteria defining which con

tracts were to be set aside for minority

businesses. Id. at 34.

(footnote continued)

monitoring of "minority affirmative action

subcontracting programs is virtually nonexistent."

Id. at 91. In addition, the Report found that

"[n]egative attitudes among State and local

procurement officers also present a barrier to

the participation of minorities . . . as contrac

tors"; in general, these white male officials

believe that such minority firms could not be

relied upon to perform. Ld. at 106-107. It

noted that other contracting officials who were

interviewed believed that a contract set-aside

program was the most effective method for MBE

aid. Id. at 107.

-43-

With respect to government-wide

subcontracting regulations for minority

businesses, the Subcommittee found that

the "best efforts" regulations in 41

CFR Subpart 1-1.13 were "totally inadequate"

because of "a glaring lack of specific

objectives which each prime contractor

should be required to achieve," a "lack

of enforcement" and a lack of "meaningful

monitoring." Id. at 32. The Subcommittee