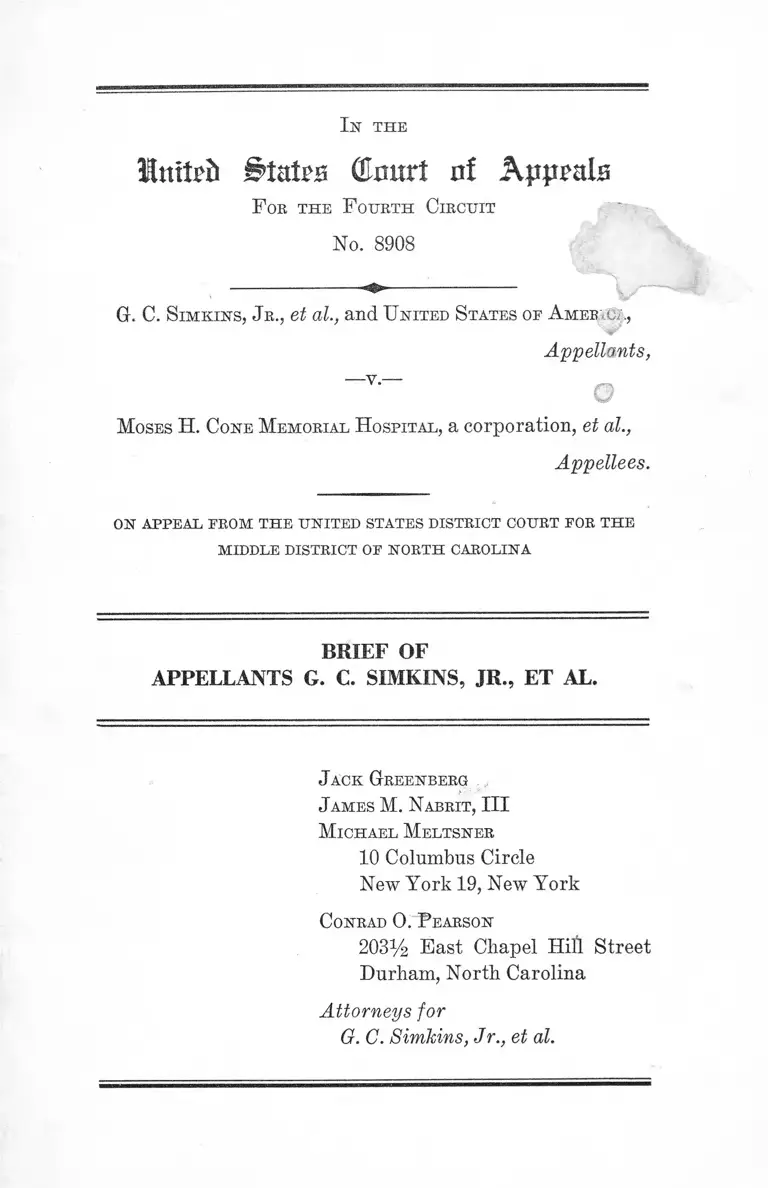

Simkins v Moses H Cone Memorial Hospital Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 17, 1962

50 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Simkins v Moses H Cone Memorial Hospital Brief of Appellants, 1962. 553bd36c-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a205a696-e90a-467e-9a18-6fe4f979fff1/simkins-v-moses-h-cone-memorial-hospital-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Hnttt'd States (Enurt nf Appals

F or the F ourth Circuit

No. 8908

G. C. Simkins, Jr., et al., and United States of A mebic;.,

Appellants,

“ v'“ o

Moses H. Cone Memorial H ospital, a corporation, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

■A

BRIEF OF

APPELLANTS G. C. SIMKINS, JR., ET AL.

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Conrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hifl Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for

G. C. Simkins, Jr., et al.

I N D E X

Statement of the Case'................................................ .... . 1

Questions Presented .............................................. ............ 5

PAGE

Statement of F acts ..................................................... 5

Hill-Bnrton Program ..................... 8

A. Federal Funds for Hospital Construction ........... 9

B. General Facts About Hill-Burton Program ....... 10

C. The North Carolina State P la n .............................. 11

D. Division of Federal and State Controls............... 12

The Training of State Nursing School Students at

Cone ....................................................................... 18

Argument ........................................... 20

I. The Appellees’ Contacts With Government Are

Sufficient to Place Them Under the Restraints of

the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments Against

Racial Discrimination..... ..... 20

Financial Contributions...................................... 21

State and Federal Controls to Implement

Public Policy .............................................. 23

Affirmative Governmental Sanction of Dis

crimination .................................................. ...... 31

Additional Factors Applicable to Cone Hos

pital ......... 33

Conclusion of Part I ............... ........................... 36

11

II. Those Portions of Title 42 U. S. C., §291e(f)

and 42 C. F. R., §53.112 Which Authorize Racial

Discrimination Violate the Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendments ............................................................ 37

Conclusion .................................... ........................ .............. 41

PAGE

T able oe Cases

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 198 F. Supp. 497 (E. D. Va. 1961) .... ...... 23

Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 U. S.

288 ........................................... .......................................... 40

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31 ............... ................ . 38

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961) ..26, 28, 30,

31, 33, 39

Betts v. Easley, 161 Kan. 459, 169 P. 2d 831 ...........27, 28

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 II. S. 497 ............................... ...20, 39

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 (5th

Cir. 1960) ............. ......................... ............. ..22,27,30,31,33

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 TJ. S. 483 .......20, 38, 39

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 ............................................................20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26,

31, 32, 34, 35, 36

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 .............................. ... ....20, 31

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ...... ............................20, 22, 23

Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 U. S. (4 Wheat.)

518 .......................................................... ............................ 35

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 220

F. 2d 387 (4th Cir. 1955), aff’d 350 U. S. 877 ........... 38

Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956),

cert. den. sub nom. Casey v. Plummer, 353 U. S. 924 .. 22

I l l

Eaton v. Board of Managers of James Walker Me

morial Hospital, 261 F. 2d 521 (4th Cir. 1958), cert,

den. 359 U. S. 984 .......................................................... 25

Flemming v. South Carolina Electric & Gas Co., 224

F. 2d 752 (4th Cir. 1955), appeal dismissed, 351II. S.

901 ...................................................................................... 33

Freeman v. Retail Clerks Local 1207, 45 Lab. Eel. Ref.

Man. 2334 (1959) ......... 30

Gantt v. Clemson Agricultural College of South Caro

lina (4th Cir. No. 8871, Jan. 16, 1963) ....................... 39

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 90 ....................................... 38

Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320 (5th

Cir. 1962), cert. den. sub nom. Gioto v. Hampton,

9 L. ed. 2d 170 ....... ..................................................... .25, 26

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 8 1 ................... 20

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 ....................... 38

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library, 170 F. 2d 212 (4th

Cir. 1945) ................................... 22

McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka and S. F. R. Co., 235 U. S.

151 (1914) ......... 32

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 .......................22, 26, 30, 35

Ming v. Horgan, 3 Race Rel. L. Rep. 693 (Cal. Super.

Ct. 1958) ............................................................................ 27

Monroe v. Pape, 365 IT. S. 167.................................. ....... 22

New Orleans City Park Improvement Asso. v. Detiege,

358 U. S. 54 ....... ................ ............................................. 38

Nison v. Condon, 287 U. S. 73 ...................................... 22, 33

Norris v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 78

F. Supp. 451 (D. Md. 1948) ............................ ........ .... 35

N. L. R. B. v. Babcock & Wilcox Co., 351 U. S. 105....... 30

PAGE

IV

Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors of City Trusts, 353

U. S. 230 ........ ........ ..... .................... ................... .......... 34

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ---------------------------- 38

Public Utilities Comm’n v. Poliak, 343 U. S. 451 .......26, 27

Railroad Trainmen v. Howard, 343 U. S. 768 ............... 21

Railway Employees Dept. v. Hanson, 351 U. S. 225 .... 27

Republic Aviation Corp. v. N. L. R. B., 324 U. S. 793 .... 30

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 .... ..............................26, 30

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 .................................. 22

State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey, 359 U. S. 533 .... 38

Steele v. Louisville, N. R. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192........... 27

Syres v. Oil Workers Int’l Union, 223 F. 2d 739 (5th

Cir. 1955), rev’d per curiam, 350 U. S. 892 ............... 27

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461-------------------- --------- ----- 22

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 ...............................35, 38

United States v. Raines, 362 U. S. 1 7 .............................. 22

Williams v. Hot Shoppes, 293 F. 2d 835 (D. C. Cir.

1961) ........................... ....... -............................................. 33

PAGE

Statutes I nvolved

28 U. S. C,, §§1331, 1343(3) ........................................... 3

28 U. S. C., §2403 .............................................................. 3

42 C. F. R., §53.1 (v) ........................................................ 28

42 C. F. R., §53.11 ............ 16

42 C. F. R., §§53.12, 53.13 ............................................... 17

42 C. F. R., §§53.71-53.80 ................................................. 17

42 C. F. R., §53.111 .......................................... ........ 11,18, 37

V

42 C. F. R., §53.112 .......................................... 2, 5,11,17,18,

21, 37, 38

42 C. F. R., §53.124 ................. 17

42 C. F. R., §53.125 .......................................................... 13

42 C. F. R., §53.127(b) ............. 17

42 C. F. R., §§53.127(c ) ( l) - (9 ) ......................... 13

42 C. F. R., §53.127(d)(l) ...... 15

42 C. F. R., §§53.101, 53.127(d)(2) ................. 13

42 C. F. R., §53.127(d) (4) ..... 18

42 C. F. R., §53.127(d)(5) ............................................... 15

42 C. F. R., §53.127(d) (6) ............................................... 17

42 C. F. R., §53.128 ......... 13

42 C. F. R., §53.130 .................................................... 14

42 0. F. R., §§53.131 et seq........................................... .13,14

42 C. F. R., §53.134 ...... 14

42 C. F. R., §§53.150(a), 53.151 ...... 14

42 U. S. C., §291 ........... 30

42 U. S. C., §291e(a) (b )(0)(d ) .......... ....... .................. - 16

42 U. S. C., §291e(e) ......................................................... 13

42 IJ. S. C., §291e(f) ............. 2,5,11,17,18,20,

31, 32, 37, 38

42 U. S. C., §291f(a)(4)(D ) ............ 17

42 U. S. C., §291f (a) (7) ................ 15

42 U. S. C., §291f (a) (8) .......... 17

PAGE

42 U. S. C., 129 I f id) ....... ........ ........... ......... ............. -.15,16

42 U. S. C., §291f(e) ....... .................. ..... - ..................... 10

42 IT. S. C., §291g .......................................... ................... 10

42 U. S. C., T 29 111 in) ....................................... ....... -..... 13,17

42 1’ . S. C., §291h(d) ...... ............................................... 24

42 IT. S. ('., §291h(e) .................................-............ 14. 21.25

42 U. S. C., §291j .................................................. ............. 17

42 U. S. C., §291m ....... .... .................... - ......................... 15

42 IT. S. C., §§292, et seq.................................................. 15

42 IT. S. C., §292g ............................................ -................ 15

42 IT. S. C., §§1981, 1983 ................................................ 3

State Statutes

N. C. Gen. Stats., §§90-1 et seq....................................... 33

N. C. Gen. Stats., §§122-3, 122-5, 122-83, 122-84, 122-

88, 116-26 ........ .................................................. -............. 38

N. C. Gen. Stats., §§130-4 et seq..................................... 33

N. C. Gen. Stats., §131-117 .............................................. 6

N. C. Gen. Stats., §131-120 .............................................. 11

N. C. Gen. Stats., §§131-126.1 et seq. .........................15,16

Private Laws of N. C., 1913, ch. 400 ......................... 6

Session Laws of N. C., 1961, ch. 234 ................ 6

Session Laws of N. C., 1947, c. 933 ............................. 16

vi

PAGE

V ll

Other A uthorities

PAGE

“ Equal Protection of the Laws Concerning Medical

Care in North Carolina” (Subcommittee on Medical

Care of the North Carolina Advisory Committee to

the United States Commission on Civil Eights)

(mimeographed) ................................... ..... .................. 36, 37

“Hill-Burton Program—Progress Report, July 1, 1947-

June 30, 1961,” U. S. Department of HEW, Public

Health Service Publication No. 880 (1961) ............. . 10

“ The Nation’s Health Facilities: Ten Years of the

Hill-Burton Program 1946-1956,” Public Health Ser

vice Publication No. 616 (1958) .................................. 31

Reitzes, Negroes and Medicine, 1958 .............................. 36

I n t h e

lutteft CEmirt of Appeals

F oe the F ourth Circuit

No. 8908

G. C. Simkins, Jr., et al., and United States of A merica,

Appellants,

Moses H. Cone Memorial H ospital, a corporation, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF OF

APPELLANTS G. C. SIMKINS, JR., ET AL.

Statement of the Case

This appeal is from a final order entered December 17,

1962, granting defendants’ Motion to Dismiss for lack of

jurisdiction and denying motions by plaintiffs and the

United States (which intervened) for summary judgment

(223a). The opinion below, 211 F. Supp. 628, appears at

195a-222a.

Plaintiffs, a group of Negro physicians, dentists and pa

tients, brought this class action to enjoin two hospitals in

Greensboro, North Carolina (the Moses H. Cone Memorial

Hospital and Wesley Long Community Hospital, herein

after called Cone Hospital and Long Hospital) and their ad-

2

ministrators from continuing to deny them and other

Negroes admission to staff and treatment facilities on the

basis of race. They also sought a declaration that a portion

of the Hill-Burton Act (Hospital Survey and Construction

Act of 1946, Act of Aug. 13,1946, 60 Stat. 1041, as amended;

42 IT. S. C. §291 et seq.) and a regulation pursuant thereto

(42 C. F. R. §53-112; 21 F. R. 9841) were unconstitutional.

The provisions attacked authorize racial segregation or ex

clusion of Negroes from hospitals receiving grants under

the Act on a “ separate but equal” theory, as an exception

to a statutory requirement of racial nondiscrimination.1

| 42 U. S. C. §291(e)(f) provides:

“ 291e. General regulations.—Within six months after the enactment of

tills title, the Surgeon General, with the approval of the Federal Hospital

Council and the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, shall by

general regulation prescribe—

* * * * *

“ ( f ) The State plan shall provide for adequate hospital facilities for

the people residing in a State, without discrimination on account of race,

creed, or color, and shall provide for adequate hospital facilities for

persons unable to pay therefor. Such regulation may require that before

approval of any application for a hospital or addition to a hospital is

recommended by a State agency, assurance shall be received by the State

from the applicant that (1) such hospital or addition to a hospital will be

made available to all persons residing in the territorial area of the appli

cant, without discrimination on account of race, creed or color, but an

exception shall be made in cases where separate hospital facilities are

provided for separate population groups, i f the plan makes equitable pro

vision on the basis of need for facilities and services of like quality for

each such group; and (2) there will be made available in each such

hospital or addition to a hospital a reasonable volume of hospital services

to persons unable to pay therefor, but an exception shall be made i f such

a requirement is not feasible from a financial standpoint.”

42 C. F. E. 553-112 provides:

tt* *. “ §53.112 Nondiscrimination. Before a construction application is

* recommended by a State agency for approval, the State agency shall

obtain assurance from the applicant that the facilities to be built with

aid under the Act will be made available without discrimination on account

of race, creed, or color, to all persons residing in the area to be served

by that facility. However, in any area where separate hospital, diagnostic

or treatment center, rehabilitation or nursing home facilities, are provided

for separate population groups, the State agency may waive the require

ment of assurance from the construction applicant i f (a) it finds that the

3

The complaint asserted “ federal question” and “ civil

rights” jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C. §§1331, 1343(3); 42

U. S. C. §§1981, 1983.* 2 Plaintiffs claimed infringement of

their rights under the due process clause of the Fifth

Amendment and the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

The complaint was filed February 12, 1962 (4 a ); there

after defendants moved to dismiss (19a) and filed affidavits

and exhibits supporting the motion (20a-67a). Defendants

urged that the court lacked jurisdiction over the subject

matter saying that plaintiffs claimed civil rights depriva

tions only by “private corporations and other individuals”

(19a). Plaintiffs countered with a motion for summary

judgment (72a) supported by affidavits and certified public

documents supporting the complaint (76a-164a).3

The United States of America filed a Motion to Intervene

(165a) and a Pleading in Intervention (166a-172a), May 8,

1962. The motion, under 28 U. S. C. §2403 and Rule 24(a),

F. R. C. P., asserted the Government’s right to intervene

since “ the constitutionality of an Act of Congress . . . af

fecting the public interest . . . [was] drawn into ques

plan otherwise makes equitable provision on the basis of need for facilities

and services of like quality for each such population group in the area,

and (b) such finding is subsequently approved by the Surgeon General.

Facilities provided under the Federal Act will be considered as making

equitable provision for separate population groups when the facilities to

be built for the group less well provided for heretofore are equal to the

proportion of such group in the total population of the area, except that

the State plan shall not program facilities for a separate population group

for construction beyond the level of adequacy for such group.” A

' * —

2 The jurisdictional amount was alleged, and plaintiff physicians and den

tists asserted a loss of earnings and interference with the practice of their

professions (5a, 16a).

3 The affidavits and exhibits in Appellants’ Appendix are fairly repre

sentative of the materials. The other materials are largely cumulative or

adequately covered by the Findings of Fact. The original record on file here

contains all exhibits, including affidavits by all plaintiffs and papers document

ing each of the Federal Government financial grants to defendants.

4

tion . . . ” (165a). The pleading in intervention supported

plaintiffs’ complaint that defendants’ conduct violated the

Fourteenth Amendment and that the portion of the Hill-

Burton Act authorizing the Surgeon General of the United

States to prescribe regulations concerning separate hospi

tal facilities for separate population groups should be de

clared unconstitutional (171a-172a).

The court heard all pending motions June 26, 1962,

granted the motion to intervene (188a), and denied plain

tiffs’ motion for preliminary injunction (68a, 192a). As

the parties agreed that only legal issues were disputed, the

court directed that they file proposed findings and conclu

sions based upon the documentary evidence (193a-194a).

This was done and all briefs and responses were submitted

by J uly 30, 1962.

The court determined that there was “ no dispute as to

any material fact” on the basis of these submissions and

proceeded to find the facts and determine the merits of the

case (196a). In an opinion dated December 5, 1962 (195a),

the Court said that racial discrimination was “ clearly estab

lished” (205a), and that the “ sole question” was whether

“ defendants have been shown to be so impressed with a

public interest as to render them instrumentalities of gov

ernment, and thus within the reach of the Fifth and Four

teenth Amendments . . . ” (206a-207a). After examining

defendants’ various contacts with federal and state govern

mental agencies the Court concluded that defendants were

not subject to constitutional restraints against racial dis

crimination (221a). The Court refused to decide the validity

of the “ separate but equal” provision of the Hill-Burton

Act, ruling this unnecessary to the disposition of the case

(220a). Judgment was entered accordingly December 17,

1962 (223a).

Plaintiffs and the United States filed notices of appeal

January 4 and 11, 1963, respectively (224a, 225a).

5

Questions Presented

1. Whether the appellees’ contacts with government are

sufficient to place them under the restraints of the Fifth and

Fourteenth Amendments against racial discrimination.

2. Whether those portions of Title 42, XL S. C., §291e(f)

and 42 C. F. E., §53.112 which authorize racial discrimina

tion violate the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.

Statement of Facts

Six plaintiffs are physicians and three are dentists; all

are duly licensed and practice their professions in Greens

boro. They sought and were denied staff privileges at the

hospitals because of racial exclusionary policies (198a,

205a). Two plaintiffs, patients of doctors Noel and Simkins,

need and desire treatment by their doctors at defendant

hospitals (197a). They sought relief against Long Hos

pital’s policy of completely excluding Negro patients, and

Cone Hospital’s policy excluding all Negroes but a selected

few admitted on conditions not applied to whites (198a).4

The claims of racial discrimination were amply docu

mented. Indeed, the hospitals’ applications for federal

grants for construction projects stated that “ certain persons

in the area will be denied admission to the proposed

facilities as patients because of race, creed or color” (93a),

and these applications were approved by the North Carolina

Medical Care Commission and the Surgeon General of the

4 Cone Hospital’s policy regarding Negro patients is detailed at 80a.

Negroes are admitted only where they require services not available at the

all Negro hospital, and they have a physician who is on both the Negro

hospital and the Cone staffs. Only white physicians are on both staffs. Thus,

to transfer a patient must discharge his Negro doctor and obtain a white

doctor (see 78a, 83a).

6

United States (99a).5 The North Carolina Medical Care

Commission, a State agency (N. C. Gen. Stats. §§131-117

et seq.) planned separate hospital facilities for Negroes

and whites in Greensboro, designating Long and Cone for

white patients and the L. Richardson Memorial Hospital

for Negroes (120a). The project applications reflect the

planned racial separation (99a), as well as the Surgeon

General’s approval of North Carolina’s “ State Plan” (103a).

On the day following the order dismissing the ease, Cone

Hospital advised plaintiffs, and publicly announced, that it

would consider staff applications from Negroes. The policy

with respect to Negro patients was not changed. This

development, of course, does not appear in the record, but

was confirmed in an exchange of correspondence between

counsel.

Both Cone and Long are nonprofit hospitals owned and

governed by boards of trustees.6 The Wesley Long Hospital

is a charitable corporation governed by a selfperpetuating

board of twelve trustees (200a). Its Certificate of Incor

poration as amended appears at 60a.

The Cone Hospital is also a charitable North Carolina

corporation governed by fifteen trustees. Cone Hospital’s

Articles of Incorporation filed in 1911 (22a), were ratified

and certain additional powers and provisions for the future

government of the hospital were granted by the State of

North Carolina through a Legislative Charter enacted in

1913 (32a-44a; Private Laws of N. C. 1913, Ch. 400), and

amended in 1961 (45a-54a; Session Laws of N. C. 1961, Ch.

5 The citations are to the government files on an application by Long

Hospital— Project No. NC-311. Similar materials in four other projects ap

pear in the record as Exhibits A, G, D and E supporting plaintiffs’ motion

for summary judgment.

6 In 1960 the United States had about 5,567 nonprofit hospitals, 1,784

governmentally owned hospitals and 1,010 proprietary hospitals, excluding

psychiatric hospitals (175a).

7

234). The currently applicable enactment (45a-54a) pro

vides that the 15 Cone trustees be selected for four year

terms as follows (50a-52a):

(a) Three appointed by Governor of North Carolina;

(b) One appointed by Greensboro City Board of Com

missioners;

(c) One appointed by Board of Commissioners of Guil

ford County, North Carolina;

(d) One appointed by Guilford County Medical Society;7

(e) Eight seats on board appointed by Mrs. Bertha Cone

until her death in 1947, now elected by entire board of 15

members;

(f) One seat appointed by Board of Commissioners of

Watauga County, North Carolina until 1961 amendment to

Charter, now elected by entire board of 15 members.

The corporate charters of the hospitals reflect their pur

poses to maintain general hospitals on a nonprofit basis.

Cone’s charter provides that the “board of trustees shall

have full power to prescribe the classes of patients, as re

gards diseases,8 who shall be admitted or refused or dis

missed: Provided, however, that no patient shall be re

fused admission nor be discharged because of inability to

pay” (49a-50a). Long’s certificate of incorporation au

thorizes it to conduct a general hospital in Greensboro or

Guilford County with such facilities as are necessary and

desirable to serve “ the public and the community in which

said hospital is located” (61a), and its income is to be used

for various medical activities including promoting “ the

7 The court below assumed for purposes of its decision, that the Guilford

County Medical Society was a “public agency” (207a). Plaintiffs’ argument

that the society’s function is “ governmental” in Fourteenth Amendment

terms for purposes of this ease appears in the argument, infra p. 33.

8 Emphasis supplied.

8

general health of the community” (65a). Neither hospital’s

charter contains any provision explicitly or implicitly au

thorizing or requiring the exclusion of Negro professionals

or patients.

Both hospitals are exempt from ad valorem taxes as

sessed by the City of Greensboro and Guilford County at

tax rates of $1.27 and $0.82 per $100 valuation respectively.

The cost of the construction projects for the two hospitals

revealed in this record (Cone: $7,367,023.32; Long:

$3,927,385.40) indicates that their property is extremely

valuable and that the value of the tax exemption is a sub

stantial sum for each hospital.9

Hill-Burton Program

Both hospitals have a variety of contacts with govern

ment as a result of their involvement in the Hill-Burton

hospital construction program. In summary, both hospitals

have received large amounts of public funds, paid by the

United States to the State of North Carolina and by North

Carolina to the hospitals; they received the funds as a

part of a “ State Plan” for hospital construction, which

contemplates and authorizes them to exclude Negroes and

was approved by the Surgeon General of the United States

under statutory authorization; and they are subject to a

complex pattern of governmental regulations and controls

arising out of the Hill-Burton participation. These various

relations justify a detailed explanation.

9 Assuming assessment at 50% of actual value, and given the combined

city-county rate of $2.09 per $100, Cone’s exemption is worth about $76,985

per annum and Long’s is worth about $40,681 per annum.

9

A. Federal Funds for Hospital Construction

When this action was commenced, the United States

had appropriated $1,269,950.00 to Cone Hospital and

$1,948,800.00 to Long Hospital. Cone had already received

these funds which amounted to about fifteen percent of the

total construction expenses involved in its two projects.

Long had received most of the funds appropriated to it

(over $1,500,000 already paid) which constitute about fifty

percent of the total cost of its three projects (203a-204a).

The following table summarizes the various grants:10

CONE HOSPITAL

Project No.

and Year

Approved Purpose

Federal Funds

Appropriated

5J8/62

Total Cost

of Project

Federal %

of Cost

NC-86

(1954)

General hospital

Construction

$ 462,000.00 $5,277,023.32

NC-330

(1960)

Diagnostic and

treatment center ;

general hospital

construction

807,950.00 2,090,000.00

Total $1,269,950.00** $7,367,023.32 17.2%*

LONG HOSPITAL

NC-311

(1959)

New hospital

construction

$1,617,150.00 $3,314,749.40

NC-353

(1961)

Laundry 66,000.00 120,000.00

NC-358

(1961)

Hospital Nurses

Training School

265,000.00 492,636.00

Total $1,948,800.00** $3,927,385.40 49.6%*

*The Court found “ approximately” 15% for Cone and “approximately” 50% for Long.

**AU funds to Cone had been paid as of 5/8 /62; $1,596,301.60 had been paid to Long by

that date.

10 See, generally, Findings 11 through 17 (201a-204a). Further details

appear in the original record, Exhibits A through E to plaintiffs’ Motion for

Summary Judgment. (Parts of Exhibit B appear at 93a-103a.)

1 0

B. General Facts About Hill-Burton Program

0 The Hill-Burton program requires that states wishing

to participate must inventory existing facilities to deter

mine hospital construction needs and develop construction

priorities under federal standards. State agencies are

designated to perform this function and to adopt state

wide plans to be submitted for the approval of the Surgeon

General of the United States. The Act establishes grants

of federal funds for construction of new or additional

facilities for governmentally owned hospitals and voluntary

nonprofit hospitals.*

In the first fifteen years of the program (1947-1961),

approximately $1.55 billion of federal funds were approved

for such projects. Slightly more than half of the total

went to voluntary nonprofit hospital projects. In the same

period state and local funds (governmental and nongovern

mental) totaled about $3.38 billion; thus, the federal share

of Hill-Burton projects was slightly more than thirty per

cent of their total cost. About 238,946 additional hospital

beds were made- available by the program.44

The allotment of federal funds among the states is deter

mined by a mathematical formula basgd on population and

per capita income (42 U. S. C. §291^). The “ federal share”

of costs of particular projects within a state is gove|^e^.

by federal approved state plans (42 U, SL C. i-9H‘(>)).

' North Carolina’s current plan programs general hospital

/ facilities based on a “ federal share” of 55% (112a).

A helpful description of the over-all program and of the various types

of hospitals is contained in the “Affidavit and Report” of the General Coun

sel of the Department of HEW who was the principal technical draftsman

of the law (173a-188a). This Report was filed in the court below by the

United States^-— ■

12_; See “ Hill-Burton Program—Progres Report, July 1, 1947—June 30,

% 1961,” U. S. Department of HEW, Public Health Service Publication No.

880, 1961.

1 1

The Surgeon General has authorized state plans to meet

the racial nondiscrimination requirement of 42 U. S. C.

§291e(f) by planning separate facilities for “ separate

population groups” (42 C. F. E. §53.112). When state plans

are submitted on this basis, the state agency and the

Surgeon General may waive the requirement that facilities

built under the Act “ be made available without discrimina

tion on account of race, creed or color, to all persons

residing in the area to be served by that facility” (42

C. F. E. §53.112; see also, §53.111).

C. The North Carolina State Plan

In North Carolina the state agency authorized to operate

under the Hill-Burton program is the North Carolina

Medical Care Commission (N. C. Gen. Stats. §131-120).

The Medical Care Commission has adopted and periodically

revised a “ State Plan” for separate facilities for Negroes

and whites in the Greensboro area (120a):

Existing

Acceptable Beds

Area Name of Facility Location White

Non-

White

B-6 L. Eichardson Memorial

Hospital Greensboro 0 91

Wesley Long Hospital Greensboro 220 0

Moses H. Cone Hospital Greensboro 482 0

Subtotal 702 91

Accordingly, when the various project applications were

made by Cone and Long, the required assurance against

racial discrimination was waived by the Medical Care

1 2

Commission and this was approved by the Surgeon Gen

eral.13 *

Federal funds under the program are paid by the United

States to the Treasurer of the State of North Carolina,

and are disbursed by him to the hospital (I lia ) .

D. Division of Federal and ,State Controls

The overall plan of the Hill-Burton program reflects a

division of power and responsibility between federal and

state governments for control and supervision of various

matters affecting participating hospitals. The following

description of the statutory and regulatory framework ap

plicable to defendant hospitals, divides the provisions into

seven categories: (1) controls over construction contracts

and the construction period; (2) controls over details of

hospital construction and equipment; (3) controls over

future operation and status of hospitals; (4) controls over

details of hospital maintenance and operation; (5) control

of size and distribution of facilities; (6) rights of project

applicants and state agencies; and (7) regulation of racial

discrimination. The following is designed to enumerate

and describe the statutes and regulations which are too

lengthy conveniently to be set out in full.

1. Controls over construction contracts and the con

struction period. (Federally imposed rules.)

13 On Projects NC-86 and NC-330, the Cone Hospital initially gave an

assurance of nondiscrimination, but this was withdrawn with the approval of

the Medical Care Commission and the Surgeon General, on the ground that

“ the non-discrimination agreement was erroneously executed as a result of

clerical inadvertence” for which the Commission was responsible (104a-106a,

201a-202a).

13

The Surgeon General is authorized by 42 U. S. C. §291h

(a) to enforce certain requirements. Applicable regulations

are in 42 C. F. R. §§53.127(c) ( l) - (9 ) ,14 and in §53.128.15

2. Control over details of hospital construction and

equipment. (Detailed federal minimum standards, and al

lowance for States to impose higher standards.)

The Act authorizes the Surgeon General to prescribe

“ General standards of construction of hospitals and equip

ment for hospitals of different classes and different types

of location” (42 U. S. C., §291e(e)). The Surgeon General

has adopted such regulations— Subpart M' of the Public

Health Service Regulations, “ General Standards of Con

struction and Equipment” (42 C. F. R. §§53.131 to 53.155).

He has provided that plans and specifications for each

project must be in accord with them (42 C. F. R. §§53.101,

53.127(d) (2 )), and that state agencies must adopt standards

“not less than” the federal standards (42 C. F. R. §53.125).

North Carolina’s State Plan adopts the federal standards

as its minimum standards (llO a-llla ). North Carolina’s

additional standards for hospital physical facilities are

section VI of the licensing regulations (145a-156a), as well

as the Building Code and local municipal codes (145a).

14 To briefly summarize the requirements, hospitals must give assurances

that: (1) “ fixed price” construction contracts will be used, with competitive

bidding and awards to the lowest responsible bidder; (2) construction laborers

will be paid federally prescribed minimum wages; (3) contracts will provide

against “kickbacks” ; (4) bidding advertisements will await the Surgeon

General’s approval of final drawings and specifications; (5) Surgeon General

must approve of any contracts in excess of approved costs; (6) contractors

agree to furnish performance bonds and insurance; (7) contract changes

increasing costs must be approved by Surgeon General; (8) Surgeon General

and State agency will have access to inspect work during progress; and (9)

competent architects and engineers supervise construction work.

15 This provision governs the details of installment payments and pro

vides for State agency inspection of work and certification that federal pay

ments are due.

14

Special requirements relate to submission of plans and

locations for projects assisted with federal and state funds

under the licensing rules (145a-146a).

The federal construction and equipment standards are

designed “ to insure properly planned and well constructed

hospital . . . which can be maintained and efficiently op

erated to furnish adequate service” (42 C. F. R. §53.131).16

3. Control of future status and operations of hospitals.

(Federal requirements.)

The Act provides that if within 20 years after completion

of a project a hospital is sold to anyone who is not qualified

to file an application under the Act or is not approved by

the State agency, or if the hospital ceases to be “non

profit,” the United States can recover a proportionate share

of its grant to the hospital (42 U. S. C., §291h(e)). The

State agency is required to give notice of any such changes

of status (42 C. F. R. §53.130).

In addition, the State agency is required to certify that

an application “ contains reasonable assurance as to title,

payment of prevailing rates of wages, and financial support

for the non-federal share of the cost of construction and the

16 The federal standards of Subpart M are so detailed that they ean he

described here only in very general terms as regulating hospital sites, the

departments required in hospitals and the type of facilities to be available

in each department, and other requirements for all hospitals. There is de

tailed description of the types, sizes, locations, contents, arrangements, equip

ment and other characteristics of almost every hospital area. To illustrate the

detail, in all hospitals there are required door widths, corridor widths, stair

widths, elevator standards, and rules pertaining to laundry chutes, nurses call

systems, fire safety, ray protection, radioisotopes, x-ray equipment, ceiling

heights, insulation, parking space, and floor, wall, and ceiling finishes (42

C. F. R. 5553.150(a), 53.151). See the detailed regulation of each general

hospital department, 42 C. F. R. 553.134.

Hospitals must also submit complete equipment lists with their project ap

plications for approval by the state and federal agencies. Abstracts of these

lists are in the project applications in the record (Exhibits A, B, C, D, E, to

plaintiffs’ Motion for Summary Judgment).

15

entire cost of maintenance and operation when completed”

(42 C. F. R. §53,127(d) (1)). The regulation requires that

hospitals submit proposed operating budgets and other

financial data relating to the two year period following

completion of a project “ to assure the availability of funds

for maintenance and operation” (Id.).

4. Control over details of hospital maintenance and ope

ration. (State control of operations required by federal

law.)

The Hill-Burton Act has a provision entitled “ State

control of operations” which denies federal officers “ the

right to exercise any supervision or control over the ad

ministration, personnel, maintenance, or operation” of

facilities receiving grants, “ except as otherwise provided”

(42 U. S. C. §291m).17 But, the Act says that State Plans

must “provide minimum standards (to be fixed in the dis

cretion of the State) for the maintenance and operation of

hospitals which receive Federal aid . . . ” (42 U. S. C.

§291f(a)(7)). No federal grants may be allotted to any

state which does not enact “ legislation providing that com

pliance with minimum standards of maintenance and opera

tion shall be required . . . ” (42 U. S. C. §291f(d)). Federal

regulations require the State agency to certify that each

project application “ contains an assurance that the ap

plicant will conform to the State standards for operation

and maintenance . . . ” (42 C. F. R. §53.127(d) (5)).

Accordingly after the passage of the Hill-Burton Act

North Carolina enacted a “Hospital Licensing Act” in 1947,

(N. C. Gen. Stats. §131-126.1 et seq.) authorizing the adop

tion of detailed requirements governing hospital main-

17 Another slightly different provision, 42 TJ. S. C. §292g, relates only to

research facilities aided under another law (“ The Health Research Facilities

Act of 1956” ; 42 U. S. C, §292 et seq.) and does not apply to hospitals under

Hill-Burton.

16

tenance and operation. The standards adopted are in the

“ Rules and Regulations for Hospital Licensure” (122a-

157a). The Hill-Burton Act set an initial deadline of July

1, 1948, for states wishing to participate to enact such

requirements (42 TJ. S. C. §291f(d)), and North Carolina

enacted its Licensing Act in 1947 (Session Laws of N. C.,

1947, c. 933; N. C. Gen. Stats. §131-126.1 et seq.). The

North Carolina rules (122a-157a) provide in great detail

for the management and operation of hospitals, covering a

variety of subjects, including as major categories: Ad

ministration, Clinical Services, Auxiliary Services, Nursing

Service, and Food Service (122a-145a).18

5. Size and distribution of facilities. (Federal and State

control.)

The Act provides for federal decision as to the number

of general hospital beds and other facilities required to

provide “ adequate service” in a State, for general methods

of distribution in areas of a State, and for the general

manner in which a State agency shall determine priorities

of projects based on relative need (42 TJ. S. C. §291e(a) (b)-

(c )(d )) . State allowances in terms of number of beds per

thousand population have been fixed by regulation (42

C. F. R. §53.11), as have the methods to be used by State

agencies in distributing hospitals in a State (42 C. F. R.

18 For example, the rules provide among other things for medical staff

organization (123a); standards for facilities, organization and procedures in

surgical operating rooms (125a-126a) ; equipment organization and pro

cedures for the obstetric department (126a-131a); for separation of pedi

atric facilities from those for adults and the newborn nursing service (132a) ;

the circumstances for administration of anesthesia (132a) ; for clinical patho

logical laboratories and blood tests (133a) ; that hospitals have adequate

diagnostic X-ray and fluoroscopic examination facilities (134a); designated

treatment facilities for emergency or outpatient service (134a); for isolation

rooms (135a); regulation of hospital pharmacies (135a-136a) and records

(136a-138a); organization of the nursing staff is described, including mini

mum numbers (138-139a); and detailed provision for hospital food service

is made (139a-145a).

17

§§53.12, 53.13). The “ separate but equal” provisions stipu

lates that facilities for separate population groups not be

programmed for construction “beyond the level of adequacy

for such group” (42 C. F. R. §53.112). Federal standards

governing the state agencies’ determination of the priority

of projects are set out in 42 C. F. R. §§53.71 to 53.80. See

also 42 C. F. R. §53.127(b), and 42 C. F. R. §53.127(d) (6).

6. Rights of project applicants and State Agency. (Fed

eral requirements.)

A project applicant is granted the right to “ a fair hear

ing before the State agency” if “dissatisfied with any action

of the State agency regarding its application” (42 C. F. R.

§53.124; see 42 U. S. C. §291f(a)(8)).

The Act provides that before the Surgeon General may

withhold certification of any project, the State agency shall

be accorded a hearing by the Surgeon General (42 U. S. C.

§291j). A State agency dissatisfied with action of the Sur

geon General on a project application may obtain review

of his decision in the United States Court of Appeals for

the Circuit, and may seek further review in the Supreme

Court of the United States (42 U. S. C. §291j).

7. Regulation of racial discrimination. (General federal

requirement; States allowed to plan racial separation as

exception.)

The Hill-Burton Act prohibits racial discrimination in

general terms, providing that State Plans “ shall provide

for adequate hospital facilities for the people residing in

a State without discrimination on account of race, creed or

color” (42 U. S. C. §291e(f); see note 1, supra). Both

state plans (42 U. S. C. §291f(a)(4) (D)) and project appli

cations (42 U. S. C. §291h(a) are subject to the non

18

discrimination requirement. The parallel regulations are

42 C. F. E. §§53.111, 53.127(d)(4).

However, the Act authorizes the Surgeon General to

make regulations permitting State Plans to provide an

exception to the racial nondiscrimination rule by establish

ing separate hospital facilities for separate population

groups if there is “ equitable provision” for each group

(42 U. S. C. §291e(f)). The Surgeon General has promul

gated such a regulation (42 C. F. R. §53.112), which stipu

lates that the State agency may waive assurances of non

discrimination from a hospital if the State Plan otherwise

makes equitable provision for each group, and this finding

is approved by the Surgeon General. It also includes the

Surgeon General’s standard for determining if “ equitable

provision” is made for such groups (Id.).

The Training of State Nursing School Students at Cone

Cone Hospital’s charter includes as one corporate purpose

“ the training of nurses, and the giving and receiving of

instructions . . . ” (47a-48a). Cone Hospital participates in

a nurses training program with two tax supported state

schools, The Woman’s College of the University of North

Carolina and the Agricultural and Technical College of

North Carolina (an all Negro school). Student nurses at

the schools receive part of their training at Cone Hospital

(55a-57a).

Students carry out assignments at the hospital under the

supervision of their teachers, including assisting doctors

and nurses, treating patients, keeping hospital records, etc.

Woman’s College students work periods as full-time ap

prentice nurses paid at 3/4ths of beginning nurses pay

(57a). Students’ programs are arranged by their teachers

but cleared with the hospital (56a).

19

The hospital subsidizes the meals and laundry of the

A&T College students. It provides conference and instruc

tional rooms without charge (56a).

Cone authorized a grant of $100,000 to underwrite the

entire cost of the Woman’s College clinical nursing program

from 1957 to 1960, and actually paid $86,835.13 under this

grant. For the 1960-61 program, the hospital paid $20,000.

For the period 1961-1963 Cone paid $25,000; it had an equal

amount still available for the period. Cone also gave $10,500

for student scholarship loans for the Woman’s College nurs

ing program (57a-58a). The A&T program has cost the

hospital $3,337.59 for meal and laundry subsidies since

1954 (56a).

The program is beneficial to both colleges, providing

clinical experience deemed essential for student nurses.

According to the Cone Hospital Director, Cone “ . . . is

interested in and has supported both programs as a public

service and in order to foster and to reap the intangible

benefits to be derived from the creation of sources of well-

trained nurses . . . ” , but has “ no priority to employ any

nurses graduating in either program . . . ” (59a).

Because of the scarcity of nurses in North Carolina the

State Commission gives “high priority on its funds” to

expanding nurses training facilities for hospitals (116a-

119a). Throughout the nation hospitals perform similar

educational functions, and “ teaching hospitals are generally

regarded as providing, by and large, the highest quality of

care. . . . Although student services are availed of by the

hospitals in varying degree, these educational activities

incur substantial net deficits which are generally recouped

by charging paying patients somewhat more than the im

mediate cost of services to them.” (Affidavit of Mr. Allison

W illeox; 177a).

20

A R G U M E N T

U

The Appellees5 Contacts With Government Are Suffi

cient to Place Them Under the Restraints of the Fifth

and Fourteenth Amendments Against Racial Discrimina

tion.

Decisions of the United States Supreme Court leave

little doubt that governmental action as broad, significant,

and effective as that found in this case results in the ap

plication of the restraints against racial discrimination of

the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment19 and the

due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment.20 Racial discrimination is constitutional only

when “unsupported by State authority in the shape of laws,

customs, or judicial, or executive proceedings” or when

“ not sanctioned in some way by the State.” 19 20 21 Discrimina

tion is forbidden when the State participates “ through any

arrangement, management, funds or property” 22 or when

the State places its “power, property or prestige” behind

the discrimination.23

z In this case racial segregation, which repeatedly has been

held to constitute discrimination per se since Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483,24 is explicitly authorized

19 Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497; Eirabayashi V. United States, 320

IT. S. 81, 100.

20 Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U. S. 1, 19.

21 Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 17.

22 Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT. S. 1, 4, 19.

23 Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715, 725.

24 See

2 1

by a federal statute25 26 27 antedating Brown. The discrimina-

been approved by agencies and officials

and the United States .413a,

‘-126a). Large amounts of public funds have been expended

by government to support the hospitals practicing dis

crimination. The hospitals have submitted to a compre

hensive pattern of sfgte and federal controls in return for

these funds.** has granted these hospitals

the power to operate and the privilege of receiving federal

aid. The hospitals are aided by the State because they

fulfill a public function which the State would have to per

form if the hospitals did not.1*7 Xn^^addltion’j—as,-r'tO'-’Uone

Hosprtahr-the-'Stat-e'4ias.-.passedUogisla-tion''diret;tiHg“pTtblic

official? to appoint members of its governing board and has

chosen to- train students, enrolled at public colleges at

Gottk*8"'"

Financial Contributions.

The Cone and Long Hospitals are the beneficiaries of

approximately 1.2 and 1.9 million dollars, respectively, paid

to them through the Treasurer of the State of North Caro

lina, from the United States of America under the Hill-

Burton program. Although the District Court found the

amount “ substantial” (213a), it deemed “ control rather than

contribution . . . the decisive factor” (217a), and found

receipt of these funds from government constitutionally

insignificant.

Control, however, has never been more than one factor

which the courts have employed to evaluate the “ totality” 29

25 42 U. S. 0., §291e(f) ; 42 C. F. B., 553-112.

26 See supra, pp. 12-18 (97a, 103a).

27 .See infra, pp. 28-31.

28 See supra, pp. 7, 18-19.

29 Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 XT. S. 715, 722-725.

2 2

of governmental relationships with persons and institutions

for the purposes of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.

Indeed, many cases dealing with the issue have not found

control by government necessary in order to result in gov

ernmental responsibility.30 If any generalization suffices, it

might be said that where governmental action, whatever

its form, significantly affects conduct in the “ private”

sphere, the restraints of the Constitution apply to forbid

racial discrimination. Burton v. Wilmington Parking Au

thority, 365 U. S. 715; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 4.

The present case does include massive governmental con

trol over the defendant hospitals, as is urged below. How

ever, appellants submit that the effect of government as

sistance upon an otherwise “private” entity is highly rele

vant in deciding whether the restraints of the Constitution

should apply.31 The conclusion of the District Court that

the effect of three million dollars of public funds on the

hospitals was insignificant for purposes of the Fifth and

30 There was no control o f the “ private” activity in Burton v. Wilmington

ParMng Authority, 365 TJ. S. 715, 723, 724, or in many of the public accom

modation eases involving use of governmental property which preceded it.

See 365 TJ. S. at 925, n. 2. Indeed, many of these cases expressly assumed

the absence of “ control.” See, e.g., Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922

(5th Cir. 1956), cert. den. sub nom. Casey v. Plummer, 353 TJ. S. 924. Where

property has a governmental character, Marsh v. Alabama, 326 TJ. S. 501, or

where it is used for the public benefit, Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280

F. 2d 531, 535, government is responsible without inquiry as to control. A

state is responsible even though the acts of its agents are not controlled or

even permitted by state law. Monroe v. Pape, 365 TJ. S. 167; United States

v. Baines, 362 TJ. S. 17, 25. The same is true when government delegates

(Nixon v. Condon, 287 TJ. S. 73), authorizes (Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S.

649) or acquiesces in ( Terry v. Adams, 345 TJ. S. 461), the exereise of essen

tially governmental functions by private bodies. As said in Burton, supra, at p.

722, the Supreme Court has never attempted “ to fashion and apply a precise

formula for recognition of state responsibility under the Equal Protection

Clause.”

31 This is apart from the possibility that the amount of the contribution

can result in control. Cf. Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library, 170 F. 2d 212

(4th Cir. 1945).

23

Fourteenth is, in appellants’ view, erroneous. Prior to

receipt of Hill-Burton assistance, Long Hospital operated

a 78 bed hospital considered “ obsolete” by North Carolina

(160a) and “ unsuitable” by the United States (93a). Long

has now constructed and operates a 220 bed modern gen

eral hospital, a nurses training school and a $120,000.00

laundry constructed under Hill-Burton with fifty percent

federal funds. Cone Hospital has completed construction of

a 300 bed hospital, a 182. bed hospital addition, and a diag

nostic and treatment center with the assistance of the

State of North Carolina and the United States under the

Hill-Burton Program. g

|5 i tJ ‘ V . ^ uTheses federal grants in excess of %, million dollars to '

Aaeh hospital, distributed in accordance with state and

federal priorities and plans, » e obviously substantial. ‘She- 1 r y

tax exempt status of the hospitals’ property increases the

financial subsidy, cf. Burton v. Wilmington Parking Au

thority, 365 U. S. 715, 724; cf. also Allen v. County School

Board of Prince Edward County, 198 F. Supp. 497, 503

(E. D. Va. 1961), appeal pending. Thus, there is govern

mental participation through an “ arrangement,” “ funds,”

and “ property,” calling for application of constitutional

principles against discrimination. Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U. S. 1, 4, 19. It would be difficult to know what the Cooper

v. Aaron principle can i|Lean, if it does not embrace con

tributions of funds in the million dollar range to build tax

exempt property.

State and Federal Controls to Implement Public Policy.

In addition to the contribution of public funds, these

hospitals are subject to a variety of governmental controls

by virtue of their participation in the federal-state hospital

construction program. The character of the physical facili

ties and the equipment of the hospitals is closely controlled

24

by both federal and state governments.32 The effect of this

regulation of construction and equipment on the future

operations of the hospital is manifest. Requiring that a

hospital build and arrange a particular department in a

certain way and obtain certain equipment obviously deter

mines the character of the service the hospital will render

in the future. Beyond this, the federal statute requires

that the states must directly regulate the details of hospi

tal maintenance and operation. In order to participate in

the Hill-Burton Program North Carolina has undertaken

an elaborate regulatory and licensing scheme.33 This state

control over the defendant hospitals’ operations is exact and

detailed. In addition, the Federal Government exercises

control over the general status of hospitals for a twenty

year period.34

-f^Tlio funds paid to these hospitals under the Hill-Burton

Act are to be used solely for carrying out the project as

approved by the State and Surgeon General.35 If the hos

pitals sell or transfer ownership within twenty years to

anyone not qualified under the Act to apply for funds or

not approved by the state agency, or if the hospitals cease

to be “ nonprofit” the United States is authorized to recover

the present value of the federal share of the approved

project.36 These provisions operate to insure against mis

use of federal funds in the manner of a reverter retained

by government to insure particular use of property. The

Fifth Circuit has found retention of such an interest in

property sold by a municipality to private persons suffi

cient to invoke constitutional restraints. In Hampton v.

32 See Statement of Facts, supra, pp. 13-14.

33 See Statement of Facts, supra, pp. 15-16.

34 See Statement of Facts, supra, at pp. 14-15.

35 42 U. S. C., §2911i (d).

36 42 U. S. C., §291h(e).

2 5

City of Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320 (5th Cir. 1962), cert. den.

sub nom. Ghioto v. Hampton, 9 L. ed. 2d 170, the City sold

two municipal golf courses with the deeds providing that

the City would regain title if the properties were used for

other purposes. This was the only connection retained by

the City. Chief Judge Tuttle found that “ conceptually it

is extremely difficult if not impossible to find any rational

basis of distinguishing the power or degree of control, so

far as relates to the State’s involvement between a long

term lease for a particular purpose with the right of can

cellation . . . if that purpose is not carried out” (as in

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715),

“ and an absolute conveyance of property subject . . . to the

right of reversion if property does not continue to be used

for the purpose prescribed” (304 F. 2d at 322). On this

reasoning the Fifth Circuit declined to follow this Court’s

decision in Eaton v. Board of Managers of the James

Walker Memorial Hospital, 261 F. 2d 521 (4th Cir. 1958),

cert. den. 359 IT. S. 984,87 saying that as Eaton was decided

prior to Burton, its holding probably would not be adhered

to in this Court^J

Appellants submit that the interest retained by Govern

ment in these hospitals pursuant to 42 IT. S. C., §291h(e),

for a 20 year period is a substantial factor supporting the 37

37 Eaton does not control this case. In Eaton all governmental aid in the

construction of facilities ceased in 1901; neither the district court nor this

Court’s opinions so much as mentions assistance received from the federal

government; the hospital in Eaton was not part of a State Plan for hospital

construction and expansion nor did it have to conform to the requirements

and standards of the Hill-Burton Act; those resources it did receive from

government, for the treatment of indigent patients, amounted to 4.5 percent

of the hospital’s total income; no governmental appointees sat on the Board

of the hospital in Eaton nor did it participate in any arrangement with state

educational institutions; while the hospital was licensed, the North Carolina

Licensing process and its relation to the Hill-Burton program was not argued

before this Court or discussed in its opinion; finally, segregation was not pur

suant to authorization of federal law.

2 6

conclusions that these hospitals are subject to the Four

teenth Amendment. Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, supra.

The court below distinguished Burton v. Wilmington

Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715, which held discrimination

forbidden at a restaurant on property leased by Govern

ment without retaining any control of the restaurant opera

tion, on the ground that the instant case involved no

leasing of government property. But there is nothing

talismanic about a leasing arrangement as such, for the

Fourteenth Amendment is concerned with the effect of

governmental action rather than with its form. In Burton

the Court did not rely solely upon the fact that the dis

crimination occurred on government property leased to a

private persons but based its decision upon the effect of

the totality of governmental participation. The Burton

opinion cited decisions of this and other appellate courts

based upon the leasing of governmental property38 but did

not adopt this as its sole ground of decision. Nor does the

fact that property is privately owned render it immune

from the restrictions of the Fourteenth Amendment. Cf.

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U. S. 1; Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750, 754, 755 (5th

Cir. 1961); and see note 42, infra.

Because of the control exercised by government over

these hospitals, the principle enunciated in Public Utilities

Comm’n v. Poliak, 343 U. S. 451, 462, applies. There the

Supreme Court found sufficient governmental responsibility

to require decision of a Fifth Amendment due process

claim where the principal governmental involvement was

a decision by a regulatory body to do nothing about private

activity (radio broadcasts on streetcars) it could have

prohibited. The hospitals in this case are regulated by

38 365 U. S. at 725, n. 2.

27

government in as significant a degree as the transit com

pany was in Poliak. And this case has elements that the

Poliak case did not, e.g., financial support and statutory

authorization of racial segregation among others.

The hospitals in this case are also like the certified

labor unions required to represent all persons within a

particular bargaining unit without discrimination. As labor

organizations receive substantial power and benefits by

having been licensed and regulated under federal law, the

Supreme Court has found that serious Fifth Amendment

due process questions would arise if the federal statutes

involved were not construed to require nondiscrimination.39

The hospitals here are licensed and controlled by govern

ment and have received substantial benefits under a com

prehensive federal scheme for regulation of an area of

national importance to much the same extent as labor

organizations.

? In rejecting . .the significance of the licensing process

whereby North' î rpolina grants these hospitals the power

to operate after insuring compliance with comprehensive

standards of operation, the District Court found the licenses

granted these hospitals no different from those granted

facilities such as restaurants. But licenses are distinguished

on the basis of the power they grant and the purpose for

which they are granted. See Bomcm v. Birmingham Transit

39 Steele v. Louisville N. B.B. Co., 323 U. S. 192 (Railway Labor Act) ;

Syres v. Oil Workers Int’l Union, 223 F. 2d 739 (5th Cir. 1955), rev’d per

curiam, 350 U. S. 892 (Labor Management Relations A c t ) ; Bailway Em

ployees Dept. v. Hanson, 351 U. S. 225, 232, n. 4. In Railroad Trainmen v.

Howard, 343 U. S. 768, Negroes in a separate bargaining unit were entitled

to enjoin a white union from striking to eliminate the Negroes’ jobs. See,

Betts v. Easley, 161 Ean. 459, 169 P. 2d 831 (holding certified labor union

with responsibilities under federal law and receiving benefits therefrom sub

ject to Constitution). Cf. Ming v. Horgan, 3 Race Rel. L. Rev. 693, 699

(Cal. Super. Ct. 1958) (persons accepting federal mortgage guarantee bound

by Fifth Amendment).

2 8

Co., 280 F. 2d 531, 535 (5th Cir. 1960), holding that because

a bus company was performing a service for the public

necessity and convenience, by having a franchise to operate

on the public streets of Birmingham, “ the acts of the bus

company in requiring racially segregated seating were

‘state acts.’ ” 40 These hospitals perform services for the

public at least as significant as those of a local bus com-

panyJfAs stated by the General Counsel of the Department

of Health, Education, and Welfare, “ [T]he Hill-Burton

Act recognizes the interchangeability of public and non

profit community hospitals and aids the two on the same

terms, leaving the choice in each individual case to the

community and the state. The State Plan must be ad

dressed to the provision of adequate facilities for all of

the people of the State, but effectuation of the plan may

be through any combination of public and nonprofit in

stitutions” (179a-180a).

It would be totally misleading to consider these hospitals

on the same footing as an ordinary licensed private busi

ness. In order to receive Hill-Burton funds the hospitals

must be nonprofit “ community facilities” defined as fur

nishing service to the general public with admission limited

only on the basis of age, medical, indigency, or mental

disability.41 Cone Hospital is chartered on the condition

that “no patient shall be refused admission nor be dis

charged because of inability to pay” (50a), and the Board’s

power to decide who shall be admitted is conferred in terms

of “ classes of patients, as regards diseases” (49a). Long

Hospital was formed “ to serve the public and the com

munity” (61a). Not only do nonprofit hospitals like Cone

40 See also, Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750, 755 (5th Cir. 1961) ; Betts

if. Easley, 161 Kan. 459, 169 P. 2d 831.

41 42 C. F. R., §53.1 (v).

29

and Long perform “ the same community functions” as

public hospitals, “ but they do so in the same way and with

the same relationships to their patients and to the prac

ticing profession. They enjoy substantially the same free

dom from taxation and offer the same or similar support

from public funds. Such differences as there may be in

the make-up of the governing boards or in the financial

structure are all but invisible to patients or to physicians”

(179a).

Over 85% of the “ acceptable” hospital beds (702 of 793

beds) in the Greensboro area are at Long and Cone Hos

pitals ; the remaining 91 beds are at the all-Negro L.

Richardson Memorial Hospital (120a).

Under Hill-Burton, the number and distribution of hos

pital beds in an area is decided by State and Federal

Governments. Once funds are granted bringing an area

up to the standard of hospital beds considered adequate

for the population, no further beds can be programmed.

(See Statement of Facts, supra, pp. 16-17.) If North Caro

lina had chosen to build publicly owned hospitals in Greens

boro, Cone and Long could have been denied all federal

aid. On the other hand, the aid granted them now prohibits

the construction of duplicating city, county, or other non

profit facilities with federal aid. The participating hos

pitals have become the chosen and exclusive instruments

to carry out governmental objectives.

In such a community these hospitals are performing an

essential governmental function for the State. If the State

did not provide for this service indirectly by control and

support of defendants, it would necessarily have to provide

the service directly through operation of a public hospital.

Though privately owned, they are essential community

facilities, operated for the benefit of the general public, in

relation to which the constitutional principle of Marsh v.

30

Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, 50642 (that facilities “ built and

operated primarily to benefit the public” are circumscribed

by the constitutional rights of the public) must be applied.

Nonprofit community hospitals such as Long and Cone

are fundamentally different from “ private” profit making

hospitals which are “ essentially business undertakings” and

ineligible for Hill-Burton assistance (178a). As part of a

State Plan the purpose of which is to afford “ necessary

physical facilities for furnishing adequate hospital, clinic

and similar services to all [the] people,” 43 Long and Cone

are doing something state and federal governments deem

“useful for the public necessity or convenience” , Boman

v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 P. 2d 531, 535 (5th Cir.

1960) ; Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750, 755 (5th Cir.

1961) . It is because of this public responsibility that they

have received governmental support,44 and they are in-

42 “ Ownership does not always mean absolute dominion. The more an

owner, for his advantage, opens up his property for use by the public in

general, the more do his rights become circumscribed by the statutory and

constitutional rights of those who use it. . . . ” Marsh has been specifically

applied to the equal protection clause. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 22.

Cf. Republic Aviation Corp. v. N.L.R.B., 324 TX. S. 793, 798, 802, n. 8;

N.L.R.B. v. Babcock <$■ Wilcox Co., 351 XI. S. 105, 112; Freeman v. Retail

Clerks Local, 1207, 45 Lab. Eel. Eef. Man. 2334 (1959), all eases applying

the Marsh principle to private property.

43 42 TJ. S. C., §291.

44 The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare has stated the

philosophy of Hill-Burton to be “ assistance of nonpublic groups, for public

ends” :

“ The underlying social philosophy of the program under Title VI of

the Public Health Service Act is that the health of the Nation is a

national resource and that Federal leadership and financial encourage

ment are warranted and necessary in establishing a systematic network

of facilities for hospital and medical facilities. For this purpose, com

prehensive planning by the States themselves is regarded as essential,

based on careful inventories of existing facilities, while local initiative

and local financing must launch specific projects in accordance with the

State Plan, i f Federal assistance is to be provided.

“ No distinction is made between public and private sponsors of projects

aided, provided personal gain or profit from the operation of the hospital

3 1

struments of government policy within the Fifth and Four

teenth Amendments. Bomrni v. Birmingham Transit Co.,

supra; Baldwins. Morgan', supra.

Affirmative Governmental Sanction of Discrimination.

In addition to the interrelations of the hospitals with

government discussed above, an additional factor compels

the conclusion that the discrimination practiced against ap

pellants is within the purview of the Constitution. This

discrimination was affirmatively sanctioned by a federal

statute and federal regulations, and by a State Plan for

hospital construction on a segregated basis. The conduct

of private persons is insulated from constitutional require

ments only insofar as it is “unsupported by State author

ity in the shape of laws, customs, or judicial or executive

proceedings” or is “not sanctioned in some way by the

State.” Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 17. Here the af

firmative governmental sanction of racial segregation (the

State Plan for segregation in the Greensboro area) en

ables the hospitals to avoid giving an assurance not to

discriminate as a condition of receiving the funds. This is

in accord with the Hill-Burton Act (42 U. S. C. §291e(f))

which allows the States to authorize or require segregation

in either government hospitals or nonprofit hospitals. The

segregation is supported by federal statute and regulations

and by State executive decisions, e.g., the State Plan.

The principle enunciated in Mr. Justice Stewart’s con

curring opinion in Burton v. Wilmington Parking Author-

is not involved. This is believed to be the first major example of Federal

assistance to nonpublic groups, for public ends. Such action was found

essential to a comprehensive program, because of the dual nature of the

entire existing hospital system, which had evolved to a large degree under

private auspices.” The Nation’s Health Facilities: Ten Years of the Hill-

Burton Program 1946-1956, p. 15, Public Health Service Publication No.

616 (1958).

32

ity, 365 U. S. 715, 726-727, justifies the grant of relief to

appellants here. In Burton, Justice Stewart read the Dela

ware law as “ authorizing discriminatory classification based

exclusively on color” (365 U. S. at 727) and found this

sufficient to invalidate the law and reverse a decision deny

ing an injunction against a restaurateur who excluded

Negroes. Three dissenters (Justices Frankfurter, Harlan

and Whittaker) agreed that a statute authorizing a non

governmental entity to discriminate would “ indubitably”

(365 U. S. at 727) and “certainly” (Id. at 730) offend the

Fourteenth Amendment and open up an “ easy route to

decision” (Id. at 728). But they found the meaning of the

Delaware law uncertain. The majority opinion in Burton

did not discuss the issue. However, McCabe v. Atchison

Topeka and S. F. R. Co., 235 U. S. 151, 162 (1914), is based

upon the same theory, holding that a Negro “might properly

complain that his constitutional privilege has been invaded”

if common carriers “ acting in the matter under the authority

of a state law” denied Negroes sleeping car, dining car and