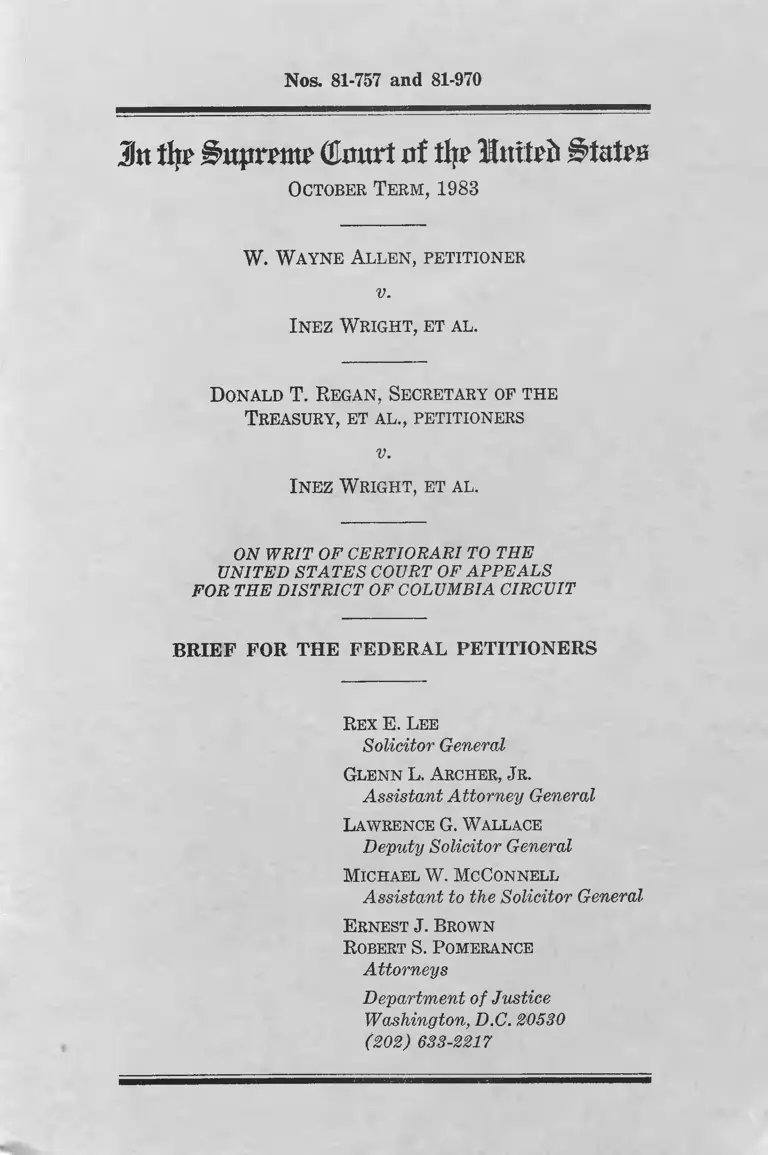

Allen v. Wright and Regan v. Wright Brief for the Federal Petitioners

Public Court Documents

September 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Allen v. Wright and Regan v. Wright Brief for the Federal Petitioners, 1983. af6e9898-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a216b129-8fcb-4b7c-acb1-d5324b5ddccc/allen-v-wright-and-regan-v-wright-brief-for-the-federal-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

N os, 81-757 and 81-970

Jtt % Bnpnm ( to rt nt % Uttiteft States

October T e r m , 1983

W. W a y n e Al l e n , pe titio n e r

v.

I n e z W r ig h t , et a l .

D onald T. R ega n , Secretary of t h e

T reasury , et a l ., petitio n er s

v.

I n e z W r ig h t , et a l .

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE FEDERAL PETITIONERS

Rex E. Lee

Solicitor General

Glen n L. Archer, J r.

Assistant Attorney General

Lawrence G. Wallace

Deputy Solicitor General

Michael W. McConnell

Assistant to the Solicitor General

E rnest J. Brown

R obert S. P omerance

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 633-2217

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether federal courts may entertain equity suits

against the Secretary of the Treasury brought by par

ents of black children in public schools seeking to have

the Treasury revise the guidelines and procedures it uses

to enforce the prohibition on tax exempt status for ra

cially discriminatory private schools, where they do not

allege discrimination or any other distinct injury to

themselves or their children by any private school or by

the Treasury.

( i )

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Opinions below..................... 2

Jurisdiction .................................................................. 3

Constitutional provisions, statutes and regulations

involved ..................................-................................. 3

Statement:

A. Background .................................... 3

B. The proceedings in this case.......................... - 9

Summary of argument ............ 17

Argument:

I. Respondents lack standing to challenge Treasury

guidelines and procedures that have been sub

ject to executive and legislative review and re

sult in no concrete injury to them --------------- 19

II. Respondents’ allegations of injury establish no

direct and concrete injury caused by the govern

ment’s actions and redressible by the courts--- 24

A. Respondents’ allegation that the government

provides tangible aid to racially segregated

institutions establishes no “injury in fact,”

but only a generalized grievance with gov

ernment conduct ...... ................. ................ 24

B. Respondents’ allegation that government en

couragement of racially segregated educa

tional opportunities interferes with public

school desegregation does not establish an

injury fairly traceable to government action

and redressible in court .... ...... ........... ..... 31

III. Under the prudential tests for standing estab

lished by this Court, no person not seeking a

tax benefit may challenge the tax treatment of

others ................................... ................... -....... 36

( i n )

IV

Argument—Continued Page

IV. The court of appeals’ holding is not supported

by this Court’s judgments in Norwood, Gilmore,

or Green ........................................................... 43

Conclusion ......... 49

Cases:

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Abortion Rights Mobilization, Inc. V. Regan, 552

F. Supp. 364 .................. ................................. 41

Adams V. Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159 .................... 39

American Jewish Congress v. Vance, 575 F.2d 939.. 15, 30

American Society of Travel Agents, Inc. V. Blu-

menthal, 566 F.2d 145, cert, denied, 435 U.S.

947 ............................................... ............. . 15,41

Arlington Heights V. Metropolitan Housing De

velopment Corp., 429 U.S. 252 ___ ____ ____ 34

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 ............ ................ ..... 22, 25

Blum V. Yaretsky, No. 80-1952 (June 25, 1982).... 25

Bob Jones University v. Simon, 416 U.S. 725 ....18, 40, 48

Bob Jones University v. United States, Nos. 81-3

and 81-1 (May 24, 1983) ................4, 19, 28, 29, 37, 43

Cattle Feeders Tax Committee V. Shultz, 504 F.2d

462 .......................................................... .............. . 41

Coit V. Green, 404 U.S. 997, aff’g Green v. Con-

natty, 330 F. Supp, 1150 ......... ..........15,18, 43, 44, 47

Connecticut V. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 ........... ............. 28

Educo, Inc. V. Alexander, 557 F.2d 617 ............ . 41

Enochs V. Williams Packing Co., 370 U.S. 1 ___ 40

Fairchild v. Hughes, 258 U.S. 126 _____ _____ 25

Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83 ............................... .26, 28, 29

Flora V. United States, 362 U.S. 145 ................... 40

Frothingham v. Mellon, 262 U.S. 447 .... ..... .... . 36

Fusari v. Steinberg, 419 U.S. 379 ...... ................ 48

Gilmore V. City of Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556-15, 16,18,

43, 44, 45, 48

Gladstone, Realtors V. Village of Bellwood, 441

U.S. 91 ........ ...... .......... ........... ....17,19,25,36,40,43

Green v. Kennedy, 309 F. Supp. 1127, appeal d is

m is se d s u b n o m . Cannon V. Green, 398 U.S. 956.. 47, 48

Cases—Continued

V

Page

Green v. Regan, Civ. Action No. 1355-69 (D.D.C.

May 17, 1977) ........................ ........................ 13

Illinois State Board of Elections V. Socialist Work

ers Party, 440 U.S. 173____ __ __________ _ 47-48

Investment Annuity Inc. V. Blumenthal, 609 F.2d

1, cert, denied, 446 U.S. 981 ............ .............. . 41

Junior Chamber of Commerce V. United States

Jaycees, 495 F.2d 883, cert, denied, 419 U.S.

1026 ........................................ .......................... 41

Laird V. Tatum, 408 U.S. 1 ....... ............ ..........26, 38, 42

Levitt, Ex parte, 302 U.S. 633 ............................ 27

Linda R.S. V. Richard D., 410 U.S. 614 ___ 18, 32, 34, 38

Louisiana V. McAdoo, 234 U.S. 627 ....................18, 37, 39

Lugo V. Miller, 640 F.2d 823 ................................ 41

Mandel v. Bradley, 432 U.S. 173_________ ____ 48

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 ....................... 28

Moose Lodge No. 107 V. Irvis, 407 U.S. 163 .....28, 30, 44

National Muffler Dealers Ass?n v. United States,

440 U.S. 472 .......... ........................... ............. 39

Nomvood V. Harrison, 340 F. Supp. 1003, 413 U.S.

455 .................. ................ .......15, 16, 18, 43, 44, 45, 48

Orr v. Orr, 440 U.S. 268 ______ __________ __ 38

O’Shea V. Littleton, 414 U.S. 488 ______ ______ 25, 30

Prince Edward School Foundation V. Commis

sioner, 478 F. Supp. 107, aff’d by unpublished

order, No. 79-1622 (D.C. Cir. June 30, 1980),

cert, denied, 450 U.S. 944 ................. ............. . 4

Regan v. Taxation With Representation, No. 81-

2338 (May 23, 1983) ................ ....................... 37

Schlesinger v. Reservists Committee to Stop the

War, 418 U.S. 208 __ ___________ 26,29,37,42-43

Sierra Club V. Morton, 405 U.S. 727 .................... 25

Simon v. Eastern Ky. Welfare Rights Organiza

tion, 426 U.S. 26 __________ __ _______ __ passim

Tax Analysts & Advocates V. Blumenthal, 566 F.2d

130, cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1086 ....... ............... 15, 41

United States V. American Friends Service Com

mittee, 419 U.S. 7 ......................................... . 41

United States V. Cornell, 389 U.S. 299 __ _____ 39

United States V. Maryland Savings-Share Insur

ance Co., 400 U.S. 4 37

Cases—Continued

Vi

Page

United States V. Richardson, 418 U.S. 166..27, 29, 38, 42,

43, 46

United States v. SCRAP, 412 U.S. 669 ______25, 37, 46

United States V. Tunica County School District,

323 F. Supp. 1019, aff’d 440 F.2d 337 .............. 45

Valley Forge Christian College V. Americans

United for Separation of Church and State, Inc.,

454 U.S. 464 ............... ...................... ...............passim

Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490.......... 22, 23, 25, 28, 30, 32,

33, 34, 36

Washington V. Seattle School District No. 1, No.

81-9 (June 30, 1982) ....................................... 28

Constitution, statutes, and regulations:

U.S. Const.:

Art. I, § 6, Cl. 2 (Incompatibility Clause) ....26, 27-28

Art. I, § 9, Cl. 7 (Accounts Clause) 27, 28

Art. II, § 3 .................................................. 42

Art. I l l ............ 3,17,22,25,26,31,40,47

Amend. I (Establishment Clause) _______ 27, 37

Amend. V ........ ............ .......... .... ............. . 3

Amend. XIV, § 1 (Equal Protection Clause) ..3, 28, 37

Anti-Injunction Act, 26 U.S.C. (Supp. V)

7421 (a) ................... ................ ................12,15, 39, 41

Declaratory Judgment Act, 28 U.S.C. (Supp. V)

2201 _______________ ___________ 12,13, 15, 40, 41

Federal Insurance Contributions Act, 26 U.S.C.

3121(b)(8)(B) _____ ______ ____ _______ 4

Federal Unemployment Tax Act, 26 U.S.C.

3306(c)(8) ....................................................... 4

Internal Revenue Code of 1954 (26 U.S.C.):

Section 170(a) .............................. ............. 3,43

Section 170 (c) (2) ______________ 3, 4,19, 21, 33

Section 501(a) .............. ...... ................... 3,4

Section 501(c)(3) passim

Section 2055 _________ 4

Section 2522 ____________ 4

Section 6212 (& Supp. V).. ____ 39

Section 6213 (& Supp. V) ......... 39

Section 6532 (& Supp. V) ........................... 39

VII

Constitution, statutes, and regulations—Continued Page

Section 7402 ....... 39

Section 7405 ............. 39

Section 7422 (& Supp. V) ................. 39

Section 7428 (& Supp. V) ...... 39

Section 7476 (& Supp. V)________ 40

Section 7477 .... 40

Section 7478 (Supp. V) __________ 40

Section 7801(a) ................. ....... ......„.... . 39

Section 7805(a) .......................................... . 39

Sections 8001-8023 ________ _____ ______ 39

Section 8021 ..... .................... ..... ............. . 42

Section 8023 ........ .............. ............. ............. 42

Supplemental Appropriations and Rescission Act

of 1981, Pub. L. No. 97-12, Section 401, 95 Stat.

95 .......................................... ......... .............. . 8

Treasury Postal Service, and General Government

Appropriations Act of 1980, Pub. L. No. 96-74,

93 Stat. 559 ...... ........ .......... .................... ........ 8

Section 103, 93 Stat. 562 ...... .............. .......... 3, 8

Section 615, 93 Stat. 577 ...... .... .................... 3, 8

Pub. L. No. 96-536, Section 101(a)(1) and (4),

94 Stat. 3166 __ ____ __________________ 8

Pub. L. No. 97-51, Section 101(a)(3), 95 Stat.

958 .......... .................... ................ ................... 9

Rev. Stat. 1977 (1878 ed.) (42 U.S.C. 1981) ...... 3

28 U.S.C. 1253 ___ _____ ___ _______________ 47

28 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 1346 __ _________ _______ 39

28 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 1491 ....... ...... .... ............ . 39

Rev. Proc. 72-54, 1972-2 Cum. Bull. 834 ........... 5

Rev. Proc. 75-50, 1975-2 Cum. Bull. 587 ..... .3, 5, 6, 9, 12,

20, 21

Section 2.02 .................................... ............ 5

Rev. Rul. 56-185, 1956-1 Cum. Bull. 202 ..... ....... 33

Rev. Rul. 69-545, 1969-2 Cum. Bull. 117 ...... ....... 33, 41

Rev. Rul. 71-447, 1971-2 Cum. Bull. 230 ............. 4, 6

Miscellaneous:

127 Cong. Rec.:

pp. H5392-H5398 (daily ed. July 30, 1981).... 9

pp. H6698-H6699 (daily ed. Sept. 30, 1981).. 9

Miscellaneous—Continued Page

Currie, Misunderstanding Standing, 1981 Sup. Ct.

Rev. 41 ................................. 86

H.R. 4121, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. § 616 (1981) ...... 9

H.R. Rep. No. 96-248, 96th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1979) .................................................... 8,21-22

H.R.J. Res. 644, 96th Cong., 2d Sess. (1980) ___ 8

H.R.J. Res. 325, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981) ...... 9

Tax Exempt Status of Private Schools: Hearings

Before the Subcomm. on Oversight of the House

Comm, on Ways and Means, 96th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1979) ...... 4,6,7

litt % (to rt uf % llmteft

October T e r m , 1983

No. 81-757

W. W a yn e A l l e n , petitio n er

v.

I n ez W r ig h t , et a l .

No. 81-970

D onald T. R egan , Secretary of t h e

T reasury , et a l ., petitio n er s

v.

I n ez W r ig h t , et a l .1

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE FEDERAL PETITIONERS

1 Roscoe L. Egger, Jr., Commissioner of Internal Revenue, is a

petitioner in No. 81-970, in addition to Donald T. Regan, Secretary

of the Treasury.

In addition to Inez Wright, who is a party to this proceeding

individually and on behalf of her minor children, Oscar Clay Renfro,

Anthony Lee Renfro, Lisa Marie Wright, and Ephron Antoni

Wright, Jr., of Memphis, Tennessee, the following persons are also

respondents: Geneva Walker, individually and on behalf of her

minor children, Johnny Ranae Walker and Vincent Calvett Walker,

of Memphis, Tennessee; Delores G. Beamon, individually and on

behalf of her minor children, Rynthia Beamon, Reuben Beamon,

Jr., Cynthia Beamon, and Melvin Beamon, of Montgomery, Ala

bama ; Mary Louise Belser, individually and on behalf of her minor

children, Charlotte. Belser, Connie Belser, Janice Belser, Lawrence

Belser, Marvin Belser, and Anthony Belser, of Montgomery, Ala

bama; Etherline House, individually and on behalf of her minor

children, Elmore House, Roger House, and Zachary House, of

Montgomery, Alabama; Lou Ella Jackson, individually and on be

half of her minor children Regina Jackson, Angela Jackson, Phyllis

( 1)

2

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the district court (Interv. Pet. App. la-

15a) 2 is reported at 480 F. Supp. 790. The opinion of

Jackson, Gregory Jackson, Michele Jackson, Dora Lee Jackson,

Lewis Jackson, Jr., and Sandra Jackson, of Montgomery, Alabama;

Elsie R. Walker, individually and on behalf of her minor children,

Sonja S. Walker and Cornell E. Walker, Jr., of Farmville, Vir

ginia; Anna G. Miller, individually and on behalf of her minor

child, Joseph W. Miller, Jr., of Farmville, Virginia; Clydia Koen,

individually and on behalf of her minor children, Robbie Koen and

Cara Koen, of Cairo, Illinois; Annie L. Johnson, individually and

on behalf of her minor child, Howard Johnson, Jr., of Cairo, Illi

nois ; Mable Hollis, individually and on behalf of her minor chil

dren, Bernadian Hollis and Frank Hollis, of Cairo, Illinois; Hyland

L. Davis, individually and on behalf of his minor children, Damon

A. Davis and Troy A. Davis, of Beaufort, South Carolina; Law

rence Washington, individually and on behalf of his minor chil

dren, Youland J. Washington and Jerry J. Washington, of Sea-

brook, South Carolina; Rena M. Robinson, individually and on

behalf of her minor children, Angela Christine Robinson and Carol

Denise Robinson, of Bowman, South Carolina; Robert C. Zimmer

man, individually and on behalf of his minor children, Robert Zim

merman, Jr., Paul Zimmerman, Cynthia Zimmerman and Andrea

Zimmerman, of Bowman, South Carolina; Rev. John Wilbur Wright,

individually and on behalf of his minor children, Dedra Olether

Wright and JohnCalvin McCumell Wright, of Holly Hill, South

Carolina; Lavinia Washington, individually and on behalf of her

minor children, Stephen Washington, Gregory Washington, Eliot

Washington, and Kevin Washington, of Holly Hill, South Carolina;

Robert Jackson, individually and on behalf of his minor child,

Robert Jackson, Jr., of Natchitoches, Louisiana; Moses Williams,

individually and on behalf of his minor children, Rhonda Rense

Williams, Matra Lucille Williams, and Lula Marie Williams, of

Tallulah, Louisiana; Fred Bracy and Betty Bracy, on behalf of

themselves and on behalf of their minor children, Willie Bracy and

Robert Bracy, of Monroe, Louisiana; Alma Lee Griffin and Darnell

Griffin, on behalf of themselves and on behalf of their minor chil

dren, Gregory Griffin, Carol Dyne Griffin, Verline Ann Griffin, Car

men Griffin, and Terry Griffin, of Monroe, Louisiana; and Herbert

H. Jackson, individually and on behalf of his minor children, Carla

Cumberlander, Vincent Cumberlander, Francine Cumberland©!', and

Herbert H. Jackson, Jr., of Roxbury, Massachusetts.

2 “Interv. Pet.” refers to the petition for a writ of certiorari

(No. 81-757) filed by intervenor W. Wayne Allen, Chairman of the

3

the court of appeals (Interv. Pet. App. lb-58b) is re

ported at 656 F.2d at 820.

JURISDICTION

The court of appeals entered its judgment on June 18,

1981 (J.A. 9, 67) and denied rehearing on August 26,

1981 (J.A. 9; Interv. Pet. App. lc, Id). The Secretary

and the Commissioner filed a petition for a writ of certi

orari on November 23, 1981 (No. 81-970). This Court

granted the petition and consolidated the case with Allen

v. Wright, et al. (No. 81-757) on June 20, 1983 (J.A. 85,

86). The jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28 U.S.C.

1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS, STATUTES

AND REGULATIONS INVOLVED

The Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitution, Section 501(a) and (c)(3) of the

Internal Revenue Code of 1954 (26 U.S.C.), Rev. Stat.

1977 (1878 ed.) (42 U.S.C. 1981), and Sections 103 and

615 of the Treasury, Postal Service, and General Govern

ment Appropriations Act of 1980, Pub. L. No. 96-74, 93

Stat. 562, 577, are set forth at Interv. Pet. 2-4. The rel

evant provisions of Article III of the Constitution and

Section 170(a) and (c) (2) of the Internal Revenue Code

of 1954 (26 U.S.C.) are set forth in Appendix A to the

petition for certiorari in No. 81-970.

Rev. Proc. 75-50, 1975-2 Cum. Bull. 587, the Proposed

Revenue Procedure, and the Modified Proposed Revenue

Procedure are set forth respectively at Interv. Pet. App.

le-12e, lf-13f, and lg-14g.

STATEMENT

A. Background

In 1970, the Internal Revenue Service adopted the posi

tion that a private school will not qualify as a tax-

exempt organization under Section 501(c) (3) of the In

ternal Revenue Code of 1954, or as an eligible recipient

Board of Trustees of the Briarcrest School System, Memphis,

Tennessee.

4

of charitable contributions deductible for income tax pur

poses under Section 170(c) (2) of the Code, unless it es

tablishes that its admissions and educational programs

are operated on a racially nondiscriminatory basis.3 This

position was recently upheld by this Court in Bob Jones

University v. United States, Nos. 81-3 and 81-1 (May

24, 1983). In Rev. Rul. 71-447, 1971-2 Cum. Bull. 230,

the Service defined operation under a racially nondis

criminatory policy to mean that “the school admits the

students of any race to all the rights, privileges, pro

grams, and activities generally accorded or made avail

able to students at that school and that the school does

not discriminate on the basis of race in administration of

its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship

and loan programs, and athletic and other school-

administered programs.” Under this policy, the Service

has revoked the tax exemptions of more than 100 private

schools that failed to adopt and publicize a racially non

discriminatory policy (Tax-Exempt Status of Private

Schools: Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Oversight of

the House Comm, on Ways and Means, 96th Cong., 1st

Sess. 252 (1979) (statement of Commissioner Jerome

K urtz)). See, e.g., Prince Edward School Foundation v.

Commissioner, 478 F. Supp. 107 (D.D.C. 1979), aff’d by

unpublished order, No. 79-1622 (D.C. Cir. June 30, 1980),

cert, denied, 450 U.S. 944 (1981).

In 1972 and in 1975, the Internal Revenue Service pub

lished guidelines and procedures for determining whether

a private school operates in good faith under a racially

3 Section 501(c)(3) of the Code lists organizations that are

exempt from federal income tax pursuant to Section 501 (a ). Among

these are organizations formed and operated exclusively for reli

gious, charitable, or educational purposes. If an organization is

described in Section 501(c) (3), contributions to it are deductible

as charitable contributions for purposes of the federal income tax

under Section 170(c) (2), and deductible for purposes of the fed

eral estate and gift taxes under, respectively, Section 2055 and

2522. The organization is also exempt from social security taxes

on employees by virtue of Sections 3121(b)(8)(B) (FICA) and

3306(c)(8) (FUTA).

5

nondiscriminatory policy. See Rev. Proc. 72-54, 1972-2

Cum. Bull. 834; Rev. Proc. 75-50, 1975-2 Cum. Bull. 587

(Interv. Pet. App. le-12e). Rev. Proc. 75-50, which is

currently in effect, provides that “ [a] school must show

affirmatively both that it has adopted a racially nondis

criminatory policy as to students that is made known to

the general public and that since the adoption of that

policy it has operated in a bona fide manner in accord

ance therewith” (Section 2.02). The Procedure is en

forced by means of annual certifications subject to pen

alty of perjury, reporting and recordkeeping require

ments, and public complaints (Interv. Pet. App. 7e-8e,

9e-lle). The Revenue Procedure enumerates require

ments that must be met by each school seeking to estab

lish its eligibility for tax exempt status. The district

court summarized these requirements as follows (Interv.

Pet. App. 8a-9a n.3) :

(1) The schools must formally state their nondis

criminatory policy in their organizational charter or

similar instrument (Rev. Proc. 75-50, Sec. 4.01);

(2) The schools must set forth that policy in all

brochures, advertisements, catalogues, fund solicita

tions and similar publications (Sec. 4.03) ;

(3) The schools must either effectively publish that

policy under specified, detailed guidelines in newspa

pers (Sec. 4.03-1 (a)), or broadcast media (Sec.

4.03-1 (b )) ; or, in the alternative, they must be able

to demonstrate that they in fact have a significant

minority enrollment or have meaningfully sought to

recruit such an enrollment (Sec. 4.03-2);

(4) The schools must have a nondiscriminatory pol

icy with respect to faculty, school programs, and tui

tion and scholarship practices (Secs. 4.04, 4.05) ;

(5) They must certify all of the above under pen

alty of perjury (Sec. 4.06) ;

(6) The schools must provide specified information

to [the Service] regarding the racial composition of

their faculty and staff, the nondiscriminatory char-

6

acter of their tuition and scholarship policies, and

the policies regarding race discrimination held by

their incorporators, founders, board, and donors

(Sec. 5.01-1 through 5.01-4, see also Secs. 4.07,

4.08); and

(7) The schools must keep records for three years

periods [sic] from the year of compilation, regarding

racial composition of faculty and students, nondis

crimination in scholarship and tuition, and as well

as retaining copies of all brochures, catalogues, and

the like (Sec. 7).4

On August 22, 1978 and February 9, 1979, the Internal

Revenue Service published proposed Revenue Procedures

(Interv. Pet. App. lf-13f, lg-14g) that would tighten the

requirements for tax exempt status. Under the August

22, 1978 proposal, any private school which had an insig

nificant number of minority students and which was

formed or substantially expanded during a period of

desegregation of the public schools in its community (a

“reviewable” school) would be presumed racially discrim

inatory unless the school could demonstrate that it op

erated in good faith on a nondiscriminatory basis, to be

evaluated according to five specified factors.® The pro-

4 Even schools that meet the test of Rev. Proc. 75-50 can be found

ineligible for tax exempt status under Rev. Rul. 71-447 ( Tax-

Exempt Status of Private Schools: Hearings Before the Subcomm.

on Oversight of the House Comm, on Ways and Means, 96th Cong.,

1st Sess. 253 (1979) (statement of Commissioner Jerome Kurtz)).

6 The five factors specified were:

1. Availability of and granting of scholarships or other

financial assistance on a significant basis to minority students.

2. Active and vigorous minority recruitment programs,

such as contacting prospective minority students and organiza

tions from which prospective minority students could be iden

tified.

3. An increasing percentage of minority student enroll

ment.

4. Employment of minority teachers or professional staff.

7

posal prompted a heavy volume of adverse written com

ments, as well as adverse testimony at public admin

istrative hearings. In response to the public reaction,

the Service published for public comment a revised ver

sion of the proposed procedure on February 9, 1979. The

revised proposal, like the earlier proposal, established ad

ditional criteria “reviewable” schools would have to sat

isfy in order to retain tax exempt status. The revised

proposal, however, would have provided “greater flexibil

ity for a school to show that it is operating on a racially

nondiscriminatory basis” (Interv. Pet. App. 2g) by per

mitting it to demonstrate that it had “undertaken ac

tions or programs reasonably designed to attract minor

ity students on a continuing basis” (id. at l lg ) .

In February and March 1979, the Oversight Subcom

mittee of the House Committee on Ways and Means con

ducted hearings on the IRS proposals, and received a

great deal of adverse testimony. Tax Exempt Status of

Private Schools: Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Over

sight of the House Comm, on Ways and Means, 96th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1979). In the wake of the hearings, the

House Committee on Appropriations recommended that

5. Other substantial evidence of good faith, including evi

dence of a combination of lesser activities, such as—

(a) Continued and meaningful advertising programs be

yond the requirements of Revenue Procedure 75-50, or con

tacts with minority leaders inviting applications from minor

ity students.

(b) Significant efforts to recruit minority teachers.

(c) Participation with integrated schools in sports, music,

and other events or activities.

(d) Making school facilities available to outside, inte

grated civic or charitable groups.

(e) Special minority-oriented curriculum or orientation

programs.

(f ) Minority participation in the founding of the school or

current minority board members.

(Interv. Pet. App. 9f-10f).

8

adoption of the Service’s proposals be deferred until after

the regular tax writing committees of Congress had de

termined that they represented the proper interpretation

of the tax laws (H, R. Rep. No. 96-248, 96th Cong., 1st

Sess. 14-15 (1979)). Congress then proceeded to block

implementation of the proposed guidelines through enact

ment of two related provisions in the Treasury, Postal

Service, and General Government Appropriations Act of

1980, Pub. L. No. 96-74, 93 Stat. 559. In Section 615

(93 Stat. 577), known as the Dornan Amendment, Con

gress stipulated that none of the funds made available

by that Act be used to carry out the proposed Reve

nue Procedures of 1978 and 1979. In Section 103 (93

Stat. 562), known as the Ashbrook Amendment, Congress

provided that none of the funds made available by the

Act be used “to formulate or carry out any rule, policy,

procedure, guideline, regulation, standard, or measure

which would cause the loss of tax-exempt status to pri

vate, religious or church-operated schools under section

501(c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1954 unless

in effect prior to August 22, 1978.” The district court

observed that “ [t]he effect of [this congressional] action

is to retain in effect, at least until September, 1980, the

presently effective Rev. Proc. 75-50 * * *” (Interv. Pet.

App. 14a).

The Ashbrook-Dornan Amendments expired on October

1, 1980, but were reinstated for the period December 16,

1980 through September 30, 1981.'8 For fiscal year 1982,

after the court of appeals’ decision in this case, the House

of Representatives adopted a spending restriction that

specifically denied funding for carrying out even court

orders entered after August 22, 1978.7 See 127 Cong.

6 H.R.J. Res. 644, 96th Cong., 2d Sess. (1980), Pub. L. No. 96-536,

Section 101(a)(1) and (4), 94 Stat. 3166, as amended by Supple

mental Appropriations and Rescission Act of 1981, Pub. L. No. 97-

12, Section 401, 95 Stat. 95.

7 The House voted to modify the 1980 Ashbrook Amendment by

inserting the phrase “court order” in an amendment to the Treas-

9

Rec. H5392-H5398 (daily ed. July 30, 1981). The Senate

Committee on Appropriations subsequently reported out a

spending restriction in identical form. Under a joint

resolution making continuing appropriations for the 1982

fiscal year, this provision became effective as of Octo

ber 1, 1981.8

These statutory restrictions have now expired, and the

Internal Revenue Service is again free to consider appro

priate modifications in its enforcement of the prohibition

on tax exempt status for discriminatory private schools.

Changes, if any, will be instituted through regular ad

ministrative procedures and will be subject to congres

sional oversight. No such changes have yet been proposed

or adopted.

B. The Proceedings in this Case

1. Respondents are the parents of black students who

attend public schools in seven states. They seek to repre

sent a nationwide class of “several million” parents

whose children attend public schools in school districts

undergoing desegregation (J.A. 18-23, 43). In 1976, they

brought this suit in the United States District Court for

the District of Columbia against the Secretary of the

Treasury and the Commissioner of Internal Revenue, al

leging with reference to Rev. Proc. 75-50 that “regula

tions” issued by the federal defendants are legally insuf-

ury, Postal Service, and General Government Appropriations Bill,

1982 (H.R. 4121, 97th Cong., 1st Sees. (1981)). The bill thus

provided in § 616:

None of the funds made, available pursuant to the provisions

of this Act shall be used to formulate or carry out any rule,

policy, procedure, guideline, regulation, standard, court order,

or measure' which would cause the loss of tax-exempt status to

private, religious, or church-operated schools under Section

501(e) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1954 unless in ef

fect prior to August 22,1978 (emphasis added).

8H.R.J. Res. 325, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981), Pub. L. No. 97-51,

Section 101(a) (3), 95 Stat. 958; see 127 Cong. Rec. H6698-H6699,

H6702 (daily ed. Sept. 30, 1981).

10

ficient in that they permit schools offering “racially segre

gated educational opportunities” to receive tax exempt

status (J.A. 17-18, 25). Although the complaint asserted

that “there are more than 3,500 racially segregated pri

vate academies operating in the country having a total

enrollment of more than 750,000 children” (J.A. 24), it

cited by name only 19 “representative” private schools.8

Each of these schools is alleged to have “an announced

policy of nondiscrimination, and [to have] satisfied de

fendants in this regard,” but, according to the complaint,

is “racially segregated” (J.A. 26-38).“ According to the

complaint, the federal officials “have fostered and encour

aged the development, operation and expansion of many

of these racially segregated private schools by recognizing

them as ‘charitable’ organizations described in Section

501(c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code” (id. at 24).

9 The following' private schools were identified by name in the

complaint: Harding Academy, Briarcrest Baptist School System

and the Southern Baptist Schools of Whitehaven, Inc., Memphis,

Tennessee; Natchitoches Academy, Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana;

Delta Christian Academy and Tallulah Academy, Madison Parish,

Louisiana; River Oaks School, Monroe, Louisiana; Holly Hill Acad

emy and Bowman Academy, Orangeburg, South Carolina; Sea Pines

Academy, Beaufort County, South Carolina; Prince Edward Acad

emy, Prince Edward County, Virginia; Montgomery Academy and

St. James Parish School, Montgomery, Alabama; Camelot Parochial

School, Cairo, Illinois; Hyde Park Academy, South Boston Heights

Academy and Parkway Academy, Boston, Massachusetts (J.A. 26-

38). The complaint referred, in addition, to “thousands of other

racially segregated independent private schools which operate in or

serve desegregating public school districts and which have received,

applied for, or will apply for tax exemptions” (id. a t 32-33).

10 Respondents apparently used the term “racially segregated”

with reference to private schools in their complaint to signify only

that there were few or no black students in attendance at a school,

and not to signify that the absence of more black students was the

result of racially exclusionary practices. At a hearing in the dis

trict court, counsel for respondents conceded that he did not know

whether any of the black children who are parties to this action

would be denied admission to any private school on the basis of

race (J.A. 62-63).

11

To establish their standing to sue, respondents included

an allegation of injury in their complaint. It states, in

full (J.A. 38-39) :

As a consequence of the grant of federal tax bene

fits to racially segregated private schools, or the or

ganizations that operate them, which are located in

or serve desegregating public school districts, plain

tiffs and their class now are suffering and will con

tinue to suffer serious, substantial and irreparable

injury for which they have no adequate remedy at

law. Specifically, the grant of federal tax exemp

tions to such schools and organizations in such cir

cumstances injures plaintiffs in that it:

(a) constitutes tangible federal financial aid

and other support for racially segregated edu

cational institutions, and

(b) fosters and encourages the organization,

operation and expansion of institutions provid

ing racially segregated educational opportu

nities for white children avoiding attendance in

desegregating public school districts and thereby

interferes with the efforts of federal courts,

HEW and local school authorities to desegregate

public school districts which have been operating

racially dual school systems.

Respondents did not allege that they or their children had

applied to, been discouraged from applying to, or been

denied admission to any private school or schools.11 Nor

did they allege that denial of tax exempt status would

cause any private school or schools to close down, decrease

in enrollment,, or change their practices.12 They conceded

that their children now attend desegregated schools (J.A.

11 As the court of appeals noted, “Plaintiffs * * * maintain they

have no interest whatever in enrolling their children in a private

school” (Interv. Pet. App. 13b).

12 As the court of appeals noted, “Plaintiffs * * * claim indiffer

ence as to the course private schools would take” (Interv. Pet. App.

18b).

12

62). They did not allege that their own tax liability is

affected by the conduct or policies they challenge.

Respondents requested a declaratory judgment that

“the acts, policies and practices of defendants in granting

federal tax exemptions and benefits to racially segregated

private schools * * * violate Section 501 of the Internal

Revenue Code of 1954, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, and

the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitu

tion of the United States” (J.A. 40). In addition, they

sought a permanent injunction requiring the federal offi

cials to revoke, or to deny, tax exemptions for all private

schools (or for the organizations that operate the

schools), “which have insubstantial or nonexistent minor

ity enrollments, which are located in or serve desegregat

ing public school districts, and which either (J.A. 40) —

(1) were established or expanded at or about the

time the public school districts in which they are

located or which they serve were desegregating;

(2) have been determined in adversary judicial or

administrative proceedings to be racially segre

gated ; or

(3) cannot demonstrate that they do not provide

racially segregated educational opportunities for

white children avoiding attendance in desegre

gating public schools.

Respondents further requested the court to grant in

junctive relief in the nature of mandamus requiring the

federal officials to revise Rev. Proc. 75-50 to provide that

recognition of exempt status for all such schools and

organizations would be revoked or denied (J.A. 40-41).

The Secretary and the Commissioner filed a motion to

dismiss the complaint on the grounds that respondents

lacked standing to sue; that they failed to state a claim;

that the subject matter of their suit was nonreviewable;

and that the action was barred by the Anti-Injunction

Act (26 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 7421(a)), the tax limitation

in the Declaratory Judgment Act (28 U.S.C. (Supp. V)

13

2201), and the doctrine of sovereign immunity (J.A. 45-

46). The district court granted leave to intervene and to

file a motion to dismiss to W. Wayne Allen, Chairman of

the Board of the Briarcrest School, Memphis, Tennessee,

one of the private schools named in respondents’ com

plaint (id. at 26-27, 47-50, 54-57).

2. The district court dismissed the suit on three

grounds (J.A. 64, 65; Interv. Pet. App. 3a).18 First, the

court ruled that respondents had no standing to assert

their claims because (a) they failed to assert a distinct,

palpable, and concrete injury, (b) they had not shown

that any injury they alleged was fairly traceable to the

actions of the federal officials, (c) it was speculative

whether the relief requested would remedy the injury,

and (d) there was not a sufficient degree of concrete ad

verseness between respondents and the federal officials

(Interv. Pet. App. 4a-lla).

In so ruling, the court relied on Simon v. Eastern Ky.

Welfare Rights Organization, 426 U.S. 26 (1976). The

court noted that there was no allegation that any of the

private schools cited in the complaint actually were dis

criminating in violation of the Constitution or of federal

law, or that any of respondents or their children had suf

fered any discriminatory treatment or exclusion (Interv.

Pet. App. 4a-6a). The court considered it to be specula

tive whether enforcement of respondents’ proposed guide

lines would cause any school permanently to lose a tax

exemption that it would have retained under existing In

ternal Revenue Service procedures (id. at 8a-10a). Fur

thermore, even if implementation of respondents’ pro

posed enforcement procedures might serve to deprive

13 In a related action confined solely to private schools in the

State of Mississippi, Green V. Regan (Civ. Action No. 1355-69

(D.D.C. May 17, 1977)), which was consolidated with the instant

case in the district court, the district court denied the government’s

motion to dismiss (J.A. 53), finding that the Green plaintiffs “have

a right to proceed to determine whether or not * * * there has been

good-faith compliance with the Order of this Court” (J.A. 52). See

also Interv. Pet. App. 3a n.l.

14

some schools of exemptions that they could not later re

cover, the court regarded it as equally speculative

whether a loss of exemptions would produce a change in

the desegregation of any given school district. Instead, it

appeared to the court probable that many schools had

only a limited dependence on tax exemptions and, if

forced to choose, would forgo tax-exempt status rather

than abandon their practices. The court accordingly con

cluded that respondents had failed to show a sufficient

causal nexus between the injury alleged and the chal

lenged procedures {id. at 6a-10a).

Second, the district court ruled that respondents’ action

was “barred by the doctrine of nonreviewability” because

it “would require this Court to undertake detailed or con

tinuing review of a generalized IRS enforcement pro

gram, or to review complex issues of tax enforcement

policy and of agency resource allocation” (Interv. Pet.

App. 11a). As the court saw the matter, such review

“would be tantamount to this Court becoming a ‘shadow

commissioner of Internal Revenue’ to run the administra

tion of tax assessments to private schools in the United

States” {id. at 12a).

Finally, the court concluded that the enactment in 1979

of the Ashbrook and Dornan Amendments to the Treas

ury Appropriations Act expressed “the Congressional in

tent that Section 501(c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code

[was] not susceptible of the construction which [re

spondents] would place upon it in this case” {id. at 14a-

15a). While the court acknowledged that the Ashbrook

and Dornan Amendments (as applied in fiscal years 1980

and 1981) apparently allowed a federal court to fashion

a remedy, it concluded that “in such an area ripe [sic]

with legislative history and government regulation, it is

not the business of a federal court to explicitly thwart

the will of Congress or to otherwise fail to carry it out”

{id. at 15a).14

14 The district court found it unnecessary to consider the other

grounds urged in support of the motion to dismiss, viz., absence

15

3. A divided panel of the court of appeals reversed the

judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings

(J.A. 67). The court ruled that respondents had stand

ing to maintain their action (Interv. Pet. App. 12b-25b).

In so ruling, the court recognized that Simon v. Eastern

Ky. Welfare Rights Organization, supra, “suggests that

litigation concerning tax liability is a matter between

taxpayer and IRS, with the door barely ajar for third

party challenges” (Interv. Pet. App. 16b). It recognized

also that certain of its own previous decisions had dis

missed for lack of standing suits brought by persons who

sought to litigate the tax liability of others (id. at 17b,

n.24).115

But the court of appeals concluded that other decisions

of this Court point in an “opposite direction!]” (Interv.

Pet. App. at 16b). See Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997 (1971),

aff’g Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. 1971);

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973) ; Gilmore v.

City of Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556 (1974). In the court’s

view, those cases “recognized the right of black citizens to

insist that their government ‘steer clear’ of aiding schools

in their communities that practice race discrimination”

(Interv. Pet. App. 24b-25b). The court ruled that “ [i]n

view of the centrality of that right in our contemporary

(post-Civil War) constitutional order, we are unable to

conclude that Eastern Kentucky speaks to the issue be

fore us” (ibid.).

In addition, the court found no impediment to the

action in the doctrine of non-reviewability (Interv. Pet.

of illegal state action, ban of the Anti-Injunction and Declaratory

Judgment Acts, sovereign immunity, and failure to join indispensa

ble parties. The court of appeals remanded on those issues (Interv.

Pet. App. 3b n.2), and we will not address them in this brief.

15 See American Society of Travel Agents, Inc. v. Blumenthal,

566 F.2d 145 (D.C. Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 435 U.S. 947 (1978) ;

Tax Analysts & Advocates v. Blumenthal, 566 F.2d 130 (D.C. Cir.

1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1086 (1978). See also American

Jewish Congress v. Vance, 575 F.2d 939 (D.C. Cir. 1978).

16

App. 32b-35b). The court concluded that respondents’

claims derive from constitutional concerns that courts, not

administrators, are better equipped to address (id. at

32b-33b n.53). In the court’s view, if respondents were

to prevail on the merits of their claims, relief would not

entail “large scale judicial intervention in the adminis

trative process” (id. at 35b). Nor did the court consider

the Ashbrook and Dornan amendments to be an obstacle

to fashioning a remedy (id. at 25b-32b). Those amend

ments, as the court construed them, were merely tem

porary checks on Internal Revenue Service initiatives and

did not purport to control judicial dispositions (id. at

29b-30b).16

In dissent, Judge Tamm would have held that respond

ents had no standing to sue (Interv. Pet. App. 38b-58b).

He found that they failed to allege a distinct and palpable

injury to themselves, or a sufficient nexus between the

Internal Revenue Service’s actions and whatever injury

they claimed to have suffered. In his view, the majority

of the court erroneously interpreted Green, Norwood, and

Gilmore “as requiring it to abandon long-established

standing principles, principles limiting the exercise of

judicial power to the redress of actual injury” (Interv.

Pet. App. 38b; emphasis in original). The majority’s

opinion, he concluded, was “the product of an impermis

sible shift in focus from the right of these plaintiffs to

make their challenge to the rights they wish to assert”

(id. at 57b).

On August 26, 1981, the court denied the government’s

motion for en banc consideration, three judges dissenting

(Interv. Pet. App. Id ).17

16 The court of appeals’ decision was rendered before the Ash

brook Amendment was amended expressly to encompass court or

ders. See note 7, supra.

17 Thereafter, on motion of respondents (J.A. 68-78), the court

of appeals issued orders on February 18, 1982, and on March 24,

1982 (Tamm, J., dissenting), enjoining the Secretary and the Com

missioner from granting Section 501(c)(3) status to any school

that unlawfully discriminates on the basis of race- (J.A. 81-84).

17

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. Respondents seek judicial revision of Internal Reve

nue Service guidelines and procedures that have been the

subject of intense public comment and congressional over

sight over the last decade. Alleging no injury to them

selves at the hands of the private schools whose tax ex

emptions they challenge, and no injury at the hands of

the government defendants other than their disapproval

of government practices, respondents stand as mere dis

appointed observers of the governmental process. The

judgment below holding that they have standing to main

tain this action is in direct conflict with this Court's deci

sion in Simon v. Eastern Ky. Welfare Rights Organiza

tion, 426 U.S. 26 (1976), and with other decisions estab

lishing the limitations on the jurisdiction of an Article

III court.

II. Respondents alleged two injuries stemming from

the government’s method of enforcing the restrictions on

tax exemptions for discriminatory private schools.

Neither allegation satisfies this Court’s requirements for

establishing standing to sue.

A. The first allegation of injury—that the govern

ment’s action “constitutes tangible federal financial aid

and other support for racially segregated educational in

stitutions” (J.A. 38)—amounts to no more than “asser

tion of a right to a particular kind of government con

duct,” which this Court has held to be an insufficient

basis for standing under Article III (Valley Forge Chris

tian College v. Americans United for Separation of

Clmrch and State, Inc., 454 U.S. 464, 471-476, 483

(1982)). Respondents simply have not alleged any “dis

tinct or palpable” injury to themselves (see Gladstone,

Realtors v. Village of Bellwood, 441 U.S. 91, 100 (1979)).

B. The second allegation of injury—that the govern

ment’s “encourage [ment]” of segregated private schools

“interferes with the efforts of federal courts, HEW and

local school authorities to desegregate public school dis-

18

tricts” (J.A. 39)—shares the deficiency of the first, and

is also too speculative to support standing, since a change

in Internal Revenue Service guidelines and procedures

might or might not result in a decrease in availability of

segregated private schools to white children fleeing de

segregating public schools. Indeed, respondents have not

even alleged that the relief they seek would produce such

a result. Their position, therefore, has all the shortcom

ings, and more, of the plaintiffs’ position in Eastern Ken

tucky, supra.

III. An examination of the means by which Congress

intended the federal tax system to operate suggests that

no person who is not himself seeking a tax benefit has

standing to challenge the Internal Revenue Service’s

treatment of the tax liabilities of others. See Linda R. S.

v. Richard D., 410 U.S. 614 (1973); Louisiana v McAdoo,

234 U.S. 627 (1914) ; Eastern Kentucky, supra, 426 U.S.

at 46 (Justice Stewart, concurring). Opening the courts to

generalized grievances concerning enforcement of the tax

laws would lead to extensive interference in the adminis

trative process, intended to be left to the supervision of

the President and Congress.

IV. The court of appeals erred in concluding that this

Court’s decisions in Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997 (1971),

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973), and Gilmore

v. City of Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556 (1974), are at odds

with Eastern Kentucky and the other rulings of this

Court on the doctrine of standing. Although Gilmore ad

dresses standing in but a footnote and Norwood not at

all, it is clear that the plaintiffs in those cases had stand

ing on the traditional basis of protecting rights they were

entitled to under earlier judicial decrees (see Gilmore,

supra, 417 U.S. at 570 n.10). Coit v. Green, a summary

affirmance, did not constitute a ruling by this Court on

the issue of standing, and was later held by this Court to

“lack[] the precedential weight of a * * * truly adver

sary controversy” (Bob Jones University v. Simon, 416

U.S. 725, 740 n .ll (1974)).

19

ARGUMENT

L RESPONDENTS LACK STANDING TO CHAL

LENGE TREASURY GUIDELINES AND PROCE

DURES THAT HAVE BEEN SUBJECT TO EX

ECUTIVE AND LEGISLATIVE REVIEW AND RE

SULT IN NO CONCRETE INJURY TO THEM

Respondents, who are parents of black public school

children suing on behalf of themselves and their children

and on behalf of all other parents of black students at

tending public schools in districts undergoing desegrega

tion, have brought this suit to require the Secretary of

the Treasury and the Commissioner of Internal Revenue

to revise Internal Revenue Service guidelines and proce

dures implementing the prohibition on tax exempt treat

ment for educational institutions that engage in racially

discriminatory practices, under Sections 170(c) (2) and

501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1954 (26

U.S.C.). Respondents’ complaint challenges not the pro

priety of the Internal Revenue Service’s substantive policy

against fax exempt status for discriminatory schools,

which was upheld by this Court last Term in Bob

Jones University v. United States, Nos. 81-3 and 81-1

(May 24, 1983), but the effectiveness of the measures by

which that policy is enforced. As the court of appeals ex

pressed it, “plaintiffs complain * * * that some schools

'are slipping through the Commissioner’s net of enforce

ment’ ” (Interv. Pet. App. 22b n.27).

Respondents allege18 that current Internal Revenue

Service guidelines and procedures regarding applications

for tax exempt status by private schools are “legally in

sufficient” because “many private schools with insubstan

tial or nonexistent minority enrollments which were or

ganized or expanded at or about the time public school

18 For purposes of evaluating the correctness of the district

court’s dismissal of respondents’ action, the allegations in their

complaint will be accepted as true. See Gladstone, Realtors v. Vil

lage of Bellwood, 441 U.S. 91,115 (1979).

20

districts in which they are located or which they serve

were desegregating, have retained their federal tax ex

emptions merely by adopting and certifying—but not

implementing—the required policy of nondiscrimination”

(J.A. 25).19 Respondents do not challenge the tax exempt

status of any particular schools, although their complaint

lists 19 “representative” tax exempt private schools that

they allege to be “racially segregated” (J.A. 26-38).

Respondents admittedly have not alleged that they have

been excluded or otherwise discriminated against by these

or any other tax exempt private schools; nor do they

allege that revocation of the schools’ tax exempt status

would cause the schools to close down or to alter their

practices. As the court of appeals noted, respondents

“claim indifference as to the course private schools would

take” (Interv. Pet. App. 18b).

Respondents have asked the courts to require the Serv

ice to adopt new guidelines and procedures which would

deny or revoke any tax exemptions of schools with “insub

stantial or nonexistent minority enrollments” in districts

where public schools are undergoing desegregation, under

any of three conditions: (1) if they “were established or

expanded at or about the time the public school districts in

which they are located or which they serve were desegre

gating” ; (2) if they “have been determined in adversary

judicial or administrative proceedings to be racially seg

regated” ; or (3) if they “cannot demonstrate that they do

not provide racially segregated educational opportunities

for white children avoiding attendance in desegregating

public school systems” (J.A. 40).

19 This is not, properly speaking, a challenge to Rev. Proc. 75-50,

which expressly requires that, to be tax exempt, “ [a] school must

show affirmatively, * * * that since the adoption, of [a racially non-

discriminatory policy] it has operated as a bona fide manner in

accordance therewith” (Interv. Pet. App. le). Respondents ap

parently do not believe Rev. Proc. 75-50 is being enforced, though

they allege no specific instance in which a tax exempt school has

failed to implement its nondiscriminatory policy.

21

Respondents’ proposed policy is similar to proposals

published for public comment by the Internal Revenue

Service on August 22, 1978 (Interv. Pet. App. lf-13f) and

February 9, 1979 (id. at lg-14g).20 These proposals were

greeted with a barrage of more than 100,000 adverse writ

ten comments (id. at 11a). Congress conducted hearings

on the proposals, at which it heard additional criticism.

Following the hearings, the House Appropriations Com

mittee formally recommended that the Service defer adop

tion of the proposals until after the regular tax writing

committees could determine whether they properly inter

preted the tax laws (H.R. Rep. No. 96-248, 96th Cong.,

20 The Internal Revenue Service proposals and respondents’ pro

posals all are based on a presumption that private schools with few

or no minority students formed or expanded in times of public

school desegregation in their communities are- in violation of the

public policy underlying Sections 170(c) (2) and 501(c) (3). On the

basis of this common dement—characterized by the district court

as a “preisumed-guilty-until-proven-mnocent approach” (Interv. Pet.

App. 14a, quoting Second Supp. Mem. of Inte-rveno-r in Support of

Motion to Dismiss a t 4)—the district court concluded that con

gressional repudiation of the Internal Revenue Service proposals

“is the strongest possible expression of the Congressional intent

that Section 501(c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code- is not suscep

tible- of the construction which plaintiffs would place upon it in this

case” (Interv. Pet. App. 14a.-15a).

The principal difference between respondents’ somewhat vague

proposal and the- published proposals is in the- nature of the showing

that a school must make once the presumption of ineligibility has

attached. The Internal Revenue Service proposals focus on affirma

tive outreach efforts to attract minority students (see Interv. Pet.

App. 9f-10f (August 22, 1978 proposal); id. at l lg (February 9,

1979 proposal)), while respondents’ proposal focuses on whether

the school has been established or expanded during desegregation

or can be said to- provide- “racially segregated educational oppor

tunities” for white- children avoiding desegregation in public schools

(J.A. 40). I t is not clear that schools with open admissions pol

icies, e-ven with affirmative outreach efforts, would be- able to make

respondents’ requested showing; indeed, the schools’ tax exempt

status would depend on factors essentially outside their control.

By way of contrast, Rev. Proc. 75-50 focuses on whether a school

has adopted, announced, and implemented a “racially nondiscrimi-

nato-ry policy” (Interv. Pet. App. le-).

22

1st Sess. 14-15 (1979)). By vote of both houses, Congress

then barred implementation of the proposed guidelines

through amendments to the Treasury’s appropriations.21

These statutory restrictions have now expired, but until

further proceedings take place, again subject to congres

sional oversight, Rev. Proc. 75-50 remains in effect.

Respondents thus are in the posture of disappointed ob

servers of the governmental process. Proposals substan

tially similar to theirs have been formally proposed but,

as a result of the mixed considerations that govern the

fate of agency proposals subject to public comment and

congressional oversight, have not been adopted. The ques

tion naturally arises whether these individuals’ preference

for alternative enforcement procedures under Section

501 (c) (3) presents a justiciable controversy.

Under the holdings of this Court, a plaintiff must “ ‘al

lege [] such a personal stake in the outcome of the con

troversy’ as to warrant his invocation of federal-court ju

risdiction and to justify exercise of the court’s remedial

powers on his behalf” (Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490,

498-499 (1975) (emphasis in original), quoting Baker v.

Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 204 (1962)). The doctrine of stand

ing has both constitutional and prudential aspects, recently

summarized by this Court in Valley Forge Christian Col

lege v. Americans United For Separation of Church And

State, Inc., 454 U.S. 464, 471-476 (1982). As an “ir

reducible minimum,” Article III requires two showings:

(1) actual injury that (2) is traceable to the alleged il

legal conduct of the defendant and is likely to be redressed

by a favorable decision. These requirements ensure that

the court can resolve the legal issues presented “not in the

rarified atmosphere of a debating society, but in a con

crete factual context conducive to a realistic appreciation

of the consequences of judicial action” (id. at 472). They

also reflect a “ [p] roper regard for the complex nature of

our constitutional structure [, which] requires neither

21 These developments in Congress are described in more detail

(pages 7-9, supra).

23

that the Judicial Branch shrink from a confrontation with

the other two coequal branches of the Federal Govern

ment nor that it hospitably accept for adjudication claims

of constitutional violation by other branches of govern

ment where the claimant has not suffered cognizable in

jury” (id. at 474).

In addition to these constitutional requirements, this

Court has also recognized prudential limitations on the

ability of litigants to assert their claims in court. These

limitations were summarized in Warth v. Seldin, supra,

422 U.S. at 499: “Essentially, the standing question in

such cases is whether the constitutional or statutory pro

vision on which the ease rests properly can be understood

as granting persons in the plaintiff’s position a right to

judicial relief.” Particularly pertinent to this case is the

admonition against permitting litigants to raise “ab

stract questions of wide public significance,” (id. at 500)

which are “pervasively shared and most appropriately ad

dressed in the representative branches” (Valley Forge

College, supra, 454 U.S. at 474-475). Under both consti

tutional and prudential standards, respondents’ general

ized allegations of injury fall short.

In Simon v. Eastern Ky. Welfare Rights Organization,

426 U.S. 26 (1976), this Court faced a situation in many

ways identical to this. There, as here, members of the

public turned to the courts for reversal of Internal Reve

nue Service rulings governing the grant of Section 501

(c) (3) status to certain institutions, in that instance hos

pitals. This Court held that the plaintiffs lacked standing

to sue, even though they alleged an actual injury—a denial

of service—by the institutions whose tax exemptions they

were challenging. On its face, respondents’ complaint ap

pears to provide even less basis for standing than there

was in Eastern Kentucky. Respondents freely admit that

they do not desire admission to the educational institutions

whose tax exempt status they question (Br. in Opp. to

Cert, at 8). It should follow, a fortiori, that they lack

standing to bring this lawsuit. So the district court held.

24

Nonetheless, the court of appeals found that “Eastern

Kentucky is not the line appropriately followed in the

matter before us” (Interv. Pet. App. 18b), and reversed

the district court’s dismissal of respondents’ complaint.

It is therefore appropriate to consider in detail the al

legations of injury in respondents’ complaint, and set

them against the principles this Court has established

for determining whether litigants have standing to sue.

II. RESPONDENTS’ ALLEGATIONS OF INJURY ES

TABLISH NO DIRECT AND CONCRETE INJURY

CAUSED BY THE GOVERNMENT'S ACTIONS

AND REDRESSIBLE BY THE COURTS

A. Respondents’ Allegation That The Government Pro

vides Tangible Aid To Racially Segregated Institu

tions Establishes No “Injury In Fact,” But Only A

Generalized Grievance With Government Conduct

Respondents’ first allegation of injury is that the grant

of federal tax exempt status to racially segregated pri

vate schools in districts undergoing desegregation in

jures them in that it “constitutes tangible federal finan

cial aid and other support for racially segregated educa

tional institutions” (J.A. 38). On its face, this allegation

fails to draw any connection between the allegedly wrong

ful action and respondents’ own interests. In the course

of the hearing below on the motions to dismiss, the dis

trict court sought clarification from counsel as to the na

ture of the injuries asserted by respondents. Counsel for

respondents answered: “Their injury, Your Honor, is an

infringement of their Constitutional right to be free of

governmental support of private school discrimination

*” (J-A. 62). As expressed by respondents’ brief in

opposition to certiorari, “ [PJlaintiffs here have standing

to seek an end to government aid to private discrimina

tion because such government aid in and of itself injures

them” (Br. in Opp. at 9).122

22 Even these explanations may overstate respondents’ actual

allegations, which concern “schools which have insubstantial or

25

An allegation that third parties, who themselves have

not injured respondents, are improperly receiving tax

benefits does not identify a “distinct and palpable injury”

to respondents sufficient to justify judicial relief (Glad

stone, Realtors v. Village of Bellwood, 441 U.S. 91, 100

(1979)). This Court has never equated mere dissatisfac

tion over government conduct with the “injury in fact”

necessary to sustain Article III jurisdiction. This Court’s

formulations to describe the requisite injury have been

consistent and unambiguous: the plaintiff must have been

“concretely affected” (Blum v. Yaretsky, No. 80-1952

(June 25, 1982), slip op. 7); the injury must be “distinct

and palpable” (Warth v. Seldin, supra, 422 U.S. at 501) ;

“abstract injury is not enough” (O’Shea v. Littleton, 414

U.S. 488, 494 (1974)) ; a plaintiff “must allege that he

has been or will in fact be perceptibly harmed” (United

States v. SCRAP, 412 U.S. 669, 688 (1973)). The injury

need not, of course, be economic (id. at 686; Sierra Club

v. Morton, 405 U.S. 727, 734 (1972)) ; aesthetic and en

vironmental interests, for example, may support standing

(SCRAP, supra, 412 U.S. at 686). On the other hand, as

stated in Valley Forge College (454 U.S. at 482-483),

“This Court repeatedly has rejected claims of standing

predicated on ‘the right, possessed by every citizen, to re

quire that the Government be administered according to law

* * *’ ” (quoting Baker V. Carr, supra, 369 U.S. at 208,

quoting Fairchild v. Hughes, 258 U.S. 126, 129 (1922)).

It is not enough that litigants may be correct on the

merits, or that they are intensely interested or experi

enced in the problem (Sierra Club v. Morton, supra, 405

U.S. at 727). The courts are not authorized to review

legislative or executive decisions “at the behest of organi-

nonexislcnt minority enrollments and which are located in or serve

desegregating public school districts” (J.A. 26). As the district

court observed, there is no allegation that the schools whose tax

exemptions respondents question “are actually discriminating in

violation of the Constitution or federal law” (Interv. Pet. App.

5a-6a). Nor would respondents’ requested relief be confined to

schools that discriminate (J.A. 40-41).

26

zations or individuals who seek to do no more than vindi

cate their own value preferences through the judicial

process” {id. at 740). See also Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S.

83, 106 (1968).

Respondents in this case feel aggrieved because they do

not believe the government is doing an adequate job of

enforcing the laws; but as this Court has made clear,

litigants have no legally cognizable right “to have the

Government act in accordance with their views of the

Constitution [or statutory requirements] * * *. * * *

[Assertion of a right to a particular kind of government

conduct, which the government has violated by acting dif

ferently, cannot alone satisfy the requirements of Article

III without draining those requirements of meaning”

('Valley Forge College, supra, 454 U.S. at 483; see also

Laird v. Tatum, 408 U.S. 1, 13 (1972)).

The court of appeals stressed the “denigration” respond

ents suffer “as black parents and school children when

their government graces with tax-exempt status educa

tional institutions in their communities that treat mem

bers of their race as persons of lesser worth” (Interv. Pet.

App. 13b; see also id. at 34b). But this Court has re

jected the notion that “psychological” discomfiture at gov

ernment action, even if “phrased in constitutional terms,”

establishes a basis for standing (Valley Forge College,

supra, 454 U.S. a t 485-486). Were it otherwise, any

would-be litigant could defeat the Article III limitations

merely by alleging what cannot be disproved: that he

suffers “denigration,” “stigma,” or other forms of psycho

logical distress as a result of the challenged action.

With respect to their first allegation of injury, respond

ents have a claim no stronger than that of other litigants

who have been held to lack standing in cases before this

Court. In Schlesinger v. Reservists Committee to Stop the

War, 418 U.S. 208 (1974), plaintiffs sued to challenge the

eligibility of members of Congress under the Incompati

bility Clause, Art. I, § 6, C1.2, to serve as reservists in

the military. Characterizing their interest as one of hav-

27

ing their government “act in conformity” with the Con

stitution (418 U.S. at 217), this Court held that the plain

tiffs lacked standing to sue. See also Ex parte Levitt,

302 U.S. 633 (1937) (rejecting plaintiff’s standing to

challenge constitutionality of the appointment and con

firmation of a Justice of this Court under the Ineligibility

Clause, Art. I, § 6, C1.2) ; United States v. Richard

son, 418 U.S. 166 (1974) (rejecting taxpayer’s standing

to challenge the alleged failure of the Central Intelligence

Agency to comply with the Accounts Clause, Art. I , § 9,

Cl. 7). Also closely analogous to this case is Valley Forge

College, supra, in which plaintiffs challenged a transfer

of federal property to a religious institution as a violation

of the Establishment Clause.23 They claimed a “shared

individuated right to a government that 'shall make no

law respecting the establishment of religion’ ” (454 U.S.

at 482). The court rejected their claim of standing, how

ever, stating: “They fail to identify any personal in

jury suffered by the plaintiffs as a consequence of the al

leged constitutional error, other than the psychological

consequence presumably produced by observation of con

duct with which one disagrees. That is not an injury

sufficient to confer standing under Article III, even though

the disagreement is phrased in constitutional terms” {id.

at 485-486; emphasis in original).

Respondents’ allegation that the government is not ade

quately enforcing the Internal Revenue Code and the Con

stitution, and that in consequence private discrimination

is encouraged, is nothing more than a claim of their

“shared individuated right” to a government that ade

quately enforces the limits on tax exemptions to discrimi

natory schools. This is indistinguishable from allegations

of government failure to comply with the Incompatibility

23 Indeed, a conclusion that respondents lack standing in this

case would not raise the special problems associated with restric

tions on litigation under the Establishment Clause. See Valley

Forge College, supra, 454 U.S. at 500-505, 507-510 (Brennan, J.,

dissenting) ; id. a t 515 (Stevens, J., dissenting).

28

Clause, the Accounts Clause, the Ineligibility Clause, the

Establishment Clause, or any other constitutional or stat

utory provision by persons not directly injured.124 “ [A]

right to a particular kind of Government conduct, which

the Government has violated by acting differently, can

not alone satisfy the requirements of Article III without

draining those requirements of meaning” (Valley Forge

College, supra, 454 U.S. at 483).

Respondents’ standing cannot be justified, in the ab

sence of actual injury, on the basis of the “issues [they]

wish[] to have adjudicated” (Flast v. Cohen, supra, 392

U.S. at 99). The “right of black citizens to insist that

their government ‘steer clear’ of aiding schools in their

communities that practice race discrimination,” as iden

tified by the court of appeals (Interv. Pet. App. 24b-25b),

24 Respondents apparently believe that the rights they assert are

not “undifferentiated right[s] common to all members of the pub

lic” because' the Fourteenth Amendment is intended “to safeguard

an identifiable segment of the citizenry : blacks, the same class to

which respondents belong” (Br. in Opp. a t 10 n.10). There are

three flaws in this argument. First, respondents do not allege that

they have in fact been discriminated against by the private schools

in question; a t best they seek to protect the rights of fellow mem

bers of their race who might be (cf. Warth V. Seldin, supra, 422

U. S. a t 514). But injuries, like rights, pertain to individuals and

not to classes or races (cf. Connecticut V. Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 453-

456 (1982)). The fact that members of their race are specially

protected from injury by the Fourteenth Amendment does not ac

cord these respondents standing if they have not been injured

{Moose Lodge No. 107 V. Irvis, 407 U.S. 163, 166 (1972)). Second,

respondents are simply wrong if they assert that the benefits of

equal protection—even of desegregated schooling—belong not to

all citizens alike, but only to members of one race (see Washington

V. Seattle School District No. 1, No. 81-9 (June 30, 1982), slip op.

14; Milliken V. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 793 (1974) (Marshall, J.,

dissenting)). Finally, the claims petitioners assert derive from the

tax code, with its policy of granting exemptions only to' charitable

organizations whose activities benefit the community {Bob Jones

University V. United States, supra, slip op. 11-15). Respondents have

no greater standing than any other members of the public to seek

improved enforcement of this policy through the courts.

29

is indeed a fundamental concern of government {Bob

Jones University v. United States, supra, slip op. 17-20,

29), but “the centrality of that right in our contemporary

(post-Civil War) constitutional order” (Interv. Pet. App.

25b) does not create “injury in fact” where in fact there

is no injury.

The fundamental character of the constitutional or stat

utory provisions under which a plaintiff seeks to sue is

irrelevant to whether he has established standing (Valley

Forge College, supra, 454 U.S. at 484). Thus in Schles-