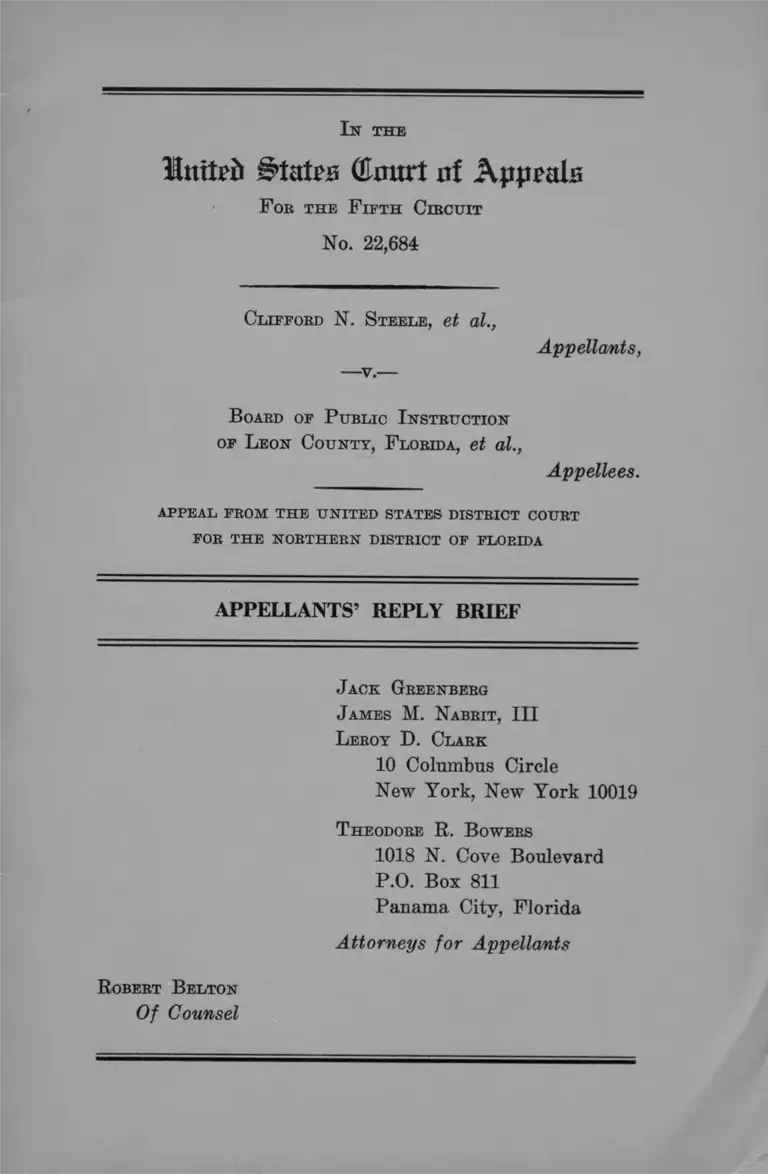

Steele v. Board of Public Instruction of Leon County Florida Appellants' Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Steele v. Board of Public Instruction of Leon County Florida Appellants' Reply Brief, 1965. 94a4401d-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a21dc357-a7bd-4296-9380-7e589610b501/steele-v-board-of-public-instruction-of-leon-county-florida-appellants-reply-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

•United States (Unurt nf Appeals

F ob the F ifth Ciecuit

No. 22,684

I n the

Clifford N. Steele, et al.,

—v.—

Appellants,

B oard of P ublic I nstruction

of Leon County, F lorida, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF FLOEIDA

APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Leroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

T heodore R. B owers

1018 N. Cove Boulevard

P.O. Box 811

Panama City, Florida

Attorneys for Appellants

Robert Belton

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

I. This Court Has Jurisdiction to Entertain This

Appeal Under the Authority of 28 U.S.C.A.

§1292(a)(l) ............................................................... 2

II. Becent Pronouncements From This and Other

Courts Lend Further Support to Appellants’

Claims That the School Board’s Plan is Inade

quate .......................................................................... 3

A. The School Board’s Present Plan ............ ..... 3

B. Current Minimum Standards ............................. 8

C. Faculty Desegregation Is a Necessary Com

ponent of Valid Desegregation Plan ............... 10

Summary ........... 10

I n the

Httitefc Stall's dmtrt of Appeals

F oe the F ifth Circuit

No. 22,684

Clifford N. Steele, et al.,

Appellants,

B oaed of Public I nstruction

of Leon County, Florida, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOE THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF

The School Board, in their brief, pp. 16-19 (hereinafter

cited as School Board Brief), raise the question of whether

this Court has jurisdiction to entertain this appeal. More

importantly, the School Board fails almost completely to

meet the issues presented by this appeal. In addition,

neither brief considers the desegregation plan in the case

at bar in light of the more recent judicial pronouncements.

Appellants shall endeavor to deal, as summarily as pos

sible, with the jurisdictional question raised by the School

Board in addition to reviewing the desegregation plan in

light of current standards.

2

I.

This Court Has Jurisdiction to Entertain This Appeal

Under the Authority of 28 U.S.C.A. §12 92 (a) ( 1 ) .

A consideration of the proceedings below leading to this

appeal clearly shows this Court has jurisdiction under 28

U.S.C.A. §1292(a)(l) which provides that courts of appeal

shall have jurisdiction over “Interlocutory orders of the

district courts of the United States . . . granting, continu

ing, modifying, refusing or dissolving injunctions, or re

fusing to dissolve or modify injunctions, except where a

direct review may be had in the Supreme Court. . . . ”

The order from which this appeal is taken was entered

by the court below on April 7, 1965, denying the Negro

plaintiffs’ motion for further relief (R. 64-67). The mo

tion for further relief, tiled about thirteen months after

the district court entered an order approving the desegre

gation plan in issue on this appeal, prayed for a modifica

tion of that plan. The district court, in approving the plan,

specifically retained jurisdiction of the matter (R. 39-42).

Since the district court retained jurisdiction in the order

approving the School Board’s plan, the order of April 7,

1965, denying appellants’ motion for further relief is an

interlocutory order within the meaning of 28 U.S.C.A.

§1292(a)(l) and is, therefore, reviewable by this Court.

Boson v. Rippy, 275 F. 2d 850 (5th Cir. 1960). See Board

of Public Instruction of Duval County v. Braxton, 326 F. 2d

616 (5th Cir. 1964).

The posture of the instant case before this Court is

patently distinguishable from Taylor v. Board of Educa

tion, 288 F. 2d 600 (2nd Cir. 1960) on which the School

Board relies (School Board Brief p. 19). In Taylor, the

appeal was from an order requiring only that the New

3

Rochelle School Board submit a plan—the plan had not

been submitted nor approved at the time the appeal was

sought. In the instant ease, the plan has been submitted

and approved pursuant to court order, and the district

court has denied appellants’ motion to modify the plan

(emphasis supplied). See Boson v. Rippy, supra at 853.

Even if the court below did not enter a “formal” order

on April 7, 1965, refusing the appellants injunctive relief

(similarly with the April 22, 1963 order), under the cir

cumstances,1 the Negro parents and pupils were entitled

to have a specific ruling from the trial court, and his

“refusal” to do so satisfies the requirements of 28 U.S.C.A.

§1292(a)(l). Compare United States v. Lynd, 301 F.2d

818, 822 (5th Cir. 1962).

II.

Recent Pronouncements From This and Other Courts

Lend Further Support to Appellants’ Claims That the

School Board’s Plan Is Inadequate.

A. The School Board’s Present Plan

The School Board’s brief tends to confuse rather than

justify the serious inadequacies of its desegregation plan.

The question is not whether the plan is being adminis

tered in good faith as approved by the district court (see

School Board Brief 4, 10). The critical issue is whether

the plan itself is adequate compliance by the School Board

in discharging its affirmative obligation to desegregate the

Leon County public school system. In addition to the in

adequacies already discussed in appellants’ main brief, pp.

1 See appellants’ main brief, pp. 4-5, particularizing the procedures that,

were necessary to obtain any ruling on the motion for further relief from

the district eourt.

4

11-14 (hereinafter cited as Appellants’ Brief) there are

ambiguous provisions which further underscore the in

adequacy of the plan:

(1) The plan proposes the disestablishment of separate

school zones on a grade-a-year basis. However, the plan

fails to specify whether or not Negro students who reside

within disestablished separate school zones will be assigned

to schools on a nonracial basis. The School Board should

be ordered to initially assign all pupils in grades presently

covered (and those to be covered in future years) under

this plan, on a nonracial basis where Negro pupils have

not availed themselves of the permissive transfer provi

sion.

(2) The provision relating to new pupils entering the

first grade and pupils coming into the school system for

the first time states that these students shall be “admitted

to appropriate school” without discrimination as to race

or color. This provision fails to specify: (a) whether or

not “admission” means that Negro pupils covered there

under are to be initially assigned to schools on a nonracial

basis and/or (b) if Negro pupils are “admitted” to a

school based on the criterion of race, whether or not they

will be eligible to transfer to white schools during their

first year in the system.

Even if ambiguities did not adhere in the present plan,

appellants submit it is still inadequate. The School Board

has designated its plan as a “freedom-of-choice” plan

(see School Board Brief, p. 5). Their plan, however, is

not characteristic of free choice plans as approved in

other cases2 or as adopted by the Department of Health,

2 “ We approve the use of a freedom of choice plan provided it is within

the limits of the teaching of the [Stell v. Savcmnah-Chatham Board of

Education, 333 F.2d 55 (5th Cir. 1964)] and [Gaines v. Dougherty County

5

Education and Welfare (HEW ).3 Rather, the plan is

nothing more than a scheme which continues routine as

signment of Negro pupils to segregated schools with a

“ theoretical” provision allowing Negro pupils to transfer

to a school where they can obtain a desegregated educa

tion. An alleged freedom of choice plan which continues

assignment of Negro pupils on the same racial basis used

when segregation was compelled by state law is insufficient

when proffered and approved as compliance with a school

hoard’s affirmative obligation to establish a desegregated

school system.4 Wheeler v. Durham City School Board,

346 F.2d 768, 772 (4th Cir. 1965); Bradley v. School Board,

Board of Education, 334 F.2d 983 (5th Cir. 1964)] eases. We emphasize

that those cases require that adequate notice of the plan to be given to

the extent that Negro students are afforded a reasonable and conscious

opportunity to apply for admission to any school which they are other

wise eligible to attend without regard to race. Also not to be overlooked

is the rule of Stell that a necessary part of any plan is a provision that

the dual or biracial school attendance system, i.e., separate attendance

areas, districts or zones for the races, shall be abolished contemporane

ously with the application of the plan to the respective grades when and

as reached by it. Cf. Augustus v. Escambia County, . . . And onerous

requirements in making the choice such as are alluded to in Calhoun v.

Latimer, 5 Cir., 1963, 321 F.2d 302, and in Stell may not be required.”

Lockett v. Board o f Education of Muscogee County, 342 F.2d 225, 228-

229 (5th Cir. 1965).

3 The 1965 H.E.W. guidelines clearly provides that in the freedom of

choice plan, if no choice is made, Negro students shall be assigned to the

school nearest their homes or on a basis of nonracial attendance zones.

General Statement of Policies Under Title V I of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 Respecting Desegregation of Elementary and Secondary Schools,

(V,D, 3 (c ) ) , Office of Education, Department of Health, Education and

Welfare.

4 “A system o f free transfer is an acceptable device for achieving a

legal desegregation of schools. . . . In this circuit, we do require the

elimination o f discrimination from initial assignment as a condition of

approval of a free transfer plan.” Bradley v. School Board, supra, 318-

319. “ As we pointed out . . . freedom of transfer out o f a segregated

system is not a sufficient corrective in this Circuit. It must be accom

panied by an elimination o f discrimination in handling initial assign

ment.” Nesbit v. Statesville School Board, supra, at 334.

6

345 F.2d 310, 319 (4th Cir. 1965); Nesbit v. Statesville

City Board of Education, 345 F.2d 333, 334 (4th Cir. 1965).

See Buchner v. County School Board, 332 F.2d 452, 454

(4th Cir. 1964).

Several additional factors demonstrate the plan is not

an acceptable freedom of choice plan. First, the plan fails

to provide for faculty desegregation and is, in this respect,

in conflict with this Court’s recent decision in Singleton v.

Jackson Separate Municipal School District, 355 F. 2d 865

(5th Cir. 1966). See argument infra at page 10. Secondly,

the plan continues the discriminatory “ feeder system” (R.

32). Under this system, when a Negro pupil first enters

the public school system of Leon County he is assigned to

an all Negro school; when he graduates from the elemen

tary school, he is automatically assigned to Negro Junior

High or High School which feeds from the Negro ele

mentary school. Under the feeder system the initial assign

ment determines what schools Negro pupils will attend

during his entire school career, based on long established,

separate school zones for Negro and white pupils set up

by the Board. The feeder system in the instant case is

similar to those held to be constitutionally deficient in

Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, 304 F.2d 118,

120 (4th Cir. 1962); Dodson v. School Board of Charlottes

ville, 289 F.2d 439, 443 (4th Cir. 1961) and Hill v. School

Board of City of Norfolk, 282 F.2d 473, 475 (4th Cir. 1960).

An acceptable freedom of choice plan, is at best, only

an allowable interim measure a school board may use in

fulfilling its obligation to desegregate the school system.

See e.g. Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 355 F.2d 865, 871 (5th Cir. 1966); Bradley v.

School Board, supra at 324 (opinion of Justices Sobeloff

and Bell). The test of whether a freedom of choice plan

is acceptable as an interim measure is among other things,

7

the attitude and purpose of (1) public officials in setting

up the plan, (2) school administrators and faculty in ad

ministering the plan and (3) the effectiveness of such a

plan in disestablishing the segregated school system in a

particular community.5 6

Appellants submit that the School Board plan is un

acceptable because the plan operates to minimize desegre

gation. The record before this Court shows no evidence

that even a free choice plan would be adequate to desegre

gate the segregated public school system in Leon County.6

The present plan has been in operation for over three

years, and only 41 Negro students have made application

to transfer to formerly all-white schools. Of these, only 11

Negroes have been permitted to transfer.

5 “Affirmative action means more than telling those who have been de

prived of freedom of educational opportunity ‘You have a choice.’ In

many instances the choice will not be meaningful unless the administra

tors are willing to bestow extra effort and expense to bring the deprived

pupils up to the level where they can avail themselves of the ciioice in

fact as well as theory.” Bradley v. School Board, supra at 323.

6 As of June, 1964, only 4 Negro children were attending previously

all-white schools in Leon County. (See Appellants’ Brief, p. 6.) The

record on appeal does not disclose the number o f Negroes permitted to

transfer in the 1964-65 school year, however, a letter, dated July 9, 1965

from counsel for the School Board disclosed the following: seven (7)

applications by Negro students for reassignment to previous all-white

schools have been approved, twenty-nine (29) have been denied.

On March 22, 1966, appellants served interrogatories on the School

Board which were designed to elicit the present status of desegregation

under the School Board’s present plan. The School Board refused to

answer the interrogatories and filed objections to said interrogatories in

the court below. The School Board failed to request a hearing in the

district court on the objections to the interrogatories appellants served

on them as required by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

On April 7, 1966, appellants filed in this Court a motion to supple

ment the record on appeal. The intent o f the motion pending in this

Court is to bring before this Court the extent of the present status of

desegregation in Leon County. The information sought in the motion to

supplement the record will aid this Court in the disposition of the appeal

which is set for oral argument on May 2, 1966.

8

Appellants, in their motion for further relief, moved

for a desegregation plan under which the School Board

would be ordered to construct a single system of geo

graphic attendance zones.7 Under appellants’ proffered

plan, Negro and white pupils living within the newly

constructed zones would he assigned to schools based on

a nonracial basis. Appellants’ proposed plan has been

held to be an acceptable desegregation plan. See Bell v.

School Board of Staunton, Va., 249 F. Supp. 249 (W.D.

Va. 1966) in addition to cases cited in Appellants’ Brief,

p. 19. Appellants, in this Court, adhere to their argument

that nonracial assignments by zones is the only means of

obtaining lawful desegregation in Leon County.

B. Current Minimum Standards

Whereas the School Board’s grade-a-year desegrega

tion plan may have been an acceptable plan several years

ago, a consideration of that plan in light of current deci

sions clearly shows it to be woefully inadequate. The

School Board reflects a determination to limit desegrega

tion to a grade-a-year under which desegregation will not

reach all twelve grades until September, 1975. A grade-a-

year plan, if challenged, is not an acceptable desegregation

plan. Price v. Denison Independent School Board, 348

F.2d 1010, 1012 (5th Cir. 1965).

Not only does the School Board fail to show valid ad

ministrative reasons justifying such delay, see Watson v.

City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963) and Bradley v.

7 The present plan provides for elimination of separate attendance zones

for Negro and white pupils; however, the provision relating to the elim

ination of separate school zones is only for the purpose of determining

those grades for which Negro pupils will be allowed the privilege of exer

cising the transfer right. I f a Negro pupil fails to exercise the transfer

privilege, he is automatically assigned to an all-Negro school, even though

he is residing in an area where dual zones have been disestablished.

9

School Board, 382 U.S. 103 (1965), but the School Board’s

plan does not conform to the accelerated standard as to

speed promulgated by this Court in Singleton v. Jackson

Municipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir.

1965), which set a target date of 1967 for total desegrega

tion of public schools. Moreover, this Court has stated

what any desegregation plan should include as a minimum,

namely: (1) desegregation at a speed faster than one

grade per year; (2) assignment without regard to race

to each pupil new to the system not reached by the plan;

(3) simultaneous operation of the plan from both the high

school and elementary end; (4) abolition of dual or biracial

school attendance areas contemporaneously with the ap

plication of the plan to the respective grades; (5) admis

sibility of Negroes to any school for which they are other

wise eligible without regard to race. These minimum

standards were recently confirmed by this Court in Single-

ton v. Jackson Separate Municipal School District, 355

F.2d 865, 867 (5th Cir. 1966). See also, Price v. Denison

Independent School District, 348 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965).

This Court has held that it attaches great weight to the

standards promulgated by the United States Department

of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW), which has the

responsibility for the enforcement of Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964. Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Sepa

rate School District, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965); Price

v. Denison Independent School District, supra at 1013.

Subsequent to the filing of briefs in the instant case, HEW

has issued a revised statement8 accelerating the standards

to which school desegregation plans must comply. The

8 Revised Statement of Policies For School Desegregation Plans Under

Title V I of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, U.S. Department of Health,

Education and Welfare, Office of Education, March 1966. See also Appel

lants’ Brief pp. 17-18.

10

School Board’s plan fails to meet either the minimum

standards set out by this Court or the HEW requirements.

C. Faculty Desegregation Is a Necessary Component

of Valid Desegregation Plan

Appellants have already discussed the error committed

by the court below in refusing to permit any inquiry into

continued segregation of faculty and other school personnel

(Appellants Brief pp. 22-25). This Court, after reviewing

Supreme Court decisions in Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198

(1965) and Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S.

103 (1965) has concluded that school boards must submit

specific plans for faculty desegregation. Singleton v. Jack-

son Municipal Separate School District, 355 F.2d 865 (5th

Cir. 1966). In accord with Singleton, supra, are Kemp v.

Beasley, 352 F.2d 14, 22-23 (8th Cir. 1965); Kier v. County

School Board, 249 F. Supp. 239 (W.D.Va. 1966); and

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W.D. Okla. 1965). Cf. Franklin v. School Board of

Giles County, No. 10,214 (4th Cir. April 6, 1966) (not yet

reported).

Summary

The relief to which appellants are entitled is no less

than that granted in Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Sep

arate School District, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966). For

the reasons stated in this and appellants’ main brief the

judgment of the lower court approving the School Board’s

present plan should be reversed and the cause remanded

with specific directions to the district court to enter an

order enjoining the School Board to submit a desegrega

tion plan under which the School Board would be required

to disestablish separate attendance zones for Negro and

11

white pupils and construct unitary, geographic attendance

areas or zones.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Leroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

T heodore R. Bowers

1018 N. Cove Boulevard

P.O. Box 811

Panama City, Florida

Attorneys for Appellants

Robert Belton

Of Counsel

12

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that a copy of Appellants’ Reply Brief

was served upon William A. O’Bryan, Esq., of Ausley,

Ausley, McMullen, O’Bryan, Michaels and McGeehee, Post

Office Box 391, Tallahassee, Florida, attorneys for appel

lees, by United States mail, postage prepaid, this ...........

day of ............................. , 1965.

Attorney for Appellants

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y.