Objections of Detroit Board of Education to the Alleged Plan of Desegregation Filed by Plaintiffs

Public Court Documents

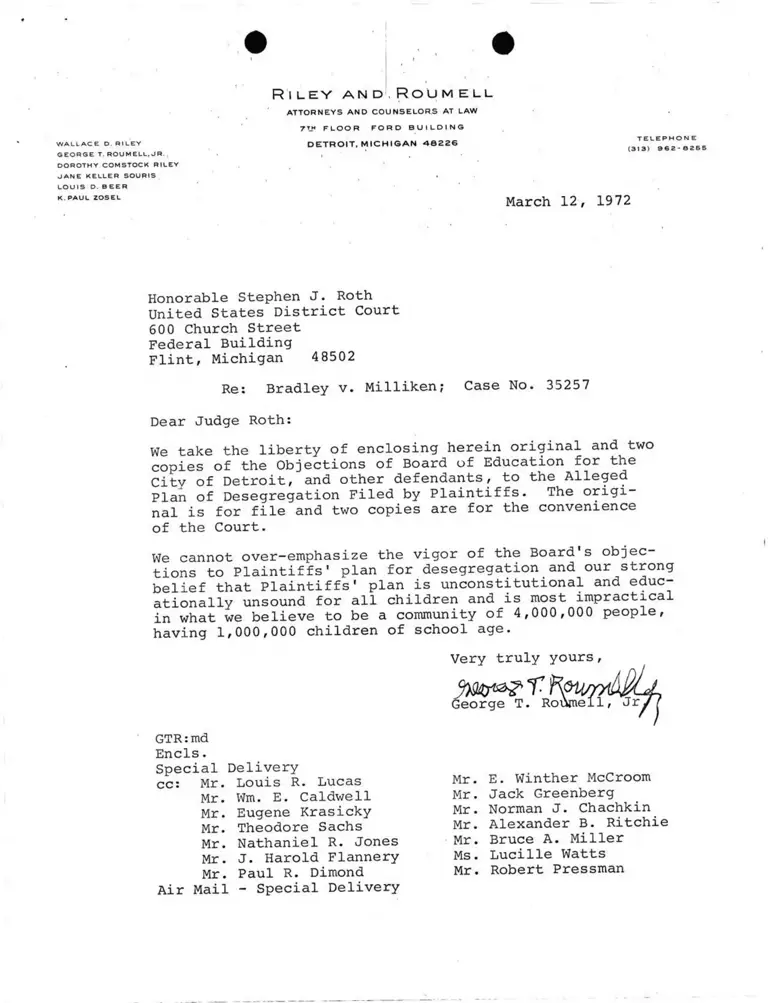

March 12, 1972

13 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Objections of Detroit Board of Education to the Alleged Plan of Desegregation Filed by Plaintiffs, 1972. 5811c9b0-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a2300475-2e87-4a2d-a16b-f76c460faac5/objections-of-detroit-board-of-education-to-the-alleged-plan-of-desegregation-filed-by-plaintiffs. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

R o U m e l l

W A L L A C E D. R I L E Y

G E O R G E T . R O U M E L L , J R . ,

D O R O T H Y C O M S T O C K R I L E Y

J A N E K E L L E R S O U R I S

L O U I S D . B E E R

K . P A U L Z O S E L

R I L EV A ND

A T T O R N E Y S A N D C O U N S E L O R S A T L A W

7 t h F L O O R F O R D B U I L D I N G

D E T R O I T , M I C H I G A N 4 8 2 2 6

March 12, 1972

Honorable Stephen J• Roth

United States District Court

600 Church Street

Federal Building

Flint, Michigan 48502

Re: Bradley v. Milliken; Case No. 35257

Dear Judge Roth:

We take the liberty of enclosing herein original and two

copies of the Objections of Board of Education for the

City of Detroit, and other defendants, to the Alleged

Plan of Desegregation Filed by Plaintiffs. The origi

nal is for file and two copies are for the convenience

of the Court.

We cannot over-emphasize the vigor of the Board's objec

tions to Plaintiffs' plan for desegregation and our strong

belief that Plaintiffs' plan is unconstitutional and educ

ationally unsound for all children and is most impractical

in what we believe to be a community of 4,000,000 people,

having 1,000,000 children of school age.

GTR:md

Ends .

Special Delivery

cc: Mr. Louis R. Lucas

Mr. Wm. E. Caldwell

Mr. Eugene Krasicky

Mr. Theodore Sachs

Mr. Nathaniel R. Jones

Mr. J. Harold Flannery

Mr. Paul R. Dimond

Air Mail - Special Delivery

Mr. E. Winther McCroom

Mr. Jack Greenberg

Mr. Norman J. Chachkin

Mr. Alexander B. Ritchie

Mr. Bruce A. Miller

Ms. Lucille Watts

Mr. Robert Pressman

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

— }

RONALD BRADLEY, et al, )

' )

Plaintiffs, )

vs. ))

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al, )

- )

Defendants, )

and ))

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS LOCAL 231, )

AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO ) No. 35257

)

Intervening Defendant, )

and ))

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al, ))

Intervening defendants. )

)

OBJECTIONS OF BOARD OF EDUCATION FOR THE CITY OF

DETROIT AND OTHER DEFENDANTS TO THE ALLEGED PLAN

OF DESEGREGATION FILED BY PLAINTIFFS_____

The Board of Education of the City of Detroit and

certain individual defendants by George T. Roumell, Jr., Louis D.

Beer and Riley and Roumell, hereby submits to the Court its objec

tions to the alleged desegregation plan submitted by Plaintiffs

and in so doing says as follows:

1 . The Detroit Board of Education objects to the Plaintiffs'

Plan Because It Would Unconstitutionally Convert the School District

into a Racially Identifiable School District.

The Detroit Board objects to the Plaintiffs' plan

because it would turn the Detroit school district into a racially

identifiable district composed solely of racially identifiable schools

in violation of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitution. Even if the racial composition of the district

were not likely to change in direct reaction to the adoption of.

the Plaintiffs' plan, a probability discussed below in Objection II,

the immediate effect of implementing the Plaintiffs' plan would be

to create a district composed of schools whose student populations

would range from 55% black and 45% white to 75% black and 25% white.

In the Detroit Metropolitan Area, a school community with a student

ratio of approximately 20% black and 80% white, all the schools in

Detroit would, under Plaintiffs' plan, be identifiably black. Such

a result, if achieved through state action, would violate the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. See Bradley v.

School Board of the City of Richmond, Va.,___F.Supp.___ (E.D. Va.,

Jan. 5, 1972)(slip op.pp.31;41-2).' Compare Haney V. County Board of

Education of Sevier County, 369 F.2d 364 (8th Cir., 1970)(totally

black district within a white one); United States V. Texas, 447 F.2d

551 (5th Cir.,1971)(totally black districts). In racial matters

the Fifth Amendment restricts the federal government as the Fourteenth

does the states. See Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 98 L.Ed. 884

(1954). Consequently, for the United States District Court to order

an instrumentality of the State of Michigan to adopt the Plaintiffs'

plan would violate both the Fifth and the Fourteenth Amendments.

If the total relevant school population were in

fact 65% black and 35 % white, the Plaintiffs' plan would obviously

not be unconstitutional. But for the reasons adduced in the Detroit

Board's Objections to the State Plan (pp. 2-3), the relevant school

population is that of the tri-county Detroit Metropolitan Area. With

in that natural school community the Plaintiffs' plan would carve

out a racially identifiable, predominately black, district. See

Haney v. County Board of Education of Sevier County, supra;

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, Va., supra. It

would do this by following and reinforcing known patterns of housing.

- 2 -

See Bradley v. MilTiken, 438 F.2d 9 46 (6th. Cir. , 1971) , Judge

Keith's ruling in Davis v. School District of Pontiac, 309 F. Supp.

734 (E.D.Mich.1970), aff' d 443 F.2d 573, cert, denied, 91 S.Ct. 233

(1971), is as pertinent to a federal court as to a school board:

"For a school board to acquiesce in a housing

development pattern and then to disclaim res

ponsibility for the eventual segregated charac

teristic that such pattern creates in the

schools is for the Board to abrogate and ignore

all power, control and responsibility. A Board

of Education simply cannot permit a segregated

situation to come about and then blithely an

nounce that for a Negro student to gain atten

dance at a given school all he must do is live

within the school's attendance area. To

rationalize thusly is to be blinded to the real

ities of adult life with its prejudices and op

position to integrated housing."

See also United States v. School District No. 151, 286 F.Supp. 786,

799 (N.D. 111.), aff'd 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir., 1968); Keyes v.

School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 303 F. Supp. 279, 289 (D.Colo.), rev'd

on other grounds, 445 F. 3d 990 (10th Cir., 1971) , cert, granted,

____U.S. ___(1971); Brewer v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk,397 F.2d

37 (4th Cir.1968); Sloan v. Tenth School District of Wilson County,

443 F.2d 587, 589 (6th Cir.1970).

It is no justification of the Plaintiffs' plan that

it follows existing political boundaries. While neither the Detroit

Board nor the State defendants concede the correctness of this

Court's finding that they have segregated black students, any reme

dial plan must be discussed on the assumption that the Court's

finding is warranted. The finding of State involvement in the

asserted segregation is particularly important as it involves all

the people of the Detroit Metropolitan Area, through their elected

representatives, in the creation of the problem. "Where a pattern

of violation of constitutional rights is established the affirmative

obligation under the Fourteenth Amendment is imposed on not only

individual school districts, but upon the State defendants in this

case." Cooper v. Aaron,35 8 U.S. 1 (1958) ; Griffin v. County School

3

Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964). As Judge Merhige

has noted, the obligation of the various public officials and bodies

in a metropolitan area "toward the individual school children is

a shared one." Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, Va.,

51 F.R.D. 139, 143 (1970). As a matter of hornbook law, but par

ticularly where federal constitutional rights are at stake, "school

district lines within a state are a matter of political convenience."

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 448 F.2d 746, 752 (5th Cir.,1971).

"Political subdivisions of states— counties, cities or whatever--

never were and never have been considered as sovereign entities"

and hence may readily be crossed when necessary to vindicate federal

constitutional rights. Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 575 (1964).

See Jenkins v. Township of Morristown School District and Bd. of

Educ., 279 A.2d 619 (N.J., June 25, 1971). While the Detroit Board

feels that existing school districts can serve valid functions after

a remedial decree is issued, it does not see any justification for

stopping any relief at a political boundary absent valid educational

or legal reasons to do so. On the contrary it feels reasons of con

stitutional magnitude require that the entire metropolitan area be

involved in any remedy.

II. The Detroit Board of Education Objects To Plaintiffs1

Plan Because It Would Not In Fact Provide a Remedy.

Before the implementation of this suit and since,

the Detroit Board has expressed its commitment to ending racial

separation in schools, regardless of cause. While the Detroit Board

does not concede that it has committed any acts justifying a judicial

remedy, it has an obligation to all the people of Detroit to seek

to assure that any remedy imposed will in fact correct the alleged

- 4 -

conditions complained of. This obligation is the stronger as

the Detroit Board may be required to comply with any remedial

decree while appealing its appropriateness. Alexander y. Holmes

Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S.19(1969). Just as the Detroit Board has an

affirmative obligation to propose a meaningful solution, it feels

it has an obligation to assist the court to fulfill its duty to

assess the effectiveness of other plans in achieving the constitu

tionally required unitary system.. Swann v. Charlotte Mechlenburg

Bd. of Educ., 91 S.Ct.1267 (1971); Davis v. Board of School Commis

sioners of Mobile County, 91S Ct .1289 (1971) ; Green v. County School

Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 885 Ct. 1689(1968). Such an

assessment must be made in light of the existing circumstances and

the alternatives available in such instance, Swann, supra; Davis,

supra; Green, supra.

With its obligations to the Court and to the people

of Detroit firmly in mind, the Detroit Board objects to the Plain

tiffs1 plan because it would not in fact remedy the separation of

black pupils from white pupils. It would not eliminate the alleged

state causation of that separation; it would merely add federal

causation.

Immediate implementation of the Plaintiffs' plan

would not eliminate a single identifiably black school in Detroit.

Rather it would create more. It would make all schools in Detroit

identifiably black in the perception of both the black and the white

segments of the community. At the same time it would leave the

vast majority of white pupils in the metropolitan area in predomi

nately or totally white public schools, in racially identifiable

schools. The failure of the Plaintiffs' plan would not only be

predictable the day it was approved, it would become increasingly

5

obvious as the black and white citizens of the Detroit Metropolitan

Area reacted to it. The reactions of both groups are perfectly

predictable. Even before the Plaintiffs' plan could be implemented,

white parents facing the prospect of sending their children to pre

dominately black Detroit schools would leave Detroit. They would

not leave the Metropolitan area. They would move to the havens the

Plaintiffs' plan leaves in the suburbs. As a result, the racial

ratio for the first year of operation under the Plaintiffs' plan

would be a good deal less white than the present figures would leave

one to believe. It is not hyperbole to suggest that hy the time the

appeals will be concluded, "white flight" would have made the entire

district closer to the 90% black schools repeatedly referred by by

plaintiffs counsel and witnesses in examining witnesses. See, eg

Tr. 836-37; 84 - 43; 854-55.

It is equally predictable that black parents would not

join the rush to the suburbs. It is a widespread belief in the

local black community that black movement to most suburbs is deli

berately frustrated in a host of ways and that blacks must pay more

than whites for such housing as they do have accesss to. Besides,

with so many whites leaving, housing opportunities for blacks in

Detroit would improve. This in fact is the well-known pattern

in neighborhood after neighborhood within Detroit.

Judge Merhige in Bradley v. School Bd. of the City of

Richmond, Va. could have been describing the Detroit Public Schools

of 1975 when he wrote: "The departure of whites, as has occurred

in the City, in the face of an increasing black component, was pre

dictable, but it was only possible — and only had reason to occur —

when other facilities, not identifiable as black, existed within

what was in practical terms, for the family seeking a new residence,

6

the same community. School authorities cannot but have been aware

from their experience of the tendency of individual facilities

within each segregated system to take on a label of racial identi-

fiability. Given the shifting demographic patterns it was fully

foreseeable, and was foreseen, that more and more schools in the

city, new and old, would become black and in the (suburbs) most

facilities, including new ones, would be obviously white."

F.Supp. ___(E.D. Va., Jan. 5, 1972) slip op. at p.42.

III. The Detroit Board Objects to the Plaintiffs1 Plan

Because, Without Adequate Reason, It Fails to Provide the Greatest_

Possible Degree of Actual Desegregation.

"Having once found a violation, the district judge

or school authorities should make every effort to achieve the great

est possible degree of actual desegregation,taking into account the

practicalities of the situation." Davis v. Board of School Commis

sioners of Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33, 91 S.Ct. 1289 at 1292(1971).

In Metropolitan Detroit desegregation of the entire school community

would approximate a ratio of 80% white and 20% black. To settle

for anything less the Court must find major obstacles in "the prac

ticalities of the situation."

Physical and time obstacles are not significant in

this area. The Metropolitan Area is generously supplied with free

ways and other major arteries extending fanlike out of Detroit.

Travel between the central city and the suburban areas is extensive

and not overly demanding. In 1965, before the present freeway net

was completed, the Detroit Regional Transportation and Land Use

Study (TALUS) concluded,

7

, . "The pattern of movement by persons in the

study area... is characterized by uniformly

heavily loaded links in the central city and

immediately adjoining suburban areas with the

most heavily loaded links extending radially

outward from the CBD (Central Business District)

... The general pattern of movement is one of

interaction of the suburban counties with the

central city... A comparison of auto driver

trip lengths in 1953 and 1965 shows a substan

tial increase in the average trip length in

miles for all four trip purposes analyzed....

The increase in trip length measured in minutes,

however, was much less....The minimal increases

in travel time despite substantial increases

in the average distance traveled were made pos

sible by the development of an extensive free

way network and by improvements to arterial

streets."

Base Year Travel Study pp. 11-12 (1969). TALUS was a special project

of the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments. The "study area"

included Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb Counties, as well as portions

of adjacent counties.

If the highway network is adequate for the other

business of the area it is adequate for its school affairs as well.

Nor is time likely to be a factor which would interfere with the

health or education of the children transported under a metropolitan

plan. See Swann v. Charlotte -Mechlenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 US 1,

91 S.Ct. 1267 at 1283 (1971) . The State of Michigan routinely funds

the transportation of children one and a half hours each way without

noting any hazard to health or education. See Hain, The Law of

Desegregation, 18 Mich. School Bd. J. 18 (Dec. 1971). In this con

nection it might be noted that Southeastern Michigan has the mildest

climate in the state.

Political boundaries are not significant barriers

either. School district boundaries in Michigan are infrequently

coterminous with other political boundaries, although Detroit is an

exception to the rule. Municipal budgets and affairs are not bound

8 -

up with those of school districts in Michigan. The state obviously

treats school districts as administrative conveniences. See, e g,

Detroit Bd. of Educ. v. Superintendent of Public Tnstr., 319 Mich.

436 at 449 (1947).

Administrative convenience does not supply the over

riding state interest necessary to justify infringement on the fund

amental interest in equal educational opportunity. Compare Reynolds

v. Sims, 377 US 533(1964)(allocation of voter representation);

Verner Sherbet, 384 U.S. 398, 506-7, 10 L. Ed. 2d 965, 972 (1963)

(exercise of religion). As early as Brown v. Board of Educ., 349

U.S. 294 at 300-01, 75 S. Ct. at 756 (1955) the Supreme Court has

suggested that the revision of school districts might be necessary

to assure that school systems operate on constitutional principles.

Where political boundaries effectively allocate separate portions

of public goods to whites and blacks, courts can redraw them. See

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960)(municipal boundaries);

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier County, 364 F2d 364 (8th

Cir.1970)(school districts); United States v. Texas, 447 F2d 441

(5th Cir.1971)(school districts) Where proposed new boundaries

unevenly apportion racial groups among school districts they are

suspect and may be enjoined. Turner v. Littleton - Lake Gaston

School Dist. 442 F2d 584 (4th Cir. 1971).

Finally, suburban opposition to integration, cannot be

considered a barrier to court-ordered integration. Even violent

opposition is insufficent justification for the denial of a full

measure of constitutional rights. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958).

No other practical objections springing readily to mind,

the Detroit Board objects to the inadequate degree of actual dese

gregation proposed by the Plaintiffs' plan.

9 _

IV. The Detroit Board Objects to the Plaintiffs'

Plan Because it Is Not Desicrned for Transition to a Metropolitan

Plan.

The Detroit Board believes the only practical plan

and the only constitutional plan is a metropolitan plan. Yet con

ceding that an interim plan may be desirable (a question upon which

it has major reservations), it asserts that the true test of any

interim plan must be whether it will enhance or retard the imple

mentation of a final plan. The Plaintiffs* plan is, by admission,

not designed to lead to a metropolitan plan. See Desegregation

Plan, Detroit Public Schools (February 22, 1972) p.4. In fact, it

is so inconsistent with any metropolitan plan that might be envi

sioned that it could only cause a period of upset between the termi

nation of litigation and the beginning of a truly effective plan.

In this respect it can only increase the tensions and apprehensions

of the community. It would lack the sense of finality so important

in persuading students and the general public to accept the change

and to build constructive new relationships. In this respect the

Plaintiffs' plan is far more undesirable than the State Plan to

which the Detroit Board has objected already.

Any interim plan which creates a pupil population in any

school for the interim period substantially at a variance from the

pupil population expected for that school under the ultimate plan

is an unsatisfactory plan. It will leave the students at that

school in a state of unrest and uncertainty which is hostile to the

educational goals of cognitive learning and inter-racial amity. A

Year spent waiting for the other shoe to fall will be, at best, an

unfruitful year. More likely it will be a barrier to progress.

10

V

Plan Because it Will Lead to Systematically Inferior Education

for Black Students.

An identifiably black school district, such as the

Plaintiffs' plan would create, would have a harmful effect on the

black students of Detroit. Plaintiffs' expert, Dr. Robert Green,

testified to the importance of mutli-racial classes (Tr. 982-3).

He asserted that decentralization along racial lines would be

"disfunctional", while "multi-racialism" would make decentraliza

tion acceptable. (Tr. 1019) . Dr. Green expressed his expert

opinion that attendance at racially identifiable schools adversely

affects the black students' academic and occupational aspirations.

(Tr. 866-68). Similar poor performance can, Dr. Green said, be

expected from integrating low socio-economic status whites and low

socio-economic status blacks.(Tr. 1009-10) A high percentage of

those whites left in Detroit are of low socio-economic status.

Dr. Green also asserted that racially identifiable schools are

perceived by black persons, students and adults, as related to allo

cations of resources skewed unfavorably to blacks. (Tr. 869-71).

As Dr. Green's discussion of attendance zones (Tr. 1023-25) and

decentralization (Tr. 911-13; 1019) indicates, the existence of

political boundaries is unlikely to alter the unfavorable percep

tions by blacks. Indeed this Court, by its findings in this case,

has confirmed suspicion that the State as a whole might discriminate

against black students or the Detroit School District. Ruling on

Issue of Segregation, pp. 14-15, September 27, 1971. Finally, the

Plaintiffs' expert, Dr. Green, has testified that teacher attitudes

are worse and their expectations for their students are lower in

predominately black schools. (Tr. 863-64; 921; 988-92; 1032-36).

Low teacher expectations translate into low student performance.

• The Detroit Board Objects to the Plaintiffs'

11

In sum, the Detroit Board of Education opposes

implementation of the Plaintiffs' plan on the grounds that it

would create a segregated school district offering an inferior edu

cation. Dr. Green labeled the political concept of community control

"a policy of despair" (Tr. 912-13). Adoption of the Plaintiffs’

plan would be a similar policy.

Respectfully submitted,

RILEY AND ROUMELL

And Louis D. Beer

720 Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Telephone: 962-8255

Date: March 12,1972

12