Pulaski County Special School District No. 1 v. Little Rock School District Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

February 5, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Pulaski County Special School District No. 1 v. Little Rock School District Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1986. ac5aac9f-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a2300f92-38f5-4c95-ad39-6314601218d7/pulaski-county-special-school-district-no-1-v-little-rock-school-district-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

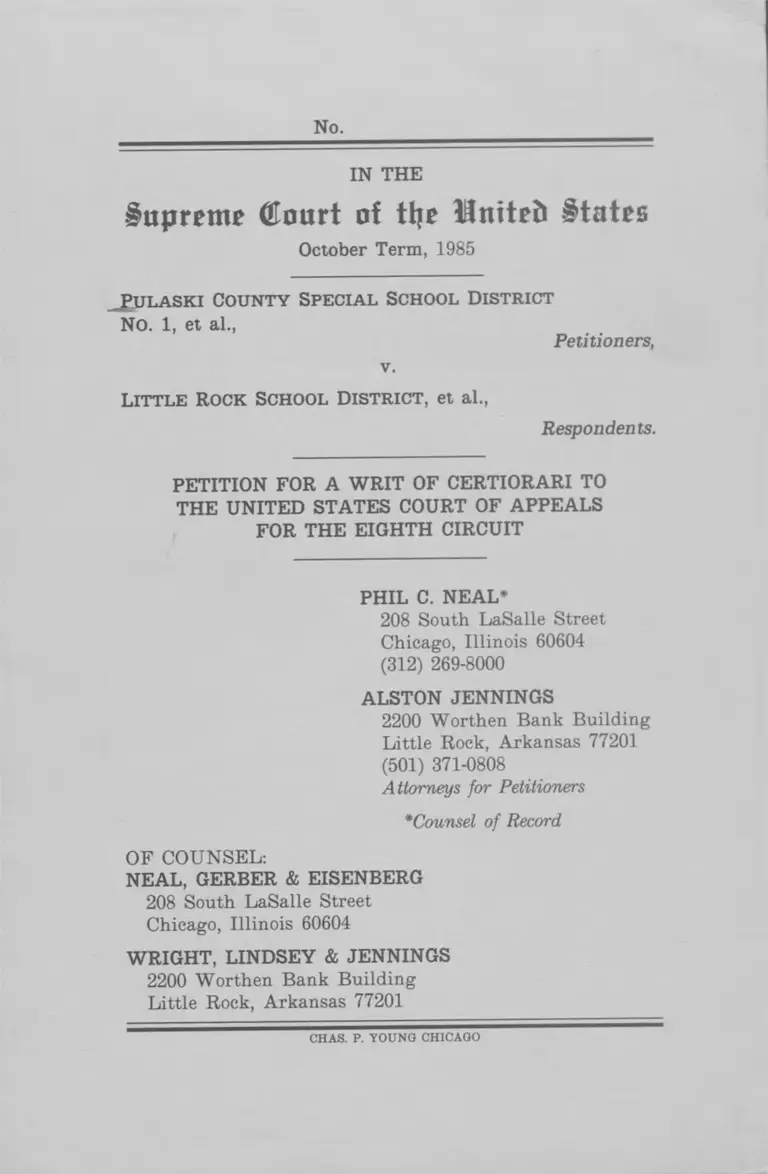

No.

IN THE

§upreme (Eourt of tlje Hnttefc §tates

October Term, 1985

Pu l a s k i Co u n t y Sp e c ia l Sch o o l Dis t r ic t

No. 1, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Lit t l e Ro c k Sch o o l Dis t r ic t , et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

PHIL C. NEAL*

208 South LaSalle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60604

(312) 269-8000

ALSTON JENNINGS

2200 Worthen Bank Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 77201

(501) 371-0808

Attorneys for Petitioners

*Counsel of Record

OF COUNSEL:

NEAL, GERBER & EISENBERG

208 South LaSalle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60604

WRIGHT, LINDSEY & JENNINGS

2200 Worthen Bank Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 77201

CHAS. P. YOUNG CHICAGO

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Can the proof of interdistrict effects required by Mil-

liken v. Bradley as a condition for interdistrict relief in a

school-desegregation case be satisfied by conjecture as to pos

sible demographic effects, absent any specific evidence of

actual effects?

2. May a federal court revise the boundaries of

independent and autonomous school districts on the ground

that a school district has not voluntarily deannexed parts of its

district, and even though it was never requested to do so?

11

PARTIES

Petitioners Pulaski County Special School District No. 1

and its Board of Directors, Mac Faulkner, Charles Stratton,

Bennie O’Neil, Mack McAllister, Sheryl Dunn, David Sain,

and Mildred Tatum; respondent Little Rock School District;

and respondents Lorene Joshua, as next friend of minors

Leslie Joshua, Stacy Joshua and Mayne Joshua; Rev. Robert

Willingham, as next friend of minor Tonya Willingham;

Sara Matthews, as next friend of Khayyan Davis, Alexa

Armstrong and Karlos Armstrong; Mrs. Alvin Hudson, as

next friend of Tatia Hudson; Mrs. Hilton Taylor, as next

friend of Parsha Taylor, Hilton Taylor, Jr. and Brian

Taylor; Rev. John M. Miles, as next friend of Janice Miles,

Derrick Miles; Rev. Robert Willingham, on behalf of and as

president of the Little Rock Branch of NAACIP; and Lorene

Joshua, on behalf of and as president of the North Little

Rock Branch of the NAACIP, were parties to the proceed

ings in the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals. Additional

parties to the consolidated proceedings in the Court of

Appeals appear in the Appendix at pages A-2 through A-3.

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Table of Authorities.................................................... iv

Opinions Below............................................................ 1

Jurisdiction.................................................................. 1

Constitutional Provision Involved............................ 2

Statement of the Case................................................ 2

Reasons for Granting the W rit ................................ 6

Conclusion.................................................................... 14

Appendix:

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit, dated November 7, 1985. . A-l

Memorandum Opinion of the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of

Arkansas, dated April 13, 1984 .................... A-87

Judgment Order of the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas,

dated November 19, 1984 ...................................... A-145

Memorandum Opinion of the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of

Arkansas, dated November 19, 1984 .................... A-147

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE

A rm our v. Nix, No. 16708, slip op. (N.D. Ga. Sept. 24,

1979), aff’d, 446 U.S. 930 (1980).................................. 6

Clark v. Bd. of Edue. of Little Rock School Disk, 705 F.2d

265 (1983)....................................................................... 3

Goldsboro City Bd. of Educ. v. W ayne Cty. Bd. of Educ.,

745 F.2d 324 (4th Cir. 1984)...................................... 6, 13

Lee v. Lee Cty. Bd. o f Educ., 639 F.2d 1243 (5th Cir. 1981) 6, 9

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974)... 6, 7,10,11,12,13,14

Pasadena City Bd. of Educ. v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424

(1976) ............................................................................. 11

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1

(1971)............................................................................. 10

United States v. Bd. of School C om m ’rs of City of Indi

anapolis, 637 F.2d 1101, (7th Cir. 1979), cert, denied,

449 U.S. 838 (1980)...................................................... 11

Village o f Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing De

velopment Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977).......................... 12

Zinnamon v. Bd. of Educ. of Pulaski County School Disk,

No. LR-68-C-1154 (E.D. Ark.) 3

No.

IN THE

§upreme (Eourt of United §tates

October Term, 1985

Pu l a s k i Co u n t y Sp e c ia l Sch o o l Dis t r ic t

No. 1 , et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Lit t l e Ro c k Sch o o l Dis t r ic t , et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals (Appendix, pp.

A -l— A-86) is reported at 778 F.2d 404. The April 13, 1984

opinion of the district court (Appendix, pp. A-87— A-144) is

reported at 584 F.Supp. 328. The Judgment of the district

court, dated November 19, 1984, is reproduced in the

Appendix at pages A-145— A-146. The November 19, 1984

opinion of the district court (Appendix, pp. A-147— A-160) is

reported at 597 F.Supp. 1220.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

November 7, 1985. The jurisdiction of this Court is based on

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

2

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION INVOLVED

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Consti

tution provides, in pertinent part: “ [No State shall] deny to

any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the

laws.”

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Public schools in Pulaski County, Arkansas, are operated

by three separate school districts: the Little Rock School

District (“ Little Rock District” or “ LRSD”), the North Little

Rock School District (“ North Little Rock District” or

“ NLRSD”) and the Pulaski County Special School District

(“ Pulaski District” or “ PCSSD”). The cities of Little Rock

and North Little Rock are contiguous but are separated by

the Arkansas River. The city school districts, LRSD and

NLRSD, lie generally within the boundaries of the respec

tive cities. PCSSD surrounds the other two school districts

and serves all of the rest of Pulaski County, an area of 744

square miles, much of it rural and sparsely populated.

Approximately 10,000 students are enrolled in NLRSD,

20,000 in LRSD, and 30,000 in PCSSD.

In Arkansas, school districts are, and long have been,

separate and autonomous units of local government.

Boundaries of school districts do not necessarily follow the

boundaries of cities or other governmental units, and that is

the case with each of the three school districts in Pulaski

County. Special statutory provisions govern the procedures

for annexation and deannexation of school district territory.

PCSSD was created pursuant to legislative authorization

in 1927, resulting in the consolidation of a number of small

rural school districts. Its boundaries as originally defined

included all of Pulaski County outside the cities of Little

Rock and North Little Rock. At various times since then,

the boundaries of the City of Little Rock have expanded by

annexation. At various times subsequent to these city annex

ations, parcels within the expanded city boundaries were

3

deannexed from the Pulaski School District and annexed to

the Little Rock School District. There have been no such

deannexations from PCSSD to LRSD since 1968, although

expansions of the City of Little Rock have taken place since

that date. Deannexations of property from a school district

can occur only on the petition of the majority of the qualified

electors or property owners in the area to be deannexed,

followed by approval of the school boards of the affected

school districts. There have been no petitions for deannexa

tion of property from PCSSD to LRSD since 1968. Until the

mid-1960’s the Pulaski District was inadequately financed

and its schools were generally considered inferior to the

public schools of Little Rock for white as well as black

children. Since that time, aided by expanding population

and a growing tax base, PCSSD has developed into a strong

public school system that is highly regarded and strongly

supported by the parents of both races.

Each of the three school districts has been under its own

comprehensive desegregation plan, pursuant to court decree,

since the early 1970’s. Each of the plans has required large-

scale busing, still in effect, and has resulted in desegregation

at all levels. The latest modification of the LRSD decree

occurred in 1983. Clark v. Bd. of Educ. of Little Rock School

Dist., 1705 F.2d 265 (8th Cir. 1983). The desegregation plan

in PCSSD was ordered by decrees entered in 1971 and 1973

in Zinnamon v. Bd. of Educ. of Pulaski Cty. Sch. Dist., No. LR-

68-C-154 (E.D. Ark.). There have been no further judicial

proceedings with respect to that decree since its entry. None

of the three districts has been declared unitary.

As a result of the desegregation plans implemented under

the separate decrees, each of the three districts is substan

tially desegregated. By the index of desegregation used by

the Office of Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Educa

tion, each of the three districts has been over 90 (on a scale of

0-100) in all years since 1975.

In the past decade the number and percentage of black

students in the Little Rock schools have steadily increased.

4

Between 1973 and 1981 the percentage of black enrollment

grew from 48% to 65%. The change has been due both to an

increase in the number of black students and a decrease in

the number of whites. The change reflects population

changes; from 1970 to 1980, according to census figures, the

white population in the district decreased by about 7% while

the black population increased by about 44%. The popula

tion of white school-age children decreased at an even greater

rate than the white population as a whole. During the same

period the number of white students in Little Rock attending

private schools also increased dramatically.1

There is no evidence that the increasing black percentage

of students in the Little Rock District is due in any signifi

cant degree to the removal of white students from LRSD

schools to those of PCSSD. The available evidence shows

that over the twelve-year period 1971-83, 958 white students

and 866 black students previously enrolled in LRSD became

enrolled in PCSSD. The Pulaski District, like the Little

Rock District, has been steadily increasing in black enroll

ment, which increased from 18% to 22% over the last dec

ade. During that period PCSSD has lost approximately

1,500 white students and gained the same number of black

students.

The present action was brought in 1982 by the Little Rock

School District against the defendant districts, seeking a

consolidation of all three districts. The jurisdiction of the

district court was invoked under 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331(a), 1343(3)

and (4), 2201, and 2202. The State of Arkansas and the

Arkansas State Board of Education were also named as

defendants. Prior to trial the State of Arkansas was dis

missed from the action on the ground of sovereign immunity.

After a hearing limited to the issue of liability, the district

court entered findings and an opinion determining that the 1

1 According to census figures, if all the white school-age chil

dren in the Little Rock District had been attending public

schools in 1980, the composition of the public schools in LRSD

would have been approximately 52% white.

5

defendant districts had engaged in interdistrict constitu

tional violations, and concluding by ordering consolidation

of the three districts.2 Further hearings were held directed

to remedy. Thereafter, the district court entered further

findings, adopting a consolidation plan proposed by the

plaintiff’s expert witness. Concurrently, the court entered

further findings determining that the State also was liable

for interdistrict violations, and retaining the State Board of

Education as a party for the purpose of further remedial

orders.

On appeal, a divided court of appeals, sitting en banc,

reversed the order of consolidation but affirmed the determi

nation of interdistrict liability and ordered, in part, that, the

boundaries of PCSSD be made coterminous with those of the

City of Little Rock by transferring from PCSSD to LRSD all

of the area within the city’s boundaries that is part of the

Pulaski District.3 The court was unanimous on the issue of

reversing the consolidation order.

The majority opinion of the court of appeals was joined by

five members of the court. Three judges dissented (in two

opinions) from the majority’s major conclusions as to

interdistrict liability and from the order requiring cotermi

nous boundaries. A fourth judge concurred, on grounds dif

ferent from those relied on by the majority, in the portion of

the court’s order requiring boundary changes but dissented

2 The court stated orally: “ I want the attendance zones to be

set up in such a way that there will be racial balance in all of

the schools of this [consolidated] District.” (Tr. 4/20/84 at p. 2.)

3 The court also ordered that one particular area, Granite

Mountain, be transferred from LRSD to PCSSD, on the ground

that the annexation of this area to the Little Rock District in

1953 was a discrete interdistrict violation. Additionally, the

court of appeals ordered that the State of Arkansas be required

to fund the cost of transportation and supplementary educa

tional costs for any students electing voluntary interdistrict

transfers, and to pay one-half the cost of any countywide

magnet schools that might be created.

6

from the other portions of the remedial order and from much

of the majority’s opinion relating to interdistrict liability.

The boundary change ordered by the court of appeals

would result in the transfer from PCSSD to LRSD of over

one-fourth of the schools in PCSSD and in the reassignment

of a large proportion of the 8,000 students currently attend

ing those schools.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

Certiorari should be granted because the decision of the

court of appeals orders drastic interdistrict relief in a school

desegregation case on grounds fundamentally inconsistent

with this Court’s decision in Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717

(1974), and is in conflict with the interpretation of that

decision by the Fourth and Fifth Circuits. Goldsboro City Bd.

of Educ. v. W ayne Cty. B d of Ed., 745 F.2d 324 (4th Cir. 1984);

Lee v. Lee Cty. B d of Educ., 639 F.2d 1243 (5th Cir. 1981). The

decision is also inconsistent with Armour v. Nix, 446 U.S. 826

(1980), in which this Court summarily affirmed the decision

of a three-judge district court holding that Milliken v. Bradley

barred metropolitan relief in the city of Atlanta under cir

cumstances very similar to those in this case. A rm our v. Nix,

No. 16708, slip op. (N.D. Ga. Sept. 24, 1979).

In Milliken v. Bradley this Court held that “ [bjefore the

boundaries of separate and autonomous school districts may

be set aside” there must be proof of “racially discriminatory

acts” within one district that produce a “ significant segrega

tive effect” in another district, and that the remedy must be

one that eliminates the interdistriet segregation “ directly

caused” by the constitutional violation. 418 U.S. at 744-45.

In Lee v. Lee County the Fifth Circuit interpreted the

Milliken decision to mean that where an interdistriet remedy

is requested “ there must be clear proof of cause and effect and a

careful delineation of the extent of the effect.” 639 F.2d at 1256

(emphasis added). Accord, Goldsboro City Bd. of E d v. W ayne

County Bd. of Ed., supra.

7

A careful examination of the opinion of the court of

appeals discloses no findings of fact, either by the district

court or by the court of appeals, that furnish a factual

predicate for an interdistrict violation as defined by this

Court or for the remedy ordered by the court of appeals.

The effort of the court of appeals to piece together genera

lized findings of the district court and supplementary find

ings of its own reveals clearly that the decision as a whole is

an attempt to circumvent the underlying principle of the

Milliken case, and to redress the changing racial composition

of Little Rock’s schools by measures unrelated to any proven

causal relationship between any constitutional violation and

any interdistrict segregative effects.

In substance, the decision invokes the power of the federal

courts for the purpose of offsetting demographic trends, pres

ent in all metropolitan areas of the United States, that have

led to increasing percentages of minority students in the

public schools of the cities. If the tenuous bases for finding

interdistrict violations and effects relied on by the court of

appeals in this case can satisfy the requirements of the

Milliken decision, the way is open for redrawing school-

district boundaries in many, if not most, metropolitan areas

of the country for the purpose of achieving racial balance by

busing students over ever-wider areas.

The interdistrict violations purportedly relied on by the

court of appeals fall into four categories: (1) the long history

of efforts by the State of Arkansas to maintain segregated

schools, particularly in Little Rock; (2) intradistrict viola

tions that are presumed to have attracted blacks to the Little

Rock District and whites to the Pulaski District; (3) dis

criminatory housing practices attributable to the State; and

(4) the failure of the Pulaski District to deannex portions of

the district that were annexed by the City of Little Rock but

were not annexed by the Little Rock School District. To

overcome manifest deficiencies in fact findings by the district

court as to the segregative effects of any such violations, the

court of appeals additionally relied on census statistics (not

8

relied on by the district court and not found in the record)

showing that Little Rock’s black population increased at a

greater rate than the rest of the County’s, and the County’s

white population at a greater rate than Little Rock’s, over

the period from 1950 to 1980. (Appendix at A-14, n.6 and

A-23, n.8.)

None of the findings in the first three categories are suf

ficient to establish an interdistrict constitutional violation.

As to the fourth, the finding concerning the maintenance of

the school-district boundary lines necessarily implies that a

school district has an affirmative duty to alter its boundary

lines to improve racial balance in an adjoining district, and is

erroneous as a matter of law.

1. Both the district court and the court of appeals recited

at length the history of school segregation in Arkansas and

the efforts of the State and its officials to obstruct desegrega

tion in Little Rock after Brown v. Board of Education. But

there are no findings of fact by either the district court or the

court of appeals that support the existence of any substantial

present effect of those actions on the respective racial

percentages of the Little Rock School District and the

defendant school districts. And, with one exception, there is

no finding that the State of Arkansas either drew or altered

district lines with any discriminatory purpose.4

The court of appeals pointed to the fact that when Little

Rock schools were closed during the year 1958-59, students

from those schools attended the Pulaski District schools, and

that some interdistrict transfers of students occurred until

4 The exception is the so-called Granite Mountain area, which

was transferred from the Pulaski District to the Little Rock

District in 1953, in connection with the building of a public

housing project. See supra, p. 5, n.3. Assuming arguendo that an

adequate finding of segregative purpose was made or could be

made (but see Bowman, J., dissenting, Appendix at A-85), this

violation would support at most the re-transfer of that area,

which the court of appeals separately ordered.

9

1965. Appendix at A-25.5 But there are no concrete findings

as to the present effect of any such transfers on the present

residential populations of either school district.6 The court

of appeals’ generalized conclusion that these events, remote

in time, “ had a substantial and continuing effect on the

racial composition of LRSD” (Appendix at A-23, n.8) is

unsupported by any specific findings of fact or by evidence in

the record, as is forcefully pointed out in the separate opin

ion of Judge Arnold. (Arnold, J., Appendix at A-68— A-70,

A-74— A-76; see also Gibson, J., dissenting, A-80— A-82).

2. Both the district court and the court of appeals

purported to find “ interdistrict violations” on the part of the

Pulaski District in the existence of a substantial number of

schools whose racial composition departed from the range

prescribed by its own desegregation decree, disproportionate

busing burdens on black students, failure to meet goals for

the hiring of black teaching and administrative personnel,

disproportionate classification of black students into

remedial education programs, failure to develop special pro

grams for black students, and failure to appoint a bi-racial

committee. There is no finding by either the district court or

the court of appeals that any of these deficiencies was

attributable to purposeful racial discrimination, and there

fore an essential element of a constitutional violation is

absent on this record. That defect aside, there are no factual

findings (and no evidence in the record) to establish any

5 There is no finding that more blacks than whites transferred

from PCSSD to LRSD. See opinion of Arnold, J., Appendix at

A-69, n.4.

6 As the Fifth Circuit concluded in Lee v. Lee Cty. Bd. of Educ.,

639 F.2d 1243, 1260 (1981):

[T]he fact that an interdistrict transfer program was

formerly used in order to maintain racial segregation in

districts operating dual school systems does not support an

interdistrict order unless it is established that these trans

fer programs have a substantial, direct, and current segre

gative effect.

10

causal connection between any such intradistrict violations

and the increasing proportion of black students in the Little

Rock District. The court’s recital of these “ violations”

(Appendix at A-31— A-32, pars. 2-8) makes no attempt to

establish any interdistrict effects caused by these intradistrict

violations and points to no such findings by the district court.

The court’s theory apparently was that any such intradis

trict violations must have made the schools of the Pulaski

District less attractive to black families and therefore must

have caused migration of population to Little Rock and away

from the Pulaski District. If that theory alone, unsupported

by any evidence that such movement actually took place, can

support the finding of an interdistrict violation, it means

that proof of an interdistriet violation requires no more than

proof of an intradistrict violation. Such a rationale renders

meaningless the holding of the Milliken case.

The court of appeals also relied on findings that new

schools had been sited in outlying areas of predominantly

white population.7 Here the court’s theory was that the

existence of such schools must have caused in-migration of

whites to the County rather than the city (white “ over

flight”) and thus increased the racial imbalance as between

the county and city districts. There were no findings and no

evidence of any such effect, let alone of the probable magni

tude of any such effects if they did exist.8 In the absence of

7 Once again, there was no finding and no evidence that sites

were selected with any racially-discriminatory purpose. The

requirement of PCSSD’s desegregation decree was that sites be

chosen on “ objective criteria” and be “racially neutral.” There

was no finding that these criteria were violated. The courts

below interpreted Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg BcL of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971), as requiring that sites be chosen for the

purpose of promoting integration. The Swann opinion does not

support the existence of any such constitutional obligation.

8 The concurring-and-dissenting opinion relies almost exclu

sively on this theory to support the remedy ordered. The

purely speculative nature of this ground is demonstrated by the

(footnote continued on next page)

11

any specific evidence or detailed findings, the mere pos

sibility that such effects may have existed cannot satisfy

M illiken’s requirement that an interdistrict violation is one

that has a “ significant” interdistrict effect and that is a

“ substantial cause” of interdistrict segregation. Given the

well-nigh universal movement of white population to subur

ban areas, there is simply no basis in the findings below for

attributing the population distribution in the Little Rock

metropolitan area to causes other than demographic factors

for which a school district bears no responsibility. Pasadena

City Bd. of Educ. v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424, 435-37 (1976).

3. The court of appeals purported to find “ interdistrict

housing violations” by defendants, as a basis for liability on

the part of both the State and the school-district defendants.

Although the findings and evidence clearly demonstrated

the existence of segregatory location of housing projects

within the City of Little Rock, the sole example of any

housing decision with interdistrict effects identified by the

court or in the evidence was the Granite Mountain housing

project— a violation that could at most support the specific

relief ordered as to that segment of the Little Rock District.

See supra, p. 5, n.3 and p. 8, n.4. The court also adverted to

the fact that neither the Little Rock nor the North Little

Rock housing authorities had ever built housing projects

outside the city limits. But there was no finding, and no

evidence, that the failure to build public housing in the

County was the result of any racially discriminatory purpose

on the part of the housing authorities themselves or of any

person, private or official, in the suburban areas. Absent any

evidence whatever of any racial discrimination affecting the

non-location of housing projects, no interdistrict constitu

tional violation can be predicated on such facts. United States

v. Bd. of School Com m ’rs of City of Indianapolis, 637 F.2d 1101

(7th Cir. 1979); see Milliken, 418 U.S. at 755 (Stewart, J.

(footnote continued from preceding page)

dissenting opinion of Judge Gibson. Dissenting opinion,

Appendix at A-82—A-83.

12

concurring). See also Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropoli

tan Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977).

4. The most crucial ground advanced by the court of

appeals— and the only ground that could support the

coterminous-boundary remedy ordered by the court— was the

finding that “ the boundaries between PCSSD and LRSD had

been maintained to keep LRSD predominantly black and

PCSSD predominantly white” and that boundary “ manipu

lations” have had a substantial interdistrict effect.

Appendix at A-28. It is clear, of course, that if any “district

lines have been deliberately drawn on the basis of race” an

interdistrict remedy correcting that violation would be in

order. Milliken, 418 U.S. at 744-45. The difficulty with such a

grounding in this case is that there is no finding of any act or

action on the part of the defendant school district that could

form the basis for such a gerrymandering violation. Under

Arkansas law, the deannexation of a portion of a school

district occurs on petition of a majority of the qualified

electors in the area to be deannexed. It is undisputed in this

case that there was never any petition for deannexation from

PCSSD to LRSD after 1968. PCSSD never rejected, resisted,

or opposed any such deannexation; the question was never

presented. The absence of any factual support for a finding

of “ freezing” or “manipulation” of school-district boundaries

is detailed in the opinions of Judge Arnold, concurring and

dissenting, and Judge Gibson, dissenting. (Appendix at A-

69— A-70, A-80— A-82.)

The conclusion of the majority of the court of appeals on

this point can only mean that a school district has an affirma

tive duty to bring about a surrender of its territory for the

purpose of improving racial balance in an adjacent district.

To impose such an obligation would completely undermine

the teaching of Milliken that school district boundaries,

created without discriminatory purpose, are to be respected

in the absence of a constitutional violation affecting those

boundaries. The Fourth Circuit has rejected such a theory,

in circumstances more compelling than any present here.

13

Goldsboro City Bd. of Ed. v. Wayne Cty, Bd. of Ed., 745 F.2d 324,

326 (4th Cir. 1984). The decisions of this Court provide no

precedent for imposing such an affirmative duty.

In Milliken v. Bradley the Court characterized the record as

showing that both lower courts had endorsed a metropolitan

remedy “ only because of their conclusions that total desegre

gation of Detroit would not produce the racial balance which

they perceived as desirable.” 418 U.S. at 740-41. The find

ings and opinions of the lower courts in this case leave little

room for doubt that a similar major premise explains the

interdistrict remedy ordered here. The true basis for the

decision is best indicated by the district court’s concluding

observation in its findings and opinion on liability:

It is obvious from the last school election that Little

Rock whites, many of whom are educating their

children in private schools, are unwilling to com

mit financial support to a school system rapidly

becoming all black. The same trends so evident in

Little Rock are now beginning to gather momen

tum in North Little Rock. North Little Rock now

is approximately at the point where Little Rock

was ten years ago in terms of black enrollment.

The collapse of support for public education

would be a tragic event. It is axiomatic that a

democracy cannot long exist without a system of

free public schools providing a quality education.

In my view public education in this community has

reached a crisis stage. The problem cannot be

avoided by equivocation or half measures. I am

today ordering a consolidating of the three school

districts now operating in Pulaski County.

(Appendix at A-133.)

The important ultimate question presented by this case is

whether a federal court may use its powers for such social

objectives, so long as it is able to couch its judgment in a

14

parade of tenuous findings of “ fact” that invoke the talis-

manic phrase “ interdistrict effects.” The reasoning and deci

sion in this ease set a precedent that eviscerates the

principles announced by this Court in Milliken v. Bradley.

CONCLUSION

The writ of certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

PHIL C. NEAL*

208 South LaSalle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60604

(312) 269-8000

ALSTON JENNINGS

2200 Worthen Bank Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 77201

(501) 371-0808

Attorneys for Petitioners

*Counsel of Record

OF COUNSEL:

NEAL, GERBER & EISENBERG

208 South LaSalle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60604

WRIGHT, LINDSEY & JENNINGS

2200 Worthen Bank Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 77201

Dated: February 5, 1986.

APPENDIX

A-l

United §tates (Hourt o! Appeals

For The Eighth Circuit

Little R ock School D istrict,

vs.

Appellee,

P ulaski County Special School D istrict N o.

1; Mac F au lk n e r ; Charles Stratton ; Don

H in dm an ; Mack M cA llister ; Sheryl D u n n ;

David Sa in ; an d M ildred Tatum ,

Appellants.

Lorene J oshua , as n ext friend of minors

Leslie J o sh u a , Stacy J oshua an d M ayn e

J oshua; R e v . R obert W illingham , as n ext

FRIEND OF MINOR TONYA WILLINGHAM; SARA

M a t t h e w s , as n e x t f r ie n d of K h a y y a n

Davis , A lexa A rmstrong and K arlos A rm

strong; M rs. A lvin H udson as n ext friend

of Ta t ia H udson ; M rs . H ilton Taylo r as

NEXT FRIEND OF PARSHA TAYLOR, HlLTON

Ta y lo r , J r . an d Brian Ta y lo r ; R ev . John M.

M iles as n ext friend of Janice M iles D er

rick M iles ; R e v . R obert W illin g h am on

BEHALF OF AND AS PRESIDENT OF THE LITTLE

R ock Branch of NAACIP; Lorene Joshua on

BEHALF OF AND AS PRESIDENT OF THE NORTH

L ittle R ock Branch of the NAACIP; K athe

rine K night , in d ivid u ally an d as P resident

of the L ittle Rock Classroom Teachers A s

sociation (LRCTA); LRCTA; Ed Bullington ,

in d ivid u ally an d as President of the P ulas

k i A s so c ia t io n of Cla ssr o o m T e a c h e r s

(PACT); PACT; J ohn H arrison , in d ivid u ally

an d as President of the N orth L ittle R ock

Classroom Teachers A ssociation (N LRCTA);

NLRCTA; M ilton J ackson , in d ivid u ally an d

AS A NONCERTIFIED EDUCATIONAL SUPPORT EM

PLOYEE of the L ittle R ock School D istrict,

Appellees. .

Appeals from the

United States Dis

trict Court for the

Eastern District of

Arkansas.

No. 85-1078

A-2

United §tates (Eourt of Appeals

For The Eighth Circuit

L ittle R ock School D istrict,

Appellee,

vs.

N orth Little R ock School D istrict; M urry

W itcher; Gin n y Jones; V icki Stephens; Leon

B a r n e s ; M a r ia n n e Go s s n e r ; a n d Ste v e

Morley ,

Appellants.

Lorene J oshua, as n ext friend of minors

Leslie J o sh u a , Stacy J oshua an d M ayn e

J oshua; R ev . R obert W illingham , as next

FRIEND OF MINOR TONYA WILLINGHAM; SARA

M a t t h e w s , as n e x t f r ie n d of K h a y y a n

D avis , A le x a A rmstrong an d K arlos A rm

strong; M rs. A lvin H udson as n ext friend

of Tatia H udson ; M rs. H ilton Taylor as

NEXT FRIEND OF PARSHA TAYLOR, HlLTON

Ta y lo r , J r . an d Brian Taylo r ; R ev . J ohn M.

M iles as n ext friend of Janice M iles D er

rick M iles ; R e v . R obert W illin g h a m on

BEHALF OF AND AS PRESIDENT OF THE LITTLE

R ock Branch of NAACIP; Lorene J oshua on

BEHALF OF AND AS PRESIDENT OF THE NORTH

L ittle R ock Branch of the NAACIP; K athe

rine K night , in d ivid u ally an d as President

of the L ittle Rock Classroom T eachers A s

sociation (LRCTA); LRCTA; Ed Bullington ,

INDIVIDUALLY AND AS PRESIDENT OF THE PULAS

KI A s so c ia t io n of Cla ssr o o m T e a c h e r s

(PACT); PACT; J ohn H arrison , in d ivid u ally

an d as President of the N orth Little R ock

Classroom Teachers A ssociation (NLRCTA);

NLRCTA; M ilton J ackson , in d ivid u ally and

AS A NONCERTIFIED EDUCATIONAL SUPPORT EM

PLOYEE of the L ittle R ock School D istrict,

Appellees. _

Appeals from the

United States Dis

trict Court for the

Eastern District of

Arkansas.

No. 85-1079

A-3

United §tates (Etiurt ol Appeals

For The Eighth Circuit

L ittle R ock School D istrict,

Appellee,

A rkan sas State Board of Education ; W ayn e

H a RTSFIELD; WALTER TURNBOW; HARRY A.

H aines ; J im D upree ; D r . Harr y P. McDonald ;

R obert L. N ew ton ; A lice L. P reston; J eff

Starlin g ; Earle Lo ve ,

Appellants.

Lorene J oshua, as n ext friend of minors

Leslie J o sh u a , Stacy J oshua an d M ayn e

J oshua; R ev . R obert W illingham , as n ext

FRIEND OF MINOR TONYA WILLINGHAM; SARA

M a t t h e w s , as n e x t f r ie n d of K h a y y a n

Davis , A le x a A rmstrong and K arlos A rm

strong; M rs. A lvin H udson as n ext friend

of Ta t ia H udson ; M rs. H ilton Taylor as

NEXT FRIEND OF PARSHA TAYLOR, HlLTON

Ta y lo r , J r . an d Brian Taylo r ; R ev . J ohn M. •

M iles as n ext friend of J anice M iles D er

rick M iles ; R e v . R obert W illin g h am on

BEHALF OF AND AS PRESIDENT OF THE LITTLE

R ock B ranch of NAACIP; Lorene J oshua on

BEHALF OF AND AS PRESIDENT OF THE NORTH

L ittle R ock Branch of the NAACIP; K athe

rine K night , in d ivid u ally an d as P resident

of the L ittle R ock Classroom Teachers A s

sociation (LRCTA); LRCTA; Ed Bullington ,

INDIVIDUALLY AND AS PRESIDENT OF THE PULAS

KI A sso c ia t io n of Cla ssr o o m T e a c h e r s

(PACT); PACT; J ohn H arrison , in d ivid u ally

an d as President of the N orth L ittle R ock

Classroom Teachers A ssociation (NLRCTA);

NLRCTA; M ilton J ackson , in d ivid u ally and

AS A NONCERTIFIED EDUCATIONAL SUPPORT EM

PLOYEE of the L ittle R ock School D istrict,

Appellees. -

Appeals from the

United States Dis

trict Court for the

Eastern District of

Arkansas.

No. 85-1081

A-4

Submitted: April 29, 1985

Filed: November 7, 1985

Before LAY, Chief Judge, and HEANEY, BRIGHT, ROSS,

McMILLIAN, ARNOLD, JOHN R. GIBSON, FAGG,

and BOWMAN, Circuit Judges, En Banc.

HEANEY, Circuit Judge.

The United States District Court for the Eastern District

of Arkansas, after trial, found that the defendants Pulaski

County Special School District (PCSSD), the North Little

Rock School District (NLRSD) and the Board of Education

of the State of Arkansas (State Board) contributed to the

continuing segregation of the Little Rock schools, and that

an interdistrict remedy was appropriate. The district court

ordered consolidation of the three school districts, establish

ment of a uniform millage rate, elimination of dis

criminatory practices, and creation of magnet schools to

enhance educational opportunities in the new district. It

held that the State Board had remedial, financial and over

sight responsibilities that would be detailed at a later date.

The defendants appeal from the district court’s order. In

addition, the Joshua intervenors, representing black parents

and students, filed a brief in support of the district court’s

judgment, and the United States filed an amicus curiae brief

in general support of the appellants.

We hold that the district court’s findings on liability are

not clearly erroneous and that intra- and interdistrict relief

is appropriate. We find, however, that the violations can be

remedied by less intrusive measures than consolidation.

These measures, most of which were suggested by the

defendant school districts or the Joshua intervenors, include

authorizing the district court to make limited adjustments,

after a hearing, to the boundaries between Little Rock School

A-5

District (LRSD) and PCSSD, correcting the segregative prac

tices within each of the individual school districts, improv

ing the quality of any remaining nonintegrated schools in

LRSD, providing compensatory and remedial programs for

black children in all three school districts, authorizing the

district court to establish, after a hearing, a limited number

of magnet schools and programs open to all students in

Pulaski County, and requiring the State Board to participate

in funding the compensatory, remedial and quality educa

tion programs, in establishing and maintaining the magnet

schools, and in monitoring plan progress. We remand to the

district court for action consistent with this opinion.

I. BACKGROUND AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY.

Pulaski County is the most heavily populated metropoli

tan area in Arkansas, encompassing three independent

school districts: LRSD, NLRSD, and PCSSD. The LRSD

covers fifty-three square miles and comprises about sixty

percent of the City of Little Rock. Although the population

of the City of Little Rock is approximately two-thirds white,

in the 1983-84 school year, 70% of LRSD’s 19,052 students

were black. Along with NLRSD, LRSD is one of the oldest

continuously operating school districts in Arkansas. The

NLRSD covers twenty-six square miles and comprises

nearly all of the City of North Little Rock. Its 1983-84

student population was 9,051 (36% black, 64% white). The

PCSSD surrounds LRSD and NLRSD. Created in 1927

through the consolidation of thirty-eight rural independent

school districts, it covers 755 square miles and contains the

remainder of the county not included in the other two school

districts. In 1983-84, it had 27,839 students (22% black, 78%

white). Each of the three districts currently operates under a

court-ordered desegregation decree, and none of the districts

has achieved unitary status.

On November 30, 1982, LRSD filed this action against

PCSSD, NLRSD, the State of Arkansas, and the State

A-6

Board.1 On April 13, 1983, the district court dismissed the

claim against the State of Arkansas but refused to take

similar action concerning the State Board, holding that the

Board is a proper party in light of its general supervisory

relationship with the individual school districts, and the

allegations that it has carried out its duties in a manner

which increased segregation in Little Rock. The district

court concluded that the dismissal of the State of Arkansas

had no practical effect on the disposition of the lawsuit.

Little Rock School District v. Pulaski County Special School

District, 560 F. Supp. 876, 878 (E.D. Ark. 1983). The district

court separated the liability and remedy phases of the litiga

tion and held liability hearings from January 3-13, 1984.

On April 13, 1984, the district court issued its decision on

liability, finding that PCSSD and NLRSD had failed to

establish unitary, integrated school districts and had com

mitted unconstitutional and racially discriminatory acts

which resulted in “significant and substantial interdistriet

segregation.” Little Rock School District v. Pulaski County

Special School District, 584 F. Supp. 328, 351-53 (E.D. Ark.

1984). It concluded that these two school districts had taken

actions which had substantial interdistriet segregative

effects on education in each of the school districts in the

county, and that the districts had failed to redress these

segregative effects which they had perpetuated for over a

century. The district court also reiterated its holding that

the State Board was a “necessary party who must be made

subject to the Court’s remedial order.” 584 F. Supp. at 352-53.

It concluded that the only long- or short-term solution to 1

1LRSD also named as defendants the Pulaski County Board

of Education and the individuals serving on each of the

defendant boards of education. The Pulaski County Board of

Education did not participate in this litigation. The district

court states, however, that the County Board has a remedial

responsibility that has yet to be defined.

On September 29, 1983, the district court denied Little Rock’s

motion to add the Governor, State Treasurer and State Auditor

as defendants.

A-7

these interdistrict violations is consolidation, and it

scheduled hearings to consider the precise means to accom

plish that end.

The first remedial hearings took place from April 30

through May 5, 1984. Before these hearings were held, a

group of black parents in Little Rock, the Joshua interven-

ors, sought unsuccessfully to intervene in the proceedings.2

They appealed, and on May 23, 1984, this Court ordered the

district court to allow them to intervene and directed it to

hear evidence from them concerning remedial alternatives to

consolidation. Meanwhile, the defendant school districts had

also appealed from the district court’s order finding interdis

trict violations and ordering consolidation of the three school

districts. On May 23, 1984, we dismissed that appeal as

premature but suggested that the district court reopen the

proceedings to permit PCSSD and NLRSD to advance

remedial alternatives to consolidation. Little Rock School D is

trict v. Joshua, No. 84-1543 (8th Cir. May 23, 1984) (order);

Little Rock School District v. Pulaski County Special School

District, Nos. 84-1620, 84-1621 (8th Cir. May 23, 1984) (order).

The district court held further remedial hearings from

July 30 through August 2, 1984, and heard evidence on

alternative remedial plans submitted by PCSSD, NLRSD,

and the Joshua intervenors.3 On November 19, 1984, it

issued its decision on the remedy, reaffirming its view that

consolidation of the three school districts was necessary to

remedy the constitutional violations. It also entered further

findings concerning the State Board’s liability and reaffirmed

2The district court had denied an earlier motion by Joshua to

intervene on January 3, 1984.

3 The district court also heard from the McKnight interven

ors, representing the teachers employed in the three districts.

Little Rock School District v. Pulaski County Special School District,

597 F. Supp. 1220, 1227 (E.D. Ark. 1984); see also Little Rock

School District v. Pulaski County Special School District, 738 F.2d

82, 85 (8th Cir. 1984) (allowing intervention by teacher

representatives).

A-8

the State Board’s remedial responsibilities. 597 F. Supp. at

1227-28. The district court subsequently denied motions by

the defendants for reconsideration.

This appeal followed. The issues on appeal are: (1)

whether the district court’s findings of interdistrict viola

tions are clearly erroneous; (2) whether the district court’s

remedy exceeds the scope of the constitutional violations;

and (3) whether the proceedings before the district court

deprived the State Board and PCSSD of due process.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT’S FINDINGS OF INTERDIS

TRICT VIOLATIONS ARE NOT CLEARLY ERRONEOUS.

A. Legal Background.

1. Legal Standards in Desegregation Cases.

Thirty years ago, the Supreme Court decided in Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) that “ in the field of

public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no

place. Separate educational facilities are inherently un

equal.” Id. at 495. Since Brown, the Supreme Court has

affirmed the obligation of school authorities operating segre

gated schools “ to take whatever steps might be necessary to

convert to a unitary system in which racial discrimination

would be eliminated root and branch.” Raney v. Board of

Education, 391 U.S. 443, 446 (1968); Green v. County School

Board, 391 U.S. 430, 437-38 (1968). Moreover, the Supreme

Court has held that “ [ejaeh instance of a failure or refusal to

fulfill this affirmative duty continues the violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment.” Columbus Board of Education v.

Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 459 (1979); Dayton Board of Education v.

Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406, 413-14 (1977) (Dayton II).

Before a court may impose an interdistrict desegregation

remedy, it must find an interdistrict constitutional violation.

In Milliken I, the Supreme Court explained this prerequisite:

Before the boundaries of separate and autonomous

school districts may be set aside by consolidating

the separate units for remedial purposes or by

A-9

imposing a cross-district remedy, it must be shown

that there has been a constitutional violation

within one district that produces a significant

segregative effect in another district. Specifically,

it must be shown that racially discriminatory acts

of the state or local school districts, or of a single

school district have been a substantial cause of

interdistrict segregation.

Milliken I, 418 U.S. at 744-45 (emphasis added).

As with any fourteenth amendment violation, a dis

criminatory purpose must be shown. Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. 229 (1976); Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corporation, 429 U.S. 252 (1977); Keyes v. School

District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973). Although the dis

criminatory impact of state action does not in itself prove a

constitutional violation, the “ [ajdherence to a particular

policy or practice, ‘with full knowledge of the predictable

effects of such adherence upon racial imbalance in a school

system is one factor among many others which may be

considered by a court in determining whether an inference of

segregative intent should be drawn.’ ” Columbus Board of

Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 465 (1979).

Although an evaluation of basic segregative effects is

important in determining the scope of a violation and hence

the permissible scope of the remedy, a reviewing court is not

called upon to quantify the precise segregative effects of each

individual act of discrimination. Dayton Board of Education

v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 527, 540 (1979) (Dayton II).

This Court has affirmed findings of interdistrict violations

and has approved interdistrict desegregation remedies on

several occasions. See, e.g., Morrilton School District No. 32 v.

United States, 606 F.2d 222, 229 (8th Cir. 1979); United States v.

State of Missouri, 515 F.2d 1365, 1371 (8th Cir. 1975); H aney v.

County Board of Education of Sevier County, 429 F.2d 364 (8th Cir.

1970). We have also required a state (that had been found to

have committed intradistrict violations) to participate in an

A-10

intradistrict remedy even though that remedy required the

state to expend funds in school districts other than the violat

ing district. Liddell v. State of Missouri, 731 F.2d 1294 (8th Cir.),

cert, denied,___U.S_____, 105 S. Ct. 82 (1984).

2. Review of Factual Findings.

We will not reverse the district court’s factual findings

with respect to liability unless we conclude that they are

clearly erroneous. Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a); Anderson v. City of

Bessemer City, 105 S. Ct. 1504 (1985); Pullman-Standard v.

Swint, 456 U.S. 273, 287-90 (1982); Dayton II , 443 U.S. at 534

n.8; Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. at 468-71

(concurring opinions of Burger, C.J., and Stewart, J.); United

States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. 364, 395 (1978).

Nor will we reverse such findings when they are based on

inferences from other facts unless the rigorous standards of

the same rule are met. Anderson, 105 S. Ct. at 1511. The

Supreme Court has emphasized the importance of the clearly

erroneous rule in civil rights cases, see, e.g., Pullman-Standard

v. Swint, 456 U.S. at 287-90, and, more particularly, in school

desegregation cases:

The elimination of the more conspicuous forms of

governmentally ordained racial segregation . . .

counsels undiminished deference to the factual

adjudications of the federal trial judges in cases

such as these, uniquely situated as those judges are

to appraise the societal forces at work in the com

munities where they sit.

Columbus, 443 U.S. at 470 (Justice Stewart, with whom Chief

Justice Burger joins, concurring).

B. The State’s Role in the Segregation of the Three

Pulaski County School Districts.

The district court detailed the history of state-imposed

segregation in the public schools in the State of Arkansas

A-ll

and the steps taken by the state4 to perpetuate a dual school

system, particularly in LRSD. The court pointed out that,

4 In finding that the State Board of Education was the proper

agency through which the state was responsible in creating and

failing to disestablish the dual school systems in Pulaski

County, the district court noted:

The State Board of Education has, by statute, general

supervision over all public schools in the State of Arkan

sas. Ark. Stat. Ann. § 80-113. In addition to that general

responsibility, the State Board and the Department of

Education have numerous specific duties, including the

approval of plans and expenditures of public school funds

for new school buildings (Ark. Stat. Ann. §§ 80-113,

80-3506; T. 775); review, approval and disapproval of local

school district budgets (Ark. Stat. Ann. §§ 80-113, 80-1305;

T. 773); administration of all federal funds for education

(Ark. Stat. Ann. §§ 80-123, 80-140); disbursement of State

Transportation Aid Funds to local school districts (Ark.

Stat. Ann. §§ 80-735, 80-736); assisting school districts in the

operation of their transportation system (T. 774); lending funds

from the State Revolving Loan Fund to local school districts

(Ark. Stat. Ann. § 80-942); approval or disapproval of bonds

issued by local school districts (Ark. Stat. Ann. §80-1105;

T. 775); advising school districts regarding the issuance of bonds

(T. 777); and regulation of the operation of school buses (Ark.

Stat. Ann. §§80-1809, 80-1809.2).

The State Board of Education has broad statutory

authority to supervise the public schools of the state gener

ally, and to take what action it may deem necessary to

“promote the physical welfare of school children and

promote the organization and increase the efficiency of the

public schools of the State.” Ark. Stat. Ann. § 80-113.

The State Board of Education has the authority to

promulgate regulations concerning the earmarking and use

of funds used by local school districts (Ark. Stat. Ann.

§ 80-1305), the use of federal education funds by local

school districts (Ark. Stat. Ann. § 80-142) for the adminis

tration of State Transportation Aid Funds by local school

districts (Ark. Stat. Ann. § 80-735), and for the operation of

(footnote continued on next page)

A-12

despite the state’s role in mandating and maintaining the

dual system until the mid-1960’s, the state had done nothing

to assist in dismantling the dual system. The court further

found that the state’s acts had an interdistrict segregative

effect with respect to the three school districts in Pulaski

County. These findings are not clearly erroneous.

The state’s role in the segregation of the public schools of

Arkansas began in 1867 when the legislature enacted a law

requiring separate public schools for blacks. Act of Feb. 6,

1867, No. 35, § 5, 1866-1867 Ark. Acts 98, 100. In 1931, this

legislation was superseded by a law which required the

board of school directors in each district of the state to

“ establish separate schools for white and colored persons.”

(footnote continued from preceding page)

school buses by local districts (Ark. Stat. Ann. §§ 80-1809,

80-1810).

The State Board of Education may lend funds from the

State Revolving Loan Fund for the purchase of school

buses and other equipment, for making major repairs and

constructing additions to school buildings, for the purchase

of sites for new school buildings, for the construction of

new school buildings, and for the purchase of surplus

buildings. Ark. Stat. Ann. § 80-942.

597 F. Supp. at 1227-28 (emphasis included).

The State Board does not contest these findings. Rather, it

argues: first, that the district court’s decision imposes financial

burdens on the Board without finding that such expenditures

are required to redress the effects of the Board’s constitutional

violations; second, that the Board was denied procedural due

process by the district court; third, that the district court’s

findings failed to establish any causal relationship between

violations found and the conditions to be remedied; and fourth,

the district court’s remedial order exceeds the limits necessary

to correct the effects of the violations. In any event, we find no

error in the district court’s imposition of remedial responsibili

ties on the state through the State Board. See Evans v.

Buchanan, 393 F. Supp. 428 (D.C. Del.) (three-judge panel), aff’d,

423 U.S 963 (1975).

A-13

Ark. Stat. Ann. § 80-509(e) (Repl. 1980). This statute was

repealed on November 1, 1983.

Even though the United States Constitution required that

the black and white public schools be equal, Cumming v. Rich

mond County Board of Education, 175 U.S. 528 (1899); see also

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), black public schools in

Arkansas were inferior to white schools. What was true

throughout the state was true for NLRSD and PCSSD.

Expenditures per pupil for black children in elementary

schools in these districts were substantially less than they were

for white children, the salaries of black teachers in the black

schools were substantially lower than they were for the white

teachers in the white schools, and the illiteracy rate of black

children was substantially higher than that of white children.

Of particular importance in this case, the black elementary

schools in these two districts were inferior to the black ele

mentary schools in LRSD. 584 F. Supp. at 330.

The disparities at the high school level were even more

pronounced than at the elementary level. Historically, LRSD

maintained a high school for black students that was fully

accredited by the North Central Association. Id. As late as the

mid-1950’s, however, no similar facility was maintained by

PCSSD. Id. PCSSD paid the tuition and transportation costs

for numerous black students who traveled from PCSSD to

attend school in LRSD. 584 F. Supp. at 330. The district court

credited several studies and the testimony of several witnesses

to the effect that LRSD was identified as the school district in

the state which provided educational opportunities for black

students. Id. This identification tended to draw black students

to LRSD from all over the state, and particularly from Pulaski

County.5 The state was fully aware of these disparities.

Indeed, it had commissioned studies documenting that the

disparities existed, and that the disparities were prominent

5 Other factors encouraging migration of blacks to LRSD were

jobs and public housing. 584 F. Supp. at 345. As pointed out

elsewhere in this opinion, no public housing has been constructed

in PCSSD, and housing and credit restrictions prevented blacks

from buying or renting housing in much of that district.

A-14

among the factors that drew black families to Little Rock from

the county and the rest of the state.

It cannot be seriously denied that the Little Rock

School District’s maintenance of the only North

Central accredited black high school in the County

and indeed in the entire area led to a concentration

of blacks in this district. For almost half a century

it has not only assumed the burden of giving a

quality education to blacks in the County and from

far corners of the State but has also been the object

of racially motivated attacks by certain political

and cultural groups.

584 F. Supp. 330.6

6LRSD introduced into evidence a study which made the

following conclusion:

In sum, black students from Pulaski County crossed the

district boundary to attend senior high in Little Rock from

the 1920s to the 1960s. They probably became numerous in

the early 1930s when Paul Laurance Dunbar High School

acted as a magnet for county students who had little

opportunity to attend senior high in their own district. At

some point, the two districts worked out a tuition agree

ment under which Pulaski County paid for the use of

Little Rock facilities by individual students. This led to a

“ county” designation on student record cards, the

incidence of which shows that a substantial number of

county students were enrolled in at Dunbar in the 1940s

and 1950s. Students from the county continued to attend

Little Rock into the 1960s, but their numbers decreased as

the county began to provide more and better senior high

schools.

J.D.R. at 915-21.

This movement of blacks into LRSD, which the district court

found to be “consistently understated” as shown in PX 36, 584

F. Supp at 346, is reflected in general population statistics.

From 1950 to 1980, the black population of the City of Little

Rock more than doubled, from approximately 23,000 to more

than 51,000. During the same period, the white population of

the City of Little Rock, excluding annexed territory, declined.

(footnote continued on next page)

A-15

In 1953, when the Granite Mountain housing project for

blacks was being planned, the state, at the behest of the

affected school districts enacted legislation authorizing the

transfer of the project site from PCSSD to LRSD. This

action insured that a major black housing project would be

built in LRSD, and that LRSD would continue to be recog

nized as the school district in Pulaski County which edu

cated black children. This housing project is discussed more

fully infra.

Notwithstanding the state’s awareness of the educational

disparities between LRSD and the other school districts in

the state, it took no remedial action to require adequate

educational opportunities for blacks in school districts other

than LRSD.7 In summarizing the pre-Brown history of

school segregation in Pulaski County, the district court

found that, historically, “ [a]s far as the education of blacks

was concerned, school district boundaries in Pulaski County

were ignored.” 584 F. Supp. at 330.

Even after the Supreme Court’s decisions in Brown I and

Brown II, the State of Arkansas took no steps to dismantle

the segregated school system in Arkansas or to improve the

quality of the black schools in the state generally or in the

defendant school districts in particular. To the contrary, it

(footnote continued from preceding page)

If the annexed territory is included, the white population

increased from 79,000 to 105,000. See BUREAU OF THE CEN

SUS, 1950 CENSUS OF POPULATION, CHARACTERIS

TICS OF THE POPULATION, vol. 11, part 4; BUREAU OF

THE CENSUS, 1980 CENSUS OF POPULATION, CHARAC

TERISTICS OF THE POPULATION, vol. 1. For related

population statistics, see note 8 infra.

’ Indeed, the State Board successfully argued in a federal

district court case in 1949 that black students did not have the

right to attend high school within their school districts and

that “ the interests of Negro education will be best promoted by

the maintenance of a consolidated Negro high school serving

several districts[.]” Pitts v. Board of Trustees of DeWitt Special

School District, 84 F. Supp. 975, 987 (E.D. Ark. 1949).

A-16

took a series of actions which delayed the elimination of the

dual school system in the state for years. These actions were

primarily directed against LRSD and heightened the iden

tity of that district as the “black” district of Pulaski County.

On May 20, 1954, three days after Brown I, the Board of

Education announced that “ [i]t is our responsibility to com

ply with federal constitutional requirements and we intend

to do so when the Supreme Court of the United States

outlines the method to be followed.” Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U.S. at 8. By the spring of 1955, the Little Rock Board of

Education had adopted a plan which would have desegre

gated the schools by 1963. Id. A large majority of the

citizens of Little Rock agreed that the plan was “ the best for

the interests of all pupils in the District.” Id. The plan was

approved by the federal district court, Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F.

Supp. 855 (E.D. Ark. 1956), and this Court, Aaron v. Cooper,

243 F.2d 361 (8th Cir. 1957), and review was not sought in

the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, the state intervened to prevent desegregation

of the Little Rock schools. In November, 1956, Arkansas’s

voters adopted three initiatives sponsored by the state’s polit

ical leadership. These included:

1. An amendment to the state constitution

directing the legislature to oppose Brown in every

constitutional manner until such time as the

federal government ceases from enforcing Brown,

and providing that any employee of the state, or

any of its subdivisions, who willfully refuses to

carry out the mandates of this amendment shall

automatically forfeit his office and be subject to

prosecution under penal laws to be enacted by the

legislature. Ark. Const. Amend. 44. Although this

amendment remains on the books, it is recognized

by the state authorities as being unconstitutional.

2. A resolution of interposition calling on all

states and citizens to adopt a constitutional amend

ment prohibiting federal involvement in public

A-17

education, and pledging resistance to school

desegregation.

3. A pupil placement law, Ark. Stat. §§ 80-1519 to

-1524, authorizing local boards of education or

superintendents to transfer or reassign students or

teachers among any schools within their districts,

or to “ adjoining districts whether in the same or

different counties, and for transfer for school funds

or other payments by one Board to another for or

on account of such attendance.” Dove v. Parham, 176

F. Supp. 242, 244 n.4 (E.D. Ark. 1959).

See 584 F. Supp. at 330-32.

In January, 1957, the state legislature enacted, and the

Governor signed, legislation implementing the constitutional

amendment, including legislation authorizing local school

districts to spend school funds to defend integration litiga

tion, and to relieve (or at least to delay) school children from

compulsory attendance at racially mixed schools. Governor

Orval Faubus also signed legislation creating a state sover

eignty commission, with broad powers, to:

1. Perform any and all acts and things deemed

necessary and proper to protect the sovereignty of

the State of Arkansas, and her sister states from

encroachment thereon by the Federal Government

or any branch, department or agency thereof, and

to resist the usurpation of the rights and powers

reserved to this State or our sister states by the

Federal Government.

2. Give such device and provide such legal

assistance as the Commission considers necessary or

expedient, when requested in writing to do so by

resolution adopted by the governing authority of

any school district, upon matters, whether involv

ing civil or criminal litigation or otherwise, relat

ing to the commingling of races in the public

schools of the State.

A-18

3. Study and collect information concerning

economic, social and legal development constituting

deliberate, palpable and dangerous invasions of or

encroachments upon the rights and powers of the

State reserved to the State under [the Tenth

Amendment to the U.S. Constitution],

See 584 F. Supp. at 330-32.

The statute also required prointegration organizations to

register and report to the state sovereignty commission. See

Aaron v. Cooper, 163 F. Supp. 13, 15 (E.D. Ark. 1958).

Notwithstanding these actions, the Little Rock Board of

Education took preliminary steps to admit nine black stu

dents to Central High School in the fall of 1957. Governor

Faubus, however, barred the nine students from entering

Central High School by ordering the Arkansas National

Guard to stand at the schoolhouse door and to declare the

school “ off limits” to black students. President Eisenhower

responded by dispatching federal troops to guarantee the

admittance of the nine black students. They were admitted

after the troops arrived and the troops remained in Little

Rock for the rest of the school year. Subsequently, the

federal district court enjoined Governor Faubus from using

the Arkansas National Guard to obstruct or interfere with

court orders, Aaron v. Cooper, 156 F. Supp. 220, 226-27 (E.D.

Ark. 1957), and this Court affirmed, Faubus v. United States,

254 F.2d 797, 806-08 (8th Cir. 1958).

In February, 1958, “because of extreme public hostility .. .

engendered largely by the official attitudes and actions of the

Governor and the Legislature,” Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. at 12,

local officials petitioned the district court to postpone until at

least 1961 “ the plan of gradual racial integration in the Little

Rock public schools” which the Little Rock Board of Education

had adopted in 1955 for implementation at the high school

level for the 1957-58 school year. Aaron v. Cooper, 163 F. Supp.

13,14 (E.D. Ark. 1958). The district court found that “ between

the spring and fall of 1957 there was a marked change in public

A-19

attitude toward [the school desegregation] plan,” that persons

who had formerly been willing to accept it had changed their

minds and had come to the conclusion “ that the local School

Board had not done all it could do to prevent integration.” 163

F. Supp. at 21. The court noted that the state legislature’s 1957-

58 “ enactments had their effect at Little Rock and throughout

the State in stiffening opposition to the plan[.” ] Id. Because of

this state-fostered “ opposition . . . to the principle of integra

tion which .. . runs counter to the pattern of southern life

which has existed for over three hundred years,” id., and the

“ corresponding damage to the educational program,” id. at 26,

and the City of Little Rock itself, the court held that a two-and-

one-half-year moratorium on desegregation was necessary.

This Court reversed, Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F.2d 33, 40 (8th

Cir. 1958), and the Supreme Court affirmed our decision on

September 12, 1958, quoting with approval a pleading filed

by the school board:

The legislative, executive, and judicial departments

of the state government opposed the desegregation

of Little Rock schools by enacting laws, calling out

troops, making statements vilifying federal law

and federal courts, and failing to utilize state law

enforcement agencies and judicial processes to

maintain public peace.

Aaron v. Cooper, 358 U.S. 1, 15 (1958).

While the above appeal was pending, opponents of deseg

regation secured a state court injunction to prevent the open

ing of the “partially integrated high schools” of Little Rock.

Once again, the federal district court set aside the injunction

and this Court affirmed. See Thomason v. Cooper, 254 F.2d 808

(8th Cir. 1958).

In August, 1958, Governor Faubus called an “ emergency

session” of the legislature, which enacted three laws aimed at

preventing the Little Rock Board of Education from comply

ing with Brown. Act 4 authorized the Governor, by proclama

tion, to close any or all public schools within any school district

A-20

pending a referendum “ for” or “against” the “ racial integra

tion of all schools within the school district;” Act 6 permitted

students to transfer to segregated public or private schools

across district lines if the schools they ordinarily attended

were to be desegregated; and Act 9 authorized the removal by

recall of any members of local school district boards. (This Act

was aimed at removing from the Little Rock Board of Educa

tion those who favored desegregation.)

On September 13, 1958, Governor Faubus issued a procla

mation closing the four Little Rock high schools, white and

black. They remained closed throughout the 1958-59 school

year, with the school board leasing the schools to a private

school corporation which intended to operate them on a

segregated basis. The federal courts found that such opera

tion would be unconstitutional and enjoined the private

corporation from operating the schools, see Aaron v. McKinley,

173 F. Supp. 944, 952 (E.D. Ark. 1959), aff’d sub nom. Faubus

v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197 (1959) (per curiam). Nevertheless, the

Little Rock schools remained closed for the entire school

year, and during this period, many white and some black

students from Little Rock attended segregated schools in

PCSSD. The Arkansas state legislature enacted a statute

authorizing the state to pay for the interdistrict transfer of

students from desegregated to segregated public and private

schools. Ark. Acts 1959 No. 236. See Ark. Acts, Special

Session 1958, No. 6. In 1960, an independent study described

the number of transfers among the three Pulaski County

school districts to preserve segregation as “ excessively high.”

584 F. Supp. at 339. Significant numbers of interdistrict

transfers continued until 1965. PX 10.

Shortly after the school closing act was declared unconsti

tutional, the Little Rock Board of Education announced that

it would reopen the Little Rock high schools for the 1959-60

school year because “we will not abandon free public educa

tion in order to avoid desegregation.” Norwood v. Tucker, 287

F.2d 798, 805 (8th Cir. 1961). The Board also publicly