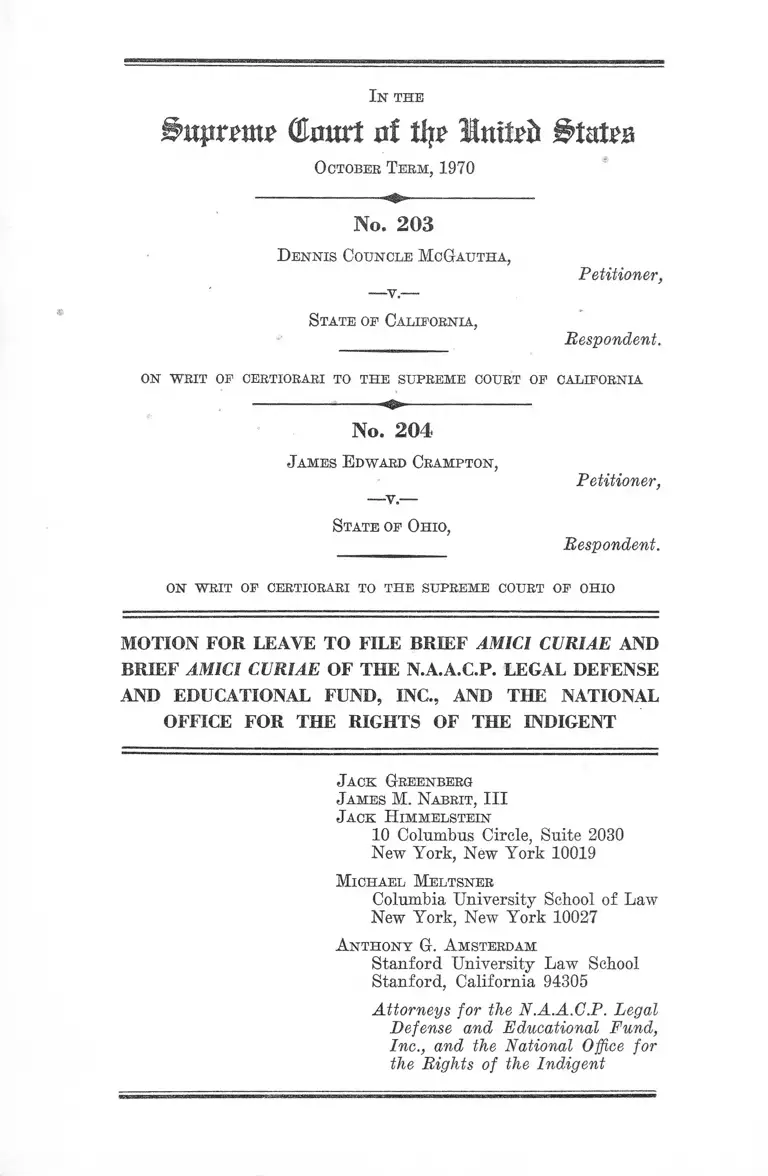

Crampton v State of Ohio Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Crampton v State of Ohio Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae, 1970. 1cdb9c8a-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a26a881a-0770-4c40-b150-bba214b63e2a/crampton-v-state-of-ohio-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

9

Supreme ©xutrt ni % IniUb

October Term, 1970

No. 203

Dennis Councle McGautha,

Petitioner,

State oe California,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OP CALIFORNIA

No. 204

James Edward Crampton,

—v,—

State of Ohio,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

on writ of certiorari to the supreme court of OHIO

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE AND

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AND THE NATIONAL

OFFICE FOR THE RIGHTS OF THE INDIGENT

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Jack H immelstein

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Michael Meltsner

Columbia University School of Law

New York, New York 10027

A nthony G. A msterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., and the National Office for

the Rights of the Indigent

I N D E X

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and State

ment of Interest of the A m ici...................................... 1-M

Brief Amici Curiae ............................................................ 1

Summary of Argument .................................................. 2

Argument .......................................................................... 3

I. Introduction ................... -....................................... 3

II. The Issue of Standardless and Arbitrary Capi

tal Sentencing P ow er............................................ 18

A. The Nature of the Powrnr ............................. 18

1. Ohio ................................................ 18

2. California .................................................... 30

3. Other Jurisdictions .................................. 49

B. The Power Is Unconstitutional ................... 64

III. The Issue of the Single-Verdict Capital Trial 72

IV. The Question of Retroactivity ............... ........... 74

A. The “ Standards” Issue ................................... 74

B. The Single-Verdict Trial Issue ................... 78

Conclusion ............................................................................. 82

A ppendix A —

Brief for Petitioner, William L. Maxwell v. 0. E.

Bishop, O.T. 1968, No. 622 ..................................... la

A ppendix B—

Available Information Relating to the Proportion

of Persons Actually Sentenced to Death, Among

Those Convicted of Capital Crimes ..................... 24a

A ppendix C—

Manner of Submission of the Death-Penalty Issue

at Petitioner Maxwell’s Trial ............................... 35a

PAGE

11

T able op A uthorities

page

Cases:

Adderly v. Wainwright, U.S.D.C., M.D. Fla., No. 67-

298-C iv -J .......... ................. ................ ............... ............... 3-M

Akins v. State, 148 Tex. Crim. App. 523, 182 S.W.2d

723 (1944) ............................ ...... .............. ......... ....... 64

Alford v. State, 223 Ark. 330, 266 S.W.2d 804 (1954) .... 55

Andres v. United States, 333 U.S. 740 (1948) ............... 50

Ashbrook v. State, 49 Ohio App. 298, 197 N.E. 214

(1935) .......................................................................21,72,74

Bagley v. State,------ A rk .------- , 444 S.W.2d 567 (1969) 61

Baker v. State, 137 Fla. 27, 188 So. 634 (1939) ....... . 64

Bankhead v. State, 124 Ala. 14, 26 So. 979 (1899) ____ 51

Barfield v. State, 179 Ga. 293, 175 S.E. 582 (1934) ____ 55

Batts v. State, 189 Tenn. 30, 222 S.W.2d 190 (1946) .... 64

Baugus v. State, 141 So.2d 264 (Fla. 1962) ..55, 57, 61, 63, 68

Beard v. State, 64 Ohio Law Abs. 532, 112 N.E.2d 832

(1951) .............. ......................... ...................... 19

Boggs v. State, 268 Ala. 358, 106 S.2d 263 (1958) ......... 55

Bouie v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 347 (1964) ........... 71

Boykin v. Alabama, 395 U.S. 238 (1969) (O.T. 1968,

No. 642) ......................................................... .. ........... 3-M, 49

Brown v. State, 109 Ala. 70, 20 So. 103 (1896) ... ....... 58, 62

Brown v. State, 190 Ga. 169, 8 S.E.2d 652 (1940) ------ 60

Burgess v. State, 256 Ala. 5, 53 So.2d 568 (1951) ....... 51

Burnette v. State, 157 So.2d 65 (Fla. 1963) ............ ...55, 61

Butler v. Alabama, O.T. 1970, No. 5492 ........ .................. 62

City of Toledo v. Reasonover, 5 Ohio St. 2d 22, 213

N.E.2d 179 (1965) .... ..................................................... 18

Commonwealth v. Brown, 309 Pa. 515, 164 A. 726

(1933) 58

I l l

Commonwealth v. Edwards, 380 Pa. 52, 110 A.2d 216

(1955)... ................................................................................ 64

Commonwealth v. Green, 396 Pa. 137, 151 A.2d 241

(1959) 64

Commonwealth v. Hough, 358 Pa. 247, 56 A.2d 84

(1948) ........................................................................ 55,64

Commonwealth v. McNeil, 328 Mass. 436, 104 N.E.2d

153 (1952) ..... 57,72

Commonwealth v. Nassar, 354 Mass. 249, 237 N.E.2d

39 (1968) ..................................... 57

Commonwealth v. Eoss, 413 Pa. 35, 195 A.2d 81 (1963) 62

Commonwealth v. Smith, 405 Pa. 456, 176 A.2d 619

(1962) 64

Commonwealth v. Taranow, 359 Pa. 342, 59 A.2d 53

(1948) .................... 55

Commonwealth v. Wooding, 355 Pa. 555, 50 A.2d 328

(1947) .......................................................................55,56,61

Commonwealth v. Zeitz, 364 Pa. 294, 72 A.2d 282 (1950) 64

Daniels v. State, 199 Ga. 818, 35 S.E.2d 362 (1945) .....60, 66

Davis v. State, 123 So.2d 703 (Fla. 1960) ........ ...... ....... 64

Davis v. State, 190 Ga. 100, 8 S.E.2d 394 (1940) ____ 60

Dinsmore v. State, 61 Neb. 418, 85 N.W. 445 (1901)__57, 60

Duisen v. State, ------- Mo. ------ , 441 S.W.2d 688

(1969) ............................................................................. 55, 56

PAGE

Edwards v. Commonwealth, 298 Ky. 366, 182 S.W.2d

948 (1944) ........................... ................ ...................... ...55,60

Ex parte Knight, 73 Ohio App. 547, 57 N.E.2d 273

(1944) ............................ ................................................ 19,21

Ex parte Kramer, 61 Nev. 174, 122 P.2d 862 (1942) ..... 54

IV

Ex parte Skaug, 63 Nev. 101, 164 P.2d 743 (1945) ____ 61

Fleming v. State, 34 Ohio App. 536, 171 N.E. 407

(1929), aff’d, 122 Ohio St. 156, 171 N.E. 27 (1930) .... 18

Franks v. State, 139 Tex. Grim. App. 42, 138 S.W.2d

109 (1940) ...................... .......... ...................................... 56

Furman v. Georgia, O.T. 1970, Misc. No. 5059 .... ........ . 62

Garner v. State, 28 Fla. 113, 9 So. 835 (1891) ...... ........ 61

Giaecio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399 (1966) ...............3, 68

Gohlston v. State, 143 Tenn. 126, 223 S.W. 839 (1920) 53

Grandsinger v. State, 161 Neb. 419, 73 N.W.2d 632

(1955) ....................................................................... 56,59,61

Hamilton v. Alabama, 368 U.S. 52 (1961) ....................... 81

Harrington v. California, 395 U.S. 250 (1969) ............... 79

Harris v. State, 183 Ga. 574, 188 S.E. 883 (1936) ____ 61

Hernandez v. State, 43 Ariz. 424, 32 P.2d 18 (1934) ....55, 61

Hicks v. State, 196 Ga. 671, 27 S.E.2d 307 (1943) ____ 61

Hill v. North Carolina, O.T. 1970, Misc. No. 5136 ....... 62

Hinton v. State, 280 Ala. 848, 189 So.2d 849 (1966) .... 55

Hopkins v. State, 190 Ga. 180, 8 S.E.2d 633 (1940) .... 61

Hoppe v. State, 29 Ohio App. 467, 163 N.E. 715

(1928) ...... ................................................. ......... ........... 19, 28

Howell v. State, 102 Ohio St. 411, 131 N.E. 706

(1921) ............................ ............. 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 66, 71

In re Anderson, 69 Cal.2d 613, 447 P.2d 117, 73 Cal.

Rptr. 21 (1968), O.T. 1970, Misc. No. 5118.......5-M, 47,48

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 (1964) ........ ............ ..... 78

Johnson v. New Jersey, 384 U.S. 719 (1966)...........75, 77, 81

PAGE

V

Johnson v. State, 61 So.2d 179 (Fla. 1952) .................. 64

Jones v. People, 146 Colo. 40, 360 P.2d 686 (1961) ....58, 60

Jones v. People, 155 Colo. 148, 393 P.2d 366 (1964) ....51, 60

Jones v. Commonwealth, 194 Va. 273, 72 S.E.2d 693

(1952) ...................................................................... .. 58

Kramer v. State, 60 Nev. 262, 108 P.2d 304 (1940) ....... 54

Lee v. State, 166 So.2d 131 (Fla. 1964) ........................... 51

Leopold v. People, 105 Colo. 147, 95 P.2d 811 (1939) .... 58

Licavoli v. State, 20 Ohio Ops. 562, 34 N.E.2d 450

(1935) ............................................................ .......... ........ 27

Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618 (1965) .......... .......... 57, 77

Liska v. State, 115 Ohio St. 283, 152 N.E. 667 (1926) ..27, 66

Lovelady v. State, 150 Tex.Crim.App. 50, 198 S.W.2d

570 (1947) ................ ................. ................. .......... ........... 56

Lovett v. State, 30 Fla, 142, 11 So. 550 (1892) .............. 61

McBnrnett v. State, 206 Ga. 59, 55 S.E.2d 598 (1949) 55

McCants v. Alabama, O.T. 1970, Misc. No. 5009 ........... 62

McCoy v. State, 191 Ga. 516, 13 S.E.2d 183 (1941) ....... 60

Manor v. State, 223 Ga. 594, 157 S.E.2d 431 (1967) .... 56

Marks v. Louisiana, O.T. 1970, Misc. No. 5007 ....... ....... 63

Massa v. State, 37 Ohio App. 532, 175 N.E. 219 (1930) 22,

26, 27

Mathis v. New Jersey, O.T. 1970, Misc. No. 5006 .......60, 62

Maxwell v. B ishop,------U.S. - — (1970) (O.T. 1969,

No. 13) .......................... ..... ...........................4-M, 5-M, 7,12

Merchant v. State, 217 Md. 61, 141 A.2d 487 (1958) .... 63

Montalto v. State, 51 Ohio App. 6, 199 N.E. 198 (1935) 18

Moore v. Illinois, O.T. 1970, Misc. No. 5056 ............... 63

Morissette v. United States, 342 U.S. 246 (1952) ....... 76

PAGE

VI

Newton v. State, 21 Fla. 53 (1884) ................................... 61

Pait v. State, 112 So.2d 380 (Fla. 1959) .............. ........ 61

People v. Aikens, 70 Cal.2d 369, 450 P.2d 258, 74 Cal.

Rptr. 882 (1969) ...................... .......... ...... ................ ..32,36

People v. Anderson, 63 Cal.2d 351, 406 P.2d 43, 46

Cal. Rptr. 763 (1965) ............................ ....................... 37

People v. Anderson, 64 Cal.2d 633, 414 P.2d 366, 51

Cal. Rptr. 238 (1966) ..... ..... ...... .......... .................. ...45, 47

People v. Baldonado, 53 Cal.2d 824, 350 P.2d 115, 3

Cal. Rptr. 363 (1960) .... ................... ............... .............. 32

People v. BancLhauer, 1 Cal.3d 609, 463 P.2d 408, 83

Cal. Rptr. 184 (1970) .................................................... 45

People v. Bandhaner, 66 Cal.2d 524, 426 P.2d 900, 58

Cal. Rptr. 332 (1967) ......... .......... ......... .............. 39, 40, 47

People v. Bernette, 30 IlL2d 359,197 N.E.2d 436 (1964) 55

People v. Bickley, 57 Cal.2d 788, 372 P.2d 100, 22 Cal.

Rptr. 340 (1962) ................ ...... ......... ................... 35,37,38

People v. Black, 367 111. 209, 10 N.E.2d 801 (1937) ....... 58

People v. Brawley, 1 Cal.3d 277, 461 P.2d 361, 82 Cal.

Rptr. 161 (1969) ..........................................................44,46

People v. Brice, 49 Cal.2d 434, 317 P.2d 961 (1957) .... 47

People v. Cartier, 54 Cal.2d 300, 353 P.2d 53, 5 Cal.

Rptr. 573 (1960) ..... ........ ........ ..................................... 47

People v. Ciucci, 8 111.2d 619, 137 N.E.2d 40 (1956) .... 58

People v. Clark, 62 Cal.2d 870, 402 P.2d 856, 44 Cal.

Rptr. 784 (1965) .... ............ ...... .................. .......... .....36,45

People v. Corwin, 52 Cal.2d 404, 340 P.2d 626 (1959) 35

People v. Crews, 42 IU.2d 60, 244 N.E.2d 593 (1969) .... 63

People v. Deptnla, 58 Cal.2d 225, 373 P.2d 430, 23 Cal.

Rptr. 366 (1962)

PAGE

32

PAGE

People v. Durham, 70 Cal.2d 171, 449 P.2d 198, 74 Cal.

Eptr. 262 (1969) ....... ......... ...................................35,36,40

People v. Feldkamp, 51 Cal.2d 237, 331 P.2d 632

(1958)............... ................ ............................................. ....35,48

People v. Floyd, 1 Cal.2d 694, 464 P.2d 64, 83 Cal.

Rptr. 608 (1970) .............. 35,38

People y . Friend, 47 Cal.2d 749, 306 P.2d 463 (1957) .... 41,

42,43, 44, 46,47

People v. Garner, 57 Cal.2d 135, 367 P.2d 680, 18 Cal.

Eptr. 40 (1961) ............................................................. 37

People v. Gilbert, 63 Cal.2d 690, 408 P.2d 365, 47 Cal.

Eptr. 909 (1966) ............................................................. 35

People v. Glatman, 52 Cal.2d 283, 340 P.2d 8 (1959) .... 33

People v. Golston, 58 Cal.2d 535, 375 P.2d 51, 25 Cal.

Eptr. 83 (1962) ............................................................. 32

People v. Gonzales, 56 Cal.2d 317, 363 P.2d 871, 14 Cal.

Eptr. 639 (1961) .......................................... 40

People v. Gonzales, 66 Cal.2d 482, 426 P.2d 929, 58 Cal.

Eptr. 361 (1967) ........................... 35

People y . Green, 47 Cal.2d 209, 302 P.2d 307 (1956) ....41, 47

People v. Griffin, 60 Cal.2d 182, 383 P.2d 432, 32 Cal.

Eptr. 24 (1963) rev’d on other grounds, 380 U.S. 609

(1965) ............................... 36,40

People v. Hamilton, 60 Cal.2d 105, 383 P.2d 412, 32 Cal.

Eptr. 4 (1963) ................ .....36,38,40,41,47

People v. Harrison, 59 Cal.2d 622, 381 P.2d 665, 30 Cal.

Eptr. 841 (1963) .......................................... 40, 41, 43, 44, 46

People v. Hill, 66 Cal.2d 536, 426 P.2d 908, 58 Cal.

Eptr. 340 (1967) ................................................38,40,41,48

People v. Hillery, 62 Cal.2d 692, 401 P.2d 382, 44 Cal.

Rptr. 30 (1965) 37

V l l l

People v. Hillery, 65 Cal.2d 795, 423 P.2d 208, 56 Cal.

Rptr. 280 (1967) ................................... 35,40,41,43,45,46

People y . Hines, 61 Cal.2d 164, 390 P.2d 398, 37 Cal.

Rptr. 622 (1964) ........ 36,39,42,47,70

People v. Howk, 56 Cal.2d 687, 365 P.2d 426, 16 Cal.

Rptr. 370 (1961) .......... ........ ...........35,40,41,42,43,47,48

People v. Imbler, 57 Cal.2d 711, 371 P.2d 304, 21 Cal.

Rptr. 568 (1962) ............ 37

People v. Jackson, 59 Cal.2d 375, 379 P.2d 937, 29 Cal.

Rptr. 505 (1963) .......... 35

People v. Jacobson, 63 Cal.2d 319, 405 P.2d 555, 46 Cal.

Rptr. 515 (1965) ............................................................. 35

People v. Jackson, 67 Cal.2cl 96, 429 P.2d 600, 60 Cal.

Rptr. 248 (1967) .............................................. - ...... ...... 32

People v. Jones, 52 Cal.2d 636, 343 P.2d 577 (1959) ....32, 33,

38,47, 67

People v. Ketehel, 59 Cal.2d 503, 381 P.2d 394, 30 Cal.

Rptr. 538 (1963) ............................................... 35,37,40,48

People v. Kidd, 56 Cal.2d 759, 366 P.2d 49, 16 Cal.

Rptr. 793 (1961) ............................................................. 37

People v. King, 1 Cal.3d 791, 463 P.2d 753, 83 Cal.

Rptr. 401 (1970) ............................................................. 32

People v. Lane, 56 Cal.2d 773, 366 P.2d 57, 16 Cal.

Rptr. 801 (1961) ..........................................37,40,41,43,44

People v. Langdon, 52 Cal.2d 425, 341 P,2d 303 (1959) 32

PAGE

People v. Linden, 52 Cal.2d 1, 338 P.2d 397 (1959) ....40,41,

43, 48

People v. Lindsey, 56 Cal.2d 324, 363 P.2d 910, 14 Cal.

Rptr. 678 (1961) ....................... .................................. 36,48

People v. Lookado, 66 Cal.2d 307, 425 P.2d 208, 57 Cal.

Rptr. 608 (1967) .......................................... ............... 32,48

PAGE

People v. Lopez, 60 Cal.2d 223, 384 P.2d 16, 32 Cal.

Rptr. 424 (1963) ......... ................................_..................

People v. Love, 53 Cal.2d 843, 350 P.2d 705, 3 Cal.

Eptr. 665 (1960) .......................................... ..... 35, 36, 38,

People v. Love, 56 Cal.2d 720, 366 P.2d 33, 16 Cal.

Rptr. 777, 17 Cal. Rptr. 481 (1961) ...............37,40,47,

People v, McClellan,------Cal.3d------- , 457 P.2d 871, 80

Cal. Rptr. 31 (1969) .......................................... ..........

People v. Mason, 54 Cal.2d 164, 351 P.2d 1025, 4 Cal.

Rptr. 841 (1960) ..............................................................

People v. Massie, 66 Cal.2d 899, 428 P.2d 869, 59 Cal.

Rptr. 733 (1967) ..............................................................

People v. Mathis, 63 Cal.2d 416, 406 P.2d 65, 46 Cal.

Rptr. 785 (1965) ..............................................................

People v. Mitchell, 63 Cal.2d 805, 409 P.2d 211, 48 Cal.

Rptr. 371 (1966) .............................................. 36,40,46,

People v. Modesto, 59 Cal.2d 722, 382 P.2d 33, 31 Cal.

Rptr. 225 (1963) ..............................................................

People v. Monk, 56 Cal.2d 288, 363 P.2d 865, 14 Cal.

Rptr. 633 (1961) ..............................................................

People v. Moore, 53 Cal.2d 451, 348 P.2d 584, 2 Cal.

Rptr. 6 (1960) ..................................................................

People v. Morse, 60 Cal.2d 631, 388 P.2d 33, 36 Cal.

Rptr. 201 (1964) .....................................................37, 40,

People v. Moya, 53 Cal.2d 819, 350 P.2d 112, 3 Cal.

Rptr. 360 (1960) ..............................................................

People v. Nicholans, 65 Cal.2d 866, 423 P.2d 787, 56 Cal.

Rptr. 635 (1967) ..............................................................

People v. N ye,------ Cal.3d--------, 455 P.2d 395, 78 Cal.

Rptr. 467 (1969) .....................................................38, 45,

36

,76

,48

36

47

32

36

48

36

48

48

46

37

48

46

X

People v. Oliver, 1 N.Y.2d 152, 151 N.Y.S.2d 367, 134

N.E.2d 197 (1956) .......................................................... 76

People v. Pike, 58 Cal.2d 70, 372 P.2d 656, 22 Cal.

Eptr. 664 (1962) .......................................... ............... 35,37

People v. Polk, 63 Cal.2d 443, 406 P.2d 641, 47 Cal.

Eptr. 1 (1965) .................................................. 36,44,45,47

People v. Parvis, 52 Cal.2d 871, 346 P.2d 22 (1959) ....36, 38

People v. Parvis, 56 Cal.2d 93, 362 P.2d 713, 13 Cal.

Eptr. 801 (1961) .................................................... ....... 41, 47

People v. Parvis, 60 Cal.2d 323, 384 P.2d 424, 33 Cal.

Eptr. 104 (1963) ........................... 37

People v. Eeeves, 64 Cal.2d 766, 415 P.2d 35, 51 Cal.

Eptr. 691 (1966) ...... ................................................32, 36, 48

People v. Eisenlioover, 70 Cal.2d 39, 447 P.2d 925, 73

Cal. Eptr. 533 (1968) ...................................................... 36

People v. Eittger, 54 Cal.2d 720, 355 P.2d 645, 7 Cal.

Eptr. 901 (1960) ............................... 48

People v. Shipp, 59 Cal.2d 845, 382 P.2d 577, 31 Cal.

Eptr. 457 (1963) ........................... 40

People v. Sieterle, 56 Cal.2d 320, 363 P.2d 913, 14 Cal.

Eptr. 681 (1961) ................. 32

People v. Sosa, 251 Cal. App.2d 9, 58 Cal. Eptr. 912

(1967) 32

People v. Spencer, 60 Cal.2d 64, 383 P.2d 134, 31 Cal.

Eptr. 782 (1963) .............................................................. 40

People v. Stanworth,------- Cal.3d------ , 457 P.2d 889, 80

Cal. Eptr. 49 (1969) ...................................................... 45

People v. Sullivan, 345 111. 87, 177 N.E. 733 (1931) ..... 58

People v. Tahl, 65 Cal.2d 719, 423 P.2d 246, 56 Cal.

Eptr. 318 (1967) ................................................ 33, 35, 36, 40

People v. Talbot, 64 Cal.2d 691, 414 P.2d 633, 51 Cal.

Eptr. 417 (1966) ...................................................... 35, 40, 41

PAGE

XX

PAGE

People y. Terry, 57 Cal.2d 538, 370 P.2d 985, 21 Cal.

Rptr. 185 (1962) .................................~....... 35, 37, 38,40,47

People v. Terry, 61 Cal.2d 137, 390 P.2d 381, 37 Cal.

Rptr. 605 (1964) ..... ................. 36,38,39,40,45,46,47,68

People y. Thomas, 65 Cal.2d 698, 423 P.2d 233, 56 Cal.

Rptr. 305 (1967) .............................................................. 40

People v. Varnum, 61 Cal.2d 425, 392 P.2d 961, 38 Cal.

Rptr. 881 (1964) .......................................................... ... 37

People v. Varnnm, 66 Cal.2d 808, 427 P.2d 772, 59 Cal.

Rptr. 108 (1967) ........................................... 36

People v. Vaughn,------ Cal.3d------ , 455 P.2d 122, 78

Cal. Rptr. 186 (1969) ...............................................-.36 ,45

People v. Washington,------Cal.2d--------, 458 P.2d 479,

80 Cal. Rptr. 567 (1969) ............................. 32,41,43,45,46

People v. Welch, 58 CaL2d 271, 373 P.2d 427, 23 Cal.

Rptr. 363 (1962) ......................................................37,48

People v. White, 69 Cal.2d 751, 446 P.2d 993, 72 Cal.

Rptr. 873 (1968) .......................... 40,47

People v. Whitmore, 251 Cal. App.2d 359, 59 Cal.

Rptr. 411 (1967) ........ 32

Pixley v. State, 406 P.2d 662 (Wyo. 1965) .......57, 59, 60, 61

Porter v. State, 177 Tenn. 515, 151 S.W.2d 171

(1941) ..............................................................................57,64

Rehfeld v. State, 102 Ohio St. 431, 131 N.E. 712

(1921) ..................................................................... -...... 24,25

Rice v. Commonwealth, 278 Ky. 43, 128 S.W.2d 219

(1939) .............................................-.......................... 51,61,64

Rice v. State, 250 Ala. 638, 35 So.2d 617 (1948) ............. 64

Roberts v. Russell, 392 U.S. 293 (1968) .........................75, 78

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962) ................... 76

Roseboro v. North Carolina, O.T. 1970, Misc. No. 5178 62

Xll

Scott v. State, 247 Ala. 62, 22 So.2d 529 (1945) ........... 64

Shelton v. State, 102 Ohio St. 376, 131 N.E. 704 (1921) 27

Shimniok v. State, 197 Miss. 179, 19 So. 760

(1944) ........... 57,62,64

Shnstrom v. State, 205 Ind. 287,185 N.E. 438 (1933) .... 63

Simmons v. United States, 390 U.S. 377 (1968) ........... 73

Smith & Riggins v. Washington, O.T. 1970, Misc. No.

5034 ............................ 63

Spain v. State, 59 Miss. 19 (1881) ....... 55,58,61

Spencer v. Texas, 3S5 U.S. 554 (1967) ......................... 65

State v. Alvarez, 182 Neb. 358, 154 N.W.2d 746

(1967) .............................................................. .52,63

State v. Ames, 50 Ohio Law Abs. 311, 80 N.E.2d 168

(1947), rehearing denied, 81 N.E.2d 238 (1948), app.

dism’d, 149 Ohio St. 192, 78 N.E.2d 48 (1948) ...........27, 28

State v. Anderson (Mo. Sapp.), 384 S.W.2d 591 (1964) 63

State v. Blakely, 158 S.C. 304, 155 S.E. 408 (1930) ....... 58

State v. Brown, 60 Wyo. 379, 151 P.2d 950 (1944) ....53, 56,

59, 61

State v. Bntner, 67 Nev. 936, 220 P.2d 631 (1950) ....... 64

State v. Caldwell, 135 Ohio St. 424, 21 N.E.2d 343

(1939) ....... 24,25,26,73

State v. Carey, 36 Del. 521, 178 A. 877 (Ct. Oyer &

Terminer 1935) ....................... 62

State v. Carter, 21 Ohio St.2d 212, 256 N.E.2d 714

(1970) ........... 23

State v. Cerar, 60 Utah 208, 207 P. 597 (1922) ............. 64

State v. Chasteen, 228 S.C. 88, 88 S.E.2d 880 (1955) .... 55

State v. Christenson, 166 Kan. 152, 199 P.2d 475 (1948) 55

State v. Clokey, S3 Ida. 322, 364 P.2d 159 (1961) ........... 60

PAGE

xm

State v. Collins, 50 Wash.2d 740, 314 P.2d 660 (1957) .... 58

State v. Cosby, 100 Ohio App. 459, 137 N.E.2d 282

(1955) ................................................................................ 28

State v. Crawford, 260 N.C. 548, 133 S.E.2d 232 (1963) 61

State v. Creighton, 330 Mo. 1176, 52 S.W.2d 556 (1932) 52

State v. Daniels, 231 S.C. 176, 97 S.E.2d 902 (1957) ..... 61

State v. Donahue, 141 Conn. 656, 109 A.2d 364

(1954) ........................................................................ 55,59,60

State y . Eaton, 19 Ohio St.2d 145, 249 N.E.2d 897

(1969) ..............................................................................23,25

State v. Ellis, 98 Ohio St. 21, 120 N.E. 218 (1918) ....20,21,

23, 24, 28

State v. Ferguson, 175 Ohio St. 390, 195 N.E.2d 794

(1964) 19,28

State v. Ferranto, 112 Ohio St. 667, 148 N.E. 362, 365

(1925) .......................................................... 19,20

State v. Forcella, 52 N.J. 263, 245 A.2d 181 (1968),

O.T. 1970, Misc. No. 5011 .................................... ........ 52, 57

State v. Frohner, 150 Ohio St. 53, 80 N.E.2d 868, 885

(1948) ........................................................................19,20,28

State v. Galvano, 34 Del. 323, 154 A. 461 (Ct. Oyer &

Terminer 1930) ...................................... 62

State v. Habig, 106 Ohio St. 151, 140 N.E. 195, 199

(1922) 19,20

State v. Harper, 251 S.C. 379, 162 S.E.2d 712 (1968) .... 53

State v. Henley, 15 Ohio St.2d 86, 238 N.E.2d 773

(1968) 27

State v. Henry, 197 La. 199, 3 So.2d 104 (1941) ....55, 61, 66

State v. Jackson, 227 La. 642, 80 So.2d 105 (1955) ......... 55

State v. Jarolowski, 30 Del. 108, 103 A. 657 (Ct. Oyer &

Terminer 1918)

PAGE

57

XIV

State v. Jones, 201 S.C. 403, 23 S.E.2d 387 (1942) ....... 55, 58

State v. Karayians, 108 Ohio St. 505, 141 N.E. 334

(1923) ..................... ......... ...................................22,26

State v. Kilpatrick, 201 Kan. 6, 439 P.2d 99 (1968) .... 64

State v. King, 158 S.C. 251, 155 S.E. 409 (1930) ........... 58

State v. Klnmpp, 1.5 Ohio Ops.2d 461, 175 N.E.2d 767

(1960), app. dism’d, 171 Ohio St. 62, 167 N.E.2d 778

(I960) ...... ........ ............... ........ ................................22, 27, 28

State v. Laster, 365 Mo. 1076, 293 S.W.2d 300 (1956) .... 63

State v. Laws, 51 N.J. 594, 242 A.2d 333 (1968) ........... 63

State v. Lee, 36 Del. 11, 171 A. 195 (Ct. Oyer & Ter

miner 1933) ......... ........... ........... ...................................57, 62

State v. Lucear, 93 Ohio App. 281, 109 N.E.2d 39

(1952) ........ 19,20,28

State v. Marsh, 234 N.C. 101, 66 S.E.2d 6S4 (1951) ....... 60

State v. McClellan, 12 Ohio App.2d 204, 232 N.E.2d

414 (1967) ..................... 20

State v. McGee, 91 Ariz. 101, 370 P.2d 261 (1962) ....... 63

State v. McMillan, 233 N.C. 630, 65 S.E.2d 212 (1951) 60

State v. Markham, 100 Utah 226, 112 P.2d 496

(1941) .................................................................. 53,56,58,64

State v. Meyer, 163 Ohio St. 279, 126 N.E.2d 585

(1955) ................................... 27

State v. Mount, 30 N.J. 195, 152 A.2d 343 (1959) .......55, 57,

59, 70

State v. Monzon, 231 S.C. 655, 99 S.E.2d 672 (1957) .... 63

State v. Mnskns, 158 Ohio St. 276, 109 N.E.2d 15 (1952) 27

State v. Narten, 99 Ariz. 116, 407 P.2d 81 (1965) ......... 70

State v. Owen, 73 Ida. 394, 253 P.2d 203 (1953) ....57, 58, 72

State v. Palen, 120 Mont. 434, 186 P.2d 223

(1947) ...... ................... ....................... ......................52, 55, 64

PAGE

XV

State v. Pierce, 44 Ohio Law Abs. 193, 62 N.E.2d 270

(Ohio App. 1945) ................................................... 24,25,27

State v. Porello, 138 Ohio St. 239, 34 N.E.2d 198 (1941) 28

State v. Pruett, 18 Ohio St.2d 167, 248 N.E.2d 605

(1969) ............................... ................................................ 23

State v. Pugh, 250 N.C. 278, 108 S.E.2d 649 (1959) ..... 61

State v. Ramirez, 34 Ida. 623, 203 P. 279 (1921) ........... . 63

State v. Reed, 85 Ohio App. 36, 84 N.E.2d 620 (1948) .... 28

State v. Reynolds, 41 N.J. 163, 195 A.2d 449 (1963) ....62, 69

State v. Riley, 41 Utah 225, 126 P. 294 (1912) ...........58, 61

State v. Robinson, 162 Ohio St. 486, 124 N.E.2d 148

(1955) ................................................................................ 29

State v. Robinson, 89 Ariz. 224, 360 P.2d 474 (1961) .... 63

State v. Romeo, 42 Utah 46, 128 P. 530 (1912) ...........58, 61

State v. Roseboro, ------ N.C. ------ , 171 S.E.2d 886

(1970) ............ 52,56

State v. Ruth, 276 N.C. 36, 170 S.E.2d 897 (1969) ....... 64

State v. Sahadi, 3 Ohio App.2d 209, 209 N.E.2d 758

(1964) 19,29

State v. Schiller, 70 Ohio St. 1, 70 N.E. 505 (1904) ....26, 27

State v. Simmons, 234 N.C. 290, 66 S.E.2d 897

(1951) ............. 55,61,64

State v. Skaug, 63 Nev. 59, 161 P.2d 708 (1945) ....... 61

State v. Smith, 123 Ohio St. 237,174 N.E. 768 (1931) .... 19

State v. Smith, 74 Wash.2d 744, 446 P.2d 571 (1968) .... 58

State v. Spino, 90 Ohio App. 139,104 N.E.2d 200 (1951) 18

State v. St. Clair, 3 Utah2d 230, 282 P.2d 323 (1955) .... 57

State v. Stewart, 176 Ohio St. 156, 198 N.E.2d 439

PAGE

(1964) .......................................... .......... ....... .............. ..19, 28

State v. Thorne, 39 Utah 208, 117 P. 58 (1911) ____58,61

State v. Thorne, 41 Utah 414, 126 P. 286 (1912) ........... 6L

State v. Tiedt, 360 Mo. 594, 229 S.W.2d 582 (1950) ___ 58

XV I

State v. Tudor, 154 Ohio St. 249, 95 N.E.2d 385

(1950) ... ......................................................... .............. ..21, 27

State v. Van Vlaek, 57 Ida. 316, 65 P.2d 736 (1937) ..... 61

State v. Vasquez, 101 Utah 444, 121 P.2d 903 (1942) 56, 58

State v. Walters, 145 Conn. 60,138 A.2d 786 (1958) ....56, 57,

59, 64

State v. Watson, 20 Ohio App.2d 115, 252 N.E.2d 305

(1969) ............... ................................................................ 27

State y. White, 60 Wash.2d 551, 374 P.2d 942

(1962) ..... 57,61,64

State y. Wigglesworth, 18 Ohio St.2d 171, 248 N.E.2d

607 (1969) ........ 23

State v. Winsett, 205 A.2d 510 (Del. Super. Ct.

1964) 57,62

State v. Worthy, 239 S.C. 449, 123 S.E.2d 835

(1962) .............................................................................. 58,61

State ex rel. Evans v. Eckle, 163 Ohio St. 122, 126

N.E.2d 48 (1955) ..... 19

State ex rel. Scott v. Alvis, 156 Ohio St. 387,102 N.E.2d

845 (1951) ............... 19

Stein v. New York, 346 U.S. 156 (1953) ....... .................... 81

Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293 (1967) ....................... ........ 81

Sukle v. People, 107 Colo. 269, 111 P.2d 233 (1941) ..... 58

Sullivan v. State, 47 Ariz. 224, 55 P.2d 312, 318

(1936) ........................................... 56,58

Sundahl v. State, 154 Neb. 550, 48 N.W.2d 689

(1951) ..................................... 56,57,60,61,63

Swain v. Alabama, O.T. 1970, Misc. No. 5327 ................. 62

Tehan v. United States ex rel. Shott, 382 U.S. 406

(1966) ............................................... 79

Thomas v. Florida, O.T. 1970, Misc. No. 5079 ............... 63

PAGE

xvn

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 101 (1958) ........................... 13

Turner v. State, 21 Ohio Law Abs. 276 (1936) ....... ........ 27

Turner v. State, 144 Tex. Grim. App. 327, 162 S.W.2d

978 (1942) ........................................................................ 64

Walker v. Nevada, O.T. 1970, Misc. No. 5083 ............... 63

Waters v. State, 87 Okla. Crim. App. 236, 197 P.2d

299 (1948) ........................................................................ 63

Wheat v. State, 187 Ga. 480, 1 S.E.2d 1 (1939) ....... .....58, 60

White v. Bhay, 64 Wash.2d 15, 390 P.2d 535 (1964) .... 61

White v. State, 227 Md. 615,177 A.2d 877 (1962), rev’d

on other grounds, 373 U.S. 59 (1963) ........................... 63

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S. 375 (1955) ....... ........ ...... , 81

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241 (1949) ................... 76

Williams v. State, 89 Okla. Crim. App. 95, 205 P.2d

524 (1949) ........................................................................ 63

Williams v. State, 119 Ga. 425, 46 S.E. 626 (1904) ____ 55

Wilson v. State, 286 Ala. 86, 105 So.2d 66 (1958) ......... 64

Wilson v. State, 225 So.2d 321 (Fla. 1969) ................... 56

Winston v. United States, 172 U.S. 303 (1899) ............ 50

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) (O.T.

1967, No. 1015) .................................. 3-M, 13, 73, 74, 75, 77

Woodruff v. State, 164 Tenn. 530, 51 S.W.2d 843

(1932) ........................................................................54,57,59

Wyett v. State, 220 Ga. 867,142 S.E.2d 810 (1965) ....... 58

Yates v. Cook, O.T. 1970, Misc. No. 5012................. 62

Yates v. State, 251 Miss. 376, 169 So.2d 792 (1964) .... 52

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 370 (1886) _____ 3

PAGE

XV111

Statutes:

18 U.8 .C. § i m (1964) .......... ................... ...... ............ . 50

Ala. Code Ann., tit. 14, §318 (Recomp. vol. 1958) ....... 54

Ariz. Rev. Stat. §13-453 (1956) ......................................... 51

Ariz. Rev. Stat. §13-1717(B) (1956) _________________ 63

Ark. Stat. Ann. §43-2153 (Repl. vol. 1964) ....... ........... 54

Cal. Acts Amendatory of the Codes 1873-1874, ch. 508,

§1 ......... -........................................................................... - 33

Cal. Const. Art. 1, § 7 ..... ..................................... ............... 32

Calif. Mil. & Yet. Code §1670 ......... ........ ..... .................. 31

Cal. Mil. & Vet. Code §1672(a) ............. ........ ................ 31

Cal. Pen. Code §3 7 .............................................................. 31

Cal. Pen. Code §128 ........... .................... .............. ............. 31

Cal. Pen. Code §190 ........................ ....... ........ ....... - .... -31, 33

Cal. Penal Code §190.1 _______ __ ________ ___ .-.31, 33, 34

Cal. Pen. Code §209 ................................... .......... — ...... . 31

Cal. Pen. Code §219 ............................ ......... ............. - ..... 31

Cal. Pen. Code §1026 ................................... ............ ....... 33

Cal. Pen. Code §1168 ............................................... ........... 31

Cal. Pen. Code §1168a ........................................................ 31

Cal. Pen. Code §4500 ..................................................... -15, 31

Cal. Pen. Code §5077 ............... ...............................- ...... - 31

Cal. Stats. 1957, ch. 1968, §2 ..... .......... ........... ........... 33

Cal. Stats. 1959, ch. 738, §1 .................................... ....... 33

Col. Rev. Stat. §40-2-3(1) (1965 Perm. cam. supp.) _.... 51

Col. Rev. Stat. §40-2-3(2)(a), (b) (1965 Perm. cnm.

snpp.) ............................................................. - .... — ...... 51

Col. Rev. Stat. §40-2-3(2) (c) (1965 Perm. cum.

supp.) ........ - ..................... .......................... -.................. 51,54

Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. §53-9 (1970-1971 Cum. pocket

part) ........ ......................................................................... 51

PAGE

X IX

Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. §53-10 (1970-1971 Cnm. pocket

part) ..........................................................................51, 54, 57

Del. Stat. Ann., tit. 11, §3901 (1968 Cum. pocket

part) .............................................................................. -53, 54

D.C. Code §22-2404 (1967) ..... ........................................... 50

Fla. Stat. Ann. §919.23(2) (1944) ................................... 54

Fla. Stat. Ann. §912.01 (1944) .......................................... 51

Fla. Stat. Ann., Rules Crim. Pro. 1.260 (1967).... .......... 51

Ga. Code Ann. §26-3102 (Criminal Code of Georgia,

1968-1969) ......................................................................51,54

Ga. General Assembly, 1970 Sess., H.B. No. 228 ........... 5

Ida. Code Ann. §18-4004 (1948) ...................................... 51, 54

111. Stat. Ann., tit. 38, §1-7 (c) (1) (1970 Cum. pocket

part) ........................................................................... —53, 54

111. Stat. Ann., tit. 38, § l-7 (c)(2 ) (1970 Cum. pocket

part) ........................................................................... — 51

111. Stat. Ann., tit. 38, §9-l(b) (1964) ...........................53,54

Burns Ind. Stat. Ann. §9-1819 (1956 Repl. vol.) ............. 51

Burns Ind. Stat. Ann., §10-3401 (1956 Repl. vol.) ......... 54

Kan. Stat. Ann. §21-4501(a) (1969 Cum. supp.) ...... .51,54

Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. §435.010 (1969) ................. ......... 51, 54

La. Stat. Ann., Code Crim. Pro., art. 557 (1967) ........... 52

La. Stat. Ann., Code Crim. Pro., art. 780 (1967) ........... 52

La. Stat. Ann., Code Crim. Pro. art. 817 (1967) ....... 52,54

Md. Code Ann., art. 27, §413 (Repl. vol. 1967) ...........53, 54

Mass. Ann. Laws, ch. 265, §2 (1968) .......................52, 54, 57

Miss. Code Ann., tit. 11, §2217 (Recomp. vol. 1956) ....52, 54

Vernon’s Mo. Stat. Ann. §546.410 (1953) ....................... 52

Vernon’s Mo. Stat. Ann. §546.430 (1953) ................... 63

Vernon’s Mo. Stat. Ann. §559.030 (1953) ................... 52,54

Mont. Rev. Code §94-2505 (Repl. vol. 1969) ...............52, 54

PAGE

X X

Neb. Rev. Stat. §28-401 (Reissue vol. 1964) ______ ___ 54

Nev. Laws 1967, oh. 523, §438, p. 1470 ........................... . 52

Xev. Rev. Stat. §200.030(3) ........................... .................. 54

N.H. Rev. Stat. §585:4 (1955) .......................................52,54

N.H. Rev. Stat. §585:5 (1955) ........................ 54

N.J. Stat. Ann. §2A:113-3 (1969) ............ 52

N.J. Stat. Ann. §2A:113-4 (1969) .................... 52,54,57

N.M. Laws 1969, cb. 128, §1, N.M. Stat. Ann., §40A-

29-2.1 (1970 Cum. Supp.) ................ .................... ..... 49,50

N.Y. Pen. Law §125.30 ................. ...................... .............. 50

N.C. Gen. Stat. §14-17 (Repl. vol. 1969) ............. ......... 52, 54

93 Ohio Laws 223 (S.B. No. 504) ............ ...................... . 20

115 Ohio Laws 531 (S.B. No. 90, §1.) _____ ____ _______ 19

Ohio Rev. Code, §2901.01 (Ohio Gen. Code, §12400) .... 20

Ohio Rev. Code, §2901.02 (Ohio Gen. Code, §12401) .... 20

Ohio Rev. Code §2901.03 (Ohio Gen. Code, §12402) .... 20

Ohio Rev. Code, §2901.04 (Ohio Gen. Code, §12402-1) .. 20

Ohio Rev. Code §2901.09 (Ohio Gen. Code, §12406) .... 19

Ohio Rev. Code, §2901.10 (Ohio Gen. Code, §12407) .... 19

Ohio Rev. Code, §2901.27 (Ohio Gen. Code §12427) .... 20

Ohio Rev. Code, §2901.28 (Ohio Gen. Code, §13386) .... 20

Ohio Rev. Code, §2907.141 (Ohio Gen. Code, §12441) .... 18

Ohio Rev. Code, §2907.09 (Ohio Gen. Code, §12437) .... 18

Ohio Rev. Code, §2945.06 (Ohio Gen. Code, §13442-5) __ 19

Ohio Rev. Code, §2945.11 (Ohio Gen. Code, §13442-9) .. 18

Okla. Stat. Ann., tit. 21, §707 (1958) .................... ........ ..53, 54

Pa. Laws 1794, eh. 257, §§1-2............................................ 6

Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., tit. 18, §4701 (1963) ....... ....53, 54

Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., tit. 19, Appendix, Rule Crim.

Pro. 1115 (1969 Cum. pocket part) ........................... 53

PAGE

X XI

S.C. Code Ann. §16-52 (1962) ............................................ 53

S.D. Comp. Laws. §§22-16-12, -13 (1967) ...................53, 54

S.D. Comp. Laws. §22-16-14 (1967) ............................... 53

Tenn. Code Ann. §39-2405 (1955) ...................... ........... .53, 54

Tenn. Code Ann. §39-2406 (1955) ............. ......... 53,54,57,59

Vernon’s Tex. Stat. Ann., Code Crim. Pro., art. 37.07

(2)(b) (1969-1970 Cum. pocket part) .......... ............ 53

Vernon’s Tex. Stat. Ann., Pen. Code, art. 1257 (1961) .. 53,

54

Vernon’s Tex. Stat. Ann., Pen. Code art. 1257 (a)

(1961) .................................................... 53

Utah Code Ann. §76-30-4 (1953) ........ ................... ...... 53,54

Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 13, §2303 (1969 Cum. Pocket Part) .. 50

Va. Code Ann. §18.1-22 (Repl. vol. 1960) ...................53, 54

Va. Code Ann. §19.1-250 (Repl. vol. 1960) ...................53, 54

Wash. Rev. Code §9.48.030 (1961) ...... ..... ............. ..... 53,54

Wyo. Stat. Ann. §6-54 (1957) ...................................... 53,54

PAGE

Other A uthorities

Advisory Council op J udges op the National Council

on Crime and Delinquency, Model Sentencing A ct,

§§5-9 (1963) ...................................................................... 9

A merican L aw Institute, Model P enal Code, Tent.

Draft No. 9 (May 8, 1959) .......................... ............... 76

A merican Law Institute, Model P enal Code, §210.6

(P.O.D., May 4, 1962) ....................................... -......... 9, 62

An cel, The Problem of the Death Penalty, in Sellin,

Capital P unishment (1967) 76

X XII

Bedau, Death Sentences in New Jersey 1907-1960, 19

Rutgers L. R ev. 1 (1964) .... ................................... ...4-M, 76

Bedau, The Courts, The Constitution, and Capital

Punishment, 1968 Utah L. Rev. 201, 232 (1968) ....... 77

Bedau, The Death Penalty in A merica (1964) 268 .... 76

California Jury Instructions, Criminal (CALJIC) 1.30

(Third rev. ed. 1970) ........................................ ............. 43

California Jury Instructions, Criminal (CALJIC) 8.80

(Third rev. ed. 1970) ____________ ____________ __ 42,43

California Jury Instructions, Criminal (CALJIC) 8.81

(Third rev. ed. 1970) ............ ............. ............ ............. 36

California Jury Instructions, Criminal (CALJIC) 8.82

(Third rev. ed. 1970) ...................................................... 38

Comment, The Death Penalty Cases, 56 Cal. L. Rev.

1268 (1968) ................. 30

Comment, The California Penalty Trial, 52 Cal. L.

R ev. 386 (1964) ................................................ ............. 30

DiSalle, Comments on Capital Punishment and Clem

ency, 25 Ohio St. L.J. 71, 72 (1964) ......... ................. 4-M

Duffy & H irshberg, 88 Men and 2 W omen (1962) ____4-M

Herman, An Acerbic Look at the Death Penalty in

Ohio, 15 W estern Reserve L. Rev. (1964) ......... ..... 28

Johnson, Selective Factors in Capital Punishment, 36

Social F orces 165 (1957) ............................................ 4-M

K oestler, Reflections on Hanging (Amer. ed. 1957)

144-152 ....... 76

Lawes, Twenty Thousand Y ears in Sing Sing (1932) 4-M

National Commission on Reform of Federal Criminal

Laws, Study Draft of a New Federal Criminal

Code, §§3601-3605 (1970)

PAGE

9

XXL11

Note, A Study of the California Penalty Jury in

First-Degree-Murder Cases, 21 Stan. L. R ev. 1297

(1969) ............... ......... ............. ................. ........ .....4-M, 30, 49

Note, Post-Conviction Remedies in California Death

Penalty Cases, 11 Stan. L. Rev. 94 (1958) ................ . 49

Note, The Void-for-Vagueness Doctrine in the Supreme

Court, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67, 81 (1960) ....................... 70

Ohio Department of Mental Hygiene and Corrections,

Ohio Judicial Criminal Statistics 1959; 1960; 1961;

1962; 1963; 1964; 1965; 1966; 1967; 1968 ..................29-30

Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Staff Research

R eport No. 46, Capital P unishment (January 1961)

54 ............ 29

P aley, P rinciples of Moral and P olitical P hilosophy

(11th Amer. ed. 1825) 384-386 .................................. .....6, 7, 8

P resident’s Commission on Law E nforcement and

A dministration of J ustice, Report (T he Challenge

of Crime in a F ree Society) (1967) 143 ............ .........12,13

1 R adinowicz, A H istory of E nglish Criminal L aw

and Its A dministration F rom 1750 (1948) 31-33 ..... 77

Reckless, The Use of the Death Penalty, 15 Crime &

Delinquency 43 (1969) ................................................... 49

R oyal Commission on Capital P unishment 1949-1953,

R eport (H.M.S.O. 1953) [Cmd. 8932] 1 7 ..................75-76

Sellin, The Death Penalty (1959) .............................. . 76

Sellin, The Death Penalty (1967) .......................... ........ 76

Statement by Attorney General Ramsey Clark, Before

the Subcommittee on Criminal Laws and Procedures

of the Senate Judiciary Committee, on S. 1760,

To Abolish the Death Penalty, July 2, 1968, De

partment of Justice Release, p. 2 .............................. 77

PAGE

XX1Y

PAGE

Symposium Note, The Two-Trial System in Capital

Cases, 39 N.Y.U.L. R ev. 50 (1964) .............................. 30

United States Department of Justice, Bureau of

Prisons, National Prisoner Statistics ......................... 30

No. 23, Executions 1959 (February, 1960) ........ 30

No. 26, Executions 1960 (March, 1961) ............... 30

No. 28, Executions 1961 (April, 1962) ................. 30

No. 32, Executions 1962 (April, 1963) ........... 30

No. 34, Executions 1930-1963 (May, 1964) ........ 30

No. 37, Executions 1964 (April, 1964) .................. 30

No. 39, Executions 1930-1965 (June, 1966) ......... 30

No. 41, Executions 1930-1966 (April, 1967) ....... 30

No. 42, Executions 1930-1967 (June, 1968) ........ 30

No. 45, Capital Punishment 1930-1968 (August

1969) ...................................................................15,30,50

2 W ith in , California Crimes, §§904-905 (1963) .......... 30

I n the

t o u r ! rtf % I n i t r i i S ta te s

October T erm , 1970

No. 203

D ennis Councle M cGautha,

Petitioner,

State oe California,

Respondent.

on writ oe certiorari to the supreme court of California

No. 204

J ames E dward Crampton,

—v.—

Petitioner,

State of Ohio,

Respondent.

on writ of certiorari to the supreme COURT OF OHIO

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

AND STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF THE AMICI

Movants N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., and National Office for the Rights of the Indi

gent respectfully move the Court for permission to file the

attached brief amici curiae, for the following reasons. The

reasons assigned also disclose the interest of the amici.

2-M

(1) The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc. (LDF) is a non-profit corporation formed to as

sist Negroes to secure their constitutional rights by the

prosecution of lawsuits. One of its charter purposes is to

provide free legal assistance to Negroes suffering injustice

by reason of race who are unable, on account of poverty, to

employ legal counsel. For many years, LDF attorneys have

represented in this Court and the lower courts persons

charged with capital crimes, particularly Negroes charged

with capital crimes in the Southern States.

(2) A central purpose of the LDF is the legal eradication

of practices in American society that bear with discrimina

tory harshness upon Negroes and upon the poor, deprived,

and friendless—who too often are Negroes. To further this

purpose, the LDF established in 1965 a separate corpora

tion, the National Office for the Rights of the Indigent

(NORI) having among its objectives the provision of legal

representation to the poor in individual cases and advocacy

before appellate courts in matters that broadly affect the

interests of the poor.

(3) The long experience of LDF attorneys in the han

dling of death cases has convinced us that capital punish

ment in the United States is administered in a fashion that

consistently makes racial minorities, the deprived and the

downtrodden, the peculiar objects of capital charges, capital

convictions, and sentences of death. We believe that this

and other grave injustices are referable in part to the

fundamental character of the death penalty as an institu

tion in modern American society,1 and in part to common

1 This point is developed at length in the Brief for the N.A.A.

C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., and the National

Office for the Rights of the Indigent, as Amici Curiae, in Boykin v.

3-M

practices in the trial of capital cases which depart alike

from the standards of an enlightened criminal justice and

from the minimum requirements of fairness and even-

handedness fixed by the Constitution of the United States

for proceedings by which life may be taken. Finally, we

have come to appreciate that in the uniquely stressful

processes of capital trials and direct appeals, ordinarily

handled by counsel appointed for indigent defendants,

many pressures and conflicts may impede the presentation

of effective attacks on these unfair and unconstitutional

practices ;2 and that in the post-appeal period, such attacks

are grievously handicapped by the ubiquitous circum

stance that the inmates of the death rows of this Nation are

as a class impecunious, mentally deficient, unrepresented

and therefore legally helpless in the face of death.3 * * * * * * * II

Alabama, 395 U.S. 238 (1969) (O.T. 1968, No. 642), wherein "we

urged that the death penalty was a cruel and unusual punishment

forbidden by the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.

2 Two of these practices are at issue in the present cases. Others

are described in our amici curiae brief in Boykin v. Alabama, note

I supra, at pp. 3-7, nn. 6, 7; and in the Brief Amici Curiae of the

N.A.A.C.P, Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., and the

National Office for the Eights of the Indigent, in Witherspoon v.

Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) (O.T. 1967, No. 1015), pp. 12-28.

3 In 1967, counsel for the amici instituted the case of Adderly

v. Wainwright, U.S.D.C., M.D. Fla., No. 67-298-Civ-J, by a class-

action petition for a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of all con

demned men in the State of Florida. In connection with the Dis

trict Court’s determination "whether it should entertain such a

proceeding in class-action form, it authorized counsel to conduct

interviews of all the inmates of Florida’s death row. The findings

of these court-ordered interviews, subsequently reported by counsel

to the court and relied upon in the court’s decision that class-action

proceedings were proper, indicated that of the 34 men interviewed

whose direct appeals had been concluded, 17 were without legal

representation (except for purposes of the Adderly suit itself) ;

II others were represented by volunteer lawyers associated with

the LDF or the ACLU; and in the case of two more, the status of

4-M

(4) For these reasons, amici LDF and NOM undertook

in 1967 to represent all condemned men in the United States

for whom adequate representation could not otherwise he

found. In less than three years, we have come to represent

about 200 of the approximately 550 men on death row,4 and

to provide consultative assistance to attorneys for a large

number of the others. In this Court, we represent twenty-

one men and one woman under sentences of death, whose

cases are pending on petitions for certiorari that raise one

or both of the issues presented by the present cases. We

briefed and argued those issues before the Court in Max-

legal representation was unascertainable. All 34 men (and all

other men interviewed on the row) were indigent; the mean in

telligence level for the death row population (even as measured

by a nonverbal test which substantially overrated mental ability

in matters requiring literacy, such as the institution and main

tenance of legal proceedings) was below normal; unrepresented

men were more mentally retarded than the few who were repre

sented ; most of the condemned men were, by occupation, unskilled,

farm or industrial laborers; and the mean number of years of

schooling for the group was a little over eight years (which does

not necessarily indicate eight grades completed). These findings

parallel those both of scholars who have undertaken to describe

the characteristics of the men on death row, e.g., Sedan, Death

Sentences in New Jersey 1907-1960, 19 Rutgers L. Rev. 1 (1964) ;

Johnson, Selective Factors in Capital Punishment, 36 Social

F orces 165 (1957); Note, A Study of the California Penalty Jury

in First-Degree-Murder -Cases, 21 Stan. L. Rev. 1297, 1337-1339,

1376-1379, 1384-1385, 1418 (1969), and of officials experienced in

dealing with death-row inmates, e.g., DiSalle, Comments on Capi

tal Punishment and Clemency, 25 Ohio St. L.J. 71, 72 (1964) :

“ I want to emphasize that from my own personal experience

those who were sentenced to death and appeared before me

for clemency were mostly people who were without funds for

a full and adequate defense, friendless, uneducated, and with

mentalities that bordered on being defective.”

Accord: Lawes, Twenty Thousand Years in Sing Sing (1932),

302, 307-310; Duffy & Hirshberg, 88 Men and 2 W omen (1962),

256-257.

4 See note 18 infra.

5-M

well v. B ishop,------ U .S .--------, 26 L. Ed.2d 221, 90 S. Ct.

1578 (1970) (O.T. 1969, No. 13), and handled the California

Supreme Court case of In re Anderson, 69 Cal.2d 613, 447

P.2d 117, 73 Cal. Eptr. 21 (1968), upon which that court's

decision in the present McGautha case rests. The Anderson

matter is currently pending on petition for certiorari as

O.T. 1970, Misc. No. 5118.

(5) We seek to file this brief amici curiae, urging re

versal, in order to place the issues before the Court in a

broader perspective than that provided by these two Cali

fornia and Ohio cases. Presentation of the broader perspec

tive is particularly important because, in certain aspects,

California and Ohio capital-trial practices differ from those

of many other States—for example, the Arkansas practice

involved in Maxwell v. Bishop. We shall explore those dif

ferences and their significance. It is not our purpose to re

hash the arguments that we made so recently in Maxwell.

For the Court’s convenience, should it wish to consult those

arguments, we append our Maxwell brief to this one (Ap

pendix A, infra). It develops our basic constitutional con

tentions. In the body of this present brief, we advance

several additional considerations that we think should be

brought to the attention of the Court, relative to the interest

of the 550 men (and, insofar as we are advised, 3 women)

whose lives immediately depend upon what the Court de

cides herein.

(6) Both parties in McGautha and petitioner in Cramp-

ton have consented to the filing of a brief amici curiae by

LDF and NOEI. The present motion is necessitated be

cause counsel for the State of Ohio has refused consent in

Crampton.

6-M

W hebefobe, movants pray that the attached brief amici

curiae be permitted to be filed with the Court.

Bespectfully submitted,

J ack Gbeenbebg

J ames M. Nabbit, I I I

J ack H immelstein

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

M ichael M eltskeb

Columbia University School of Law

New York, New York 10027

A nthony G. A mstebdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., and the National Office for

the Bights of the Indigent

I n th e

©ourt ni % llxnUin States

October T erm , 1970

No. 203

D ennis Cotjncle M cGau th a ,

Petitioner,

State of California,

Respondent.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI t o THE SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA

No. 204

J ames E dward Champion ,

-v.-

Petitioner,

State of Ohio ,

Respondent.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E SUPREME COURT OF OHIO

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

2

Summary of Argument

I.

The power of the States to punish crime with death is

not in issue here. What is in issue is their use of an arbi

trary system to select the men who die. The basic irration

ality of capital punishment may make the designing of non-

arbitrary selective procedures more difficult than the use

of arbitrary ones. But it cannot, consistent with Due Proc

ess, justify arbitrary procedures.

II.

A procedure by which jurors are empowered to choose

between life and death without standards or principles of

general application to guide and confine that choice is es

sentially lawless. For the reasons developed in our brief

in Maxwell v. Bishop, it violates the rule of law basic to

Due Process. The California and Ohio versions of the pro

cedure challenged here are not constitutionally differen

tiable from the Arkansas procedure at issue in Maxwell.

III.

Ohio’s single-verdict capital trial procedure is also un

constitutional for the reasons that we urged against Arkan

sas’ similar procedure in Maxwell.

IV.

A decision invalidating standardless capital sentencing

by juries or the single-verdict capital trial procedure should

be given fully retroactive effect, to the extent of forbidding

execution of the sentence of death upon any man condemned

to die under those procedures.

3

A R G U M E N T

I.

Introduction.

As the Court begins anew to deliberate the difficult

constitutional questions raised by standardless capital

sentencing and by the single-verdict capital trial procedure,

it is vital to identify succinctly what is, and what is not,

legally at issue and practically at stake.

The federal constitutionality of capital punishment, as

such, is not in question. The only question is whether

certain 'procedures for administering capital punishment

comply with basic safeguards of the Constitution designed

to forbid the use of arbitrariness as a tool of American

government.5 That limitation of the issue has several

important implications.

First, the interest that the States of California and Ohio

are asserting in these cases is not an interest in the main

tenance of the death penalty for the crime of murder.

Nothing that the Court could conceivably decide in either

case would deprive the States (or the National Government)

of the power to employ death as a punishment for any

crime. To the extent that this extreme resort is legislatively

believed to be a necessary and proper means of social

5 “ Certainly one of the basic purposes of the Due Process Clause

has always been to protect a person against having the Govern

ment impose burdens upon him except in accordance with the valid

laws of the land.” Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399, 403

(1966). For “ the very idea that one man may be compelled to

hold his life, or the means of living, or any material right essential

to the enjoyment of life, at the mere will of another, seems to be

intolerable in any country where freedom prevails, as being the

essence of slavery itself.” Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 370

(1886).

4

defense, no holding of this Court herein would or could

disable it.

Second, the interest that the States are asserting here is

not an interest in the regular and systematic use of the

punishment of death as an instrument of state penal policy.

It is not a considered legislative prescription of that

punishment for all or most murderers or other “ capital”

criminals, or for any legislatively determined sub-class,

kind, type or sort of murderers or “ capital” criminals. It

is not a legislative determination that any societal interest

makes it necessary and proper that Dennis Councle Mc-

Gautha or James Edward Crampton or any other man or

woman convicted of murder should forfeit his life. For not

only have the legislatures of California and Ohio failed to

decide the question when, if ever, some interest of society

requires that life be taken; they have failed to provide

procedures by which any responsible organ of government

decides that question.

Consistently with the capital punishment laws of those

States, California and Ohio juries might never sentence a

murderer to die; they might sentence all murderers to die;

or, if—as is most likely—they distinguish some murderers

from others, they are perfectly free to kill some and spare

the remainder for reasons which have absolutely no relation

to the purposes for which capital punishment was legis

latively authorized in the first place. For the moment, we

are not concerned with the constitutional issues raised by

this sort of procedure, but only with the States’ interest

in maintaining it. That interest is manifestly not any one

that might be served by the efficient selective use of death

as an anti-crime device, since the very methods of selectivity

in question here preclude decision of the question who shall

5

live and who shall die conformably with principles of anti

crime efficiency—or any other principles in which the State

may have a stake.

Third, the States’ interest here is not in preserving pro

cedures that either are or have been determined legislatively

to be essential for the administration of capital punish

ment. That is obvious enough with regard to the single

verdict procedure (since six States, including California,

now use a form of split-verdict procedure for the trial of

capital cases) ;6 but, as regards the matter of the arbitrary

discretion given juries in capital sentencing, the Attorneys

'General of Arkansas and California appeared to have been

urging this Court in Maxwell v. Bishop either that the

formulation of standards for non-arbitrary capital sentenc

ing was impossible, or at least that the Court should

respect the legislative judgment that it was impracticable.

The argument of impossibility ignores alike history and

the existence of contemporary models of standards for

capital sentencing. The historical oversight is glaring,

inasmuch as prior to the advent of the Twentieth Century,

virtually all capital statutes provided standards for impos

ing the death sentence: namely, the legislative definition of

the capital crime itself. Mandatory capital crimes provide

one form of standards for the imposition of the death

penalty, although not the only form. For centuries, legis

latures evolved those standards; and during the Nine

teenth, particularly, legislatures in this country and in

England drastically reduced the reach of the death penalty

6 Effective July 1, 1970, Georgia became the sixth State. Ga.

General Assembly, 1970 Sess., H.B. No. 228. The other five States

are California, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania and Texas.

See our Maxwell brief, Appendix A infra, pp. 77-78 n. 79.

6

both by removing some crimes from the roster of capital

offenses and by redefining or subdividing others—provid

ing, for example, degrees of murder.7 So it is rather

surprising to hear advanced today, in support of standard

less capital sentencing, the precise argument used by

Archdeacon William Paley in 1785 to justify England’s

“ Bloody Code” of more than 250 capital crimes: that be

cause “ it is impossible to enumerate or define beforehand

. . . those numerous unforeseen, mutable and indefinite

circumstances, both of the crime and the criminal, which

constitute or qualify the malignity of each offence,” the

proper course is to “ [sweep] into the net every crime which,

under any possible circumstances, may merit the punish

ment of death; but, when the execution of this sentence

comes to be deliberated upon, a small proportion of each

class are singled out” for the actual business of dying.

“ The wisdom and humanity of this design,” Paley con

cluded, “ furnish a just excuse for the multiplicity of capital

offences, which the laws of England are accused of creating

beyond those of other countries.” 8

7 The first jurisdiction to divide murder into degrees was Penn

sylvania, by a statute of 1794. Pa. Laws 1794, ch. 257, §§1-2.

That statute, like its successors which wrere enacted in virtually

every one of the United States during the following century, re

served the death penalty for murder in the first degree. Its

Preamble recited that public safety was best secured by moderate

and certain punishments, rather than by severe and excessive ones,

that “ it is the duty of every Government to endeavor to reform,

rather than exterminate offenders, and [that] the punishment of

death ought never to be inflicted, where it is not absolutely neces

sary to the public safety.”

8 Paley, Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy filth

Amur, ed. 1825), 384-386:

“ There are two methods of administering penal justice.

“ The first methods assigns capital punishments to few of

fences and inflicts it invariably.

(footnote continued on next page)

7

Paley’s sanguinary peroration furnishes an exact counter

part of the argument made before this Court by California

in the Maxwell case: that standardless capital sentencing

is warranted by the State’s interest in retaining the death

penalty while preserving the quality of “mercy” uncon

strained. We shall return shortly to this ironic invocation

of the concept of mercy to justify arbitrary procedures for

killing people. At this juncture, it suffices to say that the

“ The second method assigns capital punishments to many

kinds of offences, but inflicts it only upon a few examples of

each kind.

“ The latter of which two methods has been long adopted in

this country, where, of those who receive sentence of death,

scarcely one in ten is executed. And the preference of this

to the former method seems to be founded in the considera

tion, that the selection of proper objeets for capital punish

ment principally depends upon circumstances, which however

easy to perceive in each particular case after the crime is

committed, it is impossible to enumerate or define beforehand;

or to ascertain however with that exactness, which is requisite

in legal definitions. Hence, although it be necessary to fix

by precise rules of law the boundary on one side . . ., that

nothing less than the authority of the whole legislature be

suffered to determine that boundary, and assign these rules;

yet the mitigation of punishment, the exercise of lenity, may

without danger be entrusted to the executive magistrate,

whose discretion wall operate upon those numerous unfore

seen, mutable and indefinite circumstances, both of the crime

and the criminal, which constitute or qualify the malignity

of each offence... .

“For if judgment of death "were reserved for one or two

species of crimes only (which would probably be the case if

that judgment was intended to be executed without excep

tion), crimes might occur of the most dangerous example, and

accompanied with circumstances of heinous aggravation, which

did not fall within any description of offenses that the laws

had made capital, and which consequently could not receive

the punishment their own malignity and the public safety

required. . . .

“ The law of England is constructed upon a different and

a better policy. By the number of statutes creating capital

8

interest of mercy, like the other interests that we have

identified thus far, is nowise threatened by petitioners’

contentions in these cases. Their argument against arbi

trary capital sentencing is not an argument for mandatory

capital crimes (although, of course, the enactment of

mandatory capital crimes would avoid it, in the fashion of

throwing the baby out with the bath). It is an argument

that where discretion is given to a legal tribunal in a matter

so grave as the taking or sparing of human life, that dis

cretion must be suitably refined, directed and limited, so as

to ward against wholly lawless caprice. Devices for provid

ing that kind of protection are quite readily available which

nevertheless allow the capital-sentencing jury (not to speak

of the Governor)9 ultimate powers of mercy.

We mentioned above certain contemporary models of

such devices, principally the capital-sentencing provisions

offences, it sweeps into the net every crime which, under any

possible circumstances, may merit the punishment of death;

but, when the execution of this sentence comes to be deliber

ated upon, a small proportion of each class are singled out,

the general character, or the peculiar aggravations, of whose

crimes render them fit examples of public justice. By this

expedient, few actually suffer death, whilst the dread and

danger of it hang over the crimes of many. . . . The wisdom

and humanity of this design furnish a just excuse for the

multiplicity of capital offences, which the laws of England

are accused of creating beyond those of other countries. . . . ”

9 We hardly need say that nothing involved in these cases, or in

petitioners’ arguments, touches the clemency power of the execu

tive. Conversely, to recognize the unfettered character of that

power is not to legitimate giving a similar power to sentencing

juries. It is one thing to say that a man, once condemned to die

by procedures whose lawful regularity satisfies the concerns of

Due Process, may then be subjected to the unlimited authority of

commutation. It is quite another thing to say that a man may be

killed pursuant to a process which at no stage of the decision to

kill him satisfies Due Process concerns.

9

of the Model Penal Code10 and of the Study Draft recently

published by the National Commission on Reform of

Federal Criminal Laws.11 Both of these provisions use a

variety of means to assure regularity and delimit dis

cretion in capital sentencing: the prescription of circum

stances which exclude the death penalty; the requirement

of specified findings which allow the death penalty; the

enumeration of criteria for determination in cases where

it is allowed; and the subjection of that determination to

judicial review at the trial and appellate levels under the

same criteria. Alternatively, capital sentencing procedures

could be designed along the lines of the extended-sentencing

provisions of the Model Sentencing Act of the N.C.C.D.,12

directing specified inquiries into the defendant’s back

ground and propensities. These approaches might be

combined, or others adopted.13 None would prohibit either

capital punishment or mercy, while restricting the jury’s

power simply to take away life arbitrarily.

As for the suggestion that California’s or Ohio’s legis

lature, or any other, has determined that these approaches

are impracticable—a determination, so the suggestion goes,

that this Court should respect—that is quite fallacious. To

be sure, it is true that American legislatures have in fact

given their juries arbitrary capital sentencing power, as

10 A merican Law Institute, Model Penal Code, §210.6

(P.O.D., May 4, 1962), pp. 128-132.

11 National Commission on Beform of Federal Criminal

Laws, Study Draft of a New Federal Criminal Code, §§3601-

3605 (1970), pp. 307-311.

12 A dvisory Council of Judges of the National Council on

Crime and Delinquency, Model Sentencing A ct, §§5-9 (1963).

13 S ee o n r Maxwell b r ie f , A p p e n d ix A , infra p p . 38-45, 63-64

n. 67.

10

once they were wont to give their police chiefs arbitrary

powers of licensure of public meetings before this Court

forbade. Often it is the easier course, legislatively, to cast

the net overbroadly, particularly where the courts have not

identified constitutional interests that require otherwise.

But to read into such a course the determination that other

courses are impracticable—as distinguished from merely

more exacting—is to read what no legislature has written.

The plain fact of the matter is that the arbitrary death-

sentencing procedures challenged in these cases and perva

sive in the United States today represent the several

legislatures’ easy way out of the problem of devising work

able methods of selection of the persons who should die,

once mandatory capital punishment for murderers and

other “ capital” criminals became politically untenable.

Wholesale execution of the persons guilty of these crimes

is no longer tolerable to enlightened public opinion;

differentiation among them is difficult, particularly since

the purposes of the death penalty are diffuse, controversial,

and—when exposed to rational debate—too unsubstantial

to command agreement either upon those purposes them

selves or upon the uses of the death penalty appropriate to

achieve them;14 so the matter is simply handed over to

individual juries to kill or not, as they please.

And here one touches, we believe, the real interest of the

States of California and Ohio in the present cases. That is

an interest in maintaining the death penalty while avoiding

the responsibility for rationalizing it to the extent necessary

in order to assure its regular, consistent, non-arbitrary

application. Or, to put the matter the other way around, it

14 See note 154 infra.

11

is an interest precisely in maintaining arbitrary proeednres

for administration of the death penalty and selection of

the men to die, lest, in the process of formulating non-

arbitrary selective procedures, the death penalty be ex

posed to legislative and public scrutiny that might severely

restrict or even wholly condemn it.

To this extent only do these cases implicate a possible

restriction of state power to impose death as a penalty for

crime. If petitioners prevail in both their claims here, a

State which chooses to kill human beings in the service of

some penal policy will have to give considered legislative

attention to its reasons for doing so, and to the design of

standards and procedures for selection of the men it will