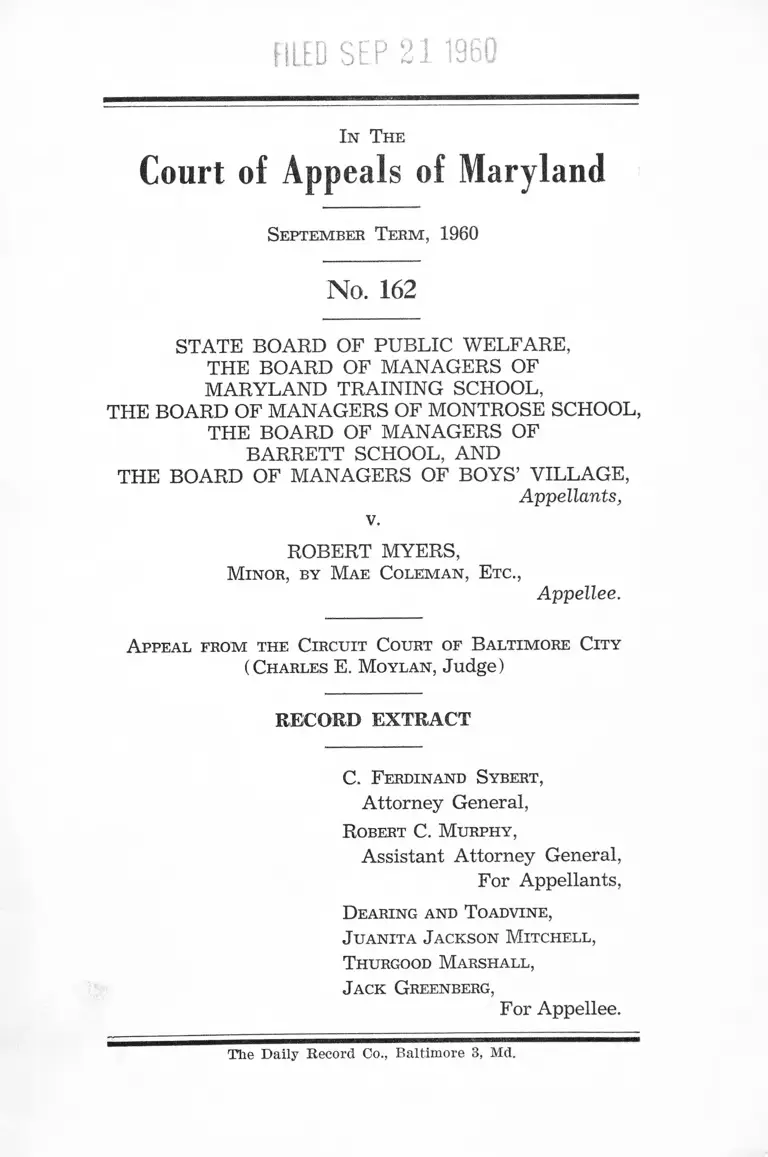

State Board of Public Welfare v. Myers Record Extract

Public Court Documents

September 21, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. State Board of Public Welfare v. Myers Record Extract, 1960. bd5c6e20-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a272c984-80f9-420b-9cdb-19f23e44912e/state-board-of-public-welfare-v-myers-record-extract. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

IILIO SEP 21 I960

In The

Court of Appeals of Maryland

September Term , 1960

N o. 162

STATE BOARD OF PUBLIC WELFARE,

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF

MARYLAND TRAINING SCHOOL,

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF MONTROSE SCHOOL,

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF

BARRETT SCHOOL, AND

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF BOYS’ VILLAGE,

Appellants,

v.

ROBERT MYERS,

Minor, by Mae Coleman, Etc.,

Appellee.

A ppeal from the Circuit Court of Baltimore City

(C harles E. Moylan, Judge)

RECORD EXTRACT

C. Ferdinand Sybert,

Attorney General,

Robert C. Murphy,

Assistant Attorney General,

For Appellants,

Dearing and Toadvine,

Juanita Jackson Mitchell,

Thurgood Marshall,

Jack Greenberg,

For Appellee.

The Daily Record Co., Baltimore 3, Md.

I N D E X

PAGE

Docket Entries ............................................................. 1

Bill of Complaint......................................................... 3

Demurrer and Answer..... .......................................... 13

Testimony:

For Appellee: ' ! !

Mae Coleman-

Direct ............................................ 43

Alvin Thalheimer—

Direct ..................................................... 47

Raymond Manella—

Direct ..................................................... 59

Cross ....................................................... 69

J. Martin Poland-

Direct ..................................................... 72

Cross ....................................................... 76

For Appellant:

Raymond Manella—

Direct ..................................................... 76

Elbert Fletcher—

Direct ..................................................... 89

Cross ....................................................... 93

Opinion of Court ......................................................... 96

Declaratory Decree..................................................... 117

11

PAGE

Exhibits:

Plaintiff’s Exhibit 1: File in action in Circuit

Court of Baltimore City, Division for Juvenile

Causes, in the matter of Robert Myers, minor

— Docket 65544 ..................................................... 118

Plaintiff’s Exhibit 2A: Letter of October 21,

1955, from W. Thomas Kemp to Attorney

General.................................................................. 18

Plaintiff’s Exhibit 2B: Opinion of January 11,

1956, from Attorney General to Kemp .............. 18

Plaintiff’s Exhibit 2C: Letter of June 24, 1957,

from Clayton Dietrich to State Department of

Public Welfare ................................................. 29

Plaintiff s Exhibit 2D: Opinion of September 10,

1959, from Attorney General to State Depart

ment of Public W elfare............................... 30

Plaintiff’s Exhibit 3: Statement of Information

on the Educational Program at Maryland

Training School for B oys................................. 35

Defendant’s Exhibit 1: Pamphlet entitled “Char

acteristics of 860 committed children in the

Maryland Training Schools on January 1, I960:

Table 1 — Ages ............................................ 122

Table 3 — Number of Commitments and

Recommitments ......................... 123

Table 12 Types of Offenses Causing

Commitment ............................... 124

I n T he

Court of Appeals of Maryland

September Term , 1960

N o. 162

STATE BOARD OF PUBLIC WELFARE,

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF

MARYLAND TRAINING SCHOOL,

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF MONTROSE SCHOOL,

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF

BARRETT SCHOOL, AND

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF BOYS’ VILLAGE,

Appellants,

v.

ROBERT MYERS,

M inor, by Mae Coleman, Etc.,

Appellee.

A ppeal from the Circuit Court of Baltimore City

(C harles E. Moylan, Judge)

RECORD EXTRACT

DOCKET ENTRIES

February 26,1960 — Bill of Complaint to declare Sections

657, 658, 660 and 661 of Article 27 of Annotated Code of

Maryland, 1957 Edition as Amended, are unconstitutional

and for an Injunction (1) fd.

March 19, 1960 — App. of Defendants, State Board of

Public Welfare, etc., by their Solrs. Ferdinand Sybert and

Robert C. Murphy and their Demurrer and Answer to Bill

of Complaint (16) fd.

April 22, 1960 — Motion for Hearing (17) fd. Same day

Notice of Hearing (18) issd. (Served). Same day Peti

tion of Plaintiff for leave to take Testimony under 560th

Rule and Order thereon authorizing same (19) issd.

(Served).

June 2, 1960 — Defendants Summons for Witnesses (20)

issd. (Summoned as Marked.) Same day Defendants

summons for Witness (21) issd. (Summoned)

June 3, 1960 — Summons Plaintiff’s Witness (22) issd.

(Tardy.) Same day Summons Plaintiff’s Witnesses (23)

issd. (Summoned as Marked.)

July 6, 1960 — Opinion of Court (24) fd.

July 6, 1960 — Decree of Court declaring Maryland’s

Public Training Schools are part of the public education

system, further declaring that those parts of Sections 657

and 659-661 of Article 27 of the Annotated Code of Mary

land, 1957 Edition, which requires separation of Negro and

White races in the four training schools violate both the

equal rights and the due process clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States, and

are unconstitutional, further declaring that the Court can

not select a Training School to which a minor is to be com

mitted on the basis of the minor’s race or color; and further,

forever and permanently enjoining and restraining Defen

dants, &c. from denying to Plaintiff and other Negro

Youths, solely on account of race and color, commitment,

admission and transfer to any Training School established,

operated and maintained by the State of Maryland, Defen

dants to pay costs (25) fd.

July 7, 1960 — Defendants Order for Appeal (26) fd.

July 29, 1960 — Petition of Defendants for extension of

time for transmitting record to Court of Appeals and

Order of Court thereon extending said time to and includ

ing August 31, 1960 (27) fd.

E. 3

August 2, 1960 — Testimony (28) fd.

August 3, 1960 — Plaintiff’s Exhibits No. 1 (29) 2-A (30)

2-B (31) 2-C (32) 2-D (33) 3 (34) 4 (35) 5 (36) fd. Same

day Defendants Exhibit No. 1 for Identification (37) fd.

BILL OF COMPLAINT

To the Honorable, the Judge of said Court :

Now comes Robert Myers, by Mae Coleman, his mother

and next friend, plaintiff herein, on behalf of himself and

others similarly situated but too numerous to be named

herein, by his attorneys, Tucker R. Bearing, Juanita Jack-

son Mitchell, Thurgood Marshall and Jack Greenberg for

his cause of action against the following:

State Board of Public Welfare, defendant, and Dr. Alvin

Thalheimer, Chairman, Calhoun Bond, Ralph O. Dulany,

Sam Eig, Gen. Henry C. Evans, Sanford Y. Larkey, Howard

H. Murphy, Herbert R. O’Conor, Mrs. John L. Sanford,

defendant members of the State Board of Public Welfare;

The Board of Managers of Barrett School for Girls, In

corporated, defendant, and Miss Anita R. Williams, Acting

President, Mrs. Annie Spencer, Dr. U. G. Bourne, Mrs.

Bertha Winston, Rev. F. J. Frey, Mrs. Bernard Harris,

Theodore W. Kess, Mrs. Lillian A. Lottier, Mrs. Charlotte

Mebane, defendant members of the Board of Managers of

Barrett School for Girls, Incorporated;

The Board of Managers of Boys’ Village, Incorporated,

defendant, and Dr. William E. Henry, Jr., President, Leon

ard W. Curtis, Mrs. Violet Hill Whyte, Charles E. Cornish,

Dr. Robert G. McGuire, W. Carles Mosley, Joseph H. Neal,

Garrett D. Rawlings, Clarence Anthony, defendant Board

Members of Boys’ Village, Incorporated;

The Board of Managers of Maryland Training School,

Incorporated, defendant, and Ralph L. Thomas, President,

Mrs. Dorothy Falconer, Paul E. Tignor, Dr. Earl T.

Hawkins, James J. Lacy, Jr., Dr. J. Morris Reese, Lawrason

Riggs, Lester B. Levy, Stuart Berger, defendant Members

E. 4

of the Board of Managers of Maryland Training School,

Incorporated;

The Board of Managers of Montrose School for Girls,

Incorporated, defendant, and Wallace Reidt, President,

Mrs. Martin J. Welsh, Jr., Harold Donnell, Mrs. Frank A.

Kaufman, Mrs. Lewis H. Runford, and Mrs. Herman Moser,

defendant, Members of the Board of Managers of Montrose

School for Girls, Incorporated, respectfully states to this

Honorable Court as follows:

1. This action is brought to redress the deprivation un

der color of law, statute, regulation, custom and usage of

the State of Maryland of the rights, privileges and immuni

ties secured by the constitution and laws of the United

States providing for the equal rights of the citizens of the

United States and of all persons within the jurisdiction of

the United States.

2. Plaintiff shows unto Your Honor that this is an action

for Declaratory Judgment and Injunctive Relief for the

purpose of determining a question in actual controversy

between the parties, to wit:

(a) Whether the policy, custom, usage, and practice of

defendants in systematically sending plaintiff Robert

Myers, minor, and other Negro males and females simi

larly situated exclusively to Boys’ Village and Barrett

School is denying, solely on account of race and color, to

plaintiff Myers and other Negroes similarly situated, rights

and privileges to rehabilitation training, without being

racially segregated in the use of said Training School and

school facilities which are furnished by the State of Mary

land for the rehabilitation of delinquent male and female

minors in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States?

(b) Whether the facilities furnished plaintiff and the

class he represents at Boy’s Village, Incorporated, and Bar

rett School for Girls, Incorporated, afford plaintiff and the

class he represents the equal protection of the law where

the facilities set apart for the plaintiff and the members

of the class he represents are physically inferior and psy

E. 5

chologically stigmatize plaintiff and the members of the

class he represents in a manner which makes it impossible

to obtain rehabilitation training equal to that afforded

white youths at Maryland Training School, Incorporated,

and Montrose School for Girls, Incorporated.

3. All parties to this action are citizens of the United

States and are domiciliaries of the State of Maryland.

4. Plaintiff alleges that this is a class action, and that

the rights here involved are of common and general inter

est to the members of the class represented by the plaintiff,

namely Negro citizens and residents of the State of Mary

land and of the United States who have been segregated

in the use of Rehabilitation Training facilities in the Train

ing Schools of Maryland and have been denied the use of

training school facilities equal to those offered to white

youths by the State of Maryland. Plaintiff avers that the

members of the class are so numerous as to make it imprac

tical to bring them all before the Court, and for this rea

son, plaintiff prosecutes this action in and on behalf of the

class which represents without specifically making all mem

bers thereof plaintiffs.

5. Plaintiff Mae Coleman is a citizen of the United States

and a resident and domiciliary of the State of Maryland.

Plaintiff Mae Coleman is over the age of 21 and is a tax

payer of the State of Maryland and of the United States.

Minor plaintiff Robert Myers is a citizen of the United

States and resident and domiciliary of the State of Mary

land; this action is brought in his behalf by his parent and

next friend, Mae Coleman. Plaintiff is classified as a Negro

under the laws of the State of Maryland.

6. Plaintiff alleges that defendants, Members of the

State Board of Public Welfare, Dr. Alvin Thalheimer, Cal

houn Bond, Mrs. Ralph O. Dulany, Sam Eig, Gen. Henry

C. Evans, Dr. Sanford V. Larkey, Howard Murphy, Herbert

R. O’Conor, Jr., and Mrs. John L. Sanford are empowered

under Article 88A, Sections 33 to 38 inclusive, of the Anno

tated Code of Maryland 1957 Edition as amended, to exer

cise supervision, direction and control over the corporate

E. 6

functions of all the other corporate defendants; that said

defendants, State Board of Public Welfare and Members of

said Board, through their rule making power, promulgate

rules and regulations establishing standards of care, poli

cies, rules of admission, conduct management, rules of

transfer, and discharge for the aforenamed Training

Schools, and that said defendant Board of Public Welfare

is charged with the responsibility of developing a program

within each training school, including provision for after

care supervision. Defendant Thomas J. S. Waxter is Direc

tor of the Department of Public Welfare and is Secretary

of defendant Board of Public Welfare; he is appointed pur

suant to the provision of Article 88A, Section 1 of the Anno

tated Code of Maryland by defendant Board of Public Wel

fare and devotes his whole time to directing the activities

of the State Department of Public Welfare.

Plaintiff avers that defendants Wallace Reidt, Mrs. Mar

tin J. Welsh, Mrs. Harold Donnell, Mrs. James H. Ferguson,

Dr. James Earp, Mrs. Frank A. Kaufman, Mrs. Lewis H.

Rumford, and Mrs. Herman Moser are members and con

stitute the Board of Managers of the Montrose School for

Girls, Incorporated; that defendant Board of Managers of

Montrose School is appointed by the Governor pursuant to

Article 88A and Section 34 of the Annotated Code of Mary

land, 1957 Edition as amended, and exercises its control

and supervision of the said Montrose School pursuant to

the provisions of Article 88A, Sections 33 to 36 inclusive

of the Annotated Code of Maryland, 1957 Edition as

amended.

Plaintiff avers that defendants Dr. William E. Henry,

Jr., Leonard W. Curlin, Mrs. Violet Hill Whyte, Charles E.

Cornish, Dr. Robert G. McGuire, W. Carles Mosley, Joseph

H. Neal, Garrett D. Rawlings and Clarence Anthony, con

stitute the Board of Managers of Boys’ Village, Incorpor

ated. Plaintiff alleges that defendant Board is appointed

by the Governor pursuant to Article 88A, Section 34 of the

Annotated Code of Maryland 1957 Edition, as amended and

exercises its control and supervision of the said Boys’ Vil

lage School pursuant to the provisions of Article 88A, Sec

E. 7

tions 33 to 36 inclusive of the 1957 Edition of the Annotated

Code of Maryland as amended.

Plaintiff avers that defendants Ralph L. Thomas, Mrs.

Dorothy Falconer, Paul E. Tignor, Dr. Earle T. Hawkins,

James L. Lacy, Dr. J. Morris Reese, Lawrason Riggs, Lester

B. Levy and Stuart Berger, constitute the Board of Man

agers of Maryland Training School, Incorporated. Plaintiff

alleges that defendant Board is appointed by Governor

pursuant to Article 88A, Section 34 of the Annotated Code

of Maryland 1957 Edition as amended and exercises its

supervision and control of the said Maryland Training

School pursuant to the provision of Article 88A, Sections

33 to 36 inclusive of the Annotated Code of Maryland 1957

Edition as amended.

Plaintiff alleges that Miss Anita R. Williams, Mrs. Annie

Spencer, Dr. U. G. Bourne, Mrs. Bertha Winston, Rev. F. J.

Frey, Mrs. Bernard Harris, Theodore W. Kess, Mrs. Lillian

A. Lottier and Mrs. Charlotte Mebane, constitute the Board

of Managers of Barrett School for Girls, Incorporated;

plaintiff alleges that defendant Board is appointed by the

Governor pursuant to Article 88A, Section 34 of the Anno

tated Code of Maryland 1957 Edition, as amended and exer

cises its control and supervision of the said Barrett School

pursuant to the provisions of Article 88A, Sections 33 to

36 inclusive, Annotated Code of Maryland, 1957 Edition as

amended; plaintiff alleges that the immediate control and

operation of the facilities, subject to this suit, is in the

hands of the defendants.

7. Plaintiff alleges that all defendants are being used in

their representative and official capacities.

8. Plaintiff alleges that the defendant Board of Managers

of Montrose School for Girls, Incorporated, and members

of said Board, pursuant to authority set forth in Article

27, Section 660 and Article 88A, Sections 33 to 36 inclusive,

of the Annotated Code of Maryland 1957 Edition, as

amended, have established and are maintaining and operat

ing Montrose School for Girls, Incorporated, exclusively

for the care and reformation of white girls. Plaintiff al

leges that the defendant Board of Managers of Boys’ Vil

E. 8

lage, Incorporated, and members of said Board, pursuant

to authority set forth in Article 27, Section 657, and Article

88A, Sections 33 to 36 inclusive of the Annotated Code of

Maryland 1957 Edition as amended, have established and

are maintaining and operating Boys’ Village, Incorporated,

exclusively for the care and reformation of Negro Boys.

Plaintiff alleges that the defendant Board of Managers of

Maryland Training School, Incorporated, and members of

said Board, pursuant to authority set forth in Article 27,

Section 659 and Article 88A, Sections 33 to 36 both inclusive

of the Annotated Code of Maryland 1957 Edition have

established and are maintaining and operating said Mary

land Training School exclusively for the care and reforma

tion of white boys. Plaintiff alleges that defendant Board

of Managers: of Barrett School for Girls, Incorporated, and

members of said Board, pursuant to authority set forth in

Article 27, Section 661 and Article 88A, Sections 33 to 36

inclusive of the Annotated Code of Maryland 1957 Edition

as amended, have established and are maintaining and

operating said Barrett School for Girls exclusively for the

care and reformation of Negro girls. Plaintiff alleges that

the defendant State Board of Public Welfare, the members

of said Board, and the defendant Thomas J. S. Waxter,

pursuant to authority set forth in Article 88A, Section 1

and Sections 33 to 36 inclusive of the Annotated Code of

Maryland, 1957 Edition as amended, have established and

are maintaining and operating reformation facilities for

delinquent minors at Barrett School for Negro girls ex

clusively, Boys’ Village for Negro boys, exclusively, Mont

rose School for Girls for white girls exclusively and Mary

land Training School for white boys exclusively, through

the supervision, direction and control of the other de

fendants.

9. The defendants herein are charged with the duty of

maintaining, operating and supervising Boys’ Village for

Boys, Maryland Training School, Incorporated, Montrose

School for Girls, Incorporated, and said Barrett School for

Girls, Incorporated, as a part of their supervisory control

and authority. These defendants have the exclusive power

to promulgate and endorse rules and regulations with re

spect to the use, availability and admission of minors to

each of these Training Schools through their respective

Boards.

10. Plaintiff further alleges that on or about April 10,

1959, one of his attorneys, Tucker R. Dearing, filed a peti

tion with the State Board of Public Welfare on behalf of

a number of citizens and tax payers demanding that de

fendants cease and desist the practice of racial segregation

in the Training Schools of Maryland. That on August 13,

1959, the said attorney was heard before the State Board of

Public Welfare at 301 W. Preston Street in the City of

Baltimore; that on or about September 22, 1959, the de

fendant, Thomas J. S. Waxter, Director of the State De

partment of Public Welfare and Secretary of said Board,

advised that the requested racial desegregation was de

nied and referred petitioners to the Legislature or to the

Court for any change in the racial segregation policy en

forced at the training schools.

11. Plaintiff alleges that on or about October 29, 1959,

he was found to be a delinquent in the Circuit Court of

Baltimore City Division for Juvenile Causes and that The

Honorable Charles E. Moylan, Judge of said Court, stated

that he would commit your plaintiff to a training school;

that your minor plaintiff and adult plaintiff, through their

attorney, Tucker R. Dearing, interposed a motion that your

minor plaintiff be not sent to Boys’ Village but that he be

sent to Maryland Training School which is reserved ex

clusively for white males; that said Judge Moylan held

said Motion Subcuria and detained your minor plaintiff

at Boys’ Village and that the said attorney took exception

to your Orator being retained at Boys’ Village, Incorpo

rated, a racially segregated school.

12. That Boys’ Village, Incorporated, is a racially segre

gated Training School by reason of which it cannot provide

your complainant with rehabilitation and training equal

to that provided at Maryland Training School for white

males, because Boys’ Village, Incorporated, is racially

segregated.

E. 10

13. That Article 27 of the Annotated Code of Maryland,

1957 Edition, as amended, Section 659 requiring white male

youths to be sent exclusively to the Maryland Training

School, Incorporated, Section 660 requiring white female

youths to be sent exclusively to Montrose School for Girls,

Incorporated, Section 657 requiring Negro male youths to

be exclusively sent to Boys’ Village, Incorporated, and

Section 661 requiring Negro female minors to be sent ex

clusively to Barrett School for Girls, Incorporated, are

all unconstitutional insofar as said statutes deny to your

plaintiff and other members of the class which he repre

sents their right to enjoy non-racially segregated training

school facilities as required by the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States,

14. That the defendants and each of them in concert

have systematically racially segregated them and other

youths in the training schools of Maryland.

15. Plaintiff alleges that the Circuit Court of Baltimore

City, Division for Juvenile Causes, and the Circuit Courts

in each County having jurisdiction for juvenile causes,

have automatically followed the racial pattern of segrega

tion set forth in aforesaid Sections of Article 27 of the Anno

tated Code of Maryland 1957 Edition as amended; that no

white youth in the history of the State of Maryland has

ever been committed to either of the training schools

reserved exclusively for Negro youths; it is further al

leged that never in the history of the State of Maryland

has any Negro youth ever been committed to either of

the training schools reserved exclusively for white youths,

16. Plaintiff alleges that the Order of the Circuit Court

of Baltimore City, Division for Juvenile Causes, which

detains him at Boys’ Village, Incorporated, a racially segre

gated training school while awaiting a determination of

this controversy has deprived and will continue to deprive

him of his Constitutional rights guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

17. That the Courts of Maryland having jurisdiction in

Juvenile Causes and the defendants by systematically ra

E. 11

cially segregating him and other youths who are members

of the class represented by the plaintiff, namely, youths

who have been detained or committed to the training

schools of Maryland, have denied to him and other youths,

members of the class represented by the Plaintiff, due

process of law as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the Constitution of the United States.

18. Plaintiff alleges that these separate training and

reformation schools constitute an inequality, in that

colored persons are completely excluded from Maryland

Training School and Montrose School for Girls, Incorpo

rated, and that Boys’ Village and Barrett School for Girls,

Incorporated, are located in different localities, thus con

stituting physical and psychological inequality under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States; that the policy, custom and usage of defendants,

and each of them, of providing, maintaining and operating

out of public funds said training schools on a racially

segregated basis, and failing to admit Negro youths to all

training facilities, wholly and solely on account of their

race and color, is unlawful and constitutes a denial of their

rights to the equal protection of the laws and of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

19. That plaintiff and those similarly situated and af

fected, on whose behalf this suit is brought are suffering

and will suffer continuing irreparable injury, by reason of

the acts herein complained of; plaintiff avers that he has

no plain, adequate or complete remedy to redress the

wrongs and illegal acts herein complained of other than

this suit for a declaration of rights and injunction; that,

any other remedy to which plaintiff and those similarly

situated could be remitted would be attended by such

uncertainties as to deny substantial relief, would involve

multiplicity of suits, cause further irreparable injury and

occasion damage, vexation and inconvenience, not only to

plaintiff and those similarly situated, but to the defend

ants as governmental agencies.

E. 12

W herefore, Plaintiff prays:

1. That proper process issue and that this cause be ad

vanced upon the Docket.

2. That the Court adjudge, decree and declare the rights

and legal relations of the parties to the subject matter

here in controversy in order that such declaration shall

have the force and effect of a final order or decree.

3. That the Court enter a Declaratory Judgment and de

clare that any rule, policy, custom, practice and usage

pursuant to which said defendants or any of them, their

lessees, agents and successors in office deny to plaintiff

and the members of the class he represents, commitment,

admission or transfer to any of the schools of reformation

operated and maintained by the defendants on account of

race and color contravenes the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.

4. That Sections 657, 658, 660 and 661 of Article 27

of the Annotated Code of Maryland, 1957 Edition as

amended, are unconstitutional in that the State of Mary

land is without authority to promulgate the statute because

it enforces a classification based upon race and color which

is violative of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States.

5. That this Court issue a permanent injunction forever

restraining the defendants and each, of them, their lessees,

agents and successors in office from denying to the plain

tiff and other Negro youths, solely on account of race and

color, commitment, admission and transfer to any train

ing school established, operated and maintained by the

State of Maryland.

Dearing and Toadvine,

Juanita Jackson Mitchell,

Thurgood Marshall,

Jack Greenberg,

Attorneys for Plaintiff.

E. 13

DEMURRER AND ANSWER

To the Honorable, the Judge of said Court:

The Defendants, State Board of Public Welfare, et al.,

by C. Ferdinand Sybert, Attorney General, and Robert C.

Murphy, Special Assistant Attorney General, demur and

answer to the Bill of Complaint filed against them in the

above entitled cause, and for grounds of demurrer respect

fully say:

1. That the Bill of Complaint is bad in substance and

insufficient as a matter of law to state a cause of action in

that Sections 657 and 659-661 of Article 27, Annotated

Code of Maryland (1957 Ed.), setting forth the legislative

policy of conducting racially segregated correctional train

ing institutions for the care and reformation of delinquent

minors committed thereto under the laws of Maryland is

a valid exercise of the police power of the State and, as

such, does not deprive the Plaintiff of any rights, privileges

or immunities secured, protected or guaranteed by the

Constitution and laws of the United States or of the State

of Maryland;

A nd, answering said Bill of Complaint, Defendants re

spectfully represent:

1. That they deny the allegations in paragraph 1 of said

Bill of Complaint.

2. That they are not required to answer the allegations

and matters contained in paragraph 2 of said Bill.

3. That they admit the allegations in paragraph 3 of

said Bill.

4. That they are without knowledge and therefore un

able either to admit or deny the allegations in paragraph

4 of said Bill.

5. That they admit the allegations contained in para

graph 5 of said Bill.

6. Answering paragraph 6 of said Bill, they admit that

pursuant to the provisions of Sections 33-38, Article 88A,

Annotated Code of Maryland (1957 Ed.), the State De

partment of Public Welfare is empowered to exercise super

E. 14

vision, direction and control over the State correctional

training institutions for delinquent minors, namely: Mary

land Training School for Boys, Boys’ Village, Montrose

School for Girls and Barrett School for Girls; that each

of these institutions is a public agency of the State of Mary

land but are not otherwise incorporated; that the State

Department of Public Welfare is vested with power and

authority to promulgate rules and regulations establishing

standards of care, policies of admission, transfer and dis

charge, and are further empowered to order such changes

in the policies, conduct or management of said correctional

training institutions as to it may seem desirable; that said

Department is empowered to develop a program within

each of the aforesaid correctional training institutions, in

cluding provision for after-care supervision.

Further answering, they admit that the defendant Boards

of Managers of the aforesaid correctional institutions are

appointed by the Governor, and each is authorized and is

responsible for the general management of such institu

tions, subject, however, as aforesaid, to the supervision,

direction and control of the State Department of Public

Welfare.

7. That they admit the allegations in paragraph 7 of

said Bill.

8. Answering paragraph 8 of said Bill of Complaint,

they admit that each of the aforesaid correctional training

institutions is operated and maintained on a racially segre

gated basis for the care and reformation of delinquent

minors, but deny the implication implicit in said paragraph

that the respective Boards of Managers of such institutions

or the State Department of Public Welfare initiated the

establishment thereof, the establishment of such institu

tions being solely pursuant to statutory requirement and

direction.

Further answering, they say that such schools being cor

rectional institutions of reformation, they are primarily

intended as places to separate erring minors from the cor

rupting influences of improper circumstances and asso

ciates.

E. 15

9. Answering paragraph 9 of said Bill of Complaint,

they admit that they are charged in combination with re

sponsibility for the management phases of the said correc

tional training institutions, but deny that they have any

power, either individually or in combination, to promul

gate and enforce rules and regulations at variance with the

statutory policy of the State of Maryland requiring the

conduct and operation of such correctional training insti

tutions on a racially segregated basis.

10. That they admit the allegations in paragraph 10 of

said Bill of Complaint.

11. That they are without knowledge and therefore are

unable either to admit or deny the allegations in paragraph

11 of said Bill.

12. Answering paragraph 12 of said Bill of Complaint,

they admit that Boys’ Village is a racially correctional in

stitution for delinquent minors, but deny all other allega

tions contained in said paragraph.

13. That they are not required to answer paragraph 13

of said Bill as the allegations therein contained present no

new matters of fact, but are confined solely to drawing

conclusions of law from the facts alleged.

14. That they deny the allegations in paragraph 14 of

said Bill of Complaint and, further answering, say that op

eration of the State’s correctional training institutions on

a racially segregated basis is pursuant to statutory require

ment, as aforesaid.

15. That they are without knowledge and therefore un

able either to admit or deny the allegations contained in

paragraph 15 of said Bill of Complaint.

16. That they are not required to answer the allegations

and matters in paragraphs 16 and 17 of said Bill of Com

plaint since the same set forth conclusions of law.

17. Answering paragraph 18 of said Bill of Complaint,

they admit that said correctional training institutions are

conducted and operated on a racially segregated basis pur

E. 16

suant to statutory requirement, but deny all other allega

tions contained in said paragraph.

18. That they are not required to answer the allegations

in paragraph 19 of said Bill of Complaint.

W herefore, having fully answered said Bill of Complaint,

the Defendants pray that the same be dismissed with costs.

C. Ferdinand Sybert..

Attorney General,

Robert C. Murphy,

Spec. Asst. Attorney General,

Attorneys for Defendants.

PROCEEDINGS

(T. 5-179):

(Mrs. Mitchell) May it please the Court, at this time,

by agreement of the State, we wish to stipulate and enter

into the record as Plaintiff’s Exhibit No. 1 the file of the

action in the Juvenile Court of Baltimore City beginning

as of October 7, 1959, Docket No. 65544, in the matter of

Robert Myers, Minor, 13 years of age, and further, may it

please the Court, by agreement of counsel for the State, we

wish to stipulate at this time as Plaintiff’s Exhibit 2-A a

copy of a letter dated October 21, 1955 addressed to the

Honorable C. Ferdinand Sybert, Attorney General of

Maryland, from Mr. W. Thomas Kemp, Jr., Chairman of

the State Board of Public Welfare.

PLAINTIFF’S EXHIBIT 2-A

“Hon. C. Ferdinand Sybert

Attorney General of Maryland

1201 Mathieson Building

Baltimore 2, Maryland

“Dear General Sybert:

“Under Section 32 of Article 88A of the Annotated Code

of Maryland, the Maryland Training School for Boys, the

Montrose School for Girls, Boys’ Village of Maryland, and

the Barrett School for Girls exercise their corporate func

E. 17

tions under the supervision, direction and control of the

State Department of Public Welfare.

“Two of the schools are for the care of boys and two for

girls, one of each for white and one of each for negro.

(Sections 742 to 748, inclusive, of Article 27 of the Annotated

Code of Maryland.) The school for Negro girls (Barrett

School for Girls) is an expensive operation because of the,

small number of children in custody at any one time. The

''State Department of Public Welfare has recommended to

the State Planning Commission that the Montrose School

for Girls be enlarged to permit caring for both white and

Negro girls, provided any necessary legislation authorizing

this be enacted. The girls at Barrett School for Girls would

be transferred to Montrose, and Barrett would be either

closed or used for some other purpose. This recommenda

tion was predicated on the belief that substantial savings

to the State would result therefrom.

“Caring for Negro girls at Montrose rather than at Bar

rett raises the question as to what, if any, effect the recent

decisions of the United States Supreme Court, in the pub

lic school cases, have with respect to the Maryland State

training schools. Specifically, do the Supreme Court cases

invalidate the Maryland statutory requirement that the

Montrose School for Girls limit its care to white girls duly

committed to the school under the laws of Maryland?

“Your opinion on these questions would be helpful to

the State Department of Public Welfare and to the training

schools in planning for the future.

“Respectfully yours,

“W. Thomas K emp, Jr., Chairman

“State Board of Public Welfare

“WTK, Jr.: F.

“cc: Mr. Murphy

“cc: Mr. Hunt.”

E. 18

(Mrs. Mitchell) And as Plaintiff’s Exhibit 2-B a letter

addressed to W. Thomas Kemp, Jr., Chairman of the Board

of Public Welfare under date of January 11, 1956 from

C. Ferdinand Sybert, Attorney General, and Norman P.

Ramsey, Deputy Attorney General.

PLAINTIFF’S EXHIBIT 2-B

January 11, 1956

“W. Thomas Kemp, Jr., Esq.

Chairman — Board of Public Welfare

120 West Redwood Street

Baltimore 1, Maryland

“Dear Mr. Kemp:

“You state in your recent letter that the State Depart

ment of Public Welfare has recommended to the State

Planning Commission that Montrose School for Girls, which

at present cares for white girls, be enlarged to permit care

of both white and Negro girls. The Board of Welfare pro

poses to have the girls at Barrett School, which at present

cares for colored girls, transferred to Montrose, so that

Barrett will be available for some other use. In the event

Barrett is not required for other Department of Public

Welfare use, it would be closed. You state that in the opin

ion of the Department, substantial savings will result to

the State from this consolidation of the two schools.

“You have inquired whether the legislative designation

of these institutions as schools for white and colored girls

prevents such a consolidation, in light of the decisions of

the United States Supreme Court in the public education

cases. Specifically, you inquire whether the Supreme Court

decisions have the effect of invalidating the Maryland

statutory provisions which confine Montrose School to the

care of white girls and Barrett to the care of colored girls.

Since the training schools for boys are likewise set up on

a segregated basis your inquiry, although directed to the

girls’ schools, is of general applicability.

“The statutory provisions with respect to the various

Houses of Reformation in the State of Maryland are found

E. 19

in Article 27 of the Annotated Code of Maryland (1951 Ed.

and 1955 Supp.). The particular institutions under the

Department of Public Welfare are: Boys Village (for col

ored boys), Maryland Training School (for white boys),

Montrose School (for white girls), and Barrett School (for

colored girls). Section 743 of Article 27 (1955 Supp.) deals

with Boys Village and reads as follows:

“ ‘There shall be established in the State an insti

tution to be known as Boys’ Village of Maryland. Said

institution is hereby declared to be a public agency

of said State for the care and reformation of colored

male minors committed or transferred to its care under

the laws of this State. The appointment and powers of

the board of managers of said institution shall be gov

erned by article 88A, as 32 to 35, both inclusive, of the

Code.’ (Emphasis supplied.)

“Maryland Training School for Boys is dealt with in

Section 746, which reads, in part, as follows:

“ ‘From and after the acquisition by the State of

Maryland from the Maryland School for Boys, a cor

poration of this State, of the property heretofore held,

conducted and managed by said corporation as a re

formatory institution for the care and training of white

male minors committed thereto under the provisions

of the laws of this State, the same shall continue under

the name of the Maryland Training School for Boys

to be conducted as a public agency of this State for

the care and reformation of white male minors now

committed thereto, and who may hereafter be com

mitted thereto under the laws of this State. * * *’ (Em

phasis supplied.)

“Montrose School for Girls is treated in Section 747,

which reads as follows:

“ ‘From and after the acquisition by the State of

Maryland of the property of the Maryland Industrial

School for Girls the same shall continue as a reforma

tory under the name of the Montrose School for Girls

to be conducted as a public agency of this State for

E. 20

the care and reformation of white female minors now

committed thereto, and who may hereafter be com

mitted thereto under the laws of this State. The ap

pointment and powers of the board of managers of

said institution shall be governed by article 88A, §§32

to 35, both inclusive, of the Code.’ (Emphasis sup

plied. )

“Barrett School for Girls is covered by Section 748,

which reads, in part, as follows:

“ ‘There shall be established in this State, an institu

tion to be known as the Barrett School for Girls. The

said institution is hereby declared to be a public agency

of this State for the care and reformation of colored

female minors committed or transferred to its care

under the laws of this State. * * *’ (Emphasis sup

plied. )

“Examination of these statutes shows that in each in

stance the Code specifies whether colored or white are to

be received by the institutions.

“By the provisions of Article 88A of the Annotated Code

of Maryland (1951 Ed.), Sections 3 and 32, supervision,

direction and control of the institutions above mentioned

are committed to the Department of Public Welfare.

“The history and legal effect of the decisions of the

Supreme Court in the Public Education cases were con

sidered in our opinion of June 20, 1955, addressed to Dr.

Thomas G. Pullen, Jr., State Superintendent of Schools.

We held in that opinion that all constitutional and legisla

tive provisions of this State which require segregation in

the public schools are unconstitutional, and hence must be

treated as nullities. We stated that the law laid down by

the Supreme Court with respect to public education is

clear, and that differences of mechanics of relief did not

in any way limit the present existing legal compulsion on

the school authorities to make a ‘prompt and reasonable’

start toward the ultimate elimination of racial discrimina

tion in public education.

E. 21

“Since the General Assembly specified in the statutes

creating the various training schools whether white or

colored are to be there received, your present inquiry

raises the issue of the constitutional validity of each of

the several Acts of the General Assembly. Before pro

ceeding to a detailed consideration of the problem posed,

some statement of the basic principles which must guide

our actions in the matter seems appropriate.

“The fundamental concept upon which the Federal Gov

ernment and that of the States of the United States is

based is that our State and Federal Governments depend

for their existence upon, the will of the people expressed

through Constitutions duly adopted. The basic theory of

our State and Federal Constitutions is that the powers

given by the people to the governing body break down into

a tripartite division. The three coequal branches, execu

tive, legislative and judicial, serve the people, and are

themselves restrained from despotic or arbitrary exercise

of power by the internal system, of checks and balances.

This principle is so well established as to require little

discussion.

“The judicial branch of the Government of the United

States and of the State of Maryland is, under our system,

the interpreter of the Federal and State Constitutions.

The existence in the judiciary of this important power

and duty is one of the most vital of the internal system

of checks and balances protecting our people against the

arbitrary exercise of executive or legislative authority.

The landmark decision of Marbury v. Madison, 1 Crunch

(U. S.) 137, 2 L.Ed. 60, stands as a monument to the judi

cial recognition of this vital principle. Inherent in. the

power to interpret the Constitution of the United States

and the various States, which is vested in the judiciary,

is the power to pass on the constitutional validity of laws

passed by the legislative branch of the Government.

“It would be contrary to the theory of our government

to permit the Executive Department to arrogate to itself

this purely judicial power. Attempts to invade this ex

clusively judicial power have been resisted by the courts

E. 22

in the past. This is as it should be. Even the theory that

the executive’s oath to support the Constitution entitles

such an officer to decide questions of the constitutional

validity of statutes passed by the legislative branch has

been rejected. 11 Am. Jur. Constitutional Law, Section

87, pp. 712-713; 11 Am. Jur. Constitutional Law, Section

205, p. 907.

“As a corollary to the exclusive right of the judiciary

to determine constitutional questions, and in order prop

erly to protect the Legislature and its prerogatives as

against executive action nullifying legislative will, we in

dulge in the presumption that every law found on the

statute books is constitutional until declared otherwise by

the courts.

“The Maryland Constitution expressly recognizes

the doctrine of separation of powers in Article 8 of the

Declaration of Rights, which provides:

“ ‘That the Legislative, Executive and Judicial pow

ers of Government ought to be forever separate and

distinct from each other; and no person exercising

the functions of one of said Departments shall assume

or discharge the duties of any other.’

Substantially this same provision has been found in our

Constitution since the earliest days of Maryland. Unlike

the Federal Constitution, where separation of powers must

be found by reading the entire document, Maryland has

always so provided. Niles on Maryland Constitutional Law,

at p. 19, in commenting on this provision, made the fol

lowing statement:

“ ‘The language of our Maryland Declaration of

Rights * * * is clear and explicit; and our courts have

been alert to oppose even the first steps toward usurpa

tion by one department of the powers or duties of

either of the others * * *.’

“Our Maryland view was clearly laid down by Judge

Earle in the case of Crane v. Maginnis, 1 G. & J. 463, de

E. 23

cided in 1829, where the court made the following com

ment :

“ ‘The Constitution of this State composed of the

Declaration of Rights, and Form of Government, is the

immediate work of the people in their sovereign

capacity, and contains standing evidences of their per

manent will. It portions out supreme power, and as

signs it to different departments, prescribing to each the

authority it may exercise, and specifying that, from

the exercise of which it must abstain. * * * When they

transcend defined limits their acts are unauthorized

and being without warrant, are necessarily to be

viewed as nullities.’

The court then went on to point out that the judicial power

of the court to interpret the Constitution is the check upon

legislative excess or legislative encroachment upon the

rights of citizens or of coequal branches.

“The office of Attorney General is created by Article V

of the Constitution, Sections 1 through 6. The Attorney

General is head of the Department of Law, one of the

executive and administrative departments of this State.

Article 41, Sections 2 and 171, Annotated Code of Mary

land. By Article 32A, Sections 1 through 12, the general

powers and duties of the Attorney General are set out.

“The place of the Attorney General in the constitutional

structure of our State is such that this office must be cir

cumspect that, as an arm of the executive, it does not

encroach upon duties and prerogatives of the judicial or

legislative departments. Chancellor Bland, in The Chan

cellor’s Case, 1 Bland 595, 672, pointed out the obligation of

the various departments one to another, when he said:

“ ‘The Declaration of Rights declares “that the

legislative, executive, and judicial powers of govern

ment ought to be forever separate and distinct from

each other.” This division and separation is the pe

culiar characteristic and great excellence of our gov

ernment. It is the grand bulwark of all our rights,

E, 24

and every citizen has the deepest interest in its most

sacred preservation. Each of these several departments

should be kept, and should feel it to be its highest

honor, to keep strictly within the constitutional

boundaries assigned to it. The Legislature should not

encroach upon the judiciary, nor upon the executive,

nor should either of those departments trench upon

each other or upon the legislative.’

“Historically, the Attorneys General of Maryland have

observed the injunction not to encroach upon judicial or

legislative prerogatives. In the exercise of the Attorney

General’s duty to act as advisor to the Governor, this office

has rendered opinions to the Governor as to the constitu

tional validity of Acts pending for signature before the

Governor. 20 Opinions of the Attorney General, 268; 7

Opinions of the Attorney General, 239; 21 Opinions of the

Attorney General, 272; 36 Opinions of the Attorney Gen

eral, 129; 38 Opinions of the Attorney General, 150. Other

opinions may be cited and the list here contained is not

intended to be exhaustive. As to existing laws, however,

after passage by the Legislature, the Attorney General

should exercise the care to observe the division of powers.

This office must scrupulously avoid invasion of the judi

ciary’s powers and duties. We will always seek to give

just and proper effect to every decision of the courts of

this State and of the Supreme Court of the United States

on constitutional matters. However, we are constrained

to denounce an existing law as violative of State or Federal

constitutional guaranties only in those situations where a

fair interpretation of a court decision indicates a chal

lenged law is constitutionally invalid. In the absence of

clear indication that a decision of our courts or of the

Supreme Court of the United States covers and invalidates

a given statute, we must, under our constitutional re

straints, withhold condemnation of the law.

“The inquiry then must be whether this is such a case.

In our opinion, it is not a clear case within any decision

of the United States Supreme Court or of the courts of

this State, such as would warrant our expressing a view

E. 25

of the invalidity of the training school laws unless the

matter be resolved by proper action of our judiciary or our

Legislature. It is not our function to make policy in this

field.

“The unique position occupied by the training schools

here under discussion is evident from the fact that they

are primarily intended as places to separate erring minors

from the corrupting influence of improper circumstances

and associates. Basically, the State is removing the indi

viduals there confined from society for the protection and

welfare of the individual. The theory that every minor

should receive education as part of the process of ‘reform’

introduces the element of doubt. But for this aspect of

training schools, they would be purely correctional.

“Very many of the past discussions of training schools,

found in the reported Maryland cases and in the opinions

of the Attorneys General, indicate the nature of the prob

lem. For example, in an opinion of Attorney General

Robinson, reported in 9 Opinions of the Attorney General,

168, in discussing the Maryland Training School for Boys,

the Attorney General said:

“ ‘As its name and position among the State Depart

ments would seem to imply, the Maryland Training

School for Boys was intended for the education of

male minors along economical and practical lines.’

In the same opinion, Attorney General Robinson made

the following comment:

* * * it (the Maryland Training School) was

established primarily for the care and reformation of

such white male minors, who, through misfortune,

environment or the effects of crime, are, in the opinion

of the Justices of the Peace or Courts of the State or

County, better off within its walls.’ (Emphasis sup

plied. )

Again, at page 170, the Attorney General commented:

“ ‘I realize that your institution was not intended

to be a place of punishment. It was organized as a

place of reformation.’ (Emphasis supplied.)

E, 26

“The Court of Appeals, in Baker v. State, 205 Md. 42, had

before it the question of whether the Escape provisions

of the criminal law (Article 27, Section 164, 1951 Ed. of

the Code) applied to Boys Village. The appellants con

tended Boys Village was not within the criminal law

Escape statute. Judge Henderson, at page 45, said:

“ ‘The appellants further contend that Boys Village

is not a “reformatory * * * or other place of confine

ment” within the meaning of Section 164. This argu

ment overlooks the fact that the statute creating Boys

Village states that it is a place for “care and reforma

tion” .’

“The Court held that Boys Village was a ‘reformatory’

within the meaning of the statute.

“Further lack of clarity is indicated by the fact that the

statutes creating the institutions in question are codified in

Article 27 of our Code. This Article is, of course, the

criminal law Article. However, for many years, these

institutions exercised their powers under the supervision

of the State Superintendent of Schools; the instructors

have been included in the Teachers Retirement System,

and they have to a degree been considered ‘educational in

stitutions’. They have not, however, in our opinion been

included within the term ‘public education’ in the sense

that that term has been used in the Supreme Court

opinions.

“As heretofore set out, one of the ways in which the

various institutions seeks to reform the inmates is by edu

cation. However, the distinguishing characteristic of

such institutions, to our mind, is that inmates are there

under legal compulsion and are denied the privilege of

leaving the school. The inmates are, in other words, con

fined to these institutions. This is a situation different from

that which was before the Supreme Court in the Public

School cases, in that educational equality was the problem

before the court. Here, desegregation of the institution,

contrary to express legislative intent evidenced by the

statutes creating the institutions, could have the effect of

E. 27

enforcing social as well as educational association among

the inmates- for twenty-four hours a day.

“We are aware that compulsory school attendance laws

make it obligatory upon parents who wish their children

to attend the public schools to accept and abide by a system

of public education from which racial discrimination has

been eliminated, consistent with our opinion of June 20,

1955, interpreting the application of the Supreme Court

decisions to the Maryland public education scene. We be

lieve it is important, however, to consider the freedom of

choice which inheres in parents under our compulsory

school attendance law. Section 223 of Article 77 of the

Code (Public Education Article), provides, in part as fol

lows:

“ ‘Every child residing in Baltimore City and in any

county in the State between 7 and 16 years of age

shall attend some day school regularly as defined in

Section 226 of this Article * * * unless it can be shown

that the child is elsewhere receiving regularly thorough

instruction during said period in the studies usually

taught in said public schools to children of the same

age * * *.’ (Emphasis supplied.)

“It will be noted that parents are free to demonstrate

that a child is receiving regular instruction in private

schools. This retains the necessary element of freedom of

choice in the field of public education and is consistent

with the social views of the citizens of the State of Mary

land that the elimination of discrimination in the fields of

public action should not carry over into and destroy the

historic view of our people that separation of the races

in social matters is the accepted norm and has been the

established policy and practice through the years. See

Williams v. Zimmerman, 172 Md. 563, 567, 192 A. 353, 355.

“One further point is worthy of mention. Basically the

argument in the public education cases turned on the issue

of whether to retain or reject the ‘separate but equal’

doctrine laid down in Ple.ssy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 41

L. Ed. 256. We are not aware of any instance in which the

E. 28

doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has been applied to the

field of correctional institutions such as those here under

discussion. Even though the effect of the public education

cases is to abolish the doctrine in all fields to which it was

heretofore applicable (which has been questioned), we do

not believe it can be fairly said the effect would be carried

over into still other fields of activity never heretofore in

cluded within the doctrine.

“Judge Hammond, while Attorney General, had occasion

to write an extended opinion on the constitutional validity

of a personal property tax on ‘stock in business’. 37 Opin

ions of the Attorney General 424 at 439. After he had con

cluded that the courts of our State would probably hold

the Act valid and constitutional, even though he had some

doubt in his mind as to its constitutional validity, he made

the following comment, which we believe exactly appro

priate in the instant case:

“ ‘* * * Our doubts are not so strong as to warrant

this office taking the extraordinary action of advising

the State Tax Commission to ignore an Act of the

General Assembly.’

In our opinion, the present case is not such a clear one as

to warrant our taking the ‘extraordinary action’ of advising

your Department to ignore the express will of the Legisla

ture.

“Very truly yours,

“s/ C. Ferdinand Sybert,

Attorney General,

“s / Norman P. Ram sey ,

Deputy Attorney General.

CFS: MH

NPR”

(Mrs. Mitchell) A letter addressed to Thomas J. S.

Waxter, Director, State Department of Public Welfare,

under date of June 24, 1957, signed by Clayton A. Dietrich,

Assistant Attorney General, as Plaintiff’s Exhibit 2-C.

E. 29

PLAINTIFF’S EXHIBIT 2-C

“June 24,1957

“Hon. Thomas J. S. Waxter, Director

State Dept, of Public Welfare

120 W. Redwood Street

Baltimore 1, Md.

“Dear Judge Waxter:

“This will acknowledge your letter to this office dated

June 21, 1957, stating that you have received informal

advice from the Circuit Court of Baltimore City for

Juvenile Causes that they expected petitions to be filed

requesting that a colored delinquent be sent to a training

school designated for white.

“After receiving your telephone advice on Friday after

noon to this effect, I conferred with Mr. McDermott con

cerning the suggested procedure of having the Department

intervene on a voluntary basis, I told Mr. McDermott

that I did not think it was proper for us to enter the pro

ceeding as volunteers. He tended to agree with me and

suggested that I confer with Judge Moylan.

“I conferred with Judge Moylan and Mr. McDermott

this morning in chambers. After advising Judge Moylan

that I had serious doubts as to the propriety and juris

diction of the court in the matter, I suggested that in any

event the movants be required to file a formal petition,

and that the Department and the school be joined as

respondents under a show cause order. In light of the

importance of the question and the constitutional prob

lem involved, I do not believe that the matter can be

handled in the somewhat summary and informal manner

I originally contemplated. Judge Moylan has the matter

under advisement and is aware of the fact that I will be

out of town the balance of the week.

“I shall keep you advised of developments.

“Very truly yours,

“s / Clayton A. Dietrich,

Asst. Attorney General.CAD:MH”

E, 30

(Mrs, Mitchell) And as Plaintiff’s Exhibit 2-D a copy

of a letter under date of September 10, 1959 addressed

to Mr. Thomas J. S. Waxter, Director, State Department

of Public Welfare, signed by C. Ferdinand Sybert, At

torney General and Robert C. Murphy, Special Assistant

Attorney General.

PLAINTIFF’S EXHIBIT 2-D

“September 10, 1959

“Mr. Thomas J. S. Waxter, Director

State Department of Public Welfare

State Office Building

301 West Preston Street

Baltimore 1, Maryland

“Dear Mr. Waxter:

“Receipt is acknowledged of your recent letter request

ing our present view as to the constitutionality of Sections

657 and 659-661 of Article 27, Annotated Code of Maryland

(1957 Edition).

“These statutes relate to the State training schools,

namely, Boys’ Village, Maryland Training School, Montrose

School, and Barrett School, and provide that such insti

tutions are public agencies for the care and reformation

of minors committed thereto under the laws of this State.

The statutes further provide that Maryland Training

School be for white boys, Boys’ Village for colored boys,

Montrose School for white girls, and Barrett School for

colored girls.

“The precise constitutional issue presented in your letter

is whether the legislative mandate requiring operation of

Maryland’s training schools on a racially segregated basis

violates the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution.

“By opinion dated January 11, 1956 (41 Opinions of the

Attorney General 120) we considered this same question

in light of judicial decisions as of that time, particularly the

E. 31

decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 493 (1954), hold

ing segregation of children in public schools solely on the

basis of race to be unconstitutional. We there held, in

pertinent substance, that a presumption of constitutionality

attaches to each act of the Legislature and that the Office

of Attorney General, as an arm of the executive branch

of our government, was constrained to denounce an exist

ing law as violative of state or federal constitutional

guarantees only in those situations where a fair inter

pretation of a court decision indicates that a challenged

law in constitutionally invalid. We then noted that the

training schools were primarily intended as places to

separate erring minors from the corrupting influence of

improper circumstances and associates and that these in

stitutions were both legislatively and judicially declared

to be reformatories. While we fully recognized that edu

cation was a part of the process of reforming the indi

viduals committed to the training schools, and that to a

degree the institutions have been considered as educational

institutions, it was our view that they did not fall within

the purview of the term ‘public education’ in the sense

that such term was used by the Supreme Court in the

Brown case. Specifically we said:

. . the distinguishing characteristic of such institu

tions (training schools), to our mind, is that inmates

are there under legal compulsion and are denied the

privilege of leaving the school. The inmates are, in

other words, confined to these institutions. This is a

situation different from that which was before the

Supreme Court in the Public School cases, in that

educational equality was the problem before the court.

Here, desegregation of the institution, contrary to ex

press legislative intent evidenced by the statutes

creating the institutions, could have the effect of en

forcing social as well as educational association among

the inmates for twenty-four hours a day.’

‘One further point is worthy of mention. Basically

the argument in the public education cases turned on

E. 32

the issue of whether to retain or reject the ‘separate

but equal’ doctrine laid down in Plessy v. Ferguson,

163 U.S. 537, 41 L. Ed. 256. We are not aware of any

instance in which the doctrine of “separate but equal”

has been applied to the field of correctional institu

tions such as those here under discussion. Even

though the effect of the public education cases is to

abolish the doctrine in all fields to which it was here

tofore applicable (which has been questioned), we do

not believe it can be fairly said the effect would be

carried over into still other fields of activity never

heretofore included within the doctrine.”

“We have found nothing in the present law as it has

developed since our opinion of January 11, 1956, which is

at variance with our earlier views, and we consequently

reaffirm the same, restating herein our ultimate conclusion

in that opinion as follows:

“ . the present case is not such a clear one as to

warrant our taking the extraordinary action of ad

vising your Department to ignore the express will of

the Legislature.’

“We think that the opinion of the United States District

Court in Nichols v. McGee, 169 F. Supp. 721 (N.D., Calif.,

1959) bears sufficient relationship to the present question

to include a reference thereto in this opinion. In that case

the petitioner, an inmate of a State prison, contended

that his constitutional guarantee of equal protection of

the law was denied him in that he was required to join

an exclusively Negro line formation when proceeding to

his assigned cellblock for daily lockup and to the prison

dining hall, and that he was required to eat in a walled-off

and exclusively Negro compartment in the prison dining

hall. He contended that such systematic segregation

caused him a loss of self-respect, thereby making it diffi

cult for him to effect the same degree of rehabilitation

possible for unsegregated prisoners of other races. He

relied principally on Brown v. Board of Education, supra.

The Court there held: ‘By no parity of reasoning can

E. 33

the rationale of Brown v. Board of Education be extended

to state penal institutions where the inmates, and their

control, pose difficulties not found in educational systems.

Federal courts have long been loath to interfere in the

administration of state prisons’.

“Very truly yours,

/ s / C. Ferdinand Sybert,

C. Ferdinand Sybert,

Attorney General,

/ s / Robert C. Murphy,

Robert C. Murphy,

Spec. Asst. Attorney General.

CFS

RCM/k”

(Mrs. Mitchell) Now, may it please the Court, in a brief

opening statement, the petitioners in this proceeding advise

you that upon hearing of the petition in the Juvenile

Court, this Court stated he would commit the boy to a

training school.

At that time, counsel for Robert Myers entered a motion

that he be sent to the Maryland Training School, con

tending that Roys’ Village was a segregated school which

violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States,

We will show that the mother of this boy, prior to com

ing to the city of Baltimore, had this boy attend an inte

grated and public school in Baltimore County and wanted

him to have an integrated rehabilitation training.

We will show further that the mother indicated that the

distance to Boys’ Village was prohibitive and that her

boy, while attending an integrated public school in the

County, had never been in trouble and she felt that his

rehabilitation would be more effective under integrated

circumstances.

E. 34

Whereupon, the Juvenile Court of Baltimore City struck

out the Order of Commitment and ordered said Robert

Myers detained at the customary place in the State of

Maryland for the detention of Negro boys, Boys’ Village,

pending filing of a brief.

Subsequently, this present proceeding was filed in the

Circuit Court of Baltimore City and we ask that this

Court so decide that Section 657, 659, 660 and 661 of Article

27 of the Annotated Code of Maryland, 1957 Edition as

amended, are unconstitutional in that the legislature is

without authority to promulgate a statute because it is

violative of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution

of the United States and, further, that the Court enter a

declaratory judgment and declare that any rule, policy,

custom, practice and usage pursuant to which said de

fendants, indicating the members of the State Board of

Public Welfare and members of the Boards of the four

training schools of the State of Maryland, or any of them,

their lessees, agents and successors in office by which they

deny the plaintiff and members in office by which they

deny the plaintiff and members of the class he represents

commitment, admission or transfer to any of the schools of

reformation operated and maintained by the defendants on

account of race and color; that this contravenes the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

And finally we request that this Court issue a permanent

injunction forever restraining the defendants and each of

them, their lessees, agents and successors in office from

denying to the plaintiff and other Negro youths, solely on

account of race and color, commitment, admission and

transfer to any training school established, operated and

maintained by the State of Maryland.

There is one further stipulation, may it please the Court:

For the purpose of this proceeding, the petitioner and

counsel for the State have entered into an agreement to

stipulate that the physical facilities in the four training

schools of the State are physically equal.

E. 35

(The Court) May I ask counsel if you intend to put on

any testimony?

(Mrs, Mitchell) Yes.

(The Court) I am not rushing you but I would like to

know about how much testimony you will have.

(Mr. Dearing) I am of the opinion that we do not need

much testimony here. It is just a matter of the plaintiff

testifying and some of the Department of Public Welfare

officials and some of it could possibly be stipulated as to

what they would testify to. If Mr. Murphy is agreeable,

we could enter into such a stipulation.

(The Court) The Court would like to see counsel in

chambers.

(A short recess was taken.)

(Mrs. Mitchell) May it please the Court, by agreement

of counsel, we wish to stipulate this document as Plain

tiff’s Exhibit 3, which is a statement of information on the

educational program at Maryland Training School for boys,

(The Court) That was prepared by the superintendent,

Mr. Elbert L. Fletcher in the latter months of 1959, I

think.

(Mr. Murphy) I see the date 1959 running through it.

PLAINTIFF’S EXHIBIT 3

“ Information on the Educational Program at

“ Maryland Training School For Boys, 2400 Cub Hill

Road, Baltimore 34, Md.

“A cademic

“Requirement: — All boys under 16 years of age must

attend at least a half a day of academic classes. Boys over

16 have the opportunity to attend academic classes if they

so desire.

E. 36

“Junior School

“Here all boys are in the academic program a full day.

These are the younger boys who live in the junior cottage

area. The regular public school curriculum is followed.

In addition to content subjects, these boys got three hours

per week of physical education and three hours per week

of arts and crafts. There are twelve regular classroom

teachers, physical education teacher, arts and crafts teacher,

and a building principal. All are college graduates, some

are fully certified and licensed by the State of Maryland,

while others are in the process of getting certified which

will require completing certain required courses in neigh

boring colleges.

“Boys are placed in classes according to level of reading

ability, intelligence quotient, and previous school experi

ences as well as physical and social maturity level. Follow

ing is the breakdown of classes as of November 1959.

“Teacher #1 — Primary Group — Grades 1 and 2 — 8,

9, 10, 11 years old.

“Teacher #2 — Primary Group — Grades 1, 2, and 3 —

12, 13, 14, 15 years old.

“Teacher #3 — Third grade —- Ages 8, 9, 10, 11, 12.

“Teacher # 4 — Fourth grade — Ages 9, 10, 11, 12.

“Teacher #5 — Fourth grade —- Ages 13, 14, 15.

“Teacher # 6 — Fifth grade — Ages 10, 11, 12, immature

13.

“Teacher # 7 — Fifth grade — Ages 13, 14, 15, immature

16.

“Teacher # 8 — Sixth grade — Ages 12, 13, 14, and 15.

Less aggressive.

“Teacher # 9 — Sixth grade — Ages 14, 15, immature 16.

More aggressive.

“Teacher #10 — Seventh, eighth, ninth, etc. grades.

Generally 13, 14, 15, and less mature 16 year olds.

E. 37

“Teacher #11 — Physical education for all grade levels.

“Teacher #12 — Arts and crafts for all grade levels.

“The average size of these classes for the Fall of 1959

is about 15. Some days they are less and other days more,