NC v Robinson Brief of Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

July 16, 2018

43 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NC v Robinson Brief of Amicus Curiae, 2018. 558b54b7-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a2b02ea4-6c7f-4da0-b6a1-e68d6865d553/nc-v-robinson-brief-of-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

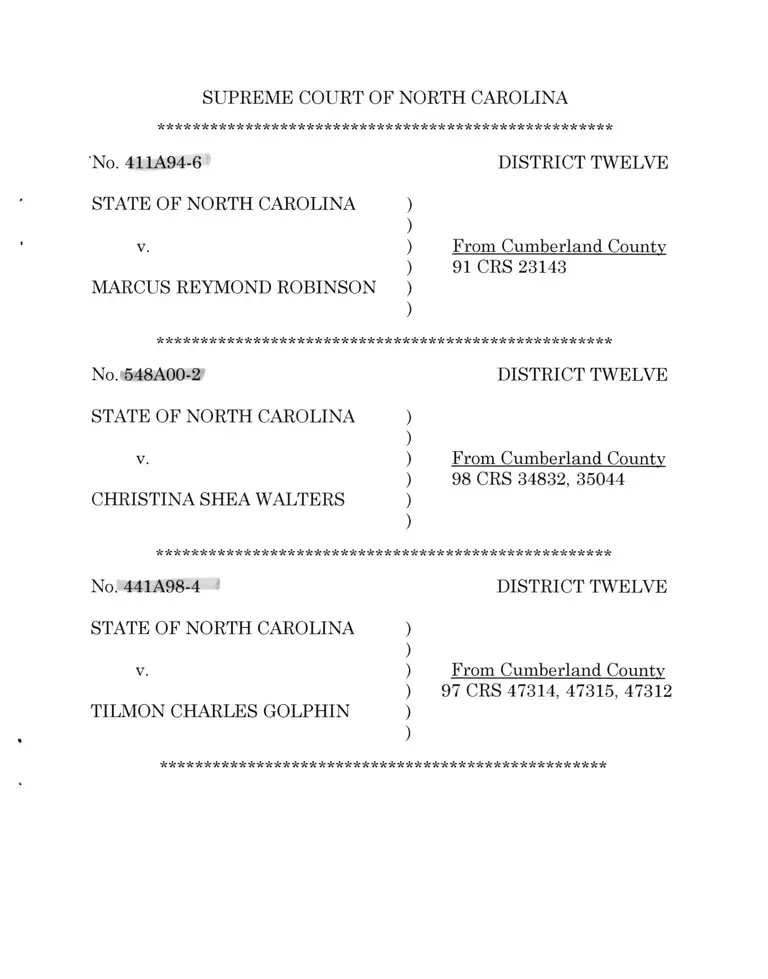

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

'k’k'k’k-k'k-k-k’k’k'k’k'k-k-k'k'k'k'k’k-k-kic’k'k'k'k'k-k-k'k'k-k'k'k'kic'k-k’k'k'k’k'k'k-k'k'k'k'k'k-k

No. 411A94-6 DISTRICT TWELVE

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA )

)

v. ) From Cumberland County

) 91 CRS 23143

MARCUS REYMOND ROBINSON )

)

•k’k 'k 'k 'k 'k i e - k 'k - k ’k - k ’k ' k ’k 'k - k 'k 'k 'k ’k ’k 'k -k 'k -k 'k -k -k -k 'k 'k ’k 'k -k -k -k -k -k j c 'k 'k 'k -k 'k ’k ' k ’k j c - k i e - k

No. 548A00-2 DISTRICT TWELVE

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA )

)

v. ) From Cumberland Countv

) 98 CRS 34832, 35044

CHRISTINA SHEA WALTERS )

)

•k-k'k-k-k-k'k’k'k'k-k'k'k-k'k'k'k’k’k'k'k’kic-k'k-k'k'k'k'k'k'k'k'k’k’k'k'k'k'k'k'k-k'k'kic’k-k-k'k'k'k

No. 441A98-4 DISTRICT TWELVE

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA )

)

v. ) From Cumberland County

) 97 CRS 47314, 47315, 47312

TILMON CHARLES GOLPHIN )

)

• k -k -k -k -k -k 'k ’k -k 'k -k -k -k 'k -k 'k 'k 'k -k 'k -k 'k -k 'k 'k -k 'k 'k 'k 'k -k -k ’k 'k -k 'k 'k -k -k 'k -k 'k 'k i c -k 'k -k 'k ’k i c 'k

Document electronically filed: 16 July 2018 - 04:43:09 PM

• k 'k ie -k -k 'k 'k 'k 'k 'k 'k ’k - k ’k ' k ’k 'k 'k - k 'k ’k ’k ’k ’k 'k 'k 'k 'k -k -k -k 'k -k 'k -k -k -k 'k ’k 'k 'k 'k 'k 'k 'k ’k - k - k ’k -k 'k

No. 130A03-2 DISTRICT TWELVE

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA )

)

v. )

)

QUINTEL MARTINEZ AUGUSTINE )

)

From Cumberland Countv

01 CRS 65079

'k-k-k’̂ 'k'kic'k'k'k'k'k'k'k'k'k'k’k-k’k-k'k'k'k'k'k-k-k'k-k’k-k-k-k-k'k'k’k-k'k'k’k'k'k-k-k'k'k'k’k’k'k

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF DEFEND ANTS-AP PELL ANTS

'k 'k 'k 'k 'k ’k 'k 'k 'k 'k 'k ’k - k 'k 'k 'k 'k 'k ’k 'k 'k 'k 'k 'k 'k i c 'k ’k ’k 'k 'k 'k 'k ’k ' k ’k - k 'k 'k 'k 'k 'k ’k 'k - k - k ’k 'k 'k 'k 'k 'k

INDEX

STATEMENT OF THE CASE AND FACTS..................2

STATEMENT OF INTEREST........................................ 2

INTRODUCTION............................................................ 4

ARGUMENT.................................................................... 6

I. This Court Must Not Allow Racial

Discrimination to Taint a Death Sentence........... 6

A. North Carolina Has a Long and Tragic

History of Racial Discrimination in Its

Death Penalty System...................................7

B. This Court Should Not Let the Racial

Discrimination in Defendants-Appellants’

Cases Stand Unaddressed.......................... 13

II. The Integrity of North Carolina’s Judicial

System Is Contingent on Juries Free of

Racial Bias.............................................................20

A. This Court and the United States Supreme

Court Have Long Recognized the

Importance of Juries Untainted by Racial

Bias...............................................................20

Ill

TABLE OF CASES AND AUTHORITIES.....................v

IV

B. A Death Sentence Tainted by Racial

Discrimination in Jury Selection Harms the

Defendant and the Prospective Juror and

Threatens the Integrity of the Entire

Judicial System........................................... 24

CONCLUSION..............................................................29

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE...................................... 32

V

TABLE OF CASES AND AUTHORITIES

CASES

Batson v. Kentucky,

476 U.S. 79 (1986)................................ 3, 12-13, 25, 28

Cooper v. Seaboard Air Line R. Co.,

163 N.C. 150, 79 S.E. 418 (1913)..............................21

Duncan v. Louisiana,

391 U.S. 145 (1968).................................................... 21

Furman v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 238 (1972).......................................................8

Georgia v. McCollum,

505 U.S. 42 (1992)................................................. 3, 28

J.E.B. v. Alabama ex rel. T.B.,

511 U.S. 127 (1994)............................................. 25, 28

Miller-El v. Cockrell,

537 U.S. 322 (2003).......................................................3

Miller-El v. Dretke,

545 U.S. 231 (2005)............................................... 3, 24

McCleskey v. Kemp,

481 U.S. 279 (1987).............................................passim

Neal v. Alabama,

612 So. 2d 1347 (Ala. Crim. App. 1992)...................27

Pena-Rodriguez v. Colorado,

137 S. Ct. 855 (2017)........................................... 22, 23

Peters v. Kiff,

407 U.S. 493 (1972).....................................................26

Powers v. Ohio,

499 U.S. 400 (1991)..................................21, 22, 24, 26

Rose v. Mitchell,

443 U.S. 545 (1979).................................................... 28

VI

CASES

Smith v. Hortler,

4 N.C. (Car. L. Rep.) 131 (1814)..........................20-21

Smith v. Texas,

311 U.S. 128 (1940)............................................. 21, 22

State v. Cofield,

320 N.C. 297, 357 S.E.2d 622 (1987)............ 23, 25-26

State v. Mettrick,

305 N.C. 383, 289 S.E.2d 354 (1982)........................ 22

State v. Moore,

329 N.C. 245, 404 S.E.2d 845 (1991)................. 23, 28

State v. Peoples,

131 N.C. 784, 42 S.E. 814 (1902)........................ 23, 26

State v. Sanderson,

336 N.C. 1, 442 S.E.2d 33 (1994)..............................24

State v. Scott,

314 N.C. 309, 333 S.E.2d 296 (1985)................. 21, 22

State v. Speller,

229 N.C. 67, 47 S.E.2d 537 (1948)............................ 11

Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U.S. 303 (1880)........................................10, 23, 25

Swain v. Alabama,

380 U.S. 202 (1965).......................................... 3, 11-12

Taylor v. Louisiana,

419 U.S. 522 (1975)................................................... 21

Woodson v. North Carolina,

428 U.S. 280 (1976)....................................................3-4

STATUTES & CONSTITUTIONS

N.C.G.S. § 15A-1335......................................................30

N.C.G.S. §§ 15A-2010 et seq. (2009)............................... 5

N.C. Const. Art. I, § 26 ................................................ 23

Vll

Death Penalty Info. Ctr., Current Death Row

Populations by Race (as of July 1, 2017),

http s: //de athp e naltyinfo. org/r ace - de ath-

row-inmates-executed-1976?scid=5&did=184 ... 8

Equal Justice Initiative, Illegal Racial

Discrimination in Jury Selection: A Continuing

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Legacy (Aug. 2010).................................................26-27

James Forman, Jr., Juries and Race in the

Nineteenth Century,

113 Yale L.J. 895 (Jan. 2004)............................... 22-23

Samuel R. Gross & Robert Mauro, Death and

Discrimination: Racial Disparities in Capital

Sentencing (1989)....................................................... 10

Seth Kotch & Robert P. Mosteller,

The Racial Justice Act and the Long Struggle

with Race and the Death Penalty in

North Carolina,

88 N.C. L. Rev. 2031 (Sept. 2010)..... 7, 8-9, 10-11, 15

Robert P. Mosteller, Responding to McCleskey and

Batson: The North Carolina Racial Justice Act

Confronts Racial Peremptory Challenges in

Death Cases,

10 Ohio St. J. Crim. L. 103 (2012)...................... 11, 15

Barry Nakell & Kenneth A. Hardy,

The Arbitrariness of the Death Penalty (1987).... 9, 10

N.C. Office of State Budget & Mgmt., State

Demographer, County Estimates, Population in

North Carolina Counties by Race (as of July 1, 2016),

https://files.nc.gov/ncosbm/demog/totalbyrace__

2016.html..................................................................... 8

https://files.nc.gov/ncosbm/demog/totalbyrace__

V lll

Barbara O’Brien & Catherine M. Grosso,

Confronting Race: How a Confluence of Social

Movements Convinced North Carolina to Go

Where the McCleskey Court Wouldn’t,

2011 Mich. St. L. Rev. 463 (2011)............................ 15

Barbara O’Brien, et al., Untangling the Role of

Race in Capital Charging and Sentencing in

North Carolina, 1990-2009,

94 N.C. L. Rev. 1997 (Sept. 2016)........................9, 10

Opinion, Justice Powell’s New Wisdom,

N.Y. Times (June 11, 1994),

http s: // w w w. nytime s. com/1994/06/11/op inion/

justice-powell-s-new-wisdom.html...........................15

Lauren M. Ouziel, Legitimacy and Federal

Criminal Enforcement Power,

123 Yale L.J. 2236 (May 2014)................................. 28

Daniel R. Pollitt & Brittany P. Warren,

Th irty Years of Disappointment:

North Carolina ’s Remarkable Appellate

Batson Record,

94 N.C. L. Rev. 1957 (Sept. 2016)............................13

Michael L. Radelet & Glenn L. Pierce, Race and

Death Sentencing in North Carolina, 1980-2007,

89 N.C. L. Rev. 2119 (Sept. 2011)........................9, 10

Isaac Unah, Empirical Analysis of Race and the

Process of Capital Punishment in North Carolina,

2011 Mich. St. L. Rev. 609 (2011)........................ 9, 10

Neil Vidmar, The North Carolina Racial Justice Act:

An Essay on Substantive & Procedural Fairness

in Death Penalty Litigation,

97 Iowa L. Rev. 1969 (Oct. 2012)..............................26

OTHER AUTHORITIES

IX

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Ronald F. Wright, et al., The Jury Sunshine Project:

Jury Selection Data as a Political Issue,

2018 Univ. 111. L. Rev. 4 (Sept. 7, 2017),

https://ssrn.com/abstract=2994288..........................12

https://ssrn.com/abstract=2994288

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

•k-k'k'k’k'k̂ -k'k-k'k'k-k’k'k'k'k'k-k'k’k-k'k'k'k'k'k-k'k'k'k-k'k’k’k'k'k'k'k’k-k'k'k'k’k’k'k’k-k-k-k-k

No. 411A94-6 DISTRICT TWELVE

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA )

)

v. ) From Cumberland County

) 91 CRS 23143

MARCUS REYMOND ROBINSON )

)

****************************************************

No. 548A00-2 DISTRICT TWELVE

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA )

)

v. ) From Cumberland County

) 98 CRS 34832, 35044

CHRISTINA SHEA WALTERS )

)

'k'k’k’k'k’k’k-k'k-k’k’k-k-k'k’kick'k'k’k’k’k’k'k'k’k'k̂ c'k'k'k'k-k'k'k-k’k-k-k’k-k-k-k-k'k’k'k'k-k'k-k

No. 441A98-4 DISTRICT TWELVE

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA )

)

v. ) From Cumberland County

) 97 CRS 47314, 47315, 47312

TILMON CHARLES GOLPHIN )

)

‘k ' k ’k 'k 'k -k 'k -k -k 'k -k 'k 'k -k -k -k 'k 'k 'k -k 'k ’k ’k 'k 'k - k 'k ’k ’k -k 'k -k 'k 'k 'k 'k -k -k 'k 'k ic 'k 'k 'k -k 'k 'k -k -k 'k 'k

-2 -

•k-k'k'k'k'k'k'k'k'k-k'k-kic-k'k-k'k'k'k'k'k'k’k'k’k-k'k'k’k’k'k’k'k'k-k'k'k-k'k'k'k’k-k'k-k’k'k-k'k'k

No. 130A03-2 DISTRICT TWELVE

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA )

)

v. ) From Cumberland County

) 01 CRS 65079

QUINTEL MARTINEZ AUGUSTINE )

)

'k 'k -k 'k ’k'k'Jc’k ’k -k ’k ’k -k 'k 'k ’k 'k 'k 'k 'k 'k -k 'k 'k 'k 'k 'k -k 'k 'k ic ’k ’k ic 'k 'k 'k 'k ’k-k 'k 'k -Jc 'kic'k ’k -k 'k -k -k 'k

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS

'k'k-k’k’k'k'k'k'k'k’k’k’k'k’k'k’k-k’k'k'k'k'k'k’k'kic’k-k'k-k-k-k’k̂ c’k-k’k’k-k'k'k'k'k'k'k'k-k-k'k-k-k

STATEMENT OF THE CASE AND FACTS

Amicus Curiae NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

(hereinafter “LDF”) adopts Defendants-Appellants’ Statement of the

Case and Facts.1

STATEMENT OF INTEREST

LDF is the nation’s first and foremost civil rights law organization.

Through litigation, advocacy, public education, organizing and outreach,

LDF strives to secure equal justice under the law for all Americans, and

1 Pursuant to N.C. R. App. P. 28(i)(2), LDF states that no person or entity other

than amicus curiae, its members, or its counsel, directly or indirectly wrote the brief

or contributed money for its preparation.

-3 -

to break down barriers that prevent African Americans from realizing

their full civil and human rights. Since its inception, LDF has sought to

eliminate the arbitrary role of race on the administration of the criminal

justice system by challenging laws, pohcies, and practices that have a

disproportionate impact on African Americans and other communities of

color.

LDF has long been committed to ensuring racial equality in jury

selection, having served as counsel or amicus curiae in multiple cases

before the United States Supreme Court on this issue. See, e.g., Miller-

El v. Dretke, 545 U.S. 231 (2005); Miller-El v. Cockrell, 537 U.S. 322

(2003); Georgia v. McCollum, 505 U.S. 42 (1992); Batson v. Kentucky, 476

U.S. 79 (1986); Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965). Moreover, as

counsel in McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 US. 279 (1987), LDF has a significant

interest in the North Carolina Legislature’s response to the McCleskey

decision by permitting statutory claims of racial discrimination based on

statistical evidence.

LDF has also represented individuals who have been sentenced to

death in North Carolina as part of its advocacy for a fair and just criminal

justice system. For example, LDF was counsel in Woodson v. North

-4 -

Carolina, 428 U.S. 280 (1976), in which the United States Supreme Court

invalidated North Carolina’s mandatory death penalty scheme as a

violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.

Given its mission, history, and expertise in opposing racial injustice

generally—and in combating racial discrimination in the use of

peremptory strikes and in the imposition of the death penalty

specifically—LDF has a substantial interest in the issues raised in

Defendants-Appellants’ cases.

INTRODUCTION

Since the early days of LDF’s existence—when Thurgood Marshall

represented capitally charged and death-sentenced African-American

individuals across the South—to the present day, LDF has been deeply

concerned with the pernicious influence of race in the administration of

the death penalty. That concern is certainly justified with respect to the

death penalty in North Carolina. Throughout North Carolina’s history,

its death penalty has had a deep and troubling association with racial

discrimination. Multiple statistical studies—utilizing data across

several decades—demonstrate the continuing effect of race in North

Carolina’s death penalty, especially with respect to the race of the victim

and the race of prospective jurors.

Yet, despite this compelling evidence of systemic racial

discrimination, the ability for capitally-charged and death-sentenced

individuals to seek judicial relief has been largely truncated by the

United States Supreme Court’s decision in McCleskey, which ruled that

statistical evidence alone is insufficient to support an inference that

decisionmakers acted with a discriminatory purpose. LDF represented

Warren McCleskey in that case and continues to believe that it was

wrongly decided.

But the North Carolina Legislature responded to the unduly

restrictive holding in McCleskey by passing the North Carolina Racial

Justice Act, N.C.G.S. §§ 15A-2010 et seq. (2009) (“RJA”), which provides

statutory relief from the death penalty based on statistical evidence of

racial discrimination. With this statutory mechanism, Defendants

presented compelling evidence of racial bias in the prosecution’s use of

peremptory challenges in Cumberland County, in the prosecutorial

district and judicial divisions containing Cumberland County, and

- 5 -

throughout North Carolina.

-6 -

That prosecutors discriminated against African-American

prospective jurors is clear from the record and led the Superior Court of

Cumberland County to vacate Defendants’ death sentences. Knowing

now that there is significant evidence of racial discrimination in

Defendants’ cases, it is incumbent upon this Court to allow Defendants

to seek and secure sentencing relief. Otherwise, this continuing stain of

racial discrimination will undermine not only the legitimacy of

Defendants’ death sentences, but also public confidence in the integrity

of North Carolina’s judicial system as a whole. LDF urges this Court to

grant Defendants’ requested relief, thereby making clear and

unequivocal that the courts of North Carolina will not tolerate racial

discrimination in jury selection and the administration of the death

penalty.

ARGUMENT

I. This Court Must Not Allow Racial Discrimination to Taint a

Death Sentence.

Throughout North Carolina’s history, racial discrimination has

placed an unacceptable stain on its death penalty system. With the

passage of the Racial Justice Act, Defendants were also able to establish

that race was a significant factor in the prosecution’s use of peremptory

- 7-

challenges in Cumberland County, in the prosecutorial district and the

judicial divisions containing Cumberland County, and across the State of

North Carolina at the time of their capital trials. This Court, therefore,

must permit Defendants to pursue relief from death sentences that are

unquestionably tainted by this compelling evidence of racial bias.

A. North Carolina Has a Long and Tragic History of

Racial Discrimination in Its Death Penalty System.

North Carolina’s death penalty has a long and tragic association

with racial discrimination. African Americans—mostly slaves—

comprised 71% of those executed from 1726 to 1865. Seth Kotch & Robert

P. Hosteller, The Racial Justice Act and the Long Struggle with Race and

the Death Penalty in North Carolina, 88 N.C. L. Rev. 2031, 2044-45 (Sept.

2010) (hereinafter “Kotch, Racial Justice Act”). “[M]any slaveowners

believed that these public executions served an important purpose in

deterring misbehavior among the slave population at large.” Id, at 2047-

48. This trend of primarily executing African Americans continued in

North Carolina between the end of the Civil War and 1910, with African

Americans making up 74% of the 160 people executed during that time

even though they were, at most, 38% of the overall population. Id. at

2053.

-8 -

In 1910, the State of North Carolina assumed responsibihty for

executions, which ensued until 1961, when the last North Carolina

prisoner was executed before the death penalty was ruled

unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court in Furman v.

Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972). Kotch, Racial Justice Act at 2039. During

that time between 1910 and 1961, 283 of 362 (78%) individuals executed

were African American. Id. At the same time, North Carolina’s African-

American population ranged from only 32% in 1910 to 25% in 1960. Id.

at 2056. Presently, 78 of the 152 (51%) individuals on North Carolina’s

death row are African American2 although African Americans comprise

only 22% of North Carolina’s general population.3

One of the most indelible legacies of slavery and Jim Crow on North

Carolina’s death penalty is the persistent trend of executing people,

especially African Americans, for crimes committed against white

victims. The execution of African Americans accused of raping white

women stands as a stark example: from the pre-Furman era of 1910 to

2 Death Penalty Info. Ctr., Current Death Row Populations by Race (as of

July 1, 2017), https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/race-death-row-inmates-executed-

1976?scid=5&did=184.

3 N.C. Office of State Budget & Mgmt., State Demographer, County Estimates,

Population in North Carolina Counties by Race (as of July 1, 2016),

https://files.nc.gov/ncosbm/demog/totalbyrace_2016.html.

https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/race-death-row-inmates-executed-

https://files.nc.gov/ncosbm/demog/totalbyrace_2016.html

-9 -

1961, 67 of 78 men executed for rape were African American, and the

victim was confirmed to be white in 58 of those cases. Id. at 2066.

Moreover, a study of North Carolina homicides from 1980 to 2007 found

that “the odds of a death sentence for those suspected of killing Whites

are approximately three times higher than the odds of a death sentence

for those suspected of killing Blacks,” and the “race of the victim effect is

largest for Black suspects suspected of killing White victims, who are five

times more likely to be sentenced to death than Black suspects with

Black victims.” Michael L. Radelet & Glenn L. Pierce, Race and Death

Sentencing in North Carolina, 1980-2007, 89 N.C. L. Rev. 2119, 2120,

2141 (Sept. 2011) (hereinafter “Radelet, Race and Death Sentencing’).

Numerous other studies confirm the persistent influence of the victim’s

race in the administration of the death penalty in North Carolina:

• Analysis of 1977-78 North Carolina data: Defendants of any race

who killed a white victim were “six times more likely to be found

guilty of first degree murder than defendants in cases with

nonwhite victims.”4 “In addition, nonwhite defendants were

4 Isaac Unah, Empirical Analysis of Race and the Process of Capital

Punishment in North Carolina, 2011 Mich. St. L. Rev. 609, 622 (2011) (hereinafter

“Unah, Empirical Analysis’') (quoting Barry Nakell & Kenneth A. Hardy, The

Arbitrariness of the Death Penalty 146-48 (1987)) (hereinafter “Nakell,

Arbitrariness”)', see also Radelet, Race and Death Sentencing, at 2134 (citation

omitted); Barbara O’Brien, et al., Untangling the Role of Race in Capital Charging

and Sentencing in North Carolina, 1990-2009, 94 N.C. L. Rev. 1997, 2005 (Sept. 2016)

(hereinafter “O’Brien, “Untangling the Role”).

- 10-

more likely to receive the death penalty compared to whites.”5

• Analysis of 1977-80 North Carolina data: “Among [ ] homicides

with additional felony circumstances present . . . 13.6% of those

suspected of killing Whites were sentenced to death, compared

to 4.3% of those suspected of killing Blacks.”6

• Analysis of 1993-97 North Carolina data: “When a nonwhite

defendant kills a white victim, the death-sentencing rate is 5.1

percent. However, when a nonwhite defendant kills a nonwhite

victim, the death-sentencing rate is only 1.5 percent.”7

• Analysis of 1990-2009 North Carolina data: (1) “Cases in which

the defendant killed at least one white victim were significantly

more likely to receive a death sentence than cases in which the

defendant killed only black victims”; (2) “Prosecutors were

significantly less likely to bring cases in which black defendants

killed only black victims to a capital trial than any other case”;

(3) “Juries were significantly less likely to sentence defendants

to death in cases where white defendants kills only black victims

than any other case.”8

Equally troubling is the historic and longtime exclusion of African

Americans from capital juries. This disturbing trend is rooted in the

absolute bar to jury service for African Americans during the time of

slavery. Kotch, Racial Justice Act, at 2072. Even after the United States

Supreme Court ruled in Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880),

5 Unah, Empirical Analysis, at 622 (citing Nakell, Arbitrariness, at 94).

6 Radelet, Race and Death Sentencing, at 2135 (citing Samuel R. Gross &

Robert Mauro, Death and Discrimination: Racial Disparities in Capital Sentencing

89 (1989)).

7 Unah, Empirical Analysis, at 637.

8 O’Brien, Untangling the Role, at 2043.

-11 -

that the Fourteenth Amendment prohibited states from enacting laws

that barred African Americans from serving on juries, North Carolina

instituted statutory requirements to jury service during the first half of

the twentieth century that effectively achieved the same result. For

example, North Carolina statutes during that time required:

“(1) payment of taxes for the preceding year; (2) good moral character;

and (3) sufficient intelligence” for jury service, which gave wide discretion

to exclude African Americans from juries. Kotch, Racial Justice Act, at

2073. As an example, this Court noted in a 1948 decision that no African

American was eligible for jury service, let alone seated, in an eastern

North Carolina county where African Americans made up the majority of

the population. State v. Speller, 229 N.C. 67, 68-70, 47 S.E.2d 537, 538-

39 (1948), cited in Robert P. Mosteller, Responding to McCleskey and

Batson.- The North Carolina Racial Justice Act Confronts Racial

Peremptory Challenges in Death Cases, 10 Ohio St. J. Crim. L. 103, 126

n.109 (2012) (hereinafter “Mosteller, Responding to McCleskey and

Batson”).

Even though the United States prohibited the systemic exclusion of

African Americans from juries, see Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202

- 12 -

(1965), and the discriminatory use of peremptory challenges against

African Americans, see Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986), African

Americans are still disproportionately excluded from jury service, as

demonstrated in Defendants’ cases. See infra Section I.B. Similarly, a

recent study conducted by former prosecutors examined 2011 felony

trials in North Carolina and found that prosecutors used peremptory

challenges against African-American prospective jurors at twice the rate

they excluded white prospective jurors. Ronald F. Wright, et al., The

Jury Sunshine Project: Jury Selection Data as a Political Issue,

2018 Univ. 111. L. Rev. 4, 26 (Sept. 7, 2017), https://ssrn.com/abstract=

2994288 (available via SSRN).

In his concurrence in Batson, Justice Marshall emphasized how the

“[mjisuse of the peremptory challenge to exclude black jurors has become

both common and flagrant” because, inter alia, “[a]ny prosecutor can

easily assert facially neutral reasons for striking a juror, and trial courts

are ill equipped to second-guess those reasons.” Batson, 476 U.S. at 103,

105 (Marshall, J., concurring). Additionally, “the conscious or

unconscious racism” of prosecutors or judges may lead to differing

perceptions of African American jurors, as compared to white jurors, and

https://ssrn.com/abstract=

- 13 -

the court’s ready acceptance of the prosecutor’s proposed explanation for

the challenge. Id. at 106. The record of Batson rulings in this Court and

the North Carolina Court of Appeals justifies Justice Marshall’s concerns

about the difficulties of remedying the racially discriminatory use of

peremptory challenges: the appellate courts of North Carolina have never

ruled that a prosecutor intentionally discriminated against a juror of

color since Batson was decided.9 Daniel R. Pollitt & Brittany P. Warren,

Thirty Years of Disappointment: North Carolina ’s Remarkable Appellate

Batson Record, 94 N.C. L. Rev. 1957, 1961-62 (Sept. 2016) (hereinafter,

“Pollitt, Thirty Years of Disappointment”).

B. This Court Should Not Let the Racial Discrimination

in Defendants-Appellants’ Cases Stand Unaddressed.

Despite the substantial amount of statistical evidence of racial

discrimination in North Carolina’s death penalty, the United States

9 On three occasions, this Court found the trial court to have erred in finding

no prima facie case of discrimination in the first of Batson’s three-step inquiry and

conducted or ordered further review, but it has never reached an ultimate finding of

intentional discrimination. Pollitt, Thirty Years of Disappointment, at 1961. The

North Carolina Court of Appeals has found intentional discrimination in the

peremptory challenges used against two white prospective jurors, and a prima facie

case of discrimination— which did not lead to findings off intentional racial

discrimination—in two other cases. Id. at 1961-63. However, no North Carolina

appellate court has found that a peremptory challenge was used in an intentionally

discriminatory manner against a prospective juror of color. A search for decisions

issued by this Court and the North Carolina Court of Appeals after the publication of

this study did not yield any state appellate decisions finding Batson violations.

- 14-

Supreme Court’s decision in McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279 (1987), has

placed significant obstacles to remedying this discrimination. In a closely

divided 5-4 decision, the majority in McCleskey acknowledged that there

was “a discrepancy that appears to correlate with race” in terms of whom

Georgia prosecutors decided to charge with capital crimes. Id. at 312.

Nevertheless, the Court concluded that the stark statistics of racial

disparities established in the case were not sufficient to prove a

“discriminatory purpose,” as required by the Fourteenth Amendment,

and characterized the racial disparities as “an inevitable part of our

criminal justice system.” Id. at 295-99, 312. As Justice Blackmun

commented in his dissent, the McCleskey Court “sanction[ed] the

execution of a man despite his presentation of evidence that establishes

a constitutionally intolerable level of racially based discrimination

leading to the imposition of his death sentence.” Id. at 345 (Blackmun,

J., dissenting).

LDF is the legal organization that represented Warren McCleskey

before the United States Supreme Court and continues to beheve that

the McCleskey decision was an incorrect interpretation of the Fourteenth

Amendment, which has sharply limited the ability of victims of racial

- 15 -

discrimination in the criminal justice system, including capital

defendants, to seek judicial redress. Indeed, Justice Powell, who wrote

the majority opinion in McCleskey and cast the deciding vote, publicly

stated in retirement that, in retrospect, he would have decided McCleskey

differently. Opinion, Justice Powell's New Wisdom, N.Y. Times (June 11,

1994), https://www.nytimes.com/1994/06/ll/opinion/justice-powell-s-

new-wisdom.html.

However, in passing the RJA, the North Carolina Legislature

specifically responded to the unjust constraints imposed by McCleskey on

federal claims of racial discrimination by permitting state statutory

claims of racial discrimination based on statistical evidence. See Barbara

O’Brien & Catherine M. Grosso, Confronting Race: How a Confluence of

Social Movements Convinced North Carolina to Go Where the McCleskey

Court Wouldn't, 2011 Mich. St. L. Rev. 463, 463-64, 473-74 (2011);

Mosteller, Responding to McCleskey and Batson at 116; Kotch, Racial

Justice Act at 2111-13. With that opportunity provided by the RJA,

Defendants have presented overwhelming statistical evidence of racial

discrimination in the selection of juries in capital cases in Cumberland

County (where they were sentenced to death), in the prosecutorial district

https://www.nytimes.com/1994/06/ll/opinion/justice-powell-s-new-wisdom.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1994/06/ll/opinion/justice-powell-s-new-wisdom.html

- 16 -

and judicial divisions containing Cumberland County, and across the

entire state of North Carolina.

Defendant Marcus Robinson’s statistical evidence was comprised of

an exhaustive study of jury selection that utilized: (1) “a complete,

unadjusted study of race and strike decisions for 7,421 venire members

drawn from the 173 proceedings for the inmates of North Carolina's

death row in 2010”; (2) “a regression study of a 25% random sample

drawn from the 7,421 venire member data set that analyzed whether

alternative explanations impacted the relationship between race and

strike decisions”; and (3) “a regression study of 100% of the venire

members from the Cumberland County cases.” Order Granting Motion

for Appropriate Relief p. 44, North Carolina v. Robinson, No. 91 CRS

23143 (N.C. Super. Ct. Apr. 20, 2012) (hereinafter “Robinson Order”).

Having reviewed this evidence, as well as the evidence presented

by the State, the Superior Court of Cumberland County made the

following findings, among many, in a meticulous and comprehensive 167-

page opinion in Mr. Robinson’s case:

• “[Pjrosecutors statewide struck 52.6% of eligible black venire

members, compared to only 25.7% of all other ehgible venire

members. . . . The probability of this disparity occurring in a

race-neutral jury selection process is less than one in ten

- 17-

trillion.” Id. p. 58.

• “Of the 166 cases statewide that included at least one black

venire member, prosecutors struck an average of 56.0% of

eligible black venire members, compared to only 24.8% of all

other eligible venire members. . . . The probabibty of this

disparity occurring in a race-neutral jury selection process is less

than one in 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.” Id.

p. 59.

• “The statewide disparity in strike rates has been consistent over

time, whether viewed over the entire study period, in four five-

year periods, or two ten-year periods.” Id.

• In the “Fourth Judicial Division as constituted since January 1,

2000,” which includes Cumberland County, “prosecutors struck

an average of 62.4% of eligible black venire members, compared

to only 21.9% of all other eligible venire members. . . . The

probability of this disparity occurring in a race-neutral jury

selection process is less than one in 1,000.” Id. p. 65.

• In the “former Second Judicial Division as constituted from

January 1, 1990 through December 21, 1999,” when it contained

Cumberland County, “prosecutors struck an average of 51.5% of

eligible black venire members, compared to only 25.1% of all

other eligible venire members. . . . The probability of this

disparity occurring in a race-neutral jury selection process is less

than one in 100,000,000,000.” Id.

• In “Cumberland County (and Prosecutorial District 12) from

January 1, 1990 through July 1, 2010, . . . prosecutors struck an

average of 52.7% of eligible black venire members, compared to

only 20.5% of all other eligible venire members. . . . The

probability of this disparity occurring in a race-neutral jury

selection process is less than one in 1,000.” Id. pp. 65-66.

• “After fully controlling for the 12 non-racial variables” that are

“highly predictive for prosecutorial strike decisions,” such as

reservations about the death penalty and having been accused of

a crime, “the race of the venire member is still statistically

- 18-

significant withp-value of <0.001 and an odds ratio of 2.48 . . . .

The probability of observing a racial disparity of this magnitude

in a race-neutral jury selection process is 1.34 in 1,000,000. . . .

There is a 95% chance that the odds of a black venire member

being struck by the State, after controlling for non-racial

variables, is between 1.71 and 3.58 times higher than the odds

of other venire members being struck.” Id. p. 78.

• “After fully controlling for eight variables,” which are highly

predictive for prosecutorial strike decisions specific to the

Cumberland County data set, “the race of the venire member is

still statistically significant with a p-value of <0.01 and an odds

ratio of 2.57 . . . . There is a 95% chance that the odds of a black

venire member being struck by the State in Cumberland County,

after controlling for non-racial variables, is between 1.50 and

4.40 times higher than the odds of other venire members being

struck.” Id. p. 82.

The Superior Court of Cumberland County made similar findings in the

case of Defendants Tilmon Golphin, Christina Walters, and Quintel

Augustine. Order Granting Motions for Appropriate Relief pp. 136-201,

North Carolina v. Golphin, et al., Nos. 97 CRS 47314-15, 98 CRS 34832,

35044, 01 CRS 65079 (N.C. Super. Ct. Dec. 13, 2012) (hereinafter

“Golphin Order”). The Superior Court accordingly vacated Defendants’

death sentences and resentenced them to fife without parole. Robinson

Order p. 167; Golphin Order p. 210.

The statistical evidence in Defendants’ cases reveals the type of

racial discrimination that continues to exist beyond the protection of the

Fourteenth Amendment due to the McCleskey decision, and the type of

- 19 -

discrimination that the RJA was designed to redress. Especially when

considered in the context of the other evidence of discrimination

presented by Defendants—such as the history of racial discrimination in

jury selection, the role of unconscious bias in jury selection, and

individual case examples of jury discrimination, see Robinson Order

pp. 112-19, 132-155; Golphin Order pp. 87-97, 112-136—this Court

simply cannot ignore the inevitable conclusion from the statistical

analyses in these cases. That conclusion is that African Americans are

routinely and systematically excluded from capital juries because of their

race in Cumberland County, in the prosecutorial district and judicial

divisions containing Cumberland County, and across North Carolina.

That bell cannot be unrung, and to foreclose the possibility of sentencing

relief to Defendants at this juncture would be wholly unjust and

undermine the legitimacy and credibility of North Carolina’s judicial

system. Indeed, it would be a tragedy for the members of this Court to

one day have the same regret as Justice Powell by letting stand,

untouched, a death sentence infected by such compelling evidence of

racial bias.

-20-

II. The Integrity of North Carolina’s Judicial System Is

Contingent on Juries Free of Racial Bias.

This Court, as well as the United States Supreme Court, has

consistently recognized the crucial role that a jury plays to ensure public

confidence in our judicial system. Ignoring the compelling evidence of

jury discrimination in Defendants’ cases, therefore, not only harms

Defendants and the unlawfully struck jurors, but also undermines the

integrity of the judicial process itself. The substantial evidence of racial

discrimination in the selection of Defendants’ juries erodes public

confidence in North Carolina’s judicial system and must be remedied by

this Court.

A. This Court and the United States Supreme Court Have

Long Recognized the Importance of Juries Untainted

by Racial Bias.

The importance of ensuring that Defendants be tried by a

legitimately convened jury—for them personally, but also to the

community at large—cannot be overstated. Over two centuries ago, this

Court noted that North Carolina’s “courts of justice should be so

organized as to afford full assurance to every suitor, that his cause shall

be patiently investigated, and impartially decided.” Smith v. Hortler, 4

N.C. (Car. L. Rep.) 131, 131 (1814) (holding that a defendant could not

- 2 1 -

receive a fair trial because of potential jury-pool biases); see also Duncan

v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145, 153 (1968) (noting that the jury is

“fundamental to our system of justice”). The jury “spreads amongst all

classes a respect for the decisions of the law” and “makes all feel that

they have duties to fulfill towards society, and that they take a part in its

government[.]” Cooper v. Seaboard Air Line R. Co., 163 N.C. 150, 150, 79

S.E. 418, 419 (1913) (citation omitted); see also Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S.

400, 406 (1991) (“One of [the jury’s] greatest benefits is in the security it

gives the people that they . . . being part of the judicial system of the

country can prevent its arbitrary use or abuse.”) (citation omitted). And

by employing the community’s “commonsense judgment,” the jury acts as

a “hedge against the overzealous or mistaken prosecutor” or “perhaps

overconditioned or biased response of a judge.” Taylor v. Louisiana, 419

U.S. 522, 530 (1975) (citation omitted).

To achieve its goals, the jury must be a “body truly representative

of the community.” State v. Scott, 314 N.C. 309, 311-12, 333 S.E.2d 296,

297-98 (1985) (quoting Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128, 130 (1940)).

Restricting the privilege of passing judgment to a subset of the

community engenders doubts regarding the validity of those judgments.

- 22 -

See Powers, 499 U.S. at 407 (emphasizing that public confidence in the

legitimacy of the jury is essential to help ensure the “continued

acceptance of the laws by all of the people”) (citation omitted); State v.

Mettrick, 305 N.C. 383, 385, 289 S.E.2d 354, 356 (1982) (“[T]he

appearance of a fair trial before an impartial jury is as important as the

fact of such a trial.”).

Because representative juries are the foundation of public

confidence in our courts, eliminating racial discrimination takes on

particular urgency in the context of jury selection. See Pena-Rodriguez

v. Colorado, 137 S. Ct. 855, 868 (2017); Scott, 314 N.C. at 311-12, 333

S.E.2d at 297-98 (holding that the jury must be free of racial

discrimination to ensure it is a “body truly representative of the

community”) (quoting Smith, 311 U.S. at 130). In fact, the centrality of

the jury trial to a functioning democracy led the Reconstruction

Republicans to place special emphasis on purging the racism from

Southern juries. See James Forman, Jr., Juries and Race in the

Nineteenth Century, 113 Yale L.J. 895, 897, 923-25 (Jan. 2004); see also

id. at 926 (“An increasing number of Republicans saw the disabilities that

prevented blacks from serving on state juries as the central impediment

- 23 -

to justice for blacks in the South.”).

Similarly, North Carolina revised its Constitution to expressly

prohibit jury discrimination: “No person shall be excluded from jury

service on account of sex, race, color, religion, or national origin.” N.C.

Const. Art. I, § 26. This Court has called this a “declaration]” by the

“people of North Carolina . . . that they will not tolerate the corruption of

their juries by racism, sexism and similar forms of irrational prejudice.”

State v. Moore, 329 N.C. 245, 247, 404 S.E.2d 845, 847 (1991) (quoting

State v. Cofield, 320 N.C. 297, 302, 357 S.E.2d 622, 625 (1987)); see also

State v. Peoples, 131 N.C. 784, 784, 42 S.E. 814, 815 (1902) (recognizing

that excluding African Americans from juries is an “assertion of their

inferiority, and a stimulant to . . . race prejudice”) (quoting Strauder, 100

U.S. at 303).

The United States Supreme Court has likewise repeatedly

recognized that racial discrimination must be eliminated from jury

discrimination. As the Court explained just last year, after the Civil War,

“racial discrimination in the jury system posed a particular threat both

to the promise of the [Fourteenth] Amendment and to the integrity of the

jury trial.” Pen a-Rodriguez, 137 S. Ct. at 867. Thus, the United States

- 2 4 -

Supreme Court has repeatedly held that racial exclusion of jurors is

unconstitutional. See id. (collecting cases). These cases reiterate that

racism undermines the core promise of a jury trial by destroying the “fact

and the perception” that the jury system is truly a “check against the

wrongful exercise of power by the State and its prosecutors.” Powers, 499

U.S. at 411 (citation omitted). Indeed, “prosecutors drawing racial lines

in picking juries establish state-sponsored group stereotypes rooted in,

and reflective of, historical prejudice[.]” Miller-El v. Dretke, 545 U.S. 231,

237-38 (2005) (citation and quotation marks omitted).

In sum, prosecutors “may strike hard blows” but not “foul ones,”

and must “refrain from improper methods calculated to produce a

wrongful conviction” no less than they may “use every legitimate means

to bring about a just one.” State v. Sanderson, 336 N.C. 1, 8, 442 S.E.2d

33, 38 (1994) (citation and internal quotation marks omitted). Racial

discrimination in peremptory strikes violate both that principle and

venerable precedent.

B. A Death Sentence Tainted by Racial Discrimination in

Jury Selection Harms the Defendant and the

Prospective Juror and Threatens the Integrity of the

Entire Judicial System.

When, as here, there is evidence of racial discrimination in jury

- 25 -

selection, the defendant is deprived of his fundamental right to the

considered judgment of a representative jury as a check against the

exercise of arbitrary or biased state power. See Batson, 476 U.S. at 86-

87 (citing Strauder, 100 U.S. at 309) (explaining that a jury of one’s peers

helps “secure the defendant’s right under the Fourteenth Amendment to

protection of life and liberty against race or color prejudice”). Moreover,

a racially discriminatory peremptory strike creates a significant risk

“that the prejudice that motivated the discriminatory selection of the jury

will infect the entire proceedings.” J.E.B. v. Alabama ex rel. T.B., 511

U.S. 127, 140 (1994).

Unhindered racially biased peremptory challenges place “the

courts’ imprimatur on attitudes that historically” have denied African

Americans full citizenship and “entangles the courts in a web of prejudice

and stigmatization.” Cofield, 320 N.C. at 303, 357 S.E.2d at 625-26. That

is because racial discrimination in jury selection undermines the

“integrity of the judicial system.” Id. at 304, 357 S.E.2d at 626; see also

id. at 301, 357 S.E.2d at 625 (“This Court has long recognized the wrong

inherent in jury proceedings tainted by racial discrimination.”). This

Court has appreciated this reality for over one hundred years. See id, at

- 26 -

301, 357 S.E.2d at 625 (examining Peoples, 131 N.C. at 790, 42 S.E. at

816 (1902)).

Social science confirms the depth of the harm to the defendant.

Non-diverse juries are less deliberative, bring a narrower set of life

experiences to bear, make more factual mistakes, and are less likely to

consider the full body of evidence. See Neil Vidmar, The North Carolina

Racial Justice Act: An Essay on Substantive & Procedural Fairness in

Death Penalty Litigation, 97 Iowa L. Rev. 1969, 1972-75 (Oct. 2012)

(collecting evidence and examples). And they are less able to prevent the

insidious effects of explicit and implicit bias. Id. at 1975-80; see also

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493, 503 (1972) (stating that racial prejudice

within the jury system “create[s] the appearance of bias in the decision

of individual cases, and . . . increase[s] the risk of actual bias as well.”).

The harm to the illegally struck juror is just as consequential. Not

only are the juror’s state and federal constitutional rights infringed, he

or she “suffers a profound personal humiliation heightened by its public

character.” Powers, 499 U.S. at 413-14. A report by the non-profit Equal

Justice Initiative emphasizes the impact on individuals subjected to this

humiliation. See Equal Justice Initiative, Illegal Racial Discrimination

- 2 7 -

in Jury Selection: A Continuing Legacy 28-34 (Aug. 2010)

(hereinafter “EJI Report”), https://eji.org/sites/default/files/illegal-racial-

discrimination-in-jury-selection.pdf. Twenty years after being struck,

one African-American juror “grew emotional” when he “recalled how the

prosecutor’s racist actions made him feel unworthy.” Id. at 30.10 Another

African-American juror, struck because he “had traffic tickets and

expressed hesitation about the death penalty” (although white

individuals with similar characteristics were not struck), was

unsurprised “because that’s how the system is around here.” Id. at 29.

These and other stories illustrate how racially biased peremptory

challenges undermine African Americans’ confidence in the judicial

system.

That skepticism among African-American prospective jurors about

the integrity of the judicial process is connected to the overall harm to

the entire community’s perception of justice. This Court has emphasized

“that the judicial system of a democratic society must operate

evenhandedly” and “be perceived to operate evenhandedly” if “it is to

10 His strike was recognized to be a Batson violation by the Court of Criminal

Appeals of Alabama in 1992. Neal v. Alabama, 612 So. 2d 1347, 1349-50 (Ala. Crim.

App. 1992); EJI Report at 30 & n.150.

https://eji.org/sites/default/files/illegal-racial-discrimination-in-jury-selection.pdf

https://eji.org/sites/default/files/illegal-racial-discrimination-in-jury-selection.pdf

- 2 8 -

command the respect and support of those subject to its jurisdiction.”

Moore, 329 N.C. at 247, 404 S.E.2d at 847 (citation omitted); see also

Georgia v. McCollum, 505 U.S. 42, 49-50 (1992) (concluding that bias in

the jury system “undermine[s] the very foundation of our system of

justice—our citizens’ confidence in it”); Batson, 476 U.S. at 87

(recognizing that jury discrimination “undermine[s] public confidence in

the fairness of our system of justice”) (citation omitted); Rose v. Mitchell,

443 U.S. 545, 556 (1979) (observing “injury to the jury system, to the law

as an institution, to the community at large, and to the democratic ideal

reflected in the processes of our courts”) (citation omitted). In short, jury

discrimination causes the belief that “the deck has been stacked in favor

of one side.” 511 U.S. at 140 (internal citation and quotation

marks omitted); see also Lauren M. Ouziel, Legitimacy and Federal

Criminal Enforcement Power, 123 Yale L.J. 2236, 2269-70 (May 2014)

(citing research showing “that people’s perceptions of an authority’s

legitimacy are influenced most by their perceptions of the fairness of the

process and procedures by which it enforces the law”).

For the African-American citizens of North Carolina—indeed, for

all citizens of this State—to have confidence in the rule of law, racial

- 29 -

discrimination in jury selection must be eliminated. Given the

constraints from the McCleskey decision, it is crucial for Defendants to be

able to use statistical evidence to show how their individual cases reflect

a pattern of systemic and widespread racial discrimination in jury

selection to fully address the harm suffered by capital defendants, the

'illegally struck jurors, and the larger community. This is precisely why

the North Carolina Legislature passed the RJA. If this Court were to

foreclose Defendants from seeking appropriate remedies—through the

RJA or other relevant state statutory or federal constitutional claims—it

would place a devastating judicial imprimatur on the racial

discrimination that has been established in these cases.

CONCLUSION

Over three decades ago, the United States Supreme Court was

presented with compelling statistical evidence of racial discrimination in

the McCleskey case. Justice Powell, who cast the deciding vote against

remedying the discrimination, came to regret his decision, but the

devastating consequences are felt to this day. LDF respectfully urges the

members of this Court to avoid Justice Powell’s mistake, but instead

leave a legacy of unequivocal condemnation of racial discrimination in

- 3 0 -

North Carolina’s judicial processes, especially with the life-or-death

consequences of a capital case. Thus, for the foregoing reasons, LDF

respectfully requests this Court to provide all appropriate rehef under

the RJA, N.C.G.S. § 15A-1335, and/or the United States Constitution, as

argued by Defendants-Appellants in the appeals at issue.

Respectfully submitted, this the 16th day of July, 2018.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

By: /s/ Carlos E. Mahoney

Carlos E. Mahoney

N.C. State Bar No. 26509

Glenn, Mills, Fisher & Mahoney, P.A.

P.O. Drawer 3865

Durham, North Carolina 27702

c.m.ahoncn<̂ g.m.fm-.l.aw.com.

Local Counsel for NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

- 31 -

N.C. R. App. P. 33(b) Certification:

I certify that all of the attorneys listed below have authorized me

to list their names on this document as if they had personally signed it.

By: /s/ Jin Hee Lee

Jin Hee Lee*

NY State Bar No. 3961158

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

(212) 965-2200

i.lee%.iaacKldf.org

Counsel for NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

By: /si W. Kerrel Murray

W. Kerrel Murray*

DC Bar No. 1048468

1444 I Street NW, 10th Floor

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

KMhrra^naacnidf'.org

Counsel for NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

*Motion for Admission Pro Hac Vice Pending

- 32 -

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that, on July 16, 2018, I served a copy of the

foregoing Brief of Amicus Curiae NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc. in Support of Defendant-Appellants, by

electronic means upon the following counsel of record for the parties:

Danielle Marquis Elder

Special Deputy Attorney General

North Carolina Dep't of Justice

P.O. Box 629

Raleigh, NC 27602

dmarquis@ncdol.gov

Counsel for State of NC

Jonathan P. Babb

Special Deputy Attorney General

North Carohna Dep’t of Justice

P.O. Box 629

Raleigh, NC 27602

ibabh@ncdoj.gov

Counsel for State of NC

Cassandra Stubbs

ACLU Capital Punishment

Project

201 West Main Street, Suite 402

Durham, NC 27701

cstubbs@aclu.org

Counsel for Defendant Robinson

David Weiss

Center for Death Penalty

Litigation, Inc.

123 W. Main Street, Suite 700

Durham, NC 27701

dcweiss@cdpl.org

Counsel for Defendant Robinson

Donald H. Beskind

Duke University School of Law

Box 90360

Durham, NC 27708

beskind@Iaw.dqkfc.edu

Counsel for Defendant Robinson

Shelagh R. Kenney

Center for Death Penalty

Litigation, Inc.

123 W. Main Street, Suite 700

Durham, NC 27701

she).agh@cdp]. org

Counsel for Defendant Walters

mailto:dmarquis@ncdol.gov

mailto:ibabh@ncdoj.gov

mailto:cstubbs@aclu.org

mailto:dcweiss@cdpl.org

mailto:beskind@Iaw.dqkfc.edu

33

Malcolm R. Hunter Jr.

P.O. Box 3018

Chapel Hill, NC 27515

t,yeh.unterC%-ahoo.com

Counsel for Defendant Walters

Jay H. Ferguson

Thomas, Ferguson & Mullins,

LLP

119 East Main Street

Durham, NC 27701

feyguson@tJYnatix>mev8.com

Counsel for Defendant Golphin

Kenneth J. Rose

809 Carohna Avenue

Durham, NC 27705

kenro8eattv@gm ail. com.

Counsel for Defendant Golphin

Gretchen M. Engel

Center for Death Penalty

Litigation, Inc.

123 W. Main Street, Suite 700

Durham, NC 27701

gretchen@cdpl.org.

Counsel for Defendant

Augustine

James E. Ferguson, II

Ferguson Chambers & Sumter

309 East Morehead Street, Suite

110

Charlotte, NC 28202

fer giet wo@aol. com

Counsel for Defendant

Augustine

This the 16th day of July, 2018.

/s/ Carlos E, Mahoney

Carlos E. Mahoney

Local Counsel for NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

mailto:gretchen@cdpl.org