School Board of the City of Charlottesville, Virginia v. Allen Brief on Behalf of Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1956

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. School Board of the City of Charlottesville, Virginia v. Allen Brief on Behalf of Appellees, 1956. 7e6f6155-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a2cd830a-e54c-44a3-95fb-cd3b838cfd1e/school-board-of-the-city-of-charlottesville-virginia-v-allen-brief-on-behalf-of-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

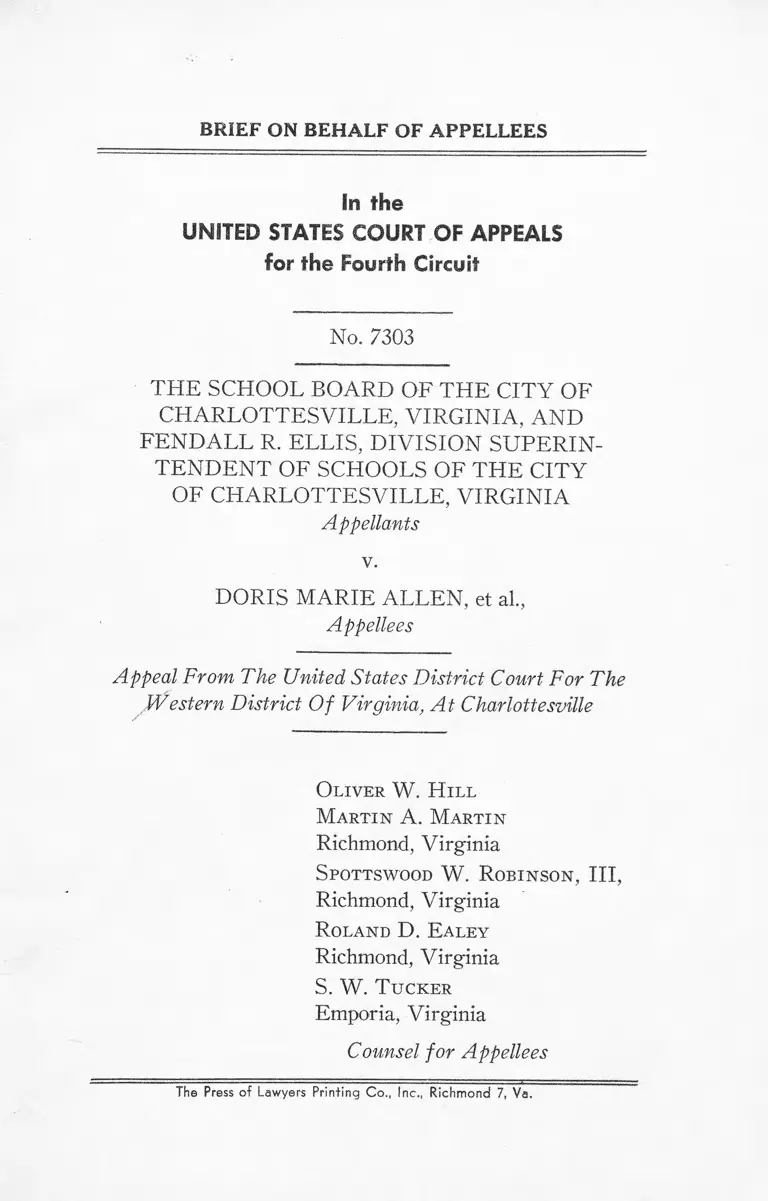

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLEES

In the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 7303

TH E SCHOOL BO ARD OF T H E C ITY OF

C H A R LO TTE SV ILLE , VIRG IN IA , AN D

FE N D A LL R. ELLIS, D IV ISIO N SU PERIN

TE N D E N T OF SCHOOLS OF TH E C ITY

OF C H A R LO TTE SV ILLE , V IR G IN IA

Appellants

v.

DORIS M AR IE ALLEN , et al.,

Appellees

Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Western District O f Virginia, A t Charlottesville

O liver W . H il l

M a r t in A. M a r t in

Richmond, Virginia

S pottswood W . R o b in so n , III,

Richmond, Virginia

R oland D . E a le y

Richmond, Virginia

S. W . T u ck er

Emporia, Virginia

Counsel for Appellees

The Press of Lawyers Printing Co., Inc., Richmond 7, Va.

SUBJECT INDEX

Questions Involved.................................................................. 1

Argument ................................................................................. 2

I. Appellant School Board And Division Superin

tendent Were Suable In The District Court.......... 2

A. The Eleventh Amendment Does Not Pre

clude This Action................................................. 2

B. The State Has Consented To Suit In A

Federal C ou rt....................................................... 4

II. Appellees Were Entitled To Injunctive Relief.... 6

III. There Were No Administrative Remedies That

Appellees Failed To Exhaust.................................... 7

IV. The District Court Did Not Abuse Its Discretion

In Making The Injunction Effective in Septem

ber, 1956 ..................................................................... 10

Conclusion .............................................................................. 12

TA B L E OF CITATIO N S

Cases

Bacon v. Rutland Railroad Co., 232 U. S. 134 (1914)... 8

Bank of United States v. Planters National Bank, 9

Wheat. 904 (1824)...................................................... ’ 5

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) 6

Brown v. Board o f Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) 11

Carson v. Board of Education, 227 F. 2d 789 (C. A

4th 1955) ............................................................................ 7

Casper v. Regional Agricultural Credit Corp,, 202

Minn. 433, 278 N. W . 896 (1938)............................ 4

Page

Page

Clemons v. Board of Education, (S. D. Ohio, April 11,

1956, No. 3440)............................... 11

Dunningtons v. Northwestern Turnpike Road, 6 Gratt.

160 (1849) ...................................................................... 5

Ex Parte Young, 209 U. S. 123 (1908)........................... 2

Federal Land Bank v. Priddy, 295 U. S. 229 (1935 )... 5

Ford Motor Company v. Department of Treasury, 323

U. S. 459 (1945)...................................... -...................... 5

Georgia Railroad & Banking Co. v. Redwine, 342 U. S.

299 (1952) ........................................................................ 2

Granville County Board of Education v. State Board of

Education, 106 N. C. 81, 10 S. E. 1002 (1890)........ 5

Great Northern Life Insurance Company v. Read, 322

U. S. 47 (1944 )................................................................ 5

Gross v. Kentucky Board of Managers, 105 Ky. 840,

49 S. W . 458, 43 L. R. A. 703 (1899)........................... 4

Hood v. Board of Trustees, 232 F. 2d 626 (C. A. 4th

1956) ................................................................................. 7

Interstate Construction Co. v. University of Idaho, 199

F 509 (1912).................................................................... 6

Keifer & Keifer v. Reconstruction Finance Corp., 306

U. S. 381 (1939 )............................................................. 4

Kennecott Copper Corporation v. State Tax Commis

sioner, 327 U. S. 573 (1946).......................................... 5

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1939)............................. 8

McSwain v. County Board of Education, 138 F. Supp.

570 (E. D. Tenn. 1956)................................................... 11

O ’Neill v. Early, 208 F 2d 286 (C. A. 4th 1953).............. 3

Osborn v. Bank of United States, 9 Wheat. 738 (1824)...2

Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Kuykendall, 265

U. S. 196 (1924 )............................................................. 9

Packard Co. v. Palisades Interstate Park, 240 F 543 (S.

D. N. Y. 1916).................................................................. 5

Prout v. Starr, 188 U. S. 537 (1903)............................... 2

Railroad & Warehouse Commission v. Duluth Street

Railway Co., 273 U. S. 625 (1927)............................... 9

Reagan v. Farmers Loan & Trust Co., 154 U S 362

(1894) ............................................................................... 6

Shedd v. Board of Education, (S. D. W. Va. April 11,

1956, No. 833 )................................................................. ’ u

Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 25 F 2d 480 (S D

Ala. 1928) ........................................................................ 5

Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U. S. 378 (1932)................ 3

Stewart v. Thornton, 75 Va. 215 (1881)......................... 3

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33 (1915 )............................... 2

Young, Ex parte, 209 U. S. 123 (1908)........................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Authorities

Constitution of the United States, Eleventh Amendment 3

Constitution o f the United States, Fourteenth Amend

ment .................................................................... 3

Code of Virginia, 1950, Sec. 22-57................................. 2, 8

Code of Virginia, 1950, Sec. 22-94.................................... 5

Page

in the

u n it e d s t a t e s c o u r t o f a p p e a l s

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 7303

TH E SCHOOL BO ARD OF TH E C ITY OF

CH A R LO TTE SV ILLE , VIRG IN IA , AN D

FE N D A LL R. ELLIS, D IVISIO N SU PERIN

TE N D E N T OF SCHOOLS OF T H E C ITY

OF C H A R LO TTE SV ILLE , V IR G IN IA

Appellants

v.

DORIS M AR IE ALLEN , et al,

Appellees

Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Western District Of Virginia, A t Charlottesville

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLEES

QU ESTION S IN V O LVE D

Appellees submit that appellants’ contentions present for

consideration the f ollowing questions:

1. Were the appellant school board and division superin

tendent suable in the District Court?

2. Were appellees entitled to injunctive relief?

3. Were there administrative remedies provided by Sec

tion 22-57 of the Code of Virginia that appellees failed

to exhaust?

4. Did the District Court abuse its discretion in making

the injunction effective in September, 1956?

ARGU M EN T

I

A p p e l l a n t S chool B oard A nd D iv is io n

S u p e r in t e n d e n t W ere S u able I n

T h e D istr ic t C ourt

A. The Eleventh Amendment Does Not Preclude This

Action.

In a long line o f cases commencing with Osborn v. Bank

of United States, 9 Wheat. 738 (1824), the Supreme Court

has established the doctrine that actions to enjoin state

officers or agencies from activities under color o f their

official authority that violate the Federal Constitution and

the rights o f individuals secured thereby are not suits

against the state prohibited by either the Eleventh Amend

ment or the principle that a state cannot be sued without

its consent. See also Georgia Railroad & Banking Co. v.

Redwine, 342 U. S. 299 (1952) ; Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S.

33 (1915); Ex parte Young, 209 U. S. 123 (1908); Prout

v. Starr, 188 U. S. 537 (1903).

This is not an action seeking to affect property of the

state, or to impose or enforce a liability upon the state, or to

require affirmative official action in the performance of a

state function. Cf. O’Neill v. Early, 208 F. 2d 286 (C. A.

4th 1953). It seeks merely to require the appellants to desist

from activities violative of the Fourteenth Amendment. To

this the Eleventh Amendment imposes no barrier. “ The

applicable principle is that where state officials, purporting

to act under state authority, invade rights secured by the

Federal Constitution, they are subject to the process of the

Federal courts in order that the persons injured may have

appropriate relief.” Sterling v. Constantin, 287 IJ. S. 378,

393 (1932).

Appellants would confine the operation of these princi

ples to suits against individual members of a school board,

or against a division superintendent as an individual. This

suggestion ignores the fact that it is the character of the

function soug'ht to be enjoined, rather than the manner in

which the defendant is sued, that is the important considera

tion. And the suggestion is entirely impractical. Appellees

could not obtain effective relief without enjoining appellants

in the exercise of their official authority. Obviously, an in

junction against activities unconnected with their school

functions would be valueless. Indeed, since by statute the

school board is a corporation, it is not apparent how it

could be enjoined except when sued as such. See Stewart v.

Thornton, 75 Va. 215 (1881).

The limitation suggested by appellants does not appear

to be made in the cases. In Ex parte Young, supra, where a

similar argument was made, the Court said (209 U. S. at

159-160):

[ 4 ]

“ The answer to all this is the same as made in every

case where an official claims to be acting under the

authority of the state. The act to be enforced is

alleged to be unconstitutional; and if it be so, the use

of the name of the state to enforce an unconstitutional

act to the injury o f complainants is a proceeding with

out the authority of, and one which does not affect, the

state in its sovereign or governmental capacity. It is

simply an illegal act upon the part o f a state official in

attempting, by the use of the name of the state, to en

force a legislative enactment which is void because

unconstitutional. If the act which the state attorney

general seeks to enforce be a violation of the Federal

Constitution, the officer, in proceeding under such en

actment, comes into conflict with the superior authority

of that Constitution, and he is in that case stripped of

his official or representative character and is subjected

in his person to the consequences of his individual con

duct. The state has no power to impart to him any

immunity from responsibility to the supreme authority

of the United States.”

B. The State Has Consented To Suit In A Federal Court.

If appellees’ position in the preceding section o f the argu

ment is sustained, the presence or absence of state consent

to this action is immaterial.

There is authority for the conclusion that power to sue

the school board may be implied from the grant of corporate

existence alone. Keifer & Keifer v. Reconstruction Finance

Corp., 306 U. S. 381 (1939) ; Casper v. Regional Agricul

tural Credit Corp., 202 Minn. 433, 278 N. W . 896 (1938) ;

Gross v. Kentucky Board of Managers, 105 Ky. 840, 49 S.

[ 5 ]

W . 458, 43 L. R. A. 703 (1899). But any doubt in this

connection is put to rest by the provision o f Section 22-94

of the Code of Virginia that the appellant school board

“ may sue and be sued” .

This limitless waiver of immunity seems clearly to em

brace litigation of the type here involved. See Federal Land

Bank v. Priddy, 295 U. S. 229 (1935); Packard Co. v.

Palisades Interstate Park, 240 F. 543 (S. D. N. Y. 1916) ;

Dunningtons v. Northwestern Turnpike Road, 6 Gratt. 160

(1849); Granville County Board of Education v. State

Board of Education, 106 N. C. 81, 10 S. E. 1002 (1890). It

would appear that Virginia has stripped herself of her

sovereign character as respects the activities o f school

boards. See Federal Land Bank v. Priddy, supra; Bank of

United States v. Planters National Bank, 9 Wheat. 904

(1824 ); Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 25 F. 2d 480

(S. D. Ala. 1928).

There are cases holding that an express statutory waiver

of immunity to suit does not extend to suits in Federal

courts. See Great Northern Life Insurance Company v.

Read, 322 US 47 (1944 ); Ford Motor Company v. Depart

ment of Treasury, 323 US 459 (1945); Kennecott Copper

Corporation v. State Tax Commissioner, 327 US 573

(1946). Cf. O’Neill v. Early, supra. In each of these cases,

however, the courts were dealing “ with the sovereign ex

emption from judicial interference in the vital field of

financial administration,” Great Northern Life Insurance

Co. v. Read, supra, 322 U. S. at 54, where a dear declara

tion of the state’s intention to submit its fiscal problems to

other courts than those of its own creation was deemed

necessary. It is submitted, however, that where, as here, the

Federal court is requested to perform its historic role as

[ 6 ]

protector o f individual constitutional rights, there is no

reason for a restricted construction o f an unrestricted grant

o f authority. C f.Reagan v. Farmers Loan & Trust Co., 154

U. S. 362 (1894) ; Interstate Construction Co. v. University

of Idaho, 199 F. 509 (D . Idaho 1912).

II

A ppellees W ere E n title d T o I n j u n c t iv e R e lie f

W e are met with the contention that the appellees have

failed to prove a case appropriate to a grant of injunctive

relief. The argument, as we understand it, is that the

appellees should have sought to attend particular schools.

Appellants have long maintained a practice and policy of

racial segregation in the public schools they control. Negro

children are thereby prohibited, simply because of their race,

from education in certain of the public schools. Insofar as

their admission to these schools is concerned, all other

considerations are immaterial. By the same token, white

students, solely because of their race, are denied admission

to certain other schools, irrespective of other factors ob

taining in the situation.

Whether appellants undertake to continue segregation by

or without the support of state law is immaterial for, in

either instance, rights secured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment are violated, and the practice is unconstitutional.

Brown v. Board of Education 347 U. S. 483 (1954). It is

equally clear that, just as the parties in Brown and its com

panion cases were held to be entitled to injunctive relief

from the segregation, so also are other individuals who in

other places have been subjected to a similar unconstitu

tional practice.

The right appellees assert in this case is the right to be

educated in some public schools determined by criteria other

than race. They assert simply their constitutional privilege

to freedom from racial classifications and distinctions in

assignments to schools and classes. Once race is eliminated

as a factor determinative of the school an appellee is to

attend, the constitutional issue is resolved, and determina

tion of the particular school he might in fact attend would

result from the operation of educationally significant fac

tors within the competency of the school authorities to

prescribe and apply.

It is not appellees’ prerogative to define or prescribe the

criteria to be employed to determine the particular schools

that particular pupils are to attend. This is and remains to be

the function of school authorities so long as the limits set

by the Constitution are observed. But until those criteria

are formulated and applied, no student can know what

school he is to attend. Here the school authorities ignored

the request for reorganization of the schools on a nonsegre-

gated basis, and it would seem clear that they cannot now

profit by their own failure of duty.

I l l

T h ere W ere No A d m in is t r a t iv e R em edies

T h a t A ppellees F a iled T o E x h a u s t

It is unnecessary for the appellees to claim immunity

from the operation of the rule requiring the exhaustion of

administrative remedies before resort to the courts. See

Carson v. Board of Education, 227 F. 2d 789 (C. A. 4th

1955); Hood v. Board of Trustees, 232 F. 2d 626 (C. A.

4th 1956). For the only remedy to which appellants refer

[ 8 ]

is that specified by Section 22-57 of the Code of Virginia of

1950, and it seems clear that the proceedings there provided

do not bring this case within the requirement of the ex

haustion rule.

Prior to instituting suit, appellees submitted to appellant

school board and division superintendent a written petition

setting forth their grievance and requesting corrective

action. Certainly this satisfied the first step specified by

Section 22-57. The second step— that appellees did not pur

sue— consists in an appeal to a court. Appellees submit

that the latter procedure is judicial in character, and that

they were not bound to follow it.

It is well settled that a party claiming deprivation of

his constitutional rights may resort to a Federal court with

out first exhausting the judicial remedies provided by the

state. Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1939); Railroad &

Warehouse Commission v. Duluth Street Railway Co., 273

U. S. 625 (1927); Bacon v. Rutland Railroad Co., 232 U.

S. 134 (1914).

The appeal provided by Section 22-57 seems to be

judicial in character. The tribunal is “ the circuit court of

the county or corporation court of the city or the judge

thereof in vacation.” This tribunal ordinarily exercises only

judicial functions. Presumbly, it lacks authority to exercise

any other unless that authority is expressly conferred. The

fact that the body in which the remedy is afforded is a

court is obviously of great significance.

The statute simply authorizes the court to “ decide finally

all questions at issue,” and provides that “ the action of the

school board on questions of discretion shall be final unless

the board has exceeded its authority or has acted corruptly.”

The remedy is judicial where the reviewing agency does not

possess the power to substitute such order as in its opinion

the administrative agency should have made in the first in

stance. Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Kuykendall,

265 U. S. 196 (1924). Here the remedy simply enables the

court to exonerate the complaining party from action that

exceeds the law. Bacon v. Rutland Railroad Co., supra.

Even doubt as to the validity of the conclusions herein

asserted would not subject appellees to the necessity of

pursuing this remedy. At the very least, the character o f the

remedy— as administrative or judicial— is highly doubtful.

I f the remedy is indeed judicial and appellees had pursued

it, the conclusions of the state court would be binding upon

them, and the possibility of their decision by a Federal Dis

trict Court eliminated. A party is not required to sacrifice

his constitutional privilege of hearing and decision in a

Federal court by being subjected to a state remedy the

nature of which is debatable. As Mr. Justice Holmes stated

in Railroad & Warehouse Commission v. Duluth Street

Railway Co., supra (273 U. S. at 628) :

“ . . . it must be remembered that the requirement that

state remedies be exhausted is not a fundamental prin

ciple of substantive law but merely a requirement of

convenience or comity. Where as here a constitutional

right is insisted on, we think it would be unjust to put

the plaintiff to the chances of possibly reaching the de

sired result by an appeal to the state court, when at

least it is possible that, as we have said, it would find

itself too late if it afterwards went to the district court

o f the United States.”

[ 10 ]

IV

T h e D istr ic t C ourt D id N ot A buse Its

D iscretio n I n M a k in g T h e I n j u n c t io n E ffective

I n S epte m b e r , 1956.

Appellants complain of the action of the District Court

in making' its injunction effective in September, 1956. W e

submit that it was eminently correct in so doing*.

The basis for the action of the Court in this connection is

well stated in its opinion (Appellants’ App. 22) :

“ It only remains to be determined as to the time when

an injunction restraining defendants from maintaining

segregated schools shall become effective. The original

decision of the Supreme Court was over two years

ago. Its supplementary opinion directing that a prompt

and reasonable start be made toward desegregation

was handed down fourteen months ago. Defendants

admit that they have taken no steps toward compliance

with the ruling of the Supreme Court. They have not

requested that the effective date of any action taken by

this court be deferred to some future time or some

future school year. They have not asked for any ex

tension of time within which to embark on a program

of desegregation. On the contrary the defense has been

one of seeking to avoid any integration of the schools

in either the near or distant future. They have given

no evidence o f any willingness to comply with the rul

ing of the Supreme Court at any time. In view of all

these circumstances it is not seen where any good can

be accomplished by deferring the effective date o f the

court’s decree beyond the beginning of the school

session opening this Autumn. Even though the time be

limited it is not impossible that, at the school session

opening in September of this year, a reasonable start

be made toward complying with the decision of the

Supreme Court.”

Although in Brown v. Board of Education, !349 U. S. 294

(1955), the Supreme Court recognized that “ full implemen

tation of these constitutional principles may require solution

o f varied school problems” , it emphasized that the process

of solution of these problems must not diminish the con

stitutional rights involved. It said (Id. at 300) :

“ While giving weight to these public and private con

siderations, the courts will require that the defendants

make a prompt and reasonable start toward full com

pliance with our May 17, 1954, ruling. Once such a

start has been made, the courts may find that additional

time is necessary to carry out the ruling in an effective

manner. The burden rests upon the defendants to es

tablish that such time is necessary in the public interest

and is consistent with good faith compliance at the

earliest practicable date.”

W e submit that the District Court might properly in the

circumstances of this case specify an effective date for the

operation of its decree. See McSwain v. County Board of

Education, 138 F. Supp. 570 (E. D. Tenn. 1956); Clemons

v. Board of Education, (S. D. Ohio, April 11, 1956, No.

3440); Shedd v. Board of Education, (S. D. W . Va., April

11, 1956, No. 833).

[ 12 ]

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated herein, it is respectfully submitted

that the judgment appealed from should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

O liver W . H il l

M a r t in A. M a r t in

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond, Virginia

S pottswood W . R o b in so n , II I ,

623 North Third Street

Richmond, Virginia

R oland D. E a le y

420 North First Street

Richmond, Virginia

S. W. T u ck er

111 East Atlantic

Emporia, Virginia

Counsel for Appellees

■