Hutto v. Jones Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Eight Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hutto v. Jones Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Eight Circuit, 1985. 8ab2f3a3-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a31d7630-6780-47e5-a912-0c4ce9bfabc7/hutto-v-jones-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-eight-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

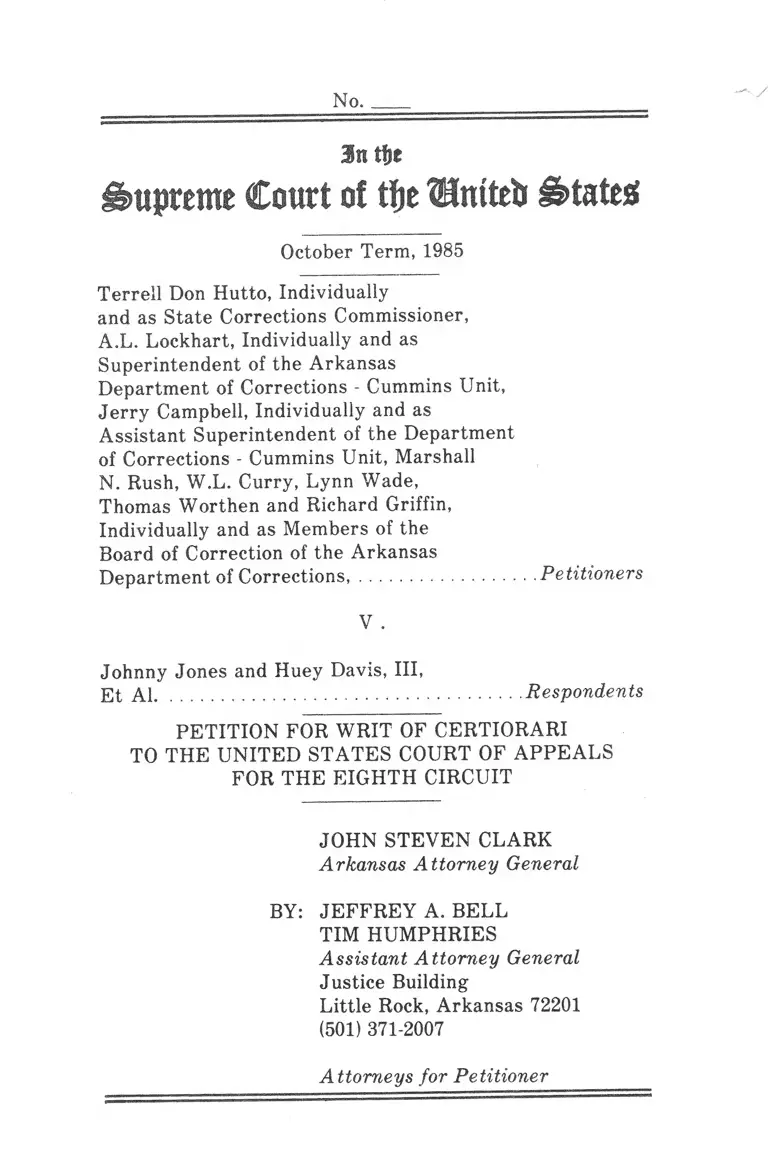

No.

3 n tfje

Supreme Court of tfje ©mteh States

October Term, 1985

Terrell Don Hutto, Individually

and as State Corrections Commissioner,

A.L. Lockhart, Individually and as

Superintendent of the Arkansas

Department of Corrections - Cummins Unit,

Je rry Campbell, Individually and as

Assistant Superintendent of the Department

of Corrections - Cummins Unit, Marshall

N. Rush, W.L. Curry, Lynn Wade,

Thomas Worthen and Richard Griffin,

Individually and as Members of the

Board of Correction of the Arkansas

Department of C orrections,.................................. Petitioners

V .

Johnny Jones and Huey Davis, III,

E t A1........................................................................Respondents

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

JOHN STEVEN CLARK

Arkansas A ttorney General

BY: JEFFREY A. BELL

TIM HUMPHRIES

Assistant A ttorney General

Justice Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

(501) 371-2007

Attorneys for Petitioner

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I. WHETHER THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT ERRED IN

FINDING THAT THE DISTRICT COURT WAS

CORRECT IN CERTIFYING THIS CASE AS A

CLASS ACTION, IN REFUSING TO DECERTIFY

THE CLASS, AND IN THE SCOPE AND BREADTH

GIVEN TO THE CERTIFIED CLASS.

II. WHETHER THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT ERRED IN ITS

INTERPRETATION OF GRIGGS V. D U KE POW ER

CO. AND IN ITS AFFIRMANCE OF THE DISTRICT

COURT’S APPLICATION OF A DISPARATE

IMPACT THEORY TO THE FACTS OF THIS CASE.

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.............................................. iii

OPINIONS B ELO W .......................................................... 1

JURISDICTION .................................................................. 2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED ........................................ 2

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ......................................... 3

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W R IT ...................... 5

I. THIS COURT SHOULD GRANT CERTIORARI

BECAUSE THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT’S RULING

THAT THE DISTRICT COURT WAS CORRECT

IN CERTIFYING THE CASE AS A CLASS

ACTION, IN REFUSING TO DECERTIFY THE

CLASS, AND IN THE SCOPE AND

BREADTH GIVEN TO THE CERTIFIED

CLASS IS IN CONTRADICTION TO THIS

COURT’S DECISIONS REGARDING CLASS

ACTIO N S........ ............................................................ 5

II. THIS COURT SHOULD GRANT CERTIORARI IN

THIS CASE BECAUSE THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

HAS IMPROPERLY INTERPRETED THIS

COURT’S DECISIONS IN AFFIRMING THE

DISTRICT COURT’S ERRONEOUS

APPLICATION OF THE LAW TO THE FACTS

OF THE CASE ........................................................... 10

CONCLUSION .................................... 13

APPENDIX A ........................................................ A-l

APPENDIX B ...................................... B-l

I ll

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES: Page

American Pipe and Construction Company

v. Utah, 414 U.S. 538 at 553 (1974)............ ...................8

East Texas Motor Freight Systems, Inc.

v. Rodriquez, 431 U.S. 395 at

405 (1975) ............................................................................6

General Telephone Co. v. Falcon,

457 U.S. 147 (1982)............ ..........................5 ,6 ,7 ,8 ,9 ,1 0

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 at

430-431 (1971)...................................................... .. . .11, 12

Harris v. Ford Motor Co., 651 F.2d 609

at 611 (8th Cir. 1981)............................... 12

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324 at

335 (1977) ........................................ 10

Jones and Davis v. Hutto, U.S.D.C. No.

PB-74-C-173 (Memorandum Opinion and

Order entered August 29, 1983)..................................... 2

Jones and Davis v. Hutto, et al

763 F. 2d 979 (8th Cir. 1985) ............................................1

Schlesinger v. Reservists Committee

to Stop the War, 418 U.S. 208 at

216 (1971) ...................... 6

STATUTES:

28 U.S.C. §1254 (1) 2

iv

42 U.S.C. §1981 ......................................................................... 3

42 U.S.C. §1983 .............................................. 3

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(a) .......................... 2,3,10

PROCEDURAL RULES:

F.R.C.P. 2 3 ........ ............................................................5, 6, 8, 9

N o .___

i n tfje

Supreme Court of tjje ®mte& States

October Term, 1985

Terrell Don Hutto, Individually

and as State Corrections Commissioner,

A.L. Lockhart, Individually and as

Superintendent of the Arkansas

Department of Corrections - Cummins Unit,

Jerry Campbell, Individually and as

Assistant Superintendent of the Department

of Corrections - Cummins Unit, Marshall

N. Rush, W.L. Curry, Lynn Wade,

Thomas Worthen and Richard Griffin,

Individually and as Members of the

Board of Correction of the Arkansas

Department of C orrections,.................................. Petitioners

V .

Johnny Jones and Huey Davis, III,

E t A1........................................................................Respondents

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

The above-captioned Petitioners hereby petition for a

writ of certiorari to review the Judgment of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit in this case.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals,

filed on June 5, 1985, is reported at 763 F.2d 979 (8th Cir.

1985), and is reprinted as Appendix A to this Petition. The

2

Memorandum Opinion and Order of the United States

District Court is unreported, and is reprinted as Appendix

B to this Petition. It is case number PB-74-C-173.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was filed on

June 5, 1985. The Court of Appeals entered an Order on

July 1, 1985, in which it stayed the issuance of its mandate

for a period of thirty (30) days, until July 31, 1985. On July

24, 1985, Petitioners filed a Motion requesting the Court of

Appeals to extend said Stay for an additional twenty (20)

days, until August 20, 1985. This Motion was granted on July

31, 1985. No Petition for Rehearing was filed in this case.

The jurisdiction of this Court is envoked under 28 U.S.C.

§1254(1). The parties listed in the caption to this proceeding

are all the parties involved in the case before the Eighth

Circuit Court of Appeals.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

42 U.S.C. §2000e, et seq. (Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964) provides in pertinent part:

2Q00e-2(a). It shall be an unlawful employment

practice for an employer -

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any

individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any

individual with respect to his compensation, terms,

conditions, or privileges of employment, because of

such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin; or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or

applicants for employment in any way which would

deprive or tend to deprive any individual of

employment opportunities or otherwise adversely

affect his status as an employee, because of such

individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin.

3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On May 8, 1974, Johnny Jones and Huey Davis, III,

filed this case as an individual and class action race

discrimination suit pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §§1981 and 1983,

and 42 U.S.C. §2000(e) et seq. (Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964). The persons listed as Petitioners in this

Petition for W rit of Certiorari were named as Defendants in

the Complaint. The Complaint sought declaratory and

injunctive relief to restrain the Arkansas Department of

Correction from engaging in alleged discriminatory

employment practices. The Complaint further prayed for

back pay for the individual and class Plaintiffs, and for other

monetary damages.

The District Court conditionally certified the case as a

class action by an Order dated September 27, 1976. By

subsequent Order dated January 18, 1982, the Court

defined the class as follows:

All Black persons who have been employed by the

defendant Department of Correction at any time

from May 8, 1971 to the date of the commencement

of the trial, who are or have been limited, classified,

restricted, discharged or discriminated against by

the defendants with respect to promotions,

assignments, training or who have been otherwise

deprived of employment opportunities related to

said factors because of their race or color.

By Order dated March 22, 1982, the District Court

subsequently amended the portion of its class designation

reading “to the date of the commencement of the trial” to

read “to the date of judgment, if any, entered on the

question of liability.” (See Appendix A at A-2, A-3;

Appendix B at B-2).

The District Court determined that the case would be

tried in a bifurcated manner, the first phase to deal solely

4

with the issue of liability. Following extensive discovery in

pre-trial proceedings, the liability phase of the case was

tried to the District Court over a period of fifteen (15) days

between March 29, 1982 and April 28, 1982. The District

Court issued its Opinion on August 29, 1983, in which it

found that the named Defendants had not discriminated in

initial hiring of blacks, but had unlawfully discriminated in

job placement, promotions, and other employment

practices. (See Appendix B at B-16).

The Petitioners herein appealed the decision of the

District Court to the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, on

the following grounds: that the District Court abused its

discretion by certifying the case as a class action, or by

failing to decertify the class at some point in the

proceedings, because the Plaintiffs had failed to comply

with the requirements of Rule 23; that the District Court

erred by certifying a class which was entirely too broad, and

by failing to narrow said class at some point in the

proceedings, all in contradiction to current law pertaining

to across-the-board classes as stated by this Court; that the

District Court erred at law by applying the wrong legal

standard to the facts in determining whether racial

discrimination had occurred; that the District Court was

clearly erroneous in its finding of discrimination because

Plaintiffs had failed to prove a pattern or practice of

discrimination. The Respondents herein filed a eross-appeal,

claiming that black applicants who were not hired by the

Department of Correction should have been included in the

certified class by the District Court. On June 5, 1985, the

Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals filed an Opinion in which it

affirmed the judgment of the District Court in all respects.

(See Appendix A).

5

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I,

THIS COURT SHOULD GRANT CERTIORARI

BECAUSE THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT’S RULING THAT

TH E D IS T R IC T COURT W AS CO RRECT IN

CERTIFYING THE CASE AS A CLASS ACTION, IN

REFUSING TO DECERTIFY THE CLASS, AND IN THE

SCOPE AND BREADTH GIVEN TO THE CERTIFIED

CLASS IS IN CONTRADICTION TO THIS COURT’S

DECISIONS REGARDING CLASS ACTIONS.

An individual plaintiff seeking to maintain a class

action under Title VII has the burden of establishing that

the case is certifiable as a class action and that he meets the

requirements of numerosity, commonality, typicality, and

adequacy of representation specified in F.R.C.P. 23(a).

General Telephone Co. v. Falcon, 457 U.S. 147 at 157 (1982).

“[A]ctual, not presumed, conformity with Rule 23(a)

remains, . . . indispensable.” Id. at 160. The trial court is

obliged to subject the proposed class to “rigorous analysis”

and “to evaluate carefully the legitimacy of the named

plaintiffs plea that he is a proper class representative

under Rule 23(a).” Id at 160-161.

The District Court certified this case as a class action

without a hearing, and subsequently defined an across-the-

board class in an order denying Petitioners’ Motion to

Decertify the Class. No hearing was conducted on

decertifica tion . The only evidence p resen ted by

Respondents in support of class certification was a two page

affidavit by one of their attorneys, which simply parroted

the provisions of Rule 23(a) itself. It is error for a trial court

to presume that a plaintiffs claim is typical of other claims

“without any specific presentation identifying the questions

of law or fact that were common to the claims . . . of the

members of the class he sought to represent.” Falcon,

supra, 457 U.S. at 158.

6

The Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals held that the

District Court did not abuse its discretion in certifying this

case as a class action without conducting a hearing to

determine whether Plaintiffs met the requirements of Rule

23. The Court further held that the District Court did not

abuse its discretion in failing to decertify the case as a class

action at a later point in the proceedings. (See Appendix A

at A-4). The District Court’s actions and the Eighth

Circuit’s holding affirming such actions violate this Court’s

previous rulings in Falcon and other cases.

F.R.C.P. 23(a) requires that a plaintiff demonstrate: (1)

that the proposed class is too numerous to join its members

as parties; (2) that plaintiffs claims are common in law or

fact to those in the class; (3) that plaintiffs claims are typical

of absent class members; and (4) that plaintiff will

adequately represent the class. In essense, “a class

representative must be part of the class and possess the

same interest and suffer the same injury as class members.”

East Texas Motor Freight Systems, Inc. v. Roderiguez, 431

U.S. 395 at 405 (1975) quoting Schlesinger v. Reservists

Committee to Stop the War, 418 U.S. 208 at 216 (1971). The

Plaintiffs in this case were non-supervisory, security

officers at the Cummins Unit of the Arkansas Department

of Correction during a portion of the years 1973-1974, who

both resigned their employment. They asserted highly

individualized claims of promotional and treatm ent

discrimination. They have nothing in common with the class

allegations concerning Department of Correction practices

regarding hiring, discharge, non-security employees,

supervisory employees, present employees, employees who

preceded them, or employees employed at facilities other

than Cummins. Without any specific presentation by

Plaintiffs identifying questions of law or fact common to the

claims asserted on behalf of the proposed class members, it

was error for the District Court to certify the case as a

class action. The Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals contradicted

holdings of this Court in affirming said error. See Falcon,

supra, 457 U.S. at 158.

7

Just as Plaintiffs failed to show commonality to the

claims of the putative class, neither did they show that their

claims were typical. Plaintiffs offered no pre-trial evidence

that their claims were typical, other than the pleadings and

their attorney’s affidavit. Their testimony at trial indicated

that their grievances were highly individualized. Where the

Plaintiffs’ grievances are highly individualized and reflect

unique circumstances, the claims are not typical and no

class should be certified. As this Court stated in Falcon,

supra, 457 U.S. at 157:

Conceptually, there is a wide gap between (a) an

individual’s claim that he has been denied a

promotion on discriminatory grounds, and this

otherwise unsupported allegation that the company

has a policy of discrimination, and (b) the existence of

a class of persons who have suffered the same injury

as that individual, such that the individual’s claim

and the class claims will share common questions of

law or fact and that the individual’s claim will be

typical of the class claims.

Plaintiffs failed to bridge that gap in this case. The

testimony regarding discrimination in their particular

employment was insufficient to sustain the additional

inference that there was a pattern or practice of racial

discrimination in employment at the Department of

Correction which was motivated by discriminatory animus.

The Eighth Circuit erred in its affirmance of the District

Court’s continued certification of this case as a class action.

Plaintiffs also failed to show that they were adequate

class representatives. In order to adequately represent the

class, the class representative must have knowledge of and

be familiar with the work environment of, the nature of the

jobs held by, and the practices affecting the class members.

Plaintiffs introduced no evidence prior to trial to show that

they met this requirement. Furthermore, the evidence at

trial showed that Plaintiffs had made only casual attem pts

to familiarize themselves with employment practices and

8

policies of the Department of Correction since 1974 or to

follow the progress of the lawsuit, leaving virtually all the

decisions to the discretion of their attorneys. Again, the

Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals erred in affirming the

District Court’s certification of this case as a class action, in

light of Plaintiffs’ failure to comply with Rule 23.

The principle purpose of the class action is to advance

the efficiency and economy of litigation. Falcon, supra, 457

U.S. at 155. The class action device is especially appropriate

when the issues are common to all class members and when

they turn on questions of law which are applicable in the

same manner to each class member. Id. at 154. Under such

circumstances a class action would serve its purpose by

allowing issues affecting potentially every class member to

be litigated in an economical fashion. Id. Testimony at trial

indicated that the principal purpose of the class action

device as stated in Falcon was not advanced in this case.

There were not issues of fact or law common to the class.

The individual Plaintiffs’ claims were highly individualized

and particular to their situation, and the other witness

advanced a wide range of complaints covering virtually

every aspect of the Department of Correction. Maintenance

of this case as a class action did not advance the “efficiency

and economy of litigation which is a principal purpose of the

procedure.” Falcon, supra, 457 U.S. at 159, quoting

American Pipe and Construction Company v. Utah, 414

U.S. 538 at 553 (1974).

The District Court abused its discretion in certifying

this case as a class action, and in failing to decertify the case

as a class action at some point during the pendency of the

proceedings. The Eighth Circuit’s affirmance of the actions

of the District Court violates the previous holdings of this

Court. As stated in Falcon, supra, the initial designation of a

case as a class action is “inherently tentative,” and even

after a judge has certified a case as a class action, the judge

is free to decertify the class or to modify it based on the

9

evidence produced in the litigation. See Falcon, supra, 457

U.S. at 160. By initially certifying this case as a class action

without requiring the Plaintiffs to make a showing of

compliance with Rule 23, the District Court required

Petitioners to defend against a scatter gun approach to the

case by Plaintiffs. Additionally, during the pendency of the

trial the Plaintiffs failed to show any commonality or

typicality with the putitive class, thereby making it

imperative upon the Court to decertify the class which it had

earlier certified. The Eighth Circuit’s affirmance of the District

Court’s actions is in contradiction to the law on class actions set

forth by this Court.

Finally, even if this case were correctly certified as a

class action, the scope of the class as certified by the

District Court was an entirely too broad across-the-board

class, of the sort condemned by this Court in the Falcon

case. This Court noted in Falcon that even though suits

alleging racial discrimination are often by their very nature

situations involving class wide wrongs, simply because a

plaintiff alleges that such discrimination has occurred

“neither determines whether a class action may be

maintained in accordance with Rule 23 nor defines the class

that may be certified.” Falcon, supra, 457 U.S. at 157. In its

opinion in this case, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals

stated:

Finally, while the evidence supporting the finding of

liability may have been less substantial with respect to

some of the ADC facilities than others, that does not

support a finding that the class was over broad. At the

remedial phase of this lawsuit the District Court can

cure any over broadness of the class which might exist

by carefully scrutinizing the evidence then presented in

light of the evidence already adduced, and tailoring the

remedy as such that only those harmed by the

discriminatory practices will be compensated. (See

Appendix A at A-4).

10

The Court of Appeals improperly interpreted this

Court’s decision in the Falcon case by its upholding of the

across-the-board class certification. This error is not cured

by the statem ent tha t the trial court can remedy any over

broadness of the class by scrutinizing the evidence

presented at the damages phase of the trial and tailoring its

remedy in conformance therewith. This approach works an

unfair prejudice against Petitioners and violates the law

established by this Court. A claim presented by two

individuals who were non-supervisory, security personnel

at one unit of the prison system for a period of one year

before voluntarily resigning, is not sufficient to represent a

class alleged to contain persons with claims regarding

hiring, discharge, non-security positions, supervisory

positions, present employees, preceding employees, or

employees employed at other units. The Eighth Circuit

violated this Court’s rulings when it affirmed the District

Court’s across-the-board class certification.

II.

THIS COURT SHOULD GRANT CERTIORARI IN

THIS CASE BECAUSE THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT HAS

IM PR O PER LY IN T E R P R E T E D TH IS CO URT’S

DECISIONS IN AFFIRMING THE DISTRICT COURT’S

ERRONEOUS APPLICATION OF THE LAW TO THE

FACTS OF THE CASE.

A disparate treatm ent claim brought under Title VII

turns on the basic issue of whether the employer

intentionally treated some persons less favorably than

others because of their race, color, religion, sex or national

origin. Proof of discriminatory motive is critical in a

disparate treatm ent case. International Brotherhood of

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 at 335, n. 15 (1977).

Title VII also prohibits employment practices that are

neutral on their face but that in fact fall more harshly on one

group than another, and have a disproportionate or

disparate impact on tha t group, which cannot be justified by

11

business necessity. Proof of discriminatory motive is not

required under a disparate impact theory. Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 at 430-431 (1971).

In the case below, Respondents presented allegations

and testimony contending tha t Petitioners intentionally

treated blacks different than whites in various aspects of

the employment practices at the Department of Correction.

In its Memorandum Opinion and Order the District Court

discussed numerous findings related to alleged purposeful

acts of Department of Correction authorities, such as

subjective job assignments, shift assignments, and

promotional decisions. Although the Court’s findings dealt

with issues which require some purposeful action on the

part of Respondents, the Court based its finding of

discrimination on a disparate impact analysis. For example,

the Court found that the “subjectivity” of the wardens and

others who controlled the promotion process had a

disparate impact on blacks. The subjectivity of a

promotional, discharge, or other employment process,

which requires some purposeful or intentional activity on

behalf of the employer, should be considered under a

disparate treatm ent analysis rather than a disparate impact

analysis.

In its Opinion, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals

found that the District Court had properly employed the

disparate impact model of analysis established in the Griggs

case in rendering its decision regarding the class claim in

this case. As such, the Court of Appeals has erroneously

and improperly applied the Griggs decision. The Griggs

case dealt with a typical disparate impact situation, where

an employer was requiring an objective criteria of obtaining

a high school education or passing a standardized general

intelligence test as a condition of obtaining certain jobs. The

Griggs analysis is not appropriate when considering a

subjective promotional or other process affecting the

conditions of employment.

12

The Eighth Circuit has previously recognized that the

Griggs analysis is not appropriate when considering an

employer’s subjective employment practices. In Harris v.

Ford Motor Co., 651 F.2d 609 at 611 (8th Cir. 1981), the

Eighth Circuit rejected a contention that an employer’s

practice of making “subjective” decisions in discharging

employees for poor workmanship disproportionately

impacted on women. The court held that while non-objective

evaluation systems may be probative of intentional

discrimination, subjective decision making systems are not

the types of practices prohibited by the Griggs decision and

cannot form the foundation for a finding of discriminatory

impact under Griggs and its progeny.

By its opinion in the case at bar, the Court of Appeals

not only erroneously applied the Griggs decision but also its

own previous decision in the Harris case. The Court

justifies its analysis by characterizing the case at bar as an

"adverse impact ‘excessive subjectivity’ case,” and cites as

support for this characterization material from a leading

treatise on employment discrimination law. This is not an

adequate basis upon which to ignore the law established by

this Court in the Griggs decision.

The D is tric t C ourt engaged in a confusing

misapplication of the proper legal standard to the facts in

reaching its decision. The Court of Appeals affirmed the

District Court in its legal analysis, and in effect misapplied

the previous holdings of this Court as discussed above.

13

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, the Petition for W rit of

Certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

JOHN STEVEN CLARK

Arkansas A ttorney General

BY: JEFFREY A. BELL

TIM HUMPHRIES

Assistant A ttorney General

Justice Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

(501) 371-2007

Attorneys for Petitioner

14

A-l

APPENDIX A

United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

Nos. 83-2320 and 83-2370

Johnny Jones and Huey Davis, III, )

et al., )

)

Appellees/Cross-Appellants, )

v. )

) Appeals from the

) United States District

Terrell Don Hutto, Individually ) Court for the Eastern

and as State Corrections ) District of Arkansas.

Commissioner, A. L. Lockhart, )

Individually and as )

Superintendent of the Arkansas )

Department of Corrections — )

Cummins Unit, Jerry Campbell, )

Individually and as Assistant )

Superintendent of the Depart- )

ment of Corrections—Cummins )

Unit, Marshall N. Rush, W.L. )

Curry, Lynn Wade, Thomas )

Worthen and Richard Griffin, )

Individually and as members of the )

Board of Corrections of the )

Arkansas Department of )

Corrections, )

)

Appellants/Cross-Appellees. )

Submitted: April 10, 1985

Filed: June 5, 1985

A-2

Before ROSS and JOHN R. GIBSON, Circuit Judges, and

COLLINSON,* District Judge.

ROSS, Circuit Judge.

This case comes before the court on appeal by the

Arkansas Department of Corrections (hereinafter ADC) from i

the district court’s 1 finding of liability in an employment

discrimination class action suit filed by two former ADC

employees. Jurisdiction is premised on 28 U.S.C. §1291. For the

reasons stated herein we affirm.

FACTS

In May, 1974, two former employees of the ADC filed this

lawsuit against the ADC alleging that the Department

unlawfully discriminated against blacks in hiring, placement,

promotions, and other employment practices. In January, 1976,

the plaintiffs sought to have the case certified as a class action.

By an order dated January 18,1982, the district court certified

the class as follows:

All Black persons who have been employed by the

defendant Department of Corrections at any time from

May 8, 1971 to the date of the commencement of the

trial, who are or have been limited, classified, restricted,

discharged or discriminated against by the defendants

with respect to promotions, assignments, training or

who have been otherwise deprived of employment

opportunities related to said factors because of their

race or color. * 1

♦The HONORABLE WILLIAM R. COLLINSON, Senior Judge, United

States District Court for the Eastern and Western Districts of Missouri, sitting

by designation.

1

The Honorable Oren Harris, Senior United States District Judge for

the Eastern District of Arkansas.

A-3

Jones v. Hutto, No. PB-74-C-173 (E.D. Ark. January 18,

1982) (Order). 2

A fter extensive discovery, trial commenced on March

29,1982, and the case was tried over a period of fifteen days.

The record in this case is voluminous, containing almost

4,000 pages of transcript, several hundred exhibits, as well

as depositions. On August 29, 1983, the district court issued

a cogent opinion which copiously analyzed the abundant

evidence presented in this case. The court discerned that

the ADC had unlawfully discriminated against blacks in

placement, promotion, and other practices, but held there

was no unlawful discrimination in the ADC’s hiring

practices. This appeal and cross-appeal followed.

ISSUES

A. Appeal

On appeal the ADC raises three issues:

1. W hether the Court abused its discretion by failing

to decertify or narrow the class;

2. W hether the court was clearly erroneous in its

ultimate finding of discrimination; and

3. W hether the court applied the correct legal

standard to the evidence in this case.

B. Cross-Appeal

In their cross-appeal the plaintiffs claim that the

district court erred by failing to include black applicants

2

The district court subsequently amended the provision “to the date

of the commencement of the trial,” to read: “to the date of judgment, if

any, entered on the question of liability.” Jones v. Hutto, No. PB-74-C-173

(E.D. Ark. March 22, 1982) (Order).

A-4

who were denied employment in the class which was

certified.

DISCUSSION

A. Class Certification

The appellants claim that the district court should have

held a hearing to determine whether the plaintiffs’ claims

were sufficiently similar to those of the class members, and

to limit the scope of the class to include “only non-

supervisory security officers employed at the Cummins

Unit during the term of plaintiffs’ employment, who claim

the same type of discrimination * * * .” Appellants’ Brief at

8. The cross-appellants claim the court should have included

applicants in the class. We reject both claims.

The certification of a class under Rule 23 of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure may be overturned if the district

court abused its discretion in so certifying the class. See

Shapiro v. M idwest Rubber Reclaiming Co., 626 F.2d 63, 71

(8th Cir. 1980). Nothing in the record in this case indicates

that the court abused its discretion in certifying the class as

it did. Furtherm ore, the district court had sufficient

material before it to determine the nature of the allegations,

and rule on compliance with Rule 23, without holding a

formal evidentiary hearing. See Walker v. World Tire

Corp., 563 F.2d 918, 921 (8th Cir. 1977). Finally, while the

evidence supporting the finding of liability may have been

less substantial with respect to some of the ADC facilities

than others, tha t does not support a finding that the class

was overbroad. At the remedial phase of this lawsuit the

district court can cure any overbroadness of the class which

might exist by carefully scrutinizing the evidence then

presented in light of the evidence already adduced, and

tailoring the remedy such that only those harmed by the

discriminatory practices will be compensated.

A-5

B. Substantive Finding of Discrimination

The appellants claim that the district court erred in its

factual findings which were relied upon to support the

ultimate finding of liability. To support their position the

ADC discusses at length the evidence in the record which

demonstrates that certain black individuals were in fact

promoted. In our opinion, the fact that not every black was

discriminated against, or that there were exceptions, does

not militate against the district court’s finding of liability in

this case. See Bell v. Bolger, 708 F.2d 1312, 1318 (8th Cir.

1983). The district court rejected this argument on the same

basis as we reject it:

The defendants attempted to demonstrate that

blacks have progressed in the Department of

Correction and that they are not underrepresented in

supervisory positions. First, an employer cannot

respond to a classwide showing of exclusion by

identifying a few blacks who progressed in the system.

The plaintiffs have readily conceded that this is not a

situation where no black had ever been promoted.

Rather, the discrimination lies not in total exclusion but

rather in the Department’s disproportionate allocation

of promotions to whites. [That] * * * blacks * * * have

progressed through the system hardly demonstrate^]

that no discrimination has existed.

Jones v. Hutto, No. PB-74-173, Slip op. at 27 (E.D. Ark.

August 30, 1983).

In this case both parties had the opportunity to present

evidence to the district court regarding their respective

positions. The district court had the opportunity to observe

the demeanor of the witnesses and weigh the conflicting

evidence. There is substantial evidence in the record to

support the court’s factual determinations which formed

the basis for the finding of liability. The Supreme Court

recently reaffirmed that the clearly erroneous standard

applies in cases such as this, see Anderson v. City of

A-6

Bessemer City, 105 S.Ct. 1504,1511-12 (1985), and the record

before us establishes tha t the district court’s findings are

not clearly erroneous. Id. See also Tolliver v. Yeargan, 728

F.2d 1076 (8th Cir. 1984). 3

C. Proper Legal Standard

The ADC’s final allegation is that the district court

erroneously based its finding of liability as to the class on a

disparate impact model while the testimony raised issues of

disparate treatm ent.

As to the named plaintiffs’ claims of discrimination, the

court clearly employed the disparate treatm ent analysis of

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 802 (1973).

It is equally clear that the court employed the disparate

impact model of analysis established in Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 431-32 (1971), to the class claim in

this case. This, however, was not error.

This case presented what is commonly referred to as an

“adverse impact ‘excessive subjectivity’ case”, where an

employer’s excessively subjective selection process results

in an adverse impact upon a protected group. See Schlei &

Grossman, Em ploym ent Discrimination Law 1288 (2d ed.

1983). “However characterized, d isparate trea tm ent

3

The ADC also takes issue with the district court’s discussion of past

litigation involving segregation of inmates and prison conditions in

general at the ADC. See Finney v. Mabry, 534 F.Supp. 1026 (E.D. Ark.

1982); Finney v. Mabry, 528 F.Supp. 567 (E.D. Ark. 1981); Finney v.

Mabry, 458 F.Supp. 720 (E.D. Ark. 1978); Finney v. Hutto, 410 F.Supp. 251

(E.D. Ark. 1976) aff’d 548 F.2d 740 (8th Cir. 1977); Finney v. Hutto, 505

F.2d 194 (8th Cir. 1974); Holt v. Hutto, 363 F.Supp. 194 (E.D. Ark. 1973);

Holt v. Sarver, 309 F.Supp. 362 (E.D. Ark. 1970), aff’d in part, rev’d in

part, 442 F.2d 304 (8th Cir. 1971); Holt v. Sarver, 300 F.Supp. 825 (E.D.

Ark. 1969). Those prior decisions do not appear to have formed the basis

of the district court’s decision, but they may have served as a valuable

backdrop against which the ADC’s employment policies could be viewed.

This is not impermissible.

A-7

‘pattern and practice’ cases are factually and analytically

ind istingu ishab le from adverse im pact ‘excessive

subjectivity’ cases.” Id. (footnotes omitted). As the evidence

sufficiently supported both theories of liability in this case,

liability could be premised on either theory. See generally

K irby v. Colony Furniture Co., 613 F.2d 696, 702 & 705 (8th

Cir. 1980).

As the appellants acknowledge, in addition to

examining the specific disparate treatm ent claims of the

named plaintiffs, the court received substantial testimony

from other witnesses as to the “assignment of blacks to

least desirable jobs; m istreatm ent and verbal abuse by

white supervisors; arbitrary terminations of blacks for

reasons for which whites are not terminated; submission of

only white applicants to QRC and Legislative Council;

subjective denials of promotions due to favoritism toward

white applicants; and a multitude of other intentional acts of

discrimination.” Appellant’s Brief at 10 (emphasis added).

Additionally, however, the court also relied on impact-type

evidence to support his finding that the otherwise “neutral”

subjective promotional policies of the ADC adversely

affected blacks. 4 Specifically, the court found:

Commissioner Lockhart also enumerated his

criteria in evaluating employees for promotions: a

person who is energetic, a person who can adapt to the

institutional environment, a person who will go by

policy and procedure, a person who will devote lots of

time to the job, a person who is willing to learn and

listen, a person who can be depended on in a crisis

situation, a person who shows maturity with staff and

inmates, a person you can trust in a time of trouble, a

4

“In the excessive subjectivity case, plaintiffs do not challenge a

specific employment practice but allege that the employer’s total

selection process (which is analyzed as if it were a test or objective

criterion) allows excessive subjectivity which results in an adverse

impact upon a protected group.” Schlei & Grossman Employment

Discrimination Law 1288 (2d ed. 1983) (emphasis added).

A-8

person you can depend on to aid a fellow staff person,

and a person who would perform in a professional

manner. Mr. Lockhart was not able to explain how

these personality traits could be measured objectively,

but indicated that you could observe these qualities by

working with an individual.

* * *

In summary, the administrators and Wardens who

controlled the promotion process were allowed to make

subjective judgments and to bring to their selection

their own personal philosophies concerning corrections.

This has had a disparate impact upon blacks.

* * *

During the relevant time period, the defendants

have used a variety of procedures available under state

personnel guidelines to disproportionately benefit

whites. The defendants followed the correct procedures

but this does not insulate them from liability. By use of

these procedures, opportunities were given to whites

that were not given to blacks. In addition to the use of

the substitution requests, the department brought in a

number of employees at advanced steps. These

employees were processed in accordance with state

personnel procedures. In 1979, Commissioner

Housewright made more than 25 such requests for

individuals in grades 15 and above. Not one of those

individuals was black.

* * *

The result of the defendants’ practices is that

white employees were generally hired into the

department at higher grades than black employees. The

evidence shows that for the entire period from 1973 to

1979 no black person was hired into the department

above grade level 19. Black employees comprised only

5.4% of the employees hired into grade 16 and above

and only 20.4% of those hired into grade 12 and above.

A-9

More than 23% of all white males were hired into grade

12 and above while just under 8% of black males were

hired into grade 12 and above. There can be no equal

opportunity in employment when only whites are

considered for either qualifications substitutions or

advanced step placement.

These employment practices are underscored by

the evidence that there are several positions at the

Department which have never been held by a black.

Jones v. Hutto, No. PB-74-173, Slip op. at 21-24 (E.D. Ark.

August 30, 1983). Our reading of the record is consistent

with the district court’s. The evidence in this case clearly

establishes that the subjective promotion practices had an

adverse impact upon blacks. Furtherm ore, the neutral state

personnel guidelines were employed in a manner that

produced disparate impact upon black ADC employees

Accordingly, we do not believe the court erred in its

application of the law to the evidence in this case.

A-10

CONCLUSION

We have examined the appellan ts’ rem aining

arguments in this case and find them to be without merit.

We have also carefully examined the cross-appellants’ claim

that black applicants who were not hired should have been

included in the certified class and do not find this to be an

abuse of the trial court’s discretion. Accordingly, the

judgment of the district court is affirmed.

A true copy.

Attest:

CLERK, U.S. COURT OF APPEALS, EIGHTH CIRCUIT.

B-l

APPENDIX B

In the United States District Court

Eastern District of Arkansas

Pine Bluff Division

Johnny Jones and Huey Davis, III, )

et al., )

)

Plaintiffs, )

)

v. )

) No. PB-74-C-173

Terrell Don Hutto, Individually )

and as State Corrections )

Commissioner, A. L. Lockhart, )

Individually and as )

Superintendent of the Arkansas )

Department of Corrections — )

Cummins Unit, Jerry Campbell, )

Individually and as Assistant )

Superintendent of the Depart- }

ment of Corrections — Cummins )

Unit, Marshall N. Rush, W.L. )

Curry, Lynn Wade, Thomas )

Worthen and Richard Griffin, )

Individually and as members of the )

Board of Correction of the )

Arkansas Department of )

Corrections, )

)

Defendants. )

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER

The complaint in this case was filed on May 8, 1974, by

Johnny Jones and Huey Davis, III, invoking jurisdiction

B-2

under 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq (Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964) and 42 U.S.C. §§1981 and 1983. Named as defen

dants are the Commissioner of the Arkansas Department of

Correction, a Superintendent of the Cummins Unit, an

A ssistant Superintendent, and members of the Board of

Correction of the Arkansas Department of Correction. The

case was brought as a class action and alleged a broad pat

tern of discrimination by the defendants on the basis of

race. Allegations are made that Blacks are hired in token

numbers into low paying jobs with little or no chance for ad

vancement while Whites are accorded promotional oppor

tunities in a disproportionate number. Further, Whites are

given the opportunity to receive on-the-job training while

Blacks are denied this opportunity. The alleged

discriminatory practices of the defendants were generally

outlined in paragraphs 24, 25 and 27 of the complaint.

The complaint sought a declaratory judgment and in

junctive relief from the practices and policies of the defen

dant. In addition, the plaintiffs requested appropriate

equitable relief and affirmative action, together with back

pay and attorneys’ fees consistent with the requirements of

Title VII.

The Court conditionally certified the case as a class ac

tion by Order dated September 27, 1976. By subsequent

Order dated, January 18, 1982, the Court defined the class

as follows:

All Black persons who have been employed by

the defendant Department of Correction at any time

from May 8, 1971 to the date of the commencement of

the trial, who are or have been limited, classified,

restricted, discharged or discriminated against by the

defendants with respect to promotions, assignments,

training or who have been otherwise deprived of

employment opportunities related to said factors

because of their race or color.

B-3

A fter extensive discovery and pre-trial proceedings,

the m atter was tried to the Court commencing March 29,

1982. In all, the trial lasted fifteen days with testimony con

cluding on April 28, 1982. The parties requested and the

Court granted time to prepare and submit post-trial briefs.

All proposed findings conclusions, briefs, and reply briefs

have now been submitted to the Court for determination of

the issues.

From the pleadings, the testimony and exhibits receiv

ed in evidence, and in consideration of the proposed find

ings and conclusions and briefs presented in support

thereof, the Court makes the following findings of fact and

conclusions of law. These findings of fact and conclusions of

law are incorporated herein pursuant to Rule 52 of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

The individual plaintiffs are black citizens of the

United States and were employees of the Arkansas Depart

ment of Correction at the time the lawsuit was filed. The

Departm ent of Correction is an employer within the defini

tion of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §2000e. The

Court, therefore, finds and concludes tha t it has jurisdiction

of the parties and of the cause of action herein pursuant to

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(f)(3) and 28 U.S.C. §1343 as to claims

under 42 U.S.C. §§1981 and 1983.

The Board of Correction, which is composed of five

members appointed by the Governor, is empowered to for

mulate general policies and practices with regard to

employment by the Department of Correction. The Board

must act within guidelines prescribed by the State Office of

Personnel Management of the Department of Finance and

Administration and is bound by the provisions of the

Uniform Classification and Compensation Act. Ark. Stat.

Ann. §12-3201 et seq. Directly below the Board is the posi

tion of Commissioner or Director. The Commissioner for

mulates policy for the Department, subject to the policies

and procedures prescribed by the Board of Correction.

B-4

Most of the information concerning the operation of the

departm ent is communicated to the Board through the

Commissioner. His duties include the employment of per

sonnel needed for the administration of the Department

and the promotion, discipline, suspension and discharge of

personnel in accordance with Board policy.

Below the Commissioner is the position of Assistant

Commissioner or Assistant Director. Until 1977, there was

only one such position. In 1977, the Commissioner (James

Mabry) instituted a tripartite Assistant Director system

and divided the services provided by the Department

among the three assistants. The system includes the Assis

tan t Director for Special Services with jurisdiction over

Probation and Parole. The jurisdiction of the Assistant

Director for Administrative Services includes fiscal and

personnel m atters. The Assistant Director for Institutional

Services has jurisdiction over the custodial facilities and

wardens.

Most of the testimony and evidence at trial concerned

practices within the jurisdiction of Institutional Services.

This included the correctional institutions and was the

focus of the prison conditions litigation. 1 There are eight

major facilities maintained by the Department of Correc

tion and six of these are under the jurisdiction of the Assis

tan t Director for Institutional Services:

1. The Cummins Unit is the largest unit both in terms

of personnel and inmates in the system. It houses the

most serious and older male offenders and contains the

l

Holt v. Sarver, 300 F. Supp. 825 (E.D. Ark. 1969); Holt v. Sarver, 309

F. Supp 362 (E.D. Ark. 1970), affd in part, rev’d in part, 442 F.2d 304 (8th

Cir. 1971); Holt v. Hutto, 363 F.Supp. 194 (E.D. Ark. 1973); Finney v. Hutto, 505

F.2d 194 (8th Cir. 1974); Finney v. Hutto, 410 F. Supp. 251 (E.D. Ark. 1976); affd

548 F.2d 740 (8th Cir. 1977); Finney v. Mabry, 458 F.Supp. 720 (E.D. Ark. 1978);

Finney v. Mabry, 528 F.Supp. 567 (E.D. Ark. 1981); Finney v. Mabry, 534

F.Supp. 1026 (E.D. Ark. 1982).

B-5

maximum security area. Cummins is located near

Grady, Arkansas, in Lincoln County on a 16,000 acre

farm. At the time of trial, some 16,043 inmates were

housed at Cummins. Approximately 300 employees are

authorized at Cummins.

2. The Tucker Unit is the Intermediate Reformatory

and houses the less serious and younger male offenders.

Tucker is located near Tucker, Arkansas, in Jefferson

County on a 4,500 acre farm and is authorized to have

approximately 125 employees.

3. The Women’s Unit houses female offenders. It is

located near Pine Bluff, Arkansas, in Jefferson County

and is authorized to have approximately 65 employees.

4. The Diagnostic Unit contains the hospital and

houses sick and injured inmates and some less serious

offenders and acts as the reception center for the

Department (except for females). It is located near Pine

Bluff, Arkansas, in Jefferson County and is authorized

to have approximately 65 employees.

5. The Benton Unit is a work release and pre-release

facility. It is located near Benton, Arkansas, in Saline

County and is authorized to have approximately 30

employees.

6. The Wrightsville Unit is a pre-release unit near

Wrightsville, Arkansas, in Pulaski County and is

authorized to have approximately 75 employees.

7. The Blytheville Unit is a work release facility. It is

a small unit near Blytheville, Arkansas in Mississippi

County.

8. The Booneville Unit is a farming operation and

houses no inmates. It is located in Booneville, Arkansas,

in Logan County.

The structure of each of the custodial units is essential

ly the same. Each unit is headed by a Warden who is also

B-6

referred to as a Superintendent. Wardens are somewhat

autonomous within their units and have a tremendous im

pact on the character of that unit. Below the Warden is the

A ssistant Warden position. 2 Below Assistant Warden is

the Major, 2 3 Chief of Security position. Below Major is the -

Captain or Correctional Officer IV (CO IV) position. Below

Captain is the Lieutenant or Correctional Officer III (CO

III) position. Below Lieutenant is the Sergeant or Correc

tional Officer II (CO II) position. The lowest 4 position is the

Correctional Officer I (CO I).

Each position within the Department is assigned a

numerical grade which conforms to State Personnel

guidelines. Higher grades receive higher compensation. An

employee who remains in the same position is periodically

entitled to a “step increase” even though his grade is un

changed, An increase in step means higher compensation

though not as much as an increase in grade. Grade increases

are supposed to be based on merit while step increases are

mainly a function of longevity of service.

During the course of this litigation, the grades

associated with the correctional officer positions have

changed as follows:

2

The units do not have the same number of Assistant Wardens. The

Blytheville Unit has no assistants. The Women’s Unit presently has no

assistant although there has been one in the past and the unit is authoriz

ed to have one. The Cummins Unit began with two assistants and is

presently authorized to have three.

3

In the Women’s Unit, the Chief of Security is filling a Captain’s slot.

Cummins and Tucker have two Major’s slots, one for the Building and one

for the Field. The small units do not have Majors.

4

In the field the lowest officer is a correctional Officer II (Sergeant)

although the individual has no supervisory authority over other correc

tional officers.

B-7

1972-

CO I

1974

1975-

10

1979

1980-

11

1982 13

CO II CO III

12 14

12 15

15 17

Chief of

CO IV Security

15 17

17 18

18 19

Jobs within the Department may be broadly separated

into two catgories: security positions and non-security posi

tions. Security positions are those individuals responsible

for the control and maintenance of inmates. Non-security

positions would include support services such as laundry,

mail room or kitchen. The majority of the employees in each

unit are classified as security personnel.

There are two broad divisions within the security per

sonnel classification: The Field Force and Building Securi

ty. The Field Force is responsible for inmates assigned to

outside labor such as the “hoe squad.” Officers assigned to

the Field Force do not work in the building. These officers

are armed and generally ride horses in performing their

duties. Officers assigned to Building Security perform a

variety of functions. Some of these officers work outside,

but are still considered part of Building Security because

their main function involves prisoners within the building.

Tower guards, for example, are stationed in the lookout

towers which surround the unit to guard against inmates

leaving the unit. Similarly, officers assigned to the Rover or

to one of the gates perform their duties outside the

building. The officer in the Rover vehicle patrols the

grounds surrounding the facility while the officer at a gate

is responsible for individuals entering or leaving the prison

grounds.

Within the building, there are three main types of

assignments: Barracks, PBX and Yard Desk. An officer

B-8

assigned to one of the barracks is involved in immediate

and personal contact with the inmates and is responsible for

order and discipline within the building. The PBX is the

communications center of the unit. Persons entering or

leaving the building are processed through this position and

communications between the units or within units are con

trolled from there. The Yard Desk is the operations center

of the unit. The shift supervisor is stationed there and ac

tivity of both officers and inmates is monitored from this

position.

The Department also maintains a central office which

is responsible for administrative m atters. There are ap

proximately 100 employees in this sub-division. The Parole

and Probation Division is responsible for the monitoring

and counseling of recently released prisoners or prisoners

eligible to be released and employs about 60 persons.

As previously indicated, the record in this case is quite

extensive and while the case will be decided upon this

record, the Court must note tha t this case did not arise in a

vacuum. The Arkansas Department of Correction has been

in litigation concerning prison conditions for more than a

decade. 5 From the outset of that litigation, both the

District Court and the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals con

fronted and dealt with employment at the Department. A

review of the prison conditions opinions is helpful in placing

the instant case in perspective.

In Holt v. Sarver, 309 F. Supp. 362, 373 (E.D. Ark.

1970), [referred to as Holt II], Judge Henley found that the

Arkansas prison system was controlled and operated in

large part by the inmates. At that time there were almost

1000 inmates confined at Cummins; there were only 35 “free

world” employees, eight of whom were available for guard

duty. Judge Henley stated that a sentence to the Arkansas

See footnote 1, supra.

5

B-9

Penitentiary amounted to a banishment from civilized

society to a dark and evil world completely alien to the free

world, a world administered by criminals under unwritten

rules and customs completely foreign to free world culture.

Holt v. Sarver, supra at 381. The Department was ordered to

replace those trustees serving as guards with free world

personnel. Thus, began the monitoring of employment at

the Department of Correction.

In Holt v. Hutto, 363 F. Supp 194, 205 (E.D. Ark. 1973),

(Referred to as Holt III), employment of free world person

nel was again confronted by Judge Henley. Again, this was

in the context of the constitutional requirement of a

desegregated prison.

. . . And it should be obvious that apart from any ques

tion of constitutional law black inmates will make a bet

ter adjustment to prison life and will conform better to

prison routine and requirements if they believe affir

matively that members of their race are being treated

fairly and without discrimination on account of race.

The Court’s previous decrees will be supplemented

so as to enjoin racial discrimination in any form and in

all areas of prison life.. . .

To start with, existing prison rules about employee

language should be enforced rigorously and higher

echelon personnel should set an example to their

subordinates . . . .

Third, and this is extremely important, more black

employees should be recruited, and blacks should be

assigned to meaningful positions of authority, including

assignments to Classification and Disciplinary Commit

tees . . . .

. . . The Court realizes that qualified blacks who are

willing to fill positions of responsibility and authority in

prison administration may be in short supply . . . . But,

the difficulty of hiring qualified blacks should certainly

not deter respondents from trying to do so.

B-10

Holt III was appealed to the Eighth Circuit Court of

Appeals. Finney v. Arkansas Board of Corrections, 505 F.2d

194, 210 (8th Cir. 1974). [Referred to as Finney I]. Judge Lay,

writing for the majority, noted tha t when the litigation

began in 1970 racial discrimination was a serious problem

within all the institutions operated by the Arkansas Board

of Correction. The Court found that the District Court opi

nion fell short of its intended goal.

Very little has been accomplished in the recruit

ment of black employees. Those who have been hired

assume, with slight exception, no position of control in

fluence or even persuasion. Resources, according to

Commissioner Hutto, will not permit offering salaries

sufficient to attract the qualified individuals he seeks.

We need only repeat that inadequate resources cannot

justify the imposition of constitutionally prohibited

treatment. Even assuming qualified blacks cannot be

found, we are not persuaded that an alternative such as

establishing a program in which blacks could be trained

until qualified is not viable.

On remand the district court should amend its

decree to include an affirmative program directed

toward the elimination of all forms of racial discrimina

tion. In doing so it should consider the standards now

employed in the hiring and promotion of prison person

nel. The court must assure itself that those standards

are reasonably related to proper correctional goals and

not designed to preserve institutional racial dis

crimination.

The Court of Appeals remanded the case to the District

Court for further evidentiary hearings. The Court found

the Arkansas correctional system to be unconstitutional.

On remand, the District Court, Judge Henley sitting by

designation, again considered race relations within the

prison system. Finney v. Hutto, 410 F. Supp. 251, 265-68

(E.D. Ark. 1976).

B-ll

Negroes in Arkansas are in a substantial minority

when compared with the population of the State as a

whole. In the Department of Correction, however, black

inmates make up nearly one-half of the total prison

population and have done so for as long as this court has

been familiar with the Arkansas prison system.

Administration of the Department, on the other

hand, is clearly under the control of white people.

Although in recent years the Department has employed

a substantial number of blacks and is trying to hire

more, a large majority of the employees are white, and

Negroes occupying positions of any real authority are

very few indeed.

Regardless of the fact that at Cummins, and

presumably at Tucker as well, one finds a number of

black employees bearing titles such as Captain, Lieute

nant or Sergeant, it appears to the court that the only

black person who occupies a position of any real authori

ty in the administration of the prison system is Ms.

Helen Carruthers, the Superintendent of the Women’s

Reformatory. . . .

In Holt III the court found that race relations in

the Department were bad, to say the least, and the

Court of Appeals certainly did not disagree with that

finding. [Citation omitted].

Most of what the court had to say in Holt HI by

way of criticism of the Department in the field of race

relations is still valid today, . . . While conditions in the

Department have probably improved somewhat over

the last two years and several months, the court finds

that in spite of Departmental regulations and memoran

da designed to improve race relations and to eliminate

or mitigate the effects of poor race relations, the rela

tions between whites and blacks are still bad at both

Cummins and Tucker, particularly at the former institu

tion. And the court further finds that the poor relations

are still due to the factors that the court found

causative in Holt III, namely a paucity of blacks in posi

tions of real authority that are meaningful to inmates in

B-12

their day to day prison life,. . . and the poor quality and

lack of professionalism of the lower echelons of prison

employees who are in close and abrasive contact with

inmates every day. . . .

This is not a fair employment practices case. The

question is not whether the Department is

discriminating against blacks in matters of hirings, pro

motions, or discharges, but whether the recruitment

and promotional policies of the Department are design

ed to correct or alleviate the racial imbalance of the

Department’s staff which has contributed so much to

the difficulties that the Department has had in the area

now under consideration.

What the Department needs to do is not to hire

people without regard to race but to make a conscious

effort to hire qualified blacks in additional numbers and

to place them in positions in the institutions which will

enable them to exercise some real authority and in

fluence in the aspects of prison life with which black in

mates are primarily concerned.

The Department needs more blacks who are in

positions that will entitled them to sit on classification

committees and on disciplinary panels, to counsel with

inmates about their problems, and to supervise inmates

while at work . . . .

There is no constitutional objection, of course, to

the Department’s using the ESD as a referring service,

but the exclusive use of that agency is not apt to

produce applicants the hiring of whom will meet the

Department’s need to correct the existing racial

imbalance of the staff.

The court recognizes, as it has recognized in the

past, that it is difficult to recruit blacks who are

qualified and willing to hold responsible positions in the

Department; a number of factors are involved, including

the rural location of the prisons. But the court is not

satisfied that Commissioner Hutto and others

B-13

connected with prison personnel have really exerted

themselves to the fullest extent possible or have

exhausted their resources as far as hiring responsible

blacks is concerned.

There is nothing to indicate that the Department’s

need in this connection has been made known to the

black population in Arkansas through advertising or

otherwise, or that anyone connected with the

Department has sought to enlist the good offices of the

University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, which is a

predominately black institution of higher learning and

which used to be an all black college, or that help has

been sought from such agencies or organizations as the

Urban League or the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, or from any

governmental agencies concerned with the welfare

of minorities.

In 1978, a Consent Decree was entered in Finney v.

Mabry, 458 F. Supp. 720 (E.D. Ark. 1978). This decree

contained specific agreements between the parties as to an

affirmative action program for the recruitm ent and

promotion of blacks to decision-making positions within the

Department.

. . . The following mechanism will be employed to carry

out this obligation.

(1) The immediate assessment of all Black

employees of the ADC for promotions to vacant

positions of authority.

(2) The continuation of a personnel office within

the ADC.

(3) The establishment of an employment

referral service with the Urban League of Greater

Little Rock.

(4) Listing of all job vacancies with the Placement

Office of the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff.

B-14

(5) Continuation of the ADC’s present policy of

hiring personnel, regardless of race.

Judge Eisele in Finney v. Mabry, 534 F. Supp. 1026,

1043-1045, (E.D. Ark. 1982) found the Department not to be

in compliance with previous Court Orders, the Consent

Decree and the Constitution with regards to the affirmative

action program.

The implementation of the affirmative action

program is a more complex issue with which to deal.

This is not an employment discrimination case where

the court is interested in testing, and remedying if

necessary, possible discrimination against blacks by the

respondents in their hiring practices. The reason the

affirmative action program is so important is not to

benefit potential employees of the department,

although they are directly benefited. Rather, the

importance is in obtaining a racial mix of the security

personnel in order to alleviate feelings by black

inmates, which are approximately half of the inmate

population, that they are being discriminated against.

The primary effort must be to hire qualified blacks and

place them in positions of authority in all aspects of

prison life.

The evidence demonstrated that the respondents

have increased their efforts to recruit qualified black

persons to work within the department. Those efforts

have been successful to the extent that blacks are well

represented among the highest and the lowest ranking

officers. In fact, it was shown that at the time of the

hearing 53 percent of the correctional officers, the

lowest level officers, were black. However, there have

not been, and still are not, blacks in the middle

management positions in significant numbers . . .

. . . However, the Court finds it difficult to

understand, with a pool of black persons for potential

advancement as high as 50 percent of the relevant work

force, why greater efforts at selection and training

B-15

would not result in promotion and retention of a greater

number of blacks.

. . . However, the respondents must know that

blacks, as previously ordered, must be employed in

reasonable numbers at all levels of free-world

personnel.

The District Court found the Department of Correction

to be in full compliance with the Constitution and previous

Court Orders in August, 1982 and dismissed the litigation.

It marked the end of more than a decade of litigation

involving prison conditions. In its final opinion, the District

Court stated, “The affirmative action program for hiring

and promoting women and minorities as free-world

personnel, especially into mid-level management positions,

is another area where the results accomplished have fallen

somewhat short of expectations.” Finney v. Mabry, 546 F.

Supp. 628 (E.D. Ark. 1982). The Court further noted that the

concern in the case was not with the rights of minority and

female employees, but rather with the rights of the inmate

class to have an appropriate racial and sexual mix in the

administrators of the system. This difference in focus

greatly affected the standard for evaluating the affirmative

action program of the Department.

This Court, however, is directly concerned with the

rights of minority employees and its focus is on whether

their constitutional right to equal opportunities in

employment have been violated. After careful review of the

record in this case, the Court must conclude that there has

been discrimination in employment at the Arkansas

Department of Correction.

As indicated by Judge Eisele in his dismissal of the

prison conditions litigation, the Department of Correction

has come a long way since Judge Henley first described it as

a dark and evil world. The various prison institutions are

B-16

being run by free world personnel. Blacks have been hired

and in 1980 comprised 31.2% of this free world workforce;

at the time of trial, blacks comprised 34% of the workforce

at the department. The Court has concluded there is no

discrimination in initial hiring; blacks are hired at the

Department of Correction in proportion to their number in

the Pine Bluff Area. It is a different story, however, with

initial placement and promotions.

Blacks are invariably hired as CO I’s and most remain

in that position. They are not promoted in proportion to

their numbers within the workforce. Further, they are

assigned to the least desirable shifts and jobs at the

Department, tha t being the evening and night shifts and

Tower duty. Blacks are especially overrepresented on the

night shift. Testimony at trial indicated that not only are

these shifts the least desirable, but also do not allow an

employee to gain experience deemed valuable when being

considered for promotions. Commissioner Lockhart

testified tha t when evaluating employees for promotion he

looked to their experience within the Department. He

stated that someone who had only worked at night and in

the Tower would not be rated as highly as someone who had

had direct contact with inmates during the day.

With promotions, it is abundantly clear from the

testimony and the evidence introduced at trial, tha t blacks

must be overqualified through either experience and/or

education to receive a promotion. Whites are routinely

promoted without the stated qualifications and are allowed

extensive periods of on-the-job training. Jerry Campbell,

Warden at the Tucker Unit, came to the Department of

Correction in 1972 as a Personnel and Training Officer. He

had a Bachelor’s Degree in Physical Education and had

worked as a junior high and high school football coach, an

insurance salesman and a management trainee. When hired

as the Personnel and Training Officer, Campbell admitted

that he did not meet the stated requirem ents for the

position. He did not have the appropriate degree nor did he

B-17

have any correctional experience. He readily admitted that

he received on-the-job training. After less than a year with

the Department, Campbell became the Assistant Warden at

the Tucker Unit. Again, Campbell admitted that he did not

have the educational or experience requirement for the

position and had to be trained on-the-job. Campbell has

advanced within the departm ent and has served as both a

Warden at Cummins and Tucker. The Court does not mean

to imply that Campbell has not been an excellent and hard

working employee. However, there is no evidence that any

black has ever been given the same kind of opportunity to

receive on-the-job training and be advanced to this degree.

Warden Campbell is not the only example of a white

who has been placed and promoted to positions for which

they were not initially qualified. Charles E. “Lefty” Thomas