Camer v. Seattle School District No. 1 Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Washington State Court of Appeals, Division I

Public Court Documents

May 25, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Camer v. Seattle School District No. 1 Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Washington State Court of Appeals, Division I, 1989. 80a639a6-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a355c785-cb3c-4c89-9610-58427b0e4803/camer-v-seattle-school-district-no-1-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-washington-state-court-of-appeals-division-i. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

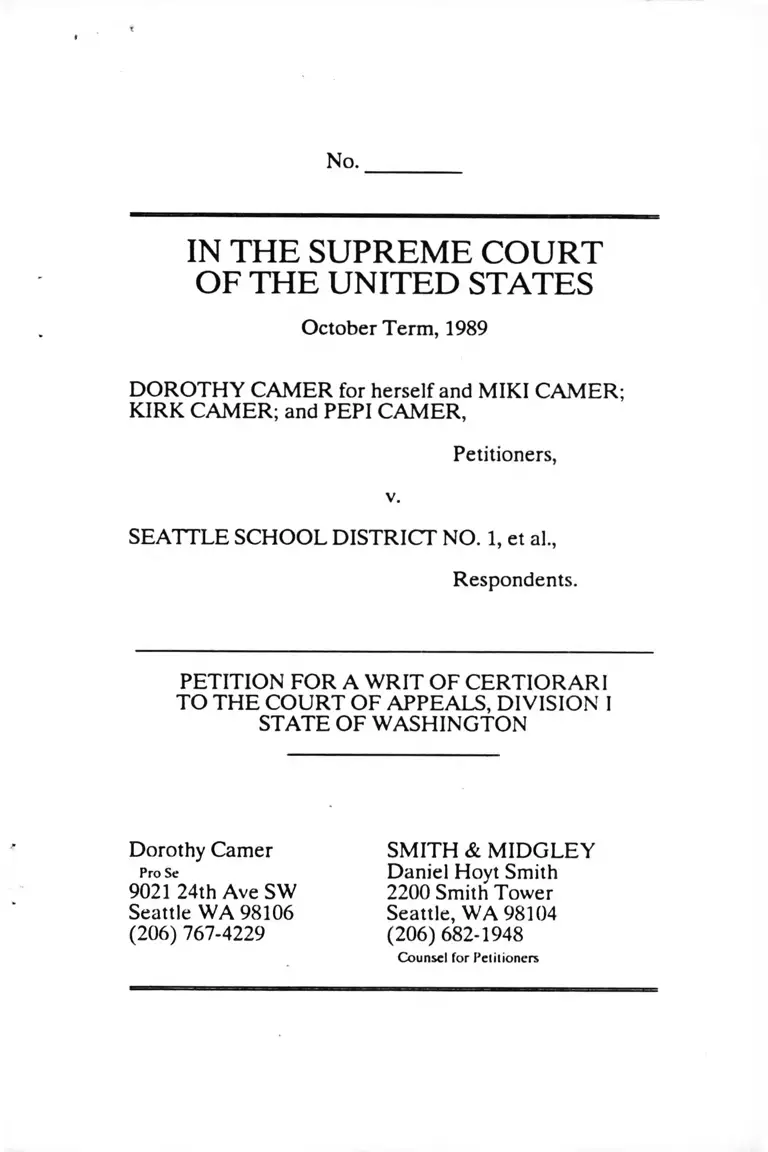

No.

IN THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1989

DOROTHY CAMER for herself and MIKI CAMER;

KIRK CAMER; and PEPI CAMER,

Petitioners,

SEATTLE SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE COURT OF APPEALS, DIVISION I

STATE OF WASHINGTON

Dorothy Camer

Pro Se

9021 24th Ave SW

Seattle WA 98106

(206) 767-4229

SMITH & MIDGLEY

Daniel Hoyt Smith

2200 Smith Tower

Seattle, WA 98104

(206) 682-1948

Counsel for Pclitioners

i

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Are students in compulsory attendance at public

schools, and their parents, entitled to Fourteenth

Amendment Due Process protection against arbitrary

denial of the minimum elements of a basic education

mandated by state law, regulation, and contract

principles?

2. May the state courts refuse to protect students’

and parents’ federally protected due process liberty and

property interests against arbitrary deprivation of a

minimum education, on the basis of restrictive state law

interpretations of "standing," "res judicata," and the state

legislature’s failure to create a "private cause of action"

for violation of the basic education laws?

11

The parties are the Petitioners: Dorothy Camer,

parent; and Kirk Camer, Pepi Camer, and Miki Camer,

students; and Respondents: Seattle School District No. 1;

William M. Kendrick, Donald J. Steele, Robert L. Nelson,

and David L. Moberly, past and current school

superintendents; Patt Sutton, John Rasmussen, Richard J.

Alexander, Barbara Beuschlein, Michael Preston, T. J.

Vassar, Cheryl Bleakness, Suzanne Hittman, Dorothy

Hollingsworth, Ellen Roe, Susan Harris, Elizabeth Wales,

and Jerry Saulter, past and current school board directors;

David Stevens, Charles Trujillo, Ellen Lew, Robert

Andrew, Cheryl Chow, Albert Jones, Rachel Gray, Chris

Kato, Barbara Herring, Alan Neman, Sonya Watson,

Robert Gary, Kenneth Dorsett, Gertrude A. Beamon,

Susan Hanson, Jewell Woods, and Shirley Hodgeson, past

and current administrative and teaching personnel; and

Michael Hoge and Phillip Thompson, school district legal

counsel.

LIST OF PARTIES

Ill

Questions Presented............................................................. i

List of Parties........................................................................ii

Table of Authorities.............................................................v

PETITION FOR WRIT OF

CERTIORARI........................................................... 1

OPINION BELOW .............................................................2

JURISDICTION..................................................................2

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS,

STATUTES, RULES AND

REGULATIONS INVOLVED............................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE......................................... 2

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE

W RIT...........................................................................7

1. The Fourteenth Amendment Protects

Against Arbitrary Denial of the

Legitimate Entitlement to Basic

Education Which is Explicitly

Guaranteed and Defined by State Law ..................... 7

2. The Washington State Courts Have Failed

to Recognize the Plaintiff School

Children’s Federally Protected Rights...................... 13

CONCLUSION..................................................................18

APPENDICES

Decision of State Court of Appeals...............................A -1

Order of State Supreme Court...................................A -10

TABLE OF CONTENTS

IV

Mandate of State Court of Appeals........................... A-10

Order of King Co. Superior Court.................................B-l

Final Order of King Co. Superior Court.......................B-6

Camer v. Brouillet, State Court of Appeals

Decision................................................................. C-l

Camer v. Eikenberry Ninth Circuit

Court of Appeals................................................... C-6

Washington Constitution and Laws.............................. D-l

V

Cases

Adickes v. Kress, 398 U.S. 144 (1970)........................... 17

Allen v. McCrary, 449 U.S. 90(1980)............................ 15

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby,

477 U.S. 242 (1986)............................................... 17

Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954).............................................. 7,9

Camer v. Seattle School District,

52 Wn. App. 531, 762 P.2d 356

(1988)........................................................................ 2

Camer v. Stevens, 50 Wn. App. 1018

(1987)........................................................................ 4

Carey v. Piphus, 435 U.S. 247

(1978)................................................................ 16, 17

City of Revere v. Massachusetts Gen.

Hosp., 463 U.S. 239(1983)..................................... 8

Daniels v. Williams, 106 S.Ct. 662 (1986)..................... 13

Davidson v. Cannon, 106 S.Ct. 668 (1986).........................

13

De Shaney v. Winnebago County,

No. 87-54, 57 L.W. 4218

(Feb. 22, 1989)........................................................ 9

Edwards v. California, 314 U.S. 160

(1941)...................................................................... 18

Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97 (1976)............................. 8

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

VI

Felder v. Casey, 101 L.Ed.2d 123 (1988)...................... 15

Gjellum v. City of Birmingham, Ala.,

829 F.2d 1056 (11th Cir. 1987)............................. 15

Goss v. Lopez, 419 U.S. 565 (1975)......................... 11, 15

Hampton v. City of Chicago,

484 F.2d 602 (7th Cir. 1973)................................. 14

Haring v. Prosise, 462 U.S. 306 (1983).......................... 16

Kentucky Department of Corrections v.

Thompson, 57 L.W. 4531,

(May 15, 1989)....................................................... 12

Kremer v. Chem. Constr. Corp.,

456 U.S. 461 (1982)....................'........................... 15

Maine v. Thibotout, 448 U.S. 1

(1980).......................................................... 13

Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S.

(1 Cranch) 137 (1803)........................................... 14

Martinez v. California,

444 U.S. 277(1980)............................................... 13

Matzker v. Herr, 745 F.2d 1142

(7th Cir. 1984).................................................... 8, 13

Migra v. Warren City School Dist.

Bd. of Educ., 465 U.S. 75 (1984).......................... 15

Millikan v. Board of Directors of Everett

School District, 93 Wn.2d 522,

611 P.2d 414 (1980)............................................... 12

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961)............................ 14

O’Connor v. Donaldson, 422 U.S. 563

(1975)........................................................................ 9

V l l

Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202 (1982)................................... 9

San Antonio Independent School Dist. v.

Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973)........................... 10, 11

Seattle School District v. State,

90 Wn.2d 476, 585 P.2d 71

(1978).................................................................. 3, 14

Stoneking v. Bradford Area School District,

856 F.2d 594 (3rd Cir. 1988)................................... 9

Taylor v. Ledbetter, 818 F.2d 881

(11th Cir. 1987)......................................................... 8

Testa v. Katt, 330 U.S. 386 (1947)................................. 13

University of Tennessee v. Elliot,

106 S.Ct. 3220 (1986)............................................. 15

Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972)...................... 10

Wyatt v. Aderholt, 503 F.2d 1305

(5th Cir. 1974)........................................................... 9

Youngberg v. Romeo, 457 U.S. 307

(1982).................................................................... 8 ,9

Constitution

U.S. Constitution, Amendment XIV............................... 2

Statutes

28U.S.C. 1257(a)............................................................ 2

42U.S.C. 1983..................................................... 2, 4, 5, 6

RCW 28A.02.080........................................................... 5, 7

RCW 28A.05.010............................................................... 5

V l l l

RCW 28A.05.050............................................................... 5

RCW 28A.27.020............................................................. 12

RCW 28A.58.090......................................................... 5,12

RCW 28A.58.750............................................................... 5

RCW 28A.58.754......................................................... 5, 12

RCW 28A.58.758............................................................... 5

RCW 58A.58.090............................................................. 11

WAC 180-16....................................................................... 5

WAC 180-50....................................................................... 5

Other Authority

National Commission on Excellence in

Education, A Nation at Risk: The

Imperative for Educational Reform

(1983)........................................................................ 7

C. Wright, Law of Federal Courts 271-73

(4th Ed. 1983).......................................................... 13

Chambers, Adequate Education for All: A

Right, An Achievable Goal, 22

Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties

Law Rev. 55 (1987)................................................. 10

Changing Course-A 50-State Survey of

Reform Measures," Educ. Week 11

(Feb. 6, 1985)........................................................... 10

Kirp & Yudof, Educational Policy and

the Law (2d Ed. 1982)............................................ 10

Moore’s Federal Practice 0.411...................................... 16

IX

Nahmod, Civil Rights And Civil Liberties

Litigation, The Law Of 1983 (2nd

Edition)................................................................... 14

Neuborne, "The Myth of Parity," 90 Harv.

L. Rev. 1105 (1977)................................................ 14

Ratner, "A New Legal Duty for Urban

Public Schools: Effective Education

and Basic Skills,"

63 Tex. L. Rev. 787 (1985).................................... 10

U.S. Department of Education, "The

Nation Responds" (May 1984)............................. 10

N o._________

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED

STATES

October Term, 1989

DOROTHY CAMER for herself and MIKI Camer;

KIRK CAMER; and PEPI CAMER,

Petitioners,

SEATTLE SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

WASHINGTON STATE COURT OF APPEALS,

DIVISION I

The petitioners, Dorothy Camer, parent, and Kirk,

Pepi, and Miki Camer, students, respectfully pray that a

Writ of Certiorari issue to review the judgment and

opinion of the Washington State Court of Appeals,

Division I, entered in this proceeding on October 10,

1988.

2

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Washington State Court of

Appeals, dated October 10, 1988, is reported at 762 P.2d

356, 52 Wn. App. 531 (1988) and is reproduced in

Appendix A. The order denying reconsideration was filed

December 7,1988. The Petition for Discretionary Review

by the Washington State Supreme Court was denied on

February 28, 1989. The Order and Mandate are

reproduced in Appendix B. The Findings and

Conclusions and Order of Dismissal by the trial court are

also at Appendix B. The decisions in the two prior related

cases are at Appendix C.

JURISDICTION

This Court’s jurisdiction is invoked under the U.S.

Constitution, Amendment XIV, 42 U.S.C. 1983; and 28

U.S.C. 1257(a), to review a final judgment of the highest

court of a state which conflicts with the decisions of this

court on important federal constitutional issues.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS, STATUTES,

RULES AND REGULATIONS INVOLVED

The United States Constitution, Fourteenth

Amendment; Washington Constitution, Article 9, Section

1. Title 42, United States Code, 1983. Revised Code of

Washington, Chapter 28A. Washington Administrative

Code, Chapter 180.

Excerpts of State Constitution and Laws are set forth

in Appendix D.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioners Kirk, Pepi, and Miki Camer were school

children, required by law to attend the Seattle,

3

Washington, Public Schools. They entered the sixth, fifth,

and kindergarten grades, respectively, in the Fall of 1978.

Kirk and Pepi have now graduated from high school, and

Miki has completed 9th grade. Parent Dorothy Camer

became aware that the instruction provided in the schools

which the children attended did not adhere to the

advertised curriculum of the Seattle School District. After

examining the Seattle School District’s published

curriculum, she discovered that essential elements of the

curriculum were not taught. She raised her concern with

the teaching personnel and administrative staff but

received no substantive explanation. While not denying

the lack of instruction, they provided no rationale, nor

cited any standards which were followed.

She continued to raise her concerns to state officials,

e.g. the Superintendent of Public Instruction (SPI), state

legislators, senators and representatives, the local mayor

and prosecutors. For the most' part she received little

help except for one state senator who referred her to the

state education laws. After studying the law and the

record in Seattle School District v. State. 90 Wn.2d 476,

585 P.2d 71 (1978), she brought suit in state court against

the State Superintendent of Public Instruction and others,

alleging that Kirk and Pepi had failed to achieve certain

benchmarks and that they had been denied access to

certain courses, in violation of state law and tort

principles. She filed the action pro se in 1979 since she

lacked the funds for legal counsel, on behalf of herself and

the two older children.

The state court case was dismissed and, by an

unpublished opinion, subsequently affirmed, on the

grounds that (a) no damage action is created by the state

Basic Education Act, (b) no common-law tort claim was

stated because schools do not have a duty to "insure that

every student"..."will be able to achieve every benchmark,"

and (c) that since Plaintiffs’ rights to a basic education

under state law "are not disputed by the Defendants"

4

(App. C-2), that no justiciable controversy would justify a

declaratory judgment.

While the appeal was pending in state court, Kirk

Camer and Dorothy Camer alone brought a separate suit

in federal court under 42 U.S.C. 1983. This suit was also

dismissed, and the Ninth Circuit affirmed, holding that no

disparate treatment on the basis of a suspect classification

had been alleged to support an equal protection claim,

that due process does not require notice to Kirk of

optional honors classes, and that state law claims should

be litigated in state court where they were pending, rather

than federal court.

Pepi Camer completed the state history course the

following year, without the instruction in the state

constitution which is required by state statute as a

prerequisite to graduation. When Ms. Camer was

dismissed without a hearing both in the state and federal

courts, she decided that she needed more evidence of the

denial of instruction. She requested documents from the

School District to support her complaints. When the

school district denied her requests for access to

documents, Ms. Camer filed suit under the State public

disclosure act, and finally won in 1985. (Affd, Camer v,

Stevens. 50 Wn.App. 1018 (1987)). She discovered

numerous failures by defendants to meet the minimum

requirements for a basic education, in violation of state

law, regulations, and advertised promises.

In 1986, just before this action commenced, Miki

Camer was scheduled to take the state history course.

Ms. Camer hoped to ensure that Miki would receive the

legally mandated instruction in the state constitution

which had been arbitrarily denied her brother and sister.

Ms. Camer again raised the issue to school administrators,

the school board, Superintendent of Public Instruction,

and Attorney General, with no success. A letter from the

school superintendent acknowledged that the state

constitution should be covered in the 8th grade state

5

history course but declined to provide any assurance that

it would be. Letters from both the school district legal

counsel and the president of the school board admitted

that due process hearings are limited to disciplinary and

special education issues, and that no administrative

procedure is provided by defendants for handling

instructional grievances. Miki has since completed the

course under Defendant Jewell Woods without receiving

the instruction in the state constitution. She was also

denied the full hours of instruction required by state law

(RCW 28A.58.754). Miki has not been a party to, or

subject of, any prior lawsuit.

Invoking 42 U.S.C. 1983, Petitioners brought action

in King County Superior Court for injunctive and

declaratory relief and damages under the state basic

education laws, and the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. The Complaint alleged denial

by the Respondents of the minimum basic education

mandated by state laws and regulations, including, for

example, the requirements for a minimum of six hours of

instruction 180 days per year (required by RCW

28A.58.754(2 and 5) and 28A.58.758(2)(c)); elements of

the math and language arts curricula (promulgated under

RCW 28A.58.090 and 28A.05.010); and instruction in the

state constitution (required by RCW 28A.02.080;

28A.05.050).

Kirk and Pepi Camer were permitted to graduate

from the Seattle Schools with above average grades

without the minimum basic education defined by the state

laws (RCW 28A.58.750 through .754) and regulations

(WAC 180-16 and -50) and in particular without the

minimum requirements for graduation, such as the state

constitution and elements of the language arts curriculum,

and without the annual evaluation required by RCW

28A.58.090. The Complaint further stated that these

arbitrary denials of education deprived Plaintiffs of liberty

and property without due process of law, and were in

6

violation of the civil rights of the students under 42 U.S.C.

1983.

Respondents/Defendants neither denied the

deprivation of instruction nor provided any explanation as

to why it was lacking. Instead their defense was that even

if the basic education had been denied, state law did not

provide a private cause of action to students thus injured,

that loss of education was not an injury, that defendants

were immune under state law, and numerous technical

defenses. The Superior Court dismissed the action on

March 18, 1987. An appeal was filed with the state

Supreme Court which remanded it to the state Court of

Appeals, which affirmed the Superior Court decision.

The federal questions were timely and properly raised

in the complaint, at 5-6; the Amended Complaint, 2-3, the

Brief of Appellant at 27-29, the Reply Brief of Appellant,

at 19, 22, the Petition for Review, at 8-9; the Reply of

Petitioner, at 10. The trial court rejected the federal

claims at App. B-3, and the Court of Appeals affirmed at

A-7: 'The Camers do not state a claim under...the United

States Constitution...Nor do the Camers...have...standing

to bring an action for violation of constitutional

provisions."

The Court of Appeals held that the legislature did not

intend to create a judicial remedy under state law for

denials of the specified basic education required to be

provided to all students. It was held that this action was

similar to those previously brought by Mrs. Camer for her

older children against different parties based on different

facts, so that "res judicata" should bar even the claim of

Miki Camer, who had been involved in no prior action.

Finally, and without explanation, the court found plaintiffs

to have claimed insufficient injury to have "standing" to

complain of violation of their constitutional rights.

A petition for discretionary review of the appellate

court decision was filed and was denied by the

Washington Supreme Court on February 28, 1989. We

7

now seek certiorari to review the decision of the Court of

Appeals.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

1. The Fourteenth Amendment Protects Against Arbitrary

Denial of the Legitimate Entitlement to Basic Education

Which is Explicitly Guaranteed and Defined by State Law.

Our public schools have failed to adequately educate

millions of students in the minimal skills needed to

function in the social, economic, and political systems. As

a result, "our nation is at risk." National Commission on

Excellence in Education, A Nation at Risk: The

Imperative for Educational Reform (1983).

Today, education is perhaps the most important

function of state and local governments. Compul

sory school attendance laws and the great expendi

ture for education both demonstrate our recogni

tion of the importance of an education to our

democratic society. It is required in the perfor

mance of our most basic public responsibilities....it

is the very foundation of good citizenship. In these

days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably

be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the

opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity

where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a

right which must be made available to all....

Brown v. Board of Education. 347 U.S. 483, 493 (1954).

Plaintiff Dorothy Camer has, like many other parents,

been deeply concerned about the quality of education in

our public schools. Many proposals have been made for

changing our schools-defining new goals or methods to

achieve them. But before such changes are prescribed, a

more fundamental question is whether the schools are

performing their existing specific legal duties. If they are

8

out of control, and administrators are not held responsible

for following their specific existing legal obligations, what

good will it do to give them new ones?

When in a person is in custody of the state, she is

entitled to attention to her medical needs. Estelle v.

Gamble. 429 U.S. 97 (1976) ("deliberate indifference" to

medical needs of convicted prisoners a violation of

1983"). In Matzker v. Herr. 745 F.2d 1142 (7th Cir.

1984), the court held that a pre-trial detainee’s due

process right to be free from punishment is violated when

a jailor fails "properly and reasonably to procure

competent medical aid" for illness or injury. Thus, while

the Eighth Amendment does not protect pre-trial

detainees, or school children, the Due Process rights of an

arrestee "are at least as great as the Eighth Amendment

protections available to a convicted prisoner." City of

Revere v. Massachusetts Gen. Hosp.. 463 U.S. 239, 244

(1983). And "persons who have been involuntarily

committed are entitled to more considerate

treatment...than criminals...Cf. Estelle." Youngberg. 457

U.S. 310, 322-323 (1982).

It has been held that a child in custody of the state,

states a cause of action under 1983 when state officials

are deliberately indifferent to or act in reckless disregard

of her welfare. Taylor v. Ledbetter. 818 F.2d 881 (11th

Cir. 1987) (en banc). It was held there that the Georgia

statutory scheme creates a legitimate entitlement to

certain care, enforceable in federal court. The special

relationship between plaintiff children and the agency

employees and officials required by law to provide them

with certain services "is an important one involving

substantial duties and, therefore, substantial rights." Id.,

at 798. Under Washington law, the Camer children were

required to attend school. RCW 28A. App. D-(fine

and/or jail for violation of compulsory.education statute).

"Because students are placed in school at the command of

the state and are not free to decline to atttend, students

9

are in what may be viewed as functional! custody of the

school authorities...." Stoneking v. bradford Area School

District. 8 5 6 F . 2 d 5 9 4 ( 3 r d C i r . 1988).

Compare De Shanev v. Winnebago County. No. 87-54, 57

L.W. 4218 (Feb. 22, 1989) at 4219, n.2 (No claim of

entitlement made below, no state custody, harm caused by

third part).

This Court has held, in the context of mental

institutions, that when the state exercises its power to

deprive persons of liberty, a reciprocal right is created to

the provision of the services for which the restraint on

liberty is justified. See O’Connor v. Donaldson. 422 U.S.

563 (1975) (no confinement without treatment);

Youngberg v. Romeo. 457 U.S. 307 (1982) (constitutional

right to adequate care); cf. (right to treatment); Wyatt v.

Aderholt. 503 F.2d 1305 (5th Cir. 1974) (minimum

standards of treatment). In Youngberg. supra, the Court

found one committed to the custody of the state for care

and treatment has a constitutional right to "such

conditions of confinement [as] would comport fully with

the purpose of respondent’s commitment." 457 U.S. at

324. The plaintiff in Youngberg was found entitled to put

on expert testimony as to whether the hospital officials’

decisions "were a substantial departure from the requisite

professional judgment." Id., at n.31.

Minimum standards of education for those in

compulsory custody of educational institutions are at least

as important. In Brown v. Board of Education. 347 U.S.

483 (1954), this Court expressed the doubt "that any child

may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is

denied the opportunity of an education." ]d. at 493.

"Education provides the basic tools by which individuals

might lead economically productive lives to the benefit of

us all." Plvler v. Doe. 457 U.S. 202, 221 (1982). Some

minimum "degree of education is necessary to prepare

citizens to participate effectively and intelligently in our

open political system if we are to preserve freedom and

10

independence." Wisconsin v. Yoder. 406 U.S. 205, 221

(1972). This Court also acknowledged the fundamental

rights of parents that are impacted by compulsory

schooling, and thus the gravity of the state’s

responsibilities. Id. at 232.

Yet thousands of students attend schools that fail to

enable students to master even basic skills. National

Commission, supra. See also U.S. Department of

Education, 'The Nation Responds" (May 1984); Ratner,

"A New Legal Duty for Urban Public Schools: Effective

Education and Basic Skills," 63 Tex. L. Rev. 787 (1985).

The recognition of this crisis has led to a nationwide

educational reform movement, as state commissions and

legislatures have proposed and enacted numerous reform

initiatives. A principal product of this movement has

been the enunciation of minimum legal standards for

basic education, creating substantive rights as defined

under state law. See Chambers, Adequate Education for

All: A Right, An Achievable Goal, 22 Harvard Civil

Rights-Civil Liberties Law Rev. 55, 61 (1987)('These

standards present us with an opportunity to define a right

to a minimally adequate education.") Standards are

essential to monitor performance of school teachers and

administrators, as well as that of students. A majority of

states have now enacted minimum criteria for evaluating

and judging the education actually provided to students.

See "Changing Course-A 50-State Survey of Reform

Measures," Educ. Week 11 (Feb. 6, 1985); Kirp & Yudof,

Educational Policy and the Law (2d Ed. 1982).

The definition of the precise content of a basic

minimum education is an ongoing process. It has been

pointed out that the right to an adequate education is

rooted in the meaningful exercise of the freedom of

expression and the right to participate in state elections

on an equal basis with other voters, and basic minimal

skills are necessary for the enjoyment of these rights. San

11

Antonio Independent School Dist. v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S.

1, 37(1973).

In San Antonio v. Rodriquez. 411 U.S. 1 (1973), "only

relative differences..." in education were challenged.

There was "no charge...that the system fails to provide

each child with an opportunity to acquire the basic

minimum skills..." Id- at 36. The issue here is precisely

the denial of the absolute minimum of education which

the Seattle School District has defined (in compliance

with the requirement of state law, RCW 58A.58.090) to

be mandated to be provided to all students. This is the

"identifiable quantum of education (which) is a

constitutionally protected prerequisite to the meaningful

exercise of either (the right to speak or the right to vote)"

that this Court indicated in San Antonio v. Rodriquez

would merit the court’s protection.

Then, in Goss v. Lopez. 419 U.S. 565 (1975) the

Court found the Fourteenth Amendment to be violated

by arbitrary deprivation of education to which a student is

entitled under state law. It rejected the contention "that

because there is no constitutional right to an education at

public expense, the Due Process Clause does not protect"

students. Id. at 572. The Court found rather that "on the

basis of state law, appellees plainly had legitimate claims

of entitlement to a public education. [State statutes]

direct local authorities to provide a free education to all

residents between five and twenty-one years of age, and a

compulsory attendance law requires attendance for a

school year of not less than 32 weeks." Id. at 573.

Although Ohio may not be constitutionally

obligated to establish and maintain a public school

system, it has nevertheless done so and it has

required its children to attend. Those young

people do not ‘shed their constitutional rights’ at

the schoolhouse door. Tinker v. Des Moines

School District. 393 U.S. 503, 506 (1969). ‘The*

Fourteenth Amendment as now applied to the

12

states, protects the citizen against the state itself

and all of its creatures-boards of education not

excepted.’ West Virginia Board of Education v.

Barnette. 319 U.S. 624, 637 (1943). The authority

possessed by the state...though concededly very

broad, must be exercised consistently with

constitutional safeguards. Among other things, the

state is constrained to recognize a student’s

legitimate interest to a public education as a

property interest which is protected by the Due

Process Clause...The Due Process Clause also

forbids arbitrary deprivations of liberty.

Id. at 574. The Court therefore held that loss of even

a few days of education triggered the protections of the

Due Process Clause against arbitrary deprivations of

liberty and property. Implicit in the recognition of such

entitlements is the requirement that they may not be

infringed except for "cause." Id., at 587, n.4 (Powell,

dissenting).

And under Washington law, the legally required

curriculum is not discretionary with the school districts or

teachers, who have no authority to "ignore or omit

essential course material or disregard the course

calendar." Millikan v. Board of Directors of Everett

School District. 93 Wn.2d 522, 611 P.2d 414 (1980).

Compare Kentucky Department of Corrections v.

Thompson. 57 L.W. 4531, 4534 (May 15, 1989) ("explicitly

mandatory language...forces a conclusion that the state

has created a liberty interest....The regulations here,

however, lack the requisite relevant mandatory

language.") The violation of legitimate expectations and

entitlements in this case all arise from unequivocally

mandatory language. See Statement, supra, at 4-5.

(RCW 28A.05: "compulsory courses"; RCW 28.02.080:

"study of constitutions compulsory"; RCW 28A.58.754:

"program requirements"; RCW 28A.58.090: "study

learning objectives...shall be locally assessed annually."

13

RCW 28A.27.020: "compulsory school attendance-

school’s duties upon juvenile’s failure to attend.")

Here, the intentional actions of defendants deprived

plaintiffs of essential elements of a basic minimum

education, over a number of years, without any cause or

justification. What is alleged is the arbitrary exercise of

governmental power, not mere negligence. Cf. Daniels v.

Williams. 106 S.Ct. 662 (1986); Davidson v. Cannon, 106

S.Ct. 668 (1986).

Certiorari should be granted to clarify and establish

the important federal Due Process right to receive at least

the minimum prescribed educational program for which

school children are taken from their parents and put in

the custody of the schools.

2. The Washington State Courts Have Failed to

Recognize the Plaintiff School Childrens’ Federally

Protected Rights.

The Supremacy Clause of the United States

Constitution compels state courts to hear and decide

1983 cases submitted to them. Cf. Testa v. Katt, 330

U.S. 386 (1947). State courts determining 1983 claims

submitted to them must apply the relevant substantive

federal rules, not state law. C. Wright, Law of Federal

Courts 271-73 (4th Ed. 1983). See Maine v. Thibotout,

448 U.S. 1, 10 n .ll (1980). As a corollary, in Martinez v.

California. 444 U.S. 277 ( 1 9 8 0 ) ; , t h e Court clearly

stated that:

Conduct by persons acting under color of state law

which is wrongful under 42 U.S.C. 1983...cannot

be immunized by state law. The construction of

the federal statute which permitted a state

immunity defense to have controlling effect would

transmute a basic guarantee into an illusory

promise; and the Supremacy Clause of the

Constitution insures that the proper construction

14

may be enforced....The immunity claim raises a

question of federal law.

Id. at 284 n.8 ('quoting Hampton v. City of Chicago, 484

F.2d 602, 607 (7th Cir. 1973) (refusing to apply Illinois

immunity law in a 1983 action), cert, denied, 415 U.S.

917 (1974)).

Unfortunately, many civil rights plaintiffs are

handicapped in state court by antipathy towards, and lack

of competence in connection with, such claims on the part

of state courts. See Neuborne, "The Myth of Parity," 90

Harv. L. Rev. 1105 (1977). This may be particularly true

when a case is brought by a so-called unpopular plaintiff

or raises controversial and politically sensitive matters, or

both. Nahmod, Civil Rights And Civil Liberties

Litigation, The Law Of 1983 (2nd Edition), at 1.13.

In Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961), this Court

recognized that one of the reasons 1983 was enacted,

was the lack of enforcement in the states of Fourteenth

Amendment rights "by reason of prejudice, passion,

neglect, intolerance, or otherwise." ]d., at 180.

In this case, plaintiffs received short shrift from the

state courts, which barely mentioned their federal claims.

Neither of the two primary grounds for dismissal under

state law justified disregard of the federal wrongs

complained of.

First, the determination that the state legislature did

not intend to create a "private cause of action" for

violations of the State’s Basic Education Act cannot

immunize the responsible state employees. Martinez,

supra. Just as the legislature cannot abridge

constitutional rights by its enactments, it cannot curtail

mandatory provisions by its silence. See Seattle School

District v. State. 90 Wn.2d 476, at 503 n. 7, 585 P.2d 71

(1978), citing Marburv v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137,

163 (1803). The explicit purpose of 1983 is to create a

"private cause of action," and "the Supremacy Clause

imposes on state courts a constitutional duty to proceed in

15

such a manner that all the substantial rights of the parties

under controlling federal law are protected." Felder v.

Casev. 487 U.S. 101 L.Ed.2d 123, 146 (1988). In Goss

v. Lopez. 419 U.S. 565 (1964), this Court rejected the

argument that state law discretion granted to school

principals limited the due process rights of school

students. Once the entitlement is created by state law, the

federal constitution limits the circumstances under which

it can be taken away. This principle was disregarded by

the state court in limiting 1983 causes of action to those

in which the state legislature has created a "private right

of action."

Likewise, the second principal holding, that these

claims are barred by res judicata under state law, conflicts

with federal principles of res judicata. In Allen v.

McCrary. 449 U.S. 90, 95 n.7 (1980), this Court held that

the Full Faith and Credit Statute requires federal courts

to apply state issue preclusion rules in 1983 actions only

when the party against whom issue preclusion is sought

had a full and fair opportunity to litigate the issues

actually decided in a prior state court proceeding. In

Migra v. Warren City School Dist. Bd. of Educ., 465 U.S.

75 (1984), it was held that the same principles apply to

claim preclusion. Id. at 84. Cf. University of Tennessee v.

Elliot. _ U.S. _ , 106 S.Ct. 3220, 3227 (1986); Giellum v.

City of Birmingham. Ala.. 829 F.2d 1056, 1063 (11th Cir.

1987).

In Allen, the Court said that "other factors, of course,

may require an exception to the normal rules of collateral

estoppel in particular cases." Id. at 95 n. 7. Kremer v.

Chemical Constr. Corp.. 456 U.S. 461 (1982) held: "The

state must, however, satisfy the applicable requirements

of the Due Process Clause. A state may not grant

preclusive effect in its own courts to a constitutionally

infirm judgment, and other state and federal courts are

not required to accord full faith and credit to such a

judgment." Kremer. supra. 456 U.S. at 482. Thus, "even

16

when issues...are preclusive under state law,

redetermination of [the] issues [may nevertheless be]

warranted if there is reason to doubt the quality,

extensiveness, or fairness of procedures followed in prior

litigation." Haring v. Prosise, 462 U.S. 306 (1983) at 317-

18. (1983) claim not barred by state preclusion rule for

failure to raise in prior litigation.) Here, the Camers were

barred on the theory they "could have discovered" the

violations earlier (but see Statement at 5, supra).. An

examination of the prior opinions in the appendix clearly

reveals that thiis is a case where the state court was

"unwilling or unable to prortect federal rights." Haring.

4 6 2 U . S . a t 3 1 4 , c i t i n g c a s e s .

It would obviously violate due process to bind Miki

Camer with the results of prior litigation to which she was

not party, and at which none of the facts or claims she

raises here were at issue. The fact that her mother was a

prior litigant of similar claims, and also appears in a

representative capacity here, cannot justify visiting the

sins of the parents upon the children. The requirements

for a finding of privity are clearly absent. See Moore’s

Federal Practice 0.411:

Nor should the interest of beneficiary C, whom F

represents by virtue of a separate fiduciary

relationship, be at stake when F litigates as

representative of B. This is the rationale

supporting the rule as to different capacities. And

it has been adopted by the Restatement.

(Restatement of Judgments (1942) 80b.")

A third major conflict with applicable federal

principles appears in the holding of the state Court of

Appeals that insufficient injury or damage is claimed for

plaintiffs to have "standing to bring a cause of action for

violation of constitutional provisions." Appendix A-13.

This is in direct conflict with Carey v, Piphus. 435 U.S. 247

(1978), a case brought against school board members for

violation of due process rights, in which the Court held

17

that a cause of action is stated even in the absence of

evidence of actual injury, justifying an award of at least

nominal damages. Declaratory and injunctive relief, as

well as attorney’s fees, would likewise be expected to

follow. While the Court in Carev held that damages are

not to be "presumed," the Court pointed out the

difference between presumed damages and inferred

damages. 435 U.S. at 264, n. 22. ("The Court’s comment

in Seaton, that ‘humiliation can be inferred from the

circumstances as well as established by the testimony,’

491 F.2d, at 636, suggests that the Court considered the

question of actual injury to be one of fact.") Numerous

cases are then cited upholding such "inferred damage"

awards. Id. And, of course, on a motion for summary

dismissal, as is in this case, a motion may not be granted

where the moving party’s submissions had not foreclosed

the possibility of the existence of certain facts from which

‘it would be open to a jury...to infer from the

circumstances’" that the elements of the claim had been

established." Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, 477 U.S. 242,

249 (1986), quoting Adickes v. Kress, 398 U.S. 144, 158

(1970).

As the Court concluded in Carev: "By making the

deprivation of such rights actionable for nominal damages

without proof of actual injury, the law recognizes the

importance to organized society that those rights be

scrupulously observed." 435 U.S. at 266.

The failure of the state courts in this case to observe

these rights, or to recognize and follow controlling federal

law, is a serious threat to the Supremacy Clause and the

continuing vitality of 42 United States Code 1983 as a

minimum safeguard for individual rights. If allowed to

stand, the decision below will leave low level school

administrators and officials free to arbitrarily deny

essential elements of education for any reason

whatsoever, or for no reason at all. The political efforts

leading to legislative reform mean nothing if the judiciary

18

leaves the executive free to ignore the law at its whim or

fancy. The promised benefits that justify compulsory

education, and the Due Process clause itself, become "a

teasing illusion, like a munificent bequest in a pauper’s

will." Edwards v. California. 314 U.S. 160,186 (1941).

Certiorari should be granted to remedy the important

conflicts with controlling decisions of this Court.

CONCLUSION

Date: May 25,1989.

Respectfully Submitted,

Dorothy Camer SMITH & MIDGLEY

9021 24th Ave SW

Seattle WA 98106

(206) 767-4229

Pro Sc Daniel Hoyt Smith

2200 Smith Tower

Seattle, WA 98104

(206) 682-1948

Counsel for Petitioners

A-l

APPENDIX A

DECISION

OF THE COURT OF APPEALS, DIVISION I

STATE OF WASHINGTON

Dorothy Camer,for herself and Miki Camer;Kirk Camer;

and Pepi Camer,Appellants v. Seattle School District No.l,

et al.,Respondents

No. 21269-9-1

52 Wn.App. 531, 762 P.2d 356 (1988)

Filed October 10, 1988

Scholfield, C. J. — Dorothy Camer and her three

children appeal the superior court judgment dismissing

their claims against the Seattle School District and

numerous named individuals. We affirm.

FACTS

On June 30,1986, Dorothy Camer and her three child

ren brought an action for declaratory judgment against the

Seattle School District and numerous named individuals.

By their complaint, the Camers sought a declaratory

judgment to test the adequacy of the conduct of school

district personnel with relation to their responsibilities

under Washington’s Basic Education Act. The complaint

alleged the violation of specific statutes, including the

failure of the Seattle Public Schools to teach the state con

stitution, lack of an adequate process for resolving grie

vances, failure to develop student learning assessments, use

of arbitrary procedures for discipline, failure to provide an

optimum learning atmosphere, failure of the principals to

supervise the educational program, failure to provide the

designated instruction, failure of the school directors to

enforce the laws, squandering of public funds, fraud and

conspiracy, failure of the District to provide for the safety

and welfare of students and failure of the District to

A-2

provide a uniform school system. By amendment to the

complaint filed September 23,1986, another defendant,

Jewell Woods, was added.

In April 1980, Dorothy Camer brought a suit against

the District,the Superintendent of Public Instruction (SPI),

and a number of District personnel (many of whom are

named as defendants in the present suit) on behalf of her

two children. Camer v. Brouillet. (King County Cause No.

80-2-05307-8), affd. 31 Wn. App. 1097, review denied, 97

Wn. 2d 1042 (1982). She objected to the fashion in which

the District had implemented the student learning objec

tives (SLO’s) law, RCW 28A.58.090, and the Washington

Basic Education Act of 1977,RCW 28A.58.750. Mrs.Camer

asserted that both children had been denied adequate in

struction, that her children’s schools had failed to provide a

"healthy environment conducive to education" and a

program to meet the "individual and collective needs of the

plaintiffs and their fellow students," and that the children

had been denied their right to a basic education under the

Washington Constitution, article 9, section 1. She further

asserted her frustration with available administrative

processes. She sought damages and a declaratory judgment

on basic education as defined by the SLOs, and prayed for

relief based on RCW 28A.58.750 et seq. Summary judg

ment was granted against Mrs.Camer. The judgment was

affirmed by the Court of Appeals, which denied Mrs.Cam-

er’s claim for a declaratory judgment on the ground no

justiciable controversy was present. The court also held she

had no standing to bring a private cause of action under the

SLOs, and that she had no standing to sue for educational

malpractice. The Supreme Court denied review.

Mrs. Camer brought a similar suit in federal court,

including among the defendants the Attorney General, the

King County Prosecuting Attorney, the SPI, and other

school officials. Camer v. Eikenberrv. U. S. Dist. Ct. Cause

No. C81-682M (W.D. Wash. 1982), affd . 703 F.2d 574 (9th

Cir. 1983), cert, denied. 464 U.S. 828 (1983). In the federal

A-3

action, Mrs. Camer alleged that her son Kirk had been

denied equal access to programs offered by the District and

had been denied instruction in various elements of the

published curriculum necessary to attain the SLOs for his

grade, including those related to Washington State

government. The United States District Court dismissed

the case, and the dismissal was affirmed by the Ninth Cir

cuit in an unpublished opinion. The United States

Supreme Court denied certiorari.

On December 15, 1986, the trial court entered an

order of dismissal and summary judgment dismissing all of

the Carners’ claims in the present action, but reserving to

the Carners the opportunity to replead their claims of fraud

and conspiracy within 30 days. The trial court granted

attorney’s fees to defendants on the ground that a number

of the Carners’ allegations and claims were frivolous and

specifically found that the Carners second amended

complaint seeking to add Jewell Woods as a defendant was

frivolous on its face.

On January 14, 1987, the Carners repleaded their

claims of fraud and conspiracy. On March 18, 1987, the

court filed an order of dismissal and summary judgment

regarding the fraud and conspiracy claims. This appeal

timely followed. The Carners first sought direct review

from the Washington Supreme Court, which was denied.

RES JUDICATA

Res judicata ensures the finality of decisions. A final

judgment on the merits bars parties or their privies from

relitigating issues that were or could have been raised in

that action. Mellor v. Chamberlin. 100 Wn 2nd, 643, 645,

673 P.2d 610 (1983). The rule is stated as follows:

In Washington res judicata occurs when a prior

judgment has a concurrence of identity in four

respects with a subsequent action. There must be

A-4

identity of (1) subject matter; (2) cause of action; (3)

persons and parties; and (4) the quality of the persons

for or against whom the claim is made.

Mellor v. Chamberlin, supra at 645.

In applying these criteria to the facts at bar, we find

that this case is barred by the doctrine of res judicata. The

present case and Camer v. Brouillet. supra are so

substantially similar that there is no clear basis for

distinguishing them. First, in both cases the subject matter

pertains to the adequacy of the manner in which school

administrators are implementing the constitutional and

statutory directives regarding education. Secondly,

although the cause of action is not phrased in identical

terms, in both cases the plaintiffs essentially argued the

same issue--that the school district and administrators are

not following statutory and constitutional requirements

regarding curriculum and administration. The same

statutes and constitutional provisions are relied upon in

both cases. Furthermore, their claim that the Washington

State Constitution was not taught could have been raised in

a prior lawsuit, even though no Camer child had yet

graduated, because at the time of the suit they could have

discovered whether teaching the state constitution was in

the curriculum. Third, although an additional Camer child

is a plaintiff in the present action, we hold that the persons

and parties are essentially the same. Counsel for Camer

claims that res judicata does not apply because Miki, a 13-

year-old child named as plaintiff in this case, was not

involved in any of the previous cases. However, the quality

of the plaintiff is the same in both cases. See Rains v. State.

100 Wn.2d 660, 664, 674 P.2d 165 (1983). If we adopted

the Camers’ reasoning on this issue, each time another

Camer child entered the Seattle school system, they would

have the right to bring exactly the same complaint and have

it heard through the judicial system. Finally, the persons

against whom the claim is made, the District, adminis

trators, and teachers are qualitatively the same parties for

A-5

purposes of applying the doctrine of res judicata. See

Rains v. State, supra. The Camers may not now relitigate

issues that were or could have been raised in the prior

actions.

PRIVATE CAUSE OF ACTION

The next issue before us is whether RCW 28A.02.080

and RCW 28A.05.050 create a judicially enforceable duty,

on the part of local school districts, to teach the state

constitution to public school students. We find that the

Camers have not shown that a private right of action exists.

RCW 28A.02.080 provides in relevant part that the

study of the Constitution of the State of Washington shall

be a condition prerequisite to graduation from the public

and private high schools of this state. RCW 28A.05.050

requires the State Board of Education to prescribe a 1-year

course of study in the history and government of the United

States, and the equivalent of a 1-semester course of the

study of the State of Washington’s history and government.

Accordingly, WAC 180-50-120 and -130 were adopted,

which require all schools to provide a 1-semester high

school level course in Washington history and government,

including "a study of the Washington state Constitution",

WAC 180-50-120(2), and a similar 1-year course in United

States history and government. The Camers argue that the

Seattle School District does not comply with these

requirements.

In Cort v. Ash. 422 U.S. 66, 78, 45 L.ED. 2d 266, 95 S.

Ct 2080 (1^75), the Court adopted the following test for

determining whether a private remedy is implicit in a

statute not expressly providing one:

In determining whether a private remedy is implicit in

a stature not expressly providing one, several factors

are relevant. First, is the plaintiff "one of the class for

whose especial benefit the statute was enacted," . . .

A-6

Second, is thee any indication of legislative intent,

explicit or implicit, either to create such a remedy or

to deny one? . . . Third, is it consistent with the under

lying purposes of the legislative scheme to imply such

a remedy for the plaintiff? . . . And finally, is the cause

of action one traditionally relegated to state law, in an

area basically the concern of the States, so that it

would be inappropriate to infer a cause of action

based solely on federal law? (Citations omitted.)

Assuming for the sake of argument that the Camers

are within the class for whose especial benefit the statute

was enacted, the language of the statutes cited by Camer is

devoid of any expression or indication of an intent on the

part of the Legislature to create a private cause of action

for damages. Nor has Camer cited legislative history show

ing such a legislative intent.

Generally, the statutory scheme indicates to the

contrary. RCW 28A.58.090 provides for periodic reviews

of curriculum and the SLOs by school district boards of

directors, the SPI, and the State Board of Education.

These matters are, by practical necessity, largely discre

tionary with those charged with the responsibilities of

school administration. Courts and judges are normally not

in a position to substitute their judgment for that of school

authorities, Millikan v. Board of Directors. 93 Wn.2d 522,

611 P.2d 414 (1980), nor are we equipped to oversee and

monitor day-to-day operations of a school system.

Moreover, implying a private cause of action would not

be consistent with the purposes of a legislative scheme,

which seeks to set up general guidelines for producing an

ample education for Washington state citizens as mandated

by Const., art. 9, section 1, to be administered within the

discretion of the school board and its officers. The legisla

ture has limited judicial review to designated persons

aggrieved "by any decision or order of any school official or

board ..." RCW 28A.88.010.

A-7

The present administrative setup involving the Board

of Education and the Superintendent of Public Education,

provides a proper chain of accountability for education and

is adequate to address the problems. Finally, the Legis

lature can impose sanctions against the district that fails to

comply in the discharge of its duties by withholding its

funding. WAC 180-16-195(3).

The Carners’ allegations do not state a cause of action

arising under either the Washington or the United States

Constitutions. Const, art. 9, section 1 imposes a judicially

enforceable affirmative duty on the State to make ample

provision for the education of children. Seattle School

Dist. 1 v. State. 90 Wn.2d 476, 585 P.2d 71 (1978). The

Carners do not allege facts which constitute a violation of

this provision. Nor do the Carners show actual damage or

injury, and therefore, they have no standing to bring a

cause of action for violation of constitutional provisions.

See Seattle School Dist. 1 v. State, supra at 494.

The Carners also make additional assignments of error.

First, the Carners assign error to the trial court’s finding

that most of the actions or inactions alleged by the Carners

fall within the broad discretionary authority of the Seattle

School District, its administrators, and its certified staff, all

of whom are public officers and therefore are immune from

liability for such decisions. Next, the Carners assign error to

the trial courts’s finding that the Carners did not make

proper service on any of the individuals defendants except

Kenneth Dorsett, Michael Hoge, William Kendrick, Chris

Kato, David Stevens, Jewell Woods and Elizabeth Wales.

The Carners also assert that the trial court erred in finding

that their claims against the individual defendants were

barred by the statute of limitations. Finally, the Carners

argue that the trial court erred in finding that the Carners

failed to state a claim for fraud and in finding that the

Carners cannot recover for educational malpractice.

A-8

It serves no purpose to discuss these assignments

individually, when all of them are disposed of by our

holding that this action is barred by res judicata and that

there is no private cause of action for the complaints that

the Camers make in this case.

FRIVOLOUS CLAIM AS TO JEWELL WOODS

The Camers also argue that their claim as to Jewell

Woods was not frivolous and that an award of attorney’s

fees is unauthorized prior to litigation.

Former RCW 4.84.185 states in pertinent part:

In any civil action, the court having jurisdiction may,

upon final judgment and written findings by the trial

judge that the action . . . was frivolous and advanced

without reasonable cause, require the nonprevailing

party to pay the prevailing party the reasonable

expenses, including fees of attorneys, incurred in

opposing such action . . .

The Camers cite Whetstone v. Olson. 46 Wn App 308, 732

P.2d 159 (1986) as support for their argument that attor

ney’s fees may not be awarded under RCW 4.84.185 for de

fending a frivolous action when the case is dismissed prior

to the plaintiffs’ presentation of their entire case. How

ever, RCW 4.84.185 was amended in 1987 to include orders

on summary judgment.

Statutes generally operate prospectively unless

remedial in nature. A statute is remedial when it relates to

practice, procedure or remedies and does not affect a sub

stantive or vested right. Miebach v. Colasurdo. 102 Wn.2d

170, 180-181, 685 P.2d 1074 (1984). We deem attorney’s

fees to be remedial in nature and therefore give the statute

retroactive effect.

A-9

In the present case, the amended complaint adding

Jewell Woods as a defendant alleged that Woods arrived

late to an appointment with Mrs. Camer and refused to

allow Mrs. Camer to copy her lesson plans, which con

tained no material covering the constitution. These facts

do not state a cause of action that can be supported by any

rational argument on the law or facts. Therefore, we find

that the trial court did not abuse its discretion in awarding

attorney’s fees to Woods.

FRIVOLOUS APPEAL

RAP 18.9(a) authorizes the appellate court, on its own

initiative, to order sanctions against a party who brings an

appeal for the purpose of delay. Sanctions may include, as

compensatory damages,an award of attorney’s fees to the

opposing party. See RAP 18.9, Comment, 86 Wn.2d 1272

(1976); Bill of Rights Legal Found, v. Evergreen State

College. 44 Wn App. 690,723 P.2d 483 (1986). In determin

ing whether an appeal is brought for delay under RAP

18.9(a), "our primary inquiry is whether, when considering

the record as a whole, the appeal is frivolous,re., whether it

presents no debatable issues and is so devoid of merit that

there is no reasonable possibility of reversal." Streater v.

White,26 Wn.App.430, 434, 613 P.2d 187 (1980). All doubts

as to whether an appeal is frivolous should be resolved in

favor of the appellant. Streater v. White, supra at 435.

In applying these criteria, we find that this appeal is

frivolous. This case presents essentially the same claims

and issues on which the Camers were defeated in two prior

cases. Nevertheless, the Camers have persisted in appeal

ing this case even though they present no debatable issues

and their position is so devoid of merit that there is no

possibility of reversal.

Judgment affirmed.

A-10

ORDER

OF THE SUPREME COURT OF WASHINGTON

Camer, et al, Petitioners, v. Seattle School District 1, et

al, Respondents, No. 55807-8. Petition for review of a

decision of the Court of Appeals, Oct. 10, 1988, 52 Wn App

531. Denied Feb. 28, 1989.

MANDATE OF THE COURT OF APPEALS

OF THE STATE OF WASHINGTON

No. 21269-9-1 Camer v. Seattle School

The State of Washington to: The Superior Court of the

State of Washington in and for King County.

This is to certify that the opinion of the Court of

Appeals of the State of Washington, Division I, filed on

October 10, 1988 became the decision terminating review

of this court in the above entitled case on March 17, 1989.

This cause is mandated to the superior court from which

the appeal was taken for further proceedings in accordance

with the attached true copy of the opinion.

Mandate after opinion is filed. Petition for review

denied on February 28, 1989. Order denying motion for

reconsideration entered on December 7, 1989. Pursuant to

a commissioner’s ruling entered on Novem ber 2, 1988, it is

ordered that costs in the amount of Five hundred Thirty-

Two and 17/100 ($532.17) shall be taxed against appellants

Camer in favor respondent Seattle School District No. 1;

no costs awarded to respondent Sonia Watson.

B-l

APPENDIX B

SUPERIOR COURT OF WASHINGTON

FOR KING COUNTY

Dorothy Camer,for herself and Miki Camer; Kirk Camer;

and Pepi Camer, Plaintiffs v. Seattle School District No.l et

al., Defendants

No. 86-2-11966-3

ORDER OF DISMISSAL AND SUMMARY

JUDGMENT

THIS MATTER, having come on for hearing before

the undersigned Judge Gerard M. Shellan on November

13„ 1986, on motions of defendant Seattle School District

No. 1 and other served defendants for dismissal or

summary judgment, for dismissal of claims against

individual defendants, and for dismissal of claims of fraud

and conspiracy; and, on December 15, 1986, on further

motion of defendants for attorneys’ fees and terms; defen

dants having been represented at the hearings on said

motions by Karr, Tuttle, Koch, Campbell, Mawer, Morrow

& Sax, P.S. and Lawrence B. Ransom, and Brown-Mathews

and Jackie R. Brown,, their attorneys; plaintiffs appearing

at said hearing through plaintiff Dorothy Camer, pro se;

the court having heard the arguments of counsel and the

pro se plaintiffs; and the court having reviewed and

considered the following:

Plaintiffs’ petition for declaratory judgment, violation

of civil rights and other relief; Plaintiffs’ amended

summons; Plaintiffs’ second amendment to complaint; Affi

davits of service submitted by plaintiffs; defendants’ motion

to dismiss claims against individual defendants, together

with attachments which included alleged affidavits of

service; sworn statement by Michael Hoge in support of

defendants’ motion for dismissal or for summary judgment;

defendants’ memorandum in support of motion for

B-2

dismissal or summary judgment, together with attachments

A to K, which include prior litigation,, court orders and

correspondence; defendants’ reply memorandum in

support of motion for summary judgment; defendants’

supplemental memorandum in support of motion to

dismiss claims against individual defendants; ’supplemental

memorandum in support of motion to dismiss fraud and

conspiracy claims, together with Exhibit A attached to it,

which is a letter; plaintiffs memorandum opposing

dismissal of individual defendants; affidavit of Joan Marie

White; plaintiffs memorandum opposing dismissal of fraud

and conspiracy charges, to which is attached the transcript

of an oral decision of the superior court arising out of the

1982 cause, Camer v. Stevens: affidavit of the plaintiff

regarding when she realized defendants’ activities

constituted a fraud; plaintiffs’ memorandum opposing

dismissal or summary judgment, with attachment which in

cludes a copy of a judgment arising under the 1982 cause,

Camer v. Stevens: affidavit of the plaintiff opposing

summary judgment; affidavit of Kirk Camer; affidavit of

Miki Camer, with attachments; affidavit of L. Christine

Foss; affidavit of Rochelle V. Leopard, with attachments

and correspondence; affidavit of Barbara E. Robertson,

with attachments; affidavit of Patricia L. Turner, with

attachment, including letters from Group Health and

certain exhibits; affidavit of Karimu White; affidavit of

Malika M. White; affidavit of Nancy A. Winston, with

attachments; corrections to plaintiffs memoranda opposing

defendant’s motion to dismiss for various reasons, together

with attachments; affidavit of Pepi Camer, with

attachments; supplement to memorandum opposing

defendants’ motion to dismiss for various reasons, together

with a second affidavit of the plaintiff to support

memoranda opposing dismissal; and all other papers

properly filed by any party to these proceedings; and the

court being otherwise fully advised; now therefore,

The court does make the following FINDINGS AND

CONCLUSIONS:

B-3

1. Many of the issues raised by plaintiffs in this case are

the same or similar to those that were raised in previous

cases brought by the same plaintiff: Camer v. Brouillet.

King County Cause No. 80-2-05307-8, (Oct. 8, 1980),, affd

by unpublished opinion. 21 Wn. App. 1097 (1982), and

Camer v. Eikenberrv. United States District Court Cause

No. ' C81-682M. (W.D. Wash. 1982), a f f ' d by

unpublished opinion. 703 F.2d 574 (9th Cir. 1983), cert

denied, 464 U.S. 828, 104 S.Ct. 102„ 78 L.Ed. 2d 106

(1983).

2. Plaintiffs’ allegation of fraud and conspiracy have

not been pleaded with the particularity required under Civil

Rule 9(b).

3. Plaintiffs’ allegations, and the record before this

court, do not contain any showing of damages to any

plaintiff or any of the plaintiffs children.

4. Plaintiffs’ allegations do not state an individual

private cause of action for educational malpractice, and

Washington courts do not in any event recognize an

individual cause of action for educational malpractice.

5. Plaintiffs’ allegations do not state a private cause of

action under Chapter 28A RCW in general,, under

Washington’s Basic Education Act in particular, or under

any other state or federal statutes.

6. Plaintiffs allegations do not state a cause of action

arising under either the Washington or the United States

Constitutions.

7. Most of the actions or inactions alleged by plaintiffs

fall within the broad discretionary authority of the Seattle

School District, its administrators, and its certificated staff,

all of whom are public officers.

B-4

8. The court is not equipped to oversee and monitor

day-to-day operations of a public school system.

9. None of plaintiffs’ allegations of fraud, conspiracy,

improprieties,, wasting of funds, lack of discipline, or lack

of due process rises to an actionable valid cause of action

which can be brought by a private individual.

10. To the extent that plaintiffs’ allegations do state

valid complaints against the Seattle School District or its

administrators or certified staff, litigation of such

complaints is barred by the 30-day limitations period set

forth in RCW 28A.88.010.

11. A number of the plaintiffs’ allegations and claims

are frivolous.

12. Plaintiffs’ second amended complaint, seeking to

add Jewell Woods as a defendant, is frivolous on its face.

13. Plaintiffs have not made personal service of original

process in the manner required by Civil Rule 4 and

applicable state statutes on any of the individual defendants

except Kenneth Dorsett, Michael Hoge, William Kendrick,

Chris Kato, David Stevens, Jewell Woods and Elizabeth

Wales.

14. There are no genuine issues of material fact

remaining for trial.

NOW THEREFORE, on the basis of the foregoing

findings and conclusions,

IT IS HEREBY ORDERED, ADJUDGED, AND

DECREED as follows;

1. Defendants’ motion for dismissal is granted;

2. Defendants’ motion for summary judgment is

granted;

B-5

3. Defendants’ motion for dismissal of claims against

individual defendants is granted against all individual

defendants for the reason that the allegations against the

individual defendants are based on exercise of discretion by

said defendants.

4. Defendants’ motion for dismissal of claims against

individual defendants is granted as to all defendants except

Kenneth Dorsett, Michael Hoge, William Kendrick, Chris

Kato, David Stevens,, Jewell Woods,, and Elizabeth Wales

for the reason that all except these seven listed defendants

have not been personally served with original process.

5. Defendants’ motion to dismiss claims of fraud and

conspiracy is granted and all plaintiffs’ claims of fraud and

conspiracy are hereby stricken and dismissed; provide that,

the court shall retain jurisdiction for thirty (30) days from

the date of this order to provide plaintiffs with the requisite

particularity, if plaintiffs wish to attempt to do so.

6. Defendants’ motion for attorneys’ fees and terms

based on frivolous claims is granted.

7. Defendants shall recover from plaintiffs the sum of

$250.00 for terms and attorneys’ fees and $125.00 for

taxable costs, for a total judgment against plaintiffs and in

favor of defendants in the amount of $375.00.

8. The clerk of the court is directed to enter judgment

in favor of defendants in this matter consistent with the

above orders.

DONE IN OPEN COURT this 15th day of December,

1986.

Signed by Gerard N. Shellan, Judge

Prepared by Lawrence B. Ransom, Attorney for

defendant.

B-6

SUPERIOR COURT OF WASHINGTON

FOR KING COUNTY

Dorothy Camer, or herself and Miki Camer; Kirk Camer;

and Pepi Camer, Plaintiffs v. Seattle School District No.l et

al., Defendants

No. 86-2-11966-3

ORDER OF DISMISSAL AND

SUMMARY JUDGMENT

REGARDING FRAUD AND CONSPIRACY CLAIMS

THIS MATTER, having come on for hearing before

the undersigned Judge Gerard M. Shellan on March 18,

1987, on motion of defendant Seattle School District No. 1

and other served defendants for dismissal or summary

judgment on plaintiffs’ claims of fraud and conspiracy;

defendants having been represented at the hearing on said

motions by Karr, Tuttle, Koch, Campbell, Mawer, Morrow

& Sax, P.S. and Lawrence B. Ransom, their attorneys;

plaintiffs appearing at said hearing through plaintiff

Dorothy Camer, pro se: the court having heard the

arguments of counsel and the pro se plaintiff and the court

having reviewed and considered the following:

1. Defendants Motion for Dismissal or Summary

Judgment on Plaintiffs’ Claims of Fraud and Conspiracy;

2. Plaintiffs’ statement of Particularities of Fraud, filed

on January 14,1987, including all attachments thereto;

3. All of the materials that were considered by the

court as referenced in the court’s Order of Dismissal and

Summary Judgment dated December 15, 1986; and

4. All other papers properly filed by any party to these

proceedings;

and the court being otherwise fully advised;

B-7

NOW THEREFORE, the court does reach the

following Conclusions:

1. There are no genuine issues of material fact

regarding plaintiffs’ claims based on allegations of fraud

and conspiracy;

2. Defendants are entitled to judgment as a matter of

law on all of plaintiffs’ claims based on allegations of fraud

and conspiracy.

NOW THEREFORE, on the basis of the foregoing

conclusions, IT IS HEREBY ORDERED, ADJUDGED,

AND DECREED as follows:

1. Defendants’ Motion for Dismissal or Summary

Judgment on Plaintiffs’ Claims of Fraud and Conspiracy is

granted;

2. Defendants shall not be entitled to any further

affirmative relief at the trial court level, including costs and

attorneys’ fees, other than as set forth in the court’s Order

of Dismissal and Summary Judgment dated December 15,

1986;

3. Combining this Order with the court’s Order of

Dismissal and Summary Judgment dated December 15,

1986, all of the plaintiffs claims against all defendants are

now, finally, dismissed with prejudice.

DONE IN OPEN COURT this 18th day of March,

1987.

Signed: Gerard M. Shellan, Judge

Prepared by: Lawrence B. Ransom, Attorney for the

Defendants

i

C-l

APPENDIX C

DECISION

OF THE COURT OF APPEALS, DIVISION I,

STATE OF WASHINGTON

Dorothy Camer, for herself and Kirk Camer and Pepi

Camer, Appellants v. Frank Brouillet et al., Respondents

No. 10227-3-1, Unpublished

Filed June 7,1982

CORBETT, J. — Dorothy Camer, individually and as a

parent and guardian, appeals a summary judgment that

dismissed her complaint seeking damages for the alleged

denial of a basic education for her children.

The complaint alleges that in June of 1979, Kirk