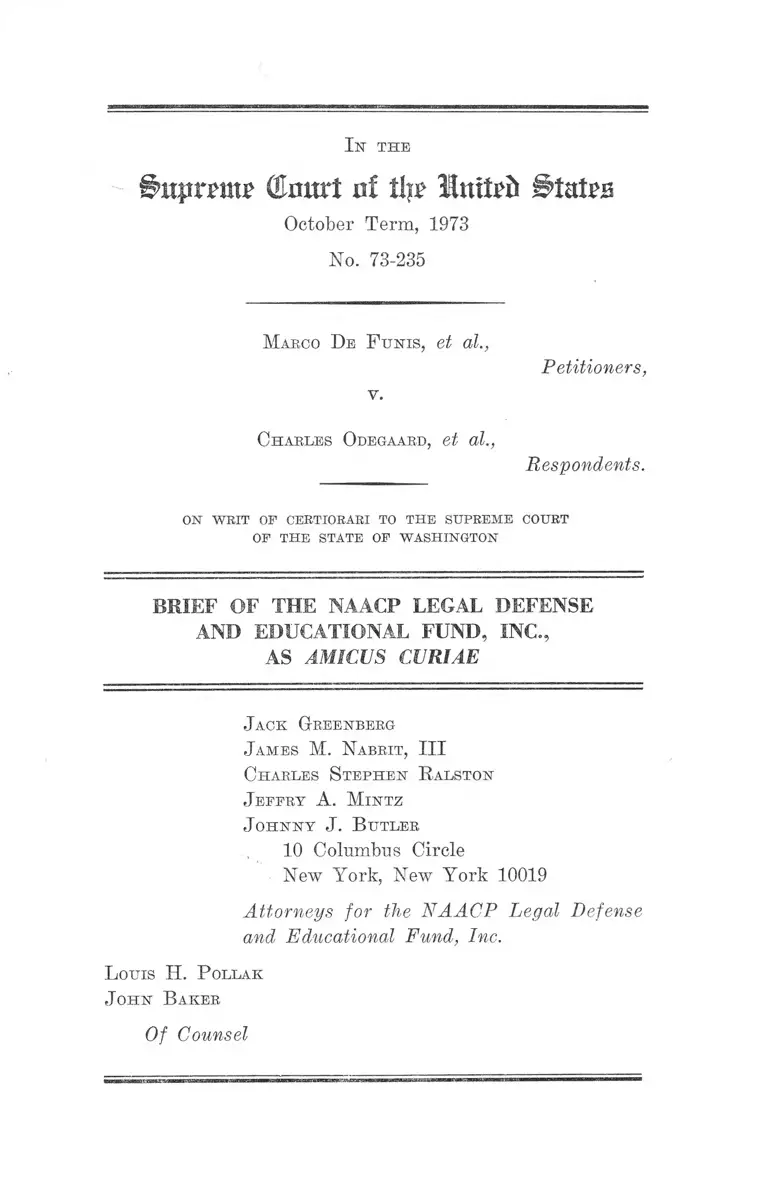

DeFunis v. Odegaard Brief Amicus Curiae of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. DeFunis v. Odegaard Brief Amicus Curiae of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, 1973. 46f26089-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a365aff1-738b-47c0-939f-1d96ef509779/defunis-v-odegaard-brief-amicus-curiae-of-the-naacp-legal-defense-fund. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

In th e

Buptmw ©mart rtf tlj? llmh'ii §>tatra

October Term, 1973

No. 73-235

M arco D e F u n is , et al.,

Petitioners,

Y.

C harles O degaard, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OP THE STATE OP WASHINGTON

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AS AMICUS CURIAE

.Jack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

C harles S te p h e n R alston

J effry A. M in t z

J o h n n y J . B utler

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

Louis II. P ollak

J o h n B aker

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Interest of the Amicus .................................................... 1

A rgu m en t

I. The Minority G-roup Admissions Policies of

the University of Washington School of Law

Are Constitutional ........................... 4

II. The Minority Admissions Program Does Not

Violate Title VI .................................................. 10

C onclusion ....................................................................................... 12

A p p e n d ix .................................................................. -.......................... l a

T able op Cases

Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973) 4n

Alabama v. United States, 304 F.2d 583, aff’cl, 371 U.S.

37 (1962) ........... 7n

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167 (2nd

Cir. 1972) .................... 5n

Contractor Ass’n of Eastern Pa. v. Secretary of Labor,

442 F.2d 159 (3rd Cir. 1971)........................................ 3

Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. 424 (1971) .. 6n

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954) .................. 5n

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) ............... . 9n

Lan v. Nichols, ------U.S. ------- , 42 U.S.L. Week 4165

(Jan. 21, 1974) ............................................................... 10

PAGE

XI

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) In

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963)......................2n, 9n

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970) ...................... 7n

Bailway Mail Ass’n v. Corsi, 326 U.S. 88 (1945) ....... 9

Sanders v. Bussell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968).......2n, 9n

Sobol v. Perez, 289 F.Supp. 392 (E.D. La. 1968) ........... 9n

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 402 U.S.

1 (1971) ........................ ..... ........ ................................... 8

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) .......................... In

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205

(1973) ................... ............................................... ......... 10n

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970) ...................... 7n

United States v. Montgomery County Bd. of Ed., 395

U.S. 225 (1969) ............... ......................................... . 3

Welsh v. United States, 398 U.S. 333 (1970) ............... 9n

S t a t u t e s :

20 U.S.C. §1619(9) (A) .............. ....................... .............. 5n

42 U.S.C. §2000(d) ........... ............................................. 10n

45 C.F.R. 80.3 (1973) ....................................................... 10

Civil Rights Act of 1964, §601 .......... ............................ 10

Oth er A u t h o r it ie s :

Carl, The Shortage of Negro Lawyers: Pluralistic

Legal Education and Legal Services for the Poor,

20 J. Legal Ed. 21 (1967) ............ .............................. 2n

PAGE

Ill

Gellhorn, The Law School and the Negro, 1968 Duke

PAGE

L.J. 1069 ........................................ _____............. ..........__. 2n

Leonard, The Development of the Black Bar, 407 T he

A n n als 134 (1973) ............... ................____................................ In

McGee, Black Lawyers and the Struggle for Racial

Justice in the American Social Order, 20 Buffalo L.

Lev. 423 (1971) ............. ................. ......... ............... 2n

Parker & Stebman, Legal Education for Blacks, 407

T h e A n n als 144 (1973) ................. .................... ................ 2n

I n th e

(tart nf tlj? Itritefc States

October Term, 1973

No. 73-235

M arco D e F u n is , et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

C harles Odegaard, et al.,

Respondents.

o n w rit o r certiorari to th e supreme court

OF THE STATE OF WASHINGTON

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Interest o f the Amicus1

Amicus, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., is interested in the present case for several reasons.

First, the black community has been grossly underrepre

sented in terms of the number of black attorneys available.

To a large extent, this was due to deliberate discrimina

tion.2 As recently as 1968, only about one percent of the

1 Letters of consent from counsel for the petitioners and the

respondents have been filed with the Clerk of the Court.

2 See, e.g., Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) ;

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950); and see Leonard, The

Development of the Black Bar, 407 The A nnals 134, 137-39

(1973).

2

total number of attorneys in the United States were black,

a figure probably not substantially higher than in 1900.3

Recent figures indicate that slightly over seven percent of

total law school enrollment in the last year is minority

students, including blacks, Chicanos, American Indians,

Puerto Ricans, etc.4 5

In the Legal Defense Fund’s experience the need for

black (and other minority group) lawyers to serve their

own community is clear. Although lawyers of all races

have made many contributions to the cause of equal justice,

it is essential that there be black lawyers who live and

practice law day to day and year after year as integral

parts of their communities.6 In the main and over the

long run, they are most disposed to and capable of per

forming services for the minorities of which they are a

part.6 Lawyers are critical to political activity, building

businesses, and social development, to say nothing of legal

representation in resolving public and private differences.

Without an adequate number of lawyers, minority prog

ress in all these areas will be stunted.

In order to help increase the number of black, lawyers,

the Legal Defense Fund administers, through its subsid

iary, the Earl Warren Legal Training Program, Inc., pro

grams to provide scholarships for black law students and

3 Gellhorn, The Law Schools and the Negro, 1968 Duke L.J. 1069.

4 In 1972-73, there were 4,423 black students, or 4.3% of the

total enrollment. This was up from only 1,254 in 1968-69. Parker

& Stebman, Legal Education for Blacks, 407 The A nnals 144, 147

(1973).

5 See Carl, The Shortage of Negro Lawyers: Pluralistic Legal

Education and Legal Services for the Poor, 20 J. Legal Bd. 21

(1967); McGee, Black Lawyers and the Struggle for Racial Justice

in the American Social Order, 20 Buffalo L. Rev. 423 (1971).

6 See, NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963); Sanders v. Rus

sell, 401 F.2d 241 15th Cir. 1968).

3

assistance to black law graduates seeking to set up practice

in communities without sufficient legal representation.

Obviously, for the success of these programs there must

be significant numbers of black law students. Over the

past few years, which coincide with institution of affirma

tive admission programs like that at the University of

Washington Law School, the Fund has had a substantial

increase in the number of applications for both programs

from highly qualified black students.7

The second interest of the Legal Defense Fund in this

case arises from the possible implications of this case for

a wide range of litigation. A reversal not only could under

mine voluntary programs to achieve the reality (and not

merely the appearance) of equal opportunity, but also

could cut back sharply on the remedial powers of courts

(see, e.g., United States v. Montgomery County Board of

Education, 395 U.S. 225 (1969)) and agencies (see, e.g.,

Contractor Ass’n of Eastern Pa. v. Secretary of Labor, 442

F.2d 159 (3rd Cir. 1971) to require affirmative action.8

7 Between 1967 and 1973 over two hundred and thirty black

students who were recipients of scholarship assistance from the

Fund graduated from law schools. These recipients and graduates

have matriculated at forty-five of the major law schools in the

East, South and Mid-West, and at both national and regional law

schools. At present more than three hundred and sixty are en

rolled in the program.

During the same span of years the Legal Defense Fund has

trained or has in training in its post-graduate fellowship program

over eighty young lawyers for civil rights practice. They have

distinguished themselves professionally, in politics, business and

civic affairs. In each of the last two years the Fund has had

almost two hundred applicants for twelve positions. Comparable

ratios prevail with respect to applicants for scholarships.

8 The question which arises in this case, in a Northern state,

implicates also the South. In the South, where higher education

remained segregated by law in many places until well after this

Court’s decision in Brown, effective steps to dismantle the dual

system in many colleges and universities are just now commencing.

4

ARGUMENT

I.

The Minority Group Admissions Policies o f the Uni

versity o f Washington School o f Law Are Constitutional.

It is important to focus precisely on what the University

of Washington Law School was doing, and what peti

tioner Marco De Funis, Jr., may complain about. The

School was faced with the problem of deciding which of a

large group of qualified9 applicants it should admit. These

decisions were made by a complex process; applicants

could not, as petitioner De Funis urges, be chosen by the

rigid application of mathematical formulae. A small group

of students were more or less automatically admitted if

they had a high Predicted First-Year Average (PFYA).

These steps were occasioned by Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d

1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973), which the undersigned amicus sponsored.

_ It would be a misfortune were this case to give rise to any prin

ciples which might hinder the fullest desegregation process in

higher education in Southern and border states. Recently, in its

responses to the previously submitted desegregation plans, which

it found inadequate, the Department of Health, Education, and

Welfare made clear that affirmative remedial measures must be

undertaken to achieve black access to public higher education;

these measures will have to be complex and far-reaching to achieve

desegregation in fact.

9 Both petitioners and certain of their supporting amici attempt

to raise the specter of law schools admitting large numbers of

unqualified black and other minority students with the result of

excluding qualified whites and eventually foisting unqualified attor

neys on the black community. There is no basis in the record to

substantiate such a contention with regard to the University of

Washington. All the testimony clearly indicates that in every

instance persons were admitted who were reasonably believed to

be qualified and capable of succeeding in law school and as lawyers.

5

Everyone else, inclnding De Funis and most of the minority

group students, went through further processing.10

De Funis’ complaint arises because in that processing

minority group students were handled separately from

majority group students.11 All applications from minority

group members were given to two particular admissions

committee members who compared the applications against

each other. Majority group applications similarly were

compared with each other. The most promising in each

group were chosen and the two lists aggregated.

As to both groups much more than PFTA was con

sidered, as indeed was proper. After all, the scale only

purported to predict what grades a student would make

in his first year of law school; it did not even predict his

performance throughout law school or on a bar examina

tion. It manifestly could not measure criteria at least as

legitimate as the grades an applicant would receive in law

school, viz., his long term success and contributions to the

profession and the community. These more difficult predic

tions were made on the basis of not only PFTA, but also

by weighing factors such as extracurricular activities,

interest in community affairs, letters of recommendation,

and the type of undergraduate curriculum pursued. As a

result, a number of majority group applicants with lower

10 Thus, this case does not involve anything analogous to the

“merit system,” or an attack on it. A PFYA score cannot be

equated with a score on a Civil Service examination, a typing test,

or a driving test. Certainly, regardless of whether a strict merit

system based on tests may be used under certain circumstances

(see, Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167 (2nd Cir.

1972)), there is no constitutional requirement that it must be.

11 At least one amicus professes difficulty with the concept of

defining certain persons as members of “minority groups.” This

has presented no problem, however, either to Congress (see, 20

U.S.C. § 1619(9) (A ), or to this Court. See, Hernandez v. Texas,

347 U.S. 475 (1954) .

6

PFYA’s than De Funis were admitted or put on the wait

ing list ahead of him.12

The question, therefore, is whether the procedure now13

complained of by De Funis, that minority students and

majority students were compared only with others in the

same group, violated his constitutional rights. Simply

stated, the School recognized that the PFYA is significantly

less predictive of what it purports to measure for minority

than for non-minority students, largely because of historic

educational and social discrimination. This was the expert

testimony at trial (St. 128-131) and petitioner did not rebut

it. Just as the number of minority students .admitted to the

University as a whole had been limited by the application

of standard criteria, as the President of the University

testified (St. 222-229), it could be expected that if the same

weight was given to the PFYA for both groups, it would

operate as a “built-in headwind” 14 resulting in exclusion of

minorities from the Law School.

12 This fact is significant, since even if there had been no minority

admissions program this record does not demonstrate that De

Funis would have been admitted to law school. He was in the

lowest one-fourth of the waiting list, with at least fifty-five persons

ahead of him; thirty-six minority group applicants with PFYA ’s

lower than De Funis were sent letters of acceptance, and only

eighteen accepted; even if none had accepted he apparently would

not have been reached.

13 The original complaint did not challenge his exclusion on

racial grounds. In addition to the in-state resident issue, the com

plaint urged, in essence, a denial of due process because others

had arbitrarily been admitted to the school even though they had

lesser qualifications than did petitioner (A. 14-15; 17). The ques

tion of minority students was raised as a matter of defense (over

the objection of petitioner’s counsel (St. 230-231)) by the Law

School to explain why some, with lesser paper qualifications than

De Funis were admitted before he was. Much of the dissenting

opinion below was an attack on the procedures and standards used

generally to select among the applicants. Whatever might be the

merits of a due process attack on the method of administering the

selection system, one has not been presented here.

14 Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 432 (1971).

7

The School, therefore, took a course that was not only

prudent, hut perhaps constitutionally required. If it did

not institute appropriate differential treatment of minority

applicants, a combination of a low minority acceptance

rate,15 and selection by criteria which were known to have

questionable predictive validity, might lead to litigation by

members of excluded groups.16

The procedure employed—comparing minority appli

cants with each other, and picking the most promising from

that group—avoided the perceived discriminatory effect of

comparing minority students with majority ones on the

basis of PFYA. The procedure was not designed to achieve

an over-all ranking that would absolutely correspond to

promise as a student and as a lawyer, since it is doubtful

that the data at hand permitted a pre-law school compari

son of the ultimate professional promise of the applicants,

whether minority or majority. Rather, it sought to ensure

that no applicants were accepted of whom respondents did

not expect satisfactory achievement.

16 As the Fifth Circuit has cogently said, “ In the problem of

racial discrimination, statistics often tell much, and Courts listen.”

Alabama v. United States, 304 F.2d 583, 586, aff’d, 371 IT.S. 37

(1962). See also, Turner v. Fouche, 396 IJ.S. 346 (1970).

16 De Funis and his amici urge that the Law School should not

have done anything about the effects of past discrimination because

neither the "University nor the Law School had any responsibility

for it. This is an unacceptably insular way of viewing a particu

larized result of the national problem of racism.

This case involves a national law school, with a policy of admit

ting a substantial number of students from out of state. Even if

the State and the institution themselves were totally free of any

taint of racial discrimination, the admission of some students

under criteria that operate to exclude others who were victims of

racial discrimination in other parts of the country could raise

serious equal protection questions. See, Oregon v. Mitchell, 400

U.S. 112, 133-34 (1970) (Black, J.) (the effects of racial discrimi

nation, wherever it occurred, present a national problem that can

be responded to even with regard to states without a history of

discrimination).

8

One reason for the differential treatment of minority

applicants was, of course, to make it possible for a signifi

cant number to be admitted to Law School. And, just as

the basis for realizing that there was something wrong

with rigid selection procedures was the low number of

minority admissions, so the basis for weighing the effec

tiveness of the new method was whether the number ad

mitted reasonably reflected the number of minority persons

in the community at large. Thus, a goal was aimed for, but

there was no quota. The distinction between the two is

clear; a quota is a fixed number or set ratio that must be

filled and, generally, may not be exceeded. A goal is a

target to be used as a yardstick for judging the efficacy of

a program in achieving true equality. See, e.g., Swann v.

Charlotte-MecMenburg Board of Ed., 402 U.S. 1, 25-26

(1971).

There was no quota, and at no time were minority ap

plicants accepted who did not meet the same standard im

posed on all applicants, minority and non-minority alike,

vis., the expectation of satisfactory achievement in law

school and the profession. Indeed, the Law School could

not, for the purpose of filling a quota, have deliberately

chosen a minority student with less over-all promise than

De Funis even if it had wanted to, because the data avail

able was not sufficiently precise to allow such judgments.

Thus, it simply cannot be determined, and certainly not

from this record, that De Funis was kept out of law school

because of his race in the sense that unqualified minority

applicants were admitted on the basis of their race.” 17

17 The admission of unqualified minority students in order to

obtain a fixed number, not the situation presented here, would

indeed be of. questionable constitutionality if it resulted in the

exclusion of other qualified applicants.

9

Another aspect of the admissions policies of the Law

School was its judgment that one factor in determining

the qualities relevant to the contribution an applicant

might make to the profession and the community, is whether

there is a lack of lawyers serving the needs of minorities

of which the applicant is a member. Certainly, a law

school, in assessing its obligation to serve the needs of

society, may decide that it will not use selection criteria

that prevent minority groups from obtaining legal repre

sentation essential to the vindication of constitutional

rights.18

In summary, the University of Washington acted con

sistently with its Fourteenth Amendment duty to ensure

that black, Cbicano, and American Indian applicants were

not in fact denied equal access to lawT school because of

factors relating directly to their race.19 If the equal pro

tection clause is ever to have practical meaning, it cannot

be interpreted to prohibit such a program fo r : “ To use the

Fourteenth Amendment as a sword against such State

power would stultify that Amendment.” Railway Mail

Assoc, v. Corsi, 326 U.S. 88, 98 (1945) (Frankfurter, J.,

concurring).

18 See, NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963); Sanders v. Bus

sell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968) ; Sobol v. Perez, 289 F.Supp.

392 (E.D. La. 1968).

19 An analogy can be drawn to the recognized power of Congress

to adopt broad remedial legislation it feels necessary to ensure the

effective enforcement of Fourteenth Amendment rights. See,

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) ; cf., Welsh v. United

States, 398 U.S. 333, 371 (1970) (White, J., dissenting).

10

II.

The Minority Admissions Program Does Not Violate

Title VI.

Finally, a comment should be made concerning the al

ternative ground advanced by De Funis, that § 601 of the

Civil Eights Act of 196420 invalidates the method by which

the Law School selected applicants.21 We urge, to the con

trary, that Title VI, in conjunction with the implementing

regulations issued and interpreted by the Department of

Health, Education, and Welfare, supports the School’s

actions. Eecently, this Court upheld the power of HEW

to issue appropriate regulations pursuant to § 601 in

exercising its authority to dispense funds in aid of educa

tion. Lau v. Nicholas,------TT.S.------- , 42 U.S.L. Week 4165

(Jan. 21, 1974).22 23

The relevant regulations, found in 45 C.F.E. 80.3 (1973),

are set out in the margin.28 As noted in Lau, 80.3(b) (2)

20 42 U.S.C. § 2000(d).

21 Respondents have urged that this issue is not properly before

the Court. However, in the event it is determined that the question

has been properly raised, amicus wishes to bring to the Court’s

attention information pertinent to its consideration.

22 Lau adhered to the general rule that deference would be given

to the judgment of an administrative agency, as reflected in its

regulations and their interpretation, as to the interpretation of a

statute it is charged with enforcing. See, Trafficante v. Metropoli

tan Life Ins. Co.] 409 U.S. 205, 210 (1973).

23 80.3(b) (2) A recipient, in determining the types of services

financial aid, or other benefits, or facilities which will be pro

vided under any such program, or the class of individuals to

whom, or the situations in which, such services, financial aid,

other benefits, or facilities will be provided under any such

program, or the class of individuals to be afforded an oppor

tunity to participate in any such program, may not, directly

or through contractual Or other arrangements, utilize criteria

or methods of administration which have the effect of subject-

11

prohibits the use of criteria or other methods of adminis

tration that have the effect of cutting persons off from

programs because of their race. (42 U.S.L. Week at 4167.)

More explicitly, 80.3(b) (6) (ii) allows a recipient that has

not been guilty of deliberate discrimination to take af

firmative action “to overcome the effect of conditions” that

have limited participation by racial minorities.

This is precisely what the University of Washington

Law School has done. Well aware of the small number of

minority students, and with substantial reason to believe

that this resulted because standardized criteria—doubtful

predictors of success as students or lawyers—screened

them out, the school took appropriate “action to overcome

[these] effects.”

The Department has construed Title VI, and the regula

tions, to permit precisely the kind of action taken by

respondents. Thus, it approves of the use of differential

and “non traditional” criteria for the admission of minority

students, it recognizes the effect of generalized discrimina

ing individuals to discrimination because of their race, color,

or national origin, or have the effect of defeating or substan

tially impairing accomplishment of the objectives of the pro

gram as respect individuals of a particular race, color or

national origin.

* # * * *

(b) (6) (i) In administering programs regarding which the

recipient has previously discriminated against persons on the

ground of race, color or national origin the recipient must

take affirmative action to overcome the effects of prior dis

crimination.

(ii) Even in the absence of such prior discrimination, a

recipient may take affirmative action to overcome the effects

of conditions which resulted in limiting participation by per

sons of a particular race, color or national origin.

12

tion against minorities as justification, and distinguishes

between “goals” and “quotas.” 24 *

CONCLUSION

The Legal Defense Fund urges that the foregoing anal

ysis of the actual constitutional issue presented in this

case requires that the decision of the Supreme Court of

Washington be affirmed. Counsel for amicus would be

remiss in their duty as officers of the Court, however, if

they did not make known their belief that the proper

disposition of this case may be to dismiss the writ as im-

providently granted, since it is an inappropriate one for

broad constitutional pronouncements concerning the valid

ity of attempts to secure adequate minority representation.

First, a decision by this Court one way or the other will

in no way affect the rights of any of the petitioners, since

Marco De Funis, Jr., will complete law school in June,

1974, regardless. Thus, the case is already effectively

moot.26 Second, it would be far more appropriate to ad

dress questions such as the validity of quotas, the admis

sion of unqualified minority students in preference to quali

fied whites, and the exclusion of a white applicant because

of the acceptance of minority ones, in a case that actually

presented those issues, as this one does not.26 Any decision

24 These interpretations are found in letters by or on behalf of

the Director of the Office of Civil Eights of HEW, written in

response to inquiries. A representative letter is set out in an

appendix to this Brief, and we have deposited copies of other

representative letters in the office of the Clerk.

26 The action was not brought on behalf of any class, and no

general relief, such as enjoining the future use of the challenged

procedures, was either sought or granted.

26 It would also be appropriate to wait for a case which properly

raised in a fully-developed form the question of the applicability

of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the implementing

regulations to these issues.

13

as to those questions here would be premature, because

the present record simply says little or nothing about

unforeseeable implications of new doctrine.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

J am es M . N abrit , I I I

C harles S te p h e n R alston

J eeery A. M in tz

J o h n n y J . B utler

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

Louis H . P ollak

J o h n B aker

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

D epartm e n t of H ea l t h , E du cation , and W elfare

September 25, 1972

Honorable Donald C. Brotzman

House of Representatives

Washington, D.C. 20515

Dear Mr. Brotzman:

Thank you for your inquiry of August 16 on behalf of Mr.

Kenneth Co veil of Boulder, Colorado.

Mr. Covell is concerned about students he knows of with

good grades and good examination scores who were not

accepted to the University of Colorado’s law and medical

schools. Mr. Co veil feels that the University rejected these

students because the Department of Health, Education, and

Welfare requires institutions of higher education receiv

ing Federal funds to have a proportional representation of

minority students in its enrollment.

As you know, the Office for Civil Rights administers Title

VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which requires that

recipients of Federal financial assistance offer their bene

fits and services without regard to race, color, or national

origin. Under Title VI institutions of higher education must

recruit, admit and make all course offerings and college-

supported activities available to students in a nondiscrimi-

natory manner. However, no quota of minority students

is required to comply with this law. The University of

Colorado participates in various Federal financial assis

tance programs, and, therefore, is subject to the require

ments of Title VI. In fall 1970 the University reported to

la

2a

Appendix

us that minority enrollment in its medical school was 3.2

percent. This is the latest data available to us at this time.

While the University did not file a separate report for its

law school, we are confident that minority enrollment in

this school is of the same order of magnitude as that of

the medical school.

This Office is aware that several institutions of higher edu

cation receiving Federal financial assistance have estab

lished programs to increase the number of minority group

students they enroll. Such programs may include special

efforts to recruit minority applicants, financial assistance

and evaluation of applicants’ potential through the use of

non-traditional criteria. Quite often institution officials

state a goal for a specified level of minority enrollment.

In those cases that have come to our attention, goals differ

from quotas in two main major respects. First, it is the

objective of the goals to increase the participation of

groups which have not been enrolled in significant numbers

in the past. Second, the goals do not constitute a ceiling,

i.e., no more than a specified number will be admitted.

Clearly the intent of goals is the opposite of that of quotas,

to include rather than limit.

In general the programs described above are consistent

with the requirements of Title VI. Numerous court deci

sions have held that differential treatment on the basis of

race is not a violation of the Constitution where its intent

is to overcome the effects of past discrimination. Negroes,

Spanish-surnamed Americans, and American Indians, as

groups, have been subjected to various kinds of discrimina

tion which have resulted in substantially diminished op

portunities for them to derive the benefits of a higher ed

ucation. It should be noted, however, that preferential ar-

3a

Appendix

rangements for minority students cannot be established on

a permanent basis. At some point, the appearance of

minority group members in an institution’s enrollment

would be such as to require abandonment or suitable modifi

cation of the special programs.

We appreciate your personal interest in this matter. If

the Department can be of further assistance, please let me

know.

Sincerely yours,

(Sgd.) Patricia A. King

J. Stanley Pottinger

Director, Office for Civil Bights

ME1LEN PRESS !NC. — N. Y. C. «sggl^> 219