Reno v. Bossier Parish School Board Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

August 31, 1996

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Reno v. Bossier Parish School Board Brief for Appellant, 1996. 053f3901-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a3a440ab-7b50-472f-846d-ec8d71ef560f/reno-v-bossier-parish-school-board-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

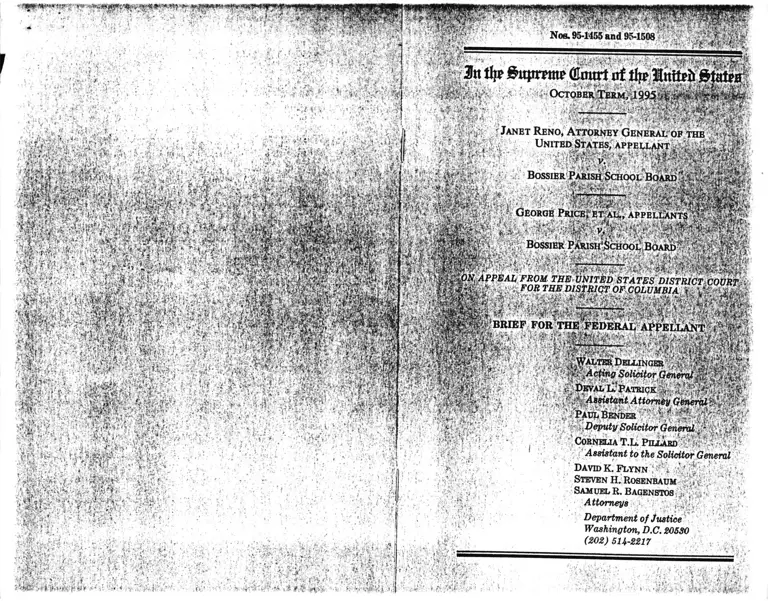

Nos. 95-1455 and 95-1508

Y ■;' ' ■.' ’• ^

Janet Reno, Attorney General i

. United States, appellant ;

-' . . _ . :"; • *, ■•’ i ', ;•: : '' * vj®I&0 i Bossier Parish School Bqari

: . :;. $ ■ ■*,. • • . ■.■? ■' -

V George Price, et.au, appel| uS

■ ■ -

Bossier Parish'&chool,Board :

«^w-3Pli6i»/7“.«v?>r5#

H i i

f S g p p i

■

1; THE iFEDBRAL A PPELLANTf

^ A ^ n g S o lM to r G e r i^ M i

| Dbvad l ; Patrick^ ,^ ^ bvalL/Patock:*,

.;:s< Assistant Attorney General -

Paul Bender ̂ A ; ;

v i.Deputy Solicitor General ■ 1 .. S$f ■'

Cornelia T.L. Pillard • ' •>;•

Assistant to the Solicitor General

David K. Flynn > '’•* ■ 0 ? i- ' .■;

Steven H. Rosenbaum ‘ »

Samuelr. Bagenstos , .

Attorneys \

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 205S0

(202) 511-2217

m t b

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether a district court assessing a covered juris

diction’s purpose under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965, 42 U.S.C. 1973c, may disregard factors this

Court has held are relevant to proof of discriminatory

purpose, on the ground that such evidence is also rele

vant to show vote dilution under Section 2, 42 U.S.C.

1973.

2. Whether the district court clearly erred in finding

no discriminatory purpose.

3. Whether a voting change that clearly violates Sec

tion 2 of the Voting Rights Act is entitled to preclear

ance under Section 5 of the Act. (i)

( i )

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinion below...................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction...........................................-.............................. 1

Statutory provisions involved .......................................... 1

Statement.............................................................................. 2

Summary of argum ent........................................................... 14

Argument:

I. The district court erred in concluding that the

Bossier Parish School Board adopted the Police

Jury redistricting plan without any discrimina

tory purpose ................................................................ 16

A. The district court committed legal error by

categorically refusing to consider the dilutive

effect of the Board’s decision and the Board’s

history of discrimination..................................... 16

B. Other record evidence, together with the evi

dence the district court erroneously failed to

consider, demonstrates that the Board acted

with a discriminatory purpose in adopting

the Police Jury p la n ......................................... 24

C. The district court erred in finding that the

Board had any legitimate, nondiscriminatory

reason for adopting the Police Jury plan....... 29

II. A plan that dilutes minority voting strength in

violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

is not entitled to preclearance under Section 5

of the Act ................................................................ 33

Conclusion ........................................................................... 44

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner, 387 U.S. 136

(1967) ....................................................................... 35

Allen V. State Bd. of Elections, 393 U.S. 544

(1969) ...................................................................... 35

Page

(m )

IV

Cases—Continued: Page

Arizona V. Reno, 887 F. Supp. 318 (D.P.C. 1995),

appeal dismissed, 116 S. Ct. 1037 (1996).............. 21

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976) 15, 33, 35-36,

38, 42, 43

Bob Jones Univ. V. United States, 461 U.S. 574

(1 9 8 3 )............................................. 41

Brown V. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) __ 5

Busbee V. Smith, 549 F. Supp. 494 (D.D.C. 1982),

aff’d, 459 U.S. 1166 (1983) ........................... 17,22,26,28

City of Lockhart V. United States, 460 U.S. 125

(1983)....................................................................... 33,39

City of Mobile V. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) ....... 17,18,

21,37

City of Pleasant Grove V. United States:

479 U.S. 462 (1987) ................................. 23,30-31,42

568 F. Supp. 1455 (D.D.C. 1983), aff’d, 479

U.S. 462 (1987) ............................................. 17

City of Port Arthur v. United States:

459 U.S. 159 (1982) ........................................... 23

517 F. Supp. 987 (D.D.C. 1981), aff’d, 459 U.S.

159 (1982) ...................................................... 17,19

City of Richmond V. United States, 422 U.S. 358

(1975)....................................................................... 16, 23

Columbus Bd. of Educ. V. Penick, 443 U.S. 449

(1979) ...................................................................... 18,19

EEOC V. Ethan Allen, Inc., 44 F.3d 116 (2d Cir.

1994)......................................................................... 32

Eccles V. Peoples Bank, 333 U.S. 426 (1948).......... 35

Garza V. County of Los Angeles, 918 F.2d 763 (9th

Cir. 1990), cert, denied, 498 U.S. 1028 (1991).... 26, 28

Johnson V. De Grandy, 114 S. Ct. 2647 (1994)....40-41, 43,

44

Ketchum V. Byrne, 740 F.2d 1398 (7th Cir. 1984),

cert, denied, 471 U.S. 1135 (1985)....... .............. .. 26

Lemon V. Bossier Parish School Bd., 240 F. Supp.

709 (W.D. La. 1965), aff’d, 370 F.2d 847 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied, 388 U.S. 911 (1967) ............ 5

V

Litton Fin. Printing Div. V. NLRB, 501 U.S. 190

(1991) ....................................................................... 41,42

Louisiana V. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965).... 5

Major V. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. La. 1983).. 5

Miller v. Johnson, 115 S. Ct. 2475 (1995).....21, 22, 33, 44

Morse V. Republican Party of Virginia, 116 S. Ct.

1186 (1996) ...................................................35,38,39,44

Morton Salt Co. V. G.S. Suppiger Co., 314 U.S.

488 (1942)................................................................ 35

NAACP v. Hampton County Election Comm’n,

470 U.S. 166 (1985) ............................................... 42

Neiv York V. United States, 874 F. Supp. 394

(D.D.C. 1994) ......................................................... 21

Personnel Administrator V. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256

(1979) ....................................................................... 18

Presley V. Etowah County Comm’n, 502 U.S. 491

(1992) ..................................................................... 42

Public Serv. Comm’n V. Wycoff Co., 344 U.S. 237

(1952) ....................................................................... 35

Pullman-Standard V. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982).... 18, 24,

32

Rogers V. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982)......... 16,17,18,19,

20, 21, 41

Rybicki V. State Bd. of Elections, 574 F. Supp. 1082

(N.D. 111. 1982)....................................................... 26

Shaw V. Hunt, No. 94-923 (June 13, 1996) ............. 22

Shaw V. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) ......................... 32

South Carolina V. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966).. 34

Southwest Merchandising Corp. V. NLRB, 53 F.3d

1334 (D.C. Cir. 1995) ............................................ 32

St. Mary’s Honor Center V. Hicks, 509 U.S. 502 .

(1993) ...................................................................... 32

Texas v. United States, Civ. Act. No. 94-1529

(D.D.C. July 10, 1995) ......................................... 23

Thornburg V. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986)..........29, 37, 38

United States V. Board of Comm’rs, 435 U.S. 110

(1978) ...................................................................39,41,42

United States v. Virginia, No. 94-1941 (June 26,

1996)

Cases—Continued: Page

31

Cases—Continued:

VI

Page

Village of Arlington Heights V. Metropolitan Hous

ing Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977)-----14,16,17, 18,

20, 21, 24, 27

Washington V. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976)............ 16,18

White V. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) ................. 36

Wilton v. Seven Falls Co., 115 S. Ct. 2137 (1995).. 35

Zimmer V. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973), aff’d sub nom. East Carroll Parish School

Bd. V. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1975) ................. 40

Constitution, statutes and regulations:

U.S. Const. Amend. X I I I ........................................... 5

Declaratory Judgment Act, 28 U.S.C. 2201 ........... 34-35

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982, Pub. L.

No. 97-205, § 2(b) (4), 96 Stat. 133 (1982) ....... 37

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. 1973 et seq.:

§ 2, 42 U.S.C. 1973............................................... passim

§2 (a), 42 U.S.C. 1973(a).................................. 2,37

§ 2 (b ) ,42U.S.C. 1973(b) .................................. 2,37

§ 5, 42 U.S.C. 1973c.............................................passim

28 C.F.R.:

Section 51.52(a).................................................. 34

Section 51.55(b) ( 2 ) ........................ 2,13,15-16, 33, 40

Miscellaneous:

50 Fed. Reg. (1985):

p. 19,122............................................................... 39

p. 19,131............................................................... 39

52 Fed. Reg. 487 (1987) ................. 40,41

II.R. Rep. No. 227, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981).... 38

Proposed Changes to Regulations Governing Sec-

tion 5 of the Voting Rights Act: Oversight Hear

ings Before the Subcomm. mi Civil and Constitu

tional Rights of the House Comm, on the Judici

ary, 99th Cong., 1st Sess. (1985)........................ 40,41

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982).......33, 38, 40

Subcomm. on Civil and Constitutional Rights of the

House Comm, on the Judiciary, 99th Cong., 2d

Sess., Ser. No. 9, Voting Rights Act: Proposed

Section 5 Regulations (Comm. Print 1986) ....... 41

H it l l j e ( E iu t r l o f % I t t i t e b S t a t e s

October Term, 1995

Nos. 95-1455 and 95-1508

Janet Reno, Attorney General of the

United States, appellant

v.

Bossier Parish School Board

George Price, et al., appellants

v.

Bossier Parish School Board

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

BRIEF FOR THE FEDERAL APPELLANT

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the three-judge district court (J.S. App.

la-65a) is reported at 907 F. Supp. 434 (D.D.C. 1995).

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the three-judge district court was

entered on November 2, 1995. A notice of appeal was

filed on December 27, 1995. J.S. App. 163a-164a. The

Court noted probable jurisdiction on June 3, 1996. The

jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

1253 and 42 U.S.C. 1973c.

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The relevant statutory provisions are Sections 2 and 5

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. 1973, 1973c.

J.S. App. 165a-167a. This case also involves a provision

( 1)

2

of the Procedures for the Administration of Section 5, 28

C.F.R. 51 .55(b)(2). J.S. App. 168a.

STATEMENT

1. Congress enacted the Voting Rights Act of 1965

to eliminate racial discrimination in voting. Section 5 of

the Act, 42 U.S.C. 1973c, provides that a covered juris

diction may not implement any change affecting voting

unless it first obtains judicial or administrative preclear

ance. A covered jurisdiction may obtain judicial pre

clearance of a voting change by establishing in a declara

tory judgment action in the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia that the change “does not

have the purpose and will not have the effect of denying

or abridging the right to vote on account of race or color.”

42 U.S.C. 1973c. Alternatively, a covered jurisdiction

may submit the voting change to the Attorney General

for administrative preclearance. The change may be en

forced if, within 60 days after its submission to her, the

Attorney General has interposed no objection to it. There

is no dispute that the Bossier Parish School Board re

districting plan involved in this case is a change in an

election practice by a jurisdiction that is covered by the

requirements of Section 5. See J.S. App. 140a-141a

(1)11 249, 251).

Section 2 of the Act, as amended in 1982, 42 U.S.C.

1973, prohibits any voting practice “which results in a

denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the

United States to vote on account of race or color.” 42

U.S.C. 1973(a). A voting practice violates Section 2

if it has the discriminatory effect of denying minority

citizens an equal opportunity to participate in the elec

toral process and to elect representatives of their choice.

42 U.S.C. 1973(b).

2. a. This appeal arises from a declaratory judgment

action by the Bossier Parish School Board (Board) for

preclearance of a redistricting plan. The 12-member

3

Board governs the Bossier Parish School District, which is

coterminous with the parish. J.S. App. 3a-4a. The Board

is elected from single-member districts for four-year, con

current terms. A majority-vote requirement applies to

elections of Board members. Id. at 4a. The Board re

districted following the 1990 census in order to eliminate

population malapportionment among its districts.

In 1990, black persons comprised 20.1 % of the total

population of Bossier Parish, and 17.6% of the voting

age population. J.S. App. 2a. As of 1994, blacks com

prised 15.5% of Bossier Parish’s registered voters. Ibid.

The black population of the parish is concentrated in two

areas: More than 50% of the black residents live in

Bossier City, id. at 68a ( f 10), and the remaining black

population is concentrated in four populated areas in the

northern rural portion of the parish, id. at 2a, 68 a

(1j 10).1 The parties have stipulated that it is feasible

to draw two reasonably compact black-majority districts

in Bossier Parish using traditional redistricting features

such as roads, streams, railroads, and corporate bound

aries: one in Bossier City, id. at 76a (H 36), and one

in the northern rural area of the parish, id. at 114a

(H 148); see id. at 113a-l 15a (Ufl 143-150).

The parties also have stipulated to facts showing that

voting in the parish is racially polarized, J.S. App. 40a,

122a-127a (1111181-196); see also J.A. 113-121 (Eng-

strom declaration), and that “voting patterns in Bossier

Parish are affected by racial preferences,” J.S. App. 122a

(1| 181). At the time the Board voted to adopt the re

districting plan at issue in this case, black candidates had

1 The northern rural portion of the parish is sparsely populated

in comparison with the rest of the parish, with more densely popu

lated communities separated by large, lightly settled areas. In

the School Board redistricting plan at issue in this case, that

portion of the parish is encompassed in a single, 33.5-mile-long,

424-square-mile district. The district encompasses almost half of

the area of Bossier Parish. J.S. App. 114a-115a (|f 149) ; id. at

112a (!) 140).

4

run for election to the Board on at least four occasions,

but none had ever been elected. Id. at 4a, 115a (51 153);

see also J.A. 54-60. Black voters historically have also

been unable to elect candidates of their choice to other

political positions in Bossier Parish. J.S. App. 118a-172a

(5151 153-196). Of the 14 elections in the parish since

1980 in which a black candidate has run against a white

candidate in a single-member district or for mayor, only

two black candidates have won. Id. at 127a (51 196); see

also J.A. 54-60. One was a candidate for the Bossier

Parish Police Jury,” and the other for the Bossier City

Council. Ibid. The black Police Juror won in Police Jury

District 10, which contained a United States Air Force

base, J.S. App. 117a (5151 160-161), and the black City

Council member won in a city council district that sub

stantially overlapped with Police Jury District 10, and

also included the Air Force base, id. at 120a (5( 172).

The district court found that the Base is a factor unique

to those districts that increased the ability of black voters

in that area to elect representatives of their choice. Id.

at 2a n. 1.8

Bossier Parish and its School Board have a history of

racial discrimination beginning before the Civil War and

continuing to the present. See generally J.S. App. 42a-

2 The Police Jury is the governing body for the parish. See

pages 6-7, infra.

3 Many residents in and around the base do not vote in local

elections, J.S. App. 117a-118a (ffff 160-163) ; that factor, together

with the tendency of Air Force retirees who settle in the area

to vote in a less racially polarized way than other Bossier Parish

residents, increases the ability of black voters in the districts

containing the Air Force base to elect representatives of their

choice. Id. at 117a-118a (ffff 162-163), 127a (ff 196). In the re

configured plans adopted by the Police Jury in 1991 and the City

Council in 1993, the Air Force base no longer has that effect. Id.

at 2a n.l. The black incumbent Police Juror was reelected in 1991

in the redrawn district in an election in which he ran unopposed.

Ibid. The black City Council member ran against a white opponent

in 1993 and lost. Id. at 120a (ff 173).

5

46a, 130a-140a (5151 214-248).* De jure segregation pre

vailed in Louisiana’s schools long after this Court decided

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954). J.S.

App. 136a (5| 235). The Board has repeatedly sought to

evade its desegregation obligations. Id. at 136a-137a

(5151 237-239). It remains under court order to remedy

the vestiges of racial discrimination in its school system.

See Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Bd., 240 F. Supp.

709 ( W.D. La. 1965), aff’d, 370 F.2d 847 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied, 388 U.S. 911 (1967). Notwithstanding the

Board’s affirmative obligation to desegregate, the schools

in Bossier Parish have, since 1980, become increasingly

segregated by race. J.S. App. 137a-138a (5151240-242).

Although black students comprise only 29% of the

Parish’s student population, four of the 27 schools in the

Parish have student bodies that are more than 70%

black. Id. at 138a (51 242).6

In addition to presiding over increasing racial segrega

tion in parish school populations, the Board has violated

the Lemon court’s order by failing to maintain a biracial 4 5 *

4 Many decades of discriminatory government action in Louisiana

resulted in the large-scale disenfranchisement of black voters.

Following the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, Louisiana

enacted laws intended to reduce black voting; black registration

decreased by 90% within a few years. J.S. App. 130a-131a (ffff 215-

219). In 1921, an amendment to the state Constitution required

persons seeking to register to vote to “give a reasonable interpre

tation” of a constitutional provision. Id. at 132a (ff 221). That

clause, which disenfranchised most black citizens, was not invali

dated until 1965. Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965).

After an all-white Louisiana Democratic primary was invalidated,

the party adopted other discriminatory election devices, including

an anti-single-shot law and a majority-vote requirement for party

office. J.S. App. 132a (ff 222); Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325,

341 (E.D. La. 1983).

5 Each of those four predominantly black schools is located

within one of the two areas, Bossier City and the northern rural

portion of the parish, J.S. App. 12a (ff 142), in which a reason

ably compact majority-black district may be drawn, id. at 76a

(ff 36); id. at 114a-115a (ffff 148-150).

6

committee to recommend ways to attain and maintain a

unitary school system. J.S. App. I03a-104a (H 1 |lll-

112). The Board first convened the committee in 1976,

but only the black committee members attended the few

meetings that were held, and the Board promptly disbanded

the committee. Ibid. The Board did not convene another

biracial committee until 1993, shortly after submitting its

redistricting plan to the Justice Department for Section 5

review. Id. at 104a (1| 113). The Board promptly dis

banded that committee because, as School Board Presi

dent Barry Musgrove explained, “the minority members

of the committee quickly turned toward becoming in

volved in policy.” Id. at 105a (1| 116).

The effects of past discrimination in Bossier Parish

continue today: “Black citizens of Bossier Parish suffer a

markedly lower socioeconomic status than their white

counterparts” that is “traceable to a legacy of racial dis

crimination affecting Bossier Parish’s black citizens.” J.S.

App. 128a (1|200); see generally id. at 127a-130a

(UK 197-213). That status “makes it harder for blacks to

obtain necessary electoral information, organize, raise

funds, campaign, register, and turn out to vote, and this

in turn causes a depressed level of political participation

for black persons within Bossier Parish.” Id. at 130a

(1J213). Significantly smaller proportions of black

voting-age citizens than white voting-age citizens have in

fact registered to vote in Bossier Parish. Id. at 127a

(1 197).

b. Following the 1990 census, redistricting efforts by

the Bossier Parish Police Jury preceded the School Board

redistricting. The Police Jury, like the School Board, con

sists of 12 members who are elected from single-member

districts in the same manner as the Board. J.S. App. 2a.

The Police Jury has never had a districting plan that

contained any majority-black districts. Ibid.

During the 1990-1991 redistricting process, the white

Police Jurors and their demographer knew that it was

feasible to effectuate black political participation by adopt

7

ing a non-dilutive redistricting plan. J.S. App. 76a (1) 36),

82a-83a (1153), 114 (1)148). Police Jurors nonethe

less told citizens who advocated creating majority-black

districts that it was impossible to create such districts

because the black population was too dispersed. Id. at

3a, 83a (1| 54); see also id. at 82a (1)52). In April,

1991, the Police Jury adopted a redistricting plan that,

like all of its predecessors, contains no majority-black

districts. Id. at 3a, 68a (H 11).

On May 28, 1991, the Police Jury submitted its redis

tricting plan to the Attorney General seeking preclear

ance under Section 5. The Police Jury did not provide

the Attorney General with information then available to

it showing that reasonably compact majority-black dis

tricts could be created. J.S. App. 68a-69a (H 11), 76a

(H 36), 82a-83a (U 53). Nor did it provide a copy of a

letter from the Concerned Citizens of Bossier Parish, a

local organization, protesting the Police Jury’s exclusion

of black citizens from the redistricting process, id. at

69a (I) 11), despite the organization’s express request

that the letter be included in Jh e Police Jury’s Section

5 submission, id. at 87a (H1| 65, 66). On July 29,

based on what turned out to be inaccurate and incom

plete information, the Attorney General precleared the

Police Jury redistricting plan. Id. at 3a, 68a-69a ( f 11).

c. The School Board began its own redistricting pro

cess in early 1991. J.S. App. 4a. With its next election

not scheduled to occur until October, 1994, the Board

proceeded without urgency. Id. at 4a, 93a (1| 83). The

Board initially chose not to use the districts in the 1991

Police Jury plan, but to develop a different plan. Id.

at 4a, 28a, 47a, 94a ('ll 87). Although the Board and

the Police Jury have jurisdiction over the same geo

graphic area and both use 12 single-member districts, the

bodies serve different functions and for at least a decade

have maintained different electoral districts. Id. at 3a-4a

6 n.3, 72a-73a (1|1| 24, 26); U.S. Exh. 94, at 14. School

boards and police juries have different redistricting inter

8

ests that generally warrant different plans: “For example,

police juries are concerned with road maintenance, drain

age, and in some cases garbage collection, and the level

of demand for such services in each district is a concern.

School board members, by contrast, are typically con

cerned with having a public school or schools in each

district.” J.S. App. 73a ( f 24); U.S. Exh. 94, at 14-15.

Police Jury district lines do not correspond with school

attendance zones, and schools are unevenly distributed

in the Police Jury districts, with some districts contain

ing no schools and others containing several. J.S. App.

8a, 112a ( |̂ 141). If used by the Board, the 1991 Police

Jury plan would, in addition, pit two sets of Board in

cumbents against one another and create other districts

with no Board incumbents. Id. at 8a, 102a (̂ j 109).

The Board hired Gary Joiner, the Police Jury’s cartog

rapher, to develop a redistricting plan for the Board,

estimating that he would spend 200 to 250 hours on the

project. J.S. App. 92a (^ 80), 94a (̂ ] 86). The carto

grapher met privately with Board members and showed

them various computer-generated alternative districts. Id.

at 97a ( f 96).

Beginning in March, 1992, representatives of local

black community groups (including defendant-intervenor

George Price, president of the local chapter of the NAACP)

requested that representatives of the black community

be included in the Board’s redistricting process. The

Board did not respond to those requests. J.S. App. 5a,

96a-98a ( ^ j 93-94, 97). In August, 1992, with no other

plan publicly on the table, Price presented a plan for

two majority-black districts that had been developed by

the NAACP. Id. at 6a, 96a-97a (̂ J 95), 98a 98-

99). Price was told that the Board would not consider

a plan that did not also draw the other ten districts. Id.

at 6a, 98a (1| 99).

At the September 3, 1992, Board meeting. Price pre

sented an NAACP plan depicting all 12 districts, but the

Board refused to consider it, ostensibly because “the

plan’s district lines crossed existing precinct lines, and

therefore violated state law.” J.S. App. 99a ( |̂ 102);

id. at 6a.’’ The Board’s cartographer and attorney knew

at the time, however, that the crossing of existing pre

cinct lines did not legally preclude the Board from con

sidering the plan. Id. at 99a-100a ( f 102). Although

state law prohibits school boards from splitting precincts,

id. at 71a-72a ( |̂ 21), school boards were always “free

to request precinct changes from the Police Jury neces

sary to accomplish their redistricting plans [sic: goals],”

id. at 7a (quoting id. at 72a ( |̂ 23 )). That practice is

“quite common” statewide. Id. at 72a ('f 22); J.A. 168

(Joiner testimony); see J.A. 136-138 (Creed testimony);

J.A. 140-141 (Creed supplemental testimony).* 7 The

Bossier Parish School Board itself apparently had antici

pated the necessity of splitting precincts in its redistricting

plan. See J.S. App. 29a, 56a-57a, 95a ('f 89). Joiner

had given the Board precinct maps at the start of the

redistricting process, telling them that they “would have

to work with the Police Jury to alter the precinct lines,”

id. at 95a (i| 89). .

At no time during the redistricting process did the

Board or its cartographer ever assert that there was any

value in avoiding precinct splits or in minimizing their

number. Nor, during the redistricting process, did Board

members or their cartographer ever discuss the alleged

costs of creating precinct splits. See generally U.S. Exhs.

26-28, 32, 34 (Board minutes); J.A. 87-88 (Blunt testi

mony). The Board never requested that the Police Jury

consider realigning the precincts. J.S. App. 7a. The

0 Louisiana election precincts are administrative units established

for the purpose of conducting elections, including siting polling

booths and allocating election officials. See Defendant-Intervenors’

Exh. G at 15.

7 For example, of the nine redistricting plans the Board’s cartog

rapher had drawn for Louisiana parishes, five involved school

boards that sought and received precinct changes from their police

juries in this manner. Tr. vol. I (Apr. 10, 1995), at 157-158 (Joiner

testimony).

9

10

Board also never asked its cartographer to explore the

possibility of modifying the NAACP proposal to reduce

the number of precinct splits, or of otherwise developing

a plan that would alleviate black vote dilution. Id. at

101a (1| 106).

Instead, at the Board's next scheduled meeting, two

weeks after Price presented the NAACP plan and two

years before the next Board election, the Board unani

mously passed a motion of intent to adopt the Police

Jury plan that it had initially found unsatisfactory. J.S.

App. 100a (1i 106). The Board’s action to adopt the

Police Jury plan precipitated overflow citizen attendance

at a Board meeting on September 24, 1992. Id. at 7a-8a,

101a (1| 108). Fifteen residents voiced their opposition

to adoption of the Police Jury plan, principally on the

ground that it would dilute black voting strength. Ibid.

No one spoke in favor of the Police Jury plan. Id. at 8a.

The NAACP presented a petition containing over 500 sig

natures— the largest number of signatures on a petition

opposing a Board action that had been submitted on any

subject in years. Id. at 101a (H 108). The petition asked

the Board to consider alternatives to the Police Jury plan

that would be less dilutive of minority voting strength.

Id. at 7a-8a.

George Price, on behalf of several community organiza

tions representing interests of black residents, urged the

Board to consider the NAACP plan or to use it as a

foundation for creating a different non-dilutive plan. J.S.

App. 6a-8a; 101a (H 108). Price also explained to the

Board that, in light of the NAACP plan, which demon

strated the feasibility of drawing one or more reasonably

compact majority-black districts, the Attorney General’s

preclearance of the Police Jury plan did not guarantee

preclearance of the same plan for School Board elections,

j A. 122, 132. The Board did not respond to the oppo

nents of the Police Jury plan, and adopted that plan at

its next meeting. J.S. App. 8a, 102a (1| 109).

11

Several board members explained, in private conversa

tions, why the Board had refused to consider any ess

dilutive redistricting plan. Board member Henry Bu

stated that although he personally favors having black

representation on the board, other school board member

oppose that idea.” J.A. 93 (Davis testimony); J.S. App.

31a, 53a-54a. Board member Barry Musgrove said that

“the Board was ‘hostile’ toward the idea of a black major

ity district.” J.A. 123 (Price testimony); J.S. App. 53a.

Board member Thomas Myrick explained to Price his own

opposition to a less dilutive redistricting plan Myrick

represented a district that included portions of predomi

nantly black communities, which, if not divided could

comprise part of a black-majority district north of Bossier

City J.S. App. 81a (1 48), 93a-94a (11 85); see also

J.A. 102-103 (Castille declaration); J.S. App. llO a - ll ta

(1111 133-138).8 Myrick told Price that “he had worked

too hard to get [his] seat and that he would not stand by

and ‘let [them] take his seat away from him.’ ” J.A.

124 (Price testimony); see J.A. 135 (Harry testimony);

J S App. 53a. Myrick also told Joiner, the Board’s own

cartographer, that he wanted to avoid creating a black-

majority district. J.A. 163-164 (Joiner testimony).

The Board submitted the Police Jury plan to the Attor

ney General for preclearance. On August 30, 1993, the

Attorney General objected to the plan under Section 5

of the Voting Rights Act, citing information available to

s Myrick, accompanied by at least two Police Jurors who repre

sented districts that similarly divided black communities, had met

frequently with the Police Jury’s cartographer, Gary Joiner during

the Police Jury redistricting process. J.S. App. 81a (([ 48), 93a-94a

(1185). Although Myrick flatly denied at trial having met with

Joiner, J.A. 151, 156-157, Joiner testified that Myrick had come

to his office several times—as many as six to ten—to discuss the

Police Jury redistricting, and to indicate his opposition to drawing

a black majority district, J.A. 159-164. It was Myrick who firs

proposed to the Board that it adopt the Police Jury plan as its owi

J.A. 151-152 (Myrick testimony).

12

the Board, showing the clear discriminatory effect of the

plan on minority voting strength, that had not been pro

vided when the Police Jury submitted the same plan in

1991. J.S. App. 8a, lU6a d | 119), 154a-158a. On De

cember 20, 1993, the Attorney General denied the Board’s

request for reconsideration and withdrawal of the objec

tion. Id. at 159a-162a.

3. On July 8, 1994, the Board filed a declaratory

judgment action seeking Section 5 preclearance from a

three-judge district court for the District of Columbia.

One judge of the panel presided over a two-day trial that

was held on April 10 and 11, 1995. The record, consist

ing primarily of stipulated facts, written direct testimony

prepared before trial, and the transcript of live cross and

rediiect examinations, was provided to the other judges

and closing argument was conducted before the entire

panel. J.S. App. 9a. On November 2, 1995, the district

court granted preclearance. Id. at 36a.

The district court first held that Section 5 preclearance

cannot be denied based upon a violation of Section 2.

J.S. App. 11 a-12a. The court reasoned that Section 2

uses plainly different language and serves a different func

tion from that of section 5.” Id. at 15a. The court held

that the discriminatory effects addressed by Section 5 are

limited to retrogressive effects, whereas Section 2’s “re

sults standard can be violated * * * irrespective of

whether the disputed voting practice is better or worse

than whatever it is meant to replace.” Ibid. The court did

not address the United States’ alternative argument that a

Section 2 violation, even if not a form of prohibited

“effect” under Section 5, nevertheless constitutes an equi

table defense against Section 5 preclearance, on which the

United States bears the burden of proof. See U S Post-

Trial Br. 32 n.27.

The district couit concluded that the legislative history

of the Act did not support denial of preclearance based

on a Section 2 violation. In its view, resort to the leais-

13

lative history was inappropriate because the language of

the statute is “unambiguous.” J.S. App. 17a. The court

also refused to accord any deference to the Department

of Justice regulation requiring the Attorney General to

withhold preclearance of voting changes that clearly vio

late Section 2, 28 C.F.R. 51 .55(b )(2 ), on the ground

that a federal court has authority co-equal with that of

the Attorney General to interpret Section 5 in the first

instance. J.S. App. 18a-19a. In light of its legal ruling,

the court declined to decide whether the evidence estab

lished that the redistricting plan was dilutive in violation

of Section 2. Id. at 9a n.6.

The district court then held that the Board had met its

burden of showing that, in adopting the Police Jury plan,

it did not act with a racially discriminatory purpose. J.S.

App. 27a-29a. In deciding that question, the court held

that “evidence of a section 2 violation” may not be con

sidered as “evidence of discriminatory purpose under sec

tion 5.” Id. at 23a; see also id. at 24a, 9a n.6. The court

thus refused to consider, as relevant to the Board’s pur

pose, evidence of the Board’s contemporaneous awareness

that the Police Jury plan was dilutive and therefore had the

discriminatory effect of precluding any meaningful oppor

tunity for black citizens to elect representatives of their

choice. Id. at 9a n.6. The district court also refused to

consider evidence that the Board had a long history of

racial discrimination, including continuing noncompliance

with a court order in the three-decade-old Lemon school

desegregation case in which it is a defendant. Id. at 34a

n. 18.

The district court acknowledged that the Board had

“offered several reasons for its adoption of the Police

Jury plan that clearly were not real reasons.” J.S. App. 27a

& n.15. It nonetheless found “legitimate, nondiscrimina-

tory motives” for the Board’s adoption of the Police Jury

plan: “The Police Jury plan offered the twin attractions

of guaranteed preclearance and easy implementation (be

14

cause no precinct lines would need redrawing).” Id at

27a-28a.

Judge Kessler concurred in part and dissented in part.

J.S. App. 37a-65a. She agreed with the majority that a

Section 2 violation docs not prevent Section 5 preclear

ance, J.S. App. 37a, but dissented Irom the majority’s con

clusion that the Board acted with legitimate, nondiscrim-

inatory motives, id. at 38a-65a. Taking into account

evidence that this Court held in Village of Arlington

Heightv v. Metropolitan Housing Dew Corp., 429 U.S.

252, 266 (1977), is relevant in assessing discriminatory

purpose, Judge Kessler would have found that “the evi

dence demonstrates conclusively that the Bossier School

Board acted with discriminatory purpose.” J.S. App. 39a.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. This Court consistently has held that the discrim

inatory effect of a voting change on racial minorities, and

the history of discrimination by the jurisdiction that

adopted the change, are highly relevant in the assessment

of whether the jurisdiction acted with a discriminatory pur

pose. By prohibiting consideration of such probative evi

dence under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,

42 U.S.C. 1973c, the district court squarely contravened

this Court s established approach to determining discrim

inatory purpose in both voting and non-voting contexts.

Because the application of an erroneously restrictive legal

standard necessarily affected its decision, the district

court’s judgment cannot stand.

When all the relevant evidence is considered, the record

permits only one conclusion: that the Board adopted its

i edistricting plan with a racially discriminatory purpose.

In addition to the clearly dilutive impact of the plan__

which “effectively excludes minority voters from the polit

ical process, J.S. App. 41a— and the Board’s history of

discrimination, several other indicia make the Board’s dis

criminatory purpose clear. After a long, deliberate search

15

for a redistricting plan different from that of the Police

Jury, the Board suddenly rushed to adopt the Police Jury

plan as soon as it became clear that the local African-

American community would oppose any efforts to obtain

preclearance of a dilutive plan. As a result, the School

Board entirely disserved two of its primary traditional

districting concerns: incumbency protection and distribu

tion of schools and attendance areas among districts. The

decision to adopt the Police Jury plan at the time it was

adopted makes sense only if the Board was intent on

drawing a plan without any majority-black districts and

chose the Police Jury plan because it was the only such

plan that the Board thought likely to be precleared.

In this context, “guaranteed preclearance” was not, as

the district court believed (J.S. App. 28a), a nondiscrim

inatory motivation; rather, it was a means of effectuating

the Board’s purposeful discrimination. Although the Board

has asserted other allegedly legitimate justifications, those

reasons constituted nothing more than post hoc rationali

zations. Indeed, the district court found that many of the

Board’s asserted motivations “clearly were not real rea

sons for its actions. Id. at 27a n.15. The district court’s

finding of no discriminatory purpose is clearly erroneous

and must therefore be reversed.

2. The district court also erred in holding that voting

changes that dilute minority voting strength in violation

of Section 2 of the Act are entitled to preclearance under

Section 5. Since Beer v. United States, 425 U.S.' 130

(1976), this Court has recognized that an unlawfully dilu

tive voting change is not entitled to preclearance. When it

amended Section 2 and extended Section 5 in 1982, Con

gress was aware of and endorsed that rule; it therefore

expressed its intent that preclearance should be withheld

from changes that violate amended Section 2’s prohibition

on vote dilution. The same principle is embodied in a

regulation promulgated by the Attorney General in 1987

and drafted with close legislative oversight. 28 C.F.R.

16

51 .55 (b )(2 ). The district court’s ruling that changes

which are known to be illegal under Section 2 must never

theless be precleared creates an anomaly that is plainly

contrary to Congress’s intent.

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN CONCLUDING

THAT THE BOSSIER PARISH SCHOOL BOARD

ADOPTED THE POLICE JURY REDISTRICTING

PLAN WITHOUT ANY DISCRIMINATORY PUR

POSE

A. The District Court Committed Legal Error by

Categorically Refusing to Consider the Dilutive

Effect of the Board’s Decision and the Board’s

History of Discrimination

1. Under Section 5, a voting change adopted with a

discriminatory purpose may not be precleared. See 42

U.S.C. 1973c; City of Richmond v. United States, 422

U.S. 358, 378-379 (1975). “[D]etermining the existence

of a discriminatory purpose ‘demands a sensitive inquiry

into such circumstantial and direct evidence of intent as

may be available.’ ” Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 618

(1982) (quoting Village of Arlington Heights v. Metro

politan Housing Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 266 (1977)).

In Arlington Heights, this Court set forth a nonexhaustive

list of factors relevant to that inquiry. “The impact of the

official action— whether it ‘bears more heavily on one race

than another’— may provide an important starting point.”

Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 266 (citation omitted)

(quoting Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 242

(1976)). Other relevant factors include the “historical

background of the decision”— “particularly if it reveals a

series of official actions taken for invidious purposes,”

429 U.S. at 267; the “specific sequence of events leading

up to the challenged decision,” including any procedural

or substantive departures from normal practices, ibid.-, and

the “legislative or administrative history”— “especially

17

where there are contemporary statements by members of

the decisionmaking body, minutes of its meetings, or re

ports,” id. at 268.

This Court has applied the Arlington Heights standards

in adjudicating claims of unconstitutional, purposeful vote

dilution. See Rogers, 458 U.S. at 618-622; City of Mobile

v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 70 (1980) (plurality opinion).

The Court has also repeatedly affirmed judgments of three-

judge district courts that have applied those standards to

Section 5’s discriminatory purpose analysis. See City of

Pleasant Grove v. United States, 568 F. Supp. 1455,

1458 (D.D.C. 1985), aff’d, 479 U.S. 462 (1987); Busbee

v. Smith, 549 F. Supp. 494, 516-517 (D.D.C. 1982),

affd, 459 U.S. 1166 (1983); City of Port Arthur v. United

States, 517 F. Supp. 987, 1019 (D.D.C. 1981), affd, 459

U.S. 159 (1982).

The district court did not follow the established Arling

ton Heights approach. Instead, it incorrectly limited the

facts it considered probative of discriminatory purpose in

a Section 5 proceeding. The court specifically refused to

consider either the discriminatory effect of the challenged

redistricting plan on minority voters or Bossier Parish’s

history of racial discrimination. Characterizing that evi

dence as “section 2 evidence,” the district court asserted

that it had no bearing on the assessment of purpose in a

Section 5 proceeding.® The court thus ignored important

facts that were highly probative of the Board’s purpose in 9

9 J.S. App. 23a (“Miller[ V. Johnson, 115 S. Ct. 2475 (1995)]

forecloses the permitting of section 2 evidence in a section 5

case.”); id. at 24a (“ [W]e will not permit section 2 evidence to

prove discriminatory purpose under section 5.”) ; id. at 34a n.18

(suggesting that the historical failure of the School Board to com

ply with the terms of the desegregation order entered against it

was irrelevant to the inquiry into its purpose in adopting a re

districting plan with no majority-black districts) ; see also id.

at 9a n.6 (“Because we hold * * * that section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act * * * has no place in this section 5 action, much of

the evidence relevant only to the section 2 inquiry is not dis

cussed in this opinion.”).

18

adopting the redistricting plan for which it sought pre

clearance.

a. The district court erred in refusing to consider evi

dence of the dilutive effect of the Board’s redistricting

plan on minority voting strength. “Necessarily, an in

vidious discriminatory purpose may often be inferred from

the totality of the relevant facts, including the fact, if it

is true, that the [challenged decision] bears more heavily

on one race than another.” Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S.

at 242. In the voting rights context, evidence of the dis

criminatory impact of a decision is often “an important

starling point” for an inquiry into purpose. Bolden, 446

U.S. at 70; see Rogers, 458 U.S. at 623-624. So, too, in

discrimination cases arising in other contexts, this Court

has held that the impact of a challenged practice is an

important element in the assessment of purpose. See, e.g.,

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273, 289 & n.18

(1982) (Title V II); Columbus Bd. of Educ. v. Penick,

443 U.S. 449, 464 ( 1979) (education); Personnel Admin

istrator v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256, 274-275 (1979) (em

ployment); Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 266 (zoning).

“Impact” evidence is probative because, when the adverse

consequences of a challenged action upon an identifiable

group are inevitable or foreseeable, “a strong inference

that the adverse effects were desired can reasonably be

drawn.” Feeney, 442 U.S. at 279 n.25.

The School Board was well aware of the dilutive effect

of the Police Jury plan upon minority voting strength, and

the Board’s adoption of that plan w'ith knowledge of that

effect is strongly probative of the Board’s discriminatory

purpose. As Judge Kessler noted below', the Police Jury

plan “effectively excludes minority voters from the polit

ical process.” J.S. App. 41a. Ample evidence established

that the Board was aware of that dilutive impact. “There

was * * * overwhelming evidence of bloc voting along

racial lines” and, “although there had been black candi

dates, no black had ever been elected” to the Bossier

19

Parish School Board. Rogers, 458 U.S. at 623; J.S. App.

40a, 115a-l27a (1ffl 153-196).10 * The Board admitted

that it was “obvious that a reasonably compact black-

majority district could be drawn within Bossier City,” id.

at 76a (1| 36), and that the NAACP plan Price presented

to the Board demonstrated that a second, reasonably com

pact majority-black district could be drawn using natural

and artificial boundaries traditionally used in redistricting.

Id. at 1 13a- 115a ( ^ | 143-150). Price and many other

citizens told the Board that the proposed redistricting plan

would unnecessarily diminish black voting strength. Id.

at 101a-l02a 108).

“[Rjather than consider either of the alternative pro

posals [that included compact majority-black districts]

brought before it or direct their own cartographer to draft

one,” however, “the School Board adopted a plan ‘which

guaranteed that blacks would remain underrepresented on

the [Board| by comparison to their numerical strength.’ ”

J.S. App. 4 !a (quoting City of Port Arthur, 517 F. Supp.

at 1022). Such “actions having foreseeable and antici

pated disparate impact are relevant evidence to prove the

ultimate fact, forbidden purpose.” Penick, 443 U.S. at

464. The district court erred in refusing to consider, as

relevant to the Board’s purpose, this substantial, largely

stipulated evidence demonstratinc minority vote dilution.

See Rogers, 458 U.S. at 623-627.'

10 Board members knew that no black candidate had ever been

elected to the Board, J.A. 125, 126 (letters from Price to School

Board) ; U.S. Exh. 98, at 28-30 (Board member Hensley testimony

regarding Board receipt of Price letter), and the presence of

racial bloc voting in Bossier Parish was generally recognized

among the community and elected officials, see, e.g., U.S. Exh. 102,

at 8-9 (Board member Blunt testimony); J.S. App. 122a ((1181)

(Police Juror Burford’s understanding that there was substantial

racial bloc voting); U.S. Exh. 31 (recognition in local press);

U.S. Exh. 101, at 4, 8 (former Bossier City Councilman Jeff IJarby

testimony); U.S. Exh. 105, at 11-13 (police juror Jerome Darby

testimony).

20

b. The district court also failed to take into account

other relevant evidence of purpose solely because it would

also be relevant in a Section 2 proceeding. This Court

has held that “[e]vidence of historical discrimination is

relevant to drawing an inference of purposeful discrimina

tion. Rogers, 458 U.S. at 625; accord Arlington

Heights, 429 U.S. at 267. The district court, however,

refused to consider the Board’s substantial and continuing

legacy of discrimination against blacks in its administra

tion of the Bossier Parish school system. J.S. App. 9a

n.6, 34a n.18, 42a n.4; compare id. at 34a n.18 with

id. at 42a-46a, 136a-l38a 236-243).

The Bossier Parish School Board has presided over

increasingly segregated schools in spite of its affirmative,

continuing duty to eliminate racial segregation; that fact

buttresses our contention that the same Board acted with

a discriminatory purpose when it adopted a redistricting

plan that adversely dilutes black voting strength. Rogers,

458 U.S. at 624-625 (referring to lingering school segre

gation as relevant to proof of purposeful discrimination).

Indeed, the Board recently violated a court desegregation

order by disbanding a biracial committee; it did so be

cause “the tone of the committee made up of the mi

nority members * * * quickly turned toward becoming

involved in policy.” J.S. App. 105a ( f 116).11 That ac

tion is probative of the Board’s unresponsiveness to rea

sonable concerns of the black community— another “im

portant element * * * of [the] number of circumstances

a court should consider in determining whether discrimi

natory purpose may be inferred.” Rogers, 458 U.S. at

625 & n.9. The district court erred as a matter of law

by refusing to take into account that highly probative

evidence of the Board’s continuing racial discrimination.

11 As Judge Kessler noted, “ [w]hat exactly the Committee was

supposed to become involved in, if not policy, is unclear ” J S App

46a.

21

2. The district court gave three reasons for categor

ically excluding from consideration any evidence that

would be relevant in a Section 2 case. None is

persuasive.

First, the court suggested that allowing such evidence

in the discriminatory purpose inquiry would impermissibly

allow a denial of preclearance to be based solely on a

Section 2 violation. J.S. App. 23a.12 We contend, not

that evidence of a Section 2 violation necessarily suffices

to prove discriminatory purpose; see Rogers, 458 U.S. at

618; Bolden, 446 U.S. at 70, but that it is relevant to

the purpose inquiry, see Rogers, 458 U.S. at 623-624;

Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 265; see also Arizona v.

Reno, 887 F. Supp. 318, 323-324 (D.D.C. 1995) (evi

dence relevant to Section 2 violation also relevant to Sec

tion 5 purpose inquiry), appeal dismissed, 116 S. Ct. 1037

(1996).13 The district court erred as a matter of law in

ignoring that probative evidence.

Second, the district court suggested that this Court’s

decision in Miller v. Johnson, 115 S. Ct. 2475 (1995),

foreclosed any argument that the Board’s adoption of a

plan that it knew diluted minority voting strength evi

denced its discriminatory purpose. J.S. App. 34a-36a.

That is incorrect. In Miller, 115 S. Ct. at 2492-2493, the

Court considered an ameliorative redistricting plan and

As we explain below, a violation of Section 2 provides an

independent basis for denying preclearance. See Point II, infra.

13 The district court erred in relying on New York v. United

States, 874 F. Supp. 394, 398-400 (D.D.C. 1994), in support of

its holding that evidence of a discriminatory effect that violates

Section 2 “has no place” in a Section 5 case. J.S. App. 9a n.6,

22a-23a. The three-judge court in New York merely held that dis

criminatory purpose may not “always be inferred” from adoption

of a system that has a discriminatory effect or, in the case of a

redistricting plan, a dilutive impact, 874 F. Supp. at 399 (emphasis

added) ; it did not hold, as did the district court below, that evi

dence of a discriminatory effect is irrelevant to the Section 5 pur

pose inquiry. See ibid, (citing Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 266).

22

held that purposeful refusal to subordinate traditional dis

tricting principles in order to “maximizfej” the number of

majority-black districts fails to demonstrate purposeful

discrimination. See also Shaw v. Hunt, No. 94-923

(June 13, 1996), slip op. 11-14 (Shaw II). Here, by

contrast, the Board sought consciously to minimize the

number of majority-black districts. Despite concentra

tions of black population, the Board adopted a plan

that lacks any majority-black district, and that has had the

clearly foreseeable effect of diluting minority voting

strength, and the Board did so in circumstances strongly

suggesting a discriminatory motivation. Such “conscious

minimizing of black voting strength” is clearly relevant

to a finding of discriminatory purpose. Busbee, 549 F.

Supp. at 517 (emphasis added); see id. at 518.14 Neither

Miller nor Shaw II disturbed the well-settled rule that

Arlington Heights provides the appropriate standard for

determining discriminatory purpose under Section 5.

Rather, the Court disagreed in those cases with the At

torney General’s application of that standard to the par

ticular plans submitted for preclearance. The Court’s

holdings cast no doubt on the continued application of

traditional discriminatory purpose analysis in Section 5

cases.

14 The Court in Miller did not refuse to consider evidence of the

effect of the challenged districting plan. In evaluating whether

the plan there was adopted with a discriminatory purpose, the

Court considered the plan’s ameliorative impact. 115 S. Ct. at 2492.

Miller is therefore fully consistent with the substantial precedent

mandating consideration of the effect of a decision as one element

in the totality of circumstances that indicates whether the decision

was purposefully discriminatory. Indeed, throughout its Miller

opinion, the Court cited Arlington Heights with approval. Miller,

115 S. Ct. at 2483, 2487, 2489. And while this Court recently ex

pressed doubt that “a showing of discriminatory effect under § 2,

alone, could support a claim of discriminatory purpose under § 5,”

it did not question the well-established proposition that disparate

effects are relevant to discriminatory purpose. Shaw v. Hunt,

slip op. at 14 n.6 (emphasis added).

23

Finally, the district court suggested that a purpose to

cause retrogression in the electoral position of minority

voters is the only type of discriminatory purpose cogni

zable under Section 5. J.S. App. 23a-24a (quoting Texas

v. United States, Civ. Act. No. 94-1529 (D.D.C. July

10, 1995), slip op. 2-3. Under that approach, a jurisdic

tion that had never had a majority-minority district could

never be found to have a discriminatory purpose in re

fusing to create such a district. This Court has expressly

rejected that proposition. In City of Richmond, the Court

concluded that the voting change under review there did

not have an unlawfully retrogressive effect under Section

5, but it then remanded to the three-judge court for a

determination whether the change had been adopted with

a discriminatory purpose. Explicitly addressing the ques

tion how it could be forbidden by § 5 to have the pur

pose and intent of achieving only what is a perfectly legal

result under that section,” the Court found it “plain” that

a voting change made “for the purpose of discriminating

against Negroes * * * has no legitimacy at all under our

Constitution or under the statute” and “is forbidden by

§ 5, whatever its actual effect may have been." City of

Richmond, 422 U.S. at 378-379 (emphasis added). The

Court reaffirmed that proposition in City of Pleasant

Grove v. United States, 479 U.S. 462 (1987), explaining

that a covered jurisdiction may not “short-circuit a pur

pose inquiry under § 5 by arguing that the intended re

sult was not impermissible,” because not retrogressive,

“under an objective effects inquiry.” Id. at 471 n .ll .

See also City of Port Arthur v. United States, 459 U.S.

159, 168 (1982) (noting that an electoral scheme

adopted for a racially discriminatory purpose would be

invalid even if it fairly reflected the political strength of

a minority community).

Because of its failure to apply the correct legal stand

ard to the Section 5 purpose inquiry, the district court’s

decision must be reversed. In this case, as in Pullman-

24

Standard v. Swint, the district court “failed to consider

relevant evidence” and certainly “might have come to a

different conclusion had it considered that evidence.” 456

U.S. at 292. At a minimum, the district court’s errors

require a remand to permit that court to reevaluate the

question of purpose in light of all of the relevant evidence.

B. Other Record Evidence, Together With the Evidence

the District Court Erroneously Failed to Consider,

Demonstrates That the Board Acted With a Dis

criminatory Purpose in Adopting the Police Jury

Plan

The district court not only failed to consider relevant

evidence, but also evaluated improperly the limited evi

dence it did consider. When all the relevant evidence

is correctly considered, it supports only one conclusion:

the Board acted.with a racially discriminatory purpose

in adopting the Police Jury plan.

1. Both the “specific sequence of events leading up”

to the Board’s decision to adopt the Police Jury plan and

the substantive consequences of that decision demonstrate

that the Board acted with a discriminatory purpose. See

Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 267. The Board initially

proceeded without urgency in its redistricting efforts, act

ing separately from the Police Jury. J.S. App. 4a, 92a

(11 80). The Board did not even begin its redistricting

process until after the Police Jury had completed its own

process. At that point the Board hired the Police Jury’s

redistricting consultant, Gary Joiner, who estimated that

it would take 200 to 250 hours to produce a plan for

the School Board— far more time than would be necessary

simply to adopt the Police Jury plan. Id. at 5a, 29a.

Those initial decisions were consistent with the Board’s

needs, for the next Board election would not occur until

more than three years after the Police Jury adopted its

redistricting plan. Id. at 4a. The Board proceeded with

out haste from May, 1991, until the autumn of 1992.

25

It also best served the Board’s interests to develop a

redistricting plan separate from the Police Jury’s. Al

though the two bodies both cover the same geographic

area, and both consist of 12 members elected from single

member districts, the Board and the Police Jury had main

tained different districts throughout the 1980s. They had

done so because “|s]chool boards and police juries have

different needs and different reasons for redistricting” in

general. J.S. App. 72a (H 24). Moreover, the School

Board and the Police Jury had divergent incumbency

protection concerns {id. at 73a (H 26), 92a (i] 81)), and

the fact that the Board and the Police Jury had main

tained separate districting plans in the previous decade

resulted in a continuing divergence in incumbency inter

ests during the post-1990 round of redistricting. Id at

93a (1j84).

But the Board sharply changed course in September,

1992, after the local NAACP made clear that it would

actively urge the adoption of a districting plan that did

not dilute black voting strength. During the summer of

1992, the NAACP repeatedly requested that it be in

cluded in the redistricting process. J.S. App. 96a-101a

(HH 93, 94, 95, 97, 100, 106, 108); J.A. 125-129. How

ever, when Joiner, the Board’s cartographer, demonstrated

alternative redistricting scenarios to the Board members,

in the late summer of 1992, the NAACP was not

informed. J.S. App. 97a (HU 96, 97). At the September

3, 1992, meeting of the Board, NAACP President George

Price presented the NAACP’s 12-district plan, containing

two districts with black voting-age majorities. Id. at 98a-

99a (UU 98-100). Two weeks later, without directing

Joiner to conduct any further study of Price’s plan, the

Board unanimously passed a motion of intent to adopt

the Police Jury plan, which contained no majority-black

districts. Id. at 100a- 101a (U 106). Despite unanimously

negative public comment at an intervening hearing, the

Board adopted the Police Jury plan on October 1 without

26

a single dissenting vote. Id. at 8a, 101 a- 102a (Ilf 108-

109).

As Judge Kessler concluded, “|t|he common-sense un

derstanding of these events leads to one conclusion: The

Hoard adopted the Police Jury plan—two years before

the next election— in direct response to the presentation

of a plan that created majority-black districts. Faced with

growing frustration of the black community at being ex

cluded from the electoral process, the only way for the

School Board to ensure that no majority-black districts

would be created was to quickly adopt the Police Jury

plan and put the issue to rest.” J.S. App. 49a-50a. That

conclusion is bolstered by the Board’s exclusion of mi

norities from any meaningful part in the redistricting

process, see Busbee, 549 F. Supp. at 518, as well as the

anomalous substantive consequences of importing the Po

lice Jury’s redistricting plan for use in School Board elec

tions. Although the Board had long considered incum

bency protection to be an important redistricting interest,

the plan the Board adopted pitted incumbents against

each other in two districts. J.S. App. 102a ( f 109).15

And while school board members “are typically concerned

with having a public school or schools in each [School

15 0ne incumbent Board member who did not stand to lose from

the adoption of the Police Jury plan was Tom Myrick. J.S. App.

95a (If 91). See page 11 & n.8, supra. The district court found

it "understandable” that Myrick held a "strong desire not to have

his district so changed that his constituency [was] obliterated”

(J.S. App. 32a), but it is clear that Myrick recognized that pre

serving his existing constituency came at the necessary expense

of dividing black voters in northern Bossier Parish among several

districts. For Myrick, protecting his incumbency was thus inex

tricably intertwined with intentionally diluting black voting

strength. See Garza V. County of Los Angeles, 918 F.2d 763, 771

(9th Cir. 1990), cert, denied, 498 U.S. 1028 (1991); id. a t’778-

779 & n .l (Kozinski, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part) ;

Ketchum V. Byrne, 740 F.2d 1398, 1408 (7th Cir 1984) cert’

denied, 471 U.S. 1135 (1985) ; Rybicki v. State Bd. of Elections

574 F. Supp. 1082, 1109 (N.D. 111. 1982) (three-judge court)

27

Board] district,” some districts in the Police Jury plan

did not contain a single school. Id. at 73a (̂ ] 24).

Where, as here, “the factors usually considered important

by the decisionmaker strongly favor a decision contrary

to the one reached,” a powerful inference of discrimina

tion arises. Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 267 & n.17.

2. Board members’ own statements of opposition to

black representation” and “drawing majority-black dis

tricts, J.S. App. 3 la-32a; id. at 53a-54a, also show that

the Board acted with a discriminatory purpose. Two Board

members reported that others on the Board were “hostile”

or “opposed” to the idea of black representation on the

Board, or a majority-black School Board district. J.A.

93, 123; J.S. App. 31a-32a. A third, who represented a

district that included portions of a predominantly black

community that, if not divided, could comprise part of a

black-majority district north of Bossier City, insisted that

“he had worked too hard to get [his] seat and that he

would not stand by and ‘let [them] take his seat away

from him.’ ” J.A. 124, 134; J.S. App. 53a, see page 11,

supra.

The district court erred in its interpretation of those

statements. J.S. App. 31a-32a. When all relevant evi

dence is taken into account, the statements clearly indi

cate, contrary to the district court’s conclusion, a purpose

to prevent “the presence of black persons as members

of the School Board.” Id. at 31a. The district court rea

soned that opposition to “the intentional drawing of

majoi ity-black districts in order to ensure black represen

tation on the Board is “hardly an indication of discrim-

inatory purpose unless section 5 imposes an affirmative

obligation to draw additional fr/c] majority-black dis-

tiicts. Ibid. Although the refusal to draw compact

majority-black districts is not always probative of dis

criminatory intent, in the circumstances of this case the

Board s avowed refusal to do so communicated a clear

message of opposition to black representation. In circum

stances where following traditional districting principles

would lead to the drawing of majority-black districts,

28

purposefully avoiding drawing them is probative of racially

discriminatory purpose. See, e.g., Garza v. County of

Los Angeles, 918 F.2d 763, 770-771 (9th Cir 1990)

cert, denied, 498 U.S. 1028 (1991); Busbee, 549 F.

m Pn a t J? 17' The PoIice Jury Plan P'ainly disserved

me Boards interests in incumbency protection and dis

tribution of schools among districts. In the face of un

questioned evidence of dilution, of the Board’s history

ot discrimination, of the suspect timing of the Board’s

decision to adopt the Police Jury plan, and of the Board’s

shitting justifications, the only plausible explanation for

n ^ 0a^d s Ch° ice of the Police Jufy Plan was that the

Board adopted that plan in order to dilute the effectiveness

of black votes. Where, as here, the Board knew that fail

ure to draw majority-black districts would perpetuate

black vote dilution, its expressed opposition to doing so is

evidence of its racially discriminatory purpose.

The district court concluded that “at least a majority of

the white Board members were responsive to the black

community and were not opposed to black representation

on the School Board.” J.S. App. 30a. In support of that

conclusion, it pointed to only one fact— the Board’s ap

pointment of a black member, Jerome Blunt, to a vacant

School Board post. Ibid. But that appointment was

plamiy a meaningless palliative. As Judge Kessler noted,

Mr. Blunt was appointed to represent a district that was

only 11% black, and his short [six-month] tenure on the

job was a stark reminder of the highly polarized voting

m Bossier Parish.” Id. at 54a n.9. (Blunt lost to a white

challenger. Id. at 100a (K 105)). Moreover, the

circumstances of Blunt’s appointment were themselves

suspicious— the appointment occurred “at the very meet

ing where the Board adopted a motion of intent to adopt

the Police Jury plan.” Id. at 54a n.9. From the circum

stances, it appears that “the School Board appointed a

black to fill a seat they knew he would be unable [to]

hold hoping to quell the political furor over the adoption

of the Police Jury plan.” Ibid. This Court has noted

29

that the ephemeral success of black candidates in such

circumstances does not warrant the drawing of favorable

inferences. See Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S 30 75-76

& n.37 (1986).

C. The District Court Erred in Finding That the

Board Had Any Legitimate, Nondiscriminatory

Reason for Adopting the Police Jury Plan

The district court found that the Police Jury plan

“offered the twin attractions of guaranteed preclearance

and easy implementation (because no precinct lines would

need redrawing),” and that those were legitimate non

discriminatory reasons for adopting that plan. J.S. App.

27a-28a. Those factors were, however, not the Board’s

actual reasons, nor were they nondiscriminatory. The dis

trict court’s conclusion that the Board acted for non

discriminatory reasons was infected by the court’s artifi

cially restricted view of the relevant evidence, and was

in any event, clearly erroneous.

Any interest the Board had in “guaranteed preclear

ance was simply a means of effectuating the Board’s

purposeful dilution of minority voting strength. The

Board showed no concern at all with “guaranteed pre

clearance until the local NAACP made clear that it

would oppose preclearance of any plan that continued to

shut out minority voters. As Judge Kessler noted, “[ijf

guaranteed preclearance was what the Board wanted, it

would have acted soon after the Police Jury Plan was pre

cleared by the Justice Department on July 29, 1991,”

lather than waiting for more than a year to adopt that

plan. J.S. App. 58a.

Moreover, the fact that the Police Jury plan had pre

viously been precleared might have recommended it over

other plans comprised exclusively of white-majority dis

tricts, but fails as a rationale for the Board’s selection of

the Police Jury plan over any less dilutive plan. The

Boaid could not realistically have believed that a plan

30

that ameliorated the existing dilution would be less likely to

receive preclearance than the Police Jury plan. “[GJuar-

anteed preclearance” was a plausible motivation for

adopting the Police Jury plan only if the School Board

was firmly intent on continuing to use a plan with no

majority-black districts and it wanted assurance that it

could do so without drawing an objection from the

Attorney General. In short, “[tjhe Police Jury plan only

became ‘expedient’ when the School Board was publicly

confronted with alternative plans demonstrating that

majority-black districts could be drawn, and demonstrating

that political pressure from the black community was

mounting to achieve such a result.” J.S. App. 49a.1<J

The prospect of easy implementation (because no pre

cinct lines would need redrawing),” J.S. App. 28a, also

was not an actual, nondiscriminatory reason for the

Board’s adoption of the Police Jury plan that it initially

had rejected. The court suggested that “the School Board

entirely reasonably could have, when faced with the

NAACP’s plan, arrived quickly at the conclusion that zero

precinct splits was significantly more desirable than 46 ”

id. at 29a (emphasis added), but did not find that the

Board actually reached such a conclusion. The correct

focus in determining the purpose behind the adoption of

the disputed plan is on the Board’s actual purpose at the

time it adopted that plan. City of Pleasant Grove, 479

U-S. at 470 (rejecting argument “developed after the fact” 16

16 For similar reasons, the district court’s view that the Board’s

adoption of a dilutive plan was “an understandable, if not neces

sarily laudable, retreat from a protracted and highly charged

public battle,” J.S. App. 34a, does not support its conclusion that

such a retreat amounted to a nondiscriminatory reason for adop

tion of the Police Jury plan. The only “public battle” the School

Board faced arose from black citizens’ opposition to the strongly

dilutive effect of any plan with exclusively white-majority dis

tricts, and the Board "retreat[ed]” from it by deliberately excluding

black voters from any meaningful participation in the process.

See id. at 58a n.12.

31

because it was “not the true basis” for decision); cf.

United States v. Virginia, No. 94-1941 (June 26, 1996),

slip op. 18 ( “[A] tenable justification must describe ac

tual state purposes, not rationalizations for actions in fact

differently grounded.” ); id. at 2-3 (opinion of Rehnquist,

C.J., concurring).

The evidence shows that splitting precincts was simply