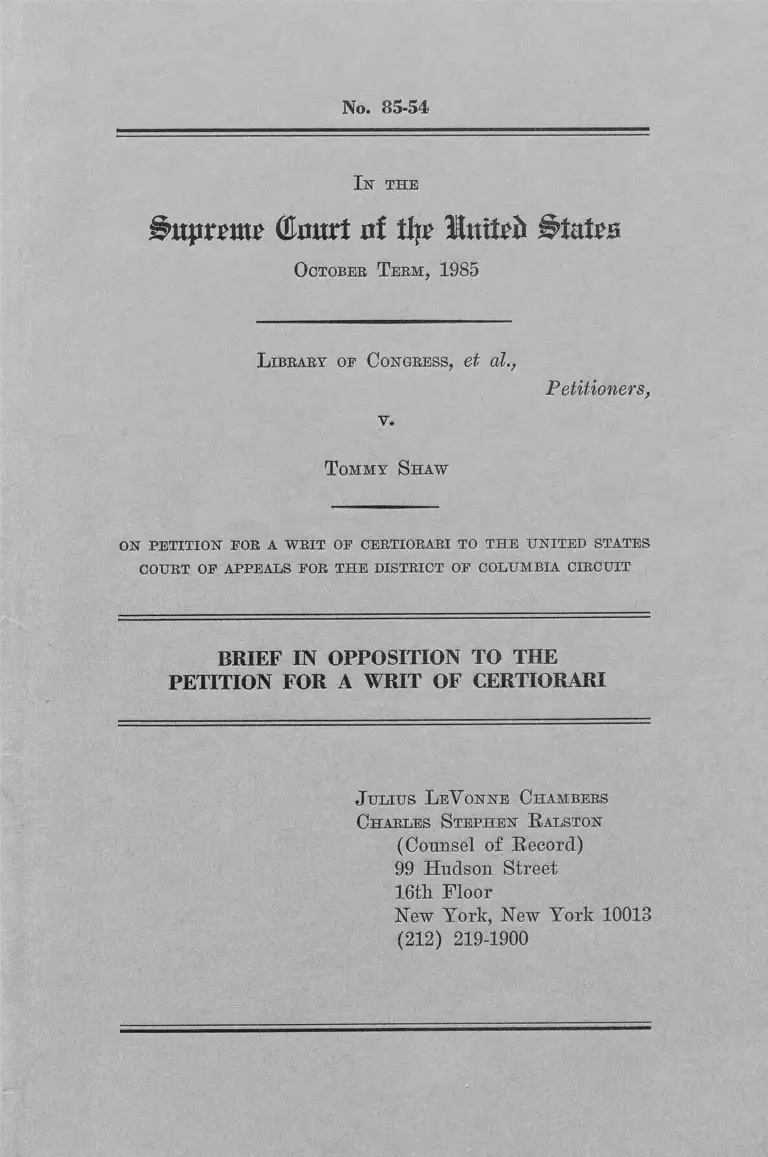

Library of Congress v. Shaw Brief in Opposition to the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Library of Congress v. Shaw Brief in Opposition to the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1985. 18fb0049-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a3b70142-213c-4ab6-9bfd-ed75bba67605/library-of-congress-v-shaw-brief-in-opposition-to-the-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

No. 85-54

I n t h e

&uprrmr (tart of % Inttrft Stairs

O ctober T e r m , 1985

L ib r a r y oe C o ngress , et at.,

v.

T o m m y S h a w

Petitioners,

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO THE

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

J u l iu s L eV o n n e C h a m b e r s

C h a r l e s S t e p h e n R a l st o n

(Counsel of Record)

99 Hudson Street

16th. Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether 717 of the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972, 42 U.S.C.

S 2000e-16, which incorporates 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-5(k), constitutes a complete

waiver of sovereign immunity so that the

relief obtainable, including the amount of

attorneys fees, against a federal agency

in a Title VII action is the same as that

obtainable against all other employers.

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .............. iii

STATUTE INVOLVED ................ . . 1

STATEMENT .......................... 2

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT ...... 6

SUMMARY ...................... 6

DISCUSSION .................. 8

1 . Background ......... 8

2. Section 717 is a

Complete Waiver of

Sovereign Immunity ..... 10

3. The Decision Below

Does Not Conflict

With Prior Decisions

of This Court ......... 14

4. There is No Conflict

Between the Circuits .... 24

CONCLUSION ......................... 25

Page

- ii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Case

Albrecht v. U.S. 329 U.S. 599

( 1947) ............... ......

Boston Sand Co. v. U.S., 278

U.S. 41 ( 1928) . .......

Brown v. General Services Admi

nistration, 425 U.S. 820

( 1976) .... ........ .

Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S.

860 (1976) .................

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico v.

Heckler, 745 F.2d 709 (D.C.

Cir. 1984) .................

Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d

880 (D.C. Cir. 1980) ......

Eastland v. T.V.A., 553 F.2d

364 (5th Cir. 1977) ........

Franks v. Bowman Transporta

tion Co., 424 U.S. 747

( 1976) .......................

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing

Authority, 690 F.2d 601

(7th Cir. 1982) ............ .

Graves v. Barnes, 700 F.2d

220 (5th Cir. 1983) ........

16

20

6,1 1 , 1 2

6,9,11

3

2,7

9

12

7

Page

7

iii

Case Page

Gnotta v . United States, 415

F o 2d 1271 (8th Cir. 1969) ...... 1 1

Institutionalized Juveniles v.

Secretary of Public Welfare,

758 F .2d 897 (3rd Cir. 1985) ... 7

Johnson v. University College

of the University of Alabama,

706 F.2d 1205 (11th Cir.

1983) .......................... 7

Jorstad v. IDS Realty Trust,

643 F .2d 1305 (8th Cir.

1981 ) .......................... 7

Kyles v. Secretary of Agricul

ture, 604 F. Supp. 426

(D.D.C. 1985) ................... 4

National Ass'n of Concerned Vets

v. Sec. of Defense, 675 F.2d

1319 (D.C. Cir. 1982) .......... 3

Parker v. Lewis, 670 F .2d 249

(D.C. Cir. 1982) ............... 3

Ramos v. Lamm, 713 F .2d 546

(1 0th Cir. 1983) ................ 7

Shultz v. Palmer, No. 85-50 ....... 5

Standard Oil Co. v. United

States, 267 U.S. 76 (1925) ..... 22,23

Tillson v. United States, 100

U.S. 43 (1879) ................. 19

iv

Case Page

United States v. Alcea Band

of Tillamooks, 341 U.S. 48

( 1951 ) ...... .................. . 14,15

United States v. Goltra, 312

U.S. 203 ( 1941 ) ................ 17,18

United States v. Louisiana,

446 U.S. 253 ( 1980) ............ 16

United States v. New York

Rayon Importing Co., 329

U.S. 654 ( 1947) ................ 17,18

United States v. North

America Trans. & Tradinq

Co., 253 U.S. 330 ( 1920) ...... 17, 18

United States v. Sherman, 98

U.S. 565 ( 1879) ................ 19

United States v. Thayer-West

Point Hotel Co., 329 U.S.

585 ( 1947) ...................... 17,18

United States v. Worley, 281

U.S. 339 ( 1930) ................ 22,23

United States ex rel Angerica

v. Bayard, 127 U.S. 251

( 1888) .... ..................... 1 5

Williams v. T.V.A., 552 F.2d

691 (6th Cir. 1977) ............ 9

- v -

Page

Statutes:

42 St at,, 1590, ch. 192

(5-15-22) ...................... 20

42 U.S.C. § 20 00e-5(k ) ...........

1,8

,10,18,24

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-15 .............

Legal Pees Equity Act ............

Section 717 of the Equal

Employment Opportunity

Act of 1972 ...................

Section 177, Judicial Code ....... 17

28 U.S.C. § 2516(a) ..... . 17

Other Authorities

"Counsel Fees in Public Interest

Litigation," Report by the

Committee on Legal Assistance,

39 The Record of the Associa

tion of the Bar of the City of

New York 300 ( 1984) ..... . 7

Legislative History of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of

1972, Committee Print, Subcom

mittee on Labor of the Senate

Committee on Labor and Public

Welfare (1972) ................

- vi -

Page

Ralston, The Federal Government

as Employer; Problems and

Issues in Enforcing the Anti-

Di'scr'iminatToh'" Laws^ 10 Ga.

L. Rev. 717 ( 1976) ...... . 10

Schlei and Grossman, Employment

Discrimination Law (2nd Ed.

1983) ........................... 1 1,24

S. Rep. 92-45 (92d Cong. 1st

Sess.) ................... ...... 1 3

- vii

No. 85-54

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Terns, 1985

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

TOMMY SHAW

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

to the United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia Circuit

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO THE

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

STATUTE INVOLVED

In addition to 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-

5(k), set out in the petition, this case

involves Section 717 of the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Act of 1972, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-16, which is set out in the

appendix hereto.

2

STATEMEMT

In general^ respondent adopts the

statement of the case of the petitioners,

but would like to emphasize two points.

First, a significant part of the delay

between settlement of the merits and

disposition of the attorneys' fee issue

was occasioned by the district court's

waiting for the disposition of the appeal

in Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F . 2d 880

{D . C . Cir. 1 980 ), that was taken by the

government.

Second, the issues raised by this

case should not be viewed in isolation

from the government's persistent attempts

to have fees assessed against it in

employment discrimination cases on a

different basis than that which applies to

all other employers. Following the

rejection of arguments in Copeland that

fees against the government should be

3

based on a "cost-plus'1 * * * * * * * 9 analysis, and

therefore should be lower, the government,

first in cases in the District of Columbia

and later elsewhere, has adamantly argued

that fees to a prevailing party should not

be awarded at rates higher than, first,

$60 per hour, and later $75 per hour.

This, and other practices that have led to

the prolongation of attorneys' fees

litigation, have been severely criticized

by the court of appeals^ and the district

1 Thus, in Parker v. Lewis, 670 F.2d 249,

250 n.2 (D.C. Cir. 1982), the court found

it "difficult to accept the bona fides of

a contention that a $60 per hour fee is

the appropriate maximum for an experienced

attorney in the District of Columbia."

In National Ass'n of Concerned Vets. v.

Sec, of Defense, 675 F.2d 1319, 1337-38

"(D.C. Cir. 1982), Judge Tamm, concurring,

was sharply critical of the government's

tactics in opposing attorneys' fees. He

noted repeated requests for extensions of

time, the failure to conduct any dis

covery, and the making of "broadly based,

ill-aimed attacks" and "nit-picking

claims." See also 675 F.2d at 1329-30.

In Commonwealth of Puerto Rico v.

Heckler, 745 F.2d 709, 714 (D.C. Cir.~

1984), the circuit court noted this

4

court in the District of Columbia, 2 but

Court's admonitions that attorneys' fees

requests should not result in "a second

major litigation." It warned against

"obdurate and intransigent" "non-nego-

tiable postures on fee awards" that "will

not be 'worthy of our great government.’”

2 In Kyles v. Secretary of Agriculture, 604

F. Supp. 426 (D.D.C. 1985), Judge

Oberdorfer, the district judge in the

present case, recited a long history of

delaying tactics and unreasonable posi

tions taken by the government. One result

of this history was that the plaintiff,

although she had already prevailed on the

merits, had to borrow money to pay her

lawyer. The judge concluded:

It is a fact of life that in most

employment discrimination cases the

client or the lawyer does not have

the resources to hold out for as long

as the government can protract a fee

dispute. There are strong indica

tions that, knowing this, some civil

officers of the Executive Branch have

drawn a line in the dust? any party

or lawyer who claims more than $75

per hour will have to fight for it —

through formal discovery anddilatory

motions for extensions of time and

for reconsideration, capped by

automatic appeals, many of them

abandoned when briefing time

approaches. By this form of "jaw

boning ," these officers may well be

attempting to enact a d_e facto

ceiling of $75, contrary to EFTS’

statutes enacted by Congress and

authoritatively interpreted by the

courts,

5

persist even in the face of Congress'

refusal to amend the attorneys' fees

statutes to enact such limits. ̂ Thus, the

arguments advanced in this case and Shultz

v. Palmer, No. 85-50, are part of an

overall effort to evade the clear intent

of Congress that the United States be

liable for fees "the same as a private

person."

504 F. Supp. at 436.

See also the district court's opinion in

Palmer v. Shultz, reprinted in the

petition for writ of certiorari in No.

85-50 at pp. 42a-43a.

̂ The "Legal Fees Equity Act," drafted by

the Department of Justice, was introduced

in the 98th Cong., 2d Sess., as H.R. 5757

and S. 2802. The Act would have placed an

absolute cap of $75 on fee awards against

the government and would have prohibited

all multipliers or upward adjustments. The

bill failed to be reported out of commit

tee in either house.

6

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT

SUMMARY

Respondent urges that the Petition

should be denied for a number of reasons:

First, the decision below is fully

consistent with holdings of this court

that Section 717 of the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972 was intended to

and did give federal employees the same

rights in actions brought under Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as were

enjoyed by all other employees. Chandler

v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 860 (1976)? Brown

v. General Services Administration, 425

U.S. 820 (1976).

Second , the clear intent of Congress

was to enact a complete waiver of the

sovereign immunity of federal agencies in

cases brought under Title VII to remedy

discrimination in employment. Therefore,

7

any holding to the contrary would be

completely at odds with the purposes of

Section 717.

Third, it is clear, and the govern

ment does not dispute the point, that

adjustments to attorneys' fee awards to

compensate for delay in payment are a

necessary part of calculating a reasonable

fee in civil rights cases. Indeed, the

courts of appeals have been, to date,

. . 4unanimous m so holding, and such a

4 See, e,g., Copeland v . Marshall, 641 F.2d

at 892-93; Institutionalized Juveniles v.

Secretary oi Public Welfare, 758 F.2d 897

"(3rd Cir. 1'9'8"5); Graves". Barnes, 700

F .2d 220, 224 (5th Cir. 1983); Gautreaux

v. Chicago Housing Authority, 690 F.2d

601, 612 ( 7th Cir. 19"82); Jorstad v. IDS

Realty Trust, 643 F.2d 1305, 1313 (8th

Cir. 1981); Ramos v. Lamm, 713 F.2d 546,

5 55 ( 1 0th Cir. T985) ; Johnson v .

University College of the University of

Alabama, 706 F. 2d 1205, 1210-1 1 ( 1 1th Cir.

1983). See also "Counsel Fees in Public

Interest Lit igation," Report By the

Committee on Legal Assistance, 39 The

Record of the Association of the Bar of

the City of New York 300, 318 (1984).

8

conclusion is consistent with the deci

sions of this court with regard to

attorneys’ fees.

Finally , the decision of the court

below, stating that the language of 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) that the United States

is to be held liable for costs and

attorneys' fees "the same as a private

person” requires that fees against the

federal government be calculated in the

same way as they are against any other

party, is clearly correct. The govern

ment's reliance on cases involving the

assessment of interest on ordinary damage

awards against the government is simply

misplaced,

DISCUSSION

1. Background

This case must be placed in the

context of the long, and somewhat dis

9

tressing, history of the government's

attempts to argue that despite the clearly

expressed intent of Congress, it is to be

treated differently than other employers

in Title VII cases. That history, which

need not be detailed here at length,5 6 7

began with arguments that trials of

employment claims against the government

should not be <3e novo proceedings, ̂

continued with arguments that the govern

ment could not be subjected to class

7actions, and persists with the govern

ment's efforts to argue that the relief

that may be awarded against it is less

than the relief that is commonplace when

an employer that is not a federal agency

5 Seef Brief for Respondent in United States

Postal Service Bd. of Governors v. AikensT

No. 81-1044, pp. 42-48, for a recounting

of this history.

6 Chandler v. Roudebush, supra.

7 See, Eastland v. TVA, 553 F.2d 364 (5th

Cir. 1977) and Williams v. T.V.A., 552

F .2d 691 (6th Cir. 1977).

10

is involved. Indeed, early on the

government went so far as to argue, in the

face of the clear language of § 2000e-

5 (k ) , that sovereign immunity barred any

8award of attorneys8 fees.

2, Section 717 is a Complete Waiver

oFlSoverelfc^

Thus, this case in fact raises a

broader question than that presented by

the government; if certiorari is granted,

respondent will argue that in all

respects, whether it be with regard to

attorneys9 fees or backpay on behalf of a

plaintiff, precisely the same relief can

be obtained against federal agencies as

can be obtained against any other em

ployer . We contend that this was the

clearly expressed intent of Congress when

̂ See Ralston, The Federal Government as

Employer: Problems andTs¥uesTrTEn'fbrci'ng

the Anti-Discrimination Laws, 10 Ga. lT

Rev. 717, 719 n.13 (i$76) .

it enacted Section 717 and, indeed, this

Court has so held in cases interpreting

both the language and the intent of

Section 717. Chandler v. Roudebush,

supra; Brown v. GSA, supra.

As this Court noted in Brown v. GSA,

425 U.S. at 826-827, one of the main

concerns of Congress when it enacted the

Equal Employment Opportunity Act in 1972

was to eliminate any question that

sovereign immunity barred or limited the

relief that may be obtained by federal

employees upon proof of a violation of

their right to be free of discrimination

in employment. A leading decision had

held, for example, that sovereign immunity

was a bar to an action challenging a

denial of a promotion on the ground of a

violation of the Executive orders prohi-

9biting discrimination. 9

9 Gnotta v» United States, 415 F.2d 1271

T8th”Ci7:_T969) . See Schlei and Grossman,

Employment Discr iinTsnation Law, 1 187-89 (2d

12

In 1972, of course, another concern

of Congress was to broaden the relief

provisions of Title VII generally so as to

ensure that employees who had suffered

discrimination could be made whole in

every respect. See, Franks v. Bowman

Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 763-64

(1976). With regard to the federal

government, Congress did not to attempt to

enumerate all the possible types of relief

that federal employees might obtain.

Instead, Congress simply incorporated the

relief provisions that applied to private

and state and local government employees

into Section 717's provision regarding

actions brought by federal employees. ̂̂ * 10

ed. 1983), for a discussion of the history

of § 717.

10 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(d) states that, "The

provisions of section 706{f) through (k ),

as applicable, shall govern civil actions

brought hereunder." Thus, the provisions

governing actions against private and

state and local government employers

"govern such issues as . . . attorneys'

fees and the scope of relief." Brown v.

13

In committee reports Congress

reiterated that its specific purpose was

to ensure that federal employees obtain

precisely the same type and scope of

relief that was available to all other

1 1employees . Thus , Congress' failure to

specify that adjustments in attorneys'

fees and backpay awards to compensate for

delays in payment can be made, cannot be

read as an intent to bar such relief. To

the contrary, the clear intent was to

effect a complete, total, and absolute

waiver of sovereign immunity with regard

to the remedies obtainable under Title

VII. 11

GSA, 425 U.S. at 832.

11 See, S. Rep. 92-45 (92d Cong. 1st Sess),

p. 16, reprinted in Legislative History of

the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972, a Committee Print of the Subcommit

tee on Labor of the Senate Committee on

Labor and Public Welfare (Nov. 1972), p.

425 (hereinafter "Legis, Hist„i!). See

also Legis. Hist. 1851 (Conference

Committee Report)? Legis. Hist. 85 (House

Report).

14

3 . The Decision Below Does Mot

Conf 1 ict1~wTtE~P'rlor Decisions of

ThTs~Court

The various cases cited by the

government in its petition for writ of

certiorari are simply inapposite. Neither

the language of the statutes involved nor

anything in their legislative history

indicates an intent to abrogate sovereign

immunity in its entirety. Rather, the

intent was to provide limited remedies,

depending upon the nature of the claim and

the role of the government in the circum

stances involved.

For example, petitioners contend,

petition at 8, that United States v. Alcea

Band of Tillamooks, 341 U.S. 48, 49 (1951)

can be read for the proposition that

interest cannot be recovered "unless the

awarding of interest was affirmatively and

separately contemplated by Congress." Yet

Alcea makes no mention of Congressional

15

"contemplation," nor any suggestion that

interest must be "affirmatively" or

"separately" contemplated or even provided

for in the statute. "Express" statutory

provision is all that Alcea requires. Id♦

at 49. The Act in question in Alcea, 49

Stat. 801, ch. 686 (8-25-35), was strictly

jurisdictional in nature, and was silent

on the matter of specific relief, let

alone interest. There was not, needless

to say, any analogy to private defendants.

Indeed, in all save one of the cases

cited there is no analogy, as in the Title

VII context, to any previous statutory

scheme which awarded interest against

private defendants. These cases dealt

solely with statutes that were uniquely

applicable to actions against the federal

government. U.S. ex. rel. Angerica v.

Bayard, 127 U.S. 251 (1888),12 for example, 1

12 Cited at petition, p. 9.

16

concerned a contractual agreement between

the State Department and Spain; there was

no statute or Congressional action

whatsoever. In U„S» v. Louisiana, 446

U.S. 253 {1980)f13 the disputed provision

concerned a specific agreement between the

federal government and a state regarding

receipts from minerals which had been

removed and held by the federal government

until a jurisdictional controversy could

be resolved. Id. at 256. There could be

no analogous statutory scheme regarding

private parties. Similarly, Albrecht v.

U.S. , 329 U.S. 599 ( 1 947), 14 concerned

one-time, individual land-purchase

agreements entered into by the United

States. Those contracts did not provide

for interest.

^3 cited at p. 9.

14 Cited at p. 9,

17

Petitioners cite, at pp. 9-10, a

series of cases, U.S. v. New York Rayon

Importing Co. , 329 U.S. 654 ( 1947), U.S.

v. Thayer-West Point Hotel Co., 329 U.S.

585 (1947), U.S. v. Goltra, 312 U.S. 203

(1941), and U.S. v. North American Trans.

& Trading Co., 253 U.S. 330 (1920), which

denied interest under § 177 of the

Judicial Code (predecessor of 28 U.S.C. §

2516(a)), which permitted awards of

interest against the United States in the

Claims Court "only under a contract or Act

of Congress expressly providing for

payment thereof."

Petitioners are correct that § 177

merely "codified the traditional rule,"

see, e .g ., New York Rayon, 329 U.S. at

658, but reliance on these cases is faulty

for at least two reasons. First, there is

no basis for concluding that the require

ment of expressness is lacking in the

instant case. The court below in fact

18

held that the waiver in 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-

5(k) is express. App. to petition (P.A.),

pp. 17a and 18a. Second, the cited cases

all deal with narrow and specific Acts,

leases, and contracts, in regard to which

only the United States can be a defendant

party. None reflect a complex statutory

sheme, such as that found in Title VII,

§ 717, in which Congress has elected to

establish a comprehensive parallel between

civil actions running against both private

1 5parties and the federal government.

New York Rayon concerns the Act of May 14,

1937, 50 Stat. 137, 142, ch. 180, and the

Act of June 25, 19 38, 52 Stat. 1114, 1149,

ch. 681, appropriation statutes regarding

refunds on customs duties. 329 U.S. at

659. Thayer-West Point discusses the Act

of March 30, 1920, providing for "just

compensation" for construction of a hotel

on U.S. Army property, and a private lease

between the Secretary of War and the

plaintiff under the provisions of that

Act. 329 U.S. at 586. Goltra concerns a

private contract between the plaintiffs

and the federal government, providing

simply for "just compensation" in regard

to a lease of boats. 312 U.S. at 205-06.

North American Trans. & Trading involved

an implied contract concerning the taking

of private land. 253 U.S. at 335.

19

U.S. v. Sherman, 98 D.S. 565 (1879),

also cited by petitioner at p . 10,

concerns the Acts of March 3, 1863 and

July 28, 1866, which merely confer

jurisdiction for suits against revenue

officers for which the Treasury is liable.

Id. at 565, 567. Tillson v . U .S ., 100

U.S. 43 (1879), cited at p. 11, dealt with

a "special" Act between plaintiff and the

United States, providing for relief

"equitably due." Id. at 46. There, the

Supreme Court explicitly noted that "[t]he

special statute does not even provide that

the adjustment shall be made upon prin

ciples applicable to suits between

citizens." Id.

In Title VII, on the other hand,

Congress clearly meant to have § 717

provide plaintiffs with a full scope of

remedies against the federal government,

equivalent to those available against

20

private parties. The context as well as

the language of the statute makes such a

conclusion more than "express."

The structure of § 717 and Title VII

is simply unlike any in the cases cited by

petitioners. In the cited cases, there

was not a clear intention of Congress to

construct a parallel scheme of remedies

between private defendants and the federal

government. The one apparent exception is

Boston Sand Co. v. U . S . , 278 U.S. 41

( 1 928), cited at p. 10. Boston Sand

concerned yet another "special" private

Act,^ yet this one awarded damages against

the United States "upon the same principle

and measure of liability with costs as in

like cases ... between private

parties...." 287 U.S. at 46.

16 42 Stat. 1590, ch. 192 (5-15-22)

21

In denying an award of interest

against the United States, however,

Justice Holmes found that close scrutiny

of the context of the statute indicated

that Congress did not mean to "put the

United States on the footing of a private

person in all respects." Id. at 47.

Holmes was satisfied that a subsequent

statute denying interest expressed a

policy which had been assumed for many

years previously. Congress was accustomed

to using "a certain phrase with a more

limited meaning than might be attributed

to it by common practices," i_d. at 48;

that interest was excluded in many similar

private acts was "generally ... under

stood." Id. at 47. An examination of

Congressional intent in the present case,

in contrast, yields precisely the opposite

result, namely, that Congress meant to put

the federal government on identical

footing with all other defendants.

22

As the court below noted, P.A. at

33a-34a, this case is squarely governed by

Standard Oil Co, v. U . S . , 267 U.S. 76

(1925), where the federal government was

held liable for interest despite the

absence of an express waiver. In that

case, the Court ruled that where the

Dnited States acts as a private insurer,

"it had without more consented to be

treated as a private insurer.'* P.A. at

34a. See 267 U.S. at 79.

Petitioners' attempt to limit

Standard Oil by reliance on U.S. v .

Worley, 281 U.S. 339 (1930), is unfounded.

Petitioners note that in Worley the Court

declined to apply Standard Oil "outside of

its specific commercial and contractual

context." Petition at p. 11, n.9, citing

Worley, 281 U.S. at 343-44. But such

logic begs the question, for, as the court

below noted, it is precisely in their

"specific commercial and contractual

23

contexts" that Standard Oil and Worley

diverge fundamentally, in that the U.S.

was serving as a private insurer only in

the former. P . A . at 34a, n . 1 1 6 . In

Worley, the government was merely disburs

ing disability benefits to servicemen, a

function without a parallel in the private

world. 281 U.S. at 342-43. The United

States was not acting, as in Standard Oil,

in the same role as that of private

insurers. Thus, the difference in the

essential context of the government's

position in the two cases directly

parallels the distinctions between the

litany of cases with which petitioners

buttress their claim, and the actual role

of the United States in the specific

scheme of Title VII as amended.

24

4. There Is Ho Conflict of Cir

cuits

Finally, no other circuit, to

respondent's knowledge, has held that

attorneys' fees awards against the federal

government in Title VII cases are not to

be calculated on precisely the same basis

as are awards against all other employees.

The Title VII decisions cited by the

government at p. 15 of the petition

involve back pay awards. Therefore, they

do not involve the specific language of

§ 2000e-5(k). The decisions interpreting

the Equal Access to Justice Act cited at

p. 16 are similarly inapposite.

17 Moreover, as indicated above, if certio

rari is granted respondent will argue that

those cases were wrongly decided for the

reasons outlined here at pp. 10-13. See

also, Schlei and Grossman, Employment

Discrimination Law 1214 n.175 (2d ed. ---------------------

25

CONCLUSION

For

petition

the foregoing

should be denied.

reasons, the

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

(Counsel of Record)

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

STATUTORY APPENDIX

1a

42 U.S.C, § 20Q0e~16

(a) All personnel actions

affecting employees or applicants for

employment (except with regard to aliens

employed outside the limits of the United

States) in military departments as defined

in section 102 of title 5, United States

Code, in executive agencies as defined in

section 105 of title 5, United States Code

(including employees and applicants for

employment who are paid from nonappro-

priated funds), in the United States

Postal Service and the Postal Rate

Commission, in those units of the Govern

ment of the District of Columbia having

positions in the competitive service, and

in those units of the legislative and

judicial branches of the Federal Govern

ment having positions in the competitive

service, and in the Library of Congress

shall be made free from any discrimination

2a

based on race, color, religion, sex, or

national origin.

(b) Except as otherwise

provided in this subsection, the Civil

Service Commission shall have authority to

enforce the provisions of subsection (a)

through appropriate remedies, including

reinstatement or hiring of employees with

or without back pay, as will effectuate

the policies of this section, and shall

issue such rules, regulations, orders and

instructions as it deems necessary and

appropriate to carry out its responsibili

ties under this section. The Civil

Service Commission shall —

(1) be responsible for the annual

review and approval of a

national and regional equal

employment opportunity plan

which each department and agency

and each appropriate unit

referred to in subsection (a) of

3a

this section shall submit in

order to maintain an affirmative

program of equal employment

opportunity for all such

employees and applicants for

employment;

(2) be responsible for the review

and evaluation of the operation

of all agency equal employment

.opportunity programs, perio

dically obtaining and publishing

(on at least a semi-annual

basis) progress reports from

each such department, agency, or

unit; and

(3) consult with and solicit the

recommendations of interested

individuals, groups, and

organizations relating to equal

employment opportunity.

The head of each such department, agency,

or unit shall comply with such rules,

4a

regulations, orders, and instructions

which shall include a provision that an

employee or applicant for employment shall

be notified of any final action taken on

any complaint of discrimination filed by

him thereunder. The plan submitted by

each department, agency, and unit shall

include, but not be limited to —

(1) provision for the establishment

of training and education

programs designed to provide a

maximum opportunity for employ

ees to advance so as to perform

at their highest potential; and

(2) a description of the qualifica

tions in terms of training and

experience relating to equal

employment opportunity for the

principal and operating

officials of each such depart

ment, agency or unit responsible

for carrying out the equal

5a

employment opportunity program

and of the allocation of

personnel and resources proposed

by such department, agency, or

unit to carry out its equal

employment opportunity program.

With respect to employment in the Library

of Congress, authorities granted in this

subsection to the Civil Service Commission

shall be exercised by the Librarian of

Congress.-

(c) Within thirty days of

receipt of notice of final action taken by

a department, agency, or unit referred to

in subsection 717(a), or by the Civil

Service Commission upon an appeal from a

decision or order of such department,

agency, or unit on a complaint of discri

mination based on race, color, religion,

sex or national origin, brought pursuant

to subsection (a) of this section,

Executive Order 11478 or any succeeding

6a

Executive orders, or after one hundred and

eighty days from the filing of the initial

charge with the department, agency, or

unit or with the Civil Service Commission

on appeal from a decision or order of such

department, agency, or unit, an employee

or applicant for employment, if aggrieved

by the final disposition of his action as

provided in section 706, in which civil

action the head of the department, agency,

or unit, as appropriate, shall be the

defendant.

(d) The provisions of section

706(f) through (k), as applicable, shall

govern civil actions brought hereunder.

(e) Nothing contained in this

Act shall relieve any Government agency or

official of its or his primary responsibi

lity to assure nondiscrimination in

employment as required by the Constitution

and statutes or of its or his responsibi

lities under Executive Order 11478

i

I t

- 7a -

relating to equal employment opportunity

in the Federal Government. (July 2 , 1964,

P.L. 88--352, title VII, § 717, as added

Mar. 24, 1972, P.L. 92-261, S 11, 86 Stat.

111, as amended, Feb. 15, 1.980, P.L.

96-191, § 8(g), 94 Stat. 34.)

Hamilton Graphics, Inc.— 200 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y.— (212) 966-4177