James Ferguson Interview Transcript

Oral History

April 17, 2023

50 pages

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Interview with James Ferguson for the Legal Defense Fund Oral History Project, conducted by Melody Hunter-Pillion on April 17, 2023 Conducted in collaboration with the Southern Oral History Program at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Copied!

Legal Defense Fund Oral History Project

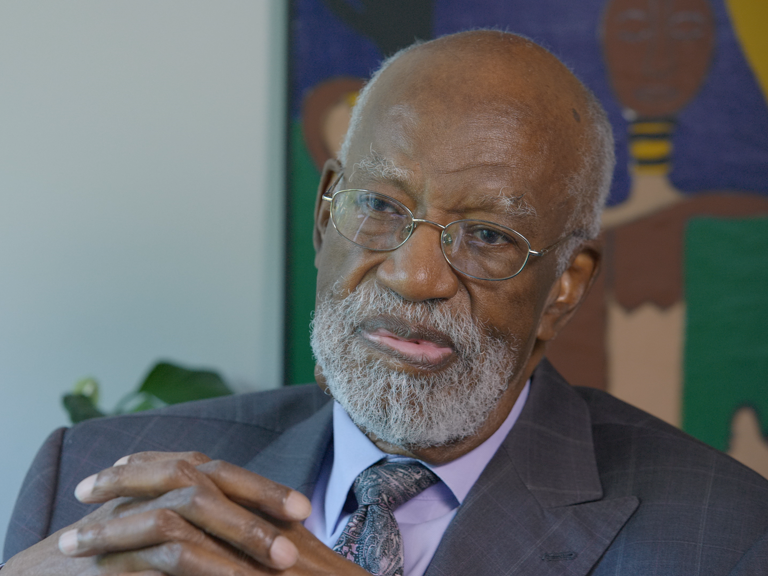

James Ferguson

Interviewed by Melody Hunter-Pillion

April 17, 2023

Charlotte, NC

Length: 02:02:04

Conducted in collaboration with the Southern Oral History Program at University of North

Carolina at Chapel Hill

LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute, NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

2

This transcript has been reviewed by James Ferguson, the Southern Oral History Program, and

LDF. It has been lightly edited, in consultation with James Ferguson, for readability and clarity.

Additions and corrections appear in both brackets and footnotes. If viewing corresponding video

footage, please refer to this transcript for corrected information.

3

[START OF INTERVIEW]

Melody Hunter-Pillion: So, this is Melody Hunter-Pillion from the Southern Oral

History Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. And I'm here in

Charlotte, North Carolina, with James Ferguson in the law offices of Ferguson and Sumter

to conduct an interview for the Legal Defense Fund Oral History Project. And thank you

again, Mr. Ferguson, for being with us and sharing your story with us and your experience

with us. Let's start with your background and we're going to go all the way back.

James Ferguson: All the way back.

MHP: Yes.

JF: That’s a long way.

MHP: Yes, it is. So, you were born, and you correct me if I'm wrong, you were born

in 1942.

JF: Yes. October 10th, to be exact.

MHP: And where did you, where were you born? Where did you grow up? And just

tell me a little bit about what your childhood was like and what the place you grew up in,

what it was like.

JF: I was born in Asheville, North Carolina, and that's where I grew up and lived

through high school. And, of course, after high school I left and went away to college. So, I

still had my home place there and my parents were there. So I still considered Asheville my

home, still do. But we, I think I was born on a street called Grove Street, which was in the

Black community in Asheville. And I mention the Black community because at the time I

was born, Asheville, like most places in the South, was completely segregated. So, there was

a Black section of town. There were streets that Blacks lived on, streets that whites lived on,

4

there were white sections of town. So everything was defined at that time, in one way or

another, by the segregated racial patterns in Asheville, North Carolina. So I grew up in the

Black community. I went to a Black elementary school, I went to a Black junior high school,

I went to Black high school. [00:02:01] Everything was determined and defined and decided

by race. During the time that I lived in Asheville, things had begun to change. Near the, well

the middle to the end of my high school years, I got involved in some of the desegregation

efforts there, even as a high school student. But we can come to that later.

MHP: I want to talk about that a little bit too. But let's go back to your

neighborhood.

JF: Sure.

MHP: And your parents and your siblings. Tell me a little bit more about the

neighborhood. You said it was Grove Street. Is that right, you grew up on Grove Street?

JF: I was born on Grove Street. By the time I was three, we moved to Blanton

Street, 97 Blanton Street. I remember that very clearly. But it was from one area of a Black

community to another area of a Black community. But at that time, Blacks could only live in

Black communities and whites could live in white communities or lived in white

communities. So, as I reflect on it, everything about Asheville was determined, defined,

delineated by race in one way or another. And when I say everything, I mean everything:

neighborhoods, schools, jobs, public transportation, you name it. Race defined it. And it was

that way virtually all of the time that I spent in Asheville growing up.

MHP: And I definitely want to ask you about how you felt. And even as a young

man, a teenager, how you felt about race and the implications for how race really

determined what sort of education you got, the facilities that you had and all that sort of

5

thing. But first, let me ask you about your mom and your father and your siblings. Tell me,

did you have a large family?

JF: [00:04:13] Some call it large. I was the seventh. I was the last of seven children

that my mother and father had together. And when I say “some call it large,” by comparison

with my mother's family, for example, it was a relatively small family. My mother was the

20th child in her family. She was the youngest and the 20th child in her family who survived.

So, it's all relative.

MHP: What did your parents do?

JF: Well, my father was a common laborer. He had several jobs during the time I

was growing up. He worked at a bakery that was called Wholesome Bakery. I don't, I can't

tell you exactly what he did there because I never knew. He also worked on the railroad for

a period of time. He worked in a place where I think they did engine work or repair work on

the trains, of keeping up the trains as they came and went with the Southern Railway. And

he did that job for a number of years. He also worked for a company called the Biltmore

Press, and he was a delivery man for the Biltmore Press. My mother, for many years, was a

stay-at-home mother. But eventually, as the children got a little older, she worked as a maid

at a white home. Again, everything I'm telling you is in that pattern of a completely racially

segregated town in Asheville. So, I was the youngest of seven. All of my brothers and sisters

attended the segregated public schools in Asheville. [00:06:18] All of them at one time or

another, went to college. I say at one time or another, because my two oldest brothers both

went to college, but they went to college after they had gone to the armed service and they

were able to get some financial assistance with college through, I think, what they called the

GI Bill, at the time. But my mother and father, neither of whom was college educated,

6

although I think my mother did have one year of college. They wanted to do all they could

to make sure that we had the opportunity to pursue a college education, and we all did. So, I

think it says a lot for them that they had that vision for us and were able to see it through.

Needless to say, we didn't have a lot of money because there weren't many opportunities for

my parents to have jobs that had significant incomes. So they had to provide for seven

children with very little money. But they did it, and they managed to do it in a way that I

never knew I was poor until I was grown. And I look back on it. I realize that we were not

just poor, very poor, but we had enterprising parents who knew how to make a penny, a

nickel or a dime or a dollar stretch to get the most out of it. So I'm grateful that I learned

from them what it meant to live and not have much money to live on. So you made do, as I

used to say, with what you had, and that's what we did. But the thing I remember most, one

of the things I remember most about growing up is that there was a lot of love and joy in my

family. [00:08:20] There was never any real discussion about being poor and having to

make do. My parents had a way of making us aware of that without preaching it and telling

us and making us feel like we were deprived as children. We never felt deprived. We felt

fortunate to be in the family we were in, to be in the neighborhood that we were growing up

in. There were lots of children in the neighborhood, and we made do for the children's play

that we did. We played I-Spy. We played stickball, as we call it. We would play ball in the

street and a car would come, we'd get out of the street. A car would slowly pass and wave

and go on. And that's what we did. So, we learned to appreciate what we had, although we

didn't have much. It was only later that we realized how utterly deprived we were, especially

by comparison to what white children growing up had in their neighborhoods. They had

football fields and baseball fields and playgrounds with equipment to swing and have fun to

7

do all those things. And we didn't have that in a significant way. Eventually, there was a

Black park that was woefully inadequate in comparison with the white park. But this was

the reality we dealt with. But it wasn't like the parents or any of the adults in the community

spent time telling us what we didn't have. They spent time making sure we found a way to

enjoy what little we did have and try to have a childhood in many, many ways. I went to the

public schools, segregated, of course, with books that were sometimes used and sometimes

passed on to the Black school, from the white school, and all the things that segregation

meant, racial segregation meant. [00:10:29] But there was no emphasis on that. The

emphasis was getting the most that you could out of what you had. And that was the attitude

in my family. That was the attitude in the education — in the community, with adults in the

community. I later learned that all of that was part of the survival instinct. You didn't focus

on what you didn't have. You focused on making the most of what little you did have,

although it didn’t seem like little at the time because whatever you had, though it was little,

was all that you had. So, it was a lot in that sense. But we now know, looking back on it,

how utterly deprived we and our entire community was at that time. And we still see

remnants of it today, but not in the same way.

MHP: You talked about your parents being so enterprising. Even under this, right,

this system of segregation and inequality and you noticed yourself as a teenager that there's

this inequality and you even just talked about it now, the difference between the quality of

the books, right. They might be used books and that sort of thing. So, I want to know if you

could talk to me about, you know, protesting against this inequality that you saw in school

facilities, school supplies. Like you described at one time as “makeshift conditions” at

Stephens-Lee High School, was that your high school?

8

JF: Yes.

MHP: Talk to me about what led you to, you know, to begin a protest that really did

make some changes.

JF: Well, one never knows exactly what it is that inspires you to do what you do.

But even though the racial segregation that was characteristic of Asheville and everything

that we did in Asheville, and even though there was not a lot of discussion about that,

growing up and seeing these differences, at some point, as a child, you begin to notice that

there were differences. [00:12:54] You knew that the school the white children went to was

a better-looking school. Eventually, we learned that the books in the schools were different.

What the white schools had, better books, they had better facilities, they had better

everything. And what little exposure we had in the early grades told you that. So, it wasn't

like you read a book or somebody sat you down and said, “Let me tell you the difference in

the Black school, in the white school, and how much better off white children are with the

books they have and the experiences that they have and the extra equipment that they have

in school.” All of the things that were different, they were differences that you came to see

and to begin to understand. But it wasn't because somebody lectured to you about it, or

somebody read to you about it. It just became evident from life. As I think back on it in

Asheville, the garbage collectors were all white. The postmen, and they were all men, but

they were all white men in my early years. The buses that we rode, the public transportation,

the drivers were white. And the reason for that is that they were positions that were reserved

for white people, and Black people just couldn’t do it, it wasn't allowed. So, at some point

there appeared to be acceptance of that among Blacks, but there never was acceptance about

it. [00:14:50] But Black people knew as a matter of survival that you didn't make a cause of

9

the inequality that was everywhere. Because if you did make a cause of it, you make a cause

of everything. Because when I say everything was defined by race, I mean exactly that.

Everything. Not some things. Not a few things. Everything. Now, over time, some of that

began to change. I think my full, I think I was aware of it as a child. But I think my full, or

fuller awareness of it started when I was in junior high school. And in junior high school I

became a part of a group called the Greater Asheville Intergroup. I think it was Intergroup

Youth Organization or something like that, but it was a group of young people. Early teens

or maybe some early teens, I’m not sure, but there would be occasions that we would meet

with some students from the white schools to talk a little bit about race, but it wasn't a whole

lot about that. But it was different to have any contact and communication with white

students because before that I was aware that the school I was going to was all Black,

students were all Black, principal was Black, teachers all Black. So, we just knew that as

part of what we did, and we knew that there were some activities that white students got to

participate in that we didn't. You know, I'm thinking that it seemed like at some point once a

year, we would go to the auditorium uptown to listen to the symphony orchestra. [00:17:05]

Asheville had an orchestra, but all the members of the orchestra were white. And the times

we went, we either went on a day set aside for Black students to go, or we would have sat in

the back of the auditorium on the balcony, if we went at the time when white students go. It

all kind of gets a little vague right now, so I don't remember. But what I do know is that

whatever we did, it was defined by race. If you were Black, you got whatever could be

carved out as the inferior part of it. If you were white, you were treated as though you

owned the event, and that this event was for you. And that just became a way of life. But

everything we did reminded us of the racial apartheid that characterized southern America.

10

If you rode a bus or if you took public transportation, then Blacks sat in the back. Whites sat

in the front. Unless there was some white person who couldn't find a seat in the front, and

you had to get up, somebody in the Black part of the bus had to get up and give their seat to

a white person. That's what was expected. And for the most part, Black people did what they

could to have as much peace in their life as they could and not to wind up going against the

establishment in one way or another and having to answer in court or in some other way,

because there were reprisals all around for those who did not conform to the racial code that

dominated everything that we did. But we survived. And to come back to where I was, we

started meeting a little bit with some of the white students, a few white and a few Blacks,

and we began to talk very mildly, very gingerly, about the racial segregated environment in

which we all lived. [00:19:24] But that was this very, very meager effort to bring together

students of one race to meet with the other race. And so, I think that's when the awareness

became more keen than it had been. Not to mention that every time I went downtown, I had

to drink from a water fountain that was designated for Black people. If I had to use the

bathroom, I had to go to the bathroom that was designated for Black people, and which was

always in a much poorer condition than the white bathroom. But that was the way of life.

Everything was segregated. The neighborhood, the schools, the churches, transportation, the

stores uptown were all stores where white people could work. There were no Black clerks in

any of the stores uptown unless it was one of the few Black owned stores on the Black side

of town, then you would see Black people and no white people there. So, it was both blatant

and subtle. And in one way or another, we learned our place. By that I mean as a Black

young person growing up, it was communicated to us that there were certain things that we

were prohibited from doing because we were Black and that only whites did. And this was

11

communicated in ways that you knew it. But nobody taught you a class on what you could

do or not do. You picked it up and you knew that this became the custom, and that custom

was every bit as clear as law, because that's the way the whole community operates.

[00:21:34] So it was like that growing up. I remember though, when I was in the eighth

grade at the junior high school, my teacher, a woman whom I shall never forget. Annabelle

Logan. And I don't like to admit this, but I was sort of a teacher's pet for one reason or

another. [laughter]

MHP: And say her name again, if you will.

JF: Annabelle Logan. She was a great teacher, she was a great person, but she didn't

smile a lot, didn't laugh a lot so you knew she meant business in whatever she did. But I

remember, she always used to listen to a news program, and the news program was called

Pauline Fredericks and The News. And I still remember today as clearly as I did then, and

Ms. Logan would always listen on her car radio to Pauline Fredericks and The News, and

she encouraged us as students to listen to that. And, you know, everybody said, “Okay, Ms.

Logan, we'll listen,” but nobody did. But on this particular day, I can’t, it had to be

somewhere near the decision on Brown. It flashed on the radio. And I was riding with Ms.

Logan to wherever she got her car maintenance done. And we were riding in the car, and we

heard this. And I remember saying at the time, “Well, Ms. Logan, that means I can go to Lee

Edwards High School next year.” I was in the eighth grade, high school started in the ninth

grade, and she nodded in assent of what I was saying. But I know now that within herself

she knew that was not likely to happen. [00:23:34] But I knew that this, that the Supreme

Court of the United States had said children can now no longer be segregated in school. So I

thought that meant me, and I was all excited about going to Lee Edwards High School,

12

which was this big high school. It looked like a college campus with a rolling green, good

looking building, and I had never been inside of it, but I had seen it passing by, thinking

what a grand school it was and how great it would be to go there. I wasn't at the time

thinking about going there, although later on, I did. But in any event, I thought I would be

going to Lee Edwards the next year, the next school year, and I didn't go. I said, “Well, it’s

all right, I’ll get there.” So, I thought the next school year when I got into 10th grade that I'd

be able to go there, in 11th grade and 12th grade. And it so happened that nothing changed

in Asheville. Nothing changed. Not a single school changed from the eighth grade until I

finished high school. Although during the interim, somewhere around the ninth or 10th

grade, the Asheville City School Board had met and decided that they would make some

change, some improvements, they called, in the schools and they were going to make some

minor improvements in the high school I attended. There was no fundamental change. And

they were, they had a program, I think, of school improvement, at Lee Edwards, the white

high school, at the same time, which were vastly better than the ones they talked about.

[00:25:35] So, some of my high school classmates and I recognized that there's something

wrong with this. So, to make a long story short, we got actively engaged in trying to make

more equal changes to our school and the white high school. So much so that we requested

and achieved a meeting with the superintendent of schools, and I think the chair of the

school board. I’m not sure of all of that, but I was kind of active with them. And so, my

classmates and I agreed that they would have me meeting with the school superintendent

and whoever who these white people were that we needed to talk to them about change. So,

I wound up at that early age, meeting with school officials to request changes, only to be

disappointed to find that there were not going to be any real changes. So, my classmates and

13

I met among ourselves and decided that we would engage in a walkout from Stephens-Lee

down to Lee Edwards, and we communicated that to some school authorities, including our

principal, who, of course, told us that we ought not to be doing that sort of thing. We said

that we would, and we threatened to do a walkout and go down to the high school if we

couldn’t get it. And then they changed and promised more for the schools, the Black high

school that we were protesting about. [00:27:43] And eventually, to avoid trouble, they said,

“Well, we'll just build a new Black high school.” So they agreed to build a new Black high

school, which, you know, and looking back, I realized they were willing to do anything

except desegregate the schools. So anyway, they agreed to build a new Black high school,

which they ultimately did. So instead of desegregating the schools as the Brown decision

required them to do, they did more to maintain segregation in schools by agreeing to build a

new Black high school for Blacks to go to, with the understanding that whites would

continue going to the white high school, and the Black high school they were going to build

was not going to be anywhere close to comparable to the school. But these were just the

lessons that we learned growing up. And during that period of time, as time passed, and as I

got to the 12th grade, I think it was in February of 1960, the sit-in movement started in

Greensboro, North Carolina, and we had become more racially conscious by that time.

When I say we, my classmates and I. We wanted to be involved in that. But Asheville didn't

have a college so we couldn’t get with the college students and go have sit-ins. So we

organized a group of our classmates in high school to desegregate the lunch counters in

Asheville, was our goal. But we were aware enough to realize that we couldn't just or

shouldn't just go desegregate or attempt to desegregate the lunch counters. We consulted

with some of the adults in the community, and the adults advised us that we should talk with

14

a lawyer or some lawyers to find out what we could about the legal implications of that.

[00:30:01] So, we did. We met with, I think at that time there were only two Black lawyers

in Asheville, and they both agreed to meet with us. Ruben Dailey and Harold Epps were the

two Black lawyers in town. So, they met with us, and we thought we were going to get this

long legal lecture from them about what the law permitted and what we could do and what

we couldn't do and be careful about this and don’t do that and whatnot. So, we expected to

get the lowdown on what you did if you were going to try to desegregate the lunch counters

in Asheville. But as it turned out, when they showed up at the meeting and we let them

know what we were trying to do and what we wanted to do, they gave us the following

advice: “You all do what you’re going to do, and if you get into legal trouble, you can call

on us and we'll be there for you and we'll help you. And we're not going to charge you

anything.” But that's basically what they told us to do. So, we were a little puzzled by that

because we expected a different kind of presentation from them but didn't get it. But in any

event, we met with the adults, our adult advisors. We were savvy enough to realize that the

adults could help, and we had adults who were willing to do that. In any event to make it a

long story short. After meeting with the adults, it turned out that in Asheville, we were able

to make contact with some other, some of the students that we knew and some white adults

in the community. And then we contacted either the store owners or the lunch counter

managers at several stores in Asheville. [00:32:02] As a result of our study of the nonviolent

movement, and that is, you don't just go create a sit-in or whatever, confrontation. You first

identify the problem. Then you meet with those who might be able to resolve the problem.

And then ultimately, if you weren't successful in getting the problem addressed, you would

do direct action with sit-ins or demonstrations or whatever you needed to do. But as it turned

15

out, when we identified the problem and sought to negotiate with those who, the white store

owners or lunch counter managers or whoever, it turned out that they agreed or after some

negotiation that they agreed to serve us. When I say us, the Black students and Black people,

but we worked it out that some white parents, I believe it was, or white adults, agreed to join

with us and the store manager agreed that we would be served. So, we showed up at the

appointed time with the understanding that we would actually be served, although they had

never previously served Blacks at the lunch counters. And I think there was three or four

stores. There was Kress’s, there was Newberry’s, Woolworth, and the managers and owners

had agreed that to avoid the arrests and the spectacles that lots of people had had in different

places around the South, they would voluntarily serve us at the time. And that's how the

lunch counters got desegregated in Asheville, we negotiated the service that we would get,

and we got it. [00:34:05] I later learned, well, not too long after that, I learned that a lot of

what that was about was that Asheville, being really a tourist town at that time, did not want

to have sit-in disturbances and arrests and all the things that were happening in other places

in the South. And they wanted to preserve the apparent peace of Asheville by not having

confrontations with the lunch counter. So, it was to serve the business needs in the town, but

it also served the need of making a peaceful transition at a critical time. And so, we did that.

And from that, our group, and we eventually called our group the Asheville Student

Committee on Racial Equality. I think we did that because CORE, the Committee on Racial

Equality was a national Black organization, which was well known at the time. So, we kind

of adopted into our organization the name of CORE, but we called it ASCORE because the

core part of it was preceded by Asheville Student. So, we were the Asheville Student

Committee on Racial Equality, and I was the first president of that group and, you know, the

16

group carried on after that. There were other students who became a part of that movement.

And over time, we not only desegregated the lunch counters and other public facilities, but

we negotiated jobs at the local grocery stores. At that time, it was Winn-Dixie and A&P, and

we as students met with the managers and owners of those stores and other white-owned

stores in Asheville to begin to desegregate employment. [00:36:20] At that time, if you were

Black, you couldn’t get a job as a bag boy, as they called it. But we negotiated to get the

stores to hire Black bag boys, and some of the department stores in downtown Asheville

agreed to hire Black clerks to work in the store. So, we eventually desegregated the city, and

we did it all by negotiating with the powers that be, the owners of the stores. And although

at the time we first did the lunch counters, I and many of my classmates were seniors, we

wanted to make sure the movement continued after we left. So, we recruited underclassmen,

as we call them, to join ASCORE. And ASCORE continued for a number of years after that

and basically desegregated all of the public facilities in Asheville, a lot of jobs that were

heretofore prohibited to Blacks. We did that and it was an ongoing organization, so much so

that 20 years after we got out of school, we had a reunion of ASCORE and all of the

students who participated in ASCORE came back and we had a reunion. And then we had, I

think we had one or two of those. So, it was a big deal in Asheville. But Asheville

desegregated differently from many other places, primarily, I think, because we had no

Black college in the town, so we didn't have sit-ins. And also because of the tourism of

Asheville and the powers that be at the time did not want Asheville to be disrupted by sit-ins

and other civil rights related activities. So that was my experience in participating in the

desegregation of Asheville. [00:38:28]

17

MHP: And I have two follow-up questions on that. One, ASCORE, right, one of the

important, one of the reasons you guys were successful was because of recruitment. How

did you go about recruiting people? What was that strategy?

JF: Oh, well, much tougher than it seemed. Those of us who were initially the

leaders of ASCORE, and I say those of us that we, it was mainly our class, which basically

was a senior, the senior class. As we were moving forward in school, we realized that we

would all be leaving to do whatever seniors do when they leave high school, go to college or

get a job or go up North as we used to do, all of those things, that unless we had someone to

carry on what we were doing, then what we started might die out. And none of us wanted to

see that. And we knew of underclassmen that were interested in what we were doing. So, we

identified people or people came to us who wanted to carry on what we had started, and we

invited them in, and they came, wanted to come in. So, they joined with the understanding

that they would be carrying on the work that we started and that although many of us who

were seniors wanted to stay involved and would stay involved, we couldn't do it on an

ongoing basis because we'd be away in school, or away doing whatever we were doing, so

we recruited a number of young people. And I’ll mention as an aside, one of the young

people we recruited became the third president of ASCORE, and I remember that very

clearly because she also eventually became my wife. [laughter] So, I met my wife through

ASCORE, and we dated, you know, in high school and then through college and even law

school. [00:40:38] And then we eventually got married. And we had a wonderful

relationship and we spent 55 years in marriage together. And she passed on in August of last

year. But we had a great time together, we have three great children who are all here now

and still doing good things. So, you never know what an experience is going to take you to.

18

MHP: Here's a — and congratulations. I mean, 55 years, that's a long marriage.

JF: That’s a long time, but it didn't seem long, just seemed natural.

MHP: Exactly. My other follow up question is, here you are growing up in this town

that you clearly see has a certain way of, right, how things are divided, in every sector:

education, jobs, everything. And teenagers come in and start changing it. You are leading it,

and it happens through the art of negotiation, it seems like to me, right. So, it’s very peaceful

and that sort of thing. But you don't know that's going to be the outcome as you're going into

it. So, did you ever have, as you were going into this and sort of in a way, making waves

and rocking the boat, did you ever have any personal concerns about the consequences and

that sort of thing, or personal harm to you or your family?

JF: Well, you know, one of the great things about being young is you don’t think

about that. [laughter] You do what what’s in front of you. You do what seems to be the right

thing to do and, you don’t spend a lot of time in fear. You don’t spend a lot of time worrying

about what the ultimate consequences might be and that you might not be able to do this or

you or somebody else might get hurt. You really don't think about that. You think about

what needs to take place at that time. It's not a recklessness, but it’s just a focus that there’s a

certain feeling of invincibility that you have. You don't recognize it as being that at the time,

but you look back on it and you say, “Wow, now that I look back on it, that was all a little

crazy. This could have happened, that could have happened,” but none of it did. [00:42:47]

Fortunately. It worked out. And that's one of the great things about youth is that there's a

certain freshness that youth brings to whatever they're doing, and they don't have a lot of

concern about negative consequences, until later. And then they realize perhaps they could

have, should have, had that concern, but there’s no need to have it later on because time has

19

passed from when things like that happened. So, it's a good thing in many ways. But

sometimes you reflect on it and think, “That was pretty crazy.”

MHP: Oh, okay. Here's another group, though, that you were also a member of,

sponsored by the National Conference of Christians and Jews. Can you talk about that group

and what you learned from that involvement, how it might have impacted your work later

that you would do when you became an attorney and you were in Charlotte, in an integrated

law firm?

JF: Well, you know, as I look back on that experience and the ASCORE experience,

which I've already described to you, this was, I mean, they were all life experiences in that I

was being introduced to a different life than what I had seen growing up, because, you

know, I said I grew up in a completely segregated Asheville. I can't even look at anything

and say everything except this was segregated. Everything was segregated. But somewhere

around the same period of time that I was describing in junior high school or early high

school, we became part of a group called the Greater Asheville Intergroup Youth

Association, I think is what we called it, and that was a group of students, Black and white,

that began to meet to talk about and, you know, I talked about it a little bit already.

[00:44:46] But as a part of that, we got involved with, I think of the acronym NCCJ, I guess

that’s National Conference of Christians and Jews, and all of this sort of comes together.

And it was all part of our growing into circumstances where we began to see and

communicate with people beyond our racial group. We reached out to others and others

reached out to us. So, as a result of our participation with NCCJ, we met more than we

otherwise would have with white students of goodwill who also wanted to see something

change and who wanted to have the experience themselves of interacting with Black

20

students, whether they never had the opportunity to do that. And I remember we used to

have NCCJ, Greater Asheville Intergroup Youth Association meetings at different places. I

remember that we had a meeting out at a place called, I think it was In the Oaks. It was a

conference center on the outskirts of Asheville. I think it was out in Swannanoa, or Black

Mountain, a town, probably 10 or 15 miles away. But we met there because there were no

places in Asheville that you could have an integrated, racially integrated group meeting. So,

we wound up engaging there. So, we did it. And all of the details I can’t remember, many of

them escape me, but I do remember that it was a very positive feeling of goodwill. It was an

experience beyond the experiences, the segregated experiences we had before. And we were

beginning to see that there were people of goodwill who wanted to see change. [00:46:46]

They had a different perspective on it because they had never experienced the sting and the

bite of racial segregation in the way that my Black colleagues and I had, but they were

people who wanted to see change and were willing to make sacrifices to bring about that

change. And that was a good, a good experience for all of us because it promoted feelings of

goodwill outside of our own racial groups both ways. And I think that's something that we

learned in life and that we've carried with us. At least I know I carry it with me now. I don't

look at white people, even those whites who still reflect the white racism that affects us all

too much. But it's not because they are people who are by nature of bad will or they’re bad

people or anything like that. They are all the result of their experiences. People deal with

that experience in different ways, but we learn that there are ways to reach people in

different ways. And we do that, and we continue to have this belief that there are those who

want to rise above the racial restrictions that they and I and others experienced growing up.

21

MHP: [00:48:15] Okay. So, Mr. Ferguson, we were talking about how early on,

even as a teenager, you said, you know, you really wanted to be part of a helping profession.

You choose law, of all things. So, tell us how law became something that really attracted

you and you felt like that's where your calling was.

JF: Well, as I look back on it, I realize that there were a couple of salient

experiences that I had during my high school years that inclined me towards law. One

happened when I was a teenager, I think in the 10th grade. Some friends of mine were

charged with rape. These were Black friends of mine, and they were charged with raping a

white woman. They were charged with raping a white woman in a place called Aston Park.

Aston Park was a white-only park at the time. But that whole incident strikes me because I

don't know what happened that night. I know that the nine young Blacks who were

eventually charged and who eventually entered a plea of guilty, and I need to talk about that

when I come to it, were friends of mine that I saw every day, grew up with. And I had, they

had actually invited me to join with them that night, it wasn’t to join with them in a rape.

But at that time, there were some young Black guys who had this notion or had been told or

whatever, that they could go down to Aston Park at night and that they could engage with

white women who hung out there. [00:50:22] And so, on this particular night, I was at a

high school dance, and some of them invited me to join with them, not to go to Aston Park,

but to just hang out with them that night. I didn't go, because I had a young lady I had my

eyes on at the sock hop, they called it, that night, so I didn't go with them. And then I think

the next day or so, the headline news said, nine young Black men charged with rape. And I

realized then that I could have easily been one of them. Well, I mean, they've all denied

engaging in any rape that night, but I could have easily been one of them. And it wasn't

22

because I was any different from any one of them. These were people I knew. They were

good friends of mine, and they were people I enjoyed spending some time with, you know,

some or all of them. I did. And I later learned, well, eventually they all pleaded guilty. And

of course, you know, I and others wondered why they were pleading guilty. But later in life,

I got to know the lawyer who represented them, really one of the lawyers who eventually

met with us to talk about the legal implications of sitting in. But he explained that at that

time in Asheville, which had a very small, relatively small percentage of African Americans

in the population, that these young men were likely to have a jury that was all white and

with an all-white jury in Asheville or any other southern town of that day, they were likely

to be convicted and were likely to be given the death penalty. [00:52:30] At that time, rape

carried death. But you could avoid the prospect of a death penalty by pleading guilty and

you would automatically get life, life imprisonment at that time, then 40 years. If you had a

40 year sentence, you'd be eligible for parole in 20 years. So, all of that went into it. And

rather than risk death, as they all would have been doing, they entered pleas of not guilty

and I've talked with some of them, you know, afterwards.

MHP: Oh, I’m sorry, pleas of guilty? They entered pleas of guilty?

JF: They had pleas of guilty to avoid the death penalty. And I've known that there

were, two things I learned, many things, but two things in particular stand out. One is I

learned that everybody who pleads guilty doesn't do so because they're guilty. Sometimes

they do so for other reasons. Like in this case, they pleaded guilty to preserve their life or to

escape death. So, one of the lessons that I learned that stayed with me and really helped me

in my work as a lawyer is that everybody who's in prison, number one, is not necessarily

guilty. And number two, that they are human beings just like myself. I could have easily

23

been one of them. So, I always thought about that in the criminal work that I've done over

my lifetime, that whoever the person is, the charge is not some lawbreaker or some evil bad

person who deserved to be in prison, but they were people who had unfortunate turns of

events, whatever they might happen to be. And it's all different. But they were not inherently

or inevitably bad people. [00:54:36] They were good people that bad things happened to for

lots of different reasons. But it always helped me to understand that we have to be careful

and reserved in our judgment of people because, you know, there’s this saying, “There but

for the grace of God, go I.” For me, that was real. Because, you know, when I look at each

one of those friends of mine who wound up with these long prison sentences, there but for

the grace of God, could have gone I, except I happened to be in a different circumstance that

night. Whatever happened at the park, I don't know. But it’s always tempered my judgment

of people, too. You can't judge people just by what you see in the moment, but you have to

understand who they are, how they got to where they were. So, that experience happened. I

think I was in the 10th grade, and they were all represented by the same lawyer at the time.

And, you know, that had all kinds of implications for conflicts of interest, et cetera., et

cetera. But this was a lawyer who represented these young men who did not have funds to

pay the lawyer. I know that. I don't know what their arrangement was, but they were doing

this because they recognized that in this community in 1958 or [19]59 or whenever it was,

that five young Black men, nine young Black men charged with the rape of a white woman

were likely to get the death sentence if they went to trial. So, the lawyer, Mr. Dailey,

stepped in, helped them, and later explained to me as I got to know him when I became a

lawyer, some of the thought processes he had to go through to get to where he did at that

point. [00:56:36] So, I want to fast forward two years, when Mr. Dailey and Harold Epps,

24

Mr. Epps were the two lawyers who met with us when we were considering doing sit-ins in

Asheville, and they didn't give us a lecture on law. They said, “Do what you need to do, and

if you need our help, let us know and we'll be there for you.” Not one word about “Our fee

is going to be this. Our fee is going to be that.” Or this complication and that complication.

They were there. They recognized and supported what we were doing. They wanted to help.

And their help was encouraging us to go ahead and do what we were going to do and that

whatever they needed to do, they would help us out. I thought about that. I said, “That's a

fantastic position to be in, to be able to help people by telling them they can call on you

when you need them, and you'd be able to offer something that they might not be able to get

otherwise.” None of us had any money. So, we couldn't have paid. They didn’t charge us

anything. They didn’t talk to us about fees or anything else. They wanted to be helpful. They

wanted to be supportive and said call us when you need us. And I often thought, “That's a

wonderful position to be in, to help people, to say, let me know what you need. I'll be there

to help you.” So, that was a big factor in my decision to pursue law as a career. And I've

always wanted to view law as a helping profession, not just as a way to earn a living, but as

a way to be helpful to individuals, to be helpful to a community. And I've always felt that it

was important to find ways to be helpful to others and to our community, particularly the

Black community that we lived in, which needed and still needs lots of help. [00:58:44] So,

and fortunately, I came into a law practice with my partner, ultimately, Julius Chambers,

who was doing exactly the same thing at the time, and we came together by chance. But it’s

the best thing that ever happened to me in many, many ways. And if we get a chance, I'll

talk a little bit about it.

25

MHP: Oh, definitely. I want to ask you about that. Real quickly, let me ask you,

before we get to that part, just very briefly, if you could talk about were there, because

before you went to law school at Columbia, you did your undergraduate work at North

Carolina Central University. At that time, it might have been NC College. Or was it NC

Central?

JF: What was it? North Carolina College at Durham was the name of it. Yes.

MHP: Were there any particular classes you took that, as an undergraduate, that also

sort of, you know, even further encouraged your desire to become an attorney?

JF: Well, fortunately for me, or unfortunately for me, I knew at the time I went to

college that I wanted to get into law. So I took a double major. History and English were my

majors. And in the history department, I met a professor who became a great mentor to me,

and he was also a great mentor to other people, Caulbert Jones, was one of my history

professors, and he was also my advisor when I became president of the Student Government

Association. He was the advisor for that. So he was someone who mentored me in ways that

I didn’t even know I was being mentored. But he was always there and could, you know, he

was easy to talk to. So he was a great influence in my life. And he also assisted me in

identifying where I would go to law school and helping me find ways to get into law school,

because I had a lot of enthusiasm and a lot of desire, but no money. [01:00:58] And he

helped me navigate that. He and some other teachers. But he was one of my main college

mentors, in the history department, but also in the student government work that I did, really

from the time I was a sophomore until I graduated. So, I'm grateful that I had the

opportunity to meet him and others as well. But he stands out because of the particular

relationship we had with the history department and the Student Government Association.

26

MHP: So, you graduate from Central, you go to Columbia Law, and you earn your

J.D. in [19]67. At least that's what we have here.

JF: That's correct.

MHP: And once you were at Columbia, you're getting out there. I mean, was there a

particular, did you already know the type of law that you wanted to practice when you were

at — yes?

JF: I did.

MHP: And tell us about that.

JF: I went to law school because I wanted to be able to do something to help my

community. I wanted to be able to carry on the work that I had started in high school when

we desegregated the lunch counters and when we worked to desegregate the schools.

Although it didn't happen while I was in high school, I did have the pleasure of handling the

Asheville school desegregation case and seeing the Asheville schools actually become

desegregated years after the Brown decision came out in 195[4]. But there was some

gratification I got from being involved in the Asheville school case, as well as other school

cases, but particularly in Asheville, because I thought Asheville should have been

desegregated when I was a junior in high school and it wasn't. So, whatever I could do later

to bring that about, I was glad to do that. [01:02:59]

MHP: So, that came full circle. So, full circle for you.

JF: Full circle. Yes.

MHP: While you're at Columbia, I guess during your last year there in law school,

you were approached by the LDF offices from what we've read, and Susie did all the great

research here.

27

JF: Well.

MHP: You approached them, or they approached you?

JF: I was about to say, I approached them.

MHP: You approached them, sorry. About their internship program. So, can you

talk to us a little bit about that, your impressions of LDF, of the office, the people who

worked in the organization, the type of work they were doing?

JF: Oh, absolutely. When I was at Columbia, even in 1964 when I went there and

[19]67 when I graduated, that was a very small Black student population. I think in my class

there was somewhere between, I think, nine and 11 Blacks out of a class of 300. And

likewise with the other classes at the time. So, it's not as though there was a core of Black

students at Columbia. So, fortunately the few of us Blacks who were there bonded together

in one way or another, probably because we were Black in a predominantly white

environment. So, you gravitate towards folk that you think have things in common with you.

So, I knew certainly all of the Blacks in my class, but most of the Blacks who were in the

law school at the time, which was just a handful, we came into contact with each other in

one way or another because we were Blacks in a predominantly white environment, trying

to make a life for ourselves. And that was just a common experience wherever we were

from that led to some gravitation towards each other in that environment.

MHP: [01:05:12] And so, LDF, you approached them, and what type of, you did the

internship. What, can you tell me a little bit about working with them, what type of work

you did, what, how they were to interact with?

JF: Well, I will, but I have to give you a little bit of background on that. I knew

when I went to law school that I wanted to return to the South to do something to help the

28

Black community. That’s why I went to law school. And I knew that in undergraduate

school. And I suppose it's all a part of the experience that I've already described to you. So

the interesting thing, one of the interesting things about going to Columbia for me was that

Columbia being the Ivy League school that it is, it had this wonderful reputation. And a lot

of folks went there because it had that reputation and because they felt that Columbia would

give them opportunities that they might not find at other places. Well, I wasn't going there

so much for any opportunities that Columbia, in and of itself offered, but I wanted to get a

good education, because I wanted to be the best lawyer that I could to go back and help my

people in the South. So, I never went to law school for the purpose of getting a plum job

with some big white law firm and advancing in the law, that was never my interest in law

school. So consequently, in my senior year, when many of my colleagues, Black and white,

were signing up for interviews with all these firms that came to Columbia and offered high

paying jobs and this and that, and students, my friends, were nervous and biting their nails

about whether they would get this job and whether they would just get the interview with

this firm, you know, all of that, I never experienced all of that. I knew from the beginning,

from the day I walked in, applied to that law school, that my purpose was to go back South.

[01:07:11] And I actually went with the idea of going back to Asheville to practice, my

hometown, Asheville. But it turned out another way. And it is interesting the way that

happened. I found out, somehow, about the Legal Defense Fund program, which was

designed to help Black lawyers, in particular, from the South, return to the South to practice

law. So, one day in my senior year, it was in the spring of the year, I went down to the Legal

Defense Fund. I had no appointment. I just knew about the Legal Defense Fund, and

Thurgood Marshall had been a part of it. And yeah, I knew something about Jack Greenberg

29

who headed it at the time. So, I just, I wandered down there one day with no appointment

and I went down to the Legal Defense Fund to get more information about their program,

helping Black lawyers set up civil rights practices in the South. It just so happened that on

the day I went to the Legal Defense Fund to talk to Mr. Greenberg or whoever I could about

their program, one of the interns who was practicing in the South showed up. It was an

intern that I knew about but did not know. His name was Julius Chambers. It just so

happened that Chambers happened to be at the Legal Defense Fund the day I happened to go

down there. I had heard about Chambers because when I was in, I told you about Professor

Jones, I told you about Caulbert Jones, my professor, when I was in his class, he used to talk

to me sometimes. When I was in class, he’d look at me and he would call students so you’d

get nervous. [01:09:11] “Ferguson, you’re sitting right in the same chair that a great lawyer

sat in. His name was Julius Chambers. He sat right there.” And I shuddered and went, “Oh

my God, what comes next?” So, I knew Chambers’s name, but I didn't know Chambers.

And so, when I realized that Chambers was at the Legal Defense Fund that same day I was

there, I was flabbergasted. And Jack Greenberg said, “I’ve got somebody I want you to

meet,” and he introduced me to Julius Chambers. And you know, when he said Julius

Chambers, I thought there was just this great lawyer who was bigger than life himself. Oh,

how fortunate I was to even be in the same city he was in at the same time and in the same

place and have a chance to meet him. I mean it was like the gates of heaven opening up. So,

Jack Greenberg introduced us, and Chambers, instead of meeting this image of, you know,

one of the brightest, greatest young lawyers that was in the world, he said, “How you doing?

What’s your name? What are you going to do when you get out of law school?” [laughter] I

mean, that's basically how the conversation went. And I said, “Well, I want to go back to

30

Asheville, North Carolina, and practice law.” And I'll never forget, he said at the moment I

told him that, this was right after we had met. He knew nothing about me. He said, “Well, if

you’re coming back to North Carolina, and you want to do civil rights law, you might as

well join me. I'm doing it. And I need more help than I got. So, you ought to think about

that.” So, you know, we had a conversation, and before the conversation ended, and it wasn't

a long conversation, he invited me to come to North Carolina during spring break, this was

just before spring break, and spend some time seeing what he did to see if I had some

interest in joining him. And of course, I said, “Yeah, I'll be there.” [01:11:11] So, at that

time, he knew nothing about me. He knew nothing about my grades, he knew nothing about

any of that other than I was a young Black person who wanted to come back South and

practice law. And he invited me to come join, not just to visit with him, but to stay at his

house. I stayed at his house, a total stranger to him and his wife, Vivian. So, that's how I

spent my spring break my senior year in law school. And at the time I was here, which was a

few days, I don't know, I just kind of followed Chambers around with whatever he was

doing, and he was here and there, doing whatever he was doing. And I just followed him

around and, you know, we’d chat and we'd go here, sit there in the evening at his house or

whatever, and at the end of that time, Chambers asked me to join him in his practice. He

knew nothing about a single grade I had earned in law school. There was no reference. It

was just his feeling that he needed some help. And here I was looking to come this way.

And he said, “Well, why don't you come join me?” And I said, the only thing I could say,

“Are you serious? Of course.” [laughter] So, it was just that incidental that I met Chambers

and accepted his invitation to come join him in his practice. Now, as it turned out, Chambers

had no office for me to work in, nor did he have an office for Adam Stein, who had worked

31

with him the summer before and maybe the summer before that. But he had invited Stein to

come in. [01:13:12] So, I showed up, I think, in September after I'd taken the bar and done

this and that, and Adam showed up. And Chambers, or Ella Hand, who was with him at the

time, showed us where we would be working, which was this table in a room that they

called the library that had two chairs in it. And Adam sat in one chair, and I sat in the other

chair, and for months we occupied the same table as a desk in the old office, at I think it was

405 and a half East Trade Street, which is where the Panthers stadium is now, not the

Panthers stadium, but where the Hornets basketball arena is now. And Adam and I hit it off,

well we had to because we sat across from each other every day. And from September until

the spring of the year, that's where we were. And in the spring, Chambers, Adam, and I, and

an additional lawyer named Jim Lanning, who was a young lawyer, who had just come to

town with the legal services program, but he was interested in doing some of the same kind

of work that we were interested in doing. So, we met and talked about forming a law firm

with Chambers as the, of course, the senior partner who had been in practice two or three

years, not more than four, I think, at the time. None of us had any idea of what it meant to be

in a law firm, and that included Chambers, who had never worked at a law firm. He’d spent

some time in the Legal Defense Fund as an intern in the internship program that I thought I

was going to work in. But I never actually worked at the office in New York. Chambers by

that time had developed a kind of relationship with Jack Greenberg, the head of the Legal

Defense Fund, that they arranged for me to come directly to Charlotte and not have to spend

the usual year that an intern would spend learning whatever interns learn in that first year of

practice. [01:15:27]

MHP: So, in that first year, normally they would be in New York.

32

JF: In New York, working out of the Legal Defense Fund office. You know, they

would do some work in the South but not have an office in the South. But I wound up in the

South, and Chambers needed help. He had more cases than any one lawyer, any one super

lawyer, could handle. And that's how we wound up in Charlotte, how I wound up in

Charlotte instead of Asheville, where I was planning to go, because Chambers said he

needed help. And even though he didn't know who this lawyer was, he was hiring and he

hired me. And that's the best decision I ever made, was to not to persist to go to Asheville,

my hometown, but to recognize the opportunity I had to work with one of the greatest

lawyers in the world and who turned out not only to be one of the greatest lawyers in the

world, but the greatest friend I could have possibly met at that time. And all of the years we

worked together were among the best years of my life. Just having the opportunity to work

with such a brilliant lawyer and to be befriended by such a great, gifted friend. So, I think

about that all the time and how fortunate I was. It wasn't fortune. It was just luck because if I

hadn't gone that day, at that time, I may never, I would not have been offered a job by

Chambers under that same circumstance. So sometimes you go with the flow of what's

going on at the time. I didn’t spend one second saying, “Oh, but I’m planning to go to

Asheville.” He said, “I need help.” I said, "Well, I'll be there.” And that's how we formed

the law firm, which was the first racially integrated law firm in North Carolina. There had

been some Black lawyers who worked in white firms, but not a racially integrated law firm

up until 1967, when we just by chance again decided that we would have this law firm and

that we would do civil rights work in Charlotte, North Carolina, in 1967.

MHP: [01:17:52] So, at that time, so it’s Mr. Chambers, and he brings you in. He's

brought in Adam Stein also.

33

JF: And Jim Lanning. Jim Lanning was a lawyer we met here. The four of us

formed [inaudible].

MHP: Okay. And then Ella Hand was here.

JF: Ella was here. Ella was the star of the law firm then. She and Chambers were

classmates at North Carolina Central, and Ella was a major in, whatever it was.

MHP: Education, I think.

JF: Yeah, well, I think she majored in business.

MHP: Business, yes, that’s it, business.

JF: And she set up the law firm with Chambers when they both got out of law

school. I mean, when Chambers got out of law school. He knew Ella from school and

brought her in to set up to practice with him.

MHP: And let me ask you before we get, because this seems like a good time to

bring her in, but I just want to ask you one more question. As you're here, you're starting out

working. What was that like, those first experiences or those first cases of what you were

working on? What kind of work was it that you were doing? Like in that first year?

JF: The kind of work that I was doing was whatever work came into the office, to be

honest with you. It wasn't like Chambers sat us down and taught us how to be civil rights

lawyers. Civil rights work was here, but the practice at that time was what I later came to

formulate in my mind as Black people’s law because Chambers was here, but people came

to Chambers with every issue that they had. It might be landlord-tenant, it might be

something dealing with consumer practices, it might be anything that people had a problem

with. They came to see Mr. Chambers. I'll never forget, one lady traveled here, and they

would come bringing these big bags of papers of this and that and whatever, but they were

34

coming to see Mr. Chambers because Mr. Chambers was going to help them in one way or

another. [01:20:00] So, it wasn't like a civil rights law practice. I mean, it was that, but it

was a practice. It was a people's law practice. And whatever problem you had, we would

find a way to do it. Chambers as, you've heard the story before about how his father was

cheated by some white man who worked on his car. No, Chambers’s dad had done some

work on a white man's car, man never paid him. Then Chambers’s daddy couldn’t find a

lawyer to help him, all the white lawyers in Mount Gilead, whatever the county was at that

time. So, there was this man who cheated his daddy, his daddy couldn’t get anybody to

represent him. So, I think Chambers always saw every client who came in as being his

father. A person, mostly Black people came, who needed some help, and they needed to find

a lawyer who was willing to help them, not lawyers who, I mean, not people who had

money to come in and hire a lawyer to do whatever they wanted. They were people in need.

And Chambers saw himself, and we all picked up on that as being there, to help people who

needed help and whatever help we could provide, that’s what we did. Some of that helped

that needed was helped with civil rights cases and we did them. But it's not like we had this

specialty, and if you didn't fit the specialty, we couldn't help you. If you had a problem, our

job was to find a way to help you. And we tried to do that. And that was really the result of

joining with Chambers to try to help people who needed help.

MHP: And who before maybe didn't have a place where they could go or turn for

that help, especially if they didn't have money.

JF: Especially if they didn't have money. And especially if they had a civil rights

problem. It's not like there were all these white lawyers in town who wanted to help folks

with the civil rights problem. There were very few Black lawyers, period, and very few who

35

set up their practice to be civil rights lawyers at that time in Charlotte. [01:22:10] I think I

remember that at the time I came to Charlotte to join Chambers, I was the seventh Black

lawyer in Charlotte. And I got to know all the Black lawyers who were here at that time and

others, you know, who came, many others who came after that. But we went from seven

Black lawyers in Charlotte in 1967 to probably 500 or 600 now. So, I don't know all who

they are, but whoever they are, they owe a debt to Chambers in some way because he started

with the civil rights practice. And the other lawyers who were here at the time were Black,

other Black lawyers who were here, they were lawyers who would lend a hand to help in

whatever ways they could. And at that time, everybody knew each other, and we worked

together in whatever ways we could. And if they had a particular problem they thought we

could help with, they felt free to come, knowing that we would help. If we had problems, we

thought they could help with, whatever it might be, we knew we could reach out to them and

that they would respond. So, it was a different world that we came into. But a good world

and a world where we were all trying to succeed with helping a community that sorely

needed help.

MHP: Let's start, you know what? Why don't we start with Asheville before we go

to Swann v. Mecklenburg? I’m going to.

JF: Sure. They were around the same time; I just can't remember the exact.

MHP: But I'd like to start with Asheville, because in many ways, it's where you as a

person who wasn't a professional yet, who is just still a child. It's kind of where you started

with, you know, with activism and in being a champion for civil rights. So, talk to me about

the Asheville school case. How do you come about being involved in that? Tell me about

the case and the work on it, and was LDF involved in it?

36

JF: [01:24:12] Oh, yeah. It was a LDF case. Yes.

MHP: Let’s talk about it.

JF: Okay. Well, all of the school desegregation cases are close to my heart because I

think, you know, that has made such a tremendous difference in providing opportunities that

many of us who grew up before the schools were desegregated never had. And the

desegregation of schools in many ways fueled and led to the desegregation of America. And

I think about the Clarendon school case and the experiments with the Black dolls there,

which tells the story of just how much segregation affected the children who grew up with

the segregated education. That’s a whole story in and of itself. But it just, when they showed

Black children these dolls and all of the Black children chose white dolls, begins to tell you

just how powerful this whole system of apartheid in America has been on myself and other

youth who were subjected to that. But the Asheville school case has particular significance

to me because I view it as the culmination of the desegregation process that I and my

classmates started when we were in high school. And I've already talked about how the the

Brown decision came down when I was an eighth grader in the Asheville public schools,

going through the completely segregated public school system there. And one of the things I

dreamed about, I think, was having a racially desegregated education when I was a youth.

[01:26:16] And that never happened for all the reasons that it didn't, well I guess it wasn't

supposed to. But there was the gratification I got later when I handled the Asheville school

desegregation case and Chambers, being one of the most humble people I've ever met in my

life, actually basically turned that case over to me, and I wasn't experienced enough to know

what I was doing, but I was willing to take it because it was important. And I got to work

with Ruben Dailey, who was the lawyer that we had consulted when I was in high school,

37

and we were doing ASCORE. So it just had all of the significance in the world to me. And

then I had the honor of being able to participate in the litigation in that case. So it was one of

the high points and remains one of the high points of my life. So I was the principal lawyer

in that case, believe it or not. And it was only a few years after I'd gotten out of law school

that that case came up and we litigated that case and we were successful in bringing about

the legal decisions that led to the desegregation of the Asheville city schools. And I use that

term advisedly because we call it the desegregation of the schools. But anyone who

followed the desegregation movement in the South knew that it was called the desegregation

of the schools. But it really wasn't the desegregation of the schools. It was the legal remedies

that were imposed to try to bring about the desegregation of the schools. [01:28:18] But

what we had in Asheville, Charlotte, and throughout the South, was a series of legal

decisions or legal agreements that were supposed to desegregate the schools, but never

really did. And we can highlight that now by looking at the schools in Charlotte, which are

largely segregated today. Many, many years, decades after Brown. So, when I say

desegregation of the schools, I'm using that term advisedly as a term of convenience, but not

necessarily a term of reality. But in any event, one of the greatest gratifications I have had as

a lawyer practicing law here in Charlotte doing desegregation cases and other cases

designed to liberate the Black community, which has been unliberated for so long. Then I do

that with the idea in mind that we did what we could under the circumstances at the time.

But we have yet to see a society that is fully and meaningfully desegregated. Maybe one day

we will. But there's also this question of whether we will or not, because what we see is we

make some progress and then we have some regression and then we come back and make

progress, all of that. There's nothing new about that, it’s just real. And we have to face up to

38

where we are. And all of this has been to try to create that society where people, every

citizen of that, every person in that society has the opportunity to realize all of his or her

potential. [01:30:21] And we still maintain the hope that that will happen. But we have the

realization that it hasn't happened yet. And we've been working on this for centuries. So, it

may not happen, at least not in the way that we think. But now back to the Asheville school

case. It was the greatest gratification for me, that I was able and fortunate enough to be one

of the lawyers in the Asheville school desegregation case. And that case resulted not so

much in a decree that desegregated the schools, but it was like what we went through. And

some of the other activities that I spoke to you about desegregating Asheville itself. We

were able to come up with a plan that was designed to and expected to bring about real,

lasting desegregation. But in Asheville, like in most places in the South, desegregation didn't

last long. It lasted as long as the white power structure and the white community allowed it

to last. But it came to an end in the way that things come to an end without having an end

declared. It just sort of segues back into what we hoped to change and what we had hoped to

accomplish, and never did, was the full desegregation of it, where at some point the

desegregated education and when I talk about a desegregated education, I'm simply talking

about an equal education where all of the students could feel that they in fact got the same

education as every other student got and that they were not limited and affected in any way

by the desegregated school system that we started from. [01:32:33] We're still working on

that and maybe one day we'll get that. So, in any event, I had the gratification of having tried

to desegregate schools when the schools were fully segregated, but we never completed it.

And although I went from the eighth grade to graduation in the Asheville city school system

thinking that I would one day experience the desegregation of Asheville students, I never

39

did. But I did have the gratification of trying to bring about that desegregation for those who

came after me, Black and white, who both had the promise of a desegregated education.

And the sad reality is that in Asheville, as in Charlotte and most other places, that reality

never really came to fruition because no longer, no sooner than we had entered into a

desegregation plan for Asheville, we saw eventually the schools basically resegregate and

never fully achieve the desegregated school system that we had hoped for. Likewise, in

Charlotte, which went through even greater lengths to try to bring about the desegregation of

the schools. And by that, I mean Charlotte in 1970, [19]71, whenever it was that Judge

McMillan ended his order calling for desegregation of every school in Charlotte along the

lines of the numbers in the population as a whole, that every school is supposed to be 60:40,

white to Black, teachers 60:40, or something similar. [01:34:36] And the desegregation of

teachers only lasted for a second or two. No sooner than it went into place, the schools had

already begun to desegregate. So that now when you look at the Charlotte school system,

where my godchild is a student at West Charlotte today, West Charlotte is almost a

completely Black high school. And you look at all the other schools and likewise you find

out that the desegregation that started in 1970 never really came to fruition and still isn't

there today. And I cannot mention the Charlotte, the Swann v. Mecklenburg school case

without also talking about the Capacchione case where a white child and, somewhere

around in the 1990s, I think maybe around 1999, filed a lawsuit claiming that she, this white

child, was not getting the education she was supposed to get because she wanted to go to a

school, I can't remember all the details of it, but in any event, that was the beginning, the

official beginning of the resegregation of schools in Charlotte. And now that process sadly

and unfortunately has almost been completed, so that if you're a Black child or a white child

40

in Charlotte, you may get a desegregated education, but you're just as likely not to because

we've experienced the fullness of resegregation of the schools in Charlotte, Mecklenburg,

but not just Charlotte-Mecklenburg, but all over the South. We see desegregation orders

being lifted under the guise of the schools being segregated and no longer, under the guise

of schools being desegregated and no longer segregated. And we find out that's actually not

the reality.

MHP: [01:36:48] Tell me a little bit more, because you smoothly segue from the

Asheville case, right, into the Swann case, the Charlotte case, because we're talking about

this happening all over North Carolina and the South.

JF: All over the South.