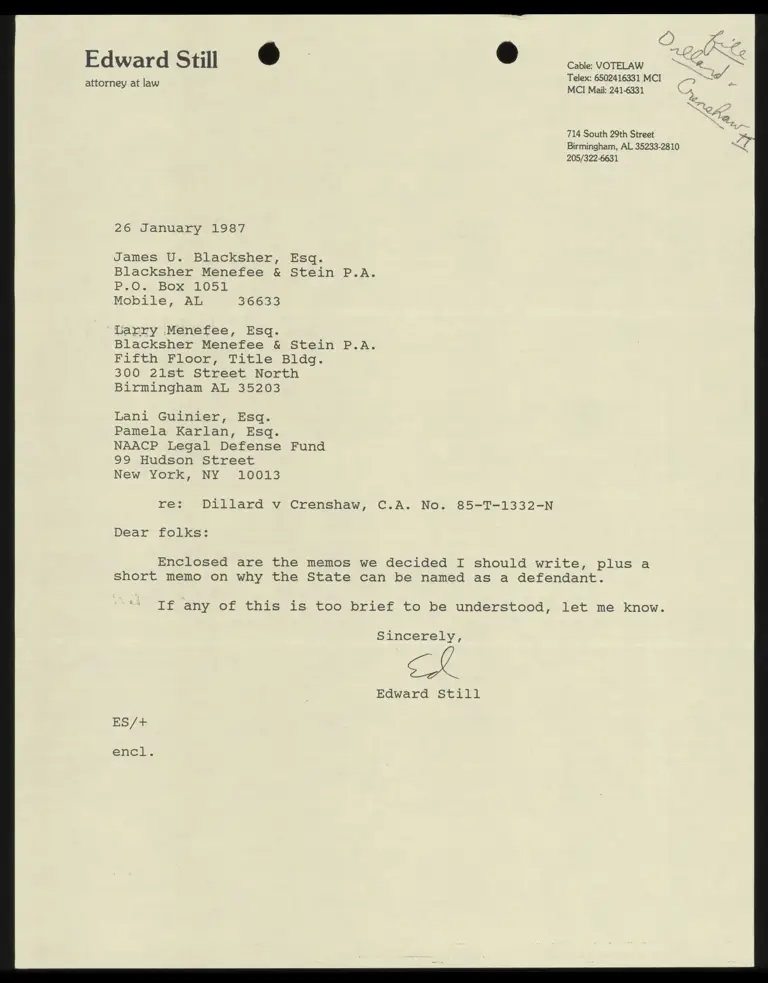

Correspondence and Memos from Still to Blacksher, Menefee, and Guinier

Working File

January 26, 1987

7 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Correspondence and Memos from Still to Blacksher, Menefee, and Guinier, 1987. 0139b1b3-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a42b04d9-0fd1-43b8-b94a-b46aa9f9e59f/correspondence-and-memos-from-still-to-blacksher-menefee-and-guinier. Accessed February 16, 2026.

Copied!

Edward Still %

attorney at law

26 January 1987

James U. Blacksher, Esq.

Blacksher Menefee & Stein P.A.

P.O. Box 1051

Mobile, AL 36633

"Larry Menefee, Esq.

Blacksher Menefee & Stein P.A.

Pifth Floor, Title Bldg.

300 21st Street North

Birmingham AL 35203

Lani Guinier, Esq.

Pamela Karlan, Esq.

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

re: Dillard v Crenshaw, C.A. No. 85-T-1332-N

Dear folks:

Cable: VOTELAW

Telex: 6502416331 MCI

MCI Mail: 241-6331

714 South 29th Street

Birmingham, AL 35233-2810

205/322-6631

Enclosed are the memos we decided I should write, plus a

short memo on why the State can be named as a defendant.

If any of this is too brief to be understood, let me know.

Sincerely,

Edward Still

ES/+

encl.

Edward Still

attorney at law

Cable: VOTELAW

Telex: 6502416331 MCI

MCI Mail: 241-6331

714 South 29th Street

Birmingham, AL 35233-2810

205/322-6631

Memo

ADC as ”class” representative

23 January 1987

Edward Still

STATEMENT FOR THE MOTION

The Alabama Democratic Conference (ADC) is a political

organization composed primarily of black Alabama voters in nearly

every county of the state. Its purposes include the elimination

of barriers to full participation by blacks in the political

processes in Alabama and the nation.

STATEMENT FOR THE MEMO

The plaintiffs seek to add the Alabama Democratic Conference

(ADC) as a party plaintiff. The ADC will act as the

representative of its members who reside in the counties or

municipalities which will be affected by the Motion for

Additional Relief. The ADC meets the three-part test for such

representation set out in Hunt v Washington Apple Advertising

Comm’n, 432 US 333, 343 (1977):

[A]n association has standing to bring suit on behalf of its

members when: (a) its members would otherwise have standing

to sue in their own right; (b) the interests it seeks to

protect are germane to the organization’s purpose; and (c)

neither the claim asserted not the relief requested requires

the participation of individual members in the lawsuit.

Members of the ADC (black voters) could bring this action -- and,

in fact, many of the original plaintiffs in this suit were

members of the ADC. As noted in the Motion, one of the ADC’s

purposes is the elimination of barriers to full participation by

blacks in the political process. Finally, there is no need for

the individual members of the ADC to participate as plaintiffs;

the claim the plaintiffs bring is not a personal one, but one

which will inure to the benefit of all black voters in the

particular governmental unit. To the extent there are any

questions of fact to ke decided, they are entirely related to the

governments and their elections and not to any particular blacks.

To hold that individual black voters would have to be plaintiffs

would be to hold that some blacks might lose a dilution case

because of their personal characteristics or activities. We all

know that such matters are extraneous to dilution suits.

Memo

res judicata

23 January 1987

Edward Still

The State of Alabama should be bound by the findings

previously made by this Court on the issue of the intentionally

discriminatory nature of various election laws because the county

commissions which were the original defendants in this action had

a community of interest with the State and because the State was

aware of the issues in the earlier phase of this suit. “Under

the federal law of res judicata, a person may be bound by a

judgment even though not a party if one of the parties to the

suit is so closely aligned with his interests as to be his

virtual representative. #*** The question whether a party’s

interests in a case are virtually representative of the interests

of a nonparty is one of fact for the trial court.” Aerojet-

General Corp. v Askew, 511 F24 710, (5th Cir 1975) (Dade

County bound by decision in earlier suit against State Board of

Education involving Board property on which County had a claim).

Examples of virtual representation include the following:

1. The United States has been precluded from

relitigating in federal court an issue lost by a state in state

court, since the two governments had cooperated in enforcement of

the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System, United

States v ITT Rayonier, Inc., 627 F2d 996 (9th Cir 1980).

2. The City of Winooski is bound by a prior

determination against the Vermont Public Service Board, its

codefendant, that the VPSB had no authority to regulate power

plants subject to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

Board of Elec. Light Comm’rs of Burlington v McCarren, 725 F2d

176 (24 Cir -1933).

The fact (which we should plead) that some of the counties

asked the Attorney General to come into the suit will reinforce

our point that the AG had actual knowledge of the suit.

There are suits which reject the virtual representation

theory, usually on the facts. See Wright, Miller, & Cooper,

Federal Practice and Procedure Civil §4457 for further

discussion.

memo

State as defendant

26 January 1987

Edward Still

“Similarly, although Congress has power with respect to the

rights protected by the Fourteenth Amendment to abrogate the

Eleventh Amendment immunity, we have required an unequivocal

expression of congressional intent to ‘overturn the

constitutionally guaranteed immunity of the several States.’”

Pennhurst State School & Hospital v Halderman, 465 US 89, 99

(1984) (citations omitted).

In Atascadero State Hospital v Scanlon, 87 LEd2d 171 (1985),

the Supreme Court held that the Rehabilitation Act did not

contain an express abrogation. The only words in the statute

that would have made the State liable were “any program or

activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

In contrast, Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act now provides

as follows: “No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting

or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied

by any state or political subdivision in a manner ....”

It appears to me that the State of Alabama can be sued

directly, rather than through its officials, in a Section 2 suit.