English v. Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Company Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant

Public Court Documents

December 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. English v. Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Company Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant, 1971. fcb464db-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a431893b-d090-41f5-9184-af38a66998ae/english-v-seaboard-coast-line-railroad-company-brief-for-plaintiff-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

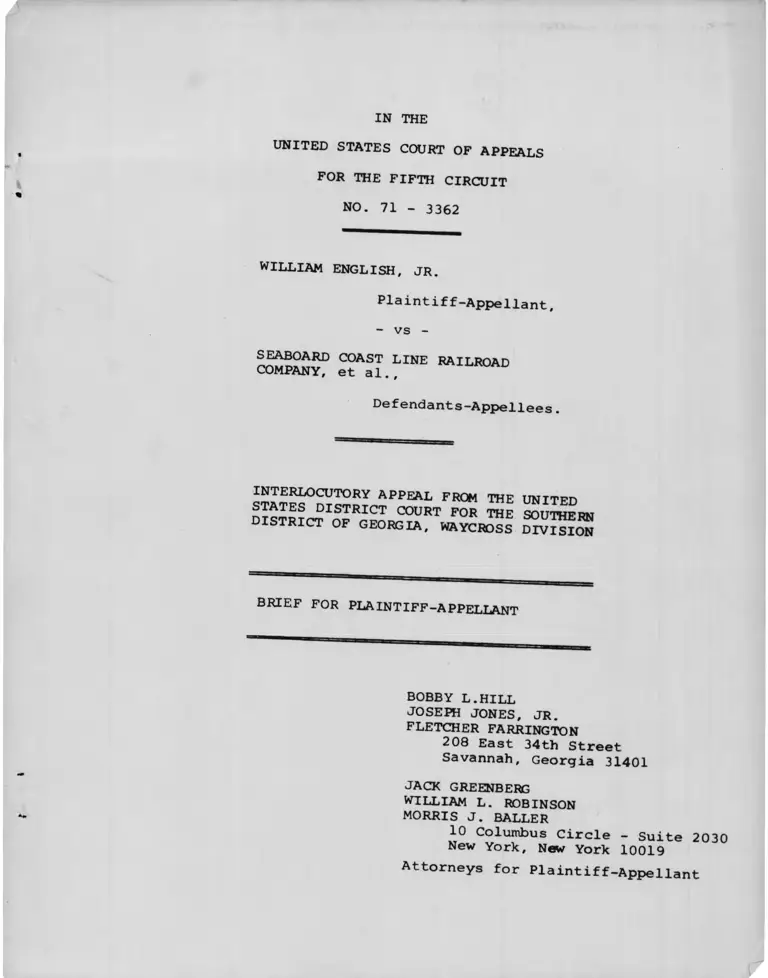

IN THE

, UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 71 - 3362

WILLIAM ENGLISH, JR.

Plaintiff-Appellant,

- vs -

COAST LINE railroadCOMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

INTERLOCUTORY APPEAL FROM THE UNITED

STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN

DISTRICT OF GEORGIA, WAYCR^S D“ S

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

BOBBY L.HILL

JOSEPH JONES, JR.

FLETCHER FARRINGTON

208 East 34th Street

Savannah, Georgia 31401

JACK GREENBERG

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

MORRIS J. BALLER

10 Columbus Circle - Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

I N D E X

Table of Authorities.............................. ^

Issue Presented for Review .......................... ±

Statement of the C a s e ........................ ^

Statement of Facts ............................ 5

Argument .................................... Q

Statutory and Factual Setting ................. 8

I. Individual White Employees Need No

Separate Representation of Their

Interests Because These Interests Are

Adequately Represented by the Present

Union Defendants............................ 10

A. Local 5 Adequately Represents The

Interests of the Individual White

Employees............................ 10

B. BRAC Adequately Represents The

Interests of the Individual White

Employees............................ 13

II. Individual White Employees Have Shown No

Rights or Legitimate Interests Worthy

of Separate Representation in this

Litigation.................................. 16

A. Individual White Employees Have No

Substantive Right to Oppose the

Alteration of a Discriminatory

Collective Bargaining Contract Which

Would Make Them Necessary or

Indispensable Parties ................ 16

B. Individual White Employees Have Ex

pressed No Interest in Participat

ing in This Litigation.............. 18

Conclusion.......................................... 20

Page

Certificate of Service . 21

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Banks v. Seaboard Coast Line Railroad

Company, ___ F.Supp. , 3 EPD *8059

(N.D. Ga. 1970) ....................

Bing v. Roadway Express, Inc., 444 F.2d 687

(5th Cir. 1971) ..................

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Company, 416 F.2d 711

(8th Cir. 1969) ......................

Central of Georgia Ry. v. Jones, 229 F.2d 648

(5th Cir. 1956), cert denied 352 U.S.

848 (1956). . . .~~7 . ........

Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41 (1957)

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Company, 421

F.2d 888 (5th Cir. 1970) ..................

Ford Motor Co. v. Huffman, 345 U.S. 330 (1953).

Haby v. Stanolind Oil and Gas Co., 225 F.2d

723 (5th Cir. 1955) ..........

Hayes v. Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Co.,

F-SuPP- ___,3 EPD *8170 (S.D. Ga. 1971) ........

Humphrey v. Moore, 375 U.S. 335 (1964)..........

Jenkins v. McKeithen, 395 U.S. 411 (1969)

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers

Union v. United States, 416 F.2d

980 (5th Cir. 1969)....................

McShan v. Sherrill, 283 F.2d 462 (9th Cir. 1960)

National Licorice Co. v. National Labor Relations

Board, 309 U.S. 350 (1940)..................

Neal v. System Board of Adjustment, 348 F.2d

722 (8th Cir. 1965)..............

Page

15

9

12, 14

17

5

19

17

9

12

17

5

9

9

17

12

l

CONT'D

Niles - Bement -Pond Co. v. Iron Moulders' Union,

254 U.S. 77 (1920)................................. 8

Norman v. Missouri Pacific Railroad, 414 F.2d

73 (8th Cir. 1969).................................. 17

Pellicer v. Brotherhood, 217 F.2d 205

(5th Cir. 1954)................................... ]_7

Provident Bank & Trust Co. v. Patterson, 390

U.S. 102 (1969)................................... 8> 9

Quarles v. Philip Morris Co., 279 F.Supp. 505

(E.D. Va. 1968)................................... 17

Shields v. Barrow, 17 How. 130 (1854) .................. 8

Stadin v. Union Electric Company, 390 F.2d

912 (3rd Cir. 1962) ........ .................... 19

Thompson v. New York Central Railroad Company, 250

F.Supp. 175 (S.D.N.Y. 1966).................... 12

Todd v. Joint Apprenticeship Committee, 223

F.Supp. 12 (N.D. 111. 1963).................... 12

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Company

F.2d ___, 3 EPD f8324 (5th Cir. August 24,

1971) .......................................... 7, 9, 11

United States v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railroad

Co., ___ F.Supp. ___, 3 FEP Cases 739

(E.D. Mo. 1971)................................ 15, 17

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International

Harvester, 427 F.2d 476 (7th Cir. 1970)........ 11, 12

Page

- ii -

CONT1D

STATUTES

Page

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII

42 U.S.C. §2000e ..................

42 U.S.C. §2000e-6 (b) ............

28 U.S.C. §1292 (b)..............

42 U.S.C. §1981 ................

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

Rule 19(a)........

Rule 24 . . . .

Advisory Committee Note to Rule

24(a) as amended, 39 F.R.P.

69 (1966) ............

3A Moore's Federal Practice (1966 ed.)

119.10 ............

- 1 X 1 -

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 71 - 3362

WILLIAM ENGLISH, JR.,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

- vs -

SEABOARD COAST LINE RAILROAD

COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

ISSUE PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Whether, in a Title VII suit seeking to alter a

racially discriminatory seniority system, individual white

employees whose relative seniority position might be affected

by the decree must be joined as parties defendant, despite the

presence as defendants of their segregated white local union

and its allegedly discriminatory parent union?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an interlocutory appeal from an order of the

United States District Court for the Southern District of

Georgia, entered September 7, 1971, staying this action pending

joinder of certain white individuals as parties defendant pur

suant to Rule 19(a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

1_/

(A. 201a-203a).

The heart of this action is an attack upon the seniority

system maintained by defendant Seaboard Coast Line Railroad

Company ("Seaboard") and defendants Brotherhood of Railway,

Airline,, and Steamship Clerks, Freight Handlers, Express and

Station Employees ("BRAC") and Local Number 5 thereof ("Local 5"),

2/which represent employees in the railroad's Waycross Division.

This attack centers on those provisions of the seniority system,

embodied in collective bargaining agreements between Seaboard

and BRAC, which plaintiff alleges have prevented or discouraged

black employees from gaining promotion or transfer into the

better, higher-paying jobs traditionally reserved for whites.

The case grows out of an EEOC charge of discrimination

filed by plaintiff William English, Jr., the appellant here,

on February 6, 1968 (A. 8a). The complaint was filed on

November 18, 1969, seeking relief from violations of Title

1/ This form of citation is to the Appellant's Appendix filed

with this brief.

2/ Local Number 1586 of BRAC was also joined as a defendant,

for reasons of jurisdictional completeness related to plaintiff’s

prayer for relief, including the merger of the separate,

segregated locals of BRAC. It is not alleged that Local 1586

discriminated against black employees.

2

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000ee_t seg..

and the duty of fair representation, as a class action on be

half of similarly situated black employees (A. 3a-lla). On

November 27, 1970 plaintiff moved to amend his complaint in

order to add a cause of action under 42 U.S.C. §1981, based

on the same facts as the Title VII action (A. 23a-32a); and

on June 19, 1971 plaintiff moved to amend the complaint further

to eliminate an error in terminology relating to the claim

for breach of the duty of fair representation (A. 43a-44a).

The District Court on August 17, 1971 allowed these amend

ments (A. 197a). Defendant Seaboard has filed an original

answer to the complaint (A. 12a-14a), an amended answer

(A. 21a-22a), and a second amended answer, in response to

both the original and the amended complaints (A. 15a-20a,

A. 25a-42a) . Extensive procedural and discovery litigation

has occurred in the court below.

The present appeal arises from a motion to dismiss for

failure to join indispensable parties, filed by Seaboard on

2/October 12, 1970. This motion urged, inter alia, that the

action must be dismissed in the absence of those white em

ployees whose relative seniority position might be adversely

3/ The motion itself is not included in the Record on Appeal.

However, its content is clear from the Court's Order of

September 7, 1971 (A. 201a).

3

affected by the decree plaintiff seeks. On August 17, 1971

the district court entered an order which defined plaintiff's

class to include "Negro employees of the Seaboard Coast Line

Railroad Company at or near Waycross, Georgia, who belong to

or are eligible for membership in either of the two defendant

locals of BRAC, Number 5 and Number 1586, by reason of job

classification" (A. 196a), but reserved decision on the re

levant portion of Seaboard's motion to dismiss (A. 197a). On

September 7, 1971 the district court denied the motion to dis

miss, but stayed the action

Until such time as the plaintiff files an amend

ment naming as defendant one or more of the white

employees included in said class [of potentially

affected employees], whereupon this Court will

pass an order pursuant to Rule 23(a) providing

for service upon said class to show cause why

they should not be joined as defendants.

(A. 203a). Implicit in the court's ruling was the holding

that such individual white employees are indispensable or

necessary parties to the action.

Plaintiff moved on September 18, 1971 to certify the

order of September 7, 1971 for interlocutory appeal pursuant

to 28 U.S.C. §1292(b) (A. 204a). The court's amended order

of September 18, 1971 certified the question for interlocutory

appeal (A. 205a-208a). On September 23, 1971 plaintiff timely

filed in this Court his petition for permission to appeal

under 28 U.S.C. §1292 (b) . This Court granted leave to file

the interlocutory appeal on November 9, 1971, and ordered

the appeal expedited (A. 211a).

4

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The complaint alleges an across-the board pattern of

discrimination by defendants against plaintiff and all other

similarly situated black employees at Waycross. It specifi

cally alleges that defendants' discriminatory practices in

clude "a racially segregated, dual system of jobs and lines

of progression" (A. 6a); restriction of blacks to inferior

jobs (IcL) ; unequal application of job requirements to blacks

seeking traditionally white jobs (_Id.) ; and a "lock-in" seniority

system which perpetuates racially identifiable dual job cat

egories (A. 7a). The complaint also alleges that the union

defendants maintain racially segregated local unions (Ld.);

and that BRAC and Local 5 breach their duty of fair repre

sentation toward black members of Local 1586, in that those

defendants participate or acquiesce in defendant Seaboard's

discriminatory practices through collective bargaining agree-

1/ments and otherwise (A. 8a). The complaint seeks declaratory

injunctive, and affirmative relief against all the practices

outlines above (A. 9a-lla). The defendants' various answers

deny all these substantive allegations.

4/ The district court was of course obliged to treat all the

foregoing allegations as true for purposes of ruling on the

motion to dismiss, Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41, 45-46 (1957);

Jenkins v. McKeithen, 395 U.S. 411, 421 (1969). The court below

apparently did so, and none of these facts are in dispute on

this interlocutory appeal.

5

All employess and job classifications pertinent to this

action are in Seaboard's Waycross Division and are within the

BRAC craft unit for collective bargaining purposes. All em

ployees and job classifications therein are divided into two

groups knows simply as Group 1 and Group 2, roughly corres

ponding to clerk's and laborer's jobs, respectively (A. 101a-

194a). Group 1 jobs are better and higher-paying than Group

2 jobs (A. 124a, 177a). All the blacks employed in Waycross

hold Group 2 jobs (A. 128a, 129a, 130a-131a, 135a, 157a);

all the Group 1 jobs are reserved for whites only (A. 130a-

131a, 157a); and the great majority of whites work in Group 1

5/jobs (A. 130a-131a). All the black employees are members of

Local 1586, theblack local (A. 180a); all the whites, whether

in Group 1 or Group 2, belong to Local 5, the white local

6/(A. 180a, 125a).

Promotion or transfer within the craft represented by

BRAC in Seaboard's Waycross Division is governed by the col

lective bargaining agreement in effect between defendants

5/ See also Defendant Seaboard's Answers to Plaintiff's Requests

for Admission, filed October 7, 1971, Nos. 8-12.

6/ There appears to be no dispute as to the fact that the

locals are each segregated. The record contains no direst ad

mission of this fact by defendant unions, however. Plaintiff's

interrogatories to BRAC and its locals, filed June 9, 1971,

sought to discover this information for the record, but the

unions have not yet seen fit to answer these interrogatories.

6

Seaboard and BRAC (A. 20a, 41a). Under this agreement, Group

1 seniority and Group 2 seniority are kept strictly separate

(A. 124a). In the event of permanent transfer or promotion

from Group 2 to Group 1, the transferred employee would carry

over none of his accrued Group 2 seniority for Group 1 pur

poses (A. 131a-132a). For purposes of promotion into Group 1,

or for bidding on jobs within Group 1, Group 2 seniority is

inapplicable (A. 109a, 173a). Since all blacks are in Group 2,

no blacks have any usable seniority rights for any Group 1 jobs.

Thus, whatever defendants' present state of mind regarding equal

employment opportunities, in fact their seniority system serves

effectively to lock blacks into the inferior jobs assigned to

them in keeping with present and past patterns of discrim

ination .

As relief, plaintiff seeks, inter alia, appropriate

modification of the existing seniority system (A.9a, 30a). Such

relief would no doubt include an order allowing qualified Group

2 employees to exercise their accrued seniority rights in apply

ing or bidding for transfer or promotion into Group 1 jobs

(A. 104a, 109a), possibly in competition with present white

VGroup 1 employees. It is these whites who are the object of

2/ Cf• United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Company. ___

F .2d ___, 3 EPD f8324 (5th Cir., August 31, 1971). That case

involved identical issues and some of the same defendants as the

present action. The relief there granted with respect to the

defendants' seniority/transfer system is similar to what

plaintiff seeks here.

7

Seaboard's solicitude, and whom the court below has deemed

indispensable or necessary parties.

ARGUMENT

Statutory and Factual Setting

This appeal involves application of Rule 19(a) of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 28 U.S.C., to the facts, of

v 8/

the present action. That rule provides, in relevant part.

Persons to be joined if feasible. A

person who is subject to service of pro

cess and whose joinder will not deprive

the court of jurisdiction over the sub

ject matter of the action shall be joined

as a party in the action if (1) in his

absence complete relief cannot be accorded

among those already parties, or (2) he

claims an interest relating to the sub

ject of the action and is so situated that

the disposition of the action in his

absence may (i) as a practical matter im

pair or impede his ability to protect

that interest or (ii) leave any of the

persons already parties subject to a sub

stantial risk of incurring double, mul

tiple, or otherwise inconsistent obliga

tions by reason of his claimed interest.

On the facts of this action, only subsection 2(i)

of Rule 19(a) is germane, as inspection of the pleadings

quickly shows. The only relief sought by plaintiffs which

8/ The definition in principle of who is a "person to be

joined if feasible" under Rule 19(a), or an "indispensable

party", is and long has been clear. See, e.g.. Provident

Bank & Trust Co., v. Patterson, 390 U.S. 102, 124-125 (1969),

and Shields v. Barrow, 17 How. 130, 139 (1854). Application’

of that definition to specific persons has always been the

problem, see Niles-Bement-Pond Co. v. Iron Moulders' Union

254 U.S. 77, 80 (1920). “ ---

8

would in any way affect the interests of the individual white

employees is an injunction and affirmative relief against the

discriminatory aspects of the job classification and seniority

systems in effect on Seaboard's Waycross Division. The collec

tive bargaining agreement in effect between defendants BRAC

and Seaboard embodies all pertinent provisions relating to

these seniority and job classification agreements. Individual

white employees are not parties to this collective bargaining

agreement. if the court, having all parties to the agreement

before it, decided to enjoin and modify the agreement's terms,

the court would be able to accord "complete relief . . . among

those already parties." Therefore subsection (1) is in

applicable here. For the same factual reason, e.g., presence

before the court of all parties to the bargaining agreement,

subsection 2 (11) is likewise inapplicable here. ^This argu-

u°*rt haf not hesitated to decree "complete relief" including substantial revisions of discriminatory seniority pro

visions of collective bargaining agreements, in cases where only

the company and unions were parties. See, e.g., Local 189 United

3lferT ^ y S r d PaPer^ kers v- United States. 41~F.2d 980 ^5th

?Q7i’/ 9T6T9-Z tryg Roadvay Express, Inc.. 444 F.2d 687 (5th Cir.■3 n ?.tates v• Jacksonville Terminal Co., F.2d

EPD 58324 (5th Cir. 1971). The Court must be presumed to have

done so in full knowledge that, if parties indispensable to a

such relief were absent, the Court should have raised the Rule 19 issue sua sponte. Provide.nt Bank & Trust Co v

|||terson 390 U-S. 102^U0-111 (1969) , Habv v. on

C?’' 225 F*2d 723 (5th Cir. 1955); McShan v. Sherrill 283 F ?d 462 -464 (9th Cir. 1960). The Title V I ~ a'ses cited in thie note

would therefore appear to lend sub silentio support to ampllant-'c position in this b r i e f . ------------^ s

10/ Even if the appellees choose to argue their point under sub

sections (a) (1) or fc)(2) (ii), we submit that the substance of our

argument herein is also applicable and persuasive with respect

to those other subsections.

9

ment will consequently deal with the issue raised here pri

marily in terms of Rule 19(a)(2)(i): whether disposition of

this action in the absence of the individual white employees

would, as a practical matter, endanger their ability to protect

their interests.

I* Individual White Employees Need No Separate

Representation of Their Interests Because

These Interests Are Adequately Represented

by the Present Union Defendants.

In deciding the Rule 19 motion, the district court did

not specify whether it had separately considered the adequacy

of the white clerks' representation through Local 5, BRAC, or

both. While the court's clearly implied negative answers to

these various questions present slightly distinct issues for

appeal, we urge that the district court erred in its ruling

based on any of the possible grounds.

The individual white employees whose interests are pur

portedly at stake here are all members of Local 5 and therefore

of BRAC. These union defendants are committed by duty and pre

ference to defending these employees' interests,as the record

abundantly demonstrates. They adequately represent their white

members in this action. Separate representation would there

fore be doubly redundant.

A. Local 5 Adequately Represents the Interests

of the Individual White Employees.

10

The most crucial fact on this appeal is the presence

of Local 5, a concededly all-white union whose membership is

limited to those employees who might be affected by the re

lief plaintiff seeks, as a party defendant. This defendant

is duty-bound under its duty of fair representation toward

those members to protect and defend their rights. Moreover,

"as a practical matter" in an industry where seniority posi

tions are fiercely defended and crucially important, see United

States v. Jacksonville Terminal Company, ___ F.2d ___, 3 EPD

18224 (5th Cir. 1971) at pp. 6993-146,-147, Local 5's vigorous

representation of its members' seniority positions is assured.

This same issue has been considered by a number of

cases, none of them controlling in this Court, but all of

which support plaintiff's view. The Court of Appeals for the

Seventh Circuit has squarely endorsed the position plaintiff

takes here in Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International

Harvester, 427 F.2d 476 (1970). That action was a Title VII

and §1981 race discrimination suit against a Company and local

union, the Bricklayers Local 21. The court assumed Local 21,

having systematically excluded blacks from membership, to be

all-white,427 F.2d at 479-480. The district court under Rule

19(a) had nevertheless held the individual bricklayers to be

indispensable parties to the action, 427 F.2d at 481. The

Court of Appeals reversed. Although for other reasons the

11

Court of Appeals did not reach the Rule 19 question in its

ratio decidendi, it stated bluntly:

Local 21 adequately represents the

interests of absent bricklayers thereby re

futing the argument that individual white

bricklayers are indispensable parties.

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Company, 416

F.2d 711, 719 (7th Cir. 1969).

427 F.2d at 489 n. 22. In another discrimination case against a

raii:r‘03b and international and local local unions relating to

seniority rights, Thompson v. New York Central Railroad Company.

2 50 F.Supp. 175 (S . D .N. Y. 1966), the court denied a Rule 19 motion

to dismiss for failure to join individual union members as

defendants, stating,

The Local represents the employees as a class. It

made the very determination of which plaintiffs com

plain. In the absence of a showing that the benefited

employees' interests are not the same as defendant

Union s the motion to bring in the employees as indis

pensable parties is denied.

250 F.Supp. at 178. And in Todd v. Joint Apprenticeship Com-

m_it_teê , 223 F.Supp. 12, 17-18 (N.D. 111. 1963) the court, on

facts closely similar to those presented here, strongly rejected

the same proposition that Seaboard urged below.

In only one reported decision known to plaintiff's

counsel, Hayes v. Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Co.. 3 EPD

18170 ( s.D. Ga. 1971), has a federal court found members of

a segregated white local union which was a party defendant

. . . 10a/to be necessary or indispensable parties to the action.

l°a/ Neal v. System Board of Adiustment, 348 F.2d 722 (8th Cir.

1965) [dictum] is not such a case, in that the segregated locals

there had been consolidated at the time of the decision. More

over, Neal is inapplicable here because it arose under the unique

provisions of the Railway Labor Act, cf. Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive

Company, at 719 n.9 (7th Cir. 1969). See also, Thompson v. New

York Central Railroad Co., supra.

12

That case was decided by the same court which decided and

11/certified the present question for appeal.

B. BRAC Adequately Represents the Interest of

the Individual White Employees.

Unlike its segregated white Waycross local, the

Brotherhood (BRAC) has interests which are not coterminous

with those of its white members in Waycross. Nevertheless,

the record makes it clear that BRAC has chosen in this pro

ceeding to represent only those individual whites' interests,

and leaves little doubt that it views its obligation with re

spect to the seniority system here in question as the unbend

ing defense of the status quo.

Whatever BRAC's theoretical duty to represent black

members fairly, it is clear that BRAC has utterly disregarded

blacks' interests. The complaint (here presumptively true)

alleges such a default of duty, and BRAC's posture through

out this litigation in which it has denied and resisted all

plaintiff's claims shows its alignment with white employees'

interests. Moreover, BRAC is party to the collective bar

gaining agreement which embodies the disputed system, and

has single-mindedly defended the validity of its contract

11/ Petition to file an interlocutory appeal on the same issue

in the Hayes matter was denied by this Court for want of juris

diction, 3 EPD f8320, on August 10, 1971.

13

as a bona-fide seniority agreement (A. 19a-20a, A. 41a). BRAC

plainly perceives its duty to include only the preservation

of the contractual system for perpetuating the enjoyment by

white employees of their discriminatory advantages. In this

light, BRAC is an adequate and independent representative of

the individual employees' interests.

The Seventh Circuit and most other courts confronted

with the question have approved the logic of plaintiff's

position. In Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Company, 416 F.2d

711 (1969), a sex-discrimination case against a company and

union, the court reversed a lower court's Rule 19 holding

that individual males were necessary parties to the suit.

The Court of Appeals said,

Colgate also argued that there was a

failure of necessary joinder in the actions

below as none of its male employees were

made parties to the action. The issue is

frivolous. The Union was made a party

and its duty was to represent the male em

ployees as well as the female employees.S/

There is nothing in the law which pre

cluded the Union from recognizing the in

justice done to a substantial minority of

its members and from moving to correct it.

416 F.2d at 719. Footnote 8 in that text contains another

highly relevant comment: "In fact, since a majority of

the Jeffersonville employees were male, it is not unreason

able to assume that the officers of the Union were elected

by a majority of male members and would, therefore, be re

sponsive to their interests." Id.* A similarly realistic

14

assessment of the situation in Waycross would show that BRAC

is wholly responsive to its white majority there. Accord:

States v. St. Louis —San Francisco Railroad Co. ,

F.Supp. ----, 3 FEP Cases 739, 741 (E.D. Mo. 1971), a race

discrimination case wherein the Court noted, "The Brother

hood is fully capable of representing the interests of its

members."

The only case on point which supports the Seaboard's

position in this regard is Banks v. Seaboard Coast Line Rail-

road_Co., ___ F.Supp. ___, 3 EPD 18059 (N.D. Ga. 1970), where

the Seaboard once again sought dismissal of a Title VII

claim for failure to join affected individual white em

ployees. In that case the international union (Brotherhood

Railway Carmen), but not the local, was a defendant. That

court's holding, on which the court below relied exclusively

12/

in ruling on the matter sub ludice. was based on its per

ception that

The Brotherhood has an equal duty to

represent those members comprising the

cases which plaintiff represents as well

as the white employees whose interest

would be realigned by any other grant

ing relief to plaintiff. it thus appears

that the white employees' interest is not

the same as the Brotherhood's, and that

the Brotherhood cannot fairly and ade

quately represent the interest of the class.

12_/ A. 201a-203a. We think this reliance was misplaced, in

view of the crucial factual difference arising from the pre

sence of the local union defendant here.

15

. . . Here it seems clear that the

white employees whose interest will

be realigned should plaintiff prevail

are indispensable parties.

JEd. at p. 6161. This reasoning is, we submit, unpersuasive

in the instant case. Whatever the facts in Banks may have

indicated with respect to any differentiation between the

union's interests and those of its white members, here BRAC

has sufficiently demonstrated that its goals and the white

employees' goals are at once identical and hostile to those

of plaintiff and his class.

Individual white employees who might be affected by

a decree herein are already represented not once but twice

by vigorous defendants. Additional representation of such

employees could only be burdensome and redundant.

II. Individual White Employees Have Shown No

Rights or Legitimate Interests Worthy of

Separate Representation in This Litigation.

A. Individual White Employees Have No Substantive

Right to Oppose the Alteration of a Discrim

inatory Collective Bargaining Contract Which

Would Make Them Necessary or Indispensable

Parties.

The only rights" or interests of white employees here

in question are those individuals' seniority positions relative

to certain black individuals, for certain purposes. These

seniority "rights" based on a racially discriminatory seniority

16

system, like even legitimate seniority rights, "are not vested,

indefeasible rights. They are expectancies derived from the

collective bargaining agreement, and are subject to modification."

Quarles v. Philip Morris Co.. 279 F.Supp. 505, 520 (E.D. Va.

1968); Norman v. Missouri Pacific Railroad, 414 F.2d 73, 85 (8th

Cir. 1969); United States v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railroad

Co., supra, at 741; cf. Humphrey v. Moore. 375 U.S. 335 (1964);

Ford Motor Co. v. Huffman. 345 U.S. 330 (1953); Pellicer v.

Brotherhood. 217 F.2d 205 (5th Cir. 1954); Central of Georgia

Ry. v. Jones. 229 F.2d 648 (5th Cir. 1956), cert, denied 352

U.S. 848 (1956). Such modification could in principle occur

through normal collective bargaining processes, to which only

Seaboard and BRAC would be parties; individual white employees

would not participate directly, but would be represented and

bound by their union. Since the parties adamantly refuse to

modify their contract, however, this matter must proceed in

federal court. When the court performs this function of

modifying the bargaining agreement, there is no more need for

individual white employees to be represented in the litigation

than there would be for their personal presence at collective

bargaining sessions. Our position, in short, has been aptly

summarized by Professor Moore: "Public rights may be vindicated,

although they run counter to contractual rights between the

defendant and third persons, without having the latter before

the court." 3A Moore's Federal Practice 1(19.10, p. 2344; National

Licorice Co. v. National Labor Relations Board. 309 U.S. 350

(1940) .

17

B. Individual White Employees Have Expressed

No Interest in Participating in This Liti

gation .

Individual white employees have been formally notified

of the pendency of this action by service upon officers of

their white local union of EEOC charges and legal process. In

addition, it is highly probable that this action has achieved

notoriety among Waycross employees through informal channels.

Nevertheless, not a single white employee has raised his voice

to seek separate representation by means of intervention pur

suant to Rule 24, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Yet it

is clear under Rule 24 that a white employee would be "entitled

to intervene in an action when his position is comparable to

that of a person under Rule 19(a)(2)(i), as amended, unless

his interest is already adequately represented in the action

by existing parties." Advisory Committee's Note to Rule 24(a)

as amended, 39 F.R.D. 69, 110 (1966). The absence of any

such motion to intervene in the case seriously undermines the

credibility of defendant's proposition that defendant unions

11/do not now adequately represent the white employees' interests.

1.3/ Even upon motion to intervene, we submit that the part

icipation of individual white employees may be open to serious

doubt. However, the propriety of their joinder would be less

dubious there, where movants would presumably assert that their

interests are not adequately represented, than on the actual

record barren of any such indication.

18

The fact that the issue of white employees' participation

arises in the context of Seaboard's motion to dismiss under

Rule 19(a) puts this question into a context very different

from that of Rule 24. The Seaboard is, of course, the one

defendant whose interests are fundamentally different from

those of its white employees. Despite the fact that Seaboard

is in no way prejudiced by the absence of these employees from

the litigation, it alone and perhaps paradoxically insisted

on raising the issue below.

In view of the foregoing argument showing that in

dividual white clerks are in no legitimate sense needed in

this litigation, the addition of these superfluous parties

can only have the effect of complicating and prolonging this

litigation. "Additional parties always take additional time.

Even if they have no witnesses of their own, they are the

source of additional questions, objections, briefs, arguments,

motions and the like which tend to make the proceeding a

Donnybrook Fair.'" Stadin v. Union Electric Company, 309

F.2d 912, 920 (3rd Cir. 1962). Such needless encumbrance of

the proceedings would be contrary to this Court's recognition

of 'the duty of the courts to make sure the Act works,"

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Company, 421 F.2d 888, 891 (5th

Cir. 1970). The Act itself directs courts in the case of

Attorney General pattern and practice suits "to assign the

case for hearing at the earliest practicable date and to cause

19

the case to be in every way expedited," 42 U.S.C. §2000e-6(b).

The courts should be no less diligent in facilitating prompt

hearing of private class actions which are directed at pro

viding a remedy for the same underlying problems as the

Attorney General suits. The unnecessary addition of more

defendants in this action would cut against all these policies.

CONCLUSION

The district court's order requiring joinder of the

individual white clerks as defendants was without justification

and virtually without precedent. The white employees in

question are already adequately represented in this proceed

ing both by defendant Local 5 and by defendant BRAC. This

Court should therefore vacate the district court's order

staying this action.

Respectfully submitted.

BOBBY L. HILL

JOSEPH JONES, JR.

FLETCHER FARRINGTON

208 East Thirty-Fourth Street

Savannah, Georgia 31401

JACK GREENBERG

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

MORRIS J. BALLER

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

_2C

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that I have served a copy

of the foregoing Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant upon Malcolm

Maclean, Esq., Post Office Box 9848, Savannah, Georgia 31402;

James L. Highsaw, Esq., 1015 18th Street, N.W., Washington,

D.C. 20036; Stanley M. Karsman, Esq., Ill West Congress Street,

Savannah, Georgia 31402 attorneys for defendants by placing

same in the United States mail, adequate postage prepaid

this ____ day of December, 1971.

Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellant