United Steelworkers of America (AFL-CIO-CLC) v. Weber Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 31, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United Steelworkers of America (AFL-CIO-CLC) v. Weber Brief Amici Curiae, 1979. a244b4e2-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a436e922-1a20-42aa-8f12-76f75283a74a/united-steelworkers-of-america-afl-cio-clc-v-weber-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

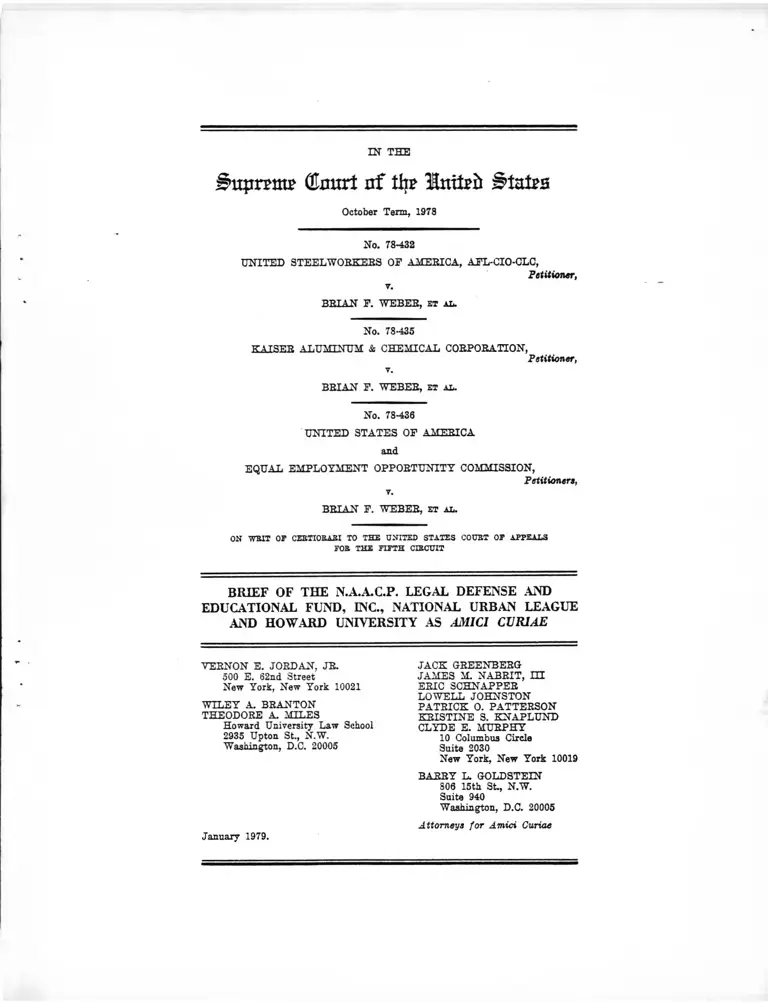

IN THE

J^upronp GIxmrt nf th? Inifrb Stairs

October Term, 1978

No. 78-432

UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA, AFL-CIO-CLC,

Petitioner,

v.

BRIAN F. WEBER, et al.

No. 78-435

RAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL CORPORATION,

Petitioner,

v.

BRIAN F. WEBER, et al.

No. 78-436

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

and

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION,

Petitioners,

y.

BRIAN F. WEBER, et al.

ON WHIT OF CEBTIOEABI TO THE UNITED STATES COUET OF APPEALS

FOE THE FIFTH CIECUIT

BRIEF OF THE N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., NATIONAL URBAN LEAGUE

AND HOWARD UNIVERSITY AS AMICI CURIAE

VERNON E. JORDAN, JR.

500 E. 62nd Street

New York, New York 10021

W ILEY A. BRANTON

THEODORE A. MILES

Howard University Law School

2935 Upton St., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES H. NABRIT, H I

ERIC 3CHNAPPER

LOWELL JOHNSTON

PATRICK O. PATTERSON

KRISTINE S. KNAPLUND

CLYDE E. MURPHY

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

S06 15th St, N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

January 1979.

INDEX

Page

Table o f Authorities ................................. :............. i i i

Interest o f Amici ............ ....................................... 1

Summary o f Argument .................................................. 6

ARGUMENT

I. T itle VII Permits Employers and

Unions to Take Voluntary Race-

Conscious Affirm ative Action ............... 9

A. Legislative History: 1964 . . . . 9

3. Judicial and Executive

Interpretation: 1964-1972 . . . . 18

C. Legislative History: 1972 . . . . 21

D. EEOC Guidelines on Affirm ative

Action .............................................. 24

II . A Standard Permitting Employers

and Unions to Take Race—Conscious

Affirmative Action When They Have

a Reasonable 3asis To Do So Is

Consistent with T itle VII and the

Constitution ............................................. 23

A. An Employer or Union May

Take Race-Conscious Affirma

tive Action Where It Acts Upon

a Reasonable B elie f that Such

Action Is Appropriate .................. 28

B. An Action to Enforce Che Fifth

C ircu it 's Construction of

T it le VII Would. Not Present

a ’’Case or Controversy” ............... 41

C. The Fifth C ircuit Has Given

T itle VII an Unconstitutional

Construction ........................................ 49

III . This Affirm ative Action Plan Is

Permissible Under T itle V II................. 56

A. The Plan Was Properly

Instituted ....................................... 56

1. Kaiser's Prior Discrimina

tion .............................................. 58

2. M odification o f Kaiser's

Present Practices ................... 83

3. General Discrimination in

the Training and Development

of Craft Workers ..................... 89

4. Compliance with the

Executive Order ........................104

3. The Plan Was Properly

Designed ......................................... 107

1. The Plan ................................... 107

2. The Standard and Its

Application ............................... 112

CONCLUSION ................................................................... 122

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Adams v. Richardson, 351 F.Supp.

Cases:

PAGE

636-(D.D.C. 1972) ................................. 95

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975) ........................... passim

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.,

415 U.S. 36 (1974) ............................. 12,30

Associated General Contractors of

Mass., Inc. v. Altshuler,

361 F.Suop. 1293 (D.

Mass. 1973), a f f ’ d , 490 F.2d 9

(1st C ir .19 73 ) , c e r t . d en ied ,

416 U.S. 957 (1974) ............................. 107,115

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186

(1962) .............. 43

Barlow v. C ollins, 397 U.S.

159 ( 1970) ............................................. 44

Beaunamais v. I l l in o is , 343 U.S.'

250 (1952) ............................................. 62

3ollin g v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497

(1954) ...................................................... 50

Boston Chapter, N .A .A .C .P ., Inc., v .

Beecher, 504 F.2d 1017 (1st

Cir. 1974), c e r t . denied, 421 U.S.

910 (1975) ............................................. 23,114

- iii —

j

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

♦ - __

Bridgeport Guardians, I n c . v . .

Bridgeport C iv il Service

Commission, 482 F.2d 1333

(2nd C ir. 1973), c e r t , denied,

421 U.S. 991 ( 1975) ........................... 115

3rown v. Board o f Education, 347

U.S. 438 (1954) ................................... 93

BurrelL v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical

Corp., Civ. Action Ho. 67-86

(M.D. La. Feb. 24, 1975)(concent

decree) ................................................. 33

3urrell v. Kaiser Aluminum &

Chemical Corp., 408 F.2d

339 (5th Cir. 1969), r e v 'g , 287

F.Supp. 289- (E.D. La. 1968) ............. 33

Carey v. Piohus, 55 L.Ed.2d 252

(1978)’ ...................................................... 49

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 432

(1977) ............................................ 74>76

Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S.

340 (1976) ............................................. 34

Chicago, e tc . R.R. v . Wellman, 143

U.S. 339 (1892) ................................... 47

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v.

Local 542, Operating Engineers,

C ivil Action Ho. 71-2698 (E.D.

Pa. Hov. 30, 1978) ............................. 39

Cases:

PAGE

- iv -

Cases:

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

'PAGE

Contractors A ssociation o f Eastern Penn

sylvania v . Secretary

of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3rd C ir .) ,

c e r t , denied, 404 U.S. 854

(1971) ..................................................... 21,107

Crockett v. Green, 534 F.2d 715

(7th Cir. 1976) ................................... 115

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321

(1977) .....................................................

EEOC v. A.T.& T. Co., 556 F.2d

167 (3rd Cir. 1977), cert, denied,

57 L.Ed.2d 1161 (1978) .....................

EEOC v. Detroit Edison Co., 515

F.2d 301 (6th Cir. 1975), vac'd

and rent'd on other grounds, 431

U.S. 951 ( 1977) ................................... 115

Emporium Capwell Co. v. Western

Addition Community Organi

zation, 420 U.S. 50 ( 1975) . . . ___ 120

Erie Human Relations Commission

v. T u llio , 493 F .2d 371

(3rd Cir. 1974) ................................... 115

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976) ........................... 2, 17,49,120

Fumco Construction Corp. v.

Waters, 57 L .Ed.2d 957 ( 1978)........ 81

36,64, 72,

80, 83

115

j

Gascon County v. United Statesy

395 U.S. 285 (1969) ........................... 54, 55

General E lectric Co. v. G ilbert,

429 U.S/ 125 (1976) ........................... 26

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.

U.S. 424 (1971) ............................. . . . passim

Hazelwood School D istrict v. United

States, 433 U.S..299

(19 7 7) ...... ...............................................36 , 65 , 71,76

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475

(1954) ....................................................... 50

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385

(1969) ........................................................ 50,51

International Brotherhood of

Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 ( 1977) . . ' ....................... 36,48 , 65 , 71

James v. Stockham Valves and

Fittings Co., 559 F.2d

310 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied,

434 U.S. 1034 (1978) .......................... 99

Keyes v. School D istrict No. 1,

413 U.S. 189 (1973) ............................ 62

Local 53, Asbestos Workers v.

Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047

(5th Cir. 1969) .................................... 18

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

'PAGE

- vi -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Lord v. Veazie, 8 How. 251

(1850) ............ ^

Marchetti v. United States, 390

U.S. 39 (1968) ..................................... ^

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S.

39 ( 1971) ............................................... 32

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 ( 1973) ........................... 11,34

Moore v. East Cleveland, 431 U.S.

494 (1977) ............................... ' ............. 62

Moose Lodge No. 197 v. Irv is ,

407 U.S. 163 ( 1972) ........................... 54

Morrow v. C risler , 491 F.2d 1053

(5th C ir .) (en banc), cert, denied,

419 U.S. 895 ( 1974) ............................. H5

N.A.A.C.P. v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th

Cir. 1974) ............................................. 115

N.A.A.C.P. v. 3utton, 371 U.S. 415

(1963) ...................................................... 55

National League of C ities v.

Usery, 426 U.S. 833 (1976) ............... 55

NLRB v. Jones.St Laughlin Steel Corp.,

301 U.S. 1 ( 1937) .................................

Cases:

PAGE

- vii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

North Carolina State Board o f

Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43

(1971) ..................................................... 49,51

Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum 4 Chemical

Corp., 575 F.2d 1374 (5th Cir.

1978) ........................................................ 32,71,79

Pettway v. American Cast Iron PiDe Co.,

494 F .2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974 ) ___ 99

Railway Mail Association v. Corsi,

326 U.S. 88 (1945) ........................... 51

Regents o f the University o f

C alifornia v. 3akke,

57 L.Ed.2d 750 (1978) ......................... passim

Rios v. Enterprise Association

Steamfitters Local 638, 501

F.2d 622 (2d Cir. 1974) ...................... 115

Robinson v. Union Carbide Corn.,

538 F.2d 652 (5th C ir. 1976) ........ 100

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973) ........ 62

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457

F.2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972) ................. 81

Sierra Club v. Morton, 405

U.S. 727 (1972) .................................. 44

Cases:

PAGE

- viii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Simon v. Eastern Kentucky Welfare

Rights Organization, 426 U.S.

26 (1976) ............................................... 45

Sims v. Local 65, Sheet Metal Workers,

459 F .2d 1023 (6th C ir. 1973) ___ 115

Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 323 U.S.

134 (1944) ............................................. 26

Southern I l l in o is Builders Association

v. O gilvie, 471 F.2d 680 (7th

Cir. 1972) ............................................. 21,115

Stevenson v. International Paoer C o .,

516 F .2d 103 (5th Cir. 1975) ........ 100

Swift & Co. v. Hocking Valley R.R.

Co., 243 U.S. 281 (1917.) ............... 46

United Jewish Organizations v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977)................. 105

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum

Industries, In c ., 517 F.2d

826 (5th C ir .1975), cert, denied,

425 U.S 944 (1976) ............................. 116

United States v. Allegheny-

Ludlum Industries, In c .,

63 F.R.D. 1 (N.D. Ala. 1973) ........ 117

United States v. Bethlehem Steel

Coro., 446 F.2d 652 (2nd Cir.

1971) ........................................................ '100

United States v. Carolene

Products Co., 304 U.S. 144 (1938) . 62

Cases:

PAGE

- ix -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

-------- PAGS

United States v. C ity o f Chicago,'

549 F .2d 415 (7th Cir. 1977),

ce rt- denied, 434 U.S, 875

(1978) .......... -......................................... 115

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86,

315 F.Supp. 1202 (W.D. Wash. 1970),

a ff*d , 443 F .2d 544 (9th C ir .) ,

cart, denied, 404 U.S 984 (1971).. L9

United States v. Johnson, 319 U.S.

302 (1943) ............................................. 47 ,4S

United States v. Local 38, IBEW, 428

F.2d 144 (6th C ir .) , c e r t , denied

400 U.S. 943 (1970) ........................... 18

United States v. Local 212, IBEW, 472

F.2d 634 (6th Cir. 1973) ................ 23,115

United States v. Masonry Contractors

Association, 497 F.2d 871 (6tn

. . Cir. 1974) ............................................. 115

United States v. N.L. Industries, In c.,

479 F .2d 354 (8th Cir. 1973) ........... 12,115

United States v. Sheet Mecal Workers

Local 36, 416 F.2d 123 (8th

Cir. 1969) ............................................. 19

United States v. Wood Lathers Local

46, 471 F.2d 408 (2d C ir .) ,

cart, denied, 412 U.S. 939

(1973) ..................................................... 19,115

United Steelworkers of America v.

American Manufacturing Co.,

363 U.S. 564 (1960) ............................. 119

- x -

Tags

V illage o f Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Develop

ment Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1972) . . . 88

Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490

(1975) ........................................................ 45

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229

(1976) ........................................................ 88

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530

F.2d 1159 (5th C ir .) , cart, denied,

429 U.S. 861 (1976) ............................. 72

Constitutional Provisions, Statutes,

Executive Orders and Regulations:

United States Constitution, Fifth

Amendment .................................................. 50

United States Constitution,

Fourteenth Amendment ........................... 51,52,54

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972, Pub. L. No. 92-261 ................... 21

Fugitive Slave Act, 121 Stat.

462, §7 ...................................................... 52

42 U.S.C.- §2000e, et seq. , T itle

VII o f the C iv il Rights Act

of 1964 ............................................. passim

La. Rev. Stat. Ann. §1996C ......................... 56

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

- x i -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE

Executive. Order No. 10,925, 3 C.F.R.

443 (1959-63 Comp.) . r ................. 106

Executive Order No. 11,246, 30 Fed.

Reg. 12319, as amended, 32

Fed. Reg. 14303..................................... passim

41 C.F.R. §60-2 (Revised Order

No. 4) ..................................................... 104-06

Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission, Uniform Guidelines on

Employee Selection Procedures,

43 Fed. Reg. 38290, 29 C.F.R.

Part 1607 (1978) ........................... . 28,85-86

Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission, Guidelines on Affirm ative

Action, 44 Fed. Reg. 4422,

29 C.F.R. Part 1608 (1979) ............ passim

Equal Employment Opportunity

Coordinating Council, Policy

Statement on Affirmative Action

Programs for State and Local

Government Agencies, 41 Fed.

Reg. 38814 (1976) ............................... 28

Executive Decisions and Opinions:

EEOC Decision 74-106, 10 FEP Cases

269 (A pril 2, 1974) ........................... 27

EEOC Decision 75-268, 10 FEP Cases 1502

(May 30, 1975) ..................................... 23

- x i i -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

O ffice o f Che S o lic ito r , U.S. Department

o f Labor, Legal Memorandum, in Hearings

on The Philadelphia Plan and S.931 Before

the Subcomm. on Separation o f Powers o f

the Senate Comm, on the Judiciary, 91st

Cong., 1st Sess. 255 (1969) .......... 20

42 Opinion of Attorney General

Ho. 37 (Sept. 22, 1969) ................... 20

Legislative H istory:

110 Cong. Rec. 6549 (1964) ........................ 16

110 Cong. Rec. 7213 (1964) ........... 14,16

110 Cong. Rec. 9881-82 (1964) .................... 14-16

110 Cong. Rec. 12723 (1964) ...................... 15

113 Cong. Rec. 3460-63 (1972) .................. 22

Hearings on C iv il Rights 3efore

Subcomm. Ho. 5 o f the

House Comm, on the Judiciary,

88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963) .......... 10

Hearings on Equal Employment

Opportunity 3efore the

General Subcomm. on Labor o f the

House Comm, on Education and

Labor, 88ch Cong. 1st Sess.

(1963) . . . .................................................... 9

PAGE

- xiii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Hearings on Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Before the Subcomm. on

Employment and Manpower o f the

Senate Comm, on Labor and Public

Welfare, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1963) ..................................................... 10

H.R. Rep. No 914, 38th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1 9 6 3 ).......................................... 11,12

H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, 92d Cong.,

1st Sess. (1971) ................................... 22

S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92d Cong., 1st

Sess. (1971) ......................................... 22

Other A uthorities:

Adminstrative O ffice of the United States

Courts, 1976 Annual Report

o f the Director ................................... 34

’PAGE

Administrative O ffice of the United States

Courts, 1977 Annual Report o f

the Director ......................................... 35

Administrative O ffice of the United

States Courts, 1978 Annual Retort

o f the Director ................................... 35

Chayes, The Role o f the Judge in Public

Law L itiga tion , 89 Harv. L. Rev.

1281 (1976) ........................................... 61

Comment, The Philadelphia Plan: A

Study in the Dynamics o f

Executive Power, 39 U. Chi.

L. Rev. 723 (19 7 2) ............................. 20,23,41

- xiv -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Committee on Government Contracts,

Pattern for Progress: Final

Report to President Eisenhower

. (1960) .................... . . ............................ 106

Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission, Legislative History o f

T itles VII and XI o f C iv il Rights

Act o f 1964 ........................................... 11, 17

•PAGE

Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission, Legislative History o f

the Equal Employment Opportunity

Act o f 1972 ........................................... 22

Finkelstein, The Application o f S ta t is t i -

*■ cal Decision Theory to the Jury

Discrimination Cases, 80 Harv.

L. Rev. 338 ( 1966) ............................. 76

Gould, 31ack Workers in White Unions,

(1977) 91

Hall, Black V oca tion a lT ech n ica l and

Industrial Arts Education

(.American Technical Society

1973) ....................................................... 93

H ill, 31ack Labor and the American Legal

Svstem: Race, Work and the Law

(1977) ..................................................... 91

Jones, The Bugaboo o f Employment

Quotas, 1970 Wis. L. Rev.

341 ..................................................................... 107

- xv -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Karson and Radosh, "The American Federa

tion o f Labor and the Negro Worker,-

1894—1949," in The Negro and the

American Labor Movement (ed.

Jacobsen, Anchor 1968) ..................... 96

Marshall, The Negro and Organized

Labor ( 1965) ......................................... 91,94

PAGE

Marshall, "The Negro in Southern Unions,"

in The. Negro and the American Labor

Movement (ed. Jacobsen, Anchor

1968) ........................................... 96,99

Marshall and 3riggs, The Negro and

•Apprenticeship (1967) ....................... 91,98,102-

103

McPherson, The P o lit ica l History o f

Che United States o f America

During the Period o f Recon

struction (reprinted 1969) .............. 93

M osteiler, Rourke and Thomas,

Probability With S ta tis tica l

Applications (1970) ........................... 76

Myrdal, An American Dilemma (Harper

6 Row ed ., 1962) ............................... 91-93,96-

98,100

N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense And Educa

tional Fund, In c ., Brief as

Amicus Curiae, No. 76-811 ............... 52

Northrup, Organized Labor and the

Negro (19 44) ....................................... 91,96-97,100

- xvi -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE

Sovem, Legal Restraints on Racial

Discrimination in Employment

(1966) .................................. 9,106

Spero and Harris, The Black Worker

(Atheneum ed. , 1968) ......................... 91-92

State Advisory Committee, United States

Commission on C iv il Rights,

50 States Report (1 9 6 1 ) ................... 95

tenBroek, Equal Under Law (1951) . . . . 52

United States Commission on C ivil

Rights, Employment (1961) ............... 94

United States Commission on C iv il

Rights, The Challenge Ahead

(1976) ...................................................... 98,103

United States Bureau of the Census,

Census o f Population: 1970 Vol. I ,

Characteristics o f the Popula

tion , Part 20, Louisiana (1973 ).. 67-68,73-74

Weaver, Negro Labor, A National

Problem (1946) ............................. 91,93-94,99,

101

Weinstein, 1 Evidence ............................... 62

Wright and Graham, Federal Practice

and Procedure (1977) ....................... 62

- x v il -

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, L978

No. 78-432

UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA,

AFL-CIQ-CLC,

P etitioner,

v.

BRIAN F. WEBER, et a l.

No. 78-435

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL CORPORATION,

Petitioner,

v. >

BRIAN F. WEBER, e t a l .

No. 78-436

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

and

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION,

. Petitioners,

.. . v.

* 3RIAN F. WE3ER, et a l.

On Writ o f C ertiorari to Che United

States Court of Appeals for Che

Fifth C ircuit

BRIEF OF THE N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., NATIONAL

URBAN LEAGUE AND HOWARD UNIVERSITY

AS AMICI CURIAE

Interest o f Amici

The N .A .A .C .P. Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund, In c ., is a non-profit corporation

- 2 -

established under Che laws o f Che State o f New

York.*- It was founded Co a ssist black persons to

secure their constitu tional and statutory rights

by the p rosecu tion o f la w su its . I ts ch arter

declares that its purposes include rendering legal

services gratuitously to black persons suffering

in ju stice by reason o f ra cia l discrim ination. For

many years attorneys o f the Legal Defense Fund

have represented parties in lit ig a tio n before this

Court and the lower courts involving a variety o f

race discrim ination issues regarding employment.

See, e . g . , Griggs v . Duke Power Co. , 401 U.S.

424 (1971); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405 (1975); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co. ,

424 U.S. 747 ( 1976). The Legal Defense Fund

believes that its 'experience in such lit ig a t io n

and Che research i t has performed w ill a ss is t the

Court in this case. The parties have consented to

the. f i l in g o f this b r ie f and le tters o f consent

have been file d with the Clerk.

The National Urban League, Incorporated, is a

charitable and educational organization organized

as a n o t -fo r -p ro fit corporation under the laws of

the State o f New York. For more than 69 years,

- 3 -

the League, and' its predecessors have addressed

them selves to the problems o f disadvantaged

m inorities in the United States by improving the

working conditions o f blacks and other m inorities,

and by fostering better race relations and increas

ing understanding among a ll persons.

Howard U niversity was e s ta b lish e d as a

private nonsectarian in stitu tion by Act o f Cong

ress on March 2, 1867. Since its inception, the

University has grown from 3Lx departments in 1867

to its present composition o f seventeen schools

and co lleg es . Nearly 40,000 students have rece iv

ed diplomas, degrees or ce r t if ica te s from Howard;

o f that t o t a l , w ell over 14,000 have rece ived

graduate and professional degrees. Throughout

th is-century o f growth, the unique mission o f Che

U n iversity has been supported in the main by

congressional appropriations. Since 1928 Howard

University, while remaining a private in stitu tion ,

has received continuous annual financia l support

from the federal government.— Today, the Uni-

1/ The Committee on Education commenting on the

b i l l to amend section 8 o f an act en titled "An Act

to incorporate the Howard Universicy. . . " stressed:

vers i c y 's land, bu ild in gs and equipment are

valued at: more than 150 m illion d ollars. Thus,

both the executive and leg is la tiv e branches are

sensitive to the need to maintain Howard as an

institution- in service to blacks.

y Cont1d

Apart from the precedent established by

45 years o f congressional action , the commit

tee fee ls that Federal aid to Howard Univer

s i t y is fu l ly ju s t i f ie d , by the n a tion a l

importance o f the Negro problem. For many

years i t has been f e l t that the American

people owed an o b lig a t io n to the Indian,

whom they d isp ossessed o f h is land, and

annual ap p rop ria tion s o f s iz a b le amounts

have been passed by Congress in fu lfillm ent

o f this o b lig a t io n ... .

'Moreover, f in a n c ia l a id has been and

s t i l l is extended by the Federal Government

to the so-ca lled land-grant colleges o f the

various S ta tes . While i t is true that

Negroes may be admitted to these co lleges,

the con d ition s o f adm ission are very much

restr icted , and generally i t may be said that

these colleges are not at a ll available to

the Negro, except fo r agricu l-tu ra l and

industrial education. This is particu larly

so in the professional medical schools, so

that the only class A school in America for

tra in in g co lo re d d o c to rs , d e n t is ts , and

- 5 -

Howard University has a unique in terest in

the resolution o f this case by the Supreme Court.

This case raises questions o f great importance

about the permissible scope o f voluntary affirm a

tive action under T it le VII. Affirmance o f the

lower c o u r t 's p r o s c r ip t io n against voluntary

in t i t a t iv e s w i l l c h i l l voluntary programs in

p a r t ic u la r and a ffirm a tiv e a ction g e n e ra lly .

1/ Cont' d

pharmacists is Howard University, it being

the only place where complete c l in ic a l work

can be secured by Che co lo re d student.

Committee on Education Report Accompanying

H.R. 8466 (1 9 2 6 ) . See a l s o , 14 S ta c .

1021 (1926).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. In enacting T itle VII in 1964 Congress

n e ith er expressly approved nor ex p ress ly d i s

approved race-conscious e ffo rts to correct the

e ffe cts o f discriminatory p ractices. However,

subsequent ju d ic ia l d e c is io n s and execu tive

actions established char T itle VII permitted, and

in some circumstances required, the remedial use

o f race. In amending T itle VII in 1972 Congress

approved th is in te rp re ta t io n o f Che s ta tu te .

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission's

Guidelines on Affirmative Action correctly cod i

fied this interpretation authorizing employers and

unions to adopt ra cia l preferences as remedial

measures where they have a reasonable basis for

that action.

I I . Race-conscious affirm ative action is

ju s t i f i a b le where an employer or union has a

reasonable basis fo r b e lie v in g that i t might

otherw ise be held in v io la t io n o f the law.

The employer or union need not admit nor prove

- 7 -

p r io r , d is cr im in a tio n , and i t may take ra ce -

con sciou s a ction to remedy the disadvantages

a ffectin g m inorities as a result o f discrim ination

by others. A more rig id standard — Like that

adopted by the m a jority o f the F ifth C ircu it

requiring proof or admission o f discriminatory

practices — wouLd largely eliminate voluntary

affirm ative action . Moreover, a lawsuit challeng

ing race-conscious action under that standard does

not present a case or controversy because i t is

noc in the in terest o f either lit ig a n t to prove

the central factual issue, prior discrim ination.

F inally, the Fifth C ircu it 's standard, i f accepted

by this Court, would raise serious questions as to

the con stitu tion a lity of T itle VII.

I I I . Kaiser and the Steelworkers properly

in s t itu te d a ra ce -con sc iou s plan because they

had a reasonable basis to b e lie v e that th e ir

c r a f t s e le c t io n p ra ct ice s had v io la te d , and

w ithout a ffirm a tiv e a ct io n would contin ue to

v io la t e , both T it le VII and E xecutive Order

11,246. Moreover, i t was appropriate and soc ia lly

re sp on sib le fo r Che Company and the Union to

design a program which would remedy some of the

e ffe cts o f decades o f discrim inatory practices by

employers, unions, and governmental bodies which

had denied training opportunities to blacks in the

sk illed cra fts .

The affirm ative action plan was proper since

i t expanded the employment opportunities o f a ll

workers, b lack and w h ite. The ra ce -con sc iou s

component o f the plan conformed, to p rov is ion s

which had been approved by courts and by adminis

tra tive agencies and was designed as an interim

measure which would terminate a fte r remedying the

discriminatory practices. F inally, i t resulted

from co lle c t iv e bargaining in which the interests

o f a ll the workers were represented and i t thus

furthered the p o l i c ie s fa vorin g the voluntary

r e s o lu t io n o f both la b or and d iscr im in a tion

disputes.

- 9 - '

ARGUMENT

I . TITLE VII PERMITS EMPLOYERS AND

UNIONS TO TAKE VOLUNTARY. RACE-

CONSCIOUS AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

A. Legislative History: L964

The CiviL Rights Act o f 1964 was Che f ir s t

comprehensive federal leg is la tion ever Co address

Che pervasive problem of discrim ination against

blacks in modem American society . See M. Sovern,

L egal R e s tr a in ts on R acia l D iscrim in ation in

Employment 8 (1 9 66 ). E xtensive hearings had

focused Che attention o f Congress on Che adverse

socia l and economic consequences o f discrim ination

2/against blacks in employment and ocher f ie ld s ,—

and when the House J u d icia ry Commictee issued

it s report on che b i l l which became Che C iv il

Rights Act o f 1964, i t c le a r ly sta ted chat a

primary o b je c t iv e o f the Act was to encourage

voluntary a ct ion to e lim in ate Che e f fe c t s o f

discrim ination against black c it izen s :

2/ See, e . g . , Hearings on Equal Employment

Opportunity Before the General Subcomm. on Labor

o f the House Comm, on Education and Labor, 88th

• - 10

La v a riou s , r e g io n s o f the co u n try

there is discrim ination against some minority

groups. Most g la r in g , however, is the

discrim ination against Negroes which exists

throughout our Nation. Today, more Chan 100

years a fte r th e ir form al em ancipation ,

Negroes, who make up over JO percent o f our

population, are by virtue o f one or another

type o f d iscr im in a tion not accorded the

rights, p riv ileges, and opportunities which

are considered to be, and must be, the

b irthright of a ll c it izen s .

*■ *■ *-

No b i l l can o r should lay claim to

e lim in atin g a l l o f the causes and con se

quences o f r a c ia l and orher types o f d is

crim in ation against m in o r it ie s . There

is reason to believe, however, that national

lead ersh ip provided by the enactment o f

Federal le g is la t io n d ea lin g with the most

troublesome problems w ill create an atmos

phere conducive to voluntary or loca l reso lu

tion o f other forms o f d is cr im in a tio n .

2/ Gont' d

Cong., 1st Sess. 3, 12-15, 47-46, 53-55, 61-63

(1963 ); Hearings on C ivil Rights 3efore Subcomm.

No. 5 o f the House Comm, on the J u d ic ia r y ,

88th Cong., 1st Sess. 2300-03 (1963); Hearings on

Equal Employment Opportunity Before the Subcomm.

on Employment and Manpower o f the Senate Comm, on

Labor and Public Welfare, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

116-17, 321-29, 426-30, 449-52, 492-94 (1963).

- 11-,

It is , however, possibLe and necessary

f o r th e C ongress to en a ct l e g i s l a t i o n ,

which p ro h ib its and provides the means o f

terminating the most serious types' o f d is

cr im in a tion . . . . H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th

C o n g ., 1st Ses^ . (1 9 6 3 ) , r e p r in t e d in

EEOC, Legislative History o f T itles VII and

XI o f C iv il Rights Act o f 1964 at 2018.

This Court, has rep eated ly recogn ized the

purpose o f the Act: "The ob jective o f Congress in

the enactment o f T it le VII . . . was to achieve

equality o f employment opportunities and remove

barriers that have operated in the past to favor

an id e n t i f ia b le group o f white employees over

oth er em ployees." Griggs v . Duke Power Co. ,

401 U.S. 424, 429-30 (1971); Albemarle Paper Co.

v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 417 (1975). "The language

o f T itle VII makes plain the purpose o f Congress

to assure equality o f employment opportunities

and to eliminate those discrim inatory practices

and devices which have fostered ra c ia lly s tr a t i

f ie d job environments to the disadvantage o f

minority c it iz e n s ." McDonnell Douglas Corn, v .

Green, 411 U.S. 792, 800 (1973). This Court also

has recognized that Congress selected "[c]oop era -

- 12 -

tion and voluntary compliance . . . as the preferred

means fo r ach iev in g th is g o a l ." Alexander v .

Gardner-Denver Co. , 415 U.S. 36, 44 (1974). The

Court, in keeping with the intent o f Congress (see

H.R. Rep. No. 914, pp. 10-11, supra) , has endorsed

the imposition o f ju d ic ia l remedies under- T itle

VII as "the spur or cata lyst which causes employ

ers and unions to self-examine arid to s e lf -e v a lu -

ate their employment practices and to endeavor to

eliminate, so far as possib le , the last' vestiges

o f an unfortunate and ignominious page in this

co u n try 's h is t o r y ." Albemarle Paper Co. v .

Moody, supra, 422 U.S. at 417-18, quoting United

States v. N.L. Industries, Inc. , 479 F.2d 354, 379

(8th Cir. 1973).

The record in th is case, shows chat what

Congress intended and what the Court has endorsed

is p r e c is e ly what happened: K aiser and the

Steelworkers examined their practices and con

cluded that there was a reasonable ba sis to

b e lie v e that they would be found l ia b le fo r

discrim ination against blacks; they had "looked at

the large sums of money that companies were being

fo rced to pay, and we looked at our problem,

which was that we had no blacks in the c ra fts , to

- 13

apeak o f , ” A. 83 (E n g lis h ); and they volun

ta r ily adopted a plan to bring blacks into cra ft

jobs. See Section IIIA and n. 26, in fra . In the

absence o f compelling le g is la tiv e h istory to the

contrary, T itle VII cannot be read to foreclose

the use o f such race-conscious numerical plans to

accomplish the primary purpose o f the Act.

The le g is la t iv e h is to r y o f the o r ig in a l

enactment o f T it le VII in 1964 co n c lu s iv e ly

demonstrates neither approval nor disapproval by

Congress o f race-conscious e ffo rts to correct-th e

e f f e c t s o f che past d iscr im in a tory ex clu s ion

o f blacks from training and job opportunities.

The major argument against congressional approval

o f such e ffo r ts is premised upon the addition to

the b i l l on the Senate flo o r o f §703(j . ) , which

states that nothing in T it le VII shall "require"

preferentia l treatment because or race "on account

- . . , ,,3/o f an imoaiance. . . . —

3/ "Nothing contained in this subchapter shall

be interpreted to require any employer, employment

agency, labor organization, or jo in t labor-manage

ment committee subject to this subchapcer to grant

preferentia l treatment to any individual or to any

group because o f the race, co lor , re lig ion , sex,

or national orig in o f such individual or group on

account o f an imbalance which may e x is t with

- 14

Prior Co Che adoption o f th is amendment,

Che SenaCe f lo o r managers of Che b i l l had -explain

ed chat T itle VII would noc require an employer Co

maincain a rac ia lly balanced work force because,

While Che presence or absence o f ocher

members o f Che same m inoricy group in Che

work fo r ce may be a relevanc fa cco r in

decermining whecher in a given case a d ec i

sion Co hire or Co refuse Co hire was based

on race, co lor , e c c . , i t is only one faccor,

and Che quescion in each case would be

whecher chac in d iv id u a l was d iscrim inated

against. 110 Cong. Rec. 7213 (1964) ( inter

p re t ive memorandum o f Senators Clark and

Case).

Notwithstanding Chis assurance, opponencs of

che b i l l continued to argue "that a quota system

w ill be imposed, wich employers hiring and unions

accepting members, on Che basis of Che percentage

of population represented by each sp e c if ic minor

i ty group." _Id_. ac 9881 (remarks o f Senator

V Cont' d

resp ect Co Che to ta l number or percentage o f

persons o f any race , c o l o r , r e l i g i o n , sex, or

national orig in employed by any employer, referred

or c la ss if ied for employment by any employment

agency or labor organization, admitted co member

ship or c la ss if ied by any labor organization, or

admitted Co, or employed in any apprenticeship or

other training program, in comparison wich Che

to ta l number or percentage o f persons o f such

- 15

ALlott). To put these doubts to rest , Senator

AllotC proposed an. amendment precluding a finding

o f unlawful discrimination "so le ly on the basis of

evidence that an imbalance exists without

supporting evidence of another nature that the

respondent has engaged or is engaging in such

p ra ct ice ." Id . at 9881-82. The sense of this

amendment was incorporated , in the language

o f § 7 0 3 ( j ) , as part o f the Dirksen-M ansfield

compromise which resu lted in the end o f the

Senate debate and the enactment o f the C iv i l

Rights Act o f 1964. As Senator Humphrey explained

in presenting the compromise amendments to the

Senate,

A new subsection 703(j ) is added to deal

with the problem o f r a c ia l balance among

employees. The proponents o f this b ill- have

carefu lly stated on numerous occasions that

T i t le VII does not require an employer

to achieve any sort o f racia l balance in his

work force by giving preferential treatment

to any in d iv id u a l or group. Since doubts

have persisted, subsection ( j ) is added to

state this point expressly. Id . at 12723.

2/ Cont' d.

race, co lor , re lig ion , sex, or national origin

in any community, State, section, or other area,

or in the available work force in any community,

State, section, or other area." 42 U.S.C. §2000e-

2(j ).

- L6

This leg is la tive history does not 'ind icate

that Congress intended to forbid race-conscious

numerical action to correct Che e ffects o f past

d is cr im in a t ion . The concern o f Congress in

enacting §703(j) was not directed to the question

whether race could be taken into account fo r

remedial purposes; rather, i t s in tent was to

ensure that findings of discrimination would noc

be based solely on evidence of s ta t is t ic a l im

balance and thereby to allay the fear chat Title

711 would have Che e f fe ct o f requiring employers

to maintain a sp ec if ic racia l balance o f employ-

4 /

ees The language o f § 7 0 3 ( j ) , l ik e that o f

4/ Senators Clark and Case also stated that "any

deliberate attempt to -maintain a racia l balance,

whatever such a balance may be, would involve a

v iolation o f T itle VII because maintaining such a

balance would require an employer to hire or to

refuse to hire on the basis o f race ." 110 Cong.

Rec. at 7213. See also id . at 6549 (remarks of

Senator Humphrey). Senator A llott believed chat

"a quota system o f h ir in g would be a t e r r ib le

m istake ," but did not in d ica te whether such a

system would be unlawful. _Id_. at 9881-32.

These statements may in d ica te an in ten c ion to

prohibit employers from deliberately maintaining

a particular racial composition of employees as an

end in i t s e l f , but they do not suggest any inten-

- 17

1703(h), does uoc re s tr ic t or qualify otherwise

appropriate remedial action but defines what is

and what is not an i l le g a l discriminatory prac

t ic e . C f. Franks v. 3owman Transportation Go.,

supra, 424 U.S. at 758-62. Indeed, the le g is la

tive history o f Che ]964 Act shows no detailed

consideration o f Che scope and nature o f remedial

a ct ions which might be taken by employers and

unions or ordered by the courts , and i t shows no

consideration whatever o f the perm issibility of

race-conscious remedial measures. See generally,

EEOC, Legislative History o f T itles VII and XI o f

C iv il Rights Act o f 1964. There is no indication

that "in the absence o f any consideration o f Che

question, . . . Congress intended to bar the use of

racia l preferences as a tool for achieving the

o b je c t iv e o f remedying past d is cr im in a t ion or

other compelling ends." 3akke, supra, 57 L.Ed.2d

at 803 n.17 (opinion o f 3rennan, White, Marshall,

Blackmun, J J .) .

4/ Cone ' d

Cion to foreclose "the voluntary use of racial

preferences to assist minorities to surmount the

obstacles imposed by the remnants of past d is

crim ination ." Regents o f the University o f Cali

fornia v. 3akke, 57 L.Ed.2d 7 5 0 , 803 n. 17 ( 1973)

(opinion o f Brennan, White, Marshall, Blackmun,

J J .).

18

B. Judicial and Executive Interpreta

tions: 1964-1972

In Che years following Che enactment o f T id e

^I^> Che courts and federal execucive agencies

recognized chac Congress had not intended Co

outlaw one o f the most e f fe c t iv e means of remedy

ing past d is cr im in a t ion , and accord in g ly they

in terp reted T i t le VII to perm it, and in some

instances to require, the use of race—conscious

numerical remedies. The courts held that §703(j)

could not be construed as a ban on such remedies:

"Any other interpretation would allow complete

n u ll i f ica t ion o f the stated purposes of the Civil

Rights Act o f 1964." United States v. Local 38.

I3EW, 428 F.2d 144, 149-50 (6th C i r . ) , c e r t .

denied, 400 U.S. 943 (1970). T itle VII was held

to authorize remedial orders req u ir in g union

re re r ra ls o f one black worker fo r each white

, 5/ . . .worker,— s p e c i f i c percentages of blacks in

regular apprenticeship classes and special appren—

5/ l*ocal 53, Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407

F•2d 1047, 1055 (5th Cir. 1969).

- 19

t ic e s h ip programs fo r b lacks o n ly ,— and p r e f

e r e n t ia l work r e g is t r a t io n , examination, and

re ferra l procedures for blacks with experience in

the construction industry .—̂ As the Second Cir

c u i t stated in summarizing these d e c is io n s ,

"while quotas merely to attain racia l balance are

forbidden, quotas to correct past discriminatory

practices are not." United States v. Wood Lathers

Local 4 6 , 471 F.2d 408, 413 (2d C i r . ) , c e r t .

denied, 412 U.S. 939 (19 73).-^

Also during the period between the enactment

o f T it le VII in 1964 and its amendment in ]972,

the Department o f Labor determined that numerical

goals and timetables were necessary to implement

6/ United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 315

F.Supp. 1202, 1247-48 (W.D. Wash. 1970), a f f ' d ,

443 F.2d 544, 553 (9th C ir .) , cert, denied, 404

U.S. S84 (1971).

V United States v. Sheet Metal Workers Local 36,

416 F .2d 123, 133 (8th Cir. 1969).

8/ The courts o f appeals in e ight c i r c u i t s

have upheld the authority o f the d is t r ic t courts

to order race-conscious numerical r e l i e f under

T itle VII or other federal fa ir employment laws,

see nn. 94-95 , infra.

- 20 -

the equal employment opportunity and affirmative

action obligations of government contractors under

Executive Order No. 11,246, and that a permissible

method of meeting the goals and timetables in the

construction industry was the hiring o f one minor

i t y craftsman fo r each nonminority craftsman.

See Comment, The Philadelphia Plan: A Study in the

Dynamics o f Executive Power, 39 U. Chi. L. Rev.

723, 739-43 (1972). -Both the Department o f

Labor—̂ and the Department o f Jus tice- -̂2- ̂found

no co n f l ic t between such race—conscious-- measures

and the prov is ion s o f T i t le VTI„ The courts

agreed, holding that §7 0 3 (j) did not impose

any limitation on actions taken pursuant to the

Executive Order program and that,

To read §703(a) in the manner suggested

by the p la in t i f fs , we would have to attribute

to Congress the in ten tion to freeze the

status quo and to foreclose remedial action

2.! Office o f the S o lic ito r , U.S. Department of

Labor, Legal Memorandum, in Hearings on the

Philadelphia Plan and S. 931 3efore che Subcomm.

on Separation o f Powers o f the Senate Comm, on the

J u d ic ia ry , 91st Cong., 1st Sess. 255, ac 274

(1969) .

10/ 42 Op. Act 'y Gen. No. 37 (Sept. 22, 1969).

- 21

under other authority designed to overcome

existing e v ils . We discern no such intention

e i t h e r from the language o f the s ta tu te

or from its leg is la t iv e h istory. Contractors

A s s o c i a t i o n o f E astern P en n sy lv a n ia v .

Secretary o f Labor, 442 F.2d 159 , 173 (3rd

C i r . ) , c e r t . d en ied , 404 U.S. 854 (1971).

See also Southern I l l in o is Builders Association

v. Ogilvie, 471 F.2d 680, 684-36 (7th Cir. 1972),

and cases c i t e d th ere in . Thus, by the time

Congress considered the 1972 amendments to T it le

VII, it- was well established that the 1964 Act

permitted race-conscious remedial action.

C. Legislative History: 1972

In amending T it le VII by the enactment o f the

Equal Employment Opportunity Act o f 1972, Pub. L.

No. 92-261, Congress approved these interpreta

tions o f T i t le VII. Congress was aware that

Employment d iscr im in ation as viewed

today is a . . . complex and pervasive

phenomenon. Experts fa m ilia r with the

subject now generally describe the problem in

terms o f "systems" and " e f f e c t s " rather

than simply in te n t io n a l wrongs, and the

l i t e r a t u r e on the su b jec t i3 r e p le te with

discussions o f , for example, the mechanics

o f s e n io r i t y and l in es o f p rog ress ion ,

perpetuation o f the. present e f fe c t o f pre-act

- 22 -

d iscrim in atory p ra c t ice s through various

in s t i t u t io n a l d ev ices , and te s t in g and

validation requirements. S. Rep. No. 92-415,

92d Cong., 1st Sess. 5 (1971).

The committee reports s p e c i f i c a l l y c i t e d

cases which had approved race-conscious solutions

for these complex and pervasive problems. See,

e .g . , id. at 5, n . l ; H.R. Rep. No. 92- 238 , 92d

Cong., 1st Sess. 8 n.2, 13 n .4 (1971). And, in

a section-by-section analysis presented to the

Senate with the conference re p o r t , the Senate

sponsors o f the leg is la tion stated that,

In any area where the new law does not

address i t s e l f , or in any area where a sp eci

f i c contrary intention is not indicated, it

was assumed that the present case law as

developed by the courts would continue to

govern the app licab ility and construction o f

T itle VII. 118 Cong. Rec. 3460-63 ( 1972),

reprinted in EEOC, Legislative History o f the

. Equal Employment Opportunity Act o f 1972, at

1844.

See 3akke, supra, 57 L.Ed.2d. at 811 n. 28 (opinion

o f Brennan, White, Marshall, 31ackmun, J J . ) .

Moreover, with fu l l awareness o f the ju d ic ia l

decisions interpreting T itle VII to permit the

remedial use of race, Congress not only confirmed

but expanded the remedial authority of the courts

by amending 5706(g) to provide express ly that

appropriate affirmative action under that section

" is not limited to" reinstatement, hiring, and an

award o f back pay, and that a remedial order may

- 23

include "any other eq u ita b le r e l i e f as the

court deems- appropriate." 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g).

See Comment,. The P hiladelph ia P lan , supra,

39 U. Chi. L. Rev. at 759 n.139.

F in a lly , "Congress, in enacting Che 1972

amendments to T it le VII, e x p l ic it ly considered and

re je c te d proposals to a l t e r Executive Order

11,246 and the prevailing ju d ic ia l interpretations

o f T it le VII as permitting, and in some circum

stances requiring, race conscious a ct ion ." Bakke,

supra, 57 L.Ed.2d at 811 n.28 (opinion o f Brennan,

White, Marshall, 31ackmun, J J .) . The detailed

history o f the Dent and Ervin amendments and their

re jection by the House and Senate has been docu

mented elsewhere and need not be repeated here.

See Comment, The Philadelph ia P lan, supra, 39

U. Chi. L. Rev. at 75 1-57. See a ls o , 3o s con

Chanter, N.A.A.C.P., Inc, v. 3eecher, 504 F.2d

1017, 1028 (1st Cir. 1974), c e r t . denied, 421 (J.S.

910 (1975); United States v. Local 212, I3EW, 472

F.2d 634, 636 (6th Cir. 1973). In sum, "[e ]xecu -

t ive , ju d ic ia l , and congressional action subse

quent to the passage o f T itle VII conclusively

established that Che T it le did not bar the reme

d ia l use o f r a c e . " 3akke, supra , at 311 n.23

(opinion o f Brennan, White, Marshall, 31ackmun,

J J .) .

- 24 -

D. EEOC. Guidelines on Affirmative Action-

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

recently cod if ied and reaffirmed this interpreta

tion o f T itle VII in its Guidelines on Affirmative

Action, 4A Fed. Reg. 4421—30 (Jan. 19, 1979), 29

C.F.R. Part 1608. These guidelines were proposed

in part to encourage voluntary compliance by

"authorizing employers to adopt racia l preferences

as a remedial measure where they have a reason

able basis for believing that they might otherwise

be held in v io la t i o n o f T i t l e V I I ." 3akke,

supra, 57 L.Ed.2d at 818 n.38 (opinion o f Brennan,

White, Marshall, Blackmun, J J . ) . Under the

gu ide lines an employer or union, fo l low in g a

reasonable self-analysis of its practices, which

discloses a reasonable basis for concluding that

a ct ion is appropriate , may v o lu n ta r i ly take

reasonable affirmative' action including the use of

"goals and timetables or other appropriate employ

ment too Is which recogn ize the race , sex, or

national orig in o f applicants or employees." 29

C.F.R. §1608.4 (c ) . Such action may be taken where

there is a reasonable basis for believing that i t

is an appropriate means o f , inter a l ia , correcting

the affects of past discrimination, eliminating

- 25

th-e- adverse, impact on m in or it ie s o f present

practices, or terminating disparate treatment. 29

C.F.R. §§1608.3, 1608.4(b). I t is not necessary

for an employer or anion to establish chat i t has

v io la te d T i t le VII in the p as t ; there is no

requirement of an admission or formal finding o f

past discrimination, and affirmative action may be

taken without regard to arguable defenses which

might be asserted in a T itle VII action brought on

behalf o f minorities. 29 C.F.R. 51608.4(b). See

Section I I A, in f r a . The gu ide lines recogn ize

that

Voluntary affirmative action to improve

opportunities for minorities and women must

be encouraged and p rotected in order to

carry out the Congressional intent embodied

in T i t le VII. A ff irm ative a c t ion under

these principles means those- actions appro

p r ia te to overcome the e f f e c t s o f past

or present p r a c t i c e s , p o l i c i e s , or ocher

b a rr ie rs to equal employment opportun ity .

Such voluntary affirmative action cannoc be

measured by the standard o f whether i t would

have been required had there been l it ig a t ion ,

for this standard would undermine Che le g is

lative purpose o f f i r s t encouraging voluntary

action without l i t ig a t io n . Racher, persons

subject to T itle VII must be allowed f l e x i

b i l i t y in modifying employment systems and

p ra c t ice s to comport with the purposes

o f T i t le VII. Correspondingly, T i t le VII

must be construed to permit such voluntary

26

action, and those taking such action should

be afforded — protection against T itle VII

l ia b i l i t y . . . . 29 C.F.R. §1608. l(c.).

These guidelines "constitute 'the administra

tive interpretation of the Act by the enforcing

agency,' and consequently they are 'en tit led to

great d e f e r e n c e . Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

supra, 422 U.S. at 431; Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

supra, 401 U.S. at 433-34. The degree o f defer

ence to be accorded to such an in te rp re ta t io n

depends upon "the thoroughness evident in i t s

con s id era t ion , the v a l id i t y o f i t s reasoning,

i t s con s isten cy with e a r l i e r and la te r pro

nouncements, and a l l those fa c to rs which give

it power to persuade, i f lacking power to con

t r o l . " General E le c t r ic Co. v . G i lb e r t , 429

U.S. 125, 142 (1976), quoting Skidmore v. Swift

& Go. , 323 U.S. 134, 140 (1944.).

When judged by these standards, the Guide

lines on Affirmative Action are entitled to great

weight. First, the EEOC's careful and thorough

consideration is evident: the proposed guidelines

were in t ita l ly issued on December 28, 1977, 42

Fed. Reg. 64., 82 6; comments were rece iv ed from

almost 500 ind iv iduals and organ ization s ; the

- 27 -

Commission considered this Court's opinions in the

Bakke case before taking any final action ; and

substantial changes were made before the Commis

sion voted to approve the guidelines in final form

on December 11, 1978. See Supplementary Informa

tion: An Overview o f the Guidelines on Affirmative

A c t io n , 44 Fed. Reg. at 4422-23. The EEOC's

extensive consideration o f the comments, the legal

a u t h o r i t ie s , and the p rec ise wording o f the

g u id e lin es is r e f le c t e d in some d e t a i l in the

overview issued with the fina l guidelines. Id_. at

4422-25. Second, Che va lid ity o f the reasoning

sec forth in the guidelines is apparent from the

leg is la t ive history o f the 1964 enactment and the

1972 amendment o f T i t le VII, as w ell as from

ju d ic ia l and other executive agency interpreta

tions o f the s ta tu te . See pp. 18-21, supra.

Finally, the guidelines are fu lly consistent with

prior interpretations of T itle '/II by the EEOC

expressly approving "[n]umerical goals aimed at

increasing female and minority employment" as "the

cornerstone o f . . .. a[n a f f irm a tiv e a c t ion ]

plan." EEOC Decision 74-106, 10 in? Cases 269.

- 28

274 (April 2, 1974); EEOC Decision 75-268, 10 -FEP

Cases 1502, 1503 (May 30, 1975). See also, Equal

Employment Opportunicy Coordinating C ouncil,

P o licy Statement on A ffirm ative Action Programs

for State and Local Government Agencies, 41 Fed.

Rag. 38,814 (Sept. 13, 1976), reaffirm ed and

extended to a l l persons subject to federal equal

employment opportunity laws and orders in the

Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Proce

d ures , 43 Fed. Reg. 38,290, 38,300 (Aug. 25,

1978), 29 C.F.R. §1607.13B.

II. A STANDARD PERMITTING EMPLOYERS AND

UNIONS TO TAKE RACE-CONSCIOUS

AFFIRMATIVE ACTION WHEN THEY HAVE A

REASONABLE BASIS TO DO SO IS CON

SISTENT WITH TITLE VII AND THE

CONSTITUTION

A. An Employer or Union May Take Race-Con

scious Affirmative Action Where It Acts

upon a Reasonable B elief that Such

Action Is Appropriate

An employer when con s id er in g whether to

in s t i t u t e a ra ce -con sc iou s a f f irm a tiv e a c t ion

plan, or a court when reviewing a challenge to

such a plan, need only decarmine that there is a

reasonable basis for the plan in order to conclude

thac the plan is law fu l. The employer is not

required to admit chat it had engaged in unlawful

- 29

p r io r d iscr im in a tory p r a c t ic e s or to submit

evidence su ff ic ien t for a court to find that the

employer had violated the fa ir employment laws in

order to j u s t i f y the in s t i t u t io n o f the plan.

EEOC Guidelines on Affirmative Action, 29 C.F.R.

5 1 6 0 8 .1 (c ) . See Section I D, supra . A r ig id

standard req u ir in g con c lu s iv e p roo f o f p r io r

discrimination would largely eliminate voluntary

affirmative- action, see pp. 32-34, in fra . The

circumstances which constitute a reasonable basis

for instituting an affirmative action plan vary

according to the particular employment situation.

However, an employer or union may develop a race

conscious affirmative action plan when there is

reason to believe that such action is appropriate,

in te r a l i a , (1 ) to provide a remedy for p r io r

discriminatory practices o f the employer or union,

(2) to insure the lega lity o f current practices,

(3) to provide a remedy for discriminatory prac

tices related to the business of the employer or

union, or (4) to comply with Executive Order No.

11,246 or other legal requirements for affirmative

action. — Moreover, the '-action undertaken must

be reasonably related to the identified problems

which ju s t i fy the institution o f the plan, see

Section IIX 3, in fra .

In enacting T i t le VII Congress s e le c te d

[c]ooperation and voluntary compliance . . . as

the preferred means for achieving” the elimination

o f discrimination in employment. Alexander v.

Gardner-Oenver Co. , supra, 415 U.S. at 44. The

standard for determining whether an affirmative

action plan is lawful under T itle VII must simi

larly encourage voluntary compliance and voluntary

action. The standard adopted by a majority o f the

court below, which would require an emnloyer to

admit that i t was guilty o f unlawful discrimina—

tory practices or' to submit conclusive proof of

such practices before i t could lawfully institute

an a ff irm a tiv e a ct ion plan, would fru s tr a te

the purposes of T itle VII.

W Of course , in ce r ta in circum stances an

employer or union may be required to institute an

affirmative action program. The ju stif ica tion s

for race-conscious affirmative action which are

listed are not exclusive but rather those chat

are relevant to the a f f irm a tiv e a ct ion plan

designed by Kaiser and the Steelworkers.

- 31

[T]he standard produces . . . an end to

voluntary compliance with T it le VII. The em

p lo y e r and the union are made to walk a

high tightrope without a net beneath them.

On one s ide l i e s the p o s s i b i l i t y o f l i a

b i l i t y to m in or it ie s in p r iva te a c t io n s ,

fed era l pattern and p r a c t ic e s u i t s , and

sanctions under Executive Order 11246.

On the other side is the threat o f private

suits by white employees and, potentially ,

fed era l a ct ion . . . [T]he defendants could

well have realized that a v ictory at the cost

of admitting past discrimination would be a

Pyrrhic v ictory at best. G. Pet. 32a—34al2/

(Wisdom, J . , d issenting).13/

12/ This form o f c ita t ion refers to the petition

fo r a writ o f c e r t i o r a r i f i l e d by the United

States and the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission.

13/ Iron ica lly , i f the applicable standard were

Co require conclusive proof or an admission of

prior discriminat ion r then the back pay remedy

which the Court indicated should provide a "spur

or catalyst" for voluntary compliance, Albemarla

Paper Co. v. hoodv, supra, 422 U.S. at 417-18,

would instead provide a b a rr ie r to voluntary

compliance. The admission of prior discrimination

or the submission o f conclusive proof of discrim i

nation would serve as an open invitation tor a

su it seeking back pay by b lack workers. The

fa i lu r e o f the company to admit or to prove

conclusively its prior discrimination would serve

as an equally open invitation tor a suit seeking

back pay in addition to injunctive r e l i e f by white

workers. I f whenever undertaking a ff irm a tiv e

action employers were confronted with monetary

l ia b i l i t y to one group of workers or the other,

- 32 -

The '"h ig h t ig h tr o p e " that employers are-

required to walk by the Fifth C ircu it 's standard

is i l lu s t r a t e d by K a iser 's experience with

T itle VII suits at its three plants in Louisiana

— at Baton Rouge, Chalmette and Grammercy.

31ack workers at both the Chalmette and the 3aton

Rouge plants brought lawsuits alleging T it le VII

v io la t io n s . In the Chalmette s u i t , the F ifth

Circuit reversed the d is t r ic t court 's dismissal of

the complaint, because i t found on facts remarkably

similar to those at the Grammercy plant that a

prima fa c ie v io la t io n o f T i t le .VII had been

established. Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical

Coro. , 575 F.2d 1374, 1389-90 (1978). In the

13/ Cant'd

employers would refrain from ever taking affirma

tive action.

"Indeed, the requirement o f a ju d i c ia l

determination of a constitutional or statutory

v io lation as a predicate for race-conscious reme

d ia l a ct ions would be s e l f - d e f e a t in g . Such

a requirement would severely undermine e fforts to

achieve voluntary compliance with the requirements

of law." 3akke, supra, 57 L.Ed.Zd at 818 (Bren

nan, White, Marshall, 31ackmun, J J .) ; see McDaniel

v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971).

- 33

3aton. Rouge s u i t , the p a r t ie s , a f t e r Lengthy

. . . . 14/l i t ig a t io n and discovery procedures,— en tered

into a settlement which provided that Kaiser pay

$255,000 in monetary r e l i e f to the p la in t i f f class

and an a d d it io n a l amount in a t to rn e y s ' fe e s .

3urrell v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corn. , Civil

Action No.67-86 (M.D. La.) (consent decree f i le d

Feb. 24, 1975). K a iser 's experience with the

T it le VII suits brought by black workers in its

p lants in Louisiana and i t s review o f su its

brought against other companies acted — as in

tended by this Court in Albemarle Paper — as a

"spur or c a t a ly s t " fo r change.— ̂In the th ird

plant, at Grammercy, where Kaiser adopted an a f

firmative action plan designed to remedy possible

p r io r v io la t io n s and to f o r e s t a l l - a lawsuit

brought on behalf o f black workers, see Section

IIIA, in fra , i t was subjected to this lawsuit by

14/ See, e .g . , Burrell v. Kaiser Aluminum and

Chemical Corp. , 408 F.2d 339 (5th Cir. 1969) (per

curiam), rev 'g 287 F.Supp. 289 (E.D. La. 1968).

15/ The superintendent for industrial relations

at the Grammercy plant noted that "the OFCC, the

EEOC, the NAAC?, the Legal Defense Fund [had a l l ]

been into the [3aton Rouge] plant, and as I was

saying, whatever their remedy is believe me, i t ' s

one heck of a lo t worse than something we can work

out ourselves." A. 83-34, see p .58 n.26, in fra ■

- 34 -

Brian Weber alleging reverse discrimination. The

Fifth C ircu it 's r ig id standard,' requiring conclu

sive proof or an admission o f prior discriminatory

practices, would not only result in less voluntary

compliance but would also result — as indicated

by K a iser 's experience in Louisiana in the

f i l l i n g o f the court dockets with T i t l e VII

16/su its .— See G. Pet. 32a (Wisdom, J . , d issenting).

Race-conscious affirmative action is ju s t i

fiable i f an employer or a union has a reasonable

basis for believing that i t might otherwise be

_16_/ There was a "s ta g g er in g " increase in the

number o f T itle VII cases fried between 1970 and

19 76 : from 344 employment cases f i led in. f is ca l

year 1970 to 5,321 in f is ca l year 1976. Adminis

trative. O f f ic e o f the United States Courts,

1976 Annual Report o f the D irector, at 107-08.

This increase is understandable in light of the

facts that the coverage o f T it le VII was broadly

expanded by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972, see e .g . , Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S.

840, 841 (1976), and that the interpretation of

T itle VII on numerous issues was f i r s t c la r i f ie d

during this p er iod . See e .g , Griggs v . Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971); McDonnell Douglas

Cor?, v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973); Albemarle

Paner Co. v. Moodv, 422 U.S. 405 (1975).

- 35

held in v io la tion o f T it le VII. An affirmative

action- plan may be used to remedy Che e f fe c ts o f

p o s s ib le p r io r d iscr im in atory p ra c t ic e s or to

prevent p o ss ib le continuing d iscr im in atory

16/ con t1d

This enormous growth rate in T i t l e VII

filings^ slowed after f is c a l year 1976. While there

was an increase of 1,390 fi l in gs or o f 35.4% from

FY 1975 to FY 1976 (3,931 f i l i n g s as compared

to 5,321 f i l in g s ) , in FY 1977 there was an in

crease o f 610 f i l in gs or o f 11% to 5,931. Admin

istra tive Office o f the United States Courts, 1977

Annual Report o f the D irector, at 112. In FY 1978

there was a deerease o f 427 f i l i n g s or o f 7%

(from 5,931 to 5,504 f i l in g s ) . Administrative

Office o f the United States Courts, 1978 Annual

Report o f the D irector, at 88;

•While it i s - d i f f i c u l t to draw hard conclu

sions from the dramatic change in the rata

o f T i t le VII case f i l i n g s from a "s ta g g er in g "

increase to a decrease, i t may be inferred that

the c la r i f ica t ion s in the law and the emphasis on

voluntary affirmative action were beginning to

have an e f fe c t . I f voluntary affirmative action

is severely restricted — as it would be i f the

Fifth Circuit is affirmed — then Che remedy for

employment discrimination would l i e primarily in

the courts and not in voluntary resolution, and a

return Co a substantial increasing rate o f T it le

VII cases could be expected.

- 36

practices .— ̂ This Court has held that a s ta t is

t ica l disparity resulting from a fa c ia l ly neutral

practice is su ff ic ien t to establish a prima facie

disparate impact v io la tion o f T it le VII, Dothard

v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321, 329 (1977); and that

gross s ta t is t ica l d isparities alone may be s u f f i

c ie n t to c o n s t i tu te a prima fa c ie showing o f

in te n t io n a l d is cr im in a t ion , Hazelwood School

D istrict v. 'United States, 433 U.S. 299, 307-08

•(1977); International Brotherhood o f Teamsters v .

United States, 431 U.S. 324, 339 (1977). Accord-

17/ " I f the s e l f analysis shows that one or more

employment practices: (1) have or tend to have an

adverse e f f e c t on employment op p ortu n it ies o f

members of previously excluded groups, or groups

whose employment or promotional opportunities have

been a r t i f i c ia l ly limited, (2.) leave uncorrected

the e ffects of prior discrimination, or (3) result

in d isparate treatment, the person making the

self-analysis has a reasonable basis for conclud

ing that action is appropriate. It is not neces

sary that the self-analysis establish a v io la tion

o f T i t le VII. This reasonable basis ex is ts

without any admission or formal finding that the

person has violated Title VII, and without regard

to whether there e x is t arguable defenses to a

T itle VII action ." EEOC Guidelines on Affirmative

Action, 29 C.F.R. §1608.4(b); see also 51608.3(b).

- 37 -

ingly, employers and anions may rely on s t a t i s t i

cal analysis in determining whether there is a

18/reasonable basis for taking affirmative action .—

Where, as in this case, Che s ta t is t ic a l analysis

indicates a prima facie showing that the employ

e r 's prior practices were discriminatory and that,

i f Che employer did not take ra ce -con sc iou s

affirmative action, its continuing practices would

be d is cr im in a tory , see pp. 82-85, i n f r a , the

employer has a reasonable basis for caking such

action.

But the a n a ly s is need not d em on stra te

that there is a prima fa c ie case in order for

race-conscious action to be ju s t i f ia b le . Requir

ing an employer to demonstrate a prima fa c ie

case would frustrate voluntary compliance and the

e f fe c t iv e implementation of private remedies for

discriminatory practices for Che same reasons,-

although not quite as severely, as requiring Che

employer Co admit that i t had engaged in d i s -

18/ "The e ffects o f prior discriminatory prac

tices can be in i t ia l ly identified by a comparison

between Che em ployer 's w orkforce , or a part

thereof, and an appropriate segment o f Che labor

fo r ce ." EEOC Guidelines on Affirmative Action,

29 G.F.R. 51608.3(b). See a lso 551608.3 (a ),

1608.4(a).

• • . 19/crim inatory p r a c t i c e s .— In order to j u s t i f y

race-conscious affirmative action an employer need

only show that i t had a reasonable basis fo r

believing that, in the absence o f such action,

i t might be held in v io la t io n o f T i t l e VTI.

Furth erm ore , an em ployer o r union may

take- race-conscious action to remedy the disad

vantages a f f e c t in g m in or it ie s as a r e s u lt o f

the discriminatory practices o f other companies or

unions or as a result o f governmental or societa l

. . . 20/d iscr im in ation .-1— Such action, is p a r t ic u la r ly

19/ Neither Kaiser nor the Steelworkers argued in

the d is tr ic t court that there was a prima facie

case o f discrimination even though it is apparent

that such an argument was readily available, see

pp. 56 - 58,. in fra . In fact, the parties did not

introduce important but available evidence which

would have confirmed the prima facia showing, see

P* 60 n. 27 .in fra . The reason for the omission

is obvious: oy proving or almost proving prior

discrimination, the parties would invite a suit

brought on behalf of black workers which would

involve the p arties in the complex l i t i g a t i o n

which they had sought to avoid by agreeing to the

affirmative action plan.

20/ "Although T itle VII c learly does not require

employers to take a c t ion to remedy the d isa d

vantages imposed upon racia l minorities by hands

- 39 -

necessary where, as is Che case wich s k i l l e d

craftsm en, see pp. 89 -104 , i n f r a , there i s a

limited pool o f available minorities because o f a

history of discrimination by employers, by unions,

by educational institutions and even by law. See

EEOC Guidelines on Affirmative Action, 29 C.F.R.

§1608 .3 ( c ) . I f the p ervas ive , complex, and

systemic discriminatory practices in this country

— and their soc ia lly dangerous e f fe c ts , such as

the d isp rop or t ion a te unemployment rate among

minorities — are ever to be undone, employers

must be encouraged to undertake soc ia lly respons

ib le affirmative action. See 3akke, supra, 57

L.Ed.2d at 844-45 (Blackmun, j . ) .

It is almost inevitably the case that employ

ers l ik e Kaiser become part and parce l o f the

general practices, of discrimination. When Kaiser

s e le c te d from a pool o f s k i l l e d craftsmen to

which minorities had limited access because of

discriminatory business, union, and vocational

20/ Cont 'd

other than their own, such an objective is per

fect ly consistent wich the remedial goals of the

statu te ." 3akke, supra, 57 L.Ed.2d at 804 n . 17

(op in ion o f 3rennan, Marshall, White, B la ck

mun , JJ. ) .

. — 40

training practices, i t re lied on and, in e f fe c t ,

supported the discriminatory practices o f others.

Reliance on the discriminatory po lic ies o f others

which has an adverse impact on minorities, whether

done- intentionally or simply without su ff ic ien t

business ju s t i f ica t io n , may constitute a v io lation

2 1 /of T i t le VTI.— At the very 1-east, a company